Winter Olympics Discontinued Sports: The Events You Won't See in 2026

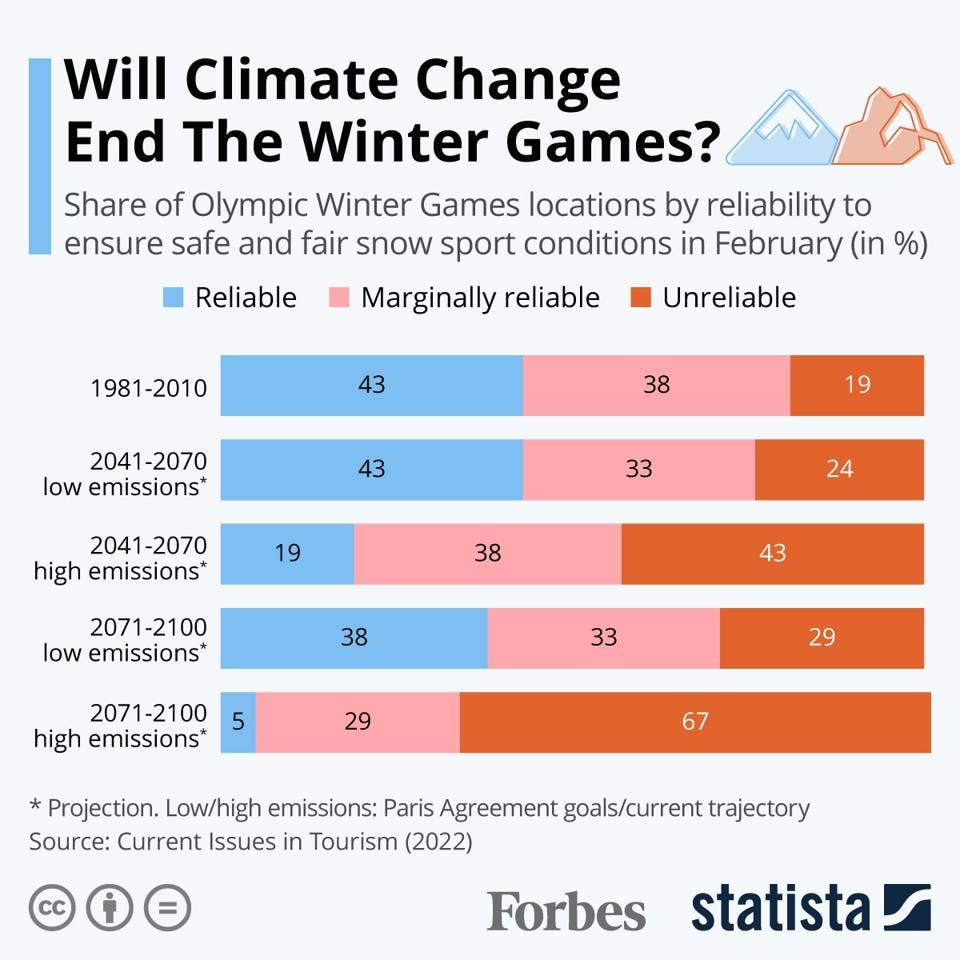

The Winter Olympics aren't set in stone. You might think that once a sport earns its place on the world's biggest winter stage, it's locked in for good. But that's not how it works. Over the past 100 years, the Olympic Games have been a constantly shifting stage where sports come and go. Some last decades. Others disappear after a single appearance.

When the first Winter Olympics took place in 1924 in Chamonix, France, they looked dramatically different from what we'll see in Milan-Cortina in 2026. Back then, the lineup included military patrols shooting rifles while cross-country skiing. Now we have halfpipe snowboarding and freestyle aerial skiing. The transformation has been radical.

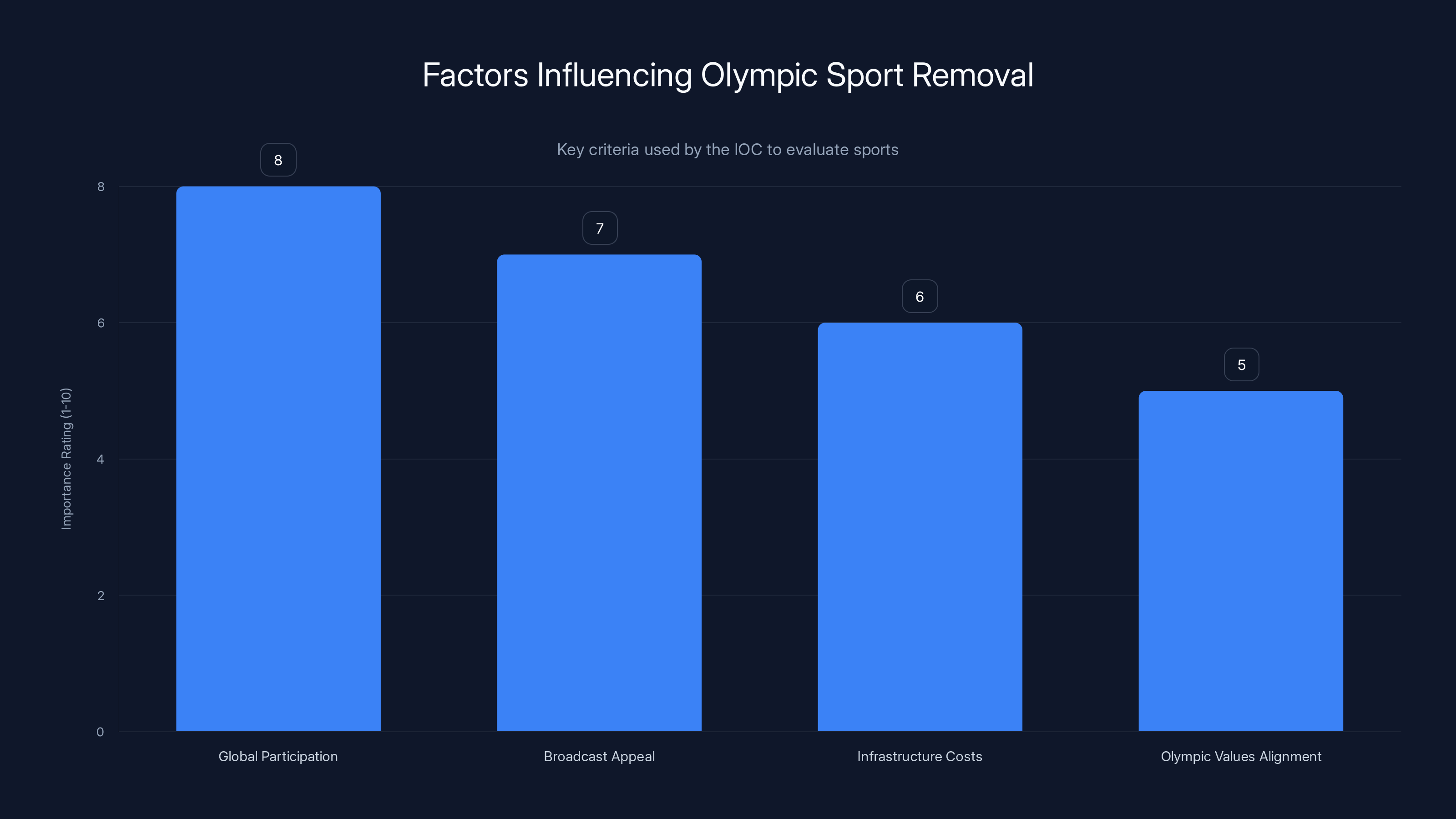

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) doesn't just add and remove sports randomly. They consider global participation, gender equity, cost of hosting, infrastructure requirements, and how well sports align with Olympic values. Sometimes sports make it through a few Olympics before fading away. Sometimes they're demonstration events that never get official status. And sometimes, like ski ballet, they become so weird and outdated that they're abandoned entirely, even though competitors genuinely loved them.

Understanding which sports came and went tells us something important about how the Olympics evolve. It shows us what society cares about, how athletic culture shifts, and why some niche winter activities never quite caught on globally. The 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan-Cortina will feature 109 events across 15 sports. But for every sport that made the cut, there are fascinating stories of events that didn't.

Let's look at the sports that won't be competing in 2026, and more importantly, why they're gone. Some of these events are genuinely weird. Others were ahead of their time or simply couldn't sustain global interest. All of them reveal something about Olympic history.

Ski Ballet: When Skiing Became Performance Art

Imagine strapping on skis and then performing a choreographed dance routine down a snowy slope while a live orchestra plays dramatic music. That's essentially what ski ballet was, and it existed as an official Olympic event not that long ago.

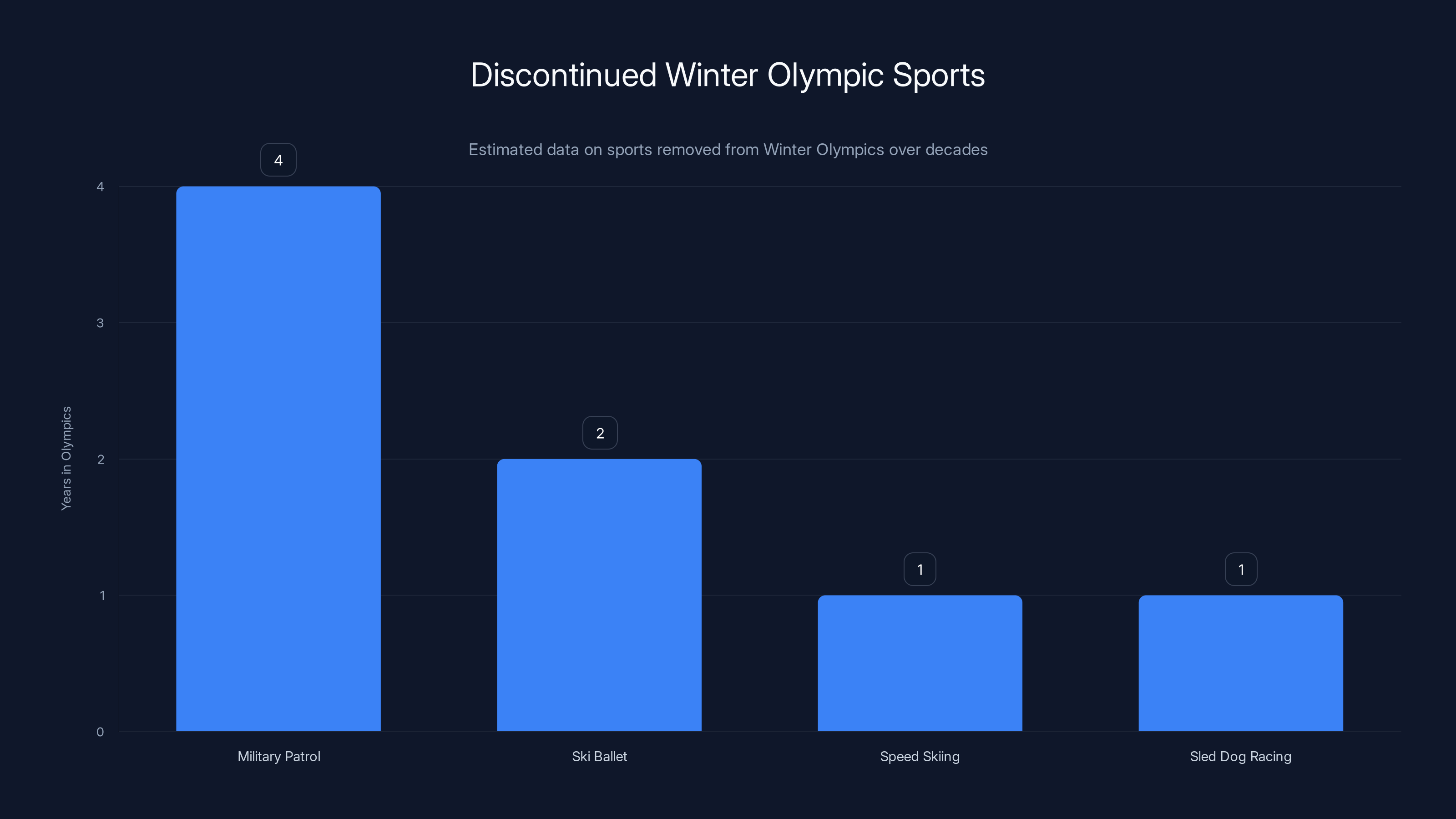

Ski ballet emerged during the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, Canada, and continued at the 1992 Games in Albertville, France. The event wasn't a medal discipline in the traditional sense, but it was part of the freestyle skiing family and drew significant attention. The sport came directly out of 1970s counterculture and the freestyle skiing movement, which itself was a rebellion against the rigid, rule-bound world of traditional competitive skiing.

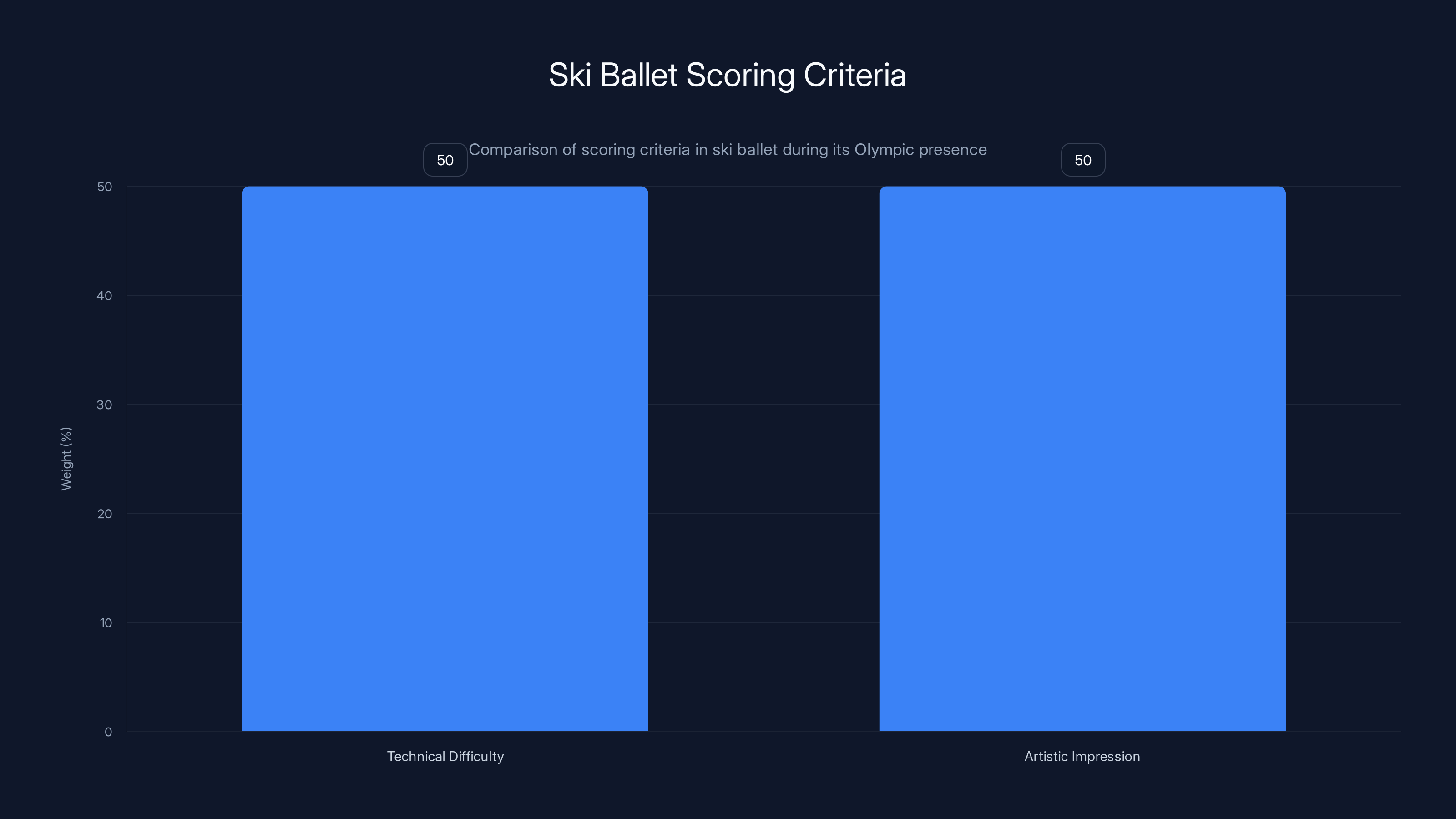

In ski ballet, athletes performed a choreographed routine on a relatively flat or gently sloped course. They'd execute jumps, spins, and dance-like movements while staying synchronized to music. A panel of judges scored performances based on two criteria: technical difficulty (the actual tricks and movements) and artistic impression (how well they flowed and connected). It was like figure skating, except on snow, at speed, going downhill.

The appeal was obvious to anyone who appreciated artistry in sport. Skiers could express themselves, show creativity, and make skiing look almost balletic. But here's where it gets complicated. Ski ballet was never mainstream. It lacked the adrenaline rush of racing competitions. Casual fans didn't understand the scoring system. And the event had a distinctly 1980s aesthetic that didn't age well.

By the mid-1990s, the IOC decided ski ballet wasn't cutting it. They retired it in favor of a related event called mogul skiing, which combined athletic performance with some artistic elements but emphasized tricks and speed over pure choreography. The mogul skiers launched themselves off bumps (moguls) and performed aerial maneuvers. It felt fresher, more exciting, and had clearer appeal to a broader audience.

But ski ballet didn't vanish entirely. Its spirit lives on in modern freestyle skiing disciplines like slopestyle and big air, where athletes string together creative lines and tricks while racing down mountains. You can see the DNA of ski ballet in how modern freestyle skiers approach their sport with personality and style, even if judges now care more about speed and amplitude than artistry.

The IOC evaluates sports based on global participation, broadcast appeal, infrastructure costs, and alignment with Olympic values. Estimated data.

Bandy: The Sport That Looked Like Hockey But Wasn't Quite Right

Bandy appeared at the 1952 Winter Olympics in Oslo as a demonstration sport. It looked deceptively simple: two teams, a ball, and sticks. But everything about it was different from hockey.

In bandy, each team fielded 11 players on a much larger ice surface (around 100 meters long and 60 meters wide). Players used curved sticks (more curved than hockey sticks) to hit a ball instead of a puck. The goalies could only use their hands to defend, which was a major difference from hockey. Teams competed in two 45-minute halves instead of three periods.

The sport originated in Scandinavia and Russia, where it developed its own passionate following. It still exists today, particularly in Russia, Finland, and Sweden, with active professional leagues. But it never caught on globally the way hockey did. The challenge was simple: hockey had already established itself as the winter ice sport. Adding bandy felt redundant to international audiences who didn't grow up playing it.

The 1952 Oslo demonstration turned out to be bandy's only Olympic appearance. The IOC recognized that building a global sport requires sustained participation across multiple countries and continents. Bandy was strong in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, but outside those regions, it barely existed. Without the infrastructure, grassroots participation, and international demand in places like North America, Asia, and Western Europe, bandy couldn't make the case for being an official Olympic event.

Today, bandy still thrives in its traditional strongholds. Russian bandy is particularly intense, with professional teams and dedicated fans. But internationally, it remains a niche sport. The Olympic window closed decades ago and never reopened. It's a reminder that regional popularity doesn't automatically translate to global Olympic inclusion.

Ski ballet performances were judged equally on technical difficulty and artistic impression, highlighting the balance between athletic skill and artistic expression. Estimated data based on typical judging criteria.

Equestrian Skijoring: The Sport That Combined Horses and Skis in the Most Impractical Way

Now here's a sport that sounds completely made up but actually happened. Equestrian skijoring involved skiers being pulled across snow by galloping horses. Yes, you read that right. A person on skis, holding a rope, being dragged by a horse at speed across a snowy landscape.

The sport made exactly one appearance at the Olympics during the 1928 Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland. It was a demonstration event only, no medals awarded. The event was brief, strange, and clearly an experiment that nobody needed to repeat. It combined the unpredictability of horses with the coordination required for skiing, creating a sport that was more dangerous than exciting.

The origins of equestrian skijoring trace back to Central Asia and parts of Eastern Europe, where it developed as a practical way for people to travel across snowy terrain. Having a horse do the pulling made sense if you lived in a rural mountain area and needed to get somewhere quickly. But as a competitive sport? As an Olympic event? The appeal was minimal.

What's interesting about equestrian skijoring is that it represents a specific moment in Olympic history when the IOC was more willing to experiment with unusual sports. The early Winter Olympics were smaller, less globally broadcast, and focused less on professionalism and more on experimental novelty. Once the Olympics became bigger, more organized, and more commercial, there was no room for something as niche and impractical as skijoring.

The sport still exists in very limited circles in parts of Central Asia and Eastern Europe, but it never gained traction anywhere else. One Olympic appearance was enough to establish that equestrian skijoring simply wasn't the future of winter sports.

Sled Dog Racing: The Forgotten Demonstration Sport of Lake Placid

In 1932, the Winter Olympics came to Lake Placid, New York. Along with the skiing, skating, and ice hockey, organizers added a demonstration event that seemed to fit the snowy setting perfectly: sled dog racing.

The event was straightforward in concept. A team of six sled dogs would pull an athlete across a 40-kilometer course. The sport had real roots in North America, particularly in Alaska and Canada, where sled dogs were essential for transportation in remote areas. Mushers (the drivers/athletes) developed incredible skills in managing their teams, reading the conditions, and maintaining speed across varied terrain.

Sled dog racing at the 1932 Lake Placid Olympics was legitimately impressive. Teams reached speeds of up to 30 kilometers per hour pulling heavy loads across 40 kilometers. The athleticism required from both dogs and mushers was genuine. If a dog got injured during the race, the musher had to carry it on the sled for the remaining distance, which added real stakes to the competition.

But here's why it didn't stick: sled dog racing required completely different infrastructure, venues, and expertise than the rest of the Winter Olympics. You couldn't just include it in a host city's existing ice hockey and skiing facilities. You needed large swaths of snow-covered land, kennels, specialized dog teams, and experienced mushers. The cost-to-benefit ratio didn't work.

Moreover, sled dog racing lacked the broadcast appeal of other winter sports. Viewers watching on TV (once TV coverage became standard) would rather watch speed skating's excitement or figure skating's elegance than follow dogs running across frozen landscape for hours. The sport couldn't generate the spectacle that Olympic audiences expected.

Today, sled dog racing thrives in Alaska and parts of Canada. The Iditarod Sled Dog Race, which starts in Anchorage every March, is one of North America's most grueling endurance events. But the Olympic moment for sled dog racing came and went after that single 1932 demonstration.

Estimated data shows that sports like Military Patrol and Ski Ballet were part of the Olympics for a few years before being discontinued, reflecting changing priorities and interests.

Military Patrol: The Original Biathlon Ancestor

Before biathlon existed as we know it, there was military patrol. The sport debuted at the very first Winter Olympics in 1924 in Chamonix, France, and it was exactly what the name suggests: military personnel competing while wearing military uniforms.

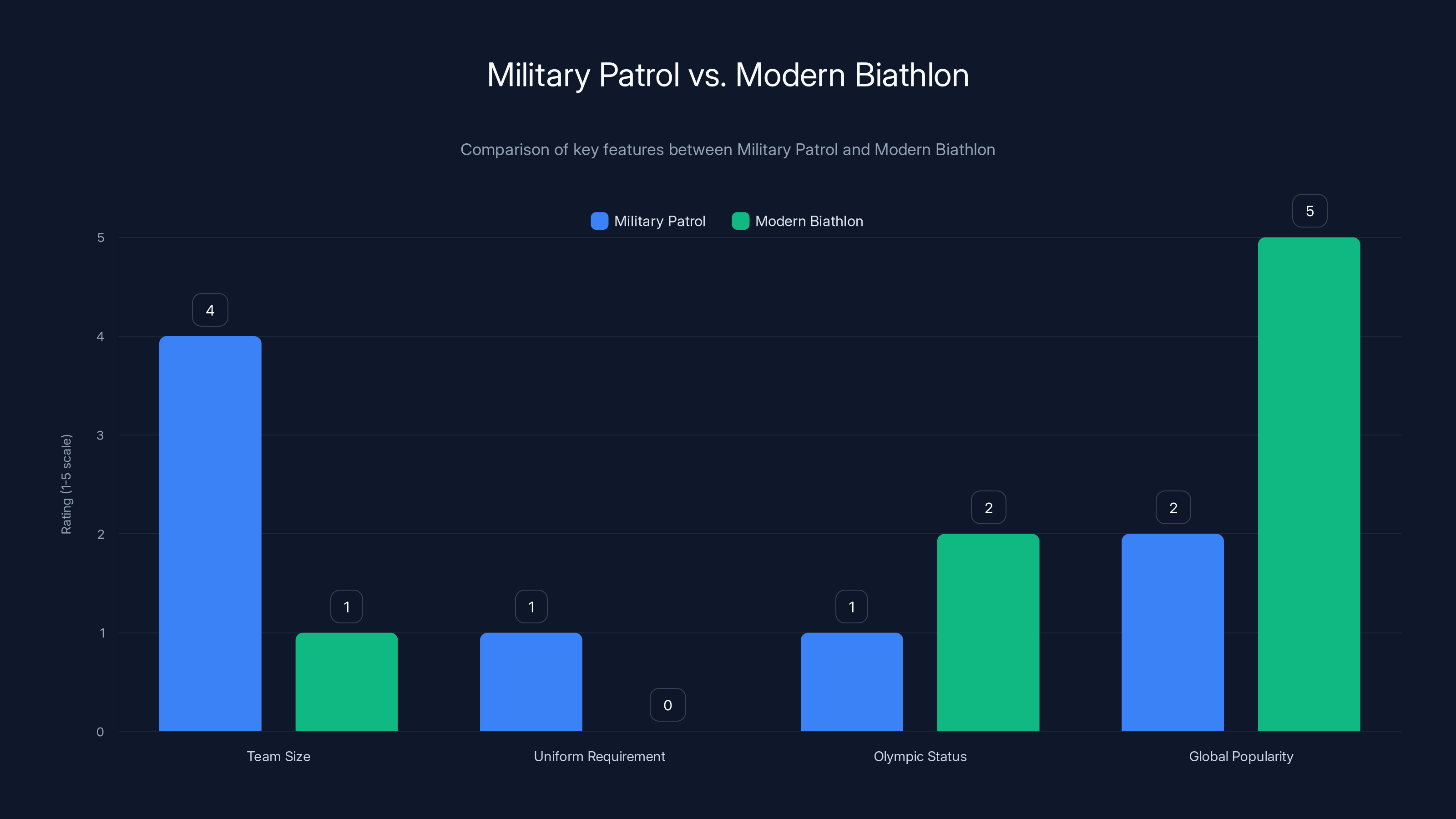

Military patrol combined cross-country skiing with rifle shooting, much like modern biathlon does. But there were crucial differences. Teams consisted of four people (called a patrol), and all members had to wear full military uniforms during competition. This wasn't just ceremonial either. The military uniforms came with all their traditional gear, making the athletes work harder and adding real tactical elements to the race.

Switzerland dominated military patrol at the 1924 Chamonix Olympics, winning gold. They became the only country to ever win gold in this event because the IOC didn't keep it as a consistent Olympic sport. It appeared again as a demonstration event in 1928, 1936, and 1948, but never gained status as an official medal event.

The sport eventually evolved into modern biathlon, which stripped away the military uniform requirement and streamlined the format. Biathlon became faster, cleaner, and more universal. It didn't require athletes to be military personnel. It didn't require special uniforms. It was just skiing plus shooting, and that simplification made it infinitely more scalable globally.

Military patrol represented a specific era when the Olympics were closely tied to military institutions and national pride expressed through martial competition. As the Olympics modernized and became more focused on athletic performance than military demonstration, military patrol fell away. The biathlon that replaced it kept the core sporting challenge while removing the military ceremonialism.

Interestingly, military patrol hasn't completely vanished. It still exists as a competition in some countries, particularly in the Alpine region. But the Olympic era of military patrol ended definitively decades ago, replaced by a sport that achieved what military patrol was trying to do, but better.

Winter Pentathlon: The Five-Sport Challenge Nobody Needed

The modern pentathlon is a weird Olympic event: shooting, fencing, swimming, horse jumping, and cross-country running all in one day. The ancient pentathlon at the original Olympic Games supposedly trained soldiers for warfare. The modern version is... less clear on its purpose.

There was also a winter pentathlon, which combined cross-country skiing, rifle shooting, downhill skiing, cross-country ski racing, and ski jumping. The event existed in limited forms but never achieved official Olympic status. It appeared sporadically but couldn't build the consistent global participation required for Olympic inclusion.

Winter pentathlon suffered from the same problem that kills many experimental Olympic sports: it required athletes to train in too many different disciplines. A world-class ski jumper won't necessarily be a world-class cross-country skier. A rifle marksman isn't automatically a downhill specialist. The event punished generalists and favored athletes with unusually broad skill sets, which limited the competitive pool.

Modern pentathlon still exists as an Olympic sport, but winter pentathlon faded away. The lesson: if you want a permanent Olympic spot, you need either a narrow, specialized discipline that many countries can develop expertise in, or you need such universal appeal that millions of people play it recreationally worldwide. Winter pentathlon satisfied neither requirement.

Military Patrol required teams of 4 in full uniform and was less popular globally, whereas Modern Biathlon is more streamlined and widely recognized. Estimated data.

Ice Stock Sport: The Curling-Adjacent Event That Didn't Quite Make It

Ice stock sport (also called Eisstöcke) is essentially curling's weirder cousin. Instead of sliding a large stone across ice, players throw wooden or plastic biscuit-shaped objects. The rules are similar to curling in some ways, but different in others. It's faster, requires different technique, and has its own strategic depth.

Ice stock sport appeared as a demonstration sport at a few Winter Olympics but never achieved official status. It has a passionate following in Central Europe, particularly in Germany and Austria, where it's been played for centuries. But like bandy and equestrian skijoring, it lacked the global reach needed for permanent Olympic inclusion.

Why didn't ice stock sport replace or supplement curling? Partly because curling already owned that niche, and partly because curling has exponentially more players worldwide. But there's also the broadcast problem. Curling has become increasingly popular on television because it's slow enough that viewers can understand the strategy but fast enough to maintain interest. Ice stock sport never achieved that magic broadcasting formula.

Curling, ironically, almost died as an Olympic sport itself decades ago. It was demonstration-only for years before finally gaining official medal status. The difference was that curling had grassroots popularity in Canada, Scotland, and other regions. Once curling got televised properly, it found an audience. Ice stock sport never had that break.

Skeleton's Near-Death Experience and Resurrection

Skeleton is a sport where athletes push a sled at high speed, jump in headfirst, and hurtle down an icy track at 90 kilometers per hour. It's absolutely insane and absolutely riveting to watch.

But skeleton almost disappeared from the Olympics entirely. It was an official sport for decades, but by the 1990s, the IOC had removed it from the Olympic program. The governing bodies fought hard to bring it back, arguing that skeleton had unique appeal and legitimate athletic merit. Skeleton returned as a demonstration sport and eventually regained full Olympic status.

Skeleton's near-death experience shows that not all discontinued sports are forgotten forever. Sports can be revived if they develop the right constituency, gain TV appeal, and make the case for why they belong in the modern Olympics. But this is rare. Most discontinued sports never come back.

Estimated data suggests a gradual increase in the number of Winter Olympic sports over the next century, reflecting the dynamic nature of the Games.

Bobsleigh's Evolution: From Niche to Global

Bobsleigh has been part of the Winter Olympics since the beginning, but it's transformed dramatically. It started as a sport for the ultra-wealthy in Switzerland, where people literally invented sleds and raced them down natural ice channels. Early Olympic bobsleigh was exclusive, expensive, and hard to access.

Over time, bobsleigh evolved. Countries invested in training facilities. The sport became more accessible. Rule changes allowed different sled configurations. Women's bobsleigh was added to the Olympics in 2002, expanding the sport dramatically. Today, bobsleigh has athletes from diverse backgrounds and nations, whereas once it was dominated by wealthy Europeans.

Bobsleigh's transformation shows how a sport can survive and thrive by adapting. Unlike equestrian skijoring or military patrol, bobsleigh was willing to change its nature, expand its accessibility, and build global participation. That flexibility kept it alive.

The Pattern: Why Sports Get Dropped

Looking at all these discontinued sports, patterns emerge. Sports get dropped when they fail to achieve sufficient global participation, cost too much relative to their popularity, require too much specialized infrastructure, or can't generate broadcast appeal.

Equestrian skijoring was too niche and dangerous. Ski ballet was too artsy and required specific venues. Bandy couldn't compete with hockey's dominance. Military patrol became obsolete when the Olympics moved away from military symbolism. Sled dog racing was logistically impossible.

But here's what's interesting: some of these sports might have survived if the world had changed slightly differently. If ski ballet had emerged in the Instagram era, would it have found a visual audience? If bandy had stronger presence in North America and Asia, would it have made the cut? If equestrian skijoring had better safety equipment and tracks, would modern Olympic organizers have kept it?

The Olympics aren't immune to path dependency. Once a sport gets dropped, it's nearly impossible to revive it because the global infrastructure never develops. You need athletes, coaches, training programs, national federations, and clubs across dozens of countries. You can't build that if the Olympic opportunity disappears.

The Sports That Almost Disappeared

Some modern Olympic sports came dangerously close to getting cut. Curling was demonstration-only for years before gaining full status in 1998. Figure skating was nearly abandoned in the 1980s before being revived by television networks who realized its narrative appeal. Freestyle skiing was originally considered too dangerous and artsy to be legitimate Olympic sport.

Curling's survival is particularly instructive. The sport seemed boring to casual viewers in the 1970s and 1980s. The ice surface didn't look exciting on television. The pace seemed too slow. But curling had dedicated players in Canada, Scotland, and Scandinavia. The sport had authentic competition and strategic depth. Once television networks figured out how to cover it properly, curling exploded in popularity. Suddenly, millions of people understood strategy and wanted to watch the nuance.

The 2026 Winter Olympics: What Made the Cut?

The 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan-Cortina will feature 109 events across 15 sports. These include the classics: alpine skiing, cross-country skiing, figure skating, ice hockey, speed skating, and freestyle skiing. They also include newer sports like snowboarding, ski jumping, biathlon, and curling.

Recently added sports that barely made it include skateboarding and snowboard slopestyle. These survived because they had massive youth participation globally. Skateboarding has millions of practitioners worldwide and generations of culture. Snowboard slopestyle combined trick elements with racing elements, appealing to diverse audiences.

Missing from 2026? Ice stock sport, bandy, military patrol, equestrian skijoring, ski ballet, and sled dog racing won't be competing. These sports had their moment, and the world moved on.

Why the IOC Keeps Changing Things

The International Olympic Committee faces real constraints. Host cities can't build unlimited facilities. Venues must be reusable for post-Olympic life. The number of competing athletes must be manageable. Television broadcasters have limited time slots. Viewers' attention spans are finite.

Adding or removing a sport requires balancing tradition, athlete interest, fan appeal, infrastructure costs, and global participation. It's genuinely complicated. The IOC isn't randomly dropping sports. They're making calculated decisions based on what they think will make the Olympics sustainable, interesting, and globally relevant.

The problem is that these decisions are never permanent. As society changes, as new sports emerge, as different countries develop different athletic priorities, the Olympic program shifts. This creates winners and losers. Some sports like snowboarding (which seemed ridiculous in 1990) become permanent fixtures. Others like ski ballet (which seemed innovative in 1988) become historical footnotes.

The Future: What Might Disappear Next?

Figuring out which modern Olympic sports might disappear is speculative, but we can identify vulnerable ones based on current trends. Sports with declining participation, minimal television ratings, high costs, or limited global spread are at risk.

Figure skating seems safe because it has massive viewership and participation. Alpine skiing and cross-country skiing have centuries of tradition and strong international participation. Snowboarding and freestyle skiing are expanding. But if one of the more niche sports like race walk or modern pentathlon continued to decline in participation, the IOC wouldn't hesitate to cut them.

Equally interesting: what new sports might join by 2030 or 2034? The IOC has shown willingness to add skateboarding, surfing (for summer games), and other youth-focused sports. Will breakdancing or other emerging disciplines eventually make it to the Olympics? How about extreme skiing variants or new snowboard disciplines?

The Olympic program isn't static. It's constantly negotiating between tradition and innovation, between inclusive representation and manageable scope, between what was and what could be.

Learning from Olympic History

The discontinued Winter Olympics sports teach us something broader about how institutions evolve. Change happens slowly at first, then suddenly. The Olympics seemed eternal and unchangeable until you realize that half of what you watch today didn't exist a few decades ago, and half of what was there a few decades ago is completely gone.

Sports that can't adapt disappear. Disciplines that can't build global participation fade away. Events that cost too much relative to their popularity get cut. But sports that evolve, that build passionate fan bases, that find television appeal, and that develop genuine international participation can thrive for generations.

Looking back at ski ballet, you might think it was a failure. But in another sense, it succeeded. It showed that freestyle skiing could incorporate artistry and creativity. Those lessons survived in modern freestyle events even after ski ballet itself didn't. Equestrian skijoring was impractical, but it showed the Olympic spirit of experimentation. Military patrol evolved into biathlon, which is infinitely more successful.

Nothing in the Olympic program is guaranteed. Everything we watch today could theoretically disappear if circumstances changed. That volatility is actually part of what makes the Olympics interesting. The Games aren't museum pieces. They're living, evolving competitions that reflect what the world cares about at any given moment.

Conclusion: The Olympics Keep Moving Forward

The 2026 Winter Olympics will be spectacular. Athletes will compete at levels of skill and dedication that seem superhuman. But the event will also be completely different from what we'll see in 2030 or 2034. New sports will likely be added. Current sports might be modified or moved. The Olympic program will continue its endless evolution.

Understanding the sports that didn't make it helps us appreciate the ones that did. It shows us that Olympic status isn't permanent. It demonstrates that sports need global participation, authentic fan interest, and practical feasibility to survive long-term. And it reminds us that the Olympics are not timeless. They're snapshots of what the world values at particular historical moments.

In 100 years, people might look back at the 2026 Winter Olympics and be shocked by what's included. Freestyle skiing might seem primitive compared to whatever sport replaces it. Figure skating might be transformed into something we wouldn't recognize. New winter sports developed in places we haven't even imagined yet might be the marquee events of the 2126 Winter Olympics.

The history of discontinued Winter Olympic sports isn't a story of failures. It's a story of evolution. Sports come, sports go. Some were ahead of their time. Some were products of their era that couldn't adapt. Some faced impossible logistics. Some simply couldn't build the global infrastructure required for Olympic inclusion.

But that constant change, that willingness to experiment and evolve, is part of what makes the Olympics work. The Games remain relevant because they're willing to change. The sports that survive are the ones that matter most to the world at any given moment. And the ones that disappear? Well, they become history. Fascinating, weird, instructive history that teaches us how sports, cultures, and institutions actually evolve.

FAQ

Why do sports get removed from the Winter Olympics?

Sports are removed when they fail to achieve sufficient global participation, require too much expensive infrastructure relative to their popularity, can't generate adequate television audience, or no longer align with modern Olympic values. The International Olympic Committee evaluates each sport's viability before each Games, considering factors like athlete participation across multiple countries, broadcast appeal, hosting costs, and whether the sport reflects contemporary athletic culture. Sports like ski ballet had artistic merit but couldn't sustain international interest, while military patrol became obsolete as the Olympics moved away from military symbolism.

How does the IOC decide which sports to keep or remove?

The IOC uses criteria including global participation levels across multiple continents, television ratings and broadcast potential, infrastructure and facility costs relative to the sport's popularity, gender equity and inclusivity, alignment with Olympic values, and athlete and federation enthusiasm. They also consider practical matters like whether venues can be repurposed after the Olympics and whether hosting cities can reasonably accommodate the sport. The process involves feedback from athletes, coaches, national federations, and broadcast partners. Sports like curling fought for decades to achieve full Olympic status before finally being included in 1998.

Could discontinued Winter Olympic sports ever return?

Yes, though it's rare. Skeleton was removed from the Olympics in 1992 but returned as a demonstration sport and eventually regained full Olympic status. However, most discontinued sports never return because they lack the global infrastructure needed for participation. Once a sport loses its Olympic platform, it becomes harder to attract athletes, coaches, and investment from different countries. Reviving a sport would require rebuilding international participation from scratch, which is expensive and difficult. The few sports that have successfully returned had dedicated communities that fought to bring them back and could demonstrate renewed international interest.

What makes a sport successful enough to stay in the Olympics?

Successful Olympic sports combine passionate grassroots participation in multiple countries, strong television audience appeal, reasonable infrastructure and hosting costs, and clear international competitive structure. Curling survived by developing authentic fan bases in Canada and Scotland, then finding television appeal once broadcasters figured out how to explain the strategy. Snowboarding succeeded because it had massive youth participation globally before joining the Olympics. Alpine skiing and figure skating remain permanent fixtures because they have centuries of tradition and strong participation across multiple continents. Sports that fail typically lack one or more of these elements.

Why was ski ballet so short-lived despite its artistic appeal?

Ski ballet looked innovative in the 1980s when it was added to the Olympics, combining skiing with choreographed artistry in ways that seemed fresh and creative. However, it faced several fundamental problems. First, it lacked the appeal of racing sports—viewers wanted excitement and clear winners, not artistic interpretation scored by judges. Second, it required specific venues and specialized training that didn't transfer to other skiing disciplines. Third, the broadcast presentation was difficult; viewers at home couldn't appreciate the artistry the way live audiences could. Finally, it appealed only to skiing enthusiasts with specific aesthetic tastes, not the broad audiences the Olympics needed. By the 1990s, the IOC decided freestyle skiing could satisfy the artistic impulses through moguls and slopestyle, which had clearer excitement and speed elements.

Could modern sports like skateboarding or breakdancing face removal in the future?

Possibly, though it would take significant shifts in global participation or popularity. Skateboarding was added to the Olympics because it has millions of practitioners worldwide and multigenerational participation. As long as that participation holds up and television ratings remain strong, skateboarding should survive. However, if youth interest shifted dramatically or if international participation declined, even skateboarding could be vulnerable. The Olympics are pragmatic about these decisions. Sports that seemed permanent in the past, like military patrol or ski ballet, got removed because conditions changed. No modern sport has permanent guaranteed status, though traditional sports like figure skating and skiing are more secure because they have deeper historical roots.

What was the strangest Winter Olympic sport that got discontinued?

Equestrian skijoring—where skiers were pulled across snow by galloping horses—might be the weirdest. It appeared exactly once as a demonstration event in 1928 in St. Moritz and was never repeated. The sport combined the unpredictability of horses with the coordination required for skiing, creating something that was more dangerous than exciting and served no practical purpose. Sled dog racing was also unusual, combining dogs with professional athletes across a 40-kilometer course, though it had more legitimate roots in actual transportation methods used in Alaska and Canada. These sports represented an era when the Olympics were more experimental and willing to include quirky regional activities.

Why did military patrol disappear while biathlon survived?

Military patrol combined rifle shooting with cross-country skiing while competitors wore full military uniforms, which linked the sport directly to military institutions. Biathlon, which evolved from military patrol, stripped away the military uniform requirement and streamlined the format into pure athletic competition. Biathlon succeeded because it was less tied to military nationalism and more focused on athletic excellence. It also became more accessible—you didn't need military background to compete—which helped build global participation. As the Olympics moved away from military symbolism in the post-war era, sports like biathlon that kept the athletic core but removed the military elements survived, while sports like military patrol faded away.

Key Takeaways

- Over 100 years, the Winter Olympics have discontinued multiple sports including ski ballet, bandy, equestrian skijoring, military patrol, and sled dog racing due to lack of global participation or infrastructure limitations

- Ski ballet combined choreographed movements with skiing from 1988-1992 but couldn't sustain viewer interest compared to racing-based sports with clearer winners

- Equestrian skijoring, where skiers were pulled by horses, appeared once in 1928 and never returned because it was impractical and dangerous

- Military patrol evolved into modern biathlon when the Olympics moved away from military symbolism, showing how sports can survive by adapting their core elements

- Sports that survive like curling and snowboarding build global participation across multiple countries while sports that disappear typically lack the international infrastructure or broadcast appeal needed for sustainability

- The 2026 Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics will feature 109 events in 15 sports, continuing the Olympics' tradition of evolving with what the world cares about at any given moment

Related Articles

- Logitech G325 Lightspeed Gaming Headset Review [2025]

- Malwarebytes and ChatGPT: The AI Scam Detection Game-Changer [2025]

- X's Paris HQ Raided by French Prosecutors: What It Means [2025]

- Microsoft Teams People Skills Profile: How to Showcase Your Work Talents [2025]

- Notepad++ Supply Chain Attack: Chinese State Hackers Explained [2025]

- Game UK Stores Closing: The Death of Physical Game Retail [2025]

![Winter Olympics Discontinued Sports: The Events You Won't See in 2026 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/winter-olympics-discontinued-sports-the-events-you-won-t-see/image-1-1770120385198.jpg)