Paramount vs Warner Bros. Discovery: The Netflix Merger Battle That's Reshaping Hollywood [2025]

What happens when a media giant gets rejected? It sues. And that's exactly what Paramount did when Warner Bros. Discovery said no to its advances.

This isn't just another corporate squabble. This is a battle that reveals how broken the media landscape has become, how streaming economics force companies into impossible corners, and why traditional content empires are fighting for survival against companies they once dominated.

Let me walk you through what's actually happening here, because the headlines don't capture the real story.

TL; DR

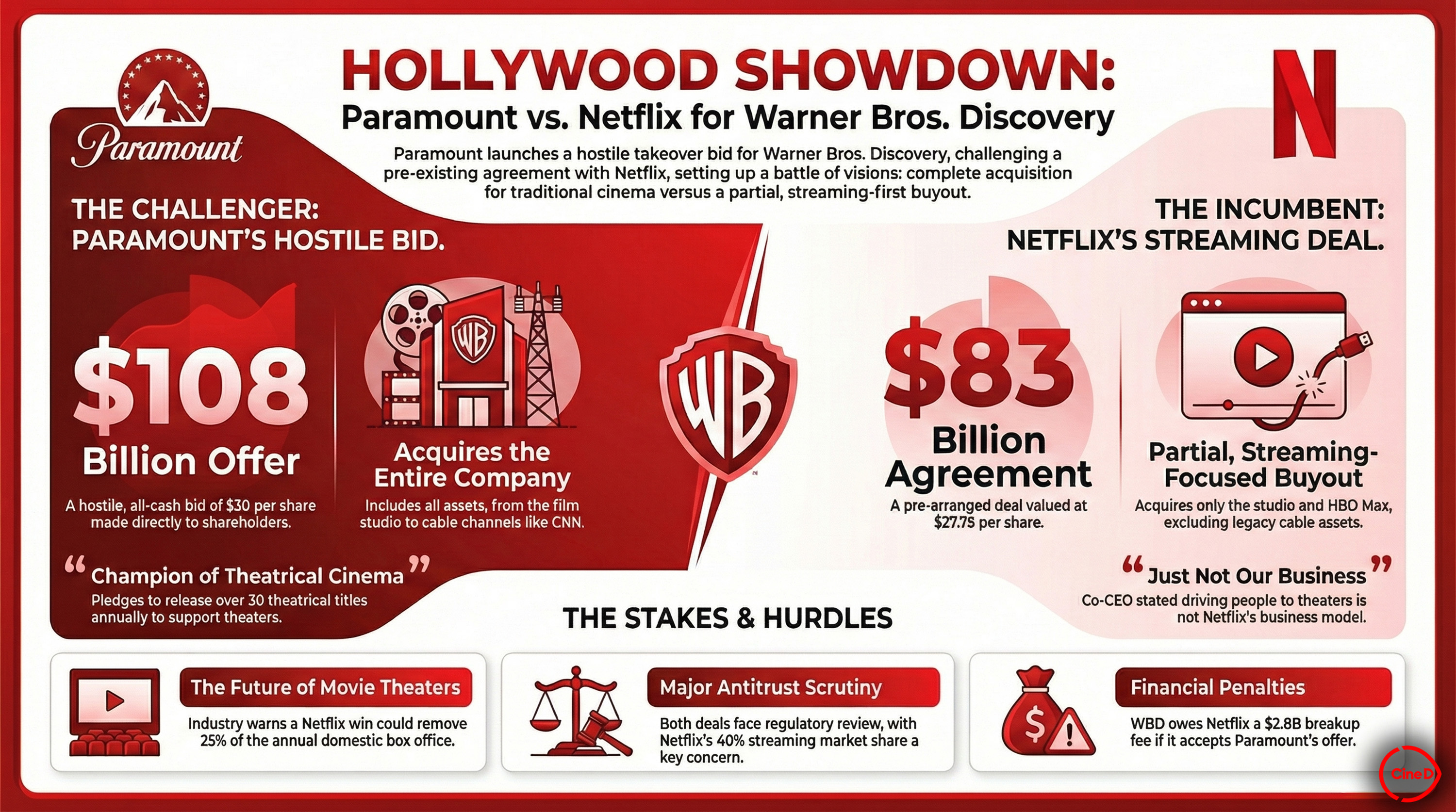

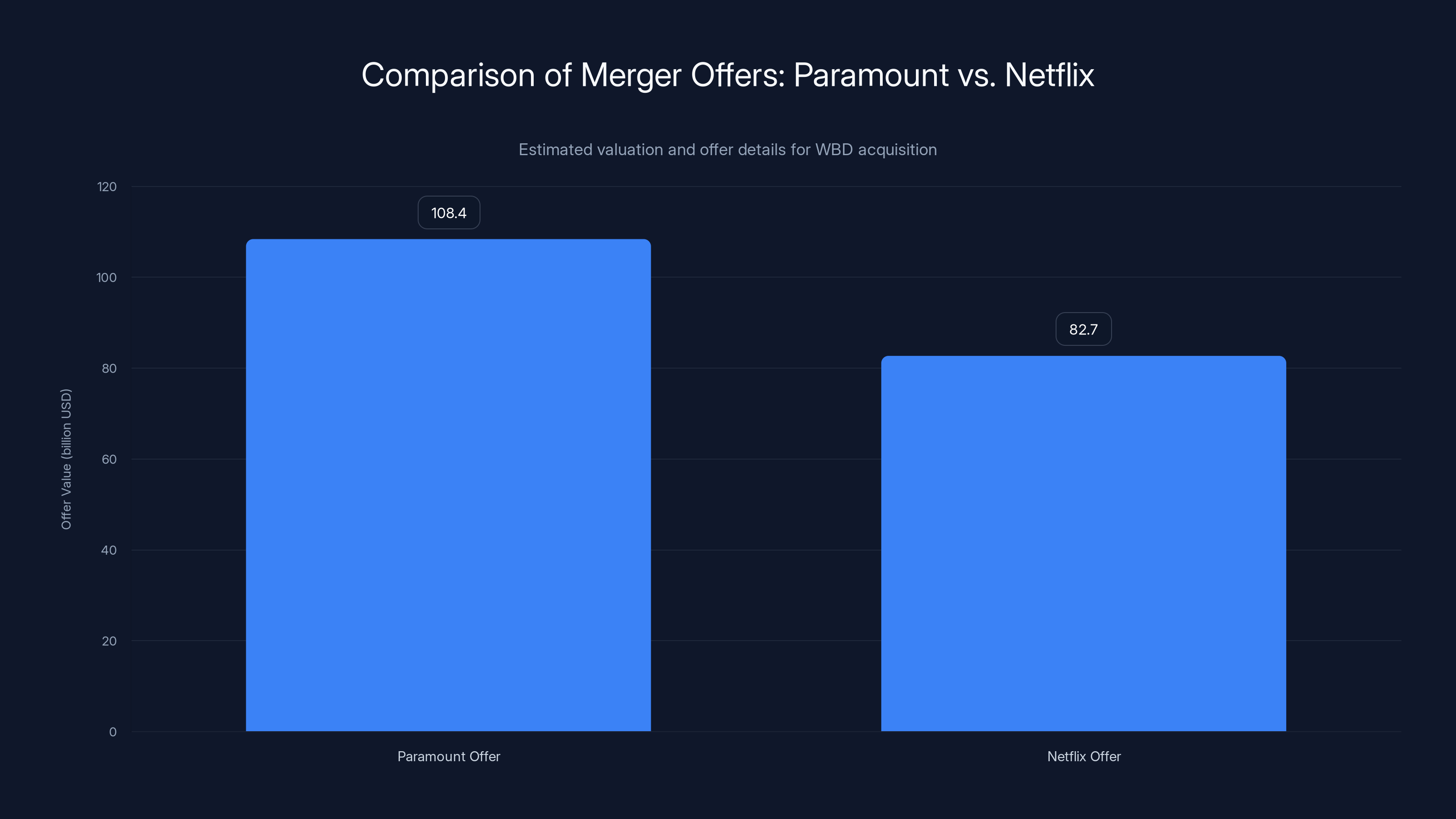

- The Core Issue: Paramount filed a lawsuit demanding Warner Bros. Discovery disclose details about its $82.7 billion Netflix merger, arguing shareholders deserve transparency.

- The Hostile Bid: Paramount launched a $108.4 billion hostile takeover attempt in December to acquire all of WBD, which was rejected.

- The Strategic Move: Paramount CEO David Ellison plans to nominate board directors who could vote to reconsider Paramount's offer.

- The Real Stakes: This lawsuit forces disclosure of Netflix's valuation methodology, giving Paramount ammunition to argue its competing deal is better.

- Bottom Line: The media industry consolidation game just entered a new phase where nothing is off-limits and shareholder disclosure becomes a weapon.

Netflix's

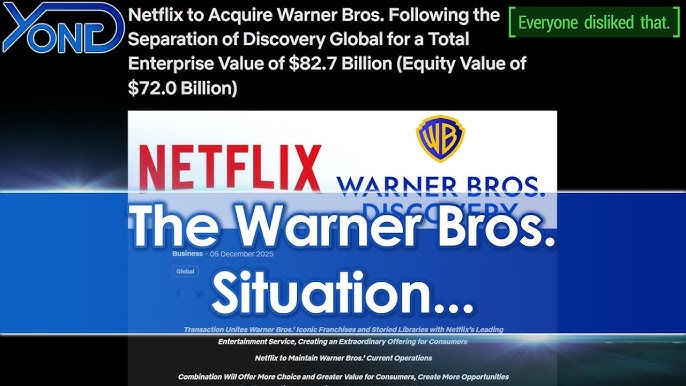

Understanding the Original Netflix Deal: What Warner Bros. Discovery Actually Agreed To

Let's start with the anchor event here. Warner Bros. Discovery didn't wake up one day and decide to sell itself to Netflix. This deal emerged from genuine desperation.

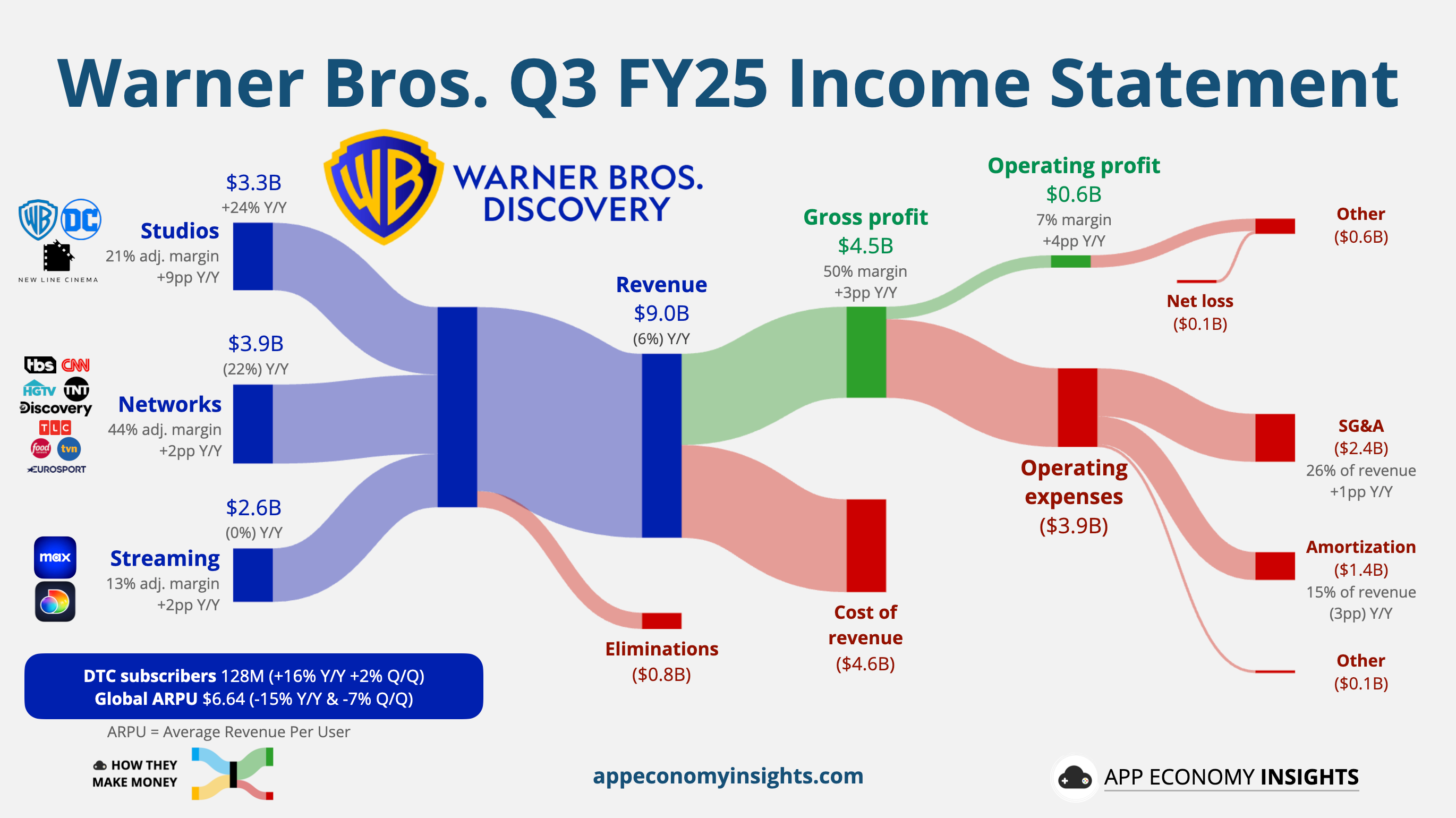

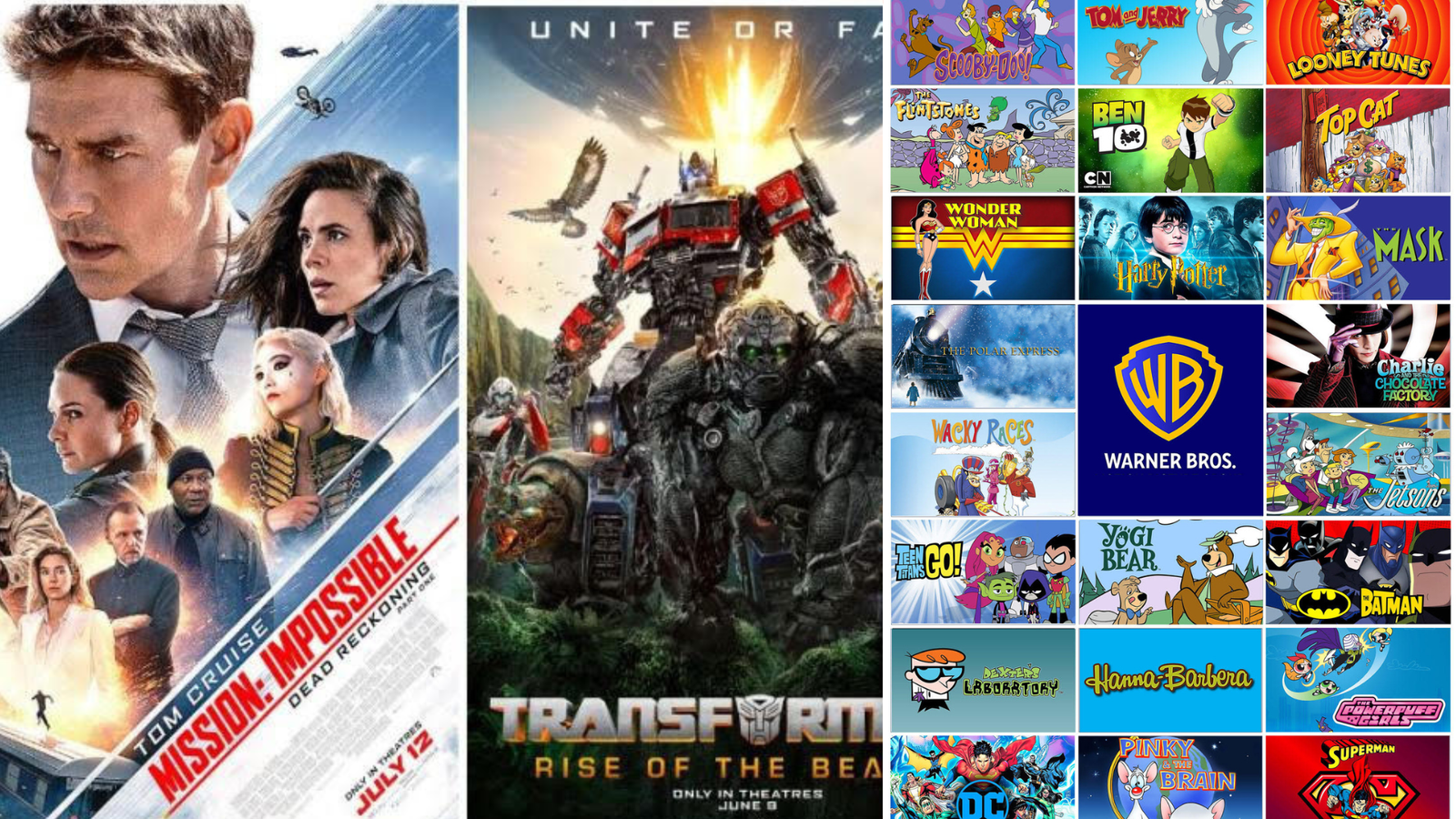

Netflix is acquiring Warner Bros. Discovery's studio operations, HBO, and HBO Max for $82.7 billion. Think about that number for a moment. That's nearly equal to the entire market capitalization of many Fortune 500 companies.

Why did Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav accept this? Because streaming is a meat grinder. The financial model that worked for decades in traditional media collapsed the moment Netflix demonstrated you could build a

WBD was hemorrhaging cash trying to compete with Netflix. HBO Max (now Max) required billions in annual content spending just to stay relevant. The company was caught between two impossible choices: invest enough to compete with Netflix or admit defeat.

The deal with Netflix essentially says "you win." Netflix takes all the content creation infrastructure, all the premium content franchises, and all the streaming infrastructure. WBD gets $82.7 billion in cash and escapes the streaming arms race.

But this deal wasn't inevitable. WBD actually entertained other offers first. Several companies circled the company, smelling blood in the water. And then Paramount made its move.

Paramount's Strategic Desperation: Why a $108.4 Billion Bid Even Makes Sense

Understanding Paramount's move requires understanding its existential problem. Paramount is trapped in the same streaming squeeze as WBD, except worse.

Paramount owns Paramount+, which has bled subscribers and money for years. The company's traditional media business (linear television networks) is in terminal decline. Movie theaters are seeing fewer releases and lower attendance.

So what's Paramount's logical move? Combine with a competitor to create scale. A merged Paramount-WBD would control an enormous library of content, multiple streaming platforms, and enough leverage to negotiate better terms with Apple, Amazon, and others.

The $108.4 billion all-cash offer that Paramount launched in December represents betting the entire company on one consolidation play. This isn't casual M&A activity. This is survival.

But WBD's board rejected it. Twice. Even after Paramount increased the offer.

The stated reason? The Netflix deal is better. But here's where Paramount smells a problem.

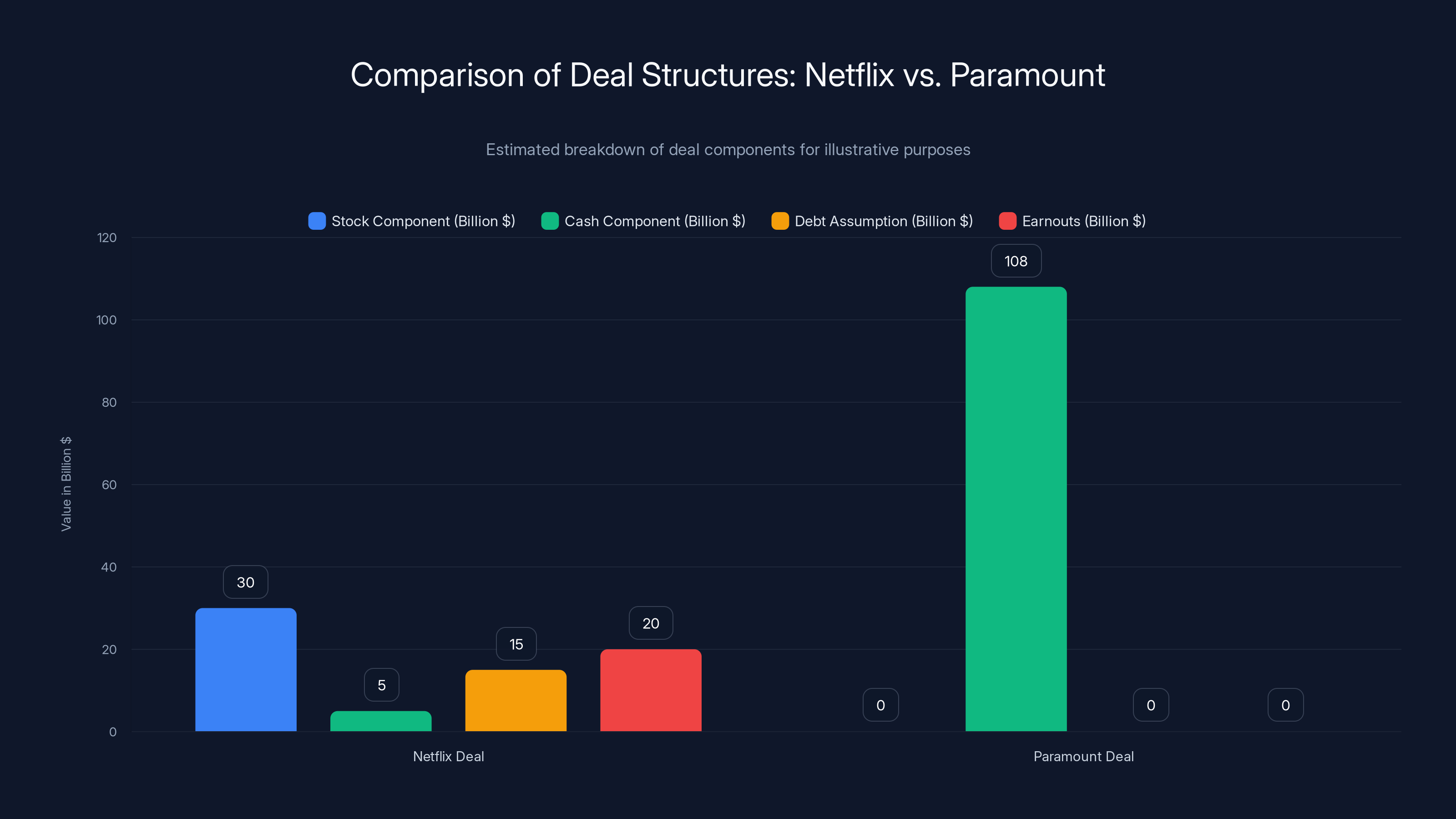

Estimated data shows Netflix's deal is more complex with stock, cash, debt, and earnouts, while Paramount offers a straightforward all-cash deal. Estimated data.

The Legal Weaponization of Shareholder Rights: Paramount's Lawsuit Strategy

This is where the lawsuit becomes brilliant strategically. Paramount isn't suing because it thinks it'll win a judgment. It's suing to force WBD to disclose the valuation methodology behind the Netflix deal.

Let me explain why that's devastating.

When a company's board recommends one deal over another, they need to show shareholders it's the best choice. But "best" is subjective. Different valuation methods produce different answers. The lawsuit essentially says: "Show us the math."

If WBD's valuation model has holes, Paramount can exploit them. If the board made assumptions that look questionable in hindsight, Paramount can argue they're mismanaging shareholder value.

This is corporate litigation as information warfare. Paramount is using shareholder disclosure rules as a crowbar to pry open the deal's assumptions.

The mechanics work like this:

- Court forces WBD to disclose deal documents, valuation analyses, and board meeting notes.

- Paramount reviews this material and identifies weaknesses in the valuation.

- Paramount uses these weaknesses in proxy materials and shareholder communications.

- Shareholders question whether the Netflix deal is really better.

- WBD's board faces pressure to reconsider or accept Paramount's bid.

It's a sophisticated play that doesn't require Paramount to win the lawsuit. It just requires disclosure.

CEO David Ellison's Nuclear Option: Board Nomination Strategy

Simultaneously with the lawsuit, Paramount CEO David Ellison announced plans to nominate a slate of directors to WBD's board.

This is the real power move. Here's why.

Under the Netflix deal documents, WBD presumably has contractual obligations to the deal. You don't just walk away from an $82.7 billion commitment because something better came along. There are break-up fees, legal consequences, reputational damage.

But if Paramount gets its nominees elected to the board, those directors can exercise whatever optionality exists within the Netflix agreement to "engage" with competing offers. Most mega-deals include some provision for this because absolute inflexibility looks bad to courts and regulators.

Ellison's statement was explicit: the new directors "will exercise WBD's right under the Netflix Agreement to engage on Paramount's offer and enter into a transaction with Paramount."

That's not subtle. He's saying we control enough board seats, we'll force engagement with our deal, and the Netflix contract allows it.

For this to work, Paramount needs to:

- Win enough shareholder votes at WBD's next annual meeting.

- Get directors elected who will prioritize Paramount's offer.

- Those directors must believe Paramount's 82.7 billion.

The problem? Convincing shareholders requires proving the Netflix deal is bad. And that requires discovering what Netflix actually paid for and how they valued it. Which brings us back to the lawsuit.

The Valuation Problem: Why 108.4B Isn't a Simple Comparison

Let's talk about the actual numbers, because they're more complicated than they look.

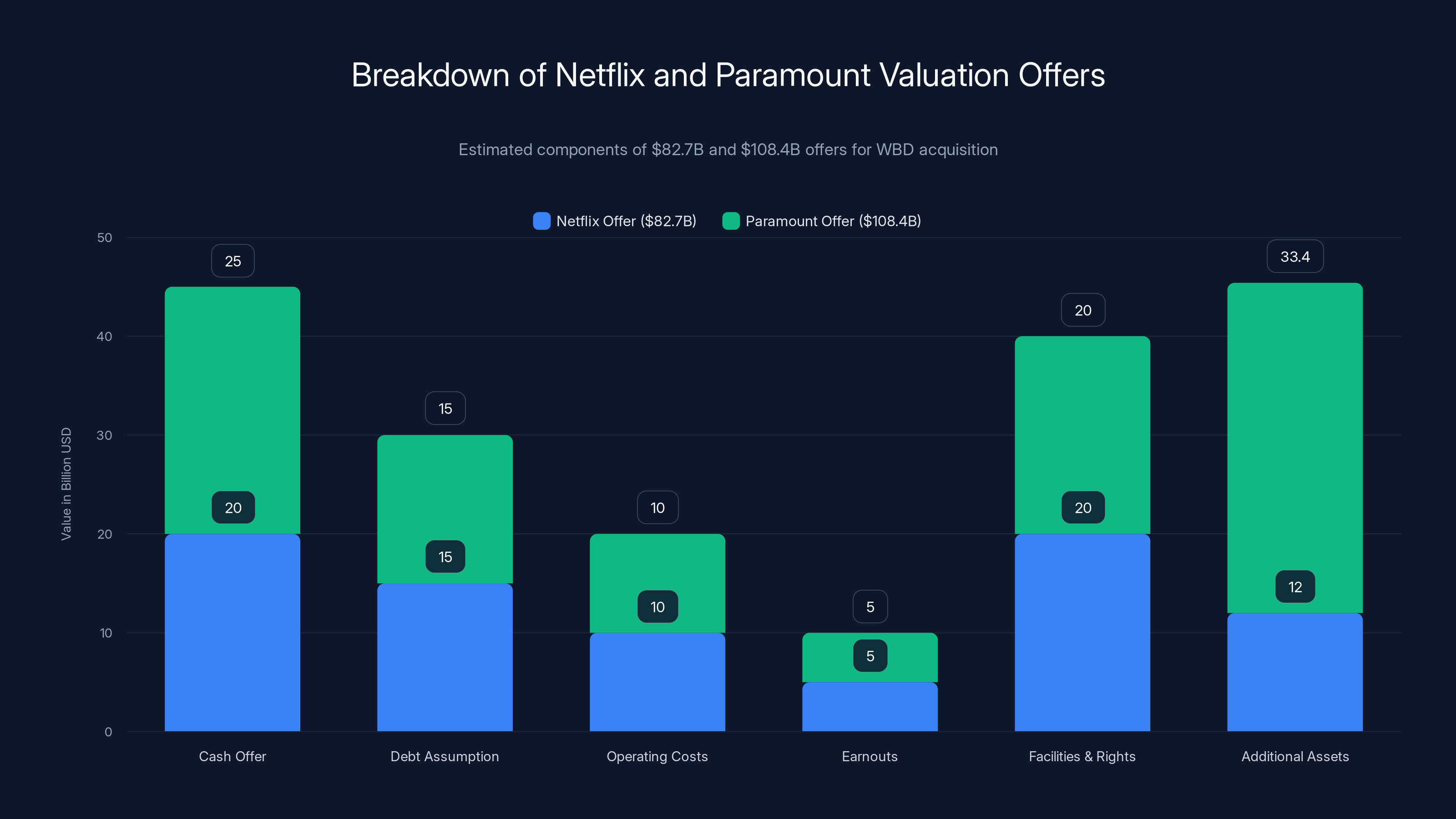

Netflix's $82.7 billion offer sounds specific, but it's not. That number likely includes multiple components:

- Cash for the studio

- Assumption of HBO/Max debt

- Ongoing operating costs for 12-24 months

- Possible earnouts based on subscriber retention

- Television and film production facilities

- Content library rights (complex to value)

Paramount's $108.4 billion bid is technically larger, but what's it actually buying? The entire WBD organization. That includes:

- Everything Netflix is buying

- Legacy television networks that are in decline

- Regional sports networks (which have complicated economics)

- International operations

- Corporate overhead

- Pension liabilities

- Ongoing litigation and regulatory exposure

When you account for the fact that Paramount is also inheriting a bunch of assets and liabilities Netflix wouldn't want, the per-asset value might be lower.

But shareholders don't necessarily understand this breakdown. They look at

If Netflix used aggressive assumptions about subscriber growth or content ROI, that becomes ammunition. If Netflix got a discount because they're assuming cost cuts WBD management didn't model, shareholders should know.

Paramount's offer of

Regulatory and Contractual Constraints: Why This Is Legally Messier Than It Looks

One reason WBD's board might have accepted the Netflix deal over Paramount's offer isn't purely financial. Regulatory approval is a massive factor.

A Paramount-WBD merger faces serious antitrust questions:

- Paramount owns CBS, which is a broadcast network.

- WBD owns HBO, which is a premium cable network.

- Combined, they'd have enormous influence over content distribution.

- The deal might trigger FTC review and potential conditions.

A Netflix-WBD deal is strategically different:

- Netflix is primarily a streaming platform, not traditional media.

- While Netflix has content production, the regulatory overlap is smaller.

- Regulators view this as a consolidation within streaming, not traditional media.

- Approval is likely faster and with fewer conditions.

Speaking of conditions, the Netflix deal probably includes contractual protections that WBD can't easily escape. These might include:

- Termination fees if a superior offer emerges.

- Exclusivity periods preventing other bidders.

- Walk-away costs if regulatory approval fails.

- Board composition requirements.

But here's the thing: almost all merger agreements include what's called a "fiduciary out" clause. This allows a company to break the deal if shareholders receive a materially better offer and the board determines it's their fiduciary duty to shareholders.

Paramount's lawsuit is essentially an attempt to prove that no such fiduciary duty exists because shareholders don't have enough information to judge whether Paramount's offer is actually superior.

The Streaming Wars Context: Why This Consolidation Matters

You can't understand this battle without understanding the streaming carnage of the past three years.

The streaming industry promised efficiency. One company could supposedly replace cable TV, broadcast TV, and premium movie studios all at once. Instead, what happened was:

- Netflix proved you could make money, but only by cutting costs ruthlessly.

- Disney+ spent billions and still lost money for years.

- Paramount+ lost a staggering amount while trying to compete.

- Peacock is still unprofitable.

- HBO Max required constant content spending to stay relevant.

The math became clear: you need either massive scale (Netflix) or deep pockets from other businesses (Disney) to survive streaming. Everyone else is drowning.

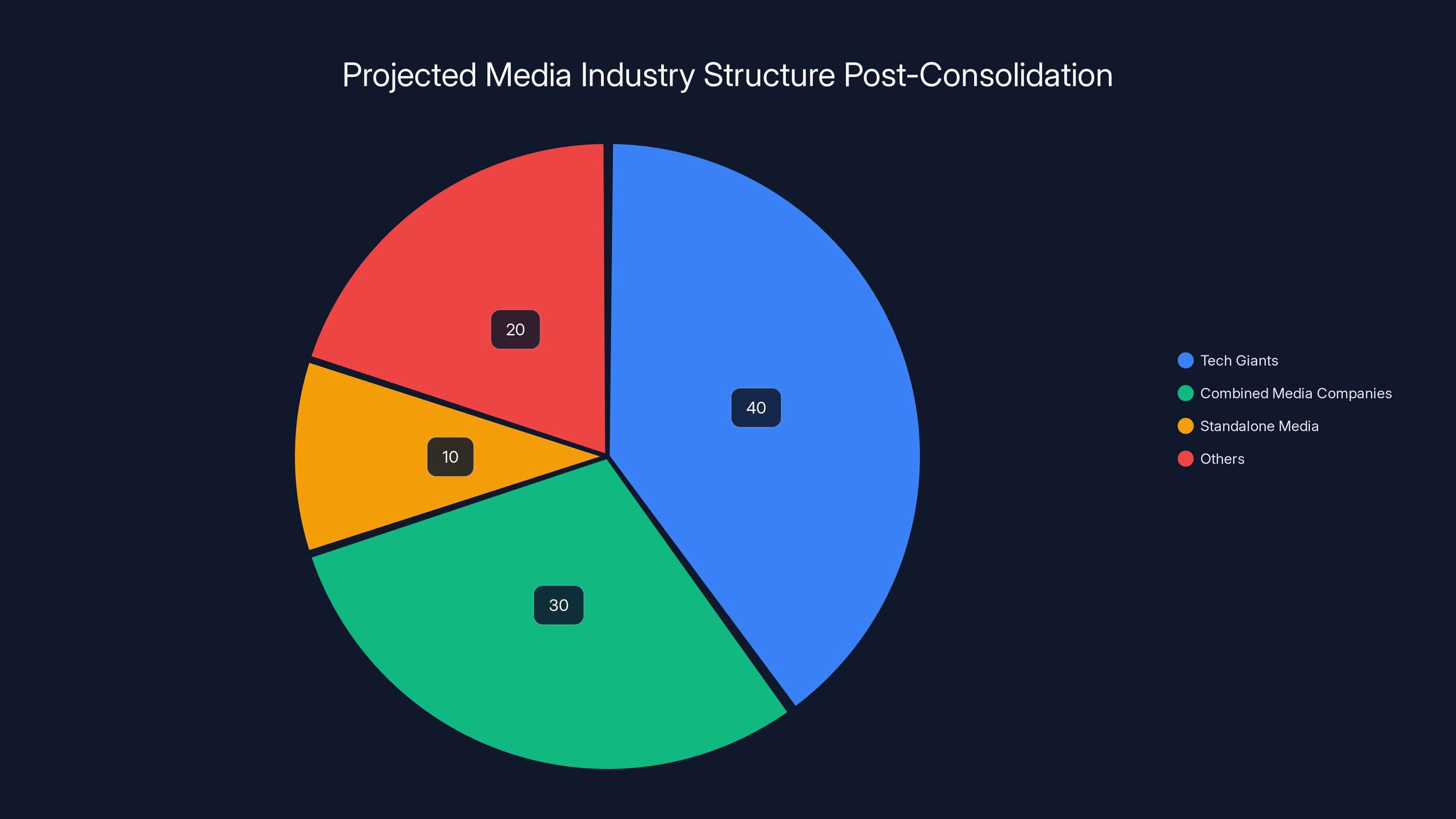

This is why consolidation became inevitable:

Traditional media companies couldn't compete on economics, so they had to combine to create countervailing power against Netflix and the tech giants. A single streamer can't negotiate favourable terms with theatrical exhibitors, cable operators, or international distributors. But a combined entity with multiple properties can.

The Netflix-WBD deal represents Netflix absorbing traditional media assets to strengthen its moat. Paramount's offer is a desperate attempt to prevent that outcome by combining with the one other major content player.

If Netflix gets WBD's assets, it becomes even more dominant. If Paramount succeeds, it creates a real alternative with comparable content libraries. The stakes are the industry structure itself.

Shareholder Dynamics: Who Actually Decides These Battles

Let's be clear about something: WBD's board doesn't ultimately control this situation. Shareholders do.

WBD's ownership is distributed among institutional investors, hedge funds, individual shareholders, and management. The institutional investors (huge pension funds, mutual fund companies, index funds) hold the real power because they control millions of shares.

These investors care about one thing: return on investment. If Paramount can convince them that an

But here's where the lawsuit becomes crucial. Most shareholders don't have the expertise to independently evaluate complex M&A transactions. They rely on proxy materials, media coverage, and statements from parties they trust. Paramount's lawsuit forces disclosure that makes Paramount's position stronger by raising questions about the Netflix valuation.

Institutional investors ask themselves:

- Do I trust the board's valuation assumptions about Netflix?

- Has this board adequately explored alternatives?

- Is my money better in a Netflix-dependent play or a combined media company?

- What's the risk of this deal breaking apart?

Paramount's strategy is to make enough noise and force enough disclosure that the answer to those questions becomes "I don't know, and I need more information."

Engaging with Paramount is estimated to be the most effective strategy with moderate risk, while going quiet is seen as least effective and highly risky. Estimated data.

The Netflix Merger Agreement Analysis: What We Know About the Terms

While the lawsuit will force fuller disclosure, we can infer some things about how the Netflix-WBD deal is structured.

Mega-deals typically include several protections for the buyer:

Termination Rights: If WBD terminates to accept a superior offer, Netflix receives a "termination fee." This is typically 3-4% of deal value, so roughly $2.5-3.3 billion.

Exclusivity Periods: For some duration, WBD probably can't actively shop itself or negotiate with other bidders. But most agreements allow the board to respond to "unsolicited superior proposals" if the board determines it's their fiduciary duty.

Conditions Precedent: Regulatory approval is likely a condition. If the FTC blocks the deal, both parties walk away without penalty (or with limited penalties).

Representation Warranties: WBD represents that it owns what it claims to own, no hidden litigation exists, contracts are valid, etc. Breaches could trigger damages.

The key question is how much flexibility exists within the agreement for WBD to engage with a superior offer. If Paramount proves the Netflix valuation is flawed, does that count as grounds for invoking the fiduciary out clause?

Probably yes, assuming Paramount's offer is clearly superior and the board genuinely believes it's better for shareholders. But "clearly superior" requires proof, which is why forced disclosure matters so much.

Media Industry Consolidation Precedent: What History Tells Us

This battle isn't unique. The media industry has a long history of attempted consolidations, some successful and others blocked.

Comcast and Time Warner (2014): Comcast attempted to buy Time Warner Cable for $45 billion. The deal faced massive regulatory opposition from consumer advocates who feared reduced competition in broadband. Comcast ultimately withdrew the bid.

T-Mobile and Sprint (2020): These companies merged into a stronger competitor, but the deal took two years for regulatory approval and included conditions around job protection and network expansion.

Disney and Fox (2019): Disney acquired most of Fox's entertainment assets for $71 billion after Rupert Murdoch's company struggled with cord-cutting.

The lesson from these precedents: antitrust concerns often dominate the outcome more than financial valuations. A deal that's financially superior might still be blocked if regulators believe it reduces competition.

For Paramount's bid, this means winning isn't just about convincing shareholders. The FTC would need to clear a Paramount-WBD combination, which is uncertain.

For Netflix's bid, regulators might have fewer concerns since Netflix isn't traditional media in the same way.

The Board's Dilemma: Defending Against Activists While Managing Deal Risk

Put yourself in the shoes of WBD's board for a moment.

You accepted a deal you believe is best. You've told shareholders and the market that Netflix is the path forward. You've probably already begun integrating systems, preparing content strategies, and planning post-deal organization.

Then Paramount launches a lawsuit that forces you to defend your valuation assumptions. You have to disclose internal documents that might show uncertainty or debate about whether Netflix was the right choice.

Simultaneously, Paramount is running a proxy fight to replace you with directors who will kill your deal.

Your options suck:

-

Defend aggressively: Sue Paramount back, arguing they're harassing you. But this looks defensive and makes you look uncertain about Netflix.

-

Go quiet: Let the lawsuit proceed without comment. But shareholders interpret silence as weakness.

-

Negotiate a settlement: Maybe work out a deal where Paramount gets some consideration to walk away. But this looks like admitting the Netflix deal isn't as strong.

-

Engage with Paramount: Explore whether Paramount's offer really is superior. But this might trigger Netflix to assert termination rights or attempt to renegotiate.

What you almost certainly can't do is ignore the lawsuit and hope shareholders don't care. Activist campaigns almost always succeed in getting some directors elected if they achieve 20%+ shareholder support.

Paramount's $108.4 billion bid for WBD was a strategic move to consolidate and compete with larger players like Netflix and Disney. Estimated data for competitor valuations.

Financial Engineering and Deal Structure: The Math Behind the Numbers

Let's dig into how these deals are actually structured, because the stated values hide complexity.

The Netflix Deal Likely Includes:

- Stock-based consideration: Netflix shares given to WBD shareholders.

- Cash component: Some amount of cash for tax and legal reasons.

- Debt assumption: Netflix assumes WBD's debt, reducing cash payment needed.

- Earnout provisions: If subscriber metrics hit targets, additional payments.

- Equity rollover: Maybe some WBD management gets Netflix equity stakes.

All of these change the effective value. If

Paramount's All-Cash Offer sounds clean by comparison. But all-cash deals have complications:

- Where does Paramount get $108 billion? Debt markets, asset sales, or financing from investors.

- If financed with debt, Paramount inherits massive interest costs.

- All-cash is taxable to shareholders, while stock deals can be structured as tax-deferred.

- Paramount might not have debt capacity for this amount given its existing liabilities.

Savvy shareholders understand that

Possible Outcomes and Scenarios: Where This Goes From Here

Let's game out the possible endings to this saga.

Scenario 1: Netflix Deal Completes As Planned

This happens if Paramount fails to get board seats elected and shareholders vote to accept Netflix. Regulatory approval comes through. Netflix absorbs HBO, Max, and WBD's studio. Outcome: Netflix becomes near-monopolistic in premium streaming content, competitors further weakened.

Scenario 2: Paramount Successfully Replaces Board

Paramount wins enough shareholder votes to elect directors. The new board invokes the fiduciary out in the Netflix agreement, terminates the deal (triggering termination fees and potential litigation from Netflix), and accepts Paramount's offer. Outcome: Media consolidation, creation of a Netflix alternative, antitrust questions about combined entity.

Scenario 3: Negotiated Settlement

Paramount and WBD negotiate. Maybe Paramount gets a seat at the table post-deal, or agrees to drop its bid in exchange for some consideration. The Netflix deal modifies slightly and completes. Outcome: Messy, unclear resolution that keeps uncertainty alive longer.

Scenario 4: Third-Party Bidder Emerges

The lawsuit and proxy fight attract another bidder (maybe Apple, Amazon, or Skyworks AI looking to enter media). A bidding war breaks out. WBD either gets a higher offer or shareholders choose between three or four options. Outcome: Least likely, but would maximize shareholder value.

Most likely? Scenario 1, with meaningful risk of Scenario 2. The Netflix deal is too far advanced and too politically palatable to regulators to be easily stopped. But Paramount will drag things out long enough to cause real uncertainty.

Strategic Implications: What This Tells Us About Media's Future

Whatever the outcome, this battle reveals fundamental truths about the media industry now.

First truth: Scale is everything. Small media companies can't compete with Netflix or the tech giants. They need to combine or get absorbed. There is no middle ground.

Second truth: Streaming economics are worse than predicted. The industry can't sustain five or six competing platforms all spending billions annually. Consolidation is inevitable.

Third truth: Traditional media companies can only survive by combining with each other or getting acquired by tech giants. Standalone media is probably dead as a business model.

Fourth truth: Shareholder activism works. Paramount's lawsuit and proxy fight prove that determined management can force changes even when dealing with existing commitments.

For content creators, this matters because it determines which platforms survive. If Netflix absorbs WBD, it has even more power to dictate terms. If Paramount wins, a real alternative emerges but with different cost pressures.

For consumers, consolidation could mean fewer platforms to subscribe to (good) but less competition on price and features (bad). The industry structure that emerges from this battle will determine content quality, pricing, and innovation for years.

Estimated data suggests tech giants and combined media companies will dominate the market, with standalone media holding a minor share. Consolidation is key to survival.

The Role of Legal Infrastructure: How Securities Law Weaponized Disclosure

One thing that makes this battle so vicious is America's securities law framework.

Under SEC regulations, public companies must disclose material information to shareholders. A merger's terms, valuation methodology, and board deliberation are all discoverable. Paramount's lawsuit is essentially a mechanism to force disclosure that WBD would prefer to keep confidential.

This creates an asymmetry. Paramount can argue whatever it wants about why its deal is better. But WBD has legal obligations to disclose facts that might undermine its own deal.

It's not unique to this situation. This pattern repeats in M&A battles across industries. The party trying to block or undo a deal uses shareholder litigation to force disclosure that supports their position.

What Paramount Gets If It Loses: The Cost of This Battle

Let's not ignore what Paramount loses by pursuing this aggressively.

First, litigation costs. High-stakes M&A litigation costs tens of millions in legal fees. Paramount is burning through investor capital to fight a battle it might lose.

Second, opportunity cost. Paramount management is focused on this acquisition battle while the core business deteriorates. Paramount+ still loses subscribers. Cable networks still decline. Without management attention, things get worse.

Third, market signal. Launching a hostile bid and then suing signals desperation. It tells the market "we're cornered and willing to take big swings." That affects Paramount's ability to raise capital, attract talent, and maintain customer confidence.

Fourth, if Paramount does win, integration with WBD is incredibly messy. Two cultures, overlapping businesses, duplicate infrastructure. Paramount might win the deal only to lose value in the integration.

Yet Paramount does it anyway. Because the alternative—standing still while Netflix absorbs a major competitor and strengthens its moat—is worse.

International Implications and Global Media Consolidation

This battle has implications beyond America.

WBD operates globally. HBO is recognized in nearly every country. The studio produces content watched worldwide. Whoever acquires these assets gains global media reach.

If Netflix wins, it gains HBO's international distribution infrastructure and local production capabilities in dozens of countries. Netflix becomes even more dominant globally.

Regulators in Europe, the UK, and other markets have different thresholds for approving media consolidation. Netflix's deal might face more regulatory scrutiny internationally than in America. Paramount's offer might be viewed more favorably as it preserves a competing media company.

This affects which deal ultimately gets approved, because international regulatory approval is a condition for completion.

Technology's Role: How AI and Automation Will Reshape What Matters

Here's something nobody talks about: AI is about to obliterate the economics of both these deals.

Content production will get cheaper and faster as AI video generation, scriptwriting, and editing improve. Netflix is betting $82.7 billion on HBO's studio infrastructure and content library. But in five years, AI might make human-written, human-filmed content less valuable if AI-generated content gets good enough for certain genres.

Similarly, personalization and recommendation get better with AI. Netflix might not need HBO's talent pool. It might just need the content library for training AI models.

The irony is that both Paramount and Netflix are fighting over assets and capabilities that might become less relevant in the next decade. They're fighting yesterday's battle while technology reshapes the terrain.

Why Shareholders Matter More Than You Think in These Battles

Let's be crystal clear: shareholder votes determine these outcomes, not board recommendations.

The board says "we recommend Netflix." Shareholders might say "actually, we like Paramount's offer better." If shareholders are convinced, they vote out board members and replace them with directors who favor Paramount's deal.

This forces companies to compete not just on the quality of their offers but on their ability to convince shareholders. Paramount's lawsuit is a shareholder messaging tool. Force disclosure, raise questions about Netflix's valuation, convince shareholders that Paramount's offer is better, win board seats.

Who controls shareholders? Institutional investors—the massive mutual funds, pension funds, and hedge funds that own huge blocks of stock. If Paramount convinces Vanguard, Black Rock, and State Street that its deal is better, it wins. These firms control trillions in assets and can swing shareholder votes.

This is why Paramount's litigation and proxy strategy focus on forcing disclosure. The goal is to give institutional investors ammunition to question the board's recommendation.

The Netflix Countermove: What Netflix Might Do To Protect The Deal

Netflix isn't sitting passive in this fight.

Expect Netflix to defend the deal aggressively:

- Investor relations: Netflix executives explaining to institutional investors why the deal is transformative.

- Media campaign: Public statements about Netflix's vision and commitment to HBO's brands.

- Shareholder communications: Counter-messaging to Paramount's claims.

- Financial incentives: Maybe increasing the offer price or adjusting terms to make the deal more attractive.

- Deal acceleration: Move toward closing faster to create momentum and lock in approval.

Netflix might also use the lawsuit to its advantage. As WBD is forced to disclose information about the deal, that information becomes public. Netflix can use disclosed valuations and assumptions in its own shareholder communications, demonstrating why its deal is compelling.

Post-Deal World: What Happens to Content, Streaming, and Competition

Whatever the outcome, the post-deal media landscape will look radically different.

If Netflix wins: One company controls Netflix platform plus HBO, HBO Max, HBO's international distribution, the Warner Bros. studio, and DC Comics properties. Netflix becomes so dominant that regulators might later force divestiture of certain properties. Competitors are left scrambling. Paramount remains independent but weakened. Disney+ fights for #2 position.

If Paramount wins: Paramount acquires all of WBD, creating a media company that owns broadcast, cable, streaming, studios, and extensive content libraries. The combined entity is still smaller than Netflix but has real competitive leverage. Netflix remains dominant but doesn't absorb HBO's assets.

Either way, consolidation happens. Small competitors get squeezed. Content spending becomes focused on the two or three platforms with sufficient scale.

How This Relates to Broader Tech Consolidation Trends

This battle isn't unique to media. It reflects a broader pattern in tech and consumer businesses: consolidation accelerating because smaller players can't compete.

Look at SaaS: independent tools get rolled into platforms. Fintech startups get acquired by banks. Cloud providers consolidate. Every industry is consolidating because efficiency demands scale.

Media is just more visible because it's public, high-profile, and affects consumer culture. But the dynamic is the same. Smaller players can't sustain standalone businesses, so they consolidate or get acquired.

This has policy implications. Antitrust regulators are increasingly concerned about consolidation reducing competition. The Paramount vs. WBD vs. Netflix battle will set precedent for what's allowed in media consolidation.

A Paramount-WBD merger might get blocked on antitrust grounds. A Netflix-WBD merger might be approved because Netflix isn't traditional media. That shapes which outcome becomes reality.

FAQ

What is Paramount's lawsuit actually about?

Paramount is suing to force Warner Bros. Discovery to disclose detailed information about its Netflix merger agreement, including how Netflix valued the transaction and what assumptions it made about future performance. The lawsuit argues that WBD shareholders deserve transparent information to judge whether Netflix's

Why would WBD shareholders choose Paramount's offer over Netflix's?

Shareholders might prefer Paramount's offer if they believe the Netflix deal fundamentally overvalues the streaming business or undervalues WBD's assets. Paramount is offering

What are termination fees and why do they matter?

Termination fees are payments one party makes if they back out of a merger agreement. If WBD terminates the Netflix deal to accept Paramount's offer, WBD must pay Netflix a break-up fee, typically 3-4% of the deal value. For this deal, that's roughly $2.5-3.3 billion. This fee makes it expensive for WBD to switch horses. However, fiduciary out clauses in merger agreements allow companies to break deals if the board determines a superior offer is available. Whether Paramount's offer qualifies depends partly on forced disclosure from the lawsuit, as WBD's board must prove Netflix's deal wasn't clearly better.

How does the board election strategy strengthen Paramount's position?

If Paramount successfully nominates and gets directors elected to WBD's board, those new directors can reinterpret the company's obligations under the Netflix agreement and potentially invoke flexibility provisions to engage with Paramount's bid. Board control is often more valuable than shareholder votes because directors set agendas, negotiate terms, and interpret contracts. Paramount is trying to gain control of the board so it can pressure management to negotiate with Paramount, potentially renegotiate with Netflix, or ultimately accept Paramount's offer instead.

What role do institutional investors play in determining the outcome?

Institutional investors like Vanguard, Black Rock, and pension funds control the majority of WBD shares. These investors determine shareholder votes. If Paramount convinces them that Netflix's deal is questionable and Paramount's offer is better, they vote to elect Paramount's board nominees. If they believe the board's recommendation to accept Netflix is sound, they block Paramount's slate. Paramount's lawsuit and shareholder communications are designed to convince these institutional investors to switch their votes.

What happens if Netflix terminates the deal due to Paramount's actions?

If WBD accepts Paramount's offer or Netflix decides the deal is unlikely to close due to uncertainty from the lawsuit, Netflix could terminate the agreement. Netflix would presumably receive the same termination fee ($2.5-3.3 billion) that WBD would pay if WBD walked away. Alternatively, Netflix might renegotiate terms to account for the risk created by Paramount's challenge. The lawsuit creates deal risk that might force Netflix to reprice or restructure the agreement to protect itself.

How would antitrust regulators view these different combinations?

A Netflix-WBD combination faces fewer antitrust concerns because Netflix isn't traditional media. The combination is seen as consolidation within streaming, which faces less regulatory scrutiny. A Paramount-WBD combination would likely trigger FTC review because it combines two major traditional media companies and could reduce competition in content distribution. FTC approval for Paramount-WBD would require concessions or divestitures.

Why is financial modeling and valuation so important in this battle?

When a company's board recommends accepting one deal over another, they must justify that decision to shareholders based on financial analysis. If Netflix's valuation model uses aggressive assumptions about subscriber growth, content ROI, or cost reductions, that creates vulnerability. Paramount's lawsuit forces disclosure of those assumptions. If the assumptions look questionable or if Netflix's valuation is based on information asymmetry (Netflix knows things about streaming economics that WBD doesn't), shareholders might conclude Paramount's $108.4 billion offer is superior. The lawsuit is essentially about deconstructing Netflix's financial model to expose weaknesses.

What's the historical precedent for hostile bids in media consolidation?

Media consolidation has a long history of hostile offers and proxy fights. Rupert Murdoch built News Corp partly through hostile acquisitions. Carl Icahn has made multiple hostile bids in media. What's changed is that modern shareholder activism is more sophisticated, using litigation as a disclosure weapon rather than pure voting power. The Paramount strategy reflects this evolution: force disclosure, use the disclosed information to convince shareholders, win the vote.

Conclusion: Why This Battle Matters Beyond Corporate Finance

On the surface, this is corporate litigation between giant media companies. In reality, it's about the future structure of the entertainment industry and what content you'll have access to in five years.

If Netflix wins, one company becomes even more dominant. You get better content recommendations but less competitive pressure on pricing and fewer alternative platforms. If Paramount wins, you get a meaningful competitor to Netflix but with higher cost structures and less efficient operations.

Neither outcome is perfect. But the battle itself reveals truths about media economics, shareholder power, and corporate strategy that matter far beyond the specific companies involved.

Streaming was supposed to be better than cable. It was supposed to lower costs, improve selection, and empower creators. Instead, it's followed the same consolidation pattern as every other industry. Scale wins. Smaller players die or get absorbed. Competition gets worse as the field narrows.

The lawsuit won't change that trajectory. But it will determine whether one company becomes near-monopolistic or whether a credible alternative survives. That's worth paying attention to, even if corporate M&A litigation isn't normally your thing.

One more thing: watch what happens with disclosure. The forced disclosure in this lawsuit will reveal how these companies value content, calculate subscriber lifetime value, and model profitability. That information, now public, will shape how every other media company is valued for years to come. Paramount's lawsuit is a very expensive way to get competitive intelligence, but it might work anyway.

Key Takeaways

- Paramount's lawsuit forces disclosure of Netflix's valuation methodology, transforming the lawsuit into information warfare.

- Board control through director nominations is Paramount's actual goal, more valuable than any single shareholder vote.

- Streaming economics are fundamentally broken, making consolidation inevitable across the industry.

- Institutional investors like Vanguard and BlackRock determine outcomes more than board recommendations.

- Whichever company wins, Netflix becomes either monopolistic or faces a weakened competitor, both reducing industry competition.

![Paramount vs Warner Bros Discovery: Netflix Merger Battle [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/paramount-vs-warner-bros-discovery-netflix-merger-battle-202/image-1-1768239667857.jpg)