The Million-Dollar Question: Are Elective Whole-Body Scans Worth It?

Imagine paying $2,500 for what's supposed to be peace of mind. You walk into a state-of-the-art facility, lie down in a massive machine, and emerge 30 minutes later with a report declaring that everything looks perfect. No red flags. No concerns. Just a clean bill of health.

Then, eight months later, you suffer a catastrophic stroke that changes your life forever.

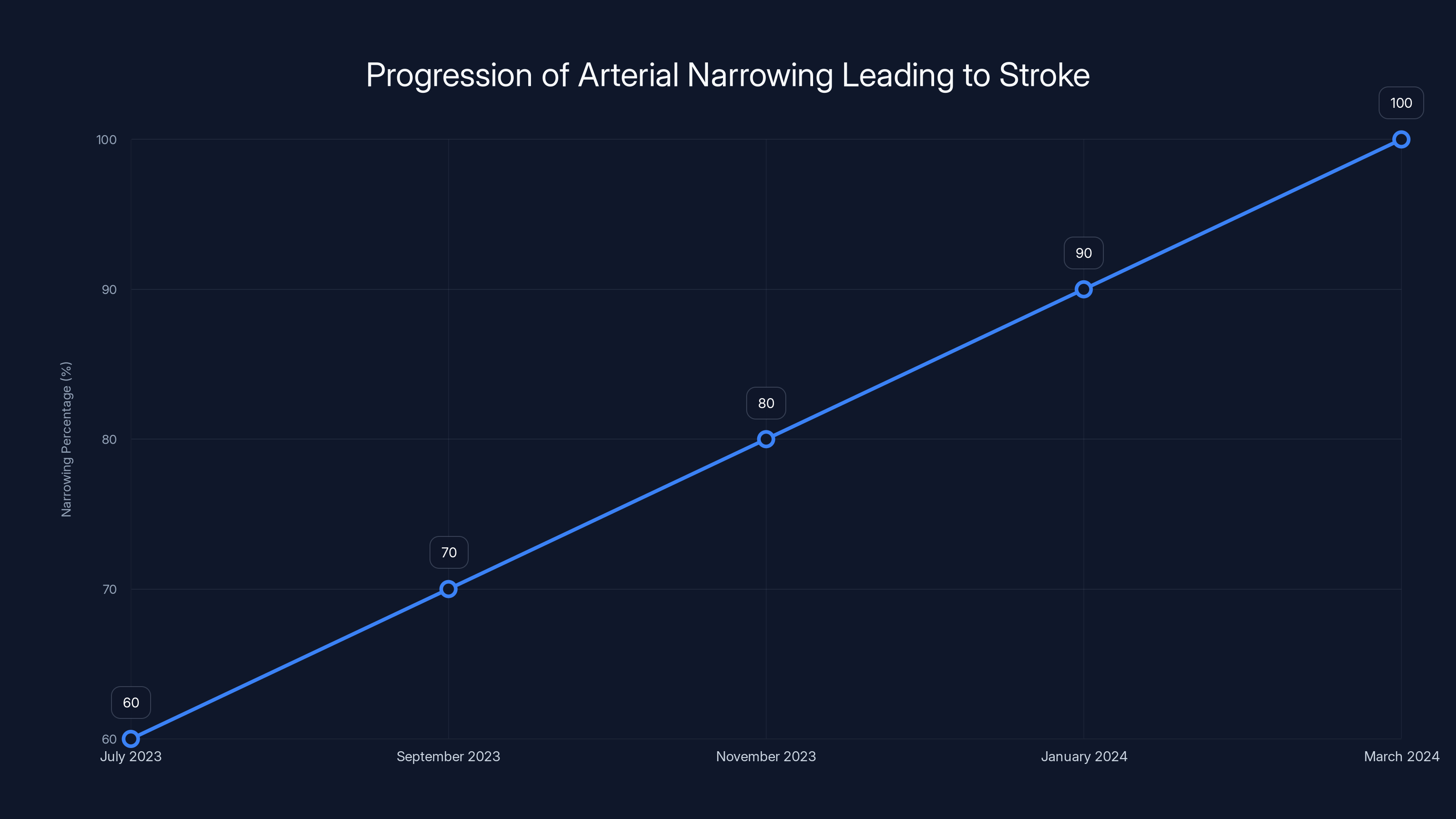

This isn't a hypothetical scenario. It happened to Sean Clifford, a New York man who underwent an elective whole-body MRI screening through Prenuvo, one of the most visible providers of these scans. According to his legal claim, the scan clearly showed a 60 percent narrowing in his right middle cerebral artery—a major vessel frequently involved in acute strokes. Yet the radiologist who reviewed his scan reported no adverse findings. Everything, the report stated, looked completely normal.

Eight months later, that same artery completely blocked. The resulting stroke left Clifford with permanent paralysis, vision loss, double vision, cognitive deficits, and speech problems. He's now suing Prenuvo, claiming the company and its radiologist missed a critical finding that, had it been detected, could have been prevented with minimally invasive intervention.

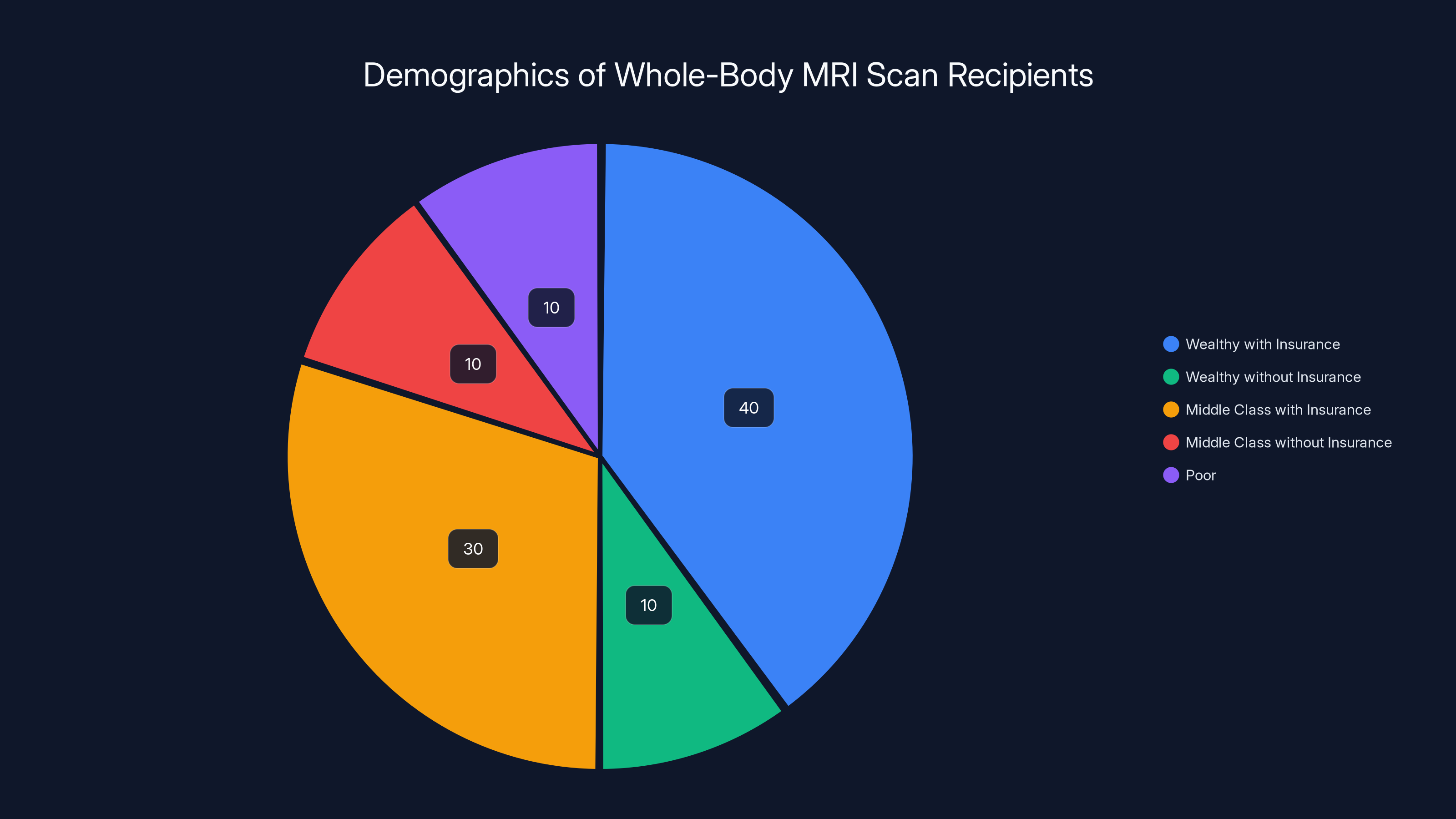

Clifford's case sits at the intersection of a fascinating and contentious debate in modern medicine. On one side, wealthy patients and health-conscious individuals see whole-body MRI screening as a way to catch problems early, before they become catastrophic. The promise is simple: spend money now to prevent emergencies later. On the other side, mainstream medical organizations, including the American College of Radiology, question whether these scans actually work, whether they're worth the cost, and whether they create more problems than they solve.

This isn't just about one man's lawsuit. It's about a larger question that affects hundreds of thousands of people considering these scans each year: In an era of unprecedented medical imaging technology, can we actually buy our way to better health?

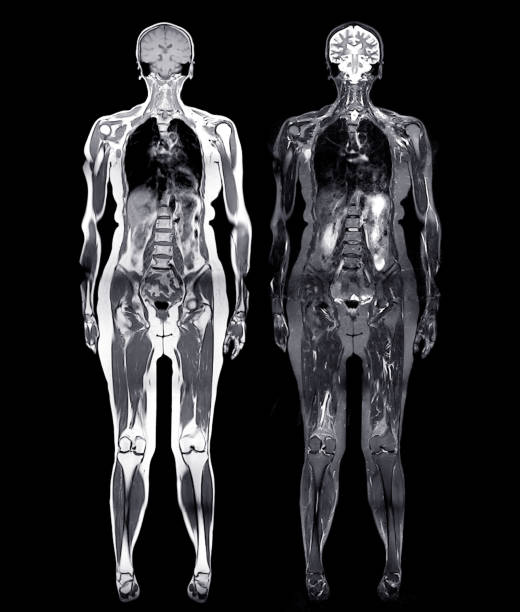

What Exactly Is Elective Whole-Body MRI Screening?

Whole-body MRI screening is fundamentally different from the MRI scans most people experience. When your doctor orders an MRI, it's usually because something's wrong. Maybe you have back pain, or your knee is swollen, or neurological symptoms that need investigation. In those cases, the radiologist knows what to look for. They can focus their expertise and attention on the specific body region and the specific problem.

Elective whole-body MRI works completely differently. The patient isn't sick. There are no symptoms. No red flags. The purpose is purely preventive—to find hidden problems before they cause symptoms. The scan typically covers the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, generating hundreds of images that a radiologist must review in detail.

Prenuvo markets these scans aggressively to the wealth-conscious and health-conscious, positioning them as "proactive care." The company has celebrity endorsements from Kim Kardashian and investor backing from supermodel Cindy Crawford and 23andMe co-founder Anne Wojcicki. The messaging is sophisticated: this isn't a test for the sick. It's a luxury health service for people who take their health seriously.

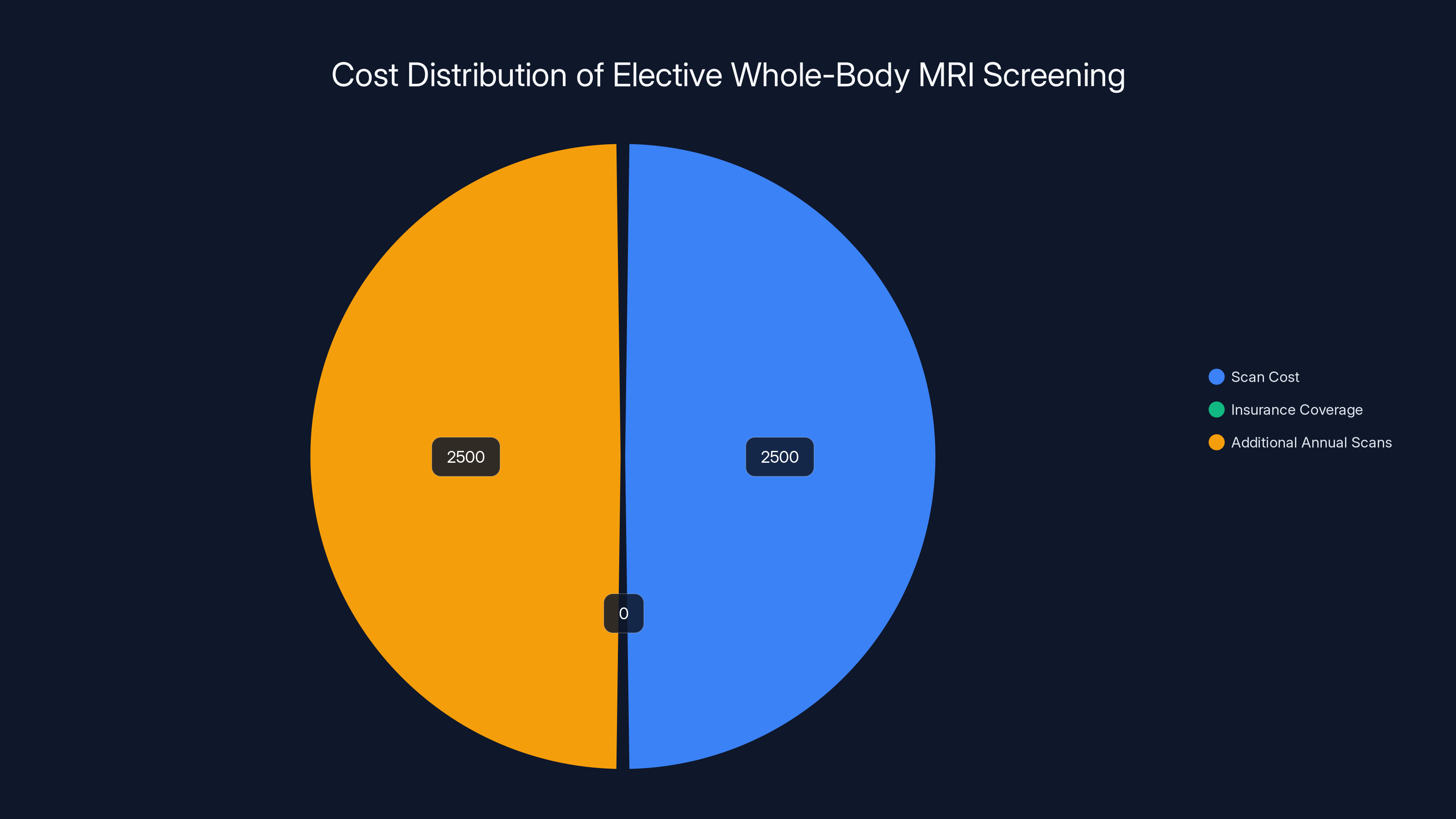

The price tag reflects that positioning. At around $2,500 per scan, these aren't cheap. That's typically out-of-pocket since insurance doesn't cover elective screening. Repeat scans, if patients choose to get them annually, multiply that cost significantly.

The appeal is obvious. Many wealthy individuals want to maximize their health. They exercise, eat well, and manage stress. Why not add medical screening to that arsenal? The question is whether the test actually delivers on its promise.

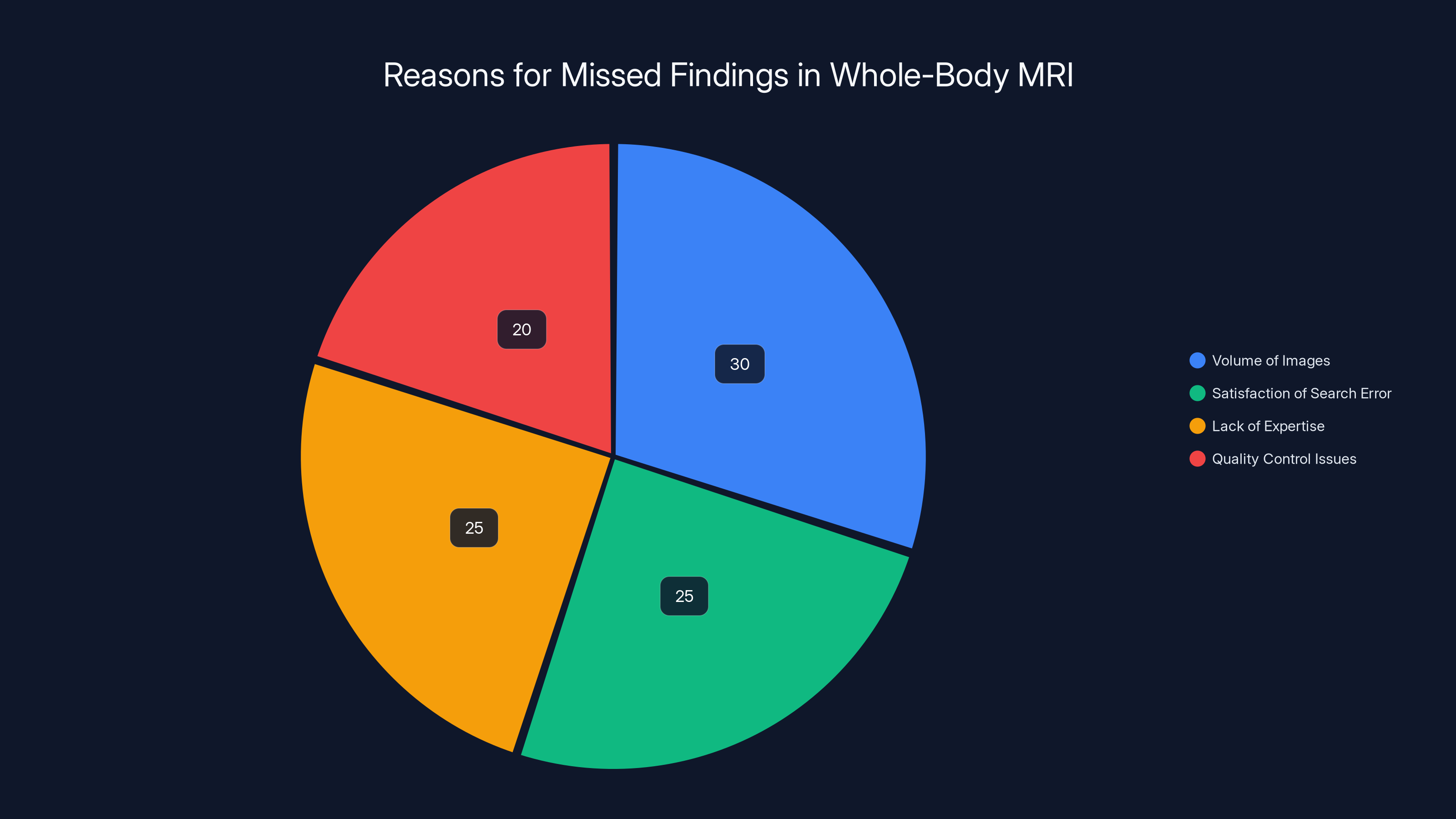

Estimated data suggests that the volume of images and satisfaction of search error are major contributors to missed findings in whole-body MRI scans.

The Case That Started It All: Sean Clifford's Stroke

Sean Clifford's story is documented in court filings and provides a detailed window into exactly how these scans can fail. On July 15, 2023, Clifford underwent a whole-body MRI at a Prenuvo facility in New York. He had no symptoms. He wasn't experiencing any neurological problems. By all accounts, he was a relatively healthy person interested in preventive care.

When radiologist William A. Weiner reviewed Clifford's scan, the imaging clearly showed something concerning in Clifford's brain vasculature. The proximal right middle cerebral artery—a critical vessel that supplies blood to the brain—showed a 60 percent narrowing. The vessel also showed irregularities in its wall structure, which can indicate disease progression.

But Weiner's report didn't flag this finding. According to court documents, Weiner reported no adverse findings. Everything looked normal. Clifford left the facility with his clean report and no reason to worry.

Eight months passed. Then on March 7, 2024, Clifford suffered a massive ischemic stroke. Follow-up imaging revealed what must have been inevitable: his right middle cerebral artery had progressed from 60 percent narrowed to completely blocked. Blood couldn't reach the brain tissue supplied by that vessel, causing the stroke.

The consequences were devastating. Clifford experienced paralysis of his left hand and leg. He developed significant general weakness on his left side. Vision loss and permanent double vision followed. He began experiencing anxiety, depression, and mood swings—common psychological consequences of stroke. He developed cognitive deficits that affected his thinking and memory. Speech problems emerged. And across all of it, his ability to perform daily activities was fundamentally altered.

In September 2024, Clifford filed suit against Prenuvo and radiologist Weiner in New York State Supreme Court. His legal claim centers on medical malpractice and negligence. The argument is straightforward: had he known about the artery narrowing, he could have pursued intervention. Options including carotid stenting or other minimally invasive procedures could have prevented the artery from completely blocking.

What makes Clifford's case even more intriguing is the background of the radiologist who reviewed his scan. In December 2024 court filings, it emerged that William A. Weiner had his medical license suspended in connection with an auto insurance scheme. According to allegations, Weiner was accused of falsifying findings on MRI scans submitted for insurance purposes. That history doesn't necessarily prove anything about his performance on Clifford's scan, but it certainly raises questions about his credibility and judgment.

Prenuvo initially tried to shield itself from liability in several ways. First, the company attempted to force the case into binding arbitration rather than public litigation. The judge rejected that. Then Prenuvo tried to apply California law to the case, presumably because California caps malpractice damages at $250,000. The judge rejected that too, ruling that New York law would apply. Prenuvo also tried to shield radiologist Weiner from being named in the suit. A December 2024 ruling denied that request as well.

In a statement to Radiology Business, Clifford's lawyer Neal Bhushan said: "This ruling reaffirms the strength and merits of our medical malpractice and negligence claims, and we look forward to continuing to litigate this matter." Prenuvo declined to comment on the litigation specifics but told The Washington Post it takes allegations seriously and is committed to addressing the matter through appropriate legal process.

The question the case raises extends far beyond Clifford's individual situation. If a whole-body MRI can miss a 60 percent arterial narrowing in the brain—a finding that's relatively clear on imaging—what other serious conditions are these scans failing to catch?

Estimated data shows a progression from 60% narrowing in July 2023 to complete blockage by March 2024, leading to Sean Clifford's stroke.

Why Do Whole-Body Scans Miss Important Findings?

Understanding why Clifford's scan missed such a significant finding requires understanding how radiology works, especially when reviewing extensive screening scans. This isn't about incompetence necessarily. It's about a fundamental problem with the screening model itself.

When a radiologist reviews a targeted MRI—say, an MRI of the brain ordered because a patient has headaches—the radiologist's attention is focused. They know what to look for. They understand the clinical context. Their eyes and expertise are concentrated on specific anatomical regions and specific pathology that might explain the patient's symptoms.

Whole-body screening scans are the opposite. They generate hundreds, sometimes over a thousand images. The radiologist reviewing these scans must mentally scan through all that data looking for anything abnormal. The challenge isn't just volume—it's that they're searching for anything wrong without knowing what might be wrong. They're casting an extremely wide diagnostic net.

This creates what radiologists call "satisfaction of search" error or "search error." Once a radiologist finds one abnormality, they're more likely to stop searching carefully. Their brain essentially says, "Found something, case closed." If they find an incidental finding of moderate concern—maybe a small lung nodule or a cyst—they might stop their detailed review and miss something more serious elsewhere.

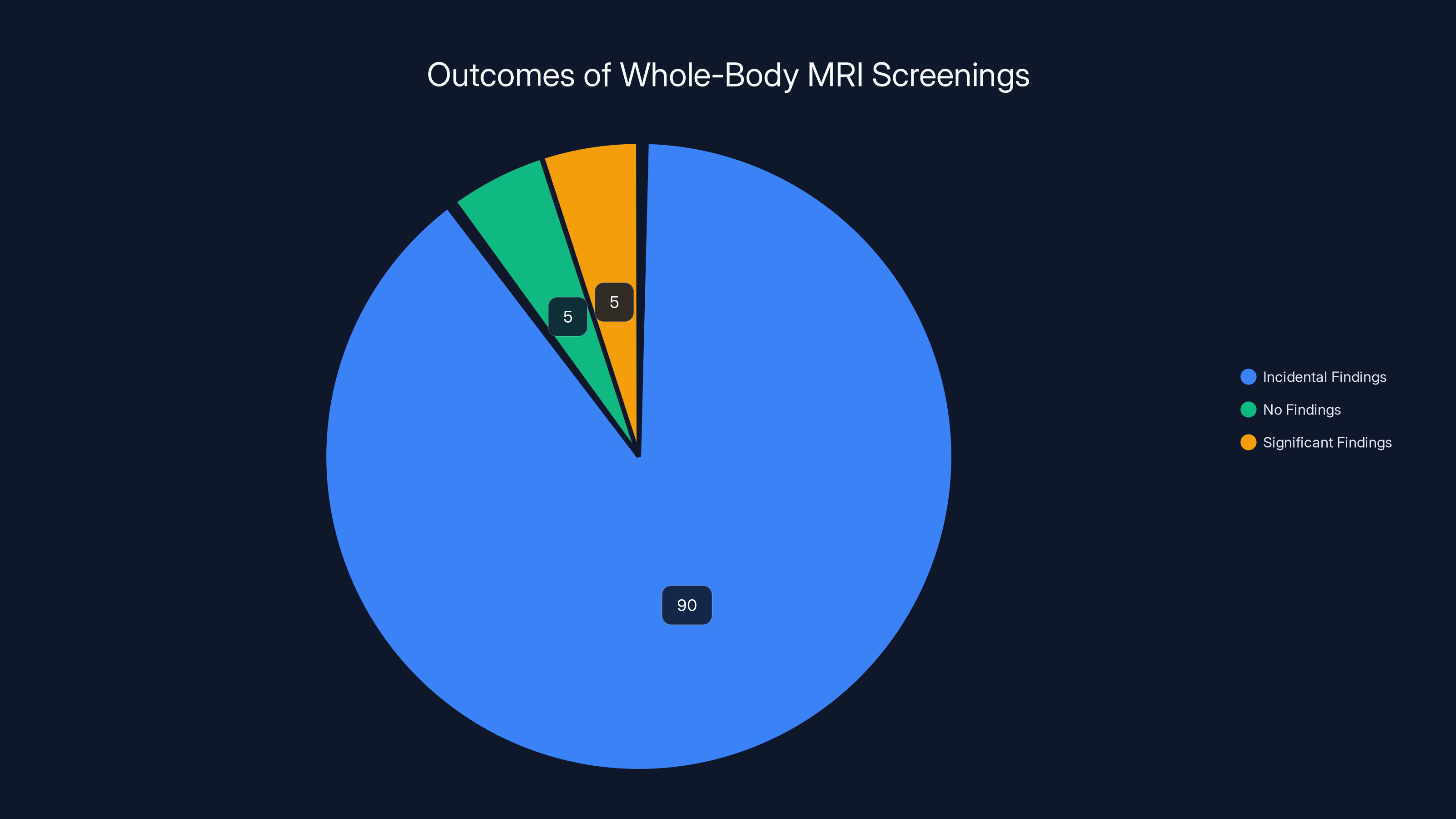

Another issue is the "incidental findings" problem. Whole-body screening scans almost always find something. A study published in radiology literature found that more than 90 percent of people undergoing whole-body screening MRI have at least one finding that requires follow-up. Most of these findings are completely benign—something like a small liver cyst that will never cause problems. But each of these findings requires decision-making: Is it important? Does it need follow-up imaging? Does it need specialist evaluation?

When radiologists are drowning in incidental findings, the truly serious ones can get lost in the noise. A 60 percent arterial narrowing is significant, but if the radiologist is also documenting two dozen other small findings, some concerning, some trivial, the serious one can slip through cracks in attention and documentation.

There's also a quality control issue. Prenuvo and similar providers are commercial enterprises. They're processing scans for wealthy patients who want fast results. There's inherent pressure to complete reports efficiently. Unlike hospitals where whole-body imaging is less common, commercial screening centers might not have the same depth of subspecialty expertise available for review.

Finally, there's the problem of interpretation standards. What counts as a "significant" finding? A 60 percent arterial narrowing is clearly significant from a vascular standpoint. It suggests disease is present and progressing. But some radiologists might reason that without acute symptoms, reporting it could cause unnecessary alarm. Others might feel that their job is only to identify findings meeting certain thresholds. Without clear protocols and without knowing the patient's specific risk factors, different radiologists might interpret the same imaging completely differently.

The American College of Radiology's Position: No Solid Evidence

The Clifford case has amplified an existing debate within medicine itself. The American College of Radiology—the largest professional organization of radiologists in the United States—has taken a clear stand against whole-body MRI screening. Their position isn't wishy-washy. It's direct: there is insufficient evidence to justify these scans.

In their formal statement, the ACR notes that to date, there is no documented evidence that total body screening is cost-efficient or effective in prolonging life. That's a significant claim. It's not saying the scans might be overused. It's saying there's no credible evidence they actually improve outcomes.

The ACR also raises the concern that such procedures lead to identification of numerous non-specific findings that don't ultimately improve patients' health but result in unnecessary follow-up testing, procedures, and significant expense. Think about that for a moment. If 90 percent of people have at least one incidental finding, that means 90 percent of people getting these scans are likely to have additional medical appointments, possibly additional imaging, potentially specialist referrals.

That cascade of care is sometimes necessary. Sometimes those incidental findings do matter. But often, they don't. A small cyst in the liver that will never cause any problem shouldn't necessitate follow-up imaging six months later just to document that it hasn't changed. Yet in current medical practice, that's exactly what often happens. The scan finds the finding, and now the system is obligated to track it.

The ACR's position aligns with broader evidence-based medicine principles. In the past 20 years, medicine has moved toward eliminating screening that doesn't have clear evidence supporting it. Routine screening mammography in younger women, for example, has been scaled back based on evidence that benefits don't outweigh harms. PSA screening for prostate cancer has been questioned based on high false-positive rates and overtreatment. The same evidence-based scrutiny should apply to whole-body MRI screening.

There's a tension here worth acknowledging. Some doctors and patients feel that more information is always better. If we can find something, shouldn't we? The problem is that medicine isn't just about information. It's about improving outcomes. If finding something leads to unnecessary interventions that harm people, then finding it wasn't actually helpful.

Estimated data shows that the majority of whole-body MRI scans are accessed by wealthy individuals with insurance, highlighting health equity issues.

Who Actually Gets These Scans? And Why?

The marketing of whole-body MRI screening is sophisticated precisely because it appeals to a specific demographic. These scans aren't for poor people or uninsured people. They're for the wealthy. People with good insurance are more likely to have good preventive care through their existing healthcare system. People without good insurance often can't afford $2,500 out-of-pocket.

This creates exactly the health equity problem that critics cite. Whole-body MRI screening widens the health disparities in America. Rich people concerned about their health get extensive, high-tech scanning. Poor people don't. Does that lead to better outcomes for the wealthy? The evidence says no. But it does lead to more medical appointments, more anxiety about incidental findings, and often more unnecessary procedures.

The typical person getting these scans is someone in their 40s, 50s, or 60s with disposable income and above-average health consciousness. They're not typically people with specific risk factors or concerning symptoms. They're the "worried well," as the medical literature calls them. They feel fine, but they're concerned that they might have hidden disease.

There's something almost psychological about the appeal. It's a way of saying, "I'm serious about my health. I'm willing to spend money on prevention." The MRI becomes a status symbol of health vigilance. And when the report comes back clean, there's a sense of reassurance. That reassurance, even if it's not medically justified, is itself valuable to some people.

But that value is ephemeral. As Clifford's story demonstrates, a clean report provides no actual safety. It's retrospective reassurance about the moment the scan was taken. It provides no information about what happens in the future. A scan that looks fine in July can show a catastrophic stroke in March. The biological time between those events, the scan provides no protection.

The Business Model of Preventive Screening: Finding "Worried Well"

One of the most insightful comments in the medical subreddit discussion of Clifford's case came from a medical professional who understood the business model explicitly: "I think their business model has been predicated on getting two types of people: worried well or very sick, and are not appropriately set up to handle patients with real but subtle findings their MRI and radiologists aren't well suited to detect."

That comment cuts right to the heart of the problem. The business model of companies like Prenuvo relies on a specific customer base. The worried well are ideal because they have money, they're healthy enough to schedule appointments, and they're seeking reassurance. The very sick are ideal because they're desperate and will pay for anything offering hope. What the business model struggles with is the in-between group: people with real but subtle disease that requires nuanced interpretation and specialist follow-up.

Sharp observers might note that this creates perverse incentives. The business wants to find things that are dramatic enough to justify the cost of the scan but not so concerning that they create liability. A 60 percent arterial narrowing is exactly the kind of finding that's uncomfortable to report because it creates obligations. It might require referral to neurology or vascular surgery. It might lead to invasive procedures. It's ambiguous enough that reasonable radiologists might disagree on its significance.

Is it in anyone's business interest to flag that finding aggressively? The radiologist might worry about creating unnecessary alarm. The company might worry about liability from interventions recommended based on the finding. The patient might worry about undergoing procedures for something that might never have caused problems.

This is exactly how a finding gets missed. Not from malice or gross negligence, but from the convergence of human psychology, business incentives, and the inherent ambiguity of medical findings.

Elective whole-body MRI screenings cost around $2,500 per scan, typically not covered by insurance. Annual repeat scans can double the expense. (Estimated data)

Risk Stratification: Who Actually Needs This Level of Screening?

If whole-body MRI screening isn't justified as a universal preventive tool, what about for people with specific risk factors? Some radiologists argue that for people with family history of stroke, for example, targeted vascular imaging might be justified. For people with family history of cancer, targeted chest and abdominal imaging might make sense. For people with specific genetic predispositions to vascular disease, specific screening protocols might be warranted.

The problem is determining who falls into these higher-risk categories and what imaging is truly justified for them. Risk stratification is supposed to be the basis of medical screening. You identify people at above-average risk for a particular condition, then you screen them for that condition. The screening test should detect the condition early enough that intervention prevents worse outcomes. The intervention should work reliably. And the benefits should outweigh the harms and costs.

For most whole-body MRI screening, those criteria aren't met. The population is self-selected as wealthy, not risk-stratified as at-risk. The screening is undirected—looking for anything wrong, not something specific. The interventions that might be recommended based on incidental findings are often more risky than the conditions themselves. And the costs are extraordinary.

Contrast this with mammography screening for breast cancer in women over 50. Decades of research have established that this screening works. It detects cancers early. Early detection improves outcomes. For women in certain age groups, the benefits clearly outweigh the harms and false positives. That's why major medical organizations recommend it.

For whole-body MRI screening, that evidence doesn't exist. And in the absence of evidence, the precautionary principle suggests we shouldn't do it. At least not universally to all comers with money.

For people at genuinely elevated risk, targeted screening makes sense. But that requires actual medical assessment, not just someone with money walking into a commercial facility.

The Incidental Finding Cascade: When Finding Something Creates Problems

One of the most important concepts in medicine that patients rarely understand is the incidental finding cascade. Here's how it works: a patient gets imaging for one reason, and the imaging finds something completely unrelated. That finding then launches a series of additional tests, appointments, and interventions—none of which the patient sought or might have benefited from.

Whole-body screening creates an enormous incidental finding burden. Researchers who have reviewed studies of whole-body MRI screening found that more than 90 percent of asymptomatic people have at least one finding requiring documentation and potential follow-up. Most of these are benign. But the patient doesn't know they're benign until a radiologist says so, and often, the radiologist recommends follow-up imaging to confirm they're benign.

Consider a concrete example. Suppose a whole-body MRI finds a small cyst in the pancreas—let's say 8 millimeters. The radiologist notes it in the report and recommends follow-up imaging in six months to confirm it hasn't grown. Why? Because a small cyst might theoretically be concerning for something. But the overwhelming majority of small pancreatic cysts never cause problems. They never become cancer. They never require treatment. But now the patient is anxious. They're scheduling follow-up imaging. They might consult a gastroenterologist. They're in the medical system for a problem that almost certainly will never matter.

This happens with liver cysts, kidney cysts, thyroid nodules, adrenal nodules, and more. A whole-body MRI scan that was supposed to provide reassurance instead creates a series of obligations and anxieties.

Meanwhile, genuinely serious findings like Clifford's arterial narrowing get missed or aren't flagged appropriately. The signal-to-noise ratio becomes impossible to manage.

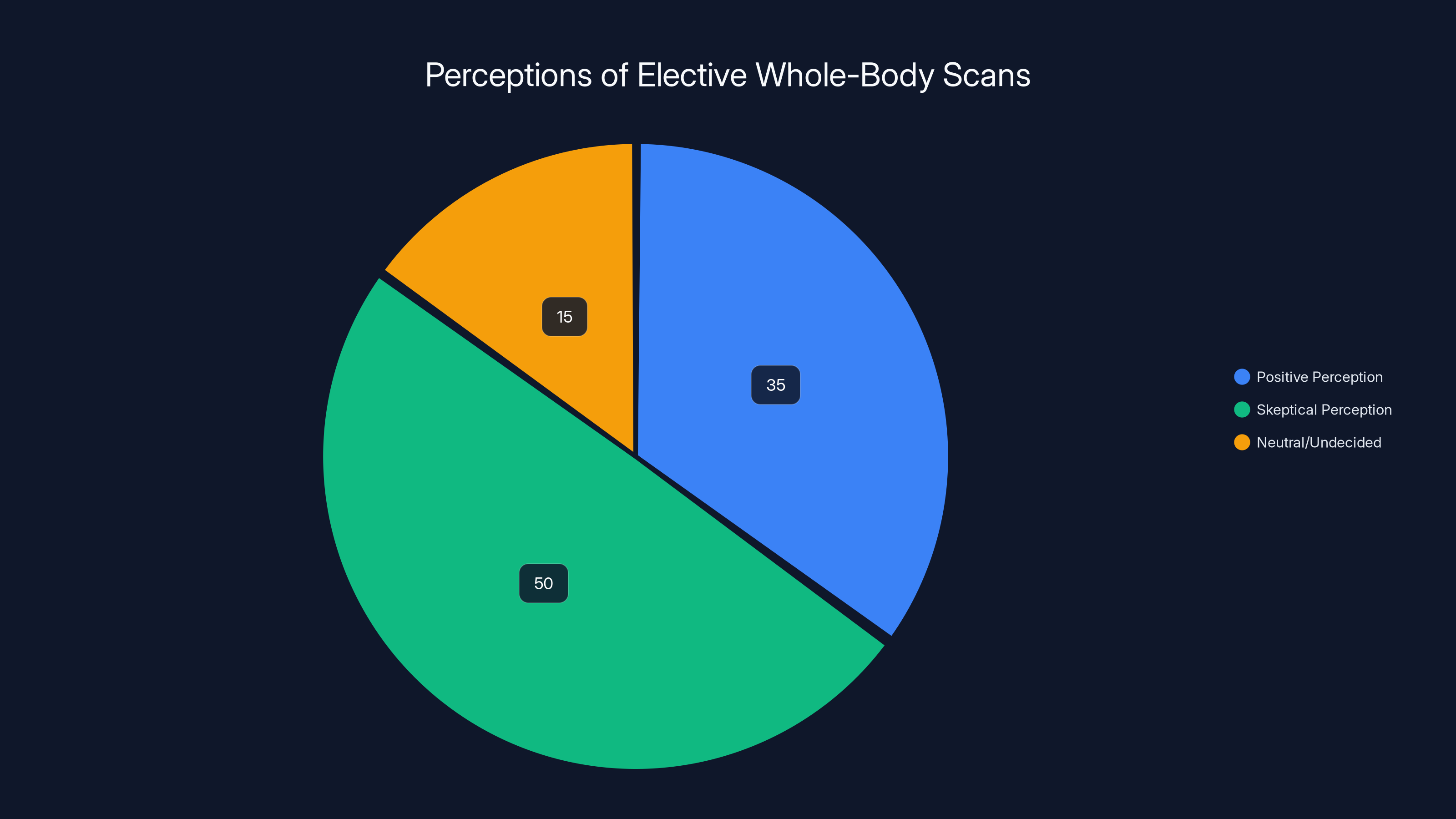

Estimated data suggests that 50% of people are skeptical about the value of elective whole-body scans, while 35% view them positively and 15% remain undecided.

Comparing Whole-Body MRI to Other Screening Modalities

How does MRI stack up against other screening approaches? This is worth examining because it contextualizes the Clifford situation within the broader landscape of medical imaging and screening.

MRI has real advantages as a diagnostic tool. It provides exquisite soft tissue detail without using ionizing radiation. For looking at the brain, the spinal cord, joints, and internal organs, MRI is often superior to CT scanning. When a patient has a specific symptom that might be neurological or musculoskeletal, MRI is often the right choice.

But for screening asymptomatic people? The advantages become less clear. CT scanning covers the lungs and abdomen very efficiently and detects more calcified disease. Ultrasound is cheaper and less time-consuming. PET scanning can detect metabolic activity suggestive of cancer. Each modality has strengths and weaknesses.

The question is whether any of these modalities, applied to asymptomatic screening, actually improves outcomes. For lung CT screening in current and former smokers, the evidence shows benefit. Heavy smokers who get annual low-dose CT screening have slightly lower lung cancer mortality. The benefit is modest—about 1 in 300 screened people over 15 years—but it's real. That's the level of evidence we should expect before recommending screening.

For whole-body MRI screening to asymptomatic people? That evidence doesn't exist. There's no randomized trial showing it improves outcomes. There's no observational study showing people who get these scans live longer or have fewer serious events. There's just marketing, celebrity endorsements, and commercial operations processing thousands of scans annually.

What The Radiologist's Perspective Reveals

Understanding radiologists' actual concerns about whole-body screening is important. These aren't uninformed cardiologists skeptical of new technology. These are imaging specialists—people whose entire career is built around looking at medical images and interpreting them.

Radiologists who criticize whole-body screening typically raise several specific concerns. First is the workflow problem. Reading a whole-body MRI thoroughly takes time. A quality radiologist might spend 30 to 45 minutes reviewing all the images, documenting findings, and writing a comprehensive report. At the volume that commercial screening centers need to operate profitably, that timeline is challenging. Something has to give—either quality or speed.

Second is the knowledge problem. Most radiologists have subspecialties. Someone specializes in chest imaging, or neuro imaging, or musculoskeletal imaging. They develop deep expertise in that area. Whole-body screening requires passing judgment on every anatomical system. Unless a radiologist is genuinely expert in each area, something gets missed or misinterpreted.

Third is the follow-up problem. When a radiologist finds something concerning on a whole-body scan, they typically recommend follow-up. The patient then has to navigate that follow-up themselves. There's no built-in system ensuring the follow-up happens, that it's done appropriately, or that results are communicated back. The scan identifies a problem, and then the system fails to manage it.

In Clifford's case, there's the additional concern that the radiologist reviewing his scan had documented history of falsifying findings on other MRI scans. That doesn't necessarily mean he falsified findings on Clifford's scan. But it raises legitimate questions about judgment and credibility.

Estimated data suggests that 90% of whole-body MRI screenings result in incidental findings, leading to potential unnecessary follow-ups. Estimated data.

The Evolution of Screening Logic: How Medicine Abandoned Universal Screening

Whole-body MRI screening represents a throwback to an older model of medicine. In the middle of the twentieth century, there was genuine enthusiasm for finding disease early. The idea that "early detection equals better outcomes" seemed self-evident. Wouldn't it be better to find cancer at stage 1 rather than stage 4?

That logic led to screening programs for all sorts of conditions. Routine chest X-rays were done on asymptomatic people. Routine EKGs were performed as general screening. Routine blood tests looked for everything possible. The idea was that more information was always better.

But evidence accumulated showing that much of this screening didn't actually improve outcomes. Routine chest X-rays didn't prevent lung cancer mortality in non-smokers. Routine EKGs found many false positives without improving survival. Routine tests found many incidental abnormalities that led to unnecessary follow-up and sometimes unnecessary treatment that harmed people.

By the late twentieth century, the evidence-based medicine movement fundamentally shifted how doctors think about screening. The new logic is: screening only makes sense if there's evidence that early detection leads to better outcomes, if the screening test is accurate, if the condition is sufficiently serious to warrant intervention, and if the benefits outweigh the harms.

Under that framework, routine screening for many conditions was eliminated. That's actually progress. We stopped doing things that don't help people and do waste resources.

Whole-body MRI screening seems to have missed that memo. It represents a return to the idea that "more information is always better" and "early detection always helps." The evidence doesn't support either premise.

Legal Implications: Setting Precedent for Radiologist Liability

Clifford's lawsuit has potential to set important precedents about radiologist liability for screening errors. If he prevails, the implications ripple across the entire industry. What standard of care applies to radiologists reviewing elective screening scans? What findings must be reported? What's the radiologist's obligation to flag potentially serious incidental findings?

Prenuvo's legal strategy reveals something interesting about how the company views these scans. The company tried to shield the radiologist from liability. It tried to force arbitration rather than public litigation. It tried to apply California law with its lower damages caps. These strategies suggest Prenuvo understands the legal vulnerability.

If Clifford wins, he might receive damages for his medical care, lost income, and pain and suffering. Depending on the verdict, it could be substantial. That would change the calculus for screening companies. Suddenly, there's financial liability for missing serious findings. That changes incentives.

Radiologists would face higher standards. If you're reviewing a screening MRI and you see something that could indicate vascular disease, you're now obligated to flag it clearly because failing to do so creates legal liability. That's actually good for patients. It creates accountability.

But it also might reduce the appetite for elective screening businesses. If liability becomes sufficiently high, if cases like Clifford's become precedent-setting victories, the business model becomes less attractive. At some point, the liability risk exceeds the commercial opportunity.

What Alternative Approaches Might Actually Work

If whole-body MRI screening doesn't work, what does? What's the alternative for people concerned about their health and interested in prevention?

The evidence supports traditional preventive medicine. For most people, the single most effective intervention is lifestyle: exercise, healthy diet, not smoking, moderate alcohol, stress management. Those factors affect overall mortality more than any screening test.

For specific, targeted screening in high-risk populations, evidence-based guidelines exist. Women over 50 should get mammography screening for breast cancer. People with family history of colorectal cancer should get colonoscopy. People who have smoked should get lung CT screening. These recommendations exist because evidence shows they work.

For people with specific risk factors—family history of early heart disease, for example—targeted testing makes sense. Stress testing, echocardiography, or carotid ultrasound might be justified. But that requires actual medical assessment of risk, not just someone with money buying a comprehensive scan.

Regular primary care, careful history-taking, and targeted testing based on symptoms and risk factors remains the evidence-based approach. It's less expensive than whole-body MRI. It's more likely to actually detect things that matter. And it doesn't create cascades of incidental findings requiring follow-up.

For people at very high risk—those with genetic predispositions to disease, those with significant family history of cancer or stroke—specialized screening protocols exist. These are usually organized within medical systems, overseen by medical professionals, and targeted at the specific risks. They're different from commercial whole-body scanning available to anyone with money.

The Radiologist Quality Problem: When Expertise Matters

One element of Clifford's case that deserves emphasis is the importance of radiologist quality and expertise. Not all radiologists are equally skilled. Not all have the same depth of knowledge across different anatomical systems. Some develop deep subspecialty expertise. Others work in high-volume environments where speed matters more than depth.

For screening MRIs, this matters enormously. You need radiologists with genuine expertise in neuro imaging to properly assess the brain and vessels. You need expertise in chest imaging to properly assess the lungs and heart. You need abdominal imaging expertise for the organs. Finding all of that expertise in one person is difficult. Most radiology practices have multiple radiologists with different subspecialties precisely because the expertise is specialized.

Commercial screening centers sometimes employ radiologists on a contract basis, doing screening work part-time. That's cost-efficient from a business perspective. But it might not be optimal for quality. A radiologist who spends 80 percent of their time on specialized clinical cases and 20 percent doing screening work might miss things on screening work that they'd catch if they had more focus.

The fact that Weiner had documented history of falsifying findings on other scans raises additional questions about the screening center's vetting process. How was someone with that history allowed to review critical imaging? What credentialing process existed? Did Prenuvo know about the prior issues?

Moving Forward: Regulatory Approaches and Industry Changes

How should society respond to the problems revealed by Clifford's case? There are several potential approaches.

Regulatory approaches could involve the FDA or other agencies establishing standards for elective screening. Currently, there's minimal regulation of who can perform these scans or how they must be done. Establishing standards for radiologist qualifications, for quality assurance, and for how findings must be communicated could improve safety.

Industry self-regulation is another possibility. Radiology organizations could develop guidelines specific to whole-body screening, establishing standards of practice that screening centers should follow. This would be less heavy-handed than regulation but could still improve quality.

Transparency about outcomes is crucial. Commercial screening centers should be required to track and report outcomes. How many serious findings do they detect? How many incidental findings do they report? How many patients experience harm from incidental findings or missed findings? Currently, that data is proprietary. Making it public would inform consumers and create accountability.

Insurance coverage of whole-body screening probably shouldn't happen. Keeping these scans out-of-pocket maintains appropriate gatekeeping. If insurance covered them, people would get them regardless of value. The out-of-pocket cost currently at least creates some friction, some moment for people to ask whether this is actually a good idea.

Education of consumers is important too. The marketing around these scans often oversells the benefits. Correcting that messaging—explaining that there's no evidence these scans improve outcomes, that they often create incidental findings requiring unnecessary follow-up—would help people make truly informed decisions.

The Broader Pattern: When Screening Fails

Clifford's situation isn't unique, even though his case is unusually well-documented. Throughout medicine, screening has failed catastrophically in exactly this way. A test gives false reassurance. Time passes. Disease progresses. A preventable situation becomes a crisis.

These cases raise important questions about how we think about medical technology. Just because we can scan, should we? Just because we can detect something, should we? Just because wealthy people want something, should we provide it?

The answer from evidence-based medicine is: not necessarily. We should be cautious about screening that lacks evidence. We should be concerned about creating more problems than we solve. We should prioritize interventions with proven benefit over those with only theoretical benefit.

Whole-body MRI screening fails these tests. The evidence doesn't support it. It creates incidental findings and cascades of care. It creates liability risks while offering minimal proven benefit.

As more cases like Clifford's emerge, as litigation accumulates, as costs pile up, the appeal of these screening programs may diminish. That would actually be healthy for medicine and for patients.

FAQ

What is whole-body MRI screening?

Whole-body MRI screening is an elective medical procedure where asymptomatic patients undergo comprehensive magnetic resonance imaging of their entire body, typically covering the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, to identify any potential abnormalities. Unlike diagnostic MRIs ordered for specific symptoms, these scans are performed for preventive purposes and marketed as a way to detect hidden disease early. Commercial providers like Prenuvo market these scans as luxury health services for individuals who want comprehensive screening, typically at a cost of around $2,500 per scan.

Why did Sean Clifford's whole-body MRI miss his artery problem?

Clifford's MRI showed a 60 percent narrowing in his right middle cerebral artery with wall irregularities, but the radiologist failed to flag this critical finding in the report. This likely occurred due to a combination of factors including the volume of images to review, satisfaction of search error where finding minor incidental findings led to incomplete evaluation, lack of specialized vascular expertise, and potential quality control issues at the commercial screening facility. The radiologist's documented history of falsifying findings on other scans raises additional questions about his judgment and credibility in interpreting the imaging appropriately.

What does the American College of Radiology say about whole-body MRI screening?

The American College of Radiology explicitly states that there is insufficient evidence to justify whole-body MRI screening and no documented evidence that total body screening is cost-efficient or effective in prolonging life. The ACR also expresses concern that these procedures identify numerous non-specific findings that don't improve patient health but result in unnecessary follow-up testing, procedures, and significant expense. The ACR's position reflects mainstream evidence-based medicine's skepticism about screening without proven benefit.

What are incidental findings and why do they matter?

Incidental findings are unexpected abnormalities discovered during imaging performed for other reasons—in this case, during whole-body screening when looking for anything wrong. Studies show that more than 90 percent of people undergoing whole-body MRI screening have at least one incidental finding requiring documentation. Most are completely benign and will never cause problems, yet they typically trigger follow-up imaging, specialist referrals, and unnecessary anxiety. This creates what's called an "incidental finding cascade" where one scan generates a series of additional medical appointments and procedures, often for conditions that would never have caused harm.

How does whole-body MRI screening compare to other screening methods?

Unlike evidence-based screening programs such as mammography for breast cancer in women over 50 or lung CT screening in heavy smokers—both of which show documented mortality benefits—whole-body MRI screening lacks evidence that it actually improves outcomes or extends life. Targeted screening for specific conditions in high-risk populations works because it focuses expertise, detects disease early enough for intervention, and has been validated through research. Whole-body screening casts too wide a net, lacks focus, generates excessive incidental findings, and has no demonstrated benefit, making it fundamentally different from evidence-based screening approaches.

What should people do instead of getting whole-body MRI screening?

For most people, evidence supports traditional preventive medicine: lifestyle factors like regular exercise, healthy diet, not smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, and stress management provide more benefit than any screening test. People should have regular primary care with a doctor who knows their full medical and family history, who can assess individual risk factors, and who can recommend targeted screening for specific conditions where evidence supports it. For people with specific risk factors or family history of certain diseases, targeted screening protocols exist and should be discussed with their healthcare provider—but comprehensive whole-body scans aren't necessary for most people and may create more problems than benefits.

What legal implications does Clifford's lawsuit have for screening companies?

Clifford's case potentially sets precedent for radiologist and screening company liability when serious findings are missed on elective screening scans. If he prevails, it establishes that radiologists have a clear obligation to flag potentially serious incidental findings appropriately, which could increase liability risk for screening companies and change their incentive structures. The case also demonstrates the dangers of allowing radiologists with documented history of falsifying findings to review critical imaging, raising questions about credentialing and quality control at screening facilities. As such cases accumulate, they could make the elective screening business less profitable and attractive if liability becomes sufficiently high.

Conclusion: The Future of Elective Health Screening

Sean Clifford's story is a powerful counternarrative to the glossy marketing around whole-body MRI screening. It's the story of a man who did what he was supposed to do—sought preventive health care, paid for comprehensive screening, received apparent reassurance—and then suffered catastrophic consequences precisely from the finding the screening supposedly would have detected.

The case isn't primarily about incompetence, though that may have played a role. It's about the inherent contradictions and problems embedded in the whole-body screening model itself. When you scan everyone for everything, you get noise. When radiologists review hundreds of images looking for anything wrong, important findings get lost. When business incentives favor volume and speed, quality suffers. When incidental findings cascade into unnecessary medical care, patients get hurt.

The broader medical establishment has learned these lessons about screening. We've moved toward evidence-based approaches, toward targeted screening in high-risk populations, toward skepticism about screening that hasn't proven itself. Yet the commercial screening industry persists, marketing comprehensive scans to wealthy consumers seeking reassurance.

As cases like Clifford's emerge, as legal liability accumulates, as more people question whether these scans actually provide value, the appeal of whole-body screening will likely diminish. That's probably good for medicine and for patients.

The lesson isn't that medical imaging is bad. MRI is an extraordinary technology for diagnosis. The lesson is that screening—the systematic search for disease in asymptomatic people—requires clear evidence that you're improving outcomes. Just because you can detect something doesn't mean you should. Just because you're finding things doesn't mean you're helping.

For someone considering whole-body MRI screening, the evidence suggests investing that $2,500 in lifestyle improvements, in regular primary care with a knowledgeable physician, in targeted screening for specific conditions where evidence supports it. That approach is less glamorous than a comprehensive scan at a fancy facility. It won't make for good marketing. But it's far more likely to actually improve health outcomes.

Clifford's case stands as a cautionary tale about the limits of technology, the importance of evidence, and the danger of creating reassurance from tests that don't actually provide safety. As more cases emerge, as litigation accumulates, the medical establishment will likely double down on skepticism about whole-body screening. That would be appropriate. Some things, no matter how technologically impressive, simply don't work the way their marketing suggests.

Key Takeaways

- Whole-body MRI screening lacks evidence that it improves outcomes or extends life, despite premium pricing and celebrity marketing

- The case reveals how screening scans create problems: radiologist fatigue, satisfaction-of-search errors, and cascades of unnecessary follow-up for incidental findings

- Over 90% of asymptomatic people undergoing whole-body MRI have at least one incidental finding requiring documentation and potential follow-up

- The American College of Radiology explicitly states there is insufficient evidence to justify whole-body screening and expresses concern about unnecessary procedures

- Evidence-based screening (mammography, lung CT in high-risk populations) has documented mortality benefits, whereas whole-body screening does not

Related Articles

- Nigeria vs Morocco AFCON 2025 Semi-Final: Free Streaming Guide & How to Watch

- Type One Energy Raises $87M: Inside the Stellarator Revolution [2025]

- Euphoria Season 3 Trailer Breakdown: The Time Jump, Wedding, and What's Next [2025]

- Fitness Apps Privacy Guide: How to Stop Data-Hungry Apps [2025]

- LG C6 OLED TV 2026: Features, Specs, Pricing & Alternatives

- Google Gemini Personal Intelligence: Scanning Your Photos & Email [2025]

![Whole-Body MRI Screening: Why Doctors Question Elective Scans [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/whole-body-mri-screening-why-doctors-question-elective-scans/image-1-1768412212785.jpg)