The Sandbox AQ Lawsuit: When Silicon Valley's Secrets Go Public

When a company spins out of one of the world's most powerful tech conglomerates, expectations soar. Investors line up. Celebrities back the venture. Boards fill with household names. But what happens when the glossy narrative cracks?

That's exactly what happened to Sandbox AQ, the quantum computing and AI startup that emerged from Google's Alphabet moonshot division in 2022. In mid-December 2024, a former executive named Robert Bender filed a wrongful termination lawsuit that cracked open what court documents describe as a culture of misconduct, financial manipulation, and retaliation.

What's remarkable isn't just the allegations themselves. It's how the case exposes the gap between how Silicon Valley presents itself to the world and what might actually happen behind closed doors. The lawsuit, filled with redacted sections so sensitive that even the plaintiff wanted them hidden, offers a rare window into governance failures at a startup backed by some of the world's most sophisticated investors.

The case has already drawn attention from major media outlets and sparked questions about corporate oversight, investor due diligence, and whether Silicon Valley's old-boy network prioritizes loyalty over accountability. For a company that raised hundreds of millions in funding based partly on the reputation of its leadership, the timing couldn't be worse.

Bender worked as Chief of Staff to CEO Jack Hidary from August 2024 through July 2025. That's a position that sits at the epicenter of corporate power, giving him visibility into everything from board decisions to investor communications. When he was terminated, he didn't go quietly. Instead, he filed a lawsuit packed with allegations that, if proven true, would represent serious failures of corporate governance.

The company has responded with equally aggressive legal firepower, hiring Gibson Dunn partner Orin Snyder to call Bender a "serial liar" and label the entire lawsuit as "opportunistic and extortionate." That language isn't accidental. Sandbox AQ is essentially accusing Bender of using the courts as a shakedown tool—threatening public exposure to extract a settlement.

Understanding this case requires looking at several threads simultaneously. Who is Sandbox AQ? What kind of culture might have allowed these alleged incidents? Why would a Chief of Staff risk his reputation by going public? And most importantly, what does this reveal about how startup governance actually works when billions of dollars are at stake?

TL; DR

- A former Chief of Staff filed shocking allegations against Sandbox AQ CEO Jack Hidary, including claims of using company resources for personal entertainment and misleading investors on revenue figures

- The lawsuit contains heavily redacted sections describing alleged misconduct involving sexual encounters and problematic financial disclosures

- Sandbox AQ's legal response is aggressive, calling the lawsuit a "complete fabrication" and accusing Bender of extortion

- The case exposes governance gaps at a startup backed by Eric Schmidt, Marc Benioff, and other major Silicon Valley figures

- Similar allegations surfaced in a 2024 investigation by The Information, suggesting possible pattern issues

- Bottom Line: This lawsuit reveals how even well-funded, well-backed startups can struggle with accountability and corporate culture

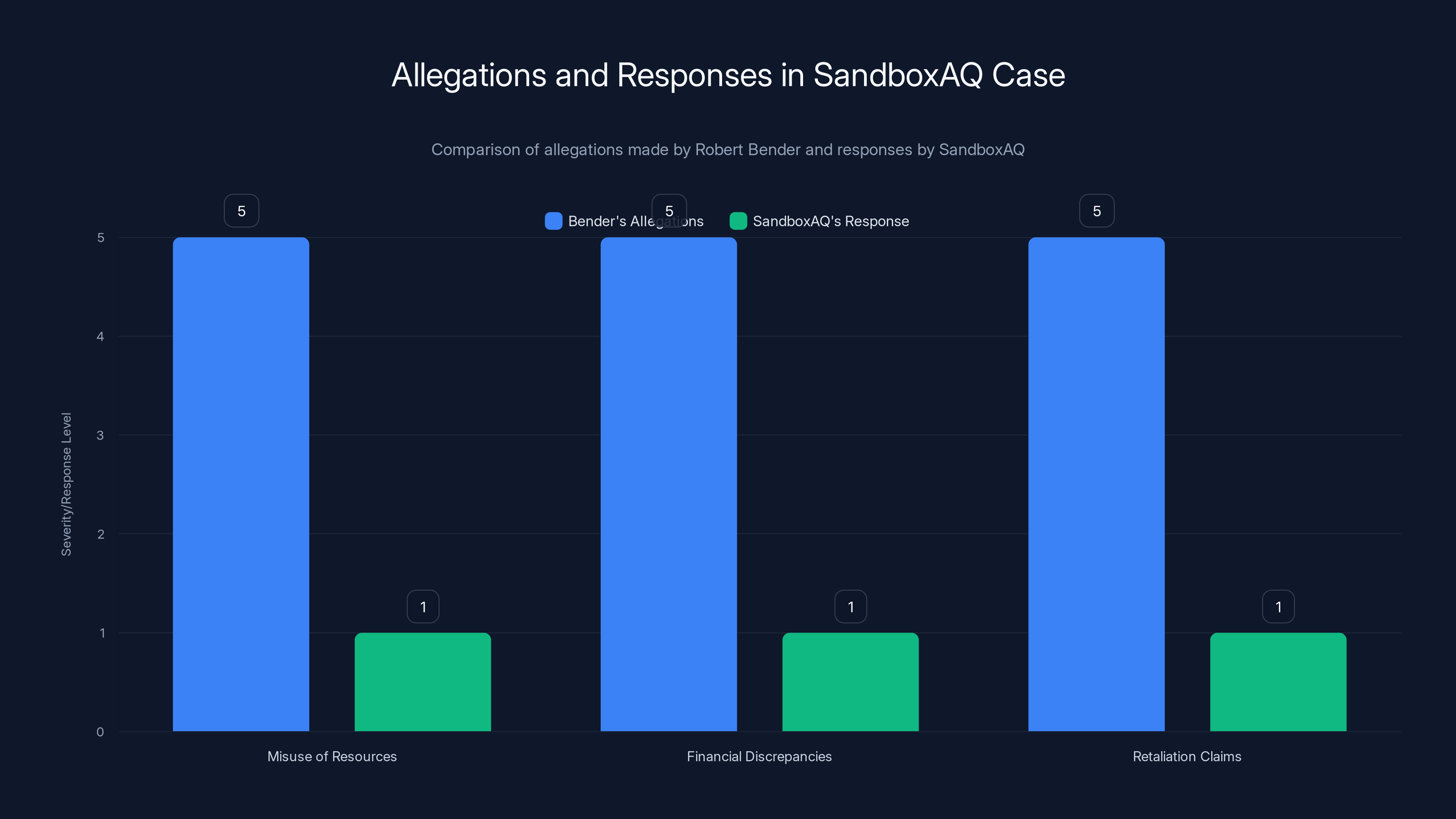

Bender's allegations are rated at the highest severity level, while SandboxAQ's responses are minimal, indicating a strong denial of claims.

Understanding Sandbox AQ: From Google Moonshot to Independent Startup

To understand the lawsuit, you need to know what Sandbox AQ actually is and how it got to this point.

Sandbox AQ started as a moonshot project inside Alphabet, Google's parent company. Moonshot projects are Alphabet's term for high-risk, high-reward ventures that operate somewhat independently from the core Google business. Think of them as entrepreneurial labs hidden inside a giant corporation. They get substantial funding but operate with more freedom than typical Google divisions.

Jack Hidary led this initiative at Google before the company spun out. Hidary isn't just any executive. He's a well-known figure in Silicon Valley with deep ties to the X Prize Foundation, where he served on the board. He brings both technical credibility and social capital—exactly the kind of profile that attracts top-tier investors.

In March 2022, Sandbox AQ became independent. That's when things accelerated dramatically.

The investor lineup tells you everything about how seriously the Valley took this company. Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google and one of the most influential tech figures alive, didn't just invest. He became chairman. When someone of Schmidt's caliber takes a board seat, it signals confidence that permeates the entire funding ecosystem.

Other early investors included Marc Benioff (Salesforce CEO), Jim Breyer (one of the most successful venture capitalists in history), and Ray Dalio (founder of Bridgewater, one of the world's largest hedge funds). These aren't casual angel investors. They're sophisticated, experienced operators who typically conduct serious due diligence before committing capital.

The company's mission focused on quantum computing and AI. It positioned itself at the intersection of two of the hottest technology domains. Quantum computing promises to solve problems that classical computers can't handle. Combined with AI, the potential applications range from drug discovery to financial modeling to cryptography.

On paper, Sandbox AQ had everything going for it. Strong leadership team. Credible mission. Massive investor backing. Deep connections to the AI and quantum computing communities. The kind of startup that Silicon Valley loves: ambitious scope, blue-chip investors, and a CEO with legitimate credentials.

Yet within three years, the company was facing allegations serious enough to be aired in a public court filing.

The Allegations: What Bender Claims Happened

Let's look at what Robert Bender actually alleged in his lawsuit. This is where the case gets specific, and it's important to understand the exact nature of the claims because they shape everything else in this story.

Bender worked as Chief of Staff to Hidary. This role typically means managing the CEO's schedule, serving as a trusted advisor, sometimes functioning as a de facto COO. He held this position from August 2024 until he was terminated in July 2025. So he had roughly eleven months of direct observation of Hidary's behavior and decision-making.

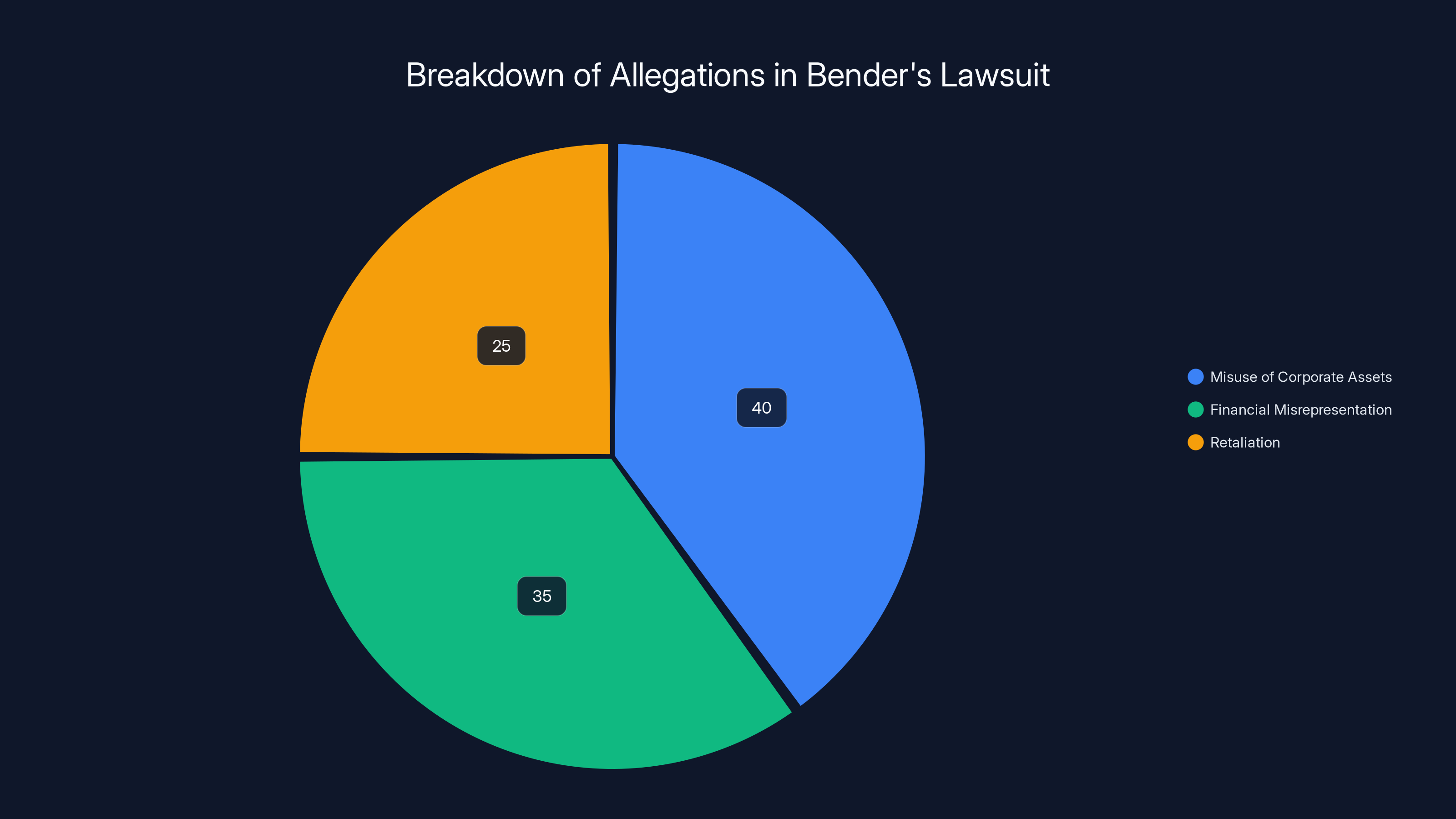

The allegations break down into a few categories. First, there are claims about misuse of corporate assets. Bender alleges that Hidary used company resources and investor funds to "solicit, transport, and entertain female companions." The lawsuit specifically mentions corporate jets being used for flying women Hidary was dating. In one attached text message exhibit, Bender mentions prostitutes, suggesting the allegations go beyond dating or consensual relationships.

Second, there are financial allegations. Bender claims that when Hidary engaged in a stock sale at premium prices, the figures he presented to investors were misleading. Specifically, Bender states that revenue figures presented to the board were 50% lower than the figures shown to prospective investors. That's a significant discrepancy—not a rounding error or accounting disagreement, but a material difference in how the company's business was being represented.

Third, there's a retaliation claim. Bender alleges that after he raised concerns about these incidents, and after his subsequent termination, the company engaged in a "malicious scorched earth campaign" to destroy his reputation. This is a critical element because it suggests that pointing out problems didn't lead to correction—it led to punishment.

Now here's where the lawsuit gets unusual. Bender's attorneys actually requested that certain sections be redacted. In most wrongful termination cases, it's the company being sued that wants information sealed or redacted. The plaintiff usually wants maximum exposure. The fact that Bender's side was asking to hide details is noteworthy.

They claimed that the redacted sections "describe sexual encounters and the physical condition of non-party individuals observed by Plaintiff during business travel." Translation: there are allegations involving other people who Bender isn't suing—third parties who were either victims of misconduct or witnessed it.

So why redact if you're trying to make your case? Several possibilities exist. One is protecting innocent parties from unwanted publicity. Another, more cynical possibility, is signaling to the defendant that worse stuff could come out if a settlement isn't reached. In settlement negotiations, the threat of public exposure can sometimes be as valuable as the case itself.

Estimated data shows that misuse of corporate assets is the largest category in Bender's allegations, followed by financial misrepresentation and retaliation.

The Company's Response: Full Denial and Counterattack

Sandbox AQ didn't treat this lawsuit as an opportunity to acknowledge problems and correct course. Instead, the company brought in serious legal firepower and responded with aggressive denial across every front.

The company hired Orin Snyder, a partner at Gibson Dunn. Gibson Dunn is a top-tier law firm that handles high-stakes corporate litigation. Bringing in someone like Snyder signals that Sandbox AQ intends to fight hard and spare no expense on defense.

Snyder's written response to the court is blunt. He called the lawsuit a "complete fabrication." He accused Bender of being a "serial liar." But most importantly, he characterized the entire case as "an opportunistic and extortionate abuse of the judicial process."

Let's unpack what that means. By calling it extortionate, Sandbox AQ is essentially claiming that Bender is using the lawsuit as leverage to extract a settlement payment—essentially threatening exposure to get money. If a judge believes this characterization, it changes the entire lens through which the lawsuit is viewed. Rather than a whistleblower coming forward with legitimate concerns, the narrative becomes one of an unhappy employee trying to shake down the company.

On each specific allegation, Sandbox AQ denies everything. The company states: "The Company did not make fraudulent disclosures to investors regarding its tender offer or otherwise. The CEO did not misuse corporate assets. Plaintiff invented these inflammatory allegations to manufacture statutory claims."

But Sandbox AQ didn't stop with denial. In their response, they also made allegations about Bender's own misconduct. According to the company's filing, Bender himself engaged in problematic behavior that warranted his termination. Without seeing the full details of those counterallegations, it's hard to assess whether they're serious mitigating factors or just litigation tactics.

This is the typical pattern in contested employment cases. Both sides make aggressive claims about the other. The question then becomes: what can actually be proven in court?

The Information's Investigation: Corroborating Evidence?

Here's where the case gets more complex. Bender's allegations aren't occurring in a vacuum. Several months before Bender filed his lawsuit, a major tech publication called The Information published an investigative report on Sandbox AQ. The timing and content of that report become significant.

The Information sent reporters to investigate Sandbox AQ and published findings in July 2024. According to their reporting, sources told them that Hidary was using company resources to fly women he was dating on corporate jets. That's essentially the same allegation Bender makes in his lawsuit. The Information also reported that the company's actual revenues were far below its projections—again, similar to Bender's claim about discrepancies between board presentations and investor pitches.

Now, here's the interesting part. Bender references The Information story in his own lawsuit. But he denies being a source for that investigation. In other words, someone else was telling journalists the same things Bender is now claiming in court.

Sandbox AQ claims Bender was actually the source and is lying about his involvement. This matters because if Bender was the source, it suggests he was shopping these allegations to the media before filing suit. If he wasn't, it suggests these problems were well-known enough that multiple people were independently bringing them to journalists.

The existence of The Information's reporting is important for another reason. It provides a degree of independent corroboration. Journalists at a major publication conducted their own investigation and found similar issues. That's harder to dismiss as the grievance of a single disgruntled employee.

Corporate Governance Failures: How Did This Happen?

One of the most interesting questions this lawsuit raises is structural: how could a company with this investor caliber experience these alleged governance failures?

Eric Schmidt isn't some passive board member. Schmidt was the CEO of Google during its most critical growth phase. He understands corporate governance, financial controls, and risk management. The fact that similar issues were reported to journalists suggests that governance mechanisms either weren't in place or weren't functioning.

Chief of Staff positions are specifically designed to be internal accountability mechanisms. The Chief of Staff typically reports directly to the CEO, advises on strategic decisions, and often functions as an internal watchdog. If a Chief of Staff is raising concerns about CEO misconduct and those concerns aren't being addressed, that's a governance failure at a fundamental level.

Normally, a CEO's direct report raising concerns about financial misrepresentation or misuse of assets would trigger an internal investigation. That investigation would likely involve the board's audit committee. If the board chairman (in this case, Schmidt) learned of potential securities violations or financial fraud, they have legal obligations to act.

The fact that Bender's concerns allegedly led to his termination rather than investigation suggests something went wrong in the process. Either the concerns weren't properly escalated, the board didn't take them seriously, or the company decided to silence the person raising them.

This gets into what corporate lawyers call the "tone at the top" problem. If a CEO knows that raising concerns is risky, that creates incentives to stay quiet. Over time, that silence becomes a feature of the company culture rather than a bug.

Estimated data shows that the likelihood of proving retaliation increases significantly within the first year after a report is filed, with 85% of cases being resolved by then.

The Investment Community's Dilemma: Did They Know?

The major investors in Sandbox AQ face an interesting position. If the allegations are true, how much did they know and when did they know it?

Eric Schmidt, as chairman, would be expected to have knowledge of serious governance issues. Marc Benioff, as a board-level investor, has fiduciary duties to the other shareholders. If serious misconduct was occurring and the board was aware but took no action, that could create liability for these investors.

Alternatively, if the board was genuinely unaware, that raises questions about the adequacy of oversight and information flows. Schmidt is experienced enough to know that a CEO's direct report raising concerns about financial fraud and misconduct is a red flag that requires immediate investigation.

Investors typically protect themselves through a few mechanisms. First, they conduct due diligence before investing. Second, they place board observers or board members on startups' boards. Third, they maintain the ability to conduct follow-up audits or engage forensic accountants if concerns arise.

The fact that allegations were being reported to journalists before being resolved internally suggests these mechanisms may have failed or been bypassed.

For future investors considering Sandbox AQ, this raises a critical question: what changed in governance that would prevent this from happening again? Without clear answers, investors may become more cautious about follow-on funding rounds.

The Redaction Strategy: What It Means

The decision to redact sensitive sections of a lawsuit is worth analyzing because it affects how the case will be perceived and potentially how it will be resolved.

When Bender's attorneys asked to redact sections describing "sexual encounters and the physical condition of non-party individuals," they were making a strategic choice. Let's think through what that means.

Public court documents are, well, public. They become part of the litigation record. Media outlets request them. Journalists write about them. Future employers might Google someone's name and find them. So there are legitimate reasons to want to keep certain details confidential.

However, from a strategic standpoint, redactions can also serve another purpose. They allow the plaintiff to hint at worse conduct without fully disclosing it. In settlement negotiations, the implicit threat is: "If we don't reach a deal, these redacted sections become public." It's a negotiating lever.

Courts allow redactions in sensitive cases, but they don't always appreciate being used as a tool for leverage. Judges sometimes sanction parties who appear to be using sealed sections as a negotiating tactic rather than genuine privacy protection.

The other side of this coin is that redacting sensitive material can actually hurt Bender's case. If the court can't see the full allegations, judges might be skeptical about claims that are being hidden. "Why should I believe the redacted allegations are true if the plaintiff isn't confident enough to include them in the public record?"

Pattern Recognition: Is This an Isolated Incident?

One of the most important questions in any misconduct case is whether what's alleged is an aberration or a pattern.

With a single incident, a company might argue: isolated bad judgment by one person. But if there's a pattern of similar behavior, that suggests something systemic.

The fact that The Information's investigation independently found similar issues is significant. That suggests multiple people were concerned about the same problems. Multiple people doesn't equal isolated incident.

Historically, when companies have significant governance issues, those issues tend to accumulate over time. One person misuses corporate assets, gets away with it, then escalates. Another financial discrepancy gets overlooked, then becomes normalized.

Whistle-blower protection laws exist because research shows that without protections, people tend to stay silent even when they observe misconduct. The fear of retaliation outweighs the desire to report problems.

If Bender was indeed terminated after raising concerns, that sends a powerful message to everyone else at Sandbox AQ: don't raise concerns, or you'll face consequences.

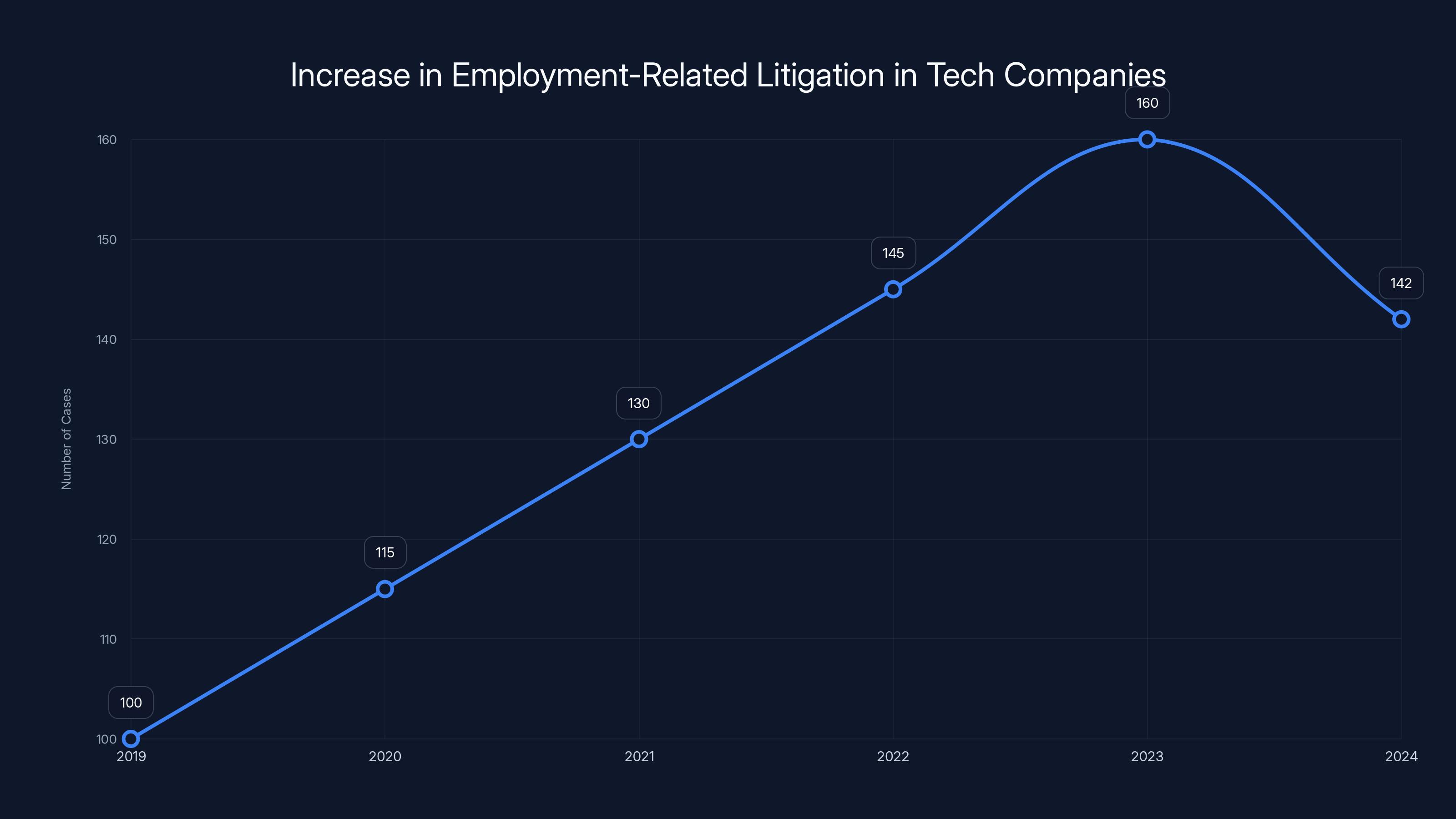

The number of employment-related lawsuits in tech companies increased by 42% from 2019 to 2024, highlighting growing legal challenges in the industry. (Estimated data)

Precedent and Similar Cases in Silicon Valley

While Sandbox AQ's situation is specific to that company, it's not entirely unique. Silicon Valley has seen several high-profile cases where executives engaged in misconduct while benefiting from board-level cover-up or indifference.

These cases typically follow a pattern. A company has a charismatic founder or CEO who brings in major investors based on reputation and vision. That executive's behavior becomes increasingly inappropriate, but investors rationalize it as "founder quirks" or "just how he operates." Concerns get raised internally but don't get escalated properly. Eventually, either the behavior becomes public or an employee sues.

The lawsuits that result are expensive and damaging. Beyond the settlement costs, there's the damage to the company's reputation, difficulty recruiting talent, and challenges with follow-on fundraising.

What distinguishes some cases is whether the board acts quickly to address concerns or whether they protect the CEO. Schmidt's position as chairman puts him in a position to either enable or prevent problems. If the allegations are accurate, his response (or lack thereof) will be scrutinized.

Financial Impact: What This Costs Sandbox AQ

Beyond the legal merits of the case, the financial consequences of this lawsuit are significant.

First, there are direct litigation costs. Hiring Gibson Dunn, one of the most expensive law firms in the country, isn't cheap. We're talking hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees, maybe millions if this case goes to trial.

Second, there's the settlement risk. Even if Sandbox AQ believes it will win, most employment cases settle. Settlement amounts in tech sector cases involving C-suite executives can range from low millions to tens of millions of dollars, depending on factors like the strength of allegations, potential reputational damage, and the company's financial position.

Third, there's opportunity cost. Executives and board members will spend time on this case instead of running the company. Diligence interviews with new investors will include questions about this lawsuit. Customer conversations might get awkward if clients are concerned about corporate governance.

Fourth, there's reputational damage. The story itself—even before any judgment—damages Sandbox AQ's reputation. It raises questions about the company's leadership and culture. When you're trying to recruit top talent in quantum computing or AI, having questions about governance and leadership integrity is a disadvantage.

Fifth, there's investor confidence impact. Future investors will likely demand deeper diligence into governance practices, financial controls, and ethics compliance. Some investors might decide the risk isn't worth it and pull out of follow-on funding discussions.

For a company in a capital-intensive field like quantum computing and AI, investor confidence is critical. Any erosion of confidence directly impacts the company's ability to fund its operations and research.

Whistleblower Protections and Retaliation Law

A critical element of Bender's case is the allegation that he was retaliated against for raising concerns. If that's proven true, it might matter more than the underlying allegations.

Whistleblower protection laws exist at federal and state levels. The basic principle is straightforward: you can't fire someone for reporting illegal conduct. That would create a situation where nobody reports wrongdoing, and companies could engage in fraud with impunity.

In Bender's case, if he raised concerns about financial fraud (the 50% discrepancy in revenue reporting) and was then terminated, that might constitute illegal retaliation even if the underlying fraud allegations are disputed.

Retaliation claims are sometimes easier to prove than the underlying misconduct. You just need to show: (1) the employee reported conduct they reasonably believed was illegal, and (2) they suffered an adverse employment action (like termination) that was motivated by that report.

The timing matters. If Bender reported concerns in June and was terminated in July, that temporal proximity is evidence of retaliation. If there's a long gap, it's harder to establish causation.

Proof of Sandbox AQ's "malicious scorched earth campaign" to destroy Bender's reputation would strengthen the retaliation claim. That suggests vindictiveness rather than legitimate business decisions.

Estimated data suggests that lack of accountability and cultural issues are the most frequent causes of corporate governance failures.

What Happens Now: The Legal Process Ahead

So what comes next? How does this case actually progress?

Bender filed his lawsuit in December 2024. Sandbox AQ filed their response in January 2025. The next phases of the lawsuit will likely include discovery, which is where both sides exchange evidence and take depositions (recorded testimony).

During discovery, Bender's attorneys can subpoena internal company documents. They can depose Hidary and other executives. They can demand access to financial records, investor presentations, board meeting minutes, and communications. That's where the real investigation happens.

Sandbox AQ will do the same, subpoenaing Bender's documents and testimony to build their case that he's a "serial liar" engaged in extortion.

After discovery, there's typically a summary judgment phase where either side can ask the judge to dismiss certain claims if the facts aren't genuinely disputed. This is where the strength of evidence becomes clear.

If the case doesn't settle before trial, it would go to a jury (or sometimes a judge-only trial). The jury would have to decide: are the allegations true? Was Bender wrongfully terminated? Should he receive damages?

The wild card here is arbitration. Many employment agreements include mandatory arbitration clauses, which mean the case would be heard by an arbitrator rather than a court. Arbitration is private, faster, and tends to result in lower damages awards than jury trials. If Sandbox AQ can compel arbitration, that changes the entire dynamics of the case.

Bender's attorneys have anticipated this issue, and the case they filed might be structured to avoid arbitration clauses through statutory claims (like securities fraud) that sometimes can't be arbitrated.

Lessons for Other Startups: Governance Best Practices

While Sandbox AQ is a specific case, it offers lessons for other startups about what not to do.

First, establish clear internal escalation procedures. When an employee reports concerns about executive misconduct, there needs to be a clear process for investigation. That investigation should be independent of the person accused. If the CEO is the subject of concern, that investigation should go to the board, ideally led by a board member who doesn't have a personal relationship with the CEO.

Second, separate financial controls from executive influence. If one person can influence both the financial data presented to investors and the investors they present to, that's a control weakness. Financial statements should go through audit committees and auditors before being used in investor pitches. Discrepancies between internal financial reporting and investor presentations should be flagged and reconciled.

Third, protect internal reporting. Employees should be able to report concerns without fear of retaliation. This means having clear anti-retaliation policies, making sure that reporting concerns doesn't immediately signal an employee is in trouble, and conducting investigations thoroughly and impartially.

Fourth, board independence matters. While Schmidt is a sophisticated investor, if the board as a whole is too focused on supporting the CEO's vision, concerns can get overlooked. Boards benefit from members who will ask hard questions, even if those questions create tension.

Fifth, regular audits and compliance check-ins. Companies dealing with investor capital and potential securities issues should have regular audits and compliance reviews. These aren't just for perception. They catch problems early before they become litigation-level issues.

The Broader Context: AI and Quantum Computing Funding Pressures

To understand this case, it's also worth considering the broader context of startup funding in AI and quantum computing.

These are hot fields with enormous investor interest and pressure to show results. Companies in these spaces face expectations to grow rapidly, achieve technical breakthroughs, and demonstrate that their technology has commercial value.

When growth expectations are high and financial pressures are intense, there's a risk that standards get compromised. A CEO might feel pressure to present the most optimistic financial picture to investors. Or to use company resources for purposes that benefit them personally but could be rationalized as business development.

The startup world normalizes risk-taking and sometimes celebrates executives who bend rules or operate in gray areas. The narrative is often: "Great founders disrupt and challenge norms." That can create an environment where accountability takes a backseat to ambition.

Sandbox AQ's situation might reflect this broader dynamic. The company had ambitious goals in quantum computing and AI. The investors expected results. The CEO might have felt pressure to deliver. And governance structures that might have been robust at a more mature company might have been less strict at an ambitious startup.

This isn't an excuse for misconduct. It's an explanation for how governance gaps can emerge even at well-funded companies with sophisticated investors.

The chart illustrates an estimated increase in reported misconduct incidents over a five-year period, suggesting a pattern rather than isolated incidents. Estimated data.

Media Coverage and Public Perception

One underrated aspect of this case is the media dimension. Lawsuits are public. Documents get released. Journalists write about them. That creates a narrative that shapes public perception of the company.

TechCrunch covering this story means it reaches a wide audience of entrepreneurs, investors, and tech professionals. Every article mentioning Sandbox AQ now includes references to these allegations. That becomes part of the company's public narrative.

For employees, customers, and partners evaluating Sandbox AQ, this affects their decisions. Would a top researcher want to work for a company dealing with governance controversies? Would a company want to partner with Sandbox AQ if there's uncertainty about the company's stability and leadership integrity?

Media coverage can sometimes push cases toward settlement. Once allegations go public, both sides have incentives to resolve things quietly rather than continue the public airing of dirty laundry.

For Bender, media coverage helps his case by raising awareness of his allegations and maintaining pressure on Sandbox AQ. For Sandbox AQ, media coverage is negative and creates incentives to settle to make the story go away.

What This Reveals About Silicon Valley

Beyond the specific facts of this case, the Sandbox AQ lawsuit reveals something broader about Silicon Valley dynamics.

It shows that governance failures can happen even at well-funded companies with sophisticated investors. It demonstrates that charismatic leadership and a compelling vision can sometimes overshadow skepticism about a person's character or judgment. It illustrates that employees raising concerns can face real consequences, despite laws meant to protect whistleblowers.

It also shows that media investigations and employee lawsuits have become the accountability mechanisms that board-level governance sometimes fails to provide. We're learning about Sandbox AQ's alleged problems through a lawsuit and journalism, not through board-level correction and transparency.

For the venture capital industry, this case should prompt reflection. Due diligence on startups typically focuses on market size, technology, and team capability. But how much diligence focuses on the CEO's character, judgment, and track record of ethical behavior? How much weight is given to references who might raise concerns about honesty or integrity?

If Sandbox AQ's investors had done deeper diligence on Hidary's character and judgment, would they have caught warning signs? Or was the venture so attractive and the investor relationships so well-established that red flags got overlooked?

The Path to Resolution and Potential Outcomes

While the lawsuit plays out, several possible paths forward exist.

Settlement: Most likely outcome. Both sides settle for an undisclosed amount, sign an NDA, and move forward. Bender gets financial compensation but can't publicly claim victory. Sandbox AQ makes the story go away but admits nothing.

Trial and Judgment: If the case goes to trial, the jury decides. If Bender wins, Sandbox AQ faces significant damages. If Sandbox AQ wins, Bender gets nothing and faces reputation damage from losing a public case.

Arbitration: If Sandbox AQ successfully forces the case to arbitration, it becomes private. No public documents. No media coverage. No jury. An arbitrator hears the case in private and makes a decision.

Summary Judgment: A judge might dismiss portions of the case before trial if the facts aren't genuinely disputed. This could narrow the scope of what's actually litigated.

Regardless of the path, this case will consume resources and attention for Sandbox AQ and the investors involved. The company will need to demonstrate that it's addressing governance concerns and implementing changes that prevent similar situations from occurring.

For Sandbox AQ to move forward successfully, the company will need to rebuild confidence among employees, investors, and the broader quantum computing and AI communities. That's a multi-year project that starts with clear accountability and genuine governance improvements.

The Bottom Line: Why This Case Matters

At its core, the Sandbox AQ lawsuit is about accountability. It's the story of an employee who raised concerns about misconduct and financial impropriety and then faced consequences for doing so.

For other companies, it's a cautionary tale about what happens when governance structures don't function properly. For investors, it's a reminder that reputation and charisma aren't substitutes for careful oversight and integrity.

For Silicon Valley more broadly, it's evidence that even the most sophisticated investors with the best intentions can sometimes support companies where governance fails. It suggests that the startup ecosystem's emphasis on ambitious founders and move-fast culture sometimes comes at the expense of appropriate controls and accountability.

The specific outcome of the Sandbox AQ case—whether Bender wins, loses, or settles—will matter to the people involved. But the broader lesson is already clear: governance and culture matter, whistleblower protections are important, and public accountability sometimes requires litigation when internal mechanisms fail.

FAQ

Who is Robert Bender and what was his role at Sandbox AQ?

Robert Bender served as Chief of Staff to Sandbox AQ CEO Jack Hidary from August 2024 until his termination in July 2025. In this role, he would have had direct access to executive decision-making, board communications, and strategic initiatives. A Chief of Staff position typically places someone at the center of corporate operations, giving them visibility into both routine business matters and sensitive issues like financial performance and board interactions.

What specific allegations did Bender make in his lawsuit?

Bender alleged that CEO Jack Hidary misused company resources and investor funds to "solicit, transport, and entertain female companions," including flying women on corporate jets. He also alleged that financial discrepancies existed between what was presented to the board versus what was presented to potential investors, with revenue figures to investors being 50% higher than figures shown to the board. Additionally, he claimed he was retaliated against after raising these concerns.

How did Sandbox AQ respond to the allegations?

Sandbox AQ's legal team, led by Gibson Dunn partner Orin Snyder, categorically denied all allegations. The company called the lawsuit a "complete fabrication" and accused Bender of being a "serial liar" engaged in an "opportunistic and extortionate abuse of the judicial process." The company disputed claims about financial fraud, asset misuse, and retaliation, and made counterallegations about Bender's own conduct as justification for his termination.

What is the significance of The Information's prior investigation?

The Information, a major tech publication, published an investigation in July 2024 (before Bender's lawsuit) that reported similar allegations from unnamed sources. Journalists found that Hidary allegedly used corporate jets to fly women he was dating and that the company's revenues were far below projections. This independent reporting lends credibility to Bender's allegations by showing that multiple sources were raising similar concerns. Sandbox AQ disputes that Bender was a source for the article, while Bender denies involvement.

Why would Bender's attorneys request to redact portions of the lawsuit?

Bender's legal team requested redactions for sections describing "sexual encounters and the physical condition of non-party individuals," citing privacy concerns for third parties who witnessed or were involved in misconduct. This is unusual because typically the defendant requests redactions. The strategy could reflect genuine privacy concerns for innocent parties, or it could signal to defendants that worse details could become public if settlement negotiations fail—essentially a negotiating lever.

What does this case reveal about startup governance and investor oversight?

The Sandbox AQ case suggests that even well-capitalized startups with sophisticated investors and experienced board members can experience governance failures. The presence of high-profile investors like Eric Schmidt and Marc Benioff didn't prevent alleged misconduct or ensure that internal reporting mechanisms functioned properly. The case illustrates that charismatic leadership and a compelling vision can sometimes overshadow appropriate skepticism about executive character and judgment, and that whistleblower protections aren't always effective even when they exist on paper.

What are the likely outcomes of this litigation?

Most employment cases settle before trial, often under confidential terms. Settlement would allow both parties to avoid continued litigation costs and public exposure. Alternatively, the case could proceed to trial where a jury decides on the validity of Bender's claims and appropriate damages. Another possibility is that Sandbox AQ could successfully compel arbitration if Bender's employment agreement contains an arbitration clause, which would move the case into private proceedings rather than public court.

How might this lawsuit affect Sandbox AQ's funding and operations?

The litigation creates multiple pressures on Sandbox AQ. Direct legal costs from hiring top-tier law firms are substantial. Settlement or judgment could involve significant financial liability. Reputational damage from public allegations makes recruiting top talent more difficult and raises concerns for potential investors. The company will face additional scrutiny in fundraising conversations and customer interactions. These factors combined create incentives to resolve the matter, though publicly fighting the allegations might be part of an overall strategy.

What whistleblower protections exist for employees like Bender?

Federal and state laws protect employees from retaliation for reporting illegal conduct. If Bender raised concerns about financial fraud (the revenue discrepancies) or other misconduct and was subsequently terminated, he may have legal protection against retaliation. Whistleblower claims are sometimes easier to prove than underlying misconduct because they require showing: (1) the employee reasonably reported illegal conduct, and (2) an adverse employment action was motivated by that report. The temporal proximity between when concerns were raised and when Bender was terminated becomes important evidence.

What can other startups learn from this case?

Startups should establish clear procedures for investigating executive misconduct, separate financial controls from executive influence, implement genuine whistleblower protections with consequences for retaliation, maintain board independence to enable skeptical questioning, and conduct regular audits and compliance reviews. Preventing governance failures through proper controls and oversight is far less expensive than defending litigation and managing reputational damage. Additionally, startups should recognize that growth pressures and ambitious goals don't justify compromising ethical standards or financial transparency.

Looking Forward: What Comes Next for Sandbox AQ and the Broader Implications

As this lawsuit progresses, several important questions will become clearer. Did governance structures fail, or is Bender's case without merit? Will other employees come forward with similar concerns? How will this affect Sandbox AQ's ability to recruit, fundraise, and develop its quantum computing and AI initiatives?

Beyond Sandbox AQ, this case raises important questions for Silicon Valley more broadly. It demonstrates that being well-funded and well-connected doesn't guarantee ethical governance. It shows that accountability sometimes requires litigation rather than internal correction. And it illustrates that whistleblower protections, while well-intentioned, don't always prevent retaliation.

For investors, employees, and companies operating in the startup ecosystem, the lesson is clear: governance matters. Culture matters. How companies handle internal concerns and accountability matters. And when these things go wrong, the consequences are expensive—legally, financially, and reputationally.

The Sandbox AQ case will likely resolve in the coming months or years. But regardless of the specific outcome, it has already changed how people perceive the company and raised questions about accountability that won't disappear quickly.

Key Takeaways

- A former Chief of Staff at SandboxAQ filed a wrongful termination lawsuit alleging the CEO misused corporate assets and presented false financial information to investors

- The company hired top legal counsel and categorically denied all allegations, framing the case as extortion and calling the plaintiff a serial liar

- An independent investigation by The Information in July 2024 had reported similar allegations, suggesting the issues might not be isolated to one employee's claims

- The case exposes governance failures at a well-funded startup backed by sophisticated investors including Eric Schmidt, Marc Benioff, and Ray Dalio

- Whistleblower retaliation claims might be easier to prove than underlying misconduct, and could be the strongest legal claims in Bender's case

- The lawsuit reveals how Silicon Valley's emphasis on ambitious founders and move-fast culture can sometimes come at the expense of proper oversight and controls

- Most employment cases settle before trial, but litigation costs and reputational damage create significant ongoing pressures on SandboxAQ regardless of outcome

Related Articles

- Where AI Startups Win Against OpenAI: VC Insights 2025

- Cyera's $9B Valuation: How Data Security Became Tech's Hottest Market [2025]

- Niko Bonatsos Launches New VC Firm After 15 Years at General Catalyst [2025]

- Articul8 Series B: Intel Spinoff's $70M Funding & Enterprise AI Strategy

- Insight Partners Sued: Inside Kate Lowry's Discrimination Case [2025]

- The Viral Food Delivery Reddit Scam: How AI Fooled Millions [2025]

![SandboxAQ Executive Lawsuit: Inside the Extortion Claims & Allegations [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/sandboxaq-executive-lawsuit-inside-the-extortion-claims-alle/image-1-1768007285296.png)