Silent Hill: Townfall and the Perfect Horror of British Weather: Why Fog, Isolation, and Drizzle Make the Best Horror Game Settings [2025]

There's something uniquely unsettling about British weather. Not the dramatic thunderstorms or apocalyptic blizzards you see in Hollywood films, but the mundane, creeping kind of grey that settles over everything like a ghost that never leaves. The kind where you can't quite tell if you're in heavy rain or just walking through a cloud. The kind that makes you feel small, insignificant, and a little bit trapped.

This is the atmospheric goldmine that Silent Hill: Townfall taps into, and frankly, it's genius.

When Screen Burn announced their upcoming survival horror game, scheduled for release in 2026, most people fixated on the obvious horror elements: hospitals, medical equipment fused to monsters, and the franchise's signature fog. But what really matters here is something subtler. The developers aren't just slapping a creepy setting onto a game template. They're building something that understands how real, everyday environments become horrifying when they're rendered with authenticity and attention to cultural detail.

I spent hours diving into the recent State of Play presentation and the accompanying developer documentary about Townfall, and what struck me most was this: the developers at Screen Burn aren't making a game about some heightened, exaggerated version of a Scottish fishing town. They're making a game about their own home, treated with genuine affection and profound unease simultaneously.

That's a much harder thing to pull off than it sounds.

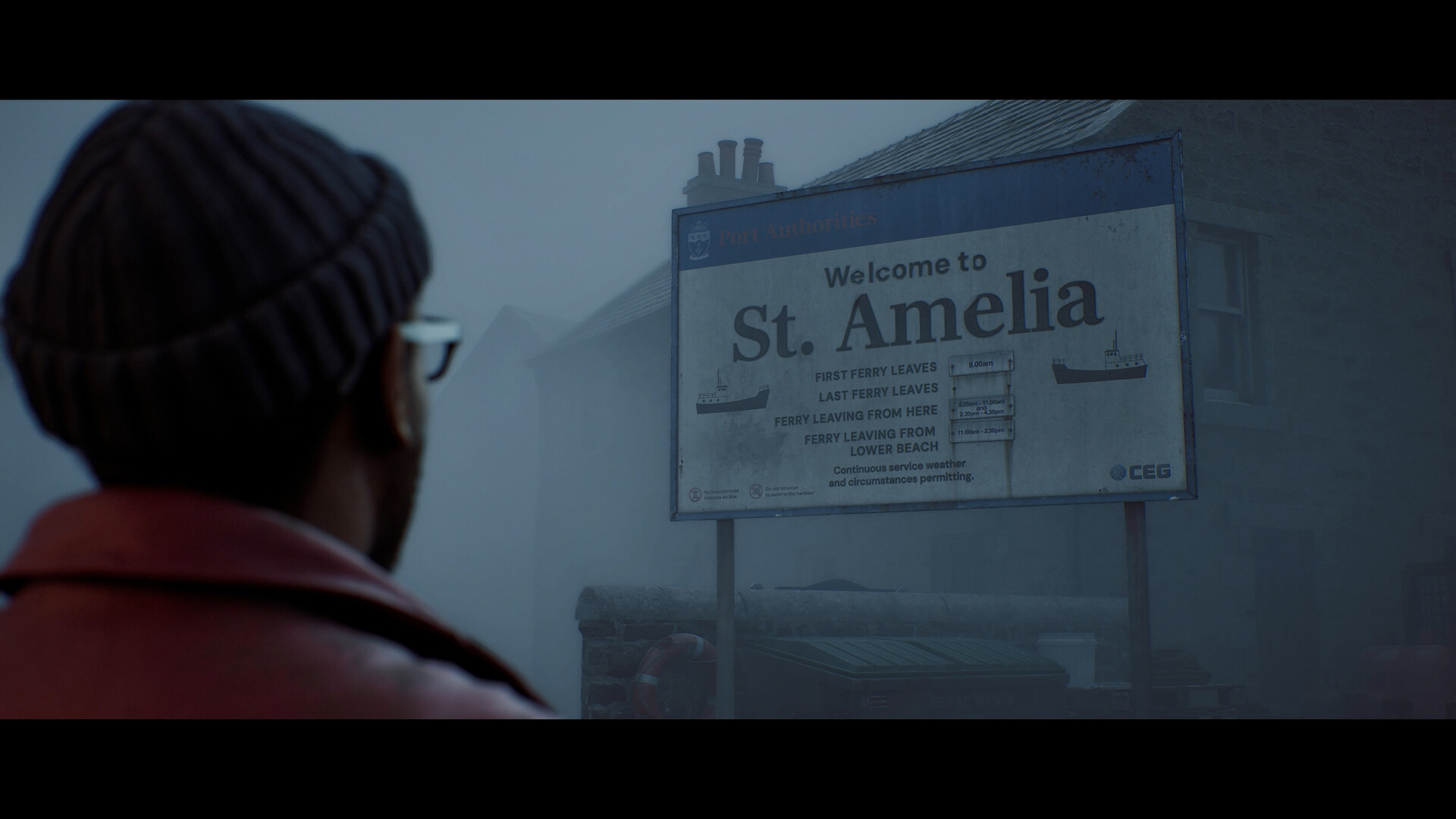

The game is set in St. Amelia, a fictional fishing town that could exist anywhere on the Scottish coast. The fog isn't just window dressing. According to art director Paul Abbott in the documentary, the misty, grey environment directly parallels his own childhood walks to school in similar towns. When you layer that authentic familiarity with the mounting dread that comes from survival horror gameplay, something powerful happens. The familiar becomes wrong. The everyday becomes threatening.

That tension between knowing a place intimately and finding it suddenly alien is where Townfall finds its psychological edge. This isn't Resident Evil's sterile lab or Silent Hill's supernatural small-town America. This is Scotland: grey, damp, isolated, and somehow more vulnerable because of it.

In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore what makes Townfall's approach to atmospheric horror so effective, how it builds on the legacy of the Silent Hill franchise while charting its own course, and why British weather might actually be the perfect narrative device for modern survival horror games.

TL; DR

- Silent Hill: Townfall uses authentic Scottish atmosphere and medical horror as its core tension builders, launching in 2026

- Screen Burn developed the game while drawing directly from personal childhood experiences in similar Scottish towns

- The game emphasizes analog technology and medical imagery more heavily than previous Silent Hill entries

- Atmospheric fog and grey weather replace supernatural fog as a grounding mechanism for horror

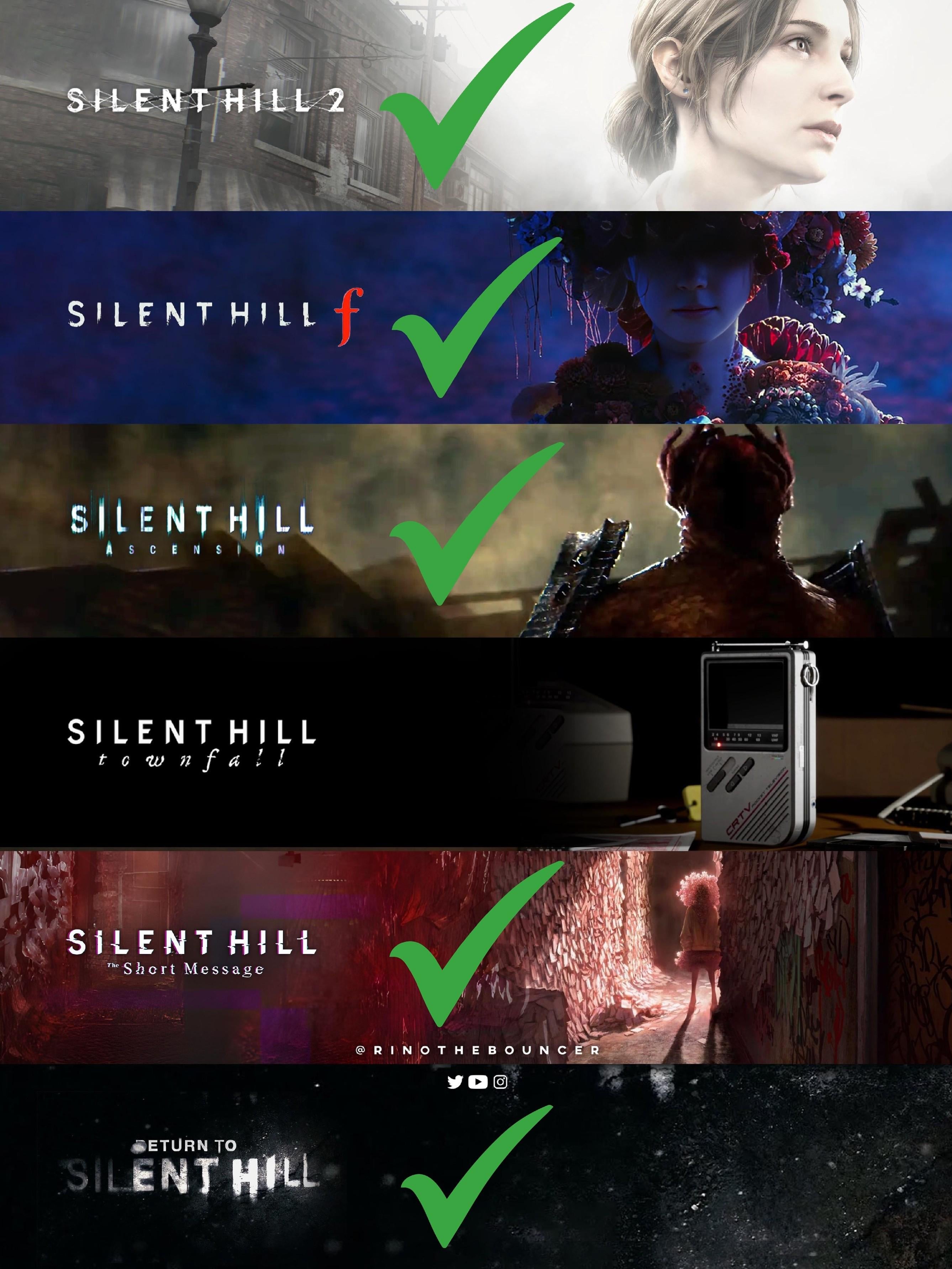

- The franchise is experiencing a creative renaissance with strong entries like the Silent Hill 2 Remake and Silent Hill f

- Setting design matters more than jump scares in modern survival horror games

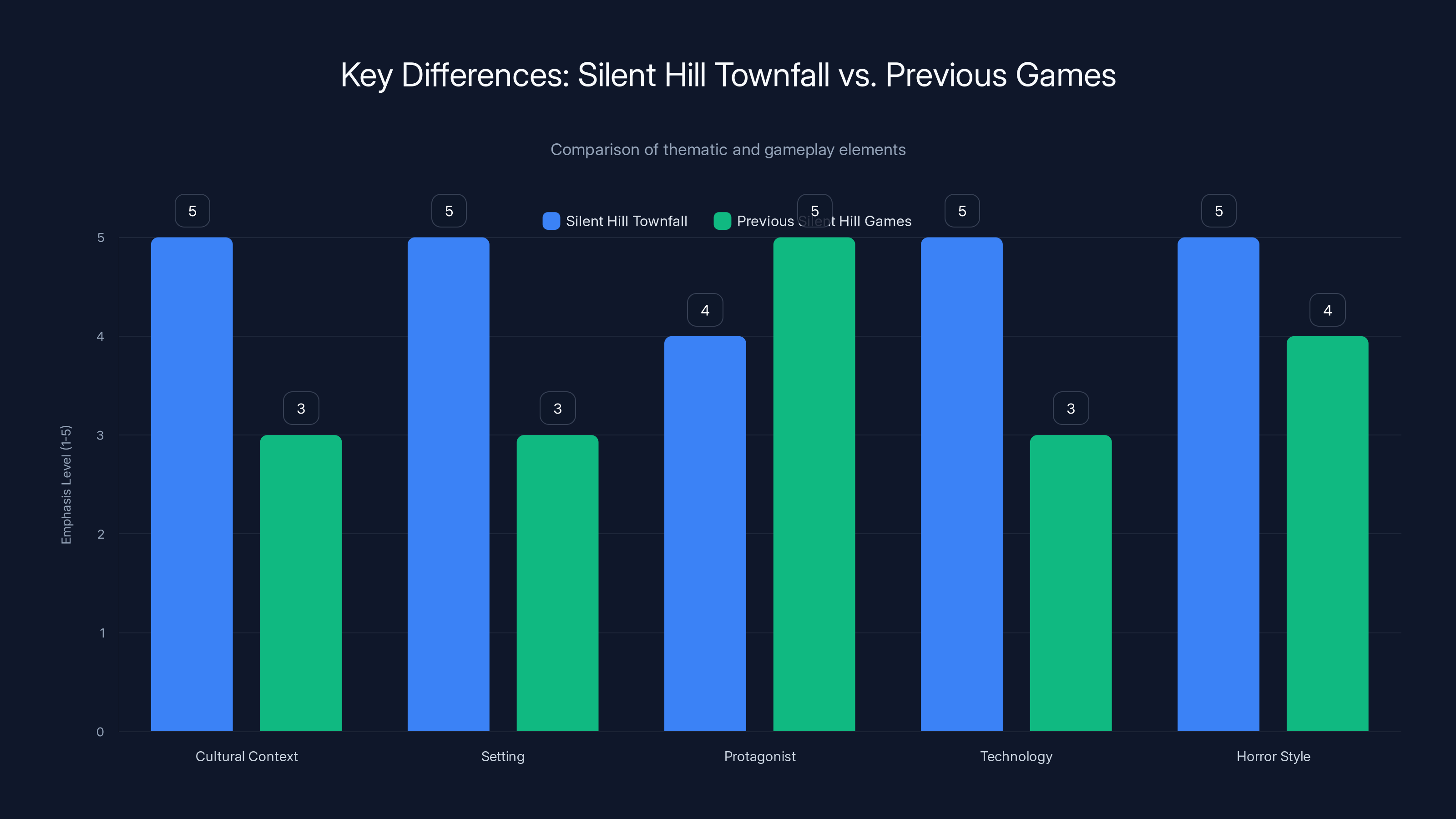

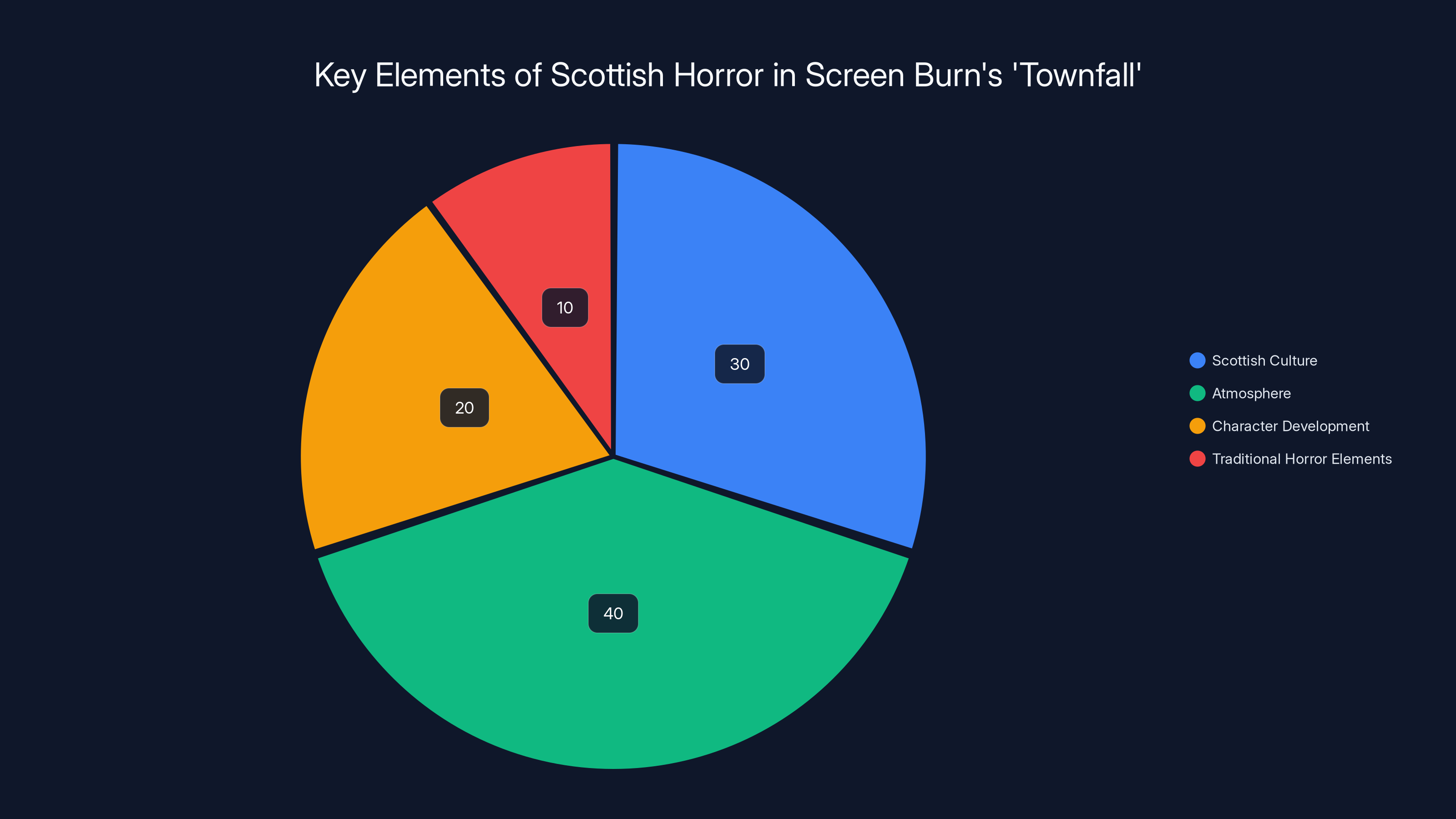

Silent Hill Townfall emphasizes cultural context, setting, and atmospheric horror more than previous entries, offering a fresh take on the franchise. Estimated data based on thematic analysis.

The Silent Hill Franchise: A History of Atmospheric Horror

To understand what makes Townfall significant, you need to understand where the Silent Hill franchise came from and why it matters so much to horror gaming.

Silent Hill debuted in 1999 as a response to Resident Evil's dominance in survival horror. While Resident Evil focused on action and biological horror with a military-industrial bent, Silent Hill took a different approach. It was more concerned with psychological horror, with the town itself as a character rather than just a backdrop. The fog that's become synonymous with the series actually started as a technical limitation—the developers wanted an open-world town but lacked the computing power to render it all. Instead, they turned that limitation into the game's most iconic visual signature.

That fog became a metaphor for confusion, for inability to see ahead, for the way trauma obscures understanding. Each protagonist came to Silent Hill because the town called to them, because it reflected their inner pain back at them. The town was less a place and more a manifestation of guilt, regret, and unresolved psychological wounds.

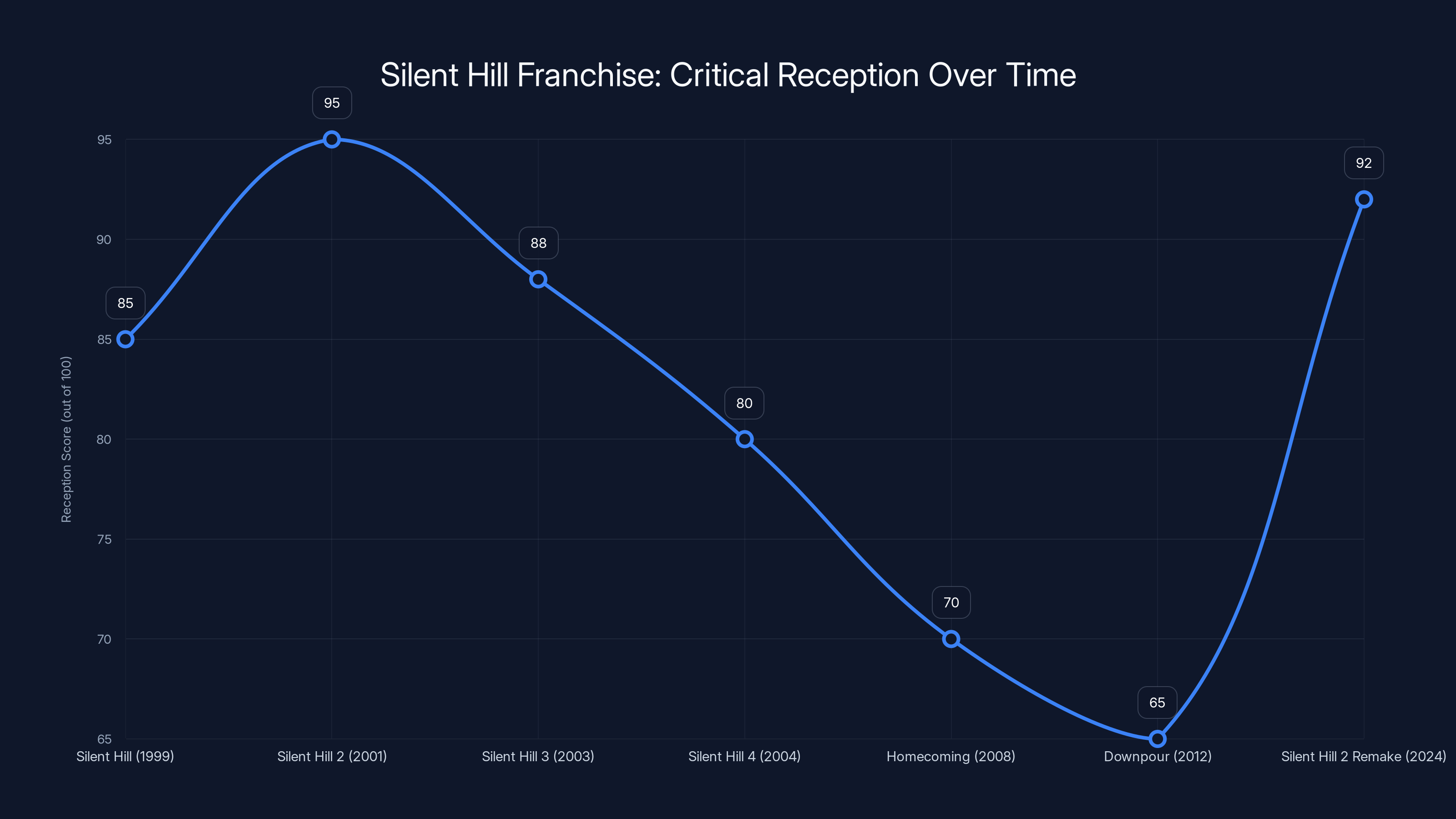

The original quadrilogy (1999-2004) established what Silent Hill fundamentally was: a game series about how places can become mirrors for internal suffering. Silent Hill 2 is widely considered one of the greatest horror games ever made, and much of that reputation comes from how perfectly it integrates setting, story, and gameplay. The town's every element—from broken hospitals to grotesque monsters to environmental puzzles—serves the protagonist's emotional journey.

After the fourth game, the franchise struggled. Homecoming was competent but forgettable. Downpour tried to recapture the magic but never quite landed. For a long time, Silent Hill felt like a series living off past glory, acknowledged as important but not essential.

Then something shifted. The Silent Hill 2 Remake launched in October 2024, and it was genuinely excellent. It modernized the 2001 original without losing what made it special, updating controls and combat while keeping the psychological core intact. Simultaneously, Silent Hill f released in Japan, offering a fresh take on the franchise with a new protagonist and new town. These weren't just nostalgia projects—they were proofs of concept that the franchise still had storytelling capacity.

Into that renewed creative energy steps Townfall, developed by Screen Burn, a small Scottish studio. This is important. Silent Hill has traditionally been about American anxiety, about distinctly American trauma manifested in a generic small town. Townfall takes the formula and transplants it to Scotland, which changes everything about what the game can say.

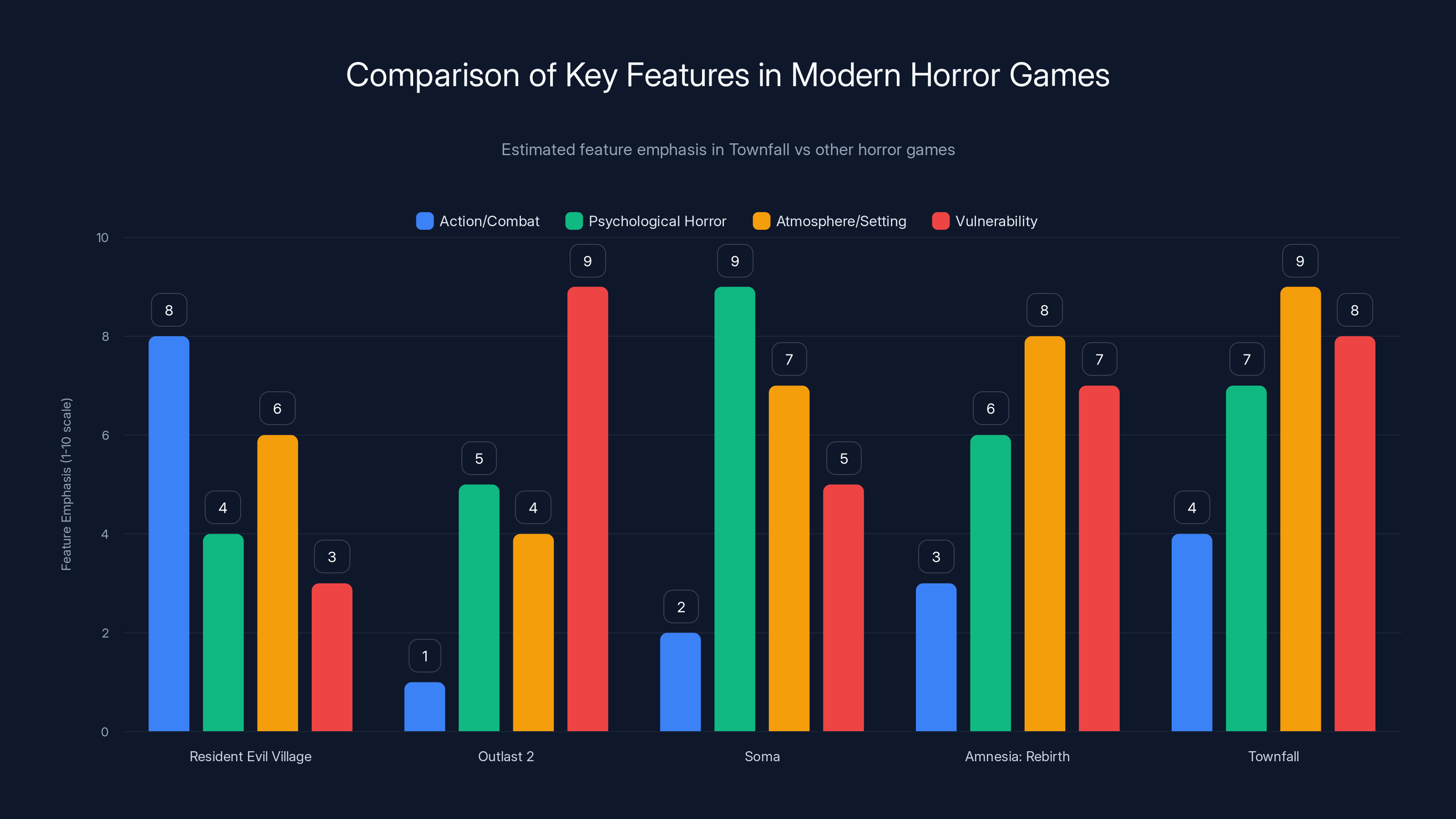

Townfall aims to synthesize elements from various horror games, balancing atmosphere, psychological horror, and vulnerability, while maintaining moderate action elements. Estimated data based on game descriptions.

Screen Burn: A Scottish Studio Making Scottish Horror

Screen Burn is a relatively small developer, but "small" shouldn't read as "inexperienced" or "limited." The studio was founded by veterans of the industry who chose to base themselves in Scotland deliberately. This wasn't an accident of geography—it was a creative choice.

In the developer documentary released after the State of Play, writer and director Jon Mc Kellan explains the studio's philosophy. They weren't interested in making a generic horror game that happened to be set in Scotland. They wanted to make a game that understood Scotland, that used Scottish culture and Scottish geography as essential narrative devices rather than aesthetic overlays.

This philosophy is evident in every discussion about Townfall. When Mc Kellan first showed art director Paul Abbott the misty, foggy environments, Abbott's reaction was immediate: "That felt like a walk to school when I was growing up." This wasn't manufactured nostalgia. This was authentic memory informing game design.

Abbott grew up in small fishing towns similar to St. Amelia, the setting of Townfall. He describes these places as "beautifully epic, grey, drizzly environments." That's not how you typically hear video game settings described. Epic and grey and drizzly aren't usually words that accompany each other in marketing materials. But that's exactly the atmosphere Screen Burn is going for.

There's a risk in this approach. Authentic Scottish atmosphere could read as slow, depressing, and narratively inert to players expecting the dramatic set pieces and visceral scares of modern horror. But Screen Burn seems aware of this. They're not making a walking simulator with horror elements tacked on. They're making a survival horror game where the horror emerges organically from atmosphere, from feeling trapped in a familiar place that's become alien.

The studio's authenticity extends beyond setting to character and narrative. The protagonist, Simon, isn't some generic action hero. He arrives in St. Amelia as a patient, with an IV drip and a hospital wristband. He's vulnerable by default. He's marked as sick, as other, from the moment players take control. This creates an immediate sense of displacement—even before anything supernatural happens, the player is uncomfortable, displaced, unsure why they're in this town or what they're doing here.

That's strong game design rooted in real understanding of how vulnerability and displacement actually feel.

British Weather as a Horror Element: Why Fog and Drizzle Are Scarier Than Demons

Let's be direct: British weather is genuinely unsettling when you're actually living in it. It's not the dramatic, cinematic kind of weather that translates well to film. It's the banal, persistent kind that wears you down through accumulated minor discomforts.

The fog doesn't come and go—it lingers. You can't see more than a few meters ahead. Streets you know well become alien. You can hear things in the fog that you can't see. Your sense of direction falters because visual landmarks disappear. This is especially true in Scottish towns where geography is complicated by hills, lochs, and winding coastal roads.

Earlier Silent Hill games used fog primarily as a visual effect. The supernatural fog rolled in and obscured the town, signaling that something was wrong, that reality had slipped. In Townfall, the fog is just... weather. It's what St. Amelia looks like most days. This is actually more unsettling because it eliminates the comfort of knowing when something is "wrong." The wrongness is already there in the atmosphere.

There's also something about Scottish drizzle—not rain, but drizzle—that creates a particular kind of oppressive environment. It's not dramatic enough to be interesting. It's not heavy enough to keep you indoors necessarily. It's just there, making everything wet, making everything grey, making everything feel damp and uncomfortable and slightly wrong. It seeps into your experience of a place.

Combine that with the isolation of a Scottish fishing town in 2026. These towns are economically struggling in many cases. Population has declined. The fishing industry has contracted. Young people move away. What remains is older, quieter, emptier. There's genuine melancholy baked into the geography.

Screen Burn isn't adding darkness to these places—they're revealing the darkness that's already there, that already exists in the reality of what these towns are. That's profoundly more effective than imposing horror on a setting from outside.

The weather also serves a mechanical function in horror games. Reduced visibility increases tension because the player can't see threats coming. It forces slower, more cautious movement. It isolates the player within their own limited perception. In Townfall, you're not moving carefully because demons might jump out—you're moving carefully because you can't see, because the fog itself is suffocating, because the familiar is rendered uncertain.

The Silent Hill franchise saw its peak with Silent Hill 2, and after a decline, the 2024 remake revitalized its critical acclaim. Estimated data for some entries.

Medical Horror and Body Horror: The Anatomy of Threat

While the atmospheric and geographic elements of Townfall are innovative, the game also leans into classic Silent Hill territory: medical horror. Hospitals, medical equipment, bodily harm and transformation—these are staples of the franchise since the original game in 1999.

But Townfall seems to be emphasizing medical horror more centrally than even previous entries. The protagonist Simon arrives with an IV drip and hospital wristband. The glimpses of monsters in the trailers show medical equipment integrated into their forms—tubes and wires and medical machinery fused with flesh. The dilapidated hospital is a central location.

This thematic focus makes sense in a Scottish context. The National Health Service in Scotland, like healthcare systems globally, has struggled with funding and resources. Hospitals in smaller towns have closed or consolidated. The medical infrastructure that communities once took for granted has disappeared. Using a hospital as a horror location taps into real anxiety about vulnerability, about what happens when healthcare fails you, about what happens when institutions crumble.

Medical horror also speaks to bodily vulnerability in a way that appeals to contemporary audiences. In the early 2000s, when the original Silent Hill games were released, medical horror was about external threats—viruses, diseases, biological weapons. Modern medical horror is often about the body itself as a threat, about transformation and loss of control.

Simon's IV drip connects him physically to the town, to whatever is happening in St. Amelia. He's not just exploring a place—he's being sustained or transformed by it. The wristband marks him as a patient, as someone being monitored and controlled. These small details create visceral unease about bodily autonomy and medical control.

The fusion of medical equipment with monsters speaks to a particular kind of contemporary horror: the fear that technology meant to help us can become grotesque, can become weaponized, can violate our bodies. In a town where healthcare infrastructure is failing, that fear becomes concrete and real.

The Silent Hill 2 Remake: Proof That the Franchise Can Still Deliver

Before we get too speculative about Townfall, it's worth acknowledging that the franchise already proved its staying power with the 2024 Silent Hill 2 Remake.

The original Silent Hill 2 (2001) is one of the most acclaimed horror games ever made. It's regularly ranked in "greatest games of all time" lists, which is remarkable for a game that's over two decades old. Its protagonist, James Sunderland, arrives in Silent Hill searching for his wife, but the game is really about James's guilt, shame, and inability to face what he's done. Every monster, puzzle, and environmental detail serves that emotional core.

Remaking such a beloved game was inherently risky. Fans are protective of their classics. Changes that seem small to developers can feel like desecrations to longtime players. But the 2024 remake, developed by Bloober Team, walked that line carefully. It modernized controls and gameplay mechanics that had aged poorly while preserving the psychological core. More importantly, it proved that the formula still works. Modern players, encountering Silent Hill 2's story for the first time, found it genuinely unsettling. The psychological horror remained effective.

This matters for Townfall because it establishes that there's appetite for this kind of horror. The remake's success meant that Konami and other publishers were willing to invest in psychological horror games at all, in an era increasingly dominated by action-focused titles and live-service games.

The remake also established a creative foundation that Townfall can build on. Bloober Team's approach to modernizing the game—keeping the setting and atmosphere intact while updating how players interact with it—provides a template for how you can evolve the Silent Hill formula. Townfall builds on that, taking the proven formula and applying it to new setting with a new developer bringing their own perspective.

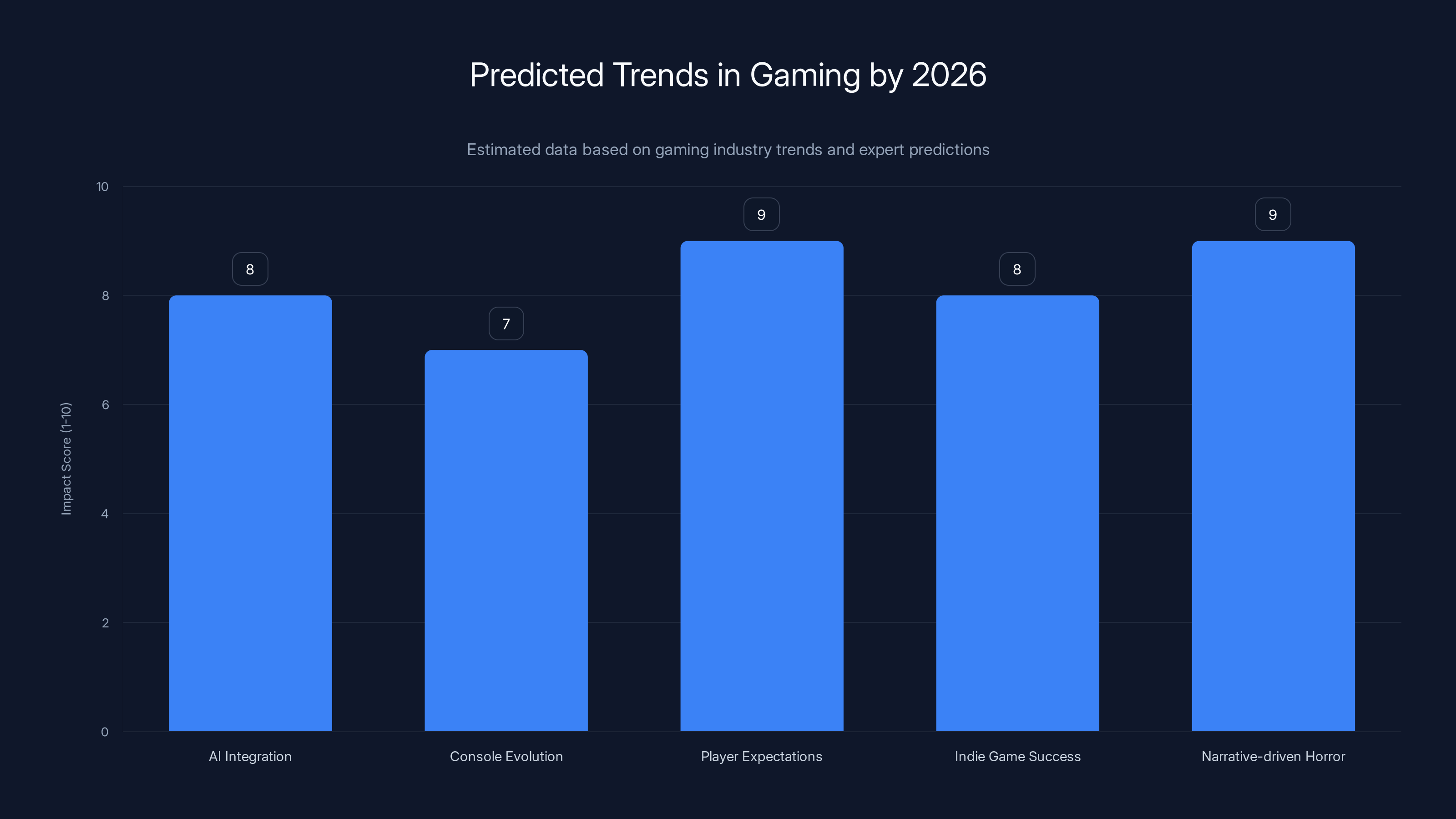

By 2026, AI integration and narrative-driven horror are expected to significantly shape the gaming landscape. Estimated data.

Silent Hill f: A Japanese Reimagining and Proof of Creative Expansion

Alongside the remake, Konami released Silent Hill f in Japan in 2024, with a global release following. This game represented something different: a new Silent Hill game with an original protagonist, original story, and original setting, rather than a remake or sequel.

Silent Hill f introduced Yoko, a Japanese schoolgirl who arrives in a village where something has gone deeply wrong. The game's aesthetic is distinctly Japanese—the village design, the cultural references, the monsters all carry Japanese design sensibilities. This was crucial: it proved that Silent Hill could be transplanted to other cultural contexts and still feel like Silent Hill.

The critical reception of Silent Hill f was strong enough that it became, for many critics, the best new horror game of 2024. Some even preferred it to the remake. This told Konami and investors a clear story: original Silent Hill games exploring different cultural contexts were commercially and critically viable.

Townfall exists in that created space of possibility. Screen Burn is taking the formula that worked in Japan and applying it to Scotland. Each new game is a proof of concept that Silent Hill works because the core is portable—the fog, the dread, the atmosphere can take different shapes in different places.

The Rise of Atmospheric Horror and the Decline of Jump Scare Culture

If you look at horror gaming trends over the past five years, there's a clear shift away from jump-scare-dependent horror and toward atmospheric, psychological horror. Games like Amnesia: The Dark Descent and Outlast proved that jump scares could carry a game, but they also taught players that jump scares lose effectiveness through repetition.

Conversely, games that build dread through atmosphere, that make players afraid without necessarily showing them something frightening, have had extraordinary staying power. The opening hours of Resident Evil Village (2021) received criticism for its jump scares, but the atmospheric sections—walking through foggy villages, hearing enemies in the darkness—are what players remember.

Townfall's emphasis on atmosphere over spectacle aligns with this industry trend. Screen Burn isn't betting on scary monsters or shocking moments. They're betting that a Scottish fishing town rendered with authentic detail, surrounded by fog and isolation, with a protagonist marked as vulnerable, will be inherently unsettling to players.

This is a high-risk strategy. Atmospheric horror requires trust from the player. Players need to buy into the setting, need to accept that nothing may happen for extended periods, need to remain tense in the absence of concrete threat. Many modern players, raised on tighter, faster-paced games, may find this frustrating.

But there's also a subset of horror fans who have grown tired of action-horror hybrids, who want something slower and more psychologically immersive. Townfall seems aimed at that audience.

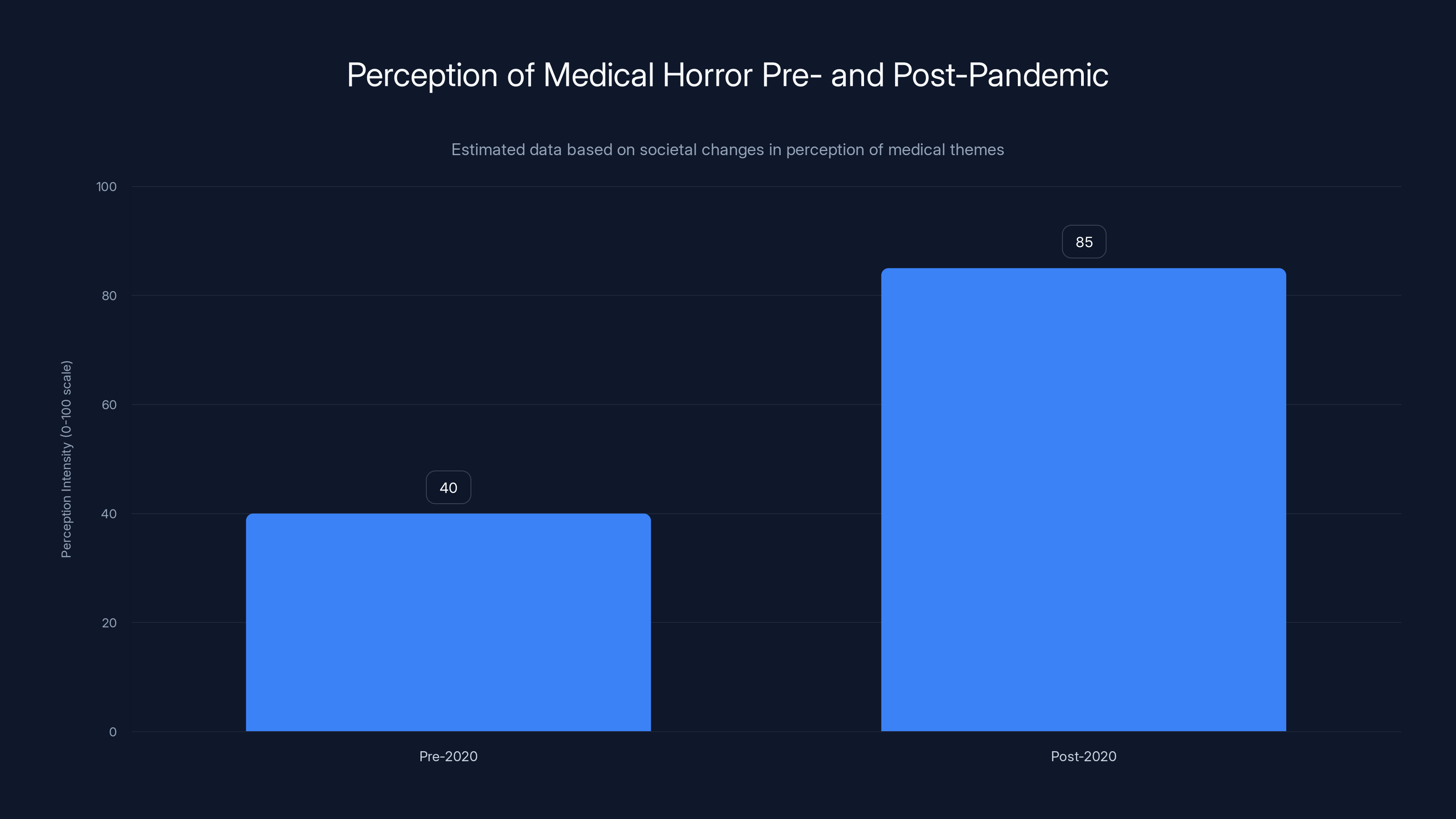

Estimated data suggests that the perception of medical horror has intensified significantly post-pandemic, reflecting increased societal awareness of healthcare vulnerabilities.

Analog Technology and Retro-Futurism in Game Design

One detail from the trailers and documentation that stands out: Townfall seems to feature prominently analog technology. Players have glimpsed old phones, tape recorders, medical machinery, and other pre-digital technology in the game's world.

This isn't a coincidence. Analog technology in horror has a particular resonance because it feels finite and limited. Digital systems feel unlimited, infinitely connected, cloudlike. Analog systems are physical and bounded. A tape can be full. A phone can have a limited line. A piece of paper can be torn.

For psychological horror, this matters tremendously. Analog systems create natural friction and limitation. In a digital game world, you can see infinite messages, interact with infinite objects. In an analog world, you interact with what's physically present, and that creates scarcity and weight.

Using analog technology also creates period ambiguity. Is Townfall set in the present day, or is it a retro-future? Trailers haven't clearly specified, which creates its own kind of unease. The protagonist arrives by what looks like a modern bus, but the town seems frozen in time.

From a narrative perspective, analog technology also fits Scotland. Rural Scottish communities that haven't boomed economically often preserve older infrastructure and technology longer than wealthy urban centers. Using analog tech makes St. Amelia feel real and grounded in a way that modern smart homes and digital networks wouldn't.

The Isolation Problem: Why Small Towns Make Better Horror Settings

There's a specific fear associated with being in a small town and realizing that something has gone very wrong, and that no one from outside is coming to help.

Large cities offer the comfort of anonymity and the presence of institutions. If something goes wrong, police, hospitals, emergency services respond. In a small town, especially a Scottish fishing village, that infrastructure is limited. Police are far away. Hospitals have been consolidated. The only help available is whatever you can find locally, and if the town itself is the problem, then there is no help.

This is especially true for St. Amelia as depicted in the trailers. It's not a thriving tourist destination. It's a working fishing town that has seen better days. The shops are closed. The streets are empty. The person who might be able to help you left years ago.

Simon, arriving in this town with a medical condition requiring an IV drip, is maximally vulnerable. He can't run effectively. He needs medication and care. He's dependent on whatever medical resources the town can provide. If those resources are corrupted or insufficient, he's trapped.

This creates a form of horror that's become increasingly relevant: institutional failure as horror. Not supernatural evil, but the very real evil of systems designed to help you becoming compromised or insufficient. A hospital that's supposed to treat you becomes a source of threat. A town that's supposed to be safe becomes a trap.

Screen Burn's 'Townfall' emphasizes atmosphere and Scottish culture, making up 70% of its narrative focus. Estimated data based on studio's creative philosophy.

Character Design and Vulnerability: Making Players Feel Small

One design choice that stands out about Townfall is the decision to make Simon arrive in the town as a patient. This isn't a muscular protagonist chosen because of their combat skills. This isn't an action hero or a soldier or a police officer—categories that traditionally come with presumed competence and physical capability.

Simon is sick. He has an IV. He wears a hospital wristband. He's already diminished before the game even begins.

This changes how players approach the game mechanically. A weak protagonist means you can't fight your way out of problems. You have to be clever, have to hide, have to solve puzzles to progress. But it also changes how players feel emotionally. Vulnerability creates investment. Playing as someone weak makes threats feel more genuine. If your protagonist can barely defend themselves, then the world becomes genuinely dangerous.

Compare this to other horror games: Resident Evil traditionally puts you in the role of a law enforcement professional or trained operative. Dead Space's Isaac Clarke is an engineer with tools. Alan Wake is a writer who discovers he can use his words as weapons. Each of these gives players some sense of capability or competence.

Townfall goes the opposite direction. Simon is just a sick person who arrived in a town. That's it. That's all you get.

There's also something thematically interesting about making the protagonist a patient. Patients are people whose bodies have betrayed them, who need help, who have surrendered agency to medical professionals. Simon doesn't choose to be a patient—he is one. This existential state of not being in control of one's own body, of depending on external systems for survival, becomes the game's central emotional note.

The State of Play Presentation: What We Know for Certain

Let's ground our speculation in what we actually know from official presentations. Play Station State of Play featured a new trailer for Townfall that revealed several key details:

Visual Design: The trailer emphasized fog and grey weather. The town feels weathered, not quite abandoned but not thriving. Buildings are older, infrastructure is worn. The color palette is muted: greys, greens, and browns with occasional splashes of institutional color (medical equipment green, hospital white).

Monsters: The trailers show creatures that incorporate medical equipment into their bodies. This wasn't random body horror—it was specific hospital horror. Tubes and wires and surgical equipment fused with flesh. The implication is clear: something has happened to the hospital and the people in it.

Protagonist State: Simon is shown with various injuries and medical equipment. He's not stable or secure. He's in active distress throughout the trailer.

Environmental Detail: The town has recognizable elements—shops, streets, a harbor. But everything is slightly off. Shuttered buildings. Empty streets. The sense of a place that's lost its reason for existing.

Tone: The trailer avoids jump scares. Instead, it builds dread through atmosphere, through showing the protagonist's vulnerability, through the claustrophobic feeling of being surrounded by fog and isolated architecture.

Comparison to Other Modern Horror Games: What Makes Townfall Stand Out

To understand what Townfall might achieve, it helps to compare it to other recent horror games and see what the industry has been moving toward.

Resident Evil Village (2021) took horror in an action-oriented direction. It's a beautiful game with strong atmosphere, but it prioritizes combat and spectacle. Players have powerful weapons and combat options. The horror emerges from the action rather than from avoidance.

Outlast 2 (2017) is the opposite: it's a pure evasion game where you have no weapons and must hide or flee. It creates horror through vulnerability, but it's more visceral and immediate than psychological.

Soma (2015) combined psychological horror with science fiction concepts about consciousness and identity. It was slower, more contemplative, more interested in ideas than action.

Amnesia: Rebirth (2020) built atmosphere through exploration and puzzle-solving, with enemies you could avoid rather than directly confront.

Townfall seems positioned to combine elements of all of these: it's slower and more contemplative like Soma, it builds vulnerability like Outlast, it has environmental detail like Resident Evil Village, but it's fundamentally interested in atmosphere and setting as primary horror mechanisms like Amnesia.

It's a synthesis that, on paper, sounds like it could work. The question is execution. Horror games live and die on whether players buy into the emotional state the designer is trying to create. Townfall's entire premise depends on players finding Scottish weather and small-town isolation genuinely unsettling. That's not guaranteed, but it's plausible enough to be interesting.

The Role of Region-Specific Horror in Gaming's Future

One of the most important things Townfall represents is the potential for region-specific horror. For decades, horror games (and horror media more broadly) have been heavily influenced by American and Japanese sensibilities. American horror emphasizes individual agency, evil that can be fought or outsmarted. Japanese horror emphasizes inevitability, the horror of being subject to forces beyond your control.

But horror exists everywhere, and different regions have different fears, different anxieties, different relationships to place and community.

Scottish horror has its own traditions. There's the Gothic tradition of writers like Robert Louis Stevenson and James Hogg. There's the folk tradition of selkies and dark magic. There's the modern reality of economic decline and cultural anxiety. Townfall taps into real anxieties specific to Scotland: isolation, economic decline, healthcare and institutional failure, the permanence of place and the inability to escape.

If Townfall succeeds, it opens a door for other region-specific horror games. What would Irish horror look like? Welsh horror? English horror? Horror from Latin America, Africa, Asia—understood from internal cultural perspectives rather than filtered through Hollywood or Japanese aesthetics?

This matters because it means the horror game genre can continue to evolve by expanding geographically rather than just thematically. Instead of rehashing the same settings and tropes, developers can draw on local knowledge, local fear, local place.

Townfall is positioned at exactly the intersection of cultural specificity and universal horror appeal. The fear of being vulnerable in a place you can't control might be universal, but the specific way that plays out in a Scottish fishing town is unique.

Medical Horror in the Post-Pandemic Era

One more context worth considering: Townfall's emphasis on medical horror and bodily vulnerability arrives in a specific historical moment. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed how people relate to medical institutions, to bodily integrity, to vulnerability.

Pre-2020, medical horror could feel abstract. Post-2020, it's immediate and real. Most players have experienced hospital visits, medical procedures, the vulnerability of not being in control of their own health. Medical horror isn't speculative anymore—it's something most players can relate to viscerally.

Townfall's use of medical imagery—the IV drips, the hospital equipment, the transformed hospital patients—will likely resonate more deeply with modern players than it would have pre-pandemic. The game is arriving at a moment when players are more acutely aware of how institutional failure in healthcare can feel like horror.

This also means Townfall has an opportunity to say something real about healthcare, about institutional failure, about how systems designed to help can become sources of threat when they break down. Whether the game actually addresses these themes thematically remains to be seen, but the potential is there.

The 2026 Launch and the Gaming Landscape

Townfall is scheduled for 2026, which means we're looking at a game that will arrive in a specific moment in gaming's evolution. By 2026, we'll have several more years of AI integration in games, of new console generations fully taking shape, of player expectations continuing to shift.

What we can predict: by 2026, jump-scare horror will be even more played out than it is now. Atmospheric, narrative-driven horror will likely be even more valued. Indie developers proving they can deliver experiences that compete with AAA studios will be even more established.

Townfall, arriving in 2026 from a relatively small Scottish studio but backed by Konami's resources, is positioned as exactly the kind of mid-tier horror experience that's becoming increasingly important to the industry. Not a massive AAA blockbuster, not a scrappy indie game, but something in between with real creative vision.

The waiting period also serves the game. Horror is better experienced with anticipation. The fog of information, the fragments of details revealed through trailers and developer documentaries, the long wait until release—these all build psychological tension. By the time Townfall arrives, players will be primed for it.

What Townfall Might Teach Us About Horror Game Design

Assuming Townfall delivers on its promise, what lessons might it teach the broader industry about horror game design?

First: Setting matters more than spectacle. A detailed, authentic setting can create more dread than any jump scare or graphically detailed monster. Townfall seems to understand that the town itself is the protagonist, and that creating a believable, unsettling version of a real place is harder and more rewarding than creating a fantastical nightmare landscape.

Second: Vulnerability creates investment. A weak protagonist creates emotional stakes. Players care about Simon because Simon can barely help himself. This creates genuine tension because threats feel real.

Third: Cultural specificity enhances rather than limits appeal. Making a game specifically about Scotland, drawing on Scottish culture and Scottish fears, doesn't limit the game's appeal to Scottish players. It enhances the game because cultural specificity creates authenticity, and authenticity creates believability.

Fourth: Atmosphere rewards patience. Modern gaming pushes for constant stimulation, constant action. Horror games that slow down, that ask players to move carefully through spaces, that reward exploration and observation over reaction, create deeper psychological impact.

Fifth: The mundane can be more horrifying than the fantastic. A Scottish fishing town on a grey, drizzly day is inherently more unsettling than a haunted mansion or a supernatural dimension, because it's a place players have actually been or could actually visit.

These lessons extend beyond horror. They're relevant to any game interested in atmosphere, in creating emotional investment through environment, in using setting as narrative.

The Broader Silent Hill Renaissance

It's worth stepping back and acknowledging that Townfall doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a broader moment for the Silent Hill franchise. The 2024 remake proved the original games' value was enduring. Silent Hill f proved the formula works in Japanese contexts. Now Townfall will test whether it works in British contexts.

This is a franchise in creative expansion mode, testing whether it can survive and thrive beyond its original American small-town template. That's a significant statement about horror gaming. It's saying that the genre isn't exhausted, that there's still creative space to explore, that horror can evolve without losing its core identity.

If Townfall succeeds, expect more region-specific horror entries. If it fails, expect the industry to contract back to safer formulas. Either way, Townfall will have said something important about the state of horror gaming in the 2020s.

For players who love horror games, Townfall is something to anticipate. It's arriving with a clear creative vision from developers who understand their setting deeply. It's built on the proven success of the Silent Hill 2 remake and the critical validation of Silent Hill f. It's addressing themes—vulnerability, institutional failure, isolation, medical horror—that resonate in the contemporary moment.

Most importantly, it respects its players' intelligence. It's not trying to trick you with jump scares or shock you into caring. It's trying to create a sustained sense of dread that emerges from place, from atmosphere, from the knowledge that you're trapped somewhere foggy and isolated with no clear way out.

That's a remarkable ambition for a 2026 game. Whether it succeeds, we'll know next year. But the fact that Screen Burn and Konami are willing to take the risk suggests that horror gaming still has room for bold, atmospheric, creatively specific experiences.

In an industry increasingly dominated by safe sequels and live-service games, that's genuinely exciting.

FAQ

What is Silent Hill: Townfall?

Silent Hill: Townfall is an upcoming survival horror game developed by Scottish studio Screen Burn and published by Konami, scheduled to release in 2026. The game is set in St. Amelia, a fictional Scottish fishing town, and follows a protagonist named Simon who arrives in the town as a hospital patient. The game emphasizes atmospheric horror, medical themes, and the unsettling atmosphere of isolated small-town Scotland, rather than relying on jump scares or action sequences. It represents a new direction for the Silent Hill franchise, bringing the established formula to a new cultural context while maintaining the series' core focus on psychological horror and environmental storytelling.

How does Townfall differ from previous Silent Hill games?

Townfall differs from previous Silent Hill entries primarily in its setting, cultural context, and development perspective. While traditional Silent Hill games have focused on American small towns and American anxiety, Townfall transplants the formula to Scotland, drawing heavily on authentic Scottish geography, culture, and contemporary fears. The game is developed by a Scottish studio with personal connections to the setting, giving it a level of cultural specificity previous entries lacked. Additionally, Townfall appears to emphasize analog technology, medical horror, and atmospheric dread over the action-combat elements that some later Silent Hill games incorporated. The protagonist is deliberately vulnerable, arriving as a hospital patient rather than a capable action hero, which creates a different mechanical and emotional dynamic than previous entries.

What makes the setting of Townfall unique for horror?

The setting of a Scottish fishing town, rendered with authentic detail and rooted in real geographic and cultural context, creates a distinct form of horror. Scottish weather, fog, and isolation combine to create atmosphere that feels grounded in reality rather than supernatural. The town's economic decline and depopulation create a sense of abandonment and loss that's more psychologically resonant than traditional haunted-location horror. Art director Paul Abbott has emphasized that the misty, grey, drizzly environment directly parallels his childhood experience in similar Scottish towns, creating authenticity that enhances the horror. Unlike the somewhat generic American small towns of earlier Silent Hill games, St. Amelia feels like a specific, real place, which makes its corruption and wrongness more disturbing because players can recognize and relate to the setting.

Why does Silent Hill: Townfall emphasize medical horror?

Townfall's focus on medical horror—including imagery of medical equipment fused with monsters, the protagonist arriving with an IV drip, and a central dilapidated hospital—serves multiple narrative and thematic purposes. Medical horror taps into contemporary anxiety about bodily vulnerability and institutional failure, concerns heightened in the post-pandemic era when most people have personal experience with hospitals and medical procedures. In the context of rural Scotland, where healthcare infrastructure has been consolidated and rural hospitals have closed, medical horror becomes grounded in real institutional change. The choice to make the protagonist a patient, dependent on medical care, creates existential vulnerability that makes threats feel genuinely dangerous. Medical equipment integrated into monsters speaks to the fear of technology meant to help becoming grotesque or weaponized, and it connects the game's horror to real anxieties about healthcare systems and bodily autonomy.

Is Silent Hill: Townfall connected to other recent Silent Hill games like the 2024 remake and Silent Hill f?

While Townfall is not a direct sequel to the 2024 Silent Hill 2 Remake or Silent Hill f, it exists within the same period of Silent Hill franchise expansion and creative reinvention. The success of the Silent Hill 2 Remake proved that the franchise's original material still resonates with modern audiences, and Silent Hill f demonstrated that the franchise formula can work in different cultural contexts (Japanese horror and setting). Townfall continues this trend by taking the Silent Hill formula to a Scottish context with a new developer bringing their own creative perspective. The three games together represent a conscious strategy by Konami to expand the franchise geographically and culturally, testing whether Silent Hill can work as a template for region-specific horror rather than just American small-town horror. They share DNA and creative philosophy but are independent games with different stories, protagonists, and settings.

When is Silent Hill: Townfall expected to release?

Silent Hill: Townfall is scheduled to release sometime in 2026. A specific release date has not yet been announced by Konami or Screen Burn. The game was first publicly detailed through a Play Station State of Play presentation and was followed by a developer documentary explaining the studio's vision and approach. The 2026 launch window gives the developers time to refine the game while also creating anticipation among horror enthusiasts. The relatively distant release date is typical for games still in development, and the time between now and release will likely include additional trailers, developer updates, and information reveals to build player interest.

What is Screen Burn, and why is the studio significant?

Screen Burn is a Scottish video game developer founded by industry veterans who chose to base the studio in Scotland deliberately. The studio's significance lies in its perspective and authenticity: the developers bring genuine lived experience of Scottish culture and Scottish places to the game they're creating. Art director Paul Abbott and writer-director Jon Mc Kellan both grew up in Scottish fishing towns similar to St. Amelia, the setting of Townfall, which means they're not creating based on external research but on personal memory and understanding. This level of cultural authenticity and personal connection to the setting gives Screen Burn's approach to horror game design a credibility that outside developers might lack. The studio represents a growing trend of smaller, culturally specific development teams creating ambitious games that compete with larger AAA studios, proving that creative vision and authentic perspective matter more than massive budgets.

How does weather function as a horror element in Townfall?

In Townfall, British weather—specifically Scottish fog and drizzle—functions as both atmospheric and mechanical horror. Visually, the persistent fog creates reduced visibility that forces cautious, slow movement and prevents players from seeing threats or navigation landmarks in advance. Psychologically, the grey, damp weather creates a sense of oppression and inescapability that's distinctive because it's familiar and banal rather than fantastical. Early Silent Hill games used supernatural fog as a visual indicator of wrongness. Townfall uses realistic weather as a constant environmental pressure, which is actually more unsettling because it eliminates the comfort of knowing when reality has shifted. The drizzle, mist, and grey sky aren't something the player can escape—they're constant, inescapable, familiar from anyone who's actually experienced Scottish weather, which makes them inherently more psychologically grounded than supernatural phenomena.

What does Townfall's success or failure potentially mean for the horror gaming industry?

Townfall's 2026 release will serve as a test case for several industry trends. If the game succeeds, it validates that horror can continue to evolve by incorporating cultural specificity and atmospheric focus rather than relying on action spectacle or jump scares. Success would demonstrate that players value authentic, region-specific horror and that smaller development teams can compete with AAA studios when backed by creative vision. It would likely encourage more region-specific horror entries from developers in other cultural contexts. If Townfall struggles, the industry may contract back to safer formulas and more action-oriented horror. Either outcome will provide valuable data about player preferences and the viability of atmospheric, culturally specific horror in the contemporary gaming landscape. As a test of whether the Silent Hill formula can successfully translate to non-American contexts with developers rooted in those contexts, Townfall's performance will likely influence how franchises approach geographic and cultural expansion.

Conclusion: The Future of Atmospheric Horror

When you step back from the specific details of Silent Hill: Townfall—the Scottish setting, the medical horror, the protagonist's vulnerability—what you're really looking at is a question about the future of horror gaming itself.

For decades, horror games existed in a relatively narrow creative space. They drew on established tropes: haunted houses, zombies, supernatural monsters, jump scares. Innovation meant tweaking these elements, adding new mechanics, improving graphics. The core formula remained surprisingly consistent.

Then something shifted. Games like Soma and Amnesia proved that atmosphere mattered more than action. The Silent Hill 2 Remake proved that psychological horror from a 2001 game could still unsettle modern players. Silent Hill f proved that the formula worked in Japanese contexts. Now Townfall is testing whether it works in Scottish contexts.

What all of these successes have in common is a commitment to place and authenticity. They're not cynically assembling horror elements from a checklist. They're creating specific, detailed, believable environments and then exploring what horror emerges from those environments naturally.

Townfall takes this approach further than maybe any game has before. It's not just set in Scotland—it's made by Scottish developers drawing on Scottish experience. The horror isn't imposed from outside. It emerges from deep understanding of what Scottish places actually feel like, from the accumulated emotional weight of real geography and real weather and real decline.

That's bold. It's risky. It's the kind of creative vision that could either create something genuinely remarkable or could alienate players looking for conventional horror thrills.

But if it works, Townfall will have proven something important: that horror gaming's future might not be in bigger budgets or more advanced graphics or increasingly elaborate mechanics. It might be in developers taking their own experience, their own place, their own fear seriously, and trusting that the specific is more powerful than the generic.

In a gaming landscape increasingly dominated by safe sequels and blockbuster franchises, that would be genuinely exciting. It would suggest that there's still room for creative risk, for cultural specificity, for horror that respects its players' intelligence enough to trust that atmosphere and authenticity matter more than spectacle.

We won't know if Townfall achieves this vision until 2026. But the fact that Konami and Screen Burn are willing to make the attempt, the fact that the franchise has proven resilient and creative enough to embrace new contexts and new developers, suggests that horror gaming still has remarkable potential.

Silent Hill: Townfall might just be the fog-shrouded harbinger of a whole new era of regional, culturally specific, atmosphere-focused horror games. Or it might just be a good game in an established franchise. Either way, it's something to watch closely.

Because when British weather becomes a weapon, when isolation becomes horror, when a small Scottish town becomes a character in its own tragedy, that's when you know survival horror has found something genuinely new to say.

Key Takeaways

- Silent Hill: Townfall leverages authentic Scottish atmosphere and developer perspective to create horror grounded in real place and experience

- The game emphasizes vulnerability (protagonist as patient), atmospheric dread, and medical horror over action spectacle and jump scares

- Screen Burn's Scottish studio brings genuine cultural understanding to the game, with developers drawing on childhood memories of similar towns

- The Silent Hill franchise is experiencing creative renaissance with successful remake, regional expansion, and new studio perspectives

- Horror gaming industry is shifting toward atmospheric, psychologically focused design that respects player intelligence over mechanical spectacle

- 2026 release will serve as test case for whether region-specific horror and cultural authenticity can drive mainstream success

Related Articles

- Silent Hill: Townfall - First-Person Horror Reinvention [2025]

- Fatal Frame 2: Crimson Butterfly Remake Review [2025]

- Kena: Scars of Kosmora Release Date, Gameplay & Everything We Know [2025]

- PlayStation State of Play February 2025: Complete Watch Guide [2025]

- CD Projekt Red Hires BioWare Veteran as AI Director for Witcher 4 [2025]

- Game Studio Layoffs and Industry Collapse: What Happened to Highguard [2025]

![Silent Hill: Townfall and the Perfect Horror of British Weather [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/silent-hill-townfall-and-the-perfect-horror-of-british-weath/image-1-1770982751902.jpg)