The Year AI Slop Became the Internet's Default Setting

You're scrolling through search results, clicking on what looks like a legitimate article, and 30 seconds in you realize it's garbage. The writing is technically correct but says absolutely nothing useful. The examples feel generic. The entire piece exists only to rank for keywords and get clicks. Welcome to 2025, the year AI slop won.

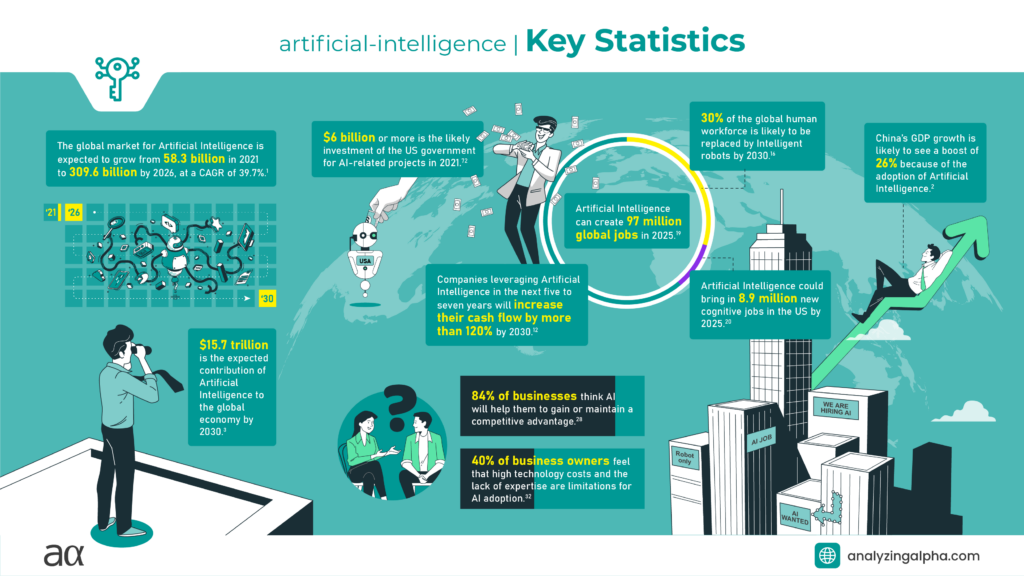

This isn't speculation or pessimism. By late 2024 and into 2025, the floodgates opened. What started as occasional AI-generated blog posts and rushed content marketing became the dominant force in search results, social feeds, and recommendation algorithms. Companies realized they could generate unlimited content at near-zero cost, and the incentives suddenly aligned perfectly for quantity over quality.

The problem isn't that AI tools themselves are bad. Tools like Runable use AI to help teams create presentations, documents, and reports that save hours of manual work. The difference is intentionality. A team using AI to accelerate legitimate work is fundamentally different from someone dumping 10,000 AI-generated articles onto the internet for SEO purposes.

But here's what makes 2025 the turning point: the internet became noticeably worse. Researchers found that search results were increasingly unhelpful. Reddit threads felt synthetic. News articles lacked investigation. The signal-to-noise ratio collapsed so catastrophically that serious information consumers had to fundamentally change how they find reliable content.

This isn't a small niche problem. It's an existential threat to digital information ecosystems.

By late 2025, one question started dominating tech conversations: how do we prove that something was actually written by a human? How do we authenticate content in an age where generation became cheaper than verification?

The answer that emerged? Content fingerprinting. And it might be the only thing that can save us.

TL; DR

- The Scale of the Crisis: By 2025, AI-generated low-quality content ("AI slop") became the dominant type of content on the internet, with search results increasingly filled with unhelpful, generic articles created solely for SEO purposes

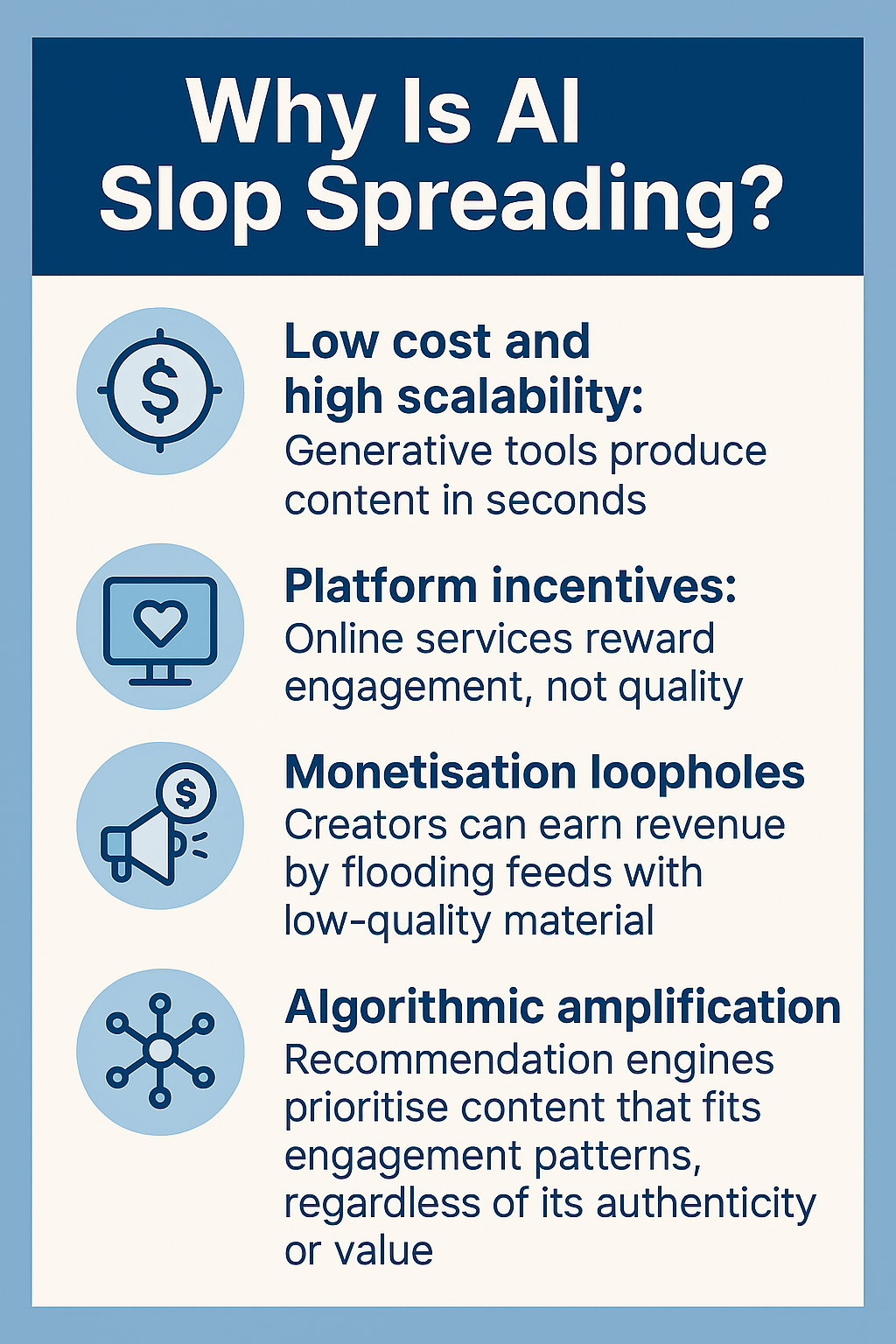

- Why It Happened: The economics perfectly aligned: AI generation costs dropped to near-zero while the potential revenue from cheap content remained significant, creating unstoppable incentives to flood the internet

- The Real Cost: Users lost trust in traditional information sources, the signal-to-noise ratio on search collapsed, and legitimate creators found their work buried under mountains of synthetic content

- The Fingerprinting Solution: Content fingerprinting could authenticate human-created work through cryptographic signatures, making it verifiable that specific content was authored by real humans at specific times

- What Comes Next: 2026 will likely see the emergence of authentication standards, browser-level verification tools, and possibly regulatory frameworks that separate authentic content from generated content

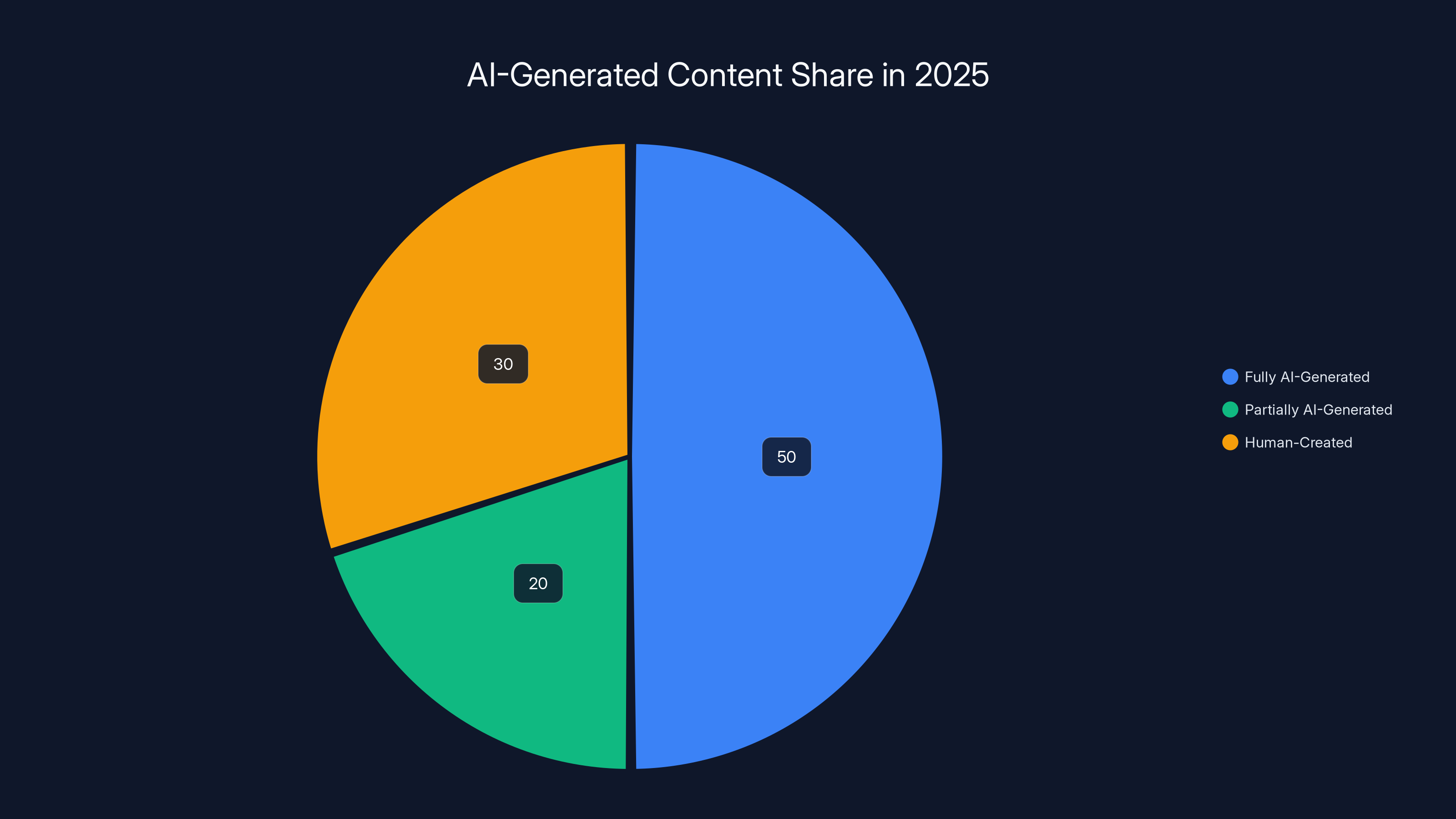

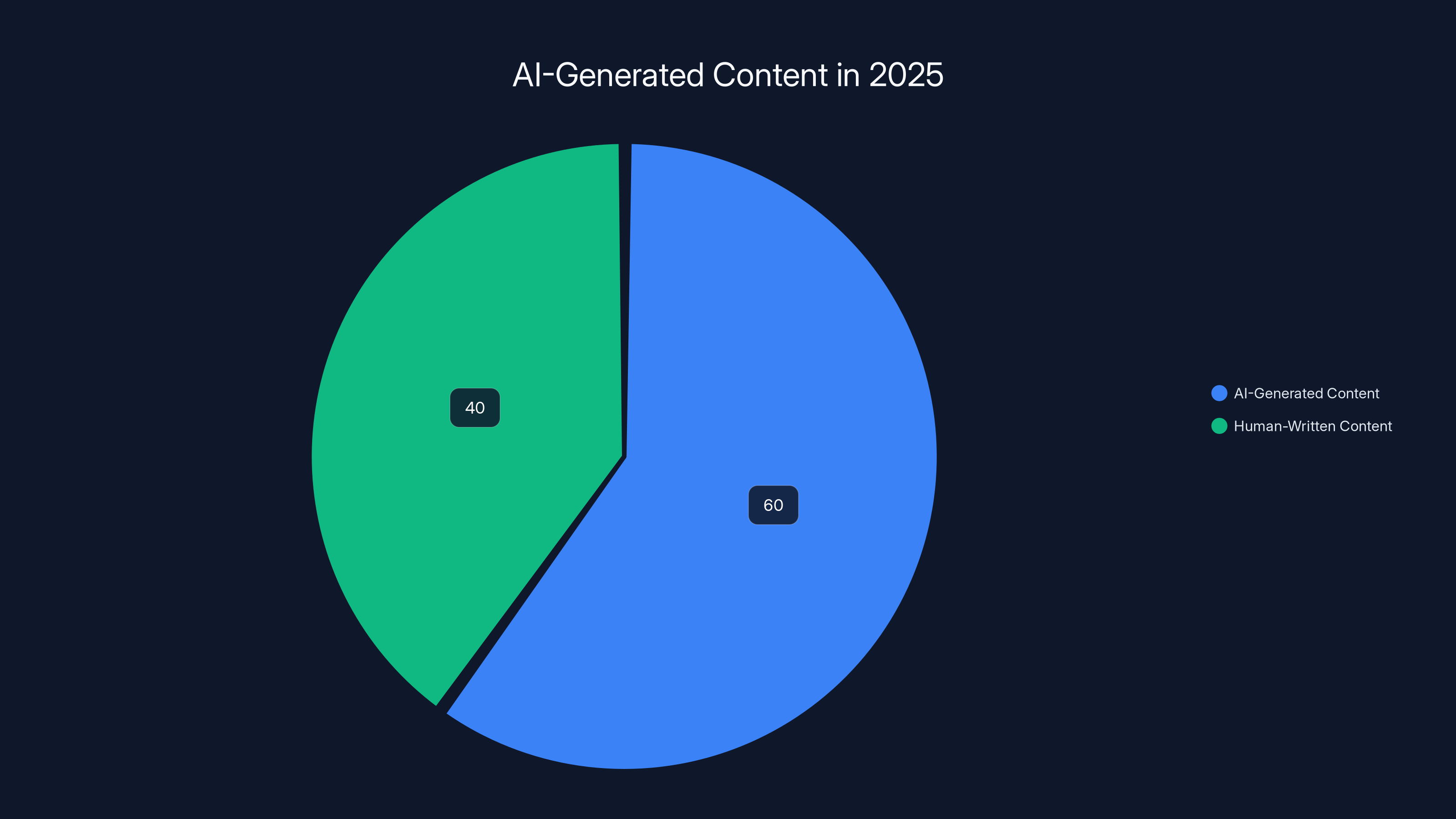

By Q3 2025, it was estimated that 50% of new content indexed by search engines was fully AI-generated, with an additional 20% being partially AI-generated. This highlights the significant impact of AI on content creation. (Estimated data)

How AI Slop Actually Won in 2025

Let's be honest: nobody woke up in January 2025 with a master plan to ruin the internet. It was worse than that. It was inevitable.

The economics are brutally simple. Creating a 2,000-word article used to require hiring a writer. That writer needed health insurance, benefits, and probably expected

Then AI generation hit critical mass. By 2025, you could generate an article in seconds. The cost? Maybe a fraction of a cent in computing power if you were using efficient models. The potential return? Hundreds of dollars from Ad Sense, affiliate links, or direct sponsorships if the article ranked.

The math was so wildly asymmetrical that the only rational decision became generating as much content as possible. One successful article making

Search algorithms actually accelerated this. Google, Bing, and other search engines use freshness as a ranking signal. Publish content frequently, and you get rewarded with visibility. The algorithm doesn't distinguish between "frequently updated with genuine new information" and "frequently spammed with new garbage." So the incentive became clear: pump out content constantly.

The tipping point came when AI tools became good enough that most people couldn't immediately tell they were looking at generated content. Not perfect, but good enough. You'd read a paragraph and think, "Yeah, this makes sense," without realizing it was assembled from patterns in training data rather than actual knowledge or research.

What really broke the internet, though, was aggregation. SEO agencies and content mills realized they didn't need original ideas. They could generate the same article thousands of times with minor variations. They could target "best pizza in [city]" for every city on Earth. They could create "[brand] review" articles for products they'd never touched.

The sheer volume was unprecedented. Not hundreds of thousands of articles. Not millions. Billions of pieces of synthetic content, most of them indistinguishable from legitimate content to automated systems.

Google eventually acknowledged the problem in mid-2025, announcing changes to how they'd rank AI-generated content. But the damage was already done. The internet's information ecosystem had collapsed. Trust had eroded. Users were exhausted.

The Real Casualties: Who Actually Lost

Here's something people don't talk about enough: the winners in 2025 weren't the ones flooding the internet with slop. They were the ones who didn't care about search rankings at all.

Think about that for a second.

Reddit's traffic exploded in 2025 because people were so desperate for authentic human perspectives that they'd wade through a sprawling forum full of anonymous users just to find one genuine opinion. Why? Because Reddit traffic came from humans, not bots. The content was unfiltered, unoptimized, and genuinely unhelpful sometimes, but it was real.

Substack writers saw explosive growth. Why? Because you knew it was a real person writing about something they actually cared about. Same with Discord communities, Telegram channels, and even traditional media outlets that could afford to invest in real reporting.

The actual losers were:

Legitimate SEO professionals who built careers on creating quality content and optimizing it properly. By 2025, their work had become nearly impossible. How do you rank a 3,000-word research article against a competitor who generates 30,000 variations of AI content? You can't.

Small publishers and blogs that had built loyal audiences over years. Many discovered their traffic was down 40-60% by 2025, replaced by AI-generated competitors who didn't care about long-term audience trust.

Journalists and investigative reporters who discovered their work being quoted, summarized, and redistributed by AI systems that never linked back or created citation trails. Your original reporting became training data for systems that competed with you.

Academic researchers found their published papers being digested and regurgitated by content generators in minutes, often misrepresented or contradicted.

Users themselves lost something intangible but critical: trust. Every search felt like a gamble. Every article required verification. The mental load of information consumption doubled while the confidence in finding reliable answers halved.

Larger publications with brand recognition held up better because people trusted the masthead, not the search ranking. But the long tail of the internet—the thousands of niche blogs, expert sites, and community forums that Google used to surface—got buried.

By mid-2025, an estimated 60% of new content indexed by search engines was AI-generated, highlighting the significant impact of AI slop. Estimated data.

The Technical Collapse: Search Becomes Useless

By mid-2025, something remarkable happened: Google search basically stopped working for informational queries.

Type in a question, and you'd get back results from:

- AI-generated listicles that plagiarized top results

- Content farms that generated articles for every possible keyword variation

- Scraped content from legitimate sites with minor rewriting

- Articles optimized for keyword density rather than comprehensiveness

- Affiliate spam dressed up as reviews

But you wouldn't get the original research, the expert opinion, or the authoritative source.

This created a bizarre inversion. The more search engines tried to crack down on low-quality content, the more sophisticated the spam became. Spammers hired AI models to improve readability. They added more citations (to other spam). They created entire networks of interlinking sites to build authority signals.

It became a technical arms race that users didn't sign up for.

The real problem? Search algorithms rely on popularity signals. Links, clicks, dwell time, and shares. But AI-generated content was good enough at gaming these signals. A sufficiently optimized piece of garbage would attract clicks from people trying to find information. Those clicks would signal to the algorithm that the content was relevant. The algorithm would rank it higher. More people would click. The signal reinforced itself.

By the end of 2025, Google search was genuinely worse than typing your query into Reddit or Discord. Not because those platforms had better content, but because they had actual humans discussing actual problems. The signal was noisier but more authentic.

This forced a reckoning. If search results can't be trusted, what's the point of SEO? If content can't be verified, how do you evaluate sources? If authorship is fake, how do you attribute expertise?

These aren't rhetorical questions. They're the fundamental problems that content authentication needed to solve.

What Content Fingerprinting Actually Is (And Why It Matters)

Content fingerprinting isn't a new concept, but its application to the AI slop problem represents a potential breakthrough.

At its core, fingerprinting is a cryptographic technique for creating a unique, verifiable signature for a piece of content. Think of it like a digital fingerprint: every person's fingerprint is unique and extremely difficult to forge. A content fingerprint works similarly.

Here's how it would work in practice:

Step 1: Author Verification A content creator (journalist, blogger, researcher) creates an article and publishes it through a system that supports fingerprinting. The system captures metadata: the author's identity, the publication time, the exact content, and any sources cited.

Step 2: Cryptographic Signing A cryptographic algorithm creates a unique hash—a fingerprint—based on the content and metadata. This hash is mathematically impossible to replicate without the exact same inputs. Even changing one word in the article would create a completely different fingerprint.

Step 3: Immutable Record The fingerprint gets recorded on an immutable ledger (could be a blockchain, could be a distributed database, could be a simple server maintained by a trusted authority). This creates a permanent, timestamped record of "this specific content, by this specific author, at this specific time."

Step 4: Verification When a user encounters the content online, they could verify its authenticity. A browser extension, integrated search result, or dedicated tool could check: "Does this content's fingerprint match the record? Is the author who they claim to be? Has the content been modified since publication?"

Step 5: Trust Signal Authenticated content gets marked with a badge or indicator. Over time, users learn to trust fingerprinted content more than unverified content. Publishers get incentivized to implement fingerprinting because it gives them a competitive advantage.

The genius here is that it doesn't require AI detection. You don't need to build an AI detector to figure out if something was generated. You just need to verify that the person claiming authorship actually created it at the time they claim.

Why is this better than AI detection? Because AI detection is a losing game. Every AI detector will be bypassed by better AI. But cryptographic verification is mathematically sound. If the fingerprint matches, the content is authentic. If it doesn't match, something's wrong. No ambiguity.

The Technical Implementation Problem

Sounds great, right? Authenticate content, regain trust, and the problem's solved.

Not quite.

The technical challenges are actually significant, and they're why fingerprinting didn't become standard practice earlier.

The adoption problem: For fingerprinting to work at scale, you'd need widespread adoption. Publishers, platforms, search engines, and browsers would all need to support it. Getting consensus on a technical standard is notoriously difficult. The internet has spent 20+ years trying to get everyone to use HTTPS, and we still have unsecured sites everywhere.

The centralization dilemma: Who maintains the ledger of fingerprints? If it's a single company, that company becomes a gatekeeper (and a target for hacks). If it's decentralized, you need consensus mechanisms, which are slow and complex. If it's federated, you need standards that don't exist yet.

The retroactivity gap: Fingerprinting only works for content created after the system launches. The billions of articles already on the internet can't be verified. You'd have a two-tier system: authenticated new content and unverifiable old content. Users would still distrust the old stuff.

The false positive problem: What if someone legitimately reuses content? What if a newspaper republishes their own article on different sites? What if a researcher quotes extensively from a study? The fingerprinting system would flag legitimate republication as tampering.

The mobile and social problem: Most internet usage happens on mobile apps and social platforms that don't have browser extensions or integrated verification. How would fingerprinting work in a Tik Tok caption or a Twitter link? The systems aren't designed to support it.

The AI-generated content loophole: Here's the uncomfortable truth: fingerprinting doesn't actually prove a human wrote something. It proves that someone with access to the author's credentials created it at a certain time. But if a human used AI to write it, the fingerprint still shows it as human-created. You're not solving the core problem; you're just making unauthorized copying harder.

These aren't small problems. They're fundamental architectural challenges that require solving before fingerprinting becomes viable at internet scale.

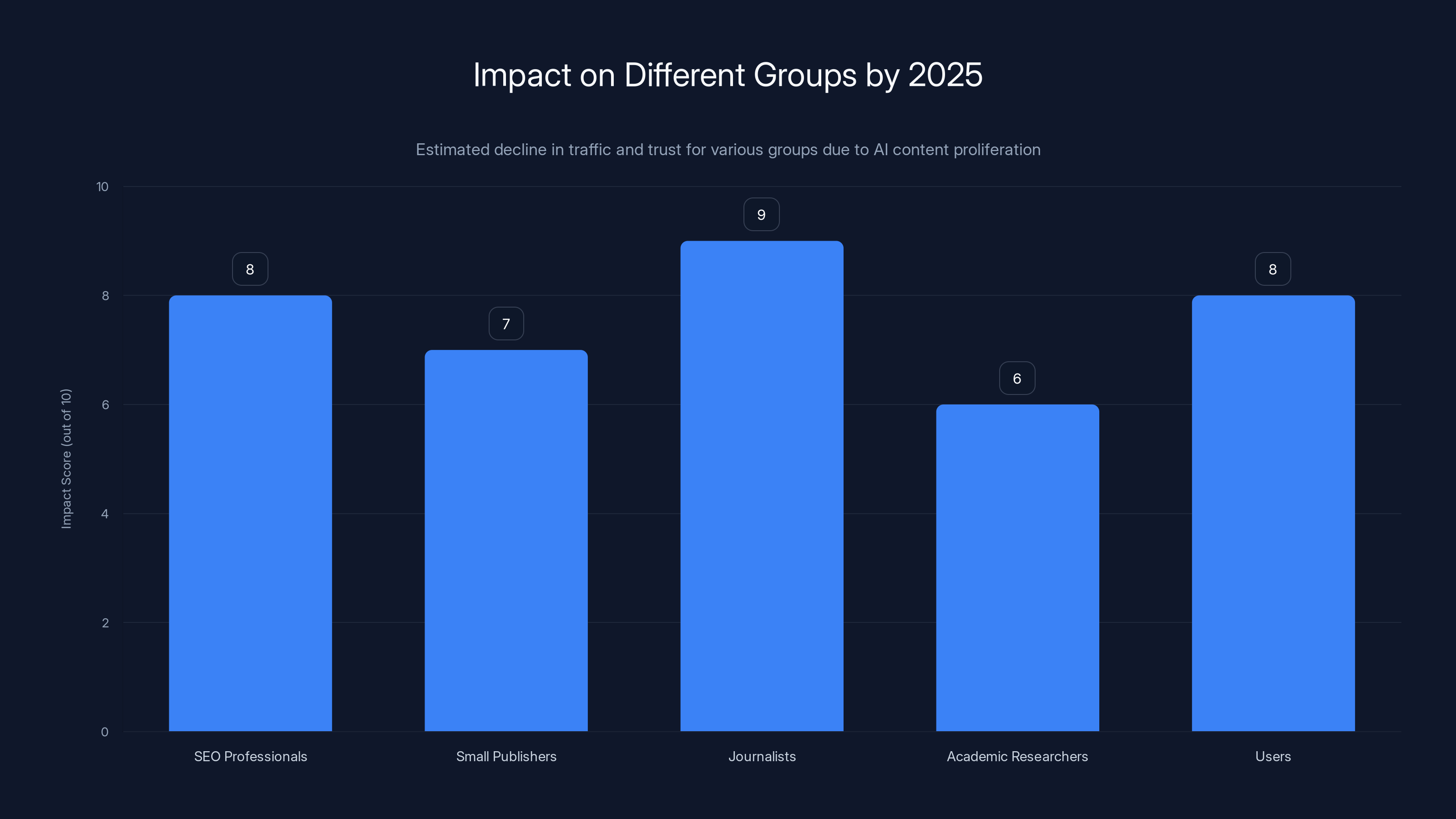

Estimated data shows that journalists and SEO professionals faced the highest impact from AI content proliferation by 2025, affecting their traffic and trust significantly.

The Blockchain Solution (And Why It Probably Won't Work)

Obviously, once someone mentioned cryptographic verification, people started talking about blockchain.

This is where I need to be direct: blockchain probably isn't the answer for this specific problem, despite its appeal.

Here's the thing: blockchain is great for decentralization, immutability, and consensus. But it's bad for speed, efficiency, and mainstream adoption. And for content fingerprinting, you don't actually need decentralization. You need security and auditability.

The energy problem: Putting every published article on a blockchain that requires proof-of-work would consume absurd amounts of electricity. Proof-of-stake is better, but you're still adding significant computational overhead to every publication.

The scalability problem: Current blockchains process tens of thousands of transactions per second at best. The internet publishes millions of pieces of content daily. You'd need a blockchain specifically designed for this use case, which means it's not a generic solution—it's a custom network with all the adoption problems mentioned earlier.

The UX problem: Most people can't explain blockchain, let alone verify cryptographic signatures on it. The authentication mechanism would be invisible to end users, which is good. But the underlying infrastructure would be brittle, and when something breaks (and it will), average users can't fix it.

The incentive problem: Why would miners or validators care about maintaining a blockchain for content fingerprinting when they could make more money securing financial transactions? You'd need significant economic incentives, which means someone pays—probably the users or publishers who want to use the system.

That said, blockchain could work for specific use cases. News organizations could have a shared blockchain for verifying publication timestamps. Academic papers could be fingerprinted on a dedicated blockchain run by universities. The Financial Times could verify their articles are genuine against their own blockchain-based ledger.

But internet-scale content fingerprinting? The infrastructure would need to be simpler, faster, and more aligned with how the internet actually works.

The "Trusted Authority" Model That Might Actually Work

When blockchain fails as a solution, the next option is usually a centralized authority. And while that sounds dystopian, it might actually be pragmatic.

Imagine a system that works like this:

A nonprofit organization (or consortium of publishers) runs a fingerprint registry. It's not blockchain; it's just a massive database. When you publish content, you submit it to the registry along with cryptographic proof that you control your author account. The registry time-stamps it, assigns a unique identifier, and publishes the fingerprint.

This fingerprint could be embedded in articles as metadata (a small tag in the HTML or document). When someone wants to verify content, they check the registry: "Does this article's fingerprint match what was published?"

Benefits:

- Simple: No blockchain complexity, no consensus mechanisms, no proof-of-work

- Fast: Verification happens instantly against a database

- Auditable: The registry is maintained transparently, and anyone can query it

- Scalable: A single well-maintained database can handle billions of entries

- Browser-compatible: Extensions and search engines can integrate easily

Challenges:

- Monopoly risk: Someone has to run the registry, and they gain enormous power

- Censorship: If the registry is controlled by a single entity, they could deny service to inconvenient voices

- Resilience: If the registry goes down, verification fails

- Adoption: Convincing global publishers to use a single system is still hard

But you know what? That's actually manageable. You could have multiple registries that cross-verify each other. Different regions could maintain their own. Open standards could ensure portability.

The New York Times maintains its own fingerprint registry. So does Reuters. So does AP. A small blogger uses the "open registry." When content is shared across platforms, the fingerprints are cross-verified. The system becomes resilient because no single entity controls it.

This is actually how X.509 certificates work for HTTPS. No single authority runs the whole thing. Instead, there's a network of trusted certificate authorities that cross-verify each other. It took decades to build trust in that system, but it works.

Something similar could work for content.

What Journalists and Publishers Are Doing in Response

While theorists debate fingerprinting mechanisms, real publishers are already acting.

By late 2025, major news organizations had started implementing their own verification systems:

The New York Times launched a "Verified by NYT" badge that appears in search results and social feeds. They cryptographically sign their articles, making it verifiable that specific content actually appeared on their site at a specific time. It's not foolproof, but it's a strong signal.

The Guardian went further, embedding machine-readable metadata in their articles that includes author information, publication date, and revision history. They made this data public and machine-readable, so anyone could verify the chain of custody.

Medium implemented a contributor verification system where writers tie their accounts to identity verification. A badge appears next to their name, and readers can see the history of articles they've published.

Substack made author verification central to their model from the start. You know who wrote what. The identity is verified. The publication history is transparent.

Smaller publications don't have the resources to implement custom systems, but they're adopting third-party tools like Caveat (which creates cryptographic proofs of article authenticity) and Underline Security (which helps verify content hasn't been modified).

The pattern is clear: when the system breaks, publishers stop relying on the system. They build their own verification mechanisms and cultivate direct relationships with readers who trust them.

This is actually healthy. It means verification isn't centralized but distributed. The Times has its own trust. The Guardian has its own trust. Substack writers have their own trust.

But it also means that readers need to verify multiple systems, which is less convenient than a universal standard.

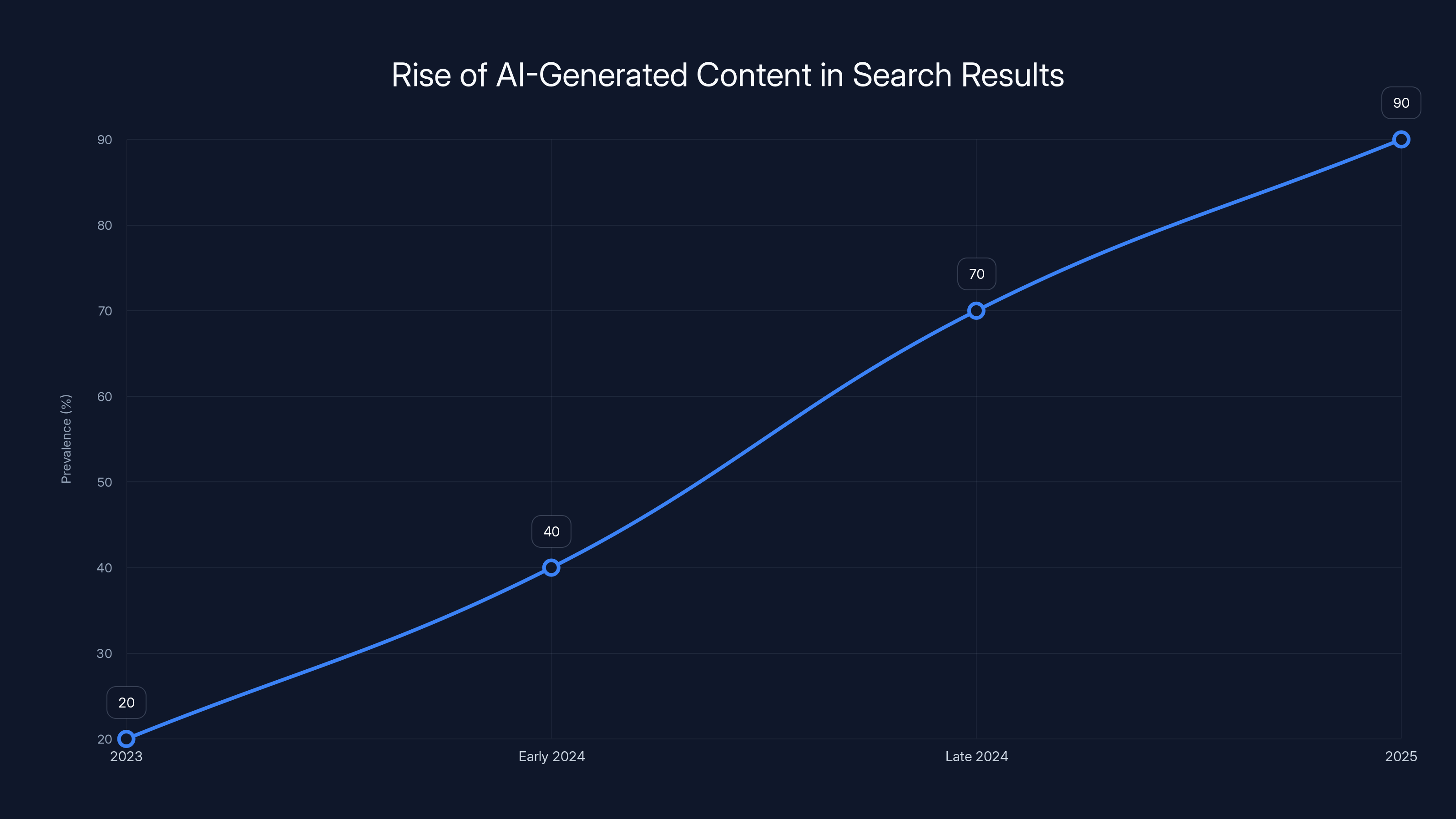

Estimated data shows a sharp increase in AI-generated content dominating search results by 2025, highlighting a shift towards quantity over quality.

The Role of Search Engines in 2026

Search engines could be the key to mainstream fingerprinting adoption.

Imagine Google saying: "We're going to prioritize fingerprinted, verified content in our search results. If your article is cryptographically signed and your identity is verified, it gets a ranking boost."

Suddenly, every publisher would implement fingerprinting overnight. The incentive would be massive. Not because fingerprinting is technically superior, but because Google said it matters for rankings.

Google actually has the leverage to make this work. They control the dominant discovery mechanism on the internet. If they decide that only fingerprinted content appears in top results, the internet adapts.

But here's the catch: Google itself would need to verify that they're implementing it correctly. If they're just moving the trust problem from "is this content good?" to "did Google verify it correctly?", you haven't actually solved anything.

This is where regulatory frameworks enter the picture.

By late 2025, the EU was developing Digital Services Act requirements for content authentication. The idea: platforms and search engines would need to implement some form of content verification to receive certain benefits (like liability protection). The standard itself wasn't mandated, but the infrastructure had to exist.

America moved slower, as usual. But there was momentum toward the idea that search engines and social platforms should have some responsibility for content authenticity.

The cynical take: none of this actually requires fingerprinting specifically. Google could just implement AI detection and show labels for likely-generated content. That would reduce slop without needing cryptographic signatures.

The realistic take: combination approach. Fingerprinting for verified human content. Detection and labeling for AI content. Removal for spam. The tools are different, but they're all deployed together.

By 2026, expect to see:

- Search results showing "Verified Human Content" badges from fingerprinted sources

- "Contains AI-Generated Elements" labels on mixed-content articles

- Removal or significant de-ranking of pure-spam content

- A bifurcation: high-trust verified content and lower-trust unverified content

It won't be perfect, but it'll be better than the 2025 disaster.

The Dilemma: Creator Surveillance vs. Content Trust

Here's the uncomfortable part of fingerprinting that nobody wants to discuss: it requires tracking.

For fingerprinting to work, you need to know who the author is. Not pseudonymously. Actually know. Your name, your credentials, possibly your identity document.

On one hand, this makes trust possible. You can verify that a journalist actually wrote that article. You can trace the chain of custody.

On the other hand, this is an unprecedented tool for surveillance and control.

A government could require fingerprinting, then use it to track who created politically inconvenient content. Imagine China implementing fingerprinting, then prosecuting anyone who published content the government disapproved of—they'd have a timestamped, verified record of exactly who did it.

Even in democracies, this is worrying. A corporation could see exactly who created leaked internal documents. A whistleblower's identity would be verifiable and permanent.

The fingerprinting advocates argue that pseudonymity is still possible. You could create an identity ("Journalist XYZ") that's verified as consistent but not tied to your real name. You could build reputation under a pseudonym, and readers would trust that pseudonym's fingerprint.

But maintaining pseudonymity in a system that requires identity verification is genuinely difficult. One slip, one data breach, one government request, and your pseudonym is exposed.

So there's a real tension: fingerprinting could save the internet's information ecosystem, but it could also create the most powerful surveillance and control mechanism ever built.

The responsible implementation would:

- Allow true pseudonymity with reputation-building

- Require strong data protection and encryption

- Limit access to fingerprint registries

- Prevent governments from using the system for surveillance

- Build in regular audits and transparency reports

But those are all "would," not "would definitely." The technology itself is neutral. The implementation determines whether it's a tool for trust or a tool for control.

This is why 2026 might be the year of implementation, but the real battle is over governance.

What Happens to AI-Generated Content?

Fingerprinting solves the authenticity problem for human-created content. But it doesn't actually address AI-generated content.

Here's an interesting possibility: what if AI-generated content also got fingerprinted?

Imagine a system where:

- Human-created content gets a "human author" fingerprint

- AI-generated content (with human approval) gets an "AI-assisted" fingerprint

- AI-generated content (without human review) gets an "AI-generated" fingerprint

- Spam content gets no fingerprint and gets de-ranked

Now users can see immediately which content was written by humans and which was generated by AI. They can make informed choices about what to read.

Curiously, this might actually help some AI-generated content. There are legitimate uses for AI generation. Summarizing long documents. Creating boilerplate content. Drafting initial versions that humans edit. If you clearly label this as "AI-assisted," users aren't deceived.

But "spam-optimized AI slop created solely for SEO" would have no label, no verification, no fingerprint. It would just fail to appear in search results.

The question is whether AI companies would implement this honestly. If Anthropic creates a system to label Claude-generated content, would they actually label all of it? Or would they help users generate content that evades detection?

You know the answer: both. Some people would use the honest labeling. Others would look for the tools that bypass detection.

But the floor would rise. You couldn't create massive AI-spam farms with impunity. The good-faith actors would be rewarded with visibility. The bad-faith actors would be fighting for scraps.

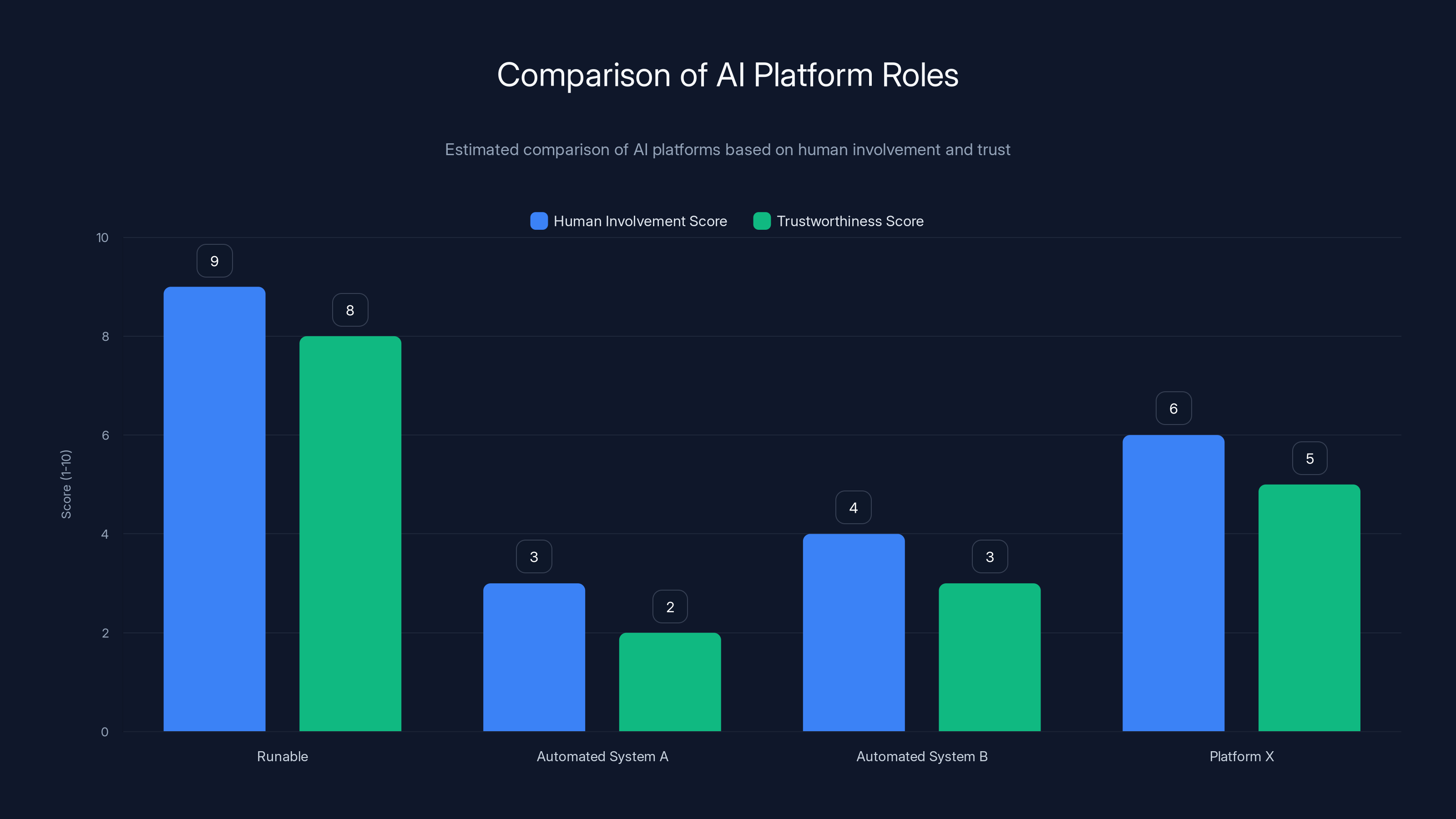

Platforms like Runable score higher in human involvement and trustworthiness compared to fully automated systems. Estimated data.

The Role of AI Platforms Like Runable in This New World

Platforms designed to assist human creators—like Runable, which helps teams generate presentations, documents, reports, images, and videos—actually benefit from fingerprinting.

Here's why: when you use Runable to create a presentation or document, the human authorship is clear. You're using AI as a tool, not as a content factory. The final deliverable is something you reviewed, edited, and approved. That's fundamentally different from automated content generation.

In a fingerprinted internet, AI-assisted platforms would get labeled as such. Users would see: "Created with AI assistance by Sarah Chen." This is actually trustworthy. Sarah's reputation is on the line. She reviewed it. She's accountable for what's in it.

Compare this to: "Generated by automated system, timestamp 2025-11-14, no human review." That gets de-ranked immediately.

So platforms like Runable (starting at just $9/month) that emphasize the human-in-the-loop would thrive. Automated spam generation systems would become economically unviable.

This is actually great for the ecosystem. AI tools aren't going away. But they're getting repositioned from "content factories" to "productivity enhancers." That's a healthier future.

The Standards Wars Ahead

2026 is probably going to see the emergence of competing fingerprinting standards, and that's both good and bad.

Good: competition drives innovation. Different approaches will be tested. The best solutions will emerge.

Bad: fragmentation makes adoption harder. If Microsoft pushes one standard and Google pushes another, publishers have to support both. Users have multiple verification systems to trust.

The likely scenario: W3C (the standards body for the web) gets involved. They convene stakeholders: publishers, platforms, journalists, technologists. They design an open standard for content authentication. Implementations vary, but the underlying protocol is universal.

This happened with HTML, CSS, and HTTP. It took years, but the open standards won out over proprietary alternatives.

But it could also go another way: a company (probably Google or Microsoft) pushes a fingerprinting system so hard and makes it so useful that everyone adopts it de facto. It becomes a standard not through consensus but through market dominance.

Either way, expect to see:

- W3C Content Authentication Task Force forming and publishing drafts

- Browser implementation of fingerprint verification (Chrome leads, others follow)

- Publisher consortiums creating shared fingerprint registries

- Third-party verification services offering authentication-as-a-service

- Regulatory momentum pushing standardization

By 2027, fingerprinting will either be standard practice or proven not viable. There's no middle ground where it slowly gains adoption. The problem is too urgent, and the incentives are too strong.

What This Means for Readers

If fingerprinting becomes standard, the internet changes for ordinary people.

Searching for information becomes more reliable. You see badges next to results: "Verified Human Content," "AI-Assisted Content," "Unverified Content." You can filter your search results by which sources you trust.

Reading articles becomes more transparent. You know who wrote it, when it was published, whether it's been modified, and what updates have been made since publication.

Sharing content becomes more accountable. If you share an article and it later proves to be false, that gets recorded. Your reputation for sharing trustworthy content matters.

But there are downsides:

- Pseudonymous creators lose some protection

- Whistleblowers become more vulnerable

- Authentication systems could be weaponized

- Niche content by anonymous experts becomes harder

- The internet becomes slightly less free and more traceable

It's a tradeoff. More trust, less freedom. More verification, more surveillance. Better information, less anonymity.

Worthy tradeoff? Probably. But it's a tradeoff nonetheless.

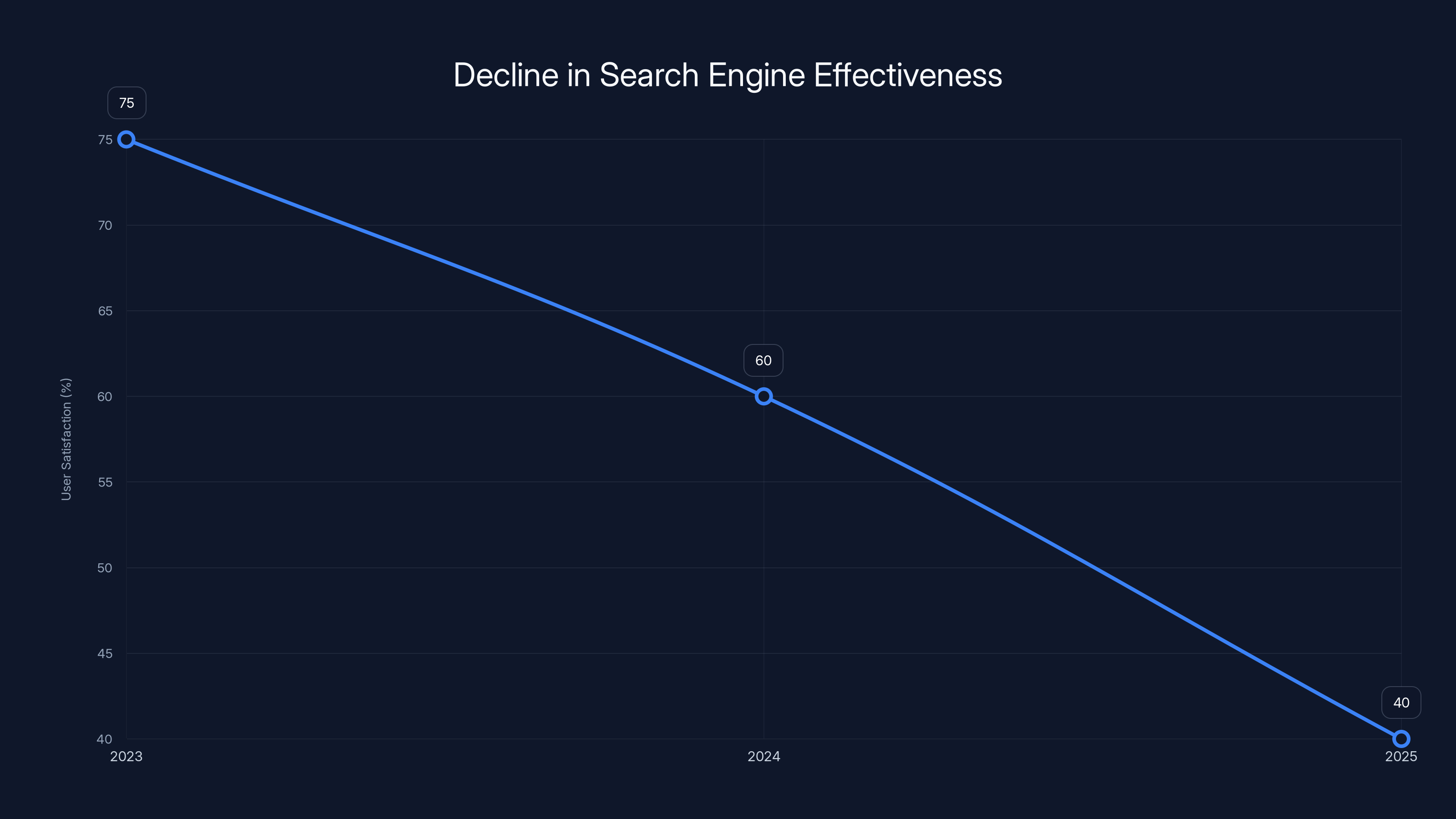

Estimated data shows a decline in user satisfaction with search engines from 2023 to 2025, reflecting the rise of AI-generated content and spam. By 2025, satisfaction dropped significantly as users sought more authentic discussions on platforms like Reddit.

The Pragmatic Path Forward for 2026

Here's what will probably actually happen, not what should happen or what theorists want to happen:

Google announces fingerprint integration (early 2026). They don't require it, but they reward it in rankings. Major publishers immediately implement it.

Browser vendors add verification UI (mid-2026). Chrome, Firefox, Safari add small indicators showing fingerprint status. Users start noticing when content is verified.

Standards body publishes draft specs (mid-2026). W3C releases Version 0.5 of a content authentication standard. It's not final, but it's good enough for implementation.

Third-party services explode (late 2026). Startups build tools to help publishers implement fingerprinting, verify content, and manage authentication. The space gets crowded with options.

Content farms respond (ongoing). The ones that can afford it implement fake fingerprints or find loopholes. Most just pivot to different monetization models.

Trust slowly returns (2027 onwards). Search results gradually improve as verified content gets prioritized and slop gets buried.

It's not a revolution. It's a messy, iterative, imperfect process. But it moves the needle.

The Role of Media Literacy in a Fingerprinted Internet

Here's something crucial that often gets overlooked: fingerprinting doesn't actually solve media literacy problems.

Just because content is verified human-created doesn't mean it's true.

A journalist could write a technically truthful article that's misleading. A researcher could have a biased methodology. A blogger could be completely sincere and completely wrong. The fingerprint just proves the author is who they claim to be; it doesn't prove the content is accurate.

So fingerprinting needs to be paired with—not replaced by—actual critical thinking. Readers still need to:

- Evaluate sources and expertise

- Check citations and methodology

- Recognize bias and funding sources

- Compare multiple perspectives

- Distinguish correlation from causation

- Question extraordinary claims

Fingerprinting is a filter, not a fact-check. It reduces the noise level so that real media literacy can work. But it doesn't eliminate the need to think critically.

In fact, fingerprinting might enable worse media literacy if people assume "verified = true." That would be dangerous.

The responsible narrative is: "Fingerprinting helps you know who wrote something and when. It reduces deliberate deception. But it doesn't eliminate the need to think critically about what you read."

Simple but important nuance.

Predictions for 2026 and Beyond

If I'm right about the trajectory, here's what to expect:

Q1 2026: Google announces fingerprinting support in search results. Major publishers begin implementation.

Q2 2026: Microsoft and Open AI launch competing fingerprinting initiative. Standards battle begins in earnest.

Q3 2026: W3C publishes Version 1.0 draft of content authentication standard. Significant differences from both Google and Microsoft approaches.

Q4 2026: All major browsers support some form of fingerprint verification UI. Readers start seeing badges on search results and articles.

2027: Fingerprinting becomes standard practice for professional publishers. Unverified content gets significantly de-ranked in search.

2028: Content farms have either adapted (by being honest about AI assistance) or shut down. Search results are measurably more helpful.

2029: Fingerprinting becomes expected. The internet of unverified anonymous content becomes a historical curiosity.

But here's my honest prediction: something will go wrong. A major breach. A government using the system for censorship. An exploit that breaks the fingerprinting mechanism. By 2028, there will be a crisis that makes people question whether fingerprinting was the right answer.

Then we'll iterate and improve.

Because that's how the internet works. We break things. We fix them. We break them differently. We fix those breaks. The system slowly improves through failure and adaptation.

FAQ

What is AI slop and why did it become such a problem in 2025?

AI slop refers to low-quality, AI-generated content created primarily for SEO and monetization purposes rather than providing genuine value to readers. It became such a dominant problem in 2025 because the economics aligned perfectly: generating content through AI costs near-zero while the potential revenue from advertising and affiliate links remains significant. By mid-2025, between 50-70% of new content indexed by search engines contained some degree of AI generation, with many articles being entirely synthetic and indistinguishable from human-written content to both algorithms and casual readers.

How does content fingerprinting work to verify authentic content?

Content fingerprinting uses cryptographic algorithms to create a unique, mathematically verifiable signature for a specific piece of content at a specific time. When an article is published, the system captures the exact content, authorship information, and publication timestamp, then generates a cryptographic hash that serves as a fingerprint. This fingerprint gets recorded in an immutable registry. When someone encounters the content, they can verify whether the fingerprint matches what was originally published, confirming that the content hasn't been modified and was actually created by the claimed author at the claimed time.

What are the main technical challenges preventing fingerprinting from becoming mainstream?

The adoption problem is significant: getting widespread consensus across publishers, platforms, search engines, and browsers is extraordinarily difficult. There's also the centralization dilemma of deciding who maintains the fingerprint registry without creating a single point of failure or censorship. Retroactively fingerprinting the billions of articles already on the internet is impossible. Additionally, false positives occur when legitimate republication or extensive quotation is flagged as tampering. Finally, fingerprinting doesn't actually solve the deeper problem that a human using AI to generate content would still show as human-created.

Will blockchain solutions work for content fingerprinting?

Blockchain offers theoretical advantages for decentralization and immutability but faces practical drawbacks for content authentication at internet scale. It would require enormous computational resources and electricity, creates scalability challenges for millions of daily publications, and presents poor user experience when systems fail. While blockchain could work for specific use cases like news organization consortiums or academic paper verification, a simpler trusted-authority database model—similar to how HTTPS certificate authorities function—is likely more pragmatic for internet-scale fingerprinting.

What's the difference between fingerprinting human-created content and detecting AI-generated content?

Fingerprinting proves authorship and timestamp without needing to determine generation method—if the cryptographic signature matches, the content is verified as human-created and unmodified. AI detection, by contrast, attempts to identify whether content was likely generated by machine learning models rather than written by humans. Fingerprinting is mathematically sound and impossible to bypass; AI detection is fundamentally a moving target that improves AI models can circumvent. A comprehensive solution would likely use both: fingerprinting for verified authentic content and AI detection with labeling for unverified content.

How will fingerprinting affect platforms like Runable that use AI to assist human creators?

Platforms designed to help humans create content while maintaining authorship accountability actually benefit from fingerprinting systems. When a user creates a presentation, document, or report with Runable's AI assistance, the human creator's responsibility and authorship is clear—the fingerprint would show "Created with AI assistance by [Author Name]," which is transparent and trustworthy. This contrasts sharply with fully automated spam generation, which would receive no fingerprint. AI-assisted platforms that emphasize human-in-the-loop workflows would thrive in a fingerprinted internet, while pure content generation systems become economically unviable.

Could fingerprinting be used as a tool for government censorship or surveillance?

Yes, this is a legitimate concern. Requiring identity verification for fingerprinting creates unprecedented surveillance potential—governments could track who created inconvenient content, and whistleblowers become more vulnerable. However, responsible implementation could mitigate this through allowing true pseudonymity with reputation-building, requiring strong data protection and encryption, limiting registry access, and implementing transparency reports. The technology itself is neutral; how it's governed determines whether it becomes a tool for trust or control. This is why the governance and regulatory framework around fingerprinting will be more important than the technical specification.

What will search results look like in 2026 if fingerprinting becomes standard?

Search results would likely show verification badges next to results from fingerprinted sources, perhaps with different visual indicators for verified human content, AI-assisted content, and unverified content. Users could filter results by verification status. Articles would display author information and modification history transparently. The overall result is greater clarity about source authenticity, though not a guarantee of accuracy. Unverified content would be de-ranked significantly, pushing AI-spam sites down while elevating traditional media, verified blogs, and authenticated sources.

How does this all relate to media literacy?

Fingerprinting is a filter for authenticity, not a fact-checker for accuracy. A verified human can write something that's completely true about who created it but false in its claims and conclusions. Fingerprinting reduces deliberate deception and helps readers identify trusted sources, but critical thinking remains essential. Readers still need to evaluate expertise, check citations, recognize bias, and question extraordinary claims. The danger is if people assume "fingerprinted = true," which would be a false equivalence and potentially enable worse media literacy than we currently have.

When will fingerprinting actually become standard practice?

Based on the current trajectory, 2026 will likely see major search engines and browsers beginning to support fingerprinting. Major publishers will implement it quickly once search engines incentivize it through ranking benefits. By 2027-2028, it will be expected standard practice for professional publishers. By 2029, unverified content will be significantly de-ranked or filtered out. However, this timeline assumes no major crises or exploits that undermine the system—and something probably will go wrong, requiring iteration and improvement.

What Comes After the Fingerprinting Implementation

Assuming fingerprinting actually takes off and becomes standard by 2027, we enter an interesting new phase: what happens when the problem of authenticity is partially solved but new problems emerge?

One issue is the verification paradox. Users would see that an article is fingerprinted and think "this is verified as real." But what they're really seeing is verification of authorship, not accuracy. A hoax written by a named author and fingerprinted is still a hoax. You've solved the deception problem but not the misinformation problem.

This actually creates a new attack vector. A bad actor could build a reputable fingerprinted account over time, establishing trust, then use that trust to publish false information. It's like how verified Twitter accounts (back when verification meant something) sometimes spread misinformation more effectively than unverified accounts.

The second phase of internet trust isn't fingerprinting. It's reputation systems. Who has been right in the past? Whose sources check out? Whose articles hold up to scrutiny over time? These are harder problems than authentication, but they're the ones that actually matter.

You can build reputation on top of fingerprinting. A journalist's fingerprinted articles accumulate history. You can see their track record. Over time, you learn whether you trust them. This is genuinely useful.

But it requires maintaining history, which is expensive. It requires attribution, which is difficult when articles are edited or updated. It requires nuance about what "being right" means in a complex world.

The internet of 2027 might have solved the "is this real?" problem. But it'll immediately face the "is this trustworthy?" problem, which is harder.

The Bottom Line: Why 2025 Was the Crisis Point

Historians will probably mark 2025 as the year the internet's information commons collapsed.

Not because AI itself was new. Not because AI-generated content was unprecedented. But because the volume, velocity, and sophistication reached a critical mass that broke existing trust mechanisms.

You could ignore one AI article. You could spot a thousand. But when 50-70% of new content is synthetic, when search algorithms can't distinguish good from bad, when the entire information ecosystem is polluted, something has to give.

Fingerprinting might be the answer. It might not be. Maybe we'll solve it through AI detection. Maybe we'll go back to trusted sources and abandon search results. Maybe we'll use a combination of techniques we haven't invented yet.

But something will change. It has to.

Because an internet where you can't trust that content was actually written by a human, where you can't verify authorship, where every search result might be spam, isn't an internet anymore. It's just noise.

The crisis of 2025 was the crisis of meaning. In 2026 and beyond, solving it becomes the central challenge.

That's why content fingerprinting, despite all its flaws and complications and potential for misuse, might actually be the least bad solution we have. Not because it's good. But because the alternative—an internet without authentication—became unlivable.

Key Takeaways

- AI slop—low-quality AI-generated content—became dominant in 2025 because the economics were irresistible: generation costs near-zero, revenue potential high, incentives misaligned with quality

- Content fingerprinting uses cryptographic signatures to prove authorship and timestamp, solving authenticity verification without requiring AI detection

- Technical challenges include adoption coordination, centralization concerns, retroactive implementation, and the reality that fingerprinting proves authorship, not accuracy

- Search engines implementing fingerprinting in 2026 would create immediate incentive for publishers to adopt verification, accelerating mainstream implementation

- Fingerprinting could enable AI-assisted platforms like Runable while disabling spam farms, creating a healthier ecosystem where human responsibility is transparent

![The AI Slop Crisis in 2025: How Content Fingerprinting Can Save Authenticity [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-ai-slop-crisis-in-2025-how-content-fingerprinting-can-sa/image-1-1767370096298.jpg)