The Surveillance Paradox Nobody Expected

We've been told surveillance is a one-way street. The government watches you. You don't watch back. That's supposed to be the deal in a surveillance state.

But something unexpected happened. When federal agents started conducting mass immigration raids in early 2025, something shifted. Ordinary people grabbed their phones. They filmed. They posted. They organized.

Now, the very government officials who've spent decades building surveillance infrastructure are suddenly complaining that they're being watched. They're claiming it's dangerous. They're calling it "doxing." They're even asking Congress to make it illegal.

What's actually happening is far more interesting than the panic suggests. We're witnessing a fundamental restructuring of surveillance power in America, where ordinary citizens have suddenly become documenters of state activity at scale. This isn't some fringe movement. It's mainstream. It's fast. And it's forcing a reckoning about who actually gets privacy in a surveillance state.

The surprising part isn't that citizens are recording police. That's been happening for decades. The surprising part is how this year turned it into a mass movement, how technology enabled it, and what it means for the balance of power between government and citizens.

Let's be clear about what's actually at stake here. This isn't about phones or apps or social media. It's about who gets to remain anonymous in public, who gets held accountable, and what happens when surveillance technology democratizes.

TL; DR

- Citizen recording of police reached unprecedented scale in 2025, driven by high-profile federal enforcement actions and easy smartphone technology

- The legal right to record public police activity is well-established, but the government is testing new legal theories to criminalize it

- Technology has fundamentally changed the surveillance equation, giving ordinary citizens tools once reserved for state actors

- The concept of "doxing" is being misapplied to criminalize basic public accountability, according to civil liberties experts

- This represents a genuine shift in power dynamics, where civilians now have the ability to counter the traditional information asymmetry between police and public

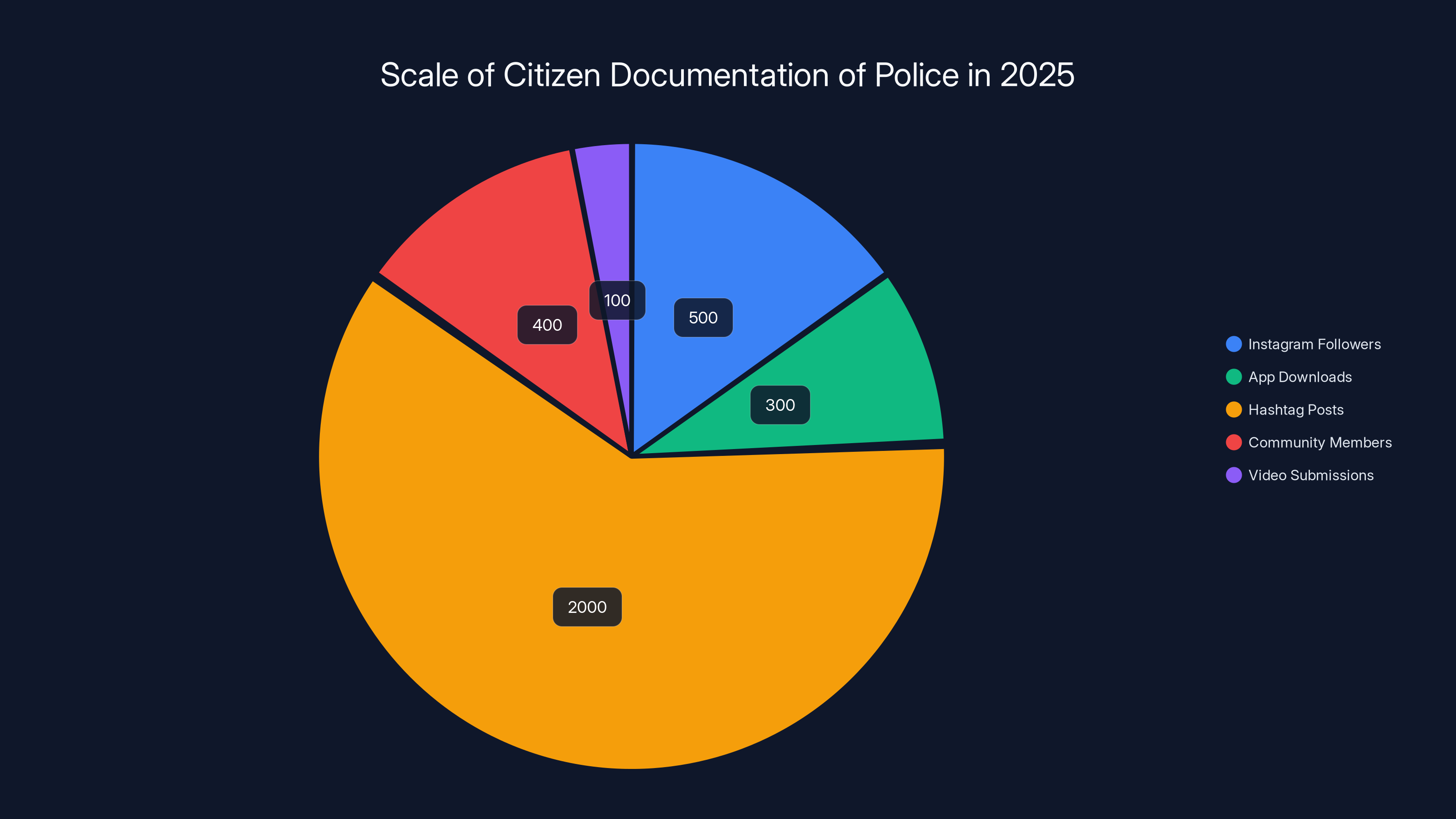

The scale of citizen documentation in 2025 is significant, with millions participating through social media, apps, and online communities. Estimated data highlights the broad engagement across various platforms.

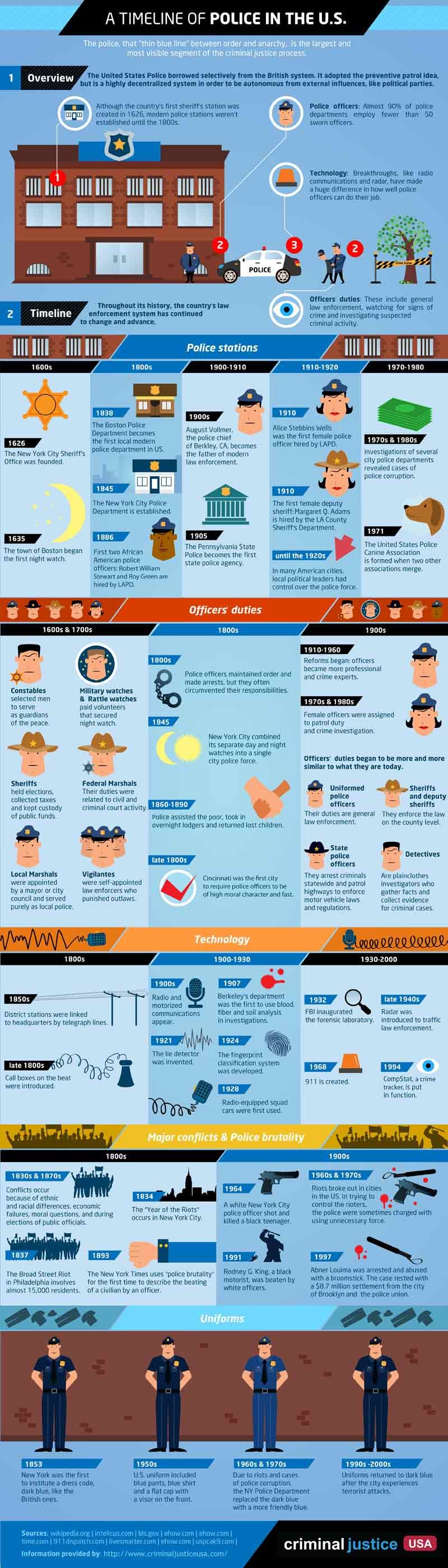

A Brief History of Citizen Accountability Movements

People recording the police isn't new. Far from it.

One of the first major moments came in March 1991 when a Los Angeles resident named George Holliday pointed his camcorder at LAPD officers beating a Black man named Rodney King. That footage changed everything. It was shocking precisely because it contradicted the official narrative. Cops had claimed King resisted. The video showed otherwise. Holliday's documentation sparked not just local outrage but a national conversation about police violence and racial injustice that resonates today.

The historical pattern goes back even further. Journalists have been documenting police activity since at least the 1968 Democratic Convention, when news cameras captured Chicago police attacking protesters and journalists and later lying about who started the violence. Civil rights activists in the 1960s made it part of their systematic resistance to police brutality. The difference then was that cameras were expensive and hard to use. They required professional equipment and training.

Fast forward to 2020. A 17-year-old named Darnella Frazier recorded Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on the neck of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, for over nine minutes. Floyd died. The video went viral across TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube within hours. That summer, millions of people protested. The Black Lives Matter movement that exploded that year was powered almost entirely by video documentation shared on social media. Thousands of videos showing police violence flooded every platform. The sheer volume of documentation made it impossible for institutions to deny what was happening.

What people don't always recognize is that 2020 was a transitional moment. Filming police became mainstream. Teenagers did it casually. Passersby did it instinctively. It stopped being the domain of activists and started being what ordinary people did when they saw something wrong.

Then 2025 happened.

The 2025 Escalation: When Recording Became Mass Practice

In January 2025, the Trump administration launched its most aggressive federal immigration enforcement operation in decades. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) began conducting raids across the country. Federal agents, often masked and unidentified, swept into workplaces, homes, and public spaces to apprehend undocumented immigrants.

What made 2025 different wasn't the enforcement itself. The government has been conducting immigration raids for years. What was different was the scale, the visibility, and the population paying attention.

Suddenly, videos of armed agents in tactical gear breaking into restaurants, gas stations, and apartment buildings were everywhere. People in Los Angeles, Chicago, Raleigh, and dozens of other cities watched federal officers grab their neighbors, their coworkers, their friends. And they recorded it.

These weren't organized activists or trained documentarians. These were regular people. A grandmother watching from her apartment window. A restaurant manager who happened to be filming when agents came through. A bus driver who had a phone in his pocket.

Within weeks, "ICE watch" groups emerged in virtually every major city. Some organized through Facebook. Others through WhatsApp. They coordinated people to show up at federal buildings and detention facilities. They documented arrests in real time. They created apps that tracked federal enforcement activity by neighborhood and sent push notifications when raids were reported nearby.

Apple and Google both temporarily removed some of these apps from their stores, citing concerns about harassment. But the damage was already done. People had discovered they could monitor government activity systematically. The information asymmetry that once defined the relationship between police and public had shifted.

One of the most significant developments was the emergence of Instagram accounts dedicated to documenting ICE agents. These accounts had tens of thousands of followers. They posted photos, videos, home addresses, license plate numbers, and names of federal agents. Some accounts livestreamed ICE activities from the moment they spotted agents moving through neighborhoods.

This is where the rhetoric of "doxing" entered the conversation.

Estimated data shows that the UK has the highest prevalence of citizen recording, with Hong Kong and Brazil following closely. The USA, while prevalent, faces more governmental resistance.

The "Doxing" Accusation: A Misapplication of a Term

Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem began publicly accusing citizens of "doxing" federal agents. The claim was straightforward: people identifying masked federal agents and sharing that information online constituted doxxing, which she characterized as violence.

Here's the problem with that framing. Doxing, in its original context, means researching and revealing private information about someone for the purpose of harassment. It typically involves uncovering residential addresses, phone numbers, family members' names, or other intimate details not publicly available. The intent behind doxxing is usually to enable harassment, threats, or violence.

What citizens were actually doing in 2025 was something fundamentally different. They were photographing people in public spaces performing government functions. These weren't hidden addresses. Some of these agents had shared their own names on Instagram. Others had been identified through government databases or public records. The information being shared wasn't secret. It wasn't private. It was, in the strictest sense, already public.

More importantly, the people doing the recording weren't trying to harass these agents. They were trying to establish accountability. When you photograph a police officer conducting an arrest in public, you're not invading their privacy. You're documenting government conduct.

The legal consensus on this point is clear. Adam Schwartz, privacy litigation director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, put it plainly: the public has a constitutional right to record police in public spaces, provided they're not interfering with official operations. This isn't a recent development. Courts have been recognizing this right since at least the early 2000s. The First Amendment protects the right to document government activity.

Jennifer Granick, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union's Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, emphasized the philosophical principle at stake. The government owes transparency to the public. Citizens owe privacy to themselves and each other. That's the baseline of a free society. When government actors are in public performing government functions, they have a reduced expectation of privacy.

Schwartz articulated this principle clearly: "What the government owes to people is that people get to be private. What the government owes the public is transparency. The public gets to know what the government is doing."

But the accusation wasn't just rhetorical. It was the beginning of a legal strategy.

The Government's Response: Legal Overreach

In September 2025, federal prosecutors indicted three people for allegedly following an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent home while livestreaming his address on Instagram. The charges were serious. The case sent a message: document our agents, face federal charges.

The same month, the Department of Homeland Security subpoenaed Instagram owner Meta, demanding the company unmask six Instagram accounts that had allegedly posted about immigration enforcement activity. DHS claimed this was part of a criminal investigation into threats against federal agents. The subpoena specifically requested identifying information about account holders who had posted tracking information about ICE activities.

Meta initially complied with the subpoena. Then, in early December, after pushback from civil liberties groups and public pressure, DHS withdrew it. But the attempt itself was revealing. The government wasn't just complaining about the recordings. It was actively investigating the people doing the recording and trying to identify them.

Taking things further still, the FBI began launching investigations into what it called "criminal and domestic terrorism" related to threats against immigration enforcement agents. A bureau document obtained by journalists revealed that the FBI had opened investigations in at least 23 areas around the country. The scope was massive. This wasn't about prosecuting specific threats. This was about creating an atmosphere of fear around documentation itself.

In June, Republican Senator Marsha Blackburn introduced the "Protecting Law Enforcement From Doxing Act." The bill would create new legal penalties for revealing identifying information about law enforcement officers. The intent was clear: criminalize the documentation that had become ubiquitous.

The bill hasn't gained traction in Congress. But its existence matters. It represents an explicit attempt to make recording police and sharing that information a federal crime. If it passed, people could face federal charges simply for posting a photo of a federal agent in a public space.

Outside of formal legal channels, supporters of the administration engaged in what civil liberties experts call "jawboning." They pressured social media platforms to remove videos. They demanded that companies identify people who posted documentation. They created counter-narratives designed to delegitimize the entire practice.

Why This Matters: The Inversion of Surveillance Power

What's genuinely significant about 2025 is that it reveals a fundamental truth about surveillance technology that often gets obscured in policy discussions.

When surveillance technology exists, it doesn't stay concentrated in the hands of the powerful. Eventually, other people get access to it too. Once the government had cameras. Then businesses had cameras. Then phones had cameras. Then everyone had cameras.

This creates an interesting paradox. Surveillance technology was originally promoted as a tool for making people safer and keeping government honest. Put cameras in public spaces, the argument went, and crime would decrease. Install bodycams on police, and misconduct would become visible.

But the technology didn't stay in the hands of authorities. Regular people got the same tools. Better tools, actually. Everyone carries a smartphone with a camera more powerful than surveillance equipment available to police departments ten years ago.

What 2025 demonstrates is that once surveillance technology democratizes, you can't put it back in the box. The government can't maintain a monopoly on recording and documentation anymore. The asymmetry of information starts to break down.

For decades, the dynamic worked like this: police conducted arrests, and their version of events became the official record. Civilians saw something different, but nobody believed them. It was a one-way information flow. Police documented their own conduct, and citizens had no evidence to contradict that documentation.

Then, starting with the Rodney King video and accelerating through 2020, that dynamic inverted. Suddenly, there were multiple versions of events. Citizen videos contradicted police narratives. The information asymmetry collapsed. You can't claim that an arrest was necessary when there's video showing it wasn't. You can't claim someone was resisting when the recording shows they were complying.

In 2025, we moved into a new phase. It's not just that citizens can document police conduct anymore. It's that they can do it systematically, at scale, and coordinate that documentation across entire cities.

From the government's perspective, this is profoundly threatening. Not because the government is doing something wrong, necessarily, but because it loses control of the narrative. When there's a livestream of every arrest, when social media is flooded with documentation, the government can't control the story anymore.

That's what the rhetoric about doxing and violence is really about. It's not actually about privacy. It's about power. The government had power because it had information control. Now it doesn't.

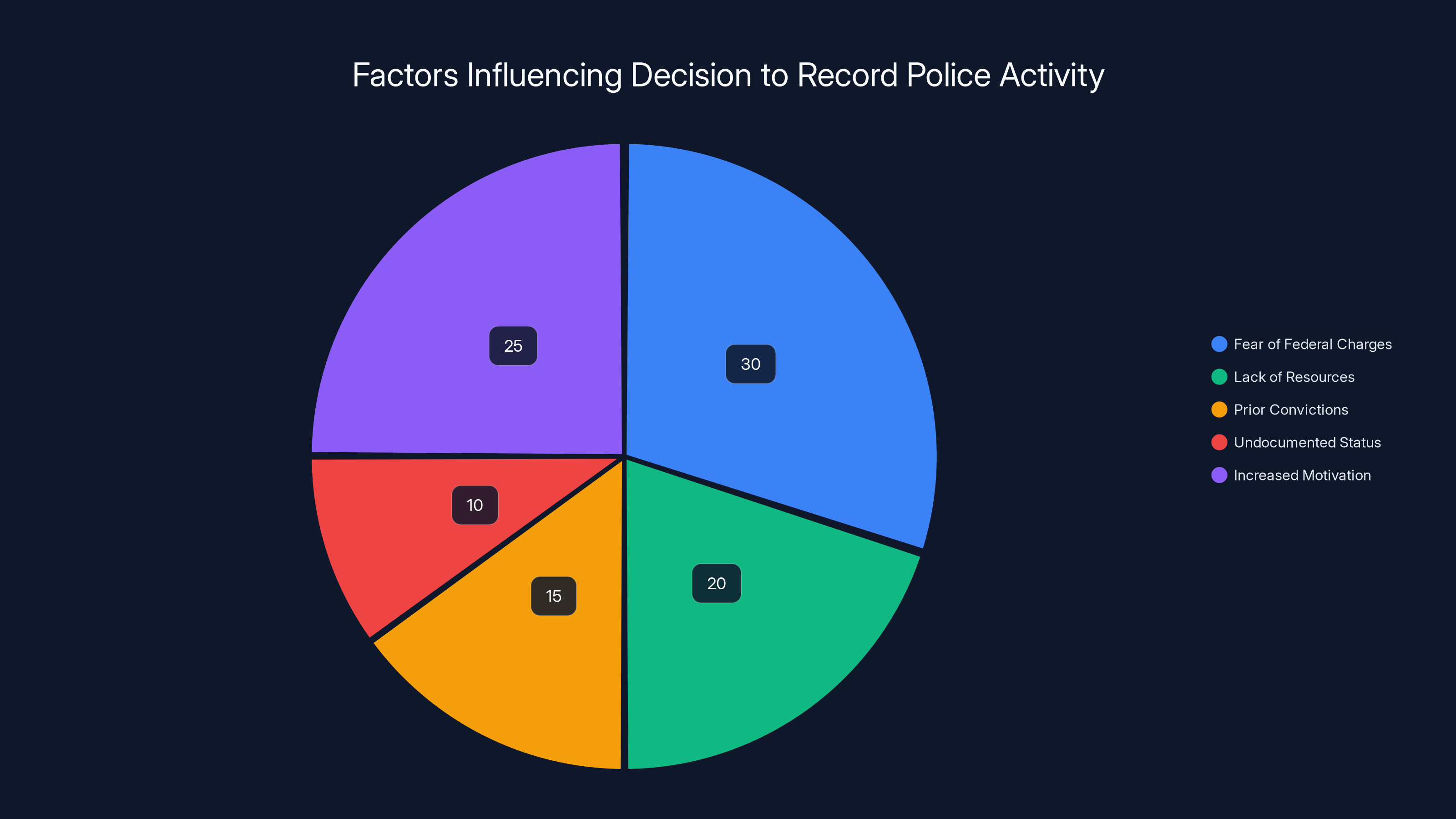

Fear of federal charges and lack of resources significantly deter recording, but increased motivation due to perceived government concealment also plays a major role. Estimated data.

The Technology: How Apps Changed the Game

The tools enabling this shift in surveillance power are worth examining. They're not that sophisticated. Many of them are just basic smartphone features combined with social media platforms.

One of the most significant tools that emerged in 2025 was a simple app that let users report immigration enforcement activity in real time. When someone saw ICE agents, they'd open the app and mark the location. The app would aggregate these reports and show other users where enforcement activity was happening in their city.

It's basically Waze for immigration raids. You see something, you report it, and everyone else in your city gets a notification. Simple. Powerful. The app got hundreds of thousands of downloads before Apple and Google removed it from their stores.

But removing the app from official app stores doesn't eliminate the functionality. Users can still download it directly. The damage is already done. People know they can build these tools. Other developers will build similar ones.

Then there are the Instagram accounts. They're doing something equally straightforward. Someone sees an ICE agent. They photograph them. They post the photo on Instagram with details about location and time. Other people follow the account and get notifications when new photos are posted.

It's not sophisticated. It's not secret. It's just normal social media use, except directed at documenting government activity instead of cats or food or vacation photos.

But the scale matters. When one person documents an arrest, it's anecdotal. When hundreds of people document arrests across a city on the same day, it becomes pattern evidence. When there are livestreams of multiple raids happening simultaneously, people can see the scope and scale of enforcement activity in real time.

The government's strategy in response has been to try to restrict the technology itself. Pressure app stores to remove apps. Subpoena social media platforms to identify users. Launch criminal investigations against people doing the recording.

But here's what they're discovering: you can't undemocratize technology. Once everyone has a camera and a social media account, the ability to document is distributed. You can't concentrate it back in the hands of authorities.

In a way, this is what surveillance theorists have been predicting for years. The technology eventually becomes too cheap and too distributed to control. What's happening now is the realization of that prediction.

The Constitutional Question: Do Police Have Privacy?

The legal question at the center of this conflict is deceptively simple. Do law enforcement officers have a right to privacy when they're in public performing government functions?

The constitutional answer is pretty clear, and it's been clear for a long time. No. They don't. Not really.

The First Amendment protects the right to document and observe government conduct. The Supreme Court hasn't directly ruled on recording police, but lower courts have been consistent. People have a right to film police in public. This right extends to posting that footage online. It extends to identifying people in that footage if they're acting in an official capacity.

What complicates this is that police have argued that some forms of documentation do interfere with their ability to conduct business. If someone is blocking a police officer or obstructing an arrest to film it, that's one thing. If someone is standing at a distance, filming on their phone, and not interfering with anything, that's completely protected.

The courts have generally been clear about this distinction. You can't interfere with police operations. But you can observe and document them.

Where this gets legally murky is in the question of identifying individual officers. Does an officer have a right to anonymity in public? The courts haven't definitively answered this, because it rarely comes up. Most people didn't have the technology to systematically photograph and identify officers until very recently.

But the privacy interest is weak. These are government employees performing government functions. They have official titles. Many of them have public social media profiles. If someone identifies them through public records or government databases, is that doxxing? It doesn't seem like it should be.

The government's strategy appears to be to test new legal theories. Maybe they can claim that coordinated recording constitutes harassment. Maybe they can argue that livestreaming creates a public safety risk. Maybe they can use existing stalking or harassment laws to criminalize the practice.

But these are stretches. The constitutional baseline is clear: people have a right to observe and document government conduct. That right is especially strong when it comes to police and enforcement officials.

This doesn't mean there aren't legitimate questions about how this power can be abused. If people start coordinating to harass individual officers or their families, that could cross into actual doxing. If someone uses the information to threaten violence, that's a crime regardless of how the information was obtained. The line exists. It's just a lot further out than the government claims it is.

The Chilling Effect: What Happens When People Are Afraid to Record

One of the subtle but significant impacts of the government's response is the chilling effect it creates. When people hear that they might face federal charges for documenting police activity, some of them become less likely to do it.

This is especially true for vulnerable populations. Undocumented immigrants are less likely to film ICE agents if they think that filming will make them more visible to law enforcement. People with prior convictions are less likely to get involved if they think it could be used against them. People without resources to hire lawyers are less likely to take the risk.

The government probably understands this. The threat of prosecution doesn't need to actually result in convictions to work. If even a fraction of people become too scared to film, the government's conduct becomes less visible. The information asymmetry starts to reassert itself.

This is why the indictments in September were so significant. They didn't need to result in convictions. They just needed to send a message: participate in this, and you face federal charges.

In some ways, this is a classic surveillance tactic. You don't need to actually prosecute everyone. You just need people to believe you might prosecute them. Fear changes behavior more effectively than laws often do.

The press releases, the subpoenas, the FBI investigations, the proposed legislation, all of it serves to create an atmosphere where people second-guess whether they should pull out their phones.

But something interesting happened. The threat didn't stop people from recording. It made them angrier. It radicalized more people to participate. It turned something that was already mainstream into something even more widespread.

When people see the government trying to criminalize documentation of its own conduct, they interpret it as the government having something to hide. And that interpretation drives more people to try to see what it is.

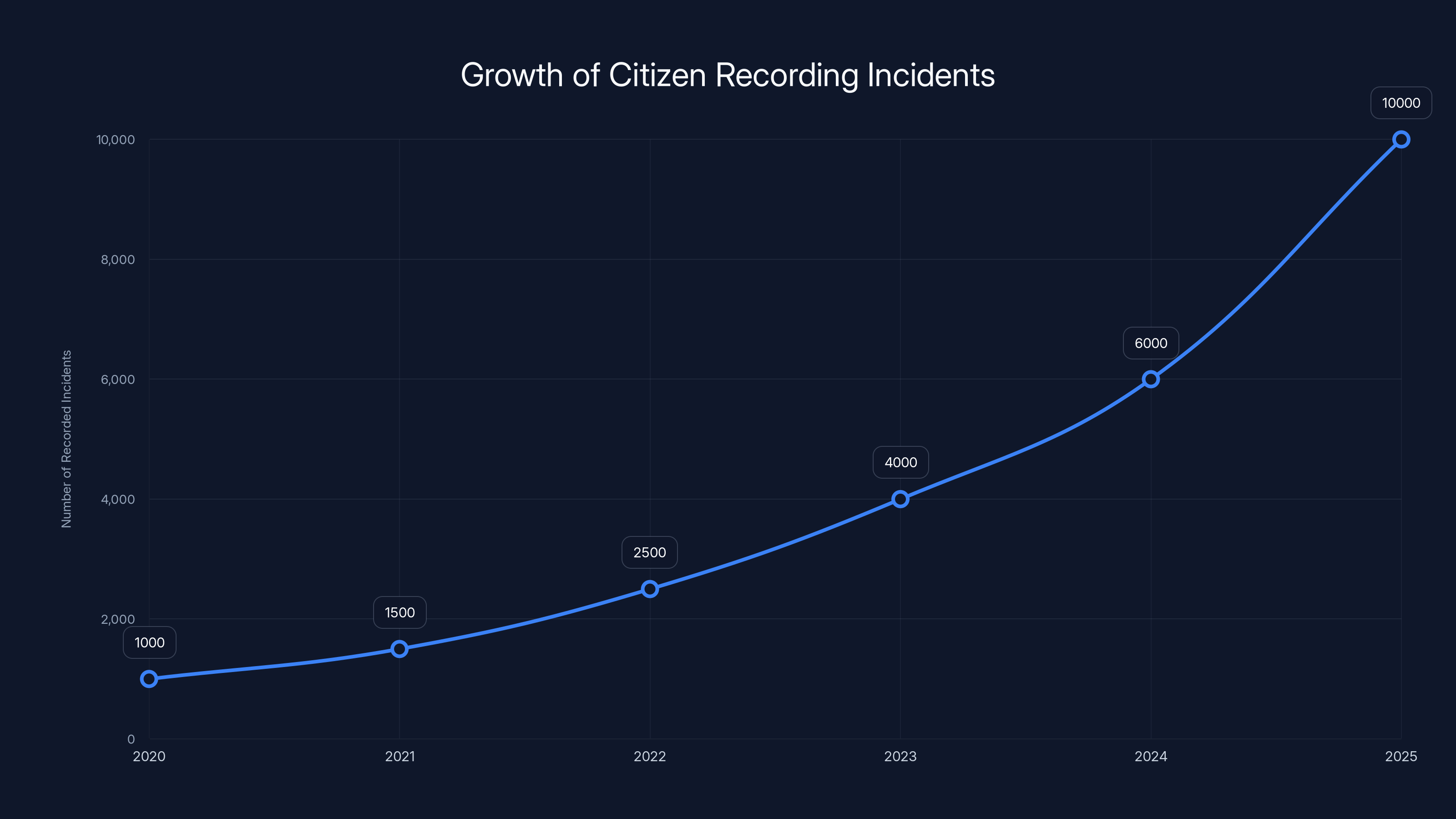

The number of recorded incidents by citizens has significantly increased from 2020 to 2025, driven by advancements in smartphone technology and social media platforms. (Estimated data)

Who's Doing the Recording: The Demographics of Citizen Documentation

It's worth thinking about who actually is recording police and ICE in 2025. The easy assumption is that it's activists and radical leftists opposed to the Trump administration. But that's not quite accurate.

According to interviews and data collected by researchers studying the phenomenon, the people doing the recording are incredibly diverse. Yes, there are activists involved. But there are also:

Regular citizens who happened to be nearby when something happened. A person eating at a restaurant when ICE agents came through. Someone waiting at a bus stop. A parent picking up kids from school.

Community members who specifically organized to defend their neighborhoods. Church groups, civic organizations, neighborhood associations that decided to document enforcement activity to protect their communities.

Journalists doing their job. Independent journalists, not just professional reporters, but people with social media followings documenting what they see.

Family members of people being arrested. Someone watching their relative get detained wants to document it for legal purposes. They want a record of what happened.

Immigration advocates who are explicitly trying to document enforcement patterns and scale.

This diversity matters because it means there's no single narrative about who's driving this trend. It's not a coordinated campaign by a particular group. It's something people across the political spectrum are participating in, for various reasons.

Some people are doing it because they oppose the policies. Others are doing it because they believe in government transparency. Some are doing it because they're afraid for their neighbors and want to help. Some are doing it because they've learned that documentation can help in legal defense.

The one thing they have in common is that they all have smartphones, and they've all decided that their communities benefit from documentation of government conduct.

The International Context: Surveillance Power Shifting Globally

What's happening in the United States in 2025 isn't isolated. This dynamic is playing out in different ways in different countries, but the pattern is consistent: as surveillance technology becomes ubiquitous, the power balance shifts.

In Hong Kong, since 2019, citizens organized to document police conduct during protests. They created encrypted platforms to share footage and identify officers. They understood that documentation could be a form of resistance against police violence.

In Brazil, bystanders recording police violence has become common enough that it's a major factor in any controversial police shooting. The government doesn't like it, but it's normalized.

In the UK, people record police as a routine matter. It's been happening for years. The police have largely accepted that recording is something the public is going to do.

What's distinctive about the United States in 2025 is the scale and the coordination of the response. Other governments have had to accept that recording is inevitable and adjust their policies. The Trump administration is trying to fight it directly, rather than accept it as a new normal.

This is actually where the comparison to other countries becomes instructive. In places where the government has tried to suppress recording through legal threats and prosecution, it's generally backfired. It's radicalized people. It's driven them to use encrypted platforms and harder-to-identify accounts. It's made the issue more visible, not less.

The path that other governments have found more successful is to accept that people are going to document police conduct, and to focus on building police departments that can hold up to scrutiny. If your officers are doing their jobs properly, recording them shouldn't be a problem. The problem emerges when recording reveals misconduct.

Privacy, Publicity, and the Social Contract

Here's where this gets philosophically interesting. The government's argument that revealing the identities of federal agents violates their privacy rests on an assumption that's increasingly questionable: that government employees have a reasonable expectation of privacy in public.

For much of modern history, that expectation made sense. If you were a police officer, most people wouldn't know who you were unless they saw you working. Your identity was private. Your work was visible, but you were not.

But that was always based on scarcity of information and technology. In a world where you need professional equipment to photograph and identify people, most people escape public identification. In a world where everyone has that equipment, nobody does.

This creates a new social contract question. What privacy do we owe to people who hold power over us? What transparency do we owe to ourselves about the conduct of government?

The classical civil liberties framework says: government employees, when acting in their official capacity, don't have the same privacy expectations as private citizens. They've taken a job that involves exercising power over others. Transparency is part of the trade-off for that power.

But government employees are also people, with families, and they have some interest in not being harassed. So how do we balance those interests?

The answer that seems to be emerging organically from practice is: you can identify the officer, you can document the conduct, but you have an obligation not to use that information to harass their family or threaten violence. You have an obligation not to lie about the person to incite others against them. But you don't have an obligation to pretend you didn't see what you saw.

It's a reasonable balance. It protects transparency while limiting abuse. It respects both the public's interest in accountability and the individual officer's interest in not being harassed.

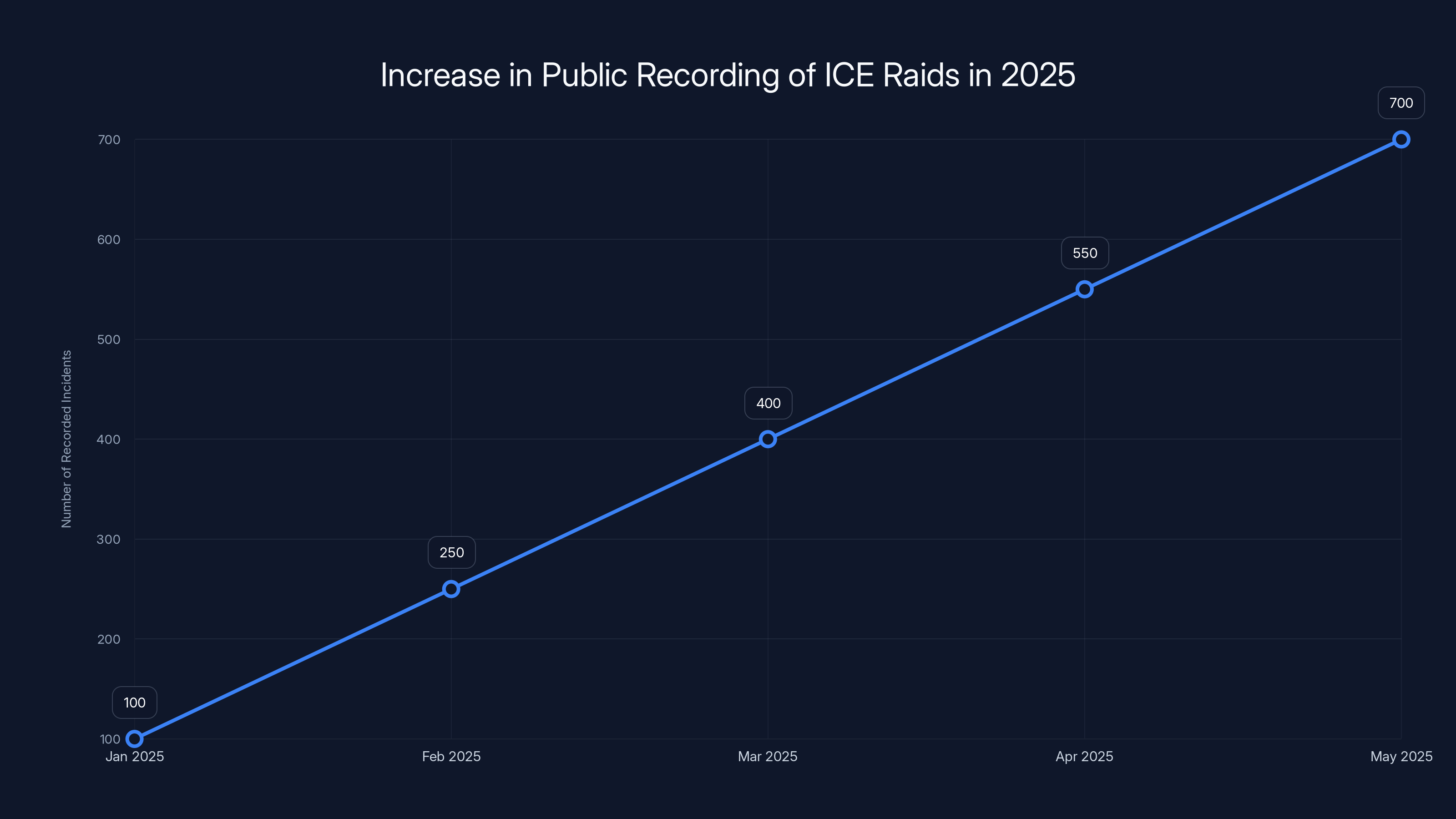

The number of recorded ICE raids increased dramatically in early 2025, highlighting the shift in public engagement and visibility. (Estimated data)

The Economic Impact: Who Benefits From Surveillance?

One thing that doesn't get discussed enough is the economic dimension of surveillance. Who makes money from surveillance? Who loses money when surveillance is distributed?

Government surveillance has always been expensive. You need cameras, storage systems, personnel to monitor footage, courts to review requests. The government pays for all of this, and it's increasingly expensive.

Private surveillance is often cheaper and more profitable. Companies like Amazon, Google, and Meta have built surveillance into their business models. They collect data, they store it, they profit from it.

Citizen surveillance, the kind happening in 2025, is different. It's distributed. It's not monetized, at least not officially. People are doing it because they believe in it, not because they're paid.

From the government's perspective, this is threatening for economic reasons too. If information about government conduct becomes freely available through citizen documentation, the government can't charge for FOIA requests anymore. It can't control the flow of information through official channels.

From the perspective of surveillance companies, citizen documentation doesn't directly threaten their business. But it does complicate things. If people are using social media to organize surveillance of government, they're doing it on platforms owned by Amazon, Google, Meta. Those companies have a complicated relationship with government requests for information.

This economic angle reveals something important: surveillance isn't just about power and control. It's about money. Who profits from information flows matters.

What This Means for Police Accountability Going Forward

Assuming the government doesn't successfully criminalize the recording of police, what does the landscape look like going forward?

Police departments are probably going to have to accept that they're being filmed, constantly. This is going to require adjustments in training, policy, and culture.

Some police departments have already figured this out. They provide clear uniform identifiers. They have policies about body camera footage that encourage transparency rather than fighting it. They focus on training officers to conduct themselves properly when they know they're being filmed.

Other departments are fighting it. They're arguing against body camera footage being released. They're defending officers against public criticism of their conduct. They're trying to maintain information control.

The evidence from places that have adopted transparency is interesting. In some cases, transparency seems to increase public trust. If the department releases body camera footage and the officer's conduct looks professional, that reassures the public. If the footage reveals misconduct, well, that's a problem, but at least everyone knows what happened.

The evidence from places that fight transparency is less positive. They create a perception of corruption, even when that perception might not be warranted. Secrecy makes people suspicious.

Moving forward, police departments that embrace transparency and accountability will probably build more public trust than those that fight it. But this is a slow process. It requires cultural shifts, not just policy changes.

The Practical Challenges: Sustaining Citizen Surveillance Networks

Here's something worth thinking about: sustainable citizen documentation is actually quite difficult.

In the early days of "ICE watch" in 2025, there was high energy and high participation. People were mobilized. They cared deeply about the issue. They organized through social media. It seemed like a durable movement.

But sustaining that kind of activity is hard. It requires people to put time and effort into something without getting paid. It requires coordination across large groups of people. It requires people to put themselves at risk of being identified or targeted.

Over time, participation tends to decline. The people who were most engaged at the beginning burn out. Newer people don't develop the same commitment. The movement plateaus.

This is why professionalization matters. Some of the successful documentation networks have moved beyond pure volunteer effort. They've recruited journalists. They've formalized organizational structures. They've created systems for managing large amounts of footage and ensuring it doesn't disappear.

Without that professionalization, citizen surveillance networks tend to become brittle. They depend on a few highly committed people. They lack the institutional knowledge to adapt to changing circumstances.

The networks that will probably have the most impact going forward are the ones that figure out how to sustain themselves. That might mean nonprofit organizations providing support. It might mean journalists embedded in the networks. It might mean technology platforms creating easier tools for documentation and archiving.

Right now, a lot of this is being done informally. But the gap between informal and formal isn't that large. If some of these networks invest in infrastructure, they could become much more durable and impactful.

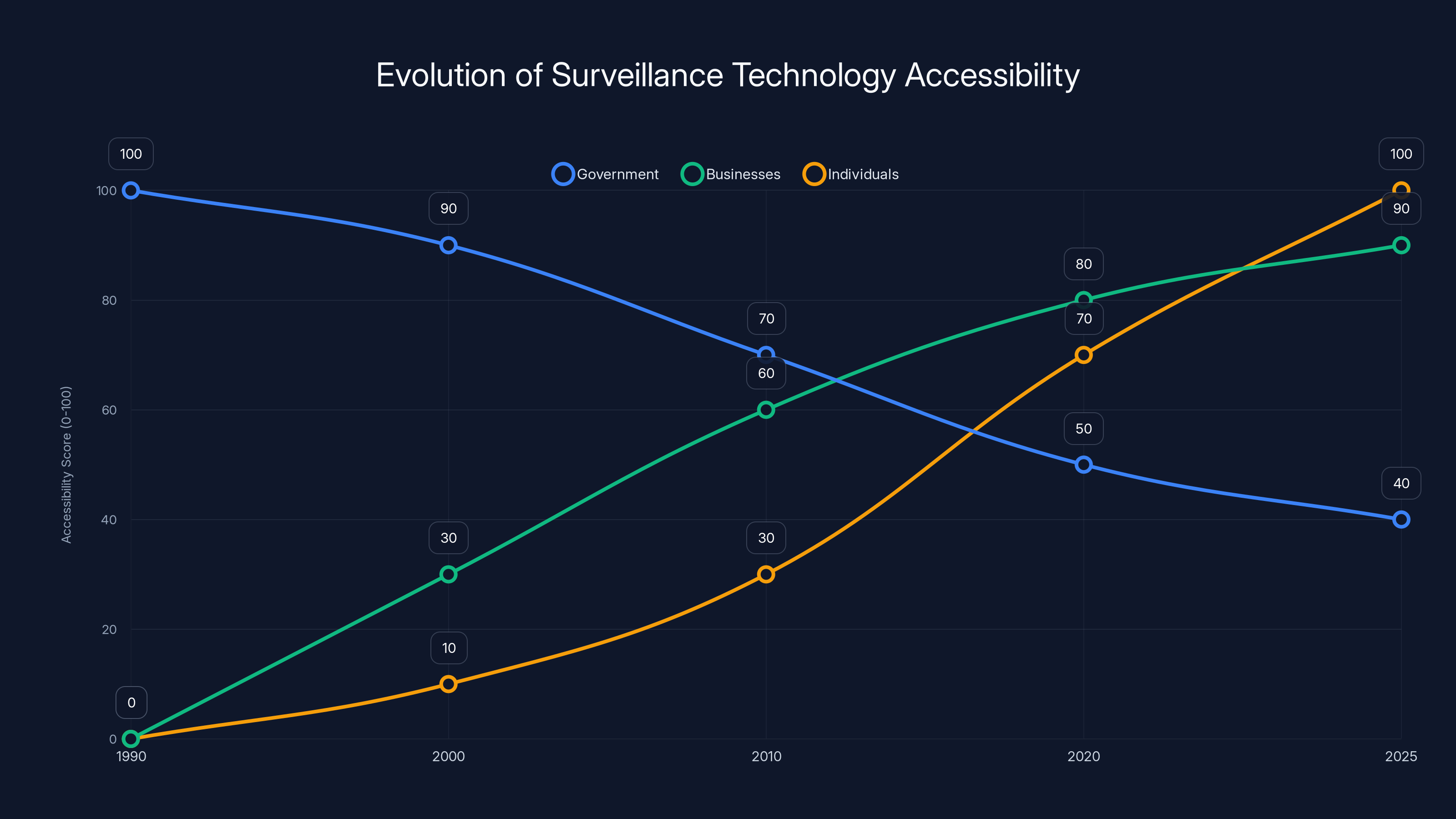

Estimated data shows the democratization of surveillance technology from government to individuals over the years, highlighting the shift in information power dynamics.

The Data: What We Know About the Scale

There aren't a lot of reliable statistics about the scale of citizen documentation of police in 2025. It's hard to measure something that's so distributed and happening across so many platforms.

But some numbers give us a sense of the phenomenon:

Multiple "ICE watch" accounts on Instagram had followings in the hundreds of thousands by mid-2025. Some had over 500,000 followers. These accounts were posting regularly, sometimes multiple times per day.

Apps for tracking immigration enforcement were downloaded hundreds of thousands of times before being removed from official app stores.

Social media hashtags dedicated to documenting enforcement activity had millions of posts across platforms.

Online communities dedicated to sharing video footage of police and enforcement activity had hundreds of thousands of members.

Civil rights organizations reported receiving thousands of videos from the public documenting enforcement activity, more than they could possibly review or process.

By any measure, the scale is significant. This isn't a small niche activity. Millions of people are participating in documenting government conduct in some form.

What's harder to measure is the impact of this documentation on actual policy or outcomes. Has increased documentation changed police behavior? The honest answer is: probably, but we don't have clear evidence about how much or in what ways.

There are some clear cases where documentation led to officer discipline or prosecution. There are cases where documentation raised awareness about issues that led to policy changes. But these are anecdotal. There's no comprehensive study of impact.

This is an area where better data collection could actually be really useful. If organizations were systematically tracking outcomes associated with documented incidents, we could learn what kind of documentation actually drives change.

The Future: Where This Goes From Here

If you're trying to predict where this goes, there are a few plausible scenarios.

Scenario One: The government successfully criminalizes recording through legislation. The Protecting Law Enforcement From Doxing Act passes or similar laws get enacted. Criminal penalties for recording police become real. In this case, you'd expect recording to become more covert. People would use encrypted platforms. They'd be more careful about identifying officers. The activity doesn't go away, but it becomes harder to share information.

Scenario Two: The government tries to criminalize recording, but it fails. Courts block the legislation. The attempts at prosecution don't result in convictions. Recording continues and probably accelerates because people see that the government's threats are empty.

Scenario Three: There's some kind of compromise. The government accepts that recording is inevitable, but negotiates protections for officer safety. Maybe there's an agreement that certain identifying information isn't shared. Maybe there are limits on livestreaming during active operations. Maybe platforms create special handling for sensitive footage. This would require significant shift in the government's current stance.

Scenario Four: Technology changes the game. New tools emerge that make it even easier to document at scale. Or, alternatively, new AI tools make it easy for the government to automatically detect and remove footage of enforcement activity from social media. The arms race continues.

My guess is that some combination of these happens. The government probably doesn't succeed in fully criminalizing recording, but it does make it riskier. Technology continues to evolve, creating new tools and new problems. And gradually, recording of police becomes even more normalized than it already is.

In the long term, I think this is a problem that the government solves by changing behavior, not by changing laws. The police departments that are most resistant to transparency will probably face the most public pressure. The ones that adapt will probably build more trust.

But that's not a quick process. That's generational change.

What About Safety Concerns?

One thing the government argues, and it's not entirely without merit, is that identifying federal agents can put them at risk.

This is a real concern. If someone sees an officer's identifying information and decides to threaten them or their family, that's a crime and a genuine harm. The officer's family didn't choose to be in a government job. They shouldn't be harassed because of what their relative does for work.

But here's the distinction: there's a difference between acknowledging that safety concerns exist and using safety concerns as a blanket justification for preventing all documentation.

The court system already has tools for addressing actual threats. If someone threatens an officer or their family, that's a crime. If someone coordinates harassment of an officer, that's a crime. If someone publishes information with the intent of inciting violence, that's arguably incitement.

But the fact that some bad actors might use documentation for harmful purposes doesn't mean documentation itself should be illegal. By that logic, you could ban publishing anything, because someone might use the information harmfully.

The question becomes: how do you protect officer safety without preventing accountability? It's a real tension, and there's probably not a perfect answer. But it's not solved by making all recording illegal.

It's probably solved by having clear consequences for actual harassment while accepting that documentation and identification will happen. It's accepting that some officers might be at risk as a cost of transparency, and making sure those officers have appropriate security resources.

The Philosophical Endgame: Who Owns Transparency?

At the deepest level, what's happening in 2025 is a renegotiation of who owns transparency in a democratic society.

For most of modern history, transparency was something the government controlled. Governments decided what information to release. Citizens requested information through formal channels. The government determined what was national security, what was private, what was public.

This system was based on an assumption that the government is the legitimate arbiter of what information should be public. The government knows what's safe to release. The government knows what might compromise operations.

What's happening now is the public challenging that assumption. Citizens are saying: we're going to be the arbiters of what's public. We're going to decide what deserves transparency. We're going to document government conduct ourselves.

The government's response has been to say: no, that's dangerous, that's doxing, that's harassment. But what it's really saying is: we want to keep control of information about our own conduct.

That's a fundamental power struggle. It's not really about whether particular pieces of information should be public. It's about who gets to decide.

My guess is that this struggle will continue for years, and ultimately, the public is going to win. Once information technology is distributed enough that everyone has a camera, the government can't maintain a monopoly on documentation. The best it can do is manage the relationship.

The government that accepts this fastest and builds institutions around transparency will probably serve the public better than the government that fights it. But that adaptation is hard. It requires letting go of power.

Key Takeaways: What You Should Know

So here's what matters:

First, the right to record police in public is well-established and constitutional. It's not doxing. It's not violence. It's free speech.

Second, the scale of citizen documentation in 2025 is genuinely new. The technology and organization have reached a critical mass where this isn't fringe behavior anymore. It's mainstream.

Third, the government's response, while understandable from a security perspective, represents a threat to accountability. If the government can criminalize recording its own conduct, we've given up something significant.

Fourth, this is probably a permanent shift in power dynamics. Surveillance is going to go both ways now. That's the new normal.

Fifth, institutions that adapt to this reality will do better than institutions that fight it. Police departments that accept transparency will probably serve their communities better than ones that don't.

Finally, this shows that technology doesn't automatically favor centralized power. Sometimes it distributes power. Sometimes it takes power from institutions and gives it to people. That's what we're seeing.

FAQ

What is the legal right to record police in public?

The right to record police conducting public business in public spaces is constitutionally protected under the First Amendment. Courts have consistently held that citizens have a right to film police, provided they're not interfering with official operations or obstructing the police officer's duties. The reasoning is straightforward: the public has a right to observe and document government conduct. Police officers, when performing official duties in public, have a reduced expectation of privacy compared to private citizens. This protection extends to sharing that footage online and identifying the officers in it, provided the person sharing isn't engaging in actual harassment or incitement.

Is identifying federal agents online considered "doxing"?

No, according to civil liberties experts and legal scholars. Doxing specifically refers to researching and publishing private information about someone with intent to harass or enable harassment. Identifying someone in a public space performing government functions is not doxing. It's documentation. The information being shared isn't private. Many of these officers have social media profiles themselves. The information is often found through public records or government databases. Calling public accountability "doxing" misapplies the term and obscures the actual issue, which is about government transparency, not privacy invasion.

What changed in 2025 that made citizen recording more significant?

The scale and coordination of citizen documentation reached a new level in 2025 due to several factors: high-profile federal immigration enforcement actions drew public attention, smartphone technology made recording ubiquitous, social media platforms made sharing instant and reach massive, and organized networks like "ICE watch" groups provided infrastructure for coordinating documentation across entire cities. What was previously something activists did occasionally became something ordinary people did routinely. The combination of motivation, technology, and organization created conditions where documenting government conduct shifted from marginal activity to mainstream practice.

Why does the government claim that recording agents is a safety risk?

The government argues that identifying federal agents creates safety risks because that information could be used for harassment, threats, or violence against the officers or their families. This is a legitimate concern in the abstract. Actual threats against officers are serious crimes. However, the government appears to be using safety concerns as a blanket justification for preventing all recording and documentation, even when the documentation itself poses no safety risk. The tension is real, but it's not resolved by making all recording illegal. It's resolved by having consequences for actual harassment while accepting that transparent documentation will occur.

Have there been successful prosecutions of people for recording police?

There have been limited prosecutions specifically for recording police, though the government has certainly tried. In 2025, the government indicted three people for allegedly following an ICE agent home and livestreaming his address on Instagram. However, prosecution for recording itself is rare because the constitutional right is well-established. What the government seems to be testing is whether enhanced charges (stalking, harassment, domestic terrorism) can be applied when recording is combined with other conduct. So far, these expanded legal theories haven't been tested extensively in courts.

How does this compare to other countries' handling of citizen recording of police?

Other countries have largely accepted that citizen recording of police is inevitable and adapted their policies accordingly. In the UK, recording police is normalized and accepted. In Hong Kong, citizens explicitly use recording as a form of accountability, and the government hasn't been able to prevent it despite efforts. In Brazil, police recording by bystanders is common enough that it's a major factor in controversial incidents. The United States is distinctive in 2025 for the extent to which the government is actively fighting citizen documentation through legal threats and prosecution, rather than accepting it as a new normal.

What practical steps should people take if they want to document police activity?

Civil liberties organizations recommend: stay at a safe distance and don't interfere with police operations, record both video and audio, keep your phone stable, remain calm and don't engage with officers, consider uploading footage to a secure cloud service immediately in case your phone is confiscated, be aware of local privacy laws regarding consent for recording, understand that you have the right to record but be respectful about how you use that information, and consider sharing footage with established organizations rather than immediately posting it on social media, where it might be removed or could be misinterpreted.

Why is this trend more significant than previous instances of police recording?

Previous viral instances of police recording, like the Rodney King video or George Floyd footage, were important for exposing specific incidents of misconduct. What's different in 2025 is the systematic, coordinated nature of documentation. It's not just that people are recording incidents. They're organizing to track enforcement patterns across entire cities. They're using apps and social media to coordinate real-time responses. They're maintaining archives of footage. This represents a shift from isolated incidents being documented to ongoing surveillance of government conduct becoming normal. The scale and coordination make the power imbalance shift more comprehensive and structural.

What happens if the government successfully passes legislation criminalizing recording of police?

If legislation criminalizing recording passes, recording would become more covert. People would use encrypted platforms rather than public social media. Documentation would likely continue but become harder to access and share. Legal experts suggest this could also lead to constitutional challenges, as such legislation would likely violate First Amendment protections. The history of governments trying to suppress information technology suggests that criminalization would probably not stop the behavior, just make it harder to coordinate and share. Enforcement would likely be selective, creating concerns about discrimination in who gets prosecuted.

Related Articles

- Government Spyware Targeted You? Complete Action Plan [2025]

- Trump Administration Seeks to Deport Hate Speech Researcher: Legal Battle Explained [2025]

- Trump's Mass Deportation Machine: How Federal Law Enforcement Replaced Militias [2025]

- Apple Pauses Texas App Store Changes After Age Verification Court Block [2025]

- Exploring Sharesome: A Deep Dive into the Adult Social Media Platform [2025]

![Surveillance Goes Both Ways: How Citizens Are Recording Police [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/surveillance-goes-both-ways-how-citizens-are-recording-polic/image-1-1767008196620.jpg)