The Bear in Central Park: A Decade-Old Mystery Finally Solved

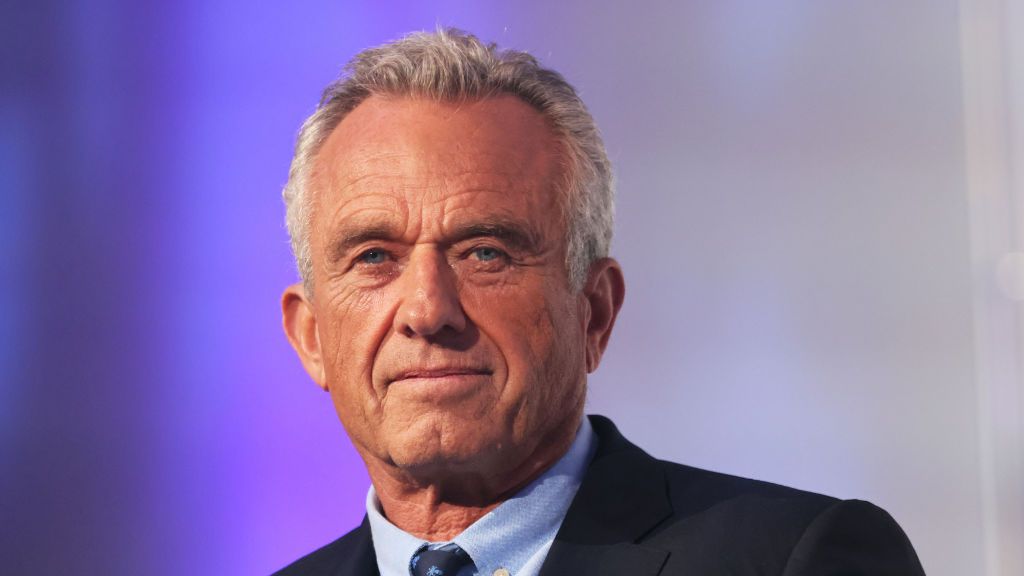

In October 2014, a decomposing bear cub was discovered under a bush near West 69th Street in Central Park. For a decade, New York City officials puzzled over how a wild black bear—an animal native to upstate New York but virtually unheard of in Manhattan in recent memory—had ended up dead in the city's most famous park. The mystery remained unsolved, whispered about in emails between city workers and wildlife officials, until August 2024 when Robert F. Kennedy Jr. posted a video on social media admitting he had placed the dead animal there as a prank, as reported by Wired.

Kennedy claimed he was trying to make the bear's death look like a bicycle accident to see if the story would fool people. This explanation sparked outrage, questions about his judgment, and a deeper dive into what actually happened. Now, public records obtained by journalists reveal documents that city officials never intended for public scrutiny, exposing not just the bizarre nature of Kennedy's prank, but the very real work that fell to underpaid park rangers, wildlife biologists, and administrative staff who had to document, handle, and investigate the remains of a young animal.

The story matters for several reasons. It illuminates how a single careless act by someone with access and resources creates cascading problems for public servants. It raises questions about wildlife management in urban areas. And it demonstrates how public records requests can pull back the curtain on incidents that powerful people might prefer to forget. The documents—email chains, field reports, forensic analysis, and investigative summaries—paint a picture of confusion, concern, and careful professional work done by people trying to understand what had happened.

But beyond the immediate incident, this case touches on larger issues: animal welfare in cities, the responsibilities of people who encounter wildlife, and what happens when someone with Kennedy's profile treats a serious matter as entertainment. The bear itself represents something worth understanding, not just as a curiosity, but as a real animal with a brief life cut short by trauma, and a death that left questions hanging over a public space for ten years.

TL; DR

- Kennedy's admission: In August 2024, RFK Jr. confessed to dumping a dead bear cub in Central Park in 2014 to create a fake bicycle accident scenario for entertainment

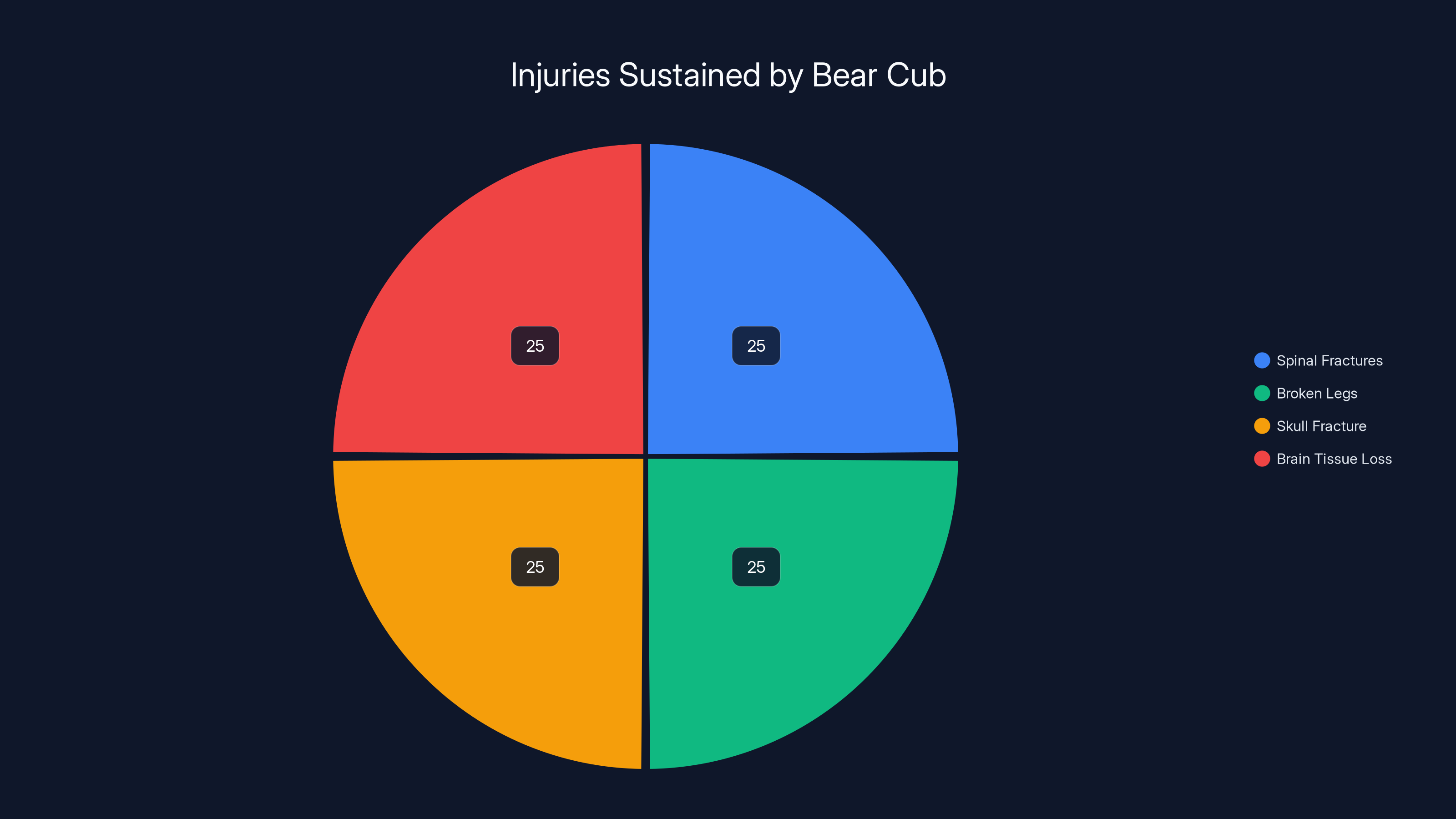

- Animal suffering revealed: Forensic necropsy showed the female cub (7-8 months old) died from massive blunt force trauma with catastrophic injuries including a shattered skull

- Public servant burden: Email chains show NYC Parks, NYPD, and wildlife officials coordinated intensive investigation and documentation work to handle the remains

- Investigation findings: New York Department of Environmental Conservation concluded the bear was likely hit by a vehicle along the Thruway near the state border, not in Central Park

- Bottom line: Records reveal both Kennedy's recklessness and the professional diligence of public officials forced to clean up after it

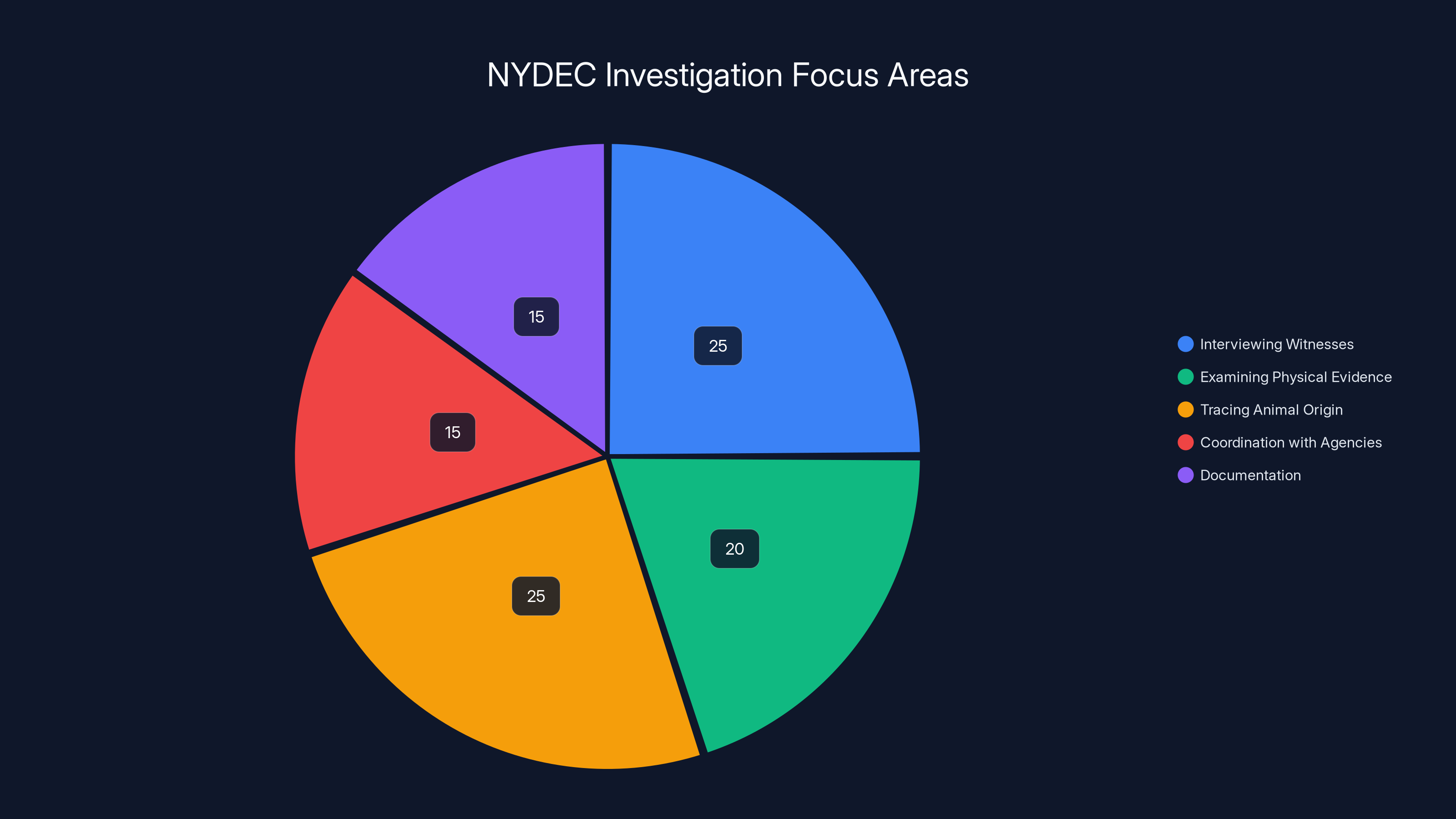

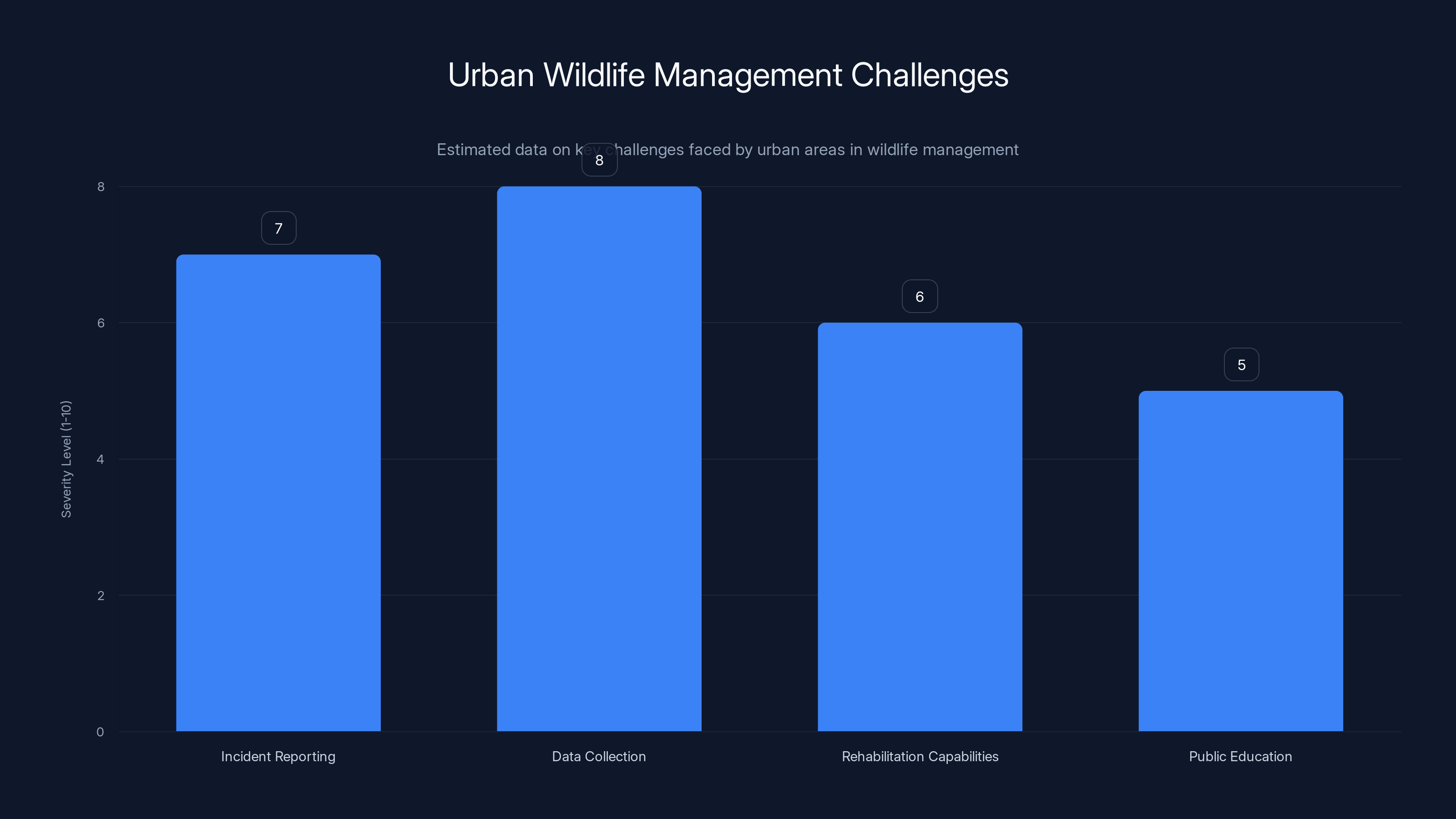

Estimated data shows NYDEC's investigation efforts were evenly distributed across interviewing, examining evidence, and tracing the bear's origin, with additional focus on coordination and documentation.

Timeline of the Discovery: October 6, 2014

On a Monday morning in early October 2014, someone contacted the Central Park Conservancy about an unusual sight near West 69th Street. A small, dark shape was visible under a bush. The conservancy's community relations director, Caroline Greenleaf, notified Urban Park Rangers (UPR), the professional law enforcement agency that patrols Central Park and handles wildlife incidents.

The first official communication about the bear arrived in the inbox of Bonnie Mc Guire, then-deputy director of Urban Park Rangers, at 10:16 a.m. on October 6. UPR Sergeant Eric Handy had called her with the news: they'd found a dead black bear. The response was immediate and professional. The NYPD was contacted and treated the scene like a potential crime scene, which meant the park rangers couldn't handle the body without proper oversight. Mc Guire asked Handy to photograph the animal and keep the command informed of developments.

What's striking in the email communications is the staff's genuine concern and puzzlement. Mc Guire wrote "Poor little guy!" in one message, an expression of sympathy for an animal whose death seemed senseless. Handy updated colleagues throughout the day with observations and next steps. By afternoon, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation had arrived, and officials were coordinating transfer of the remains to be examined by specialists.

The coordination that followed involved multiple agencies and departments. The initial plan was to take the bear to the Bronx Zoo for inspection by the NYPD's animal cruelty unit and the ASPCA. This didn't happen—instead, the NYDEC transported the bear to a state laboratory facility near Albany for detailed analysis. What everyone involved seemed to understand, even at that early stage, was that this wasn't a routine occurrence. One email describes it simply: "Definitely a first for Central Park."

Greenleaf, from the Central Park Conservancy, expressed her own interest in the results. In her reply to Handy, she wrote that she'd be "very interested in hearing the necropsy results." Handy agreed. The next morning, he replied: "Definitely strange." That word kept recurring in the communications. Strange, unusual, unexpected—adjectives that captured how anomalous the discovery felt to everyone involved.

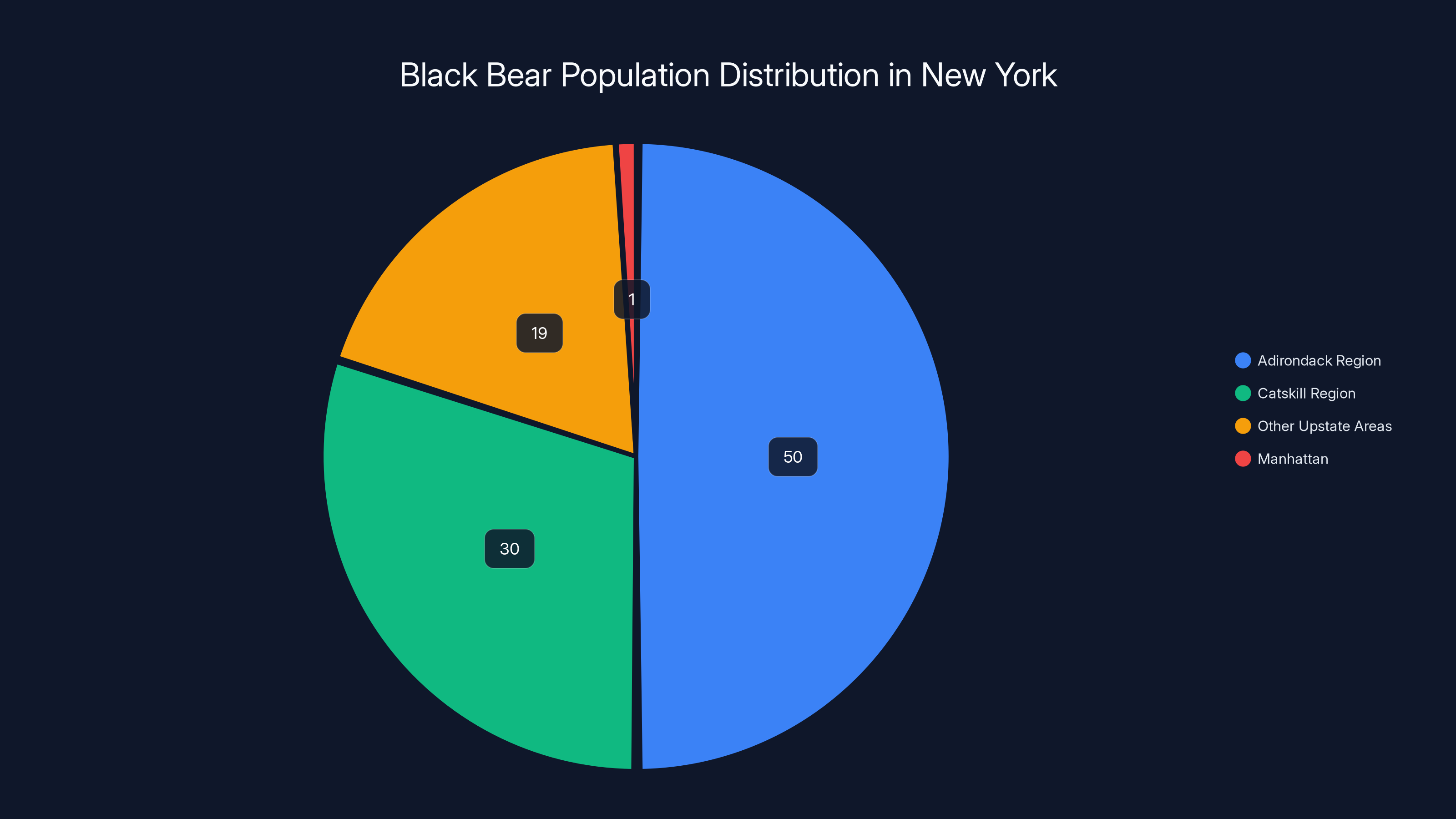

Estimated data shows that the majority of black bears in New York reside in the Adirondack and Catskill regions, with negligible presence in Manhattan.

The Forensic Examination: What the Necropsy Revealed

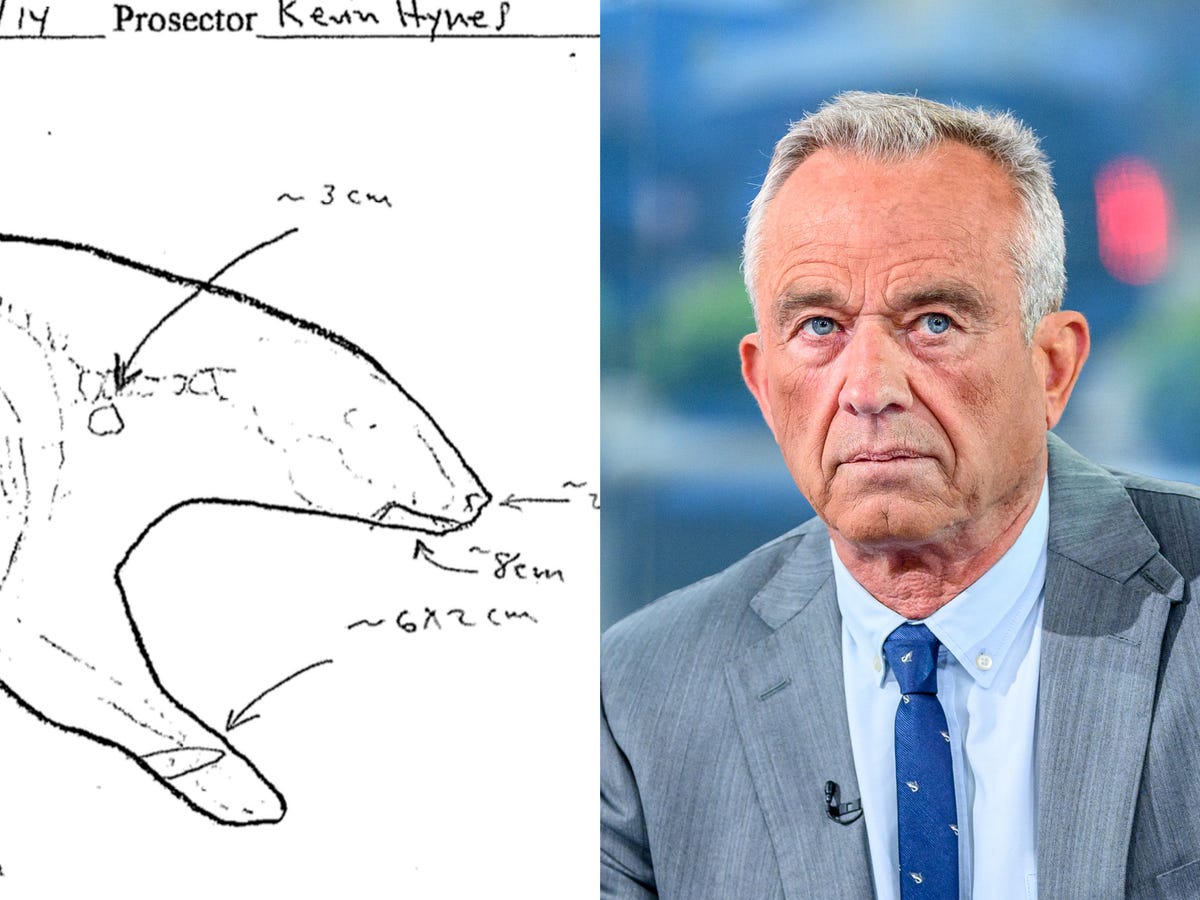

On October 7, 2014, the day after discovery, wildlife biologist Kevin Hynes from the NYDEC conducted a detailed examination of the bear cub. What he found was horrifying in its specificity. The animal had suffered massive blunt force trauma—the kind of injury consistent with being hit at high speed by a vehicle. The injuries were comprehensive and devastating: spinal fractures, all four legs broken, and a skull fractured so severely that "the majority of its brain" had been lost through its mouth.

The necropsy report, obtained through public records requests, provided clinical details that made the manner of death unmistakably clear. Brain tissue wasn't just found in the bear's mouth—it was also present in the trachea and upper bronchus. The remaining brain tissue was described in technical language as "scrambled, liquefied, and hemorrhagic." These aren't the kind of injuries an animal sustains from a fall or impact with a bicycle. These are injuries from a high-speed vehicle collision.

Hynes also determined the cub's age: seven to eight months old. It was female. And a DEC report noted something that made the tragedy more acute: prior to her death, she "was healthy and eating natural sources of food." This wasn't a sickly animal that was suffering. It was a young bear that had survived almost a year in the wild before meeting a sudden, violent end.

Based on the physical evidence and understanding of the bear species' range, NYDEC investigators hypothesized that the cub was struck by a vehicle, likely along the lower Route 87 portion of the New York State Thruway, possibly around the New York/New Jersey border in Rockland or Orange County. This placed the actual death location dozens of miles from Central Park—making Kennedy's decision to transport the body to Manhattan even more deliberate and bizarre.

The forensic analysis also addressed something that became a point of public discussion in 2024: photographs showing Kennedy with his hand inside the dead bear's mouth. The necropsy report explains why this was possible. The catastrophic skull fractures and loss of brain tissue meant the mouth opening was significantly altered. The photographs, which Kennedy seemed to view as lighthearted evidence of his prank, were actually documentation of severe animal trauma.

Why Kennedy Dumped the Bear: His Own Explanation

Kennedy's explanation for his actions, when finally revealed in 2024, was almost more puzzling than the incident itself. He said he placed the dead bear in Central Park because it would be "fun" to see if people would believe it was hit by a cyclist. The statement suggested he viewed the exercise as an elaborate prank—a test of his ability to create a convincing false scenario and see who would fall for it.

In his August 2024 video posted on social media, Kennedy framed the revelation as him getting ahead of a story that The New Yorker was about to publish about the incident. He decided to admit to his involvement before journalists could report it, controlling the narrative by presenting it as a lighthearted anecdote from his past rather than a serious incident. This preemptive admission strategy—essentially confessing before being caught—was a calculated move to shape how the story would be received.

What Kennedy's explanation lacked was any apparent recognition of the serious implications of his actions. He didn't address the resources expended by city employees. He didn't acknowledge the animal welfare concerns or the fact that a young bear had suffered a horrific death. He didn't explain how he obtained the bear's body or the logistics of transporting it to Manhattan. The tone he adopted was one of bemusement, as if the whole thing was a clever joke he'd played a decade earlier and was only now ready to share with his audience.

This framing—treating the incident as entertainment, as something amusing—was precisely what prompted outrage when the story went public. City officials who had invested time and professional expertise investigating the bear's death suddenly understood they'd been dealing with the aftermath of a prank. The woman who expressed sympathy for the "poor little guy" in her email had been unknowingly participating in the cleanup after a deliberate act by someone who saw the whole situation as a lark.

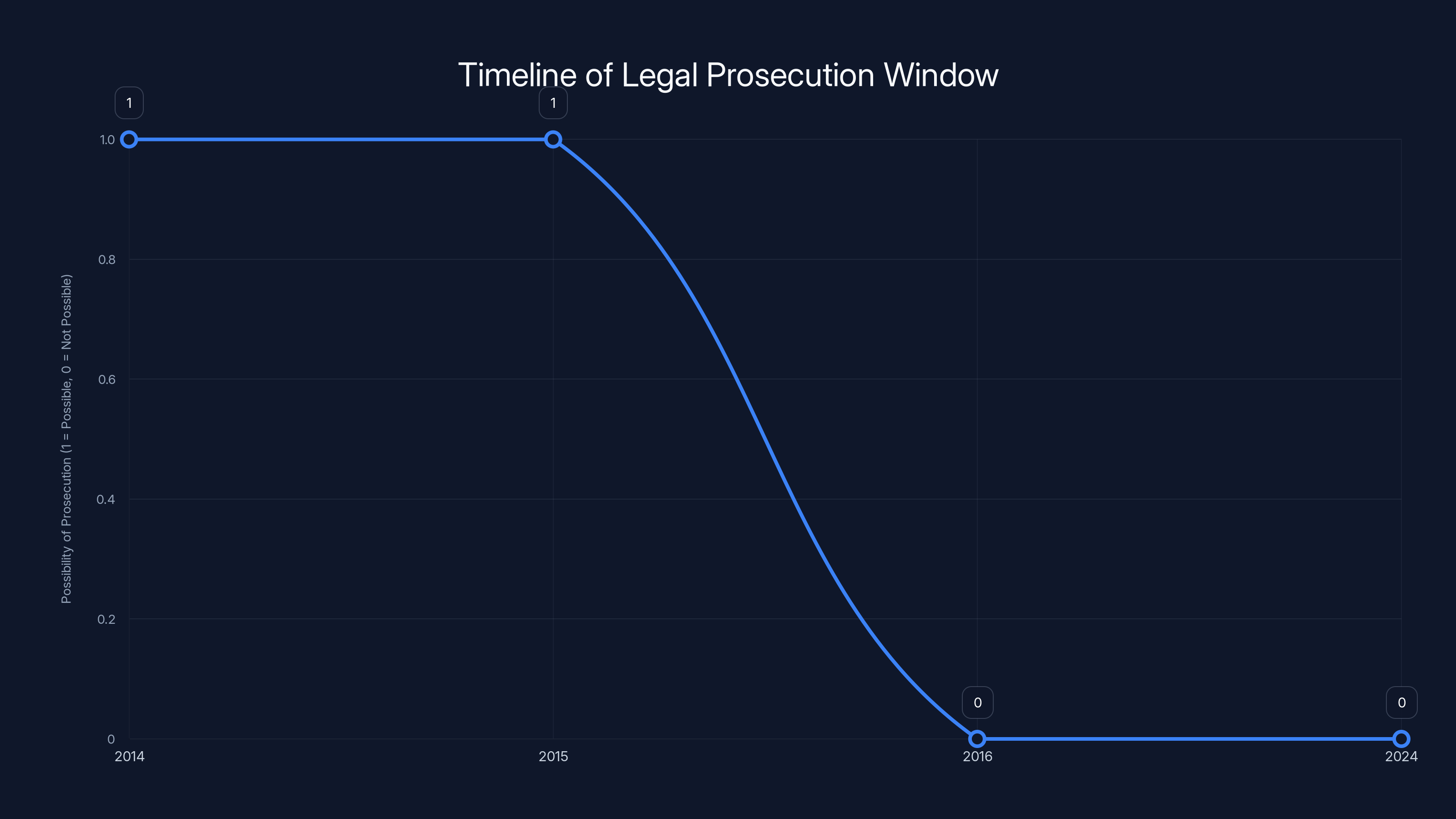

The statute of limitations in New York provides a one-year window for prosecuting wildlife violations. By confessing in 2024, Kennedy was beyond this legal timeframe, making prosecution impossible.

The Investigation: How NYDEC Handled the Case

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation took the lead on the forensic investigation, recognizing that a dead bear in Central Park raised questions about wildlife crime, illegal possession, and improper disposal of protected animals. Under New York environmental conservation law, both illegal possession of a bear without proper tags or permits and illegal disposal of bear remains are violations. The statute of limitations for these offenses is one year.

Since Kennedy didn't confess until 2024, well outside the one-year window, any potential prosecution was automatically barred by time. But NYDEC still conducted a thorough investigation in 2014 because they didn't know the circumstances. They needed to determine whether this was poaching, illegal trafficking of wildlife, or something else entirely. The investigation involved specialists, field work, coordination with other agencies, and careful documentation.

In their official investigation summary, NYDEC noted that they worked to determine whether state law had been violated and to understand how a bear cub came to be in Central Park. They interviewed people at the scene, examined the physical evidence, and attempted to trace where the animal came from. The investigation ultimately concluded in late 2014 "due to a lack of sufficient evidence" to determine if state law had been violated. Without knowing Kennedy had placed the bear there deliberately, investigators couldn't determine the specific crime involved.

When asked about the matter years later, NYDEC spokesperson Jeff Wernick stated that the department's investigation had been closed and that the statute of limitations had expired for any violations that might have occurred. This technical response masked a larger truth: the investigation had been thorough and professional, conducted by specialists who understood both wildlife forensics and environmental law. The fact that it led nowhere wasn't a failure—it was simply the reality of investigating an incident where the perpetrator remained unknown.

The investigation process itself consumed resources. NYDEC wildlife health biologist Kevin Hynes spent time examining the remains. Law enforcement officers compiled reports. Administrative staff coordinated with multiple agencies. And all of this work was predicated on not knowing the full story. It's a reminder that when people disregard consequences and treat serious matters as entertainment, they're creating work and confusion for professionals tasked with understanding what happened.

The Urban Park Rangers: First Responders to an Anomaly

Urban Park Rangers are the law enforcement professionals responsible for protecting New York City's parks and the wildlife within them. They undergo training in animal handling, emergency response, crime scene preservation, and environmental protection. When Sergeant Eric Handy received the call about a dead bear in Central Park, he was dealing with something unprecedented in his professional experience.

Handy's approach to the situation was methodical and professional. He took photographs of the bear where it lay, documenting the scene before anything was disturbed. He coordinated with the NYPD, recognizing that a dead animal in the park needed to be treated carefully, particularly given the unusual nature of the discovery. He communicated with his supervisor, kept colleagues informed, and facilitated the transfer of the animal to proper forensic examination.

The emails show Handy working alongside another ranger, identified as "A. Ioannidis," in examining the bear on scene. They noted the injuries to the animal's body, rear legs, and jaw. They made preliminary observations—"Further inspection of the hour seems to indicate bear was hit by a car"—that would later be confirmed by expert forensic analysis. Their fieldwork was careful and thorough, the kind of detailed observation that makes forensic investigation possible.

What's often overlooked in high-profile incidents is the work of these first responders. Handy and Ioannidis were doing the job they were trained for, handling an unusual situation with professionalism. They didn't know at the time that they were dealing with the aftermath of a prank. They were treating it as a legitimate investigation requiring proper documentation and care. This is the nature of professional work—you execute your responsibilities properly even when you don't have the full context.

The Rangers also worked with Greenleaf from the Central Park Conservancy, expressing thanks for the tip that led them to discover the bear in the first place. The exchange of emails between Handy and Greenleaf suggests a working relationship built on mutual respect. When Greenleaf expressed interest in the necropsy results, Handy acknowledged the shared curiosity about an unprecedented discovery in the park.

The necropsy revealed the bear cub suffered severe injuries, with spinal fractures, broken legs, and a skull fracture each contributing equally to the trauma. Estimated data based on description.

The Bureaucratic Aftermath: Emails and Coordination

The discovery of the bear cub required coordination across multiple city agencies, each with distinct responsibilities and expertise. The emails obtained through public records requests reveal how this coordination actually works in practice—it's neither seamless nor chaotic, but rather a process of communication, clarification, and working toward a shared goal of understanding what had occurred.

Mc Guire's role as deputy director of Urban Park Rangers meant she was receiving updates and making decisions about next steps. When she learned about the bear, her immediate actions were appropriate to the situation: get photographs, maintain documentation, coordinate with other agencies, and keep leadership informed. She understood that this wasn't a routine matter. The bear's presence in Central Park was inherently newsworthy and required careful handling.

The emails show a pattern of professional communication. People updated each other. They asked questions. They coordinated timing and logistics. They expressed appropriate concern—both for the animal and for the implications of its discovery. When something unusual happens, organizations create paper trails documenting what was done and why. These records become invaluable years later when people want to understand what actually occurred.

What's also evident is the scale of coordination required for what might seem like a simple matter. A dead animal in a public park isn't something that one agency can simply handle alone. There are crime scene considerations (why else was NYPD involved?). There are wildlife concerns (requiring NYDEC expertise). There are public relations implications (hence the Conservancy's involvement). There are public health considerations. Multiple organizations have legitimate reasons to be involved, and their involvement creates communication overhead.

This is the hidden cost of irresponsible behavior by private citizens. Kennedy's decision to dump the bear created a coordination problem for multiple public agencies. People had to be notified. Meetings had to happen. Reports had to be filed. Photography had to be taken. Analysis had to be conducted. Administrative personnel had to process information and maintain records. All of this consumed time and resources, which ultimately come from taxpayers.

The Wildlife Biology: Understanding Black Bears in New York

Black bears are native to New York State, but their presence in Manhattan in the 21st century is vanishingly rare. The species was historically common throughout the Northeast before European settlement, but habitat loss and human expansion dramatically reduced their range. In modern times, black bears live primarily in upstate New York, particularly in the Adirondack and Catskill regions. A bear cub in Central Park is so anomalous that it's legitimate for park officials to treat it as an emergency.

The bear found in Central Park in 2014 must have originally been born in the wild somewhere in upstate New York, most likely in bear country north or west of the city. She survived approximately seven to eight months—from late February or early March through early October. This is a vulnerable age for bear cubs. They're weaned around six months old but still dependent on maternal guidance and protection. Without their mother, they're susceptible to predation and accidents.

Wildlife biologists would later hypothesize that this cub was likely separated from her mother—either through death of the mother or other circumstances that left her alone. How she ended up in Kennedy's possession remains unexplained. Did he encounter her in a weakened state somewhere upstate and bring her with him? Did he obtain her illegally? The story he told doesn't address these questions.

What's clear is that the cub was hit by a vehicle with enough force to cause the catastrophic injuries documented in the necropsy. The impact was severe enough to fracture her spine, break all four legs, and shatter her skull. This wasn't a minor collision or a glancing blow. This was a high-speed vehicle strike that killed the animal instantly or within seconds. For a young bear that had survived eight months in the wild, the end came violently and suddenly.

The presence of the bear's body in Central Park created ecological and safety concerns. Dead animal carcasses attract scavengers and can harbor disease. In an urban park used by thousands of people daily, the body posed potential public health and safety risks. The decision to remove it, examine it, and ultimately dispose of it properly was made necessary by the fact that it was there—not by any inherent characteristic of the bear itself, but by human behavior.

The investigation into the bear incident saw initial activity in 2014 but quickly stalled due to lack of evidence, maintaining a low level of attention over the following years. Estimated data.

The Cover-up That Wasn't: Why Did It Take Ten Years to Surface?

One of the most puzzling aspects of the incident is why it remained largely unknown for a decade. Kennedy attended high school in the New York area and spent considerable time in the region. If he was involved with the bear, why didn't the story come out earlier? What prevented journalists or investigators from connecting the dots?

The answer lies partly in the investigation's conclusion that there was insufficient evidence to determine what happened. Without a clear understanding of how the bear came to be in Central Park, investigators had limited avenues to pursue. Park rangers found an animal. Forensic analysis indicated it had been hit by a vehicle. The most likely scenario was that the cub had been struck somewhere along a highway and someone had transported it to the park for reasons unknown.

Without witnesses or evidence pointing to a specific person, the case simply stalled. NYDEC didn't have leads to follow. The case remained open in terms of the investigation, but active investigative work likely ceased once initial analyses were complete and no obvious crime emerged. The file sat in archives, accessed occasionally when someone did research on the incident but not generating new investigative momentum.

Kennedy likely kept the story to himself or shared it only with a close circle. It wasn't the kind of thing he would broadcast publicly—placing a dead bear in Central Park could be characterized as animal cruelty, improper disposal of protected wildlife, and disrupting a public space. These aren't crimes that people voluntarily confess to when they're trying to maintain a public reputation. Kennedy was involved in environmental and public health advocacy, which made his involvement in the bear incident even more contradictory to his public persona.

So for ten years, the mystery persisted. News articles from 2014 covered the discovery and the initial investigation, but without a resolution, the story faded. Park rangers who dealt with it remembered it as odd. Conservancy staff noted it as unusual. City officials filed reports that were technically public but not widely known or accessed. And Kennedy lived with the knowledge of what he'd done, apparently seeing no particular reason to reveal it publicly.

What changed in 2024 was The New Yorker's reporting. Presumably through their own reporting, interviews, or information from sources, they learned about Kennedy's involvement. This forced Kennedy's hand. Rather than let the magazine break the story with him as an antagonist, he decided to confess first and frame the narrative as best he could. It was a damage control strategy: get ahead of a damaging revelation by admitting to it on your own terms.

The Media Response: 2024 and Public Awareness

When Kennedy's video admitting to the bear incident went public in August 2024, the reaction was swift and critical. Major media outlets covered the story not just as a curious anecdote, but as evidence of poor judgment by someone who was then running for president and would later become a senior government official. The revelation raised questions about Kennedy's character, his regard for wildlife and public spaces, and his decision-making in general.

The timing was significant. Kennedy had already positioned himself as a critic of federal health agencies and advocate for environmental causes. His credibility on environmental matters was now called into question. Placing a dead bear in a public park to create a false scenario wasn't compatible with the image he'd cultivated as an environmental advocate. It suggested either that his environmental concerns were performative, or that his judgment was poor enough that a decade-old prank revealed a fundamental lack of seriousness.

Media coverage initially focused on the absurdity of the confession and the fact that Kennedy claimed the act was "fun." Later reporting, including that by journalists who requested public records, revealed the fuller scope of the incident—the forensic details, the investigation process, and the work of public servants who had to deal with the aftermath. This more comprehensive coverage painted a picture not just of Kennedy's poor judgment, but of the hidden costs of that judgment.

For the officials who had participated in the investigation a decade earlier, the public revelation must have been unsettling. Mc Guire's expression of sympathy for the "poor little guy" took on new meaning when it became clear that the death had been caused by human action and the body had been deliberately placed in the park. Handy's careful documentation of the scene was now understood to be part of the cleanup after a prank. The work they'd done professionally—treated seriously at the time—was revealed to have been motivated by deliberately false circumstances.

The media response also highlighted broader questions about Kennedy's trajectory. How someone with access to education, resources, and opportunities could make such poor decisions, and then treat those decisions as entertainment, raised character questions that persisted even after his eventual appointment as Health Secretary. The bear incident became a data point in a larger narrative about Kennedy's judgment and values.

Estimated data suggests that data collection and incident reporting are among the most severe challenges in urban wildlife management, highlighting the need for improved systems and infrastructure.

Legal and Environmental Implications: What Could Have Been Prosecuted

When Kennedy finally confessed to the bear incident, any possibility of criminal prosecution was already foreclosed by the statute of limitations. New York's environmental conservation law forbids illegal possession of a bear without a tag or permit, and it forbids illegal disposal of a bear. But these violations come with a one-year statute of limitations. Since Kennedy didn't confess until 2024, ten years after the incident, he was automatically shielded from prosecution.

This timing issue is significant. It's not that Kennedy's actions were legal—they almost certainly weren't. It's that the law provided a time window for prosecution, and that window had closed. If he'd confessed in 2015, prosecution would have been theoretically possible. By waiting until 2024, he ensured that any violations were beyond the reach of legal consequences. Whether this was a deliberate calculation or simply a convenient side effect of his delay is unclear.

From an environmental law perspective, Kennedy's actions violated several principles. Protected wildlife shouldn't be in private possession without authorization. Once an animal is dead, its remains shouldn't be disposed of illegally—there are proper procedures for handling wildlife carcasses that exist to protect public health and ensure accurate record-keeping. By placing the bear in Central Park, Kennedy interfered with the ability of wildlife managers to track mortality patterns, understand what was happening in the ecosystem, and respond appropriately to unusual deaths.

The forensic process that resulted from the discovery was actually effective. NYDEC was able to determine that the bear had been hit by a vehicle and identify the likely location of the collision. This kind of information is useful for understanding wildlife-vehicle interactions and identifying dangerous roads. But Kennedy's actions obscured the true source of the injury and complicated the investigation process. Instead of finding the cub where she'd actually been struck, investigators were working from a false location.

If Kennedy had confessed within the one-year window, he might have faced charges related to illegal possession and improper disposal of protected wildlife. These violations could have carried fines and potentially jail time, depending on the specific charges and how prosecutors decided to pursue the case. The fact that he didn't confess earlier meant the criminal justice system had no opportunity to evaluate his actions and impose legal consequences.

From a policy perspective, the statute of limitations raises questions about whether one year is adequate for investigating environmental crimes, particularly when those crimes involve deception about the location or circumstances of animal deaths. If someone can simply wait out the statute of limitations before confessing, they can effectively achieve immunity for violations that would otherwise be prosecutable.

Public Safety and Urban Wildlife Management

The bear incident highlighted a larger issue facing cities: how to manage wildlife that enters urban spaces. Black bears, coyotes, deer, and other animals increasingly find their way into metropolitan areas, creating situations that pose safety concerns for both the animals and people. Central Park, for all its urban setting, is still a significant green space connected to natural corridors that allow wildlife movement.

Most bear-in-urban-area incidents are handled through careful management designed to encourage the animal to leave and return to appropriate habitat. Tranquilizers might be used if the bear becomes aggressive or trapped. Aversion conditioning—making the urban area inhospitable to the animal—is sometimes employed. Direct lethal intervention is typically a last resort, reserved for situations where the animal poses an immediate threat and cannot be safely relocated.

The hypothetical question about the 2014 bear is what would have happened if she'd been discovered alive in Central Park. If park rangers encountered a living bear cub in the park, the response would have involved NYDEC wildlife managers who could have sedated and relocated her to appropriate bear habitat. The cub would have been reunited with her mother if possible, or placed in wildlife rehabilitation if necessary. Finding her dead meant this option was no longer available.

For park officials, the discovery created a procedure question: what's the proper way to handle a dead wild animal in an urban park? Immediate removal to prevent disease and pest attraction is standard. Documentation through photography and forensic examination ensures accurate record-keeping. Proper disposal through incineration, burial in appropriate facilities, or other approved methods prevents disease transmission and ensures respect for the animal's remains. These procedures exist for good reasons.

The bear incident also raised questions about security and oversight in Central Park. If Kennedy was able to place a dead bear in the park without immediate detection, it raised questions about park monitoring and security. How long did the bear remain undiscovered? How was Kennedy able to access the park with a dead animal without being stopped? These practical questions about park operations weren't extensively explored in the coverage, but they represent real management challenges.

Going forward, cities continue to struggle with urban wildlife management as habitat loss and climate change push animals into developed areas. The incident with Kennedy's bear didn't change policy or create new regulations—it was too specific and unusual to generate broad policy responses. But it illustrated one of the hidden problems of urban development: the collision between human activity and wildlife, and the costs of managing the aftermath.

The Role of Public Records in Accountability

The full story of the bear incident only became visible because of public records requests. Journalists who covered the story, particularly those working for WIRED, requested documents from the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation and other agencies. These requests, made possible by public records laws, yielded the emails, reports, photographs, and forensic analyses that provide the complete picture.

This is the power of public records in democratic accountability. Without these laws, the documents would remain in filing systems, inaccessible to citizens and journalists. Officials could handle incidents, conduct investigations, and file away the records without public scrutiny. The incident with Kennedy's bear would have remained a historical curiosity known only to people who were directly involved.

Public records requests serve multiple functions. They allow journalists to verify official statements and uncover information that might otherwise remain hidden. They enable citizens to understand how tax dollars are spent and what government agencies are doing. They create accountability by ensuring that government actions are documented and potentially subject to public review. And they preserve institutional memory, keeping records that might otherwise be lost or destroyed.

The records obtained in the bear case reveal not just the incident itself, but the professional and methodical way that public servants responded to it. The emails show real people doing their jobs with attention to detail and appropriate concern. The reports show that officials took the investigation seriously, even without knowing its eventual resolution. The photographs document the scene carefully, preserving evidence for analysis. These records represent the normal function of competent government—people working through a problem, documenting their work, and maintaining standards of professional conduct.

For a public that's often skeptical of government agencies, these records can actually demonstrate competence and professionalism. The work done by NYDEC, UPR, NYPD, and other agencies in investigating the bear's death was solid. They conducted forensic analysis, followed procedures, coordinated across agencies, and maintained documentation. That the case remained unsolved wasn't a failure of investigation but rather a consequence of not knowing the perpetrator's identity.

What This Reveals About Kennedy's Judgment

Beyond the bear incident itself, Kennedy's handling of it—and his eventual admission—reveals significant things about his judgment and decision-making. The core question is: what kind of person dumps a dead animal in a public park as a prank and then keeps that fact secret for a decade? The answer suggests several concerning patterns.

First is the fundamental disregard for consequences. Kennedy didn't seem to consider the work his action would create for public employees. He didn't think about the park visitors who might encounter the dead animal or the concerns it would raise. He didn't consider the wildlife management implications of a bear in Central Park. The entire focus was on whether the prank would be believed—the entertainment value of fooling people—rather than the actual impact of his actions.

Second is the gap between Kennedy's public persona and his private behavior. He's positioned himself as an environmental advocate and public health expert. Yet he was comfortable treating a wildlife death as entertainment material. This suggests either that his environmental advocacy is performative, or that he compartmentalizes his beliefs and actions in ways that allow him to hold contradictory positions.

Third is his approach to accountability once exposed. Rather than expressing genuine remorse or explaining how the bear came into his possession, Kennedy framed the incident as lighthearted and amusing. He didn't acknowledge the work it created for public servants, the wildlife welfare concerns, or the disruption to a public space. This lack of genuine accountability is consistent with someone who views consequences as externalities that happen to other people.

Fourth is the calculated timing of his confession. Kennedy didn't voluntarily come forward when he could have been prosecuted. He waited until The New Yorker was about to publish the story, then confessed on his own terms to control the narrative. This is a sophisticated form of damage control—admit before being exposed, and frame it your way. It's a strategy that works to manage public perception but doesn't suggest genuine remorse.

Fifth is the reflection of these judgment patterns in Kennedy's public positions and statements. Throughout 2024, when questions arose about various Kennedy statements and claims, a pattern emerged of him making confident assertions without adequate evidence, dismissing critics, and treating serious subjects with a casual approach that seemed inconsistent with their actual importance. The bear incident fits into a larger pattern of behavior.

The Park, the Public, and the Question of Responsibility

Central Park exists as a public space by deliberate choice. New York City maintains it for residents and visitors, investing resources in its management, security, and upkeep. When Kennedy placed a dead animal in the park, he violated the implicit social contract that public spaces represent. These spaces depend on people using them responsibly, respecting both the physical infrastructure and the experience of others.

For the hundreds of thousands of people who visit Central Park daily, the space represents something important. It's where they exercise, rest, spend time with family and friends, and find respite from the urban environment. The discovery of a dead bear violated that experience. People who learned about the bear at the time were confronted with the reminder that even in the carefully managed, heavily visited park, unexpected and unsettling things could happen.

Kennedy's action was a form of imposition on a public space and the people who use it. He decided to conduct his prank in a park that doesn't belong to him, using the public space as the venue for his entertainment. The consequences—investigations, documentation, coordination between agencies, and the mystery that persisted for a decade—flowed from that choice to impose his actions on the public domain.

This raises broader questions about the responsibilities of people with resources and access. Kennedy had the ability to acquire a dead bear cub, transport it to Manhattan, and place it in a public park without immediate consequences. Most people don't have those resources or opportunities. His ability to act on the impulse to conduct the prank, and then his ability to deflect consequences for a decade, reflects structural advantages that most people don't possess.

Public spaces depend on people treating them with respect. When individuals with resources and power treat public spaces as playgrounds for their personal amusement, it degrades those spaces for everyone. It also consumes public resources that could be directed toward other purposes. The work that city officials did investigating Kennedy's bear was work that didn't go toward other park management, wildlife monitoring, or public service.

Ultimately, the bear incident is a story about responsibility—Kennedy's failure to take it, and the professional people who fulfilled their responsibilities despite his actions. The contrast is stark and instructive.

Future Implications and Broader Wildlife Concerns

While the specific incident with Kennedy and the bear is unlikely to spawn new policies directly—it's too unusual and personal to the situation—it does highlight ongoing concerns in wildlife management, particularly at the urban-wildland interface. As human development continues to expand into traditional wildlife habitat, and as climate change pushes species' ranges in new directions, the conflicts between wildlife and urban areas will likely increase.

Cities need better systems for reporting, tracking, and managing wildlife incidents. When animals appear in urban spaces, comprehensive documentation allows scientists and managers to understand population movements, identify barriers to wildlife movement, and assess human-wildlife conflict patterns. Kennedy's action disrupted this data collection by placing an animal in a false location and obscuring the true circumstances of her death.

Wildlife rehabilitation and rescue capabilities in urban areas remain limited. If the bear cub had been found alive, the immediate response would have involved limited options. Most urban areas don't have the infrastructure to handle wild bears. They can be tranquilized and transported back to appropriate habitat if they're found relatively quickly, but that requires specialized equipment and trained personnel that not all cities maintain.

Public education about wildlife safety and coexistence remains important. If people encounter wild animals in urban spaces, they should report them to appropriate authorities rather than attempting to handle them or move them. Kennedy's undisclosed possession of the cub is an example of precisely the wrong response to encountering wildlife in a place where it doesn't belong.

The case also underscores the importance of protecting wildlife from interference. Bears, like all wild animals, deserve to live their lives without human manipulation. The bear cub's life was tragically short, and her death was violent. Kennedy's actions—acquiring her remains, transporting them, and placing them in a public park—represented additional interference with a wild animal, even after death.

Going forward, as society continues to grapple with wildlife management in increasingly crowded cities, the lessons from the bear incident remain relevant. Professional management, proper documentation, respect for public spaces, and taking responsibility for consequences all matter. Kennedy's prank failed on every one of these fronts.

Conclusion: What the Bear Incident Really Tells Us

The dead bear cub in Central Park might seem like a strange anomaly—a one-off incident caused by one person's poor judgment. But examined closely, through the documents that public records requests have revealed, it becomes a window into several important issues: how public servants handle unusual situations, how environmental crimes can evade prosecution, how wildlife and urban development interact, and what responsibility means when you have resources and access.

For the officials who worked the case—Bonnie Mc Guire, Eric Handy, Kevin Hynes, Caroline Greenleaf, and the many others who touched the investigation—the incident was treated seriously. They did their jobs professionally, maintained documentation, and followed procedures. They expressed appropriate concern for the animal and curiosity about what had happened. The fact that their work ultimately led nowhere—in terms of identifying Kennedy as the perpetrator—reflects the inherent difficulty in investigating crimes where the perpetrator remains unknown.

For Kennedy, the incident reveals a pattern of behavior that appears in his other controversies: poor judgment, disregard for consequences, and an ability to eventually manage the fallout through selective disclosure and narrative control. He placed a dead bear in a public park for entertainment, treated it as a cute anecdote, and waited a decade before admitting it only when forced by pending media exposure.

For the broader public, the incident is a reminder that accountability matters. Without public records laws that enable journalists and citizens to request documents, the full scope of the bear incident would likely remain unknown. These laws create the possibility—not the certainty, but the possibility—of transparency and accountability. Kennedy got away with violating environmental law because he waited out the statute of limitations, but his actions were at least made visible by public records requests.

The bear cub herself remains the most sympathetic figure in the story. A young animal, healthy and feeding naturally at seven to eight months old, struck by a vehicle on a New York highway. Her injuries were catastrophic and immediate. But her story didn't end there—she was moved, placed in a park as part of a prank, found by park rangers, examined by forensic scientists, and became the subject of a mystery that lasted a decade before being solved. None of that served her or honored her life.

Moving forward, the bear incident serves as a specific example of larger principles. Respect for public spaces matters. Taking responsibility for consequences matters. Environmental laws exist for reasons and shouldn't be violated casually. Public records transparency creates accountability that doesn't otherwise exist. And wildlife, even in death, deserves to be treated with respect rather than as material for pranks. These lessons extend far beyond Kennedy and the bear, applying to how we all interact with public spaces and the natural world around us.

FAQ

What actually happened with the bear that RFK Jr. found in Central Park?

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. admitted in August 2024 that he had placed a dead bear cub in Central Park in October 2014. The cub was originally struck by a vehicle along the New York State Thruway (likely near the NY/NJ border in Rockland or Orange County), and Kennedy transported her body to Manhattan, placing her under a bush near West 69th Street as part of a prank meant to look like a bicycle accident.

Why did Kennedy wait 10 years to reveal he had dumped the bear?

Kennedy kept the incident secret for a decade, only admitting to it in August 2024 when The New Yorker was preparing to publish a story about his involvement. Rather than allow the magazine to break the story with him as a subject, he confessed on his own terms, posting a video on social media to control the narrative. By waiting until 2024, he also ensured that any potential prosecution was barred by the one-year statute of limitations for the violations involved.

What did the forensic examination reveal about how the bear died?

The necropsy conducted by NYDEC wildlife biologist Kevin Hynes determined that the bear cub (a female, 7-8 months old) died from massive blunt force trauma consistent with a high-speed vehicle strike. She had spinal fractures, all four legs broken, and a shattered skull severe enough that the majority of her brain tissue was lost through her mouth. The injuries were catastrophic and would have caused immediate or near-immediate death.

What agencies were involved in investigating the bear discovery?

Multiple agencies coordinated on the investigation, including the New York City Parks Department, Urban Park Rangers (UPR), the NYPD, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (NYDEC), and the Central Park Conservancy. The NYDEC took the lead on the forensic investigation, removing the bear to a state laboratory near Albany for detailed necropsy examination.

Could Kennedy have been prosecuted for dumping the bear?

Yes, Kennedy could have potentially been prosecuted if he had confessed within one year of the incident (i.e., by October 2015). New York environmental conservation law forbids both illegal possession of a bear without proper permits and illegal disposal of bear remains, with a one-year statute of limitations. However, since Kennedy didn't confess until August 2024, any potential prosecution was barred by the expired statute of limitations.

Why did it take a decade for the incident to become public?

Without knowing that Kennedy had deliberately placed the bear in Central Park, NYDEC's investigation was unable to identify the perpetrator or understand the full circumstances of the incident. The investigation concluded in late 2014 "due to a lack of sufficient evidence" to determine if state law had been violated. The case remained a public mystery until The New Yorker began investigating Kennedy's background and reported the story that forced Kennedy to confess.

What does this reveal about public records and government transparency?

The complete story of the bear incident only became visible because journalists made public records requests to the NYC Parks Department and other agencies. These requests yielded emails, reports, photographs, and forensic analyses that had previously been filed away in government archives. Public records laws enable citizens and journalists to understand what government agencies do and how they respond to unusual situations, creating accountability that wouldn't otherwise exist.

What were the broader implications for urban wildlife management?

The incident highlighted challenges in managing wildlife encounters in urban areas. Black bears are native to New York State but uncommon in Manhattan, so officials had to treat the discovery as an emergency. It demonstrated the importance of proper procedures for handling wildlife remains, the role of forensic science in understanding animal deaths, and the coordination required between multiple agencies when unusual wildlife situations occur in public spaces.

Key Takeaways

- Kennedy's prank: RFK Jr. admitted in August 2024 to dumping a dead bear cub in Central Park in 2014 to make it look like a bicycle accident, treating the incident as entertainment

- Forensic findings: The bear (a healthy 7-8 month old female) died from catastrophic blunt force trauma from a vehicle strike, with massive injuries documented by NYDEC forensic examination

- Official response: NYC Parks, Urban Rangers, NYPD, and NYDEC conducted professional investigation and forensic analysis, remaining unaware the death was unrelated to Central Park itself

- Statute of limitations: Kennedy avoided prosecution by waiting until August 2024 to confess, well beyond the one-year statutory window for environmental crimes

- Public records revelation: Journalists uncovered the full scope through public records requests, revealing the professional work and resources consumed by Kennedy's actions

- Accountability through transparency: The incident demonstrates how public records laws enable accountability that wouldn't otherwise exist for powerful individuals

- Wildlife welfare implications: The case illustrates how human actions impact wild animals and the importance of respecting both public spaces and wildlife

![RFK Jr.'s Dead Bear Incident: What Public Records Actually Reveal [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/rfk-jr-s-dead-bear-incident-what-public-records-actually-rev/image-1-1767803868414.jpg)