The Silent Invasion: When Flesh-Eating Parasites Cross Borders

Picture this: a wound that won't heal. It's not infected in the traditional sense, but something is actively moving inside it, burrowing deeper by the hour. You look closer and realize what you're seeing isn't just inflammation. It's larvae. Hundreds of them. Feeding on living tissue while their host remains conscious, feeling every twist and turn.

This isn't science fiction. This is the reality facing clinicians across America right now, and the CDC just sent out a formal health alert to make sure doctors, veterinarians, and health workers are prepared according to the CDC.

The culprit is the New World Screwworm, a parasitic fly that stopped being a common threat in the United States decades ago. But it never truly disappeared. It just retreated to Central America and Mexico, biding its time. Now, after breaching the biological barriers we spent years constructing, it's marching back toward the U.S. border with increasing velocity. Eight active animal cases have been reported in Tamaulipas, Mexico, just across from Texas, and the CDC is sounding the alarm before we see human cases on American soil.

What makes the screwworm so terrifying isn't just what it does to the body. It's how relentless it is, how quickly it can turn a minor wound into a life-threatening infection, and how close we've allowed our defenses to deteriorate. This isn't a story about exotic diseases from distant lands anymore. This is about a threat that was nearly eradicated from the United States, then allowed to regain ground. And now doctors need to be ready.

Here's everything you need to understand about screwworm flies, why they're dangerous, how they work, and what you should do if you ever encounter one.

TL; DR

- Active threat: Eight confirmed screwworm cases in Tamaulipas, Mexico, just 70 miles from the Texas border

- Higher stakes: The CDC has issued a formal health alert to all U.S. clinicians, signaling genuine public health concern

- What to watch for: Wounds with visible maggots, unexplained tissue destruction, and sensations of movement inside an injury

- Immediate action: Remove all larvae immediately and dispose in sealed containers of 70% ethanol

- Historical context: Screwworms were eradicated from the U.S. in 1966 but have re-invaded after a barrier breach in 2022

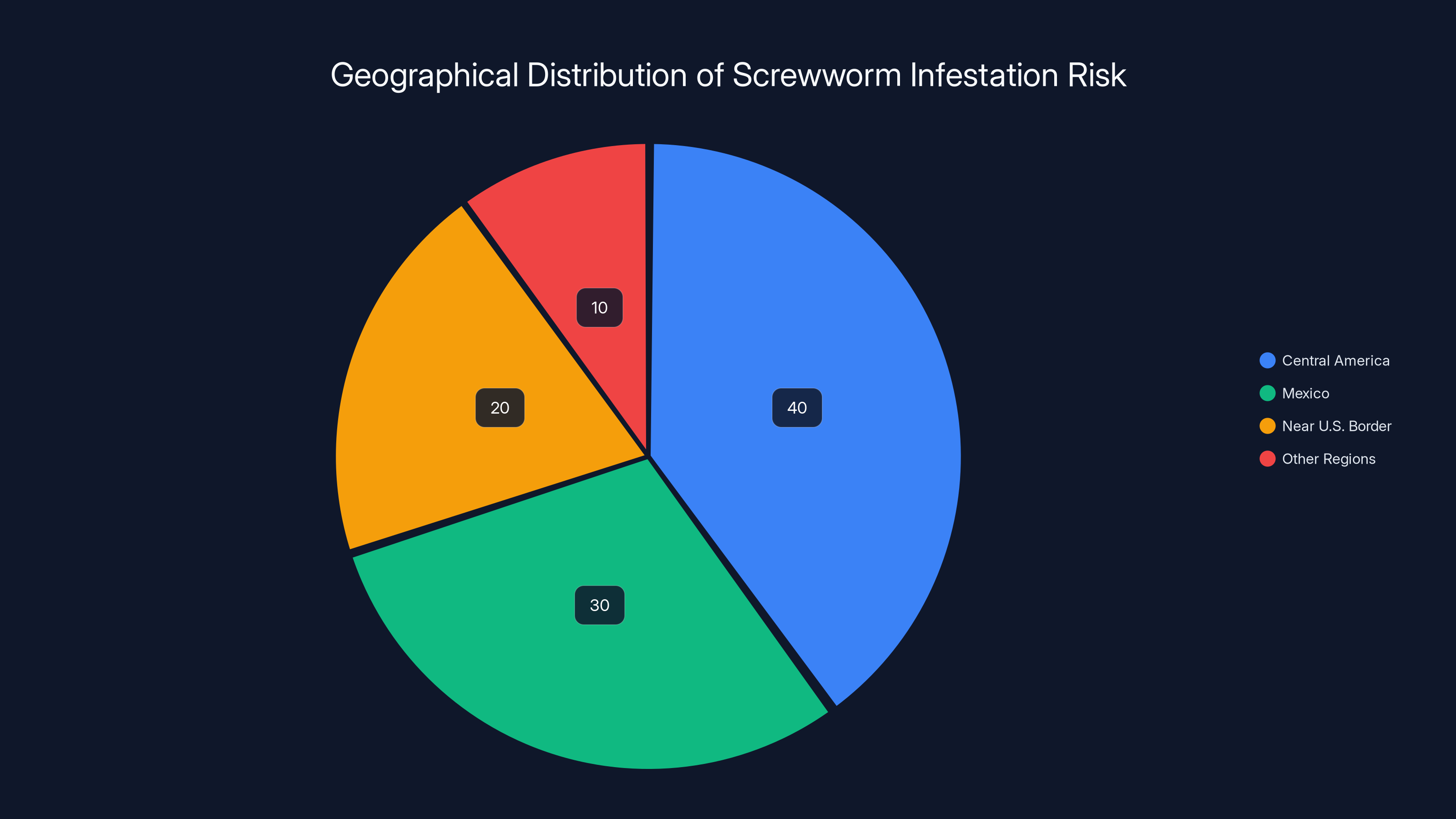

Estimated data shows that the highest risk of screwworm infestation is in Central America (40%) and Mexico (30%), with increasing risk near the U.S. border (20%).

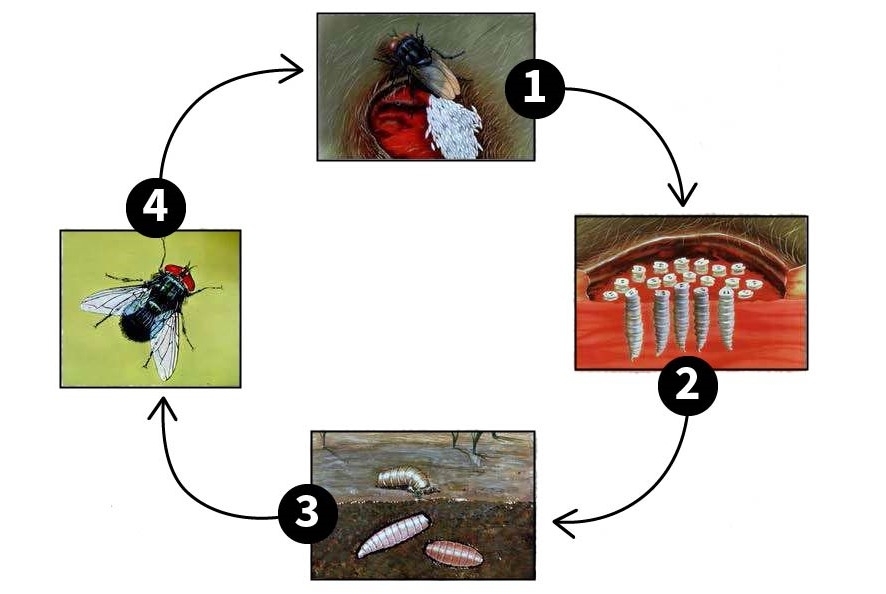

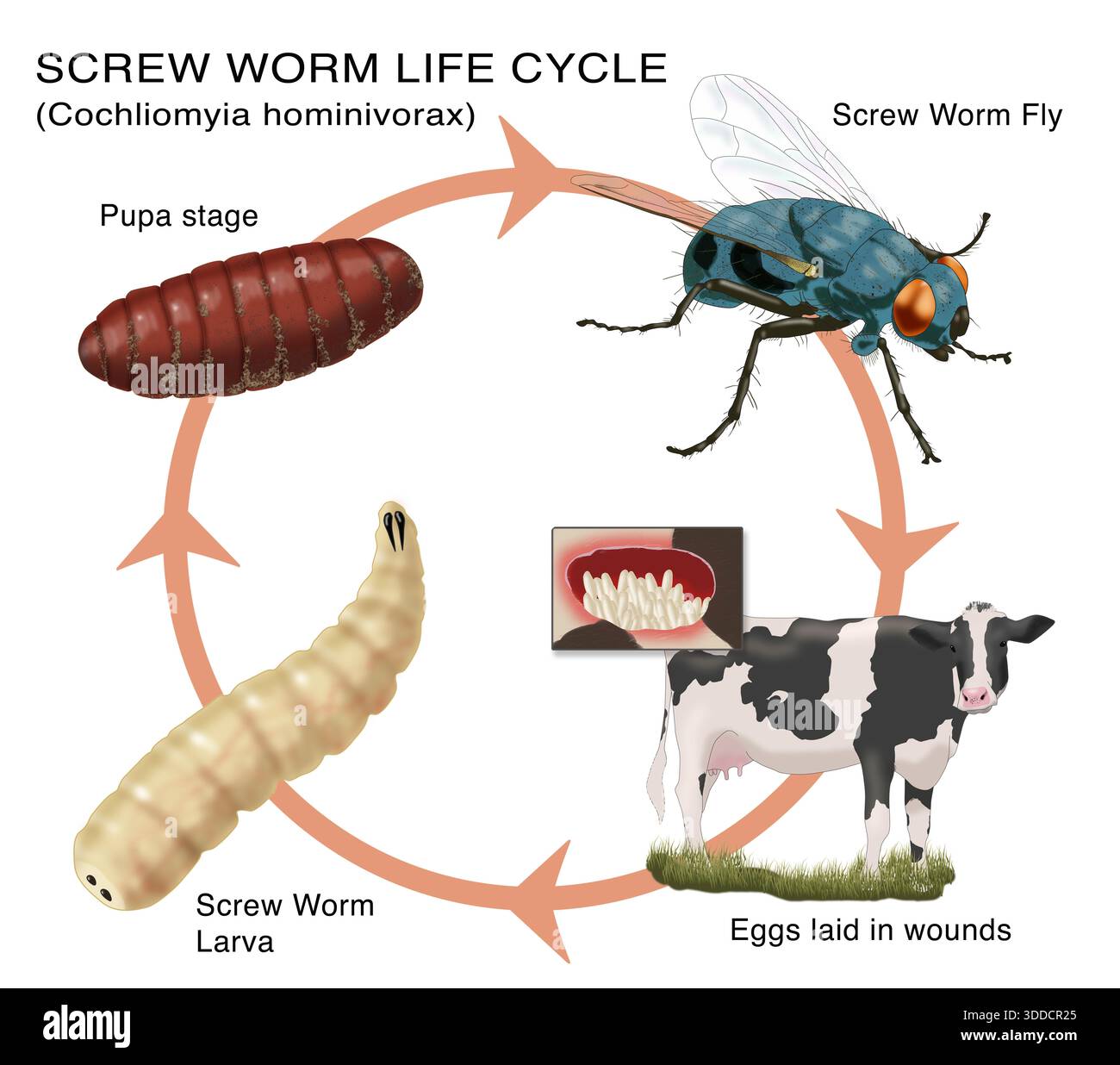

Understanding the New World Screwworm: A Parasite's Life Cycle

What Exactly Is a Screwworm Fly?

The New World Screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) is a dipteran fly, meaning it belongs to the order that includes house flies, mosquitoes, and fruit flies. But similarities end there. While other flies are merely annoying, the screwworm is one of nature's most devastating parasites. The adult fly is relatively small, roughly the size of a house fly, with a metallic greenish-blue body and distinctive red eyes. You wouldn't immediately identify it as dangerous if you saw one.

But the damage comes not from the adult fly itself. It comes from what the fly creates.

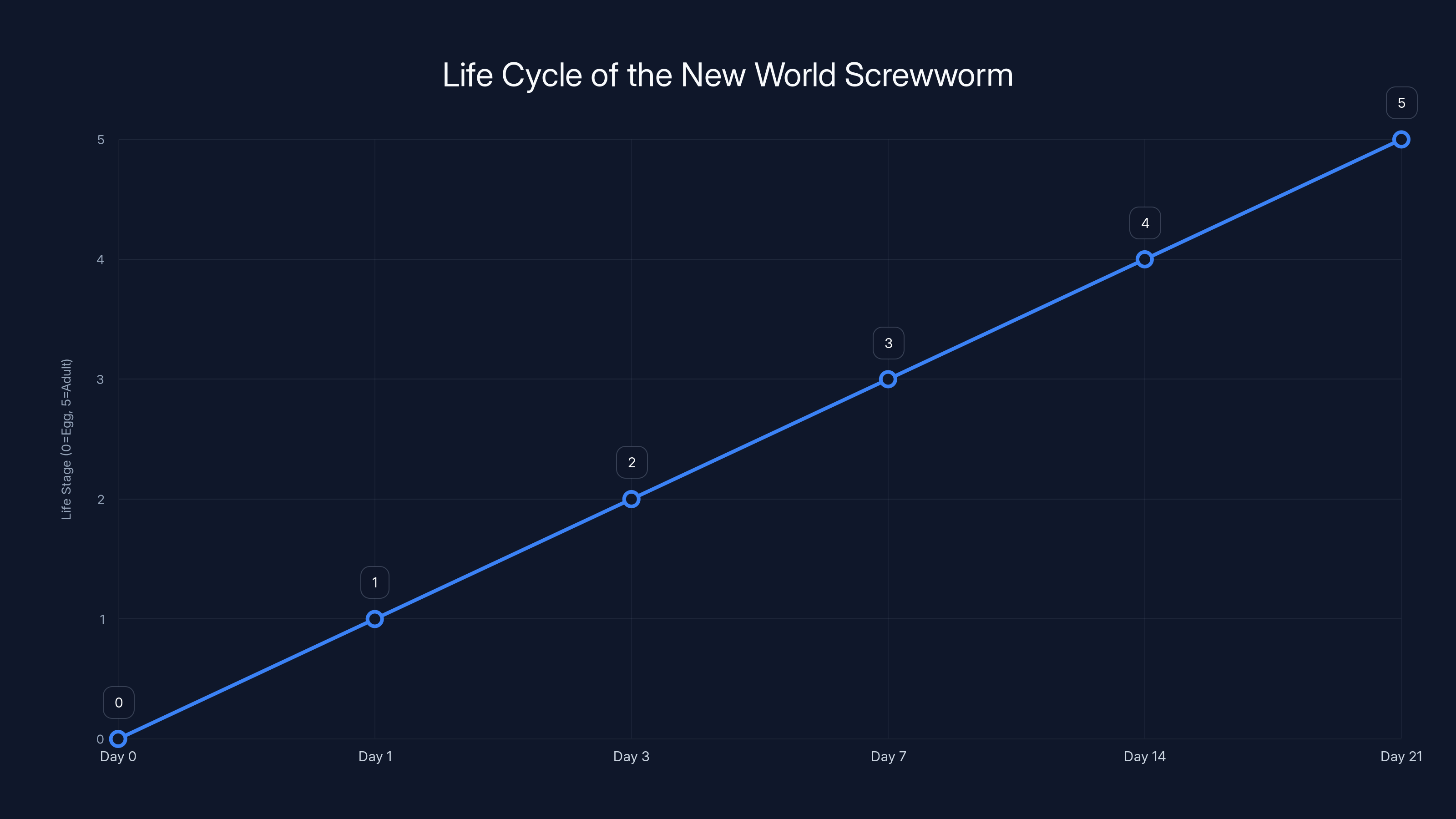

Female screwworms are monogamous in a biological sense. They mate once during their entire 21-day lifespan, and that mating lasts only minutes. After copulation, the female carries millions of sperm and will use them to fertilize eggs throughout her remaining life. She doesn't need another mate. This reproductive strategy, which seems elegant in nature, becomes her defining characteristic when humans try to control the species.

When a female screwworm finds a suitable host—and a suitable host can be virtually any warm-blooded animal with a wound or opening—she doesn't lay eggs inside the wound immediately. Instead, she deposits between 100 and 400 eggs in a carefully organized clutch, almost always on the edge of a wound, around the nostrils, ears, or other body orifices. She times this precisely to ensure her offspring will have fresh tissue to feed on when they hatch.

The Larval Stage: Where the Horror Begins

The eggs are tiny, cream-colored, and virtually invisible. They hatch within 24 hours, sometimes sooner depending on temperature. What emerges are first-instar larvae, maggots measuring just a fraction of a millimeter in length. To the naked eye, they're barely visible as individual organisms. But there are hundreds of them, all emerging simultaneously, all driven by the same biological imperative: find flesh and feed.

This is where the screwworm earned its name. The larvae don't simply sit on the surface of a wound and feed like ordinary fly maggots. Instead, they bore downward into living tissue with a motion that resembles the turning of a screw. Their anterior end contains a small conical structure ringed with tiny hooks. Using these hooks as anchors and rhythmic muscular contractions, they twist deeper and deeper into the flesh.

As they feed, they secrete proteolytic enzymes that break down tissue, creating a pathway for deeper penetration. They also produce anticoagulants that prevent blood clotting, ensuring a constant supply of blood and body fluids to feed on. The wound becomes increasingly necrotic, increasingly infected, increasingly infested. A small initial wound can become a massive, gaping cavity within days.

The larvae grow through three instars, or development stages. In warm conditions, this process takes as little as 5-7 days. Each instar is larger and more voracious than the last. A third-instar larva can consume its own body weight in flesh daily. When you multiply that by hundreds of larvae, all growing simultaneously in the same wound, the tissue destruction becomes catastrophic.

Pupation and Adult Emergence

Once the larvae have fed sufficiently, they leave the wound and burrow into soil or sand to pupate. This stage lasts 7-10 days, and during this time the fly is vulnerable. It can be killed by desiccation, temperature extremes, or physical disturbance. But if conditions are right, an adult fly emerges, waits for its exoskeleton to harden and its wings to fully expand, and then takes flight to find a mate and continue the cycle.

Under ideal conditions, a complete life cycle from egg to adult takes about 3-4 weeks. This rapid reproduction, combined with the fly's ability to infest multiple hosts, creates exponential population growth. One female fly can spawn thousands of offspring. Those offspring mate and reproduce within weeks. The population explodes.

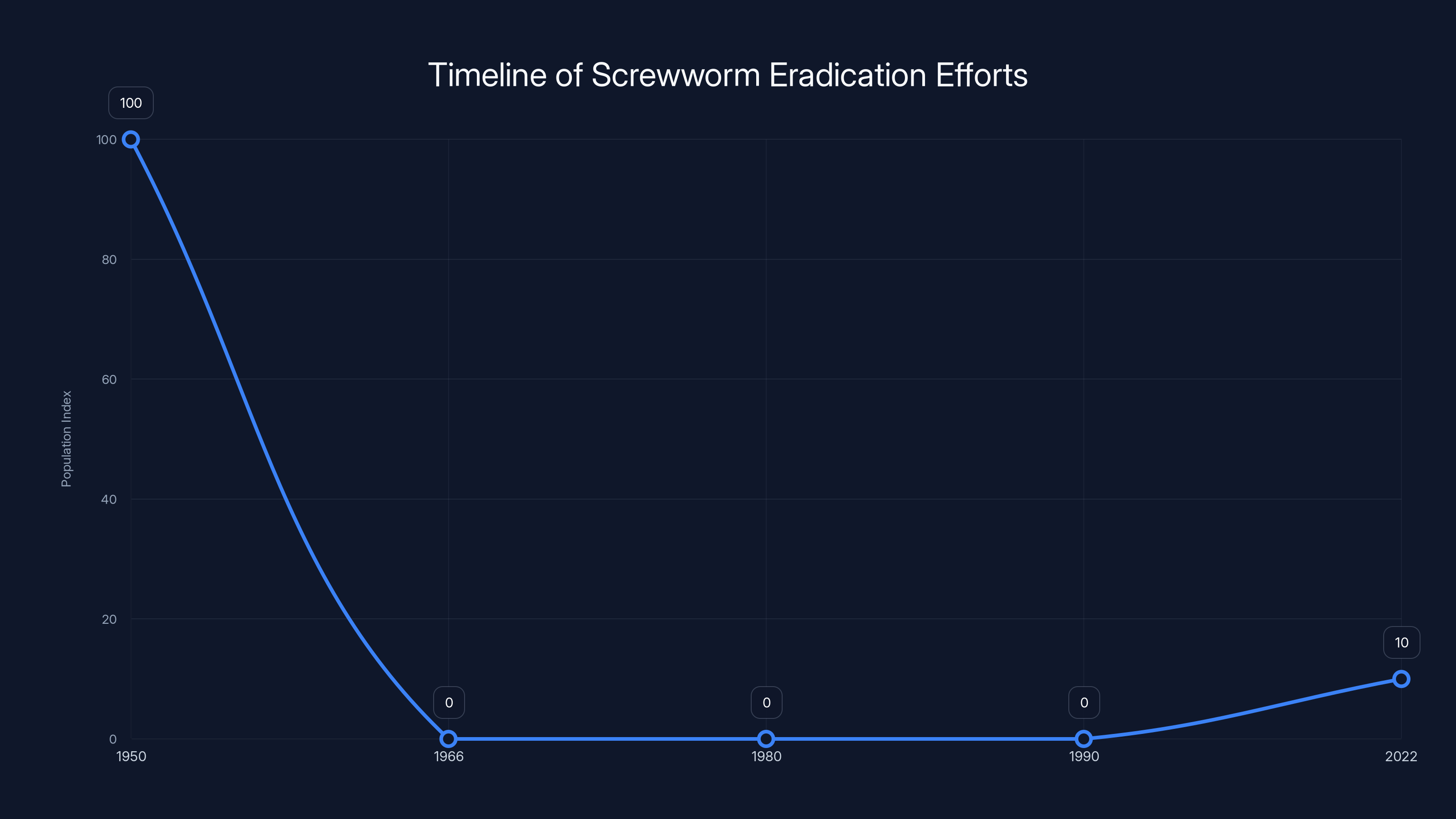

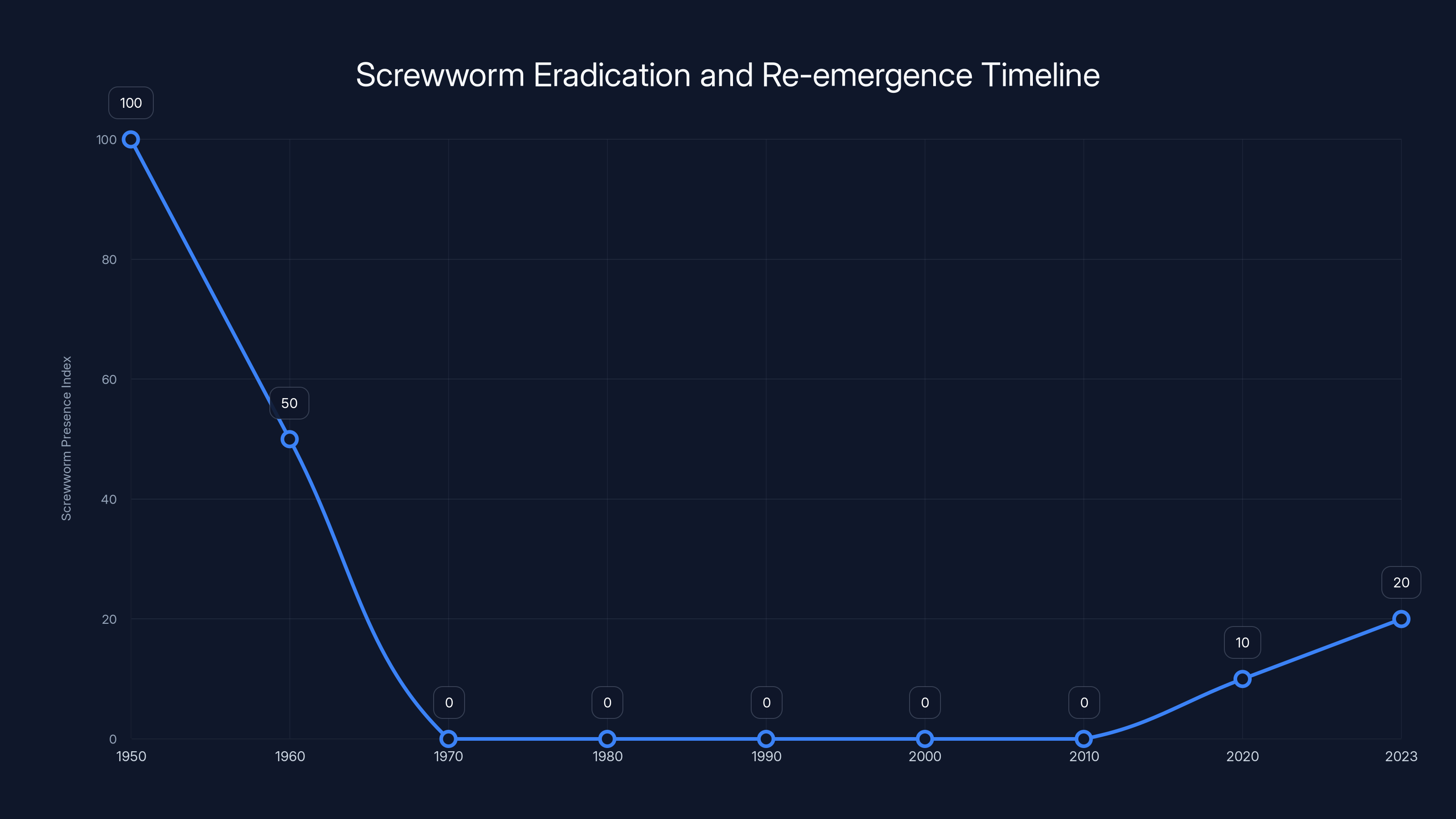

The screwworm population in the U.S. was eradicated by 1966 due to the Sterile Insect Technique. However, a breach in 2022 led to a resurgence. Estimated data.

The Clinical Reality: What Screwworm Infestation Looks Like

Early Signs and Symptoms

The earliest sign of screwworm infestation is often a wound that simply won't heal. Patients might come to a clinic with what they believe is a normal puncture wound, laceration, or surgical incision that should be healing normally. But instead of improving, the wound shows signs of progressive tissue destruction. The edges may become increasingly inflamed and necrotic. Drainage becomes purulent or bloody. Pain increases despite appropriate wound care.

Many patients report a sensation of movement within the wound. They describe it as a crawling, twitching, or wriggling feeling. In deeper wounds, they might report feeling something moving inside their body. These reports should immediately raise suspicion of parasitic infestation, particularly in patients with recent exposure to endemic areas.

Some patients notice what appears to be sand or grit in the wound. These are the larvae. In other cases, the movement might be subtle enough that the patient overlooks it, attributing the sensation to normal inflammatory pain.

Fever is common, though it's usually low-grade. Systemic symptoms develop as the infestation progresses. Some patients become septic if secondary bacterial infection sets in. Interestingly, screwworm wounds are often less putrid and odorous than typical infected wounds, because the larvae actively prevent certain anaerobic bacteria from establishing themselves. The fly's digestive enzymes and the wound's aerobic nature create an environment that's less hospitable to traditional pathogens.

Advanced Infestation: When Hours Matter

Left untreated, screwworm infestation can become life-threatening with shocking speed. The larvae don't respect anatomical boundaries. They can burrow through skin into subcutaneous tissue, into muscle, and potentially into body cavities. Cases have been documented of larvae reaching bone, and there are historical reports of facial infestations where larvae burrowed toward vital structures.

In animals, the progression is often more dramatic. An infected cow might go from appearing normal to showing signs of severe illness within 48-72 hours. The animal becomes lethargic, stops eating, and develops fever. If the infestation is in the nasal passages, breathing becomes labored. If it's in the eye, vision is lost. The economic losses to livestock farmers are staggering.

For humans, while progression is generally slower than in livestock, the consequences are no less serious. Secondary bacterial infection can lead to sepsis. Larval migration into the orbit can cause blindness. Larvae in the nasopharynx can compromise the airway. The CDC has documented cases in Mexico where patients required hospitalization for days and faced permanent disfigurement or loss of function.

The Historical Context: How We Nearly Eliminated Screwworms

The Era of Eradication

Most Americans under 50 have never heard of screwworms, and that's by design. In the early 20th century, before pesticides and coordinated eradication efforts, screwworms were a scourge of American agriculture. Livestock ranchers lost thousands of animals annually. The economic impact on farming was substantial.

But by mid-century, scientists realized something crucial: screwworms had a weakness that could be exploited. Female screwworms mate only once. This biological constraint meant that if you could flood an area with sterile males, you could essentially crash the population through reproductive failure. This became known as the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT), and it represented a revolutionary approach to pest control.

The USDA launched a massive screwworm eradication program in the 1950s. Scientists developed the ability to mass-produce screwworms in laboratory conditions, expose the males to radiation to render them sterile, and then release them in enormous numbers into affected areas. The math was elegant: one sterile male for every wild female should theoretically prevent 50% of matings. Release more than that, and the population crashes exponentially.

By 1966, less than two decades after the program began, screwworms had been eliminated from the United States entirely. By the 1980s and 1990s, coordinated international efforts had pushed the boundary of screwworm territory further and further south. The flies were eliminated from Guatemala, then El Salvador, then Honduras. The biological barrier was pushed to Panama, then held there. The threat seemed vanquished.

The Breach of 2022 and the Northern March

But in 2022, the carefully maintained barrier failed. Exactly how screwworms breached the Darién Gap remains unclear, though investigators point to increased human activity in the region, unregulated cattle movements, and gaps in the sterile fly release program as contributing factors. Once the barrier was breached, the flies had a clear path northward through Central America and Mexico toward the United States.

The re-invasion has been swift. By 2024, over 1,190 human cases had been recorded across Central America and Mexico, with seven deaths confirmed. Over 148,000 animals had been infested. The flies were no longer a theoretical threat. They were a present emergency.

The 2016 Florida Keys Episode

Interestingly, this isn't the first time in recent decades that screwworms have attempted to return to U.S. territory. In 2016, the flies inexplicably appeared in the Florida Keys, infesting Key Deer, an endangered species endemic to the islands. How the flies arrived remains a mystery. Some researchers suspect illegal importation of livestock or accidental transport via cargo. However it happened, the infestation threatened a species that numbered fewer than 1,000 individuals.

The response was swift. Federal and state authorities immediately deployed the sterile insect technique. Within months, every wild screwworm in the Keys had been eliminated. The Key Deer population was saved. But the incident demonstrated that screwworms could potentially establish themselves in the U.S. again if given the opportunity.

The New World Screwworm progresses from egg to adult in approximately 21 days, with each stage critical for survival. Estimated data based on typical life cycle.

Current Situation: The Warning Signs We Can't Ignore

What's Happening in Mexico Right Now

As of early 2025, the screwworm situation in Mexico is serious but still contained south of the U.S. border. The state of Tamaulipas, which borders the southern tip of Texas, is currently experiencing a flare-up. Eight active animal cases have been confirmed in recent months. Nuevo León, another border state, has reported three cases, though none are currently active.

Mexico overall has recorded 24 hospitalizations among humans and 601 confirmed animal cases. These numbers are both alarming and incomplete. Authorities suspect that many cases, particularly in rural areas, go unreported.

The USDA is currently responding by releasing 100 million sterile male screwworms per week in Mexico. This massive sterile insect program is attempting to establish a new biological barrier and prevent further northward expansion. It's the largest ongoing SIT program in the world, and it represents both hope and desperation. Hope because we know the technique works. Desperation because we're having to deploy it at all after having already won this battle once.

The September 2024 Wake-Up Call

In September 2024, a reality check arrived in the form of an 8-month-old cow in a feedlot in Nuevo León, Mexico. The animal tested positive for active screwworm infestation. The feedlot was located just 70 miles from the Texas border. The find prompted Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller to issue stark warnings: "The screwworm is dangerously close. It nearly wiped out our cattle industry before. We need to act forcefully now."

Those 70 miles suddenly felt like nothing. Commercial cattle movements across the U.S.-Mexico border are frequent and complex. A single infested animal could theoretically cross the border and begin infesting other livestock before anyone noticed. The epidemiological implications were sobering.

The Mechanism of Transmission: How Animals and People Get Infected

Wound Contamination and Environmental Exposure

Screwworms don't burrow under intact skin like certain parasitic worms. They require an opening: a wound, a ulcer, a surgical incision, or a mucus membrane. The fly finds this opening by following chemical signals released by the wound. Open wounds release volatile compounds that screwworm flies can detect from surprising distances.

Once a female locates a suitable wound, she deposits her eggs. She doesn't need to enter the wound herself. She can position herself at the edge and lay her clutch at the precise location where they'll hatch and immediately find fresh tissue to feed on.

For livestock, this typically happens on ranches or pastures where cattle are exposed to insect vectors. Calving season is particularly dangerous because newborn animals are vulnerable, and the birthing process leaves obvious wounds. But screwworms aren't strictly livestock parasites. They can infest wild animals, pets, and humans.

Human Infection Routes

In endemic regions, human infections typically occur when a person has an open wound and is exposed to screwworm flies. This might happen in occupational settings like construction or agriculture, or through accidents like motor vehicle injuries with open fractures. Some human cases have involved surgical wounds that became contaminated.

The CDC has also documented cases in travelers returning from endemic regions. A person might sustain a minor wound while visiting Central America or Mexico, return to the United States before symptoms develop, and only later realize they've been infested with screwworm larvae.

Personal hygiene appears to play a significant role. Clinicians in endemic areas have noticed that infections are more common in people with limited access to clean water, poor wound care supplies, or conditions that make wound management difficult. Diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and other conditions that impair wound healing increase vulnerability.

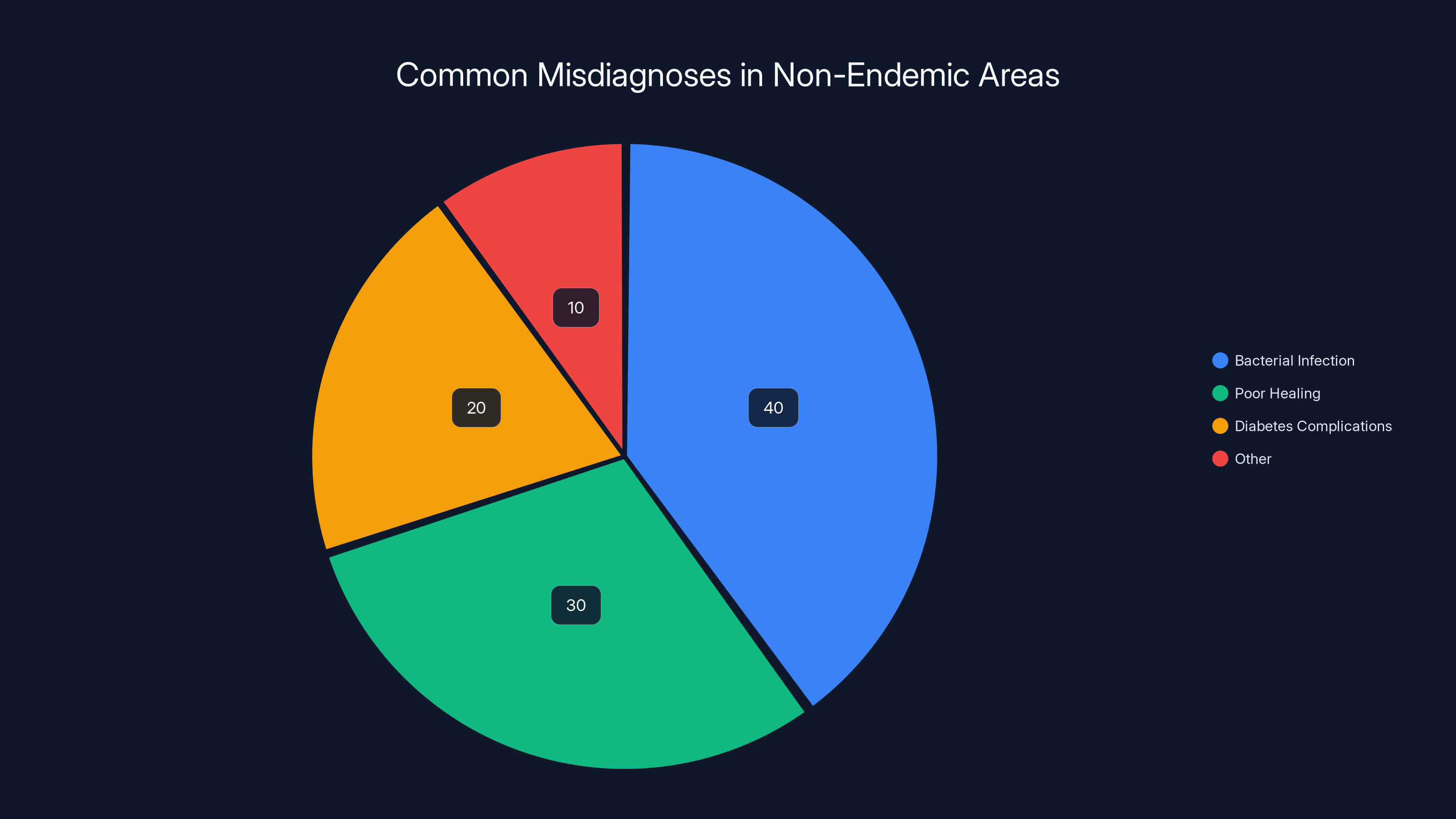

Estimated data suggests that bacterial infections are the most common misdiagnosis for screwworms in non-endemic areas, followed by poor healing and diabetes complications.

Diagnosis: Recognizing What You're Actually Looking At

Clinical Diagnosis

The gold standard for screwworm diagnosis is visual identification of larvae in a wound. But clinicians in non-endemic areas might not immediately recognize them. Screwworm larvae look like other fly maggots, though they have some distinctive features. They're pink or whitish, roughly cylindrical, and 5-15 mm long depending on their instar. Under magnification, the characteristic respiratory spiracles (breathing holes) on the posterior end are visible.

The larvae are remarkably mobile. They'll continue moving even after removal from the wound, which can be startling to healthcare workers unfamiliar with the condition. This mobility, combined with the characteristic damage pattern and the pattern of tissue destruction, usually makes diagnosis relatively straightforward once someone considers the possibility.

The challenge isn't identifying screwworms when you're specifically looking for them. The challenge is having screwworms enter your differential diagnosis in the first place. For a clinician in Texas or Florida, the tendency is to attribute wound problems to common causes: bacterial infection, poor healing, complications from diabetes. A flesh-eating parasitic fly might not immediately come to mind.

This is precisely why the CDC issued the health alert. Raising awareness among clinicians means screwworm diagnosis will come sooner, before larvae have had weeks to burrow deeper and cause more damage.

Laboratory Confirmation

For definitive confirmation, the CDC recommends sending at least 10 dead larvae to a reference laboratory. The larvae should be collected from the wound, killed by placing them in 70% ethanol in a sealed, leak-proof container, and then shipped immediately to a laboratory equipped to provide species identification.

Histologic examination of larvae under a microscope can confirm the presence of screwworms. The characteristic cephalic index (the ratio of head width to body width), the structure of the anterior spiracles, and other anatomical features allow definitive species identification. Genetic testing can also be performed if there's any uncertainty.

Treatment: What Actually Works

Physical Removal and the Importance of Completeness

Unlike many parasitic infections, screwworm infestation is primarily treated through mechanical removal rather than medication. Every single larva must be removed from the wound. Even one surviving larva can continue feeding, reproducing, and infesting new areas of tissue. Incomplete removal is treatment failure.

The CDC specifically emphasizes this point. In their health alert, they state in bold: "Failure to kill and properly dispose of all larvae or eggs could result in the new introduction and spread of NWS in the local environment." This warning isn't about perfect disinfection. It's about preventing larvae from escaping the healthcare facility and re-establishing infection in the wild.

Historically, various methods have been used to remove and kill screwworm larvae. The current CDC recommendation is to drown them in sealed, leak-proof containers filled with 70% ethanol. This method is efficient, ensures all larvae are killed, and prevents any from escaping the facility.

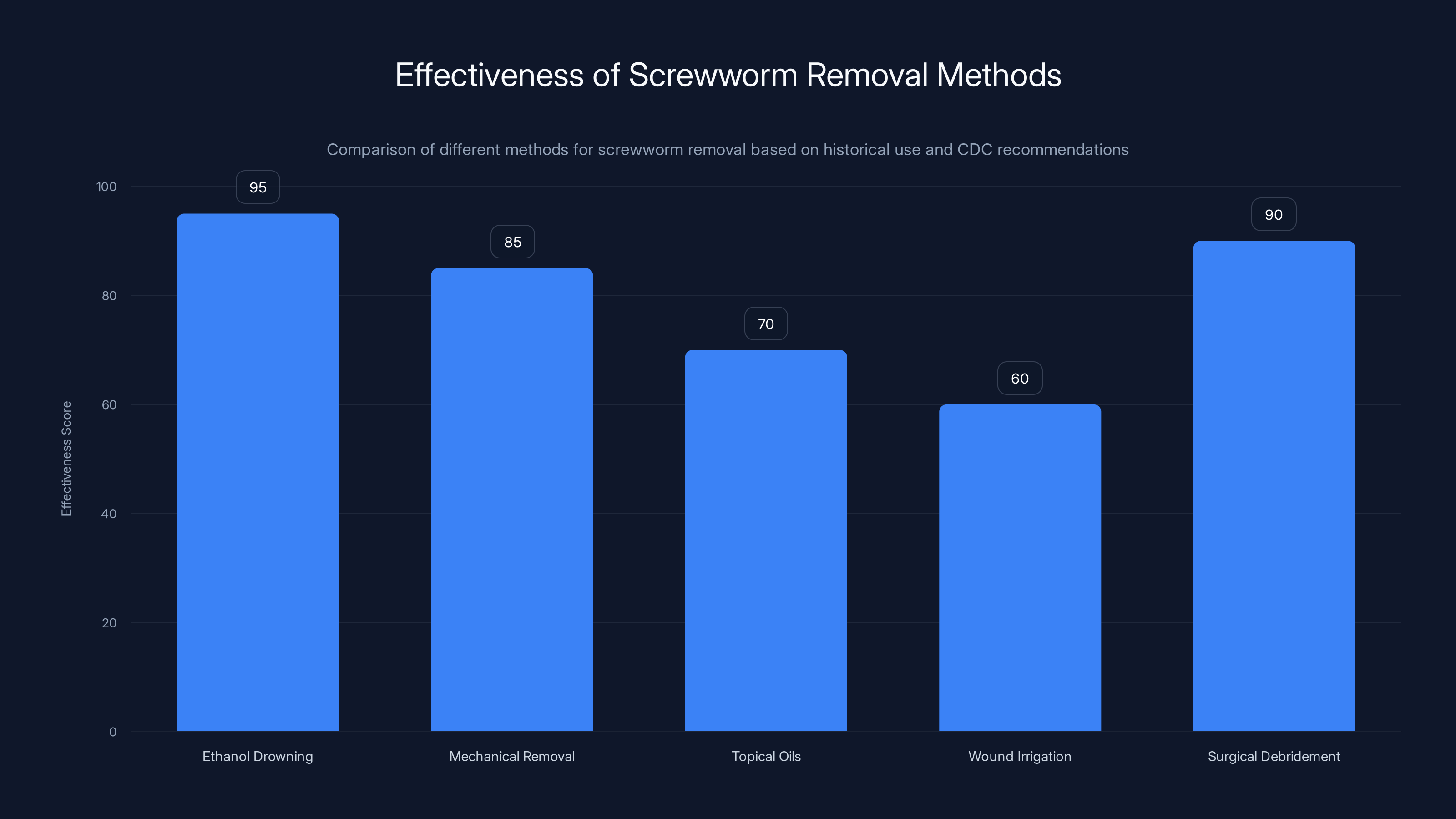

Other methods that have been used include:

- Mechanical removal with forceps or tweezers followed by immediate immersion in disinfectant solution

- Topical application of oils or petroleum jelly to suffocate larvae and make them more visible

- Irrigation of the wound with antiseptic solutions

- Surgical debridement of severely affected tissue

Depending on the extent of infestation and tissue damage, wound care might require local anesthesia or sedation. Extensive infestations might require multiple debridement sessions over consecutive days.

Medical Adjuncts

While mechanical removal is primary, supportive care is crucial. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered to address secondary bacterial infection. Depending on the location and extent of the wound, tetanus prophylaxis should be provided if indicated.

Wound care itself—cleaning, dressing, and monitoring for healing—follows standard principles. Some clinicians have reported that topical antibiotics may help prevent secondary infection while the wound heals. However, the larvae themselves are resistant to most antibiotics, so antibiotics aren't a primary treatment. They're adjunctive.

In cases where larvae have migrated into eyes, the nasopharynx, or other sensitive areas, ophthalmologic, otolaryngologic, or surgical consultation might be necessary. The goal is always complete removal while minimizing collateral damage to the patient's tissues.

The successful eradication of screwworms in the 1960s led to their absence until recent re-emergence due to weakened barriers. Estimated data.

Why Screwworms Are Different From Other Parasitic Flies

Comparing to Myiasis

Myiasis is the medical term for infestation of human or animal tissue with dipteran larvae. It includes a range of conditions from relatively benign fly maggot infestations to severe tissue-destroying parasitism. Screwworm infestation is one form of myiasis, but it's particularly severe.

Other dipteran larvae can cause myiasis. Botflies, for example, lay eggs that develop into larvae that burrow under the skin but typically cause less tissue destruction than screwworms. Blowfly larvae are capable of feeding on dead tissue (useful for surgical debridement) but can also consume live tissue if given the opportunity.

What makes screwworms unique is their aggressive tissue penetration, their rapid reproduction, and their ability to thrive in living tissue while actively preventing wound healing. Other parasitic flies are opportunistic. Screwworms are specialized predators.

Evolutionary Adaptation

From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense. The screwworm fly evolved in the Americas, likely in South America, where warm-blooded large animals provided abundant hosts. Over thousands of years, screwworms became exquisitely adapted to invading, colonizing, and feeding on living tissue. Their larvae produce enzymes specifically designed to break down living muscle and connective tissue. Their anterior hooks are precisely shaped for boring into flesh.

This specialization is what makes them so dangerous and what makes them so difficult to control without extreme measures. They're not incidental parasites like botflies, which develop relatively slowly and can be managed with basic wound care. Screwworms are obligate parasites of living tissue, meaning they require fresh, viable tissue to survive. They must be dealt with aggressively and immediately.

Prevention: What Can Actually Reduce Risk

Wound Care Best Practices

The most fundamental prevention is proper wound care. Any open wound, no matter how minor, should be cleaned, disinfected, and covered. In endemic areas, this is especially critical. A small cut from agricultural equipment, a surgical incision, or a burn can become a screwworm entry point if left open and exposed.

For people living in or traveling to endemic regions, wound care should include:

- Immediate cleaning of any cut or scrape with soap and water

- Application of antiseptic (iodine-based or alcohol-based disinfectants)

- Covering the wound with a sterile dressing

- Monitoring the wound daily for signs of infection or infestation

- Seeking medical care if wound appearance changes unexpectedly

For people with chronic wounds, peripheral vascular disease, or diabetes, preventive measures should be more aggressive. Daily wound inspection, professional wound care, and immediate medical attention for any concerning changes are essential.

Vector Avoidance

Screwworm flies are active during daylight hours and are attracted to wounded animals and livestock. In endemic areas, efforts to control livestock exposure to flies include using insect repellents on animals, housing animals during peak fly activity hours, and maintaining pastures in ways that reduce fly breeding sites.

For people, vector avoidance might include using insect repellents that contain DEET or picaridin when in endemic areas, particularly if working outdoors or in occupational settings with higher exposure risk.

Quarantine and Movement Restrictions

At the agricultural level, preventing screwworm spread requires controlling livestock movement. This is why unregulated cattle movement across borders is such a serious concern. A single infested animal can establish an entire new population. Quarantine procedures for livestock imported from endemic regions, regular health inspections, and swift response to suspected cases are crucial.

The USDA maintains strict regulations on importing livestock from Central America and Mexico precisely because of screwworm risk. These regulations, while burdensome to some agricultural interests, represent the hard-won knowledge gained from decades of fighting screwworm infestation.

Ethanol drowning is the most effective method for screwworm removal, ensuring all larvae are killed and preventing escape. Estimated data based on historical and current practices.

The Role of Public Health Systems: Detection and Response

Surveillance Infrastructure

Detecting screwworms before they become widespread is critical. This requires surveillance systems that can identify cases quickly and report them to relevant authorities. In the U.S., this means the CDC and USDA working together. In Mexico and Central America, it involves both national authorities and international collaboration.

Surveillance systems for screwworms include:

- Mandatory reporting by veterinarians and healthcare providers of suspected cases

- Regular inspection of livestock in border regions

- Sampling programs to detect flies that have established themselves in the wild

- Coordination with international partners to share information about cases and spread patterns

The CDC's health alert is essentially an enhancement to the U.S. surveillance system. By alerting clinicians and veterinarians to the current risk, the alert increases the likelihood that cases will be detected and reported promptly.

Response Capacity

When cases are detected, rapid response is essential. This includes immediate reporting to public health authorities, isolation of infected animals or isolation precautions for infected patients to prevent transmission, and coordinated efforts to eliminate all larvae and prevent spread.

For Mexico, this has meant a massive sterile insect program. For the U.S., it means vigilance. Ensuring that veterinary and human healthcare systems have the knowledge, supplies, and protocols to handle screwworm cases is an ongoing challenge.

The Economics: Why This Matters Beyond Medicine

Livestock Industry Impact

Screwworms have historically been among the most economically devastating parasites of livestock. Before eradication, they caused hundreds of millions of dollars in annual losses to the American cattle industry. Infested animals lose weight, require expensive veterinary treatment, and sometimes die despite treatment. Breeding animals might lose reproductive capacity from genital infestations.

For countries in Central America and Mexico, where cattle ranching represents a significant portion of the agricultural economy, screwworm infestations threaten food security and economic stability. The current situation is estimated to cause tens of millions of dollars in annual losses to Central and South American agriculture.

The sterile insect program represents an enormous financial investment. Maintaining the facility to produce 100 million sterile flies per week, transporting them to Mexico, and coordinating releases across regions costs millions of dollars annually. This is money spent not on treatment, but on prevention. And it's well spent, because the alternative—allowing screwworms to re-establish throughout the continent—would cost far more.

Healthcare Costs

For human infections, the economic impact is real but often underappreciated. Each case requires healthcare system resources. Diagnosis might require imaging if the extent of infestation is unclear. Treatment requires the time of nurses and physicians. Extensive infestations might require surgical intervention. Secondary infections might require ICU-level care.

Beyond direct medical costs, there are indirect costs: lost work productivity, potential disability if infections cause permanent damage, and the psychological trauma of having been infested by parasitic larvae.

For a developing country healthcare system, screwworm cases represent a significant drain on resources that might be redirected to other health priorities.

What Healthcare Workers Need to Know Right Now

The CDC Recommendations Summarized

The CDC's health alert provides clear guidance for healthcare providers. The key points are:

-

Be aware: Screwworms are approaching the U.S. border. Clinicians should be familiar with the condition.

-

Recognition: Wounds with visible larvae, unexplained tissue destruction, or sensations of movement should raise suspicion of screwworm infestation, especially in patients with recent travel to Mexico or Central America.

-

Reporting: Suspected cases should be reported immediately to local health departments and state veterinary authorities.

-

Specimen collection: At least 10 dead larvae should be collected and sent to the CDC for confirmation.

-

Treatment: All larvae must be removed and killed. The CDC recommends placing them in 70% ethanol in sealed containers.

-

Environmental implications: It's crucial that no larvae escape the healthcare facility or veterinary clinic. The goal isn't just to treat the individual patient but to prevent environmental establishment of screwworms in the U.S.

Veterinary Preparedness

Veterinarians, particularly those in Texas and other border states, are on the frontlines of screwworm detection. They need training on recognition, proper specimen handling, and rapid reporting. The USDA has been coordinating with state veterinary associations to ensure that practitioners have access to training and resources.

Veterinary clinics should have protocols in place for handling suspected cases, including proper specimen collection, biosafety measures to prevent larval escape, and lines of communication with USDA authorities.

Future Outlook: Can We Keep Screwworms Out?

The Sterile Insect Program: Why It Works and Why It's Fragile

The Sterile Insect Technique has proven to be the most effective method for screwworm control. The 100 million sterile flies released weekly in Mexico represent the largest application of this technique anywhere in the world. If maintained and coordinated properly, the program should prevent screwworms from establishing north of Mexico's southern border.

But the program is fragile. It requires sustained political will, consistent funding, and continued coordination between countries. It requires infrastructure to mass-produce flies at enormous scale. It requires logistics to transport flies across regions and coordinate releases. A lapse in any of these could allow the wild population to recover.

Historically, lapses have happened. The barrier in Panama weakened in the late 2010s when funding and coordination declined. By 2022, screwworms breached it entirely. The lesson is clear: maintaining eradication is harder and less glamorous than achieving initial eradication, so it's often under-resourced.

What a U.S. Establishment Would Look Like

If screwworms ever re-establish in the United States, response would be swift and massive. The USDA would likely deploy a sterile insect program in affected areas. This would be expensive and disruptive, but it would work. The U.S. has the resources to eliminate a screwworm infestation quickly.

The real danger is a period where infestations are sporadic and localized but not yet eradicated. During this window, animals and people might suffer, healthcare systems might be overwhelmed, and the economic costs could be substantial. This is precisely the situation we're trying to prevent by maintaining control in Mexico and Central America.

International Cooperation and Political Challenges

Controlling screwworms requires international cooperation. It also requires investment in regions where governments might have competing priorities. The political will to maintain a multi-million dollar sterile insect program in Mexico depends on demonstrating its value, securing funding, and ensuring that results are visible.

The current situation illustrates both the promise and the peril of this approach. The promise is that screwworms can be held back through coordinated effort. The peril is that holding them back requires sustained effort, which is more difficult politically than achieving a dramatic eradication.

Real-World Case Studies: What We Can Learn

The Florida Keys Situation

In 2016, screwworms infested Key Deer in the Florida Keys. The situation was urgent because Key Deer are endangered, with fewer than 1,000 remaining in the wild. An active screwworm infestation could have devastating consequences for the species.

The response was immediate and coordinated. Federal authorities established a sterile insect program focused on the Keys. Rather than treating individual infested deer, the approach was population-level control. Weekly releases of sterile flies continued for several months. By 2017, screwworms had been eliminated from the Keys.

The success was complete but expensive and resource-intensive. The incident demonstrated that even in the United States, with abundant resources, screwworm eradication requires immediate, aggressive action. A casual or delayed response would have resulted in establishment of a new population.

Central American Experiences

As screwworms have re-invaded Central America over the past few years, countries like Guatemala and Honduras have had to learn screwworm management in real time. Their experiences provide lessons for potential U.S. management.

One key lesson is that early detection and rapid response can prevent widespread establishment. When screwworms were first detected in re-invaded regions, quick action isolated cases and prevented spread. In some cases, regional quarantine efforts contained infestations to specific areas.

Another lesson is that farmer education is crucial. Livestock ranchers who understand screwworm risk and know how to inspect animals for infestations can provide a critical layer of detection. Farmers in endemic regions have learned to look for wounds in livestock, to practice basic wound care on animals, and to report suspected cases immediately.

The Broader Context: Why Zoonotic Disease Vigilance Matters

Screwworms as a Microbial Invasion Indicator

The re-emergence of screwworms isn't an isolated incident. It's part of a broader pattern of zoonotic disease emergence and re-emergence in recent decades. Climate change, habitat disruption, increased human-animal contact, and global trade have all contributed to patterns where diseases previously thought controlled re-emerge in new areas or with new severity.

Scalp, some other historical agricultural pathogens are similarly returning to regions where they were eradicated. The rinderpest virus, which was eradicated globally in 1980, represents the only human-caused extinction of an animal pathogen. But many other pathogens remain or have re-emerged despite control efforts.

This suggests that disease eradication is fragile. Success against one pathogen depends on sustained effort, international cooperation, and continued surveillance. Losing focus or allowing infrastructure to decay can undo decades of progress.

Lessons for Pandemic Preparedness

Screwworms offer lessons relevant to pandemic preparedness more broadly. They illustrate the importance of surveillance systems that can detect threats early. They show why international cooperation is essential for controlling pathogens that don't respect borders. They demonstrate that prevention, through measures like the sterile insect program, is far more cost-effective than treatment of widespread infection.

The CDC's proactive health alert is an example of good public health communication. It identifies a potential threat, informs healthcare workers before crisis hits, and provides clear guidance on recognition and management. This approach is more effective than waiting for cases to appear and then scrambling to inform providers.

Practical Information for Travelers and Residents

If You're Traveling to Endemic Areas

For people planning to visit Mexico, Central America, or South America, basic precautions can reduce screwworm risk:

- Avoid unnecessary injuries. Be cautious with sharp tools, maintain awareness of surroundings to avoid falls or accidents.

- Treat any wound immediately. Carry a basic first aid kit including antiseptic.

- Keep wounds clean and covered while healing.

- Avoid swimming or bathing in natural water bodies if you have open wounds.

- Wear protective clothing when working outdoors or in agricultural settings.

- Seek medical care promptly for any wound that doesn't heal normally or shows signs of infection.

If you do sustain an injury while traveling, seek medical attention from a reputable facility rather than attempting home treatment.

If You Live in Border Regions

For people living in southern Texas or other border areas, the current situation suggests higher awareness of wound care:

- Monitor any open wounds closely for signs of infestation (visible larvae, unexplained movement, rapid tissue destruction).

- Be aware of symptoms in livestock. If you raise animals, inspect them regularly for wounds and signs of infestation.

- Report suspected infestations to veterinary authorities immediately.

- Don't attempt to treat suspected screwworm infestations with home remedies or over-the-counter insecticides.

If You Work in Agriculture or Veterinary Medicine

For professionals in these fields, the CDC alert should prompt a review of current practices:

- Ensure wound care protocols are in place for both livestock and human workers who sustain injuries.

- Familiarize yourself with screwworm recognition. Look at images. Understand what larvae look like and how infested wounds appear.

- Know your local reporting procedures. Have contact information for veterinary authorities and public health agencies.

- Ensure proper protective equipment is available and used when handling animals with suspected parasitic infestations.

- Keep medications and supplies readily available for wound management.

FAQ

What exactly is a screwworm and how does it infect people?

The New World Screwworm is a parasitic fly (Cochliomyia hominivorax) that lays eggs in wounds or body openings of warm-blooded animals, including humans. When the eggs hatch, the larvae bore into living tissue using a screw-like motion, feeding on flesh and causing progressive tissue destruction. Infection typically occurs when a person has an open wound and is exposed to screwworm flies, which are found in endemic regions of Central America, Mexico, and increasingly closer to the U.S. border. The key risk factor is an unhealed or contaminated wound in an area where screwworms are present.

How can doctors recognize a screwworm infestation in a patient?

The hallmark signs include visible larvae in a wound, a sensation of movement inside an injury, unexplained tissue destruction that worsens despite proper wound care, and a distinctive wound appearance with progressive tissue loss. The larvae appear as pink or whitish, mobile maggots. Screwworm wounds often smell less foul than typical infected wounds because the larvae prevent anaerobic bacterial growth. Any wound that's not healing normally, especially in patients with recent travel to endemic areas, should raise suspicion. The CDC recommends collecting at least 10 dead larvae in 70% ethanol for laboratory confirmation.

What's the best treatment for screwworm infestation?

Treatment primarily involves physical removal and killing of all larvae. Healthcare providers should remove every larva from the wound and immediately place them in sealed containers of 70% ethanol to kill them and prevent escape. Incomplete removal is treatment failure since even surviving larvae will continue feeding and spreading. Supporting measures include antibiotics for secondary bacterial infection, tetanus prophylaxis if indicated, and proper wound care. In extensive infestations, multiple debridement sessions might be necessary. Self-treatment at home with insecticides or other remedies is dangerous and ineffective.

Why is the screwworm returning to the Americas when it was supposedly eradicated?

The New World Screwworm was eliminated from the United States by 1966 using the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT), which involved releasing hundreds of millions of radiation-sterilized male flies to prevent reproduction in wild populations. Coordinated efforts kept the flies out of the U.S. through the 1970s-2010s by maintaining a biological barrier along the Panama-Costa Rica border through continued sterile fly releases. However, this barrier was breached in 2022 due to lapses in funding, coordination, and increased unregulated cattle movements. Since then, screwworms have spread northward through Central America and Mexico. The lesson is that eradication requires sustained effort, international cooperation, and continued resources.

What should I do if I suspect screwworm infestation in myself, a family member, or an animal?

Do not attempt home treatment. Immediately bring the affected person or animal to a healthcare facility or veterinary clinic. If possible, document the wound with a photograph, but don't delay seeking professional care. Inform healthcare providers immediately of your suspicion. Don't try to use insecticides or other home remedies, as these can be dangerous and don't effectively eliminate larvae. Report suspected cases to public health authorities or veterinary agencies. If you're a healthcare provider and suspect screwworm infestation, contact your state health department and the CDC immediately. The goal is rapid professional treatment and reporting to prevent environmental establishment of the fly.

How likely is it that screwworms will become established in the United States?

The risk is currently low but increasing. Eight active cases in Tamaulipas, Mexico, just 70 miles from the Texas border, represent a warning sign rather than an immediate crisis. The USDA's sterile insect program, releasing 100 million flies weekly in Mexico, should prevent northward spread if maintained. However, the program depends on sustained funding and international cooperation. Livestock movements across the border, while regulated, could potentially transport an infested animal. A single infested animal could theoretically establish a new U.S. population. The CDC's health alert reflects appropriate vigilance without panic. Preparedness is key.

Are there medications that can kill screwworm larvae without removing them?

No effective oral or systemic medications specifically target screwworm larvae. Antibiotics don't work because the larvae aren't bacteria. Topical insecticides have been used historically but are less reliable than mechanical removal and can cause systemic toxicity if absorbed. Even compounds that kill larvae don't prevent tissue damage that's already occurred. Mechanical removal of every larva remains the gold standard treatment. Some topical agents like oils or petroleum jelly can be used as adjuncts to make larvae more visible and less able to move, but they're not primary treatment.

How long does a screwworm infestation last if left untreated?

Untreated screwworm infestations progress rapidly and can become life-threatening within days. In livestock, progression is often dramatic, with animals declining severely within 48-72 hours. In humans, progression is typically slower but still serious. A small wound can become a massive, gaping cavity within days as hundreds of larvae feed continuously. Secondary bacterial infection and sepsis can develop. If larvae migrate to critical areas like the eyes, nasopharynx, or internal organs, permanent disability or death can result. Historical data suggests that untreated human infestations can be fatal if they progress unchecked, though exact mortality rates in humans are unclear. In livestock, untreated infestations are often fatal.

What's the connection between climate change and screwworm spread?

While climate change isn't the primary cause of screwworm re-emergence, it may be a contributing factor. Warmer temperatures expand the geographic range where screwworms can survive and reproduce. The fly's larval development accelerates in warmth, allowing more rapid reproduction. However, the immediate cause of the 2022 breakthrough was the breach of the physical barrier in Panama due to human activity and development, not climate factors. That said, ongoing climate change could make it harder to control screwworms in regions near the equator where temperatures are already optimal for the flies, and could expand the range northward where they might previously have faced temperature barriers to reproduction.

Why is the sterile insect technique considered so effective for screwworm control?

The Sterile Insect Technique is effective because screwworm females mate only once during their 21-day lifespan. Once a female mates with a sterile male, she's rendered reproductive for life, as she carries and uses that male's sperm for all her egg production. By overwhelming wild populations with sterile males, the proportion of matings with infertile males increases exponentially. The population crashes within a few generations as reproduction drops to zero. The technique is species-specific (doesn't harm other insects), environmentally friendly, and has proven remarkably effective. Its main limitation is that it requires sustained effort and massive scale (100 million sterile flies weekly in Mexico), making it expensive to maintain long-term. But when properly resourced, it's nearly perfectly effective.

Conclusion: Vigilance as Public Health Strategy

The CDC's health alert about screwworm flies isn't an overreaction. It's a necessary step in disease surveillance and prevention. Eight active cases in Mexico, located just miles from American territory, represent a genuine threat that demands professional attention and public awareness.

What makes this situation particularly instructive is the historical context. We've been here before. In the 1950s and 1960s, screwworms were a scourge of American agriculture. Scientists and policymakers chose to invest in eradication rather than accept the ongoing losses. That investment paid off spectacularly. By 1966, screwworms were eliminated from the United States. The economic benefits of that eradication have far exceeded the costs of the program.

But success led to complacency. As screwworms disappeared from American consciousness, resources for maintaining barriers and monitoring neighboring countries were sometimes inconsistently funded. The barrier in Panama, which had been so carefully maintained, weakened. By 2022, it had failed entirely.

Now we're in a position where we must actively prevent screwworm re-establishment in the United States rather than passively enjoying eradication. It's more expensive and more difficult than maintaining a barrier that was already functioning. It's a reminder of a fundamental principle in public health: preventing disease is cheaper and easier than containing it after it's been lost.

For healthcare providers, the message is clear. Familiarize yourself with screwworm recognition. If you encounter a wound that doesn't fit the usual patterns—tissue destruction that seems excessive, movement within the wound, visible larvae—consider screwworms in your differential diagnosis. Report suspected cases promptly. Ensure proper specimen handling and submission for confirmation.

For people living in border regions, awareness is key. Understand the risk. Maintain proper wound care. Report suspected infestations in livestock. Support public health and agricultural efforts to control the fly.

For policymakers and public health officials, the screwworm situation illustrates why sustained investment in disease prevention and eradication is essential. The sterile insect program is expensive, but the cost of allowing screwworms to re-establish would be far higher. The money spent on 100 million sterile flies released weekly in Mexico is money well spent, not money wasted.

The screwworm's journey toward the Texas border isn't inevitable. It can be stopped. But stopping it requires recognition of the threat, awareness of what we're trying to prevent, and sustained commitment to a strategy we know works. The CDC's health alert is the first step. What happens next depends on everyone from frontline clinicians to agricultural regulators to policymakers maintaining focus on a threat that doesn't grab headlines but could cause serious harm if allowed to establish itself.

The fight to keep screwworms out of the United States isn't glamorous. But it's essential. And it's one we can win if we maintain vigilance.

Key Takeaways

- Eight active screwworm cases in Tamaulipas, Mexico (70 miles from Texas border) have prompted CDC health alert to U.S. clinicians

- Screwworm larvae bore into living tissue using screw-like motions, causing rapid, severe tissue destruction that can be life-threatening if untreated

- The 1966 eradication from the U.S. was achieved via the Sterile Insect Technique (releasing 100+ million radiation-sterilized males weekly), but barrier breach in 2022 allowed re-invasion

- Clinical recognition requires identifying visible larvae in wounds with progressive tissue destruction, sensations of movement, and reports of larvae visible movement patterns

- Treatment is primarily mechanical removal of all larvae and placement in sealed 70% ethanol containers; no effective oral medications exist for screwworm parasites

![Screwworm Flies Are Invading: What Every Doctor and Pet Owner Needs to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/screwworm-flies-are-invading-what-every-doctor-and-pet-owner/image-1-1768947145996.jpg)