Trump's Venezuela Intervention: A Historical Reckoning and Ongoing Crisis

When federal agents escorted Nicolás Maduro in handcuffs across a Manhattan helipad on that January morning, few realized they were watching American foreign policy complete a full historical circle. The imagery alone felt surreal: a democratically elected leader of a sovereign nation placed in custody on US soil without warning, without negotiation, without the messy machinery of diplomacy that typically precedes such dramatic shifts. But for anyone who's studied the mechanics of American power projection in the Western Hemisphere, the scene was disturbingly familiar.

What happened in Venezuela didn't emerge from nowhere. It arrived as the latest chapter in a century-long American tradition of military intervention south of the border, dressed up in 21st-century language but fundamentally unchanged in its core logic: identify a leader we don't like, remove them, and install a replacement more amenable to American interests. The difference this time? The operation happened under a president who doesn't bother hiding the imperial ambitions behind diplomatic language. Within hours of Maduro's arrest, Trump's rhetoric shifted from vague references to democracy and drug enforcement to something far more direct: control of Venezuela's vast oil reserves.

"We're in charge," he announced to reporters. "We're going to run everything. We're going to run it, fix it."

Those sixteen words contain more honesty about American foreign policy than most administrations offer in their entire tenure. And they reveal something crucial about the current moment: we're simultaneously witnessing a throwback to the Cold War interventionism of the 1980s and something uniquely Trumpian—a form of 21st-century imperialism that abandons the pretense of ideological struggle or nation-building and embraces naked resource extraction as national policy.

Understanding what's actually happening requires stepping back from the weekend's dramatic headlines and examining three fundamental truths about American power, Latin American politics, and what happens when an administration decides that centuries-old rules no longer apply.

TL; DR

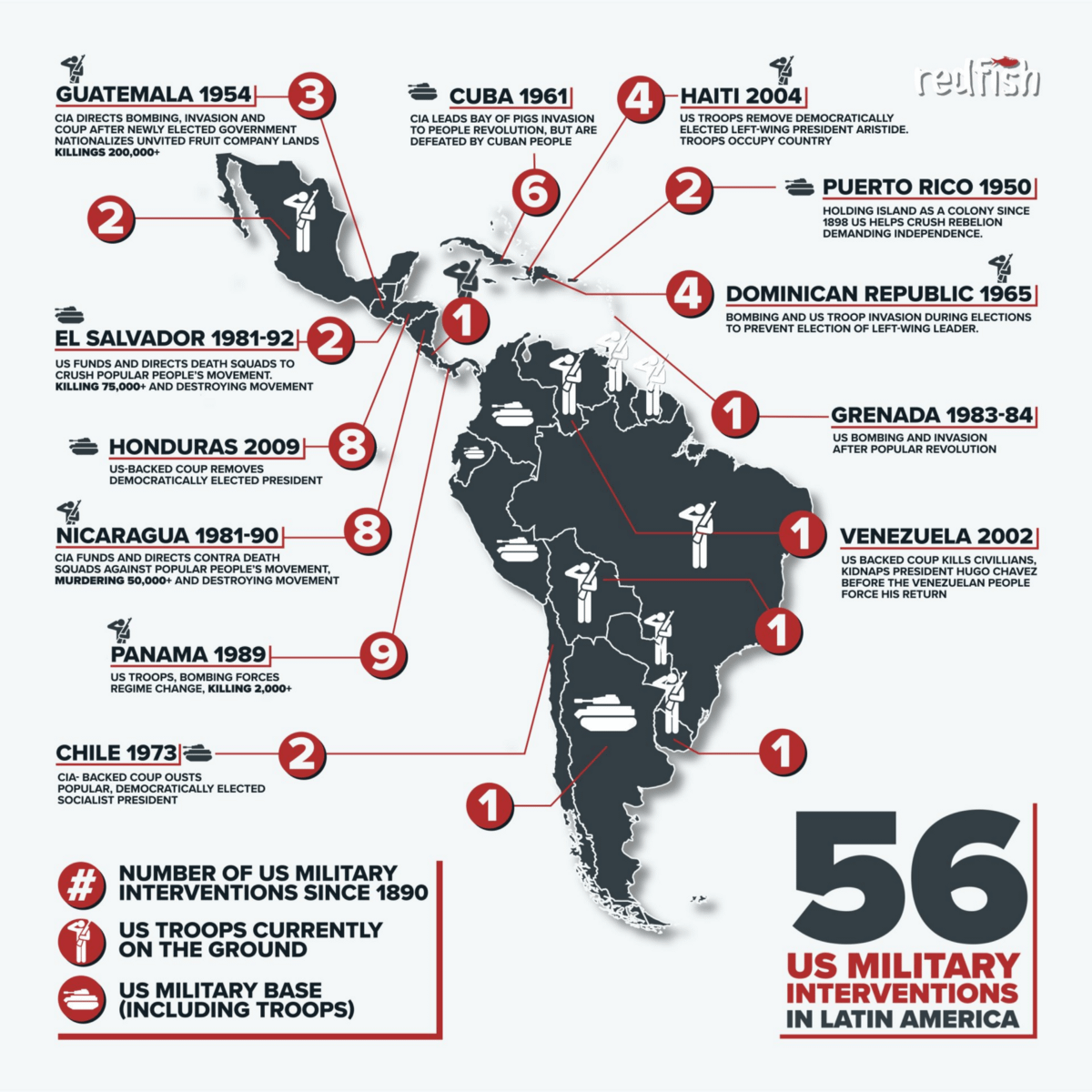

- The US has a century-long history of military coups in Latin America with short-term tactical success but catastrophic long-term strategic failures

- Trump's Venezuela operation combines Cold War rhetoric with 21st-century resource extraction, marking a shift from nation-building to direct economic control

- Oil geopolitics, not democracy promotion, drives current policy, as evidenced by Trump's immediate pivot from democracy-focused rhetoric to explicit control of Venezuelan petroleum reserves

- The operation occurred without congressional authorization, establishing a dangerous precedent for executive power in foreign military interventions

- Historical precedent suggests instability and blowback are likely, requiring careful examination of what comes next in Venezuela and the broader hemisphere

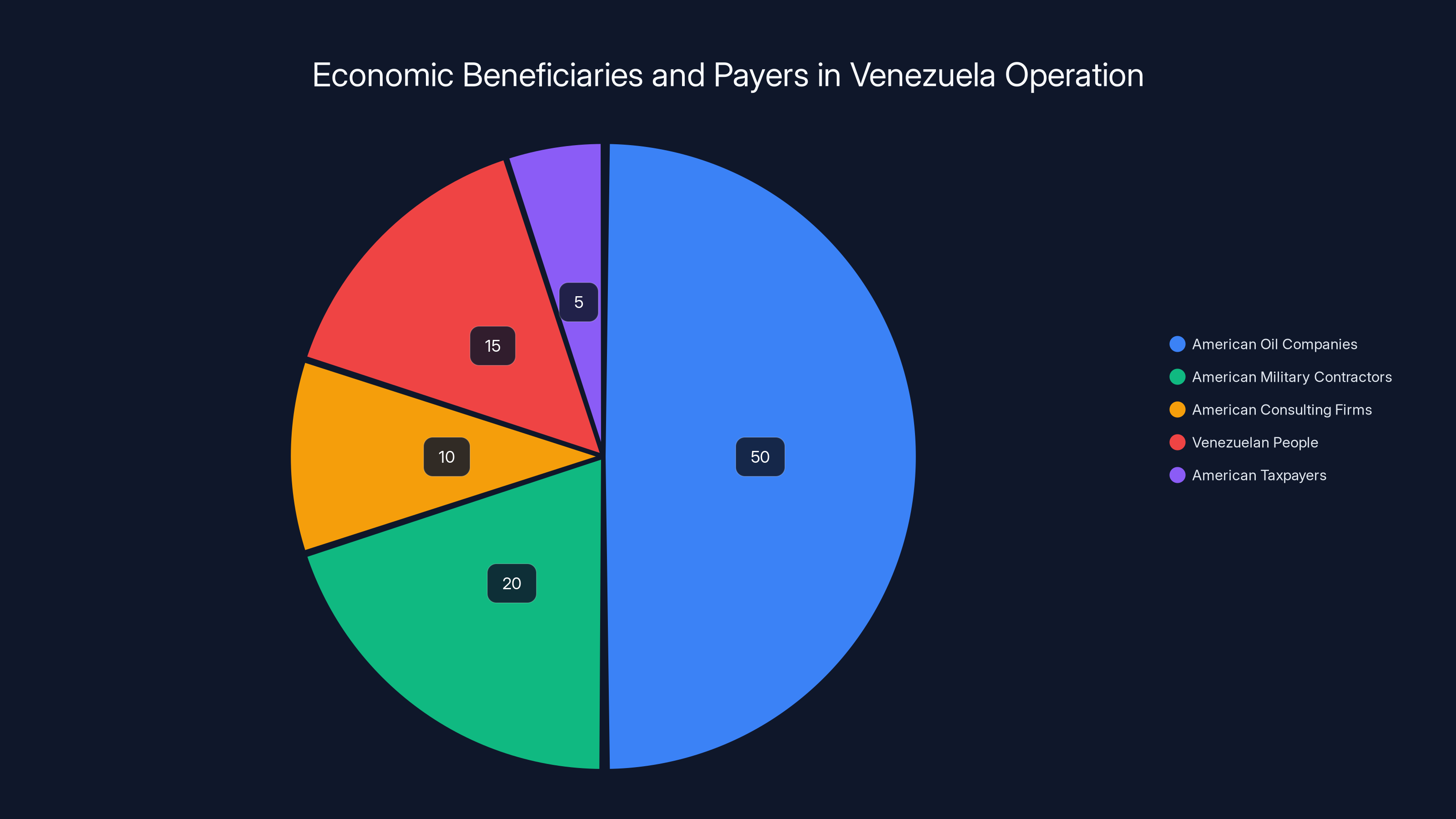

American oil companies are estimated to gain the most from Venezuelan operations, while Venezuelan people bear significant costs. Estimated data.

A Century of Coups: Why This Moment Feels Like 1954, 1961, and 1973

To understand the Venezuela operation, you need to understand something uncomfortable about American history: the United States didn't discover military intervention in Latin America recently. We perfected it over the course of the 20th century, developing playbooks so effective that smaller nations across the hemisphere still speak about them in hushed tones.

Start with the basic geography. The Caribbean basin sits roughly 500 nautical miles from Florida. Throughout the American century, this proximity meant one thing: what happened in Cuba, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, and Central America wasn't some distant foreign policy question. It was treated as an extension of the American sphere of influence, a region where Washington believed it held the inherent right to determine who governed and how.

The occupation of Haiti lasted nineteen years. The on-and-off occupation of Nicaragua stretched for twenty-one years. Cuba saw American troops come and go across multiple decades. These weren't aberrations. They were policy.

But here's what's instructive about the early period: brute military force worked quickly. You could land Marines, remove an inconvenient leader, establish order, and move on. The complexity came later, when you had to build something lasting from the ashes.

By the time the CIA came into being in 1947, the calculus had shifted. Direct military occupation looked bad internationally. What looked better was a coup, the messier and more locally-driven it appeared, the more plausible deniability you maintained. The CIA's first great success came in Guatemala in 1953, when the agency supported the military overthrow of democratically elected president Jacobo Árbenz.

Arbenz's crime? He proposed land reform that threatened the interests of the United Fruit Company, one of the dominant economic forces in Central America. The CIA, working with operatives like the future Watergate burglar E. Howard Hunt, orchestrated a disinformation campaign painting Árbenz as a communist threat. The operation succeeded brilliantly. Árbenz fell, a military junta took power, and American business interests were protected.

The human cost came later: Guatemala descended into a civil war that lasted thirty-six years and killed over 200,000 people, mostly indigenous civilians. But that was Guatemala's problem, not America's. The operation was deemed a success.

This same CIA playbook got recycled for Cuba in 1961. The Bay of Pigs invasion aimed to replicate the Guatemala model: CIA-trained operatives would land, the Cuban population would rise up, Fidel Castro would fall, and everything would return to normal. Except it didn't. Castro's forces were more capable than expected. Air support didn't materialize as planned. Over 100 freedom fighters died on the beaches, more than 1,200 were captured, and the operation became one of the Kennedy administration's first major foreign policy disasters.

The failure didn't end American meddling. It just made it more creative. In the Dominican Republic in 1961, CIA-backed figures assassinated the dictator Rafael Trujillo. In 1963, the CIA supported a coup in Ecuador. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, American intelligence services backed coups and counter-coups across the hemisphere: Brazil in 1964, Chile in 1973, Argentina multiple times throughout the period. When direct coups became politically difficult, the CIA shifted to supporting right-wing militias and insurgent groups, most notoriously in Central America during the Reagan years.

What's remarkable about this entire pattern is how consistent it was. Republican and Democratic administrations both participated. Eisenhower approved Guatemala. Kennedy approved the Bay of Pigs. Johnson watched the Dominican intervention unfold. Nixon and Kissinger orchestrated the Chile coup. Reagan filled the region with CIA operatives, weapons, and support for anti-leftist forces throughout Central America.

The interventions shared another consistent feature: they almost never achieved their stated objectives. Yes, the coups succeeded in removing leaders America didn't like. But what came next? Almost universally worse than what preceded it.

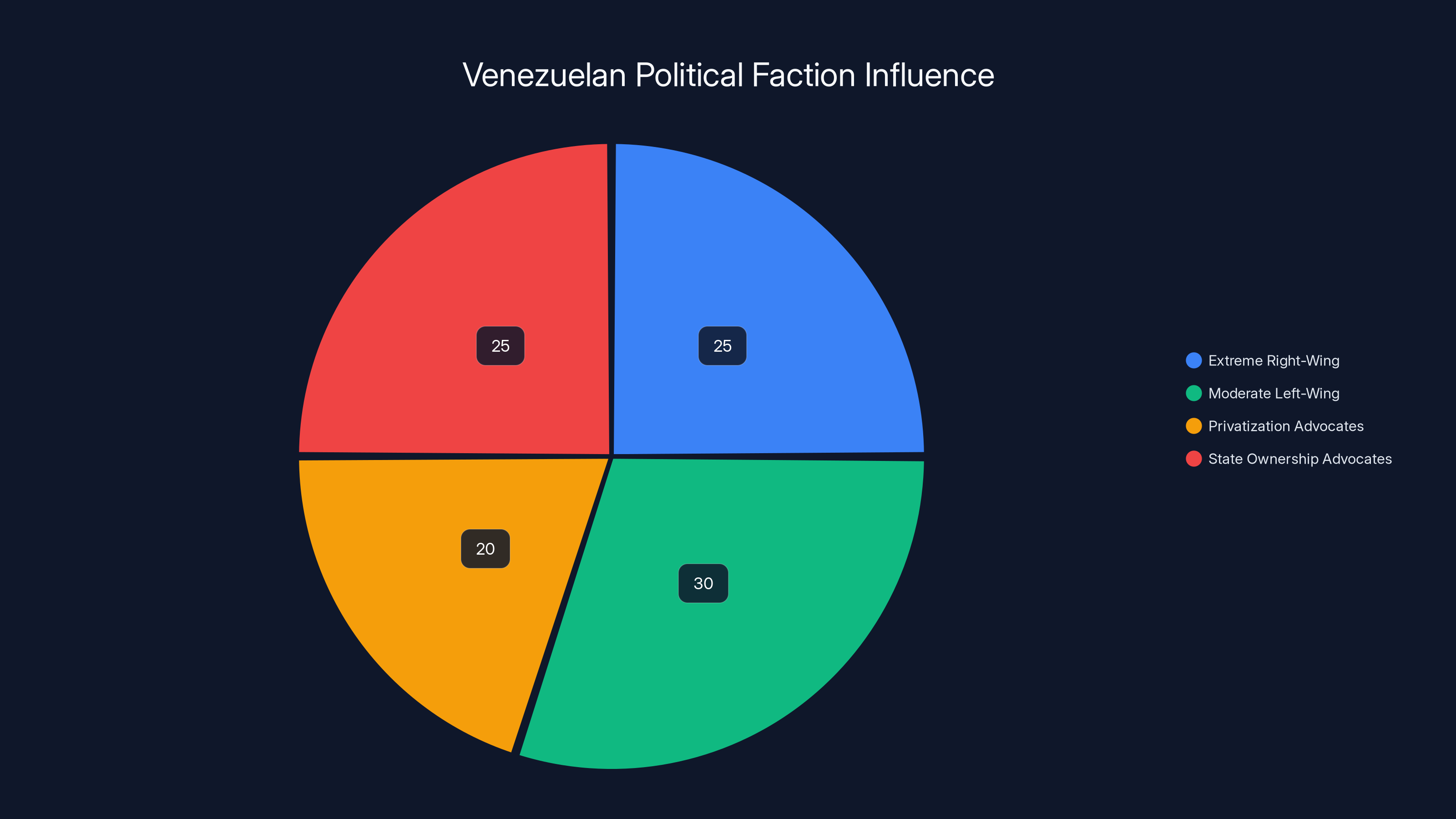

Estimated distribution of influence among Venezuelan opposition factions shows a balanced mix of extreme right-wing, moderate left-wing, and economic policy advocates. Estimated data.

Oil, Ideology, and the Maduro Problem

Venezuela's relationship with American power has always revolved around one substance: petroleum. Venezuela contains the world's largest proven oil reserves, estimated at over 300 billion barrels. For over a century, control of those reserves has been the central fact of Venezuelan politics and Venezuela's relationship with the United States.

When Hugo Chávez came to power in 1998, he spoke constantly about oil nationalism, about reclaiming Venezuela's resources for Venezuelans, about reducing the country's dependency on American markets. The rhetoric was radical, but it tapped into something real: a sense among ordinary Venezuelans that their nation's greatest natural resource was being extracted and controlled by foreign corporations and foreign governments for foreign profit.

Chávez used oil wealth to fund social programs, schools, healthcare. For the first time in Venezuelan history, poor people saw tangible benefits from the nation's oil reserves. They voted for Chávez repeatedly. He won election after election, mostly fairly.

When Chávez died in 2013, Nicolás Maduro inherited the government, the oil industry, and a growing economic crisis. Oil prices had begun declining. Mismanagement and corruption were rampant. The social programs Chávez had funded became economically unsustainable. The Venezuelan economy entered a catastrophic free fall.

By the time Maduro ran for reelection in 2024, Venezuela was in genuine crisis. The currency had collapsed. Basic goods were scarce. Millions had fled as refugees. The promise of oil nationalism had curdled into economic devastation and authoritarian crackdown.

Here's where the narrative gets complicated. Maduro's government was genuinely authoritarian, genuinely corrupt, genuinely destructive to Venezuelan citizens. But the opposition to Maduro had its own problems. The most prominent opposition figure, Juan Guaidó, had claimed to be Venezuela's legitimate president at one point, only to eventually flee the country. The opposition was fractured, sometimes aligned with extreme right-wing elements, often more interested in American approval than in actually delivering governance.

Most importantly, from Washington's perspective: Maduro had continued Chávez's oil nationalism. He hadn't welcomed back the American corporations that had been partially expropriated under Chávez. The oil that Venezuela was pumping wasn't flowing to American refineries at American-negotiated prices.

That's the context in which the January 2025 operation occurred. Not a popular uprising against an unpopular dictator. Not a carefully planned liberation. But an American military operation, executed without congressional approval, that removed the sitting president of a sovereign nation and detained him on American soil.

The Illegality and Unprecedented Nature of the Operation

Let's be direct: what Trump authorized in Venezuela appears to violate multiple layers of international and domestic law.

International law, specifically the UN Charter, prohibits military action against sovereign nations except in cases of self-defense against armed attack or with explicit Security Council authorization. Venezuela didn't attack the United States. No Security Council resolution authorized military intervention. By any reading of international law, the operation was unlawful.

Domestic law creates equal problems. The War Powers Resolution of 1973, passed in the aftermath of Vietnam, requires the president to notify Congress within 48 hours of committing armed forces to military action and to seek congressional authorization within 60 days. Trump didn't notify Congress before the operation. He certainly didn't seek authorization. He acted unilaterally, presenting Congress and the American public with a fait accompli.

There's a reason this matters beyond legal niceties. The Framers of the Constitution deliberately split war-making power between the executive and legislative branches. Presidents can move quickly in genuine emergencies, but sustained military action requires congressional debate and authorization. That's not a bug in the system. It's a feature designed to prevent exactly what happened: a president unilaterally deciding to remove a foreign leader and occupy his nation without legislative oversight.

Trump's defenders argued that the operation was brief and surgical, more like a targeted special operations raid than a sustained military invasion. But that argument misses the point. The fact that you can execute something quickly doesn't make it legal if it violates the law. A bank robbery executed with precision is still a bank robbery.

More troubling still is what the operation signals. If a president can unilaterally arrest a foreign leader on American soil without congressional authorization, what exactly can't a president do? What constraints remain on executive power in foreign affairs? The Venezuela operation suggested that in Trump's view, the answer is: not many.

Historians of executive power noted the precedent immediately. Every president who comes after Trump now knows they can cite this operation as justification for their own unilateral foreign military actions. The guardrails around presidential war-making, already eroded by decades of unauthorized military actions, had just been pushed back further.

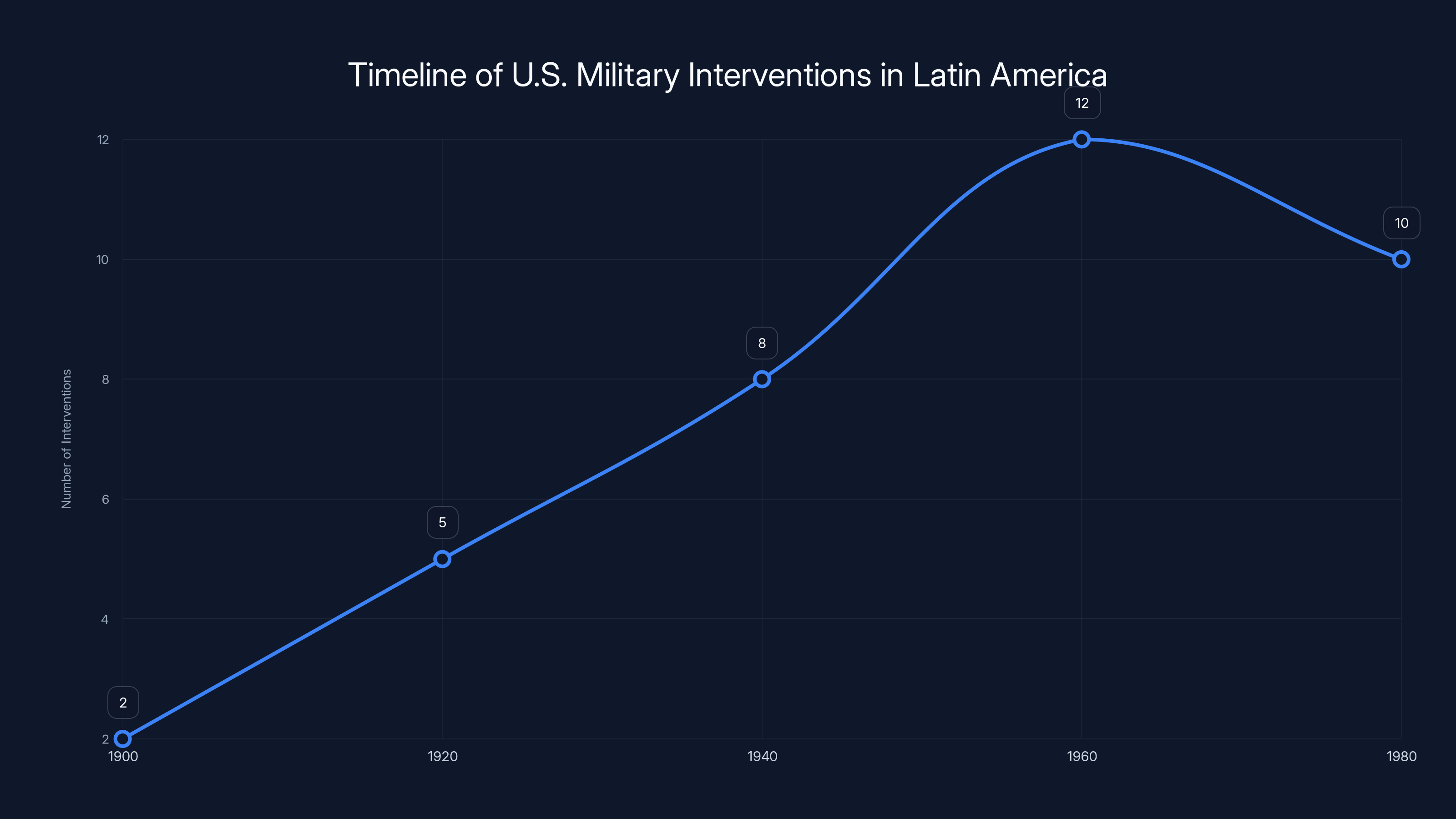

The chart shows an increase in U.S. military interventions in Latin America, peaking around the 1960s. Estimated data based on historical events.

The Rhetoric Shift: Democracy to Oil in 48 Hours

One of the more revealing aspects of the Venezuela operation was how quickly Trump's public justification shifted. In the initial hours, the talking points followed the standard script: Maduro was a dictator, the operation was about restoring democracy, the US was supporting the Venezuelan people against authoritarianism.

Then, on Sunday afternoon, while aboard Air Force One, Trump abandoned the pretense entirely.

"We're in charge," he said. "We're going to run everything. We're going to run it, fix it."

He began threatening Colombia, Ecuador, Panama. He mused about annexing Greenland. He invoked something he called the "Donroe Doctrine," explicitly comparing his actions to the Monroe Doctrine, the 1823 declaration that the Western Hemisphere was America's sphere of influence and that European powers had no business intervening there.

Except Trump's version wasn't about keeping Europeans out. It was about establishing American control and extraction rights. It was, in the clearest possible terms, a statement that the US government now believed it had the right to overthrow leaders in the hemisphere and direct their nations' resources toward American benefit.

Within 48 hours, Trump had also signed orders beginning the process of assuming control of Venezuelan oil revenues, directing those profits toward American national interests rather than toward Venezuela's government or reconstruction efforts.

This shift reveals something fundamental about Trump's worldview. He doesn't believe in nation-building. He doesn't believe in the long, messy project of trying to establish democracy in other countries. Those projects, from Trump's perspective, are expensive drains on American resources that benefit American contractors and consultants while delivering nothing of value to ordinary Americans.

What Trump believes in is extraction. Take the resources, put them to American use, and move on. It's a more honest form of imperialism than what came before, and precisely because of that honesty, it's more dangerous. At least nation-building, however flawed and often counterproductive, aspired to leave something behind. Extraction is fundamentally exploitative. It assumes that some regions exist primarily to supply resources to more powerful nations.

Economic Interests: Who Benefits and Who Pays

Understanding the Venezuela operation requires understanding the economic players who stand to benefit and those who will pay the costs.

The immediate economic beneficiary is clear: American oil companies. Venezuela's proven reserves dwarf any other nation's. If American corporations can access those reserves at favorable terms, it reshapes global energy markets. It reduces American dependency on OPEC pricing. It channels billions in oil revenues toward American corporations instead of Venezuelan state ownership.

The major American oil companies had been largely shut out of Venezuela since Chávez's expropriations in the early 2000s. A government friendly to American interests and American corporate access represents a direct path back to Venezuelan resources. Estimates suggest that Venezuelan oil at American-negotiated prices could add $40-60 billion annually to corporate profits over the next decade.

Secondary beneficiaries include American military contractors, who will be hired to train and equip whatever government structure emerges in Venezuela, and American consulting firms, who will be hired to rebuild Venezuelan government institutions. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars generated hundreds of billions in contracts for these firms. A Venezuelan reconstruction, even a modest one, could generate tens of billions.

Who pays the costs? The Venezuelan people, primarily. Military operations create casualties. Economic disruption creates hardship. The transition from a resource-nationalist government to a resource-extractive one means that Venezuelan citizens see less of their nation's oil wealth benefit them directly.

Americans also pay a cost, though less visibly. The military resources deployed to oversee the operation, the intelligence community staff devoted to monitoring the situation, the diplomatic efforts required to manage the international fallout. These are real costs, even if they're largely invisible in the federal budget.

Cuba and other nations who had close relationships with Venezuela face costs as well. The operation signals to them that American military dominance remains the ultimate arbiter of regional politics, that their own governments remain dependent on American tolerance for their continued existence.

What's economically notable is how one-sided the benefit distribution is. A relatively small American corporate sector benefits substantially. A much larger number of Venezuelans and other regional actors pay costs. This imbalance is historically consistent with American interventions in the hemisphere.

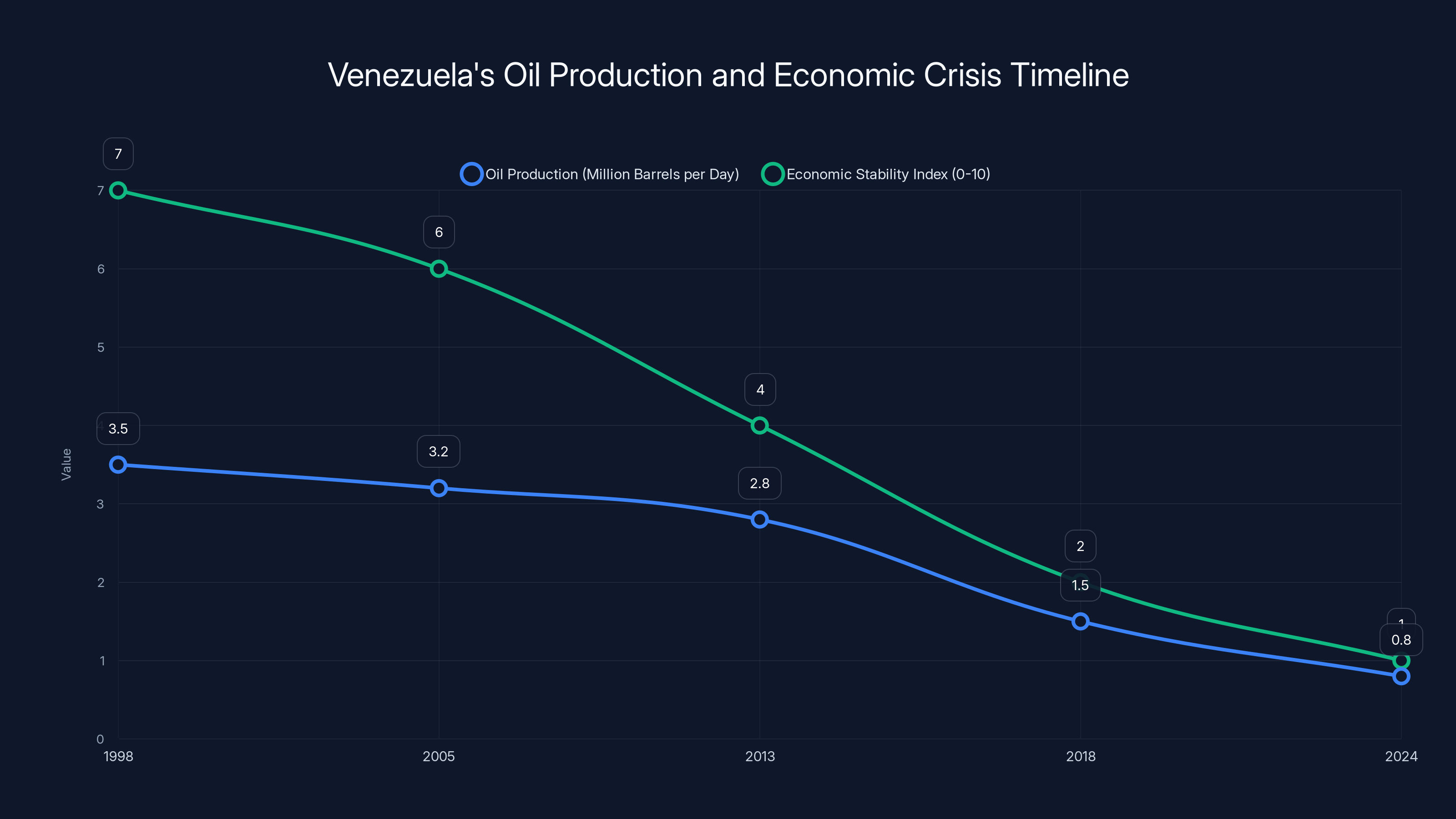

Estimated data shows a decline in oil production and economic stability from 1998 to 2024, highlighting the impact of political and economic challenges in Venezuela.

Regional Implications: What Venezuela's Neighbors Are Thinking

To understand the regional implications of the Venezuela operation, consider how it lands in the capitals of neighboring nations.

In Colombia, the government faces a difficult position. Colombia has signed trade agreements with the United States and has generally maintained alignment with American foreign policy preferences. But Colombia's population is nervous about the precedent being set. If the US will unilaterally arrest the leader of a neighboring nation, what prevents it from doing the same to Colombia under different circumstances?

In Ecuador, memories of the 1963 CIA-backed coup remain fresh in historical terms. Ecuadorian leaders are acutely aware that American foreign policy shifts can suddenly reshape their nation's politics. The Venezuela operation is a reminder that no amount of strategic alignment guarantees American respect for sovereignty.

In Brazil, the government is carefully watching to see what happens next. Brazil is the largest economy in South America and considers itself a regional leader. The idea that the US would undertake a major military operation in the hemisphere without Brazilian consultation, much less cooperation, is concerning. It suggests a diminished role for Brazil in regional affairs.

In Cuba, which has supported the Maduro government and allowed it to use Cuban advisors, the operation is a direct blow. It signals that the Trump administration is willing to confront Cuban interests in the hemisphere, potentially setting the stage for increased American pressure on the Cuban government itself.

Across the region, the message is stark: if you fall out of favor with Washington, and particularly if you control resources that Washington wants, your government's survival is not guaranteed. The internal rules that had constrained American intervention since the Cold War's end, the diplomatic norms that had created some minimum threshold of international legitimacy for US actions, have been set aside.

Historical Precedent: What Happens After a Coup Succeeds

Here's where the historical pattern becomes most concerning: American-backed coups almost always succeed in the short term and almost always create problems in the long term.

Guatemala provides the clearest example. The 1954 CIA operation removed Jacobo Árbenz successfully. The coup took place in a matter of days. By most conventional measures, it was a brilliant covert operation: minimal American casualties, quick success, plausible deniability.

What followed was thirty-six years of civil war that killed over 200,000 people, mostly indigenous civilians. Successive military governments used the post-coup period to consolidate power, eliminate opposition, and conduct what human rights organizations eventually classified as genocide against indigenous populations.

By 1991, when the Guatemalan civil war finally ended, the nation had been devastated. Its economy was shattered. Its social fabric was torn. Hundreds of thousands of refugees had fled. Multiple generations had lived under the shadow of violence.

Was the CIA coup responsible for all of that? No. But the operation removed the one leader who had been attempting to address the structural inequalities that fueled the conflict. By replacing him with a series of military rulers committed to the status quo, the coup operation set conditions for decades of violence.

Chile provides another instructive example. The 1973 CIA-backed coup removed Salvador Allende and installed Augusto Pinochet. The coup succeeded immediately. Pinochet's regime then spent seventeen years conducting systematic repression: political prisoners, torture, disappearances, killings. An estimated 3,000 people were killed. Another 1,200 were disappeared, their fates unknown.

When democracy finally returned to Chile in 1990, the nation faced a legacy of violence and trauma that affected policy decisions for decades. The economic inequality that Allende had tried to address remained. In some measures, it had worsened. The coup had solved one problem (American frustration with Allende) by creating much larger problems (political violence, economic inequality, institutional trauma).

Brazil in 1964 followed a similar pattern. Argentina in 1976 followed a similar pattern. Across Latin America, the story repeated: coup succeeds, military takeover consolidates power, repression increases, violence spreads, eventual transition to democracy leaves the nation scarred and economically damaged.

What's remarkable is how consistent this pattern is and how little it seems to inform American decision-making. Each new administration that considers intervention believes their coup will be different, that they'll support a leader who'll behave responsibly, that the outcome won't be another cycle of violence. And yet the pattern repeats.

Venezuela might be different. Maybe the transition will be smoother. Maybe a new government will be established without sustained violence. But the historical precedent suggests that's unlikely. The removal of a sitting president, however unpopular, creates a legitimacy vacuum. Other potential leaders, seeing that the US will remove those who fall out of favor, have incentives to demonstrate superior alignment with American interests, which often means more extreme policies. The initial tactical success of the coup obscures the long-term strategic risks.

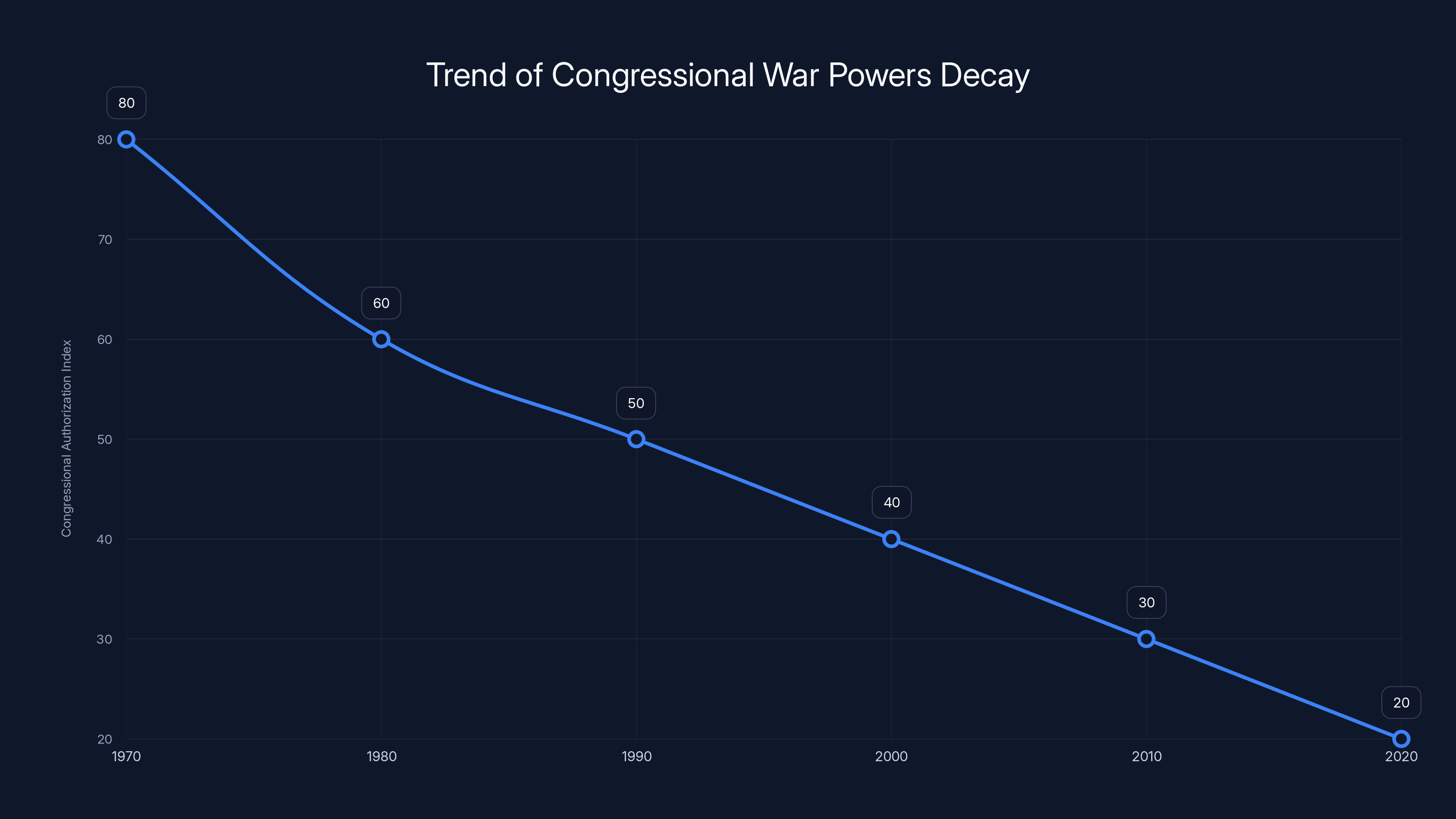

The chart illustrates the steady decline in congressional authorization for military actions, reflecting the decay of congressional war powers over the past five decades. (Estimated data)

The Institutional Decay of Congressional War Powers

There's a secondary story lurking beneath the Venezuela operation, and it's arguably more important for American democracy than what happens in Venezuela itself.

For the past fifty years, congressional war powers have been in steady decay. President after president has committed American forces to military action without congressional authorization. Congress has sporadically objected but has generally acquiesced. Presidents have gone to Congress for authorization (as with Iraq in 2003 and Afghanistan in 2001) but more often have simply acted unilaterally, citing emergency powers or the commander-in-chief authority granted them by the Constitution.

The War Powers Resolution was supposed to reverse this trend. Passed in 1973 in the aftermath of Vietnam, it required presidential notification and eventual congressional authorization. But presidents have consistently treated the War Powers Resolution as an inconvenient obstacle rather than a governing law. They've fired missiles at Syria, conducted drone operations worldwide, supported coups and counter-coups, all without explicit congressional authorization.

Trump's Venezuela operation represents an acceleration of this decay. Previous presidents had at least maintained the pretense that they were operating within constitutional bounds. Trump abandoned that pretense. He acted unilaterally, presented Congress with a fait accompli, and didn't even bother asking for retroactive authorization.

Congress's response was muted. Democrats objected on legality grounds but lacked the political power to force any consequences. Republicans either supported the operation outright or remained silent. No mechanism existed to hold the president accountable for violating the War Powers Resolution.

This creates a dangerous precedent for presidential power. If a president can unilaterally arrest a foreign leader without congressional authorization, what exactly cannot a president do? What remaining constraints exist on the president's ability to wage war without legislative approval?

The answer, increasingly, appears to be: not many. The constitutional framework that divided war-making power between the legislative and executive branches has been substantially undermined. Future presidents, of both parties, will view the Venezuela operation as precedent for acting unilaterally in foreign military affairs.

This isn't a partisan issue. The decay of congressional war powers predates Trump. He simply accelerated an existing trend. But acceleration matters. The faster the decay occurs, the sooner the presidency becomes functionally a separate institution from Congress, accountable only to itself and to the voters in presidential elections.

The Intelligence Community's Role and Accountability Gaps

One of the understudied aspects of the Venezuela operation is the role of the intelligence community and the question of how intelligence was used to justify the intervention.

For any military operation of this magnitude, the CIA and other intelligence agencies would have been intimately involved. They would have conducted surveillance, identified targets, assessed risks, provided real-time intelligence support. Their analysis of the political situation in Venezuela would have informed decision-making.

Here's where it gets complicated: intelligence agencies are rarely held accountable when their analysis proves wrong. They provide assessments, decision-makers act on those assessments, and if the outcomes are negative, the political consequences fall on the decision-makers, not on the intelligence analysts who provided the foundation for the decision.

This creates perverse incentives. Intelligence agencies have institutional reasons to support military interventions. Coups and military operations expand their operational scope and budgets. They reduce other nations' capabilities and increase that nation's dependency on American intelligence for its governance. From an institutional perspective, a successful coup is a huge win.

This doesn't mean intelligence analysts are intentionally lying. But it means that institutional biases push them toward supporting aggressive foreign policies. Analysts who raise concerns about overreach or warn about potential negative consequences find their career prospects limited. Analysts who provide optimistic assessments and support military options find institutional support.

In the Venezuela case, we can expect that CIA analysis provided a relatively rosy picture of the operation's prospects and the likelihood of a smooth transition to a stable, American-friendly government. We can expect that alternative viewpoints, skepticism about the wisdom of the operation, and warnings about potential negative consequences received less institutional support.

What we likely won't get is a detailed public accounting of what intelligence assessments were made, how accurate they were, or what assumptions proved wrong. The intelligence community will argue that releasing such details compromises sources and methods. Congress may accept that argument. The public will remain ignorant of how intelligence was used and misused.

This creates an accountability gap. Presidents who wage war without congressional authorization can't be effectively challenged by Congress if the intelligence basis for the war remains classified. The debate about whether the war was justified becomes impossible to have properly.

Estimated data suggests intelligence agencies are perceived to have lower accountability compared to political decision-makers in military operations.

What Comes Next: Occupying and Governing Venezuela

The tactical operation that removed Maduro succeeded. The strategic challenge of what comes next is just beginning.

Venezuela's government institutions are in ruins. Decades of mismanagement, corruption, and brain drain have left the civil service depleted. Hospitals lack basic supplies. Schools are non-functional. The military is fractured. The security forces are unreliable. The economy is shattered.

Into this vacuum, the US will attempt to install a new government. It will likely be some version of the opposition coalition that Trump had supported during Maduro's presidency. But that coalition is fractured. Its various elements have competing visions for what Venezuela should become. Some elements are extreme right-wing. Others are moderately left-wing. Some want rapid privatization. Others want continued state ownership of resources.

The US will attempt to manage these tensions and steer the transition toward a government friendly to American interests, particularly regarding oil access. But history suggests this is difficult. Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya—all experienced American interventions followed by lengthy periods of instability as various groups competed for power in a context where American military force could impose outcomes but couldn't create legitimate governing institutions.

Venezuela faces additional challenges. Its oil infrastructure has deteriorated significantly under Maduro. Getting production back to previous levels will take years and substantial capital investment. The refining capacity to process Venezuelan oil is largely located in the United States or friendly Caribbean nations. The market for Venezuelan oil is constrained. It's not simply a matter of accessing the resource; it's a matter of having the infrastructure and markets to extract and sell it profitably.

Meanwhile, the Venezuelan population is traumatized, displaced, economically devastated. Millions have already fled as refugees. The internal displacement caused by years of economic crisis creates social fragmentation. It will take years to rebuild basic government services, let alone address the underlying economic problems that created the crisis.

The US will face pressure to fund reconstruction. But Trump has shown little interest in nation-building. He's interested in extraction. If the reconstruction of Venezuela's economy isn't seen as directly benefiting American interests, funding will be minimal. This creates the conditions for ongoing instability.

Global Implications: The End of International Law's Constraint on US Power

Perhaps the broadest implication of the Venezuela operation is what it signals about the future of international law and international norms constraining American power.

Since the end of World War II, the international system has been nominally founded on principles established in the UN Charter: respect for national sovereignty, prohibition on the use of force except in self-defense or with Security Council authorization, commitment to international law as governing the relationships between nations.

These principles were always more honored in the breach than in the practice. The US has violated them repeatedly. But there was a pretense of respect. Military actions were justified as self-defense or as being consistent with international law, even when they arguably weren't.

The Venezuela operation represents a departure from that pretense. Trump explicitly invoked the Monroe Doctrine, a unilateral American claim of hemispheric dominance, as justification for the operation. He didn't claim the operation was authorized by the UN or consistent with the UN Charter. He simply asserted American right to act.

This has implications far beyond Latin America. If the US can unilaterally overthrow governments in the Western Hemisphere, what prevents it from doing so elsewhere? What's the legal framework that prevents American military intervention in Asia, Africa, or the Middle East?

For other powerful nations—China, Russia, the EU—the message is clear: international law constrains them but not the United States. The US operates based on its power and its interests, not on legal norms. This is, in a sense, how international relations have always operated. But the pretense of legal constraint has been useful for global stability. Its abandonment raises questions about what frameworks will govern great-power interactions in the future.

It also creates incentives for other nations to develop military capabilities sufficient to constrain American power. If the US won't be bound by international law, why should other nations be? Why shouldn't China pursue military dominance in Asia? Why shouldn't Russia pursue hegemony in Eastern Europe? The norms that have constrained great-power behavior for eighty years rest on the assumption that all powers, including the US, will accept constraints. Abandon that assumption and you're moving toward a more anarchic international system.

The 1980s Replay: Cold War Nostalgia and Modern Realities

Several observers have noted that Trump's approach to Venezuela feels like a Cold War replay, specifically a replay of the Reagan administration's approach to Central America.

The parallels are striking. The Reagan administration provided military support to anti-leftist forces across Central America, from the Contras in Nicaragua to right-wing death squads in El Salvador and Guatemala. The administration believed, sincerely, that it was fighting communism and advancing freedom. Local populations saw military violence, economic disruption, and displacement.

The Reagan Central America policies generated decades of instability. Nicaragua experienced civil war. El Salvador and Guatemala descended into broader conflict. Millions of refugees were displaced. Infrastructure was destroyed. Social cohesion was shattered.

Trump appears to be adopting a similar approach to Venezuela, only more explicitly resource-focused. Rather than framing the intervention as anti-communist crusade, he's framing it as resource extraction. In some ways, this is more honest. In other ways, it's more problematic because it signals that the US is less interested in any governance outcome in Venezuela and more interested simply in controlling its resources.

But here's the crucial difference: the Cold War context provided a strategic logic for American intervention. The US and Soviet Union were competing for global dominance. Preventing Soviet expansion into the Western Hemisphere was a plausible strategic objective. That logic has disappeared. The Soviet Union no longer exists. Russia is far weaker than the USSR was. The strategic logic for American military intervention in Latin America is much weaker than it was during the Cold War.

What replaces that logic in Trump's framework? Resource access, national greatness, imperial assertion. These are thinner justifications than Cold War anti-communism. They're also, historically, what leads to the most destabilizing American interventions.

The Intelligence Community's Incentive Structure for Supporting Interventions

One of the underexamined aspects of the Venezuela operation is the intelligence community's institutional role in supporting it.

The CIA has a vested interest in military interventions. Coups and operations expand agency budgets, increase operational scope, and demonstrate the agency's relevance to policymakers. An intelligence community that warns against interventions risks being perceived as timid or defeatist. One that supports interventions demonstrates that it's actively advancing American interests.

This creates what we might call "intelligence bias toward intervention." The CIA's organizational incentives push analysts toward supporting military options, not just reporting on them neutrally. When analysts raise concerns about a proposed coup, they risk career consequences. When they provide optimistic assessments, they align with organizational incentives.

This doesn't mean individual analysts are compromised or dishonest. It means organizational structures subtly encourage certain types of analysis. The result is that presidents considering military interventions receive intelligence analysis skewed toward supporting those interventions.

In the case of Venezuela, we can expect that CIA analysis provided a relatively optimistic assessment of the coup's likelihood of success and the subsequent transition's smoothness. We can expect that alternative views received less institutional support. But we won't get detailed public accounting of how intelligence was used and where assumptions proved wrong.

This creates an accountability gap. Congress can't effectively oversee military operations if the intelligence basis remains classified. The public can't assess the wisdom of operations if it can't see the intelligence that justified them.

Women, Indigenous Peoples, and the Invisible Costs of Intervention

Most coverage of military interventions focuses on headline metrics: casualties, displaced persons, economic costs. But the impacts on women and indigenous populations are often invisible in these metrics.

Venezuela has a large indigenous population, primarily in the Amazon basin. Maduro's government was, whatever its faults, nominally committed to indigenous land rights and protection. A replacement government aligned with American interests may prioritize resource extraction over indigenous protection. That means pressure on indigenous lands, pressure on indigenous people to cede control of resource-rich territories.

Women have been disproportionately impacted by Venezuela's economic crisis. As social services have collapsed, women have borne the burden of unpaid care work. As the economy has deteriorated, women have been pushed into informal sector work and sex work to survive. Military intervention creates additional vulnerabilities for women: the breakdown of law enforcement during political transitions increases sexual violence, military presence increases trafficking and exploitation.

These impacts are real and significant, but they're rarely foregrounded in discussions of military intervention. The focus remains on big-picture geopolitics. The lived experiences of women and indigenous people remain peripheral to the analysis.

The Broader Pattern: How American Interventions Create Refugee Crises

One of the most significant but often overlooked impacts of American military interventions is the refugee crises they generate.

Venezuela has already produced millions of refugees and internally displaced people. The American intervention will likely accelerate these dynamics. As political instability increases, as economic disruption spreads, more people will flee. They'll go to Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and eventually many will attempt to reach the United States.

From an American political perspective, this creates a problem. The refugee crises in Syria, Afghanistan, and other regions where the US has intervened have become major political issues. A massive Venezuelan refugee crisis would force political reckoning with the costs of the intervention.

Historically, American interventions have generated refugee flows. The Guatemala coup of 1954 eventually produced refugee crises when the subsequent civil war broke out. The Central American interventions of the 1980s produced waves of refugees fleeing violence. Afghanistan and Iraq have generated ongoing refugee populations.

These refugee populations often become sources of domestic political conflict. Receiving countries view them as burdens. Populations in those countries blame the interventions for creating the refugee flows. But the interventions themselves often happen without serious consideration of the refugee consequences.

The Venezuela intervention is unlikely to be different. Officials will express surprise at the refugee flows, blame the refugees for fleeing, and resist taking responsibility for the intervention's consequences.

Democratic Accountability and the Presidency's Constrained Legislature

Fundamentally, the Venezuela operation raises the question of democratic accountability and what it means when a president can wage war without congressional authorization.

The Constitution grants Congress the power to declare war. This was deliberate. The Framers wanted to prevent a single person from having absolute power to wage war. But the decay of congressional war powers has made this constraint increasingly theoretical.

Ineffectual congressional oversight has multiple causes. First, the public is generally disengaged from foreign policy questions unless they directly affect American lives (casualties, refugees). Second, partisan polarization means that congressional opposition to a president's foreign policy can be easily dismissed as partisan rather than principled. Third, war powers require rapid response, which favors executive action over legislative deliberation.

But the fundamental issue is that Congress has allowed itself to be marginalized. It has accepted the president's assertion that the commander-in-chief powers grant the president authority to wage war without congressional approval. It has allowed national security classifications to prevent meaningful oversight. It has accepted the premise that criticizing a military operation is criticism of the troops.

The Venezuela operation shows what this abdication of congressional responsibility looks like. A president unilaterally decides to overthrow a foreign government, presents Congress with a fait accompli, and faces minimal consequences because Congress has no institutional mechanism for asserting its war-making powers.

Fix this and you address one of the fundamental threats to American democracy: the growth of unchecked presidential power. Don't fix it and the presidency continues to accumulate more and more power relative to the legislative branch, ultimately undermining the system of separated powers that the Constitution established.

Precedent and Future Interventions: What This Means for Korea, Taiwan, Iran

The Venezuela precedent will influence future American decisions about military intervention in other contexts.

Consider Taiwan. China claims Taiwan as an illegitimate breakaway province. The US has ambiguously defended Taiwan, neither fully committing to its defense nor renouncing that defense. A conflict over Taiwan is plausible. If such a conflict occurred, the Venezuela precedent suggests that a president could authorize military action without congressional approval, presenting Congress with a fait accompli.

Or consider Iran. There's been longstanding tension with Iran over its nuclear program. Some observers have warned that the Trump administration might attempt military action against Iran. The Venezuela precedent suggests that such action could be authorized unilaterally.

Or consider the Korean Peninsula. North Korea has long been a source of tension. Military action against North Korea is theoretically possible, though practically very risky. But the precedent has been set that a president can authorize such action without congressional approval.

Each of these scenarios involves stakes that dwarf Venezuela. The precedent that the Venezuela operation sets—that a president can wage war unilaterally—carries enormous implications for American foreign policy in the years ahead.

FAQ

What exactly happened in Venezuela in January 2025?

The Trump administration authorized a military operation that resulted in the arrest of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, who was transported to the United States to face federal charges. The operation was executed by US military and intelligence personnel without advance notice to Congress or the international community. It occurred without declarations of war or explicit congressional authorization, marking a significant assertion of unilateral presidential power in foreign military affairs.

Why does Trump believe he has the authority to overthrow a foreign government?

Trump's legal argument rests on the claim that he possesses inherent commander-in-chief powers under the Constitution and that the operation constitutes a justified exercise of those powers. However, this interpretation conflicts with the War Powers Resolution of 1973 and violates the UN Charter's prohibition on military action except in self-defense or with Security Council authorization. The operation has been widely criticized by international law scholars as legally questionable at best.

What are Venezuela's oil reserves and why do they matter?

Venezuela possesses the world's largest proven crude oil reserves, estimated at over 300 billion barrels. These reserves have made Venezuela strategically important to the United States for over a century. Trump's immediate pivot from democracy-focused rhetoric to explicit statements about controlling Venezuelan oil suggests that resource access, not democratization, is the primary motivation for the intervention.

How does this operation compare to previous US military interventions in Latin America?

The Venezuela operation follows a century-long pattern of US military coups in the region, including Guatemala (1954), the Bay of Pigs attempt in Cuba (1961), the Dominican Republic (1961), Chile (1973), and others. However, the Venezuela operation is notable for Trump's explicit abandonment of rhetorical pretense, openly discussing resource extraction rather than disguising the operation as humanitarian intervention or anti-communist crusade.

What does the War Powers Resolution require and did Trump follow it?

The War Powers Resolution requires the president to notify Congress within 48 hours of committing armed forces to military action and to secure congressional authorization within 60 days or withdraw those forces. Trump did not notify Congress before the Venezuela operation, did not seek authorization afterward, and presented Congress with a completed military action as a fait accompli. This represents a clear violation of the resolution's requirements.

What will happen to Venezuela after the military operation?

The United States will attempt to install a new government, likely drawn from the opposition coalition. However, Venezuela faces severe institutional collapse, economic devastation, and social fragmentation. Historical precedent from Guatemala, Afghanistan, Iraq, and other post-intervention contexts suggests that the transition will likely be difficult, protracted, and less successful than hoped. Refugee flows will probably increase significantly.

Does this set a precedent for future military interventions by the US or other powers?

Yes. The Venezuela operation demonstrates that a president can unilaterally wage war without congressional authorization and face minimal consequences. This will likely encourage future presidents of both parties to act similarly. It also signals to other world powers that international law constrains them but not the United States, potentially destabilizing the international system by suggesting that all powerful nations can act unilaterally.

How has the international community responded to the operation?

The operation has received widespread criticism from international legal experts, human rights organizations, and many foreign governments. However, American military power is sufficient that practical consequences remain limited. Some US allies have expressed concern, while others have remained largely silent, reflecting their dependence on American security guarantees.

What does the "Donroe Doctrine" mean and why did Trump use that term?

Trump's invocation of the "Donroe Doctrine" explicitly references the Monroe Doctrine, an 1823 statement claiming the Western Hemisphere as America's sphere of influence. The term suggests that Trump views the region as rightfully within American dominion and that the US has the authority to intervene militarily to advance American interests there. It's a remarkably explicit articulation of imperial ideology.

What are the risks that could emerge from this intervention?

Risks include: political instability and potential violence in Venezuela as various factions compete for power, refugee crises as people flee instability, long-term governance challenges in rebuilding Venezuelan institutions, regional destabilization as neighboring countries fear American military intervention, deterioration of international law norms as powerful nations adopt unilateral approaches, and potential overreach by future American administrations emboldened by this precedent.

Conclusion: Understanding the Moment We're In

The Venezuela operation isn't an aberration. It's the logical conclusion of trends that have been building for decades: the decay of congressional war powers, the growth of unchecked presidential authority, the abandonment of international law as a constraint on American power, and the embrace of resource extraction as a primary motivation for foreign policy.

What makes it remarkable is Trump's explicit honesty about the underlying dynamics. Previous administrations dressed up their interventions in noble rhetoric: anti-communism, democracy promotion, humanitarian concerns. Trump abandoned that pretense. He's explicit that the goal is to control Venezuelan resources and direct them toward American profit.

In some ways, this honesty is refreshing. It's easier to have a real debate about foreign policy when the motivations are clearly stated rather than hidden behind ideological rhetoric. But the honesty also reveals the fundamental problematics of the operation: it represents a return to naked imperialism in an era when international norms were supposed to constrain such behavior.

What happens next will depend on multiple factors. Whether Congress reasserts its war-making powers. Whether international law remains relevant or becomes purely decorative. Whether the transition in Venezuela stabilizes or devolves into prolonged instability. Whether the refugee crises become politically salient enough to force reckoning with the intervention's costs.

Historically, the patterns suggest that the short-term tactical success of the coup will likely produce long-term strategic problems. The removal of Maduro succeeded. But the subsequent governance challenge will be far more difficult. Venezuela's institutions are broken. Its economy is devastated. Its population is traumatized and displaced. Building something stable from that foundation will require sustained commitment, substantial resources, and genuine nation-building—none of which Trump has shown interest in providing.

Meanwhile, the precedent that's been set will reverberate. Future presidents, observing that Congress is unwilling to enforce its constitutional war-making powers, will feel emboldened to wage war unilaterally. The international system, observing that international law constrains other powers but not the United States, will destabilize. The norms that have governed great-power behavior since World War II will erode further.

The Venezuela operation is thus simultaneously a specific military intervention in one country and a broader statement about American power and its relationship to law, democracy, and international norms. Understanding what happened requires understanding both the specifics of Venezuelan politics and the broader historical trajectory that made this moment possible.

What comes next depends on choices we're still in the process of making: whether Congress reasserts its constitutional authority, whether the international community develops mechanisms to constrain unilateral power, whether Americans demand accountability for military interventions conducted in their name. The operation in Venezuela is just the beginning of a process whose endpoint remains genuinely uncertain.

Key Takeaways

- The Venezuela operation represents the logical conclusion of decades of decaying congressional war powers and unchecked presidential authority in foreign military affairs

- Trump's explicit pivot from democracy rhetoric to resource extraction reveals naked imperialism previously hidden behind ideological justifications in American foreign policy

- Historical precedent from Guatemala, Chile, and other post-coup contexts suggests long-term instability and strategic failure are likely despite short-term tactical military success

- The operation violates both the War Powers Resolution and UN Charter, establishing dangerous precedent for unilateral presidential war-making without legislative authorization

- Venezuelan oil reserves and American corporate profit motives are the primary drivers, while the stated justifications about democracy and anti-narcotics efforts were abandoned within 48 hours

- The intelligence community's institutional incentives favor supporting military interventions, creating systematic bias in analysis available to policymakers

- Congressional war powers have been substantially undermined, leaving no effective mechanism to hold the president accountable for unauthorized military operations

- Regional neighbors and international actors now understand that American military intervention is possible without diplomatic process or international legal justification

![Trump's Venezuela Intervention: History, Oil Politics, and Global Fallout [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/trump-s-venezuela-intervention-history-oil-politics-and-glob/image-1-1767696003296.jpg)