The Silent E-Waste Bomb in Your Fitness Tracker

You strap on your smartwatch this morning without thinking twice. Glucose monitor synced to your phone. Fitness tracker counting steps. Blood pressure monitor ready for your evening check-in. These devices feel like they're solving health problems, and in many ways, they are. But here's the part nobody mentions at tech conferences: by 2050, we could be drowning in over a million tons of electronic waste from wearables alone.

A groundbreaking study from Cornell University and the University of Chicago, published in Nature, just dropped a reality check on the wearables industry. The projections are staggering. We're talking about 2 billion wearable units sold annually by 2050, compared to today's 48 million. That's a 42-fold increase. And with each device containing toxic materials, rare earth elements, and components that take centuries to decompose, we're essentially creating a time bomb of environmental degradation.

But here's where it gets interesting. The study revealed something most people get wrong about the environmental cost. You'd think the plastic casings, the silicone bands, the textile straps—that's where the real damage happens, right? Wrong. The plastic isn't the problem. What actually causes 70% of a wearable's carbon footprint is something invisible to the naked eye: the printed circuit board.

That tiny circuit board—the device's "brain"—is the villain in this story. It requires intensive mining operations to extract rare minerals like gold, cobalt, and tantalum. These materials then go through energy-intensive manufacturing processes that pump out greenhouse gases. When multiplied across billions of devices, the scale becomes terrifying. We're not just talking about waste accumulating in landfills. We're talking about 100 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions over the next 25 years, just from wearable health devices.

This isn't abstract environmental concern. This is about how the devices you're wearing right now are baked into a supply chain that's fundamentally unsustainable. And the thing is, it doesn't have to be this way. The same researchers who published the warnings also identified concrete solutions. Modular design. Alternative materials. Reusable components. The technology exists to flip this trajectory.

But the industry isn't moving fast enough. Why? Because there's money in replacement cycles. When a device is sealed together with proprietary adhesives and non-replaceable batteries, customers have no choice but to buy a new one. Every three to four years, another device ends up in e-waste streams. Every new purchase means another hit to the planet's carbon budget.

Let's dig into what's actually happening, why it matters more than you think, and what actually needs to change.

TL; DR

- The Scale Problem: Wearable health device demand could hit 2 billion units annually by 2050, up from 48 million today—a 42-fold increase

- The Waste Crisis: This growth could generate over 1 million metric tons of e-waste and 100 million metric tons of CO2 emissions through 2050

- The Real Culprit: Printed circuit boards account for 70% of a device's carbon footprint, not the plastic casings people assume are the problem

- The Solution Path: Modular design, alternative materials like copper instead of rare minerals, and reusable components can dramatically reduce environmental impact

- The Urgency: Without design changes, the wearables industry will become one of the largest contributors to electronic waste and carbon emissions in the health tech sector

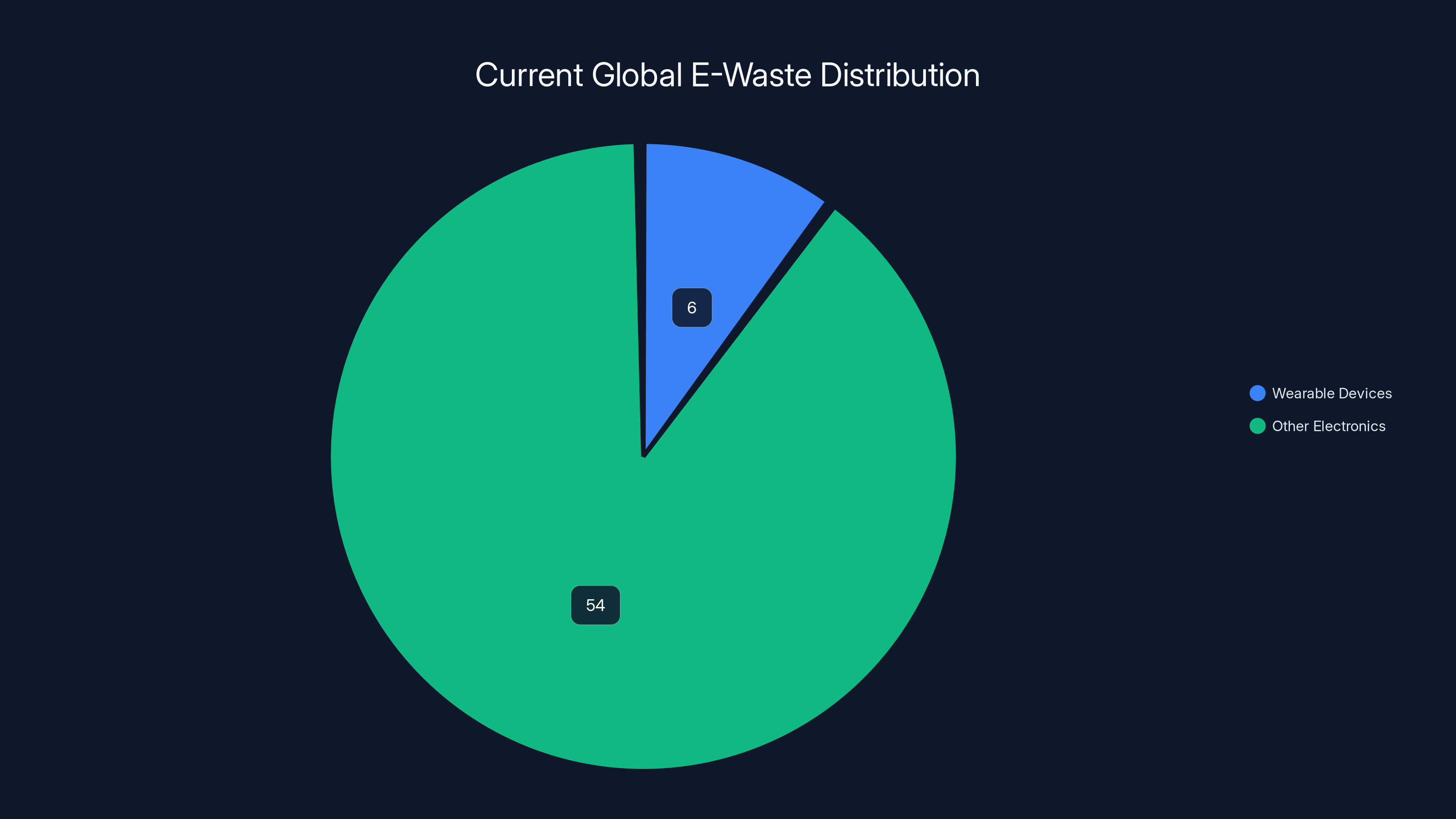

Wearable devices currently contribute approximately 6 million metric tons to global e-waste, representing about 10% of the total 60 million metric tons generated annually by all electronics. Estimated data.

Understanding the Wearables Explosion

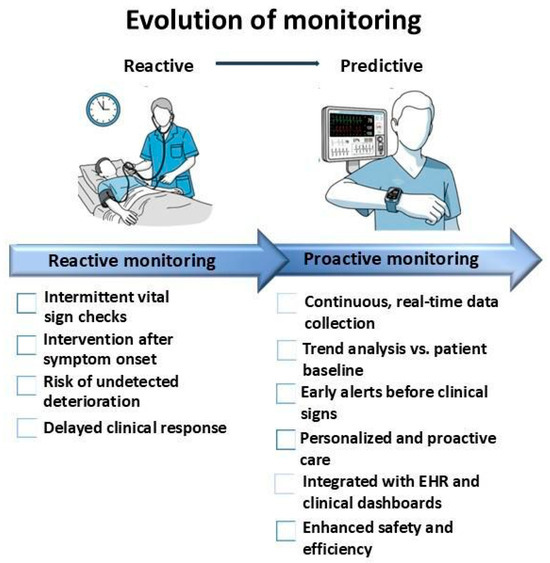

Wearable health technology has transitioned from novelty to necessity in just over a decade. What started as fitness enthusiasts strapping on basic step counters has evolved into a sophisticated ecosystem of continuous monitoring devices. We're not just counting steps anymore. We're tracking heart rate variability, oxygen saturation, glucose levels, blood pressure, sleep architecture, stress markers, and electrocardiograms.

The market growth reflects real demand. Healthcare systems globally are shifting toward preventative medicine. Patients want data. Doctors want continuous monitoring instead of annual snapshots. Insurance companies are incentivizing device adoption because the data helps identify health risks before they become expensive interventions. It's a virtuous cycle from a health perspective, and a problematic one from an environmental standpoint.

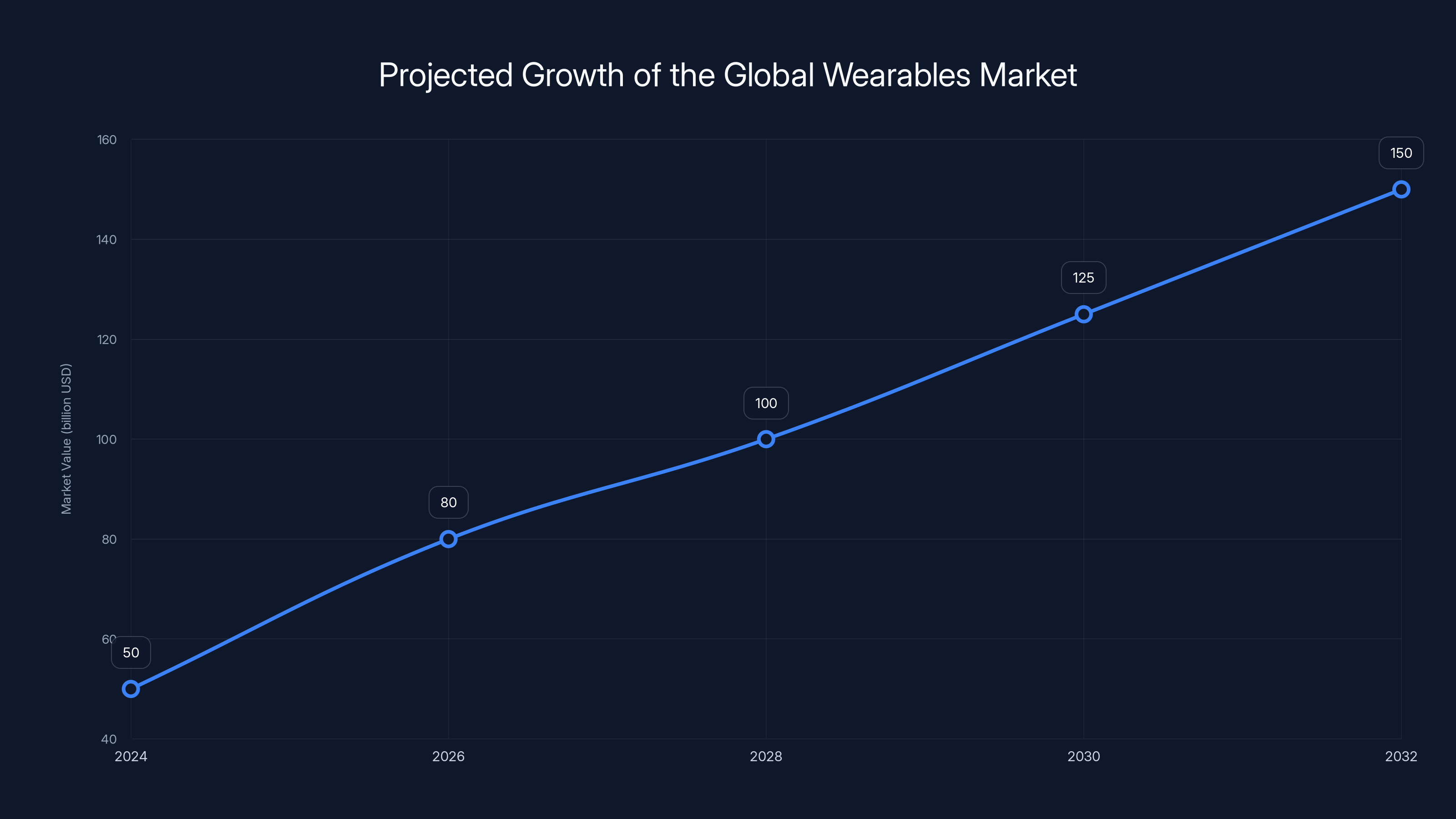

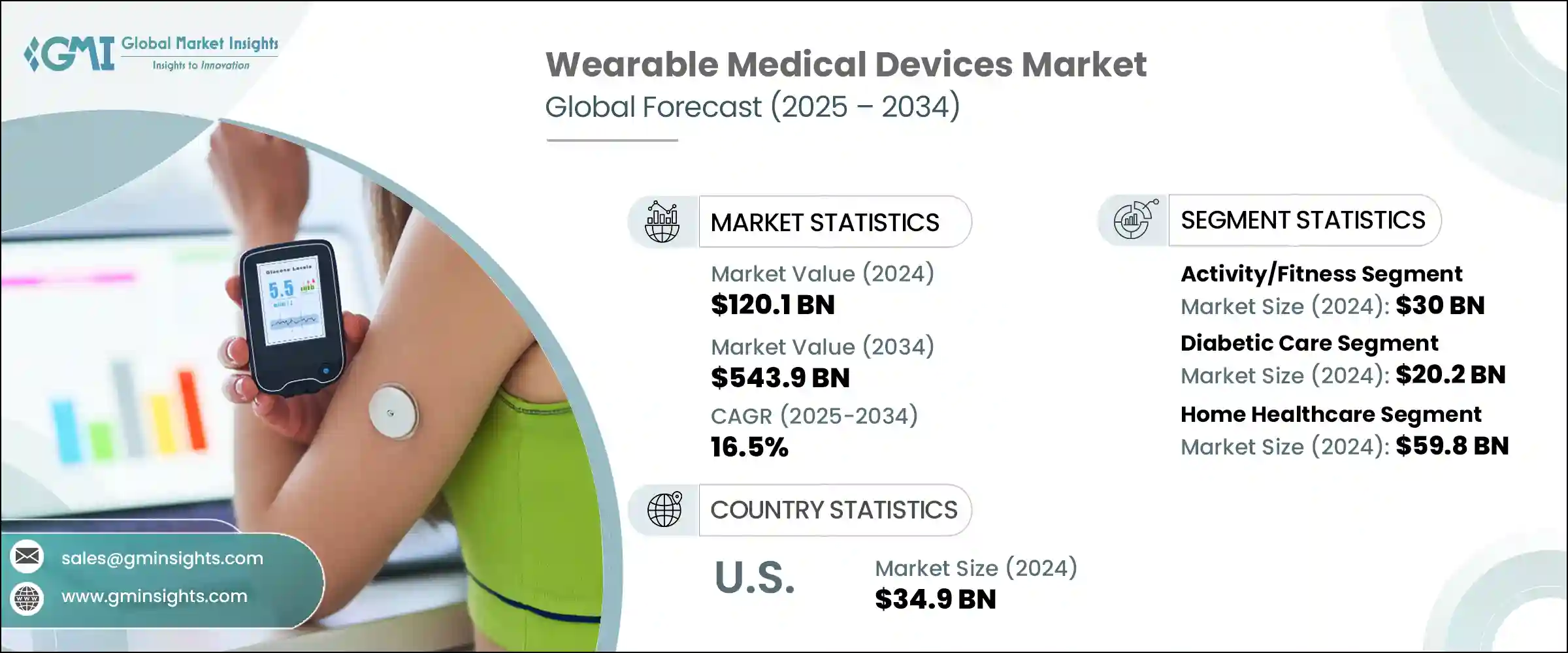

The numbers are worth sitting with. The global wearables market was valued at approximately

What makes this growth trajectory particularly concerning is the adoption curve in developing nations. As smartphone penetration reaches saturation in developed markets, manufacturers are turning to emerging markets with billions of people entering the health-conscious consumer category for the first time. A teenager in India getting their first glucose monitor. A factory worker in Indonesia tracking their vital signs. A retiree in Brazil monitoring their heart. These are massive populations with virtually untapped wearable device adoption rates.

The business model driving this explosion deserves attention. Current wearable manufacturers operate on replacement cycles. Devices are typically expected to last 2-4 years before battery degradation, software incompatibility, or new feature enhancements make them obsolete. The industry hasn't incentivized longevity. Instead, it's built around annual product launches with incremental improvements that make last year's model feel antiquated. A new sensor here. A faster processor there. Better water resistance. Each new generation convinces users it's time to upgrade.

This replacement cycle is foundational to business models at major wearables manufacturers. Planned obsolescence isn't always intentional conspiracy—it's often just what happens when quarterly earnings expectations drive product development decisions. Why spend engineering resources on 10-year durability when you can sell a new device every three years?

The global wearables market is projected to grow from

The Printed Circuit Board Problem

Here's the insight that changes how you think about wearable environmental impact: the circuit board accounts for 70% of a device's carbon footprint. Not the glass. Not the plastic. Not the battery. The circuit board.

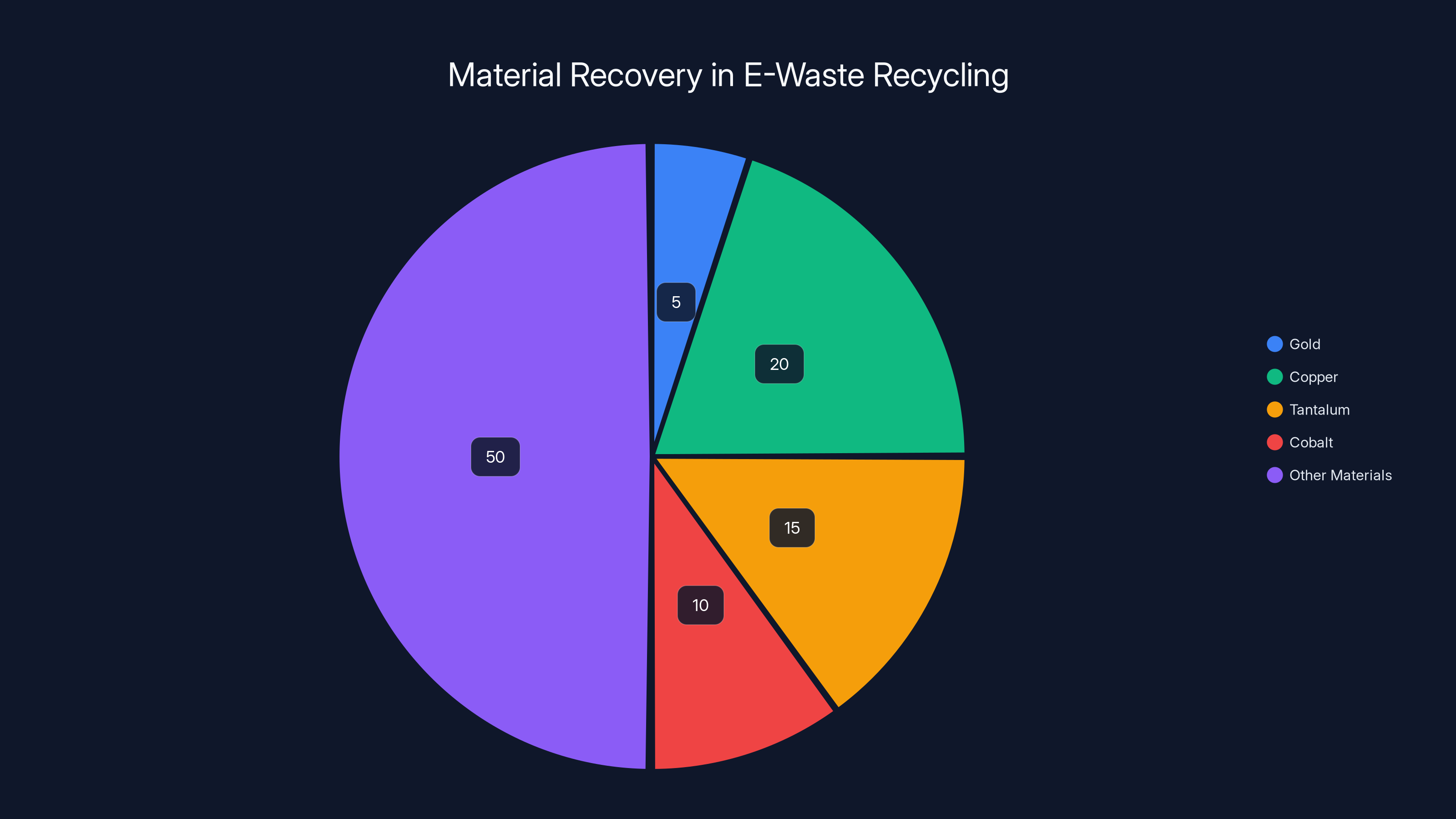

Why is this such a massive emissions culprit? Because manufacturing a circuit board involves extracting, processing, and combining materials in ways that are extraordinarily energy-intensive. You need gold for bonding wires. Copper for traces. Tantalum for capacitors. Cobalt for controllers. Rare earth elements for magnets. Each material comes from mining operations that devastate landscapes, consume enormous quantities of water, and generate greenhouse gas emissions throughout the extraction and refinement process.

Take gold as an example. A single printed circuit board might contain only 0.1 grams of gold, but extracting that gold requires processing tons of ore. The mining operation involves heavy equipment, explosives, chemical processing, and transportation. A tiny amount of gold in your smartwatch is connected to a supply chain that spans continents, involves multiple processing facilities, and generates emissions at every step.

Copper tells a similar story, though it's more abundant. Manufacturing copper wire involves mining, smelting, and refining processes that are energy-intensive. For a single circuit board, the environmental cost might seem negligible. Multiplied across billions of devices, the cumulative impact becomes staggering.

Then there's the manufacturing process itself. Printed circuit boards require precise environmental controls. Clean rooms. Temperature management. Chemical processing. All of this requires energy infrastructure that, in many manufacturing regions, comes from coal or other fossil fuels. Even where renewable energy exists, the manufacturing process is inherently power-hungry.

The researchers at Cornell and University of Chicago ran detailed lifecycle assessments on wearable devices. They tracked every material input, every manufacturing step, every transportation leg, and every end-of-life scenario. The results were unambiguous: the circuit board dominates the environmental impact calculation. It's not even close.

What's particularly frustrating about this problem is that the industry has known about it for years. Electronics manufacturers have detailed knowledge of their supply chains. They understand the environmental implications. Yet the business incentive structure hasn't shifted toward solving it.

Consider what it would take to change this. A manufacturer would need to redesign devices around modular circuit boards. Develop standardized interfaces so circuit boards from one generation could be used in subsequent generations. Engineer devices so the circuit board doesn't require replacement when the battery dies or the casing cracks. These aren't impossible engineering challenges. They're intentional business decisions that haven't been made because they reduce the number of devices sold.

The Carbon Footprint Breakdown

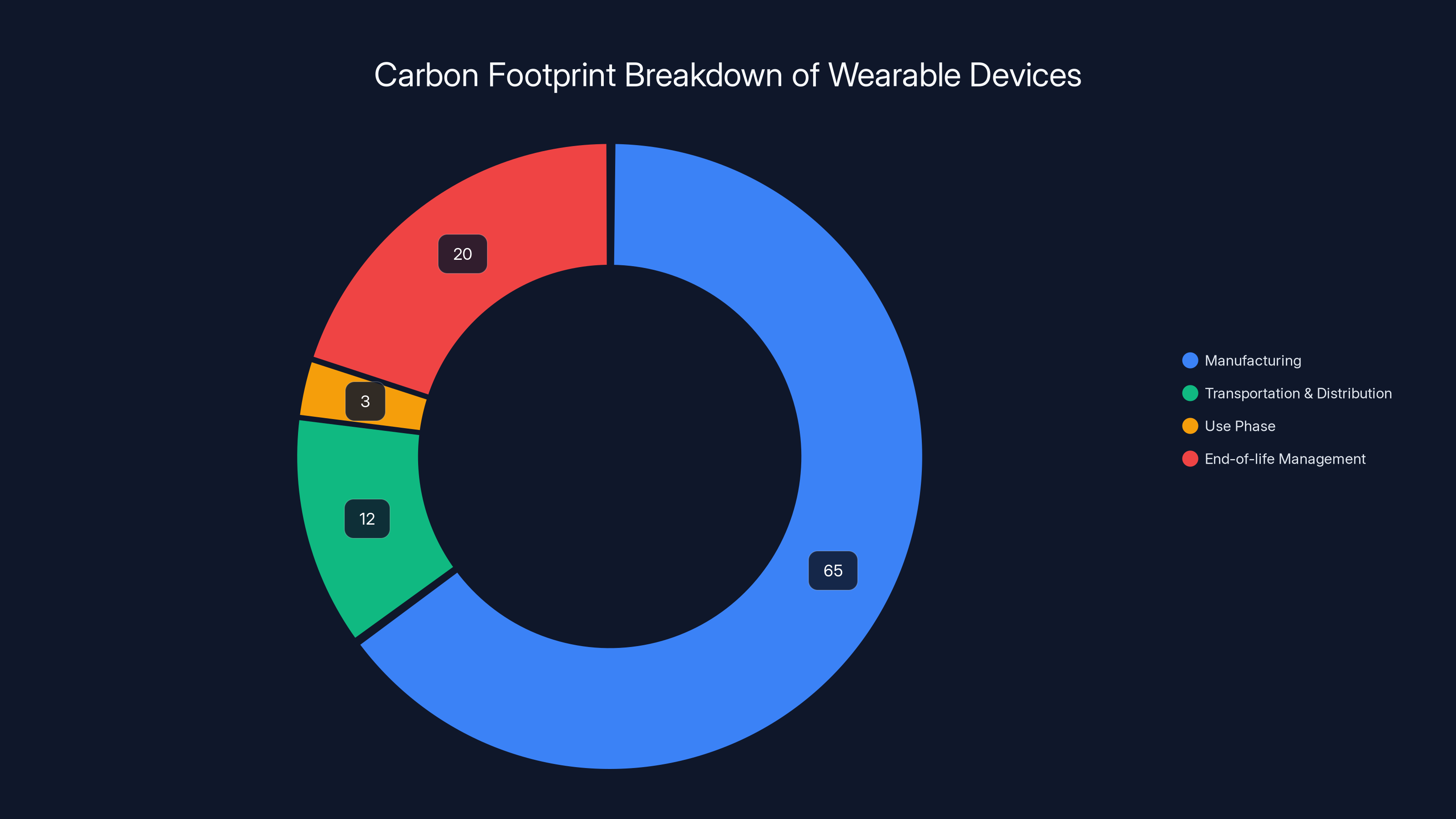

The Cornell-University of Chicago study didn't just flag the circuit board problem. It provided detailed breakdowns of where emissions come from across a wearable device's lifecycle. Understanding this breakdown is crucial because it reveals where solutions can have the biggest impact.

Manufacturing accounts for roughly 60-70% of total lifecycle emissions for a typical wearable device. This includes raw material extraction, component manufacturing, assembly, testing, and packaging. The energy intensity of this phase is enormous because it involves multiple facilities processing materials simultaneously. A single wearable might touch 15-20 different suppliers across different continents.

Transportation and distribution accounts for 10-15% of emissions. Wearables are light enough that air freight is economically viable, and manufacturers often use it to get products to market quickly. This dramatically increases transportation emissions compared to shipping heavier goods by sea. The supply chain complexity also means individual components might be shipped multiple times before final assembly.

Use phase emissions are interesting because they're actually minimal for wearables. Most devices charge via USB or wireless charging and consume milliwatts of power. Even across a 3-year lifespan, use phase emissions are negligible compared to manufacturing and transportation. This means improving efficiency during use won't meaningfully reduce overall environmental impact. The problem is upstream in manufacturing, not downstream in the customer's pocket.

End-of-life management is where scenarios diverge dramatically. If a wearable device is properly recycled, some materials can be recovered and reused, offsetting the need for new mining and manufacturing. But most wearables don't get recycled. They accumulate in drawers, get thrown in landfills, or end up in informal e-waste recycling operations in developing nations where workers are exposed to toxic materials without proper protection.

When you map out the carbon footprint across these phases, you see why the circuit board problem is so dominant. Manufacturing the circuit board drives the manufacturing phase emissions. The minerals in the circuit board require energy-intensive extraction. The processing requires energy-intensive refinement. The assembly requires precision machinery and environmental controls. And this happens before the device even leaves the factory.

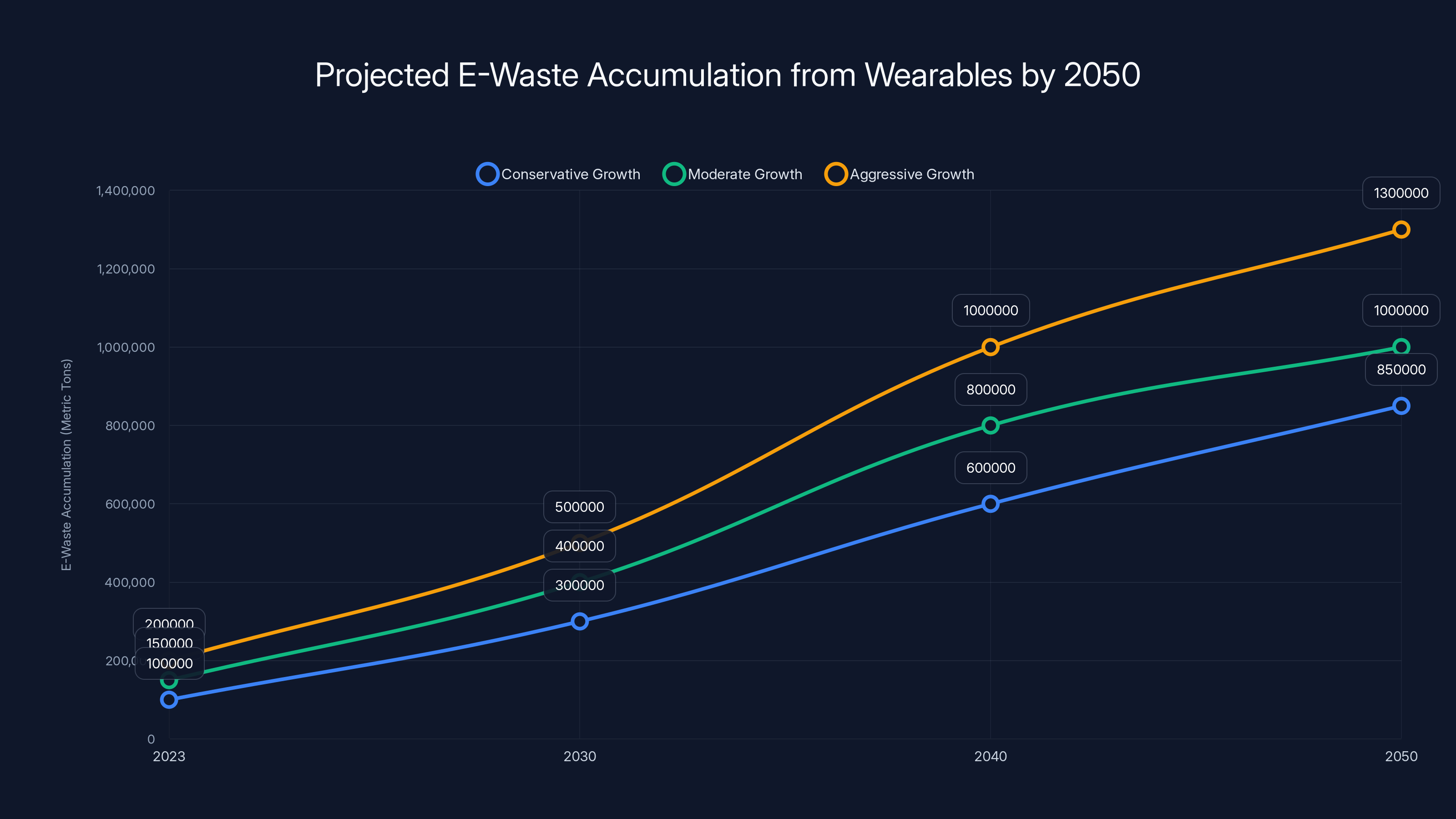

Projected e-waste from wearable devices could reach up to 1.3 million metric tons by 2050 under aggressive growth scenarios, highlighting the significant environmental impact of this product category. Estimated data.

Rare Earth Elements and Mining's True Cost

When we talk about the circuit board's environmental impact, we're really talking about mining. And mining isn't abstract. It has real consequences that extend far beyond carbon emissions.

Rare earth elements are a fundamental component of modern electronics. Your wearable's magnetometer probably contains rare earth elements. The processor might have rare earth-derived components. These materials have unique electrical and magnetic properties that make them irreplaceable in current technology. But extracting them is brutal.

Take tantalum mining. Tantalum is used in capacitors throughout electronic devices. Tantalum mining in Central Africa has been directly connected to armed conflict, water pollution, and ecological devastation. Miners work in dangerous conditions for minimal pay, extracting ore by hand in areas with virtually no environmental regulation. The ore is processed in ways that contaminate waterways used by millions of people downstream.

Cobalt mining presents a similar ethical and environmental nightmare. Most cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where mining operations have created ecological damage, labor exploitation, and health hazards. Children work in mines. Communities lose access to clean water. Entire ecosystems are disrupted.

From a carbon perspective, these mining operations consume diesel fuel for equipment, require chemical processing, and generate emissions throughout the refinement process. But the full cost extends beyond carbon. It encompasses water depletion, soil contamination, habitat destruction, and human rights violations.

For wearable devices, manufacturers argue they're using such small quantities of these materials that the impact per device is minimal. Which is technically true, but mathematically misleading. When you multiply by billions of devices, and when you account for the supply chain complexity, the cumulative impact becomes unconscionable.

The industry response has been incremental. Some manufacturers have committed to sourcing minerals from conflict-free mines. Others have established responsible sourcing programs. But these efforts don't solve the fundamental problem: mining itself is destructive, and wearables require mining.

Projected E-Waste Accumulation by 2050

Let's ground the projections in specific numbers so the scale becomes real. The Cornell-University of Chicago study modeled three scenarios: conservative growth, moderate growth, and aggressive growth.

In the conservative scenario, annual wearable device production reaches 1.2 billion units by 2050. This assumes slower adoption in developing markets and some market saturation in developed regions. Even in this conservative case, cumulative e-waste from wearables between now and 2050 would reach 850,000 metric tons. That's roughly equivalent to 170 million cars' worth of electronics waste.

The moderate growth scenario projects 1.5 billion units annually by 2050, generating over 1 million metric tons of e-waste through 2050. The aggressive scenario, which assumes rapid adoption globally and minimal market saturation, projects 2 billion units annually, generating 1.3 million metric tons of e-waste.

To contextualize this, global electronic waste is currently estimated at 50-60 million metric tons annually. Wearable devices alone could represent 2-3% of total e-waste globally by 2050. For a single product category, this is enormous.

But the carbon numbers are even more striking. The moderate growth scenario projects 100 million metric tons of CO2 emissions from wearable devices through 2050. That's equivalent to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of 30-40 coal-fired power plants. This is for devices that are supposed to improve human health. The irony is almost unbearable.

These projections assume current design patterns continue. Sealed devices. Non-replaceable components. Manufacturing processes optimized for cost, not longevity. If the industry implements the suggested changes—modular design, alternative materials, reusable components—the projections could shift dramatically. But there's no guarantee this will happen without policy pressure or market demand shifts.

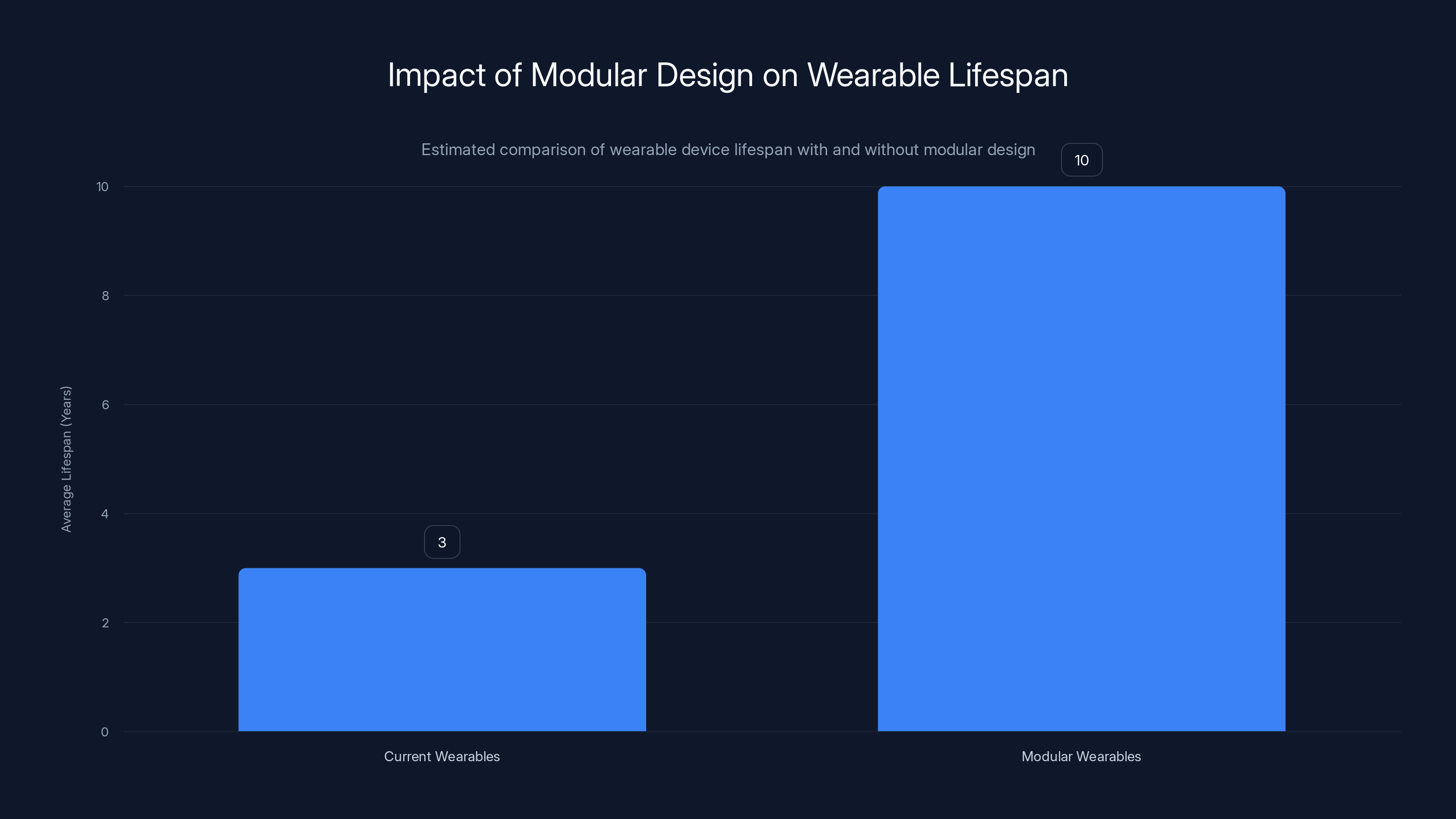

Modular design could extend the average lifespan of wearables from 3 to 10 years, significantly reducing electronic waste and carbon footprint. Estimated data.

The Modular Design Solution

Here's what actually excites researchers about solving this problem: the solution exists. It's not speculative technology or distant innovation. It's engineering that's already proven in other industries.

Modular design means devices are engineered so components can be replaced independently. Your wearable's battery dies after three years? You replace just the battery, not the entire device. The sensor housing cracks? You replace the housing. The circuit board becomes outdated? But here's the revolutionary part: you keep using the same circuit board across multiple device generations, upgrading the outer components while keeping the computational core intact.

This approach is standard in industries like automotive and consumer tech. Your laptop's battery can be replaced. Your desktop's components can be upgraded. Your car's engine components are designed for replacement. But wearables? Most manufacturers seal everything together with adhesives, use proprietary connectors, and make replacement deliberately difficult or impossible.

Why? Because planned obsolescence is profitable. If you can't replace the battery, you buy a new device. If the housing can't be separated from the electronics, you can't upgrade just the sensors. This lock-in is intentional product design strategy.

Modular wearables would flip this dynamic. Imagine buying a smartwatch where the circuit board—the expensive, carbon-intensive component—stays with you for five, ten, or even fifteen years. You upgrade the wristband when it wears out. You replace the sensor module when new sensing technology emerges. You swap the outer casing for durability or aesthetic reasons. But the core computational unit, the part that has 70% of the carbon footprint, becomes a durable asset you maintain across years.

The environmental math is startling. If the average wearable is replaced every three years, and modular design extended that to ten years while allowing component upgrades, you'd reduce manufacturing emissions by roughly 70% for that device. Across billions of devices, this compounds into hundreds of millions of metric tons of CO2 reductions.

The industry isn't moving toward modular design because it requires rethinking manufacturing, logistics, and business models. Companies would need to invest in designing standardized interfaces. They'd need to ensure backward compatibility across device generations. They'd need to maintain inventory of replacement components. All of this costs money upfront and reduces the number of devices sold. The economics don't work unless customers are willing to pay a premium for sustainability, or unless regulations force the change.

Some startups are experimenting with modular approaches. A few manufacturers are offering battery replacement services. But these are exceptions, not industry standards. The major wearables manufacturers—the companies driving growth—haven't committed to modular design at scale.

Alternative Materials: Replacing Rare Earth Elements

The second major solution pathway involves substituting rare earth elements with more abundant, less problematic materials. This is technically feasible. It's not about discovering new physics. It's about engineering trade-offs and accepting slightly different performance characteristics.

Copper instead of gold for bonding wires. Copper is abundant, recyclable, and already widely used in electronics. It doesn't have gold's exact properties—it oxidizes more easily, requires different processing—but the performance difference is manageable. Using copper would require engineering adjustments but would dramatically reduce mining impact.

Common metals instead of rare earth elements in magnets. We already have technologies using ferrite magnets and aluminum-nickel-cobalt alloys. These lack some of the exceptional magnetic properties of rare earth magnets, but for most wearable applications, they're sufficient. A fitness tracker doesn't need the highest-performance magnetometer available. It needs an acceptable one.

Aluminum and titanium for structural components instead of complex alloys. These materials are abundant, recyclable, and have established supply chains with better environmental practices than rare earth mining.

The engineering challenge here is accepting trade-offs. Devices might be slightly larger, slightly heavier, or slightly less capable. But for health monitoring wearables, these trade-offs are acceptable. A glucose monitor that's 2 millimeters thicker but doesn't require tantalum mining is an easy choice.

The barrier isn't technical. It's that manufacturers have optimized for miniaturization and performance. Rare earth elements enable smaller, lighter devices with exceptional performance. Accepting materials with slightly different properties means accepting slightly different form factors.

What's encouraging is that some progress is happening. Several manufacturers have committed to reducing or eliminating certain problematic materials. Apple, for instance, has made commitments to removing conflict minerals from their supply chain. But commitments and actual implementation are different. And for a company selling hundreds of millions of devices annually, "reducing" isn't the same as eliminating.

Manufacturing dominates the carbon footprint of wearables, accounting for 65% of emissions, highlighting the need for sustainable practices in production. Estimated data.

Recycling's Limitations and Opportunities

When people hear about e-waste problems, they often think the solution is better recycling. If we could just recycle all those devices, we'd recover the valuable materials and reduce mining demands, right?

Recycling helps, but it's not a silver bullet. Here's why: recycling is energy-intensive, has significant losses in the recovery process, and the value of recovered materials often doesn't justify the cost of extraction, especially for wearables with tiny quantities of valuable materials.

A printed circuit board from a wearable contains maybe 0.1% gold by weight, along with copper, tantalum, cobalt, and other elements. Extracting that gold requires separating it from base metals and other materials. The process uses chemicals, generates hazardous waste, and consumes energy. For a small circuit board with minimal precious metal content, the economics don't work unless you're processing millions of devices simultaneously.

Most wearable e-waste never enters formal recycling streams. Devices end up in landfills, burned in uncontrolled incineration, or processed in informal e-waste recycling operations in developing nations. In these informal operations, workers—often children—use primitive methods to extract valuable materials, exposing themselves to toxic substances. The environmental damage from improper recycling often exceeds the damage from disposal.

The second issue is that recycling assumes devices are designed to be recycled. Most wearables aren't. They're sealed with adhesives that make disassembly difficult. Components are soldered together in ways that require specialized equipment to separate. Batteries are glued in place. The design complexity actually makes recycling harder and more costly.

However, recycling still matters and does recover some value. When done properly, recycling can recover 60-80% of materials by weight. For larger electronics like smartphones or computers, this economic trade-off makes sense. For wearables with their tiny material quantities, the math is shakier.

The real opportunity in recycling isn't in recovering materials from millions of disposed devices. It's in designing devices that can be disassembled easily, with clearly labeled materials that facilitate value recovery. It's in designing components so they can be recovered as intact units rather than requiring separation into elemental materials.

This loops back to modular design. A device where the circuit board is bolted in place rather than glued, where batteries are replaceable rather than soldered, where sensors are modular rather than integrated, is far easier to recycle. Modular devices enable component reuse, which is more valuable than material recovery.

Policy and Regulatory Pressure

The situation where an industry continues environmentally destructive practices because it's profitable needs regulatory intervention. And it's starting to happen, though unevenly across regions.

The European Union has been pushing electronic device manufacturers toward repairability requirements and extended producer responsibility. The Right to Repair movement has gained political momentum, particularly in the EU and parts of North America. These policies don't specifically target wearables yet, but they create frameworks that could be extended.

Some regulatory approaches being considered or implemented:

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Manufacturers are financially responsible for end-of-life management of their products. This creates economic incentive to design devices that are easier to recycle or refurbish.

Repairability Requirements: Manufacturers must provide spare parts and repair manuals for a minimum period after purchase. This encourages modular design because sealed devices are harder to repair.

Material Disclosure: Companies must disclose the materials used in their devices, including conflict minerals and rare earth elements. This creates transparency and public pressure.

Planned Obsolescence Bans: Some regulatory bodies are exploring laws that would make deliberately designing products for short lifespans illegal.

Circular Economy Standards: Requirements that products be designed for disassembly, component reuse, and material recovery.

These policies face resistance from manufacturers who argue they'll increase costs and slow innovation. But the business models these policies challenge are actually optimized for cost, not innovation. Innovation could flourish in a framework that rewarded durability and modularity instead of penalizing it.

The global picture is fragmented. The EU moves ahead with aggressive requirements. The US takes a lighter regulatory touch, hoping market forces will drive change. Developing nations have minimal capacity to enforce environmental standards. This fragmentation means manufacturers can shift production to the least-regulated markets, avoiding real change.

Estimated data shows that while recycling can recover a significant portion of materials, the recovery rates for precious metals like gold are relatively low compared to other materials.

Market Incentives and Consumer Demand

Regulation is one lever. Consumer demand is another. If sufficient people are willing to pay a premium for sustainable wearables, market forces could drive change independently.

This is happening at the margins. Companies marketing durability, repairability, and environmental responsibility are finding customers. But these represent a small percentage of the market. Most consumers optimize for price, features, and brand recognition. Environmental impact is abstract and distant. A device that costs 30% more because it's modular doesn't appeal to most buyers.

Changing this requires normalization of lifecycle thinking. Instead of asking "What does this device cost today?" people need to ask "What is the true cost of ownership, including environmental impact, across the device's lifespan?" This perspective shift is happening in some markets but hasn't reached mainstream adoption.

Companies could accelerate this shift through business model innovation. Subscription models where you pay monthly for device updates and components could align financial incentives with durability. Device-as-a-service approaches where the manufacturer retains ownership and is responsible for end-of-life management create accountability. Leasing models where devices are returned and refurbished encourage longevity.

These alternative business models exist but aren't standard in wearables. They're more common in enterprise software and industrial equipment. Extending them to consumer health wearables is plausible but would require rethinking how products are marketed and distributed.

What makes this complicated is that consumer demand alone might not be enough. Environmental improvements that require higher upfront costs face chicken-and-egg problems. You need enough customers demanding sustainable products to justify manufacturers investing in sustainable design. But manufacturers won't invest in sustainable design until they see sufficient demand.

Breaking this cycle likely requires simultaneous pressure: regulatory requirements that force investment in sustainable design, sufficient consumer willingness to pay for sustainable products to justify the investment, and corporate leadership that prioritizes long-term environmental responsibility over quarterly earnings.

Innovation in Biodegradable Electronics

One emerging solution path involves rethinking what wearable devices are made from entirely. What if wearables could be designed from biodegradable materials that break down safely in the environment rather than persisting for centuries?

Research into biodegradable electronics is active across multiple universities and companies. The concept involves using materials like silk, cellulose, and other biological polymers for device substrates, combined with conducting inks made from materials like graphene, silver nanowires, or conducting polymers.

These biodegradable electronics can't yet match the performance of traditional silicon-based electronics. The transition speeds are slower, the processing power is limited, and durability is lower. But for simple sensors—particularly health monitoring sensors in wearables—biodegradable electronics are approaching viability.

A glucose monitor made from biodegradable materials could be worn, used, and then safely disposed of without environmental concern. The device would decompose through natural biological processes rather than persisting in e-waste streams. This addresses the e-waste problem at the source by eliminating waste altogether.

The challenge is that wearable health devices increasingly require sophisticated computing and wireless connectivity. A device that's nothing but a simple sensor can be biodegradable. A device with a Bluetooth processor, a high-capacity battery, and multiple sensors is much harder to make biodegradable with current technology.

Still, progress is being made. Some research has demonstrated biodegradable batteries, biodegradable sensors, and even primitive processors made from organic materials. Within 5-10 years, we might see wearables that degrade safely at end-of-life becoming commercially viable.

The advantage of biodegradable electronics is that they sidestep the entire e-waste problem. If devices naturally decompose into harmless components, recycling infrastructure becomes less critical. Manufacturing processes can be less constrained by the need for recyclability. The environmental calculus changes fundamentally.

However, biodegradable electronics aren't a complete solution. Manufacturing them still requires energy and materials. If they're designed with the same throwaway mentality—expect them to biodegrade so you don't need to care about longevity—they could actually increase total environmental impact through accelerated replacement cycles.

The ideal scenario combines approaches: devices that are modular and durable when they're being actively used, constructed from biodegradable materials where possible, and designed to degrade safely at end-of-life when replacement is necessary.

Supply Chain Transparency and Accountability

With the scale of wearable production, supply chains involve hundreds of suppliers across dozens of countries. This complexity creates accountability gaps. When environmental damage occurs deep in a supply chain, identifying responsibility becomes nearly impossible.

Manufacturers argue they can't fully control supplier behavior. A component supplier they contract with sources materials from mines with questionable practices. The supply chain is so fragmented that visibility disappears after a few layers. This convenient opacity has enabled environmental negligence.

Transparency initiatives are trying to change this. Blockchain-based tracking systems aim to trace materials from extraction through final product. Supply chain auditing companies perform environmental and labor assessments. Industry coalitions establish standards for responsible sourcing.

But transparency alone doesn't force change. Companies can know that their supply chains involve problematic practices and choose to do business anyway because the alternatives are more expensive or less convenient. True accountability requires consequences. Either regulatory penalties for non-compliance or market pressure from consumers unwilling to purchase products from companies with damaging supply chains.

For wearables, the supply chain transparency challenge is particularly acute because individual devices contain materials from dozens of suppliers. Tracing the origin of a specific grain of tantalum in a smartwatch is virtually impossible with current systems.

Improving this would require significant investment in supply chain infrastructure. Companies would need to demand full traceability from their suppliers, which means suppliers would need to demand it from their suppliers, and so on. This cascading requirement would increase costs throughout the supply chain and force changes in mining and processing practices.

It's possible. Some industries—particularly jewelry and precious metals—have implemented traceability systems. But wearables involve more complex supply chains with smaller individual transaction values, making implementation harder.

The Role of AI and Machine Learning in Efficiency

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being leveraged to improve manufacturing efficiency, potentially reducing the environmental impact of device production. AI optimizes manufacturing processes, predicts equipment failures before they happen, and designs components with minimal material waste.

Machine learning algorithms analyze manufacturing data to identify inefficiencies. By fine-tuning processes, manufacturers can reduce energy consumption, minimize defect rates, and increase yields. For circuit board manufacturing specifically, AI is being used to optimize layout designs that minimize material usage while maintaining performance.

AI can also be deployed in predictive maintenance, identifying equipment problems before they cause downtime or failures that lead to scrap. By reducing manufacturing waste, AI indirectly reduces the environmental impact of wearable production.

In design phases, AI tools can simulate performance across thousands of design variations, enabling engineers to find optimal designs that balance performance with environmental impact. This computational approach can discover solutions that human engineers might miss.

However, AI itself consumes energy, and the computational infrastructure required to run these optimization systems generates emissions. The net benefit depends on whether the efficiency gains exceed the energy cost of the AI systems themselves. In most cases they do, but not dramatically. AI is a useful optimization tool, not a fundamental solution to the e-waste problem.

Where AI has more significant potential is in helping design wearables specifically for long life and durability. AI can identify design patterns associated with longevity, simulate stress testing across millions of scenarios, and predict which designs will fail prematurely. By designing devices that last longer, AI indirectly addresses the e-waste problem by reducing replacement frequency.

But again, this only matters if manufacturers are incentivized to design for longevity. If business models reward planned obsolescence, AI efficiency improvements just enable faster replacement cycles, ultimately increasing environmental impact.

Case Studies: Companies Making Progress

While the industry as a whole hasn't solved these problems, some companies are moving in the right direction. Looking at actual implementation provides perspective on what's possible.

Some manufacturers have committed to using recycled materials in device casings. Instead of virgin plastic, they use plastic recovered from e-waste streams or ocean plastic. This doesn't solve the circuit board problem, but it demonstrates the feasibility of incorporating sustainability into production.

Other companies have extended warranty periods and established repair programs, making components replaceable rather than forcing complete device replacement. While these aren't modular designs in the fullest sense, they extend device lifespan and reduce replacement frequency.

A few startups focused specifically on sustainable wearables are experimenting with modular designs and biodegradable materials. These companies are proving that sustainable alternatives are technologically feasible, though they typically serve niche markets and haven't achieved significant scale.

The limiting factor across all these initiatives is that they increase costs or reduce profitability. Without regulatory pressure or sufficient market demand for sustainable products, scaling these approaches remains difficult.

Future Directions: What Needs to Change

Solving the e-waste problem in wearables requires parallel changes across multiple dimensions. No single solution is sufficient.

Design Philosophy: The industry needs to shift from designing for replacement to designing for longevity and modularity. This requires accepting that smaller profit margins on initial sales are compensated by revenue from component replacements and repairs.

Manufacturing Innovation: Circuit board manufacturing must shift toward materials that don't require rare earth mining. This is technically feasible but requires upfront investment and acceptance of slightly different performance characteristics.

Business Models: Manufacturers need to explore models that align profitability with environmental responsibility. Leasing, subscription, and device-as-a-service approaches can align incentives differently than traditional sales models.

Supply Chain Accountability: Full traceability from mining through final product is necessary. This requires investment in supply chain infrastructure and willingness to move away from suppliers with problematic practices, even if it increases costs.

Policy Framework: Regulations establishing extended producer responsibility, repairability requirements, and material transparency create the structural incentives that drive change. Market forces alone haven't proven sufficient.

Consumer Awareness: For policy change to be politically viable, consumers need to understand the environmental cost of wearables. This requires education and cultural shift around device purchases.

Alternative Materials Research: Investment in biodegradable electronics, alternative materials for circuit boards, and non-toxic processing must continue. Public funding might be necessary because individual companies don't have incentive to research solutions that reduce their sales.

None of these are impossible. Each is being pursued to some degree already. But they all need to scale simultaneously for real impact.

The 2050 Future We're Building

Projecting forward to 2050 with current trajectories is sobering. Two billion wearable devices annually. One million metric tons of e-waste. One hundred million metric tons of CO2. These aren't abstract numbers if you think about what they mean.

One million metric tons of e-waste is ten million cars' worth of electronics. It's waste that needs to go somewhere. Landfills in developing nations will fill faster. Groundwater contamination will spread. Communities living near e-waste processing will experience health problems from exposure to toxic materials. These are real consequences affecting real people.

The CO2 emissions are the carbon equivalent of 30 million cars driven for a year. It's climate impact that translates to stronger storms, hotter temperatures, disrupted agriculture, and climate migration. For devices designed to help people live healthier lives, the irony is crushing.

But the 2050 future doesn't have to look like this. If the industry shifts toward modular design, alternative materials, and supply chain accountability over the next 5-10 years, the trajectory changes dramatically. Devices lasting twice as long cuts e-waste and emissions in half. Using common metals instead of rare earth elements cuts supply chain emissions by 40-50%. Designing for recycling and component reuse captures additional value.

The interventions are known. The technology is mostly proven. What's missing is the will to implement at scale. That will needs to come from a combination of regulation, consumer demand, and corporate leadership willing to prioritize long-term environmental responsibility over short-term profit maximization.

The decisions being made today at major wearables manufacturers—decisions about device design, material sourcing, component longevity—are determining what 2050 looks like. Every sealed device, every non-replaceable component, every rare earth element sourced from environmentally destructive mines contributes to the future we're building.

Conversely, every decision to design for modularity, every investment in alternative materials, every commitment to supply chain transparency is bending the trajectory toward a different future.

2050 is 25 years away. That's roughly 6-8 device replacement cycles for a typical consumer. The wearables you're wearing today, and the ones you'll buy in the next few years, directly determine the environmental impact we'll face in 2050. These aren't theoretical concerns. They're decisions with real consequences.

FAQ

What is considered a wearable health device?

Wearable health devices are electronic devices worn on the body that monitor health metrics or provide health-related functions. This includes fitness trackers that count steps and monitor heart rate, smartwatches that display health information, glucose monitors for diabetics, blood pressure monitors, sleep trackers, and electrocardiogram devices. Increasingly, this category includes augmented reality glasses with health monitoring capabilities and smart rings that track vital signs. The defining characteristic is that they're worn continuously or regularly and collect health or activity data.

How much e-waste do current wearables generate annually?

Current wearable device production generates approximately 5-7 million metric tons of e-waste annually globally. This is based on production estimates of 48 million devices per year with average weights of 100-150 grams per device. However, this represents only a fraction of total e-waste because wearable adoption is still in early stages. The projections showing over 1 million metric tons by 2050 assume adoption growth to 2 billion devices annually, representing roughly 40-50x increase in e-waste generation from this category alone. For context, global e-waste currently totals 50-60 million metric tons annually across all electronics, so wearables currently represent roughly 10% of that total and could grow to 2-3% of a larger total pool by 2050.

Why is the printed circuit board the biggest environmental problem?

The printed circuit board accounts for 70% of a typical wearable's carbon footprint due to the materials it contains and the manufacturing processes required. Circuit boards contain rare earth elements like gold, tantalum, cobalt, and others that require energy-intensive mining and refinement. Mining operations for these materials consume fossil fuels, require chemical processing, and damage ecosystems. The manufacturing process for circuit boards themselves requires clean room facilities, precise temperature controls, and specialized equipment, all energy-intensive. When you multiply these impacts across billions of devices, the cumulative effect is staggering. The plastic casing, battery, and other components contribute to environmental impact, but the circuit board dominates because of both material scarcity and manufacturing intensity.

What is modular design in wearables, and why does it matter?

Modular design means wearable devices are engineered so components can be replaced or upgraded independently. Instead of sealed devices where everything is glued together, modular wearables have standardized interfaces allowing battery replacement, sensor upgrades, and housing changes without replacing the entire device. This matters environmentally because it extends device lifespan dramatically. If a battery degrades after three years but the circuit board remains functional for ten years, modular design allows keeping the carbon-intensive circuit board in use while only replacing the battery. This could reduce manufacturing emissions by 60-70% for that device. Multiplied across billions of devices, modular design represents the single most impactful design change possible for reducing e-waste and carbon emissions.

Can wearables be made from biodegradable materials?

Biodegradable electronics are in active research and approaching commercial viability for simple wearables. Scientists have developed biodegradable substrates using silk and cellulose, conducting inks from materials like graphene and silver nanowires, and even biodegradable batteries. These devices can fully decompose in 3-6 months in controlled environments, compared to traditional electronics persisting for hundreds of years in landfills. However, current biodegradable electronics are limited to simple applications—basic sensors, simple processors. More complex wearables with Bluetooth connectivity, high-capacity batteries, and multiple sensors are still challenging to make fully biodegradable with current technology. Within 5-10 years, simpler wearables like basic activity monitors could realistically be manufactured from fully biodegradable materials, fundamentally changing the e-waste equation.

What policies could force change in wearable manufacturing?

Several policy approaches are being proposed or implemented globally: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) makes manufacturers financially responsible for end-of-life device management, creating economic incentive for designed longevity and recycleability. Right to Repair laws require manufacturers provide spare parts and repair documentation, encouraging modular design. Material Disclosure requirements mandate companies reveal which rare earth elements and conflict minerals are in their devices, creating transparency and public pressure. Planned Obsolescence Bans would make it illegal to deliberately design products with limited lifespans. Circular Economy Standards require products be designed for disassembly and material recovery. The European Union is pursuing several of these approaches, while the United States takes a lighter regulatory touch. The fragmented global policy landscape means manufacturers can optimize around the least regulated markets rather than implementing industry-wide changes.

How does wearable manufacturing compare to other electronics in environmental impact?

Wearables have particularly high environmental impact per unit because circuit boards must be miniaturized to fit on-body form factors, requiring more sophisticated manufacturing processes and rarer materials than larger devices. A smartphone's circuit board is larger and can use slightly less exotic materials while maintaining performance. A laptop's circuit board is even larger with more flexibility in material choices. Wearables require extreme miniaturization, which drives toward rare earth elements and more intensive manufacturing. However, on a per-device basis, the total material content of wearables is lower than larger electronics. A smartwatch uses less total material than a smartphone, but the ratio of carbon-intensive component (circuit board) to total device weight is much higher. This means on an environmental-impact-per-kilogram-of-material basis, wearables can be worse than larger electronics, even though total material usage is lower.

What can consumers do to reduce wearable-related e-waste?

Consumers can make several choices: buy devices from manufacturers offering repair services and extended warranties, extending device lifespan; choose brands transparent about supply chains and material sourcing; purchase devices designed for longevity rather than following every new release; properly recycle old devices through certified e-waste recycling programs rather than throwing them away; support policies requiring manufacturer responsibility for end-of-life management; and advocate for Right to Repair legislation. Less obviously, consumers can apply lifecycle thinking—calculating total environmental cost across the device's expected lifespan rather than just looking at purchase price. A more expensive device lasting twice as long might have lower total environmental impact than a cheaper device replaced more frequently. Consumer demand does influence manufacturer investment, though research suggests policy requirements and supply chain accountability matter more than individual purchasing choices at current adoption levels.

Looking Forward: The Path Forward for Wearable Sustainability

The situation with wearable e-waste isn't hopeless, but it requires urgent action. The technology to solve this problem exists. Modular design is proven in other industries. Alternative materials are being developed. Supply chain transparency systems exist. Biodegradable electronics are approaching viability. What's needed is the political will and market incentive structure to scale these solutions.

The next 5-10 years are critical. The design decisions made now will determine whether we move toward a wearables industry that's environmentally sustainable or continue accelerating toward the million-ton e-waste future projected for 2050. These aren't distant problems affecting future generations in abstract ways. They're decisions with immediate consequences for communities living near mining operations, e-waste processing facilities, and manufacturing hubs.

For individuals, this means thinking differently about wearable purchases. Instead of asking "What can this device do?" and "How much does it cost?", ask "How long will this device last?" and "Can it be repaired?" and "Where do its materials come from?" These lifecycle questions shouldn't be radical. They should be standard consumer awareness.

For manufacturers, it means recognizing that environmental sustainability isn't a constraint on profitability—it's an emerging market opportunity. Companies designing sustainable wearables might initially face higher costs, but they're building brands around values that resonate with growing consumer segments. First-mover advantage in sustainable design could be substantial.

For policymakers, it means implementing frameworks that align manufacturer incentives with environmental responsibility. Extended producer responsibility, right to repair policies, and supply chain transparency requirements can drive innovation toward sustainability at scale.

The choices we make about wearable design, manufacturing, and disposal in 2025 will compound across billions of devices through 2050. Every decision to design for longevity instead of replacement, every choice to use sustainable materials instead of problematic ones, every commitment to supply chain transparency instead of convenient opacity bends the trajectory toward a different future.

The future isn't predetermined. It's being created by decisions being made right now in engineering labs, boardrooms, and policy chambers. That future is still within reach. But the window for changing course is closing.

Key Takeaways

- Wearable device production could reach 2 billion units annually by 2050, generating over 1 million metric tons of e-waste—42 times current volumes

- Circuit boards account for 70% of wearable carbon footprint due to rare earth element mining and energy-intensive manufacturing, not plastic casings as commonly assumed

- Modular design allowing component replacement and reusable circuit boards across multiple device generations could reduce manufacturing emissions by 60-70%

- Policy interventions like Extended Producer Responsibility, Right to Repair legislation, and supply chain transparency requirements are essential to drive industry-wide change

- Alternative materials (copper instead of gold, common metals instead of rare earth elements) and biodegradable electronics research offer viable paths to sustainable wearables within 5-10 years

Related Articles

- Smart Mirrors & Biometric Health Analysis: How Longevity Tech Works [2025]

- Withings Body Scan 2: The Ultimate Smart Scale for Longevity Tracking [2026]

- Complete Guide to New Tech Laws Coming in 2026 [2025]

- 33 Top Health & Wellness Startups from Disrupt Battlefield [2025]

- Realme GT8 Pro's Interchangeable Camera Design: The Future of Phones [2025]

- How Global Trade Power Is Shifting: The Tariff War's Hidden Weapon [2025]

![Wearable Health Devices & E-Waste Crisis by 2050 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/wearable-health-devices-e-waste-crisis-by-2050-2025/image-1-1767741231403.png)