The Quiet Revolution in AI Memory Architecture

There's a shift happening in the world of high-bandwidth memory that nobody's talking about. Not because it's boring—but because most people don't realize it's already reshaping how the world's largest AI companies design and deploy their infrastructure.

Last year, memory bandwidth became the real bottleneck. Not processing power. Everyone's throwing $100 million in GPUs at their data centers, but those GPUs are starving for data. The memory can't keep up. It's like having a Ferrari with a bicycle pump.

That's where high-bandwidth memory (HBM) comes in. It's specialized. It's expensive. It's only for the hyperscalers—Open AI, Google, Meta, and the rest of the trillion-dollar crowd. For years, HBM stayed locked behind massive pin counts, expensive silicon interposers, and manufacturing complexity that made the economics work only at hyperscale.

But now, the JEDEC Solid State Technology Association is pushing forward with something called SPHBM4 (Standard Package High Bandwidth Memory 4). It's a technical solution to a very real problem: how do you preserve HBM's extraordinary bandwidth while dropping the cost barriers that have kept this technology sealed off from broader adoption?

Here's the catch—and this is important—it doesn't mean HBM is coming to your gaming PC. SPHBM4 isn't about democratizing memory. It's about optimizing economics for the companies that are already spending billions on AI infrastructure.

This article breaks down what SPHBM4 is, why it matters, and what it means for the next five years of AI hardware development.

TL; DR

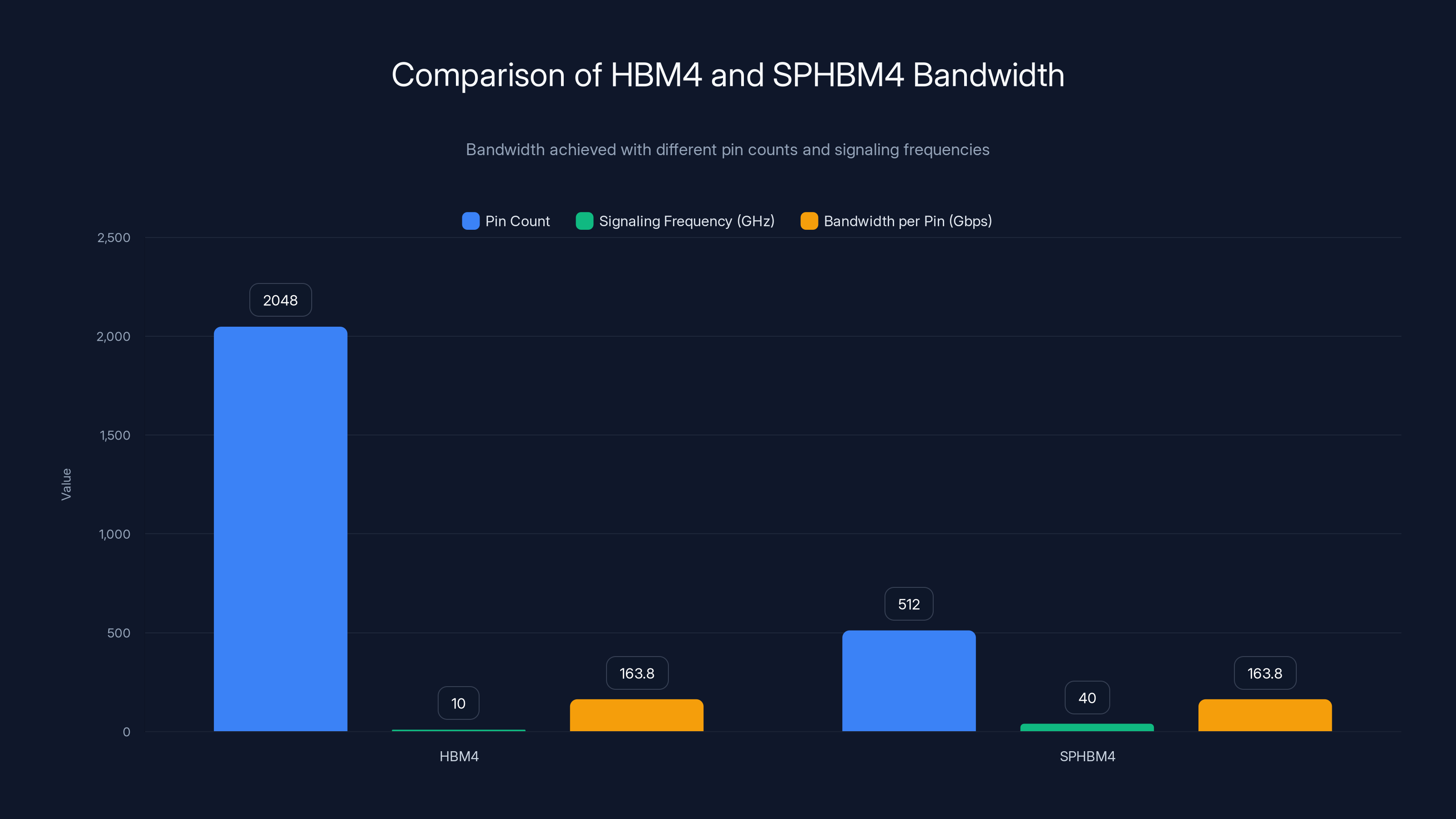

- SPHBM4 uses 512 pins instead of HBM4's 2,048, relying on 4:1 serialization to maintain bandwidth while reducing packaging complexity

- Organic substrates replace expensive silicon interposers, cutting manufacturing costs and enabling longer channel lengths between accelerators and memory stacks

- This preserves HBM-class bandwidth and capacity while optimizing cost structures that matter mainly to hyperscale AI deployments

- Consumer RAM markets remain untouched, since SPHBM4 is still specialized stacked memory requiring custom base logic dies

- Major suppliers like Micron, Samsung, and SK Hynix are already working on SPHBM4 implementations, indicating industry-wide commitment

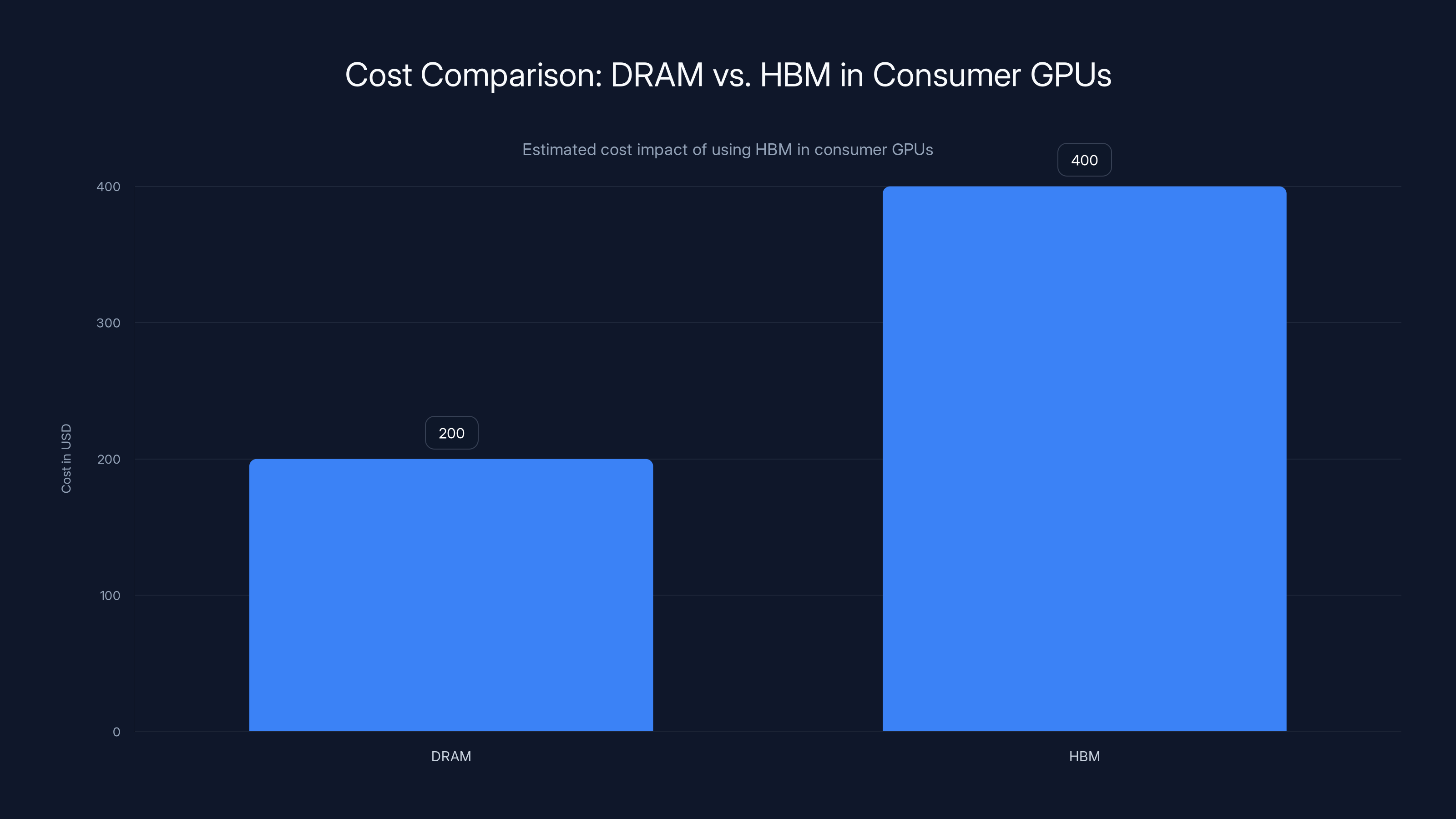

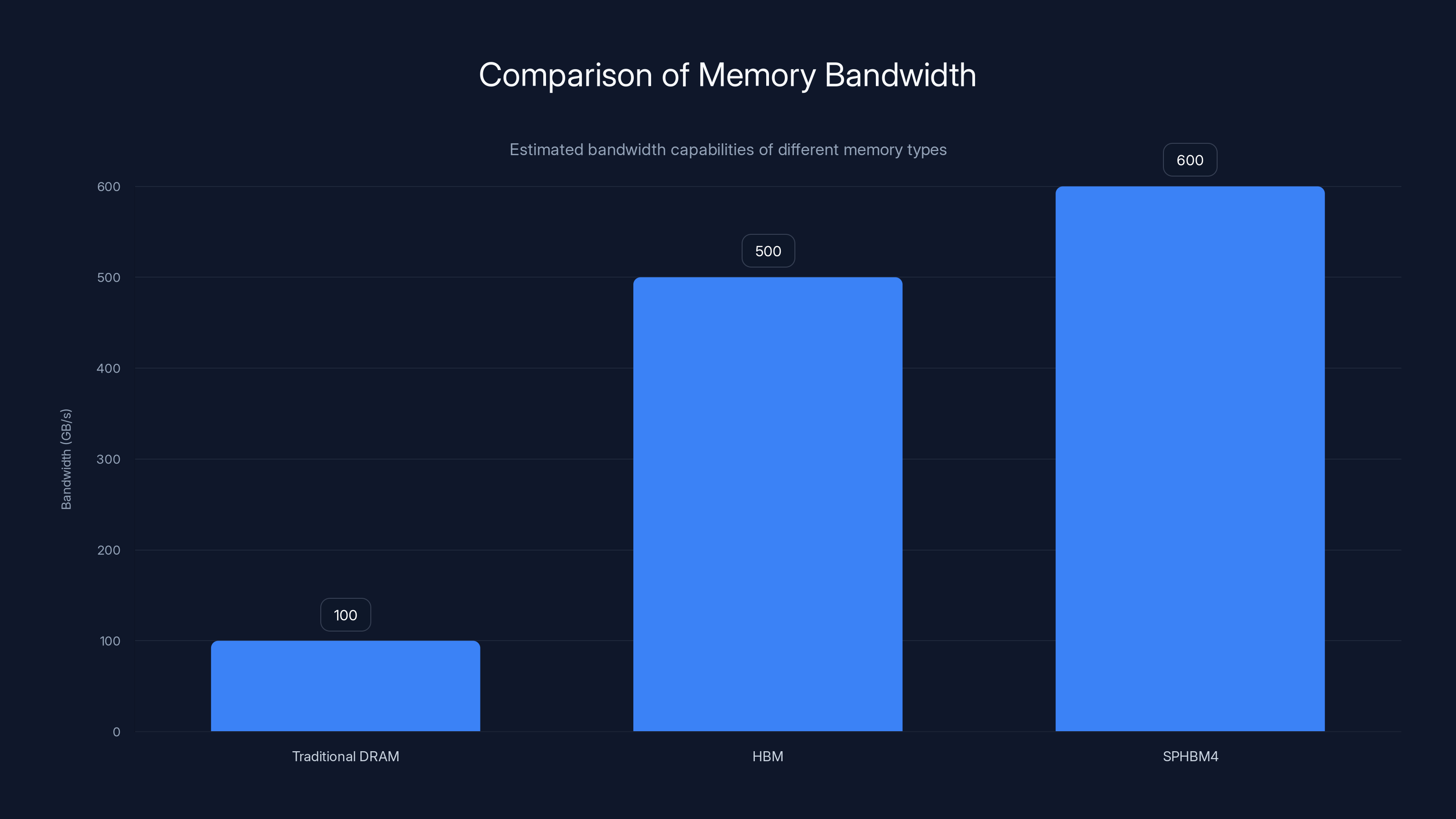

Estimated data shows HBM would double the memory cost in consumer GPUs, making it economically unviable for consumer markets.

What Is HBM and Why Does Bandwidth Matter So Much?

Let's start with the fundamental problem. Modern AI systems—language models, computer vision systems, multimodal transformers—need to move enormous amounts of data between compute and memory. Every single operation depends on this flow.

Traditional DRAM (the stuff in your laptop) has a maximum bandwidth of around 100 GB/s. That was fine when CPUs ran at 3GHz and processed one instruction at a time. But GPU clusters running 8,000 parallel threads? That bandwidth becomes a catastrophic bottleneck.

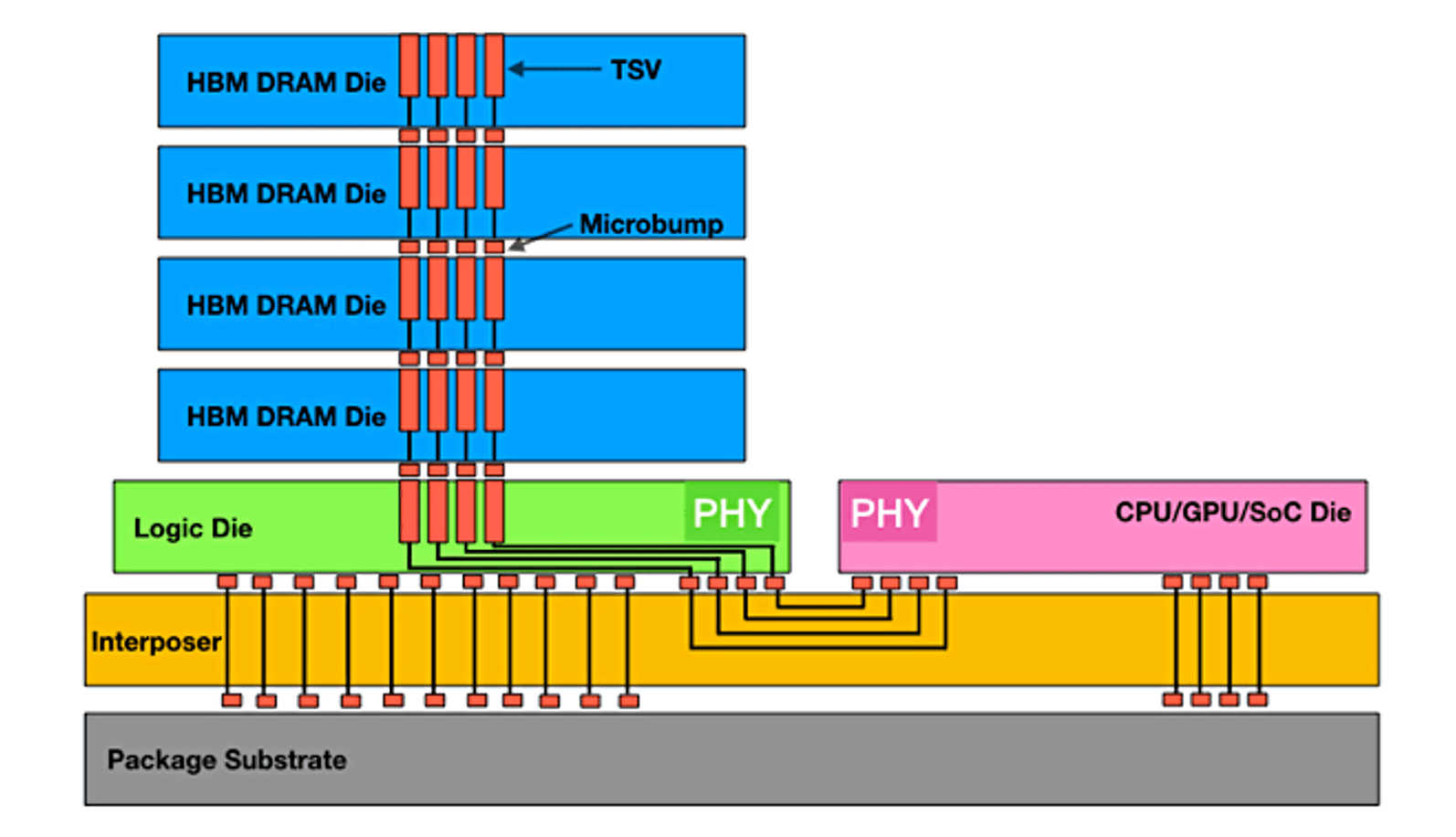

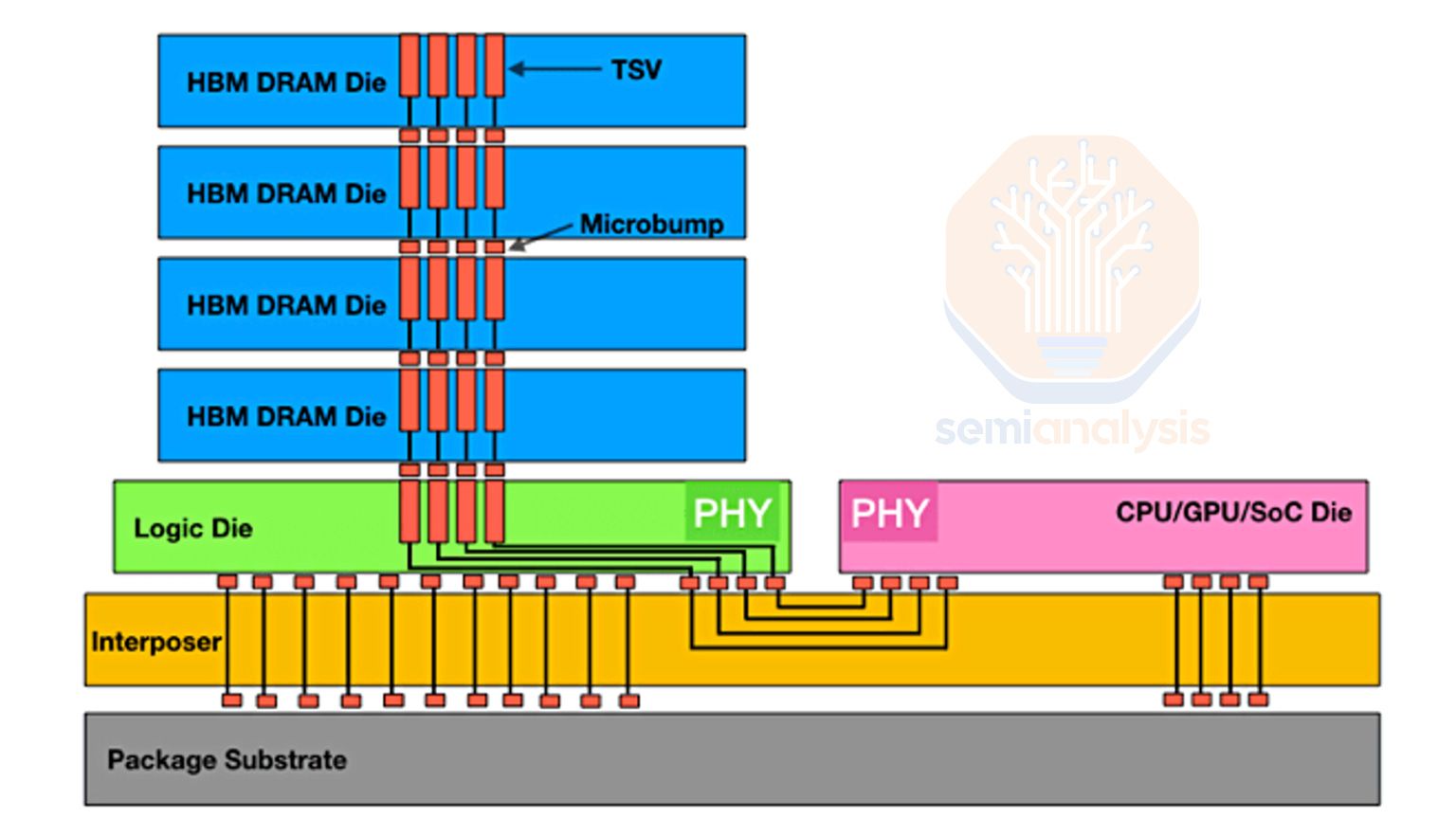

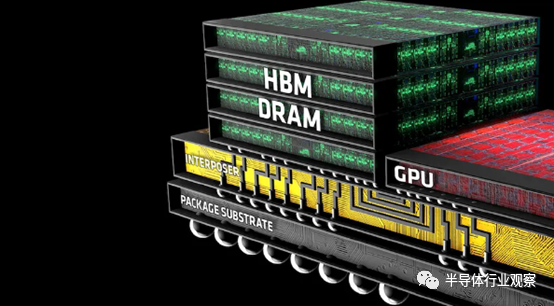

High-bandwidth memory solves this through a radical approach: instead of a single wide data path, HBM stacks memory dies directly on top of each other, connecting them with an enormous number of simultaneous electrical contacts called bump pitches. This vertical integration creates a massive parallel interface that can push 500+ GB/s in a single package.

The tradeoff is complexity. Those thousands of electrical contacts have to be routed through expensive silicon interposers. Manufacturing tolerances are tighter. Design cycles are longer. The cost per gigabyte is roughly 10x higher than standard DRAM.

But here's why hyperscalers accept this cost: a single GPU cluster running an 8 billion parameter language model can cost

Consumer systems? A $1,500 gaming PC has no such math. The cost simply doesn't justify the benefit.

HBM Evolution: From HBM to HBM4

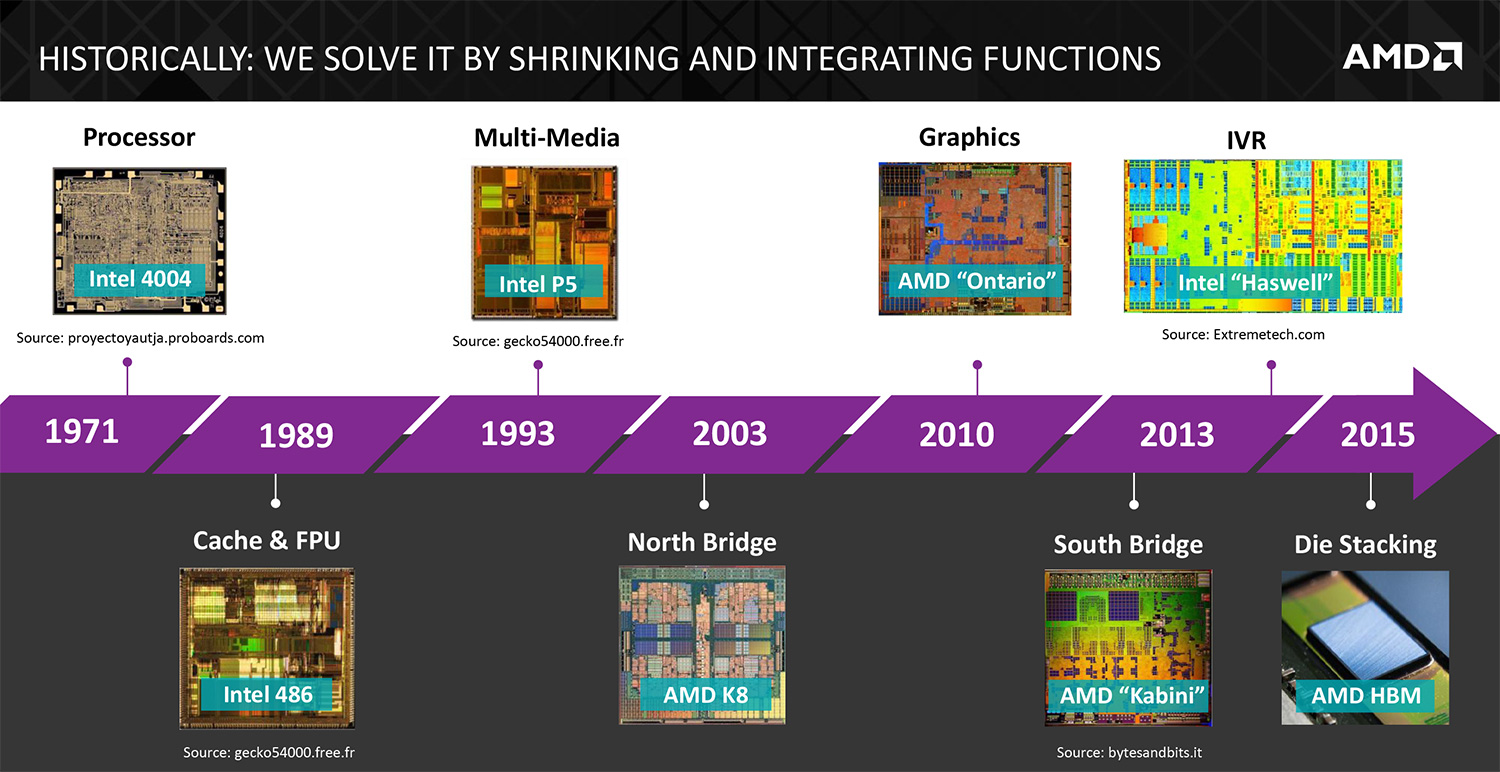

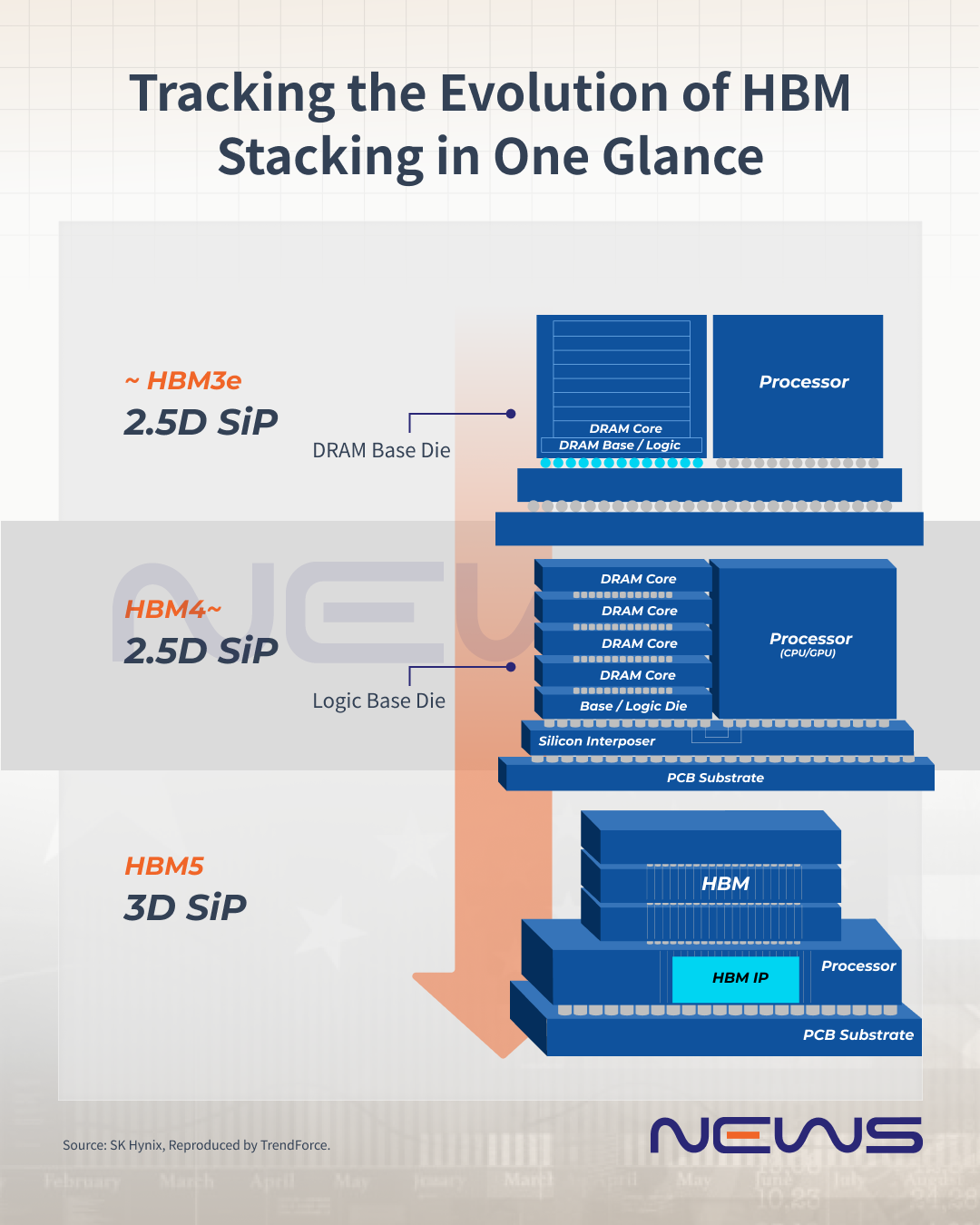

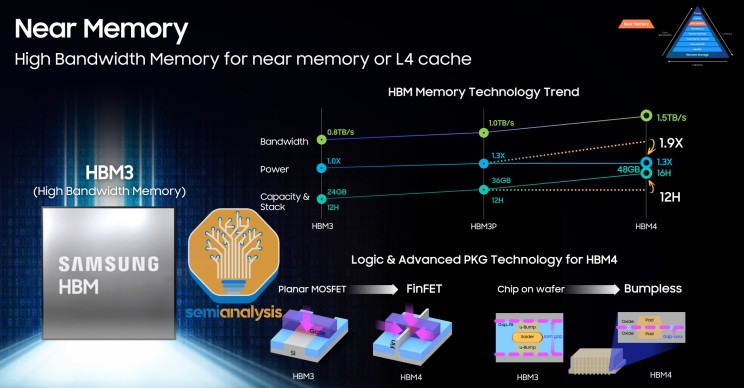

HBM emerged around 2015 as a research prototype. Samsung manufactured the first commercial stacks for AMD's GPUs. The technology was immediately appealing because it solved a real problem: data center memory was becoming a bottleneck.

HBM1 started with 128 pins. Bandwidth was around 100 GB/s. By HBM2, the industry doubled pin count and bandwidth, reaching 256 GB/s. HBM2E pushed this further with better signaling and denser stacking.

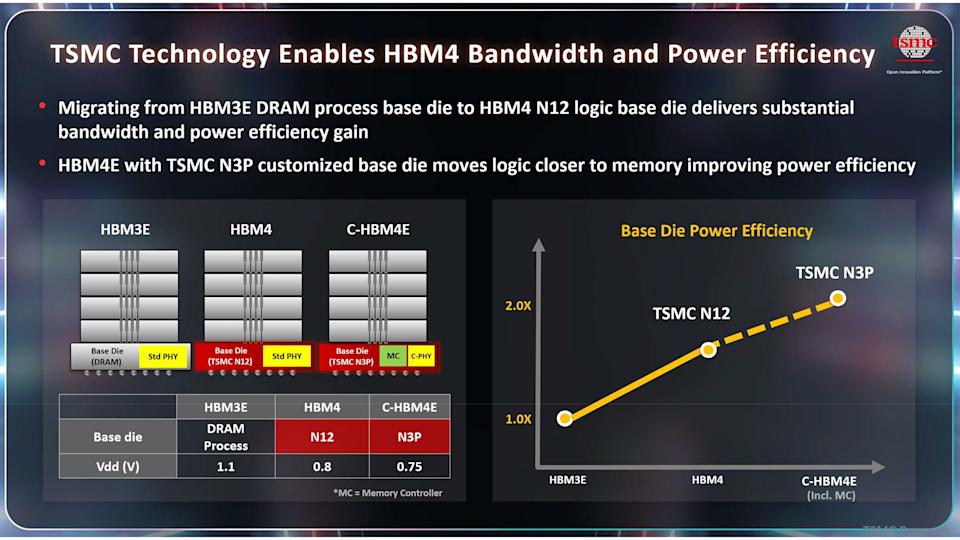

HBM3, released in 2021-2022, marked a massive jump. Pin count went to 1,024. Bandwidth reached 819 GB/s. This is where things got expensive. A silicon interposer supporting 1,024 pins requires extreme precision. Each bump pitch (the spacing between contacts) sits around 55 micrometers—roughly the width of a human hair.

Then came HBM4, which doubled everything again. 2,048 pins. 1.6-2.8 TB/s of bandwidth depending on clock speed and implementation. This is where Micron claimed the first 2.8 TB/s achievement in late 2024.

But here's the problem: doubling pin count doesn't just mean slightly higher costs. It means manufacturing becomes harder, substrate complexity increases, and the radius of companies that can actually afford to design systems around HBM4 shrinks further.

This is the market force that pushed JEDEC to pursue SPHBM4.

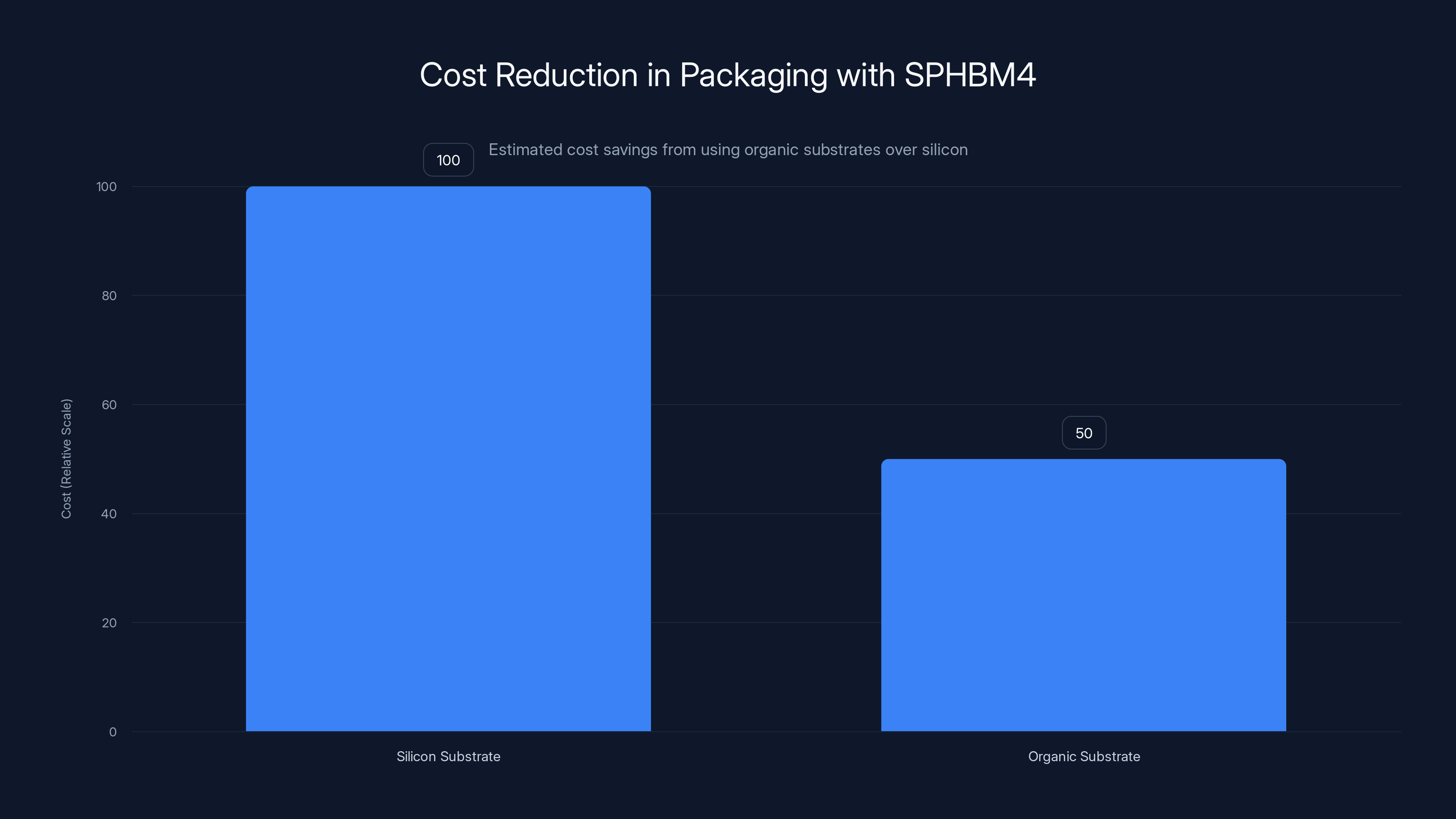

SPHBM4 technology reduces packaging costs by 30-50% due to the use of organic substrates instead of silicon, making it more economical for hyperscale AI deployments. (Estimated data)

SPHBM4: The Pin Count Problem Gets Inverted

The fundamental innovation in SPHBM4 is elegantly simple on its surface: use fewer pins, but push those pins harder.

HBM4 uses 2,048 pins. SPHBM4 proposes 512 pins. That's a 4:1 reduction in pin count.

Now, reducing pins by 75% would normally destroy bandwidth. But SPHBM4 implements 4:1 serialization at a higher signaling frequency. In practical terms: instead of moving data in four parallel channels, data is serialized into a single channel that moves four times as fast.

The math looks like this:

HBM4:

SPHBM4:

You end up with the same total bandwidth. The throughput per stack remains equivalent. But the physical and manufacturing requirements change dramatically.

Why does this matter? Because fewer pins mean wider spacing between them. HBM3's bump pitch is around 55 micrometers. HBM4 tightened this even further. SPHBM4, with only 512 pins, can work with bump pitches around 55-80 micrometers—still dense by consumer standards, but much more forgiving than HBM4.

That extra spacing allows a critical shift in substrate materials.

The Substrate Revolution: Silicon to Organic

This is where the real cost savings kick in.

HBM uses a component called an interposer—essentially a thin piece of silicon that sits between the stacked memory dies and the accelerator (GPU/TPU). This interposer routes all 2,048 (or in HBM4's case) electrical signals with incredible precision.

Silicon interposers are expensive. Why? Because they require the same manufacturing precision as cutting-edge processors. You're using photolithography equipment that costs tens of millions of dollars. Yields aren't perfect. A single defect in a routing layer can kill the entire die.

Due to silicon's structural strength and electrical properties, you can pack connections much more densely. But that density comes at a cost: both in capital equipment and in defect rates.

Organic substrates, by contrast, use the same materials as traditional printed circuit boards (PCBs)—but with much higher density than consumer electronics require. They're manufactured using standard PCB processes that are decades old, widely available, and cost a fraction of silicon interposer production.

The catch: organic substrates can't pack connections quite as densely. Routing channels are wider. Layers have more space between them. For HBM3 with its 1,024 pins and tight spacing requirements, organic substrates were technically impractical.

But SPHBM4's reduced pin count and wider spacing? Organic substrates work perfectly.

This shift from silicon to organic substrates could cut packaging costs by 30-50%, according to internal industry estimates. For a hyperscaler manufacturing millions of AI accelerators, that's hundreds of millions of dollars in savings.

Moreover, organic substrates allow longer channel lengths between the memory stacks and the accelerator's base logic die. HBM4 designs are physically constrained by the density of silicon interposers. SPHBM4 designs have more flexibility in physical layout, which means potentially more memory stacks per accelerator package and better thermal management.

Serialization and the Shift in Complexity

Here's a crucial point that often gets overlooked: SPHBM4 doesn't make the technology simpler overall. It shifts where the complexity lives.

With HBM4's parallel pins, the complexity sits in the interposer and packaging. You have thousands of simultaneous signals to route, and routing them with precision is a physical manufacturing problem.

With SPHBM4's serialization, the complexity moves into the signaling logic and the base logic die. Instead of moving data in parallel, you're deserializing 4:1 on both sides of the interface. That means more transistors, more signal processing, more timing constraints.

Base logic dies for SPHBM4 will need to be redesigned. They'll be slightly larger (more transistors), slightly more power-hungry (serialization logic consumes energy), and require more sophisticated timing analysis. But these are engineering problems that silicon designers have solved a thousand times. Tolerances are better understood. There's established tooling.

The result is a net win on system-level cost and complexity, even if component-level complexity increases.

This is a pattern you see throughout semiconductor design: as manufacturing becomes more challenging, complexity gets pushed to logic design where it's easier to iterate and optimize.

SPHBM4 achieves the same bandwidth per pin as HBM4 despite a 75% reduction in pin count by increasing the signaling frequency fourfold.

Bandwidth Preserved, Capacity Potential Increased

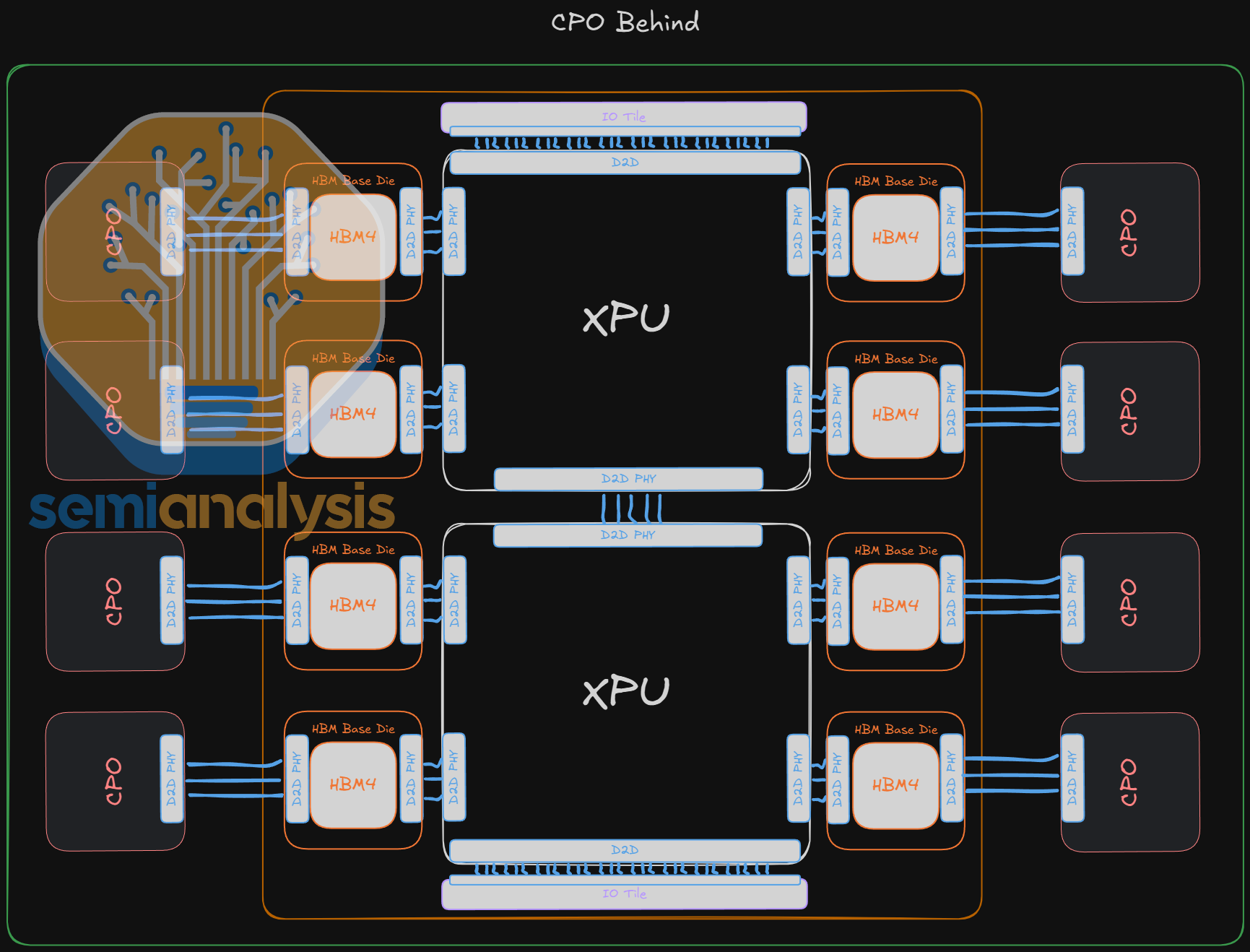

One of the most interesting aspects of SPHBM4 is that it potentially enables more memory stacks per accelerator than HBM4, despite using a smaller physical footprint per stack.

HBM4 is constrained by silicon interposer size. To route 2,048 pins with required signal integrity, the interposer needs to be fairly large. Multiple memory stacks on a single accelerator package create routing congestion—too many signals trying to share limited interposer real estate.

With organic substrates and longer allowable channel lengths, SPHBM4 designs can potentially mount more memory stacks in the same physical space or create denser multi-stack configurations.

Theoretical example: an HBM4 accelerator might support 6-8 memory stacks in a monolithic package. An equivalent SPHBM4 design might support 8-10 stacks, increasing total memory capacity from 96 GB to 160 GB, depending on stack density.

For large language model inference, memory capacity directly correlates to model size and batch size. The ability to fit larger models or serve more concurrent requests on a single accelerator translates directly to revenue efficiency for cloud providers.

This is particularly important for inference workloads, where multiple customers' requests might be batched together. Extra memory capacity can improve utilization by 15-25%, which compounds across millions of queries per day.

The Hyperscaler Economics: Where SPHBM4 Makes Sense

Let's talk about who actually benefits from SPHBM4 and why the economics matter.

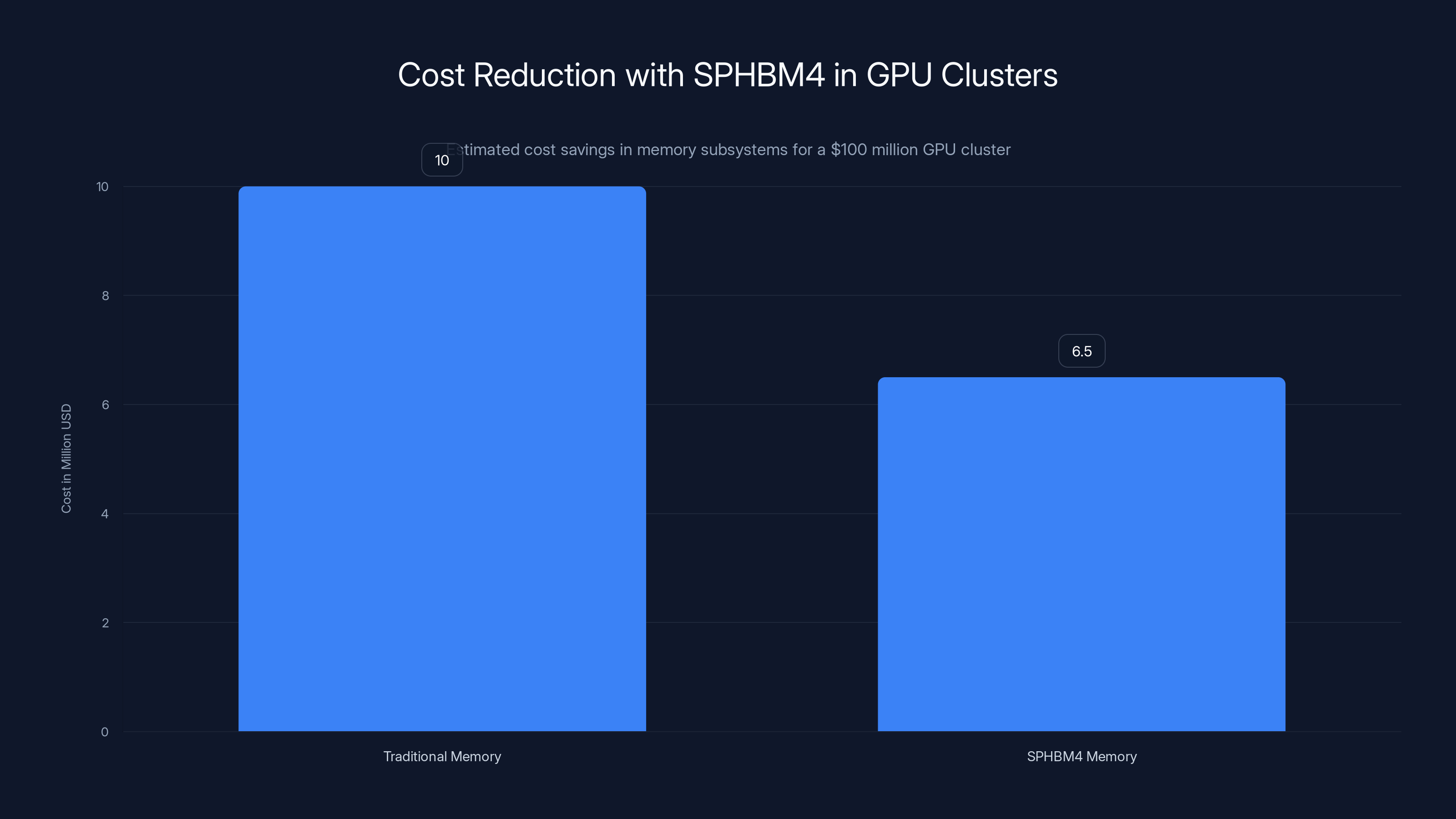

A single advanced GPU cluster for training large language models costs $50-200 million depending on model size and hardware choice. That includes GPUs, networking, storage, and memory subsystems.

Memory subsystems alone might represent 8-12% of that cost. For a

Now, SPHBM4 could reduce that cost to

That sounds small until you multiply it across a hyperscaler's infrastructure. Open AI reportedly operates over 100 supercomputer clusters. At

But there's another dimension: throughput efficiency. Organic substrates enable better thermal management and potentially higher clock speeds. If SPHBM4 enables even a 5% increase in effective throughput (through better cooling, higher clocks, or more stacks), that's equivalent to deploying 5% more hardware—another $500 million in capital avoided.

This is why every major memory manufacturer is already working on SPHBM4 implementations. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron have all signaled support for the standard.

And this is also why SPHBM4 remains locked in the hyperscaler world—because the economics only work at that scale.

Why SPHBM4 Won't Reach Consumer PCs (And That's Fine)

This is the question everyone asks: if SPHBM4 is cheaper, when does it come to gaming PCs or laptops?

The short answer: never. And that's not a limitation of the technology—it's a fundamental architecture mismatch.

Consumer memory is based on DIMMs (Dual Inline Memory Modules). You plug them into a motherboard slot. They're standardized. Every motherboard from the past 20 years can use newer DRAM if the form factor matches.

HBM—all variants, including SPHBM4—is soldered directly to an accelerator's substrate. It's not meant to be removable or user-upgradeable. The base logic die is tightly integrated with the accelerator's main processor.

Moreover, HBM economics don't scale to consumer applications. A

For that price increase to make sense, the GPU would need to be 50% faster for the specific workloads consumers care about (games, content creation, etc.). But gaming doesn't need 1.6 TB/s of bandwidth. It's happy with 300 GB/s.

Furthermore, consumer motherboards would need completely redesigned power delivery and signal integrity systems to support HBM. Every DIMM slot would become incompatible. The ecosystem disruption would be enormous.

The market forces that created HBM in the first place—massive data center demand, willingness to pay for performance, standardized deployment patterns—simply don't exist in the consumer space.

SPHBM4 doesn't change this equation. It makes HBM cheaper, but it doesn't make it cheaper than DRAM. It optimizes hyperscale deployments, not consumer systems.

Anyone telling you that cheaper HBM means consumer PCs with HBM is misunderstanding either the technology or the economics.

SPHBM4 can reduce memory subsystem costs from

Base Logic Die Redesign: The Hidden Engineering Challenge

One aspect of SPHBM4 that deserves more attention is base logic die redesign. This is where the complexity actually lies.

Every HBM stack includes a base logic die—a small processor that handles serialization/deserialization, clock distribution, voltage regulation, and error correction. It's the bridge between the memory stack and the accelerator.

For HBM4, base logic dies are optimized around 2,048 parallel pins. The logic needed to manage that many simultaneous signals is complex but fundamentally parallel in nature.

For SPHBM4, with 512 pins and 4:1 serialization, base logic dies need different optimization. The logic is simpler in pin count but more complex in timing constraints. You're serializing data at 40 GHz instead of 10 GHz—four times the clock speed creates four times the timing margin requirements.

High-speed serialization logic requires careful attention to:

- Signal integrity: Reflections, crosstalk, impedance matching become critical at 40 GHz

- Clock distribution: Clocking millions of flip-flops at high frequency requires precision phase-locked loops and careful routing

- Power delivery: Higher clock speeds mean higher dynamic power consumption; voltage delivery must be rock-solid to maintain timing margins

- Temperature stability: Frequency variations with temperature can break timing margins; thermal monitoring and compensation become necessary

Base logic die design is a specialized field. Most accelerator makers (NVIDIA, AMD, custom ASIC teams at hyperscalers) have experienced teams here. But transitioning from HBM4 to SPHBM4 isn't a trivial design change. It's probably a 6-9 month engineering effort per team, maybe longer if they're pushing for performance optimizations.

This is one reason why adoption might lag: not because the technology is new (JEDEC announced this years ago), but because the engineering work is substantial and carries schedule risk for teams working on tight deployment deadlines.

Manufacturing and Yield Implications

Here's something manufacturers care about deeply: yield rates.

With HBM4's silicon interposers and 2,048-pin density, a single routing defect can kill the entire interposer. Defect rates are measured in parts per million, and yield is a constant tension between pushing density and maintaining acceptable production rates.

Organic substrates, made with established PCB processes, have better inherent yield. They use larger design rules (wider traces, bigger vias, more spacing), and the manufacturing processes are more mature.

For SPHBM4, early yield should be higher than comparable HBM4 designs, which means faster production ramp and faster cost reduction as you move down the learning curve.

This is another win for hyperscalers: faster to production means faster to deployment means faster amortization of design costs.

However, there's a countervailing force: 40 GHz signaling is harder to validate than 10 GHz signaling. Testing requires more sophisticated equipment. Characterization takes longer. So while manufacturing yield might improve, the engineering and testing phase might take longer to complete.

Net effect: first SPHBM4 products will probably be 2026-2027 at the earliest, with volume production in 2027-2028.

Integration with Accelerator Architectures

Accelerator design—the GPU or TPU architecture that sits next to the SPHBM4 memory—will need modifications to work optimally with the new memory interface.

NVIDIA's architecture is particularly memory-aware. The entire L1/L2 cache hierarchy, the on-chip network, the memory request scheduler—all of it is optimized around HBM3 and HBM4 characteristics. Switching to SPHBM4 means redesigning these subsystems.

Some of the design goals remain the same: maximize bandwidth utilization, minimize memory access latency. But the constraint profile changes.

For example, HBM4's parallel pins mean lower access latency—you can request data from multiple channels simultaneously with less contention. SPHBM4's serialization means higher latency for random access patterns but similar latency for sequential patterns (which are more common in deep learning workloads).

Accelerator architects will need to optimize instruction scheduling, cache line sizes, and memory access patterns to work best with SPHBM4's characteristics. This is exactly the kind of work teams like NVIDIA's architecture group specialize in, so it's achievable—but it's real engineering effort.

The payoff is worth it: better memory utilization could translate to 5-10% effective performance gains on real workloads, which compounds across the fleet.

HBM offers significantly higher bandwidth than traditional DRAM, reaching over 500 GB/s, while SPHBM4 pushes this further to 600 GB/s with advanced signaling techniques. Estimated data.

Competitive Dynamics: Why JEDEC Pushed This Standard

Let's step back and ask why JEDEC even developed SPHBM4. Was it driven by market demand? Regulatory pressure? Engineering elegance?

Actually, it's mostly about competitive dynamics and design freedom.

Without a standard, each manufacturer (Samsung, Hynix, Micron) would develop proprietary solutions to reduce HBM costs. That fragmentary approach would make it hard for accelerator designers to optimize for multiple suppliers' solutions. You'd end up with inefficient designs that work with all suppliers but optimize for none.

With a standard, accelerator designers can write one design that works across multiple suppliers' SPHBM4 implementations. Suppliers compete on cost and yield, not on proprietary optimizations. System designers win because they have choice and can negotiate better pricing.

JEDEC, which includes all the major manufacturers and major system designers (NVIDIA, AMD, hyperscalers), creates standards that reduce friction and unlock mutual benefit.

It's similar to how DDR DRAM standards work: Intel, AMD, and others agree on a specification so DRAM suppliers compete on cost and quality, not on incompatible designs.

For SPHBM4, this standardization likely accelerates adoption by 1-2 years compared to proprietary solutions. That's significant in semiconductor terms.

Timeline and Adoption Curve

So when will SPHBM4 actually be deployed at scale?

Based on typical semiconductor development cycles:

- 2024-2025: Detailed design work, silicon validation, preliminary yield ramp

- 2026: First production samples from at least one supplier (probably Micron)

- 2026-2027: Accelerator makers integrate into next-gen designs, validation testing

- 2027-2028: Volume production ramps, new accelerators reach deployment

- 2028-2030: SPHBM4 becomes the dominant HBM form factor for new deployments

Legacy HBM4 designs will continue in production because accelerators are long-lived products (3-5 year deployment life). So you'll see a transition period where both HBM4 and SPHBM4 coexist, probably through 2032 or later.

Full industry transition: probably 2030-2032.

This matters because it means the cost benefits of SPHBM4 won't fully impact hyperscaler economics until 2029-2030. That's still meaningful (4-5 year horizon is how capital budgets work), but it's not immediate.

The Broader Implication: Memory Won't Be the Bottleneck Forever

Here's the big-picture insight: SPHBM4 is a symptom of a deeper trend.

Memory is becoming a capital and complexity constraint on AI scaling. It's not the only constraint (power, cooling, interconnect all matter), but it's a significant one. Over the next five years, we'll see multiple simultaneous innovations:

- SPHBM4 reducing cost and complexity

- New memory technologies like all-to-all interconnect memory from Samsung

- Chiplet-based memory architectures that mix HBM and standard DRAM

- Hybrid architectures that adapt memory technology to specific workload requirements

None of these will make HBM "cheap" in absolute terms. But they'll make HBM more accessible to smaller-scale deployments (enterprise data centers, research institutions, cloud providers beyond the "super-hyperscalers").

This cascading effect is important: as memory economics improve, entire system designs become possible that previously weren't viable. You might see mid-tier AI accelerators that use SPHBM4 memory because it's cheaper, enabling a new market segment.

Not consumer PCs. But maybe enterprise inference servers. Maybe research clusters. Maybe edge deployment systems that need serious bandwidth but can't justify hyperscale infrastructure costs.

SPHBM4 is a door opener, even if the door is still restricted to a pretty exclusive club.

The Supply Chain Question: Can Manufacturers Actually Scale?

There's a practical constraint that often gets overlooked: supply chain capacity.

Organic substrate manufacturing requires PCB suppliers who specialize in high-density interconnect (HDI). Major players include companies like Ibiden, Unimicron, and others. These are not companies that typically serve the cutting-edge semiconductor market—they're focused on consumer electronics, automotive, and enterprise systems.

Scaling organic substrate manufacturing to support hyperscale HBM demand requires investment. Suppliers need to build new fabs, train engineers in semiconductor-grade process control, and invest in equipment rated for aerospace/military-grade reliability (which hyperscalers require).

This isn't a blocker—PCB suppliers have the capability—but it's a real constraint on adoption rate. You probably won't see unlimited SPHBM4 supply until 2027-2028, even if the designs are ready in 2026.

Hyperscalers are already thinking about this. Many are probably committing to suppliers and guaranteeing demand to secure allocation. It's the same pattern we saw during the GPU shortage: whoever secured the supply first got the most value.

Looking Forward: The Path Beyond SPHBM4

SPHBM4 is a refinement, not a revolution. It optimizes the HBM approach, but it's still based on the same fundamental architecture: stacked DRAM dies with a parallel interface.

The next major shift might be something different: memory with built-in compute, or memory that uses different physical principles (photonic interconnects, 3D chiplet stacks, etc.).

But that's years away. SPHBM4 is what we'll be living with for the next half-decade. It's worth understanding, not because it's revolutionary, but because it's pragmatic engineering in service of the most important computing problem of our time: making AI infrastructure affordable enough to keep scaling.

And that matters more than most people realize.

FAQ

What does SPHBM4 stand for and what is it?

SPHBM4 stands for Standard Package High Bandwidth Memory 4. It's a memory standard developed by JEDEC that reduces the physical pin count of HBM from 2,048 pins (HBM4) to 512 pins while preserving total bandwidth through 4:1 serialization at higher signaling frequencies. This allows the use of cheaper organic substrates instead of expensive silicon interposers, significantly reducing packaging costs for hyperscale AI deployments.

How does SPHBM4 maintain bandwidth with fewer pins?

SPHBM4 uses 4:1 serialization, meaning data that would normally be transmitted across four parallel pins is instead serialized into a single pin operating at four times the signaling frequency. An HBM4 system operates at roughly 10 GHz across 2,048 pins; SPHBM4 operates at roughly 40 GHz across 512 pins. The total data throughput remains equivalent, but the physical and manufacturing requirements change dramatically, enabling cost reductions of 30-50% on packaging.

What's the difference between silicon and organic substrates?

Silicon substrates are made from crystalline silicon and support extremely dense interconnect routing (55-micrometer pitch) but require expensive photolithography equipment and have lower yields. Organic substrates use PCB-like materials with wider routing pitch (55-80 micrometers) but are manufactured using mature, widely available processes at lower cost. SPHBM4's reduced pin count enables the use of organic substrates, cutting packaging costs significantly.

Will SPHBM4 technology come to consumer PCs?

No. SPHBM4 remains specialized stacked memory designed for direct integration with accelerators. Consumer systems use DIMMs, which are standardized pluggable modules. HBM in any form is economically impractical for consumer applications because the cost-to-performance benefit doesn't justify the price increase for typical consumer workloads like gaming or content creation. Cheaper SPHBM4 still costs significantly more than standard DRAM per gigabyte.

Who is developing SPHBM4 products?

All major DRAM manufacturers are developing SPHBM4 implementations, including Micron, Samsung, and SK Hynix. These companies are JEDEC members and have already committed to the standard. Accelerator makers like NVIDIA and AMD are also designing next-generation systems to support SPHBM4 interfaces. The first production samples are expected in 2026, with volume ramps in 2027-2028.

What are the main advantages of SPHBM4 over HBM4?

The primary advantages are reduced packaging costs (30-50% potential savings through organic substrate use), improved thermal management, potential for more memory stacks per accelerator package, and faster manufacturing yield due to less demanding tolerances. These benefits translate to 3-5% system-level cost reductions for hyperscale AI deployments, which compounds to billions of dollars across major infrastructure operators.

Does SPHBM4 require accelerator redesign?

Yes, accelerators will need redesigned memory controllers and base logic dies to support SPHBM4's higher signaling frequencies and serialized interface. This is not a trivial change but is achievable with established engineering practices. The redesign effort is typically 6-9 months for experienced architecture teams and is offset by the cost savings and potential performance improvements from optimized memory hierarchies.

When will SPHBM4 be widely deployed?

Based on typical semiconductor development cycles, first production samples are expected around 2026, integration into accelerators during 2026-2027, and volume deployment beginning 2027-2028. Full industry transition from HBM4 to SPHBM4 will likely take until 2030-2032, as older HBM4 designs continue production through their lifecycle. The cost benefits will be felt most significantly by 2029-2030.

Why didn't manufacturers just develop SPHBM4 proprietary solutions?

A standardized approach through JEDEC provides multiple benefits: accelerator designers can optimize once and work with multiple suppliers, suppliers compete on cost and quality rather than proprietary features, and faster adoption across the industry. Proprietary solutions would fragment the market and make system design more complex. Standards are particularly valuable in memory because they enable supply chain competition and reduce design risk.

What happens to the complexity that comes from fewer pins?

The complexity shifts from packaging and interposer design (physical manufacturing challenges) into base logic die design and signal integrity (engineering challenges that are well-understood). This is generally a favorable trade because logic design can be iterated quickly with simulation tools and is more forgiving of design changes, whereas physical manufacturing constraints are hard to change once production starts. It's a pattern throughout semiconductor design: push complexity toward logic when possible.

Key Takeaways

- SPHBM4 uses 512 pins with 4:1 serialization to match HBM4's bandwidth while dramatically reducing packaging complexity and cost

- Organic substrate manufacturing replaces expensive silicon interposers, cutting packaging costs by 30-50% and enabling tighter hyperscaler economics

- SPHBM4 preserves HBM's specialized nature; it won't reach consumer markets because the technology and economics don't translate below hyperscale deployment

- Major memory suppliers (Micron, Samsung, SK Hynix) are developing SPHBM4 implementations with first production expected 2026 and volume deployment 2027-2028

- Base logic die redesign and accelerator integration are non-trivial but achievable engineering challenges that will occur in parallel with memory development

- Supply chain scaling in organic substrate manufacturing is a practical constraint on adoption rate, likely limiting rapid scaling until 2027-2028

- SPHBM4 represents pragmatic optimization of hyperscale AI infrastructure costs; future innovations will likely push toward even more specialized memory architectures