The Chevy Bolt EV Is Dying Before It Really Had a Chance

General Motors just killed off one of the most promising affordable electric vehicles in America. The 2027 Chevy Bolt EV, which hit dealerships in early 2026, will be discontinued in roughly 18 months. That's right. The car that was supposed to democratize EV ownership, priced at just $29,990 including destination fees, is getting the axe before most people even knew it existed.

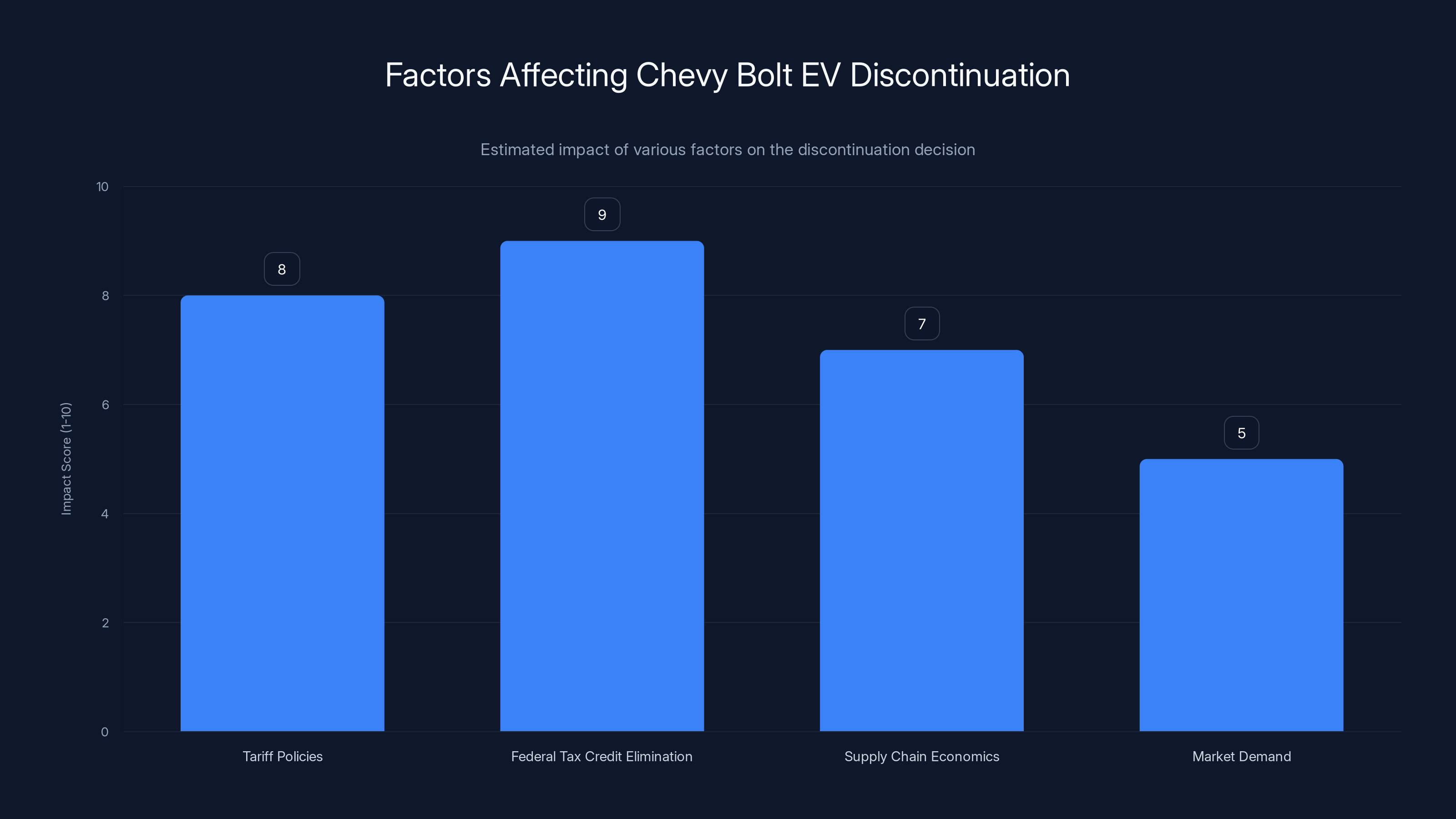

This isn't some slow fade-out. This is a hard stop driven by forces way bigger than General Motors' ability to control. The real story here isn't about the Bolt itself. It's about how tariff policy, federal tax credit elimination, and global supply chain economics are reshaping American automotive manufacturing in real time.

When GM announced the rebooted Bolt in October 2025, executives framed it as a "limited run model." That qualifier mattered. They knew the window was closing. They knew the political and economic environment was shifting beneath their feet. What they didn't anticipate was how quickly those shifts would accelerate.

The Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas, where the Bolt is currently built, won't sit idle for long. By mid-2027, the gas-powered Chevrolet Equinox will move production there from Mexico. Then in 2028, the next-generation Buick Envision, currently manufactured in China, will take over the facility. It's a carefully choreographed factory musical chairs that reveals the hidden calculus of modern automotive economics.

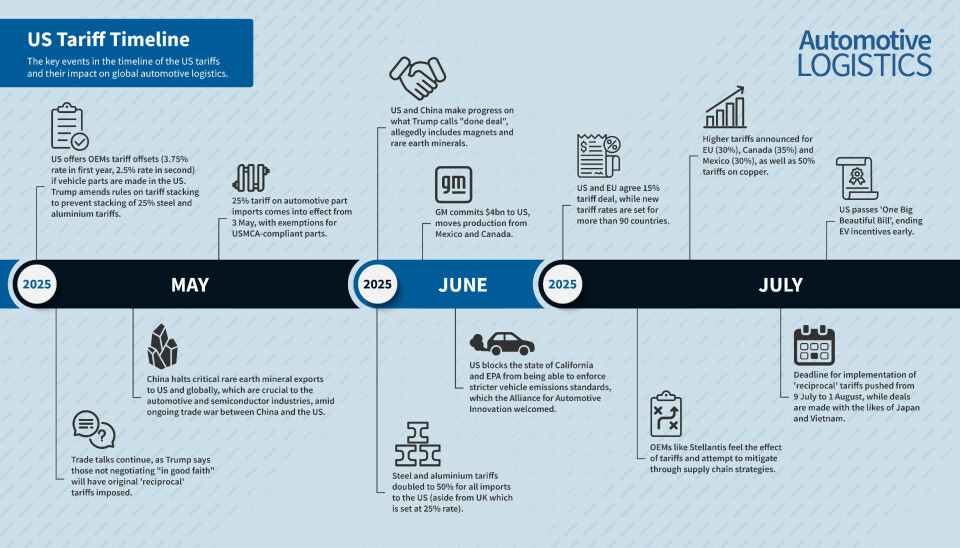

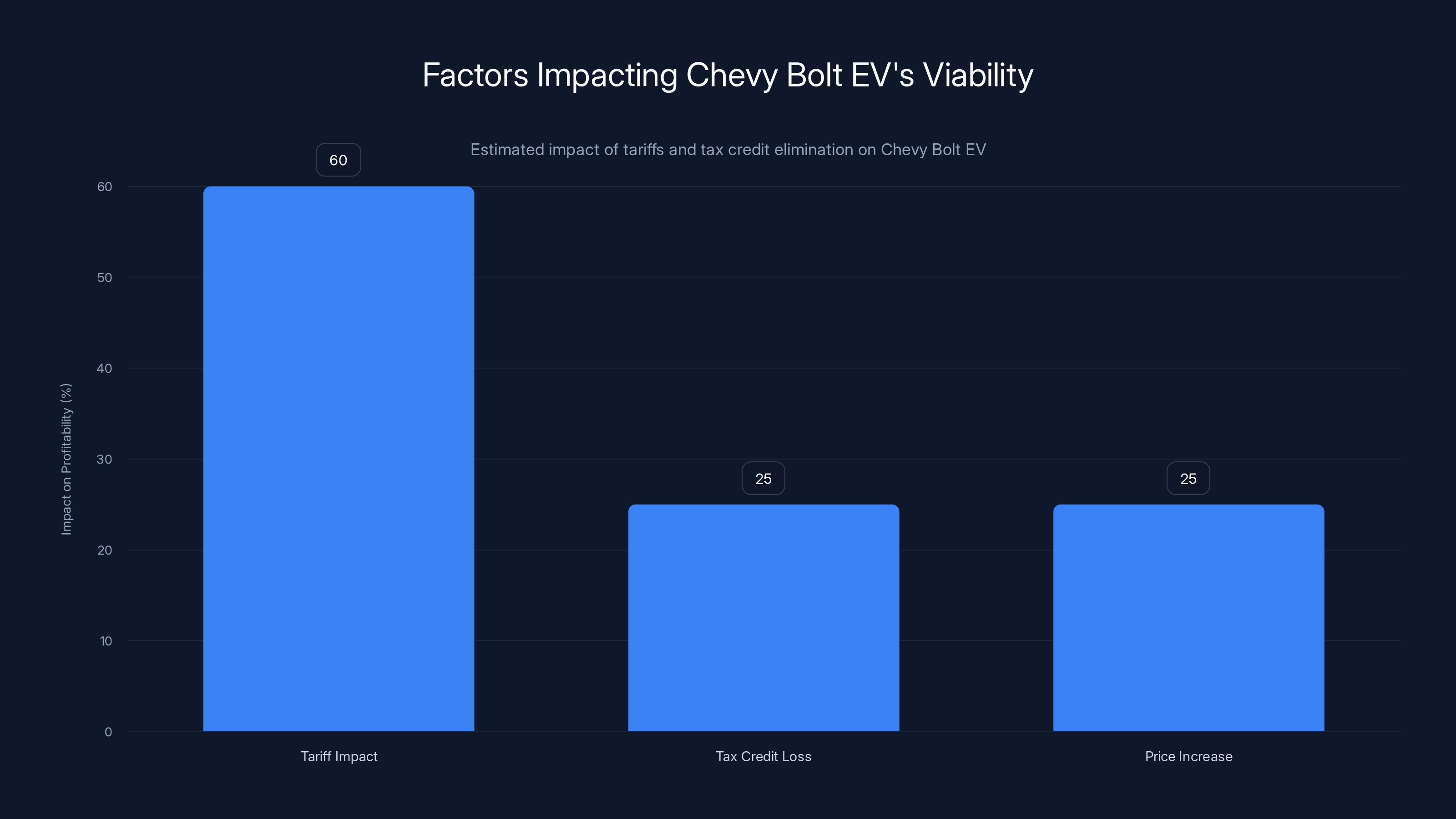

Here's what's actually happening behind the scenes: the Trump administration's tariff policies and the decision to eliminate the federal EV tax credit have fundamentally altered the math for building affordable EVs. Suddenly, the advantages that made China and Mexico attractive manufacturing hubs have evaporated. Labor costs don't matter if you're paying 25% tariffs on Chinese goods or 60% tariffs on Mexican imports. The $7,500 federal tax credit that made affordable EVs competitive with gas cars is gone. That single policy change erases a massive chunk of the Bolt's value proposition.

GM's decision reflects a brutal reality: the Chevy Bolt EV was always fighting against time. Its window of profitability was always narrow. Remove the tax credit. Add tariffs. Watch the margins disappear. The Bolt becomes economically unsustainable at $29,990. Either GM raises prices and loses the value proposition, or they eat the losses. Neither option is viable long-term.

The real question now is whether GM will change course if Bolt sales exceed expectations. That's possible, but unlikely. The factory is already spoken for. The production ramp is already scheduled. And GM has been pretty clear: the Bolt was always meant to be a bridge product, not a permanent fixture in their EV lineup.

But for consumers looking for an affordable EV right now? The Chevy Bolt EV represents a rare window of opportunity. Because once it's gone, there won't be another affordable option quite like it in the American market for several years.

Understanding the Political and Economic Earthquake

The story of the Chevy Bolt's demise starts with policy changes that have nothing directly to do with Chevrolet, General Motors, or even the automotive industry specifically. It starts with tariffs.

When the Trump administration took office in January 2025, tariff policy became a central economic lever. The rationale was straightforward: protect American manufacturing by making imports more expensive. For the automotive industry, the implications were immediate and brutal. Chinese goods faced tariffs as high as 60%. Mexican imports faced 25% tariffs. Suddenly, the cost advantages that made building cars in those countries attractive for the American market evaporated overnight.

The Chevy Bolt EV existed in a specific economic context. It was designed to be built in Kansas, but the new Bolt platform leveraged some Chinese battery technology and components. That's not unusual in modern automotive manufacturing. Supply chains are global. A single car contains parts from dozens of countries. But tariffs don't care about supply chain complexity. They just make everything from outside the US more expensive.

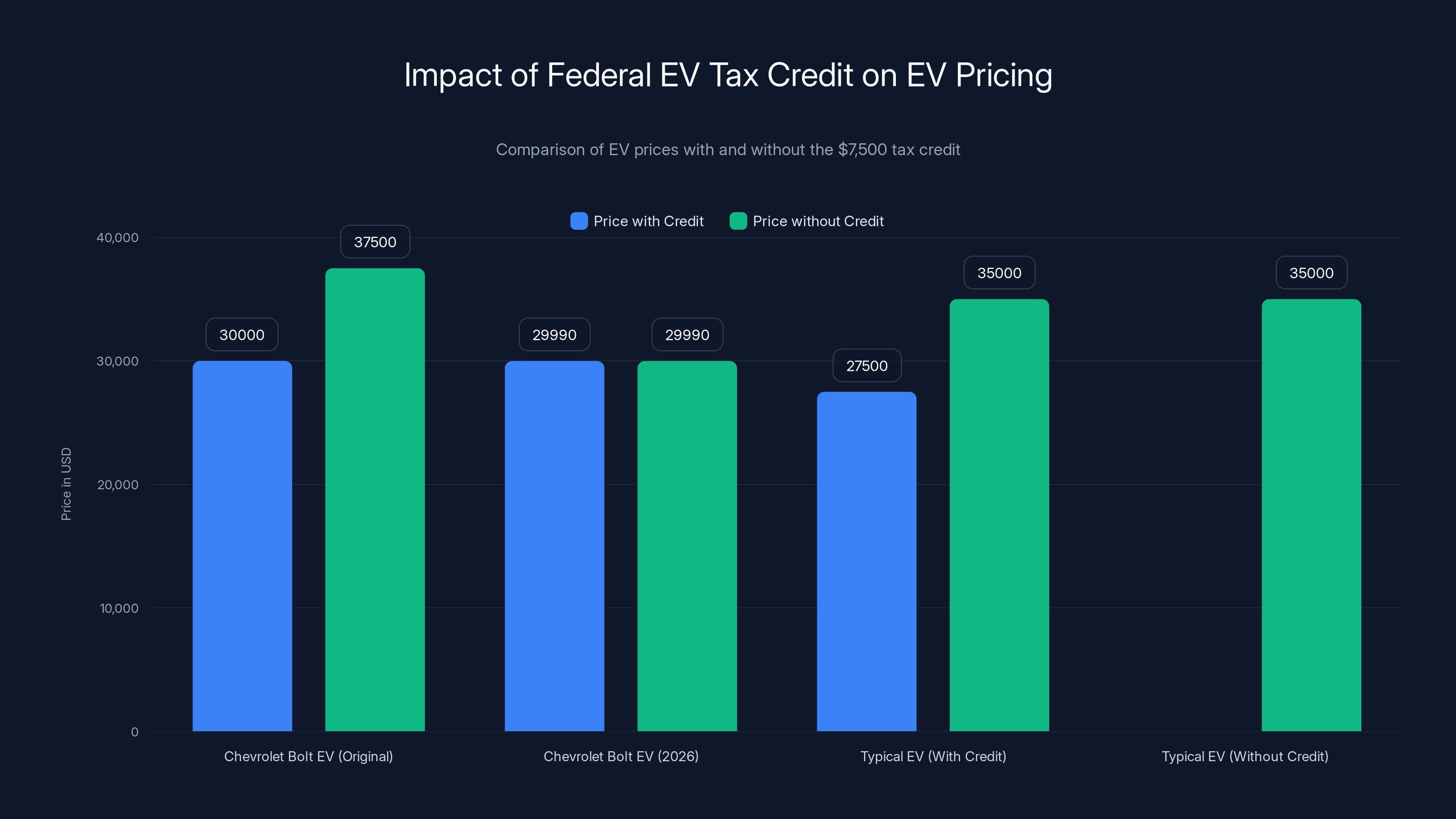

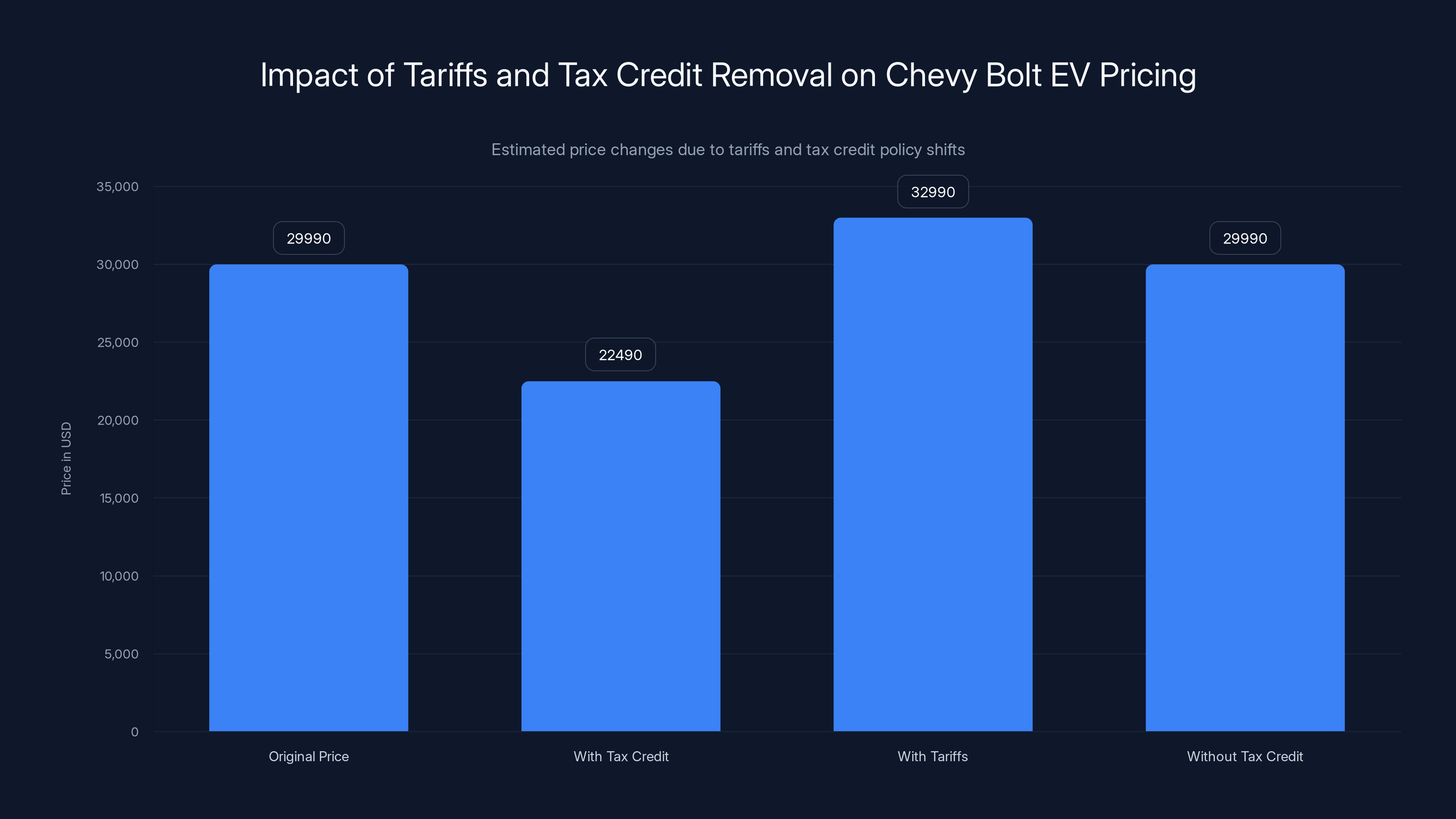

At the same time, the federal EV tax credit was eliminated. This wasn't a minor policy tweak. The credit was worth up to

Consider the math: a buyer looking at a

Without the tax credit, that same buyer is looking at

This is where the economic reality becomes clear. GM can't sustain the Bolt at the price point that made it special without the tax credit and without the tariff environment that existed a year ago. The margins don't work. The vehicle economics don't pencil out.

But there's another layer to this story: manufacturing geography. By moving production from China and Mexico to Kansas, GM is responding to the tariff environment. The Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas can build vehicles for the American market without worrying about tariffs on imports. It's more expensive to build in the US than in Mexico or China. But with tariffs, it's more cost-effective.

The Buick Envision, currently built in China, will move to Kansas in 2028. The gas-powered Chevrolet Equinox will move from Mexico in 2027. These aren't random decisions. These are strategic responses to a tariff-driven world where US manufacturing suddenly makes economic sense again.

For GM, the message is clear: if you want to sell into the American market profitably, build it in America. The tariff structure has changed the entire calculus of global automotive supply chains.

The $7,500 federal EV tax credit significantly reduced the effective purchase price of electric vehicles, making them more competitive with traditional gas cars. With the credit's removal, EVs face a higher price barrier.

Why the Chevy Bolt EV Was Always Vulnerable

The 2027 Chevy Bolt EV was never positioned as a permanent product. From the moment GM announced its return, insiders understood this was a limited-run vehicle. The question wasn't whether it would survive. The question was whether it would last long enough to serve its strategic purpose.

That strategic purpose was important: to have an affordable EV option in the American market while the rest of GM's EV portfolio came online. The company was investing billions in EV platforms and new vehicles. The Bolt, utilizing an older but proven architecture, provided a bridging solution.

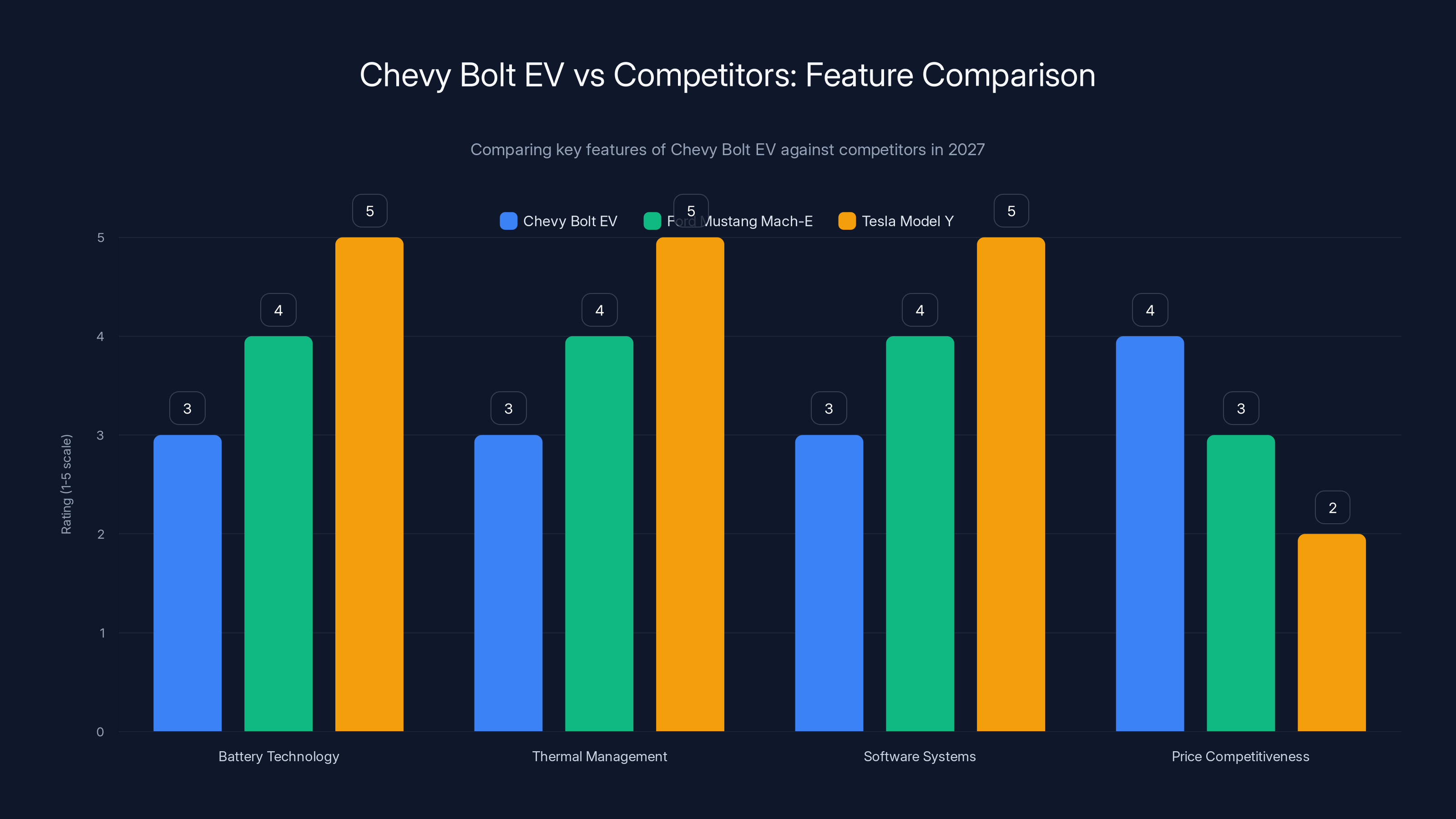

But the Bolt was always fighting structural headwinds. First, it was built on an older platform. Modern EV architecture features newer battery technology, better thermal management, and integrated software systems. The Bolt's platform, while reliable and proven, didn't compete on features or technology with newer vehicles like the Ford Mustang Mach-E or Tesla Model Y.

Second, GM had positioned the Bolt as an affordable entry point, not as a premium or aspirational vehicle. That's a tough market. Consumers shopping at $30,000 are price-sensitive and often skeptical of EV technology. They're not enthusiasts. They're practical buyers trying to reduce their transportation costs. That means the vehicle needs to deliver exceptional reliability and value. It needs to have a proven track record.

The original Bolt EV had that track record. It debuted in 2016 and built a reputation for reliability and practical EV ownership. But GM discontinued it in 2023 to retool the factory for next-generation platforms. When it returned in 2026, the market had shifted. New competitors had emerged. Tesla had dropped prices. Used EVs were becoming available. The Bolt's competitive position had weakened.

Third, the Bolt was never going to be a high-margin vehicle. At

Finally, there's the factory constraint. The Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas has limited capacity. GM always knew it would eventually transition this facility to other products. The Bolt was a temporary tenant. The real production capacity was being prepared for vehicles with better margins and clearer strategic value.

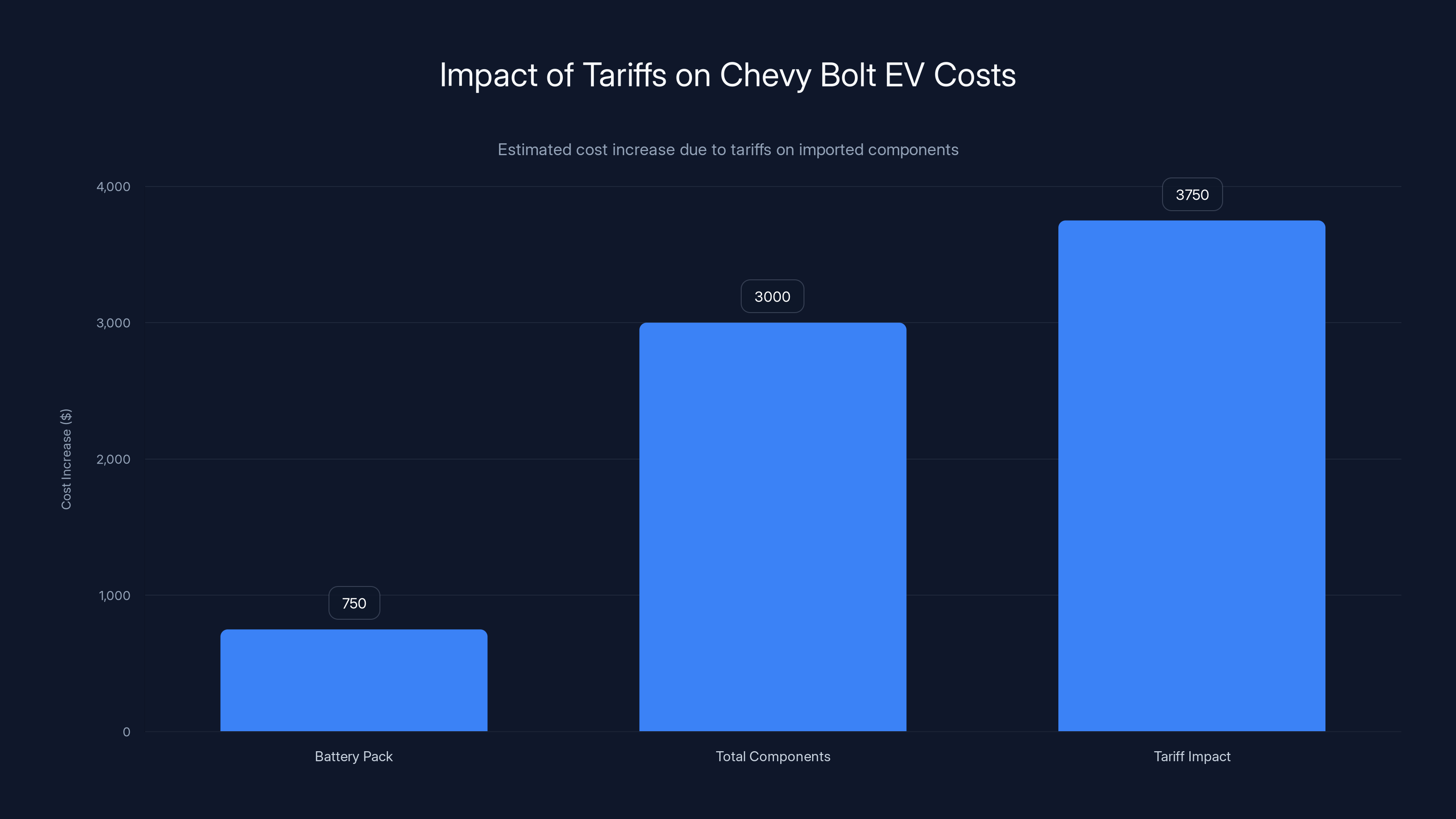

Tariffs and the elimination of the federal EV tax credit significantly impacted the Chevy Bolt EV's profitability, with tariffs contributing up to 60% of the cost increase. Estimated data.

The Tariff Factor: How Trade Policy Killed the Affordable EV

Tariffs are the invisible hand steering the Chevy Bolt EV toward extinction. They're also reshaping the entire American automotive industry.

The Trump administration imposed tariffs for multiple reasons: to protect domestic manufacturing, to create leverage in trade negotiations with China, to address trade imbalances, and to signal that US manufacturing matters. From a political perspective, tariffs are tools of economic policy. From an automotive industry perspective, tariffs are threats to profitability.

Consider what a 25% tariff means for a vehicle with Chinese components. If a battery pack costs

For the Chevy Bolt EV at a $29,990 price point, there's no room to absorb those costs. Consumers at that price point will simply buy something else. Pass the costs to the consumer, and the vehicle becomes less competitive. Lower margins, and the vehicle becomes unprofitable at that volume.

This is precisely the bind that killed the Bolt. The vehicle was economically viable in a zero-tariff, EV-tax-credit environment. Remove both of those conditions, and viability disappears.

But there's a strategic flip side: tariffs make US manufacturing more competitive. Building in Kansas is more expensive than building in Mexico or China. But the tariff structure eliminates that cost advantage for foreign production. Suddenly, US manufacturing becomes cost-competitive again.

This explains GM's facility strategy. The gas-powered Chevrolet Equinox currently built in Mexico will move to Kansas in mid-2027 because US manufacturing is now cost-competitive despite higher labor costs. The Buick Envision will move from China to Kansas in 2028 for the same reason. The tariff structure has fundamentally changed the economics of where vehicles should be built.

For the Bolt specifically, this creates a paradox. The vehicle needs to be built in the US for tariff purposes. But the Kansas factory is now slated for higher-margin products like the gas Equinox and the Buick Envision. The Bolt, with its thin margins, doesn't fit the facility's new strategic purpose.

This is industrial logic at work. Factories cost billions to operate. Every hour of downtime costs millions. Every product that runs through that facility needs to justify its space. The Bolt justified that space when it was the only product available. As other vehicles come online, the Bolt becomes expendable.

The Death of the Federal EV Tax Credit and Its Consequences

The federal EV tax credit wasn't just a nice perk. It was the financial foundation upon which affordable EV economics were built.

For nearly a decade, the $7,500 tax credit stood as one of the most important incentives in American environmental policy. It made EV ownership financially accessible to middle-class families. It gave manufacturers like Tesla and Chevrolet a reason to build affordable vehicles. It aligned financial incentives with environmental goals.

The credit worked in a deceptively simple way: buyers who purchased a qualifying EV could claim $7,500 on their federal tax return. Some manufacturers rebated this directly at the point of sale, making the math visible to consumers. Others required buyers to claim it at tax time. Either way, the effect was the same: it reduced the effective purchase price of an EV by a meaningful amount.

For the original Chevrolet Bolt EV, this credit was transformative. At

When the new Bolt returned in 2026 at

The loss of the credit had cascading consequences across the EV market. Suddenly, vehicles that were competitively priced with gas alternatives became significantly more expensive. A

For manufacturers building affordable EVs, the consequences were brutal. The margin structure that worked with the credit didn't work without it. Either raise prices and lose customers, or absorb the lost value and destroy profitability.

GM chose a different path: discontinue the Bolt and shift manufacturing capacity to vehicles with healthier margins. It's a rational economic decision, even if it's disappointing for consumers who wanted affordable EV access.

But here's the longer-term implication: without the tax credit and with tariff policies in place, the market for affordable EVs in America shrinks. Manufacturers focus on higher-margin vehicles. Tesla dominates the volume EV market with better technology and brand strength. Legacy automakers retreat to higher-priced segments. The democratization of EV ownership stalls.

This isn't unique to the Bolt. It's an industry-wide consequence of the policy changes. Multiple affordable EV programs have been quietly shelved or significantly reduced as manufacturers recalibrate their strategies.

The discontinuation of the Chevy Bolt EV is heavily influenced by tariff policies and the elimination of federal tax credits, with supply chain economics also playing a significant role. Estimated data.

GM's Factory Musical Chairs: A Strategy Response

The simultaneous announcement of the Bolt's discontinuation and the news about the Equinox and Envision moving to Kansas isn't coincidental. It's a choreographed strategy move that reveals how GM is adapting to the new political and economic environment.

Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas is GM's facility for rebirth. It's where the company committed to building its next generation of affordable vehicles. By 2028, the facility will be home to three major products: the Equinox (moving from Mexico in mid-2027), the Buick Envision (moving from China in 2028), and eventually additional products from GM's affordable EV roadmap.

The strategic logic is clear: consolidate US manufacturing, eliminate tariff exposure on imports, and prepare the facility for the next wave of vehicle development. The Bolt was a placeholder, a temporary occupant of valuable factory space.

But this strategy reveals something important about modern automotive economics. It's not just about building cars anymore. It's about where those cars are built, what supply chains look like, and how tariff policy reshapes profitability.

The move of the gas-powered Equinox from San Luis Potosí, Mexico to Kansas is particularly telling. GM is deliberately shifting production of an ICE vehicle from Mexico to the US. This makes economic sense in a high-tariff environment, even though labor costs are significantly higher in Kansas. It also signals confidence that the American market will continue to demand gas-powered vehicles for years to come.

The move of the Buick Envision from China to Kansas is equally significant. The Envision is a compact crossover with healthy margins. It's sold globally but will now be built for the North American market from a US facility. This protects against Chinese tariffs, ensures supply chain security, and keeps production capacity domestic.

For GM as a company, this strategy makes sense. For consumers, it's more complicated. The Bolt disappears, replaced by higher-priced vehicles with better margins. The affordable EV option vanishes. Consumers shopping for value have fewer choices.

The factory transitions also suggest something about GM's EV roadmap. The company promised to make new investments in Fairfax for next-generation affordable EVs. But the timeline is vague. "We just don't know when," as one industry observer noted. This could mean next year. It could mean 2029. The uncertainty itself is telling. GM isn't rushing to bring the next affordable EV to market.

The Broader Context: How American Auto Policy Is Reshaping Industrial Strategy

The Chevy Bolt EV's demise is a symptom of a much larger transformation in American automotive policy and industrial strategy.

For decades, the US automotive industry operated under one set of assumptions: global supply chains were efficient, tariffs were minimized through trade agreements, and manufacturing followed economic logic. Countries with lower labor costs attracted manufacturing. Component suppliers spread across continents to minimize costs. The goal was simple: maximize profit through global optimization.

That era is ending. It's not over yet, but the trajectory is clear. The new policy environment prioritizes onshoring, manufacturing security, and trade protectionism. The goal is no longer pure profit optimization. It's domestic manufacturing capacity, supply chain independence, and what policymakers call "manufacturing resilience."

Tariff policy is the primary lever. By making imports expensive, tariffs mathematically encourage domestic production. A 25% tariff on Mexican goods means building in the US suddenly makes economic sense, even if US labor costs are 50% higher. That's a fundamental shift in the economic calculus.

This policy shift has multiple motivations: job creation in politically important manufacturing regions, supply chain independence (especially regarding Chinese technology), and economic nationalism. But the consequences are significant. They reshape where vehicles are built, what they cost, and which models are viable.

For the Chevy Bolt EV, this context is crucial. The vehicle was always going to struggle in a world with both high tariffs and no EV tax credit. The math simply doesn't work. But the Bolt also represents a policy casualty. It's a victim of the shift from EV incentives to EV taxation.

Looking forward, expect more policy-driven disruption in the auto industry. The tariff structure will likely continue to shift as negotiations change. EV policy may evolve if a future administration returns to supporting EVs through incentives. Supply chain strategies will continue to adapt. And manufacturers will keep making hard choices about which products are viable in which political contexts.

The Bolt's story is ultimately a story about how policy creates economic conditions that determine which products live and which die. It's a reminder that automotive manufacturing isn't just about engineering and efficiency. It's about policy, politics, and the ability to operate profitably within a given regulatory and trade environment.

The removal of the $7,500 tax credit significantly increased the effective price of the Chevy Bolt EV, while tariffs on components further raised costs. Estimated data.

What This Means for EV Consumers Right Now

The Chevy Bolt EV's discontinuation has immediate and practical implications for people shopping for electric vehicles.

First, it signals that affordable EV options are shrinking. The market for sub-$30,000 EVs was already limited. The Bolt was essentially alone in that category. With the Bolt disappearing, there won't be a clear replacement for several years. The gap between ultra-cheap gas cars and genuinely affordable EVs is widening.

Second, it suggests that other affordable EV programs may face similar pressure. If GM couldn't make the economics work on the Bolt, other manufacturers with similar products are facing identical pressures. Expect more discontinuations and fewer launch announcements in the affordable EV segment.

Third, it creates a temporary window of opportunity for Bolt buyers. The 2027 model year is the last production year. Once inventory runs out, these vehicles will be gone. For consumers who want a proven, reliable, affordable EV, the Bolt represents a rare option. Waiting for the next generation of affordable EVs could mean waiting years.

Fourth, it highlights the importance of the tax credit for EV economics. Many consumers relied on the $7,500 credit to make EV ownership work financially. Without it, the effective price of EVs has jumped significantly. This will likely slow EV adoption among price-sensitive buyers.

Fifth, it suggests that the EV market is stratifying. You'll have expensive, cutting-edge EVs from Tesla and legacy manufacturers at $40,000+. You'll have used EVs from earlier generations. And you'll have a growing gap in the middle market where affordable new EVs used to live. That gap is bad for consumers shopping on a budget.

For anyone considering EV ownership right now, the advice is straightforward: don't wait. The Chevy Bolt EV is one of the last affordable options. Inventory will tighten. Deals will disappear. And the next generation of affordable EVs is still years away.

The Investment Paradox: Why GM Is Pulling Back on Affordable EVs

GM's decision to discontinue the Bolt while promising future investments in affordable EVs reveals a corporate paradox that's worth examining.

On one hand, GM is pulling the plug on one of its only affordable EV products. The company is freeing up factory capacity, shifting to higher-margin vehicles, and essentially retreating from the ultra-affordable EV market. That looks like a retreat from electrification.

On the other hand, GM is promising to make new investments in Fairfax Assembly for next-generation affordable EVs. The company is committed to bringing more affordable electric vehicles to market. That sounds like a commitment to electrification.

Both statements are true. The resolution is in the timeline. The Bolt is discontinued now, in 2027. Future affordable EVs from GM are coming at some unspecified point, potentially years away. The gap between discontinuation and the next affordable model is the real story.

Why create that gap? Partly because the current economic environment doesn't support affordable EV profitability. Partly because GM needs Fairfax to produce higher-margin vehicles while next-generation platforms are being developed. Partly because the company is betting that tariffs and policy will eventually stabilize or change, creating better conditions for affordable EV production.

But there's another dynamic at play. EV adoption has slowed. After years of explosive growth, EV market penetration is flattening. Consumers who wanted to buy EVs have bought them. The marginal buyer is more price-sensitive, less enthusiastic about EV ownership, and less willing to accept the practical trade-offs that EV ownership currently requires.

In this context, a low-margin vehicle like the Bolt becomes particularly vulnerable. It's fighting for market share in a market that's becoming more challenging. The economics don't work. The margins don't exist. The vehicle becomes a net drain on corporate resources.

GM's strategy is to wait out this market inflection point. Invest in next-generation platforms with better technology, better margins, and better competitive positioning. Produce the Equinox and Envision in Kansas, where margins are healthy. And eventually, when the time is right, bring affordable EVs back to market with better platforms and better profitability.

This strategy is rational from a corporate perspective. It's less great for consumers who want to buy affordable EVs right now.

Estimated data shows a $3,750 increase in costs for Chevy Bolt EV due to tariffs on imported components, impacting its affordability.

Comparing GM's Strategy to Competitors: Who's Actually Investing in Affordable EVs?

GM's retreat from affordable EVs isn't happening in isolation. Competitors are making similar moves, but with different emphases.

Tesla, the market leader in EVs, has deliberately positioned itself away from ultra-affordable vehicles. The company targets the

Ford discontinued its Focus EV and eliminated several lower-priced electric options. The company is focusing on electric trucks and SUVs, which have better margins and stronger demand. Ford's future EV strategy is volume-focused on higher-priced vehicles.

Volkswagen had plans for affordable EVs, but those plans have been repeatedly delayed and scaled back. The company originally promised to build a sub-$20,000 EV. That timeline has slipped multiple times. The project is now positioned for 2027 or later, with reduced volume expectations.

Hyundai and Kia have been more aggressive in the affordable EV segment than most legacy competitors. These companies understand that EV adoption requires affordability. But even they are seeing margin pressure. The Hyundai Kona Electric, which debuted as an affordable option, has seen prices creep upward with each generation.

China's EV manufacturers are the real story in affordable EVs. Companies like BYD, Nio, and others have flooded the Chinese market with affordable electric vehicles. These vehicles are not available in the US due to tariffs and import restrictions, but they demonstrate that affordable EV manufacturing is possible at scale. The problem isn't technology. The problem is that US tariff policy and the loss of the EV tax credit have made affordability economically irrational for US manufacturers.

The broader pattern is clear: when you remove tax incentives and add tariffs, affordable vehicles disappear from manufacturer roadmaps. The profit incentive collapses. Manufacturers focus on vehicles with healthier margins. The market stratifies. Access to affordable EVs becomes limited.

GM's decision on the Bolt isn't unique. It's representative of an industry-wide shift driven by policy changes.

The Kansas Factory: From Workforce Hub to Strategic Asset

The Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas is more than just a factory. It's a workforce hub, an economic engine for the region, and now a strategic asset in GM's response to new tariff policies.

The facility employs thousands of workers. It's one of the major manufacturing operations in Kansas. When GM announced that it would produce the rebooted Chevy Bolt EV there, it signaled commitment to the region. When the company now announces that it will discontinue the Bolt and shift production of other vehicles to the facility, it's sending a different message: the plant's role is changing.

From a workforce perspective, the transition is significant. The Bolt represented lower-complexity manufacturing than vehicles like the Equinox or Envision. The EV platform required different skill sets and production processes. The shift to gas-powered vehicles and different EV platforms will require worker retraining and adjustment.

But from a corporate perspective, the shift makes sense. The facility is being repositioned as a hub for US-manufactured vehicles destined for the North American market. That's a more strategic role than building a single lower-margin product. It positions Fairfax as a core facility in GM's North American manufacturing footprint.

The workers at Fairfax, represented by the UAW union, have been negotiating labor agreements that reflect EV transition considerations. The shift in production mix creates both challenges and opportunities. Challenges because products change and worker roles change. Opportunities because the facility will be busier and more strategically important to GM's overall operations.

Long-term, Fairfax's role depends on future product decisions. If GM brings next-generation affordable EVs to the facility as promised, the plant's mission expands. If those affordable EVs are delayed or scaled back, the facility risks becoming a single-product dependency, which is always vulnerable to market shifts.

The facility's story is ultimately a microcosm of the broader industry challenge: adapting manufacturing operations to new economic and policy realities. It's expensive. It's disruptive. But it's also necessary if manufacturers want to remain profitable and competitive.

The Chevy Bolt EV, while affordable, lags behind competitors like the Ford Mustang Mach-E and Tesla Model Y in terms of battery technology, thermal management, and software systems. Estimated data.

Timeline and What to Expect: The Transition Roadmap

Understanding the transition timeline helps clarify what's coming and when.

Now through mid-2027: Chevy Bolt EV production continues. GM hasn't announced a specific end date, but "about a year and a half" from early 2026 suggests the transition will happen around mid-2027. During this period, Bolt inventory will gradually decrease as production winds down. Dealers will likely become more aggressive with pricing as they clear inventory before the vehicle is discontinued.

Mid-2027: Gas-powered Chevy Equinox moves from Mexico to Kansas. The Equinox transition marks the first major production shift at Fairfax. This is when the factory's role shifts from single-product (Bolt) to multi-product manufacturing. The Equinox, a gas-powered crossover, represents higher margins and stronger demand than the Bolt.

2028: Buick Envision moves from China to Kansas. The Envision transition happens about a year after the Equinox move. By this point, Fairfax will be running at higher utilization with two major products on the same assembly line. This is when the facility becomes a truly strategic hub in GM's North American manufacturing footprint.

2029 and beyond: Timing for next-generation affordable EVs uncertain. GM has promised future investments in affordable EVs at Fairfax, but the timeline is undefined. This could mean 2029, 2030, or later. The vagueness suggests that next-generation affordable EV development is still in progress and the market conditions for launching such vehicles remain uncertain.

This timeline reveals the transition strategy clearly: discontinue the Bolt, shift to higher-margin vehicles, and buy time for next-generation affordable EV platforms to reach production readiness.

Policy Implications: The Question of US EV Leadership

The story of the Chevy Bolt EV's discontinuation raises important questions about US policy and EV leadership.

A decade ago, the US was leading the world in EV adoption and development. The federal tax credit was seen as a global best practice. Tesla was a darling of the startup world. Legacy manufacturers were investing billions in EV technology. The trajectory seemed clear: the US would lead the world in EVs.

That narrative has changed. EV adoption has plateaued in the US. China has become the dominant EV manufacturer globally. The federal tax credit has been eliminated. And manufacturers are scaling back affordable EV programs.

This isn't accidental. It's the result of specific policy choices. Removing the tax credit eliminated the financial incentive for manufacturers to build affordable EVs. Implementing tariffs created cost pressures that made affordable EV economics unsustainable. The policy environment shifted from EV incentives to EV pragmatism.

From a certain perspective, this makes sense. The EV market has matured. Early adopters have bought their vehicles. Tariff policy is being used to protect domestic manufacturing. The need for government subsidies is arguably reduced.

From another perspective, it signals a retreat from the goal of universal EV access. Affordable EVs are disappearing. The market is stratifying. Access to electric vehicle ownership is becoming more limited, not less. The democratization of EVs is stalling.

The policy implications extend beyond the Bolt. They affect how the entire US auto industry positions itself globally. If the US doesn't have competitive offerings in the affordable EV market, how does it expect to compete with Chinese manufacturers? If tariffs are supposed to protect US manufacturing, but tariffs make affordable EVs unviable, what's the actual strategy?

These questions will define the auto industry for years to come.

The Consumer Reality: What It Means to Shop for an Affordable EV in 2025

For people actually trying to buy an affordable electric vehicle right now, the implications of the Bolt's discontinuation are immediate and practical.

The affordable EV market is contracting. The Bolt was one of the few vehicles that genuinely competed with used gas cars on price. Without it, the options narrow significantly. You're looking at used EVs or vehicles that are more expensive than

For price-conscious EV shoppers, the used market becomes more attractive. A 2022-2023 EV from a mainstream manufacturer is often cheaper than a new vehicle and may still have remaining battery warranties. This is where affordable EV access happens now, not in the new vehicle market.

The loss of the tax credit compounds the problem. Without the $7,500 incentive, new EVs at lower price points don't make sense financially for many buyers. The effective price difference between a new EV and a used gas car narrows the EV's appeal. This is why used EV demand is strong: used models from before the tax credit was eliminated are cheaper on an after-incentive basis than new vehicles are now.

For manufacturers, this creates perverse incentives. They don't want to build low-margin vehicles in a high-tariff environment. They want to build high-margin vehicles where profitability is sustainable. Consumers who want affordable options are left with used inventory and longer waits for next-generation platforms.

This tension between corporate profitability and consumer access is at the heart of the Bolt's story. GM can't make the economics work on a $30,000 EV in the current policy environment. So the vehicle gets discontinued. Consumers who wanted that vehicle have to find alternatives. The market becomes less competitive at lower price points. Everyone loses.

Looking Ahead: What Comes After the Bolt

The obvious question: what replaces the Chevy Bolt EV?

GM's answer is vague. The company promises future investments in Fairfax for next-generation affordable EVs, but provides no timeline or specifications. This vagueness is telling. GM isn't ready to commit to a replacement because the economics are still uncertain.

What might the replacement look like? Probably a vehicle built on a newer EV platform with better range, better charging integration, and better features than the Bolt. Probably built in the US to avoid tariffs. Probably priced somewhere in the

When might it arrive? 2029 at earliest, probably later. That's a two-to-three-year gap with minimal affordable EV options from GM. Other manufacturers are likely facing similar gaps.

Will the replacement have the same value proposition as the Bolt? That depends entirely on whether the policy environment changes. If the tax credit returns, if tariffs shift, if manufacturing costs change, the economics improve dramatically. If the current policy environment persists, the replacement vehicle will likely be more expensive than the Bolt, with thinner margins for the company and less consumer value.

This uncertainty reflects a broader challenge for the auto industry. Long-term product planning is complicated when policy can shift suddenly. GM is taking a wait-and-see approach. It discontinued the Bolt. It's shifting to higher-margin vehicles. And it's waiting for clarity on the policy environment before committing to the next generation of affordable EVs.

It's a rational strategy for managing risk. It's just not great for consumers who want to buy affordable EVs today.

The Bigger Picture: How Global Trade Policy Reshapes Industries

The Chevy Bolt EV's story is ultimately about how global trade policy reshapes entire industries.

Manufacturing decisions are made on the margins. A 1% difference in costs, a tariff that changes the calculus, a tax incentive that disappears. These small changes compound into massive strategic shifts. A vehicle that's economically viable one year becomes unsustainable the next when policy changes.

The modern auto industry was built on free trade assumptions. Global supply chains. Optimized manufacturing locations. Cost minimization through geographic arbitrage. Tariff policy fundamentally threatens that model.

When tariffs make Chinese components expensive, onshoring makes economic sense. When tariffs make Mexican manufacturing uncompetitive, US facilities become attractive. When a tax credit disappears, low-margin vehicles become unsustainable. These policy tools reshape geography, strategy, and which products are viable.

GM's decisions reflect this reality. The company isn't trying to be difficult or anti-EV. It's responding to economic incentives created by tariff policy and tax credit elimination. In this environment, discontinuing the Bolt and focusing on higher-margin vehicles is the logical response.

The broader implication is important: policy drives corporate strategy more than most people realize. The decisions that affect which products exist, where they're made, and how much they cost are increasingly policy-driven, not market-driven. Understanding policy is key to understanding industry evolution.

For the automotive industry specifically, this means decades of adaptation ahead. Tariff structures will likely evolve. EV policy may shift. Supply chains will continue to reorient. And manufacturers will keep making hard decisions about which products fit within whatever economic and policy environment exists.

The Bolt is one casualty in a much larger transformation. It's not the last, and it won't be the most significant. But it serves as a clear signal: the era of assuming policy supports affordable EV adoption has ended. Manufacturers are now adapting to a different reality.

FAQ

Why is GM discontinuing the Chevy Bolt EV so quickly?

GM is discontinuing the Chevy Bolt EV because the vehicle's economics no longer work. The combination of tariff policy and the elimination of the federal EV tax credit has destroyed the vehicle's profitability. Without the

Will GM bring back an affordable EV after the Bolt is discontinued?

GM has promised to make new investments in Fairfax Assembly for next-generation affordable EVs, but the timing is undefined. The company says "we just don't know when," suggesting a timeline of 2029 or later. The vagueness reflects uncertainty about the policy environment and market demand for affordable EVs. A replacement vehicle may arrive, but not for several years after the Bolt's discontinuation.

How did tariff policy affect the Chevy Bolt EV's viability?

Tariffs made manufacturing costs unsustainable. With 25% tariffs on Mexican goods and up to 60% on Chinese goods, components sourced internationally became significantly more expensive. The Bolt, with a $29,990 price point and minimal margins, couldn't absorb these costs. Manufacturers would need to raise prices and lose customers or accept lower profits. Neither option was viable long-term, making the vehicle economically unsustainable.

What impact did the elimination of the federal EV tax credit have on the Bolt?

The elimination of the federal EV tax credit removed the financial foundation of the Bolt's value proposition. The credit was worth up to $7,500, representing roughly 25% of the vehicle's purchase price. Without it, the effective cost to consumers increased significantly, making the Bolt less competitive compared to used gas vehicles and other affordable transportation options. This single policy change was catastrophic for the Bolt's market position.

Where is the Chevy Bolt EV currently manufactured, and what will happen to the factory?

The Chevy Bolt EV is currently built at the Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas. After Bolt production ends in mid-2027, the facility will transition to manufacturing the gas-powered Chevrolet Equinox (from Mexico), followed by the Buick Envision (from China) in 2028. GM has promised future investments in the facility for next-generation affordable EVs, but the timeline is uncertain.

Are there any affordable EV alternatives to the Chevy Bolt EV?

The affordable EV market is shrinking. Few new vehicles at $30,000 or less are currently available. Used EVs from earlier years are the primary option for price-conscious buyers. Models like the Tesla Model 3, Hyundai Kona Electric, and others exist but at higher price points than the Bolt. The discontinuation of the Bolt further reduces affordable options in the EV market.

How does this decision reflect on GM's commitment to electric vehicles?

GM's decision to discontinue the Bolt doesn't indicate a retreat from EVs generally. The company produces electric Chevy Equinox, Chevy Blazer, and other EVs. However, it does signal a shift away from affordable EVs toward higher-margin vehicles. GM is repositioning its EV strategy to focus on vehicles with better profitability rather than vehicles aimed at price-sensitive consumers. This is a strategic choice driven by economics, not a rejection of EV technology.

What impact will the Bolt's discontinuation have on EV adoption rates in the US?

The discontinuation will likely slow EV adoption among price-sensitive consumers. The Bolt was one of the few affordable, proven EV options. Without it, the barrier to EV ownership increases for budget-conscious buyers. They'll either delay their EV purchase, look at used vehicles, or stick with gas-powered alternatives. This is particularly significant because price is the primary barrier to EV adoption for most consumers.

Could GM reverse this decision if Bolt sales exceed expectations?

It's theoretically possible but unlikely. GM has already committed the Fairfax Assembly facility to produce the Equinox and Envision on defined timelines. Reversing those commitments would require major organizational changes. Additionally, the underlying economics haven't improved. Even if Bolt sales are strong, the vehicle remains unprofitable at its current price point without the tax credit. GM would need to raise prices or accept losses, neither of which is sustainable.

How does the Bolt's discontinuation compare to how competitors are handling affordable EVs?

GM's decision is representative of an industry-wide pattern. Manufacturers are pulling back from affordable EV offerings as margins disappear. Tesla targets the $40,000+ market. Ford has eliminated lower-priced EV options. Volkswagen has delayed affordable EV launches. Only Chinese manufacturers like BYD are aggressively pursuing affordable EVs, but those vehicles aren't available in the US due to tariffs. The Bolt's discontinuation reflects industry-wide economic pressure, not a unique GM decision.

Key Takeaways

- GM is discontinuing the 2027 Chevy Bolt EV in mid-2027, just 18 months after market debut, due to tariff policy and elimination of the $7,500 federal EV tax credit

- The combination of 25-60% tariffs on imported components and loss of tax credits destroyed the Bolt's profitability margins at its $29,990 price point

- The Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas will shift from single-product Bolt manufacturing to produce gas-powered Equinox (2027) and Buick Envision from China (2028)

- The affordable EV market is contracting industry-wide as manufacturers retreat from low-margin vehicles and focus on higher-priced segments with better profitability

- Chinese EV manufacturers dominate affordable electric vehicle production globally, but tariffs prevent US consumers from accessing these cost-competitive options

![Why GM Is Ending Chevy Bolt EV Production in 2027 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-gm-is-ending-chevy-bolt-ev-production-in-2027-2025/image-1-1769126851930.jpg)