Saturn-Sized Rogue Planet Found in Einstein Desert: What This Discovery Means

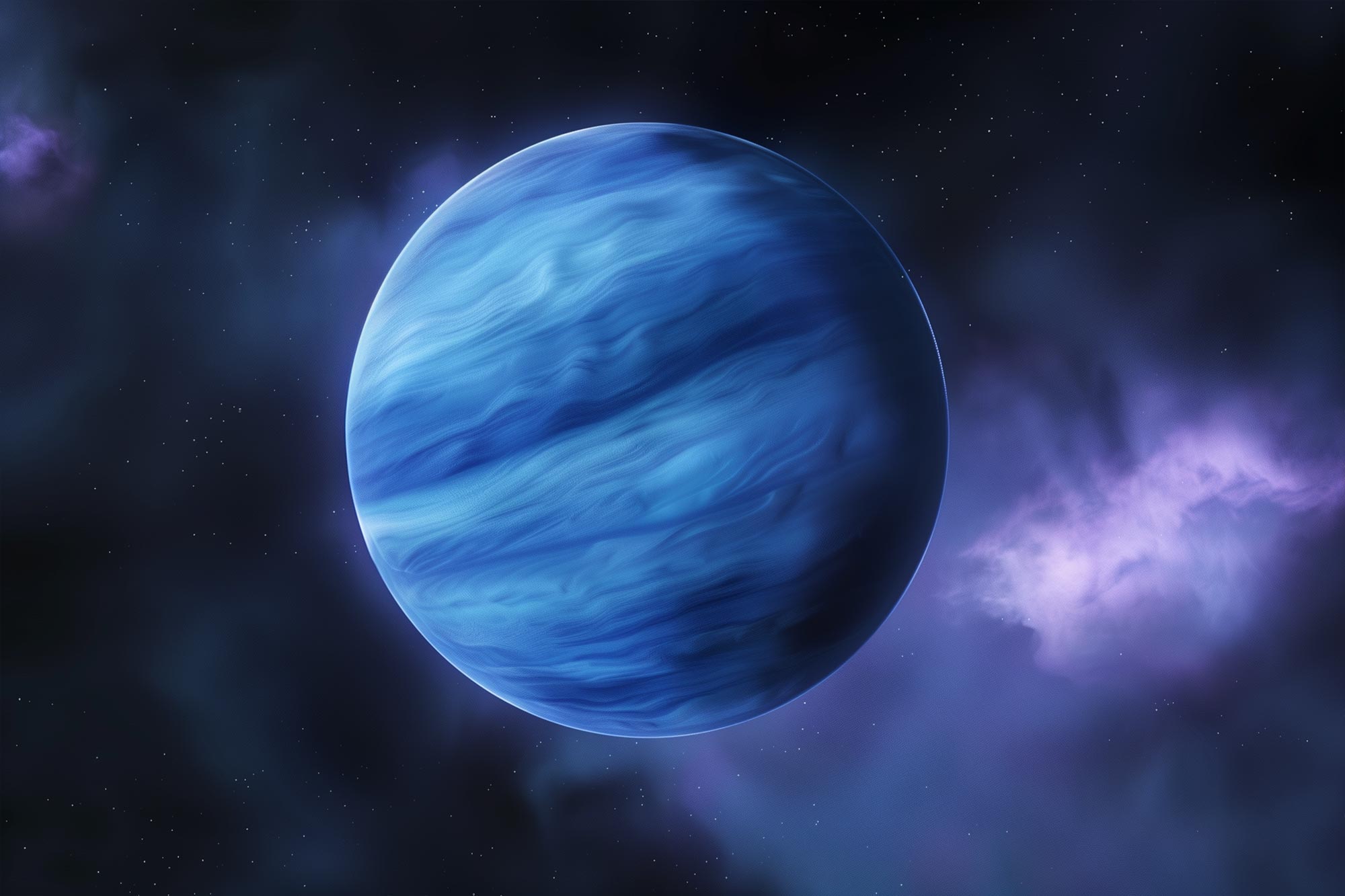

Something wild just happened in the cosmos, and barely anyone noticed. In May 2024, astronomers spotted a Saturn-sized planet floating alone through interstellar space, in a region they'd been hunting in for years called the "Einstein desert." This isn't some distant future discovery—it happened, the data's been analyzed, and the implications are reshaping how we think about rogue planets.

Here's the thing: we've been finding exoplanets for decades now, mostly the easy ones orbiting stars. But this one? It's not orbiting anything. It's just drifting out there, having been ejected from its original system long ago or formed in isolation. And the fact that we found it in the Einstein desert—a gap in the data scientists thought might be imaginary—just proved something real about how planets form.

I'll walk you through what happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about the cosmos.

The Einstein Desert: Why Astronomers Were So Puzzled

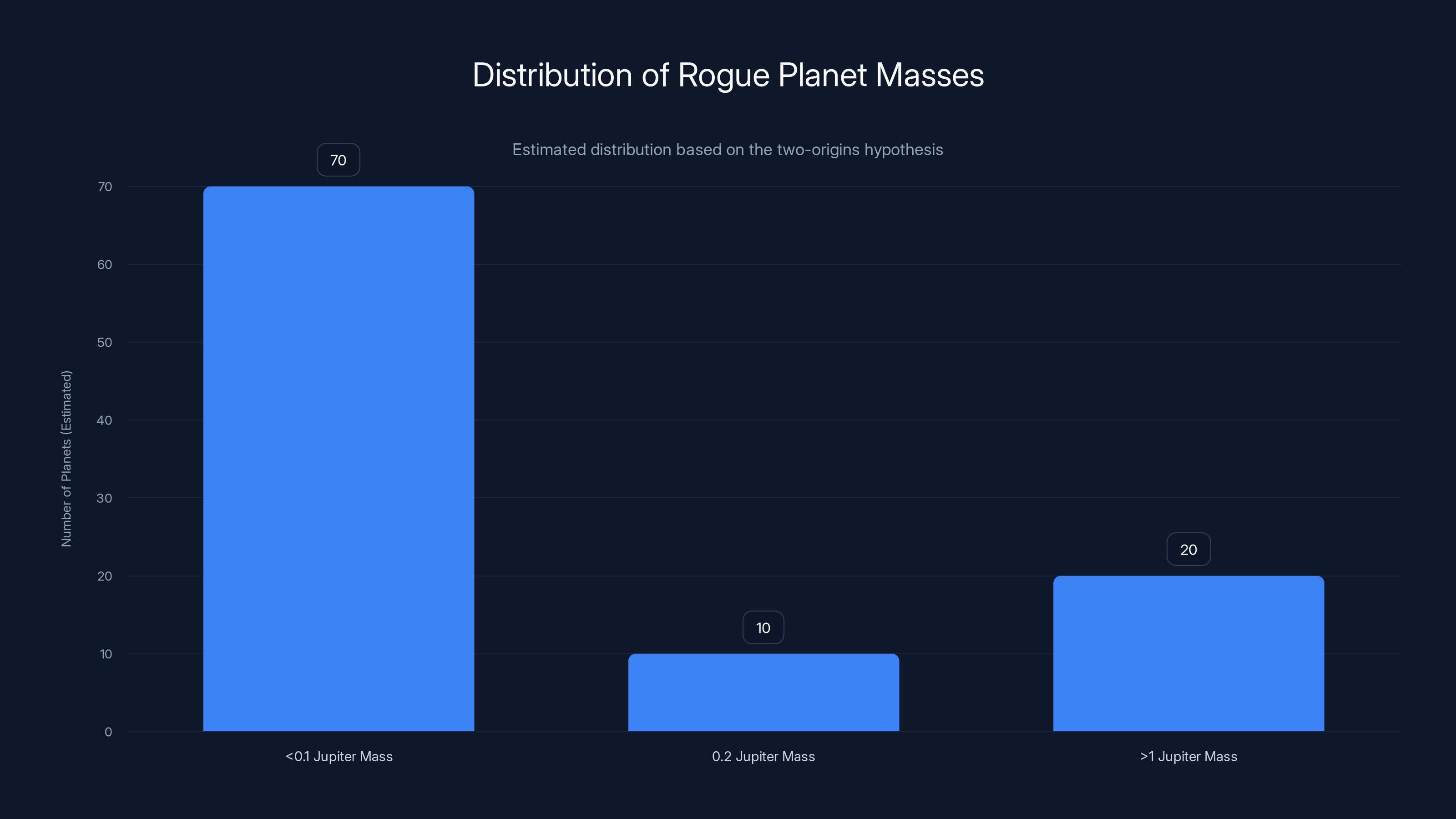

Imagine looking at a graph of rogue planet masses and finding a giant empty space in the middle. Not because there are no planets there, but because we hadn't found any yet. That's the Einstein desert.

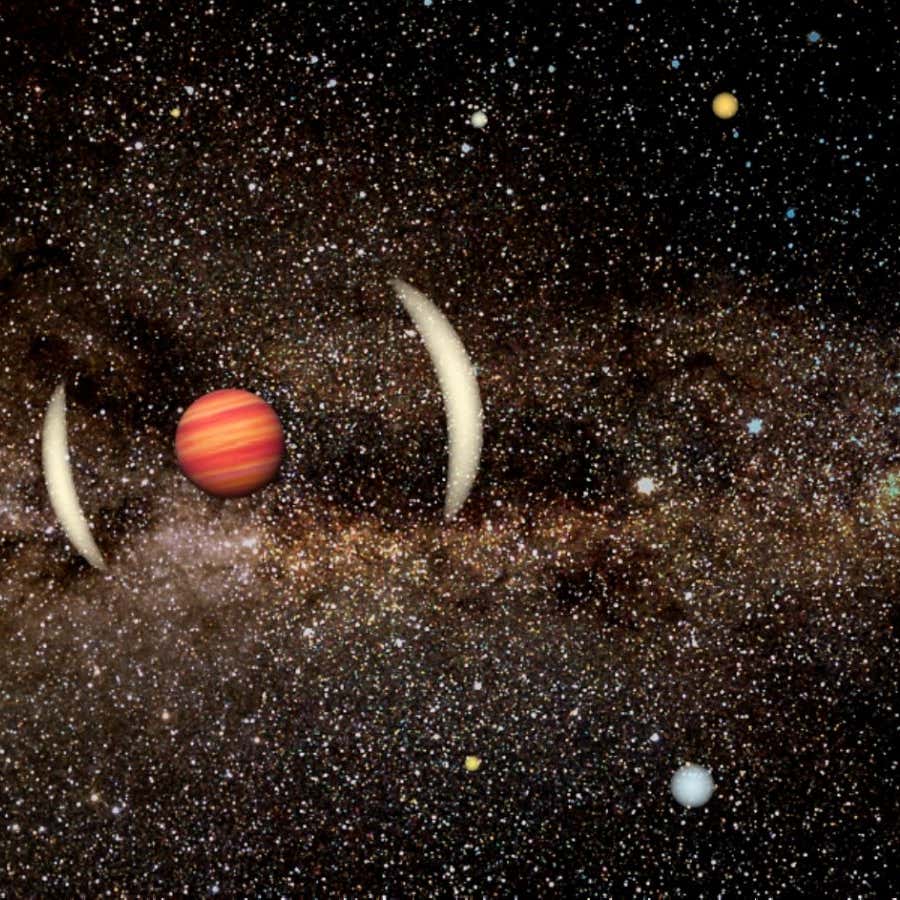

Since we started using microlensing to detect planets, we've found roughly two distinct clusters of rogue planets. One cluster contains relatively small objects, with Einstein rings (the gravitational lensing halos they create) on the smaller side. Another cluster has massive planets—true gas giants comparable to Jupiter or larger. Between these two clusters? Nothing but empty space on the graphs.

For years, scientists debated whether this gap was real or just an artifact of small sample sizes. With only dozens of microlensing events cataloged (because they're genuinely rare), it's hard to know if you're seeing a real pattern or just statistical noise. Some researchers argued the desert was real and pointed to something fundamental about how rogue planets form. Others thought we simply hadn't found enough planets yet.

The discovery of this Saturn-sized world in the desert settles that question. Now we know the gap exists. More importantly, it tells us something profound about planetary origins.

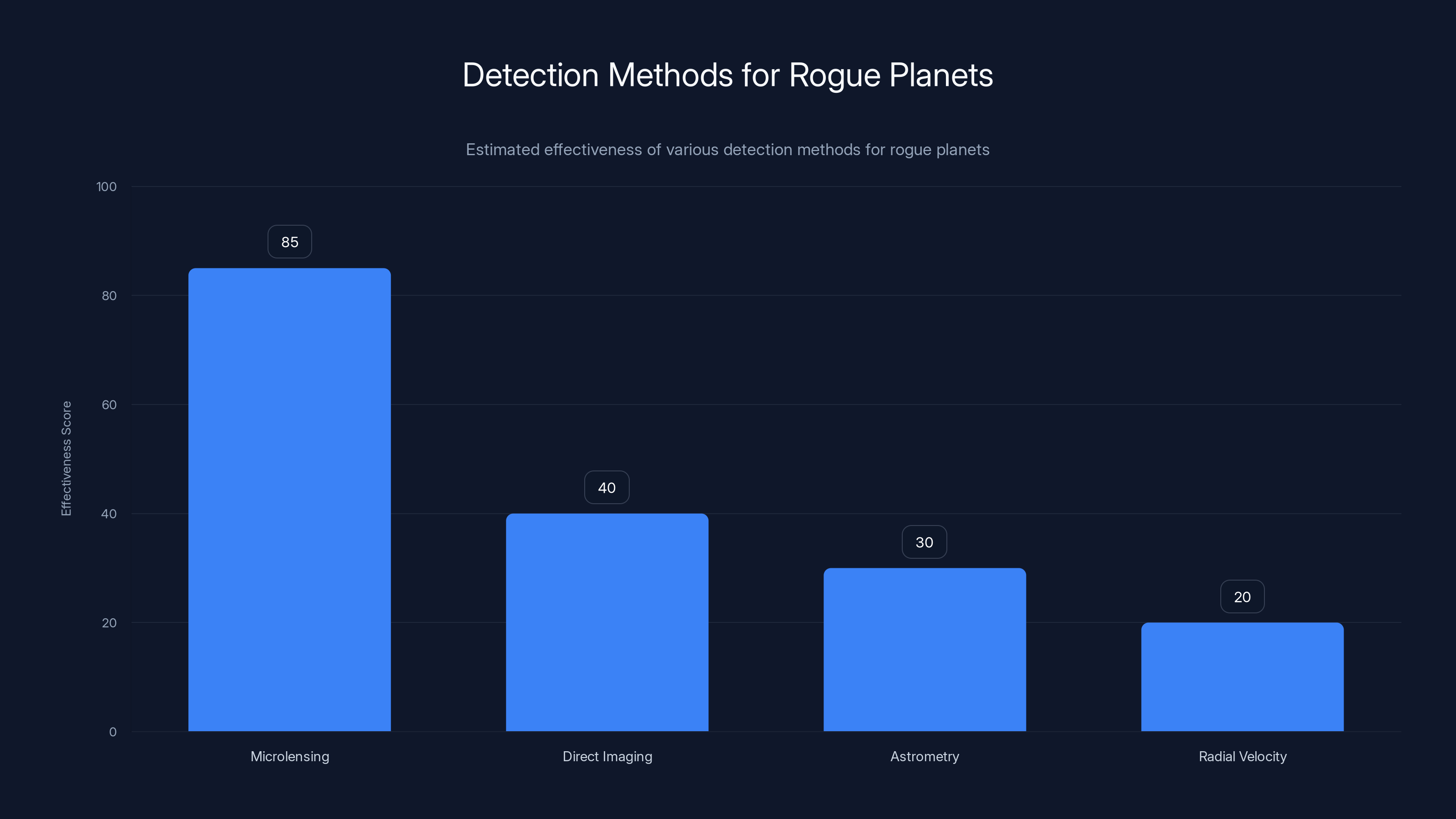

Microlensing is the most effective method for detecting rogue planets due to its ability to identify planets without host stars. Estimated data based on typical detection capabilities.

How Rogue Planets Actually Get Ejected: The Two Paths

Let's talk about how planets end up alone in space. There are fundamentally two different pathways, and they produce very different types of objects.

Path One: Gravitational Ejection from a System

This is brutal and elegant. Imagine a young star system with multiple planets forming around it. As they orbit and gravitationally interact, something goes wrong. Maybe a giant planet swings through the inner solar system. Maybe a passing star wanders too close and disrupts the gravitational dance. In rare cases, these interactions can fling a planet completely out of orbit, sending it hurtling into the void at significant velocity.

When this happens, you'd expect the ejected planet to be pretty much like any planet that stayed in the system. It could be small and rocky, medium-sized and icy, or a massive gas giant. The mass doesn't really matter—what matters is whether it got kicked out. In fact, studies of real exoplanet systems suggest that ejection events might be more common than we initially thought. Many systems probably lose planets this way.

This mechanism is well-understood through computer simulations. When you model young planetary systems with realistic interactions, you consistently see planets getting ejected into interstellar space. It's one of the messier aspects of planetary system formation that doesn't get as much attention as it deserves.

Path Two: Direct Formation as a Substellar Object

The second mechanism is completely different and weirder. Instead of ejection, you get direct formation.

Here's how it works: Gas clouds collapse to form stars. That's standard stellar formation. But sometimes, in the same molecular cloud, a smaller clump of gas collapses that never quite accumulates enough mass to become a star. It reaches maybe 50 to 80 Jupiter masses—massive enough to be a true gas giant, but not massive enough to ignite hydrogen fusion in its core (which is what makes something a star). These objects are called brown dwarfs, and they're genuinely abundant throughout the galaxy.

But here's the kicker: what if the collapse happens in isolation? What if you get a gas cloud that forms a planetary-mass object without ever being part of a star system? The object that emerges would be indistinguishable from a free-floating planet, except for its origin. It would have formed in loneliness, never knowing the embrace of a star's radiation, never developing in a protoplanetary disk.

This pathway strongly favors producing more massive objects. Gravitational collapse tends to produce larger masses than you'd find among ejected planets. So if you could distinguish between these two origins, you'd expect ejected planets to span a range of masses, while directly formed objects would cluster at the higher end.

Microlensing: The Technique That Found This Planet

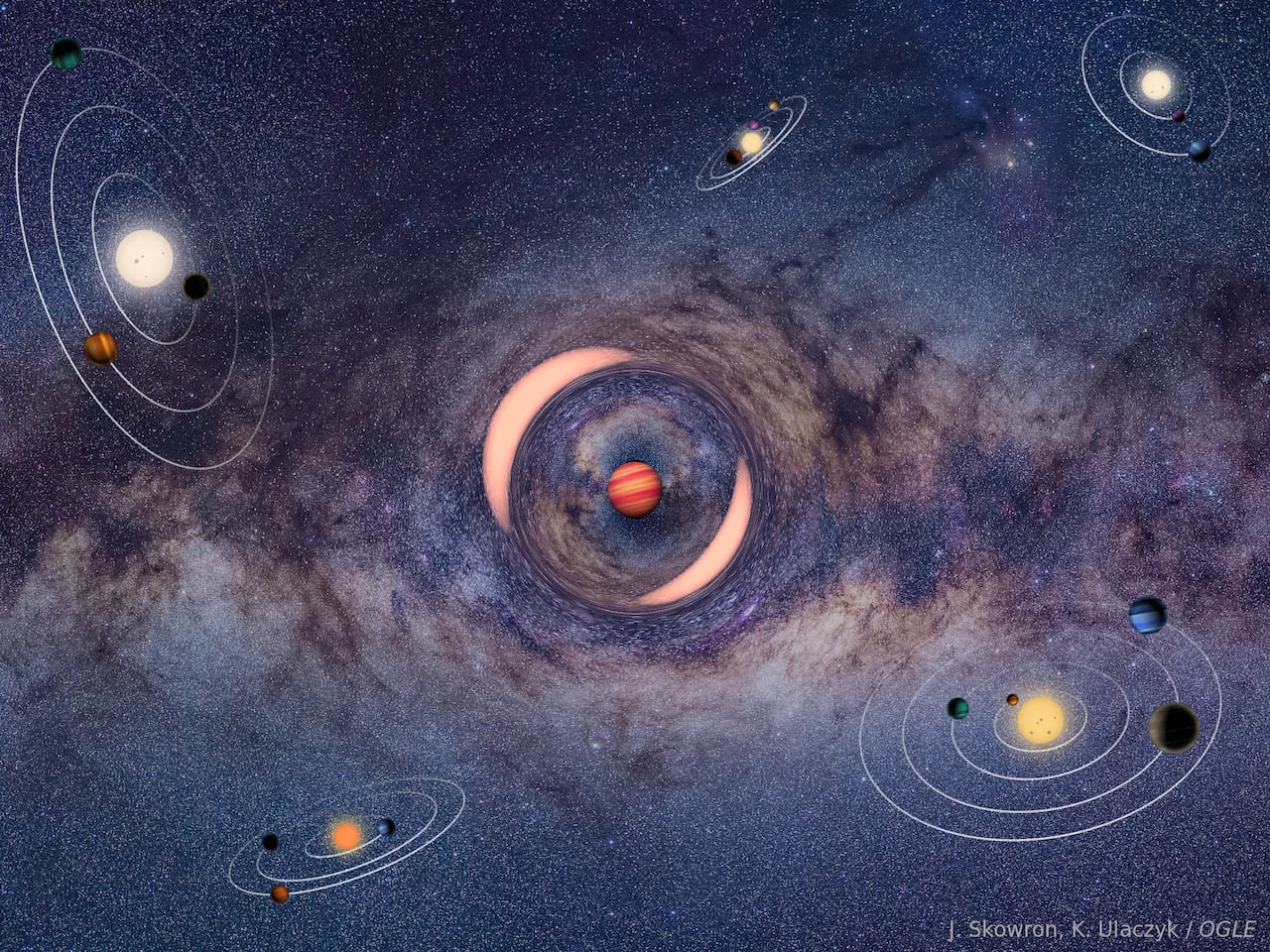

You can't see a rogue planet directly. It's not orbiting a star, so it's not blocking starlight in any regular pattern. It doesn't have a star's radiation heating it. It's essentially invisible in every traditional sense.

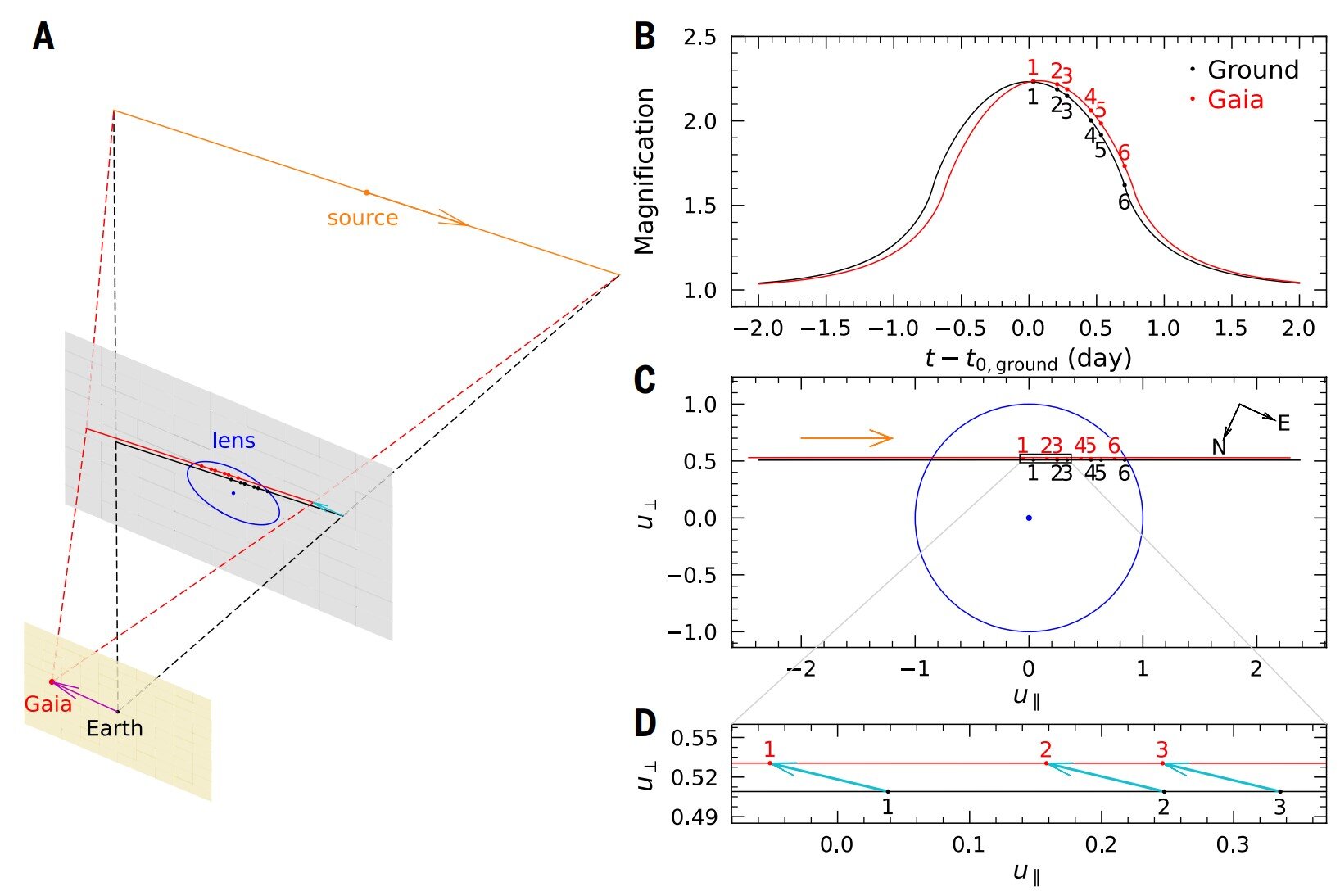

Microlensing works because of Einstein's prediction that massive objects curve spacetime, which bends light. When a planet passes directly between us and a distant star, the planet's gravity bends the starlight coming from that star, magnifying it. For a few hours or days, the distant star appears brighter than normal. The magnification factor depends partly on the planet's mass and distance.

The brilliant thing about microlensing is that it can detect planets that regular methods can't. An exoplanet orbiting a star requires repeated observations to detect its periodic blocking or the star's wobble. A rogue planet crosses the line of sight maybe once, never again. Microlensing catches that single event.

But there's a catch. Microlensing doesn't directly tell you a planet's mass. It tells you the size of the Einstein ring—the circular halo of magnified light—but determining actual mass requires knowing the distance to the lensed star and how massive that star is. Without this information, you're stuck.

That's where this particular discovery becomes special. In May 2024, two ground-based telescope networks—the Korea Microlensing Telescope Network (KMT) and the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE)—both detected the same microlensing event. They gave it different names: KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516, respectively. But here's where fortune intervened.

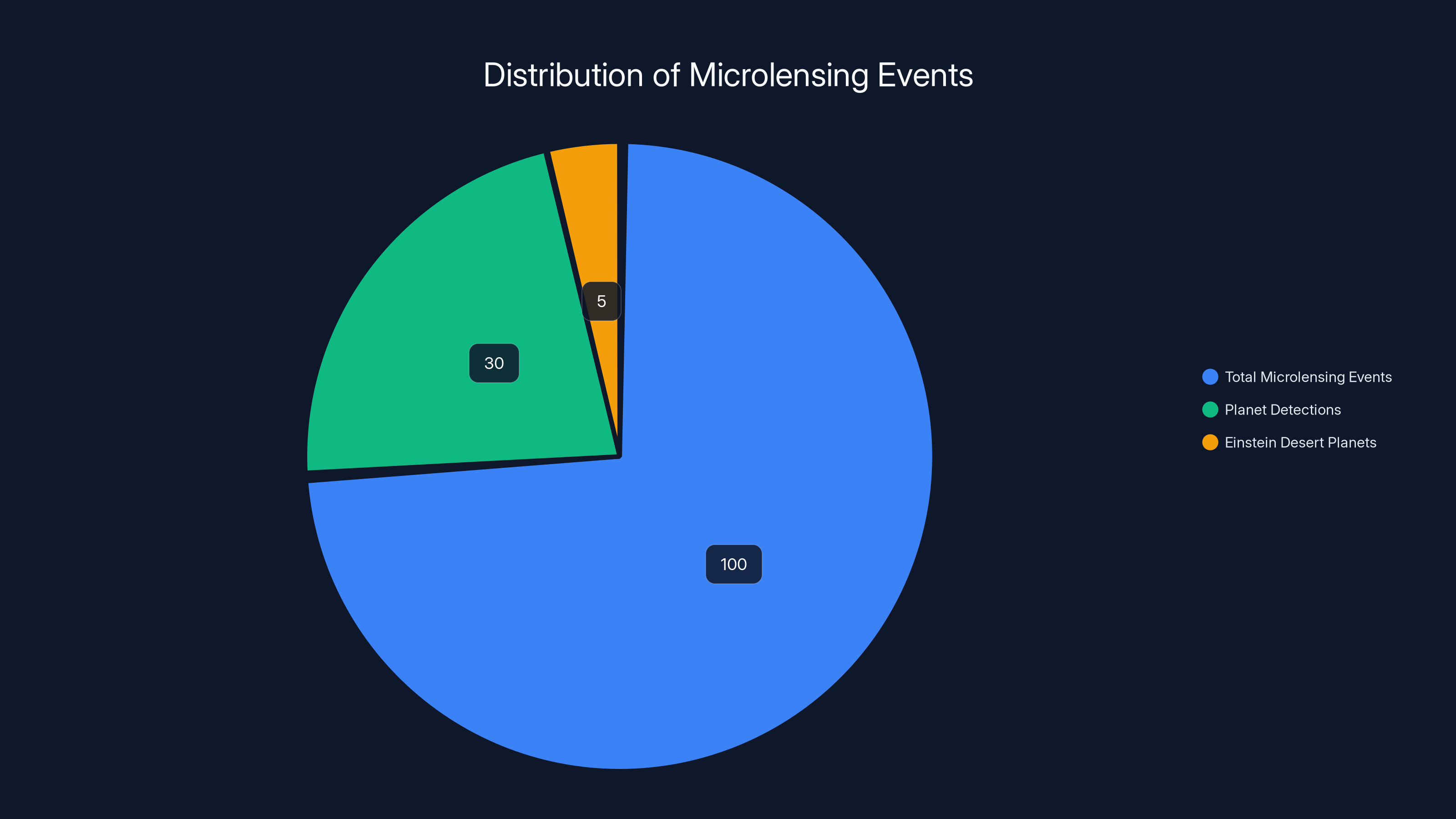

Estimated data shows that out of approximately 100 microlensing events, around 30 involved planet detections, with only a few filling the Einstein desert gap. Estimated data.

The Gaia Advantage: When the Cosmos Aligns

The European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope was oriented perfectly to observe this event from its vantage point at the L2 Lagrange point, about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth.

Being that far away matters enormously. When Gaia observed the microlensing event six times over a 16-hour period, its perspective was sufficiently different from Earth-based telescopes to measure parallax—the apparent shift in position of the planet due to Earth's and Gaia's different locations in space. The peak of the event's brightness occurred nearly two hours later in Gaia's observations compared to Earth telescopes, precisely because of this distance.

This time difference allowed researchers to calculate the parallax and thus determine the actual distance to the system. Combined with other observations of the background star (which turned out to be a red giant in the galactic bulge), they could determine the star's properties and size. With the parallax known and the Einstein ring's size measured, the math became possible. The planet's mass came out to roughly 0.2 Jupiter masses—almost exactly Saturn's mass.

This wasn't guaranteed. The star could have been farther or closer, larger or smaller. But the combination of ground and space observations, plus the fortunate geometry of Gaia's orientation, made the calculation possible.

What Saturn-Mass Tells Us About Planet Origins

The planet's mass matters more than you might think. At 0.2 Jupiter masses—roughly Saturn-scale—it lands squarely in the middle of what astronomers had been calling the Einstein desert.

Remember those two clusters? The lower-mass cluster contains planets mostly under 0.1 Jupiter masses. The higher-mass cluster starts above 1 Jupiter mass and goes way up. Between them sat this empty gap.

Finding a planet right in the middle of that gap proved the gap wasn't fictional. It's a real feature of the rogue planet population. More importantly, it's consistent with the two-origins hypothesis.

The lower-mass cluster likely consists mostly of ejected planets—objects that were flung out of systems during planetary dynamics. These should span a range of masses depending on the parent system's properties. You'd expect to find some small rocky bodies, some gas giants, but they'd cluster at the lower end because most planetary systems don't contain Jupiter-mass planets.

The higher-mass cluster probably represents directly formed objects—brown dwarfs and substellar objects that formed through gravitational collapse in molecular clouds without ever being part of a star system. These naturally form at higher masses because the formation mechanism itself favors larger objects.

The gap between? That's where the signatures of the two origins become clear. Few ejected planets are massive enough to join the second cluster. Few directly formed objects are light enough to remain in the first cluster. They segregate naturally.

This Saturn-sized world in the desert might represent an unusual ejection event or an interesting borderline case. It proves both clusters exist and suggests something real drives their separation.

The Statistical Mosaic: Building Evidence from Rare Events

Microlensing events are genuinely rare. Earth-based surveys have cataloged maybe a few hundred microlensing events total over the decades. Of those, maybe a few dozen involved clear planet detections. This sample size makes statistical analysis challenging.

Yet patterns have emerged. Researchers have built statistical models incorporating collections of these events, looking for trends in Einstein ring sizes, magnification factors, and other measurable properties. These models suggested something interesting: the population might have distinct subgroups.

Adding one more planet to such a small sample might seem insignificant. But this particular planet fills a gap in a crucial diagnostic—the Einstein desert that had been debated for years. It's like finding a missing puzzle piece that confirms the picture.

Future observations will likely find more planets in the desert. The discovery pathway is now clear: look for microlensing events, measure their properties carefully, and add to the statistical picture. With enough additional data points, astronomers can start distinguishing definitively between ejected and directly formed populations.

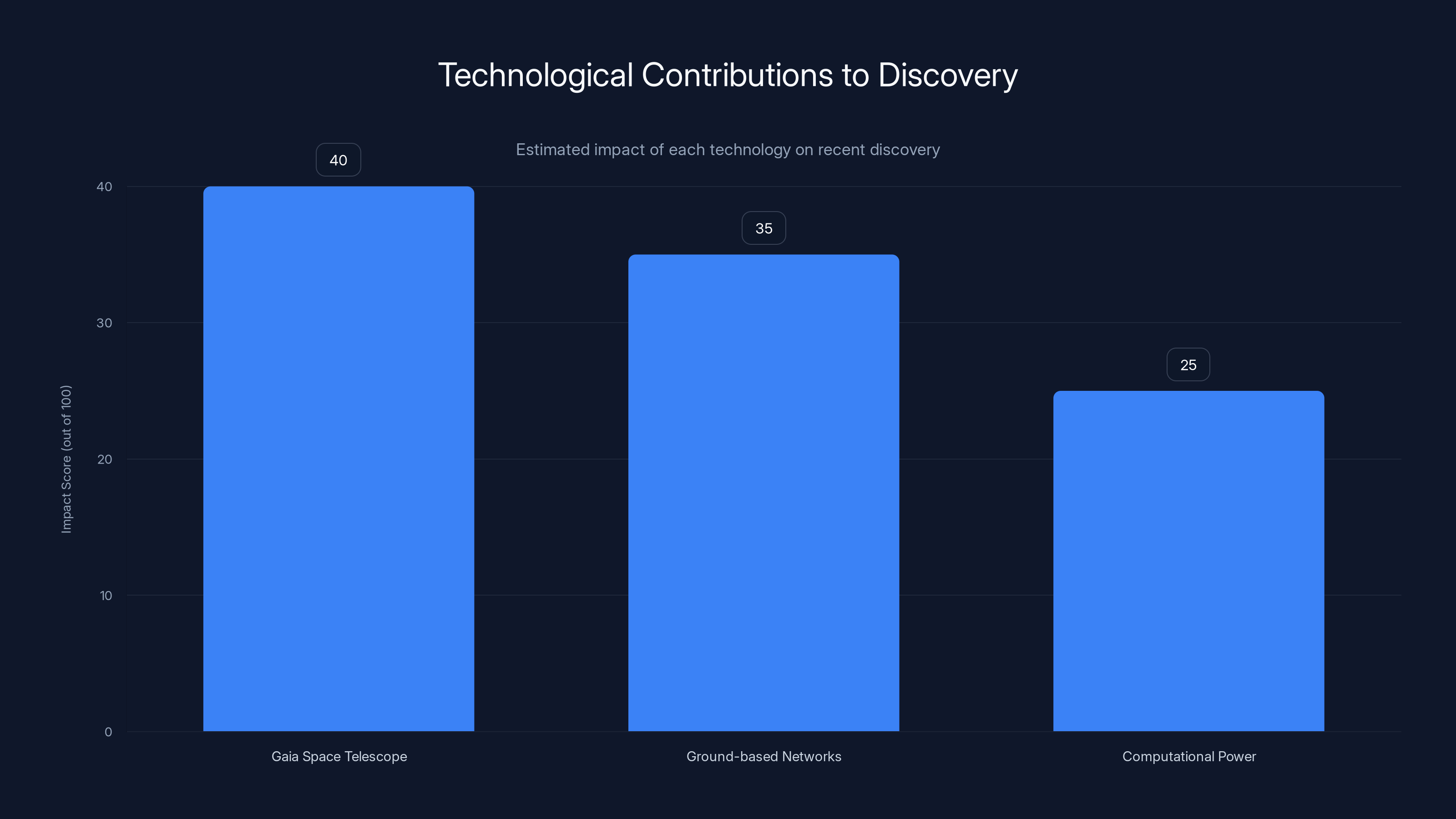

The Gaia space telescope, ground-based networks, and computational power each play significant roles in enabling new discoveries. Estimated data.

Technological Advances Making This Discovery Possible

This discovery wouldn't have happened five years ago. Several technologies had to converge.

First, the Gaia space telescope had to achieve its current orbit and precision. Gaia measures stellar positions and motions to unprecedented accuracy, and its position at L2 makes it perfect for measuring parallax shifts in microlensing events. Earlier space telescopes couldn't have done this.

Second, ground-based microlensing networks had to mature. KMT and OGLE are the result of decades of refinement, operating multiple telescopes across the globe to catch rare events. Neither network alone would have enough data. Together, they've made microlensing surveys viable.

Third, computational power and statistical methods have advanced. Modern analysis of microlensing data involves sophisticated image processing, parallax calculation, and modeling that would have been impractical twenty years ago.

The convergence of these technologies—space observation, ground-based networks, and computational power—makes discoveries like this possible now. They'll probably become more common as the techniques continue improving.

What This Tells Us About Planetary System Formation

Planetary systems form in protoplanetary disks around young stars. We've observed these disks directly, and we've even spotted evidence of planets forming within them. The process seems straightforward: dust grains collide, accrete, and build up into larger bodies until planets form.

But this process doesn't always keep planets in their original orbits. Gravitational interactions between planets, between planets and the disk, and between the system and passing stars can eject planets.

How frequently does this happen? That's still debated. Some models suggest most planetary systems lose at least one planet during their first few hundred million years. Others suggest it's less common. The population of rogue planets might help answer this question.

If we can count and characterize rogue planets well enough, we can work backward. Given the total number of rogue planets and their mass distribution, we can estimate how many ejection events must have occurred. This connects directly to our understanding of planetary system dynamics.

The alternative origin—direct formation—adds another layer. Brown dwarfs and substellar objects are common throughout the galaxy. Their abundances have been measured reasonably well. If some fraction of these could be classified as planetary-mass objects formed in isolation rather than ejected planets, it changes how we think about planet formation.

Maybe "planet" becomes less about formation mechanism and more about physical properties. A Saturn-mass object formed directly from gravitational collapse is fundamentally different from a Saturn-mass object ejected from a stellar system, despite having similar properties today.

The Challenge of Detection: Why These Planets Stay Hidden

Rogue planets don't emit much radiation. They cooled long ago (if they ever had internal heat sources). They're not illuminated by any star. They just drift through space silently.

Microlensing catches them only by chance—when they happen to pass in front of a distant star whose light we can measure. Miss that window, and the planet remains invisible indefinitely.

This creates a profound observational bias. We're not finding a representative sample of rogue planets. We're finding the ones that happen to cross our line of sight to background stars. In principle, the galaxy could be teeming with rogue planets of all masses, but we'd only see the ones in fortuitous positions.

Future infrared observations might change this. Very young rogue planets (a few million years old) retain significant heat from their formation and might be detectable directly in infrared wavelengths. NASA's James Webb Space Telescope has started finding some isolated planetary-mass objects this way.

But for older objects—anything more than a few hundred million years old—infrared detection becomes impractical. These must be found through microlensing or remain forever unknown.

The rogue planet population we observe is therefore skewed toward objects that pass in front of background stars in the galactic bulge or beyond. This creates interesting selection effects that statisticians must account for when interpreting the data.

Estimated data suggests a significant increase in rogue planet discoveries due to advancements in microlensing and direct imaging techniques.

The Physics Behind the Einstein Desert

Why does the desert exist? Why is there a gap between the two clusters?

The ejection mechanism offers one perspective. When you model young planetary systems and compute which planets get ejected under various dynamical scenarios, you find that smaller planets eject more easily than larger ones. A small terrestrial planet or a Neptune-sized world can be kicked out by gravitational interactions. But a massive Jupiter-scale planet is harder to eject because its own gravity exerts more influence on the system.

Additionally, most planetary systems don't contain truly massive planets. Jupiter-mass worlds are rare. So the population of ejected planets should cluster at smaller masses, simply because that's what's available to eject.

Meanwhile, directly formed objects—brown dwarfs created through gravitational collapse—naturally form at larger masses. Collapse processes favor producing massive objects. You rarely form a 0.2 Jupiter-mass object through gravitational collapse; they typically form larger.

The result is a bimodal distribution: lots of small ejected planets, lots of large directly formed objects, and a desert in between where neither process efficiently produces planets.

This explanation is elegant and probably captures something real. But it's not yet proven. That's where accumulating more planets in the desert becomes important. Each one tests the hypothesis. If the hypothesis is correct, we should eventually map out a clear distribution that makes physical sense.

Future Discoveries and What They'll Reveal

The pace of rogue planet discovery is likely to accelerate. More microlensing surveys are coming online. Gaia continues operating and improving. Ground-based networks keep refining their techniques.

In the next five to ten years, astronomers will probably find dozens more planets in the Einstein desert and its surroundings. Each discovery adds statistical weight. Eventually, the distribution should become clear enough to distinguish definitively between the two formation mechanisms.

This has implications beyond just understanding rogue planets. It affects how we think about planetary system stability, how many planets get lost during formation, and what fraction of planetary-mass objects form through which mechanism.

It also raises interesting questions about the detectability of rogue planets in future direct imaging surveys. If massive, young planets can be spotted by infrared telescopes, how many more exist than microlensing suggests? Could they be far more abundant than current samples indicate?

Each discovery fills in the picture gradually. Science often works this way—not with dramatic revelations but with incremental progress toward understanding.

The Larger Implications for Exoplanet Science

This discovery matters beyond just rogue planets. It illustrates broader principles about how we detect and understand worlds we can't see directly.

For decades, we could only find exoplanets around other stars using indirect methods. We watched stars for the tiny wobble caused by orbiting planets. We observed the slight dimming when planets passed in front of their stars. Microlensing added another tool to the kit.

But here's what's interesting: each detection method finds different types of planets. The transit method, which watches for dips in starlight, is great at finding planets close to their stars. The radial velocity method, which measures stellar wobble, favors massive planets. Microlensing finds planets at large distances from their stars and planets around no star at all.

Together, these methods paint a more complete picture of planetary diversity than any single method could. The rogue planets detected through microlensing show us that planets aren't confined to orbits around stars. They're scattered throughout the galaxy in solitude.

This changes how we think about planets conceptually. They're not fundamentally "things that orbit stars." They're massive bodies formed through planetary processes, whether or not they eventually end up orbiting anything.

It also has philosophical implications about the prevalence of planetary-mass objects in the universe. If ejection is common, the galaxy might contain far more rogue planets than stars. The cosmos could be filled with wandering worlds, most of which we'll never detect.

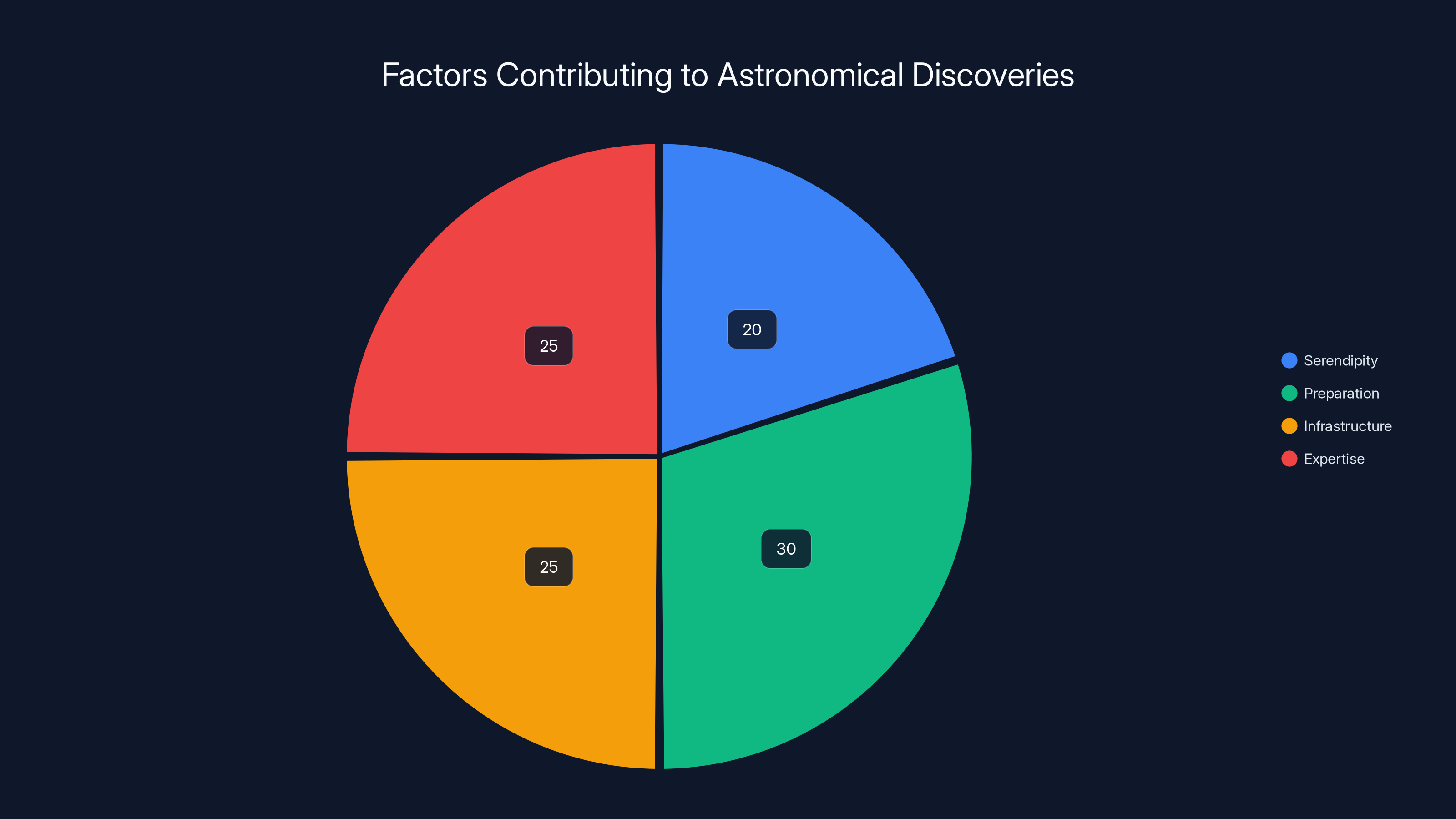

Estimated data shows that while serendipity plays a role, preparation, infrastructure, and expertise are equally critical in astronomical discoveries.

Comparing Detection Methods: What Each Tells Us

Let's put this in perspective by comparing how different detection methods work and what they reveal.

Transit Method: Stars brighten and dim slightly when planets pass in front of them. This requires nearly perfect alignment but gives us multiple transits to observe. We can measure planetary size, orbital period, and with follow-up observations, mass. We've found thousands of exoplanets this way. Bias: favors planets close to their stars.

Radial Velocity Method: Planets pull on their stars gravitationally, causing them to wobble slightly toward and away from us. We detect this as a Doppler shift in the star's light. This method favors massive planets orbiting close to their stars. Bias: we miss distant planets and low-mass planets.

Direct Imaging: We photograph planets directly in infrared light. Only works for young planets that still radiate heat from their formation. Very few planets detected this way, but we get structural information about their atmospheres. Bias: limited to young, massive planets.

Microlensing: We catch planets when they pass in front of background stars and magnify their light through gravitational lensing. This finds planets at large distances from their stars and planets that aren't orbiting stars at all. The sample is small but statistically interesting. Bias: we only see microlensing events when geometry aligns perfectly.

Each method finds different populations. Together, they give us a much richer understanding of planetary diversity than any single method could provide.

The Red Giant Lensing Star: A Key Piece of the Puzzle

The background star involved in this microlensing event turned out to be a red giant in the galactic bulge. This detail matters more than it might seem.

Red giants are evolved stars that have exhausted the hydrogen in their cores and expanded significantly. They're easier to characterize spectroscopically—their size, luminosity, and distance are more easily determined than for main-sequence stars.

Knowing the star's properties helped researchers pin down the system's distance and the planet's mass. If the background star had been a faint main-sequence dwarf, the calculation would have been harder or impossible.

This illustrates an important principle in observational astronomy: sometimes luck matters. Being in the right place at the right time with the right background star can mean the difference between a marginal detection and a confident one.

It also highlights why finding one planet in the Einstein desert, while significant, is just the beginning. Future discoveries will be found with various background star types, creating a more complete statistical picture.

Parallax and Distance Measurement: The Foundation of Certainty

Parallax—the apparent shift in position of nearby objects when viewed from different locations—is the foundation of cosmic distance measurements.

When you hold your finger at arm's length and look at it with one eye closed, then the other, your finger appears to jump. That's parallax. Astronomers use the same principle on cosmic scales. They measure stellar positions from opposite sides of Earth's orbit around the Sun. Nearby stars shift slightly compared to distant background stars. The amount of shift directly reveals the star's distance.

For microlensing events, parallax becomes crucial. By observing the same event from Earth and from Gaia's position at L2 (1.5 million kilometers away), researchers can measure the event's parallax. This directly reveals the distance to the lensing system.

This distance is fundamental. Everything else—the star's size, the planet's mass, the nature of the system—flows from knowing how far away it is. Without parallax measurement, microlensing gives you the Einstein ring size but not enough information to deduce the planet's mass with confidence.

Gaia's position at L2 makes it perfect for this. Its separation from Earth is large enough to create measurable parallax even for distant galactic bulge objects. Older space telescopes closer to Earth wouldn't have had sufficient baseline.

This technological advantage is why this particular discovery happened now. Earlier, the observation would have been possible but incomplete. Now, Gaia's unique vantage point delivers the data needed.

Estimated data shows a gap in rogue planet distribution around Saturn-mass, supporting the two-origins hypothesis. The lower-mass cluster consists of ejected planets, while the higher-mass cluster includes directly formed objects.

Statistical Models and the Art of Inference

When you can't measure something directly, you rely on statistical models and inference. The rogue planet mass determination involved sophisticated statistical techniques.

Researchers took the measured Einstein ring size, the measured parallax, the estimated star's properties, and fed them into Bayesian statistical models. These models incorporate prior knowledge about how planets typically form and their mass distributions. The models generate probability distributions for the unknown mass.

The result wasn't a single certain mass but a distribution of probabilities. The most likely value was about 0.2 Jupiter masses, but there was uncertainty around that estimate.

This reflects honest science. We can't measure the planet's mass directly. We infer it from multiple pieces of data and the assumptions built into our models. The inference is only as good as our assumptions.

When new methods or data become available—like Gaia's parallax measurements—they reduce uncertainty. The researchers' confidence in the mass estimate improved significantly once they had the distance measurement, because they could eliminate one major source of uncertainty.

This illustrates why finding rogue planets in the Einstein desert becomes statistically interesting. With enough examples, you can map out the actual distribution empirically, reducing reliance on models.

Implications for Understanding Planetary System Architecture

How do young planetary systems organize themselves? Do they form with planets in neat, circular orbits? Or do they start chaotically?

Theoretical models and observations suggest young systems are often turbulent places. Planets are born in swirling disks of gas and dust. They migrate inward and outward as they interact with the disk. They scatter off each other in dramatic encounters.

Some systems become stable quickly, settling into the orbital configurations we observe today. Others remain chaotic for hundreds of millions of years. In extreme cases, planetary encounters are violent enough to eject planets entirely.

The population of rogue planets offers a window into this process. Each rogue planet represents a failed retention event—a system that couldn't keep it. By counting rogue planets and understanding their properties, we constrain how often ejection happens and under what circumstances.

The Saturn-sized planet in the Einstein desert might result from an unusual ejection—perhaps a rare dynamical configuration that tossed out an object of unusual mass. Or it might represent something different entirely. More examples will help clarify what's common and what's rare.

This connects directly to questions about our own solar system. Did the early solar system have planets that were subsequently ejected? Evidence from certain simulations suggests yes—the "Nice model" and its variants propose that the outer solar system had more planets originally, some of which were ejected during planetary migration and scattering.

Those ejected planets might have become rogue planets themselves, forever lost to the solar system but adding to the galactic population of wandering worlds.

The Future of Rogue Planet Detection

Microlensing will continue to be important, but other techniques are emerging.

Infrared telescopes like JWST can spot very young, hot rogue planets—objects only a few million years old that still glow from their formation heat. This complements microlensing, which catches older, cold objects.

Astrometric surveys like Gaia can indirectly detect isolated planetary-mass objects through their gravitational effects on nearby stars or through direct motion measurements. As Gaia data improves, this method might yield additional detections.

Gravitational wave detection offers another possibility. When massive objects orbit each other, they emit gravitational waves. In principle, rogue planets might be detected this way if they're part of close binary systems with other rogue planets or compact objects. Current gravitational wave detectors aren't sensitive enough yet, but future upgrades might enable this.

Radio observations could find planets through radio emissions from planetary magnetospheres or atmospheric processes. Again, this would work better for more massive objects or younger ones with internal heat sources.

Each new technique adds to our understanding. By 2030, the rogue planet census might expand dramatically, providing the statistical sample size needed to definitively answer questions about planetary origins.

Connecting the Dots: Origins, Detection, and Physics

Let's step back and see how everything connects.

Planets form in protoplanetary disks around young stars. Most stay in their original systems in relatively stable orbits. Some get ejected through dynamical interactions, becoming rogue planets. A subset of rogue planets get detected through microlensing when they pass in front of background stars.

From those detections, we measure Einstein ring sizes. When we can measure parallax using space telescopes, we determine distances and thus planetary masses.

And when those masses cluster in certain patterns—with a notable gap in the middle—we realize we're looking at signatures of different formation pathways. The gap in the Einstein desert wasn't noise or statistical artifact. It reflects real physics: ejected planets cluster at lower masses, directly formed objects cluster at higher masses, and a gap separates them.

One Saturn-sized planet in the desert confirms what the pattern suggested. More detections will flesh out the picture. Eventually, we'll have enough data to write confidently about which rogue planets came from systems and which formed in isolation.

This knowledge ripples outward. It tells us about planetary system stability, about the prevalence of planets in the universe, about what factors dominate when planets form versus when they're ejected.

It's the kind of incremental progress that characterizes modern astronomy. No single observation reveals everything. But each observation, especially when it fills a gap in our understanding, advances the field forward.

The Human Element: Serendipity and Preparation

The discovery happened partly through luck. Gaia's orientation happened to be perfect for observing this particular event. But luck rewards the prepared mind.

The Korea Microlensing Telescope Network and OGLE have been systematically searching for microlensing events for decades. They've cataloged hundreds of events, developed expertise in analyzing them, and refined their techniques continuously. That infrastructure made it possible to immediately recognize something special when it happened.

Gaia's designers chose its orbit at L2 knowing it would enable parallax measurements impossible elsewhere. That choice, made years earlier, proved crucial when this particular event occurred.

Researchers had been debating the Einstein desert's reality for years, watching and waiting for just this kind of confirmation. When the data came in, they recognized its significance immediately.

So while serendipity played a role, the discovery was also the result of long-term preparation, sustained focus, and scientific infrastructure that accumulated value over years.

This is how modern astronomy works. Large surveys gather data consistently. Statistical patterns emerge. Discoveries fill gaps in those patterns. Knowledge advances through a combination of luck and systematic preparation.

Broader Context: Where This Fits in Exoplanet Science

We've discovered over 5,500 exoplanets orbiting distant stars. We've mapped their properties in detail—sizes, masses, orbital periods, atmospheric composition in some cases.

Yet rogue planets represent an unexplored frontier. They're not bound to any star, so traditional exoplanet surveys miss them entirely. They're harder to detect but easier to study once found (no glare from a host star). Their abundance and properties could fundamentally change how we think about planets.

The Einstein desert discovery suggests rogue planets aren't a random collection but a population with structure. That structure points to formation mechanisms. Understanding it deepens our grasp of how planets form, survive, and sometimes escape.

In the broader context of exoplanet science, this discovery marks progress toward a more complete census of planetary-mass objects in the universe. We're filling in the gaps in our knowledge, piece by piece.

FAQ

What exactly is a rogue planet?

A rogue planet is a planetary-mass object that does not orbit any star. These objects either formed through direct gravitational collapse in molecular clouds (creating substellar objects) or were ejected from planetary systems through gravitational interactions. They drift through interstellar space, never illuminated by a host star, making them extremely difficult to detect. Most rogue planets are cold and dark, visible only through indirect detection methods like microlensing.

How does microlensing detect rogue planets?

Microlensing works by detecting the gravitational bending of light from distant stars as a rogue planet passes in front of them from Earth's perspective. When a massive object (like a planet) passes between us and a background star, its gravity acts like a lens, magnifying and bending the star's light. This causes the background star to appear temporarily brighter, and astronomers measure the magnification pattern to infer the planet's properties. The technique is powerful because it can detect planets far from stars and planets with no host star at all.

What is the Einstein desert and why is it significant?

The Einstein desert is a gap in the mass distribution of rogue planets detected through microlensing, located between a cluster of smaller planetary-mass objects and a cluster of much larger objects. For years, scientists debated whether this gap was real or just an artifact of small sample sizes. The discovery of a Saturn-sized planet in the middle of the desert confirms the gap is real, suggesting that the two clusters represent planets from different origins: the smaller cluster consists of ejected planets from stellar systems, while the larger cluster represents directly formed substellar objects. This distinction has profound implications for understanding planetary formation and system dynamics.

What makes this Saturn-sized rogue planet special?

This planet is special because it's the first confirmed detection of a planetary-mass object in the Einstein desert, a region where astronomers expected few to no planets to exist based on formation theory. Finding it proves the gap is real and provides the first concrete evidence supporting the two-origins hypothesis for rogue planets. Its discovery required fortunate geometric alignment that allowed the Gaia space telescope to measure parallax, which was crucial for determining its actual distance and mass. It marks a turning point in rogue planet research, confirming long-debated theoretical predictions.

How did Gaia space telescope help measure this planet's mass?

Gaia, orbiting at the L2 Lagrange point about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, observed the same microlensing event from a dramatically different vantage point than Earth-based telescopes. This allowed astronomers to measure parallax—the apparent shift in the event's position—which directly reveals the system's distance. Without this distance measurement, the Einstein ring size alone cannot determine the planet's mass. The combination of ground-based and space-based observations provided the multiple data points needed for statistical inference of the planet's mass at approximately 0.2 Jupiter masses.

Are there other methods to detect rogue planets besides microlensing?

Yes, several methods complement microlensing. Infrared telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope can detect young rogue planets that still emit heat from their formation, but this works only for planets younger than a few hundred million years. Astrometric surveys measure the positions of stars over time to detect gravitational influences from nearby massive objects, potentially including rogue planets. Gravitational wave detection is theoretically possible but not yet practically viable for isolated rogue planets. Direct imaging in infrared remains limited to very young, massive objects. Each method finds different subsets of the rogue planet population.

What does this discovery tell us about planetary system formation?

The discovery supports the idea that planetary systems aren't always stable in their initial configurations. Planets can be ejected through gravitational interactions with other planets or through encounters with passing stars. The existence of rogue planets and the structure of their population (with the Einstein desert gap) suggests two distinct pathways: ejection from stellar systems produces smaller planets, while direct formation in molecular clouds produces more massive objects. This tells us that planetary systems are dynamic places where planets can be lost, and that not all planetary-mass objects form in circumstellar disks around young stars.

How common are rogue planets in the galaxy?

Estimating the true abundance of rogue planets is challenging because detection methods (particularly microlensing) are biased toward certain configurations. Studies suggest there might be significantly more rogue planets than stars in the galaxy, though estimates vary widely. If ejection is common during the early evolution of planetary systems, the number could be staggering. However, until we can directly count rogue planets using multiple detection methods, we remain uncertain. Accumulating more detections through microlensing and infrared surveys will help resolve this question.

Will this discovery lead to finding more rogue planets in the Einstein desert?

Almost certainly yes. The confirmation that planets exist in the Einstein desert means astronomers now know exactly where to look for additional objects. Ground-based microlensing surveys are continuously discovering new events. With thousands of potential microlensing events under observation, statistically some should produce planets in the desert. Within the next five to ten years, researchers expect to find dozens more, gradually filling out the population statistics and confirming the two-origins hypothesis more definitively. Each discovery strengthens the evidence.

Could rogue planets harbor life?

Unfortunately, rogue planets are unlikely to support life as we understand it. Without a star, they have no external heat source beyond residual warmth from their formation, which dissipates relatively quickly (within a few billion years for most objects). They would be extremely cold—far colder than Earth's surface. However, if a rogue planet had a geologically active interior and subsurface liquid water, life-supporting conditions might exist in extremely limited circumstances, similar to life around deep-sea hydrothermal vents on Earth. For most rogue planets, surface conditions would be utterly inhospitable to carbon-based life.

Key Takeaways

- A Saturn-sized rogue planet was discovered in the Einstein desert using microlensing in May 2024, filling a long-debated gap in the rogue planet mass distribution

- Fortunate alignment of Gaia space telescope observations enabled parallax measurement, allowing precise determination of the planet's actual distance and mass

- The discovery confirms the Einstein desert is real and suggests rogue planets have two distinct origins: ejection from star systems and direct formation through gravitational collapse

- Microlensing remains the only viable detection method for old, cold rogue planets, requiring rare geometric alignment when planets cross in front of background stars

- Statistical analysis of the bimodal rogue planet population could reveal how common planetary ejection is and what fraction of rogue planets form through each mechanism

Related Articles

- Smart Refrigerators with Barcode Scanners Transform Grocery Shopping [2025]

- CPU Price Wars: How Intel Flipped the Script on AMD's Dominance [2025]

- Grok Business & Enterprise: xAI's Bold Play for the AI Assistant Market [2025]

- Pebble Round 2 Smartwatch Review: Fixes and Features [2025]

- Launch Your Website This Weekend on a Budget [2025]

- Van Veen vs Anderson: PDC Darts Semifinal 2026 Guide & Viewing Options

![Saturn-Sized Rogue Planet Found in Einstein Desert [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/saturn-sized-rogue-planet-found-in-einstein-desert-2025/image-1-1767388049690.jpg)