Nick Goepper's Path Back: The Athlete Who Almost Quit

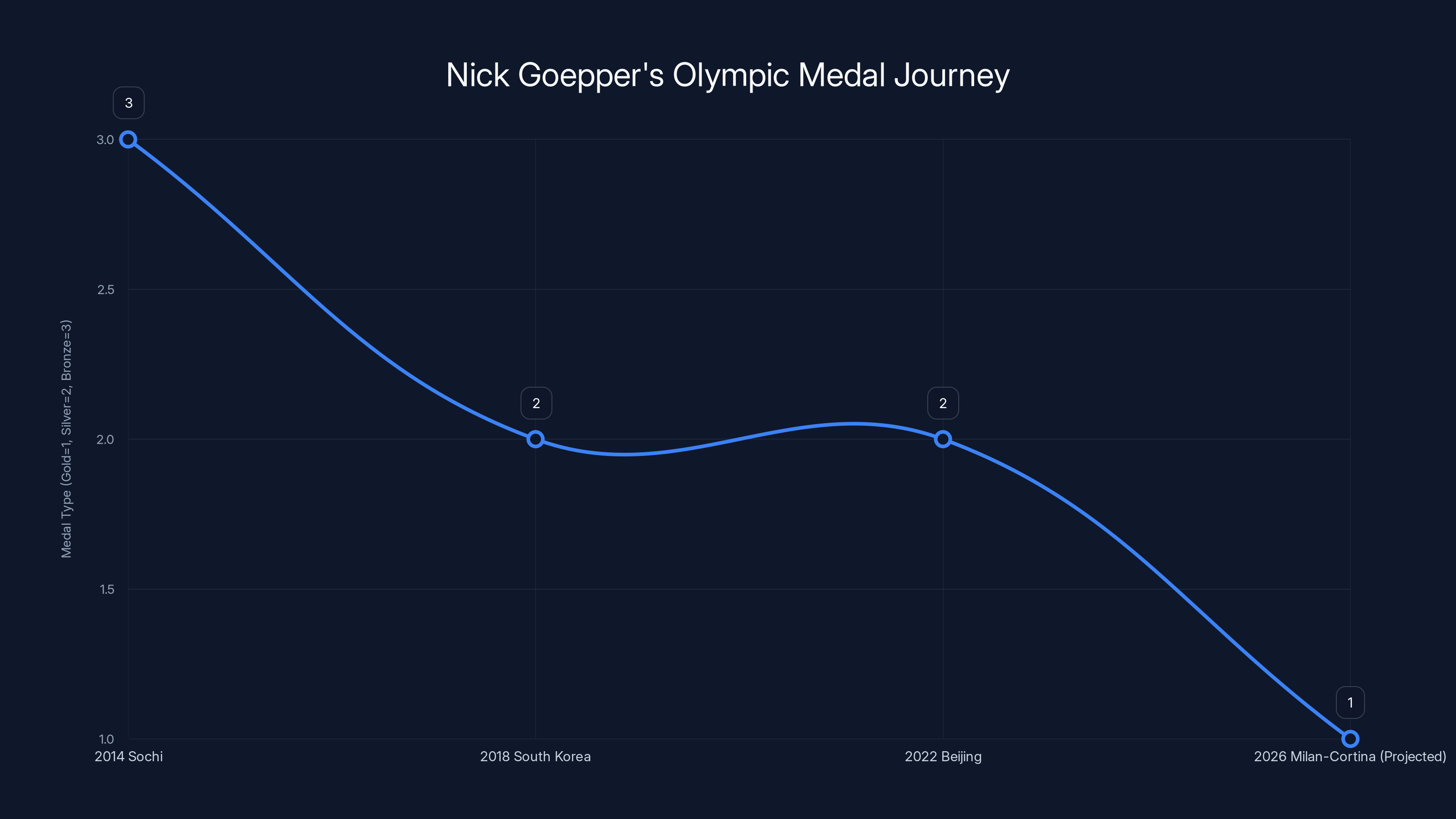

Nick Goepper had won everything. Bronze in Sochi at 19. Silver in South Korea. Silver in Beijing. Three Olympic medals before most people finish college. And by 2022, he was done.

Not physically done. Mentally done. The kind of burnout that doesn't show up in training times or competition results but eats you from the inside. He was anxious, exhausted, partying too much, and unable to switch off the constant pressure he'd put on himself. The button that had always been "on" for years kept him competing, kept him winning, but it was destroying everything else.

He stepped back. Got therapy. Adjusted his routines. And then something unexpected happened: he actually got better.

Now 31 years old and preparing for the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan-Cortina, Goepper isn't the same athlete who burned out. He's shifted from slopestyle to halfpipe, won gold at the 2025 X Games, and taken silver at the 2025 FIS Freestyle Ski World Championships. But more importantly, he's figured out something most high-level athletes never do: how to perform at your absolute peak while actually enjoying the process.

"When you get into your early thirties, you get better at turning it on and off," he told us during a sit-down about what he's packing for Milano Cortina. "When I was 18 to 25, that button was always on. As you get older, you learn there are moments to go balls to the wall, psychopath mode, and then moments to relax, sleep, and not worry about falling behind. You get confident knowing exactly when to be a killer."

This isn't just motivational talk. It's a fundamental shift in how elite athletes approach their sport after learning hard lessons about sustainability and mental health. For Goepper specifically, it means being extremely intentional about everything: his recovery tools, his mindset practices, his gear choices, and even something as simple as clean underwear before a run.

What follows is a deep dive into what a four-time Olympian actually brings to the biggest stage in skiing. It's not all cutting-edge tech or expensive sponsorship deals. Some of it is embarrassingly simple. But when you're dropping into an Olympic halfpipe at 40+ mph, performing flips and twists that could end your career if something goes wrong, the small details matter more than you'd think.

TL; DR

- The Basics Matter Most: Even Olympic athletes sweat the small stuff like fresh underwear and proper lens care because fundamentals win competitions

- Recovery Infrastructure: Foam rollers, recovery protocols, and travel routines are non-negotiable for maintaining peak performance

- Mindset Over Machinery: At 31, Goepper's biggest advantage is learning to control when he's "on" versus when he rests, not having the most expensive gear

- Mental Health First: His comeback only happened after prioritizing therapy and mental health support, not just physical training

- Diverse Preparation: Success comes from an eclectic mix of music, reading, physical tools, and deliberate recovery practices

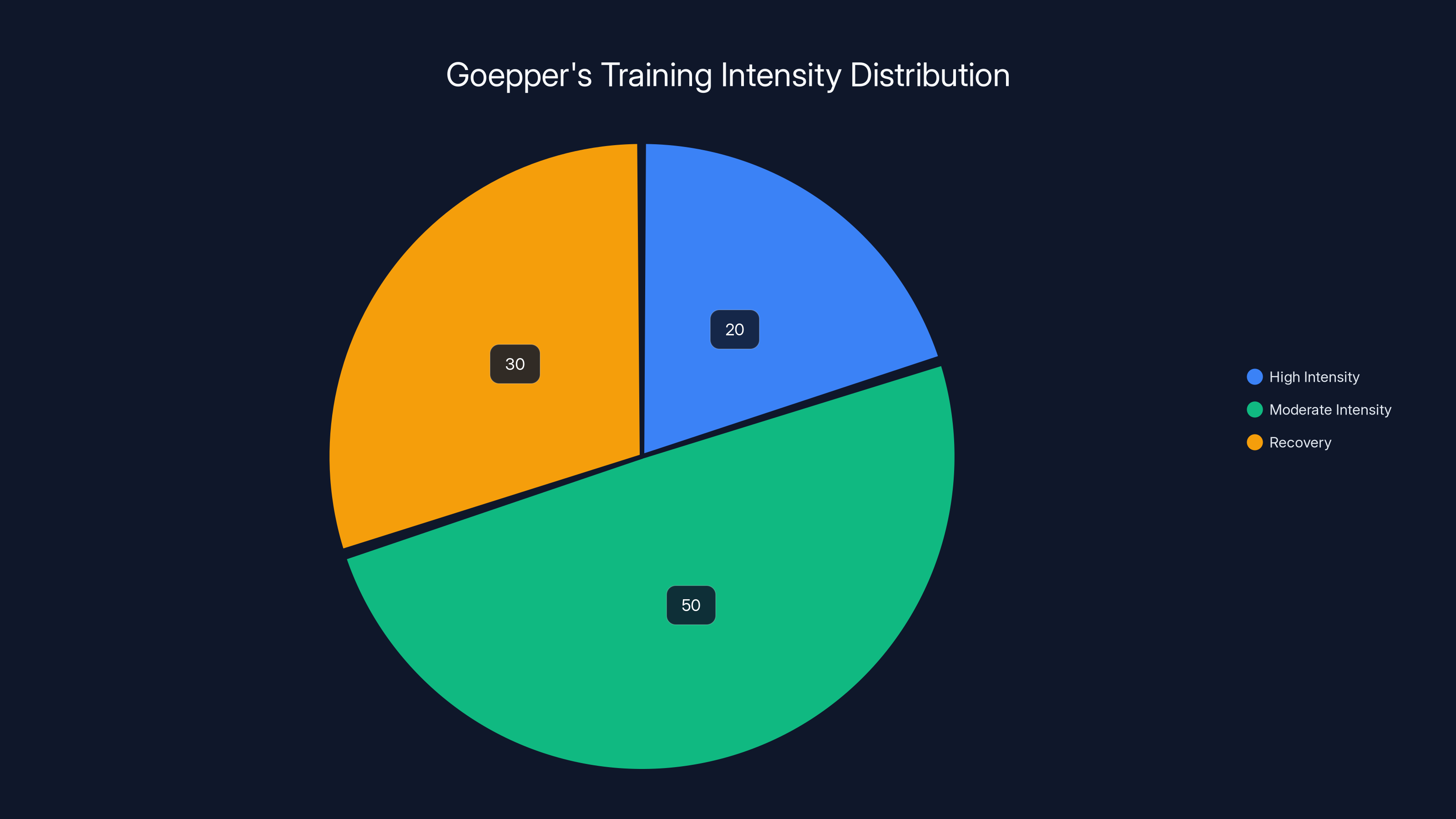

Goepper's training philosophy emphasizes a balance: 20% high intensity, 50% moderate intensity, and 30% recovery. Estimated data highlights the importance of varied intensity for long-term performance.

Foundation Gear: The Unsexy Essentials That Win Races

Talk to most elite athletes, and they'll tell you that the fundamentals are where 80% of performance lives. Goepper is no exception. Before he even gets to the specialized skiing equipment, he's particular about basics that most people wouldn't even think about.

His choice of base layers, underwear, and foundational gear isn't about luxury or brand recognition. It's about comfort, function, and the psychological benefit of starting a run feeling totally prepared. When you're about to throw yourself down a half-pipe at Olympic speeds, you want zero distractions.

"I gotta have super clean underwear," he says without irony. "Kind of new and crispy." He's actually serious about this. Fresh underwear goes on five minutes before he walks out the door for a run. He won't ski in the same pair he slept in. It sounds trivial until you realize that every Olympic athlete has their own version of this ritual—the tiny controllable element that anchors them before chaos.

Nike's Dri-FIT Boxer Briefs (which he packs in three-packs) aren't exotic. They're available at any sporting goods store. But they're engineered for exactly what Goepper needs: moisture management in extreme cold, no chafing under tight ski pants, and the durability to survive months of competition travel without degrading.

The psychological component here is real. Athletes call it "starting clean." It's the same reason Olympic swimmers show up in fresh competition suits, why baseball players have specific socks, why dancers break in new pointe shoes for specific performances. When everything else is uncertain and dangerous, controlling one small element creates psychological stability.

For Goepper, these foundation pieces do more than manage sweat and temperature. They're part of his pre-competition ritual that signals to his nervous system: you're prepared, you're ready, this is going to go well.

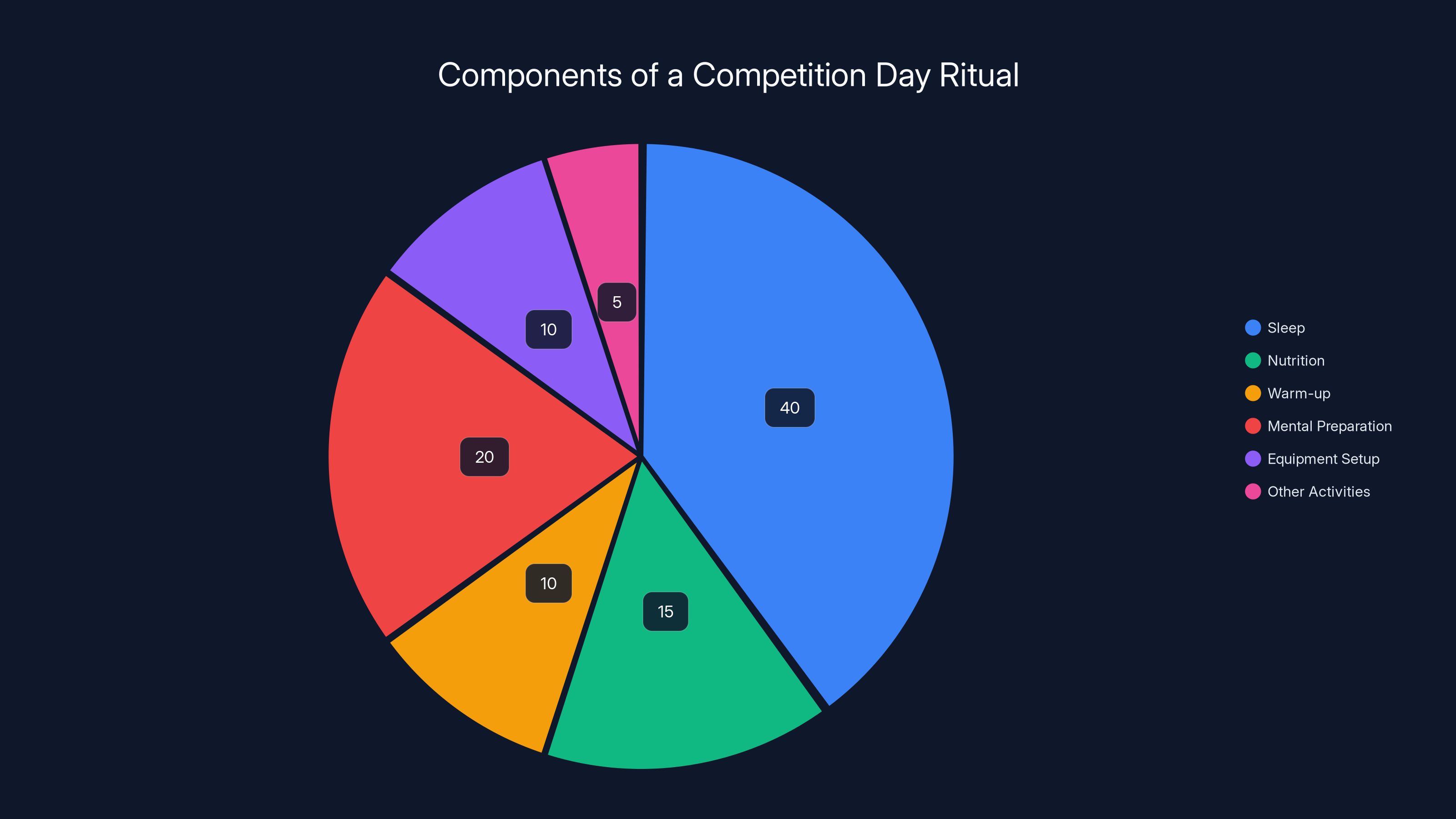

Estimated data showing how an athlete like Goepper might allocate time on competition day. Sleep and mental preparation are key components.

Vision Performance: Why Lens Technology Matters More Than You Think

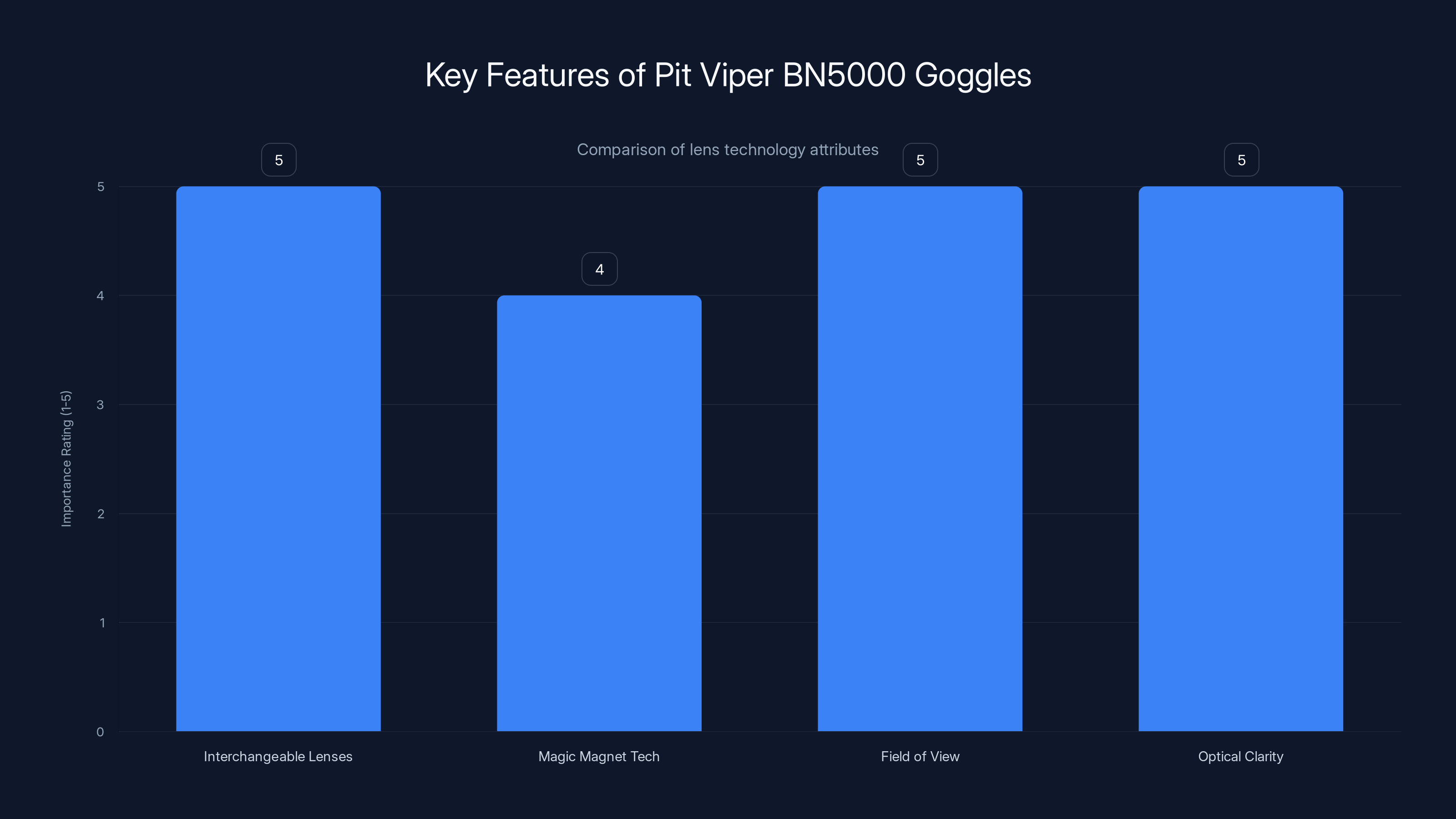

If underwear is about psychological anchoring, goggles are about literal sight. And Goepper takes his vision setup seriously enough that it's one of the few pieces of equipment he describes himself as being obsessive about.

"I am a lens freak," he tells us, and he means it in a way that suggests he's spent hundreds of hours thinking about optical clarity, anti-fog properties, and lens tint at different times of day.

The Pit Viper BN5000 goggles are his choice, specifically because of their interchangeable lens system and the Magic Magnet technology that lets him swap lenses even with full gloves on. This isn't just convenience. During a competition day, Goepper might encounter wildly different lighting conditions: bright midday sun, afternoon clouds, night sessions under artificial lights. A lens that works for 10 a.m. will handicap you by 3 p.m.

He carries two lenses: a blackout lens for peak daylight hours when glare from snow is at its worst, and a clear lens for nighttime sessions. The optical engineering behind this is more complex than most people realize. A blackout lens needs to reduce brightness without distorting depth perception. You need to know exactly where the edge of a jump is, where your landing zone is, and what the terrain transitions look like. A lens that's too dark or has chromatic aberration will throw off your spatial awareness by inches, which at halfpipe speeds translates to crashes.

The BN5000 also features an ultrawide field of view—about 185 degrees compared to standard goggles at 150 degrees. At full throttle in a halfpipe, peripheral vision matters. You need to see the walls coming up before you're directly looking at them. You need to know where the lip of the pipe is without having to move your head. Half a second of additional spatial awareness is the difference between landing clean and eating snow.

"They make you go faster," Goepper jokes about the bright flames on the strap. But then he adds something serious: "They keep your head nice and warm on cold days." That's the real point. Goggles are also insulation. Wind chill at speed is brutal. Goggles that seal properly and don't let freezing air pour across your face reduce the cognitive load of dealing with cold, which means you can focus on the technical aspects of your run.

What's interesting about Goepper's lens system is that it requires planning and execution. He has to remember to pack both lenses, check weather forecasts to decide which one to bring to the mountain, and actually swap them during training sessions. It's not passive. It's an active choice to optimize every variable.

Audio Setup: Music as Recovery Tool and Mental State Management

Goepper travels with a Sony SRS-XB100 Compact Bluetooth Speaker. At first glance, this seems unrelated to athletic performance. It's just a speaker. But talk to him about why it matters, and you realize it's actually part of his mental health infrastructure.

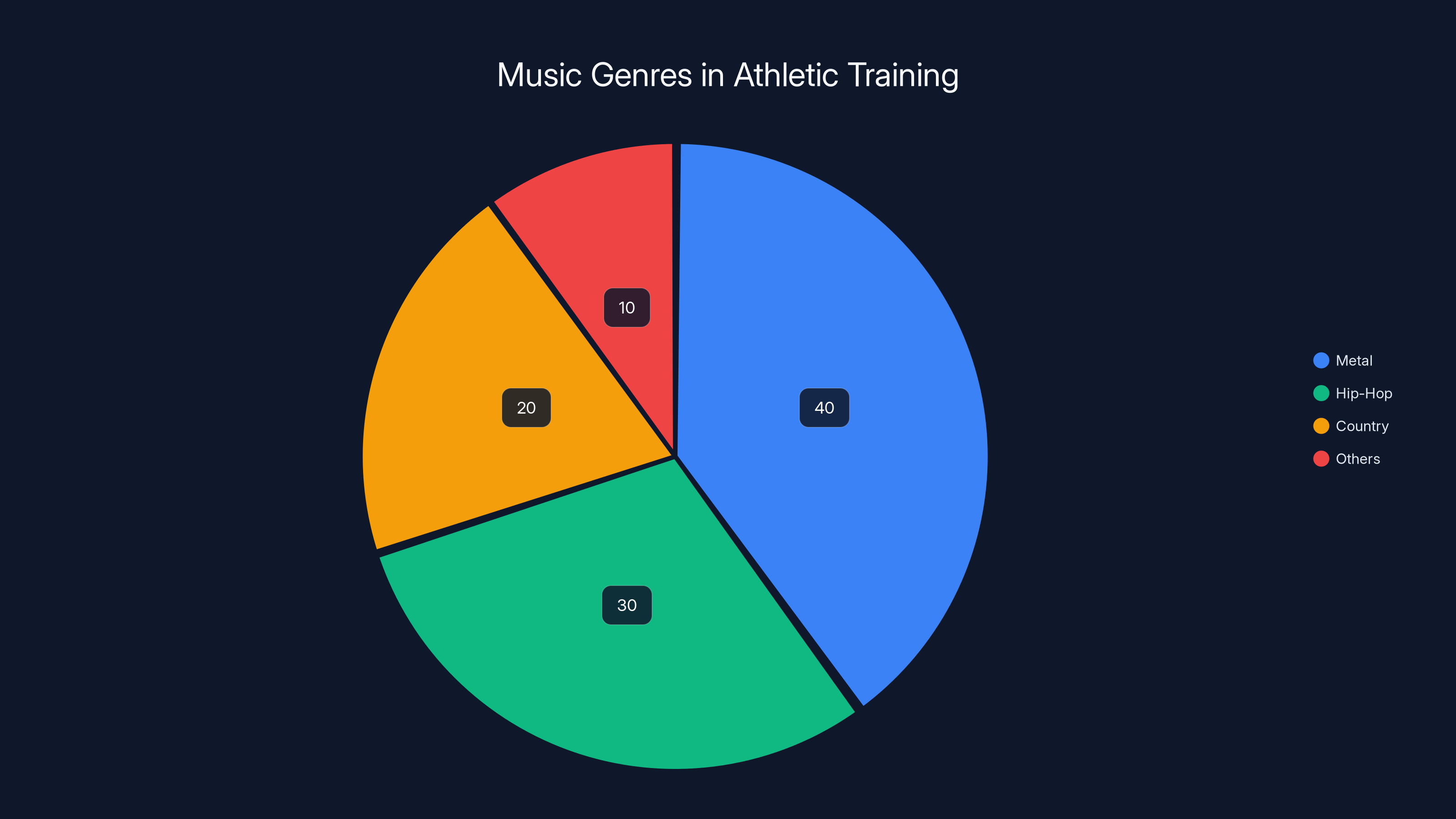

"I've got music going 24/7," he says, holding up the compact device. On any given training day, his playlist might include Juicy J's "Moonwalking," Sum 41's "Underclass Hero," or Kreator's "Satanic Anarchy." The range is intentional: metal for high-intensity training sessions when he needs aggression and focus, hip-hop for technical skill work when he needs flow state, and yeah, occasionally country, because music taste in elite sports isn't a rigid thing.

The speaker itself is engineered for the exact environment Goepper operates in. It's rated IP67, meaning it's dustproof and waterproof to submersion in up to 1 meter of water for 30 minutes. When you're bouncing between training slopes, hotels, airports, and snow, a speaker that can survive that environment is essential.

But the real value is psychological. Music is one of the few things Goepper can control during his day. Training conditions are fixed. Altitude is fixed. Weather is mostly fixed. But his music? That's his choice. He can choose aggression or calm, energy or focus, distraction or flow state. During recovery days, music helps him mentally shift away from competition mode. During intense training, it helps him access the specific psychological state needed to push through hard sessions.

The 16-hour battery life means it survives long travel days. He can clip it to his backpack and have sound throughout morning training, afternoon recovery sessions, and evening recovery activities. It's not just entertainment. It's environmental engineering for mental state.

Most athletes don't think about this intentionally, but the elite ones do. The research on music and athletic performance is actually pretty solid: tempo and rhythm can influence arousal level, focus, and even pain tolerance. A song at 120 BPM has neurological effects that differ from a song at 140 BPM. Goepper isn't consciously thinking about BPM data, but he's intuitively using music as a tool to access specific mental states.

Nick Goepper's Olympic journey shows a progression from bronze to silver, with a potential gold in 2026. Estimated data for 2026 reflects his recent performance improvements.

Physical Recovery: The Infrastructure That Keeps Injuries at Bay

A 12-inch foam roller might be the most unsexy piece of equipment an elite athlete carries. It's not high-tech. It's not expensive. It's just dense foam in a cylinder shape. But Goepper brings one everywhere, and he uses it every single day.

Here's why: Freestyle skiing is high-impact. Every landing puts shock through your legs and lower back. Halfpipe skiing means rotating your spine under load, twisting your knees, and absorbing forces that reach 4-5 times your body weight. Your muscles get tight. Your fascia (the connective tissue surrounding muscles) gets restricted. Your mobility decreases. Your injury risk increases.

A foam roller breaks up those restrictions. When you roll your legs or back over it, you're applying sustained pressure to muscle tissue, which stimulates the nervous system to relax that tissue. It's not magic. It's applied pressure creating a physiological response.

What makes Goepper's choice interesting is that he specifically chose a 12-inch model. That's neither too short (which limits coverage) nor too long (which becomes hard to pack and travel with). It's the optimization point for an athlete who travels internationally.

He also notes something that people often overlook: "It wipes clean easily." This is practical wisdom. When you're traveling between mountain towns, hotels, and airports, your equipment gets dirty. A foam roller that doesn't absorb sweat and grime and require extensive cleaning is something you'll actually use consistently. Goepper even jokes that it works as a pillow in airports, which speaks to his approach of making recovery tools multi-functional.

The actual research on foam rolling is mixed—it helps with mobility and possibly reduces delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), but it's not a magic bullet. However, consistency matters. Goepper rolling out his legs for 10 minutes every day is almost certainly more valuable than him having the world's most advanced recovery tool that he uses once a month.

What's worth noting is that this is just one part of his recovery infrastructure. Foam rolling alone doesn't cut it at the Olympic level. But combined with sleep, nutrition, stretching, and professional massage therapy, it's one piece of a comprehensive approach to staying healthy through a season of high-impact training and competition.

Mental Preparation: Books as Brain Training

When Goepper talks about his reading, it's not casual book club conversation. It's deliberate mental training.

Right now he's reading Courage Is Calling by Ryan Holiday. If you haven't encountered Holiday's work, he's a author focused on practical Stoicism—ancient philosophy applied to modern life. Courage Is Calling specifically frames courage not as a personality trait you either have or don't have, but as a daily practice. You choose it. You build it. You exercise it.

The book draws on historical figures: Florence Nightingale's courage to challenge medical standards, Charles de Gaulle's courage to risk everything for principle, Martin Luther King Jr.'s courage to persist despite mortal threat. Each chapter is a case study in how courage actually functions in real situations.

Why would an Olympic athlete care about Stoic philosophy? Because Goepper has learned through painful experience that mindset is performance. When he burned out in 2022, it wasn't because he wasn't physically talented enough. It was because his mind broke before his body did. He had lost the ability to access courage—to take risks, to push hard, to handle the pressure without anxiety overwhelming everything.

Reading about courage as a daily practice isn't abstract for him. It's literal preparation. Every chapter is a reminder that courage is something he practices and builds, not something he should just naturally possess. During competition, when he's standing at the top of a halfpipe about to drop in, that mental framework matters.

What's interesting about his choice of reading material is that it's specific and intentional. He didn't grab a random motivational book. He chose something written by someone (Holiday) who has specifically thought about how Stoicism applies to modern performance. That's the kind of decision-making that separates elite athletes from good ones.

"When I'm traveling, I have a lot of time waiting around, and I like to read a lot," he explains. Travel for Olympics is long: getting to the airport hours early, waiting for flights, connecting through hubs, travel days that stretch into 24+ hours. Most athletes fill that time with Netflix or social media. Goepper uses it for deliberate mental training.

The Pit Viper BN5000 goggles excel in interchangeable lenses, ultrawide field of view, and optical clarity, making them ideal for varying light conditions and high-speed sports. Estimated data based on feature descriptions.

The Philosophy of Selective Intensity: Why Goepper Doesn't Train "All Out" Anymore

One of the most important things Goepper shared is something that younger athletes often miss: "When you get into your early thirties, you get better at turning it on and off."

This is the meta-skill that separates sustainable elite performance from burnout. Your body can handle high-intensity training for limited periods. It can't handle it forever. Most young athletes don't understand this. They train hard every single day, thinking that's what creates excellence. What it actually creates is eventual injury, overtraining syndrome, and burnout.

Goepper learned this the hard way. The years when he was winning medals (19-25) were years when he was always pushing hard. The button was always on. That's actually what makes you good at that age—you have the physical capacity to handle chronic high stress because you're young and your nervous system is resilient.

But at 31, that approach would destroy him. So he's completely restructured his training philosophy around something he calls knowing "exactly when to be a killer." Some days are 100%. Push as hard as possible. Go into what he calls "psychopath mode." Other days are 60%. Enough to maintain skills, but intentionally held back. And then some days are recovery days—deliberate, protected days where the goal is nothing.

The research backs this up. Periodized training (varying intensity intentionally rather than maintaining constant high intensity) produces better long-term results and fewer injuries than linear high-intensity approaches. It's why professional cyclists don't sprint hard every single day—they alternate hard days with easy days and recovery days. It's why runners do interval training, not just constant fast running.

What makes Goepper's approach even smarter is that he's not just training smarter, he's added confidence to the equation. "You get confident knowing exactly when to be a killer," he says. Because he's structured his training intentionally, he trusts that his peak performance days will be truly at peak. He's not wasting energy on maintaining a constant high intensity. He's pacing for a 6-month season plus the Olympics.

This is wisdom that took him nearly a decade to acquire, and it's one of the biggest reasons he's capable of performing at his best now, at 31, rather than having peaked at 25.

Competition Day Rituals: The Power of Consistency

Every elite athlete has competition day rituals. They're not superstitious, though they might look that way. They're actually sophisticated psychological tools for managing anxiety and accessing peak performance states.

Goepper's rituals are specific and probably way more detailed than he shares publicly. We know about the clean underwear thing. We know about the lens system. We know about music. But there's likely a whole structure around his day: what time he wakes up, what he eats, how long he spends warming up, what he visualizes, how he handles the walk to the halfpipe.

The reason rituals matter is because they reduce cognitive load. When you're already dealing with enormous pressure and anxiety, having to make 50 small decisions throughout your day drains your mental resources. Rituals eliminate decisions. You don't have to think: should I wear these goggles or those? You already know. Should I eat breakfast now or later? Ritual tells you. What underwear should I wear? The answer is clean, fresh underwear, every time.

This might sound OCD, but it's actually peak performance psychology. You're freeing up mental resources by removing micro-decisions, which means you have more cognitive capacity for the things that actually matter: focus, visualization, technical execution, and managing anxiety.

For the 2026 Olympics, Goepper probably has his competition day ritual down to probably a 15-20 hour structure. Wake at X time, eat Y breakfast, warm up specifically for Z minutes, change into specific layers at specific times, swap goggles at the last possible moment, visualize the run, walk to the halfpipe, one final mental check, and then go.

Breaking this routine would actually make him perform worse, not better. That might sound limiting, but it's actually liberating. He doesn't have to be creative or spontaneous on competition day. He has a system that works, and he executes it.

Estimated data shows metal is preferred for high-intensity sessions, while hip-hop aids in achieving flow states. Country and other genres are used less frequently but provide variety.

Recovery Beyond the Mountain: Hotel and Travel Optimization

Most people don't think about Olympic athletes' logistics between competitions. They show up, compete, then what? There's a whole infrastructure around recovering from high-level competition, and then preparing to compete again.

For a halfpipe skier, recovery means addressing the specific damage that halfpipe skiing does: lower back compression and rotation, hip and knee impact, and the accumulated stress of high speeds and high impacts. Goepper can't just rest—he has to actively work to restore mobility and reduce inflammation.

The foam roller we mentioned is part of this. But it's also sleep quality (which is why he's particular about hotels), nutrition (which he probably has locked down with a team of nutritionists), and targeted stretching. In modern Olympic programs, there are usually massage therapists, physical therapists, and athletic trainers on staff specifically for this.

But there's also the psychological component of recovery. After an intense competition, your nervous system is fried. You're running on adrenaline and cortisol. You need actual rest, not just physical recovery. That's where the music comes in again, and where his reading practice matters. He's not just recovering his body—he's recovering his mind.

"After the competition, he plans to decompress the same way he always does: Get a bowl of chili and be around loved ones." This is actually a perfect encapsulation of intelligent recovery. Not extreme. Not elaborate. Just comfort food and the people he cares about. That's literally how humans reduce stress. Warm food triggers the parasympathetic nervous system. Social connection with people you trust reduces cortisol and increases oxytocin.

Goepper isn't doing some fancy ice bath and biohacking protocol (or if he is, he doesn't mention it). He's doing the fundamentals: eating food that makes him feel good, spending time with people he cares about, reading about things that matter to him philosophically, using music to manage his emotional state.

The Mindset Shift at 31: Learning to Enjoy the Ride

There's a sentence that jumps out from everything Goepper has said: "I've been soaking up the little moments and enjoying the ride a bit more."

That's not something a 19-year-old Olympic bronze medalist would say. Nineteen-year-olds are chasing the next medal, the next gold, the next achievement. Thirty-one-year-old comebacks are different. They're either driven by something deeper (and potentially darker), or they're driven by actually enjoying the process.

Goepper's comeback is driven by the latter. After stepping back and getting help, he didn't return because he had something to prove. He returned because he realized he actually loved skiing, and he wanted to do it without the anxiety and pressure destroying his life.

This is a profound shift in motivation. It's the difference between approach motivation (moving toward goals) and avoidance motivation (moving away from fear). Young Goepper was probably running from pressure and fear. Thirty-one-year-old Goepper is running toward the joy of skiing.

That might sound like a small thing, but it's mechanically different in your nervous system. Approach motivation is sustainable. You can maintain it. Avoidance motivation is exhausting. You can do it for a while—like running away from something—but eventually you get tired and stop.

What makes his approach work for Olympic competition is that he's figured out how to access high intensity when he needs it ("psychopath mode") while maintaining psychological health the rest of the time. He doesn't have to be firing on all cylinders 24/7. He can be at 60% most of the time, knowing that he has trained and prepared well enough to access 100% when it matters.

This is the meta-lesson from Goepper's entire comeback and 2026 preparation. It's not about having the best gear (though good gear helps). It's not about training the hardest (though training matters). It's about understanding yourself well enough to know when to push and when to rest, and having the psychological stability to actually execute that plan.

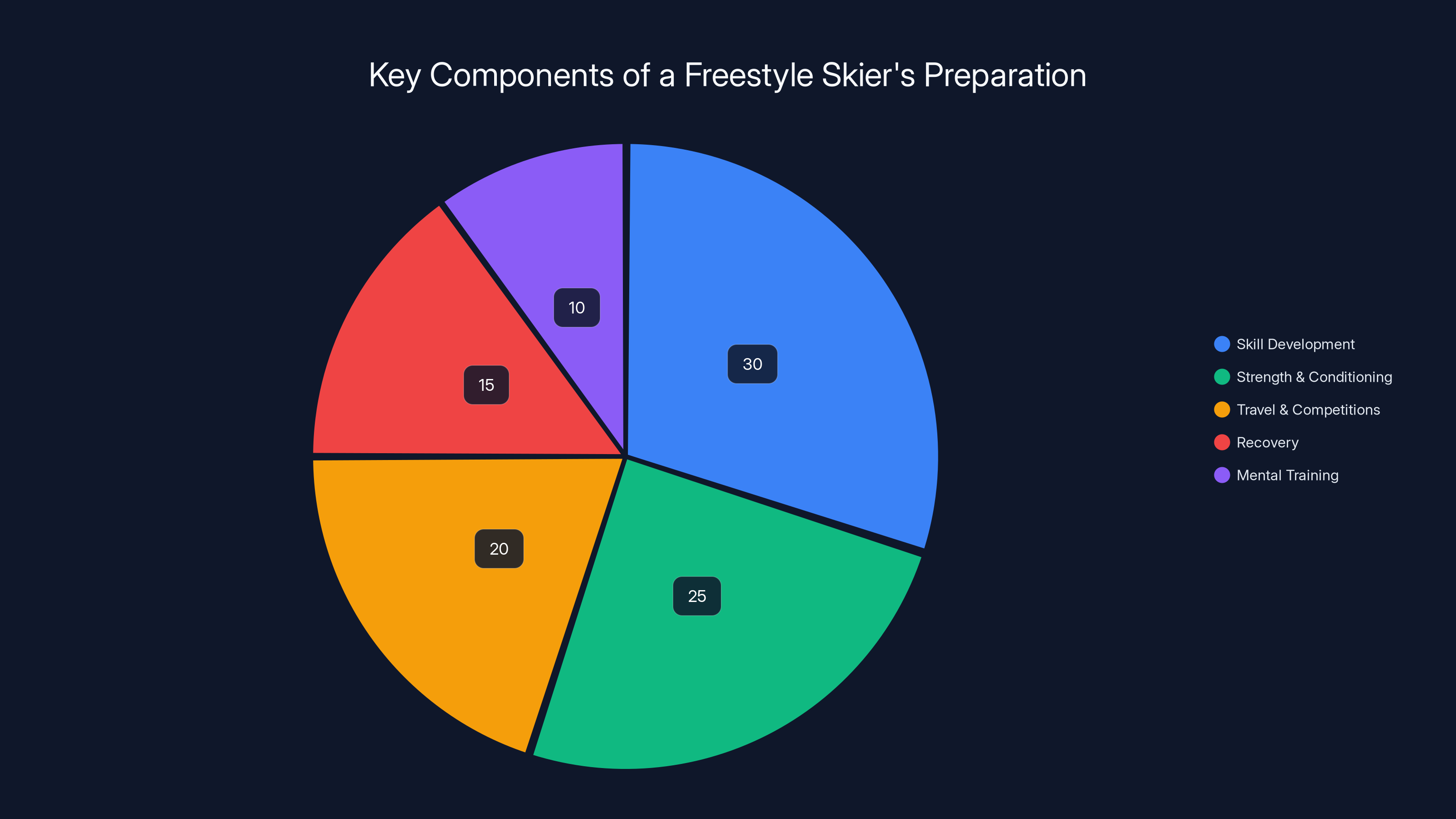

Freestyle skiers allocate significant time to skill development and strength training, with recovery and mental training also being crucial components. (Estimated data)

Preparing for Milano Cortina: What a Four-Time Olympian Actually Expects

Goepper's third Olympics was Beijing 2022, and now he's preparing for his fourth at Milano Cortina 2026. That's an unusual level of Olympic experience. Most athletes retire or wash out before reaching four. The fact that he came back after nearly completely stepping away makes his fourth Olympics even more meaningful.

What goes into preparation for that level of competition? The obvious things: training, technique refinement, conditioning. But also all the things we've discussed: gear optimization, recovery infrastructure, mental preparation, travel logistics, and environmental engineering to support optimal performance.

Milan-Cortina 2026 will be in February, which means Goepper is probably already in the final phases of his Olympic preparation. The strength and conditioning is mostly done. The technique is locked in. At this point, he's probably focused on peaking at exactly the right time, maintaining health without injury, and keeping his mental edge sharp without burning out again.

His halfpipe competitors are probably younger (halfpipe has been gaining talent rapidly). Many of them might not have Olympic experience. But Goepper has the advantage of knowing what to expect, knowing that he can deliver under pressure, and having been through this process enough times to trust his preparation.

There's also the intangible: he's less scared. Fear is probably a smaller factor for him now than it was at 19. He's made mistakes, gotten hurt, burned out, come back, and still succeeded. He knows he can recover from setbacks. That confidence matters more than any piece of equipment.

The Overlooked Factor: Mental Health as Performance Enhancement

Let's return to something mentioned at the beginning: Goepper is now "one of Team USA's biggest advocates for mental health." This isn't incidental to his athletic success. It's foundational.

The fact that he took months off, got therapy, and then came back stronger is almost statistically unusual in professional sports. Most athletes are trained to suppress mental health issues, to push through, to never admit struggle. The culture of many sports programs is exactly the opposite of what leads to long-term mental health.

Goepper explicitly broke that pattern. He admitted struggle. He got help. He adjusted his approach based on what he learned. And then he came back and started winning again.

What's important about this for understanding his 2026 preparation is that mental health infrastructure is part of his gear in the same way that goggles are. He's probably still seeing a therapist. He probably has someone (coach, trainer, therapist, or friend) he talks to when things get hard. He probably has gone through enough therapy to know his own nervous system well enough to recognize when he needs to adjust.

That's the kind of advantage that doesn't show up in technical analysis of halfpipe technique. But it's probably worth 5-10% of his competitive edge just in terms of not being paralyzed by anxiety the way he was before.

For other athletes (and honestly, just other people), this is worth noting: mental health work isn't weakness. It's actually performance enhancement. Knowing your own psychology, being able to regulate your nervous system, understanding your stress responses—these are practical skills that directly translate to better performance under pressure.

Goepper's willingness to be public about this is also worth noting. In a sport where image and toughness are traditionally valued, he's chosen to be vulnerable about struggling. That takes more courage, in the Stoic sense, than anything he'll do in the halfpipe.

Gear as Philosophy: Why Specifics Matter

There's a through-line in everything Goepper has shared about his setup: specificity. He doesn't have random stuff. He has the clean underwear because he thought about what he needs. He has the specific lenses because he thought about what conditions he faces and what he needs to see. He has the foam roller because he thought about what his body needs for recovery.

This is in contrast to how most people think about gear. They see what an elite person uses and they copy it, thinking the gear is the variable. But the gear is just the expression of intentional thinking.

For someone preparing for any high-level competition (or really, any challenging endeavor), the lesson is: think about what you actually need. Not what's trendy, not what's most expensive, not what the ads say. What do you actually need?

For Goepper, that's been a multi-year process of trial and error, of testing things and keeping what works. He didn't show up to his first Olympics with this system figured out. He built it over years of competing, failing, recovering, and learning.

Some of his gear is sponsored (he's a professional athlete, after all). But the stuff he talks about most passionately—the clean underwear, the foam roller, the books, the music—are his choices, not brand partnerships. That's where you see what actually matters to him.

The Path Forward: What We Can Learn From a Comeback

Goepper's comeback is useful for athletes, obviously. But it's also useful for anyone who's dealing with burnout, anxiety, or the pressure to always be performing at maximum capacity.

The core lesson is this: you can't sustain peak performance through chronic high intensity. You'll burn out. The only sustainable path is learning to vary your intensity intentionally, getting help when you need it, and building infrastructure (gear, routines, recovery tools, mental health support) that supports your performance instead of depleting it.

For Goepper specifically, that's meant going from a model where he was "on" 24/7, to a model where he's intentionally on or off depending on what the day requires. He's still extremely driven. He still competes at the highest level. But he's not destroying his mental health to get there.

The gear and the rituals and the recovery tools—these are all in service of that philosophy. Clean underwear isn't about being fancy. It's about starting each run with one variable under control. The foam roller isn't about having the world's best recovery tool. It's about actually maintaining mobility and reducing injury risk. The books aren't about being intellectual. They're about training his mind the same way he trains his body.

All of that adds up to someone who can drop into an Olympic halfpipe at 31, after nearly retiring, and perform at his absolute best. Not because he suddenly got more talented. But because he figured out how to be excellent while actually enjoying the process.

That's the difference between a 19-year-old Olympian and a 31-year-old Olympian. Experience. Wisdom. And a much clearer understanding of what's actually necessary versus what's just noise.

FAQ

What is a freestyle skier's preparation schedule like?

Freestyle skiers like Goepper typically prepare for major competitions over a full season (August through February) with structured training blocks. Their schedule includes skill development in slopestyle and halfpipe, strength and conditioning training, travel to World Cup events, and intentional recovery periods. The final 4-6 weeks before an Olympic Games are typically focused on peaking at exactly the right time—maintaining fitness while preventing overtraining and injury.

How important is mental health in elite athletic performance?

Mental health is foundational to elite performance. Research shows that athletes who address anxiety, burnout, and psychological stress perform measurably better under pressure than those who ignore mental health. Goepper's experience demonstrates that therapy and intentional mental training (through reading, meditation, or other practices) can be the difference between a short career ending in burnout versus a sustainable career spanning decades. The psychological ability to manage pressure, regulate anxiety, and access peak performance states is often what separates good athletes from great ones.

What role does recovery play in competitive skiing?

Recovery is critical in competitive skiing because the sport involves repeated high-impact landings, rotational forces on the spine, and accumulated fatigue from training multiple runs per day. Recovery tools like foam rollers address muscle tension and mobility. Sleep, nutrition, and mental rest address systemic fatigue. Professional athletes typically use a combination of these approaches, rotating between high-intensity training days and deliberate recovery days. Goepper's approach emphasizes consistency in recovery practices rather than exotic biohacking—basic tools used daily matter more than expensive tools used occasionally.

Why do elite athletes have specific pre-competition rituals?

Pre-competition rituals reduce cognitive load by eliminating small decisions, which frees up mental resources for focus and anxiety management. They also create a sense of control and familiarity during a high-stress situation. Goepper's rituals (clean underwear, specific goggles for conditions, music, reading) aren't superstitions—they're psychological tools that help him access his peak performance state. Research on athletic performance shows that consistent pre-competition routines measurably reduce anxiety and improve performance under pressure.

How has professional skiing equipment changed over recent years?

Skiing equipment has evolved significantly with improvements in materials, lens technology, and recovery tools. Modern ski goggles use advanced lens coatings that prevent fogging and reduce distortion better than older models. Moisture-wicking base layers have become more sophisticated. Recovery tools are increasingly portable and effective. However, the fundamentals remain the same: equipment matters less than consistency, proper technique, and mental preparation. Goepper's choice of gear reflects long-term trends toward more specialized, multi-functional equipment that supports specific training and competition needs.

What distinguishes a four-time Olympian from athletes who compete once or twice?

Athletes who reach four Olympic Games typically have longevity factors: durability to avoid career-ending injuries, sustainable training approaches that don't lead to burnout, ability to adapt as they age, and deep experience managing the specific stresses of Olympic competition. Goepper's distinction is also his willingness to step back and rebuild his mental health, then return stronger. Most athletes either retire or burn out. Returning at 31 and competing at his best level is genuinely unusual and speaks to his psychological resilience and self-awareness.

Can everyday athletes benefit from Goepper's approach?

Absolutely. The core principles—intentional variation in training intensity, consistent recovery practices, mental health support, and specific pre-performance rituals—apply to any athlete or person dealing with high stress and performance pressure. You don't need to be an Olympian to benefit from foam rolling, from reading materials that help you manage anxiety, from creating routines that reduce decision fatigue, or from getting help when you're overwhelmed. The principles scale down to any level of athletic competition or challenging endeavor.

The Complete Equipment Rundown: Everything Goepper Carries

Here's a consolidated list of the specific items Goepper mentioned, with context on why each matters:

Base Layer & Foundation

- Nike Dri-FIT Boxer Briefs (3-pack): Moisture management, comfort, clean feeling before runs

- Quality base layers: Not specifically mentioned, but implied as essential for temperature management

Vision & Light Management

- Pit Viper BN5000 Goggles with Magic Magnet lens system: Interchangeable lenses, ultrawide field of view, anti-fog technology

- Blackout lens: For peak daylight conditions and snow glare

- Clear lens: For nighttime sessions under artificial light

Audio & Mental State

- Sony SRS-XB100 Compact Bluetooth Speaker: Portable, water-resistant, 16-hour battery life, quality bass

Physical Recovery

- 12-inch foam roller: Muscle tissue release, fascia mobilization, portable, wipe-clean design

Mental Preparation

- "Courage Is Calling" by Ryan Holiday: Stoic philosophy applied to modern performance, case studies in courage

Implied But Not Detailed

- Skis (specific model not mentioned)

- Ski boots (specific model not mentioned)

- Skiing jacket and pants (specific model not mentioned)

- Thermal layers (specific model not mentioned)

- Athletic socks (specific model not mentioned)

- Professional massage and physical therapy (accessed through Team USA)

What stands out is that Goepper doesn't mention having exotic equipment that's unique to him. His setup is available to most serious skiers. What makes it effective is how he uses it: consistently, intentionally, and in service of a larger philosophy about sustainable high performance.

The Mindset Behind the Gear: Integration, Not Isolation

It's tempting to look at Goepper's equipment and think: "If I get that speaker, those goggles, and that foam roller, I'll perform better." But that misses the point entirely.

The gear works because it's integrated into a comprehensive system: training philosophy, recovery practices, mental preparation, pre-competition rituals, and a sustainable approach to intensity variation. The speaker matters because music is part of his mental state management system. The foam roller matters because it's used consistently as part of his daily recovery routine. The goggles matter because they're part of a larger system of optimizing his vision under different conditions.

Taking one piece out of that system and thinking it will solve your problems is like taking a formula out of context and expecting it to describe the entire system.

For anyone looking to optimize their own performance (athletic or otherwise), the lesson is: understand what you're actually trying to optimize for, then design a system that supports that. Don't just copy someone else's gear.

Looking Ahead to Milano Cortina 2026

When the 2026 Winter Olympics arrive in Milan, Italy, Goepper will show up with the gear we've discussed, plus probably hundreds of hours of halfpipe training, plus the mental framework he's built over the past few years, plus the experience of three previous Olympics, plus the knowledge that he's come back from being completely burned out.

That combination is formidable. He won't have the physical advantages of a 19-year-old. But he'll have everything else: experience, wisdom, durability, mental clarity, and a sustainable approach to high performance.

The question isn't whether he has what it takes. He's already proven that. The question is whether he can stay healthy and mentally sharp for the final months of training and then execute perfectly when it matters. That's the burden of being a four-time Olympian: you've done it before, so you know exactly what can go wrong.

But if anyone has the tools—literal tools like goggles and foam rollers, and metaphorical tools like mental health support and Stoic philosophy—to handle that pressure, it's Goepper.

He'll probably eat chili with the people he loves after his runs. He'll probably read about courage and practice turning on and off his intensity at will. He probably already has his competition day ritual locked down to the minute. And on the day it matters, when he drops into the halfpipe at one of the world's biggest sporting events, all of that will be there with him.

That's what preparation looks like from the inside.

Key Takeaways

- Elite athletes optimize every detail from underwear to goggles because small psychological anchors reduce anxiety and free cognitive resources for performance

- Sustainable peak performance requires intentional variation in training intensity rather than constant high-intensity efforts, which prevents burnout and injury

- Mental health support is not weakness but foundational performance enhancement; Goepper's therapy and psychological work enabled his Olympic comeback

- Recovery infrastructure matters more than exotic biohacking; consistent basic tools (foam rolling, sleep, quality nutrition) used daily outperform expensive tools used occasionally

- Four-time Olympian success comes from experience-gained wisdom about when to push and when to rest, not from becoming more physically talented with age

![Nick Goepper's Olympic Starter Pack: Gear, Mindset & Recovery [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nick-goepper-s-olympic-starter-pack-gear-mindset-recovery-20/image-1-1770120609738.jpg)