Introduction: When Healthcare Meets Immigration Enforcement

Rebekah Stewart was a dedicated nurse. She'd spent a decade working for the U.S. Public Health Service, answering calls to serve during hurricanes, wildfires, and disease outbreaks. She was proud of her work. Then came the phone call in April that changed everything.

The Trump administration had decided to use Guantánamo Bay as an immigration detention facility. Stewart was selected for deployment there. Not asked. Selected. Deployments, she learned, aren't something you typically refuse without consequences.

She pleaded with the coordinating office. They found another nurse to go in her place. But the reprieve was temporary. Weeks later, she received new orders: report to an ICE detention center in Texas instead.

That's when Stewart made the decision that would haunt her. She resigned after ten years of service. She walked away from her dream job, giving up the prospect of a pension she'd worked toward for two decades. Why? Because she couldn't ethically participate in what she saw as a humanitarian crisis manufactured by government policy.

Stewart's story isn't unique. Other healthcare professionals have faced the same impossible choice. Some have resigned. Others remain in these postings, caught between their oath to do no harm and the reality of a detention system they believe is fundamentally broken. Their experiences reveal something the public rarely sees: what happens when doctors and nurses are forced to provide care in settings they believe are inherently inhumane.

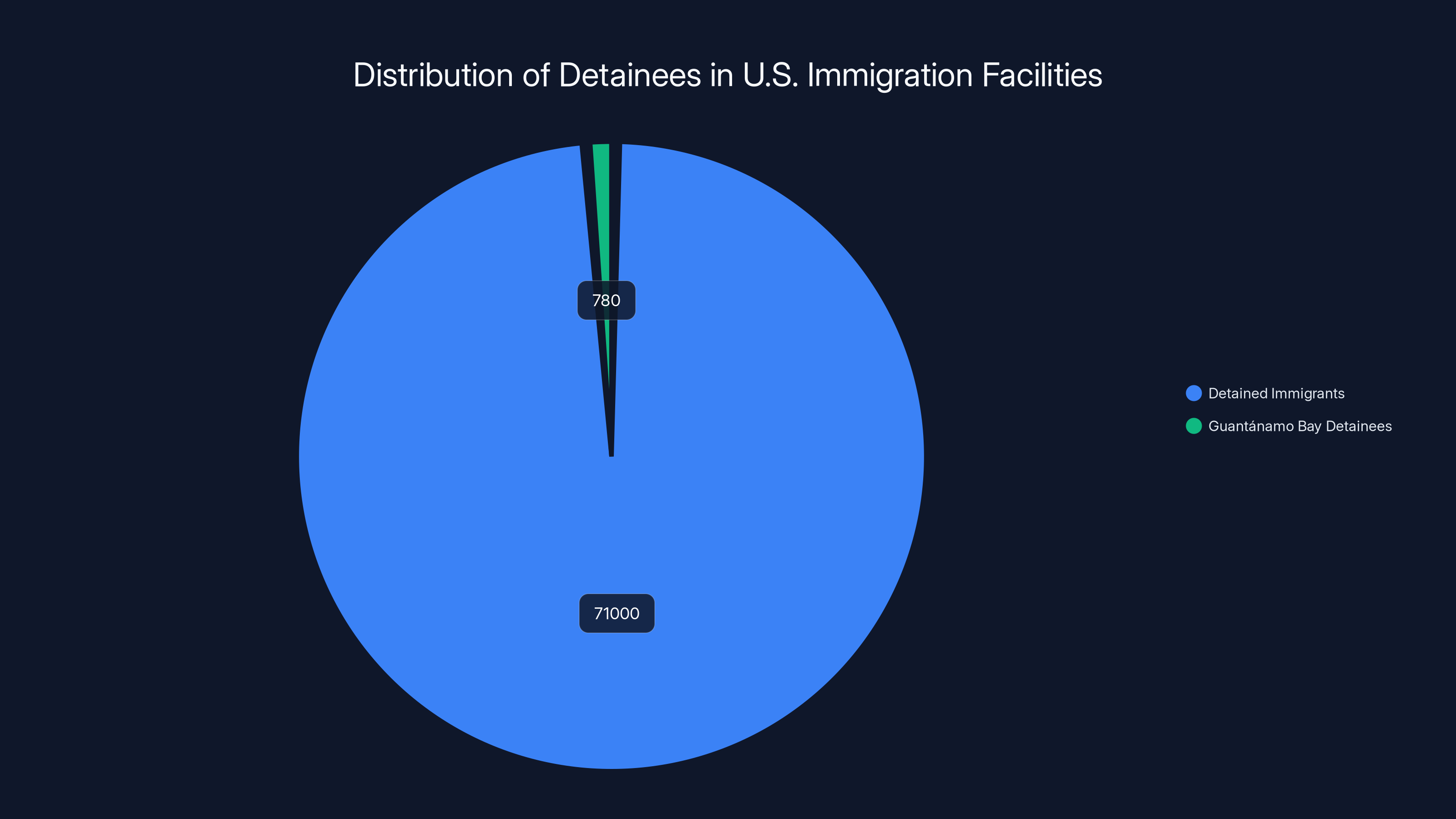

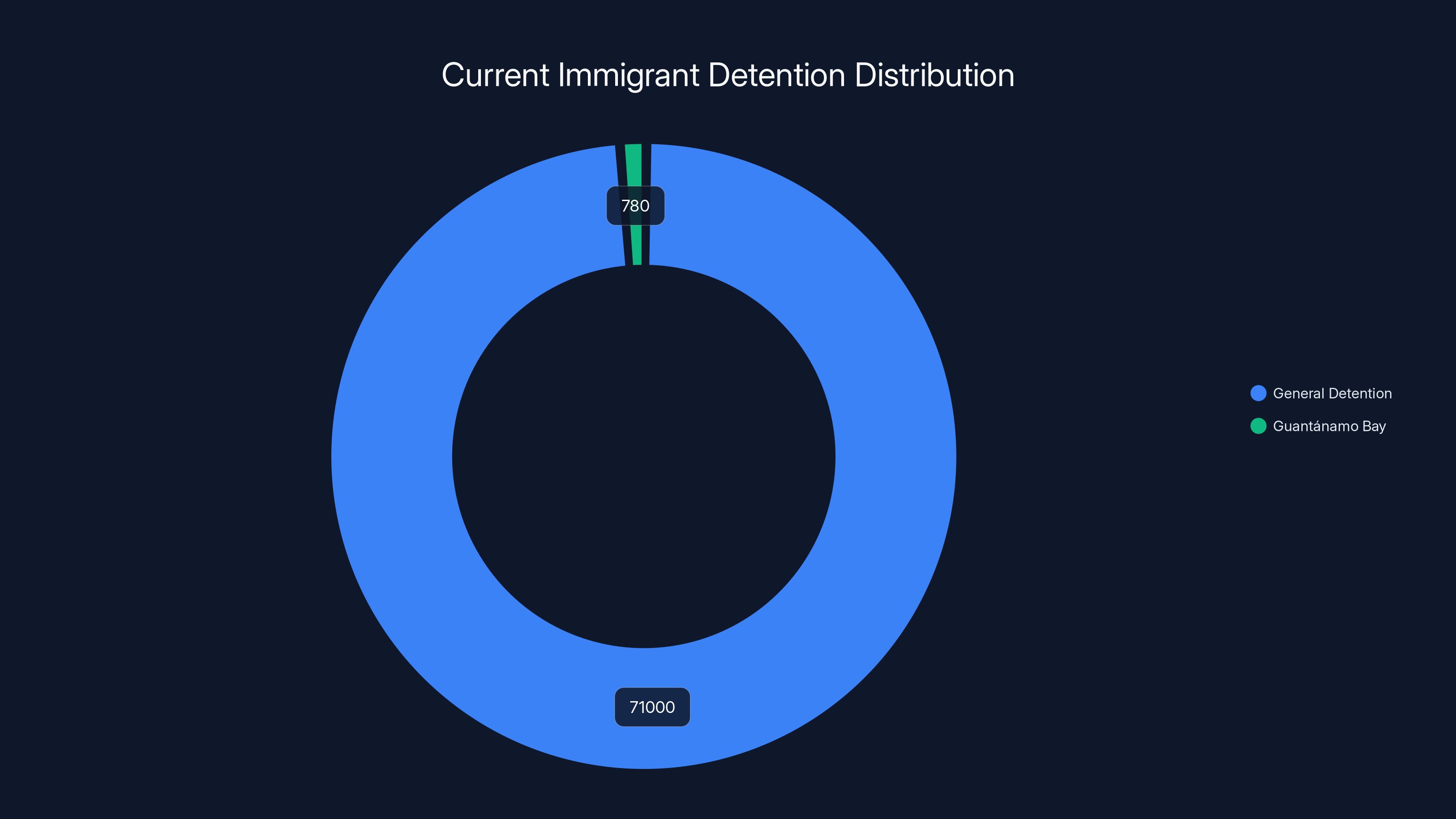

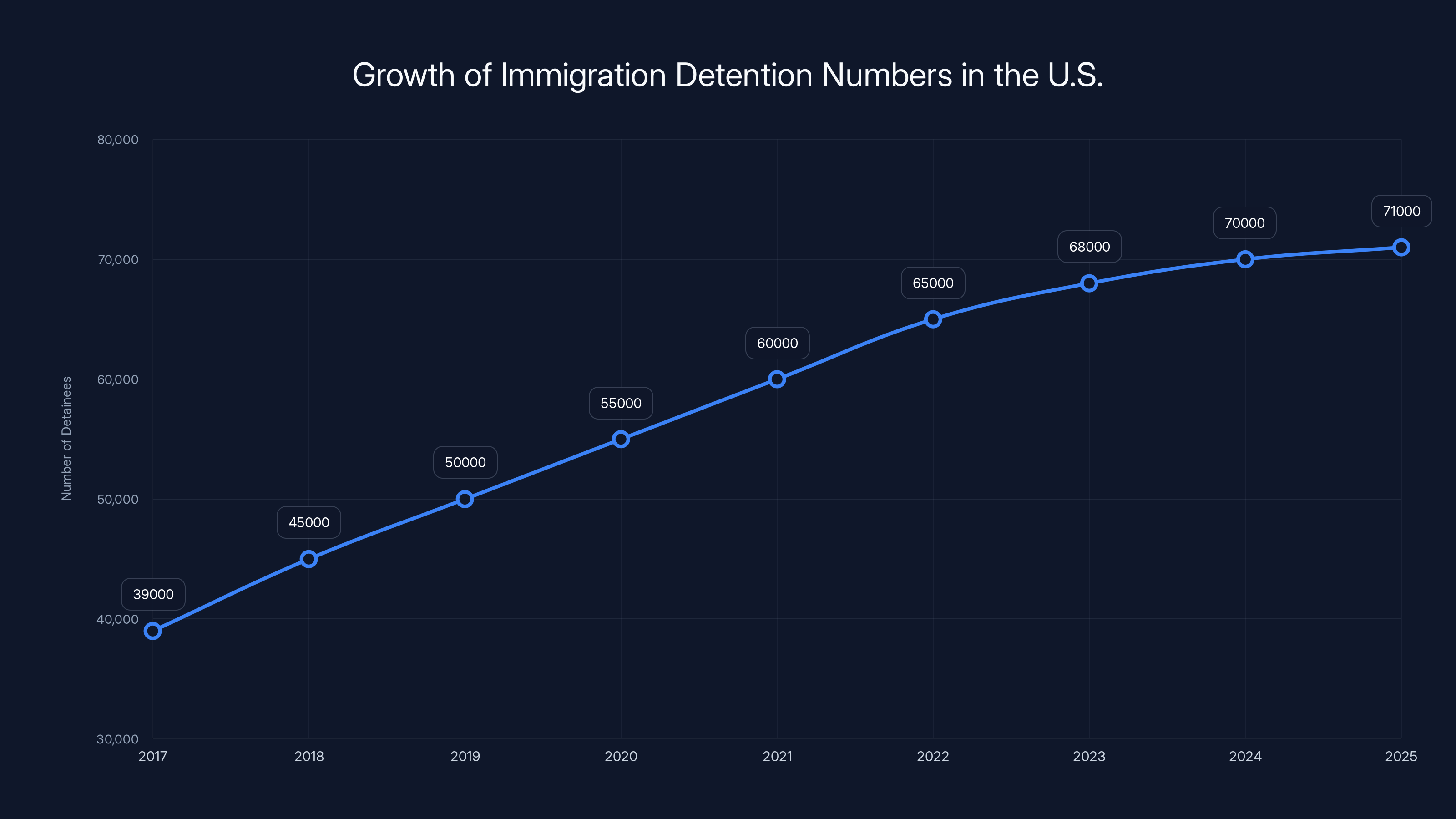

The numbers paint a stark picture. As of 2025, approximately 71,000 immigrants are detained in U.S. facilities, according to Immigration and Customs Enforcement data. Most have no criminal record. About 780 noncitizens have been sent to Guantánamo Bay, though this number fluctuates as detainees arrive and others are returned or deported. In May, a chaplain's progress report noted that as many as 90 percent of detainees at Guantánamo were classified as "low-risk."

Yet the official narrative persists. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem insists that Guantánamo Bay will hold "the worst of the worst." The reality, according to multiple news organizations and the accounts of health workers themselves, tells a different story. What emerges from these accounts is a crisis of conscience, a moment when the medical profession confronted the machinery of immigration enforcement and found it incompatible with their fundamental values.

This isn't just a story about one nurse or one detention facility. It's about how a government agency transforms healthcare workers into agents of enforcement, how moral injury accumulates in uniform, and what happens when people who've dedicated their lives to healing are asked to enable what they perceive as harm.

TL; DR

- Healthcare exodus: Public Health Service nurses and doctors are resigning over forced ICE and Guantánamo Bay deployments, abandoning pensions and careers

- Scale of detention: About 71,000 immigrants currently detained, with roughly 780 at Guantánamo Bay, though 90% were classified as "low-risk"

- Ethical breakdown: Health workers describe dark detention cells, sleep deprivation, family separation, and minimal medical oversight in conditions they consider inhumane

- System pressure: Deployments are rarely voluntary, leaving workers with choices between participation or resignation

- Rare visibility: Most detained immigrants only learn their location from medical staff, showing extreme information control in the system

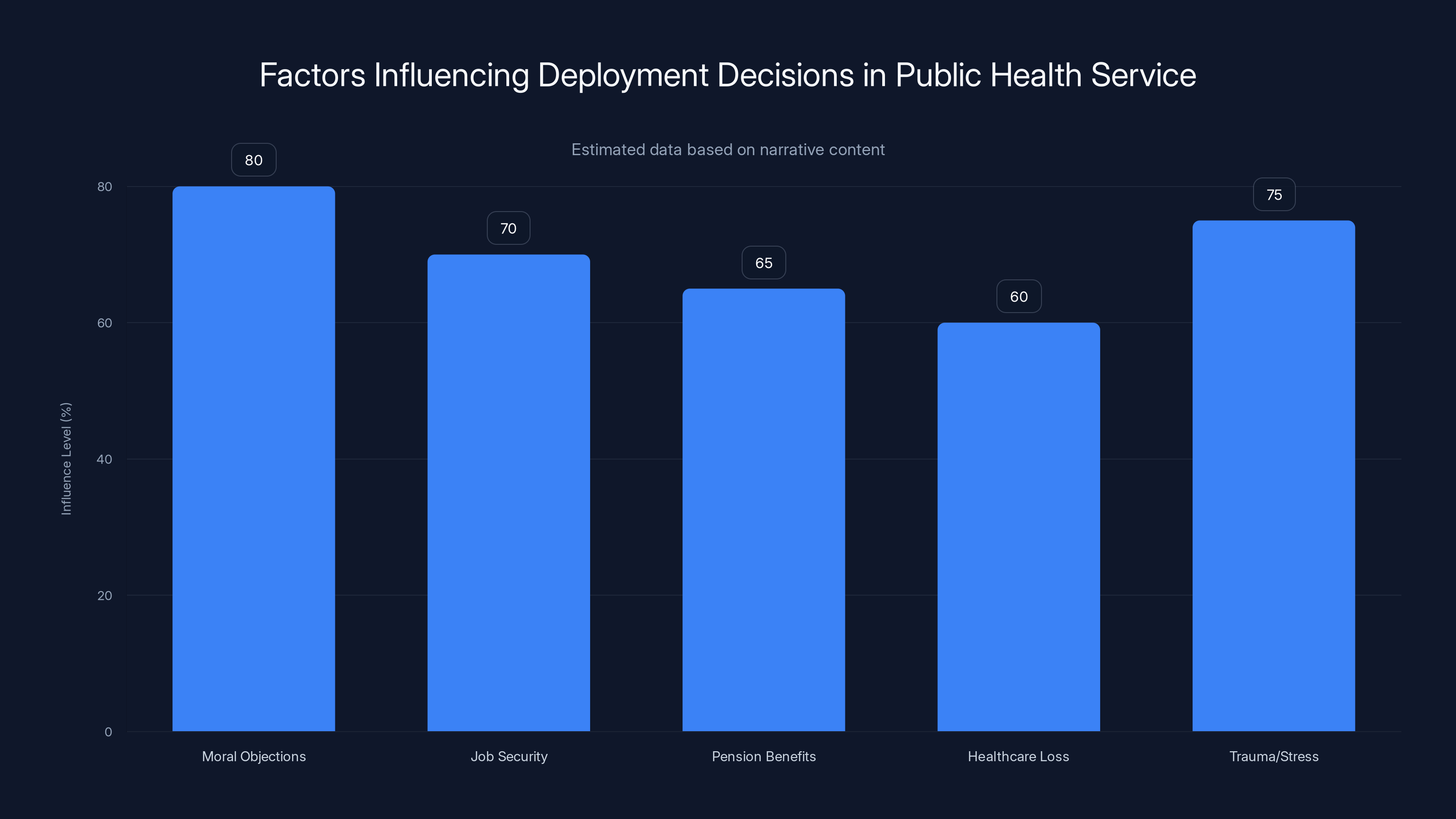

Estimated data shows moral objections and trauma/stress as leading factors influencing deployment decisions, highlighting the complex pressures faced by healthcare workers.

The U.S. Public Health Service: Military Structure, Civilian Mission

Most Americans have never heard of the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service. That's intentional. These officers work behind the scenes, mostly invisible to the public they serve. But understanding who they are and how they operate is essential to understanding this crisis.

The Commissioned Corps operates as a uniformed service of approximately 6,000 healthcare professionals. These aren't military personnel in the traditional sense, but they function like the stethoscope-wearing equivalent of soldiers. They wear ranks, follow a chain of command, and answer to federal authority. The physicians, nurses, therapists, engineers, and other health professionals in the Corps take an oath that commits them to respond to national health emergencies.

On paper, the mission is noble. During hurricanes, the Corps deploys to provide emergency medical care. After mass shootings, they staff crisis facilities. During measles outbreaks or disease epidemics, they mobilize to contain spread and provide treatment. They fill gaps at federal agencies across the government. The CDC, Indian Health Services, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the Coast Guard, FEMA, ICE, and countless other agencies rely on Commissioned Corps officers to staff their healthcare operations.

The structure sounds military because it is military-adjacent. Officers have rank. They follow orders. They can be reassigned. And they accept these terms when they join, understanding that deployments aren't fully voluntary in the way private-sector jobs are. You can't simply decline an assignment you dislike without consequences.

This system works well during natural disasters. A hurricane hits Louisiana, and Public Health Service officers deploy to emergency rooms. Nobody questions whether that nurse should be there. The mission aligns with their values. The work is urgent and clearly necessary. The public largely supports it.

But what happens when the government deploys these healthcare workers to enforce immigration policy? The structure that made them effective in disaster medicine becomes a trap. The same chain of command that mobilizes them for emergencies now compels them to participate in something many believe contradicts their professional ethics.

Admiral Brian Christine, the assistant secretary for Health at the Department of Health and Human Services who oversees the Public Health Service, acknowledged this tension in a statement. He argued that Public Health Service officers have a duty to "show up, provide humane care, and protect health," regardless of the political context. In his framing, these officers are simply providing healthcare to people in custody. It's their duty. The ethics of the detention system itself aren't their concern.

But that argument fails to account for how many officers actually perceive these deployments. For them, providing care in a system they believe is fundamentally inhumane doesn't constitute care at all. It becomes complicity.

In 2025, approximately 71,000 immigrants are detained in U.S. facilities, with 780 specifically at Guantánamo Bay. This highlights the scale of immigration detention in the U.S.

Guantánamo Bay as an Immigration Detention Facility: An Unprecedented Use

Guantánamo Bay has existed in the American consciousness as a symbol of something dark and troubling. Following 9/11, the U.S. detained suspected terrorists there, a practice that generated international condemnation for the harsh conditions and interrogation techniques used. Over time, it became synonymous with indefinite detention without trial and the erosion of due process protections.

But using Guantánamo to house immigrants is different from its post-9/11 mission. According to research and reporting, this marks the first time in American history that Guantánamo has been used to detain immigrants who were living in the United States. The symbolism matters. It sends a message about how the government views certain people: dangerous enough to require the most restrictive facility available.

The Trump administration made no secret of its intentions. Within weeks of inauguration, the government began moving noncitizens to Guantánamo. The stated rationale was to handle the influx of detained immigrants, with capacity at traditional detention facilities strained. The political rationale was equally clear: use the offshore base to move immigration detention outside the reach of normal legal oversight.

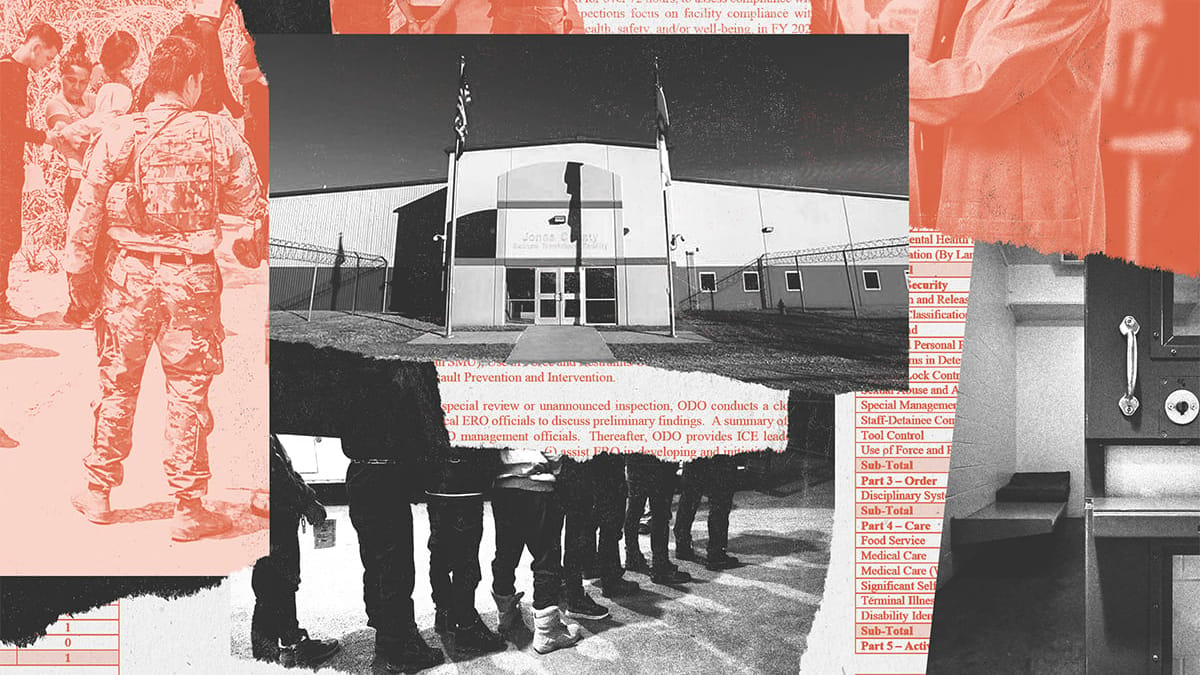

Public Health Service officers deployed there describe conditions that would alarm any healthcare professional. Camp 6, where many detainees are held, is a dark facility where sunlight doesn't penetrate. The name itself references its history: it's the same facility that previously held men suspected of having ties to al Qaeda. Detainees sleep in cells, with little exposure to natural light or fresh air. Some detainees, according to officers, didn't even know they were in Cuba until medical staff told them. Think about that for a moment. People were transported to a secret detention facility and had such limited information access that they didn't know their own location.

The psychological impact of this environment is severe. Detainees experience uncertainty about their legal status, how long they'll be detained, and whether they'll ever see family members again. Many haven't had meaningful contact with loved ones. The combination of darkness, isolation, confinement, and uncertainty creates what experts in trauma psychology recognize as conditions conducive to psychological breakdown.

One Public Health Service nurse described the reality to a reporter: "I try to be a light in the darkness, the one person that makes someone smile in this horrible mess." The very phrasing reveals the desperation. If a healthcare worker is framing their role as providing one moment of human connection in an otherwise utterly dark environment, the environment itself is the problem. The nurse is trying to mitigate something fundamentally harmful.

But here's the impossible position these workers face: by providing compassionate care in these conditions, do they enable the system to continue? If detainees have access to medical care, does that make the detention facility seem more legitimate, more humane, more acceptable? Or is refusal to provide care a form of harm as well, leaving vulnerable people without healthcare?

Some officers have chosen resignation over complicity. Others have remained, believing they can do more good by staying and providing the best care they can. Both choices carry moral weight. Both involve sacrifice.

The Chain of Command: Deployments as Compulsion

Understanding why healthcare workers feel they can't refuse these assignments requires understanding the structure of the Public Health Service. Unlike private-sector employment, where you can quit when you disagree with assignments, the Commissioned Corps operates on a military model. Resignations have costs: lost pension benefits, lost job security, lost healthcare.

When Stewart received her initial deployment order to Guantánamo, her first instinct was to refuse. She pleaded with her coordinating office, explaining her moral objections to the assignment. She made a compelling case. The office found another nurse willing to go instead. Success, right? But the victory was short-lived.

The government didn't say, "Okay, we respect your values. You're excused from immigration detention work." Instead, it simply reassigned her to a different immigration facility. The message was clear: you will participate in immigration enforcement. Your only choice is where.

This is compulsion masquerading as choice. When the alternative to a particular deployment is reassignment to a different problematic deployment, declining the first option doesn't actually exempt you from participating in something you find morally objectionable. It just means the government gets to choose the form of your participation.

Dena Bushman faced a similar situation. She received notice of a Guantánamo deployment. Bushman was working with the CDC at the time, and she'd just been grieving the loss of colleagues in a shooting at a CDC facility in Atlanta. She was traumatized. She requested a medical waiver delaying her deployment on account of stress and grief. The request was granted temporarily.

But Bushman knew that the waiver would eventually expire. She'd be deployed eventually. Facing the prospect of returning to work after trauma and then being sent to what she perceived as an inhumane detention facility pushed her to resign. She wrote: "This may sound extreme. But when I was making this decision, I couldn't help but think about how the people who fed those imprisoned in concentration camps were still part of the Nazi regime."

That comparison provoked reaction. Some saw it as hyperbolic. Others found it apt. The comparison itself revealed something important: Bushman's moral framework didn't simply object to immigration detention. It placed detention itself—the indefinite confinement of people for their immigration status—in a category of inherent wrongness that no amount of good-faith medical care could redeem.

Several other Public Health Service officers have also resigned rather than accept immigration detention assignments. Their departures have created staffing challenges. As deployments to ICE facilities have become more frequent, finding officers willing to accept these assignments has become increasingly difficult. The government is losing institutional knowledge, experienced healthcare providers, and the accumulated wisdom of officers who understand federal health emergency response.

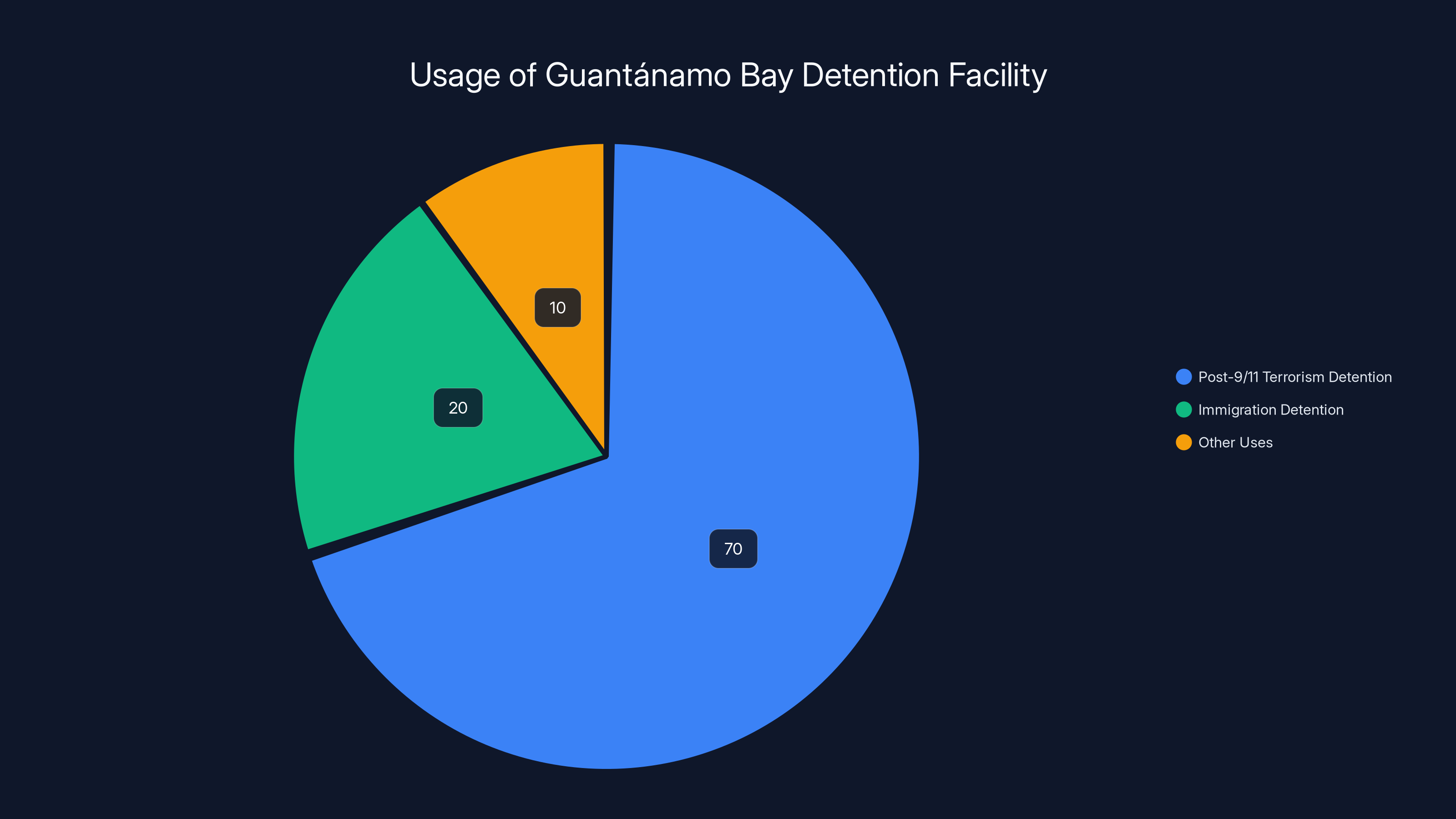

Guantánamo Bay has primarily been used for post-9/11 terrorism detention (70%), with a recent shift towards immigration detention (20%). Estimated data.

The Conditions Inside: Dark Cells and Medical Neglect

For most Americans, immigration detention is abstract. We hear statistics about the number of people detained, but the conditions themselves remain invisible. The accounts from Public Health Service officers who've worked inside these facilities offer rare windows into this world.

Detainees at Camp 6, the Guantánamo facility, are held in cells with minimal natural light. The facility was designed for a different purpose—holding terrorism suspects—and was repurposed for immigration detention. The architecture doesn't accommodate the needs of people who will be detained for weeks or months. Cells are small. Sanitation is poor. Medical care is limited.

Mental health deteriorates rapidly under these conditions. Psychologists have studied indefinite detention extensively. The symptoms are predictable: anxiety, depression, insomnia, paranoia, aggression. When uncertainty combines with confinement, psychological damage accelerates. Some detainees have been separated from children. Others don't know whether they'll ever see family members again. The legal status of many remains undefined. They're not being tried for anything. They're simply being held.

One Public Health Service nurse described finding detainees who hadn't slept in days, not because of insomnia but because the conditions made sleep nearly impossible. Overcrowding meant multiple people in spaces designed for one. Lighting remained on continuously. Noise levels were high. The body's natural sleep cycles couldn't function.

Medical care itself becomes complicated in detention settings. Detainees need care, certainly. But the context of that care is fundamentally different from care provided in hospitals or clinics. A detainee seeking medical attention for, say, an untreated infection faces a dilemma. Do they seek care and risk drawing attention that might accelerate deportation proceedings? Do they stay quiet and risk the infection worsening? The same calculus applies to mental health treatment. Acknowledging psychological distress in a detention facility becomes evidence that could be used against them in legal proceedings.

Public Health Service officers understand this bind. They see it play out regularly. A patient comes in with obvious signs of depression, anxiety, or trauma-related illness. But the officer also knows that documenting these conditions in official medical records might harm that person's legal case. The very act of providing healthcare becomes complicated by the context of confinement.

Sleep deprivation emerged repeatedly in officers' accounts. Immigration detention facilities use sleep disruption as a management tool. Lights stay on. Counts happen at irregular hours, requiring detainees to be awake and at their cells. When sleep deprivation becomes systematic, it crosses from mere discomfort into something approaching torture. The psychological effects accumulate.

One officer described the paradox of her position: "I'm supposed to provide care to people in a system designed to harm them. The best I can do is try to mitigate that harm, knowing I can't actually fix the fundamental problem." That's not healthcare as it's typically understood. That's first aid administered while the injury is actively being inflicted.

Scale of the Crisis: 71,000 Detained, Growing Numbers

The detention crisis isn't a localized problem affecting a small number of people. The scale is enormous. As of 2025, approximately 71,000 immigrants are detained in U.S. immigration facilities. That's not a small number. That's roughly the population of a mid-sized American city, imprisoned.

Most of these people have no criminal record. They're detained purely for immigration violations. Some crossed the border without authorization. Others overstayed visas or have other immigration status issues. The detention itself isn't tied to criminal conviction or criminal conduct. It's purely immigration-based detention.

The numbers have grown significantly since the Trump administration took office. The increased enforcement push has resulted in more arrests and more detention. The detention system, which was already stretched before, now operates at extreme capacity. Facilities designed for temporary holding are being used for long-term confinement. Detainees spend weeks or months in facilities built for stays of days or a few weeks.

Guantánamo Bay received approximately 780 detainees in the first several months of the new operation, according to reporting. That might seem like a small number compared to the 71,000 in detention overall. But the symbolism matters. Using America's most notorious detention facility for immigration detention sends a political message about how the government views these people.

More important, the conditions at Guantánamo represent an extreme version of conditions found in many immigration detention facilities. Overcrowding, minimal medical care, psychological trauma, and loss of hope are widespread throughout the detention system. Guantánamo just makes it more visible because of its historical weight and because some officers have been willing to speak about it.

A chaplain who observed detainees at Guantánamo filed a progress report noting that approximately 90 percent were classified as "low-risk." Think about that statistic. The government is housing 90 percent of detainees in its most restrictive facility despite these people being assessed as low-risk. That's not about security. That's about punishment or control.

The claim that Guantánamo houses "the worst of the worst," in Kristi Noem's words, doesn't align with the data. Multiple news organizations have reported that many sent to Guantánamo had no criminal convictions at all. Some had misdemeanor immigration violations or no violations at all—they were detained while seeking asylum or during border processing.

This gap between rhetoric and reality characterizes the entire detention system. The public narrative focuses on enforcement and border security. The reality involves confining hundreds of thousands of people, most without criminal history, in conditions that cause severe psychological and physical harm.

Public Health Service officers see this gap directly. They see the people in the cells. They know the diagnoses. They understand what confinement is doing to human beings. And they're being asked to enable it.

Approximately 71,000 immigrants are detained, with a small fraction at Guantánamo Bay. Estimated data highlights the scale of detention.

Medical Ethics and Detention: The Fundamental Conflict

At the core of this crisis is a fundamental conflict between medical ethics and detention enforcement. These two systems operate on opposing principles.

Medical ethics, grounded in the Hippocratic Oath and international standards, prioritizes patient welfare. A doctor's duty is to the patient. When a patient's welfare conflicts with other interests, the patient's welfare should come first. A physician should never participate in torture or cruel treatment. A physician should be an advocate for vulnerable people.

Detention enforcement operates on a different set of principles: security, control, deterrence, and resource management. A detention officer's duty is to manage detained people safely and cost-effectively. When a detainee's welfare conflicts with operational efficiency or cost reduction, operations typically take priority.

These systems are in direct conflict. An immigration detention officer might determine that solitary confinement is necessary for facility security. A physician would recognize solitary confinement as potentially causing severe psychological harm. An officer might prioritize preventing escapes. A physician would prioritize mental health treatment. An officer might see medical care as a cost to be minimized. A physician would see denial of care as unethical.

When a Public Health Service officer is deployed to a detention facility, they're placed directly in the middle of this conflict. They're expected to follow the medical ethics they learned in training and took an oath to uphold. They're also expected to follow the orders of the detention facility's authority structure.

For many officers, this conflict becomes unbearable. One nurse described the experience this way: "I went into nursing to help people. I believe healthcare is a human right. I can't reconcile that belief with working in a system that uses detention as punishment. It's not actually healthcare. It's medical theater in support of enforcement."

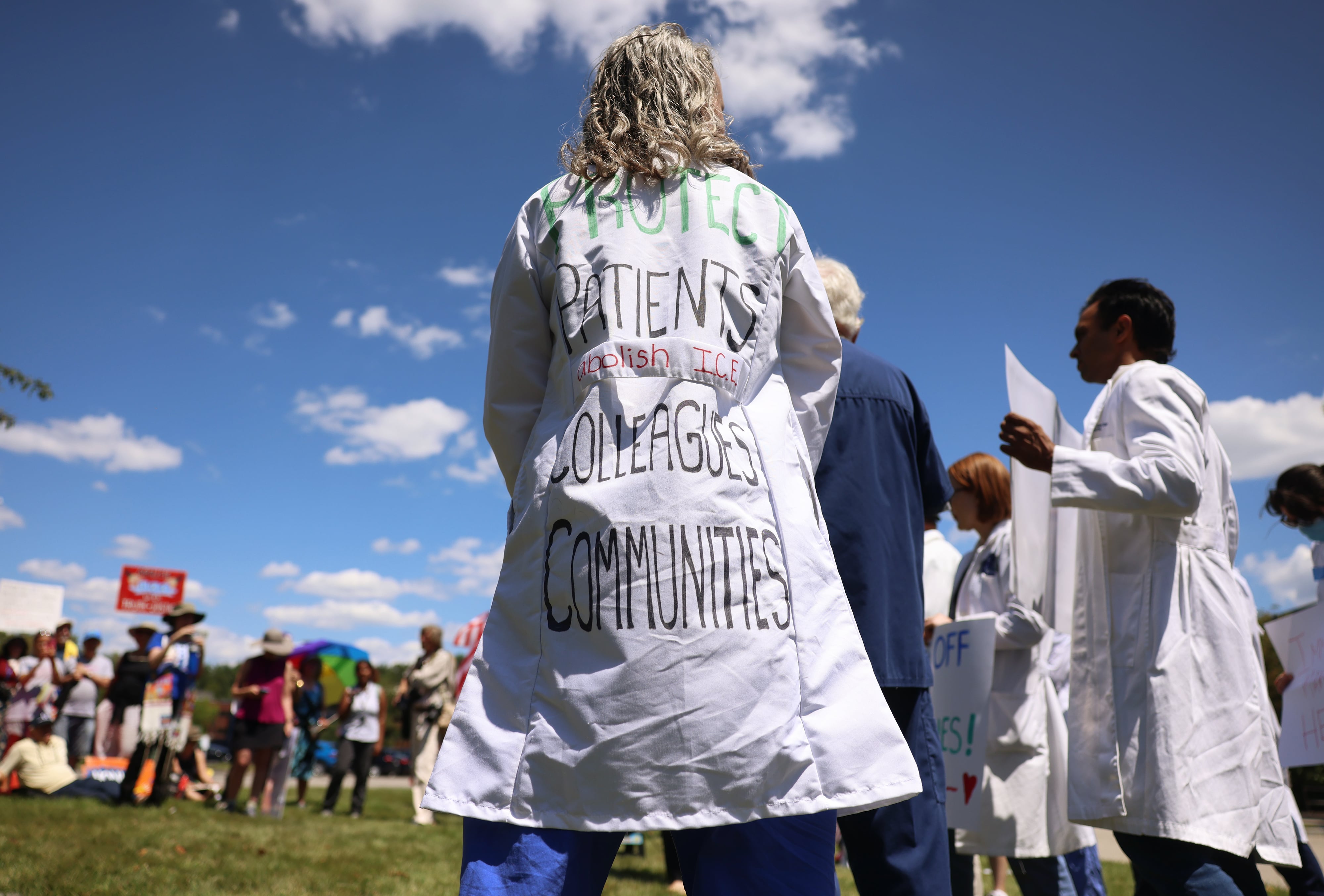

Several international health organizations have issued statements on this issue. The American Medical Association has guidelines against physicians participating in coercive interrogation or torture. The World Medical Association has statements about physicians' obligations when their government demands participation in harmful practices. The fundamental position across these organizations is consistent: healthcare workers should not participate in systems designed to harm people, and if required to do so, they should refuse and seek alternatives.

But that's easier to say than to do when you're a career federal employee with a family depending on your income. When your pension is vested over two decades and you've only worked there fifteen years, the personal cost of refusal is enormous. Stewart gave up a decade of service and the prospect of a pension she was just five years away from earning.

Resignations as Protest: Officers Leaving the Service

Some Public Health Service officers have concluded that resignation is the only ethical choice. These decisions don't come easily. They involve sacrificing years of career investment, pension benefits, and professional identity.

Stewart's resignation was particularly painful because she genuinely loved the work. She'd joined the Public Health Service because she believed in serving people in crisis. She'd deployed during hurricanes and public health emergencies. She'd found meaning in the work. But detention assignments crossed a line she couldn't ethically cross.

Bushman's resignation came with particular poignancy given her recent trauma. She was already grieving colleagues lost in a workplace shooting. Then she was told she'd be deployed to a facility she believed was inhumane. The combination was too much. She resigned rather than return to work under those circumstances.

Other officers have made the same decision in smaller numbers. They've given notice, often with letters explaining their ethical objections to detention work. Their departures have created staffing challenges for the federal government, which now has to recruit replacements for positions many officers find morally objectionable.

The resignations themselves carry symbolic weight. These are people who've dedicated their careers to federal service. They're not radical activists or people opposed to government. They're career healthcare professionals who've concluded that their government is asking them to do something they can't do in good conscience. The fact that career officials are resigning is itself a form of protest and a warning.

When people with tenure, pension eligibility, and secure federal employment resign over principle, it suggests the situation is genuinely intolerable. People don't lightly walk away from federal careers. The fact that some have demonstrates the depth of the moral crisis.

However, most officers haven't resigned. Many have remained in their positions. The reasons vary. Some believe they can provide the most good by staying and providing the best care they can within a flawed system. Others don't have the financial ability to resign, knowing they'll lose pension benefits. Still others accept the government's framing that providing medical care in detention is itself a form of service to vulnerable people.

But even among those who've remained, the effect of seeing colleagues resign isn't neutral. It plants questions. It creates doubt. It signals that these assignments are controversial enough that some people would sacrifice their careers to avoid them. Officers who remain are aware they're making a different choice, and that choice carries implicit acceptance of the system they're working within.

The number of detained immigrants in the U.S. has nearly doubled from 39,000 in 2017 to an estimated 71,000 in 2025, reflecting increased enforcement and detention policies. Estimated data.

The Officers Who Stayed: Bearing Witness in a Broken System

Not all Public Health Service officers have chosen resignation. Many have remained in detention facility assignments, despite moral reservations. Their reasons reveal the complicated calculus that makes these situations so difficult.

For some, the deciding factor is financial. A nurse midway through a federal career has already invested fifteen or eighteen years. Walking away means losing everything they've earned toward a pension. That's a devastating loss. If you have a family depending on your income, if you have medical conditions requiring ongoing healthcare, if you have financial obligations, resignation isn't a realistic choice. You're trapped.

For others, the deciding factor is a belief that their presence improves conditions. If they resign, someone else will take their place, someone who might be less committed to ethics, less careful, less willing to be an advocate for detainees. By staying, they believe they can mitigate harm. They can ensure medical care is provided. They can treat detainees with humanity even in an inhuman system.

One nurse described it this way: "I know this place is broken. I know the system is inhumane. But if I leave, it doesn't get less broken. Detainees still need medical care. I'm going to stay and do the best I can. I'll be a light in the darkness for the people I care for."

That's a compelling argument. But it also contains an implicit acceptance of the premise that detention itself is acceptable as long as it's done with humane care. Some ethicists disagree. They argue that participating in a system, even to mitigate its harm, is still complicity. By providing good care in detention facilities, officers are making the system seem more acceptable, more humane, more legitimate. They're enabling its continuation.

The officers who've remained experience what psychologists call "moral injury." They're asked to do work that conflicts with their deepest values. They comply because they feel they must, because the consequences of refusal are too severe. But the internal conflict takes a psychological toll. They see things that trouble them. They participate in practices they don't believe in. They come home and question what they did and why they allowed it to happen.

Some officers have attempted to document conditions and share their observations with oversight authorities. Public Health Service officers are supposed to be independent observers of federal agency health practices. That independence is supposed to make them a check on practices that violate health standards. But within the detention context, that independence is compromised. Officers are employees of the system they're supposed to monitor.

A few officers have attempted to speak with journalists or congressional staff about conditions they've witnessed. These conversations have been difficult. Many officers are afraid. They fear retaliation, loss of their security clearance, or discharge from the service. The fear is often justified. Federal employees who speak to the press about classified or sensitive information face potential prosecution under the Espionage Act. Officers who speak publicly about their work risk their careers.

Some officers have worked through proper channels, reporting through Inspector General offices or through their chain of command. But internal reporting often goes nowhere. The issues are policy-level. An officer can't force their agency to change detention practices through internal complaint mechanisms. The complaint just gets reported back up the chain to the very people making the policy.

The Silence of Detainees: Isolation and Information Control

One detail from officers' accounts stands out for its cruelty: some detainees didn't know they were at Guantánamo Bay until medical staff told them. Think about that. People were transported to a facility, held in a dark cell, and had no information about their location. They only learned they were at Guantánamo—a place with historical weight and infamy—when a healthcare worker mentioned it in passing.

This information control is systematic. Detainees have minimal access to communication. Phone calls are limited. Email access is rare. Mail is censored. The outside world essentially doesn't exist for detained people. They have no idea how long they'll be held, what will happen to them, or when they might be released.

This uncertainty itself is psychologically harmful. Humans need information to function psychologically. We need to know where we are, what's happening, and what to expect. When all of that is withheld, anxiety and paranoia develop naturally. It's not a disorder requiring treatment. It's a rational response to an irrational situation.

Many detainees haven't had meaningful contact with family members. Children don't know where their parents are. Spouses don't know whether they'll see their partners again. The separation combines with confinement to create multiple traumatic stressors. Officers describe detainees who've become depressed or dissociative, who show signs of giving up hope.

Some officers have attempted to improve communication. They've allowed phone calls when possible. They've helped detainees understand their legal status. They've provided information about their location, their situation, their rights. These small acts of transparency are radical in a detention system built on opacity.

But these individual efforts can't overcome the structural silence. The system is designed to isolate. Isolation prevents resistance, prevents organization, prevents detainees from understanding their situation well enough to advocate for themselves. Isolation also prevents the outside world from understanding what's happening. If detainees can't communicate with family, if family doesn't know what's happening, if there's no transparency, then the system operates in secret.

Public Health Service officers are sometimes the only people detainees interact with who aren't explicitly engaged in enforcement or confinement. That role gives them power. Detainees listen to what officers tell them. They trust medical professionals in ways they might not trust other institutional figures. This creates an opportunity for officers to provide accurate information, to demystify, to connect detainees to whatever resources exist.

But it also creates a burden. Officers become de facto counselors, therapists, information sources, and human connections in an otherwise dehumanizing environment. It's emotionally exhausting. Some officers describe it as the hardest part of their deployment, knowing they can provide only minimal help to people in severe distress.

Ethical concerns are the primary reason for resignation among Public Health Service officers, followed by psychological impact and career risks. (Estimated data)

Immigration Enforcement and Public Health: A Dangerous Merger

The use of Public Health Service officers in immigration enforcement represents a fundamental merger of two systems that shouldn't combine: public health and law enforcement. This merger creates problems at every level.

At the practical level, it erodes trust in public health institutions. When immigrants fear that seeking medical care will result in deportation, they avoid healthcare. They don't get vaccinated. They don't seek treatment for infections or chronic diseases. They don't take their children to doctors for preventive care. From a public health perspective, this is catastrophic. It undermines vaccination rates, allows communicable diseases to spread, and creates health crises.

Immigrants, documented and undocumented, are less likely to seek healthcare than citizens when they fear that seeking care will trigger enforcement action. That fear is well-founded. Immigration enforcement agencies have used hospital visits as opportunities for deportation arrests. They've stationed agents in hospital waiting rooms. They've demanded patient records from healthcare providers. The merger of health and enforcement creates rational fear.

When immigrants avoid healthcare, entire communities suffer. Vaccination rates drop. Communicable diseases spread. Preventable conditions become emergencies. Emergency rooms fill with people who didn't seek care earlier because they were afraid. The public health consequences of merger are clear: worse health outcomes, more disease, higher costs.

At the ethical level, the merger corrupts both systems. Healthcare providers are trained to be advocates for patients. But when healthcare systems are connected to enforcement, providers can't fully advocate. They're conflicted. They might want to help a patient, but they also know that helping might expose that patient to enforcement action. That conflict undermines the relationship between provider and patient.

Likewise, enforcement becomes corrupted. When enforcement agents use public health facilities as opportunities for apprehension, those facilities become less safe. People avoid them. The enforcement system becomes a tool of exclusion rather than justice. People are not detained based on criminal conduct but on their fear of healthcare systems becoming enforcement vectors.

Admiral Christine's statement attempted to address this by arguing that Public Health Service officers are simply providing healthcare, that their role is care provision, not enforcement. But that distinction is false. Officers deployed to detention facilities operate within an enforcement context. They're part of an enforcement apparatus. Their healthcare is provided to people in enforcement custody. The context is enforcement, regardless of how healthcare is framed.

The history of medical systems being weaponized against vulnerable populations is long and dark. From forced sterilizations to medical experimentation on enslaved people to racial disparity in healthcare access, medicine has been an instrument of oppression. Contemporary immigration detention should be understood in this context. It's not an aberration. It's a continuation of a pattern in which healthcare institutions are used to control and exclude vulnerable people.

The Department of Health and Human Services' Response: Administrative Erasure

When confronted with concerns from Public Health Service officers, the Department of Health and Human Services has responded with administrative language that acknowledges nothing and commits to nothing.

Admiral Christine's statement is a case study in institutional non-response. He frames the issue as one of duty and responsibility. Officers, in his view, have a duty to provide care. That duty is absolute. It doesn't depend on the context. It doesn't matter if the system they're participating in is inhumane. Their job is to show up and provide care.

This framing erases the actual moral questions. It treats medical care as a technical function separate from its context. But medicine doesn't operate that way. The ethics of providing medical care change dramatically depending on context. Providing care to someone injured in an accident is categorically different from providing care to someone being tortured. The tools might be the same. The ethics are completely different.

Christine also frames resignation as a form of virtue signaling, a prioritization of "subjective morality or public displays of virtue" over actual service to patients. The implication is that officers who resign are actually abandoning the people they claim to want to help. It's a clever rhetorical move. It makes resignation sound like abandonment.

But that's a false framing. Officers who resign aren't refusing to care for vulnerable people. They're refusing to participate in a system designed to harm vulnerable people. Those are different things. One could argue that participation in harmful systems is itself a form of abandonment of vulnerable people. By refusing to participate, officers are refusing to enable the harm.

The department has made no policy changes in response to officer concerns. No modifications to detention facility health standards. No requirements that officers be briefed on the conditions they'll encounter before deployment. No protections against deployment to facilities officers find morally objectionable. No additional mental health support for officers dealing with moral injury.

The department's response is essentially administrative silence. The official position is that officers have a duty. That duty is to care provision. Questions about context are not appropriate. The system will continue as it has been.

But the resignations continue. The moral concerns persist among remaining officers. The situation isn't stable. It's a pressure cooker. Eventually, something will give. Either the department will modify its policies and provide officers with meaningful choice about detention facility assignments, or it will continue to lose officers. The attrition will eventually reach critical levels where detention facility health operations become impossible to maintain.

Broader Implications: When Civil Service Becomes Complicity

This situation has implications that extend far beyond the Public Health Service. It raises fundamental questions about what it means when a government asks its civil servants to participate in practices those servants believe are wrong.

In a functioning democracy, civil servants maintain the ability to advocate for policy change through proper channels. They can raise concerns with supervisors. They can report to Inspectors General. They can contact Congress. These mechanisms exist to provide outlets for concerns without requiring resignation.

But these mechanisms only work if those in power actually respond to concerns. When the highest levels of government have decided on a particular policy direction, and that policy direction is being opposed by career officials, the proper channels often lead nowhere. The official raising the concern is just reporting to the people making the policy they oppose.

When that happens, civil servants face a genuine dilemma. Continue participating in something they believe is wrong, or resign and walk away from their career. There's no option for refusal or accommodation. Just participation or departure.

This dynamic has played out repeatedly in the Trump administration. Career officials have resigned from various agencies over policy disagreements. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has seen resignations from officers who disagreed with enforcement policies. The State Department has seen resignations from diplomats who disagreed with foreign policy decisions.

The Public Health Service resignations are significant because they're happening in an agency designed to be outside political conflict. Public health is supposed to be an area where professional expertise determines policy, not political ideology. Public Health Service officers aren't supposed to be partisan. They're supposed to be professionals focused on health.

But when political leadership directs those health professionals to participate in detention, the professional role becomes politicized. Officers can't separate their health expertise from the political context in which that expertise is being used. They're forced to choose between professional ethics and political loyalty.

The broader implication is concerning. If the government can require public health professionals to participate in detention, it can require them to participate in other policies those professionals find objectionable. It can require them to ignore environmental health hazards. It can require them to participate in forced medical interventions. It can require them to prioritize cost reduction over patient care.

Once the principle is established that government employees must participate in policies they find morally objectionable or else resign, the space for professional ethics within government collapses. Employees become purely administrative functionaries, implementing whatever policies their supervisors direct, with no ability to advocate for modifications or to refuse participation.

Detention and Psychology: The Mental Health Crisis

The psychological effects of detention are well-documented in the research literature. Immigration detention creates conditions that lead to predictable psychological harm, regardless of how good the medical care is within the detention facility.

Uncertainty is the first factor. Detainees don't know how long they'll be held. They don't know when they'll have a legal hearing. They don't know whether they'll be deported, released, or transferred. This uncertainty creates sustained anxiety and hypervigilance. The body remains in a stress state continuously, with no relief and no endpoint.

Isolation is the second factor. Detainees have limited access to communication with family, friends, or the outside world. They're separated from their normal support networks. Children are separated from parents. Spouses are separated from each other. This combination of isolation and separation creates grief and depression that accumulates over weeks or months.

Loss of autonomy is the third factor. Detainees have no control over their environment, their schedule, their medical care, or their legal proceedings. Everything is determined by authorities. This loss of control is associated with depression and learned helplessness.

When these factors combine, they create psychological crises. Officers describe detainees who've stopped eating, who don't get out of bed, who show signs of suicidal ideation. The detention environment itself is creating the psychological emergency, and healthcare workers are asked to treat it while being unable to address the underlying cause.

Some detention facilities have mental health crisis units. Officers provide suicide prevention, psychotropic medications, and short-term crisis intervention. But these are band-aids on a fundamental wound. The detention itself is the pathogenic factor. Medication might prevent immediate suicide, but it doesn't address the suffering that creates the suicidal impulse in the first place.

Research on indefinite detention shows that psychological symptoms appear predictably. Within days, anxiety increases. Within one to two weeks, depression appears. Within a month, psychological breakdown can occur. The longer detention continues, the worse the symptoms become. Detainees held for months develop symptoms indistinguishable from those found in torture survivors.

Public Health Service officers understand this. They have training in mental health. They know the research. They can see the symptoms developing in detainees. They're expected to treat those symptoms while the detention continues. It's like treating a patient for wounds while continuing to inflict those wounds.

The ethical status of this kind of medical care is questionable. Is it care if it enables continued harm? Is it care if it extends suffering by treating symptoms while allowing the cause of suffering to continue? Medical ethics would suggest that if you're aware of harm being inflicted, you're obligated to advocate for stopping that harm. You can't simply treat the symptoms and ignore the cause.

Comparisons to Historical Precedent: What Does History Tell Us?

Dena Bushman's reference to Nazi Germany might seem extreme, but it points to an important historical question: at what point does participation in a system designed to exclude or harm become complicity in that system? History provides examples.

During the Holocaust, German medical professionals participated in concentration camp operations. Some provided genuine medical care to prisoners. Others participated in medical experiments. All were part of a system designed to harm. In the postwar trials, the existence of some doctors who provided ethical care didn't negate the fact that the medical system itself was corrupted by its integration into a genocidal apparatus.

The Nuremberg Code emerged from these trials. It established principles for medical ethics that included informed consent, the right to withdraw from participation, and the principle that doctors should not participate in torture or persecution. The code emerged precisely because the international community recognized that medical professionals had been asked to participate in systems they shouldn't have participated in.

A less extreme but more relevant example might be the U.S. healthcare system's participation in slavery. Doctors and healthcare workers in slavery-era America provided medical care to enslaved people. Some of that care was intended to keep enslaved people healthy so they could work. Some was used to study diseases in enslaved populations without consent. Historians have documented how medical institutions became tools of slavery.

Post-slavery, the effects continued. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted from 1932 to 1972, involved the U.S. Public Health Service. The agency tracked untreated syphilis in African American men, without their consent or knowledge that they were part of a study. Even when treatment became available, the study continued. The men died of syphilis while researchers documented the disease's progression.

The Tuskegee Study is a direct precedent for Public Health Service participation in harmful systems. The agency has a documented history of using its authority to facilitate harm against vulnerable populations. When officers today are asked to deploy to immigration detention facilities, they're aware of this history. They understand that their agency has before used its authority in ways that caused harm.

These historical examples don't suggest that contemporary detention is equivalent to slavery or the Holocaust. The degree of harm is different. The intent is different. But they do suggest that there are patterns. Healthcare systems can become tools of control. Medical professionals can participate in harmful systems. The question of whether to participate, knowing the history, is not trivial.

Public Health Service officers who've resigned have cited this history implicitly or explicitly. They recognize that participation in detention, even if it's well-intentioned, represents a step toward normalizing the use of healthcare systems for enforcement and control.

The Path Forward: What Needs to Change

The current situation isn't stable. Officers are quitting. Morale is collapsing in some areas. The department hasn't addressed the underlying ethical issues. Something will have to give.

Several changes could address the crisis. First, the department could provide officers with genuine choice about detention facility assignments. This would mean allowing officers to opt out of detention work without penalty. It would mean not reassigning them to different detention facilities as a workaround. It would mean that participation in detention would be truly voluntary.

Virtually every officer would likely volunteer for hurricane or disaster relief work. Very few would voluntarily accept detention facility assignments. The result would be that detention facilities would have a much smaller pool of available healthcare professionals. That might seem like a problem. But the underlying reality is that the current system is built on compulsion. It requires forcing people to participate in something they don't want to do. A system that depends on compulsion should change its practices rather than compel participation.

Second, the department could establish minimum health standards for detention facilities that go beyond what currently exists. These could include requirements for mental health services, access to communication with family, light exposure, sleep protection, and other standards that address the conditions officers have described. Independent oversight of these standards, with authority to investigate and report violations, would be necessary.

Third, the department could provide officers who do accept detention assignments with full briefing about conditions before deployment, actual choice about whether to proceed after that briefing, and ongoing psychological support for officers dealing with moral injury. This would acknowledge the difficulty of the work and provide support rather than denying the problem exists.

Fourth, the department could advocate internally for policy changes. Rather than simply implementing detention health policies as directed, leadership could push back against policies they recognize as harmful. They could argue that detention under current conditions violates medical ethics. They could recommend changes. This might not succeed, but it would at least signal that career healthcare professionals are advocating for improvements.

Fifth, Congress could establish conditions under which federal healthcare workers can be deployed to detention facilities. These could include minimum health standards, independent oversight, and requirements for officer consent. Congressional action would circumvent potential executive resistance to policy changes.

None of these changes will happen quickly or easily. The current administration appears committed to aggressive detention policies. Immigration enforcement is a priority. If healthcare standards are relaxed or if detention facilities are required to meet stricter health standards, that could be seen as limiting detention capacity, which would be opposed by those who want expanded detention.

But the pressure will mount. Each resignation signals that the current system is unsustainable. Each officer who quits is an officer lost from the Public Health Service's overall capacity. Eventually, the attrition will reach critical levels. Detention facilities will have inadequate healthcare. Officers remaining will face even worse conditions and more impossible choices. The system will collapse under its own contradictions.

That collapse might be the only thing that forces change. Absent a crisis, the department can continue its current approach. But the crisis is building. Officers are voting with their feet. They're leaving rather than participate. Eventually, the exodus will be impossible to ignore.

FAQ

What is the U.S. Public Health Service and why are its officers being deployed to immigration detention?

The Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service is a uniformed healthcare workforce of approximately 6,000 doctors, nurses, and other health professionals. Unlike private healthcare workers, these officers operate under a military-style chain of command and can be deployed by the federal government to various agencies during emergencies or to fill staffing gaps. The Trump administration has begun deploying them to Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facilities, including the newly-repurposed immigration detention operation at Guantánamo Bay, to provide healthcare to detained immigrants.

Why are public health officers resigning over detention assignments?

Several officers have resigned because they believe detention facilities operate under conditions that violate medical ethics and cause severe psychological and physical harm to detainees. Officers describe dark cells, sleep deprivation, isolation from family, psychological trauma, and minimal mental health support. Healthcare professionals argue that participating in such systems, even while providing medical care, makes them complicit in harm. For some, like Rebekah Stewart, the moral conflict became intolerable enough to sacrifice a career and pension.

Can Public Health Service officers refuse to deploy to detention facilities?

Theoretically, officers could refuse orders, but practically, refusal carries severe consequences. Deployments within the Commissioned Corps operate on a military model where orders are expected to be followed. Refusal could result in discharge, loss of pension benefits, and career termination. When officers have attempted to avoid problematic deployments, they've often been reassigned to other detention facilities rather than excused from detention work entirely. The system creates effective compulsion rather than genuine choice.

What are the actual conditions like inside immigration detention facilities at Guantánamo Bay?

According to accounts from Public Health Service officers, conditions at Camp 6 in Guantánamo Bay include dark cells where sunlight doesn't penetrate, continuous lighting that prevents sleep, overcrowding, minimal access to communication with family, and extremely limited information about legal status or duration of detention. Officers describe detainees suffering from severe anxiety, depression, insomnia, and psychological breakdown. Some detainees reportedly didn't know they were in Cuba until medical staff mentioned it. The facility was originally designed to hold terrorism suspects and was repurposed for immigration detention without significant modifications.

How many people are currently detained in immigration facilities, and what charges do they face?

Approximately 71,000 immigrants are currently detained in U.S. immigration facilities. Critically, most have no criminal record. Detention is based purely on immigration violations, such as crossing the border without authorization or overstaying visas. At Guantánamo Bay specifically, a chaplain's progress report indicated that approximately 90 percent of detainees were classified as "low-risk," contradicting claims that the facility houses "the worst of the worst." The vast majority of detained people face no criminal charges.

What does the Department of Health and Human Services say about these deployments?

Admiral Brian Christine, the assistant secretary for Health at the Department of Health and Human Services, has stated that Public Health Service officers have a duty to "show up, provide humane care, and protect health" regardless of context. He argues that providing medical care itself is a form of service to vulnerable people, and that officers who prioritize objections to detention policies are prioritizing "subjective morality" over actual service. The department has made no policy changes in response to officer concerns and has not modified detention health standards or provided officers with choice about detention assignments.

What are the psychological effects of immigration detention on detainees?

Research shows that indefinite detention under conditions of uncertainty, isolation, and loss of autonomy creates predictable psychological harm. Anxiety appears within days. Depression develops within one to two weeks. Prolonged detention creates psychological symptoms comparable to torture survivors. Detainees experience trauma from separation from family, uncertainty about their legal status and duration of detention, and the psychological effects of confinement. Mental health services within detention facilities can treat acute crises but cannot address the underlying cause of suffering.

How does the merger of public health and immigration enforcement affect immigrant communities' healthcare-seeking behavior?

When immigrants fear that seeking medical care will result in deportation, they avoid healthcare. They don't get vaccinated. They don't seek treatment for infections or chronic diseases. They avoid taking children to doctors for preventive care. From a public health perspective, this merger erodes the trust necessary for public health systems to function. Immigration has documented cases of immigration agents stationed in hospital waiting rooms and using hospital visits as opportunities for deportation arrests. This connection between healthcare and enforcement creates rational fear that undermines public health.

What historical precedents exist for healthcare systems being used for control or harm?

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972, involved tracking untreated syphilis in African American men without their consent or knowledge. Even when treatment became available, the study continued and men died of syphilis while researchers documented disease progression. The U.S. also has a documented history of forced sterilizations and medical experimentation on vulnerable populations. These precedents inform current concerns about whether public health systems should participate in detention and enforcement.

What changes would address the ethical concerns around Public Health Service deployment to detention?

Potential changes include providing officers with genuine choice about detention assignments without penalty, establishing minimum health and mental health standards for detention facilities with independent oversight, briefing officers about conditions before deployment and allowing them to decline after being informed, providing psychological support for officers dealing with moral injury, and having healthcare leadership advocate for policy changes that align detention with medical ethics. Congressional action could establish conditions for deployment. However, these changes would likely reduce detention capacity, which the current administration opposes.

Conclusion: The Cost of Complicity

Rebekah Stewart gave up her dream job. After a decade of service, after believing deeply in the mission of the Public Health Service, she resigned rather than participate in what she saw as a humanitarian crisis. Dena Bushman, grieving colleagues lost in a workplace shooting, resigned rather than accept deployment to a detention facility. Other officers have made similar choices.

These resignations matter. They're not political gestures. They're not abstract principle. They're experienced healthcare professionals saying that the line has been crossed. They can't do this. They won't do this. The cost of their careers is worth less than the cost of their participation in this system.

The Trump administration will likely respond to these resignations by recruiting replacement officers, offering better incentives, or simply assigning more officers to detention work. The administration is committed to immigration enforcement and detention expansion. A few officer resignations won't change that direction.

But the resignations create a baseline. There's a limit to what healthcare professionals will do. That limit has been reached. Future administrations should understand that asking healthcare professionals to participate in conditions healthcare professionals consider inhumane will result in the loss of those professionals. That attrition eventually becomes operational.

The broader question is about what we're willing to normalize. When healthcare workers are required to participate in detention, we're saying that detention is acceptable, even desirable. We're integrating healthcare into the detention apparatus. We're saying that medical care in detention conditions is sufficient, that the conditions themselves aren't the problem. We're saying that as long as people have healthcare, how they're treated is acceptable.

Historically, this normalization has not ended well. Healthcare systems that become tools of state control tend to expand their scope. Once detention is accepted, forced treatment can follow. Once forced treatment is accepted, forced sterilization can follow. Once forced sterilization is accepted, medical experimentation without consent can follow. There's a trajectory here, and it doesn't lead to a good place.

Stewart, Bushman, and the other officers who've resigned are trying to prevent that trajectory. They're drawing a line and saying that healthcare has limits. Healthcare exists to heal, not to enable harm. When healthcare is asked to participate in systems designed to harm, healthcare has been corrupted. That corruption won't be fixed by providing good medical care within those systems. It will only be fixed by refusing to participate.

The question now is whether their resignations will matter. Will the federal government modify its policies and provide officers with genuine choice about detention assignments? Will it establish health standards that address conditions officers have described? Or will it continue as it has been, losing officers and accepting the cost?

The answer will depend on political leadership. But the pressure is building. Each officer who quits is a signal that the system is unsustainable. Eventually, that pressure will force change, one way or another. Either through policy modification or through the collapse of detention facility healthcare operations.

For now, detained immigrants continue to be held in conditions that healthcare professionals find inhumane. Public Health Service officers remain in those facilities, providing the best care they can while working within a system they believe is fundamentally broken. And some officers have chosen to walk away, sacrificing their careers rather than participate.

Their choice matters. History will judge whether the rest of us made different choices, and whether those choices were defensible.

Key Takeaways

- Public Health Service officers are resigning after being ordered to deploy to immigration detention facilities, including Guantánamo Bay

- Healthcare workers describe conditions including dark cells, sleep deprivation, isolation from family, and severe psychological trauma

- Approximately 71,000 immigrants are detained in U.S. facilities, with roughly 90% at Guantánamo classified as low-risk, contradicting official claims

- The merger of healthcare and immigration enforcement creates an impossible ethical conflict for medical professionals bound by duty to patients

- Officers face genuine compulsion due to pension loss and career termination if they refuse deployments, making resignations acts of significant personal sacrifice

Related Articles

- ICE Out of Our Faces Act: Facial Recognition Ban Explained [2025]

- Elon Musk's $150M SEC Lawsuit: Why Trump Won't Back Him [2025]

- ICE Domestic Terrorists Database: The First Amendment Crisis [2025]

- Detained by Federal Agents: Inside Immigration Enforcement [2025]

- Inside Federal Immigration Enforcement: Agent Concerns & Operational Reality [2025]

- Minneapolis Tech Community Responds to Immigration Crisis [2025]

![Public Health Workers Resigning Over ICE & Guantánamo Assignments [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/public-health-workers-resigning-over-ice-guant-namo-assignme/image-1-1770377984636.jpg)