NASA's Pandora Telescope: Finding Earth 2.0 [2025]

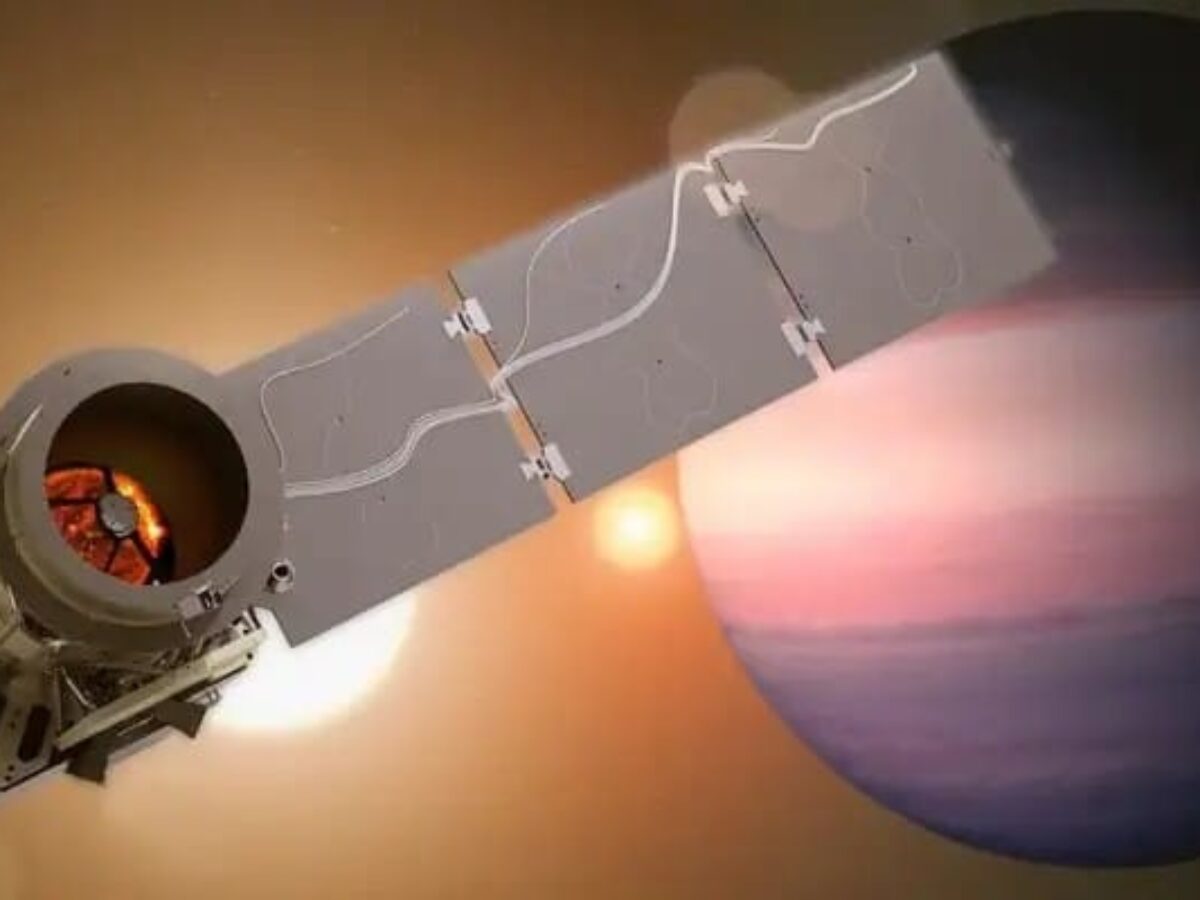

Last month, a small satellite launched into orbit that might sound unremarkable on the surface. It's not as famous as the James Webb Space Telescope. It cost about 1 percent of Webb's budget. Its mirror is roughly the size of a good amateur telescope, not a massive gold-coated collector spanning tens of meters.

But this satellite, called Pandora, solves a problem that's been quietly plaguing exoplanet science for nearly a decade.

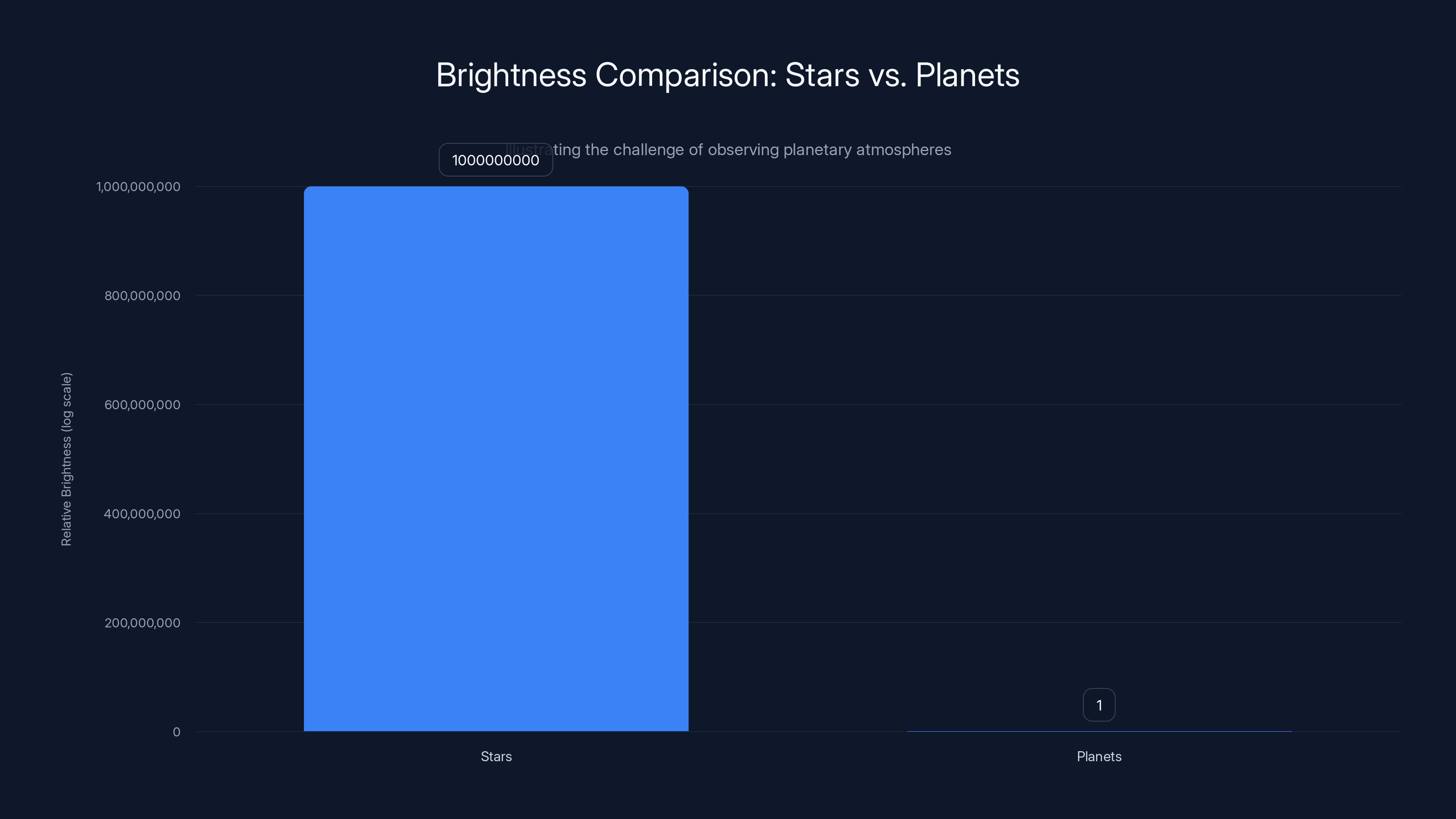

Here's the thing: when astronomers point the James Webb Space Telescope at distant planets to look for signs of life, they're trying to read a whisper while standing next to a jet engine. The starlight drowns out the planetary signal. Not completely. But enough to introduce uncertainty into some of humanity's most important questions about life elsewhere in the universe.

Pandora exists to eliminate that uncertainty. It's not flashy. It won't discover new worlds. But it will do something arguably more valuable: it will validate the discoveries we think we're making. And that might be the difference between getting headlines right and misleading the public about the biggest scientific question we've ever asked.

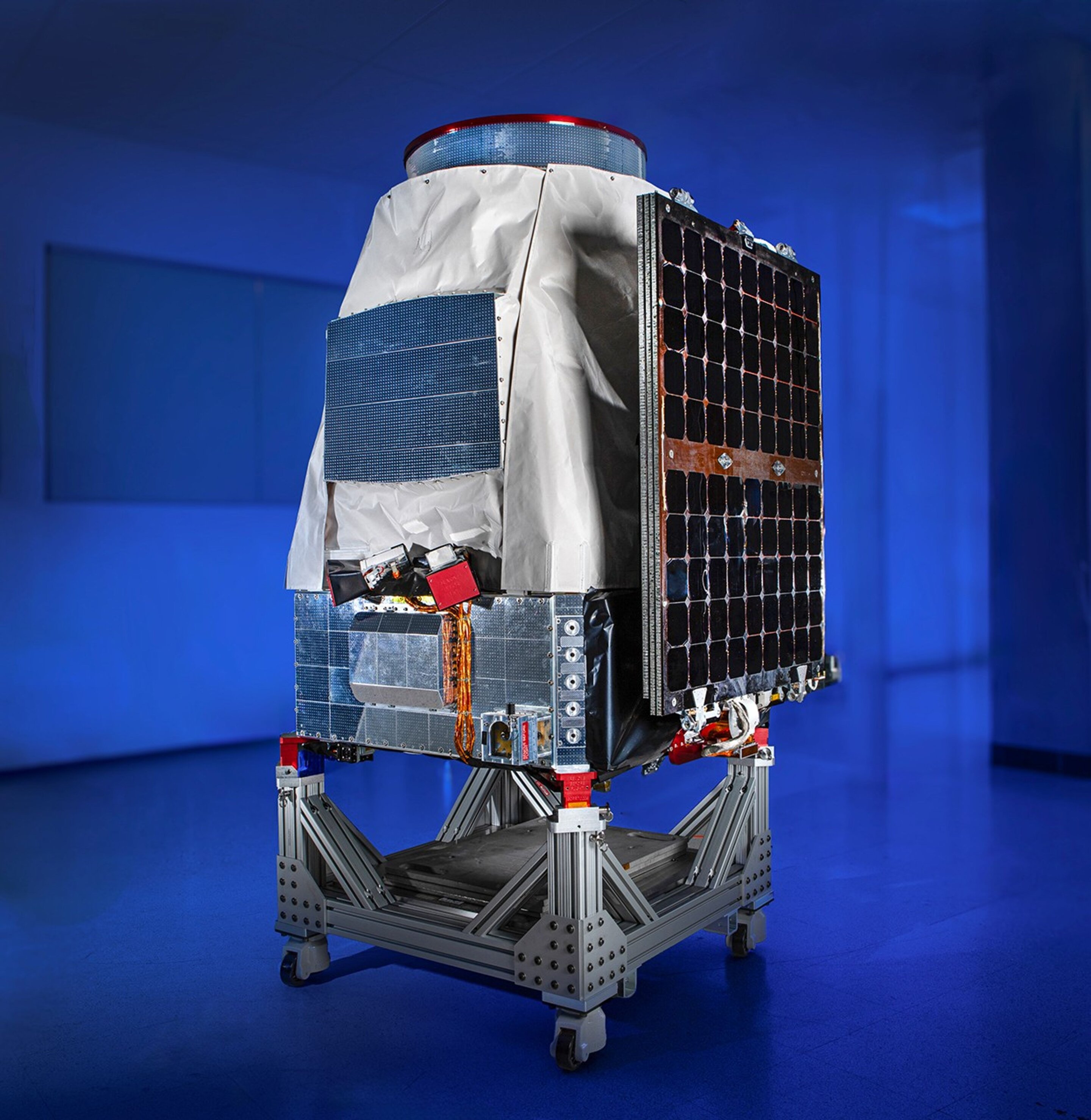

This is the story of how a satellite no bigger than a refrigerator could reshape how we search for habitable worlds.

TL; DR

- Stellar Noise Problem: Stars shine millions of times brighter than planets, and their own atmospheric signatures contaminate the spectral data scientists use to detect planetary atmospheres, creating false positives or false negatives in potentially habitable world detection.

- Pandora's Mission: Launched in January 2025, NASA's $20 million Pandora satellite will observe 20 preselected exoplanets simultaneously with their host stars to map stellar variability and correct for stellar contamination in Webb's data.

- Webb Bottleneck: The James Webb Space Telescope's schedule is completely booked for years, making a dedicated atmospheric characterization mission essential for systematic exoplanet observation.

- Real Impact: Pandora will collect 24 hours of observations per target across 10 visits, capturing both short-term stellar flares and long-term cycles to build accurate models of stellar behavior.

- Bottom Line: Pandora won't find new exoplanets, but it could be the single most important mission for confirming whether any of the exoplanets we've already found might actually harbor life.

Pandora's development cost is a mere 1.5% of Webb's, highlighting its focused mission and use of proven technology. Estimated data based on provided percentage.

The Webb Revolution and Its Unexpected Problem

When the James Webb Space Telescope launched on December 25, 2021, it represented 30 years of engineering ambition and roughly $10 billion in investment. The gold-coated mirror, the infrared sensors, the sunshield kept at minus 233 Celsius—every component was designed to see farther and clearer than any observatory humanity had ever built.

Within months of deployment, Webb started delivering results that lived up to the hype. Images of the earliest galaxies, nebulae in unprecedented detail, atmospheric analysis of distant exoplanets. The telescope was doing exactly what it was built to do: answering fundamental questions about the universe.

But as researchers dug deeper into the exoplanet data, something uncomfortable emerged. The signal they were detecting from planetary atmospheres wasn't as clean as expected. Specifically, when astronomers used Webb to observe light filtering through a planet's atmosphere as it passed in front of its star, they couldn't always tell if the chemical signatures they were seeing belonged to the planet or the star itself.

This wasn't a failure of Webb. The telescope was working perfectly. The problem was more subtle and more fundamental.

Consider the basic physics. A star produces its own light. That light passes through the star's atmosphere (its chromosphere and corona), picking up the spectral fingerprints of the molecules in that stellar atmosphere. Water vapor, carbon monoxide, methane—the same molecules scientists are desperately hunting for in planetary atmospheres. The light then travels across space and passes through the planet's atmosphere, where it gets filtered again.

By the time that light reaches Webb's mirror, the telescope can see both sets of fingerprints. But separating them is like trying to identify someone's face in a photograph where their face is overlaid with another person's face. The features don't belong to a single person anymore. They're a composite.

Daniel Apai, a member of Pandora's science team from the University of Arizona, uses an elegant analogy to explain this: imagine holding a glass of wine in front of a candle. You can see something through the wine, but you're looking at both the wine and the candlelight simultaneously. The candlelight—in this case, the star—dominates the view.

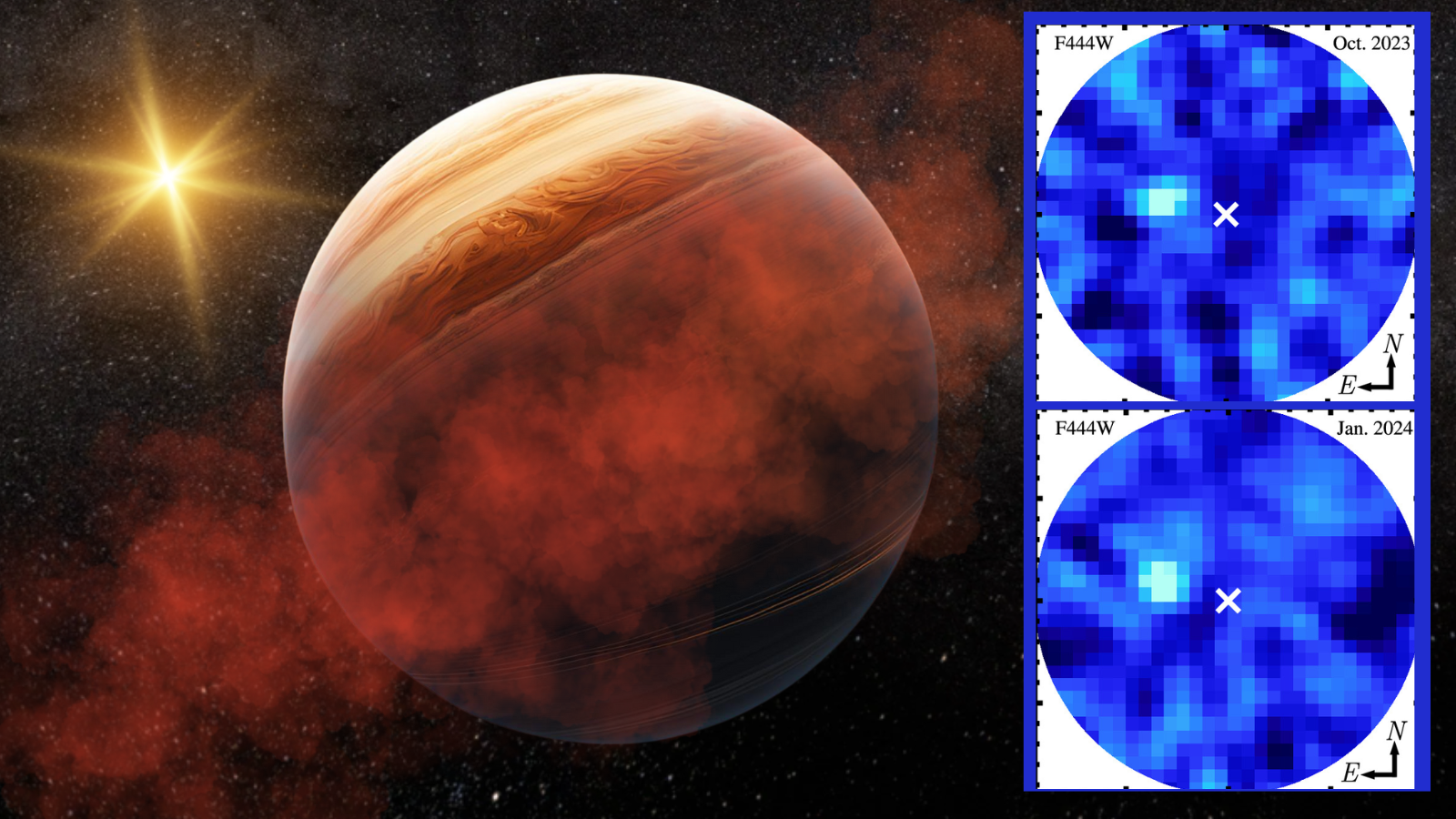

When Apai and his colleagues started publishing their exoplanet findings using Webb data, the community was optimistic. Potentially habitable worlds with water in their atmospheres. Worlds where the spectral signatures aligned with what researchers expected from Earth-like planets. Papers hit preprint servers. Excitement built.

Then reality set in.

Stars are 1 million to 1 billion times brighter than planets, complicating the observation of planetary atmospheres. Estimated data.

The Stellar Contamination Crisis of 2017-2018

Astronomers had theorized for years that stellar variability could contaminate exoplanet observations. But theory and evidence are different things. The problem didn't become concretely obvious until researchers began publishing detailed spectroscopic analyses of exoplanets observed by the most powerful telescopes available.

The realization crystallized around 2017 and 2018, roughly three years before Webb launched. Scientists were using existing telescopes to study distant planetary atmospheres, and they noticed something troubling: the same planet observed on different nights, or even the same night, produced slightly different spectral signatures.

This variation could indicate real changes in the planet's atmosphere. But often, it indicated changes in the star. A stellar flare here. A sunspot rotating into or out of view there. The star's general variability over days, weeks, or months.

Tom Barclay, deputy project scientist on Pandora, described the impact plainly: "One of the ways that this manifests is by making you think that you're seeing absorption features like water and potentially methane when there may not be any, or, conversely, you're not seeing the signatures that are there because they're masked by the stellar signal."

In other words, stellar contamination could create two types of errors:

-

False Positives: A water signature that looks like it's coming from the planet actually comes from the star. Scientists announce a potential biosignature that doesn't exist.

-

False Negatives: A planet actually has water in its atmosphere, but the star's own spectral features mask it. Scientists miss evidence of habitability that's genuinely there.

Both errors are scientifically catastrophic. The first embarrasses the field and misleads the public. The second means missing potentially habitable worlds hiding in plain sight.

Elisa Quintana, Pandora's lead scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, explained the urgency: "When we're trying to find water in the atmospheres of these small Earth-like planets, we want to be really sure it's not coming from the star before we go tell the press and make a big stink about it. So we designed the Pandora mission specifically to solve this problem."

That design process began in 2020. NASA selected Pandora for development in 2021, just months before Webb's launch. The mission was framed as complementary to Webb—not competing with it, but solving problems that Webb couldn't or shouldn't solve given its limited observation time.

The James Webb Bottleneck

There's a practical constraint that makes Pandora essential: Webb's schedule is completely full.

The James Webb Space Telescope receives roughly 20,000 proposals every year from astronomers around the world. Scientists submit detailed plans for what they want to observe, how much telescope time they need, and why their research matters. A peer review committee evaluates every proposal, selects about 5 percent, and creates the observatory's annual schedule.

Webb operates under severe time pressure. Even though it's designed to function for 10 to 20 years, every hour of observation time is a scarce resource. Once an hour is allocated to one project, it's unavailable for competing priorities. Oversubscription ratios exceed 4:1, meaning four times more observations are requested than available time.

For exoplanet characterization specifically, astronomers need long observation windows. A typical atmospheric study requires 24 hours of telescope time per target to ensure sufficient signal and to capture variability. If a researcher wants to study 20 planets in depth, that's 480 hours of Webb time. At current oversubscription rates, that's essentially impossible for any single project.

Webb's extraordinary sensitivity makes it suited for difficult targets: planets far away, systems with faint stars, planets that are genuinely hard to observe. But systematic characterization of a sample of exoplanets? That's a job for a dedicated instrument with a specific mission design and a schedule that isn't perpetually overbooked.

Pandora fills that niche perfectly. It's not trying to win a competition for Webb's time. It's operating independently, using modest capabilities to accomplish a specific goal that complements Webb's observations.

Only 5% of proposals submitted to the James Webb Space Telescope are accepted due to high demand and limited observation time. Estimated data based on typical acceptance rates.

How Pandora Actually Works

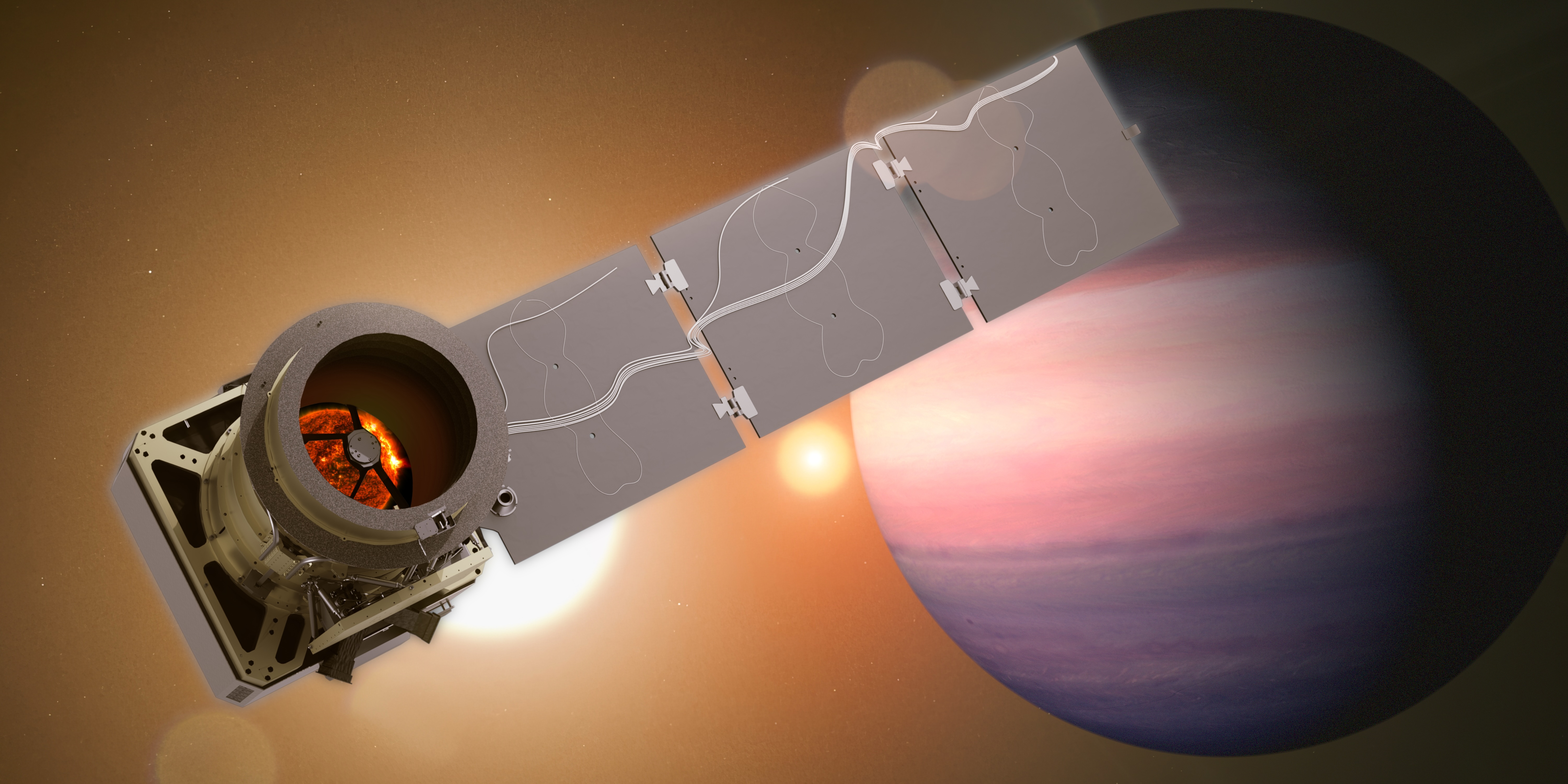

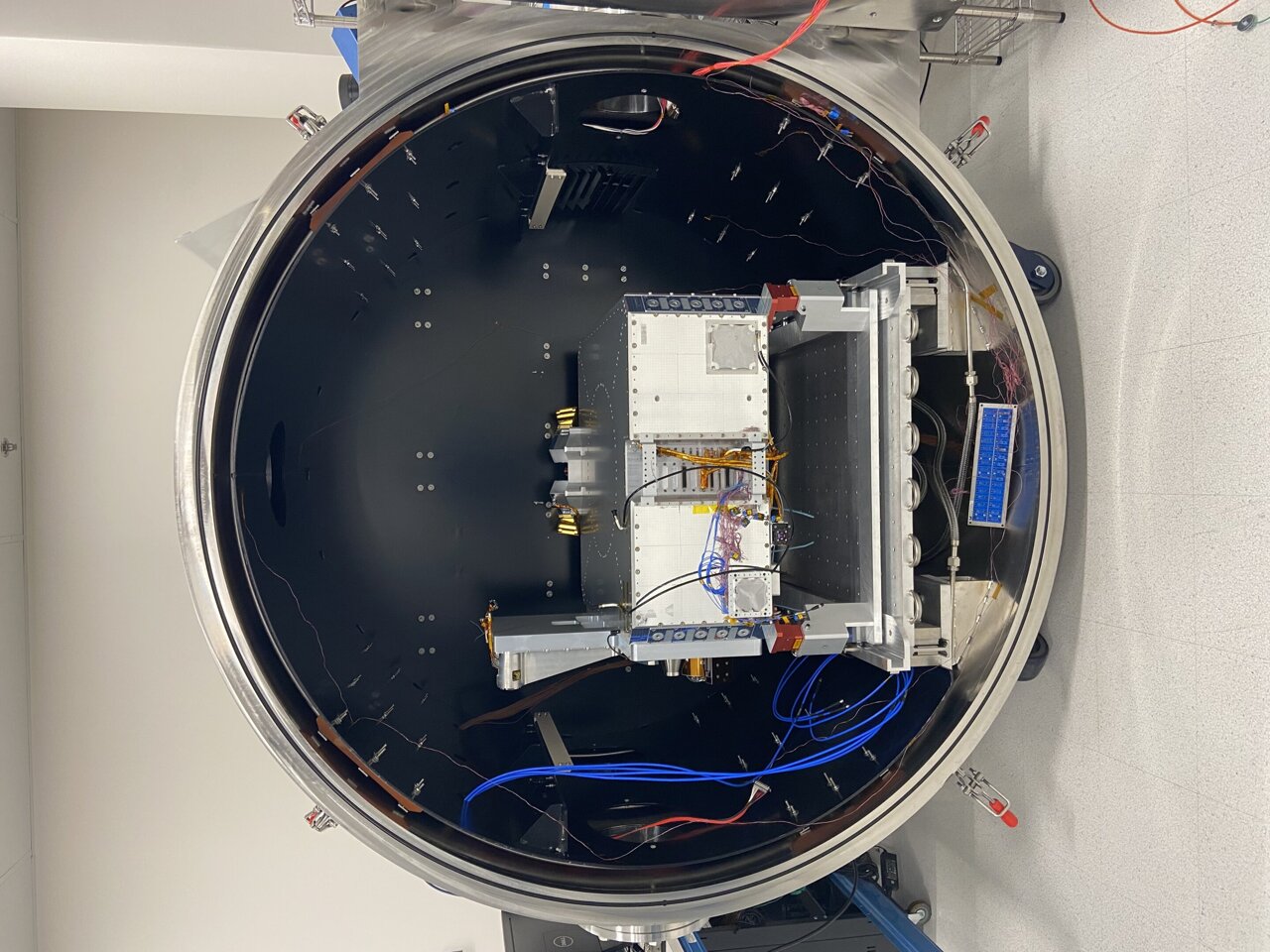

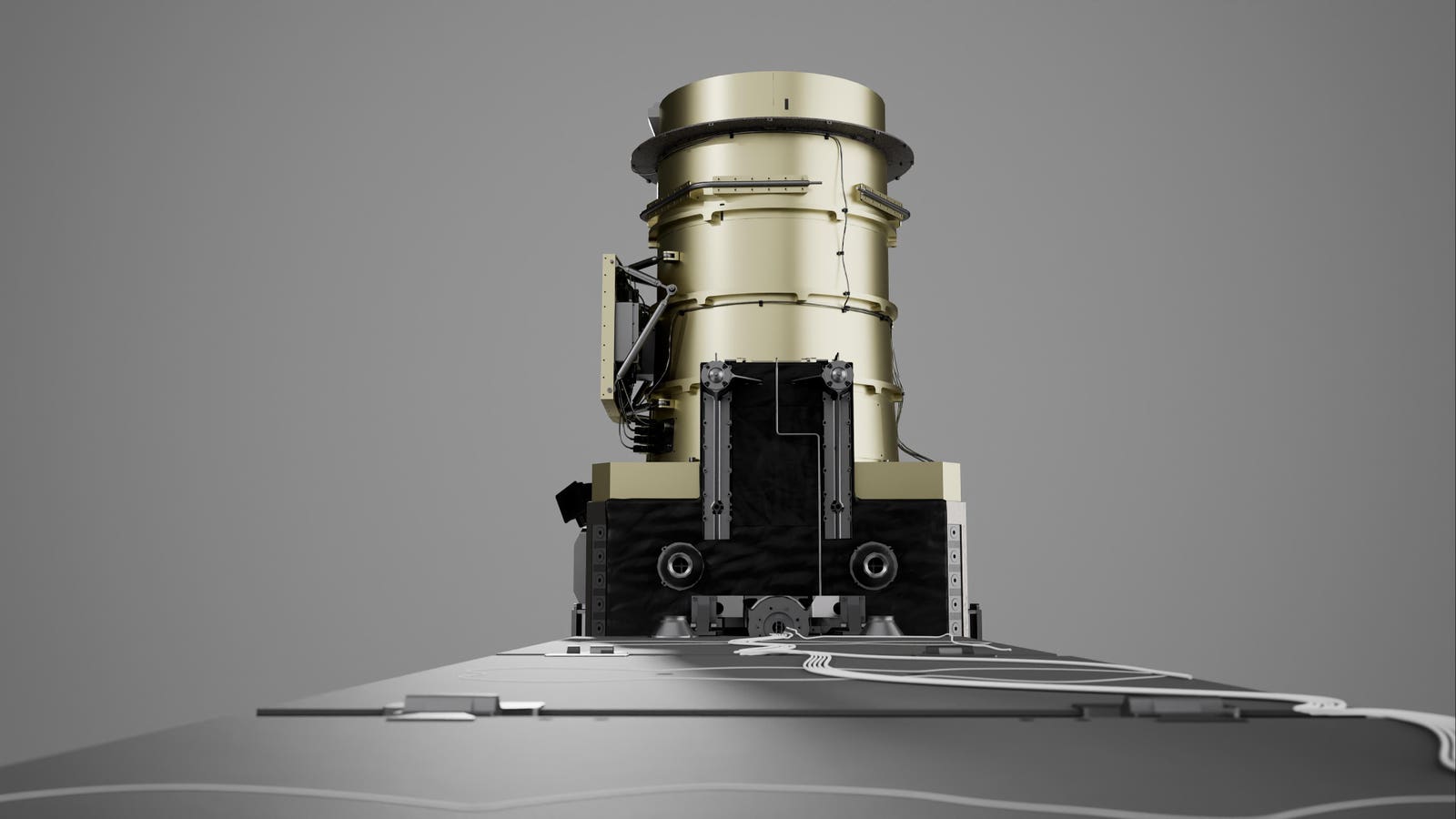

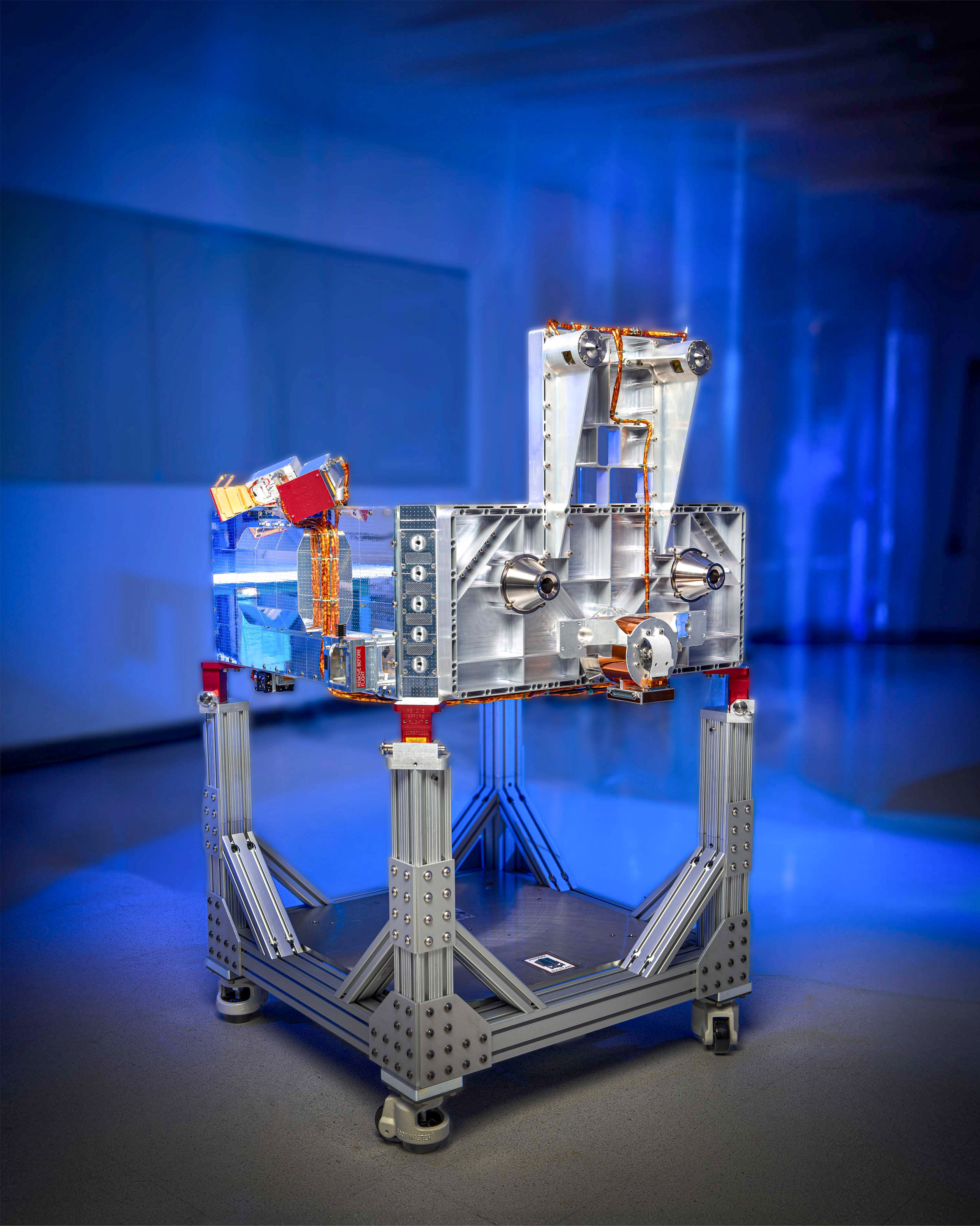

Pandora launched on January 12, 2025, aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. It deployed in a polar sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of roughly 380 miles (613 kilometers), one of the favored orbital zones for Earth observation satellites and space telescopes.

The satellite itself is modest by space standards. Its primary mirror is less than one-tenth the diameter of Webb's. If Webb is a cathedral, Pandora is a small chapel. But that's intentional. The mission doesn't need a massive mirror. It needs precision, stability, and most importantly, the ability to stare at a single target for extended periods.

Pandora carries two main instruments: a visible light camera and an infrared detector. Both are optimized for the same task: measuring the light from stars and planets across different wavelengths simultaneously.

The observation strategy is straightforward but powerful. Pandora points at a selected exoplanet and its host star, then observes both simultaneously for 24 consecutive hours. This isn't incidental observation. The satellite is designed to watch the star specifically, cataloging every change in brightness, every flare, every shift in its spectral output.

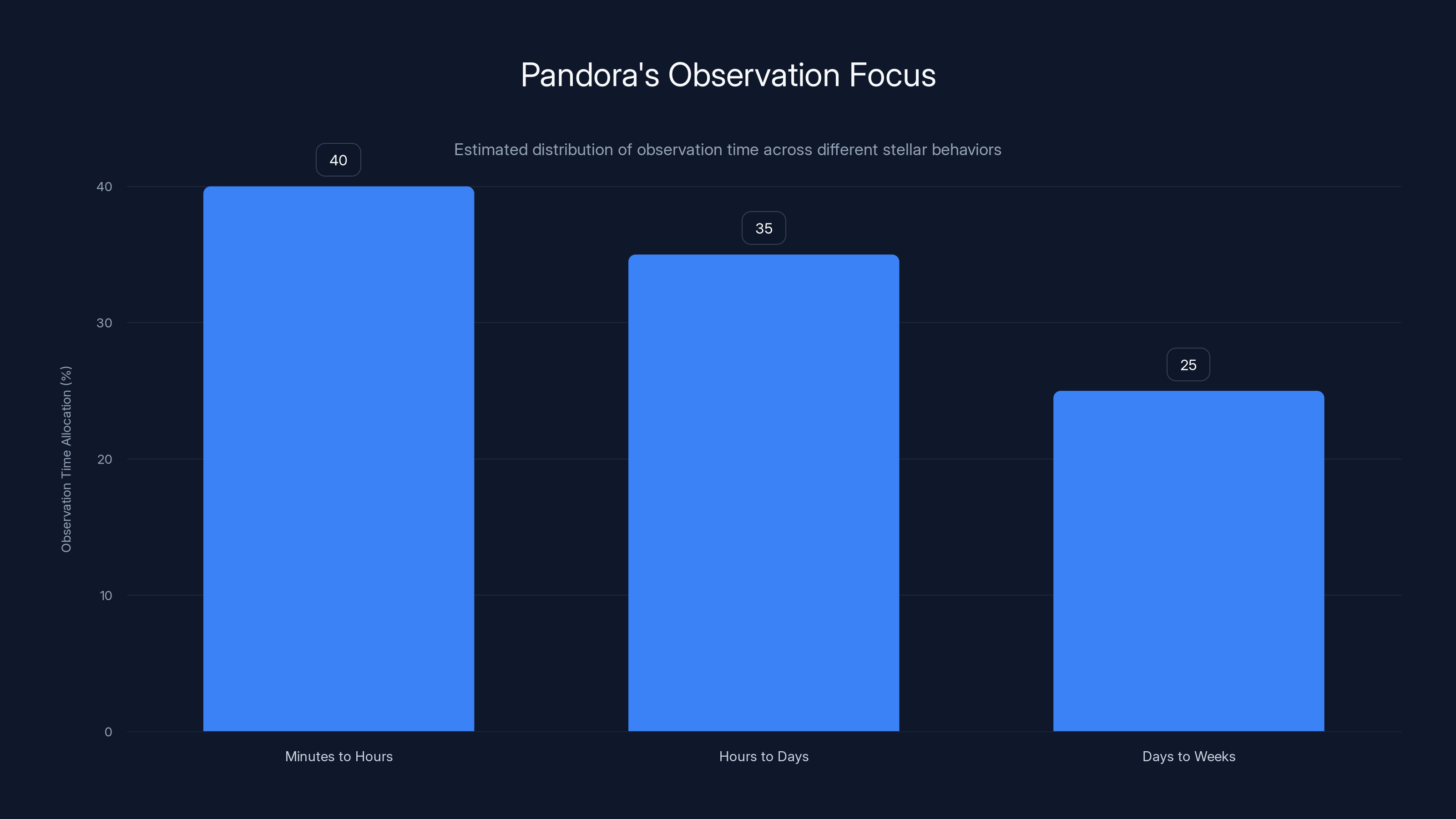

That 24-hour window captures different timescales of stellar behavior:

-

Minutes to Hours: Stellar flares and rapid outbursts. Flares are sudden releases of energy that can mimic or obscure planetary atmospheric signals.

-

Hours to Days: Sunspot rotation. Like Earth's sun, distant stars have dark, cooler regions. As the star rotates, these spots come into view and rotate away, changing the star's overall brightness and spectrum.

-

Days to Weeks: The star's fundamental rotation period. Some stars spin faster than others, and the period matters for understanding the star's magnetic activity.

Pandora will observe each of its 20 target exoplanets 10 times during its one-year prime mission. That's 200 observation epochs, each providing a window into stellar behavior at different seasons of the star's activity cycle.

Over time, this data builds a comprehensive model of what the star is doing across all timescales. When astronomers later look at Webb's observations of the same planet, they can subtract the stellar contribution, leaving just the planetary signal.

The orbital choice itself is strategic. Pandora operates in a sun-synchronous orbit, which means it crosses the Earth-Sun line at the same local time every day. The satellite's solar panels stay illuminated by sunlight continuously, and its thermal environment remains stable. For an instrument that needs consistent, long observation sessions, this orbit is ideal.

Over the next several months of 2025, Pandora is undergoing commissioning. Ground controllers are testing every system, calibrating the instruments, and verifying that the satellite performs as designed. The scientific observations will begin in spring 2025, after the commission phase concludes.

The 20 Target Planets: A Carefully Curated Sample

Pandora's target list isn't arbitrary. The 20 exoplanets selected for intensive study represent a specific scientific focus: small, potentially habitable worlds around relatively nearby stars.

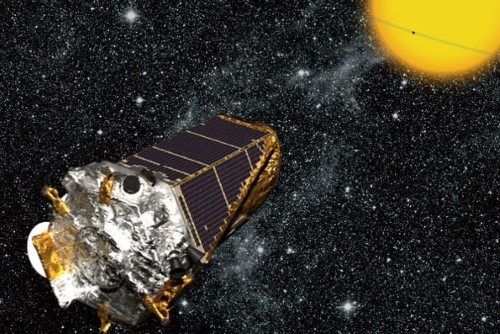

These aren't newly discovered planets. Most were detected years ago, often by the NASA Kepler Space Telescope or ground-based surveys. Some have been observed by other instruments, accumulating preliminary data about their sizes, masses, and orbital characteristics.

What they have in common is promise. These are worlds that warrant deeper investigation. Some might be rocky like Earth. Others are on the boundary between Earth and mini-Neptune, planets that are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. Understanding the atmospheric composition of these worlds is crucial for evaluating whether they might harbor life.

Here are the key characteristics:

-

Orbital Period: Most are on relatively short orbital periods, ranging from several days to weeks. This means they pass in front of their stars frequently, providing multiple observation opportunities.

-

Star Brightness: The target stars are bright enough for detailed spectroscopic observation, but dim enough that stellar contamination is a genuine problem. This is the sweet spot where Pandora's observations matter most.

-

Distance: Most are within roughly 50 to 100 light-years of Earth. At these distances, they're observable with space-based telescopes but distant enough to be genuinely challenging.

-

Known Characteristics: Many have been observed by other missions, providing context for Pandora's observations. This allows correlation between datasets.

The selection process involved consultation with the broader exoplanet community. Scientists submitted proposals for which worlds would benefit most from Pandora's observations. NASA evaluated which targets would yield the highest scientific return. The result is a curated sample designed to address the most pressing questions about habitable worlds.

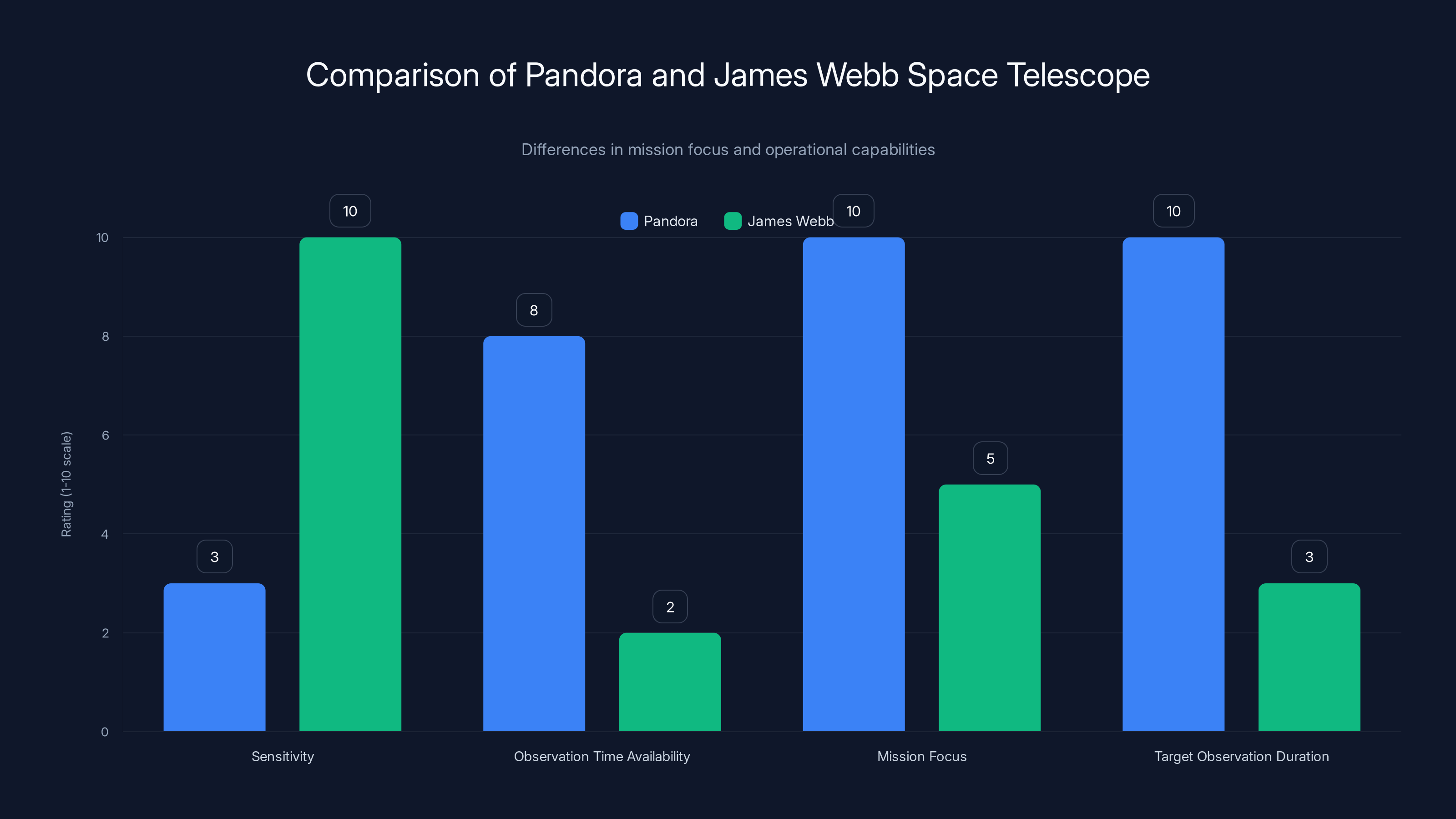

Pandora excels in observation time availability and target observation duration, while James Webb leads in sensitivity. Estimated data.

The Stellar Spots Problem in Detail

Let's dive deeper into why stellar spots are such a problem, because understanding this is central to understanding why Pandora exists.

Our own sun has sunspots. These are regions where the magnetic field is temporarily stronger, suppressing convection and causing those areas to be cooler and darker than surrounding regions. Sunspots appear and disappear over weeks or months. Groups of spots emerge, persist for a time, then fade away. The sun's overall output of light fluctuates measurably as spots rotate into and out of view.

Distant stars are the same, but with variations. Some stars are far more active than our sun, with larger spots and more frequent changes. Some stars are less active. The rotation periods vary from hours (for some rapidly spinning young stars) to months (for slow rotators) to years (for extremely slow rotators).

When a planet transits a star—passes in front of it—and a starspot happens to be in the transit path, the planetary atmosphere's spectral signature gets blended with the spot's darker, cooler region. The result is a distorted measurement of planetary atmospheric composition.

Consider a concrete example. Imagine observing an exoplanet around a star with a large, persistent starspot. When the planet transits across the star's face but avoids the spot, you get a clean spectral measurement of the planetary atmosphere. When the planet transits across the spot, the measurements change. Is the change real, reflecting actual planetary atmospheric conditions, or is it an artifact of the spot?

Without independent data about where the star's spots are and how they're changing, you can't tell.

Pandora solves this by watching the star continuously, mapping spot locations, tracking their evolution, and measuring how much the star's brightness changes on different timescales. This creates a reference map of stellar behavior that astronomers can compare against their planetary observations.

Pandora's Complementary Role to Webb

The relationship between Pandora and Webb isn't competitive. It's complementary, like having both a scalpel and a surgical microscope. Each tool excels at different tasks.

Webb's strength is raw sensitivity and spatial resolution. Its massive mirror collects enormous amounts of light, allowing observations of extremely faint or distant objects. It's the tool you use when you have one chance to observe something crucial and need the absolute best data possible.

Webb's weakness is availability. The telescope is overbooked. Every hour of observation time is fought over by thousands of researchers. Adding a project to Webb's schedule means removing another project.

Pandora's strength is systematic, long-duration observation of selected targets. It can stare at a single star for 24 hours without competing for telescope time. It can revisit the same targets repeatedly. It's optimized for one specific task: characterizing stellar variability to improve planetary atmospheric measurements.

Pandora's weakness is that it's not as sensitive as Webb. Its mirror is smaller, its instruments less sophisticated. It can't push the boundaries of detectability the way Webb can.

The ideal workflow looks like this:

-

Scientists submit a proposal to observe exoplanet atmospheres with Webb.

-

Before or after the Webb observation, they check the Pandora archive. Has Pandora observed this star? If yes, they have a detailed model of stellar variability.

-

They analyze the Webb data, correcting for stellar contamination using the Pandora reference model.

-

The resulting planetary atmospheric measurements are far more reliable than they would be without the stellar correction.

This division of labor maximizes the scientific return from both missions. Webb focuses on its unique capabilities: extreme sensitivity and detailed observation of challenging targets. Pandora handles the systematic characterization needed to validate Webb's results.

Over time, the Pandora archive becomes increasingly valuable. As the mission accumulates observations of its 20 targets, scientists build ever-more-complete pictures of stellar behavior. A star observed 10 times across a year provides better statistics than a star observed once. Patterns emerge. Predictions become more accurate.

Pandora dedicates most of its observation time to capturing rapid stellar flares and outbursts, with a balanced focus on sunspot rotation and fundamental star rotation. Estimated data.

The $20 Million Question: Why Is Pandora So Cheap?

Pandora's budget of $20 million is roughly 1.5 percent of Webb's total development cost. How is that possible for a space telescope?

The answer lies in focused mission design and pragmatic engineering choices.

First, Pandora doesn't try to be all things. It's not trying to discover new exoplanets. It's not trying to image nebulae or study distant galaxies. It has one job: measure stellar variability. That focused purpose allows simplified instrument design and streamlined development.

Second, Pandora uses proven components and established technology. The instruments are based on designs that have flown before. The spacecraft bus uses standard components. The mission doesn't require major technological breakthroughs. It's engineering, not research.

Third, Pandora benefits from lessons learned by previous missions. Engineers and scientists know how to build space telescopes now. Webb had to invent solutions to problems that had never been solved before, driving up costs massively. Pandora builds on that knowledge.

Fourth, the mission is genuinely small. A refrigerator-sized satellite launches alongside other payloads on a shared rocket. Launch costs are minimal compared to a dedicated launch. The ground station infrastructure already exists. No special handling required.

Fifth, and perhaps most importantly, Pandora doesn't require extraordinary precision or sensitivity. It needs stability and consistent performance, not breakthrough technology. That's vastly cheaper to develop and more reliable in operation.

The comparison to Webb is instructive. Webb pushed every boundary: new types of detectors, novel deployment mechanisms, precision engineering at unprecedented scales. Every system was cutting-edge, and many represented the first time anyone had tried to operate in space that way. Costs exploded correspondingly.

Pandora is the opposite. It's a straightforward space telescope doing a specific job well. That design philosophy costs less and often delivers more reliable results.

What Pandora Will Teach Us About Stellar Behavior

Beyond its immediate role in correcting exoplanet observations, Pandora's data will transform understanding of stellar physics.

Stars are more complex than the simple balls of plasma they appear to be from Earth. They have magnetic fields that generate activity cycles. They have surface features—spots, flares, active regions—that evolve on various timescales. The relationship between a star's mass, age, rotation rate, and activity level remains incompletely understood.

Pandora's 20 targets represent a range of stellar types, masses, and ages. Some are young and highly active. Others are older and quieter. Some are close to Earth's sun in character. Others are fundamentally different—smaller red dwarfs, for instance, which are far more numerous than stars like our sun but less well understood.

Twenty targets might sound small for a statistical sample, but the depth of observation compensates. Ten observation epochs per target, each lasting 24 hours, provides extraordinary temporal resolution. Over a year, Pandora will accumulate roughly 200 days of observation time distributed across 20 stars. That's approximately 10 days per star, collected over 12 months.

This temporal distribution is crucial. It captures stellar variability on all relevant timescales. The mission doesn't just measure average behavior; it measures how behavior changes.

The resulting dataset will be mined by stellar physicists for years. Questions that seemed unanswerable before become tractable. Why do some stars have strong activity cycles while others show no clear periodicity? How do stellar flares correlate with rotation rate and magnetic field strength? What's the relationship between a star's age and its activity level?

Pandora provides empirical answers to these questions. That knowledge feeds back into exoplanet science, improving our ability to model and understand the environments where potentially habitable worlds orbit.

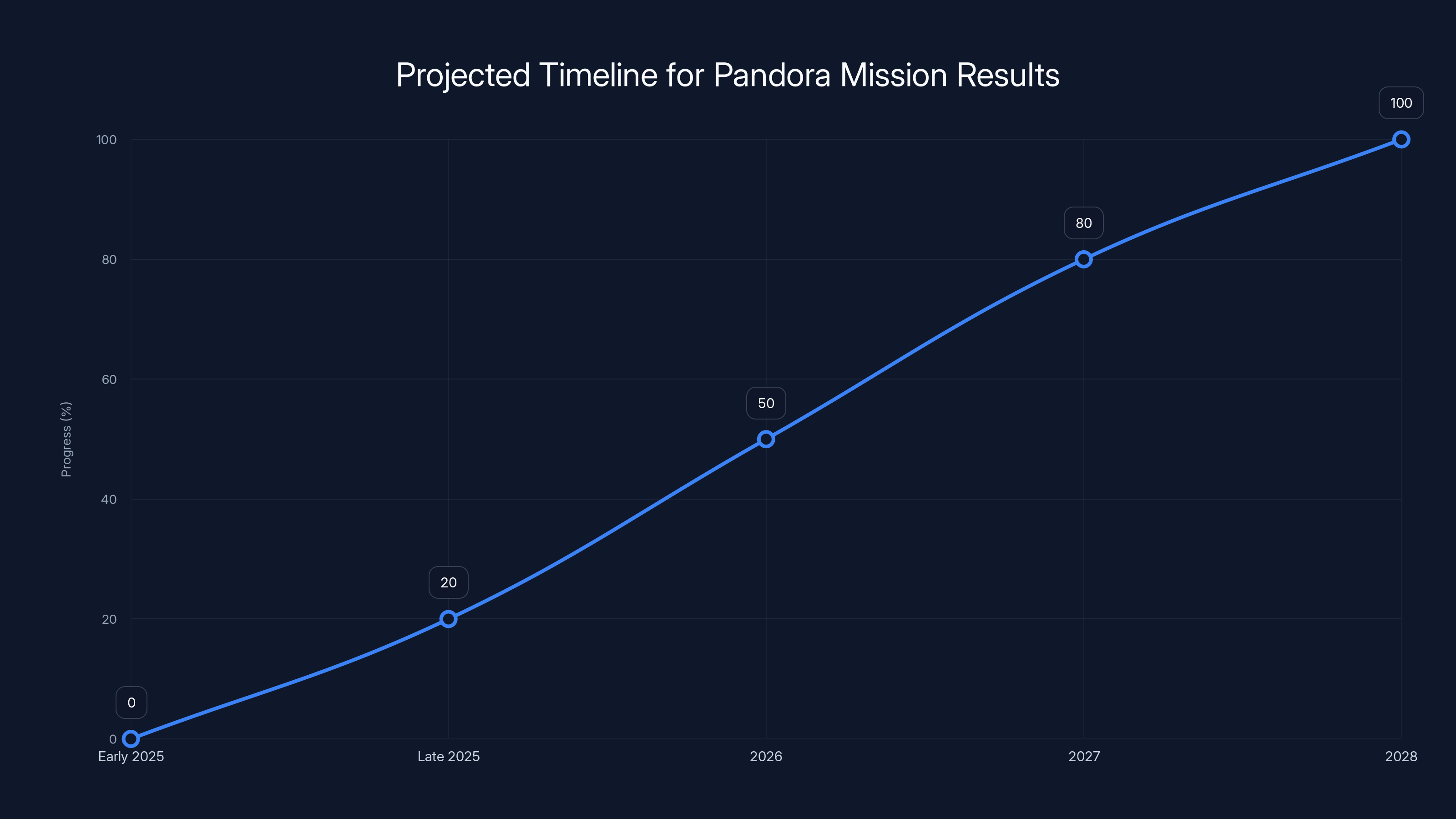

Estimated data shows that significant scientific results from Pandora and Webb observations are expected to emerge between 2026 and 2028, with 2027-2028 being potential breakthrough years for exoplanet science.

Finding Earth 2.0: What Counts as Habitable?

All of this infrastructure—Webb, Pandora, ground-based telescopes, future missions—exists because of one question: Are there other Earth-like worlds out there?

The answer is almost certainly yes. Statistical models suggest that most stars have planets, and many have multiple planets. In the Milky Way alone, there are probably 10 billion to 100 billion planets. Some fraction of those are rocky worlds in their star's habitable zone, the region where liquid water could exist on a planet's surface.

But knowing that Earth-like worlds probably exist somewhere is different from identifying them and understanding their properties. The latter requires detailed observations and analysis.

The current definition of habitability, used by Pandora's team and the broader research community, is specific but not iron-clad. A habitable world is a rocky planet in the habitable zone of its star, with atmospheric evidence suggesting liquid water on the surface and absence of clear biosignatures that rule out life.

Wait, that last part needs clarification. Researchers look for biosignatures—chemical signatures that suggest life is present or was present. The classic example is oxygen combined with methane. Earth's atmosphere contains both. Oxygen is produced by photosynthetic life. Methane is produced by living organisms and destroyed by oxygen. Finding both together in an exoplanet atmosphere would be remarkable, suggesting life might be present.

But no confirmed biosignatures have been detected in exoplanet atmospheres yet. The field is still at the stage of detecting atmospheric composition—water, carbon dioxide, methane, other molecules—without definitively proving life is present.

Pandora's contribution to this endeavor is subtle but essential. By eliminating uncertainty from stellar contamination, it ensures that when atmospheric signatures are detected, scientists can confidently say they came from the planet, not the star. That confidence is necessary before making extraordinary claims.

The Timeline: When Will We See Results?

Pandora's one-year prime mission runs through January 2026. During that year, the satellite will collect its observations, transmit data to Earth, and undergo analysis.

But the real scientific payoff comes after the mission's nominal operations end. The data then becomes part of the public archive, available to researchers worldwide. Papers start appearing, analyzing Pandora's observations in combination with other datasets.

Webb observations of Pandora's target planets will continue independently, on whatever schedule Webb's overseers allocate. Some planets might be observed in 2025, others in 2026 or beyond. The combination of Webb and Pandora data, applied to the same targets, will generate the most scientifically significant results.

So the realistic timeline looks like this:

-

Early 2025: Pandora begins science operations after commissioning.

-

Late 2025: Initial results from Pandora observations emerge. Stellar activity patterns for the first few targets become apparent.

-

2026: Pandora's prime mission concludes. Simultaneously, first combined Webb-Pandora analyses of specific target planets appear.

-

2027 Onward: The full Pandora archive becomes richly exploited. Statistical analyses emerge. Stellar models improve. Exoplanet atmospheric characterization improves dramatically.

If Pandora is successful, and if Webb continues operating, 2027-2028 could be breakthrough years for exoplanet science. That's when we'll have reliable atmospheric measurements for the first systematic sample of potentially habitable worlds.

Will those measurements reveal life? Almost certainly not directly. Biosignatures require a combination of spectral features that are extraordinarily difficult to detect. But the measurements will establish baselines. They'll show which worlds truly look like they might be candidates for habitability and which don't. That's progress.

Why Pandora Matters: The Bigger Picture

Pandora is a small mission by space standards. Its budget is modest. Its objectives are narrowly focused. It won't make headlines the way Webb does.

But small missions often have outsized impact. They solve specific problems that enable bigger breakthroughs.

Consider the history of space exploration. The Hubble Space Telescope seemed marginal until its mirror was fixed. Then it revolutionized astronomy. The Kepler Space Telescope discovered thousands of exoplanets, transforming the field. Neither mission required the biggest budget or the most complex engineering. Both did exactly what they were designed to do, exceptionally well.

Pandora fits that pattern. It's not trying to be revolutionary. It's trying to be reliable, systematic, and focused. If it succeeds, it enables a generation of exoplanet science that's far more confident and rigorous than is currently possible.

Think about the implications. Right now, when a researcher announces the discovery of water in an exoplanet's atmosphere, there's an asterisk. The announcement is qualified with statements about stellar contamination and measurement uncertainty. The media nonetheless runs headlines about "potentially habitable" worlds, generating public interest but also causing confusion about what the data actually shows.

With Pandora's stellar characterization data, those qualifications diminish. The measurements become more reliable. Scientists can speak with greater confidence. The public gets a clearer picture of what we actually know versus what we're still investigating.

On a longer timescale, Pandora contributes to a grand mission: cataloging potentially habitable worlds in our galactic neighborhood. Thousands of exoplanets have been detected. Hundreds are in habitable zones. But most haven't been characterized atmospherically. That requires years of systematic observation.

Pandora is a piece of that larger puzzle. It's not the most glamorous piece. But it might be essential.

Beyond Pandora: The Future of Exoplanet Science

Pandora is an interim step, solving a critical problem with current tools and telescopes. But space astronomy is constantly evolving. Future missions are already in development.

NASA is designing the Habitable Worlds Observatory, a next-generation space telescope that would be larger and more sensitive than Webb. HWO would be specifically optimized for exoplanet characterization, including the search for biosignatures. It's not scheduled to launch for at least a decade, but it represents the direction the field is heading.

European partners are developing the Extremely Large Telescope and other ground-based facilities. These earth-bound observatories won't match space telescopes' capabilities, but they'll be available for follow-up observations and can operate continuously without the oversubscription constraints that plague space missions.

Private space companies are developing their own observatories. Blue Origin, for instance, has proposed space-based telescopes for various scientific purposes. Whether that materializes remains to be seen, but it signals a shift in who can develop space-based science infrastructure.

In this landscape, Pandora occupies a specific niche. It bridges the gap between Webb's exceptional sensitivity and the limitations on how much time Webb can allocate to systematic exoplanet characterization. As future missions come online, Pandora's role will evolve or diminish. But for the next 5-10 years, it's uniquely positioned to address a specific, critical problem.

The mission also serves another purpose: proving that focused, efficient space missions can deliver high-quality science. In an era where space budgets are constrained and public skepticism of government spending is high, Pandora demonstrates that you don't need

The Quiet Work of Validation

Science rarely moves in dramatic leaps. More often, it advances through unglamorous work: measuring things carefully, checking previous results, resolving uncertainties. The scientists who do this work often get less attention than those announcing spectacular discoveries.

Pandora represents that mode of science. It's not discovering new worlds. It's not revolutionizing our understanding of the universe. It's validating, characterizing, and resolving ambiguities in observations made by more famous telescopes.

But that validation is essential. It's the difference between knowing something and being confident we know it. And in the search for potentially habitable worlds—one of humanity's most profound scientific quests—confidence matters tremendously.

When historians of science look back at the 2020s and 2030s, they might find that the most important exoplanet discoveries came from detailed characterization enabled by Pandora, not from spectacular finds announced in press releases. They might discover that the modest satellite launched in January 2025 from California was the lynchpin that allowed the field to move forward from speculation to systematic knowledge.

That would be a fitting legacy for a mission that cost 1.5 percent of Webb's budget and launched with minimal fanfare.

FAQ

What is stellar contamination in exoplanet observations?

Stellar contamination occurs when the chemical signatures from a star's atmosphere mix with signals from a planet's atmosphere during spectroscopic observation. When light passes through both atmospheres—the star's and the planet's—the resulting spectral data contains features from both sources. This makes it impossible to determine whether detected molecules like water or methane are coming from the planet or the star without additional reference data about stellar behavior.

How does Pandora solve the stellar contamination problem?

Pandora observes target stars continuously for 24-hour periods, 10 times per year, to map all changes in stellar brightness, composition, and activity across different timescales. This creates a detailed reference model of stellar variability that scientists can use to correct Webb observations of the same targets. By understanding exactly how the star's spectrum changes, researchers can subtract the stellar contribution from planetary observations, leaving only the planetary atmospheric signal.

What makes Pandora different from the James Webb Space Telescope?

Webb is more sensitive and powerful, but its schedule is completely overbooked, with roughly 4 times more observation requests than available time. Pandora is smaller and less sensitive, but it operates independently with a focused mission: characterizing stellar variability. Pandora can stare at targets for extended periods without competing for limited telescope time, making it ideal for systematic observations that Webb's schedule can't accommodate.

What are the 20 target planets Pandora will observe?

Pandora targets a carefully selected sample of small, potentially habitable exoplanets around relatively nearby stars. Most have been previously detected by missions like Kepler and have shown evidence of being rocky worlds in their star's habitable zone. The targets represent various stellar types and ages, providing a diverse sample for studying the relationship between stars and potentially habitable planets. Exact target selections were made through community proposals evaluated for scientific return.

When will Pandora produce its first results?

Pandora began science operations in spring 2025 after its commissioning phase. Initial results from stellar variability measurements will emerge in late 2025 as the first targets are observed. The most significant scientific payoff comes in 2026-2027, when combined Webb and Pandora observations of the same targets are analyzed together. The full Pandora archive becomes available for widespread scientific use after the mission's prime operations conclude in January 2026, with analyses and discoveries continuing for years afterward.

Why does a small telescope like Pandora matter if Webb is so much more powerful?

Webb's power comes with a cost: extreme oversubscription means most requested observations aren't approved. Pandora solves a specific, critical problem that Webb can't systematically address: characterizing stellar variability to validate exoplanet atmospheric measurements. By removing stellar contamination from Webb's data, Pandora makes those observations far more reliable. Think of it as quality control for exoplanet science. Pandora doesn't compete with Webb; it enhances the value of Webb's observations.

Could Webb do Pandora's job if given enough time?

Theoretically, yes. Webb could observe stars to measure their variability as Pandora does. But practically, no. Webb's demand far exceeds available time, with nearly 80 percent of proposals rejected. Adding Pandora's work to Webb's schedule would require canceling other high-priority observations. A dedicated, efficient mission like Pandora accomplishes the task at a fraction of the cost and without consuming irreplaceable Webb time. It's more effective to have two complementary missions working simultaneously.

What will scientists do with Pandora's data?

The immediate application is correcting exoplanet atmospheric observations made by Webb and other telescopes. Beyond that, Pandora's detailed stellar observations will advance stellar physics directly, improving understanding of how stellar activity cycles work, how magnetic fields vary with stellar properties, and how age and rotation influence stellar behavior. The mission's archive will be publicly available, allowing scientists worldwide to use the data for research spanning exoplanet characterization, stellar physics, and potentially other applications not yet anticipated.

What does Pandora's success look like?

Success means Pandora operates reliably for its one-year prime mission, collecting high-quality data on stellar variability for its 20 targets. It means astronomers can use that data to correct Webb observations and dramatically improve the reliability of exoplanet atmospheric measurements. It means that within 2-3 years, papers begin appearing showing combined Webb-Pandora analyses that demonstrate significantly reduced uncertainty in planetary atmospheric composition. Most importantly, it means the scientific community gains confidence that when exoplanet discoveries are announced, those discoveries are built on solid, contamination-corrected data.

Is Pandora looking for alien life directly?

No. Pandora doesn't have instruments capable of detecting biosignatures or directly observing life. Its role is supporting the detection of biosignatures by other instruments. By characterizing stellar contamination, Pandora enables more reliable measurements of planetary atmospheric composition. If and when biosignatures are detected by future telescopes, those detections will be more credible because stellar contamination has been properly accounted for thanks to data like Pandora provides.

Key Takeaways

- Stellar contamination—mixing of chemical signatures from stars and planets—was only recognized as a serious problem around 2017-2018, after Webb was already in development.

- Pandora solves this by observing 20 target exoplanets 10 times each over one year, mapping stellar variability that scientists can use to correct Webb's observations.

- The mission costs $20 million (1.5% of Webb's budget) because it uses focused mission design and proven technology rather than pushing technical boundaries.

- Webb's schedule is completely overbooked with 4:1 rejection ratios, making a dedicated complementary mission like Pandora essential for systematic exoplanet characterization.

- Real results combining Pandora and Webb data should emerge in 2026-2027, enabling the field to move from speculative exoplanet discoveries to validated atmospheric characterization.

Related Articles

- NASA's Crew-11 Early Return: What the Medical Concern Means [2025]

- Navigating Unknown Terrain: NASA's Decision to Return Astronauts Home Amid Medical Concerns [2025]

- Lazuli Space Observatory: The Private Space Telescope Revolution [2025]

- NASA's Science Budget Crisis Averted: What Congress Just Saved [2026]

- Saturn-Sized Rogue Planet Found in Einstein Desert [2025]

![NASA's Pandora Telescope: Finding Earth 2.0 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-s-pandora-telescope-finding-earth-2-0-2025/image-1-1768246695927.jpg)