Sharpa's Humanoid Robot with Dexterous Hand: The Future of Autonomous Task Execution

When you walk into a technology showcase, you expect to see impressive robots. But there's a difference between a robot that moves and a robot that actually feels what it's doing. Sharpa's presence at CES 2026 wasn't just another exhibit—it represented a fundamental shift in how we think about robotic dexterity and autonomous manipulation.

The company's booth became an unexpected hub of activity. While other exhibitors showcased static displays or scripted demos, Sharpa's humanoid robot was handling multiple concurrent tasks with a level of finesse that stopped attendees in their tracks. Playing ping-pong matches without human intervention. Dealing blackjack cards with the precision of a casino dealer. Taking selfies with visitors. These weren't pre-programmed sequences or carefully choreographed motions—they were demonstrations of genuine autonomous capability.

But the real star of the show wasn't the humanoid itself. It was Sharpa Wave, the robotic hand powering these demonstrations. This 1:1 scale human hand replica represents years of engineering focused on one critical challenge: how do you give a robot the ability to handle the world the way humans do?

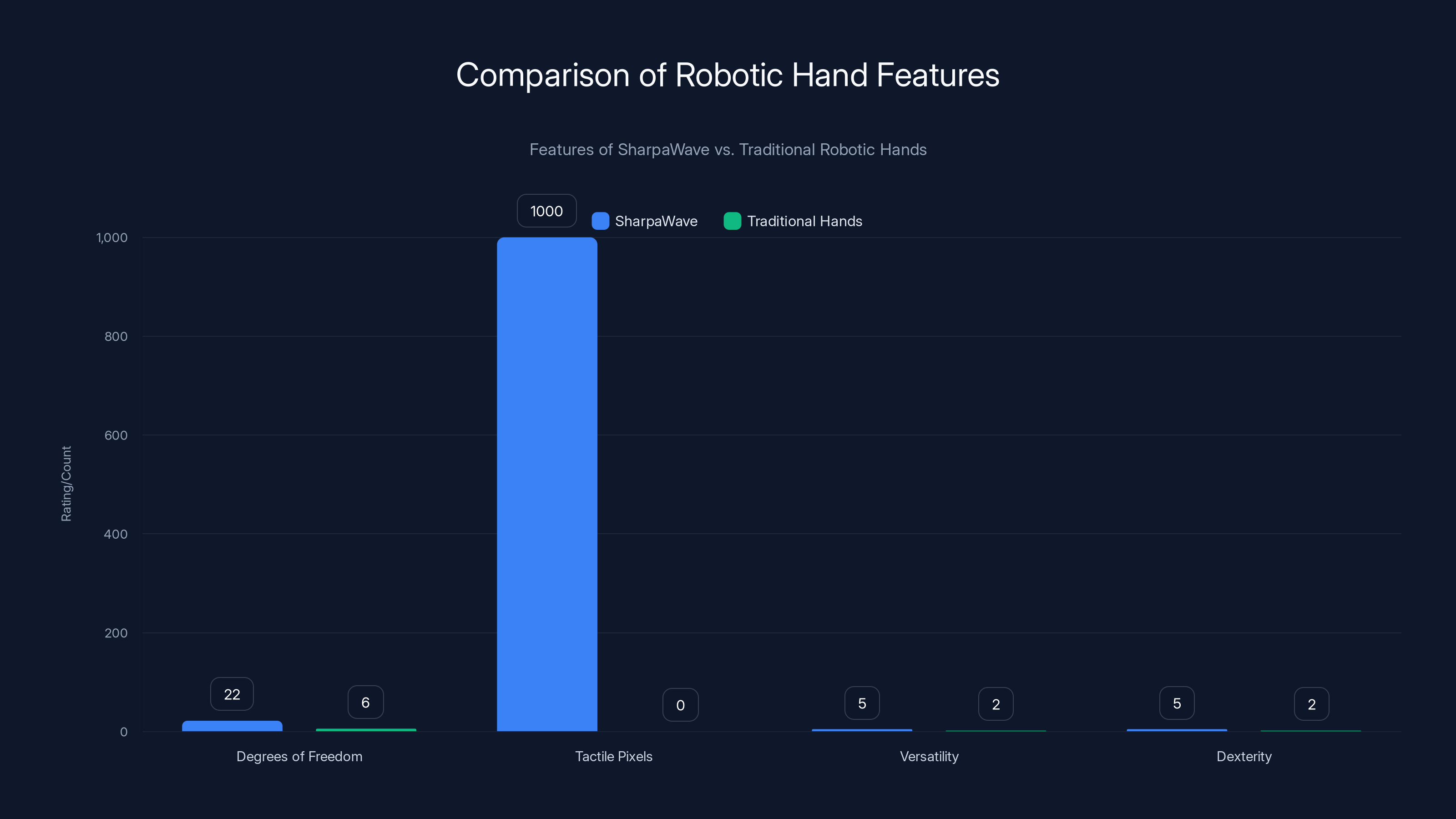

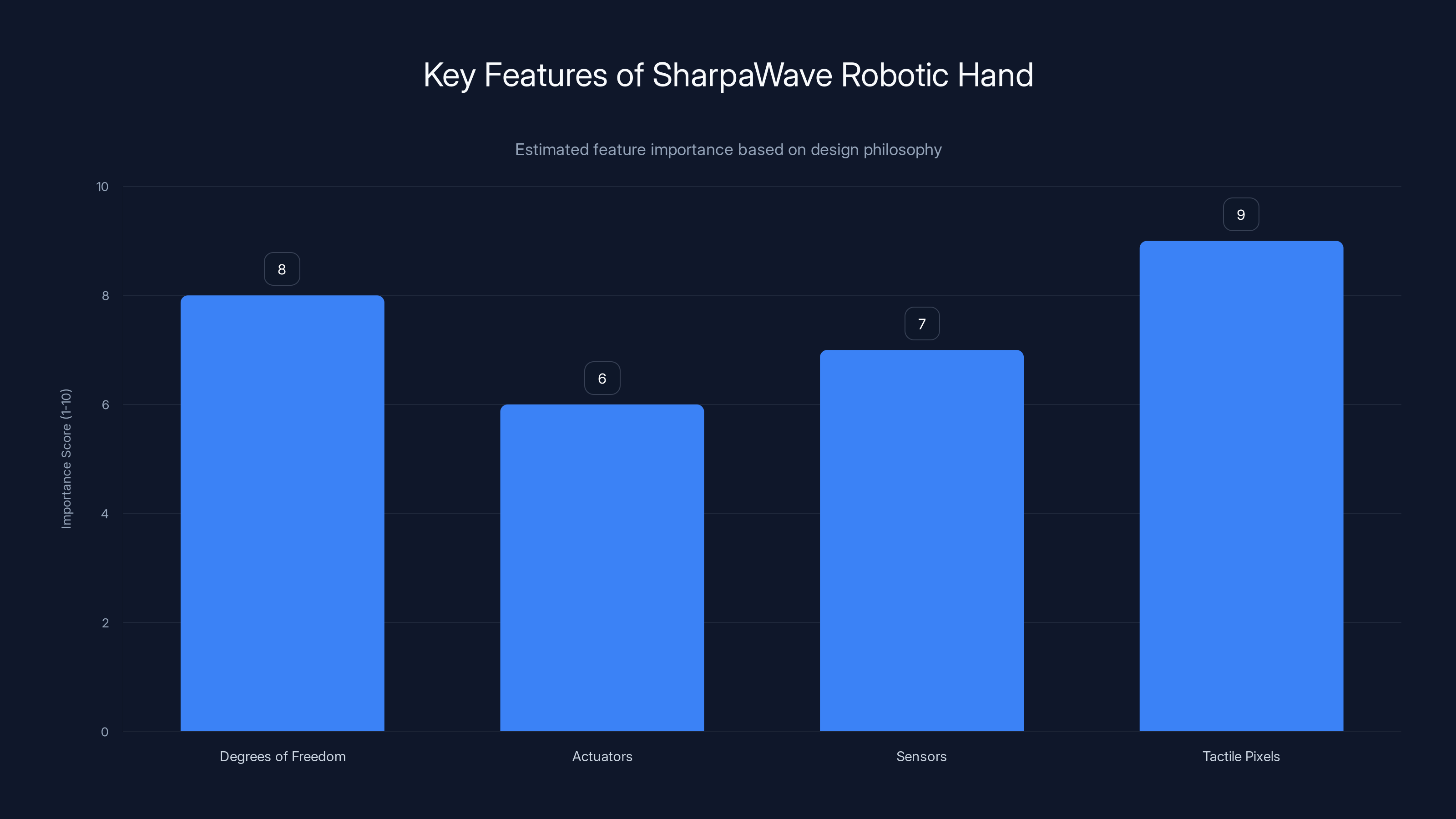

The implications run deep. Current industrial robots excel at repetitive, high-force tasks in controlled environments. But they fail spectacularly when asked to handle delicate objects, adapt to unexpected situations, or perform tasks requiring subtle tactile feedback. Sharpa Wave changes that equation. With 22 active degrees of freedom and over 1,000 tactile pixels embedded in each fingertip, this hand can perceive and manipulate objects with a sensitivity that approaches human capability.

We're witnessing the emergence of a new category of automation: one that doesn't just move things around, but actually understands what it's touching.

TL; DR

- Sharpa's Sharpa Wave hand features 22 degrees of freedom, enabling complex finger movements and object manipulation previously impossible for robots

- Over 1,000 tactile pixels per fingertip provide sensory feedback equivalent to human touch, allowing precise force application

- Autonomous demonstrations included ping-pong play, blackjack dealing, and hand gesture mirroring, proving real-world dexterity

- The technology targets general-purpose automation across industries requiring delicate handling and adaptive responses

- CES 2026 marked a significant milestone in making commercial dexterous robotic hands a practical reality

SharpaWave excels in degrees of freedom and tactile sensing, offering superior versatility and dexterity compared to traditional robotic hands. Estimated data for versatility and dexterity ratings.

The Problem With Robot Hands Today

Let's start with reality. Most industrial robots are terrible at picking things up.

You might think that's an exaggeration, but consider what "picking things up" actually requires. Your hand has about 27 degrees of freedom across multiple joints. You can feel temperature, texture, pressure distribution, and slip angle simultaneously. Your brain processes all that sensory data and adjusts grip force in real-time—constantly, without conscious thought.

A typical industrial robot arm has maybe six degrees of freedom at the wrist. Its gripper is usually a two-fingered claw that operates on an on-off switch. No tactile sensing. No adaptive response. It grips something with the same force whether that something is a steel bearing or an egg.

This limitation exists because dexterous manipulation is genuinely hard. Roboticists have been chasing this problem for decades. Boston Dynamics showed the world what's possible with their bipedal robots, but even their advanced systems struggle with tasks that a five-year-old handles without thinking.

The barriers are both hardware and software. On the hardware side, you need actuators that can provide fine control over individual joints without adding massive weight or complexity. You need sensors in places that human hands don't have sensors, because the robot needs computational assistance where humans rely on intuition. You need structural materials that are strong enough to handle industrial work but light enough to move with speed and precision.

On the software side, you need control algorithms that can translate sensor data into coordinated movement across dozens of joints. You need machine learning models that understand object properties and can predict appropriate grip strategies. You need real-time processing fast enough to respond to unexpected changes without lag.

Most companies solving this problem have picked a path: either build a highly specialized hand optimized for one category of task, or build something more general but accept reduced capability in any single area.

Sharpa took a different approach. They invested in true generalization.

Understanding the Sharpa Wave Design Philosophy

When engineers design a robotic hand, they make trade-offs at every step. More degrees of freedom means more complexity, more power consumption, more weight. More actuators mean more failure points. More sensors mean more processing overhead.

Sharpa's philosophy centers on a core insight: the value isn't in the hand itself, but in what the hand can teach the system about the world.

The Sharpa Wave hand's 22 degrees of freedom represent a careful balance. It's not a replica that matches the full complexity of human hands—that would be engineering overkill for most applications. Instead, it captures the degrees of freedom that matter most for the kinds of dexterous tasks humans actually perform in work settings.

Think of it this way: your pinky finger can probably move in about eight different independent ways (abduction, adduction, flexion across multiple joints, rotation at the wrist). But for 80% of real-world tasks, only three of those movements matter. The Sharpa Wave design identifies which movements matter most and allocates engineering complexity accordingly.

The 1,000+ tactile pixels per fingertip deserve special attention. This isn't just a pressure sensor. Each pixel reports independent data about contact pressure, allowing the system to build a detailed map of how force is distributed across the fingertip surface.

Why does this matter? Imagine you're gripping a playing card. A simple on-off pressure sensor would tell you "yes, there's contact." The tactile pixel array tells you exactly where the contact occurs, how much pressure is applied at each location, and most critically, whether the card is starting to slip.

This last point is crucial. Humans use slip detection constantly—it's what tells you that you need to increase grip force before the object actually falls. Most robots have zero slip detection. They grip something until they're told to let go, with no awareness that something went wrong in between.

Sharpa's approach gives the robot something approaching human intuition. The sensory data flows through the control system in real-time, enabling adjustments that happen faster than you could consciously perceive them.

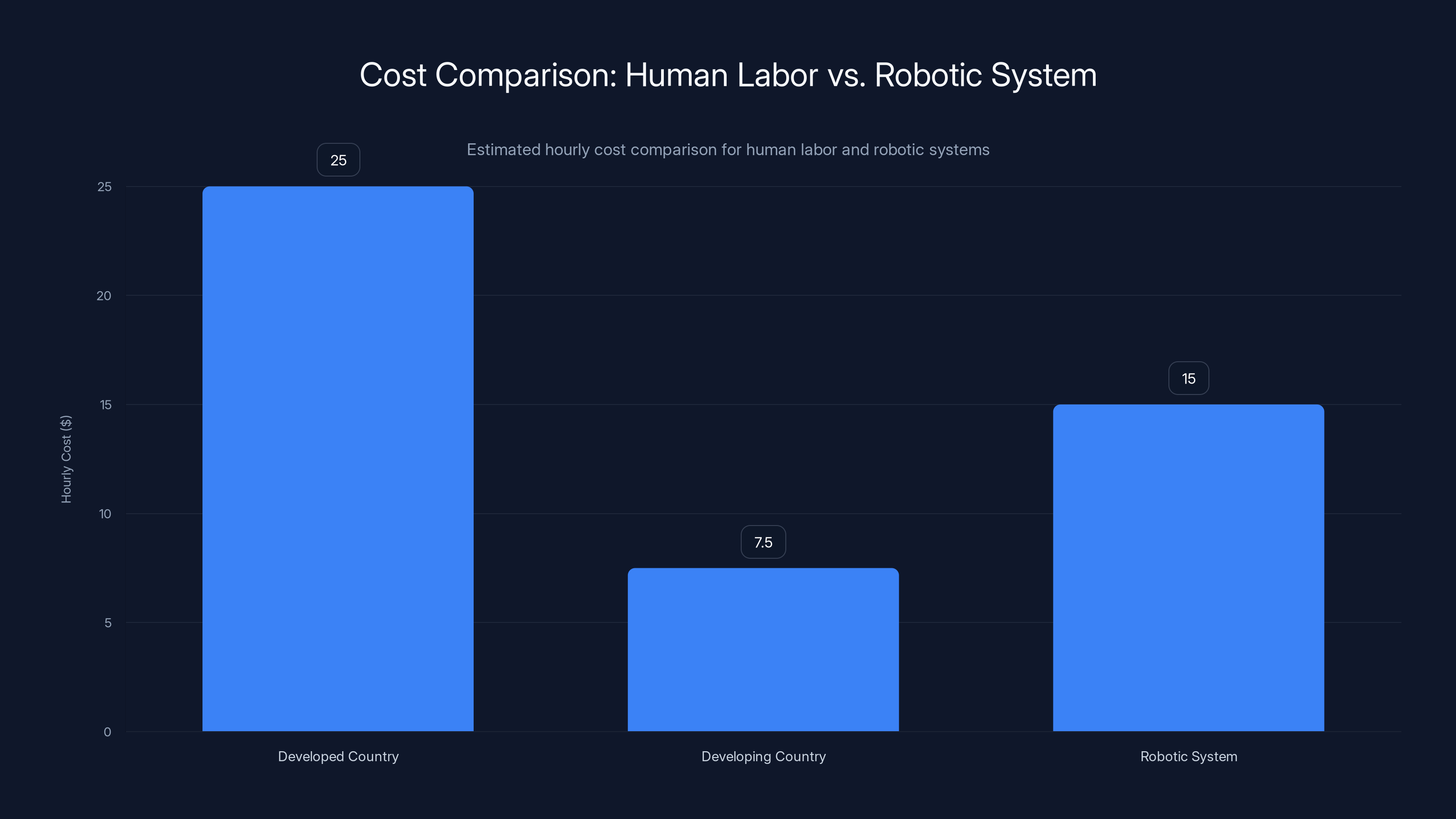

Estimated data shows that robotic systems need to provide value exceeding typical human labor costs to be commercially viable. Estimated data.

The Architecture: How 22 Degrees of Freedom Actually Work

Now, let's dig into the mechanics. Understanding how a system like this actually functions requires thinking about joint hierarchies and control complexity.

A human hand has roughly this structure: the wrist provides up to six degrees of freedom (three rotational, three translational—though in practice, the wrist connection to the forearm constrains some of these). Each finger then has additional joints. The thumb is the most complex, with about nine degrees of freedom from the wrist through the fingertip. The other four fingers each have around seven.

If you tried to build a robot hand that matched this exactly, you'd have 40+ degrees of freedom and a control problem so complex that real-time computation would be nearly impossible.

Sharpa's 22 degrees of freedom suggest a carefully pruned design. Based on the demonstrations—particularly the ping-pong and card-dealing tasks—we can infer the architecture:

Wrist-level control likely accounts for 4-6 degrees of freedom, giving the hand the ability to orient itself in three-dimensional space. Ping-pong requires wrist rotation to adjust paddle angle and meet the ball at the correct angle—without this, the hand would only be able to hit in one plane.

Individual finger control distributes the remaining degrees of freedom. For card dealing, precision is paramount. You need independent control of each finger to separate individual cards from a deck. This probably means each finger has at least 3-4 degrees of freedom (flexion at multiple joints plus abduction/adduction).

The actuators driving this movement are the hidden heroes. They need to be strong enough for industrial tasks but responsive enough for precision work. Modern designs typically use a combination of motor-driven cable systems (where a motor pulls cables attached to joints) and direct joint actuation.

Cable-driven systems have advantages: the motor can be positioned away from the joint (reducing weight at the fingertips), and you can create mechanical advantages through pulley arrangements. But they introduce latency and require constant tension management to prevent slack.

Direct actuation (motors at each joint) provides more responsive control and better precision, but adds weight and complexity.

Most likely, Sharpa Wave uses a hybrid approach: cable-driven actuators for gross finger movement (flexion and extension) with direct actuation or advanced cable systems for fine control (abduction, adduction, and fingertip positioning).

The real breakthrough is probably in the control algorithms. With 22 degrees of freedom, you have an underdetermined system—multiple ways to achieve the same end-effector position. This redundancy is actually valuable: it lets the system choose movement solutions that minimize joint stress or maximize stability. But computing these solutions in real-time requires sophisticated optimization algorithms.

Tactile Sensing: The Thousand-Pixel Revolution

If the hand's degrees of freedom represent the output side of the control equation, the tactile sensing represents the input side. And this is where Sharpa's engineering gets genuinely clever.

Embedding 1,000+ individual tactile pixels in each fingertip creates a sensor density roughly comparable to human fingertips, which have around 100-200 mechanoreceptors per square centimeter. The robot isn't trying to match humans exactly (that would be overengineering), but rather achieve sufficient sensitivity to handle the tasks that matter.

Each tactile pixel is probably a pressure sensor—either capacitive (measuring changes in electrical capacitance as pressure deforms the sensor), resistive (measuring changes in electrical resistance), or piezoelectric (measuring electrical charge generated by mechanical stress).

Capacitive sensors are most likely for this application because they're reliable, relatively inexpensive to manufacture, and work well across a wide pressure range from light touch to significant force.

What's notable is not just the sensor density, but how that data is processed. With 1,000 individual pressure readings, you can't just threshold-check for "is the object slipping?" You need to process a pressure map in real-time.

Here's a simplified version of how this might work:

- Pressure mapping: The 1,000 pixels generate a real-time pressure distribution across the fingertip contact surface

- Slip detection: The algorithm looks for pressure gradients (changes in pressure from pixel to pixel) that indicate the object is moving relative to the fingertip

- Force feedback: The control system receives not just "pressure = X" but a full spatial profile of where that pressure is concentrated

- Adaptive grip: Based on slip detection and force distribution, the system adjusts grip force on individual fingers to prevent slipping without over-gripping

This enables tasks that simple robots cannot perform. Picking up an egg without cracking it isn't just about not squeezing too hard—it's about distributing grip force evenly across the contact surface and detecting the first signs of slip before it becomes catastrophic.

The data pipeline here is significant. If each tactile pixel outputs data even at a modest 100 Hz update rate, that's 100,000 data points per second just from the fingertips. Add in proprioceptive sensors (joint position and angle sensors throughout the arm), accelerometers, gyroscopes, and you're processing tens of thousands of sensor readings per second.

This requires either extremely fast local processing (a microcontroller dedicated to each hand) or clever data compression (only sending significant changes to the central control system, rather than constant streams of pressure data).

Most modern implementations use a hybrid: local processing handles real-time slip detection and basic force feedback (this needs to be truly real-time, under 10 milliseconds of latency), while higher-level task planning and decision-making happens on more powerful processors that can afford slightly more latency (50-100 milliseconds).

The Ping-Pong Demonstrations: Why This Task Matters

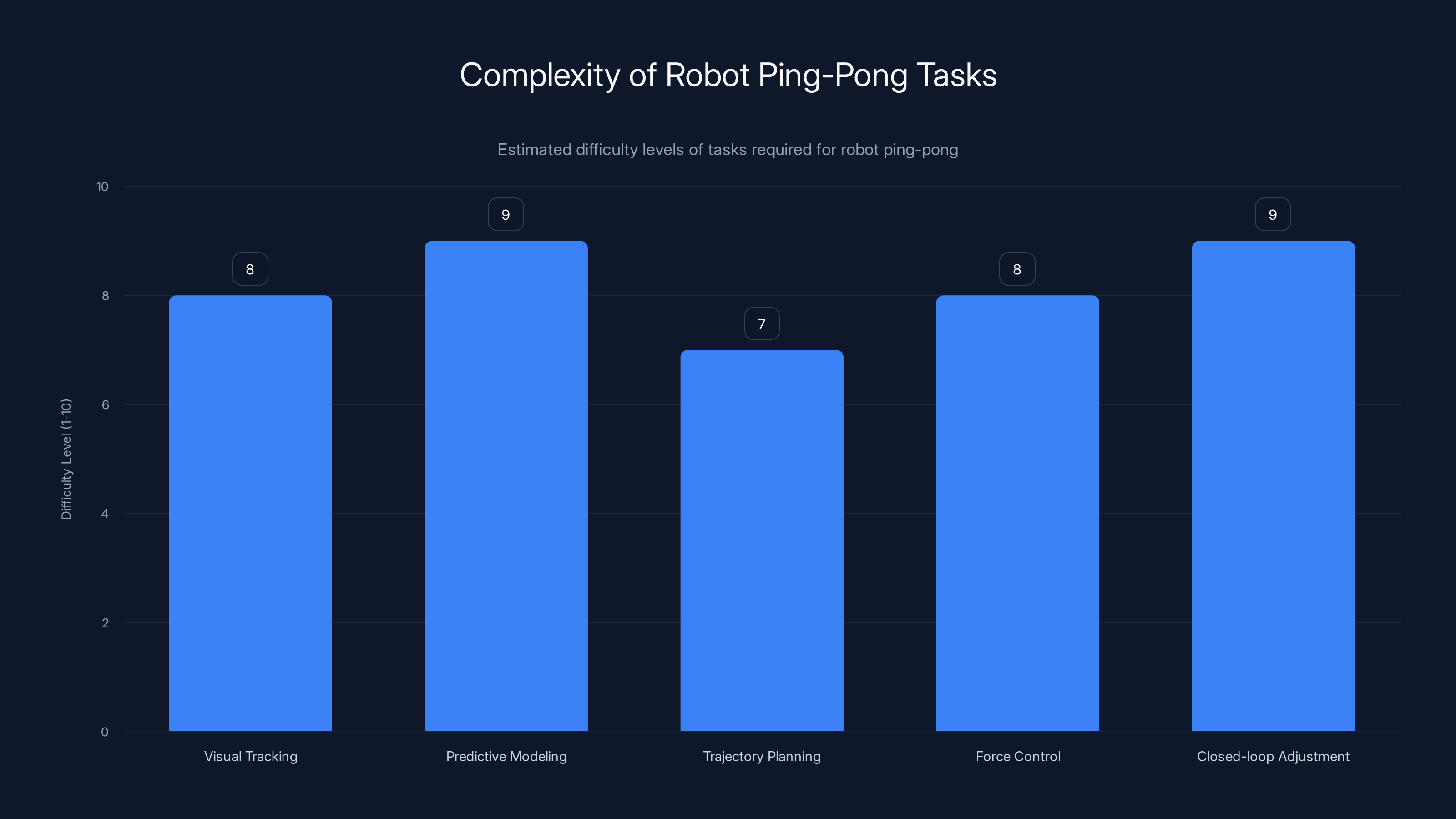

Of all the demonstrations Sharpa showed at CES, the ping-pong playing might seem like the most frivolous. Robots playing games—it's a tech demo trope that goes back decades. But if you understand what ping-pong actually requires, you understand why it's a genuinely impressive benchmark.

Ping-pong is a deceptively complex task. Here's what the robot needs to accomplish:

Visual tracking: The ball is moving at speeds up to 20 mph (for human players; the robot's opponent probably plays more slowly, but still fast). The robotic vision system needs to track the ball's trajectory in three-dimensional space while accounting for the ball's spin (which affects its trajectory in nonlinear ways).

Predictive modeling: The robot can't react to where the ball is; it needs to predict where the ball will be when the paddle reaches that position. This requires estimating the ball's velocity and acceleration, accounting for air resistance, and predicting the paddle's arrival time.

Trajectory planning: Once the system decides where to hit the ball, it needs to plan a motion that moves the paddle to the correct position at the correct time, with the correct orientation. This isn't a simple reach-and-touch motion—the paddle needs to be positioned at a specific angle to direct the ball back across the net.

Force control: Here's where the 22 degrees of freedom and tactile sensing matter. The robot needs to apply sufficient force to hit the ball hard enough to return it across the net, but not so hard that it launches the ball completely out of bounds. The exact force required depends on the paddle angle, the ball's incoming velocity and spin, and where on the paddle the ball makes contact.

Closed-loop adjustment: Even with perfect prediction, contact between paddle and ball is chaotic. The tactile feedback lets the robot sense the impact and adjust its trajectory in milliseconds—tightening the grip if the ball starts to slip, adjusting wrist angle if contact occurs off-center, responding to unexpected spin.

This is why ping-pong is such a common benchmark in robotics research. It requires perceptual intelligence, predictive modeling, real-time control, and adaptive tactile feedback all working in concert.

At CES 2026, Sharpa demonstrated not just that their robot could hit a ping-pong ball, but that it could sustain a rally. This requires consistent execution across multiple cycles—if the prediction algorithm works well for one stroke but then fails on the next serve, the demo falls apart. Sustained rally play suggests the system has robust real-time control and reliable sensory integration.

The performance observed in the booth probably involved a human opponent playing at a reduced difficulty level—most robotic demos do. But even this is nontrivial. The human player wasn't scripted or pre-selected based on their ability to make the robot look good; they were random attendees. This suggests the robot's control system is robust enough to handle variability in human play.

The SharpaWave hand prioritizes tactile pixel data and degrees of freedom, balancing complexity and functionality. Estimated data based on design insights.

Blackjack Dealing: Precision and Dexterity in Sequence

If ping-pong tests real-time responsiveness, blackjack dealing tests something different: sustained precision through a sequence of complex manipulations.

Picking a single card from a deck is already difficult. The dealer needs to separate the target card from the adjacent cards—preventing them from coming up with it—while maintaining enough grip pressure that the card doesn't slip. Too little pressure, and the card stays in the deck. Too much, and adjacent cards come along for the ride.

But dealing blackjack requires this repeatedly, in sequence, under various conditions:

Initial deck state: The deck might be perfectly aligned, or the dealer's previous action might have left cards slightly misaligned. The hand needs to adapt to variable initial conditions.

Selective extraction: The dealer needs to remove specific cards from the deck (dealing hands to multiple players requires extracting from different deck positions). This means the hand needs to navigate to the correct location within a compressed stack, which is harder than reaching for the top card.

Controlled placement: Once extracted, the card must be placed precisely on the table—not thrown, not slid, but placed with controlled motion. This requires the wrist to manage deceleration precisely so the card lands without bouncing or sliding.

Repeated execution: Unlike ping-pong, where a single failure just means losing a rally, card dealing requires multiple successful extractions in sequence. One failed pick ruins the demo.

The tactile sensing becomes critical here. Feeling exactly when a card separates from the deck, detecting if a second card is stuck to the bottom of the target card, sensing whether the card is positioned correctly for placement—all these require distributed touch information across the fingertips.

Why is Sharpa demonstrating card dealing? It's partly showmanship, but there's a serious engineering point: card manipulation requires manipulating thin, flexible objects. Contrast this with industrial tasks like picking up metal parts (stiff, predictable geometry) or gripping cylinders (symmetrical, forgiving). Playing cards are among the worst-case scenario for robot gripping: thin, flexible, easily damaged, requiring high precision.

Successfully dealing blackjack autonomously is a statement: "We can handle your worst-case scenario, which means we can definitely handle your more forgiving industrial tasks."

Hand Gesture Mirroring: Real-Time Imitation as a Trust Signal

One of the demonstrations that caught observers' attention was less about technical capability and more about human psychology: the robot's ability to mirror hand gestures in real-time.

This seems simple until you think about it. The robot needs to:

- See your hand through a camera

- Detect which fingers are extended and which are folded

- Recognize the overall hand pose in three dimensions

- Plan motions that recreate that pose

- Execute the plan with enough speed that you see near-real-time imitation

The hand gesture mirroring serves an important function beyond technical demonstration: it builds intuitive trust. When you see a robot copy your hand motion, your brain interprets it as understanding. It's why robots that move anthropomorphically feel more intelligent than ones that move in mechanical, alien ways.

From an engineering perspective, this demo tests computer vision (pose detection), real-time motion planning, and execution speed. According to the article, the mirroring was "mostly right"—a refreshingly honest assessment that suggests the system works well but isn't perfect.

That honesty is important. Perfect imitation would actually be less credible; it would suggest either scripting or superhuman capability. Mostly-correct imitation that occasionally misses a finger position feels real.

The gesture mirroring also serves as a diagnostic tool for engineers. If the imitation fails in specific ways—always getting a particular finger wrong, struggling with fast motion, losing track during complex gestures—that tells you something about where the system's weaknesses are.

The General-Purpose Promise: Can One Hand Do Everything?

Here's the fundamental claim Sharpa is making, and it's one that deserves scrutiny: one robotic hand design can handle a wide range of different tasks without major modifications or retraining.

This is genuinely hard. Industrial robotics has traditionally succeeded by specializing: robotic arms for welding are optimized for holding a welding torch and making precise movements in constrained spaces. Grippers for assembly lines are optimized for speed and repetition on similar objects. Surgical robotic arms are optimized for stability and precision in delicate manipulation.

Generalization means accepting trade-offs. The hand that can gently manipulate a playing card probably isn't optimized for applying maximum force for a heavy-duty industrial task. The fingers that provide precision might sacrifice speed.

But here's the insight: most real-world tasks don't require single-point optimization. They require competence across a range of conditions. A manufacturing facility doesn't have forty different assembly tasks so specialized that each needs a custom robot hand. Usually, there are variations—different part sizes, different assembly sequences, different orientations—but the fundamental capabilities needed overlap considerably.

Sharpa's strategy is to build a hand capable enough that it can handle this variation with reprogramming, not re-engineering. That's actually valuable.

The demonstrations at CES support this. Ping-pong requires speed and dynamic response. Card dealing requires precision and delicate touch. Selfie taking requires something entirely different—gentle positioning for the camera while maintaining balance.

Successfully transitioning between these tasks autonomously suggests the hand's versatility is real, not theoretical.

The chart illustrates the estimated difficulty levels of various tasks involved in robot ping-pong. Predictive modeling and closed-loop adjustment are particularly challenging due to the need for real-time processing and adaptation. Estimated data.

Real-World Applications: Beyond the Demo Booth

When technology companies demo at shows, there's always the question: what's this actually useful for?

For Sharpa, the applications fall into several categories:

Logistics and materials handling: Warehouse automation currently relies on large-scale conveyors and relatively simple gripper arms. But many tasks still require human workers because the parts are too delicate, too varied, or too irregular for conventional automation. A hand that can manipulate delicate electronics components, adaptively grip objects of different sizes and materials, and work with reasonable speed could address significant labor shortages in logistics.

Manufacturing and assembly: Similar dynamics apply. Labor costs and availability are major factors limiting automation adoption in assembly operations. A versatile robotic hand could be retrofitted onto existing arm platforms to expand their capabilities.

Healthcare and hospitality: Sharpa's demonstrations hint at an emerging market. A humanoid robot with dexterous hands could perform tasks in hospitality settings (dealing games, handling delicate items), healthcare support (assisting with physical tasks), or customer-facing roles where a more human-like appearance and capability create better user experience.

Research and education: Dexterous robotic hands are valuable platforms for studying manipulation, control theory, and human-robot interaction. Universities and research labs will likely be among the earliest customers.

The economics matter, though. General-purpose robotic hands are expensive to develop and manufacture. They need to justify their cost through either higher prices (limiting adoption to high-value applications) or high volume (which requires proving the market exists).

Sharpa's presence at CES suggests they're pursuing the proven-market strategy: get the technology working demonstrably, generate interest and awareness, then scale manufacturing.

That's not a criticism of Sharpa. It's just acknowledging that they're attacking one of the hardest problems in engineering. Creating something useful and economically viable that can actually compete with human workers in dexterity-intensive tasks is a genuine achievement.

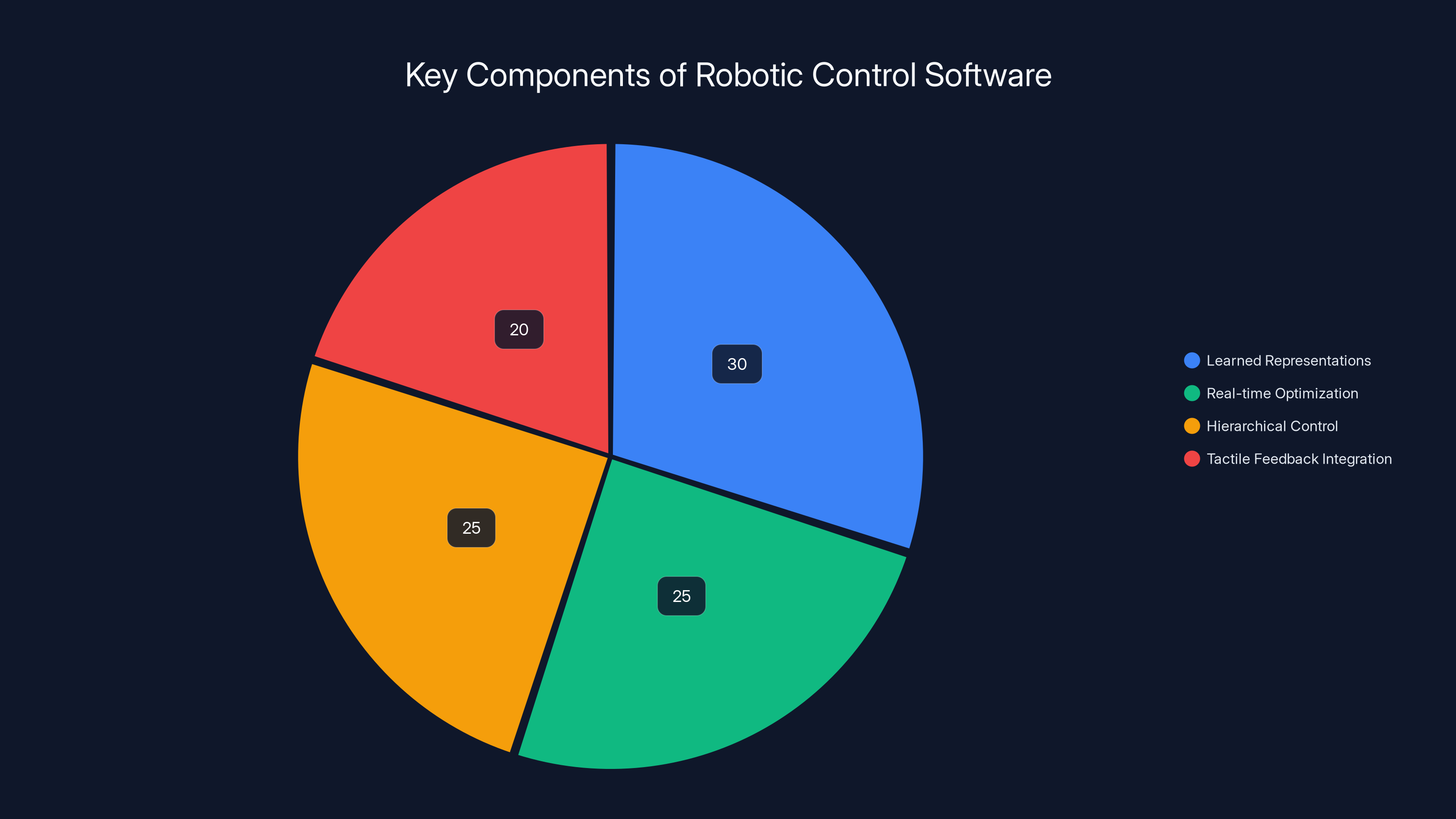

The Control Software: Making Coordination Possible

Despite all the emphasis on hardware specifications—22 degrees of freedom, 1,000 tactile pixels—the real magic is in the software.

Controlling 22 degrees of freedom simultaneously in real-time is a problem in inverse kinematics (the mathematical challenge of determining what joint angles will achieve a desired hand position) combined with trajectory planning (figuring out the fastest or most efficient path to get from current state to desired state).

With 22 degrees of freedom, the hand is over-actuated—there are multiple ways to achieve any given position. Some solutions are better than others depending on context. Reaching for a high object might be better achieved by extending primarily through the shoulder and elbow rather than the wrist (because it's more stable). Reaching to the side might be better with different joint angles.

The software probably uses a combination of approaches:

Learned representations: Deep learning models trained on manipulation data can learn efficient strategies for common tasks. These models might predict joint angles from a desired hand position, or learn task-specific motions from demonstration.

Real-time optimization: Even with learned representations, the system needs to adapt to real-world conditions. Optimization-based control can compute adjusted trajectories in real-time based on sensor feedback, incorporating constraints like avoiding self-collision, managing joint limits, and responding to unexpected contact.

Hierarchical control: The system probably operates at multiple levels of abstraction. High-level task planning ("pick up this card") gets decomposed into mid-level motions ("position hand above card") which get decomposed into low-level joint commands executed with real-time feedback control.

The integration of tactile feedback into this control architecture is nontrivial. You can't just treat tactile data as another sensor stream and feed it into the control system. You need tactile information to change what the system is trying to accomplish mid-execution.

Example: You're gripping a card, and the tactile sensors detect slip on one side of your grip. The high-level goal is still "hold the card," but the low-level control needs to adjust finger force on that side to prevent the slip. This happens in milliseconds, with no need for high-level intervention.

Implementing this requires careful separation of concerns in the control architecture:

- Perception layer: Processes raw sensor data and produces meaningful features (slip detected, contact pressure distribution, hand pose)

- Control layer: Runs real-time servos that execute finger commands and respond to immediate sensory feedback

- Execution layer: Tracks higher-level task progress and adjusts the control layer's objectives

- Planning layer: Decides what task to execute next and generates the sequence of sub-goals

Sharpa's ability to switch rapidly between different tasks (ping-pong to blackjack dealing to gesture mirroring) suggests robust compartmentalization between these layers. You don't want ping-pong control parameters active when you're supposed to be delicately dealing cards.

Comparing to Competing Approaches in Dexterous Manipulation

Sharpa isn't working in a vacuum. Several research labs and companies are pursuing dexterous robotic hands with different strategies.

Shadow Hand and similar academic projects prioritize matching human hand complexity as closely as possible, often resulting in 20+ degrees of freedom but with significant hardware complexity and cost.

Anthropomorphic designs build hands that visually resemble human hands, which aids in intuitive understanding but doesn't necessarily improve functional capability.

Minimalist approaches focus on essential capabilities with fewer degrees of freedom, sacrificing versatility for simplicity and cost.

Soft robotics uses compliant materials that adapt to objects being handled, trading precision for adaptability.

Sharpa's approach—22 degrees of freedom optimized for the most functionally important movements, combined with dense tactile sensing—seems to be a pragmatic middle ground. Not as minimal as some industrial approaches, not as biomimetic as some academic projects, but targeted at the task requirements that actually matter.

The 1:1 scale (matching human hand size) is another interesting choice. Smaller hands (like those on Boston Dynamics robots) are lighter and faster but harder for humans to interact with intuitively. Larger hands (sometimes used for industrial applications) provide more gripping strength but less dexterity. Matching human scale suggests Sharpa is optimizing for general-purpose use in human-designed environments.

Estimated data suggests that learned representations and real-time optimization are key focus areas in robotic control software, each comprising around 25-30% of the effort, with hierarchical control and tactile feedback integration also playing significant roles.

The Tactile Sensing Advantage: Why 1,000 Pixels Matter

Let's take a deeper dive into why dense tactile sensing is such a significant advantage, because this isn't obvious to non-specialists.

Consider a simple task: picking up an egg without cracking it. A human does this without thinking. We apply pressure gradually, feel the egg's resistance to deformation, and adjust grip force to keep it safely gripped but not compressed.

A robot without tactile sensing can't do this. It can calculate the minimum force needed to prevent slipping based on the egg's weight and friction coefficient (which it would need to know beforehand), but if it's wrong, it won't know until after the shell cracks.

A robot with simple pressure sensing (just one sensor at each fingertip) can detect whether contact has occurred and how much force is being applied, but not where on the finger the contact is occurring. An egg contacts different parts of each fingertip as you adjust your grip, and force distribution matters.

With 1,000 tactile pixels per fingertip, the robot builds a detailed map of contact pressure across the surface. This reveals whether force is distributed evenly (good—the egg isn't concentrated on one spot) or concentrated (bad—you're creating a stress concentration). The algorithms can detect incipient cracking (the egg deforms slightly non-uniformly, which shows up in the pressure distribution) before failure occurs.

This is why tactile sensing density matters. More pixels means more information, which enables earlier detection of problems and more sophisticated adaptive control.

Of course, more sensors means more computational overhead. Processing 1,000 pressure readings at high frequency requires either significant processing power or clever algorithms that extract just the important features (pressure gradients, peak pressure locations, area of contact) without processing every raw pixel.

Sharpa's engineering here is probably doing feature extraction locally (probably on each hand) to reduce the data volume transmitted to central control. Raw tactile data from all 1,000 pixels might be gigabits per second. Processed features ("slip detected on finger 3, gradient suggests leftward motion") is just a few kilobytes per second.

Real-World Constraints: What the Demo Doesn't Show

CES demos are carefully controlled. The playing cards are probably a specific type (consistent thickness, finish, and weight). The ping-pong opponent is probably playing at a level optimized to make the robot look good without being so easy that it seems trivial. The lighting is probably optimized for the vision system.

Real-world deployment faces different constraints:

Variability: In manufacturing, parts vary in size, weight, material properties, and condition. The hand that works perfectly on brand-new cards struggles with worn ones. The hand that grips heavy parts doesn't have the delicacy for light ones.

Unstructured environments: CES booths are clean and controlled. Real factories and warehouses are messy. Parts are often piled haphazardly, dust accumulates on sensors, lighting is variable.

Reliability requirements: A demo that fails is embarrassing. A production system that fails is expensive. The hand needs to work reliably thousands of times per day for weeks at a time.

Cost realities: The Sharpa Wave hand is impressive engineering, which means it's expensive. For it to be adopted in commercial applications, the cost needs to be justified by the labor hours it saves or the tasks it enables that wouldn't be possible otherwise.

Maintenance and support: Robotic systems need maintenance. The hand needs to be designed for easy cleaning, part replacement, and calibration.

These constraints aren't criticisms of Sharpa—every emerging technology faces them. They're just the gap between impressive demos and scalable products.

Future Directions: What Comes Next

Assuming Sharpa continues developing this technology, several logical next steps seem probable:

Bilateral hands: Humans have two hands that work together. Current demos show single-hand operation. Adding a second hand with coordinated control would expand the task space dramatically. Two-handed assembly tasks are common in manufacturing.

Full humanoid integration: The company showed a "humanoid from the waist up." Eventually, they'll likely integrate these hands into fully mobile humanoids for applications requiring mobility plus dexterity.

Application-specific variants: The current hand is general-purpose, but there's probably a market for variants optimized for specific tasks. A version with stronger joints for heavy gripping. A version with higher-frequency tactile sensing for delicate work. A version with integrated tools (like welding attachments).

Modular composition: Rather than building completely custom hands for different applications, the industry might move toward modular components. Standard actuators, connectors, and sensor packages that can be assembled into different configurations.

Soft robotics integration: The current design is rigid with actuators. Integrating soft robotics—compliant materials that passively adapt to objects—might improve safety and dexterity for some applications.

Closed-loop optimization: Current control is probably based on models and learned behaviors. Future systems might use real-time machine learning to continuously improve their performance at specific tasks through experience.

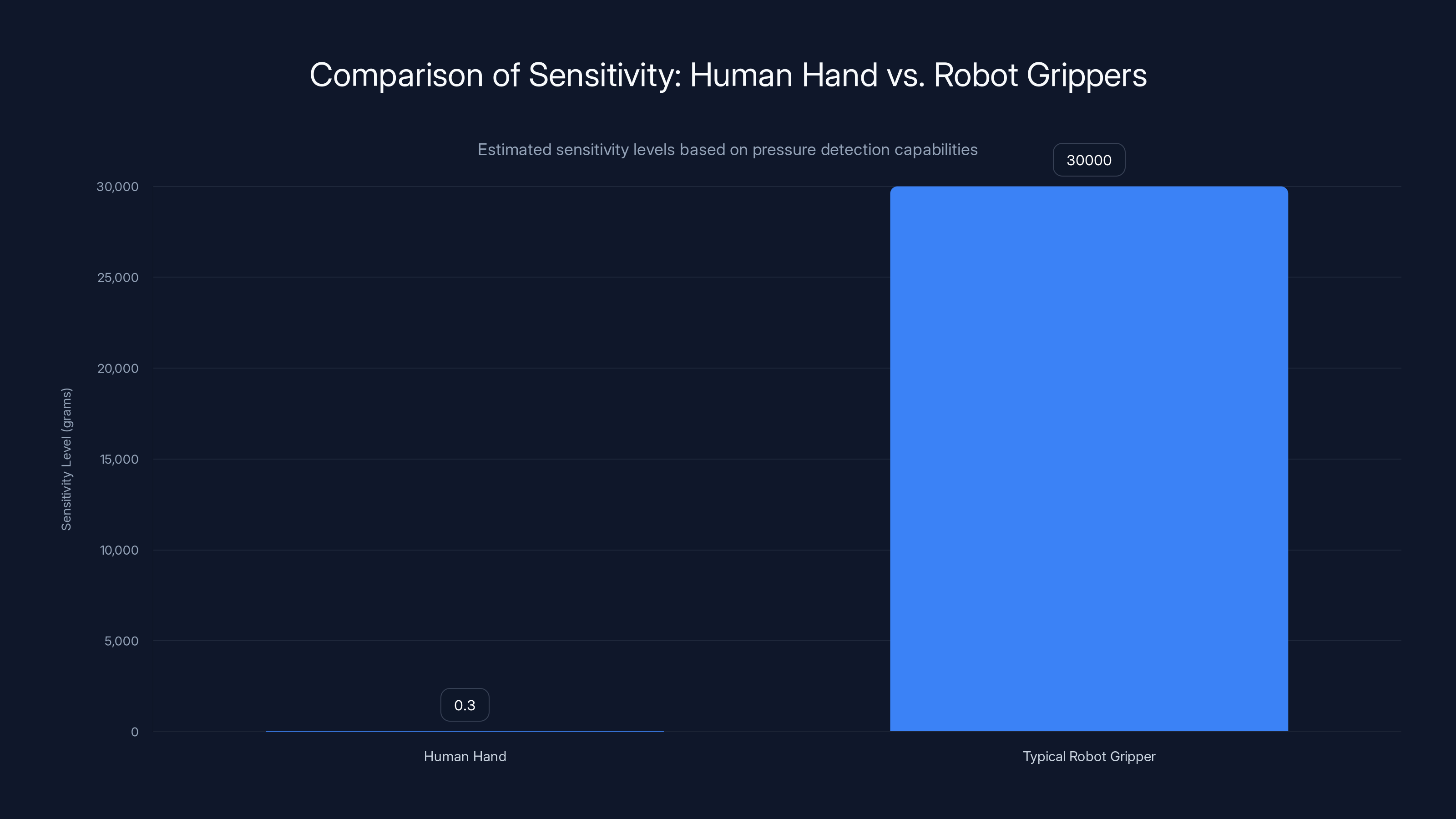

Human hands can detect pressure variations as small as 0.3 grams, whereas typical robot grippers are about 100,000 times less sensitive, lacking tactile sensing capabilities.

The Bigger Picture: Dexterity as the Automation Frontier

We tend to think about automation as being solved. We have factories full of robots, warehouses with conveyor systems, and AI systems doing cognitive work.

But there's a massive gap in what's actually automated. High-volume, repetitive, parts-are-identical tasks: automated. Complex, variable, requires human judgment tasks: mostly still human labor.

Dexterous manipulation sits in the middle. It's not quite "requires human judgment," but it's certainly more variable and complex than today's typical industrial automation handles well.

Sharpa's technology attacks this middle ground. If dexterous robotic hands become economically viable and reliable enough for commercial adoption, it would unlock automation opportunities across industries:

- Electronics assembly where components are delicate

- Package handling where items vary in size and fragility

- Healthcare tasks requiring fine motor control

- Food preparation and serving

- Consumer goods manufacturing

- Logistics for e-commerce where item variety is extreme

The magnitude of potential impact depends on whether this technology can transition from impressive demos to reliable, cost-effective production systems. Sharpa's CES presence suggests they believe they're on that path. Whether they successfully complete it will be apparent within a few years as the company moves from research demonstrations to commercial deployments.

Integration Opportunities: Where Dexterous Hands Meet Production

One aspect worth considering is how dexterous hands integrate with existing robotic infrastructure. Most industrial facilities have invested in robot arms—Universal Robots, KUKA, ABB systems, and others.

A dexterous hand only adds value if it can be attached to and controlled alongside these existing arms. This means standardized interfaces (mechanical mounting, electrical connectors, software integration protocols).

Sharpа hasn't publicly detailed their integration strategy, but successful commercialization probably requires:

Standard mounting: The hand needs to attach to common robot arm flanges (probably ISO 9409 quick-change plates, the industrial standard).

Control integration: The hand's control system needs to communicate with the arm's control system. This might be direct integration (hand controller talks directly to arm controller) or indirect (both controlled by a higher-level system).

Programming APIs: System integrators need straightforward ways to program coordinated arm-and-hand motions without needing to understand low-level control details.

Sensor integration: The arm needs to know what the hand's sensors are detecting so it can adjust overall strategy (if the hand detects something is slipping, maybe the arm needs to reposition, not just apply more grip force).

Getting these integrations right is tedious engineering work that doesn't show up in CES demos. But it's critical for commercial success.

The Economics: Can Dexterous Hands Be Commercially Viable?

This question ultimately determines whether Sharpa succeeds as a company.

A human worker in a developed country costs roughly

A robotic system needs to provide value exceeding this labor cost. This requires either:

- Operating much faster than humans (producing more output per hour)

- Operating for many hours without breaks (shift work that humans can't sustain)

- Performing tasks humans can't or won't do (hazardous environments, extreme precision)

- Providing consistency that reduces defects and waste

Dexterous manipulation is hard to automate cost-effectively, which is why it remains mostly human labor. For Sharpa's hands to succeed commercially, they need to hit one or more of these value propositions.

The capital cost of a dexterous hand system is probably substantial—at minimum $50,000-100,000 for just the hand, controller, and integration, plus the robot arm itself, plus system integration and programming. For this to make sense economically, the task being automated needs to justify 2-3 years of capital payback, which means either very high labor costs or very high throughput.

There's probably a sweet spot: medium-volume manufacturing or logistics tasks with moderate labor costs, where automating even 50% of the work with dexterous hands provides meaningful economics.

Sharpa's strategy likely involves targeting these sweet spots early—specific industries and applications where the economics are favorable—then leveraging success in those niches to build volume and drive down costs.

The Research Implications: Understanding Manipulation Through Engineering

Beyond commercial applications, Sharpa's hand design has value for fundamental research in robotics and control theory.

The field still doesn't fully understand optimal strategies for dexterous manipulation. How many degrees of freedom are actually necessary? How dense does tactile sensing need to be? What control architectures best balance real-time responsiveness with planning sophistication?

Sharpа's public demonstrations generate valuable data. Computer vision researchers can study how the hand performs gesture recognition. Control theorists can analyze how the system handles real-time adjustment. Machine learning researchers can investigate how learned behaviors compare to traditional control approaches.

This knowledge transfer happens both ways. Academic research into deep learning, optimal control, and sensor design eventually informs commercial products. Commercial products drive researchers to tackle practical challenges they might not encounter in academic settings.

CES serves as a forum where this exchange of ideas happens. Sharpa shares their engineering work. Other companies and researchers see what's possible and push the boundaries further.

Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Building Dexterous Hands?

Sharpa isn't alone in this space, though the competition is limited because it's difficult and expensive.

Shadow Hand (developed at the University of Leeds and commercialized) has been around longer and has genuine expertise in high-DOF hand design. They've focused on research applications and are now expanding toward commercial robotics.

Boston Dynamics has incorporated dexterous manipulation into their humanoid robots, though their approach emphasizes whole-body coordination rather than hand specialization.

Various startups are working on different approaches—some focusing on soft robotics, others on modular designs, others on specialized hands for specific tasks.

The competitive advantage Sharpa seems to be pursuing is breadth: a single hand design that works well across many applications, rather than specialized hands or research platforms.

That's a different competitive strategy than Shadow Hand (focused on research/education) or Boston Dynamics (focused on full humanoid systems). Whether it succeeds depends on whether they can execute the commercialization challenge better than competitors.

Lessons from CES 2026: What This Moment Tells Us

Sharpa's CES presence is significant for what it tells us about the state of robotics development:

-

Dexterous manipulation is becoming practical enough to demo: Five years ago, showing a robot dealing cards reliably would be extraordinary. Now it's a booth demo. This suggests the technology is approaching maturity.

-

General-purpose robotic hands are a realistic goal: The variety of tasks demonstrated (ping-pong, blackjack, gestures) shows enough versatility to suggest one platform can handle multiple tasks.

-

Companies are betting on commercialization: Sharpa invested in a CES booth, which costs money and attracts investor and customer attention. This suggests they believe they're close to commercial viability.

-

Consumer and enterprise audiences are interested: Large numbers of attendees stopped at the booth, took videos, asked questions. There's clearly market appetite for this technology.

-

The barrier to adoption is probably not capability anymore, but cost and integration: The hand can do impressive things. The remaining question is whether it can do them economically.

FAQ

What is Sharpa Wave and what makes it different from other robotic hands?

Sharpa Wave is a 1:1 scale robotic hand developed by Sharpa that features 22 active degrees of freedom and over 1,000 tactile pixels per fingertip. It differs from other robotic hands through its combination of multiple joints per finger enabling complex movements, dense tactile sensing that mimics human touch sensitivity, and demonstrated versatility across diverse tasks without requiring physical modifications. Most industrial robotic hands use simple two-fingered grippers without tactile feedback, while Sharpa Wave enables nuanced manipulation more akin to human dexterity.

How do 22 degrees of freedom translate into practical capabilities?

The 22 degrees of freedom are distributed across the wrist and individual fingers, enabling independent control of wrist orientation and rotation, plus multiple joints in each finger for flexion, extension, and abduction (spreading). This enables complex movements like picking individual cards from a deck, adjusting grip angle mid-task, and rotating objects in hand—tasks that traditional robot arms with 6 degrees of freedom cannot perform. The redundancy (multiple ways to achieve the same hand position) provides flexibility in movement strategies based on task requirements.

What exactly are tactile pixels and why does a robotic hand need 1,000 of them?

Tactile pixels are individual pressure sensors embedded in the fingertips that detect contact pressure at that specific location. With 1,000 pixels across the fingertip surface, the system creates a pressure map rather than just knowing "there is pressure." This enables detecting slip (which shows up as pressure gradients), distributing grip force evenly (detecting concentration that could damage delicate objects), and adapting to unexpected contact changes in real-time. Human fingertips have comparable tactile density, and this enables humans to perform delicate tasks reliably.

What tasks can Sharpa's humanoid robot perform autonomously?

Demonstrated tasks include playing ping-pong at rally-sustaining levels, dealing individual playing cards from a deck with precision, mirroring hand gestures in real-time, and taking selfies with visitors. These demonstrations span dynamic tasks (ping-pong), precision manipulation (card dealing), and coordination (gesture mirroring). The variety suggests the platform's versatility across different task types.

What are the real-world applications for dexterous robotic hands like Sharpa Wave?

Potential applications include logistics and warehouse automation (handling delicate electronics or varied package sizes), manufacturing assembly (placing delicate components), healthcare support (assisting with tasks requiring fine motor control), hospitality (serving drinks or handling objects in customer-facing roles), and light manufacturing where task variability currently prevents full automation. Any application requiring adaptation to variable objects or delicate handling could potentially benefit.

How does the robot determine how much force to apply when gripping objects?

The system uses tactile feedback from the 1,000 pressure-sensing pixels to monitor grip force and slip detection. The control system continuously adjusts finger pressure based on feedback—increasing force if slip is detected, decreasing if contact pressure becomes excessive. This closed-loop approach enables the system to apply just enough force for the task (not cracking eggs, preventing cards from slipping) without manual force pre-programming.

What is the difference between Sharpa's approach and other dexterous hand projects?

Sharpa's approach emphasizes practical versatility with 22 degrees of freedom optimized for functionally important movements (rather than attempting to replicate all 27 human hand DOF), combines this with dense tactile sensing for adaptive control, uses human-scale sizing for intuitive interaction, and demonstrates general-purpose capability across multiple task types. This contrasts with approaches that either focus on maximum biomimicry (trying to exactly replicate human hands) or minimalist designs (using fewer DOF for simplicity and cost).

What are the barriers to commercial adoption of dexterous robotic hands?

The primary barriers are capital cost (systems are expensive, requiring significant investment payback periods), integration complexity (connecting to existing manufacturing systems requires engineering work), reliability requirements (production systems must work consistently thousands of times daily), and performance in unstructured environments (real factories are messier than CES booths). Additionally, tasks need to justify automation economically, meaning either high labor costs, high throughput requirements, or tasks humans can't perform safely.

How does control software enable coordinated movement across 22 degrees of freedom?

The control software likely uses hierarchical approaches: high-level task planning ("pick up this card") decomposes into mid-level motions ("position hand above card") which decompose into low-level joint commands. Real-time feedback from tactile and proprioceptive sensors enables mid-execution adjustments. Inverse kinematics algorithms compute which joint angles achieve desired hand positions. Machine learning models may provide efficient solutions based on learned manipulation strategies. This allows the system to coordinate complex movements while remaining responsive to real-time sensory data.

What does the future of dexterous robotic hands likely look like?

Future developments probably include bilateral hands (two coordinated hands), integration into fully mobile humanoid robots, application-specific variants optimized for particular tasks (heavy gripping vs. delicate work), modular designs allowing customization from standard components, increased incorporation of soft robotics for passive adaptation, and continuous learning systems that improve performance through experience. Broader adoption depends on moving from impressive demos to cost-effective, reliable production systems that provide clear economic value in real-world settings.

The emergence of sophisticated dexterous robotic hands represents more than just another incremental improvement in robotics. It signals the beginning of automation's expansion into the vast middle ground of tasks that require flexibility, adaptation, and sensitivity. Sharpa's demonstrations at CES 2026 suggest that this moment has arrived.

The question now isn't whether dexterous robotic hands are possible—clearly they are. The question is whether they'll become economically viable at scale. That answer will determine whether the next decade brings genuine transformation to manufacturing, logistics, and service industries, or whether dexterous manipulation remains a specialized research capability.

Based on what was on display, Sharpa has built something genuinely impressive. Whether they can translate that into a successful commercial product remains to be seen. But the technology is undeniably real, the demonstrations are convincing, and the market opportunity is substantial.

For robotics enthusiasts and industry professionals, CES 2026 served as a reminder: the future where robots can do more than just repeat the same motion thousands of times isn't theoretical anymore. It's in a booth, dealing blackjack, waiting to see if the world is ready for it.

Key Takeaways

- SharpaWave features 22 degrees of freedom optimized for functional manipulation tasks, significantly expanding capability beyond traditional industrial robot grippers

- 1,000+ tactile pixels per fingertip enable adaptive grip force, slip detection, and real-time response to unexpected contact conditions

- Demonstrated autonomous capability across diverse tasks (ping-pong, card dealing, gesture mirroring) suggests genuine generalization rather than specialized programming

- Commercial success depends on moving from impressive CES demonstrations to cost-effective, reliable production systems that provide clear economic value

- Technology addresses significant market gap between simple industrial automation and human-level dexterity, opening possibilities for previously impossible automation

Related Articles

- CES 2026: The Biggest Tech Stories and Innovations [2025]

- CES 2026 Day 3: Standout Tech That Defines Innovation [2026]

- CES 2026: Complete Guide to Tech's Biggest Innovations

- CES 2026 Bodily Fluids Health Tech: The Metabolism Tracking Revolution [2025]

- CES 2026 Tech Trends: Complete Analysis & Future Predictions

- Gigabyte's OLED Monitor ABL Fix Could Change Everything [2025]

![Sharpa's Humanoid Robot with Dexterous Hand: The Future of Autonomous Task Execution [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/sharpa-s-humanoid-robot-with-dexterous-hand-the-future-of-au/image-1-1767973298166.jpg)