Introduction: The Fusion Breakthrough Nobody Expected

When a startup quietly raises

Here's what makes this different from the dozen other fusion startups promising clean energy: Type One isn't chasing the same approach as everyone else. While companies like Commonwealth Fusion Systems and TAE Technologies pursue magnetic confinement through tokamaks, Type One has chosen the stellarator design, a more complex but potentially more stable path to commercial fusion power.

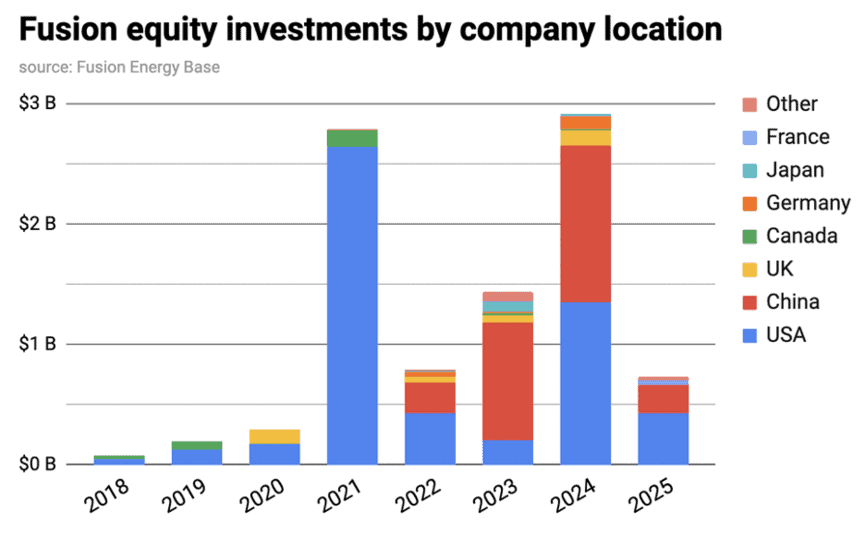

The timing is remarkable. We're in a moment where data center electricity demand is becoming the primary constraint on AI growth. Microsoft is evaluating nuclear facilities. Google is signing power purchase agreements with hydrogen plants. Amazon is racing to secure gigawatts of clean energy. Against this backdrop, Type One's $160+ million in total venture funding suddenly looks like rational capital allocation rather than speculative tech betting.

But here's what most headlines miss: this funding round reveals something deeper about how private capital now views energy infrastructure. It's not about distant promises anymore. It's about solving a problem that's hitting enterprise balance sheets right now. Type One's first commercial plant, Infinity Two, won't come online until the mid-2030s, but the demand and the buyer are already committed. The Tennessee Valley Authority signed a contract. That's not venture theater. That's a power utility betting its reputation on this working.

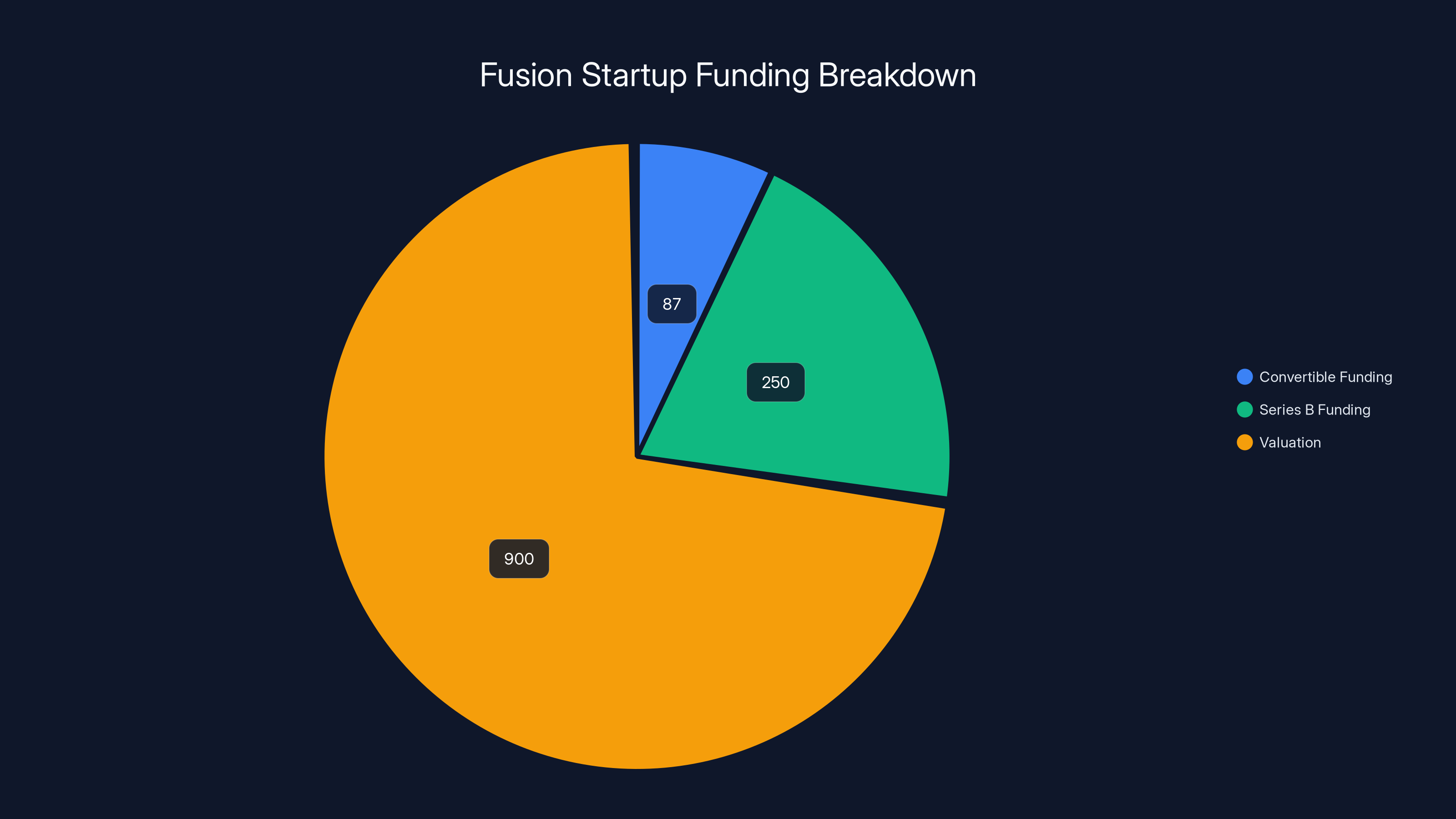

In this deep dive, we're going to explore why Type One chose stellarators, how they plan to actually build commercial plants, what their technology solves that others don't, and whether this $250 million Series B signals that fusion is finally graduating from "promise stage" to "deployment stage." More importantly, we'll examine what this means for the future of data center power and the competitive landscape between different fusion approaches.

The stakes are enormous. The global power generation market is measured in trillions. If Type One executes, it changes everything. If it doesn't, the capital will have learned a lesson about fusion timelines that might delay other breakthroughs. Let's figure out which scenario is more likely.

TL; DR

- Massive funding momentum: Type One Energy raised 250M Series B at160M

- Unique technology choice: Uses stellarator magnetic confinement design instead of more common tokamak approach, potentially offering superior plasma stability

- Real customer commitment: TVA signed contract to build Infinity Two plant generating 350 megawatts by mid-2030s, proving market demand beyond venture theater

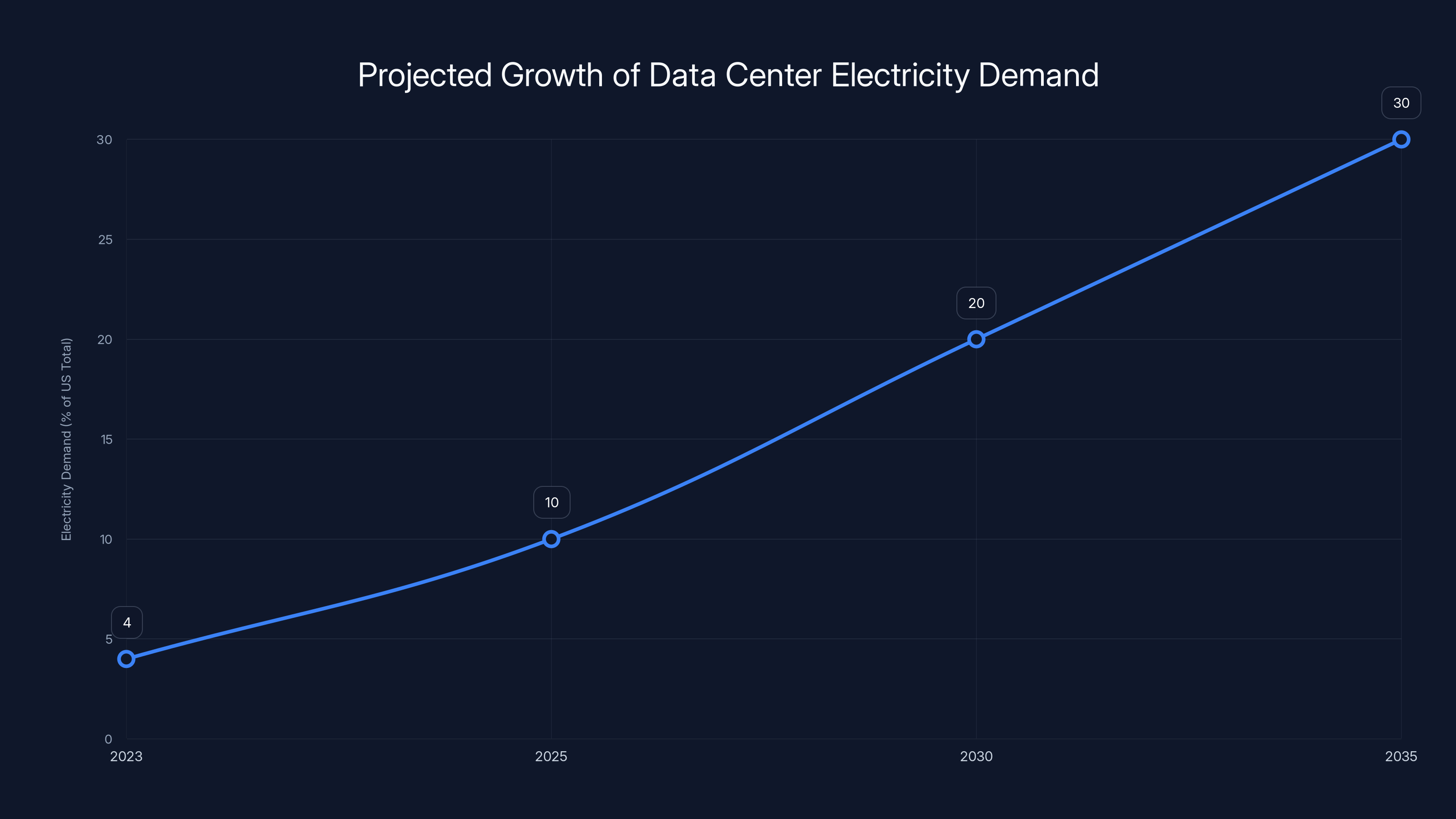

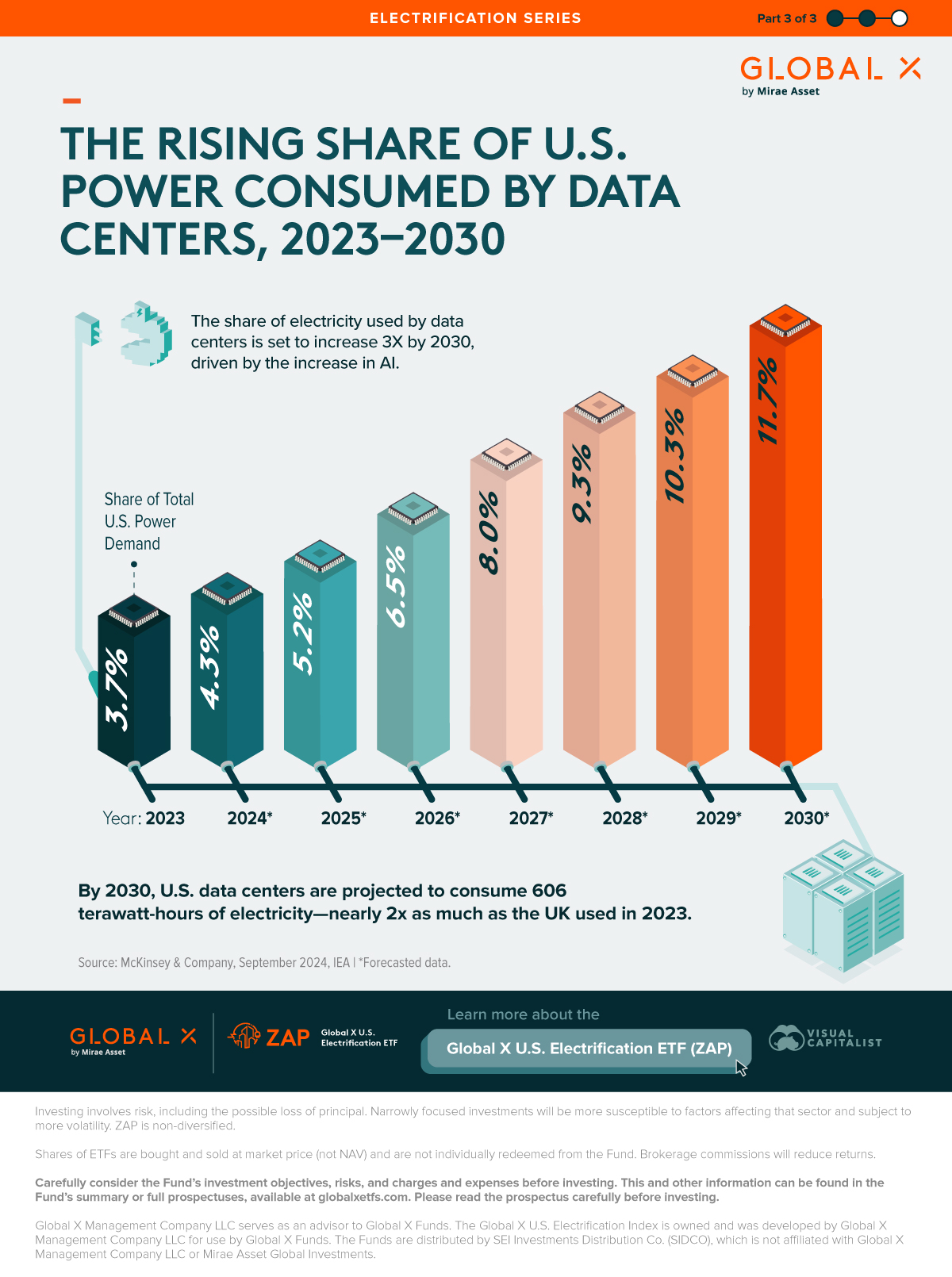

- Data center driven: Global electricity demand from data centers expected to triple by 2035, creating $billions in addressable market for clean baseload power

- Asset-light model: Sells technology to utilities instead of building plants, dramatically reducing capital requirements and operational risk

Data center electricity demand is projected to increase from 4% to 30% of total US consumption by 2035, highlighting a significant growth trend. Estimated data.

The Data Center Power Crisis That Nobody Wants to Admit

Data centers currently consume about 4% of global electricity. That number sounds manageable until you realize it's growing at rates that are making utility executives lose sleep. Type One's funding becomes comprehensible only when you understand what's driving it: artificial intelligence has created an electricity shortage that nobody adequately planned for.

The numbers are brutal. Data center electricity demand is projected to nearly triple by 2035, growing from current levels to approximately 30% of total US electricity consumption. That's not gradual. That's transformational. Meanwhile, US electrical capacity additions are measured in gigawatts per year. The gap between supply and demand is a capital opportunity measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

There's a second constraint most people don't discuss: geographic concentration. Data centers cluster where power is reliable and cheap. That limits where AI companies can build. A single large language model training run can consume 15-20 megawatts continuously. A moderate-sized AI inference center can demand 100+ megawatts. Utilities in regions with limited spare capacity are literally turning away customers. Google has data centers waiting for power. Microsoft is evaluating small modular reactors. Amazon is signing hydrogen contracts. The constraint is real and immediate.

This creates the perfect market timing for Type One. Tokamak-based fusion startups are still in the "physics works in a research facility" stage. Inertial confinement fusion (the National Ignition Facility approach) is further away still. But stellarators have one key advantage: multiple existing facilities have proven they can maintain stable plasma for extended periods. That's not fusion energy, but it's proof that the basic confinement physics works reliably.

Type One's Series B isn't funding pie-in-the-sky engineering. It's funding a company that has already agreed with a power utility to build its first commercial plant. The TVA isn't investing in hopes. They signed a contract that includes timeline commitments and performance specifications. That transforms the narrative from "Will fusion ever work?" to "Will this specific team execute their contract on time?"

Consider the utility's perspective. The TVA needs 350 megawatts of reliable, zero-carbon baseload power in the mid-2030s. They could build natural gas plants (fast, proven, but creates carbon liability). They could add solar and wind (proven, cheaper now, but intermittent). Or they could partner with Type One and get baseload zero-carbon power that occupies a fraction of the land. From a portfolio diversification standpoint, Type One is risk-hedging for the TVA.

The venture capital perspective is similarly clear. Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Bill Gates' climate tech fund, doesn't invest in speculative physics. It invests in technologies that have proven the underlying physics and now need capital to build the engineering. Type One fits that pattern exactly.

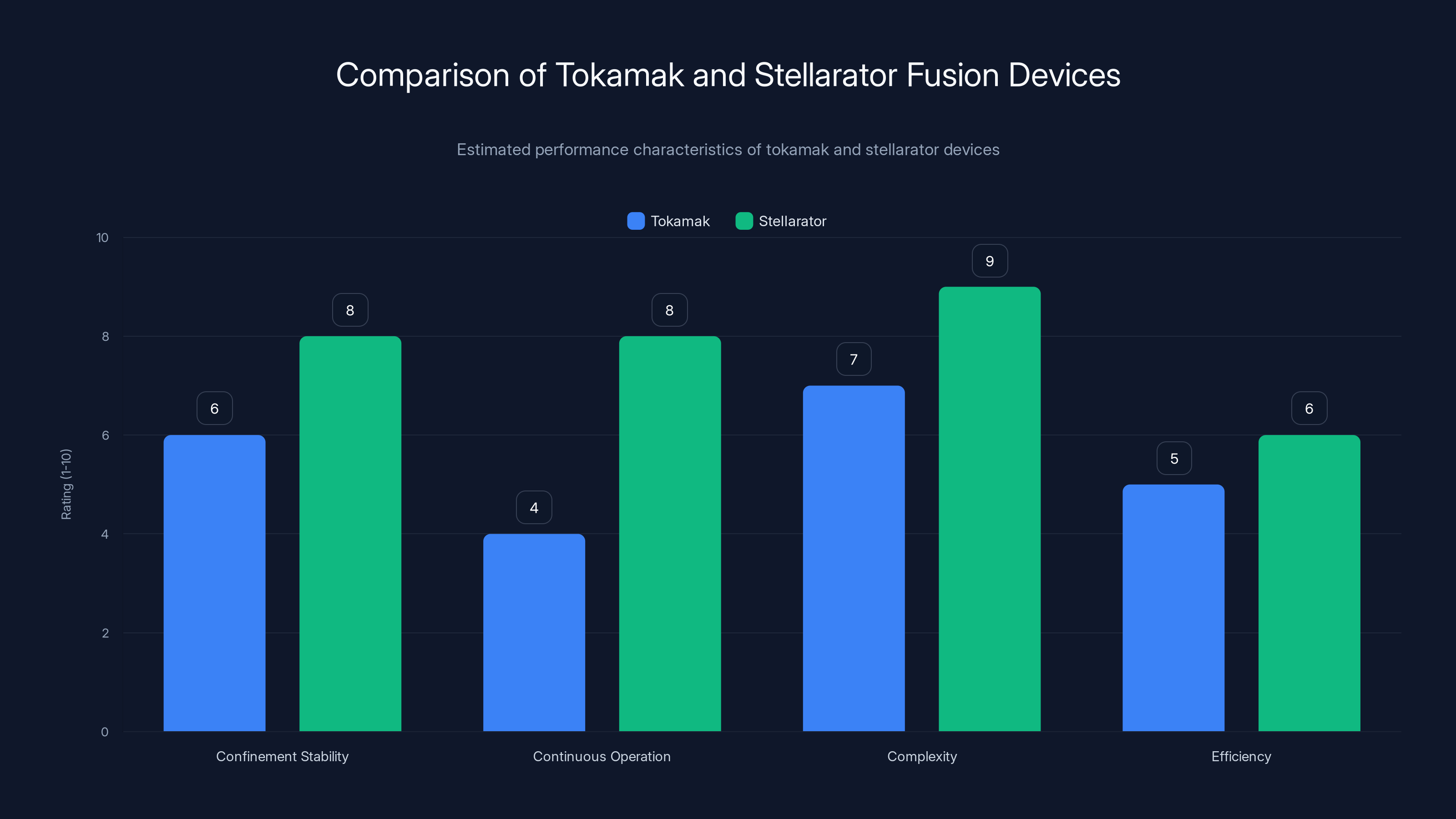

Understanding Stellarators: Why Type One Chose Complexity

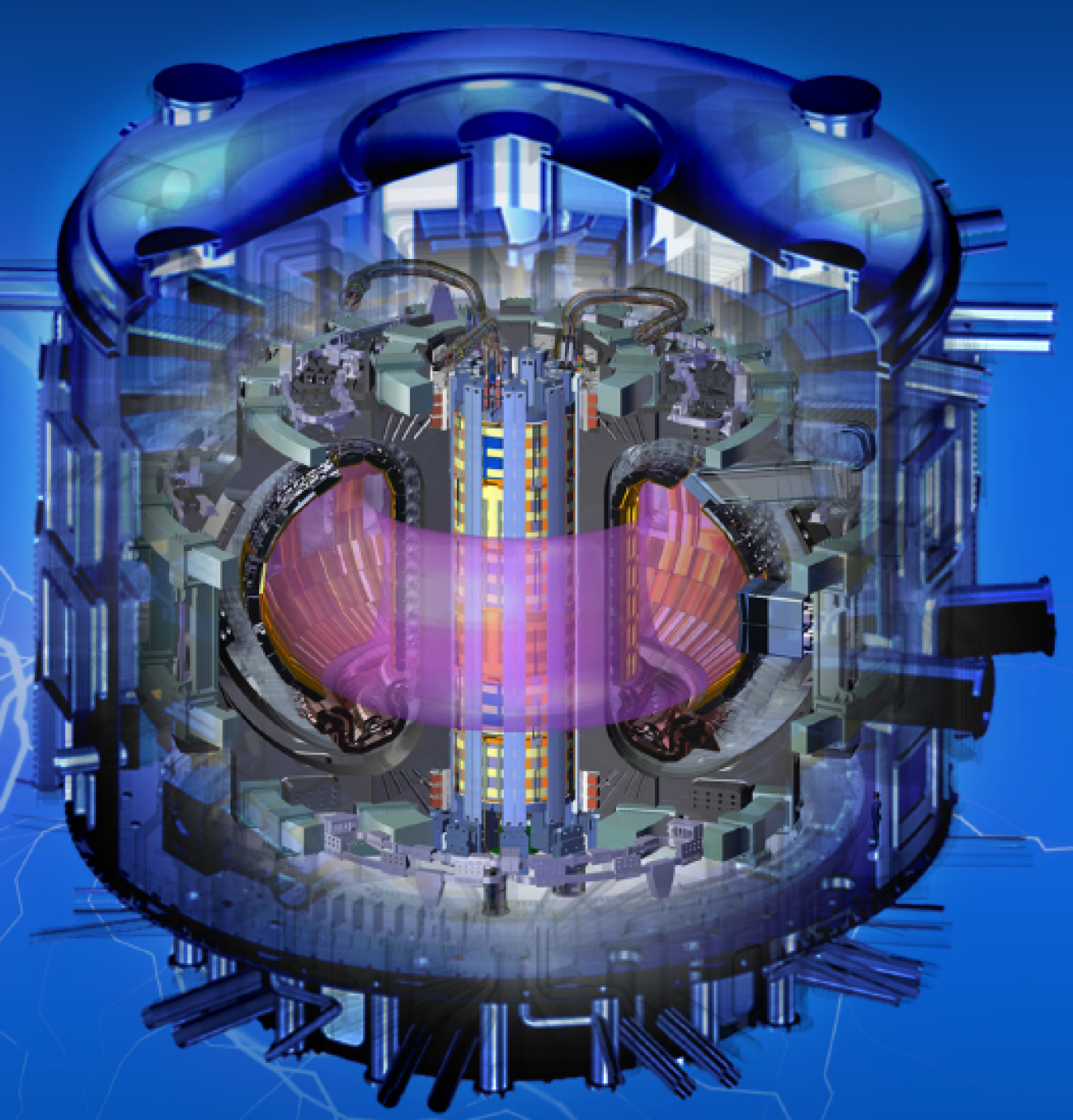

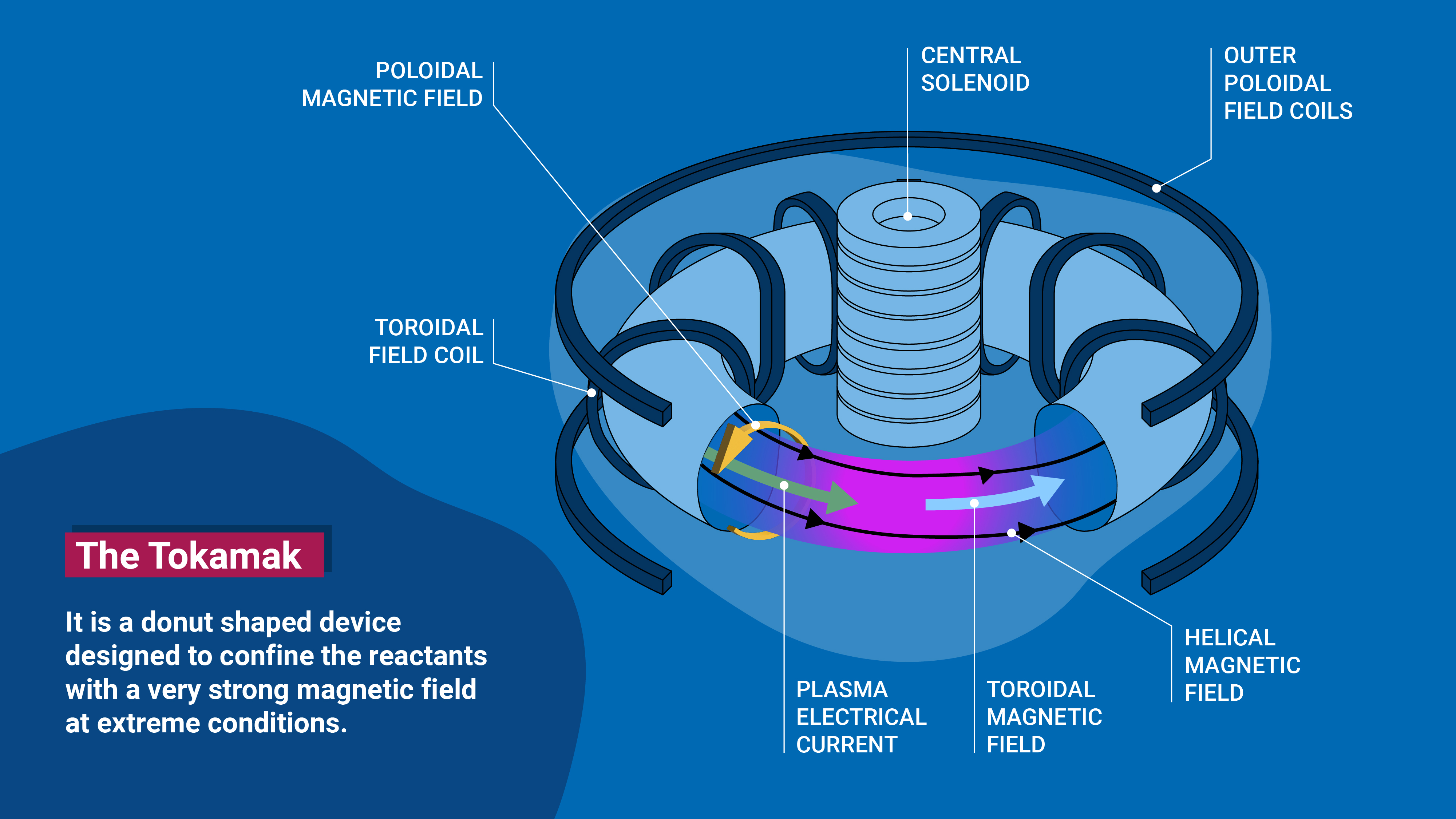

If you asked 100 physicists to name fusion reactor designs, tokamaks would dominate the conversation. International ITER project? Tokamak. China's EAST reactor? Tokamak. JT-60U in Japan? Tokamak. The tokamak is the default answer in fusion research, which is why it's surprising that Type One deliberately chose the stellarator path instead.

Here's the technical distinction that matters: a tokamak uses a doughnut-shaped plasma column, with magnetic field lines arranged in concentric circles around it. It's mechanically simple compared to a stellarator. But tokamaks have an intrinsic instability problem. The plasma wants to escape laterally. Tokamaks solve this through "active feedback control," essentially continuously nudging the plasma back into shape with real-time adjustments. It works, but it requires sophisticated control systems and has limits to how long you can maintain stable operations.

A stellarator, by contrast, has magnets arranged in a twisted, three-dimensional pattern that creates a naturally stable magnetic field geometry. Think of it like a twisted doughnut where the twist itself provides the confinement force. The plasma wants to escape, but the geometry of the field itself prevents it from doing so. This means stellarators can theoretically run continuously without constant active feedback adjustments.

That's not theoretical either. Germany's Wendelstein 7-X stellarator maintained stable plasma for over 100 seconds in 2016. Japan's Large Helical Device has sustained plasma for hours. Those achievements don't exist in the tokamak world. The longest tokamak pulses are measured in minutes.

But there's a catch (there's always a catch): stellarators are mechanically complex. The magnets must be precisely positioned in three-dimensional space. The engineering tolerances are tighter. The construction is more difficult and expensive. This is why most fusion research pursued tokamaks even though many physicists knew stellarators had superior physics. The engineering challenge seemed harder.

Type One's bet is that modern manufacturing, CAD design, and superconducting magnet technology have made the engineering challenge solvable. They're not chasing fundamentally new physics. They're applying 21st-century engineering to a physics approach that's been known for decades but was previously too expensive to pursue seriously.

That's a fundamentally different business model than tokamak competitors. Commonwealth Fusion Systems (the tokamak player) is working on reducing tokamak plasma control complexity through better feedback systems and superconducting magnets. Type One is saying: "Let's just use the design that doesn't have that problem in the first place."

From a venture capital perspective, this is compelling because it's not dependent on breakthrough physics. It's dependent on execution engineering. The physics works. The question is whether you can build it at cost and on timeline.

Type One Energy has raised

How Magnetic Confinement Fusion Actually Works

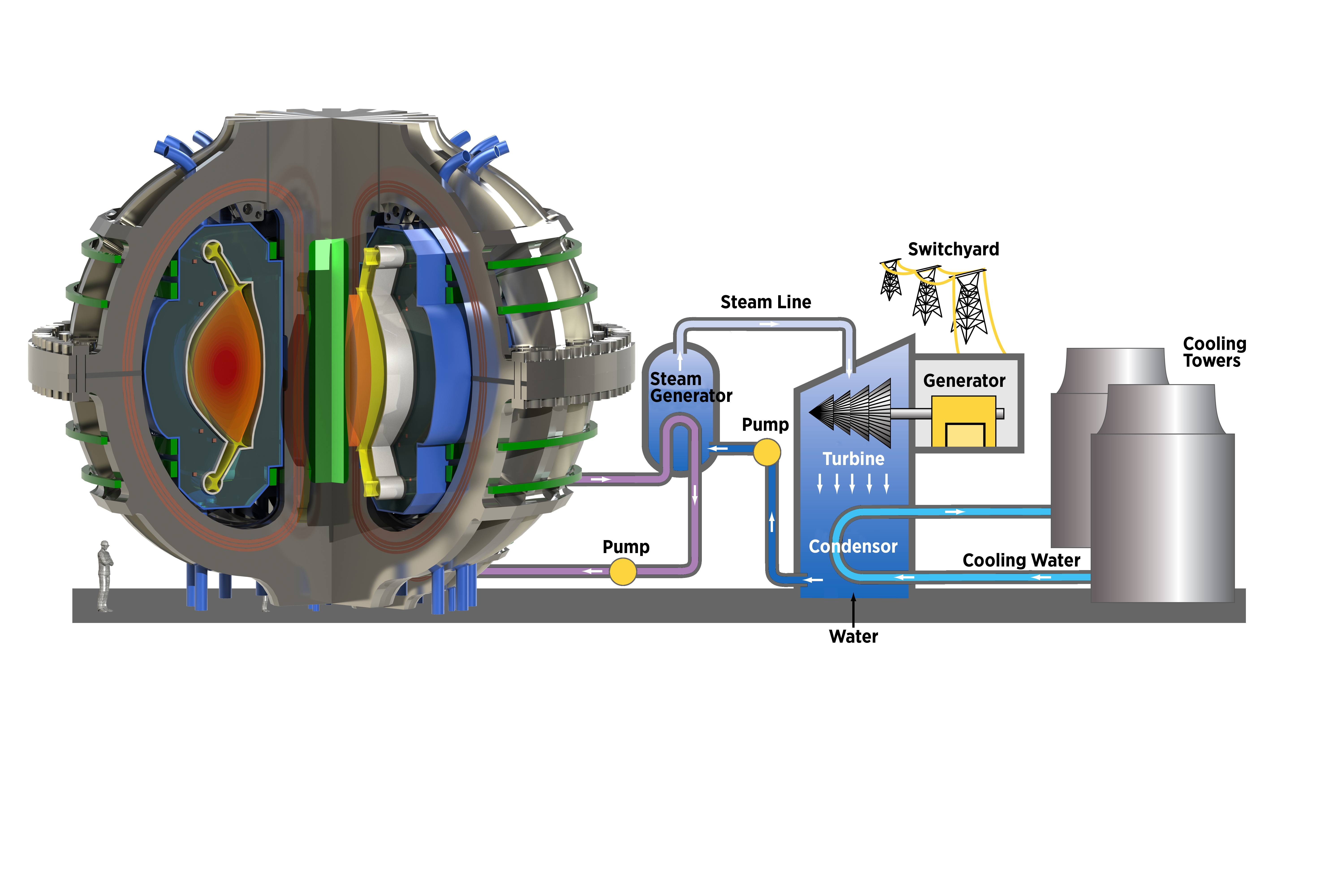

Fusion reactions happen when atomic nuclei collide at such high velocities that the strong nuclear force overcomes the electrostatic repulsion that normally keeps nuclei apart. Two hydrogen isotopes fuse, and you release incredible amounts of energy. That's the science. The engineering problem is that fusion reactions only happen at temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius.

At those temperatures, you can't use physical containers. The plasma would vaporize anything solid that touched it. Instead, you use magnetic fields. Charged particles curve when moving through magnetic fields. If you create a strong enough magnetic field in the right geometry, you can essentially confine the plasma using invisible walls.

The mathematics is elegant but intense. The magnetic field creates a potential energy well. The plasma particles bounce around inside this well without touching the physical walls. In a tokamak, external coils generate the confinement field, and the plasma itself generates additional field through its current. In a stellarator, external magnets create the entire confinement field. The plasma doesn't need to generate its own field.

This sounds like a minor distinction, but it's not. In a tokamak, you're relying partly on the plasma to help confine itself. If the plasma becomes too unstable, the self-generated field can't do its job, and you lose confinement. In a stellarator, the external magnets provide full confinement regardless of plasma state. The plasma can be less stable, and the geometry still holds it in place.

That's why stellarators can theoretically run continuously while tokamaks pulse. Once a tokamak loses plasma confinement, you have to completely reset and start again. It's like the difference between a system that fails gracefully under stress versus one that fails catastrophically.

For a commercial fusion power plant, continuous operation is essential. A plant that can only run in pulses and requires reset time between pulses would have terrible capacity factor and terrible economics. You'd be building infrastructure designed to run continuously but operating it at 20-30% actual output. That's not economically viable.

This is where Type One's engineering challenge becomes clear. They need to build magnets strong enough to confine plasma at commercial density and temperature, arrange them in a three-dimensional geometry precise enough to maintain confinement, and do it at a cost that's economically competitive with other power sources.

The magnets themselves are superconducting, which is another design choice that matters. Superconducting magnets require cryogenic cooling (near absolute zero temperatures), but they can generate incredibly strong fields with minimal electrical losses. This is essential because the power required to generate confinement fields is one of the largest energy costs in a fusion reactor. If your magnets lose 30% of their energy as heat, your reactor generates heat but consumes most of it just maintaining the magnetic field. That's not fusion energy. That's a very expensive space heater.

The Infinity Two Project: When Speculation Becomes a Real Contract

Most fusion startups talk about their "first commercial plant" as if it's around the corner. Most of those plants don't exist beyond Power Point slides and engineering studies. Infinity Two is different. It's a real project with a real customer, a real timeline, and a real contract.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, one of the largest public utilities in the United States, signed an agreement with Type One Energy to build a 350-megawatt fusion power plant at the site of the former Bull Run Fossil Plant in Tennessee. The former coal plant was retired in 2023, creating both a symbolic opportunity (replacing coal with fusion) and practical advantages (existing electrical infrastructure, transmission lines, grid connections).

350 megawatts is meaningful capacity. To put it in perspective, that's equivalent to the power consumption of approximately 260,000 homes. It's not utility-scale grid demand (that's measured in tens of gigawatts), but it's significant infrastructure. It's the power output of a medium-sized conventional power plant, with all the same functions except it produces zero carbon emissions and zero radioactive waste.

The timeline is mid-2030s for operational status. That's ambitious (only about 10 years away) but not insane. It's long enough to engineer and build, but close enough that it focuses engineering efforts on realistic designs rather than speculative ones. Most tokamak startups talk about 2040-2050 timelines. Type One is committing to 2035.

The contract structure is crucial and often overlooked: Type One isn't building or operating the plant. The TVA will build it, own it, and operate it. Type One is selling its technology, designs, and engineering expertise. This is a fundamentally different business model than what most fusion startups envision.

Most fusion startups imagine themselves as power producers, building plants and selling electricity. That's a capital-intensive, operationally complex business. Type One's model is more like being a technology licensor or equipment provider. The TVA takes on the capital expenditure risk, the operational risk, the grid integration risk. Type One takes on the technology delivery risk. That's a better risk trade-off for a venture-backed startup.

This model also has profound implications for scaling. If Type One's technology works for the TVA, other utilities can license it and build their own plants. You don't need Type One to raise enough capital to build multiple plants. You need other utilities to find Type One's technology attractive enough to invest their own capital. That's a much more scalable growth model.

The TVA's commitment is also notable because utilities are conservative. They don't partner with startups for mission-critical infrastructure unless they've done extensive due diligence. The fact that the TVA signed Infinity Two suggests Type One's engineering and physics have passed serious scrutiny from serious technical people.

The Funding Landscape: Why $160+ Million in Venture Capital Matters

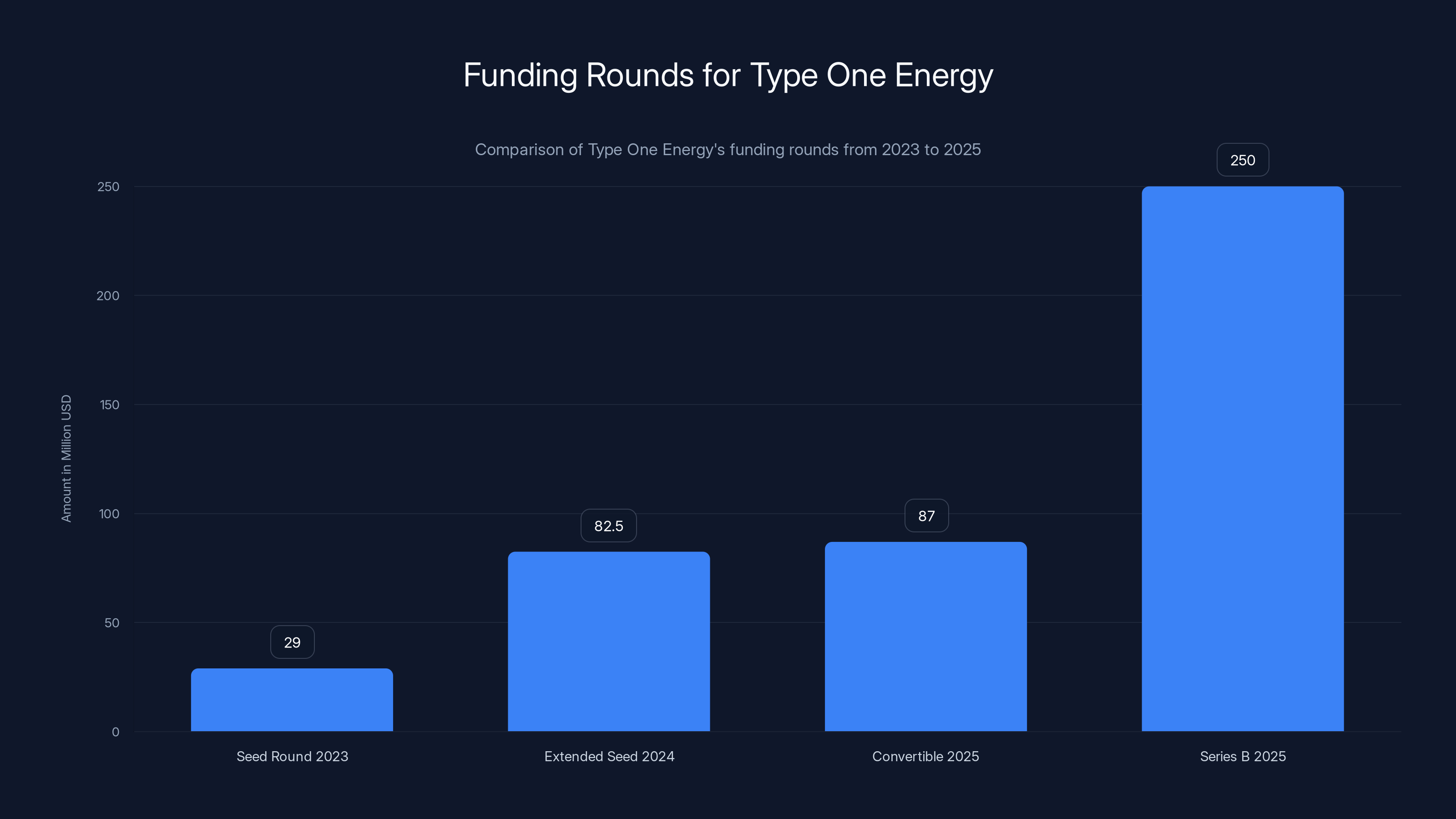

Type One Energy's

Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Bill Gates' investment fund, is the lead investor and has been since Type One's seed round. This isn't celebrity capital or speculative betting. Breakthrough Energy has a track record of investing in climate and energy technologies at scale. They funded companies like Commonwealth Fusion Systems, Canadian Solar, and others. They employ engineers and scientists who understand fusion physics. Gates himself has written extensively about the role nuclear and fusion power will play in decarbonization.

The seed round was

Why convertible funding specifically for the

Compare this to other fusion startups: Commonwealth Fusion Systems raised at much higher valuations. TAE Technologies has struggled to raise at previous valuation levels. The variation in valuation reflects investor confidence in different approaches and different teams. Type One's $900 million valuation is sophisticated capital saying: "We believe this team and this technology, but we're not paying unicorn prices yet."

The geographical diversity of investors also matters. Type One's backers include Doral Energy Tech Ventures and TDK Ventures alongside Breakthrough Energy Ventures. TDK is a massive Japanese conglomerate with serious materials science expertise and strategic interest in next-generation power technologies. Doral is focused on energy infrastructure. These aren't random investors. They're strategic investors who understand the technology and have a financial interest in it succeeding.

The funding also signals something about the fusion competitive landscape. Multiple billion-dollar venture funds are now backing fusion companies. Khosla Ventures, Lowercarbon Capital, and others have deployed billions into climate and energy. The availability of capital is not the constraint. Execution is.

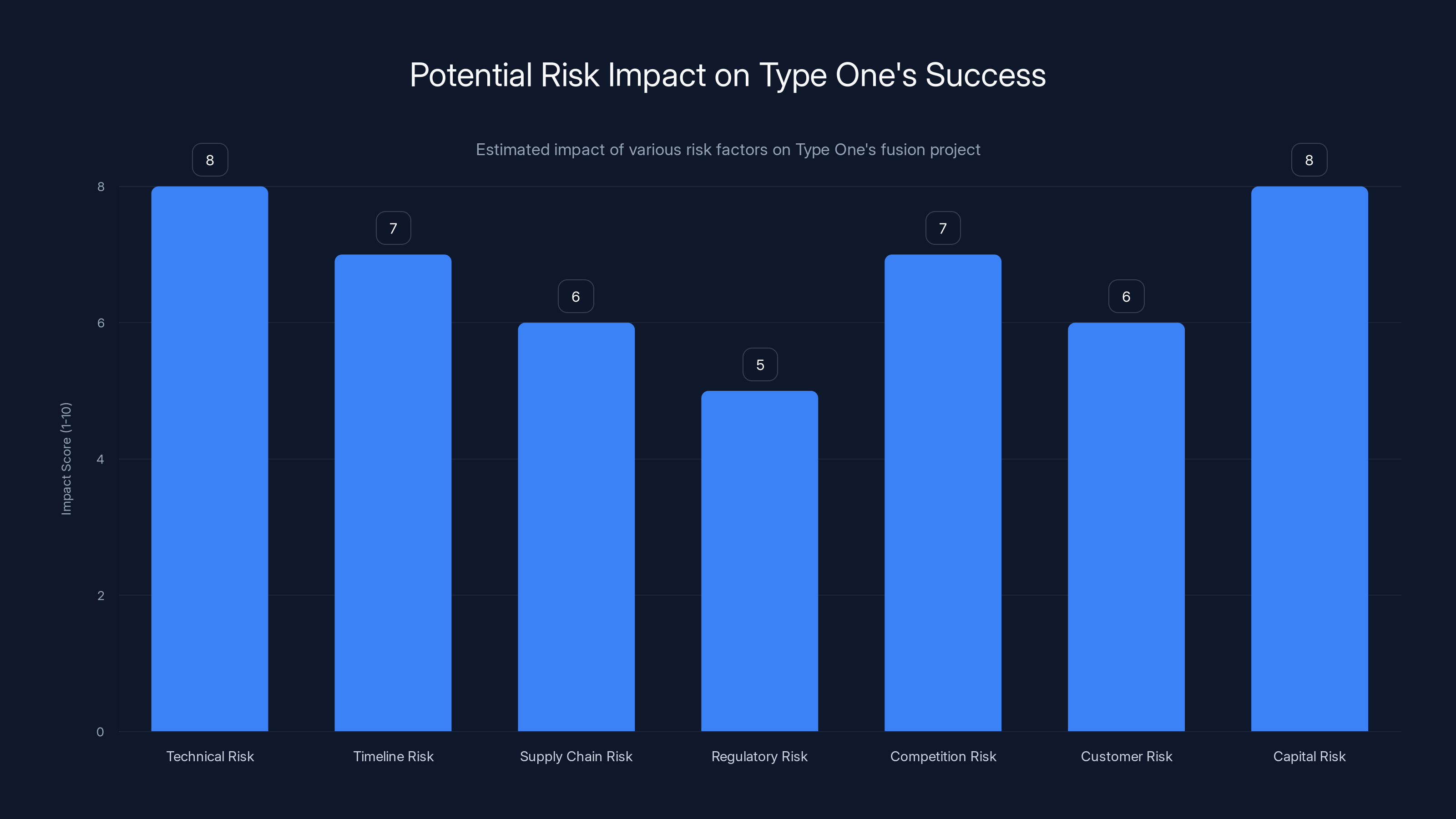

Technical and capital risks are estimated to have the highest impact on Type One's potential failure, with scores of 8 out of 10. Estimated data.

The Physics-to-Engineering Bridge: Why Most Fusion Startups Stumble

Fusion physics is now solved. Multiple facilities have demonstrated that deuterium-tritium fusion reactions can be sustained at temperatures and densities that generate more energy from the fusion reaction than was consumed creating the plasma. The National Ignition Facility achieved this in December 2022. Multiple other facilities have achieved net energy from fusion under laboratory conditions.

The problem isn't physics anymore. It's engineering at scale and cost. And this is where most fusion startups hit a wall that venture capital can't fix by throwing money at it.

The challenge is that fusion reactor engineering is dominated by problems that don't scale well. A 1-megawatt fusion reactor and a 1,000-megawatt fusion reactor aren't 1,000 times more of the same thing. They're fundamentally different engineering problems.

Take magnet engineering. You can use superconducting magnets rated at 20 Tesla (a unit of magnetic field strength) for a research reactor. But scaling to commercial power plants means making those magnets bigger, more complex, more robust. The engineering requirements change. You need magnets that can cycle thousands of times (cooling down, heating up, cycling again) without degrading. You need magnets that can operate in radiation environments where neutrons from fusion reactions gradually damage the materials.

Or consider tritium breeding. A deuterium-tritium fusion reaction consumes tritium, a rare and radioactive hydrogen isotope. There's only a few kilograms of tritium on Earth (most exists only in fusion reactors). For a fusion plant to be sustainable, it needs to breed its own tritium from lithium blankets that surround the reactor core. Conceptually simple. Practically? It's one of the most complex engineering challenges in fusion. You need to design blanket geometry, materials, heat transfer systems, and tritium extraction. This requires materials science, fluid dynamics, neutronics, and chemical engineering all working together perfectly.

These problems require sustained, focused engineering effort over years. They're not areas where hiring more people and spending more money dramatically accelerates progress. They require deep expertise, iteration, and often fundamental research.

Type One's choice of stellarator addresses some of these challenges (continuous operation without the pulsing-power-cycle problem) but creates others (more complex magnet engineering). The company's strategy is implicit: we're going to solve our engineering problems through precision manufacturing and advanced materials, not through next-generation physics breakthroughs.

That's a reasonable bet for a venture-backed company. You can hire great manufacturing engineers. You can license advanced materials technology. You can partner with utilities to validate your designs. You can't, however, make fundamental physics breakthroughs on demand. Most fusion startups are betting on technology advances that may or may not happen within their funding timeline. Type One is betting on execution of known engineering challenges.

Why Utilities Care About Fusion Now (And Why That Changes Everything)

Utilities have historically been risk-averse institutions. They build power plants designed to operate for 50+ years. They want proven technology, reliable supply chains, and predictable costs. Fusion is none of those things. So why is the TVA signing a contract with a fusion startup?

The answer is that utilities are now facing constraints that make experimental technology look attractive compared to the alternative: "We can't meet demand with existing technology."

Electricity demand is growing faster than grid capacity can expand. Solar and wind are proven and increasingly cost-competitive, but they're intermittent. They don't provide baseload power. When the sun sets and the wind stops blowing, you need something else running. Traditionally, that's natural gas or coal plants. But natural gas has carbon emissions, supply chain volatility, and regulatory risk. Coal has even more regulatory risk and extreme carbon liability.

The options for utilities are becoming constrained. Build more natural gas plants (carbon liability)? Invest heavily in battery storage (capital intensive and still doesn't solve the deep seasonal storage problem)? Expand nuclear (regulatory challenges, long development times)? Or partner with a fusion startup on an experimental project that could provide gigawatt-scale zero-carbon baseload power?

From the TVA's perspective, Infinity Two is hedging. It's a 350-megawatt bet that fusion works. Even if it costs more than expected or takes longer than planned, the cost is acceptable compared to the alternative: being unable to meet demand from a major customer.

There's also a regulatory advantage. Regulators are now actively interested in promoting decarbonization. Utilities that are investing in novel zero-carbon generation have political cover. The TVA can tell regulators and the public: "We're trying everything, including fusion." That's good politics at a time when climate change is a major policy issue.

The strategic value to Type One is profound. Most fusion startups need to convince utilities to take a risk on their technology. Type One has a utility already convinced. That changes the engineering timeline, the funding availability, and the probability of success. It's easier to raise Series B funding when you have a signed contract with a power utility than when you have a signed partnership with a university.

The Tokamak vs. Stellarator Race: Two Paths, Different Bets

The fusion industry isn't monolithic. There are fundamentally different technical approaches competing. Understanding the differences explains why Type One made its technology choice and why other startups made different choices.

Tokamaks dominate funded fusion research. Commonwealth Fusion Systems (the tokamak leader) is building SPARC, a demonstration reactor intended to generate more fusion power output than electrical input. If SPARC works, it proves tokamak viability at commercial scale. Commonwealth's strategy is to raise capital, build SPARC, prove the concept, and then license the technology to utilities.

Tokamaks have some advantages. The physics is better understood from decades of research. Existing facilities like ITER provide a path to scaling. The engineering challenges are clear (even if solving them is difficult). But tokamaks have the fundamental limitation of plasma pulsing and active feedback control.

Stellators have different trade-offs. The physics is proven (stability without active feedback), but the engineering is more complex. There are fewer existing facilities to learn from. The magnet engineering is more demanding. But the continuous operation capability is genuinely valuable for commercial power generation.

There's also a speed-to-market consideration. Commonwealth Fusion Systems claims SPARC could be operating by late 2020s. Type One targets mid-2030s for Infinity Two. That's a real timeline difference. If Commonwealth's SPARC works and operates ahead of schedule, it could validate tokamak technology commercially years before Type One's stellarator is proven. That would dramatically shift capital allocation toward tokamak startups.

Conversely, if tokamak technology runs into unexpected challenges at scale, stellarator startups could find themselves with a clear technology path and increasing capital interest. The race is real, and the stakes are enormous.

Venture capital is hedging by funding both. Breakthrough Energy Ventures and others fund both tokamak and stellarator startups. That's rational portfolio strategy. One approach will likely dominate, but the other might carve out a niche (perhaps for specific applications, geographic regions, or utility partnerships).

Type One's advantage in this race is the TVA contract. A signed utility partnership is worth more than any amount of venture funding in the fusion industry. It proves demand, provides customer feedback, and de-risks the technology validation.

Stellarators offer better confinement stability and continuous operation potential compared to tokamaks, though they are more complex. Estimated data based on typical device characteristics.

Materials Science: The Unsexy Problem That Will Make or Break Fusion

People talk about the exciting parts of fusion: the elegant physics, the prospect of unlimited clean energy, the engineering challenge. Nobody wants to talk about materials science. But materials science is probably more important to fusion success than any other factor.

Here's why: inside a fusion reactor, neutrons from fusion reactions bombard the chamber walls at incredible energies. Over months and years of operation, this radiation gradually damages the material. Atoms get displaced from their lattice positions. Helium builds up in the material (a byproduct of some nuclear reactions). The material becomes brittle, weak, and eventually needs replacement.

This is called "radiation damage" and it's one of the oldest problems in nuclear engineering. Fission reactors have dealt with it for 70 years. The solution is material science: developing alloys and ceramics that tolerate radiation better than traditional steel.

But fusion creates more extreme conditions than fission. The neutron energies are higher. The materials need to handle higher temperatures. They need to tolerate more frequent thermal cycling. The traditional nuclear materials that work in fission reactors aren't necessarily adequate for fusion.

Type One's choice of stellarator actually has a materials advantage. The continuous operation means more stable thermal conditions. The thermal cycling is less severe. That's easier on materials. Tokamak's pulsed operation creates thermal cycling every pulse, which stresses materials more.

But the core challenge remains: you need materials that can survive 30+ years of operation in a neutron environment that would damage conventional steel in months. The fusion industry has been working on this since the 1970s. Progress is real but slow.

Some of the best materials candidates are ceramics and composites that don't have long supply chains or well-established manufacturing techniques. Getting a material from "works in the lab" to "reliable, cost-effective at commercial scale" takes years. Type One's engineering timeline must account for this maturation process.

This is where strategic investors like TDK become valuable. TDK is a materials science company. They have expertise in advanced ceramics, superconducting materials, and specialized alloys. Their investment in Type One isn't just capital. It's access to materials science expertise that could be crucial for solving the radiation damage problem.

Energy Return: The Metric That Actually Matters

Fusion's promise is energy return. You put in energy to heat plasma and maintain magnetic fields. The fusion reaction produces heat. You harvest that heat to boil water, spin turbines, generate electricity. The electricity powers the plant's systems. The excess electricity goes to the grid.

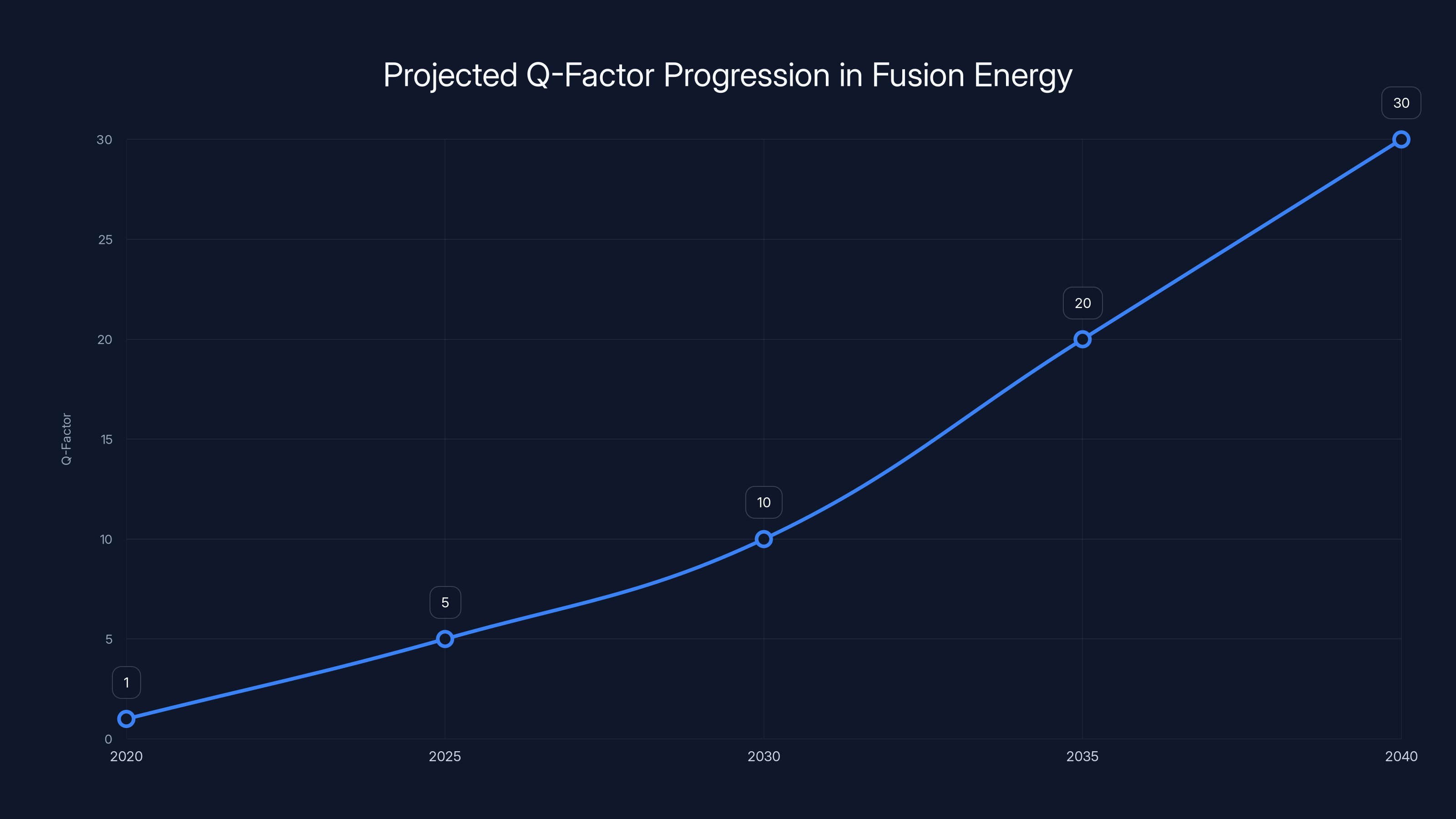

The critical metric is energy return on investment (EROI), often expressed as Q-factor: the ratio of fusion energy output to heating input. Q=1 means you get as much energy out as you put in (break-even). Q>1 means net energy gain. Q=10 means you get 10 times the energy out, which is more like what you need for a commercial power plant.

The National Ignition Facility achieved net energy gain (Q>1) in 2022. That was a historic breakthrough for physics. But NIB's EROI is misleading. The facility consumed vastly more electrical energy than the fusion reaction produced. The comparison is apples to oranges. NIB proved physics. It's not proof of commercial viability.

For a commercial fusion plant, you need Q values probably in the range of 20-50, accounting for thermodynamic efficiency of converting heat to electricity and the power required to operate the plant's systems. Magnetic confinement fusion reactors have achieved Q values in the range of 1-2 in recent experiments. That's progress, but it's a long way from 20.

Type One's success depends on achieving high Q values at commercial scale. That requires:

- High plasma temperature (more efficient fusion reactions)

- High plasma density (more reactions happening)

- Long confinement time (reactions continue long enough to generate net energy)

- High efficiency in the magnetic field (less power lost to maintain confinement)

Stellaerators have advantages in confinement time (continuous operation) but challenges in achieving high density at high temperature simultaneously. It's a scaling question: can you maintain the magnetic field geometry that provides natural stability while also achieving the plasma conditions needed for commercial fusion reactions?

This is precisely the engineering question that Type One's Series B funding is meant to answer. The $160+ million in venture capital is buying engineering, experiments, and iteration to prove that high-Q operation is achievable in a stellarator design.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Racing to Commercial Fusion?

Type One isn't alone in the fusion startup space. There are dozens of companies with different approaches, different funding levels, and different timelines. Understanding the competitive landscape helps contextualize Type One's positioning.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems is probably the highest-profile tokamak startup. They've raised over $1.8 billion in funding and are building SPARC, a tokamak demonstration reactor intended to achieve net energy. If SPARC succeeds on their timeline, they'll have proven tokamak viability years before Type One's stellarator. Commonwealth is the biggest potential competitor.

Helion Energy is pursuing inertial electrostatic confinement, a fundamentally different physics approach using ion beams instead of magnetic confinement. They've raised over $500 million and have partnerships with Open AI and other customers. Their approach is high-risk, high-reward.

TAE Technologies uses a different magnetic confinement approach (field-reversed configurations). They've pivoted multiple times and have struggled to raise funding at previous valuation levels, suggesting investor skepticism about their approach's scalability.

China's EAST project isn't a startup, but it's important context. China's national fusion program has maintained a tokamak facility and has achieved longer confinement times than most Western facilities. China's state-sponsored approach has advantages and disadvantages compared to venture-backed startups.

Type One's positioning relative to this landscape is interesting. They're not the best-funded tokamak startup (Commonwealth is). They're not pursuing the most exotic physics (Helion is). They're pursuing an engineering-heavy approach (stellarator design) with a proven customer (TVA) and a realistic timeline (mid-2030s). That's a different value proposition than most competitors.

Type One Energy's funding rounds show a steady increase, reflecting investor confidence and commitment to fusion technology. Estimated data.

The Supply Chain and Manufacturing Reality

Fusion reactor construction requires incredibly specialized components and manufacturing capabilities. This is often overlooked in venture capital discussions about fusion, but it's crucial.

Superconducting magnets are the core component. You can't buy them off-the-shelf from a catalog. They require custom design, specialized manufacturing facilities, and expertise from a limited number of global suppliers. Companies like Siemens, Southwire, and others have some capability, but scaling to produce the magnets needed for dozens of commercial fusion plants is a multi-year manufacturing ramp.

Cryogenic systems (the infrastructure that cools magnets to near absolute zero) are another specialized supply chain. There are suppliers, but again, scaling to commercial production is non-trivial.

Vacuum systems, neutron shielding, tritium breeding components, thermal transport systems—each piece of a commercial fusion plant requires specialized suppliers, many of which don't exist yet.

Type One's funding timeline must account for supplier development. You can't build 10 commercial fusion plants if you can only get magnet production for 1 plant per year. This is probably why Type One chose the asset-light model (licensing technology to utilities rather than building plants themselves). Utilities have the capital and the purchasing power to develop supplier relationships.

It's also why partnerships with companies like TDK and other industrial-scale manufacturers become valuable. They have supply chain experience, manufacturing expertise, and can help develop suppliers.

Regulatory and Licensing Challenges

Fusion power plants will be regulated. The question is how, and by whom. That regulatory framework doesn't fully exist yet, which creates both opportunity and risk.

Fission reactors are heavily regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in the United States and equivalent agencies worldwide. The regulatory process is slow, expensive, and conservative. A fusion startup hoping to operate a power plant on the same timeline as a fission plant is underestimating the regulatory challenge.

However, fusion has potential regulatory advantages over fission. Fusion reactors don't have the meltdown risk. They don't produce long-lived radioactive waste. The regulatory bar could potentially be lower. The NRC has expressed interest in developing fusion-specific regulatory frameworks, which is positive.

But here's the challenge: regulators will want to understand the technology thoroughly before licensing commercial operation. That means demonstrating safety through experimental facilities, providing detailed technical documentation, and likely undergoing extensive review. This process will take years.

Type One's timeline assumes regulatory approvals will be in place by the mid-2030s. That's optimistic but not impossible. The TVA's partnership suggests they're confident in the regulatory path. A utility wouldn't sign a contract with a startup if they believed regulatory approval was unlikely.

The international dimension also matters. Different countries are developing different regulatory approaches to fusion. Europe is more favorable to fusion than some other jurisdictions. China's state-sponsored approach faces different regulatory constraints. Type One could potentially operate facilities internationally if the US regulatory process becomes too burdensome.

The Path to Profitability: When Do Fusion Companies Make Money?

Here's a question that venture capitalists will eventually demand answers to: when does this start generating revenue that covers its costs?

For Type One, the business model is licensing technology to utilities, not generating electricity sales. That's clearer from a financial modeling perspective. If Type One licenses technology for 10 fusion plants over the next 20 years, generating licensing revenue, equity stakes in the utilities, and technology support fees, they could achieve profitability.

But the timeline is long. Commercial revenue probably doesn't start until Infinity Two is operational and generating electricity (and proving that the technology works). That's mid-2030s. That's a 10-year wait from now.

Venture capital typically expects returns within 5-7 years. Fusion is testing those expectations. Investors are betting on 10+ year horizons with the expectation of massive exit valuations (either IPO or acquisition).

Where's the exit? A fusion company could go public (unlikely before proving commercial operation). They could be acquired by a utility, an energy major, or a technology conglomerate (likely). They could remain independent and simply scale through licensing deals (possible but requires very successful execution).

Type One's investors are essentially betting that the company's technology will be valuable enough by 2035-2040 that someone (a utility, an energy major, or the public markets) will pay billions for ownership or licensing rights. That's a reasonable bet given the demand for clean power, but it requires successful technical execution.

Estimated data shows a projected increase in Q-factor values, aiming for commercial viability (Q=20-50) by 2040. Estimated data.

The Climate Impact: Why Fusion Matters (Or Doesn't)

Fusion's promise is decarbonization at scale. One 350-megawatt fusion plant avoids the carbon emissions of equivalent fossil fuel generation. But how much carbon are we talking about?

A coal plant of that size would generate approximately 2-3 million metric tons of CO2 annually (depending on coal source and plant efficiency). A natural gas plant would generate approximately 700,000-1,000,000 metric tons annually. A fusion plant would generate essentially zero.

But here's the climate math reality: the global power sector needs about 10 terawatts of new zero-carbon generation by 2050 to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. That's 10,000 gigawatts. Infinity Two is 0.35 gigawatts. Even if Type One scaled to build 100 plants, that's only 35 gigawatts. That's meaningful but not dominant.

Fusion's climate role is probably as a complement to renewables and energy efficiency, not as a complete replacement for all fossil fuel power generation. In some jurisdictions (like Europe or East Asia) with limited land for solar and wind, fusion could provide crucial baseload generation. In other jurisdictions with abundant land and wind resources, renewable energy plus storage might be more cost-effective.

Type One's value isn't "fusion will solve climate change." It's "fusion provides one viable path to decarbonized baseload power that utilities can deploy at scale." That's a real contribution, but it's not the silver-bullet narrative that fusion media coverage often implies.

The climate benefit also depends on the full lifecycle. Mining superconducting materials, manufacturing magnets, building the facility—all of that has carbon costs. The net climate benefit is the electricity generation benefit minus the lifecycle carbon costs. That's still positive, but less dramatic than raw zero-emissions power generation.

Future Funding and Scaling Questions

Type One's

But Type One needs capital to develop multiple reactor designs, to support multiple utility partners, to develop supply chains, to handle R&D and engineering. $160 million in venture capital, even with an eventual Series C, might not be sufficient.

This is where the asset-light model becomes essential. Type One isn't raising capital to build power plants. It's raising capital to develop technology. Utilities and energy companies are raising capital to build plants. That's a much more sustainable capital structure.

Future funding rounds will likely come from strategic partners (energy companies, utilities, industrial conglomerates interested in clean power) rather than pure venture capital. Once Type One proves commercial viability through Infinity Two, the capital markets will look very different.

There's also the question of how many fusion companies the market can support. If tokamaks prove superior to stellarators, stellarator startups will struggle to raise future funding. If stellarators prove superior, tokamak startups face pressure. The capital will flow toward winners.

Type One's position is interesting because they have customer validation (TVA contract) regardless of how the broader tokamak vs. stellarator competition resolves. That's their moat against competitive pressure.

The Risk Factors: Where Type One Could Fail

Let's be direct: fusion startups fail. Many have failed. The challenges are immense. Type One could fail for multiple reasons.

Technical risk: The stellarator approach might not achieve commercial-grade performance. The magnet engineering could prove harder than expected. The materials might not tolerate radiation as well as models predict. The plasma confinement might not scale from research facilities to commercial size. Any of these would invalidate the entire business model.

Timeline risk: The mid-2030s timeline for Infinity Two is ambitious. Any significant technical setback could delay by 5-10 years. If construction and approval take longer than expected, investors' patience could run out. Venture capital can be patient, but only so much.

Supply chain risk: Specialized components might not be available at the scale and cost Type One needs. Manufacturing partnerships might not develop as expected. Supply chain disruptions could delay progress.

Regulatory risk: If the NRC or other regulators impose stricter requirements than expected, costs and timelines could increase significantly. Fusion regulation is still evolving, creating uncertainty.

Competition risk: Tokamak competitors could prove faster to market or more cost-effective. If Commonwealth Fusion Systems' SPARC succeeds and operates commercially before Infinity Two, the capital and utility interest will shift to tokamaks. Type One's stellarator advantage would evaporate.

Customer risk: The TVA contract is valuable, but what if the TVA changes priorities? What if political or economic factors shift? A single customer provides focus but also creates concentration risk.

Capital risk: Fusion is capital-intensive. Type One might need more capital than the venture market is willing to provide. If the company can't raise Series C at acceptable terms, growth could stall.

These are real risks. Type One isn't a sure thing. But it's a sophisticated bet by serious investors on a specific technology path with a customer already committed. That's more de-risked than most fusion startups.

Broader Implications: What Type One's Success Would Mean

If Type One executes successfully—if Infinity Two generates 350 megawatts of reliable, zero-carbon power by the mid-2030s—it would validate stellarator fusion as a commercially viable path. That would trigger enormous capital flows.

Utilities worldwide would evaluate stellarator licenses. Energy companies would invest in stellarator technology. Other startups would pivot toward stellarators (or double down on tokamaks in response). The fusion landscape would shift fundamentally.

It would also validate the venture capital thesis that private companies can solve energy challenges that government-funded research programs have worked on for 50+ years. That would accelerate private investment in fusion and other energy technologies.

More pragmatically, it would provide US utilities with a domestic source of clean baseload power for data centers and industrial facilities. Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and other large consumers of electricity would have a path to achieve net-zero or carbon-negative operations. That's valuable.

Conversely, if Type One fails (whether due to technical setbacks, timeline delays, or competitive pressures), it would signal that stellarator fusion is too complex for commercial development. Capital would consolidate around tokamak startups or inertial confinement approaches. The fusion timeline would extend further into the future.

We won't know the outcome for a decade. But Type One's Series B and the TVA contract mean the question will be resolved empirically rather than theoretically. That's progress.

Conclusion: When Innovation Meets Infrastructure

Type One Energy's

Most technology breakthroughs follow a pattern: research proves the concept, companies commercialize it, capital scales it. Fusion has been stuck in the research phase for 50+ years. Type One's TVA contract suggests that might be changing.

The company's choice of stellarator technology is bold but defensible. It's an engineering challenge rather than a physics challenge. It enables continuous operation rather than pulsed operation. It's less glamorous than tokamak fusion, but potentially more practical for commercial power generation.

The funding level is substantial but not absurd. It reflects serious investor confidence without irrational exuberance. The investors—Breakthrough Energy Ventures, TDK, Doral—are strategically aligned with success. They're not financial investors making a speculative bet. They're industrial and strategic investors with deep expertise.

The timeline is ambitious (mid-2030s for Infinity Two) but not impossible. The customer is real (TVA), the contract is real, and the facility location is real (former Bull Run coal plant in Tennessee).

Will it work? That depends on execution, regulatory approval, supply chain development, and whether the engineering challenges are solved with the capital available. Fusion is genuinely hard.

But Type One has shifted the question from "Is fusion possible?" (solved by physics research decades ago) to "Can this team build a commercial fusion reactor on this timeline with this technology?" That's a question that venture capital can help answer through funding and execution support.

The bigger implications extend beyond Type One. If stellarator fusion works commercially, it validates private development of advanced energy infrastructure. It demonstrates that startups can solve problems government research programs have worked on for 50+ years. It shows that bold, audacious technical challenges can attract serious capital and talented teams.

Demand from data centers created the market opportunity. Technology maturity made the solution feasible. Capital aligned with mission, and a utility willing to take the risk completed the picture. That's how innovations become infrastructure.

Type One's success won't solve climate change single-handedly. But it would provide one credible path to gigawatt-scale, zero-carbon, baseload power within 10 years. In a world where electricity is becoming the limiting factor for AI deployment and economic growth, that's genuinely significant.

The next decade will answer the questions. In the meantime, the $160+ million invested in Type One Energy is buying us an expensive option on the future of fusion. Given the state of global power demand and carbon emissions, it might be one of the most important options on the table.

FAQ

What is Type One Energy's main technology innovation?

Type One Energy is developing stellarator magnetic confinement fusion reactors, which are different from the more common tokamak design. Stellarators use magnets arranged in a twisted, three-dimensional pattern that naturally confines plasma without requiring active feedback control. This design enables continuous operation rather than pulsed operation, which is theoretically more suitable for commercial power generation.

How much funding has Type One Energy raised to date?

Type One Energy has raised over

What is the Infinity Two project and what's its timeline?

Infinity Two is Type One Energy's first commercial power plant, being developed in partnership with the Tennessee Valley Authority. The facility will be built at the site of the former Bull Run coal-fired power plant in Tennessee and is designed to generate 350 megawatts of electricity. The target timeline for operational status is the mid-2030s, approximately 10 years from now.

How is Type One Energy's business model different from other fusion startups?

Unlike most fusion startups that plan to build and operate power plants themselves, Type One Energy will sell its technology and designs to utilities like the TVA, who will build and operate the plants. This asset-light model reduces capital requirements and operational risk for Type One while allowing utilities to take ownership of the infrastructure investment and long-term returns.

Why would utilities choose fusion over renewable energy or natural gas?

Utilities are facing rapidly growing electricity demand from data centers and AI systems that require reliable, baseload (24/7) power. Solar and wind are intermittent and don't provide reliable baseload power without expensive battery storage. Natural gas provides baseload power but has carbon emissions and supply chain vulnerabilities. Fusion offers zero-carbon, baseload power with smaller physical footprint than solar or wind, making it attractive for regions with limited available land.

How does Type One Energy's technology compare to Commonwealth Fusion Systems' tokamak approach?

Type One's stellarators and Commonwealth's tokamaks represent different engineering trade-offs. Stellarators provide naturally stable plasma and continuous operation capability but require more complex magnet engineering. Tokamaks are mechanically simpler but require active feedback control to maintain plasma stability and typically operate in pulses. Both approaches have been proven in research facilities, but neither has yet demonstrated commercial-scale power generation. Commonwealth is likely to reach commercial operation first, while Type One targets the mid-2030s.

What materials science challenges must fusion reactors overcome?

Fusion reactors must withstand intense neutron radiation from fusion reactions that gradually damages reactor materials, making them brittle and weak over time. Reactors need special alloys and ceramics that can tolerate these extreme conditions for 30+ years of operation. This materials science challenge is one of the most significant engineering obstacles in fusion development and requires specialized research and manufacturing partnerships.

What are the regulatory challenges for commercial fusion power plants?

Fusion power plants will require licensing and oversight from regulators like the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), but fusion-specific regulatory frameworks are still being developed. Fusion has potential regulatory advantages over fission because it doesn't pose meltdown risk and doesn't produce long-lived radioactive waste, but regulators will require extensive safety documentation and testing before licensing commercial operation. Type One's TVA contract suggests confidence that regulatory approval will be achievable by the mid-2030s.

How does fusion power compare to renewable energy in terms of cost and carbon footprint?

Fusion's cost per megawatt is likely to be higher than solar or wind but is expected to be competitive with nuclear fission and natural gas once manufacturing scales up. Carbon footprint analysis must account for the manufacturing and materials production required to build fusion reactors, but operational carbon emissions from fusion are essentially zero. The full lifecycle carbon analysis shows fusion as significantly cleaner than fossil fuels and competitive with renewables when accounting for grid stability and baseload capability.

What happens if Type One Energy's stellarator approach proves inferior to tokamak technology?

If tokamak technology achieves commercial success faster or more cost-effectively than stellarators, venture capital and utility interest would likely shift toward tokamak startups like Commonwealth Fusion Systems. Type One would face difficulty raising future capital and potentially scaling their technology. However, Type One's existing TVA partnership provides some insulation because utilities might pursue multiple fusion technology paths to diversify their clean energy portfolio.

Key Takeaways

- Type One Energy raised 250M Series B at160+M, signaling serious investor confidence in stellarator fusion technology

- The company secured a binding contract with Tennessee Valley Authority to build Infinity Two, a 350-megawatt fusion plant by mid-2030s, validating customer demand beyond venture speculation

- Stellarators offer theoretically superior continuous operation capability compared to tokamaks' pulsed approach, though more complex magnet engineering creates different engineering trade-offs

- Data center electricity demand is projected to triple by 2035, creating urgent customer demand for clean baseload power that Type One's technology is positioned to address

- Type One's asset-light business model licensing technology to utilities differs strategically from competitors, reducing capital requirements and distributing risk more effectively

Related Articles

- Offshore Wind Developers Sue Trump: $25B Legal Showdown [2025]

- Microsoft's Community-First Data Centers: Who Really Pays for AI Infrastructure [2025]

- SkyFi's $12.7M Funding: Satellite Imagery as a Service [2025]

- Over 100 New Tech Unicorns in 2025: The Complete List [2025]

- Harmattan AI Defense Unicorn: $200M Series B, Dassault Aviation [2025]

- SandboxAQ Executive Lawsuit: Inside the Extortion Claims & Allegations [2025]

![Type One Energy Raises $87M: Inside the Stellarator Revolution [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/type-one-energy-raises-87m-inside-the-stellarator-revolution/image-1-1768410865021.jpg)