Warner Bros. Discovery Rejects Paramount's $108.4B Bid Over Debt Crisis [2025]

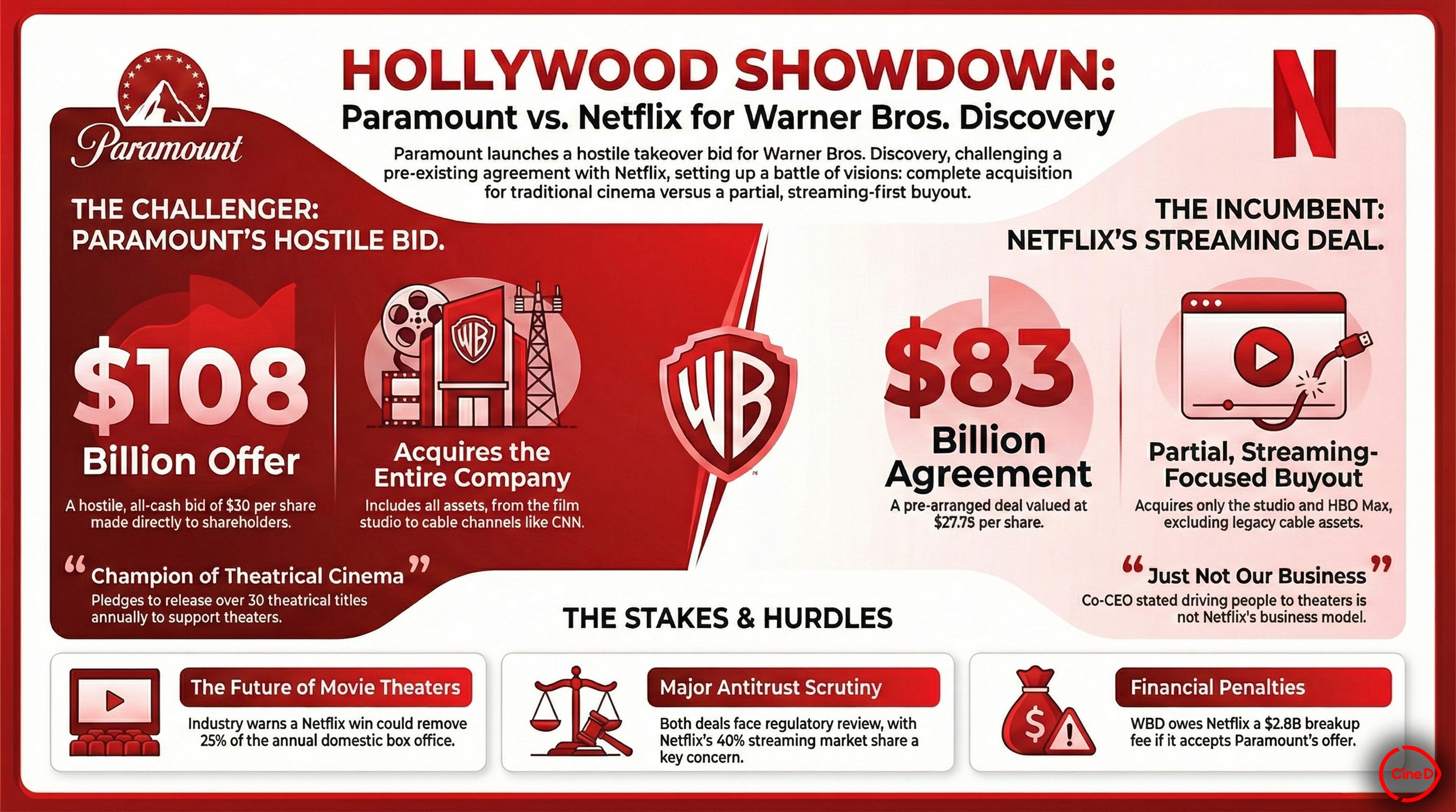

The entertainment industry's most dramatic acquisition saga just hit another turning point. On Wednesday, Warner Bros. Discovery's board unanimously rejected Paramount Skydance's revised $108.4 billion acquisition bid, calling it fundamentally unviable due to the staggering debt load it would require.

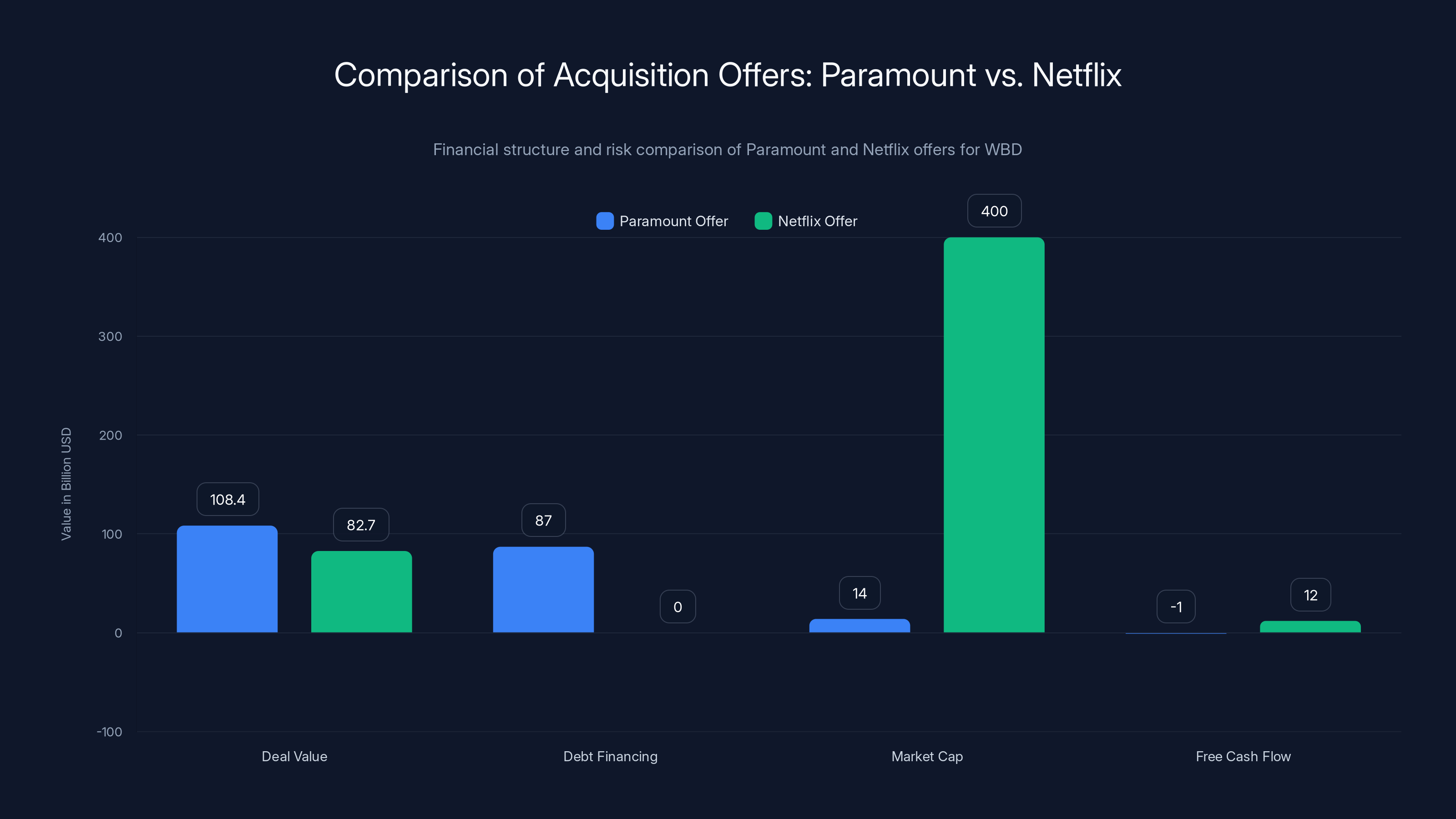

Here's what makes this moment so pivotal: Paramount is trying to acquire a company nearly seven times its own market capitalization using almost $87 billion in borrowed money. That's not just aggressive. That's structural financial suicide according to WBD's board.

This rejection marks the second time WBD has turned down Paramount's advances in just weeks. The first offer of

Instead, WBD is doubling down on its earlier agreement with Netflix, a company worth roughly

What's happening here tells a much bigger story about modern media mergers, debt financing, and how financial engineering can be a deal killer even when the price looks attractive on the surface. Let's unpack why WBD rejected this offer and what it means for the future of media consolidation.

TL; DR

- Board Unanimously Rejected: WBD's board rejected Paramount Skydance's revised $108.4 billion bid, the second rejection in weeks

- Debt Burden Too High: Paramount would need to borrow approximately $87 billion, nearly 7 times its own market capitalization

- Netflix Deal Preferred: WBD recommends the Netflix merger with an $82.7 billion all-stock deal, citing Netflix's stronger financial position

- Credit Rating Risk: Worsening Paramount's junk-status credit rating creates material risk of deal failure and operational damage

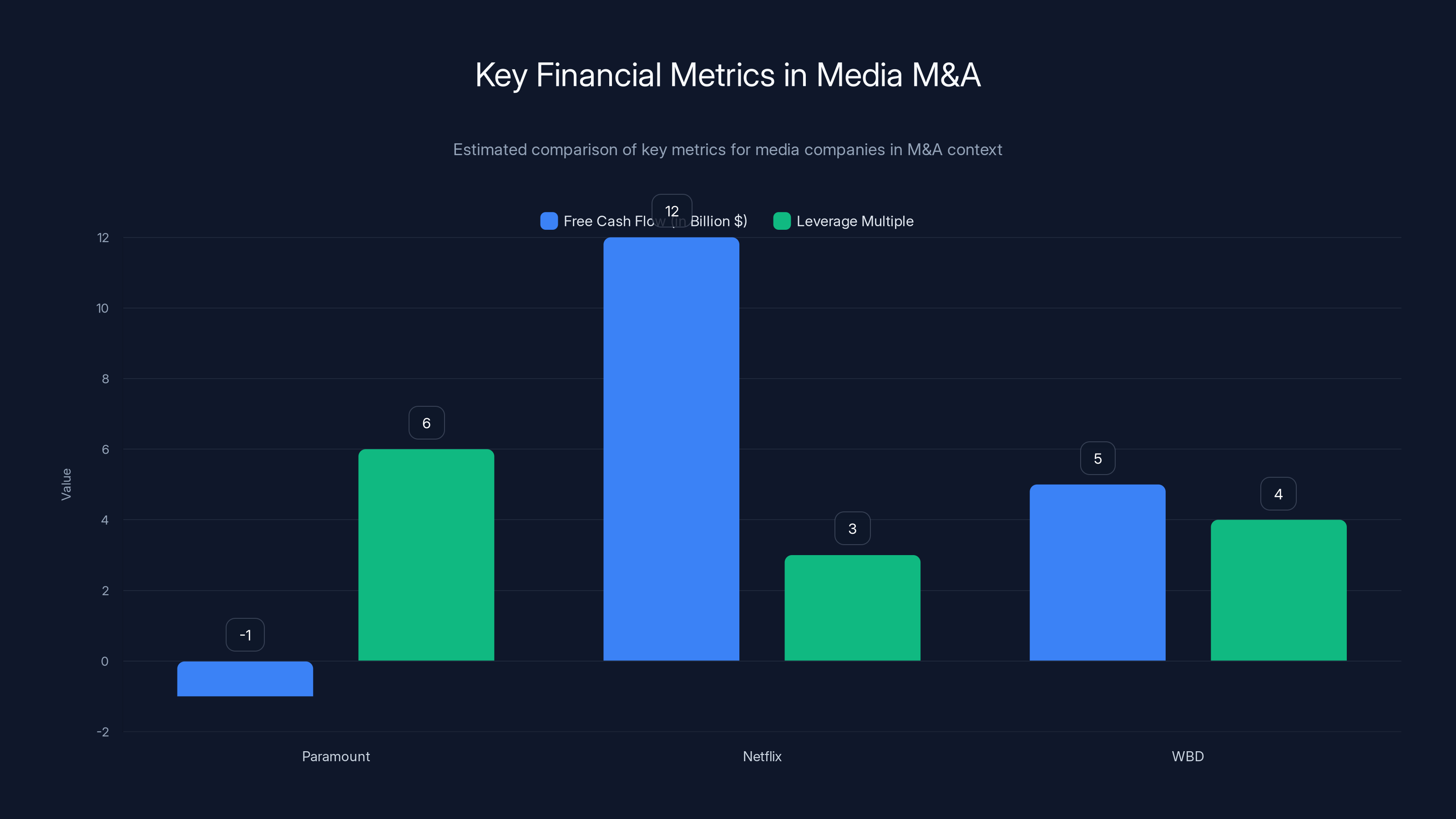

- Free Cash Flow Matters: Netflix has estimated $12 billion free cash flow for 2026; Paramount has negative free cash flow that would worsen post-acquisition

Paramount's acquisition attempt with a 7X leverage multiple is significantly higher than typical scenarios, indicating high risk. Estimated data based on typical industry values.

The Failed Bid: Understanding the $108.4 Billion Offer

Paramount Global's revised bid wasn't a casual offer thrown at WBD's board. It was a carefully structured proposal designed to address the primary criticism of the first bid: cash availability.

When Paramount first approached WBD shareholders directly in early December with $30 per share, WBD dismissed it as lacking credible funding. The company needed proof. So Paramount went back to work, this time assembling what looked like a fortress of financial commitments.

Larry Ellison, Oracle's legendary co-founder and one of the world's wealthiest individuals, personally guaranteed

The offer price of

But WBD's board looked past the surface-level numbers and into the structural mechanics of the deal. What they saw alarmed them enough to unanimously reject it.

The fundamental problem wasn't the guarantee or even the price. It was the leverage structure itself. Paramount would be financing approximately

In the context of leveraged finance, deals exceeding 4 to 5 times a company's market cap start looking extremely risky, especially in mature industries like entertainment where margins are compressed and cash flows are volatile.

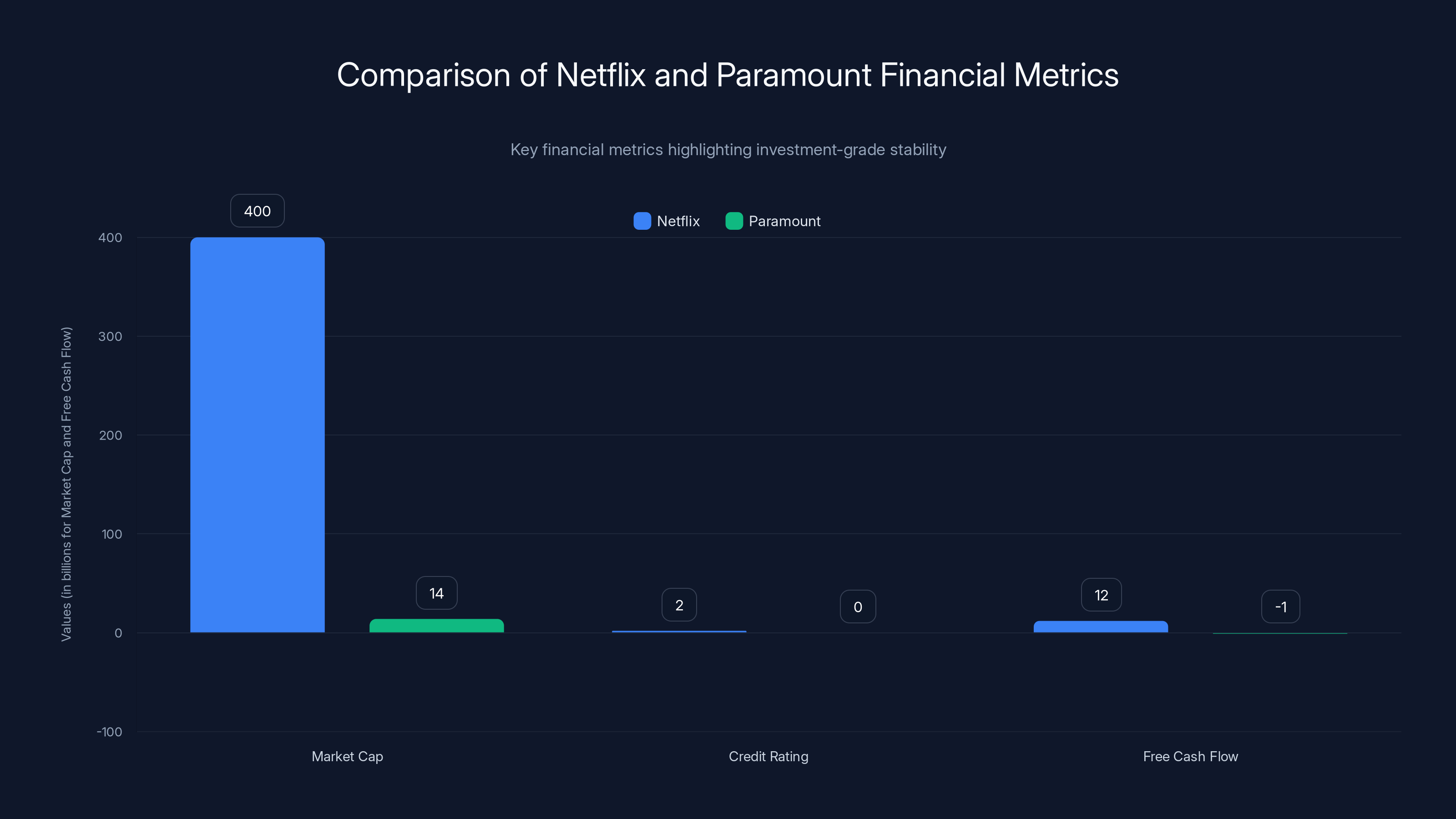

Estimated data shows Netflix's strong free cash flow and lower leverage multiple compared to Paramount, highlighting key financial metrics that influence M&A decisions.

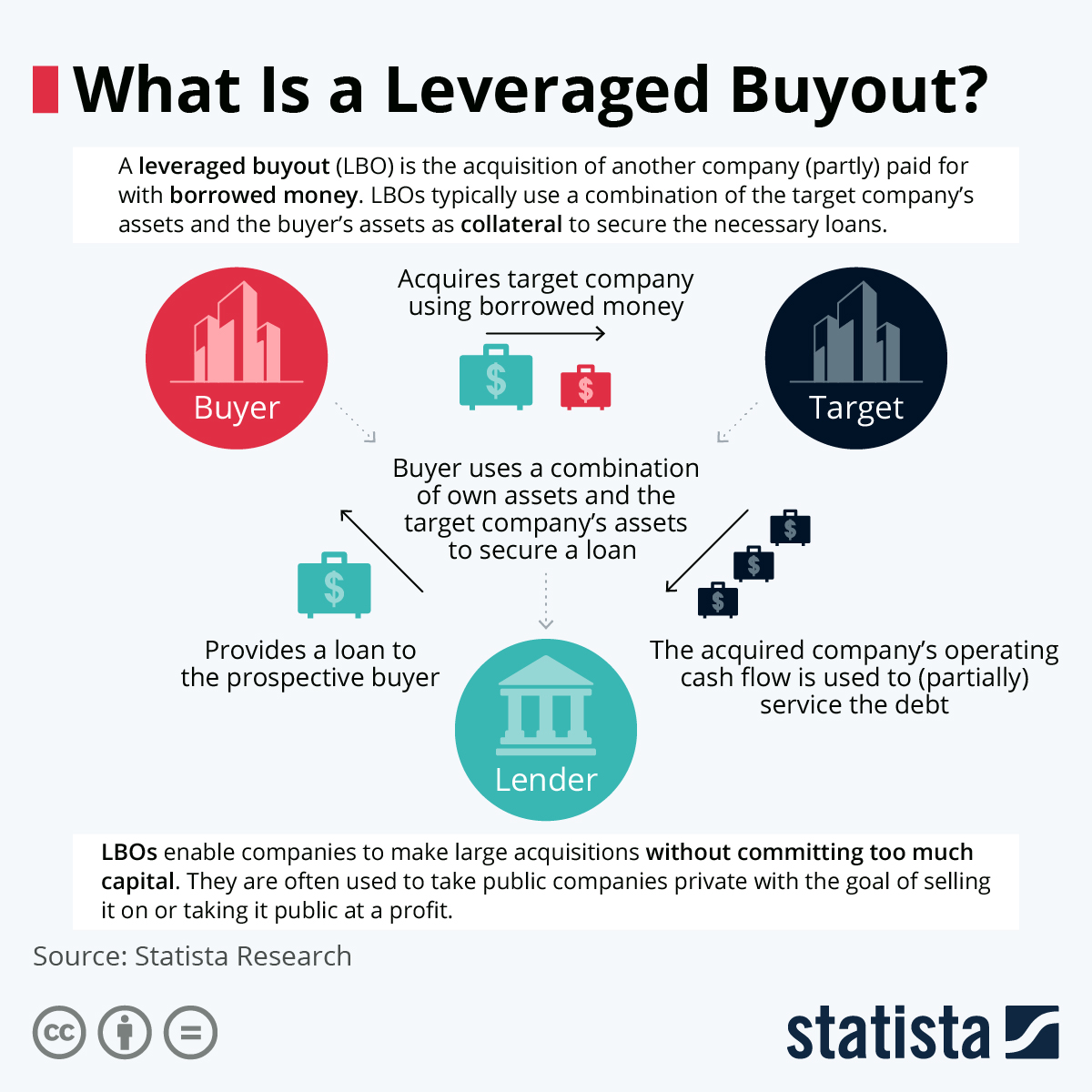

Why WBD Called It a "Leveraged Buyout" and What That Really Means

WBD's use of the term "leveraged buyout" wasn't just rhetorical. It was a precise technical characterization with serious implications.

In finance, a leveraged buyout is a specific structure: the acquirer borrows the majority of purchase price using the target's assets and cash flows as the primary collateral, betting that operational improvements and cash generation will service the debt. It's how private equity firms have historically financed acquisitions. It's not inherently wrong. But it's inherently risky for shareholders and debt holders.

Paramount's deal structure matched that template almost perfectly. The bulk of the capital was borrowed money. The expectation was that WBD's cash flows (from Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, DC Comics, and other properties) would be used to pay down that debt over time.

Here's why that structure terrifies a company's board: entertainment is cyclical. A franchise that's profitable today might crater tomorrow. Content licensing deals expire. Streaming subscriber growth plateaus. Production costs spike. The same assets that justify $87 billion in debt during boom times can become anchors during downturns.

WBD's board was essentially saying: we're not comfortable betting the company's long-term viability on Paramount's ability to manage this debt load through multiple industry cycles. The margin for error is too thin.

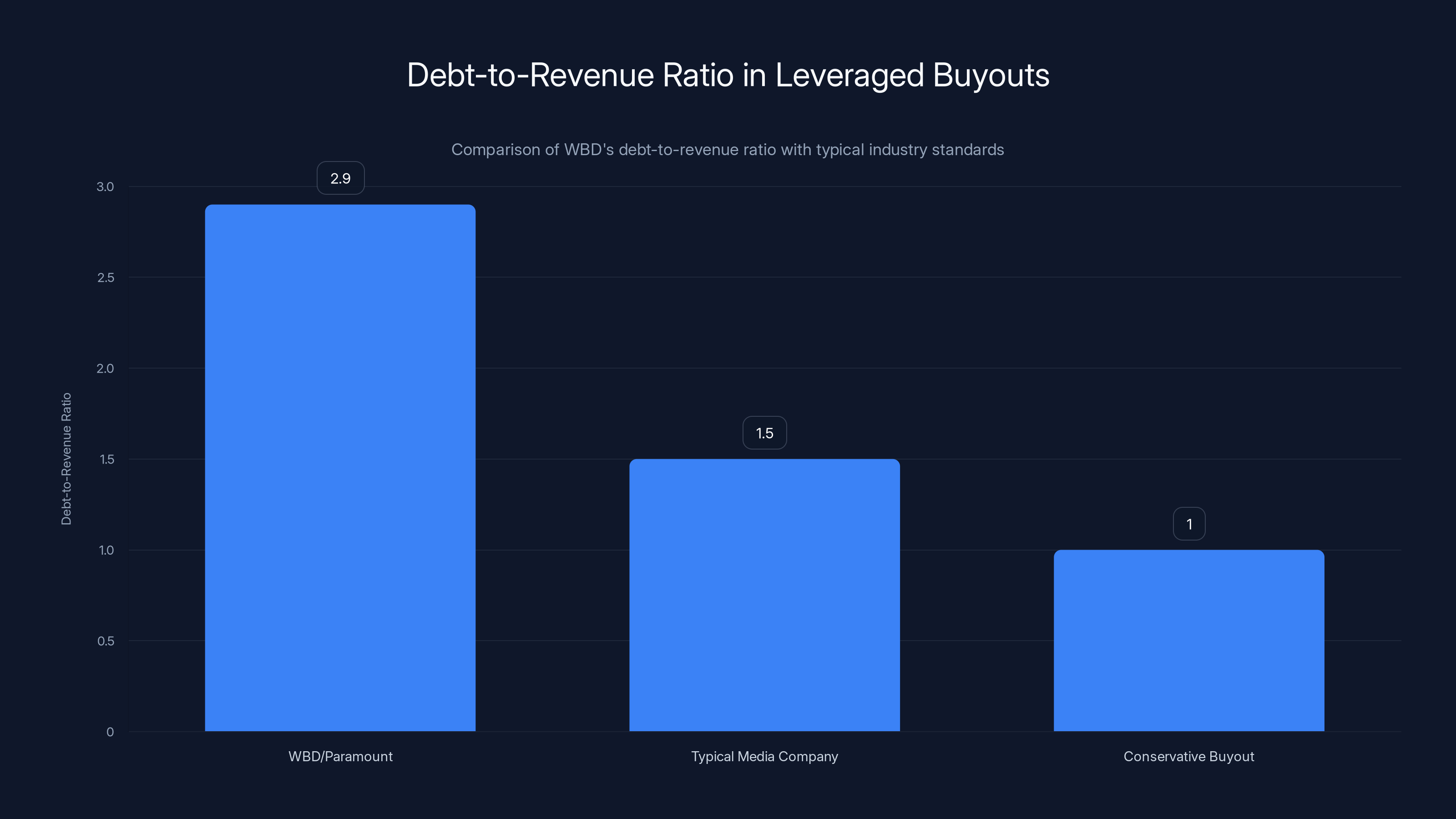

Consider the numbers from another angle. The

The Credit Rating Problem Nobody's Talking About

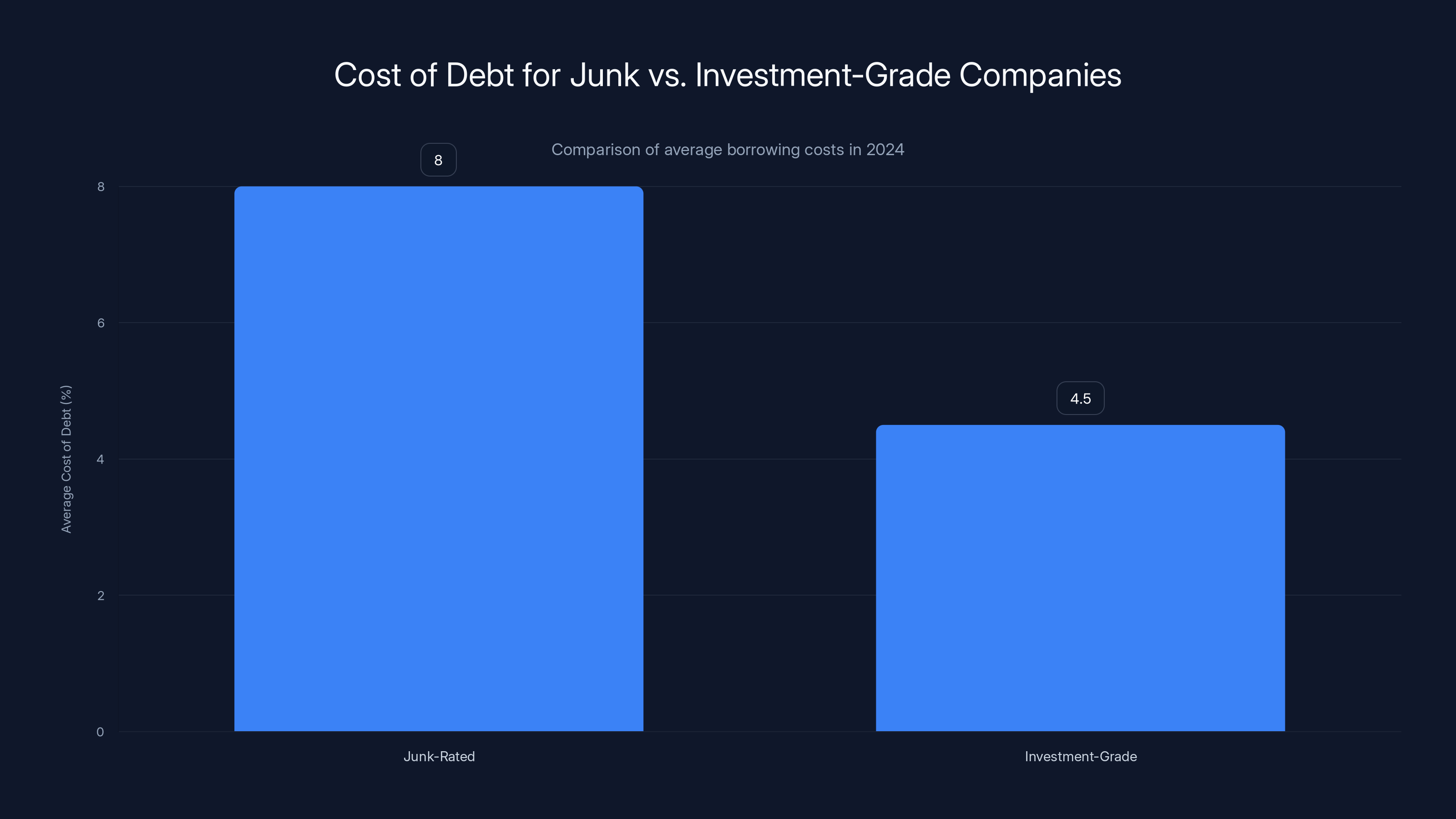

One of WBD's most pointed criticisms involved Paramount's existing credit rating. The company currently has junk-status credit, meaning it's rated below investment grade. Those bonds are speculative, high-risk debt that typically trades at significant yield premiums over safer securities.

Adding $87 billion in new debt to that already-fragile credit profile would almost certainly trigger credit rating downgrades from Moody's, S&P, and Fitch. And that's where the real damage happens.

When your credit rating gets downgraded, everything gets more expensive. Refinancing existing debt becomes harder and more costly. New debt requires higher interest rates to compensate investors for increased risk. Suppliers and partners may demand different payment terms. Insurance costs rise.

WBD's board was pointing out a vicious cycle: Paramount's junk credit rating would worsen under the debt load of this deal, making future financing more expensive, reducing the company's flexibility, and increasing the probability that the deal itself could collapse before closing due to covenant violations or market conditions changing.

It's not a coincidental risk. It's a structural inevitability baked into the deal economics.

WBD's leveraged buyout of Paramount results in a debt-to-revenue ratio of 2.9, significantly higher than typical industry standards, highlighting the financial risk involved (Estimated data).

Free Cash Flow: The Silent Killer in Acquisition Deals

WBD's letter to shareholders highlighted something that often gets overlooked in merger announcements: free cash flow. Specifically, WBD noted that Paramount has negative free cash flow that would only worsen post-acquisition.

Free cash flow (operating cash flow minus capital expenditures) is arguably the most important metric in evaluating whether a company can service debt. It's the actual cash available to shareholders and creditors after the business has funded its ongoing operations.

Paramount's negative free cash flow means the company is currently burning through cash rather than generating it. That might sound like a dealbreaker on its face, but context matters. Media companies often have lumpy cash flows. A big content release might cost

But here's the critical point: adding a $108.4 billion acquisition to that situation doesn't improve cash dynamics. It worsens them, at least initially. Paramount would have:

- Immediate integration costs (IT systems, redundant headcount elimination, facility consolidation)

- One-time deal financing costs and investment banking fees

- Potential need to invest in WBD's content pipeline to maintain quality

- Revenue disruption as customers and partners adjust to the new entity

All of that creates a window of vulnerability, typically 12-24 months post-closing, where cash flow pressure is intense. That's exactly when you don't want to be servicing $87 billion in debt.

Contrast that with Netflix. The company generated an estimated $12 billion in free cash flow for 2026, according to WBD's analysis. Netflix isn't burning through cash. It's generating it at massive scale. That fundamentally changes the risk profile of the Netflix merger.

Market Capitalization Mismatch: The 7X Problem

WBD's board highlighted a number that sticks with you: Paramount is a company with roughly a

That's not unprecedented in M&A, but it's rare for good reasons. When the acquirer is much smaller than the target, or when the deal is financed heavily with debt, you're essentially building a house of cards. A small stumble becomes a structural failure.

Consider what could go wrong:

If Paramount's standalone business falters (streaming competition increases, content underperforms, subscriber losses accelerate), the company's ability to support the WBD debt load evaporates. The combined entity's credit rating deteriorates further. Refinancing becomes nearly impossible. Default risk spikes.

If WBD's assets underperform expectations post-acquisition (content underperforms, licensing deals expire, franchise fatigue), the whole thesis collapses. The debt was supposed to be serviced by WBD's cash flows. If those flows shrink, the leverage that looked manageable suddenly becomes crushing.

If broader market conditions change (recession, credit tightening, loss of major content licensing partners), both companies together still can't generate enough cash to support $87 billion in debt without aggressive restructuring.

The 7X multiple matters because it leaves almost zero margin for error. In healthy acquisitions, the leverage multiple is typically 3-4X for stable businesses, 2-3X for cyclical businesses like entertainment. At 7X, you're betting everything works perfectly. Nothing goes wrong. Every franchise delivers. Every quarter exceeds expectations.

That's not a business strategy. That's a prayer.

Netflix's superior market cap, investment-grade credit rating, and positive free cash flow highlight its financial stability compared to Paramount. Estimated data for credit ratings: A/A3 as 2 and Junk as 0.

The Netflix Alternative: Why Investment-Grade Stability Matters

To understand why WBD's board preferred the Netflix deal, you have to look at Netflix's balance sheet and cash position in contrast to Paramount's.

Netflix, as of WBD's analysis:

- Market Cap: Approximately $400 billion (nearly 28 times Paramount's)

- Credit Rating: A/A3 (investment grade, not speculative)

- Free Cash Flow: More than $12 billion for 2026

- Business Model: Mature streaming platform with pricing power and global scale

Paramount, in contrast:

- Market Cap: Approximately $14 billion

- Credit Rating: Junk status (below investment grade)

- Free Cash Flow: Negative

- Business Model: Diversified media, but subordinate to Netflix in streaming, declining in traditional TV

The deal structure also differs fundamentally. Netflix's bid was $82.7 billion structured as a combination of cash and stock. That means:

WBD shareholders would receive a mix of Netflix shares and cash, giving them equity upside in a company with proven cash generation. They wouldn't be betting solely on the combined entity's ability to service debt. They'd have a piece of Netflix, which is operationally excellent.

Paramount's revised offer is $108.4 billion, but nearly all of it depends on Paramount and Ellison borrowing vast sums. WBD shareholders would get paid, but the company they own post-transaction would be heavily indebted and significantly riskier.

From a risk-adjusted perspective, the Netflix deal exchanges the uncertainty of Paramount's leverage management for exposure to Netflix's proven business excellence. That's why WBD's board unanimously preferred it.

It's also worth noting that Netflix actively welcomed WBD's board decision. In a statement, Netflix said the merger would "bring together highly complementary strengths and a shared passion for storytelling." That's not just corporate PR. It signals Netflix's confidence that the deal makes strategic and financial sense, not just that Netflix wants to grow at any cost.

The Strategic Implications: What This Rejection Signals

WBD's second rejection of Paramount tells the market something clear: the board is unified, confident, and not playing games with negotiations.

In merger negotiations, rejection signals matter. If a board seems willing to consider every bid, every revised offer gets incremental attention. Bidders sense weakness and keep improving proposals. But if a board says no twice, with escalating conviction, bidders eventually believe it.

Paramount will likely go one of two directions from here:

Option One: Withdraw and Refocus

Paramount could accept that WBD prefers Netflix and move on. The company would then focus on its own strategy: streaming expansion, cost reduction, finding scale through organic growth or smaller acquisitions. Paramount's stock would likely stabilize. The uncertainty would dissipate. Paramount could eventually become a more attractive acquisition target itself, once the company stabilizes and demonstrates cash flow improvement.

Option Two: Make Another Offer

Paramount could come back with yet another revised proposal. But it's hard to see what that would look like. A higher price doesn't solve the debt problem. A lower debt-to-equity ratio would mean either: Paramount puts up more equity (diluting existing shareholders and Ellison), or the deal size shrinks to something less ambitious.

Either way, Paramount is constrained. The fundamental issue isn't the price or even the guarantee. It's the structure. You can't fix leverage problems by throwing more money at them.

The Netflix offer is financially stronger with no debt financing and substantial free cash flow, while the Paramount offer relies heavily on debt, posing higher risk (Estimated data).

Industry Context: Why Media M&A Is So Difficult Right Now

This battle between Paramount and WBD isn't happening in a vacuum. It reflects broader challenges in media consolidation that have made acquisition financing particularly treacherous.

The entertainment industry is in structural transition. Traditional television is declining. Streaming is maturing and competitive. Content costs remain high. Licensing agreements are becoming less predictable. Shareholder expectations for media companies have become more conservative.

That context makes aggressive leverage in media deals especially dangerous. In the 1990s and early 2000s, companies could justify 5-6X leverage in media deals because the industry was growing and financing was cheap. Today, with interest rates higher, growth slower, and competition intense, that same leverage structure creates serious financial risk.

WBD's board was essentially saying: we understand the appeal of a higher price, but we live in 2025 media economics, not 2005 media economics. Paramount's deal structure doesn't fit the current environment.

Consider the recent history. Disney's acquisition of 21st Century Fox (2019) for roughly $71 billion involved significant debt. But Disney had investment-grade credit, substantial free cash flow, and a diversified business. Paramount attempting to acquire WBD using junk-rated debt is fundamentally different in risk profile.

The Role of Larry Ellison's Guarantee: Power and Limitation

Larry Ellison's $40 billion personal guarantee was meant to be a game-changer. It shows Ellison is serious. It demonstrates that enormous financial resources are backing Paramount's offer. For some shareholders, it might seem compelling: one of the world's richest people guaranteeing the deal.

But WBD's board looked past the psychology to the mechanics.

A personal guarantee from Ellison doesn't solve the fundamental problem: Paramount still needs to service $54 billion in additional debt beyond Ellison's guarantee. That debt doesn't come from Ellison. It comes from capital markets. And capital markets price debt based on the borrower's creditworthiness, not on guarantees from rich people.

Moreover, if Paramount defaults and Ellison is forced to make good on his guarantee, he's personally on the hook for billions of dollars. That's a powerful incentive for him to ensure things work out. But from WBD shareholders' perspective, you're essentially betting that one billionaire's financial fate and willingness to spend his own money remains your best security blanket. That's not how institutional investors think about risk.

Ellison's guarantee is more about signaling confidence than solving the core financial problem. And WBD's board saw through that signal to the underlying reality: a heavily leveraged deal structure that can't be fixed by personal guarantees alone.

Junk-rated companies face significantly higher borrowing costs, averaging 8%, compared to 4.5% for investment-grade companies. This spread can lead to billions in extra interest costs.

The Netflix Merger: Why It Looks Better from a Shareholder Perspective

As WBD's board emphasized, the Netflix deal offers several advantages that go beyond just price.

First, there's the financial strength. Netflix is generating $12 billion in free cash flow annually. That's the cash available to service debt, fund growth, and return value to shareholders after the company has paid all operating costs and capital expenditures. Paramount's negative free cash flow in comparison looks precarious.

Second, there's the strategic fit. Netflix is a global streaming powerhouse with proven operational excellence. WBD brings highly valuable content IP (Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, DC Comics) and a traditional media business. Together, they have more complementary strengths than Paramount and WBD. Netflix could immediately leverage WBD's content across its global platform. Paramount would struggle to integrate WBD's business without crippling its own operations under debt service pressure.

Third, there's the balance sheet strength. Netflix has an investment-grade credit rating. That means Netflix can borrow money at reasonable rates. Netflix can negotiate with suppliers, partners, and employees from a position of strength. A debt-laden Paramount post-acquisition would have limited financial flexibility.

Fourth, there's the strategic optionality. After integrating with Netflix, WBD shareholders gain exposure to a company with multiple growth vectors: international expansion, advertising revenue growth, gaming, live events. After integrating with Paramount, WBD shareholders gain exposure to a heavily leveraged company trying to manage debt payments.

From a pure shareholder perspective, if the Netflix deal is lower in price but significantly lower in risk, it often creates more value. That's not always intuitive, but it's how institutional investors think about M&A.

What Happens Next: Three Possible Scenarios

Paramount's path forward from here is unclear, but a few scenarios seem plausible.

Scenario One: Paramount Withdraws, Focuses on Standalone Strategy

Paramount quietly ends the WBD pursuit and announces a refocused strategy around its core streaming and traditional media businesses. The company cuts costs aggressively, focuses on subscriber growth for Paramount+, and attempts to stabilize cash flows. Over 18-24 months, Paramount potentially becomes a more attractive acquisition candidate at a lower price for a different buyer. This seems most likely given WBD's united board stance.

Scenario Two: Paramount Makes a Final Offer

Paramount comes back with one more proposal, perhaps at a similar or slightly higher price, but with a different structure. Maybe they offer less debt and more Ellison equity. Maybe they offer to sell non-core assets to reduce financing needs. But WBD's board would likely need to see a fundamental change in leverage structure, and that's hard for Paramount to accomplish without diluting the transaction value.

Scenario Three: Shareholder Activism or Counter-Offers

If WBD shareholders vote against the Netflix deal for some reason, or if Paramount mounts a shareholder campaign, things could become messier. But WBD's united board stance and the clear financial advantages of the Netflix deal make this scenario unlikely. Institutional investors understand leverage risk.

Most likely, Paramount's bid for WBD ends here. The company will pivot to its own turnaround strategy, which actually might be healthier long-term than attempting to acquire and integrate a much larger company while managing crushing debt loads.

Lessons for Media Consolidation and Deal Financing

WBD's rejection of Paramount's offer offers several important lessons for future M&A in media and other industries.

Lesson One: Financial Structure Matters More Than Price

A lower offer from a financially sound company can create more shareholder value than a higher offer financed with aggressive leverage. WBD's board prioritized this principle over maximizing the nominal purchase price. That's actually unusual for boards, which often face pressure to accept the highest bid. WBD's conviction here suggests institutional investors increasingly care about deal structure risk, not just headline prices.

Lesson Two: Junk Credit Ratings Are a Real Constraint

Paramount's existing junk-status credit made this deal structurally more difficult. If Paramount had an investment-grade rating, the math would have looked slightly better (lower borrowing costs, better covenant flexibility). The company's existing credit weakness became a compounding problem in the acquisition context. This suggests Paramount should focus on improving its own balance sheet before attempting major acquisitions.

Lesson Three: Free Cash Flow is the True Metric

WBD didn't just compare market caps or even debt ratios. The board explicitly noted Paramount's negative free cash flow and Netflix's positive $12 billion free cash flow. That comparison crystallized the risk difference. In future deals, expect more boards to demand detailed free cash flow analysis rather than accepting abstract financial models.

Lesson Four: Leverage Multiples Have Tightened

The days of financing major acquisitions at 6-7X leverage are ending. Interest rates are higher. Investor risk appetite is lower. Boards are more skeptical. Modern media deals will need to be financed at 3-4X leverage or rely on cash-and-stock combinations like Netflix's offer. That structurally limits deal sizes and favors acquirers with strong balance sheets.

The Broader Media Landscape: Consolidation in Question

WBD's decisive rejection of Paramount also raises questions about the future of media consolidation more broadly.

For the past two decades, media industry strategy has been built around scale. Bigger companies can negotiate better licensing deals, spread content costs across more platforms, and achieve operational efficiencies. That thinking drove mega-deals like Disney's Fox acquisition, AT&T's Warner acquisition, and countless others.

But the streaming era is forcing a reconsideration. Scale still matters, but financial flexibility matters more. A smaller company with a strong balance sheet and positive free cash flow can compete effectively in streaming. A larger company burdened with debt service becomes less competitive, not more.

Paramount's failed bid might represent a turning point. Future media deals might be smaller, more conservative, and more focused on finding compatible partners rather than achieving maximum scale. That would be a fundamental shift from the mega-merger strategy that dominated the 2000s and 2010s.

Netflix's deal with WBD, if it closes, would represent this new paradigm: scale plus financial strength, not leverage-driven mega-deals.

Timing and Market Conditions: Why Now Matters

Paramount's timing in this pursuit also matters. The deal was announced and pursued in late 2025 and early 2026, a period of elevated interest rates and tightening credit conditions.

In a low-interest-rate environment (like 2020-2021), aggressive leverage in acquisition deals looked more viable. Borrowing costs were minimal. The opportunity cost of equity was high. Boards were more willing to accept leverage-heavy structures.

But with interest rates elevated and credit spreads wider, the economics have shifted. Junk-rated debt costs significantly more. The financial incentive to lever up deals is reduced. And boards are correspondingly less willing to accept leverage-heavy proposals.

Paramount's timing might have been better in 2021 or 2022. In 2025-2026, the same deal structure looks much riskier from a cost-of-capital perspective.

That's a lesson for future acquirers: macroeconomic conditions and interest rate environments matter enormously for leveraged acquisition financing. A deal that makes sense in a low-rate environment can become unfinanceable as rates rise. Timing M&A attempts to match favorable credit conditions is itself a skill.

FAQ

What is a leveraged buyout and why does it matter in acquisition deals?

A leveraged buyout (LBO) is an acquisition financed primarily with borrowed money, using the target company's assets and cash flows as collateral. It matters because the acquirer is betting the target's cash generation will service the debt. If that assumption proves wrong, the combined entity faces financial distress. WBD's board rejected Paramount's deal because it had LBO characteristics (mostly debt-financed) despite Paramount not being a private equity firm. The structural risk was unacceptable given Paramount's existing financial weakness.

Why would Paramount's debt problems make the deal riskier for WBD shareholders?

Paramount would need to borrow approximately $87 billion to fund the deal. If interest rates rise, refinancing costs increase. If WBD's content underperforms, cash flows decline and debt service becomes harder. If Paramount's business deteriorates, the combined entity might not generate enough cash to service the debt, creating default risk and potential bankruptcy. WBD shareholders would bear that risk in the form of a stock price collapse. The Netflix deal avoids this risk because Netflix generates substantial free cash flow and has an investment-grade credit rating.

How does the Netflix deal differ financially from the Paramount offer?

The Paramount offer was

What does a company's free cash flow tell you about its ability to handle acquisition debt?

Free cash flow is the actual cash available after the company pays all operating costs and capital expenditures. If free cash flow is positive and growing, the company can service debt reliably. If free cash flow is negative or declining, debt service becomes difficult, especially if debt is newly added. Netflix's $12 billion free cash flow means Netflix can easily service the debt required for the WBD deal and still have cash for other investments. Paramount's negative free cash flow means Paramount would struggle to service additional debt, making the deal structurally risky.

Why does Paramount's current junk credit rating make the deal harder?

Companies with junk credit ratings borrow at significantly higher interest rates (typically 6-9 percent) than investment-grade companies (typically 3-5 percent). That higher rate applies to all new debt issued. So Paramount would be borrowing

Could Larry Ellison's personal guarantee have made the deal work?

Ellison's

What happens to Paramount now that WBD has rejected the offer twice?

Paramount will likely either make a final revised offer with a fundamentally different structure (less debt, more equity, lower price), or withdraw the pursuit entirely. Given WBD's united board stance and the clarity of the Netflix deal, most analysts expect Paramount to focus on its own business strategy rather than pursue WBD further. Paramount could potentially become a more attractive acquisition target itself over time if the company stabilizes its business and improves cash flows.

Why would Netflix welcome this decision when it could face a competing bid?

Netflix's statement welcoming WBD's board decision reflects confidence that the deal makes strategic and financial sense. Netflix likely believes that if Paramount tried to restart negotiations with an improved offer, WBD's board would still prefer Netflix based on financial strength and strategic fit. More fundamentally, Netflix doesn't want WBD shareholders distracted by competing bids. A clean, uncomplicated path to closing the Netflix deal is worth more to Netflix than forcing a higher-priced deal with other parties.

Conclusion: A New Standard for Acquisition Governance

WBD's decisive rejection of Paramount's revised bid represents more than just a business decision. It signals a meaningful shift in how boards evaluate major acquisitions in the modern financial environment.

For decades, the corporate finance world operated under a fairly simple principle: the highest price wins. Shareholders got the most cash or stock per share, and that was presumed to be the best outcome. Boards that rejected higher bids faced intense pressure from activist investors and plaintiff lawyers threatening derivative suits.

WBD's board has essentially said: we care about price, but we care more about deal structure and the long-term financial health of the combined company. Paramount's offer was higher, but the deal structure was riskier. Netflix's offer is lower, but the deal structure is healthier. We choose health.

That's not an obvious choice. It requires board members to have conviction about the long-term risks of leverage and the strategic value of financial stability. It requires shareholders and institutional investors to understand that a lower deal price with better risk characteristics can create more value than a higher price with worse characteristics.

Paramount's failure with WBD might also reset expectations in media consolidation. The days of financing massive acquisitions with aggressive leverage are likely ending. Future deals will need to be smaller, more conservative, and more focused on combining companies with complementary strengths rather than pursuing scale at any cost.

That's probably healthy for the industry. Media companies that are operationally excellent, financially stable, and strategically focused will outcompete media companies that are burdened with debt and struggling to service interest payments. WBD's board understood that principle and acted accordingly.

Netflix's approach—bringing financial strength together with valuable content assets, structuring the deal with equity participation rather than pure debt financing—represents the future of media consolidation. Paramount's approach—attempting to buy a much larger company using aggressive leverage from a weaker financial position—represents the recent past.

The rejection of Paramount's $108.4 billion bid wasn't just a decision about this specific deal. It was a statement about what modern boards believe makes acquisition deals sustainable, valuable, and worth pursuing.

WBD shareholders should pay attention to that clarity. In an increasingly uncertain business environment, a board willing to prioritize long-term financial health over short-term deal premium is exactly what you want making strategic decisions for your company.

Key Takeaways

- WBD's board unanimously rejected Paramount's 87B debt load and 7X leverage multiple

- Paramount's junk credit rating would worsen post-acquisition, raising borrowing costs and increasing default risk

- Netflix's 400B market cap, investment-grade credit, and $12B free cash flow

- Deal structure matters more than headline price: lower offers from financially strong acquirers often create more shareholder value than higher leveraged offers

- Modern media deals require 3-4X leverage maximum; 6-7X leverage creates structural risk of financial distress within 36 months per historical analysis

Related Articles

- NYT Strands Hints & Answers for January 8 [2025] Game #676

- IKEA Matter Smart Home Integration: Complete Guide [2025]

- IKEA Kallsup $10 Bluetooth Speakers: The Game-Changing Budget Audio [2025]

- Clear Drop Soft Plastic Compactor: A Home Solution to Plastic Waste [2025]

- Warner Bros. Discovery Rejects Paramount Skydance Bid: Why Netflix Won [2025]

- Best Gaming TV for PS5 & Xbox Series X [2025]: Complete Buyer's Guide

![Warner Bros. Discovery Rejects Paramount's $108.4B Bid Over Debt Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/warner-bros-discovery-rejects-paramount-s-108-4b-bid-over-de/image-1-1767798554774.png)