The Wireless Capacity Crisis in Crowded Spaces [2025]

You've been there. A concert, a stadium, a conference center packed with thousands of people. You pull out your phone to snap a photo, and nothing happens. Your messages sit in the queue. Videos buffer. Calls drop mid-conversation.

It's not your phone. It's not your carrier either, exactly. It's the fundamental mismatch between how wireless networks were designed and what we're asking them to do today.

Last year's CES in Las Vegas exposed this problem in stunning relief. The convention center had cellular coverage. The hotels nearby had cellular coverage. The Strip had cellular coverage. Yet attendees faced $80-a-day Wi-Fi charges or cellular speeds so slow that checking email felt like waiting for a download from 2008. Here's the thing: this isn't a new problem. It's a problem that's been getting worse, and nobody in the industry wants to talk about it publicly.

Why? Because solving it requires rethinking how we've built wireless infrastructure for the past two decades.

TL; DR

- Cellular networks fail in crowded environments because they're designed for steady, distributed usage, not intense bursts of simultaneous demand from thousands of devices

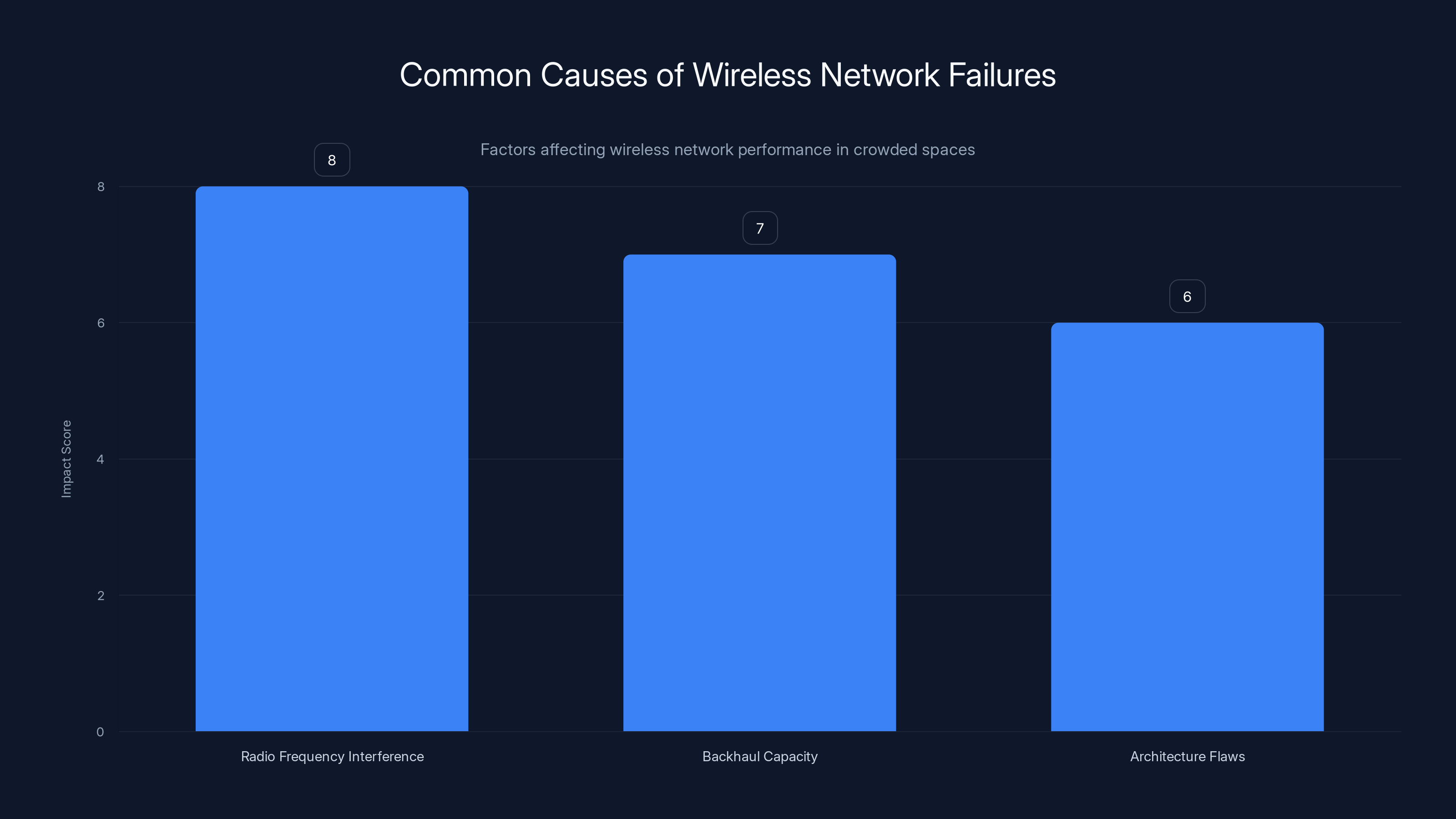

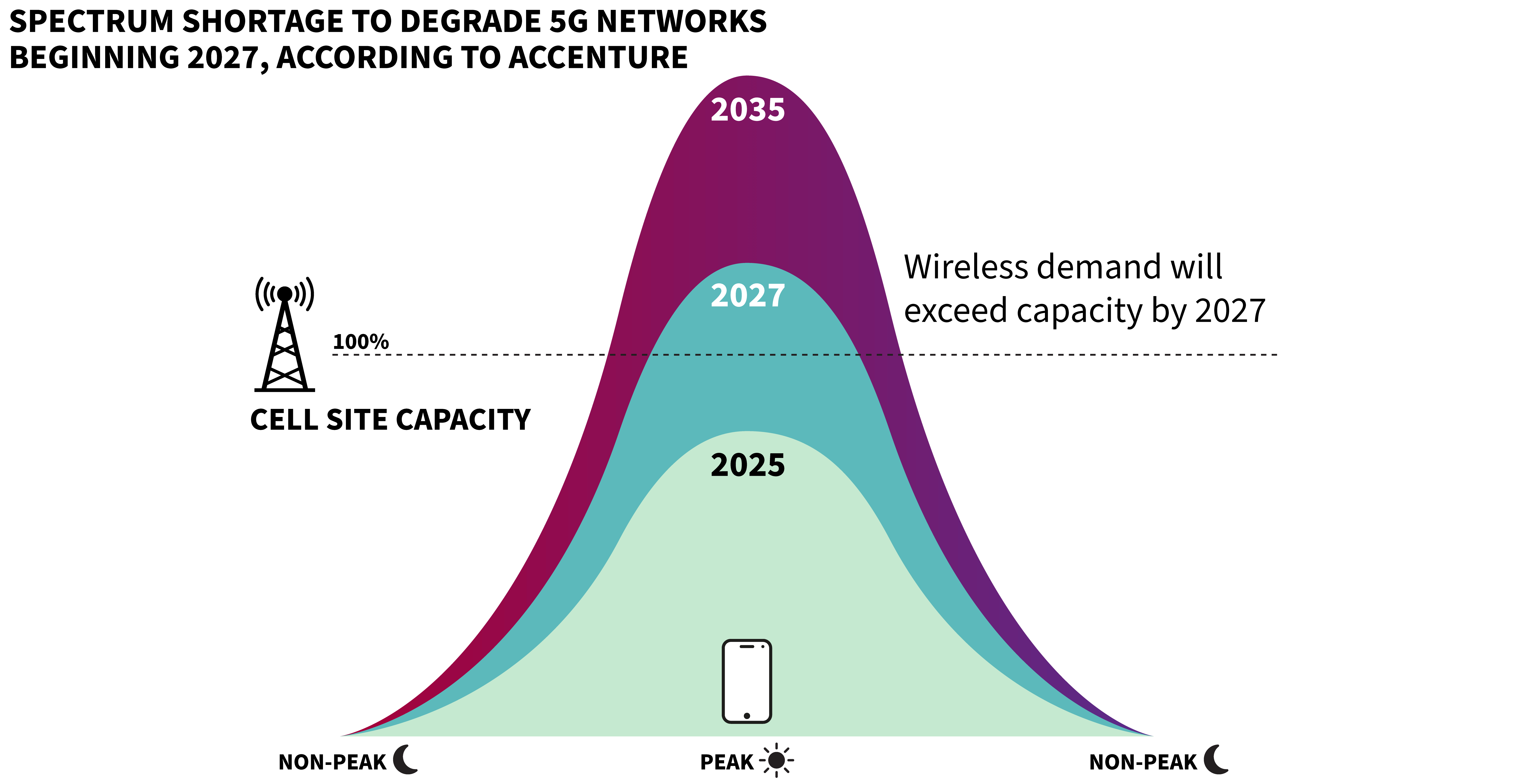

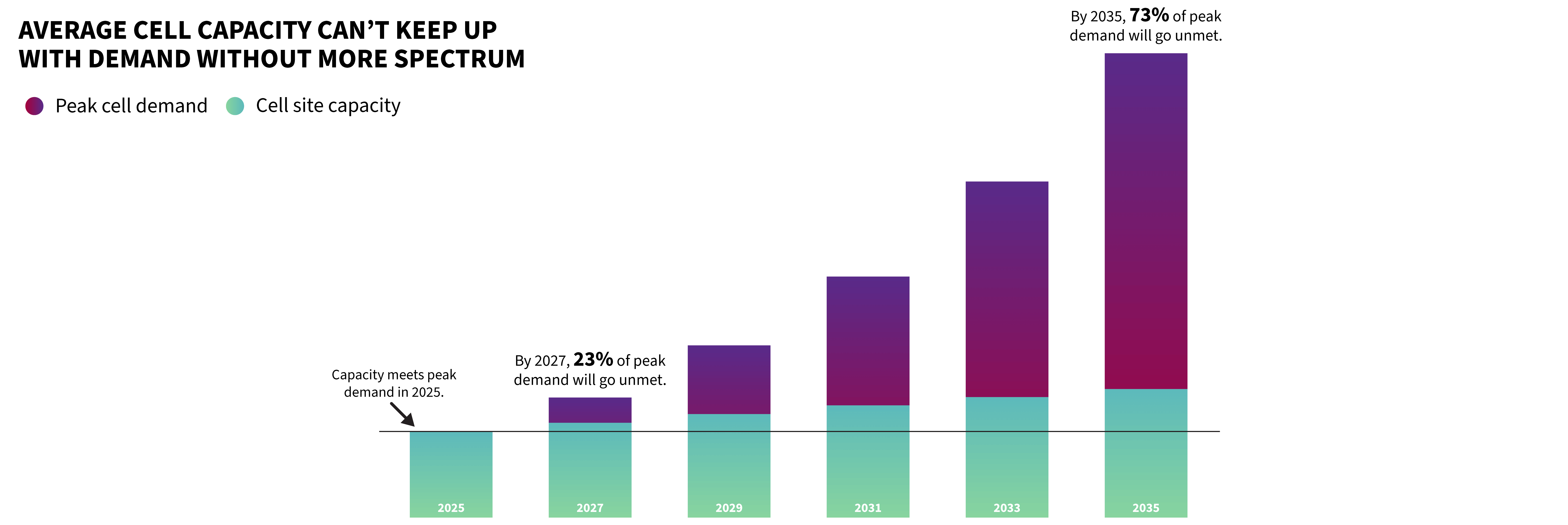

- Radio frequency interference is the physics-based bottleneck, not spectrum shortage—adding more radios actually makes congestion worse by increasing the noise floor

- Backhaul and access are competing for the same limited spectrum, creating a fundamental architectural flaw that traditional capacity additions can't fix

- Optical wireless links separate high-capacity backhaul from user access, eliminating interference and creating predictable, scalable connectivity

- Real-world solutions require precision engineering, not just more towers—separating backhaul from access, using directional beams instead of broadcast signals, and designing networks around physics instead of ignoring it

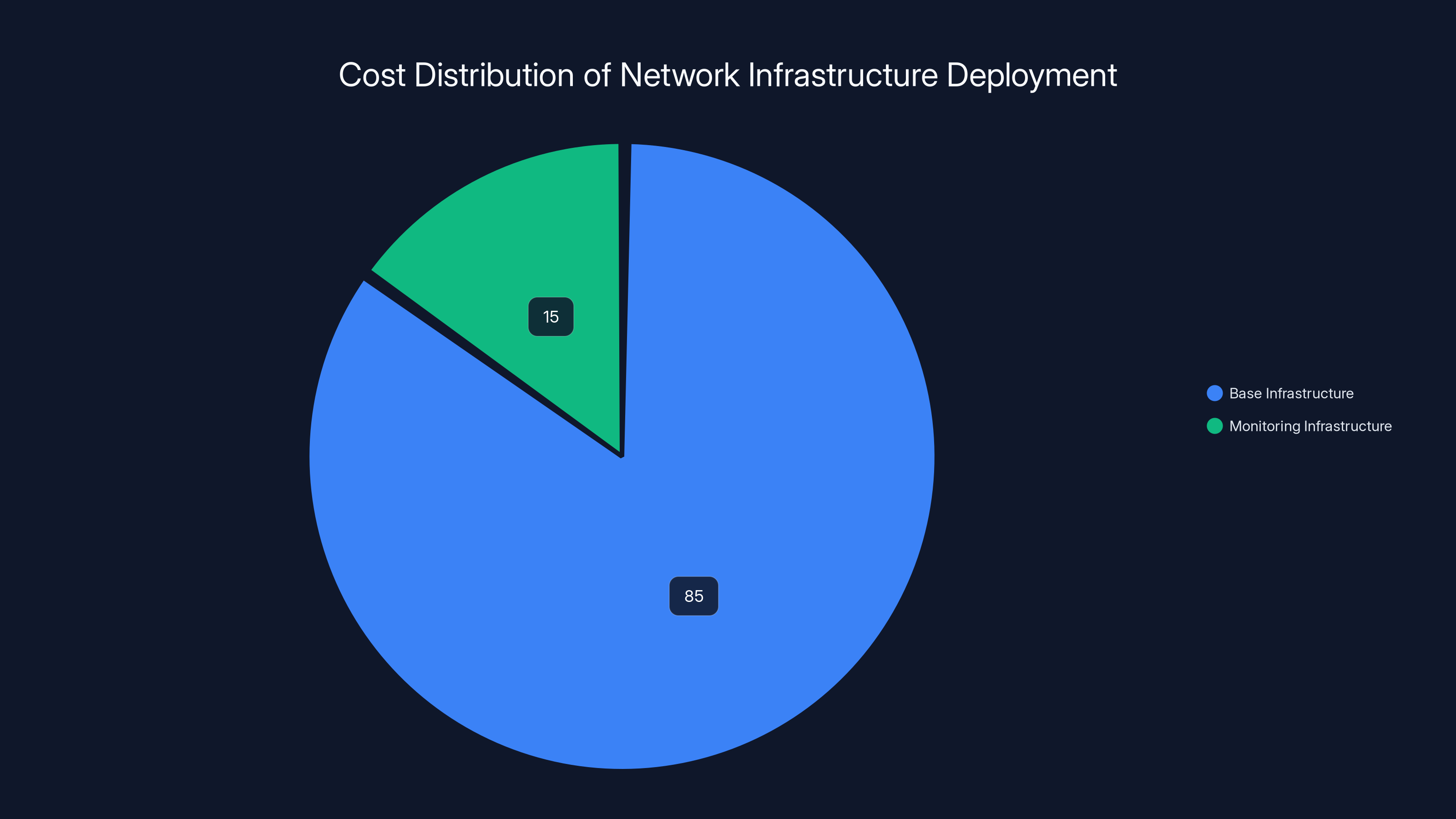

Radio frequency interference is the most significant factor causing wireless network failures in crowded spaces, followed by backhaul capacity and architecture flaws. Estimated data based on typical network challenges.

The Problem Nobody Wants to Admit

When thousands of people gather in one place, something remarkable happens. They all pull out their phones at exactly the same moment. A concert starts, and everyone films. A keynote ends, and everyone uploads. A moment worth sharing arrives, and millions of devices compete for the same spectrum simultaneously.

The network wasn't built for this. It wasn't built for you.

Cellular networks have a hidden assumption baked into their design: usage is distributed across geography. A city has millions of people spread across hundreds of square miles. Each person uses a bit of bandwidth at random times. The network can handle that. But pack fifty thousand people into one convention center? That assumption explodes.

Every attendee at CES arrives with multiple connected devices. A smartphone. A tablet. A smartwatch. A laptop. Some bring AR glasses or connected cameras. Each device is constantly running background syncing, location services, and cloud applications. When demand spikes, these thousands of devices don't wait politely for their turn. They all transmit simultaneously, all competing for attention.

Most wireless connectivity today relies on shared radiofrequency spectrum. Think of it like a highway. When traffic is light, you can cruise. When everyone tries to use the highway at once, you get gridlock. But spectrum congestion is worse than highway congestion. On a highway, cars can at least see each other and coordinate. Radio signals? They just collide, overlap, and interfere.

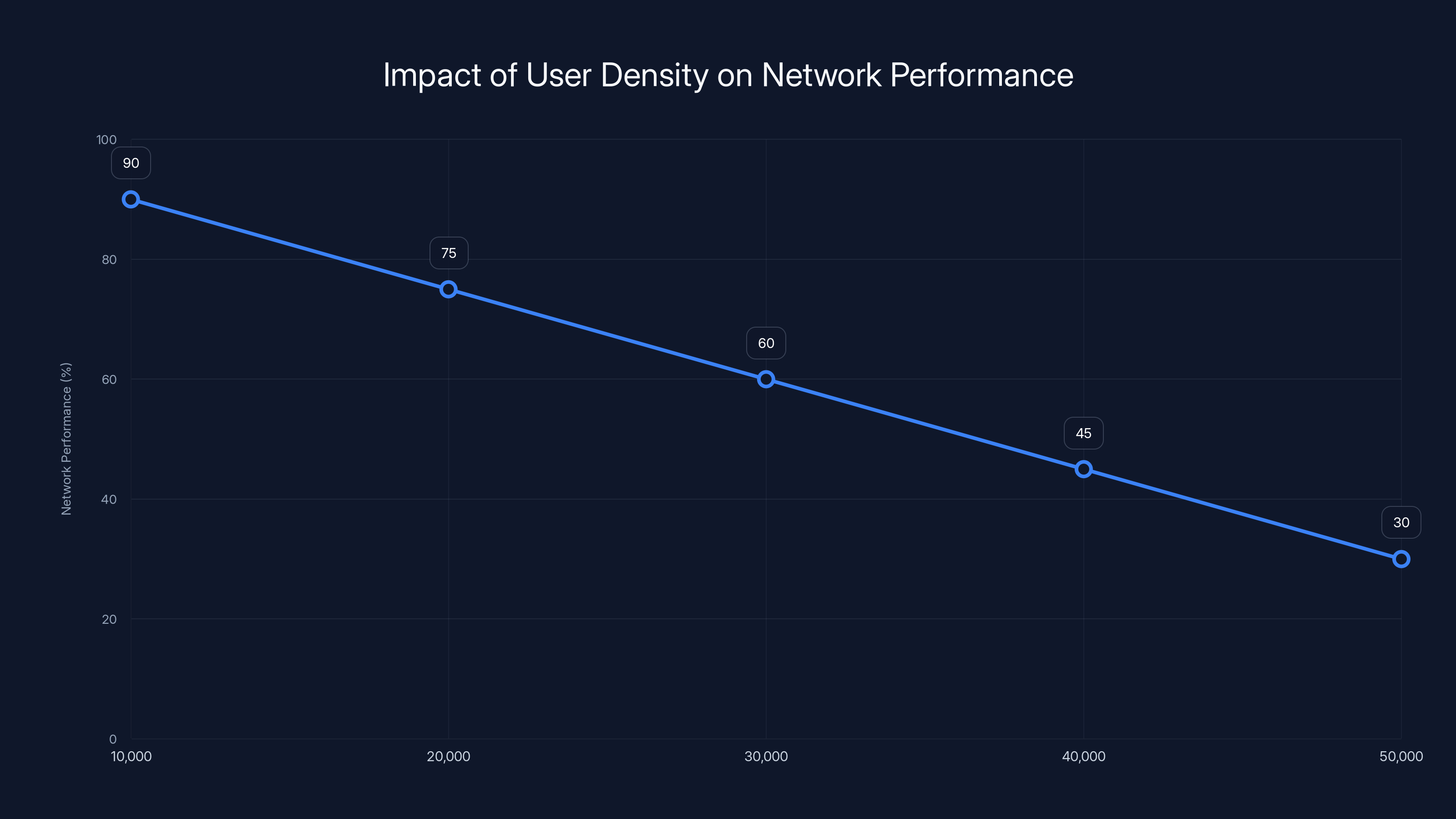

When bandwidth gets saturated and congestion sets in, network performance deteriorates for everyone. And here's the cruel part: as more users join the network, each person gets a smaller slice of available capacity. The experience gets worse the more people want to use it.

Old thinking would suggest adding more radios, more channels, more infrastructure. But that solution doesn't work. More radios mean more devices transmitting simultaneously, which increases interference and makes the noise floor higher for everyone else. You're not solving congestion. You're making it worse by adding more noise to an already-noisy environment.

The network isn't failing because it's broken. It's failing because it's being asked to do something it was never architected to handle.

Understanding Radio Frequency Interference

To understand why networks fail in crowded spaces, you need to understand interference. This is where the real story gets interesting.

Radio frequency spectrum is inherently shared. Think of it like a concert hall where thousands of people are all trying to talk at once. Your ears pick up sound waves from everyone. You can't understand what one person is saying because you're hearing every voice simultaneously. The louder everyone talks, the harder it is to pick out individual conversations.

Radio signals work the same way. In a dense environment, thousands of devices and access points are transmitting and receiving at the same time, all within a relatively small physical space. Signals collide. Signals overlap. Signals compete. Every additional transmission increases the noise floor for everyone else on the network.

Here's where most people get confused: the problem isn't that we don't have enough spectrum. The problem is that interference limits how efficiently we can use the spectrum we have. If you have interference bottlenecking your network, adding more spectrum doesn't help. It's like adding another lane to a freeway when the real problem is that you're sharing the lanes in a way that creates accidents.

The natural industry response has been to add more radios, more channels, and more complexity. Squeeze more access points into the same space. Use more advanced signal processing. Deploy fifth-generation networking with fancier modulation schemes. But capacity doesn't scale linearly when interference is the dominant bottleneck.

Let's think about this mathematically. If you have interference-limited capacity, adding a second radio source doesn't double your capacity. It might increase capacity by 20-30%, but you've also doubled the interference. The equation doesn't work.

What's needed is a different approach entirely. Instead of trying to squeeze more devices into the same shared spectrum, you need to separate the high-capacity backbone traffic from the user access traffic.

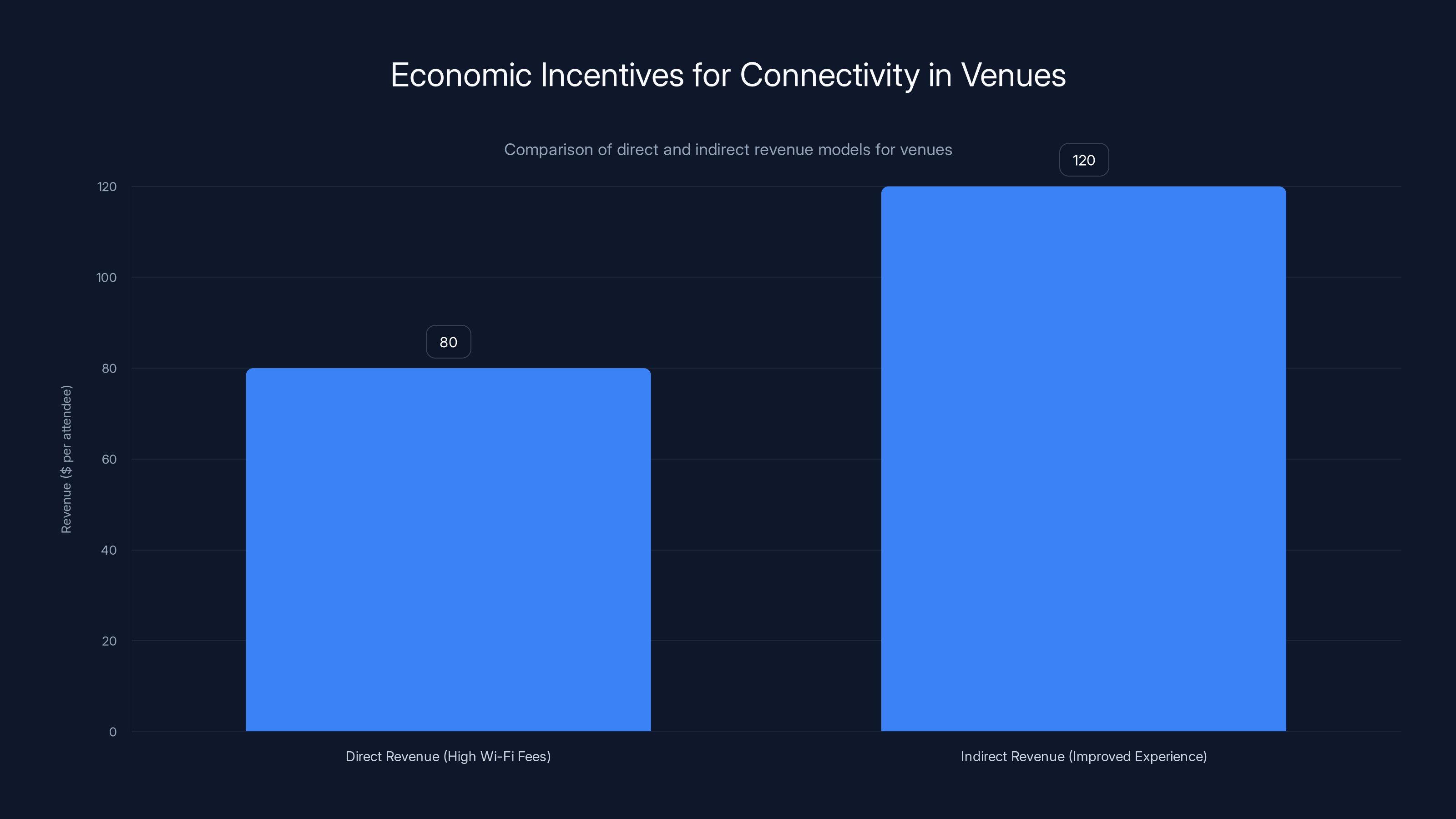

Venues can earn more through indirect revenue by improving connectivity, leading to increased spending and attendance. Estimated data based on typical venue pricing and spending patterns.

The Architecture Problem: Backhaul vs. Access

Wireless networks have two jobs that are currently fighting each other.

The first job is getting data into and out of a dense area at high capacity. This is called backhaul. Imagine the convention center needs to handle thousands of people streaming video, uploading photos, and running real-time applications. All that data has to come from somewhere. It needs to flow into the convention center through infrastructure that can handle massive throughput.

The second job is distributing that data to individual users at the local level. This is called access. Users inside the convention center need to be able to pick up a Wi-Fi signal or connect to cellular and send their data out.

Traditionally, both of these jobs happen over the same spectrum. The same radio frequencies carry both the backbone traffic and the user access traffic. When demand spikes, both are competing for the same limited resource. Backhaul is trying to push massive amounts of data in, while thousands of access points are trying to manage millions of user connections. They're stepping on each other.

Precision network design separates these functions. High-capacity backhaul should not compete with access traffic over the same limited spectrum. Instead, you need dedicated links that move massive amounts of data into dense environments through connections that are predictable, isolated, and designed specifically for throughput. These dedicated links feed a greater number of smaller, shorter-range access points that serve users locally.

When you separate backhaul from access, something remarkable happens. The limited radio resources get used where they're most effective. You're not stretching them thin across the entire area trying to do two jobs at once. Instead, you have enough local capacity for user access because the heavy lifting of data transport is happening on separate infrastructure.

This is why precision design matters more than just adding capacity. It's about architecture.

Cellular Networks Versus Event Infrastructure

Cellular networks are designed for one specific use case: steady, distributed demand across a geographic area. They assume that people are spread out. Usage happens randomly throughout the day. A cell tower serves thousands of people, but each person uses only a small fraction of available capacity at any given moment.

This design assumption breaks down completely at events. Suddenly, thousands of people are in one location. Everyone tries to use the network at the same time. Peak demand shifts from "spread across the entire day" to "concentrated in a few intense moments."

A typical cell tower in a city might handle peak demand of several hundred simultaneous users. At CES, you had fifty thousand people in convention halls, all with devices, all trying to connect simultaneously. This isn't "more of the same demand." It's a fundamentally different traffic pattern.

Some events have tried to solve this by bringing in temporary cellular equipment. Mobile cellular towers, extra radios, additional carrier access. It helps, but only slightly. You might increase capacity from "terrible" to "barely acceptable." Why? Because you're still working within the same interference-limited paradigm. Adding more radios adds more interference, which limits how much you can actually improve.

Wi-Fi has the same problem. A conference room Wi-Fi network might handle thirty people. A conference center Wi-Fi network tries to handle thousands. The technology is the same, but the demand is completely different. Each Wi-Fi access point has limited capacity. Add more access points and you get better coverage, but more interference and channel contention. The experience might actually get worse.

That's why venues charge $80 per day for Wi-Fi. They're not being greedy. They're using pricing to ration the scarce resource. It's an economic way to manage a technical problem. But it's still a solution that accepts the problem as inevitable.

The Latency Problem That Nobody Talks About

When we talk about network congestion, we usually focus on bandwidth: how much data can you move per second? But there's another problem that matters more at crowded events, and almost nobody talks about it.

Latency. Response time. The delay between when you press send and when the other person receives your message.

When a network is congested, latency gets worse before bandwidth does. Your message might take two hundred milliseconds to be processed instead of fifty. A voice call develops noticeable lag. A game becomes unplayable. Video conferencing turns into a slideshow.

Here's why: congestion doesn't just slow down your data. It also means your device has to wait longer in a queue before it gets access to transmit. Imagine you're trying to use a Wi-Fi network with five hundred people connected. Your device wants to send a packet. But there are five hundred other devices also waiting to send packets. By the time it's your turn, fifty milliseconds have already passed.

Add that latency across multiple hops in a network—your device to the access point, the access point to the backhaul, the backhaul through the internet—and you're looking at latencies of one to five seconds. That's unusable for real-time applications.

Most cellular networks aim for latencies under fifty milliseconds. Modern 5G networks promise under ten milliseconds. But in a congested environment at an event, you might see latencies of five hundred milliseconds to two seconds. That's enough to make any real-time application fail.

Why does this matter? Because the future of wireless networks isn't just about moving data. It's about real-time, low-latency applications. Autonomous vehicles need to make decisions in milliseconds. Augmented reality needs responsive display updates. Industrial equipment needs precise timing. Telemedicine needs real-time video and audio without lag.

If a network can't handle latency requirements in a crowded environment, it can't support these future applications. That's a bigger problem than just slow internet.

As the number of users increases, network performance significantly drops due to congestion. Estimated data based on typical scenarios.

Why "Adding More Radios" Makes Things Worse

This is the counterintuitive part that trips up most people trying to solve connectivity problems.

If you have a network that's congested because you don't have enough capacity, the obvious solution is to add more radios. More access points. More transmission equipment. More hardware to handle the load.

But in an interference-limited environment, this doesn't work. In fact, it often makes things worse.

Here's the mechanism: every radio transmitter adds noise to the spectrum. When you add a new radio, you increase the noise floor for every other device on the network. That means those devices need more signal strength to be heard above the noise. That requires more transmit power. That creates more interference for other devices.

You're in an arms race. Each new radio tries to overcome the noise from previous radios by transmitting louder. But louder transmission increases the noise floor for everyone else, forcing them to transmit louder. The cycle continues until you reach some equilibrium, but that equilibrium is worse than where you started.

This is particularly true for Wi-Fi networks. Add a tenth Wi-Fi access point to a small convention room and you might see performance improve. Add the twentieth access point to the same room and you'll likely see performance degrade. At some point, you've added so much interference that the network becomes slower, not faster.

Cellular networks have better interference management tools—frequency coordination, power control, interference cancellation. But they hit the same wall eventually. Add enough radios and the interference starts dominating your performance.

This is why precision matters. Instead of adding more radios to fight interference, you design the network to avoid the interference problem in the first place. Separate the traffic that doesn't need to share spectrum. Use directional beams instead of broadcast signals. Route high-capacity traffic onto separate infrastructure.

It's the difference between trying to fit more conversations into a crowded room by everyone talking louder, versus separating conversations into different rooms. The second approach scales infinitely. The first approach reaches a hard limit.

The Optical Wireless Revolution

What if you could move high-capacity traffic onto infrastructure that doesn't use radio spectrum at all?

This is where optical wireless communication enters the picture. Instead of using radio frequencies to transmit data, optical systems use focused beams of light. The light travels through air between two points, carrying massive amounts of data without competing with radio-based traffic.

Optical wireless isn't new technology. But deploying it in practical ways at scale is relatively recent. And the implications for dense network coverage are profound.

Here's how it works: instead of broadcasting energy across a wide area of shared spectrum, optical systems use tightly focused beams of light to move data directly between two points. An optical transmitter and receiver form a point-to-point link. That link carries as much data as you want—potentially hundreds of gigabits per second—without contributing to radio frequency congestion.

Because these links are narrow and precise, they don't interfere with surrounding wireless traffic. You can point an optical transmitter at a receiver location and deliver massive throughput. Point another transmitter at a different receiver location and deliver more throughput. The two links don't interfere with each other.

In a crowded venue, you can use optical links as the backhaul. Bring data into the convention center using optical beams instead of radio. That data feeds into local Wi-Fi access points or small cell radios that serve users at short range. The local access points have plenty of capacity because all the heavy-lifting data transport is happening on optical infrastructure that doesn't share spectrum.

This separation is transformative. Suddenly, the radio resources available for user access are actually available for user access. They're not being consumed by backhaul traffic.

Optical wireless does have limitations. Line of sight matters. Weather can interfere. You need clear paths between transmitter and receiver. But in an indoor convention center or stadium, you usually have plenty of opportunities for clear optical paths. And the alternative—radio-spectrum-based congestion—is worse.

Free Space Optics: The Infrastructure of Tomorrow

Free space optics is the broader category of technology that transmits data through air using light. It includes visible light communication, infrared communication, and laser-based systems. Each has different properties and applications.

In dense venues, infrared optical wireless is particularly useful. Infrared is invisible to human eyes but carriers can see through it and receive data at high speeds. An infrared transmitter pointed from a convention center roof to a mobile backhaul point can deliver several terabits of data per second. That's thousands of times more capacity than a radio link carrying similar data.

The beauty is that infrared links don't share spectrum with radio systems. A radio network can be operating at full congestion while an optical link silently delivers massive throughput in the same physical space. The two technologies complement each other perfectly.

Building this infrastructure requires precision. You need to know exactly where your transmitter is pointing. You need to account for alignment. You need to handle the occasional obstruction. But modern systems handle these challenges routinely.

Some venues are already experimenting with this. The Sphere entertainment venue in Las Vegas uses advanced connectivity infrastructure. Major stadiums are deploying hybrid networks that combine radio and optical. The technology works. The question is whether the industry will standardize and scale it.

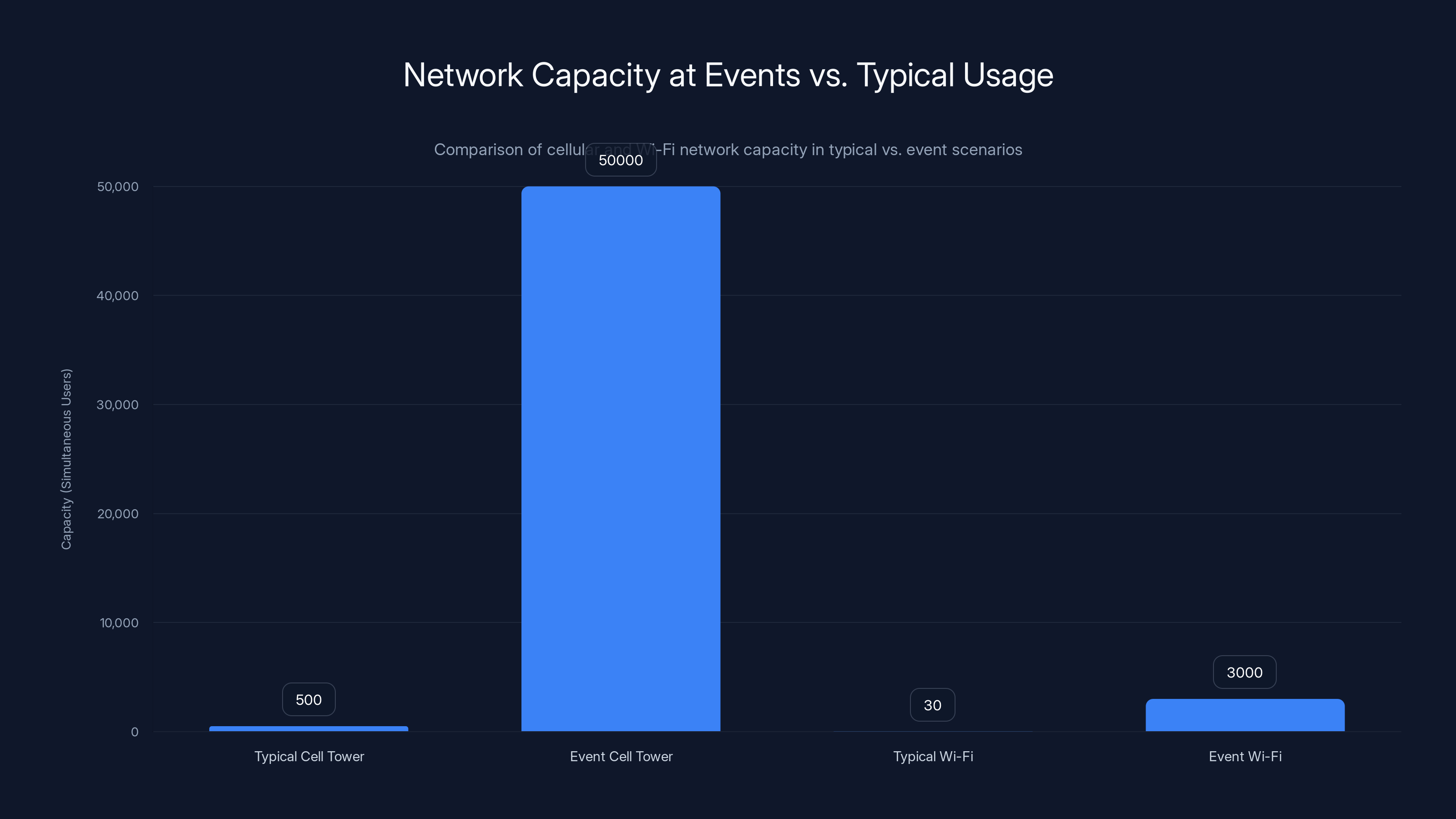

Cellular and Wi-Fi networks face significant capacity challenges during events, with demand far exceeding typical usage scenarios. Estimated data highlights the stark contrast.

Network Slicing and Prioritization

While optical infrastructure solves the backhaul capacity problem, another approach addresses the fairness and prioritization problem.

Network slicing is a technique where you divide a single physical network into multiple virtual networks, each with dedicated resources and different performance characteristics. Imagine a single cellular network that splits into three separate networks: one optimized for high-capacity access (video streaming), one optimized for low-latency access (real-time communication), and one for everything else.

Using slicing, you can guarantee that critical applications get the resources they need even when the network is congested. Emergency services get a dedicated slice. Critical business communication gets a slice. Entertainment streaming gets a slice. Each operates with its own performance guarantees, isolated from congestion affecting the others.

This doesn't solve the underlying interference problem, but it manages the consequences. You can't give everyone unlimited capacity, but you can ensure that priority users and critical applications work reliably.

Network slicing works best when combined with other solutions. You still need adequate total capacity (which is where optical backhaul helps), and you still need good architecture (which is where backhaul/access separation helps). But slicing adds a fairness dimension.

The challenge with slicing is deployment. It requires coordination from device makers, network operators, and application developers. Your phone needs to support slices. The cellular network needs to support slices. Applications need to know how to request appropriate service levels. That level of coordination is difficult across an entire industry.

But for critical applications and high-value users, slicing is increasingly standard. Financial services, emergency response, and enterprise connectivity are being deployed with service guarantees using slicing techniques.

The Reality of Current Solutions

Let's be practical: most venues aren't deploying optical wireless or advanced network slicing today. So what are they actually doing about the connectivity problem?

Some venues have embraced distributed antenna systems (DAS). These are cellular networks where the signal processing happens in a central location, but multiple antennas are distributed throughout the space. A convention center might have fifty or a hundred small antenna points throughout the building, all connected to a central basestation. This improves coverage, but it doesn't fully solve the congestion problem because you're still sharing the same spectrum across all those antennas.

Other venues rely on Wi-Fi, either free or paid. The economics work out: if you provide free Wi-Fi, people consume it inefficiently and you get congested. If you charge for Wi-Fi, you reduce demand to a level the network can handle. Most venues choose paid Wi-Fi as an interim solution.

Some large venues (stadiums, convention centers, concert halls) are now deploying small cell networks specifically designed for dense events. These are lower-power radio systems that cover small areas (maybe a hundred meters) rather than miles. With better planning and more granular deployment, small cells can deliver better performance than traditional macrocell networks.

None of these solutions are perfect. They're all working within constraints. The best venues combine multiple approaches: distributed antenna systems for coverage, small cells for capacity in high-demand areas, optical links for backhaul to separate backbone from access, and network slicing to prioritize critical applications.

But even the best-planned venue will experience connectivity challenges if demand spikes beyond what the infrastructure was designed for. The laws of physics set hard limits.

Software-Defined Networking and Intelligence

Infrastructure improvements are necessary but not sufficient. You also need intelligence in how traffic is managed.

Software-defined networking (SDN) is an architecture where network control is separated from the physical switching infrastructure. Instead of each router or switch making local decisions about where to send traffic, a central controller has a complete view of the network and makes optimization decisions across the entire system.

In a congested event venue, SDN can dynamically reroute traffic, shift load between access points, and prioritize critical communications. When one area of the venue experiences a demand surge, an SDN controller can automatically shift resources from lightly-loaded areas and route traffic to the best available path.

This requires real-time visibility and control, which traditional networks don't have. But modern networks increasingly support SDN principles. Mobile networks support traffic steering. Wi-Fi systems support load balancing across access points. The pieces are coming together.

The next evolution is adding machine learning to the equation. Machine learning algorithms can learn traffic patterns at events. They can predict when congestion will occur and preemptively shift resources. They can identify which applications are consuming disproportionate bandwidth and implement fairness policies. They can detect network problems before they impact user experience.

A truly intelligent network would combine optical backhaul for capacity, distributed small cells for access, network slicing for guaranteed service, and machine learning for real-time optimization. But we're not there yet at most venues.

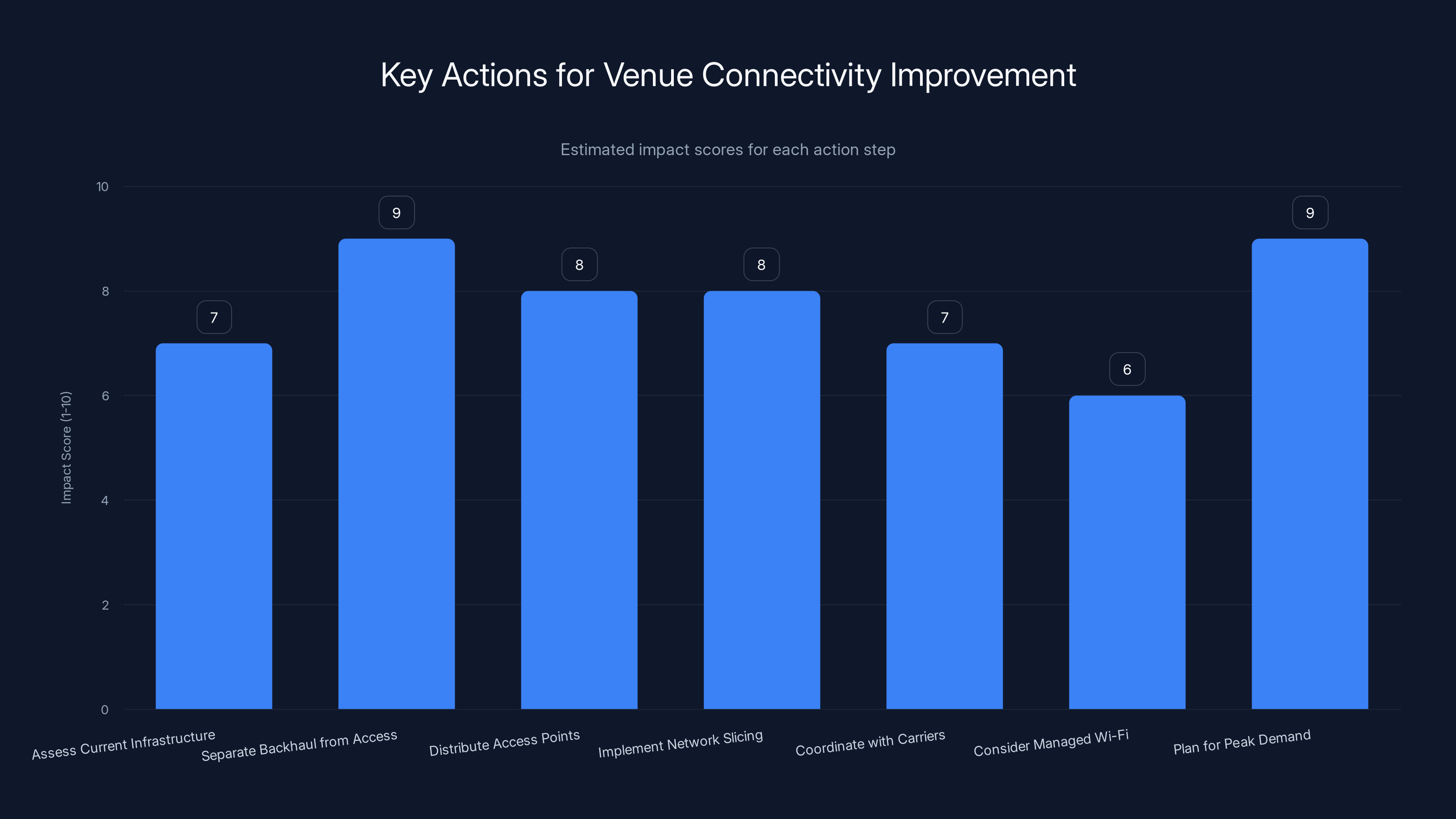

Implementing these steps can significantly enhance venue connectivity, with 'Separate Backhaul from Access' and 'Plan for Peak Demand' having the highest estimated impact.

Spectrum Policy and Regulation

Here's a political reality that impacts everything: spectrum is regulated. Governments control which frequencies can be used for what, and those regulations often don't match the needs of modern dense networks.

Many frequency bands are regulated for specific uses. Some bands require operators to maintain certain geographic coverage. Some bands limit transmit power. Some bands are licensed exclusively to specific carriers. This creates fragmentation where no single entity can deploy optimal infrastructure.

In a convention center, you might have multiple carriers each deploying their own networks using different frequency bands and different technologies. They can't coordinate spectrum allocation. They can't pool resources. So each carrier is trying to deliver service with limited resources in a congested environment.

Some countries have been experimenting with more flexible spectrum approaches. Dynamic spectrum sharing allows different operators to use the same spectrum at different times. Unlicensed spectrum bands like Wi-Fi allow anyone to use shared frequencies. These approaches are more efficient but create new challenges around interference and fairness.

The United States has been opening more unlicensed spectrum (especially in the 6 GHz band) which helps with Wi-Fi capacity. Europe has been more cautious about unlicensed spectrum, maintaining stricter control over frequency allocation. These policy differences impact which technologies deploy in which regions.

For venues, spectrum policy is largely outside their control. But understanding the regulatory environment helps explain why certain solutions are or aren't available in certain regions. Optical wireless solutions are attractive partly because they avoid spectrum regulation entirely.

The Future: Integrated Sensing and Communication

Next-generation wireless research is heading toward something called integrated sensing and communication (ISAC). The idea is that the same radio infrastructure that carries data can simultaneously carry sensing information.

Why does this matter for dense venues? Because it allows the network to understand what's happening in real-time. The network could detect crowd density, movement patterns, and potential congestion before it impacts users.

ISAC could enable a network to say: "Thirty thousand people just arrived in the north hall. Crowd density is extreme. I'm automatically shifting access point resources to the north and rerouting backhaul capacity there." This happens without any user action, without any application awareness.

Sensing combined with AI and machine learning creates networks that adapt to conditions in real-time. A network that understands crowd density, user behavior, and application requirements can optimize its resources dynamically.

Research in ISAC is still early. But major vendors (Qualcomm, Nokia, Ericsson) and research institutions are making significant progress. Six-generation (6G) wireless networks are expected to have ISAC capabilities built in.

For venues in the next decade, ISAC could solve the connectivity problem in crowds by making networks understand crowds. Instead of static infrastructure designed for average demand, you'd have dynamic infrastructure that shapes itself to actual demand.

Economic Incentives and Business Models

Here's an uncomfortable truth: there's often limited economic incentive for venues to solve the connectivity problem.

If a venue charges $80 per day for Wi-Fi, they make money from connectivity. If they deploy free, fast, reliable connectivity, they make no money and spend capital on infrastructure. The business case is backwards.

Some venues have figured out that excellent connectivity drives increased spending. Attendees spend more at events with good connectivity. Event attendance increases. Vendors pay more for booth space. The indirect revenue from improved experience exceeds the cost of infrastructure.

But this realization requires long-term thinking. Many venues are owned by real estate investors whose profit motive is rent and concessions, not attendee experience. They extract value from attendees directly (high Wi-Fi fees) rather than indirectly (better experience driving more spending).

Carriers have different incentives. They want to reduce the cost per bit transported. If they deploy optical backhaul and distributed small cells, they increase their infrastructure cost. But it gives them better spectrum efficiency and better customer experience. Over time, better experience drives market share and reduces churn. But the payback period is years, which is difficult to justify to financial markets.

The solution might require regulation or standardization. If governments required venues to provide free connectivity with minimum speed guarantees (like they're doing with broadband in some regions), venues would have to invest in infrastructure. If industry standards required certain quality of service metrics, carriers would need to meet those standards even when it's expensive.

But those changes face resistance from venues and carriers who profit from the current scarcity.

Investing in monitoring infrastructure can add 10-15% to the initial cost, but it significantly enhances the ability to continuously improve network performance. Estimated data.

What Venues Can Do Today

If you manage a venue and want to improve connectivity, you don't need to wait for 6G or ISAC research. You can implement solutions right now.

Step 1: Assess current infrastructure. Measure actual network performance during events. Data throughput. Latency. Coverage. Device connection success rates. What's the bottleneck? Is it backhaul capacity? Is it access point coverage? Is it spectrum interference?

Step 2: Separate backhaul from access. The single most impactful change is ensuring that high-capacity backhaul doesn't share spectrum with user access. This might mean deploying fiber to feed small cells, or using optical wireless for backhaul. The specific technology matters less than the architectural principle.

Step 3: Distribute access points. Instead of centralized coverage, deploy multiple small access points throughout the venue. Wi-Fi access points every thirty meters rather than every hundred meters. Small cells distributed to serve local demand. Better distribution improves everyone's experience.

Step 4: Implement network slicing for critical services. Ensure that emergency services, venue operations, and critical communications always work. Use network slicing or traffic prioritization to guarantee their service quality.

Step 5: Coordinate with carriers. If possible, negotiate with cellular carriers to deploy infrastructure at your venue. Offer exclusive partnerships. Make it economically viable for them to invest in your specific location.

Step 6: Consider managed Wi-Fi. If deploying carrier infrastructure is difficult, managed enterprise Wi-Fi (with enterprise-grade security, performance monitoring, and user experience optimization) can deliver better results than consumer-grade Wi-Fi.

Step 7: Plan for peak demand. Size infrastructure for peak event demand, not average demand. Many venues plan for average demand and are shocked when peak demand overwhelms the network. Peak capacity determines user experience.

These steps require investment. But they're all implementable with current technology. Many venues simply haven't prioritized it.

The Measurement Problem

One barrier to improvement is measurement. Most venues don't systematically measure network performance during events.

Why? Because measuring network performance is expensive and complex. You need wireless test equipment. You need people who understand how to interpret results. You need to measure at multiple locations and times to get meaningful data.

But without measurement, you're flying blind. You don't actually know whether your infrastructure improvements worked. You don't know whether the congestion problem is backhaul, access, or interference. You're making investments without data.

Fortunately, this is changing. Smaller, cheaper wireless analyzers are available. Cloud-based network monitoring tools let you collect data continuously. Machine learning can analyze large datasets to identify patterns.

Modern venues are increasingly deploying network monitoring infrastructure as part of their connectivity deployment. Wireless sensors throughout the venue continuously measure signal strength, interference, latency, and throughput. This data feeds into analytics systems that identify problems and suggest optimizations.

This kind of continuous monitoring and measurement would have immediately identified the problems at CES. But most venues don't operate this way.

The Psychological Dimension

Here's something often overlooked: the way connectivity failure impacts people psychologically.

When your phone has a strong signal but can't actually do anything, you experience frustration above and beyond the objective performance degradation. Your phone says "4G" or "5G" but messages won't send. That mismatch between signal strength indicator and actual capability is psychologically worse than just knowing the network is congested.

This is why latency matters psychologically even more than throughput. You can accept slow downloads. You can't accept lags in real-time interaction. It feels broken.

Venues can improve perceived experience in ways that don't require infrastructure spending. Being transparent about network limitations helps. "Wi-Fi is congested due to event attendance. We're prioritizing critical systems" is better than silent failure. Offering alternative connectivity options (wired charging stations with ethernet) helps. Redirecting users to low-bandwidth alternatives helps.

But fundamentally, the psychological impact comes from the infrastructure limitations being real. You can't solve a technical problem with communication alone.

Industry Standards and Certification

One potential solution: industry standards for minimum connectivity performance at high-density venues.

Imagine if major event venues were certified for specific connectivity standards. "This venue is certified for 5 Mbps per user during peak events" or "This venue guarantees 50 millisecond latency for critical applications." Certification would drive venue operators to invest in infrastructure.

Some industry bodies are working in this direction. The Wi-Fi Alliance (now called Wi-Fi Alliance, but previously Wi-Fi 6, 6E) is establishing enterprise Wi-Fi certification standards. Cellular standards bodies are establishing dense network deployment guidelines.

But there's no single global standard for venue connectivity. Different regions, different venue types, different industries all have different needs and requirements.

What would help: standardized measurement methodologies, published performance benchmarks, and third-party certification of venue connectivity capabilities. This would enable competition and drive improvement.

But it would also expose current inadequacies, which is why there's limited enthusiasm for standardization from venue operators.

The Role of AI in Network Optimization

Artificial intelligence is increasingly being deployed to optimize network performance in real-time.

AI algorithms can predict traffic patterns, detect anomalies, identify interference sources, and optimize resource allocation. In a dense venue, an AI system could constantly monitor network performance, identify emerging problems, and implement corrections before users notice.

Here's a specific example: AI could identify that a particular section of the venue is experiencing congestion. It could then automatically instruct access points in adjacent areas to shift their beam patterns away from that section, creating more capacity there. It could instruct the cellular carrier to shift resources. It could identify that certain applications (like automatic photo backup) are consuming disproportionate bandwidth and implement traffic shaping to reduce their impact.

All of this happens automatically, without manual intervention.

The challenge with AI-based optimization is that it requires access to network data and control. Some venues have this (they operate their own Wi-Fi network). Some don't (cellular service is operated by carriers). Coordination between venue-operated and carrier-operated networks is difficult.

But as venues invest in more sophisticated infrastructure, AI-based optimization will become standard. The infrastructure exists. The challenge is deployment.

Conclusion: The Choice Ahead

Crowded spaces don't have to suffer from poor connectivity. The technology exists to solve this problem. Optical wireless can provide unlimited backhaul capacity. Distributed small cells can provide excellent access coverage. Network slicing can guarantee critical service. AI-based optimization can maximize efficiency.

But solving the problem requires choices that venue operators, carriers, and equipment vendors have been reluctant to make. It requires investing in infrastructure that doesn't directly generate revenue. It requires deploying technologies that are more sophisticated and more costly than traditional approaches. It requires standardization and coordination that feels difficult in a competitive industry.

The connectivity problem at CES 2026 wasn't a surprise. It's been getting progressively worse for years as events get larger and devices get more numerous. The surprise was that it still hasn't been solved despite everyone knowing it's coming.

Why? Because solving it requires treating connectivity as essential infrastructure worthy of serious investment, not as an afterthought to be addressed with expensive Wi-Fi charges.

Some venues are making that commitment. Major sports stadiums, concert halls, and convention centers are deploying world-class connectivity infrastructure. The difference is noticeable: attendees have better experiences, spend more money, and are more likely to return.

Other venues are watching and waiting, hoping the problem solves itself through technology advancement. It won't. Technology advances create new demands that consume new capacity. What's cutting-edge throughput today becomes minimum acceptable tomorrow.

The venues that will lead in the next decade are the ones making infrastructure decisions now. The ones treating connectivity as a competitive advantage rather than a cost to minimize. The ones deploying optical backhaul, distributed access, network intelligence, and measurement infrastructure.

The quiet crisis in wireless capacity isn't quiet anymore. It's obvious at every major event. The question isn't whether we can solve it. It's whether we will.

FAQ

What causes wireless networks to fail in crowded spaces?

Wireless networks fail in crowded spaces due to a combination of factors: radio frequency interference increases as thousands of devices transmit simultaneously, backhaul infrastructure lacks capacity to handle the data surge, and architecture flaws cause user access traffic to compete with backbone traffic over the same limited spectrum. The network wasn't designed for short, intense bursts of demand from tens of thousands of devices packed into a confined area.

How is radio frequency interference different from spectrum shortage?

Radio frequency interference occurs when signals collide and overlap, degrading performance for all users. Spectrum shortage means there literally isn't enough frequency range. These are different problems requiring different solutions. Many venues mistake interference problems for spectrum shortage, then try to add more radios, which actually increases interference and makes the problem worse.

Can you fix wireless congestion by simply adding more access points?

Not in interference-limited environments. Adding more Wi-Fi access points or cellular radios increases the total interference and noise floor, often degrading performance rather than improving it. The solution requires architectural changes, not just capacity additions. Separating backhaul from access, deploying optical wireless infrastructure, and implementing network intelligence are more effective than simply adding more radios.

What is network slicing and how does it improve event connectivity?

Network slicing divides a single physical network into multiple virtual networks, each with dedicated resources and guaranteed performance characteristics. In a congested event, you might have one slice for emergency services with guaranteed capacity, another for business critical communications, and another for entertainment. Even if the overall network is congested, sliced networks ensure priority users and critical applications maintain performance.

How does optical wireless communication solve connectivity problems in dense venues?

Optical wireless uses focused beams of light (usually infrared) to transmit data point-to-point without competing with radio-based spectrum. An optical link can deliver terabits of data while being invisible to surrounding radio systems. At venues, optical links carry high-capacity backhaul traffic, freeing radio spectrum for user access. This separation allows user-facing resources to be available for users instead of consumed by backbone traffic.

What can venue operators do right now to improve wireless connectivity?

Venue operators can implement several immediate solutions: assess current infrastructure through network performance measurement, separate backhaul from access traffic (fiber-fed small cells or optical wireless), distribute access points throughout the venue rather than relying on centralized coverage, prioritize critical services like emergency communications, coordinate with carriers for infrastructure deployment, and plan infrastructure for peak demand rather than average demand.

Why do streaming video and photo uploads cause such severe network congestion at events?

Streaming video and photo uploads consume disproportionate bandwidth compared to text messaging or voice calls. A single high-quality video stream might consume 5 megabits per second. Thousands of attendees attempting simultaneous uploads during moments worth sharing (performances, announcements) creates demand spikes that exceed network capacity by orders of magnitude. Additionally, these applications are often latency-sensitive, so even moderate congestion degrades quality rapidly.

How does latency impact user experience differently from bandwidth congestion?

Bandwidth congestion makes things slower. Latency makes things feel broken. A download that takes thirty seconds instead of three seconds feels slow but acceptable. A video call with one-second latency feels unusable due to conversation lag. Real-time applications (voice, video calls, interactive games) require sub-100-millisecond latency to feel responsive. Crowded venues often exceed 500-millisecond latency, making real-time applications fail completely.

Are there regulatory barriers to deploying better connectivity infrastructure at venues?

Yes, spectrum regulation significantly impacts which technologies venues can deploy. Cellular spectrum is licensed and carrier-specific, limiting flexibility. Some countries restrict unlicensed spectrum bands. Different regions have different frequency allocations. These regulatory constraints are largely outside venue operators' control but explain why certain solutions that work in one region may not be available in another. Optical wireless solutions partially circumvent these regulatory limitations.

What role will artificial intelligence play in solving wireless congestion problems?

AI will enable real-time network optimization by predicting traffic patterns, detecting congestion before it impacts users, identifying interference sources, and automatically shifting resources. Machine learning algorithms trained on historical event data can anticipate demand surges and preemptively allocate capacity. AI-based systems can identify applications consuming disproportionate bandwidth and implement fairness policies. The technology is emerging now; widespread deployment should occur within five years.

Key Takeaways

- Radio frequency interference, not spectrum shortage, is the physics-based bottleneck limiting wireless capacity in dense environments

- Traditional networks fail in crowds because backhaul and access traffic compete over the same limited spectrum

- Precision architecture separating backhaul from access is more effective than simply adding more radios, which increases interference

- Optical wireless infrastructure can move high-capacity backhaul traffic without interfering with radio-based user access

- Venues can implement practical solutions today including distributed access points, network slicing, and AI-based optimization

Related Articles

- Broadcom's Wi-Fi 8 Hardware Stack: What Enterprise Networks Need to Know [2025]

- Internet Outages in 2025: Why Infrastructure Keeps Failing [2025]

- Google Pixel 10 Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Issues: Complete Troubleshooting Guide [2025]

- T-Mobile Better Value Plan: Netflix, Hulu & Savings Guide [2025]

- Best Mesh Wi-Fi Systems 2026: Ultimate Guide for Home & Gaming [2026]

- Verizon Outage 2025: Complete Timeline, Impact Analysis & What to Do [2025]

![The Wireless Capacity Crisis in Crowded Spaces [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-wireless-capacity-crisis-in-crowded-spaces-2025/image-1-1771663235285.jpg)