Open AI's Contractor Training Data Strategy: A Legal Minefield

Something troubling is happening behind the scenes at AI companies, and frankly, it should concern you whether you're a contractor, an employee, or someone who uses these systems. Open AI and partner companies like Handshake AI are asking third-party contractors to upload actual work they've done in previous jobs. Not summaries. Not anonymized examples. The real files. Word documents, PDFs, Power Point presentations, Excel sheets, images, entire code repositories.

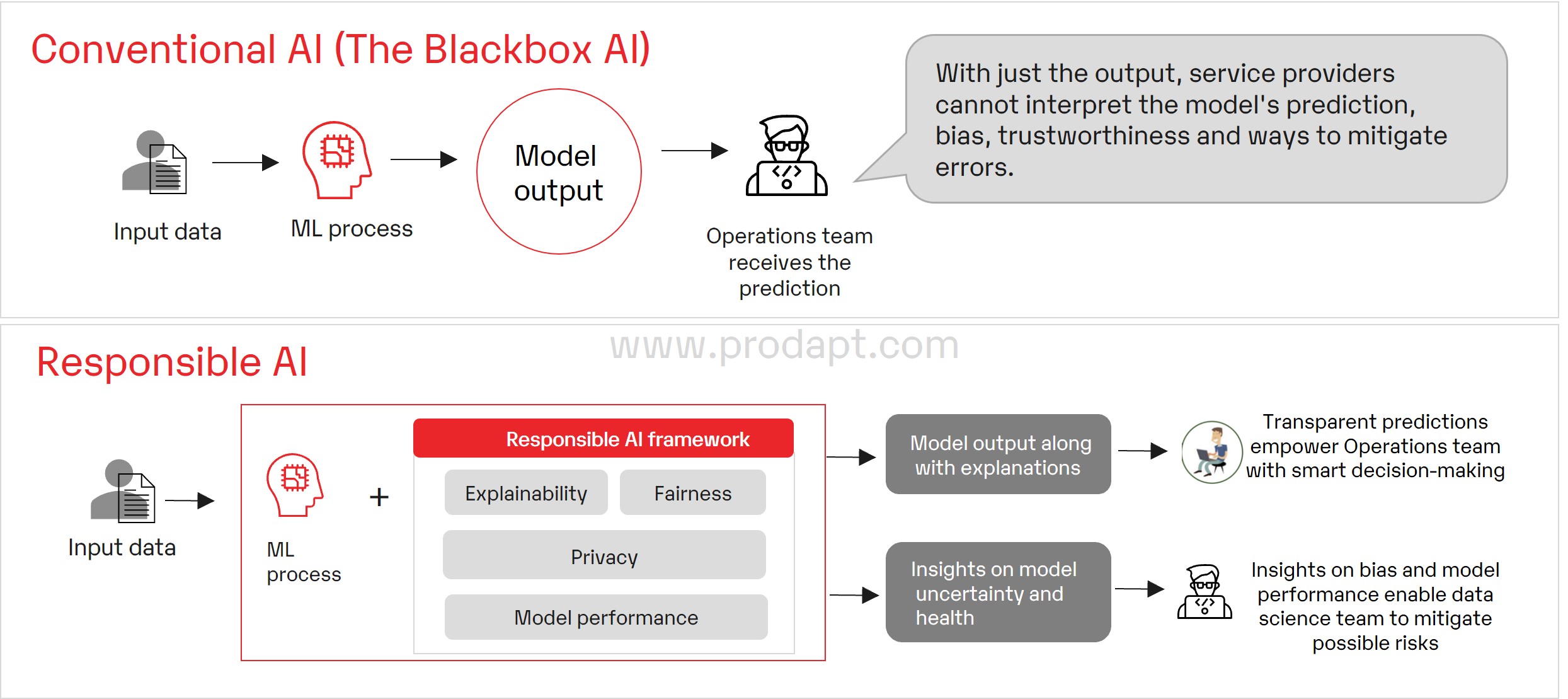

The stated goal sounds reasonable on the surface: gather high-quality training data so AI models can better understand how humans actually work. But here's where it gets messy. According to recent reporting, Open AI instructs contractors to scrub proprietary and personally identifiable information before uploading using a Chat GPT tool called "Superstar Scrubbing." The problem is that this approach trusts individual contractors, who often lack formal legal training, to make sophisticated judgments about what counts as confidential.

This isn't a small oversight. An intellectual property lawyer told reporters that any AI lab taking this approach is "putting itself at great risk." Why? Because the legal liability chain is incredibly complex. When you upload work from a past employer, you're potentially uploading their intellectual property without their permission. You might also be violating non-disclosure agreements you signed. And if something goes wrong, Open AI could face lawsuits not just from disgruntled contractors, but from the companies whose work inadvertently made it into training datasets.

The bigger picture matters here. AI companies are in an arms race for quality training data. The models that get trained on better, more diverse, more realistic data tend to perform better at actual human tasks. That's why Open AI and others are willing to pay contractors to gather this data. But the approach reveals something important about how AI development happens: it's fundamentally dependent on human labor and human judgment, and the economic incentives are misaligned in ways that could create real problems.

I'll break down what's actually happening, why it matters legally and ethically, what the risks are for everyone involved, and what might happen next.

TL; DR

- Open AI is asking contractors to upload actual work from past and present jobs, including real files like PDFs, spreadsheets, and code repositories, not just descriptions

- Legal experts warn this creates massive IP liability because contractors often lack the expertise to identify what counts as confidential material before uploading

- This violates NDAs and IP agreements that contractors signed with their previous employers, potentially exposing Open AI to lawsuits

- The trust model is fundamentally broken because contractors are financially incentivized to upload more data, creating pressure to include borderline material

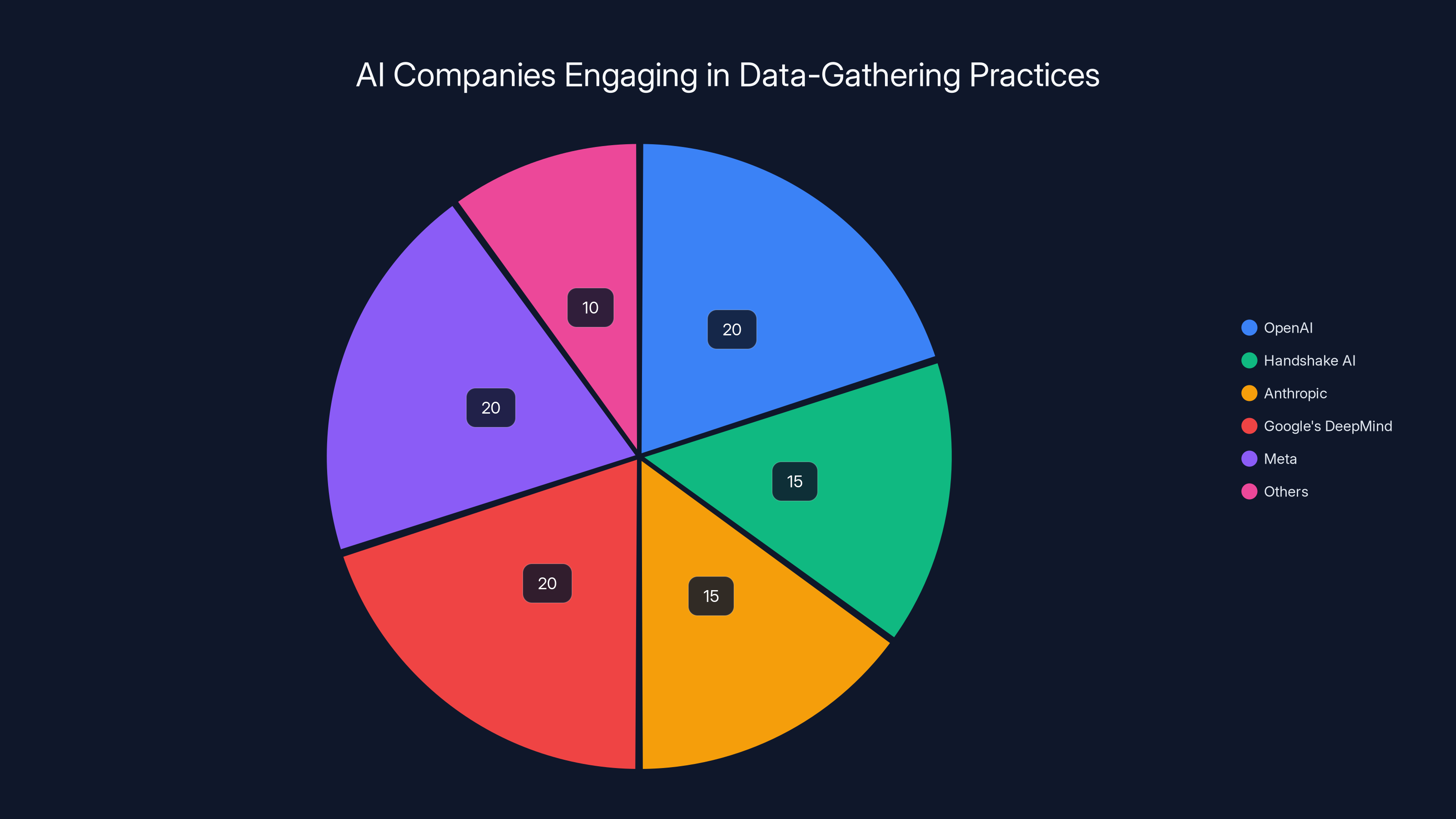

- Other AI companies are doing the same thing, suggesting this is becoming standard practice in the industry despite the legal risks

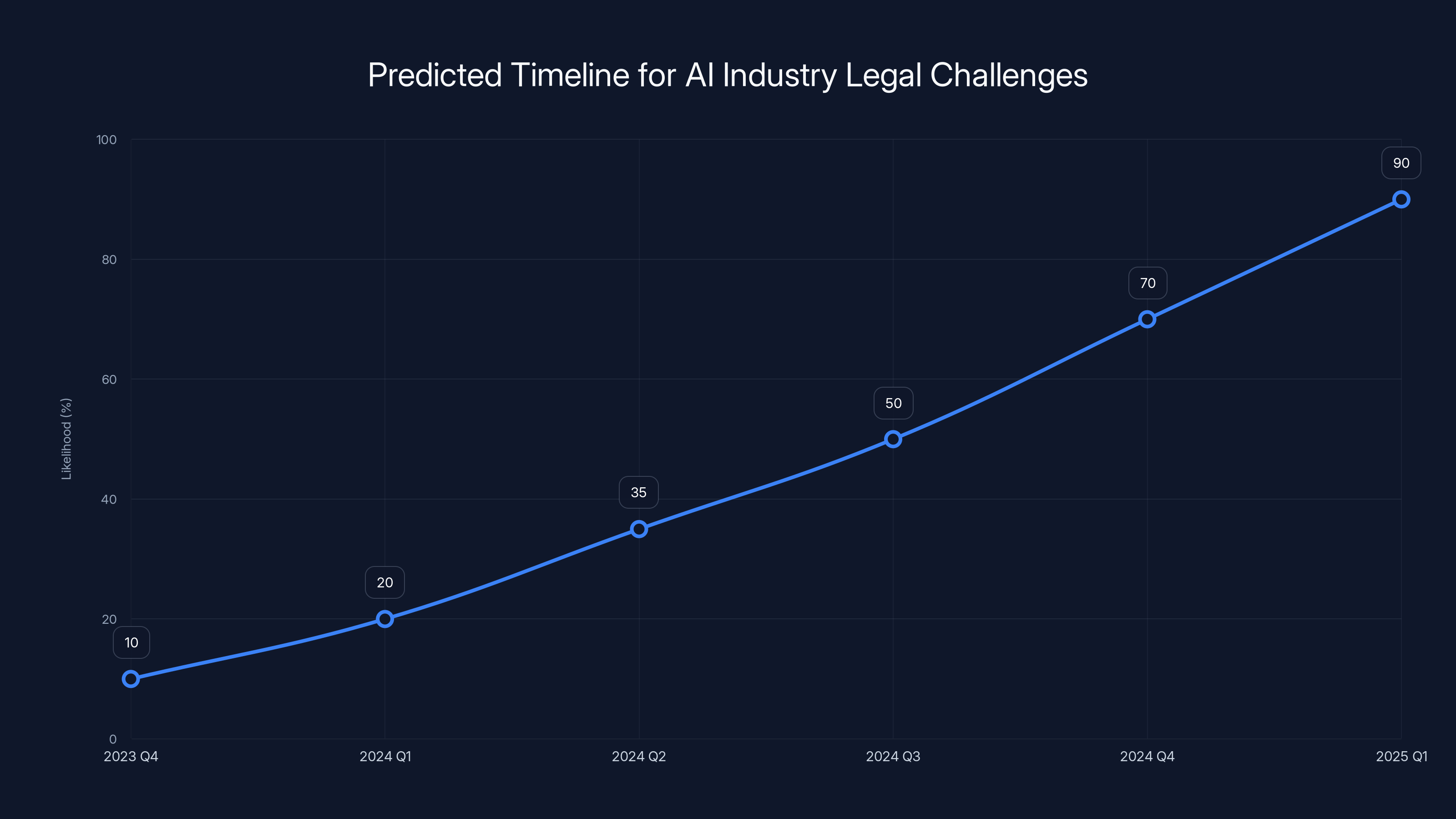

Estimated data suggests that within 18-24 months, the likelihood of significant legal or regulatory action in the AI industry could reach 90%. This projection emphasizes the growing importance of legal safeguards.

Understanding the Core Problem: Trust Without Expertise

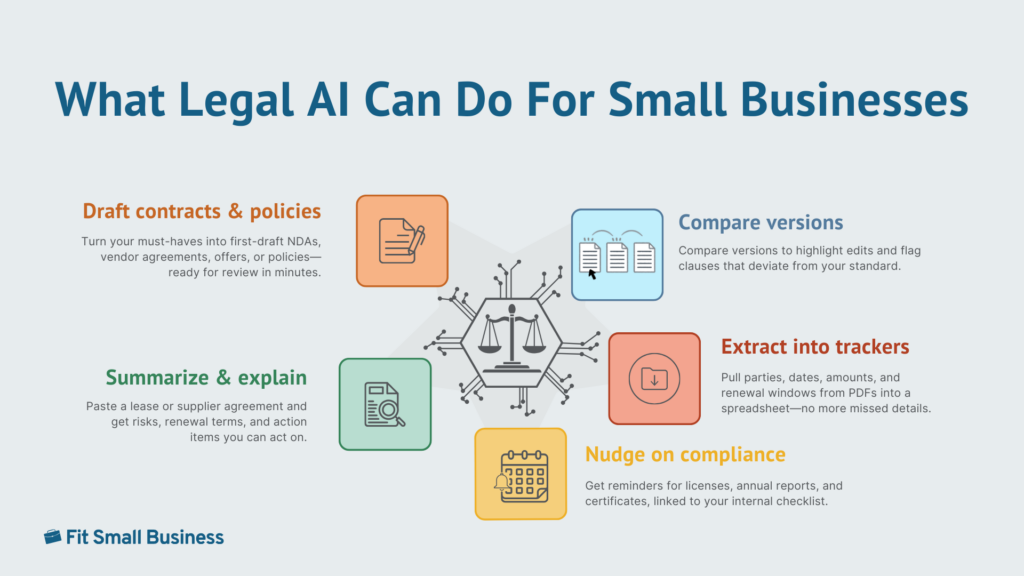

Let's talk about why this contractor approach exists in the first place. AI models trained on synthetic or generic data perform worse at real-world tasks. A language model trained only on publicly available Wikipedia articles and cleaned datasets will struggle when you ask it to help with actual business problems because those examples don't match the messy reality of how work actually gets done.

So companies started hiring contractors to generate training data. Some of this is creating new synthetic examples from scratch. But increasingly, companies realized that real examples of actual work produce better training signals. If you want an AI system that can actually help lawyers draft contracts, show it real contracts. If you want it to help engineers write code, show it real code. If you want it to help marketers create presentations, show it real presentations.

The problem is obvious once you think about it: most real work is proprietary. It belongs to someone else. It's covered by confidentiality agreements. It contains sensitive information about customers, strategies, finances, or technical details that companies specifically don't want publicized.

Open AI's solution was clever in a way, though also legally risky. They told contractors: "Upload real work, but remove the confidential stuff first." They even provided a tool to help. Chat GPT's "Superstar Scrubbing" feature is designed to help contractors identify and redact sensitive information before uploading.

But here's the issue that keeps lawyers awake at night: contractors are not qualified to make these judgments. A person who worked in marketing for six months might not understand what counts as a "trade secret" under their former employer's confidentiality agreement. Someone who coded for a startup might not realize that the architecture decisions they made contain valuable proprietary information. A consultant might not understand which client details are fair game and which violate client confidentiality agreements.

Worse, the financial incentive goes the wrong direction. Contractors are paid per-submission or based on data volume. The more they upload, the more they earn. This creates pressure to include borderline material. Is this PDF a template they created on their own time, or was it created on company time? They're probably not 100% sure. Under financial pressure, guess which way the decision tends to go.

And here's the thing that's really important: the contractor might not even know what they're violating. They might have signed a non-disclosure agreement two years ago at a job they don't work at anymore and genuinely forgot what it said. Or they might think "this is my work, so it's mine to share" without understanding that employment contracts typically assign IP to the employer.

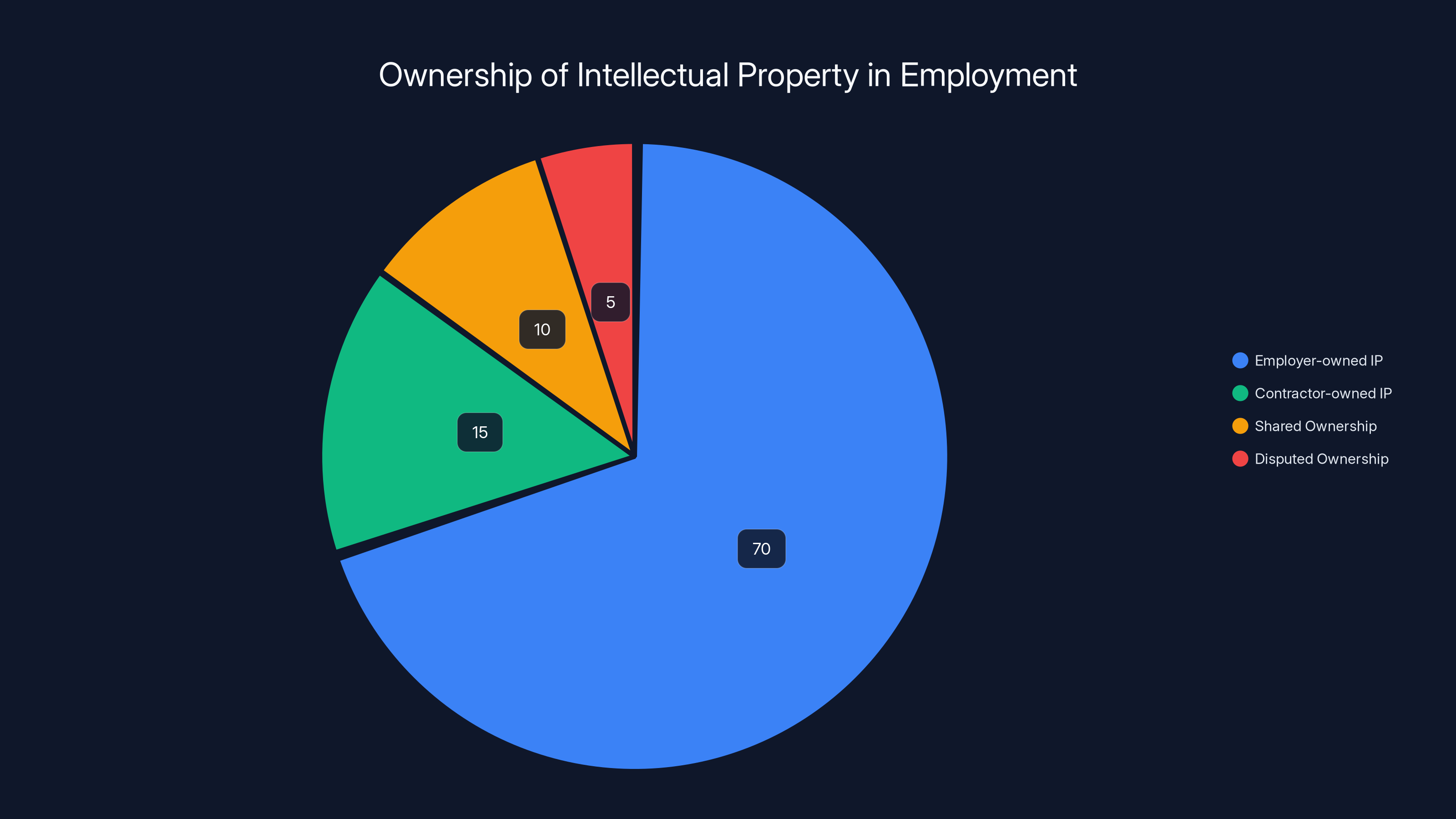

The Intellectual Property Nightmare: Who Actually Owns the Work

This is where the legal analysis gets really concerning. In most employment relationships, the employer owns the intellectual property created by the employee. There are exceptions (independent contractors who create custom works might retain some rights), but as a general rule, if you created something while employed, the company owns it.

When a contractor uploads that work to Open AI without explicit permission from their former employer, they're uploading IP that doesn't belong to them. That's not just a technical violation. That's potential infringement. The former employer could theoretically sue both the contractor and Open AI for copyright infringement and theft of trade secrets.

Now, will they? That depends on a bunch of factors. If the work ends up in a training dataset for a model that becomes valuable, the incentive to sue increases significantly. If the work is identifiable and clearly came from your company, the incentive goes up again. If you're a large corporation with IP lawyers already on staff, you might notice and take action.

But here's what really matters: Open AI can't claim innocence. Once they know—or should know—that contractors are uploading potentially non-owned IP, they have a responsibility to verify ownership or get permission. Relying on contractors to self-regulate this process is legally insufficient. Courts might view this as willful infringement if Open AI was aware they were creating systems that incentivized contractors to upload material that likely violated IP assignments.

There's also the trade secret angle. If the uploaded work contains process information, technical approaches, or strategic decisions that the former employer treats as confidential, Open AI is potentially acquiring and using stolen trade secrets. That opens them up to liability under the Economic Espionage Act and state trade secret laws.

The thing that's wild about this situation is that it's not even that hard to do better. Open AI could require contractors to:

- Get explicit written permission from their former employer before uploading

- Sign affidavits stating they own the material and have the right to share it

- Limit uploads to work created more than X years ago when retention agreements have expired

- Create a verification process where representatives from contractor's past employers can challenge uploads

- Use legal review before integrating contractor data into training sets

They're not doing these things, apparently, which suggests they're comfortable with the risk or haven't fully thought through the implications.

The most severe challenge in using real work for AI training is the lack of expertise among contractors, followed by data sensitivity and legal risks. Estimated data.

Non-Disclosure Agreements: The Invisible Legal Bombs

Most people who've worked in tech, consulting, finance, or professional services have signed an NDA at some point. Usually while onboarding, when you're not really paying attention, when the company is telling you "everyone signs this, it's totally standard."

These agreements typically say you won't disclose confidential information about the company's business, client relationships, technical systems, financial information, or strategic plans. The duration varies. Some NDAs expire after you leave the company. Some last for five years. Some are perpetual. Most NDAs define what counts as confidential very broadly.

Here's the problem with uploading past work to Open AI while under an NDA: you might be in direct violation of that agreement. When you upload a presentation from a past job, you're technically disclosing information the company considered confidential. When you upload a code repository, you're potentially revealing technical approaches and architecture decisions the company wanted to keep secret.

The contractor's defense ("I removed all the identifying information") doesn't actually work under most NDA frameworks. The information is still confidential whether or not you've removed names. In fact, some NDAs explicitly state that the confidential nature of information doesn't change just because you've removed identifying details.

And here's where Open AI's liability increases: they're inducing contractors to breach their NDAs. By offering payment for uploaded work and providing a "scrubbing" tool rather than a permission verification system, they're effectively incentivizing and facilitating NDA breaches. That could expose them to civil claims from the companies whose NDAs are being violated.

Employers are starting to pay attention to this stuff. I'd expect to see cease-and-desist letters from large companies to Open AI, and potentially lawsuits, within the next 18-24 months. Once a major company discovers that their proprietary information ended up in an Open AI training dataset because a contractor uploaded it, things will move fast.

The interesting legal question is whether Open AI can claim they're blameless because contractors uploaded the material without permission. Courts don't usually accept "I didn't steal it, my employees/contractors did" as a valid defense when the company created the system that incentivized the theft.

The "Scrubbing Tool" Problem: AI Can't Actually Do This Job

Open AI's response to the IP concerns is the Chat GPT "Superstar Scrubbing" tool. The idea is that contractors can paste confidential material into this tool, it will identify and redact sensitive information, and then they can safely upload the scrubbed version.

On the surface, this sounds responsible. In practice, it's probably not sufficient. Here's why.

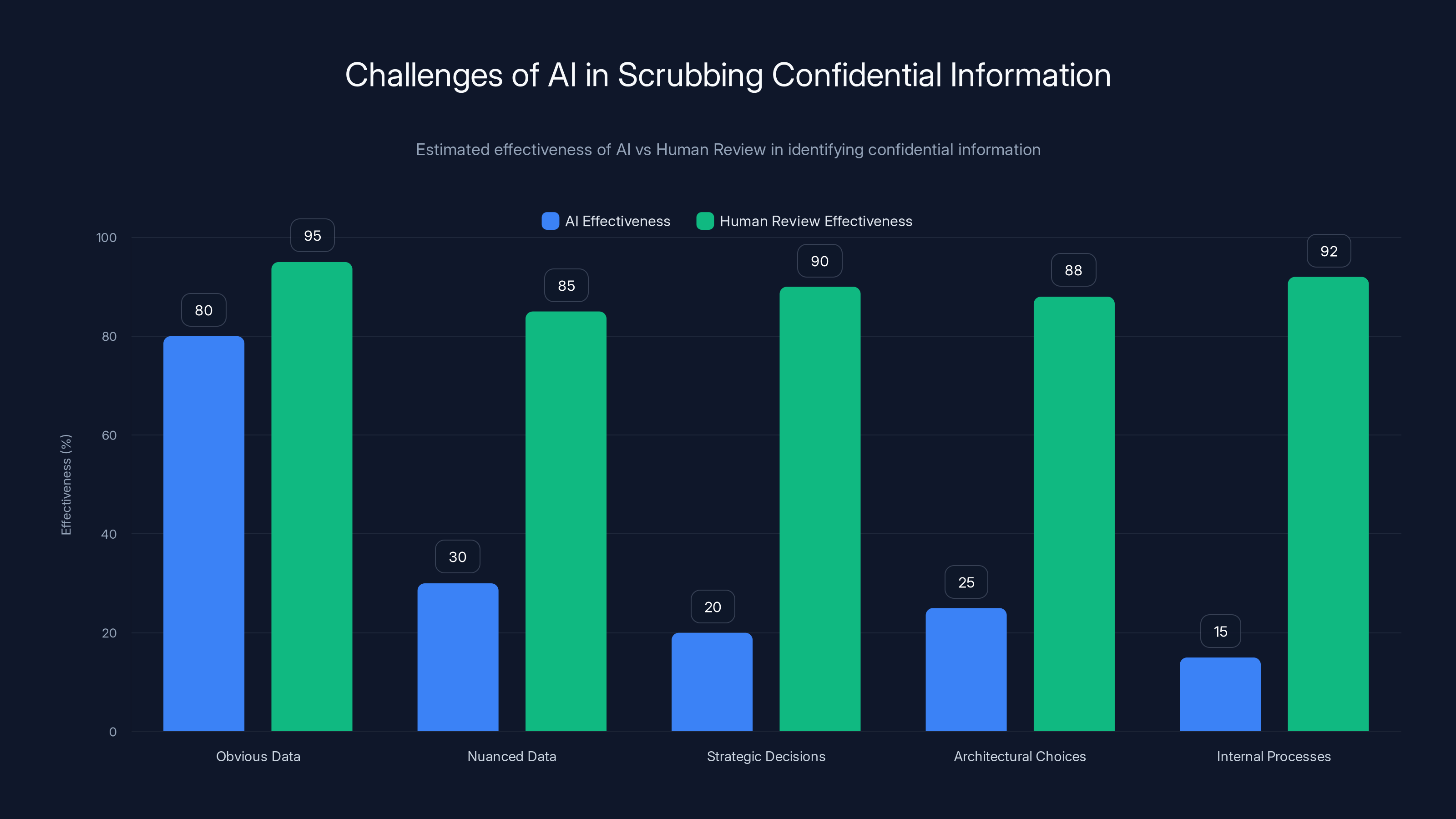

First, AI models are actually bad at understanding context and what genuinely needs to be confidential. They can catch obvious stuff like "Client name: Acme Corp" or "Our revenue is $500M." But they often miss nuanced confidential information. Strategic decisions. Architectural choices. Internal process flows. Competitive positioning. All of this could be considered trade secrets, but it's not the kind of thing an AI will automatically flag for removal.

Second, the tool is just doing what Chat GPT is asked to do. If a contractor provides incomplete or inaccurate instructions, the tool won't fix it. Contractors have to tell the tool what to remove. Many contractors probably won't even know what should be removed because they don't understand IP law.

Third, there's a liability question about whether this tool even helps Open AI's legal position. Providing a tool that says "use this to remove confidential information" doesn't protect you if the tool doesn't actually work. In fact, it might make things worse. It suggests Open AI thought about the problem but created an inadequate solution. That could actually increase liability because a court might view it as negligent risk management.

A more responsible approach would be a human legal review process. Contractors upload material. Actual lawyers review it. Lawyers decide whether it can be used. This would be expensive, which is probably why Open AI isn't doing it. But it's also the only approach that actually protects them legally.

The tool also creates a false sense of security. Contractors use it, see that stuff got redacted, assume the remaining material is safe to share, and upload it. But the tool missed things. Now the contractor has unknowingly shared confidential material, Open AI has it in their dataset, and the liability chain is even more complex.

I think what's happening here is that Open AI faced a choice: invest in proper legal review of contractor uploads (expensive, slow) or create a tool that sounds responsible while shifting liability and responsibility onto contractors (cheaper, faster). They chose the second option. It's understandable from a business perspective. It's terrible from a legal perspective.

The Incentive Structure: Why This Will Keep Happening

Let's zoom out and think about why companies keep taking these risks. From Open AI's perspective, the math probably makes sense.

They need high-quality training data. Real data is better than synthetic data. Contractors will provide real data if you pay them. The cost of contractor payments is less than the cost of building internal teams to create synthetic data or licensing data from other sources. Some percentage of contractors will inadvertently upload material they don't own, but most will probably be unidentifiable or immaterial. If a lawsuit does happen, Open AI is a wealthy company and can litigate or settle. The expected legal cost is probably lower than the benefit of having better training data.

This is classic economic thinking: if the expected cost of violation is lower than the benefit of violation, rational actors violate. Open AI is being rational. They're accepting a known legal risk because the upside is significant.

What changes this calculation? A few things:

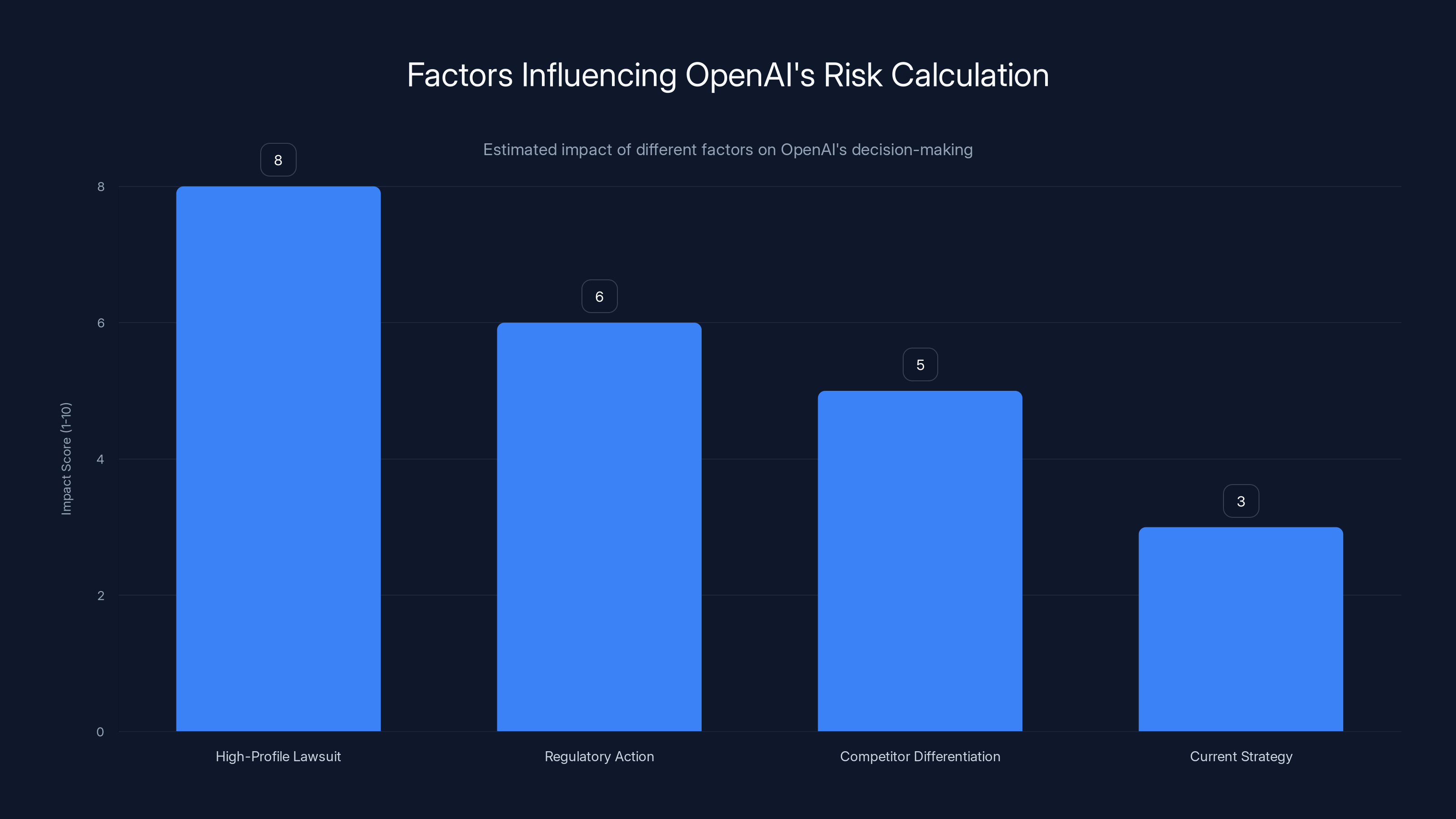

First, a high-profile lawsuit that actually wins against Open AI. If a major company sues Open AI for acquiring trade secrets through contractors and a court rules in their favor with substantial damages, the calculation changes. Open AI's legal costs go up. Their insurance premiums go up. Other companies file copycat lawsuits. Suddenly the expected cost exceeds the expected benefit.

Second, regulatory action. If Congress or a state legislature passes a law specifically prohibiting this practice, the calculation changes overnight. Legal compliance becomes mandatory, not optional. This seems less likely in the near term, but it's possible.

Third, competitor differentiation. If one AI company says "we get permission from original employers before using contractor data" and makes a big deal about it, that company gets marketing advantage. It positions them as more ethical and less risky. Other companies might follow to match. This seems plausible in the next few years.

Fourth, scale issues. As AI companies get bigger and their training datasets get larger, the chances of a lawsuit increase. If you've incorporated data from 100,000 contractors, it's much more likely that one came from a company willing to sue than if you've incorporated data from 1,000 contractors.

Right now, we're probably still early enough in this process that many companies don't even know their data is in AI training sets. That changes when they discover it or when journalists or researchers document it. Then the lawsuits start.

The crazy part is that this is entirely avoidable. Open AI could build the right incentives:

- Pay contractors more for work they can prove they own or have permission to share

- Create a system where prior employers can verify or challenge uploads

- Do manual legal review of uploads before using them

- Get explicit indemnification from contractors stating they own the material

They're not doing these things because they're expensive and slow. So the current system persists until the legal risk becomes unavoidable.

Estimated data shows that in most employment scenarios, the employer owns the intellectual property (70%), with contractors retaining ownership in fewer cases (15%). Shared and disputed ownership are less common.

Other AI Companies Doing the Same Thing: It's Industry Practice

Here's something important to understand: Open AI isn't doing this alone. Handshake AI, which created the data-gathering system Open AI is using, is working with other AI companies on similar programs. This is becoming standard practice in the industry.

When an approach becomes standard practice across an industry, it means several things. First, the legal risk is somehow distributed. If everyone is doing it, no single company is the obvious target for a lawsuit. Second, there's probably industry coordination happening behind the scenes, possibly through lawyers or industry groups, to develop a common understanding of what's acceptable. Third, there's regulatory capture risk, where the industry works to prevent any legal framework from emerging that would prohibit the practice.

But it also means that if there is a legal reckoning, it could affect the entire industry simultaneously. Imagine a court ruling that AI companies must get explicit permission before using contractor-uploaded data. That could reshape how AI training data is collected across the board.

The companies doing this include some of the biggest names in AI. Anthropic has contractor programs. Google's Deep Mind has similar initiatives. Meta has internal teams generating training data, though they're also working with contractors on specific projects. Even smaller AI companies trying to build competitive models are adopting similar approaches because it's the fastest way to get the data they need.

What's interesting is that most of these companies are not publicly discussing the IP and NDA risks. The media coverage has been limited. Most tech workers probably don't even know this is happening. That will change once the first lawsuit settles or a major story breaks. Then you'll see companies scrambling to improve their contractor vetting and IP verification processes.

I'd expect to see this as a major issue in tech policy discussions within the next 2-3 years. It'll probably make it into congressional hearings about AI regulation. Companies will probably have to start changing their practices preemptively to avoid bad optics.

Contractor Liability: The Forgotten Victims

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: the contractors themselves are in a legally vulnerable position.

When you upload past work to Open AI without permission from your former employer, you're potentially liable for breach of contract (NDA violation), copyright infringement, theft of trade secrets, and potentially other violations depending on the work involved. Your former employer could sue you directly. Open AI might not even be the primary target.

This is particularly unfair because contractors are typically the least sophisticated party in this transaction. They're taking a gig job, making money per submission, and probably not thinking deeply about IP law. Meanwhile, Open AI is a multi-billion-dollar company with lawyers on staff who definitely should be thinking about this stuff.

But "unfair" and "actually liable" are different things. If you upload work you don't own and your former employer sues, you could face real damages. Your defense ("I didn't know it was illegal" or "Open AI told me it was okay") probably won't hold up. You signed an NDA. You're responsible for understanding it.

There's also a practical issue for contractors: if a lawsuit happens, you'll probably need a lawyer. That's expensive. You might not have the resources to defend yourself. You could end up settling just to make it go away. Open AI, on the other hand, has unlimited resources for legal defense.

I think there's a real case for Open AI to have more responsibility here. They're creating the system and incentivizing the uploads. Contractors are just trying to make money. If anyone should be verifying IP ownership, it should be the company with billions in revenue and dedicated legal teams, not gig workers.

But that's not how liability typically works. Contractors should probably be checking their old contracts before uploading. I'd recommend that to anyone considering this.

The International Dimension: Different Rules, More Risk

Here's something that makes this even more complicated: IP law varies significantly by country. The U. S. has the framework I've been describing. But if Open AI's contractor program involves people from other countries, the legal rules might be different.

In the European Union, for example, trade secret protection is even stronger under the Trade Secrets Directive. There's also the GDPR, which might make collecting and using contractor data more restricted. A contractor in Germany uploading past work might be violating EU law in ways that U. S. contractors aren't.

In jurisdictions like Canada or Australia, employment law and IP assignment rules are different too. The assumption that "employment contracts typically assign IP to the employer" doesn't hold everywhere. Some places have stronger protections for employees and contractors.

This means Open AI's risk is actually higher than it might appear. They could face legal action not just in the U. S., but in multiple jurisdictions simultaneously. Different countries' IP laws could all be violated by the same dataset. Different regulatory frameworks could apply.

I'd expect Open AI's legal team is aware of this and probably has some framework for managing international risk. But it definitely adds complexity and cost.

There's also a diplomatic angle. If a major corporation in Country A discovers that their IP ended up in an AI training dataset through Open AI's contractor program, they might escalate this to their government. Trade secret theft becomes a trade policy issue. That's the kind of thing that governments actually care about.

Estimated data shows AI is effective at identifying obvious confidential information but struggles with nuanced data, whereas human review is consistently more effective across all categories.

What Might Change This: Litigation, Regulation, and Competition

So what actually happens next? There are a few scenarios.

Scenario One: The First Big Lawsuit. A major corporation discovers their confidential work in an AI training dataset. They sue Open AI for copyright infringement, trade secret theft, and unfair competition. The case goes to trial or settles for a large amount. This becomes news. Other companies realize their data might be at risk and start investigating. The legal liability calculus changes for all AI companies.

Scenario Two: Regulatory Action. Congress passes legislation requiring explicit permission before using contractor-uploaded data in AI training. Or the FTC brings enforcement action against Open AI for unfair practices. These legal requirements reshape how data collection works across the industry.

Scenario Three: Competitive Differentiation. Another AI company (maybe Anthropic or Google) announces they've built a contractor program with explicit legal safeguards. They market this as an ethical, low-risk alternative to Open AI's approach. Other companies follow. Open AI either changes their practices or faces public criticism for being riskier than competitors.

Scenario Four: Scaling Issues. As the contractor program grows and more data is integrated into training sets, the chances of detection or litigation increase naturally. Eventually a lawsuit becomes inevitable just through statistics.

My prediction: within 18-24 months, we see at least one significant lawsuit or regulatory action related to this issue. That forces the industry to build better legal safeguards. The contractor data model might persist, but it gets much more legalized and structured. Companies start requiring explicit permission, doing background verification, and potentially using blockchain-based ownership verification.

It's also possible that this becomes a permanent part of AI industry criticism. Environmental groups criticize big compute. Labor advocates criticize low contractor wages. IP advocates criticize data collection practices. Open AI and other AI companies learn to live with ongoing legal risk and just budget for it as a cost of doing business.

Best Practices for Companies: How to Do This Right

If you're working at an AI company and thinking about contractor data programs, here's how to actually build something defensible:

Step 1: Get Explicit Permission. Require contractors to provide written proof that they own the material or have permission from the original owner to share it. This could be a contract assignment, permission letter from the original employer, or a declaration under penalty of perjury that they own it.

Step 2: Verify IP Ownership. Actually look at what contractors are uploading. Have a human lawyer review a sample of uploads to make sure they're actually owned by the contractor and not obviously taken from their employer.

Step 3: Create an Indemnification Framework. Contractors should sign agreements stating they own the material, have the right to share it, and will indemnify your company if they're wrong. This doesn't eliminate risk, but it does shift some of it to the party in the best position to know whether they own what they're uploading.

Step 4: Exclude High-Risk Material. Don't accept uploads from certain industries or contexts where IP is particularly likely to be owned by employers or clients. Code from employment probably isn't safe. Client work definitely isn't safe. Personal projects are probably okay.

Step 5: Use Contractual Dates. Require that material be more than a certain age (maybe 5-7 years) before accepting it. This reduces the chance that the material is still covered by NDAs. It also makes it more likely that the contractor's memory of what's confidential has faded enough that they've already violated any confidentiality obligations elsewhere.

Step 6: Implement Legal Review Before Integration. Before contractor data gets folded into your training datasets, have it reviewed by lawyers who specialize in IP. Yes, this is slower and more expensive. Yes, this is how you actually do things legally.

Step 7: Build Employer Verification Systems. Create a system where contractors' former employers can verify whether the uploaded material belongs to them. This could be as simple as a search portal where companies can look for their trademarked products or recognizable materials.

Step 8: Maintain Audit Trails. Keep detailed records of where all data came from, who uploaded it, what verification was done, and what the contractor's representations were. If a lawsuit happens, these records protect you by showing due diligence.

None of this is particularly complicated. It's mostly just being careful and building legal infrastructure around data collection. The reason companies aren't doing it is pure cost-benefit analysis. They think the risk is worth the cost savings.

The Broader AI Training Data Problem

The contractor IP issue is actually just one facet of a larger problem with AI training data. The entire industry is built on a foundation of data collection practices that are legally and ethically questionable in many cases.

Large language models have been trained on massive datasets scraped from the internet. Researchers haven't typically gotten permission from website owners, image creators, or authors whose work was scraped. There are copyright lawsuits happening right now about this. Artists are suing for unauthorized use of their work. News organizations are suing because their content was included in training data.

The contractor angle is actually more defensible than the internet scraping angle, because at least contractors are consensually choosing to upload. They're being paid. They presumably read the terms of service. But it's still legally risky if proper IP verification isn't done.

I think what we're going to see is convergence toward more restrictive and legalized data practices. AI companies will start licensing datasets from large content providers. They'll start building partnerships with news organizations, academic institutions, and other data sources. They'll start being more careful about what they include.

This doesn't solve the problem entirely, but it shifts the risk and liability to the companies that are best positioned to handle it. It's also more expensive, which is why it hasn't happened yet. But as legal risk increases, the cost-benefit calculation changes.

High-profile lawsuits could significantly alter OpenAI's risk-benefit analysis, while regulatory action and competitor differentiation also pose moderate impacts. Estimated data.

What Contractors Should Actually Do

If you're considering uploading past work to Open AI or another AI company's contractor program, here's my honest assessment of what you should do:

First, read your old employment agreements. Look for:

- Work-made-for-hire clauses that assign IP to the employer

- Confidentiality or non-disclosure agreements

- Non-compete clauses that might restrict how you use past work

- Specific prohibitions on uploading or sharing work

Second, contact your former employer if necessary. If you're genuinely unsure whether you own the work, ask. It's awkward, but it's better than being sued.

Third, consider whether the income justifies the risk. If you're making

Fourth, don't rely on the company's scrubbing tools to make things safe. Those tools are probably not sufficient. You're the one with legal responsibility here. Own it.

Fifth, keep records. If you do upload material, keep documentation of what you uploaded, when you created it, and evidence that you own it or have permission to share it. This helps if questions come up later.

Realistically, a lot of contractors probably won't do all this due diligence. They'll upload material, make some money, and hope nothing goes wrong. That's probably fine for most people. But for anyone with material from previous jobs, especially at larger companies, I'd be cautious.

The Role of Handshake AI: The Middleman Problem

It's worth understanding the relationship between Open AI and Handshake AI, the company that actually built the contractor data collection system.

Handshake AI isn't just working with Open AI. They're positioning themselves as a general contractor data platform for multiple AI companies. They're the middleman, the infrastructure layer that connects AI companies with contractors willing to upload work.

This creates an interesting liability question. If something goes wrong with data that was collected through Handshake AI's platform, who's responsible? Open AI for using the data? Handshake AI for collecting it? The contractors for uploading it? Probably all three, but in different ways.

From Handshake AI's perspective, the liability question is interesting too. They have a financial incentive to collect as much data as possible because they probably take a cut of the payments. The more data collected, the more money they make. But they don't bear the IP liability risk. If lawsuits happen, their liability is probably less than Open AI's or the contractor's.

This kind of liability distribution across middlemen is actually pretty common in business. It creates misaligned incentives. The party collecting data has an incentive to collect a lot of it, but doesn't bear the full risk of that data being problematic. The party using the data bears the risk but might not control the collection process.

I'd expect that as IP disputes emerge, we'll see finger-pointing between Open AI, Handshake AI, and contractors about who bears responsibility for problems. This is actually one reason why explicit legal frameworks matter. They clarify who is responsible when things go wrong.

How This Affects AI Model Performance and Capabilities

Let's think about why this data actually matters for AI capabilities. Better training data genuinely does lead to better model performance. Real examples of work performed by real humans on real tasks create training signals that synthetic or generic data doesn't provide.

If Open AI trains GPT-5 or GPT-6 using this contractor data, the model will probably perform better at real-world tasks than competitors' models trained on other datasets. It'll better understand how business presentations are structured. It'll know more about how actual codebases are organized. It'll understand the messiness of real work in a way that models trained purely on academic or synthetic data won't.

This is why the IP risk is worth taking from Open AI's perspective. The model improvement justifies the legal risk. But it also means that the competitive advantage is partly built on IP that might not belong to Open AI.

This raises an interesting philosophical question: should competitive advantage be allowed if it's built on potentially stolen IP? Most people would say no. But courts have to decide what happened, and that takes years.

There's also a reputational angle. If it becomes widely known that Open AI's models were trained in part on data improperly obtained from workers and their former employers, that affects how people perceive the company. It becomes a negative factor in enterprise deals. Customers start asking "is this model trained on our IP?" Employees at Open AI might feel uncomfortable about practices they didn't know were happening.

All of this suggests that even if Open AI thinks the legal risk is acceptable, the reputational and business risk might not be. Companies often care more about being seen as ethical than about saving a few million dollars on data collection costs.

Estimated data shows that major AI companies like OpenAI, DeepMind, and Meta are leading in adopting data-gathering practices, making up 75% of the industry. Estimated data.

Timeline: How This Likely Unfolds

Here's my prediction for how this issue develops over the next few years:

2025 (Current): Investigative journalists continue reporting on contractor data practices. More AI companies get revealed to be using similar approaches. No major lawsuits have happened yet, but legal professionals start warning about the risks.

Late 2025 - Early 2026: First significant lawsuit filed by a corporation claiming their IP was improperly used in AI training. Case might take a while to develop, but it's filed.

2026: Industry publications start running stories about IP risks in AI training. HR departments at large companies start adding language to employee contracts about AI training data. Some companies proactively notify employees that their past work might have been used.

2026-2027: Regulatory agencies (FTC, state attorneys general) start investigating whether this practice violates existing laws or constitutes unfair business practices. Congressional hearings happen.

2027-2028: Settlement or court ruling on initial lawsuit. This either forces AI companies to change practices or legitimizes them (depending on the outcome). Probably leads to new industry standard practices with more legal safeguards.

2028+: AI companies modify contractor data collection programs to require explicit permission and IP verification. The practice continues but becomes more legalized.

This is obviously a prediction and things could move faster or slower. But the general trajectory seems likely: issue emerges, legal risk materializes, industry adapts.

What Should Happen: The Ideal Framework

If we're designing a system from scratch for how AI companies should collect contractor data, what would it look like?

Explicit Ownership Verification: Before accepting any data, require contractors to prove they own it. This could be through:

- Written permission from the original owner

- Proof that they created it on their own time with their own resources

- Declaration under penalty of perjury with indemnification

- Time-based rules (data older than X years is presumed to be fair game)

Transparent Data Sourcing: AI companies should publicly disclose where their training data came from at a high level. "30% from licensed datasets, 40% from public internet scraping with permission, 20% from contractor-uploaded work, 10% synthetic." This creates accountability.

Contractor Support and Education: Contractors uploading data should get legal education about what they're doing and what risks they face. Simple terms of service aren't enough when people are potentially violating contracts they forgot about.

Employer Verification Systems: Build infrastructure that lets original employers check whether their data ended up in training datasets and challenge uploads they don't approve of.

Legal Standards: Congress could pass legislation establishing clear standards for what is and isn't acceptable in AI training data collection. This would reduce legal uncertainty.

Licensing and Compensation: Instead of sneaking data into training sets, AI companies could license data from content creators and pay them. This is more expensive but actually legal and ethical.

Audit and Accountability: Regular independent audits of AI training datasets to verify that only properly sourced data was used. Companies that fail audits face penalties.

This framework would be more expensive and slower. It would reduce the amount of data available for training. It would probably slow down AI development. But it would be legal, ethical, and wouldn't expose companies to massive liability.

The question is whether the industry will move toward this voluntarily or whether litigation and regulation will force it. My guess is that litigation forces movement in this direction, and then regulation makes it mandatory.

Industry Response and Defensive Statements

When companies are asked about contractor data practices, they typically say something like: "We're very careful about IP. We only use data we have permission to use. We require contractors to remove confidential information. We have tools and processes to ensure compliance."

This is technically true in the sense that companies do try to be careful. But it doesn't address the fundamental issue: contractors often lack the expertise to identify what's confidential, and tools can't fully replace legal review.

I'd expect to see companies gradually shift their statements. Maybe by late 2025 or 2026, we'll see statements like: "We've implemented new procedures requiring explicit permission from original IP owners before data collection." This would be a sign that companies are responding to increased legal risk.

Some companies might even go on offense. Imagine a statement like: "Our competitor uses unverified contractor data. We only use data from licensed sources and don't take this risk." That would be a way to differentiate based on legal practices.

This kind of competitive differentiation actually drives behavior change faster than regulation sometimes does. If Anthropic or Google announces "we have industry-leading legal safeguards for AI training data," other companies have to match that or lose market position.

Broader Implications for AI Development

This contractor data issue is actually part of a bigger story about how AI development works and who captures the value from AI systems.

AI models are trained on data created by human workers, knowledge workers, artists, and all kinds of people. These people don't typically get compensated for their contribution to AI. Their work ends up in training datasets without their permission or knowledge. The AI companies profit from models trained on this data. The people whose work was used don't see any of the value.

This is an extractive model, and it's probably not sustainable long-term. You can't continuously use people's work without permission or compensation before they notice and object.

The contractor data issue is just the most visible version of this. There are lawsuits happening about AI training on images, text, and other creative work. There are ethical questions about whether this model is fair. There are practical business questions about whether it's wise to build your competitive advantage on potentially disputed IP.

I think what we'll see over the next few years is movement toward more compensation and permission-based models. AI companies might license datasets instead of scraping them. They might compensate people whose work ends up in training data. They might build revenue-sharing models where creators get a cut of value created from their work.

This would be more expensive but also more sustainable. And it might actually be better for the public in the long run because it creates proper incentives for people to create data that makes AI systems better.

Conclusion: The Reckoning Is Coming

Open AI asking contractors to upload real work from past jobs is a smart business move that's also legally risky. The company is betting that the value of better training data outweighs the liability risk. They might be right. They might be wrong. We'll probably find out through lawsuits over the next few years.

What's clear is that this practice is unsustainable long-term. Either companies will face legal consequences that force them to change. Or regulators will create requirements that make it illegal. Or competitors will differentiate on legal practices and force industry change. Probably some combination of all three.

For contractors considering uploading past work: actually review what you're uploading. Check your old employment contracts. Understand the risks you're taking. The money might not be worth the liability.

For companies using contractor data: this is worth taking seriously. Invest in proper legal review. Get explicit permissions. Build the right processes now before litigation forces you to.

For the AI industry broadly: this is an opportunity to build more ethical and legal data collection practices. Companies that move first on this might face short-term costs but long-term benefits in terms of reputation, regulatory relationships, and reduced legal risk.

The contractor data story is ultimately a story about how AI development works and who bears the costs and captures the benefits. Right now, the costs are distributed to workers and their employers while benefits concentrate in AI companies. That imbalance creates incentives for litigation and regulation. The question isn't whether things will change. It's how they'll change and how fast.

FAQ

What exactly is Open AI asking contractors to upload?

Open AI and partner company Handshake AI are asking contractors to upload actual files from past and present jobs. This includes Word documents, PDFs, Power Point presentations, Excel spreadsheets, images, and entire code repositories. The contractors are instructed to remove proprietary and personally identifiable information before uploading, using a Chat GPT tool called "Superstar Scrubbing." The goal is to gather high-quality real-world training data that will help AI models better understand and perform actual work tasks.

Is this legal?

It's legally complicated and risky. In most employment relationships, the employer owns intellectual property created by employees. When contractors upload work without explicit permission from their former employers, they're potentially uploading IP that doesn't belong to them. This could violate copyright law, trade secret protection laws, and non-disclosure agreements. Open AI could face liability for acquiring and using potentially stolen IP. An intellectual property lawyer told reporters this approach puts companies "at great risk."

What are the specific legal risks for Open AI?

Open AI faces multiple legal exposures: copyright infringement from uploading work that belongs to prior employers, trade secret liability under the Economic Espionage Act and state trade secret laws, breach of contract if they knowingly use work protected by NDAs, and unfair competition claims from companies whose IP was misappropriated. Additionally, Open AI could face liability for inducing contractors to breach their NDAs. Once a company discovers their proprietary work in an Open AI training dataset, litigation becomes likely.

Why would contractors upload proprietary work when it's potentially illegal?

Contractors might not understand the legal implications of their actions. Many people don't remember what their employment contracts and NDAs actually said years after they left a job. Additionally, contractors have financial incentives to upload more data because they're paid per submission. This creates pressure to include borderline material even if they're unsure about ownership or confidentiality. The contractor probably doesn't realize they could personally be sued for violating their former employer's IP rights.

Can the "Superstar Scrubbing" tool actually make uploads safe?

Probably not sufficiently. While the tool can catch obvious confidential information like company names and employee identities, it often misses nuanced proprietary information like strategic decisions, architectural choices, process flows, or competitive positioning. These elements can constitute trade secrets but aren't the kind of obvious information an AI tool will flag for removal. Contractors also have to tell the tool what to remove. Many contractors lack the legal expertise to understand what counts as confidential, so the tool won't know what to redact without explicit instruction. Human legal review is significantly more reliable than automated scrubbing.

What should contractors do before uploading past work?

Contractors should review their old employment agreements and any NDAs they signed, looking specifically for intellectual property assignment clauses, confidentiality terms, and prohibitions on sharing work. If there's any doubt about whether they own the material or have permission to share it, they should contact their former employer or consult a lawyer before uploading. They should also consider whether the payment justifies the legal risk they're taking on. Even if Open AI takes some responsibility, contractors could still personally face liability if their former employer sues.

Are other AI companies doing this?

Yes. This is becoming standard practice across the AI industry. Handshake AI's platform works with multiple AI companies. Anthropic, Google's Deep Mind, Meta, and smaller AI companies are all using similar contractor data collection approaches. The prevalence of this practice doesn't make it legally safer. It actually increases the risk because if a major court ruling or regulatory action happens, it could affect the entire industry simultaneously.

What happens if a company discovers their IP in an AI training dataset?

The company could sue Open AI and other relevant parties for copyright infringement, trade secret theft, breach of any contractual relationships, and potentially unfair competition. They could also sue the contractors who uploaded the material for violating NDAs or IP assignments. The company might seek damages for the value of the IP, injunctive relief to prevent further use, and potentially punitive damages if willful infringement is proven. Even settlement of such a lawsuit would likely be expensive and damaging to Open AI's reputation.

How long until legal action happens?

Based on current trajectories, major litigation likely happens within 18-24 months. Companies are probably still discovering that their data ended up in training datasets or are deciding whether litigation is worth the cost and disruption. Once the first significant lawsuit settles or reaches trial with substantial damages, other companies will likely follow. Regulatory investigations or Congressional hearings might happen on similar timelines or slightly longer timelines.

Could regulation stop this practice?

Yes. Congress could pass legislation explicitly requiring AI companies to get permission before using contractor-uploaded data in training datasets. The FTC could bring enforcement action against Open AI or other companies for unfair practices. State attorneys general could investigate. These regulatory actions might happen alongside or instead of private litigation. Once regulation is in place, companies have to comply or face penalties, which makes the practice much less attractive regardless of the underlying legal questions.

What's the international dimension?

IP law varies by country, and international liability is another risk for Open AI. The European Union's Trade Secrets Directive provides even stronger protections than U. S. law. The GDPR might restrict collecting and using contractor data. Contractors in different countries have different rights regarding work they created. A contractor in Germany might have different ownership rights over work than a contractor in the United States. This means Open AI could face legal action in multiple jurisdictions simultaneously, each with different legal standards and liability exposure.

Should I use AI tools if they might be trained on stolen IP?

That depends on your risk tolerance and use case. If you're using these tools for non-critical tasks, the risk is probably acceptable. If you're using them for sensitive business work, you might want to consider the risk that the model could regurgitate proprietary information from training data, or that the underlying model might be subject to litigation that affects its future availability. You might also want to avoid depending too heavily on models that could face regulatory restrictions if legal issues emerge. Transparency from AI companies about their training data sources would help users make informed decisions.

What would better legal practices look like?

AI companies could require contractors to provide explicit written proof of IP ownership or permission before uploading material. They could implement human legal review of uploads before data gets integrated into training datasets. They could get indemnification agreements from contractors stating they own the material. They could limit uploads to work created more than a certain number of years ago. They could create systems allowing original employers to verify whether their IP ended up in datasets and challenge uploads they don't approve of. These practices would be more expensive and slower than current approaches, but they would dramatically reduce legal risk.

Could this affect model performance or availability?

Potentially. If lawsuits force Open AI to remove contractor-derived data from training datasets or stop using such data going forward, model retraining might be necessary. This could temporarily reduce model performance until new training approaches catch up. If regulation restricts data collection practices broadly across the industry, all AI companies would face constraints on data availability, which might slow AI development or create temporary performance gaps. However, these effects would likely be temporary as companies adapted to new legal frameworks.

Quick Summary

Open AI is asking contractors to upload real work from past jobs to improve AI training data. This is legally risky because contractors often don't own the work they're uploading, and uploading it could violate NDAs and IP agreements with their former employers. An IP lawyer says this approach puts Open AI "at great risk." The practice is becoming standard across the AI industry, but litigation or regulation could force companies to change their approaches within 18-24 months. For contractors, the financial incentive to upload needs to be weighed against personal legal liability. For AI companies, proper legal safeguards are significantly cheaper than litigation will be.

Key Takeaways

- OpenAI asks contractors to upload actual past work files (PDFs, presentations, code) for AI training, not just descriptions

- Contractors likely own or have permission to share only a fraction of what they upload, creating massive IP and NDA liability

- IP lawyers warn this approach puts OpenAI 'at great risk' because contractors lack expertise to identify confidential material

- Litigation likely within 18-24 months when companies discover their proprietary work in training datasets without permission

- Other AI companies are using identical approaches, suggesting industry-wide vulnerability to coordinated legal action

Related Articles

- Indonesia Blocks Grok Over Deepfakes: What Happened [2025]

- Grok Image Generation Restricted to Paid Users: What Changed [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why the Paywall Isn't Working [2025]

- Grok's Explicit Content Problem: AI Safety at the Breaking Point [2025]

- SandboxAQ Executive Lawsuit: Inside the Extortion Claims & Allegations [2025]

- Grok's AI Deepfake Crisis: What You Need to Know [2025]

![OpenAI Contractors Uploading Real Work: IP Legal Risks [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/openai-contractors-uploading-real-work-ip-legal-risks-2025/image-1-1768081114521.jpg)