Windows 11 Update Shutdown Bug: What Happened & How to Fix [2026]

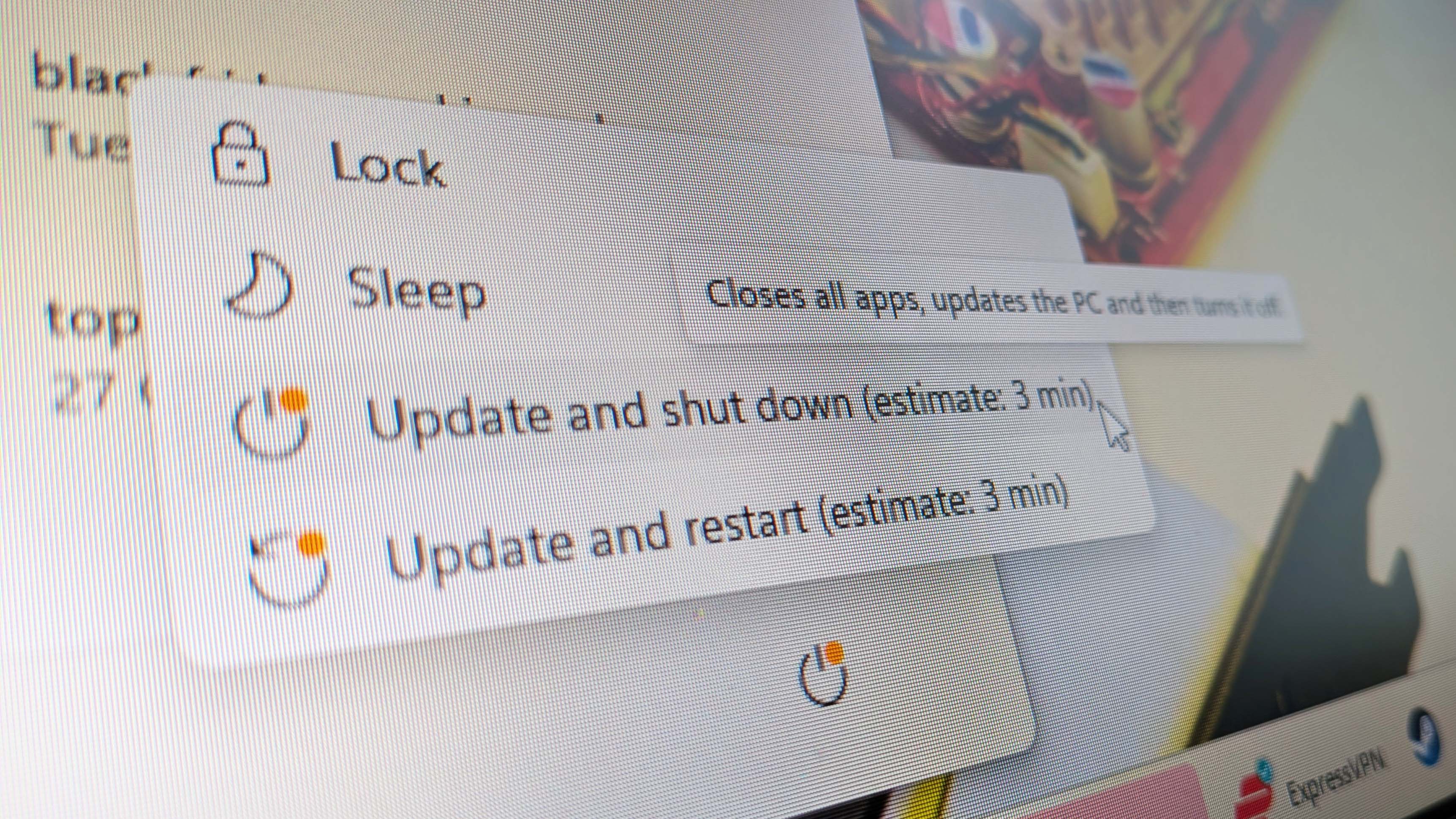

Your computer won't shut down. You press the power button, select "Shut down," and nothing happens. The screen stays on. The fans keep running. You're stuck in some kind of digital limbo.

That's exactly what happened to thousands of Windows 11 users in mid-January 2026, and it wasn't user error. It was Microsoft.

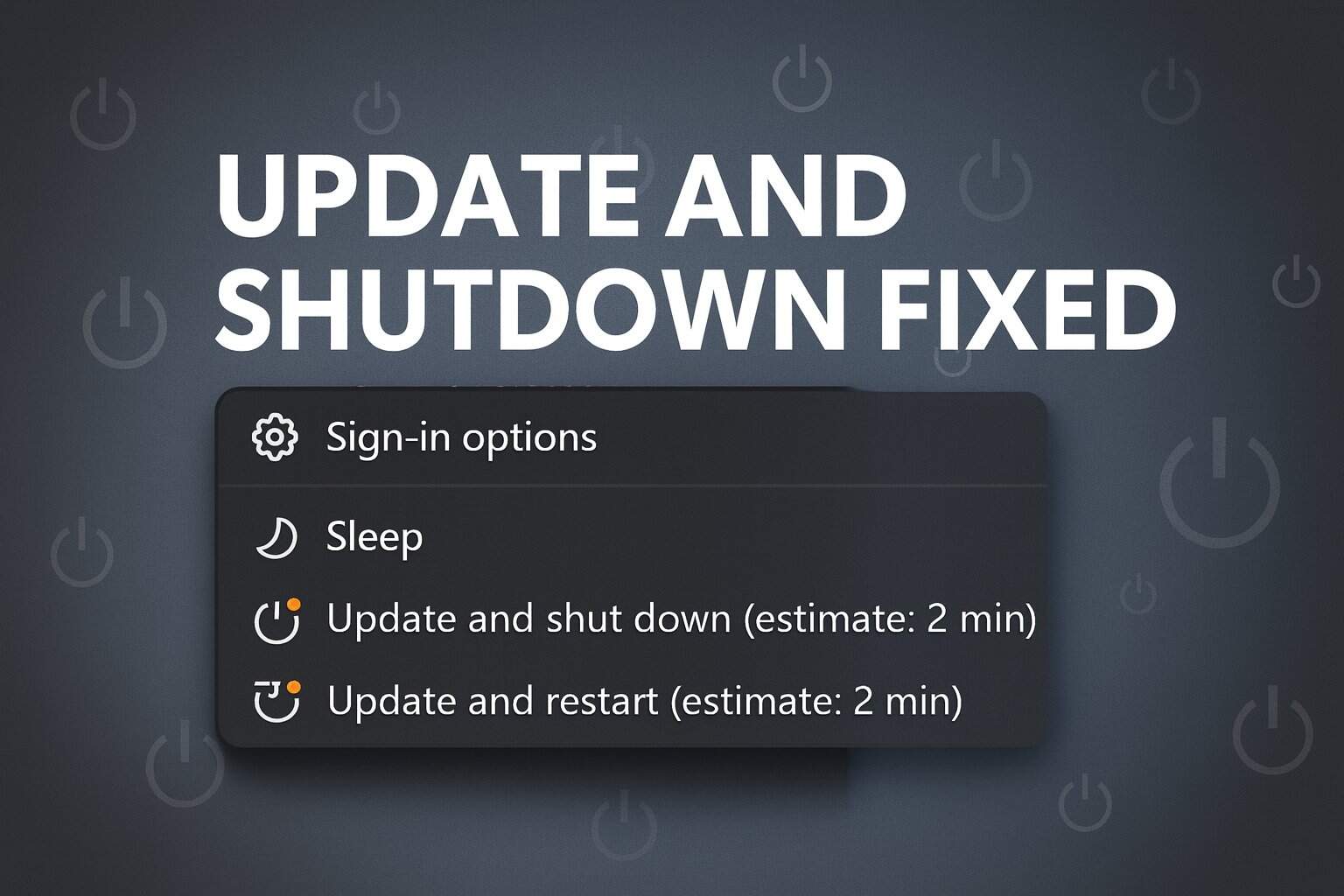

On January 13, 2026, Microsoft rolled out its first security update of the year for Windows 11. The update was supposed to patch security vulnerabilities and improve system stability. Instead, it introduced a critical bug that prevented certain devices from shutting down or entering hibernation mode. Even worse, it broke remote desktop connections for some users, making systems inaccessible remotely as reported by PhoneArena.

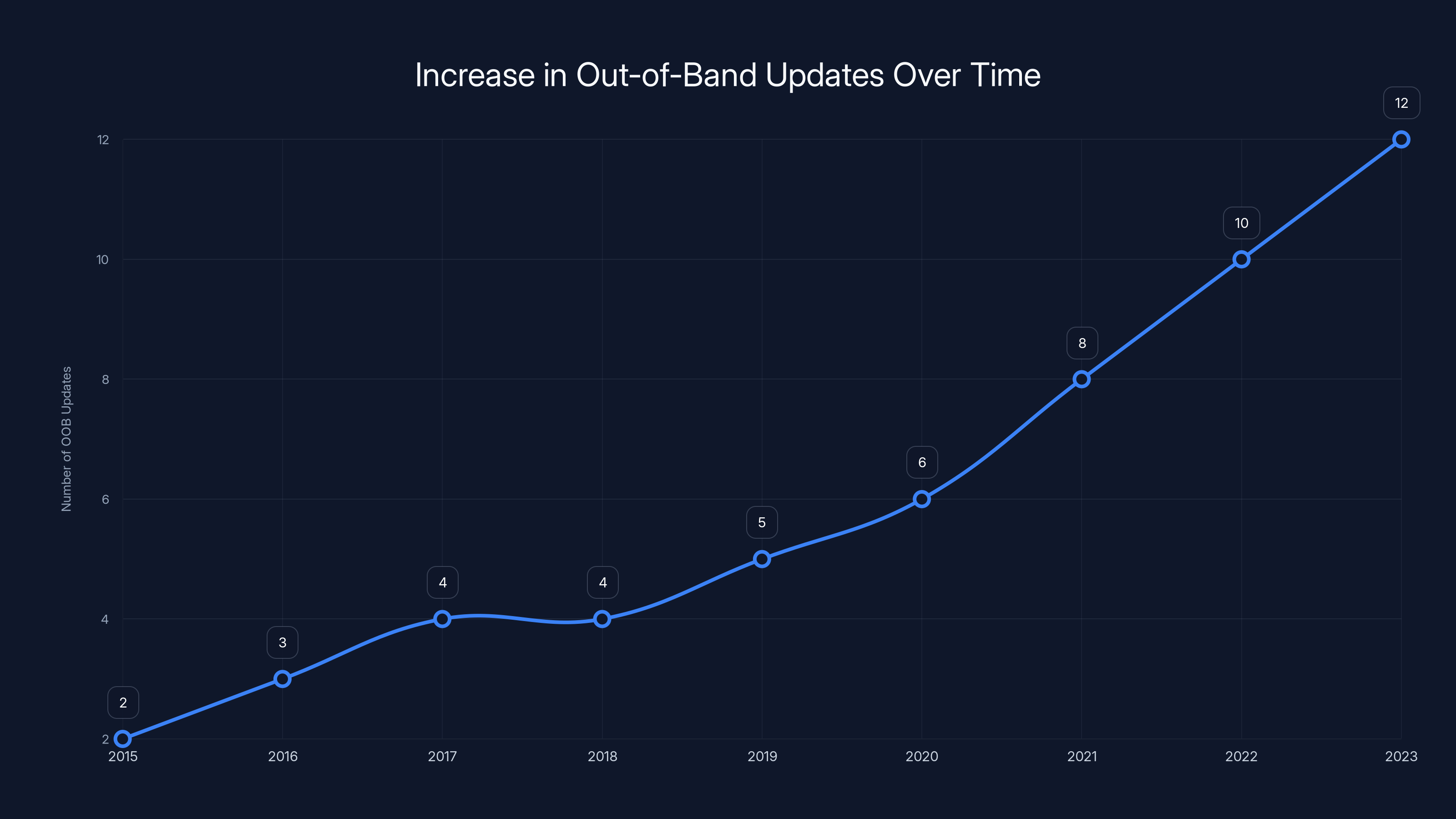

Four days later, on January 17, 2026, Microsoft was forced to release an emergency out-of-band (OOB) patch to fix the problems. This wasn't supposed to happen anymore. Out-of-band updates used to be rare, reserved for truly catastrophic failures. But they're becoming routine, and that tells you something important about the state of modern software quality.

This article breaks down exactly what went wrong, who was affected, why Microsoft's quality assurance processes failed, and what you need to do to protect your systems from similar issues in the future.

TL; DR

- The Bug: Microsoft's January 13, 2026 Windows 11 security update broke shutdown and hibernation on some systems with Secure Launch enabled according to BleepingComputer.

- Remote Desktop Issue: The same update prevented users from logging in via remote desktop on Windows 11 25H2, Windows 10 22H2 ESU, and Windows Server 2025 as noted by Petri.

- The Fix: Microsoft released an emergency out-of-band update on January 17, 2026 to address both issues as detailed by Windows Central.

- Affected Systems: Primarily Windows 11 version 23H2 for the shutdown bug; multiple versions for the remote desktop problem.

- Broader Pattern: This incident exemplifies a growing trend of buggy updates requiring emergency patches, raising questions about Microsoft's testing processes as discussed by The Verge.

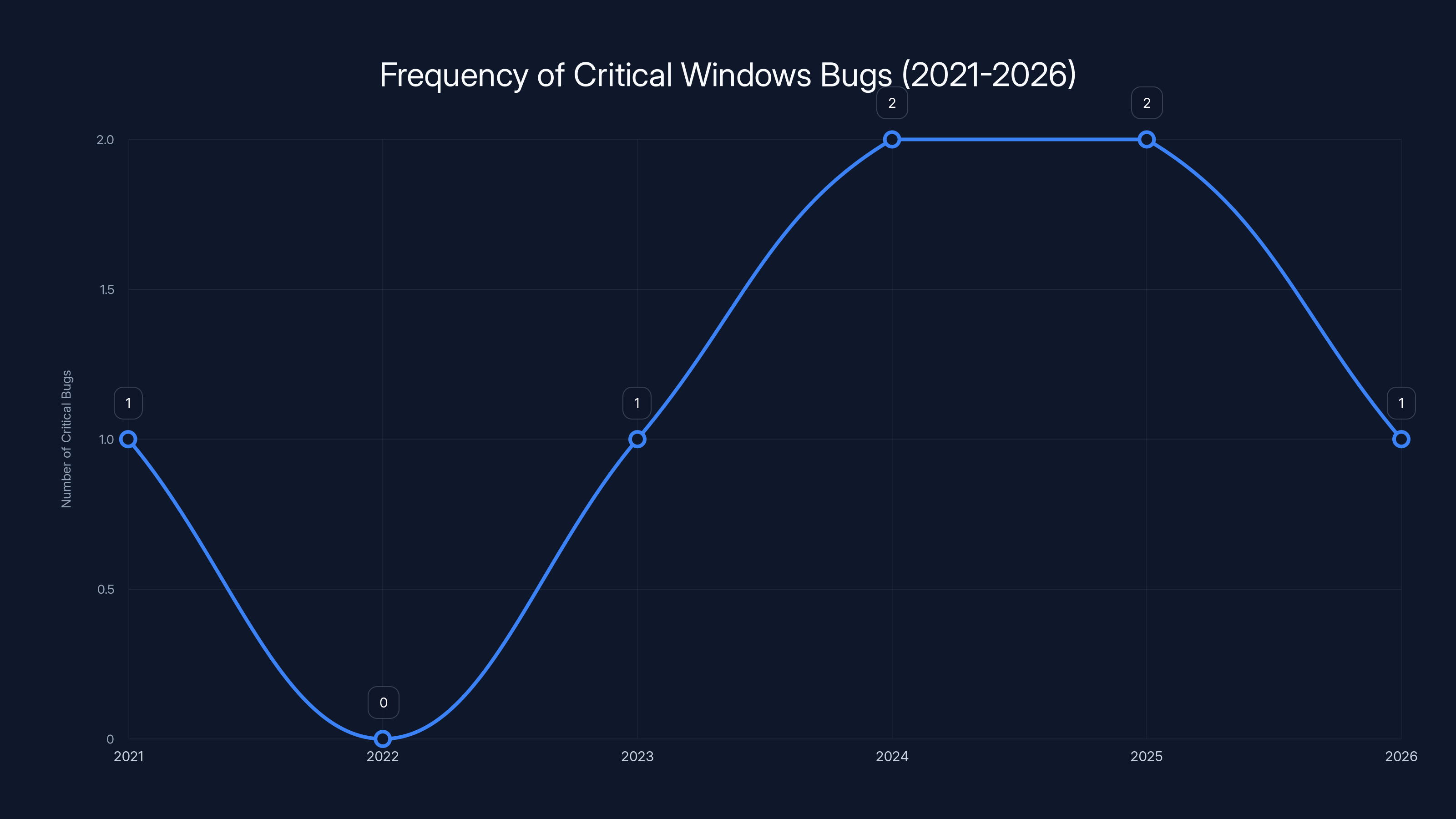

The chart shows an estimated trend of critical bug incidents in Windows updates from 2021 to 2026, highlighting recurring issues in recent years. Estimated data.

What Actually Happened With the January 2026 Windows Update

Let's start with the facts. On January 13, 2026, Microsoft released KB5051126, its regular monthly security update for Windows 11. The update included patches for multiple security vulnerabilities across Windows components, addressing various CVEs (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) as reviewed by Qualys.

For most users, the update installed silently in the background. For others, it was a disaster.

The first problem emerged within 24 hours. Support forums and social media began filling with reports from users who couldn't shut down their computers. They'd click the power button or select Shutdown from the Start menu, and the system would appear to shut down. The lock screen would go black. But then the computer would remain powered on, fans spinning, hard drive lights blinking. Some users reported their systems getting stuck in a state between shutdown and hibernation, consuming power while appearing offline as noted by Windows Latest.

The second problem was slightly different but equally frustrating. Users trying to access their computers remotely via Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) encountered authentication failures. The connection would initiate, but login would fail with authentication errors. For businesses relying on remote work infrastructure, this was a nightmare scenario. IT departments couldn't manage systems remotely, administrators couldn't access servers, and support staff couldn't troubleshoot issues without physical access as reported by Techzine.

Microsoft's own documentation indicated two distinct issues:

Issue One: Devices with Secure Launch enabled (a hardware-based security feature) would fail to shut down or hibernate after installing the January update. The issue specifically affected Windows 11 version 23H2 as analyzed by ZDI.

Issue Two: Remote connection applications were experiencing authentication and connection failures. This affected a broader range of systems including Windows 11 version 25H2, Windows 10 version 22H2 ESU (Extended Security Updates), and Windows Server 2025 as detailed by Petri.

What made this particularly frustrating is that the shutdown bug seemed almost random. Not every computer with Secure Launch enabled experienced the problem. This suggests the bug was triggered by a specific combination of hardware, firmware, and software configurations, making it difficult for users to predict whether they'd be affected.

The remote desktop failures were equally unpredictable. Some organizations experienced complete outages; others weren't affected at all. The variability suggests the authentication failure only manifested under specific credential types, network configurations, or security policy combinations.

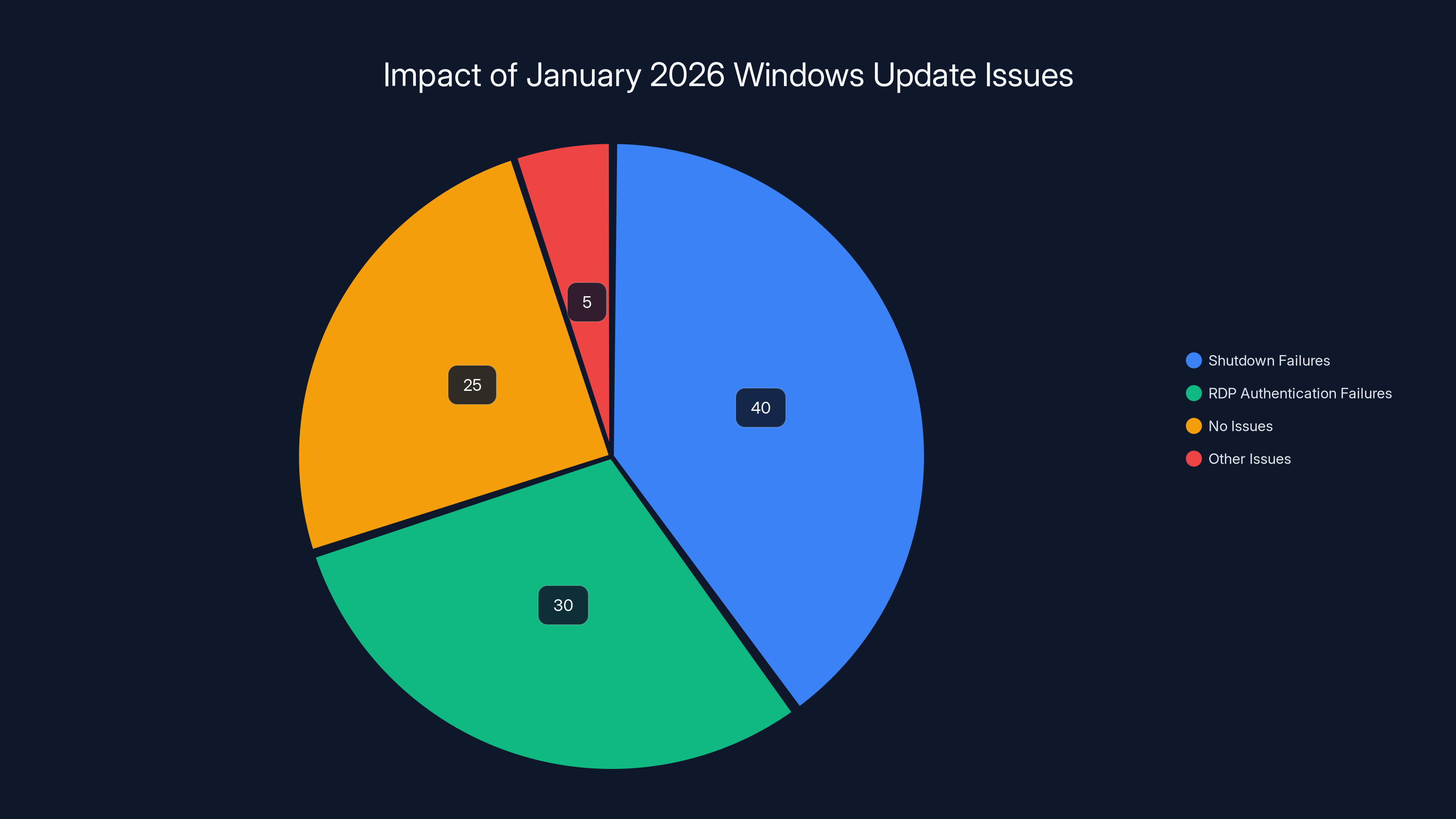

Estimated data suggests that 40% of users experienced shutdown failures, while 30% faced RDP authentication issues. A significant portion, 25%, reported no issues at all. (Estimated data)

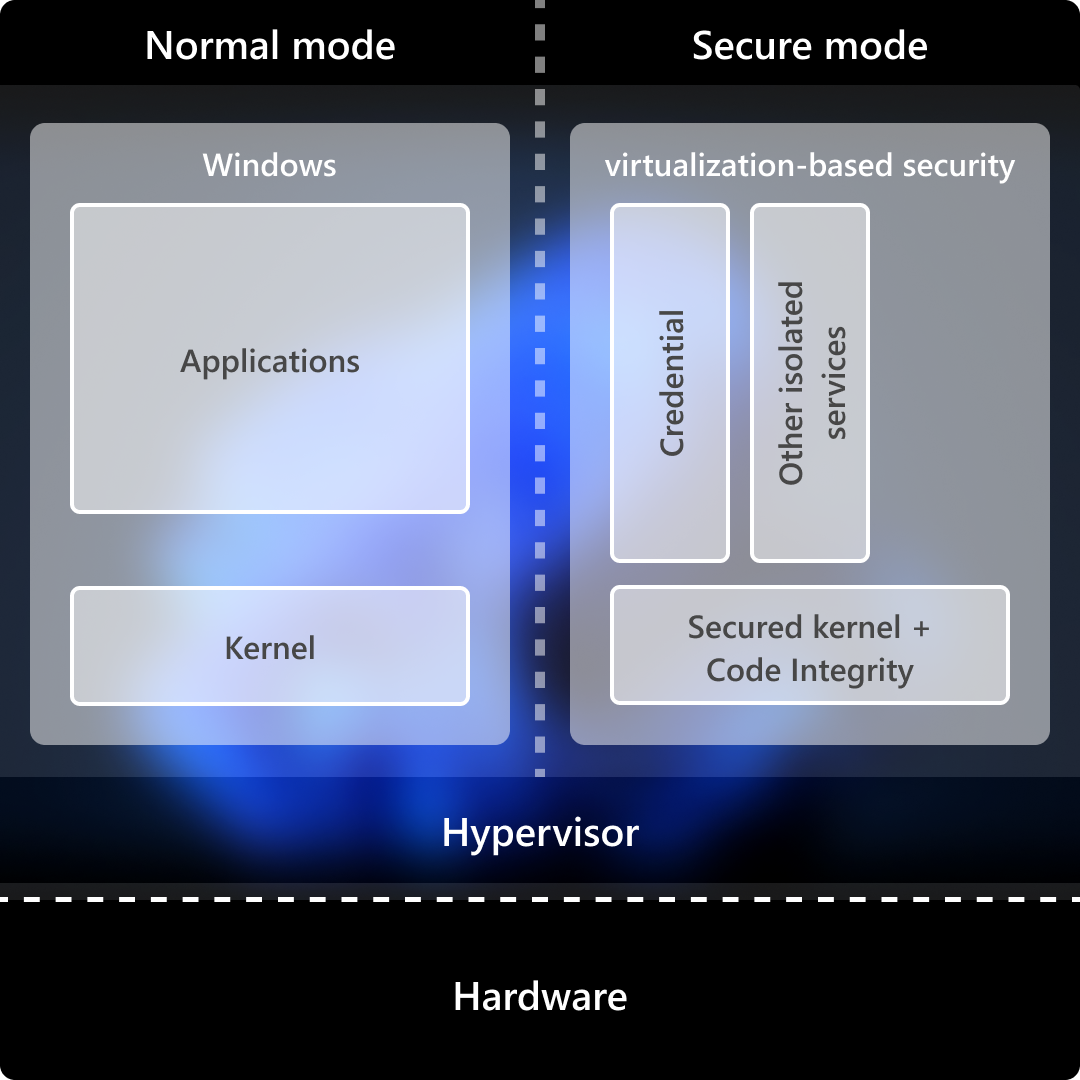

Understanding Secure Launch and Why It Made Things Worse

Secure Launch is a Windows security feature that sounds impressive in marketing materials and legitimately improves system security in practice. It's built on hardware virtualization and firmware security mechanisms, particularly on Intel and AMD processors that support hypervisor code integrity.

The basic idea: your computer's firmware boots a trusted hypervisor before the Windows kernel loads. This hypervisor protects the kernel from low-level attacks and rootkits. Attackers can't modify kernel code without the hypervisor detecting it. In theory, it's brilliant. In practice, it adds complexity.

And complexity is where bugs hide.

The January update apparently modified how Windows interacts with the Secure Launch hypervisor during shutdown. Specifically, the shutdown sequence needs to properly notify the hypervisor that the system is powering down. If that notification fails or times out, the hypervisor might keep the hardware in a state where the CPU refuses to actually power down as discussed by The Verge.

This is a classic example of a bug that only appears when software changes interact with firmware in unexpected ways. Microsoft's testing labs probably ran extensive shutdown tests, but those tests might not have covered the exact combination of firmware versions, UEFI settings, and hardware configurations that triggered the bug.

Secure Launch adds another layer of complexity to the shutdown process. When you combine a new code path in Windows with the Secure Launch hypervisor interaction, you create a testing matrix that's nearly impossible to fully exhaust. There are thousands of possible combinations of hardware, firmware versions, UEFI configurations, and Windows versions.

Something in that matrix broke, and Microsoft didn't catch it before shipping the update to millions of users.

The Remote Desktop Authentication Failures: A Different Beast

The remote desktop failures were less about hardware complexity and more about credential handling. Remote Desktop Protocol uses Kerberos authentication on domain-joined systems and credential delegation to pass user credentials securely.

Something in the January update changed how Windows handles these credentials in RDP sessions. Microsoft's changelog didn't specify exactly what, but the timing suggests it was either:

- A change to the Kerberos implementation or token handling

- A modification to the credential provider system that RDP depends on

- A security hardening that was too aggressive and blocked legitimate authentication attempts

The fact that it affected Windows 10, Windows 11, and Windows Server 2025 simultaneously suggests the issue was in a shared component used across all these operating systems. Most likely, it was somewhere in the authentication stack that all these versions depend on as analyzed by ZDI.

RDP authentication failures are particularly serious because they break remote management infrastructure. An IT administrator can't fix a broken system remotely, can't apply patches, can't troubleshoot issues. They need physical access, which is impossible for cloud servers and many modern data centers.

For enterprises, this wasn't just an inconvenience. It was a potential security incident. Any service that depends on Remote Desktop access went offline. This could include:

- Remote support and help desk systems

- Cloud-based virtual machines that administrators access via RDP

- Hybrid setups where on-premises administrators manage cloud infrastructure

- Monitoring and alerting systems that rely on RDP for configuration

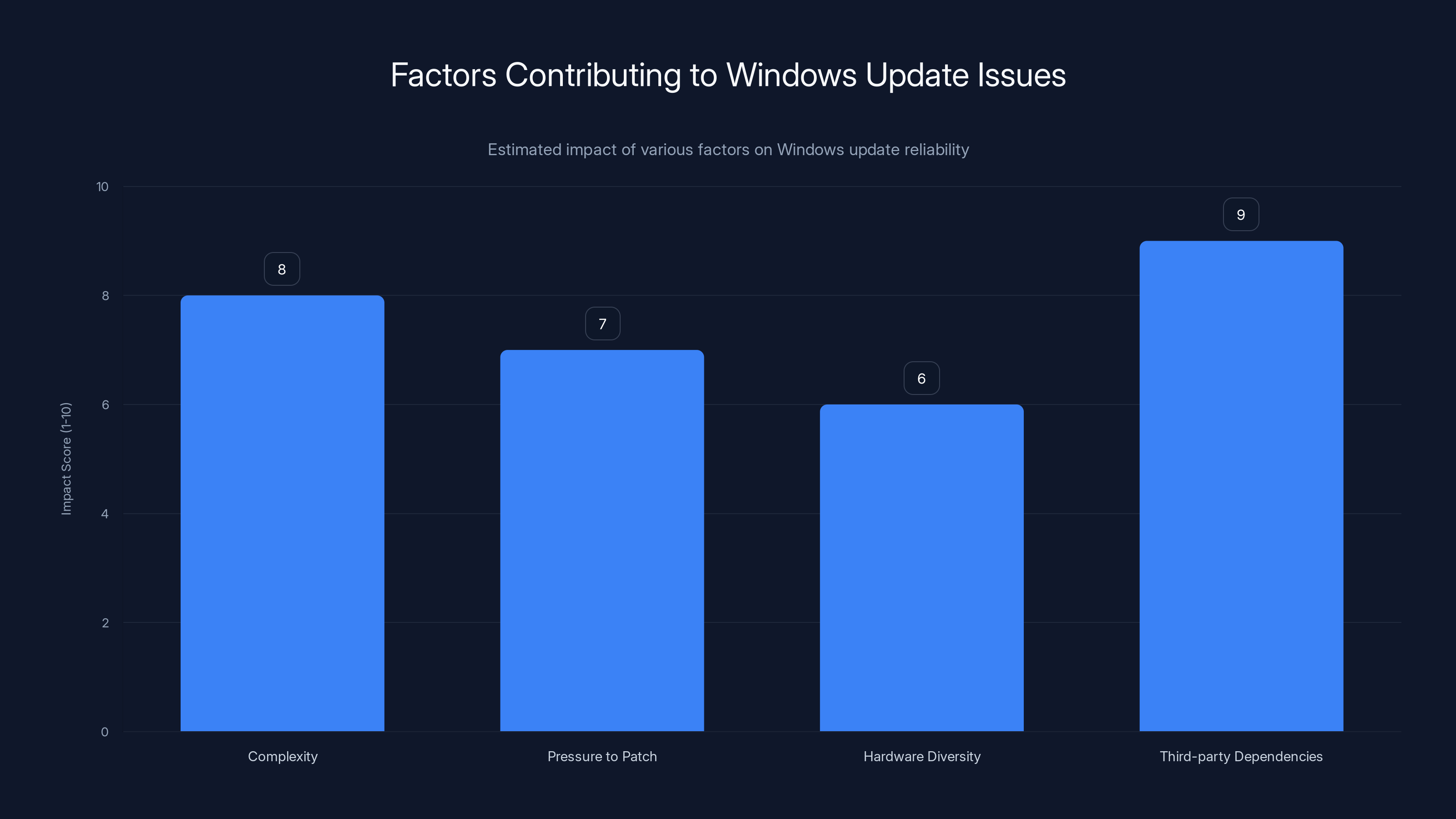

Complexity and third-party dependencies are major factors contributing to Windows update issues. Estimated data.

Why Out-of-Band Updates Are Becoming More Common

Out-of-band updates used to mean something. They were rare, reserved for zero-day exploits or catastrophic failures that could crash entire systems. Microsoft might issue one or two per year, and when it did, IT departments treated it as a crisis.

Now? We're seeing multiple OOB updates per quarter. Something has changed in Microsoft's development and testing processes, and not for the better.

There are several possible explanations:

1. Complexity Has Increased Exponentially: Modern Windows isn't just an operating system. It's a collection of hundreds of subsystems, each with its own dependency graph. The authentication system, hardware abstraction layer, driver framework, security subsystems, and cloud integration all interact in ways that are difficult to fully test. One change in one subsystem can have ripple effects elsewhere as reviewed by Qualys.

2. Testing Gaps Are Widening: As the codebase has grown, the number of possible test cases has grown exponentially faster. You can't test every combination of hardware, firmware, drivers, and configuration. Test suites focus on the most common scenarios, which leaves edge cases unexamined.

3. The Security Patch Treadmill: Microsoft's need to patch security vulnerabilities has accelerated, particularly as exploit techniques become more sophisticated. This creates pressure to ship patches quickly, potentially at the expense of thorough testing as discussed by The Verge.

4. Hardware Diversity Is Chaotic: Windows runs on more hardware configurations than any operating system in history. There are thousands of different motherboards, firmware versions, device drivers, and peripheral combinations. A change that works fine on the hardware in Microsoft's labs might break on obscure configurations that represent millions of actual users.

5. Third-Party Driver Quality: Much of Windows's functionality depends on third-party drivers from hardware vendors. These drivers have inconsistent quality and update frequency. A Windows change might break interaction with a driver that hasn't been updated in three years, affecting users who can't update the driver themselves.

The result is a vicious cycle: Microsoft ships updates without catching all issues, users encounter bugs, Microsoft rushes out emergency patches, those patches introduce new bugs, and the cycle continues.

The Timeline of Failure: When Did Microsoft Know?

Microsoft released the January 13 update on its regular Patch Tuesday schedule. The first bug reports started appearing within 24 hours. By January 16, the issue was widespread enough that major tech outlets were covering it. Microsoft acknowledged the problems by January 16 and released the OOB patch on January 17 as detailed by Windows Central.

That's a remarkably fast response. But it also raises questions: How did such critical bugs make it past testing?

There are a few possibilities:

Scenario 1: The bugs only manifested in production. The specific combination of hardware and configurations that triggered the issue wasn't represented in Microsoft's test environment. This isn't uncommon with enterprise software.

Scenario 2: The bugs were known but deemed low priority. Microsoft's testing might have found these issues but classified them as affecting a small percentage of users. The decision was made to ship the update and fix issues in a subsequent patch.

Scenario 3: The bugs were introduced in the final stages of build preparation. Last-minute changes or emergency patches added to the update might not have been fully tested against the entire test matrix.

Scenario 4: The testing environments weren't representative enough. Microsoft's labs might have been missing specific hardware, firmware combinations, or configurations that the majority of real users actually have.

We'll probably never know which scenario is accurate. Microsoft doesn't typically publish post-mortems explaining how bugs like this escape testing. The company prefers to move on once a patch is released.

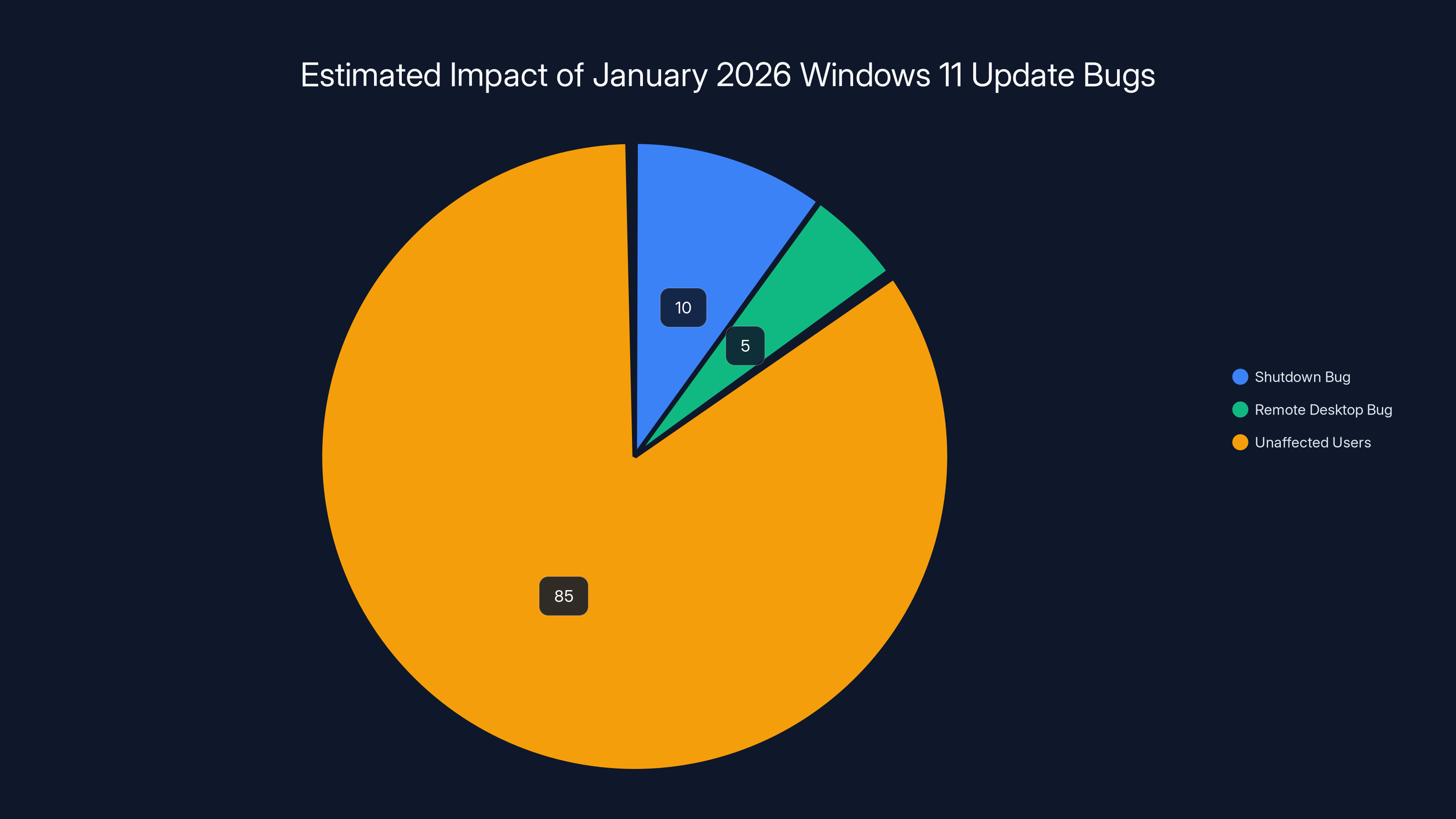

Estimated data suggests the shutdown bug affected around 10% of users, while the remote desktop bug impacted 5%, with 85% of users unaffected. Estimated data.

Who Was Actually Affected? Breaking Down the Impact

The shutdown bug primarily affected Windows 11 version 23H2 with Secure Launch enabled. That's a more specific subset than the remote desktop issue, which affected multiple OS versions.

How many users were affected? Microsoft didn't release exact numbers, but we can estimate:

For the shutdown bug:

- Windows 11 version 23H2 is running on approximately 35-40% of Windows 11 systems globally

- Secure Launch is enabled by default on new systems with compatible hardware, but many older systems don't have it enabled

- Rough estimate: 5-15% of all Windows users might have been affected

For the remote desktop issue:

- This affected Windows 10 22H2 ESU, Windows 11 25H2, and Windows Server 2025

- Remote Desktop users represent a smaller subset: primarily IT administrators, remote workers, and businesses with centralized infrastructure

- Rough estimate: 2-8% of Windows users, but potentially 20-40% of enterprise environments

The remote desktop issue was potentially more damaging because of its concentration in enterprise environments where systems are actively managed and mission-critical. A single failed RDP connection can cascade into infrastructure-wide issues.

How the Emergency Fix Was Deployed: Microsoft's Response

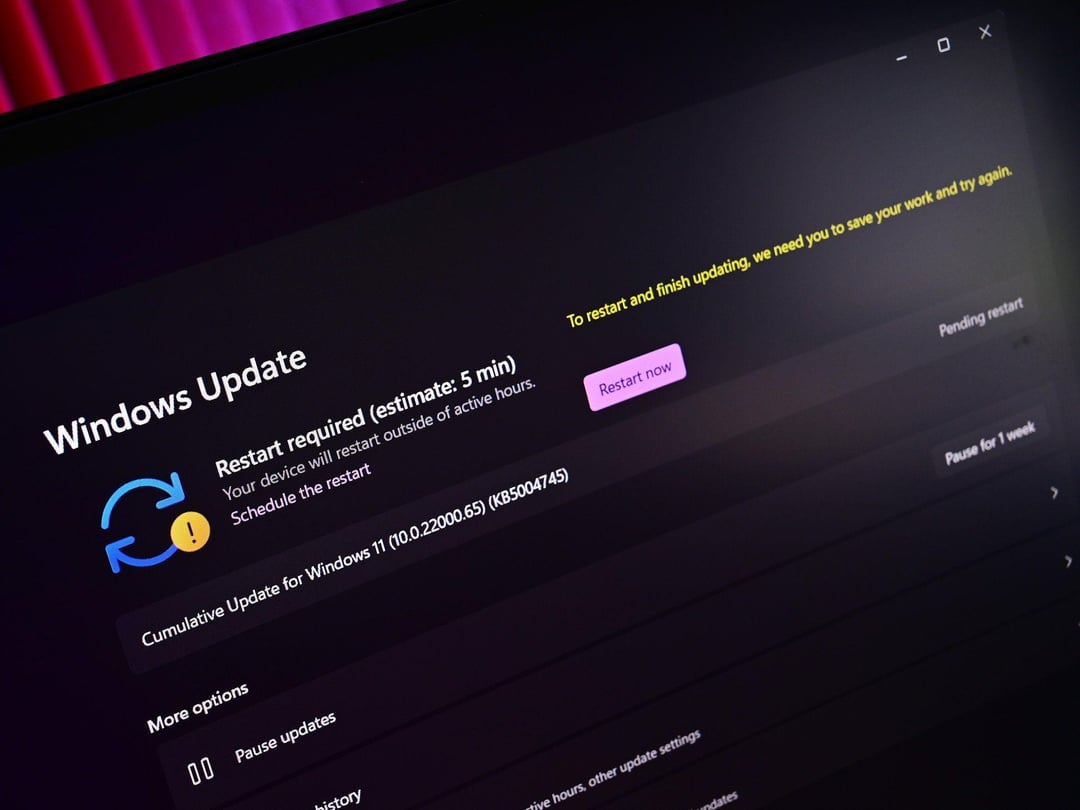

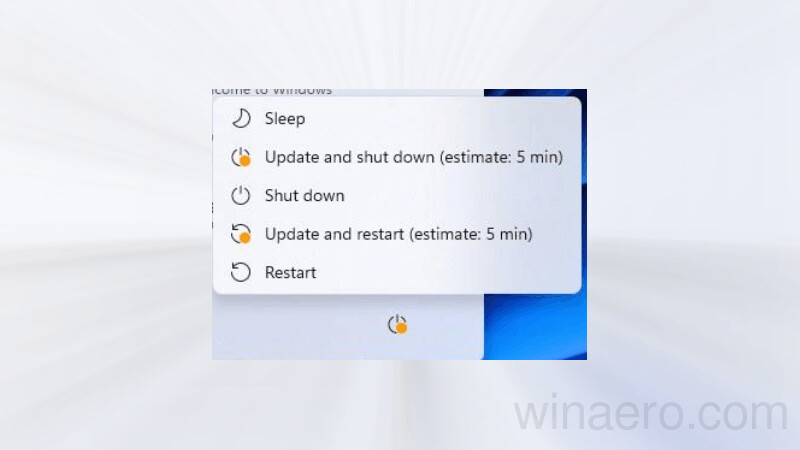

Microsoft released KB5051127 on January 17, 2026, as an out-of-band emergency patch addressing both issues. Unlike the regular Patch Tuesday updates that install on the second Tuesday of each month, OOB updates can be released at any time.

The deployment happened in stages:

Stage 1: Immediate availability: The patch was made immediately available to Windows Update. Systems checking for updates would see it within a few hours.

Stage 2: Prioritized delivery: Systems that already had the buggy January 13 update installed were potentially bumped to the front of the update queue, receiving priority.

Stage 3: Manual download: The patch was made available for manual download from Microsoft's Update Catalog for organizations that wanted to apply it immediately to a limited set of systems before broader deployment.

For home users, the patch installed like any other update. For enterprise organizations, many IT departments likely tested the patch on a small subset of systems before deploying broadly, which meant some users might not receive the fix for days or weeks after it was released.

The patch itself was designed to be cumulative, meaning it included all the legitimate security fixes from the January 13 update plus the bug fixes. Organizations that installed the OOB update were getting both sets of fixes.

Microsoft's documentation indicated that the OOB patch addressed:

- The shutdown and hibernation failure for systems with Secure Launch

- The remote desktop authentication failures across all affected versions as reported by PhoneArena.

What Microsoft didn't clearly communicate was whether the patch introduced any new issues. They were confident enough to push it globally, but there was inherent risk: after all, the original January 13 update was supposed to be fully tested too.

Estimated data shows a clear upward trend in the frequency of Microsoft's out-of-band updates, highlighting increased complexity and security challenges.

Comparing This to Previous Microsoft Update Disasters

This wasn't Microsoft's first rodeo with buggy updates, and it won't be the last. Let's look at some historical context.

The Windows 10 October 2018 Update: This update deleted users' files. Seriously. The update was so broken that Microsoft pulled it from Windows Update after just two weeks. Users who installed it found their Documents, Downloads, and other folders empty. It took Microsoft weeks to issue a fix.

The June 2021 Print Nightmare Vulnerability: Microsoft patched a critical remote code execution vulnerability in Windows Print Spooler, but the patch was incomplete. Attackers could still exploit the vulnerability with the patch installed. It took three attempts to fix it properly.

The August 2023 Outlook Update: An update to Outlook on Windows broke the application for many users, leaving it refusing to start. The issue persisted for days before Microsoft released a fix.

The May 2024 Crowd Strike Falcon Sensor Incident: While not a Microsoft update, the third-party endpoint protection software caused a global Blue Screen of Death (BSOD) event affecting millions of Windows systems. This demonstrated how vulnerable Windows infrastructure is to badly tested kernel-level code.

The January 2026 shutdown bug fits a clear pattern: Microsoft ships an update, the update breaks critical functionality for some users, Microsoft releases an emergency patch. The cycle repeats every few months.

The Broader Question: Is Windows Update Trustworthy?

There's a legitimate question that emerges from incidents like this: If you install a Windows update and it breaks your system, is that worse than not installing it?

Security vulnerabilities are real threats. Not patching leaves systems exposed to remote code execution, data theft, and other attacks. But a bad patch that breaks your shutdown or remote access capabilities is also a serious problem.

For most users, the answer is still "install the patches." The security risks of running unpatched Windows outweigh the risks of a bad patch affecting a small percentage of users. But this logic gets shakier the more frequent these incidents become.

For enterprise organizations, the approach is different. Many don't install updates immediately. They wait a week or two, watch for reports of issues, and only deploy to production after they've tested on non-critical systems. This delay means they're temporarily vulnerable to known exploits, but they avoid the risk of a broken update taking down their infrastructure.

Microsoft's response times have improved, which is good. The company is releasing OOB patches within 4-5 days of discovering the issue. But the fact that these patches are necessary at all suggests systemic testing issues as detailed by Windows Central.

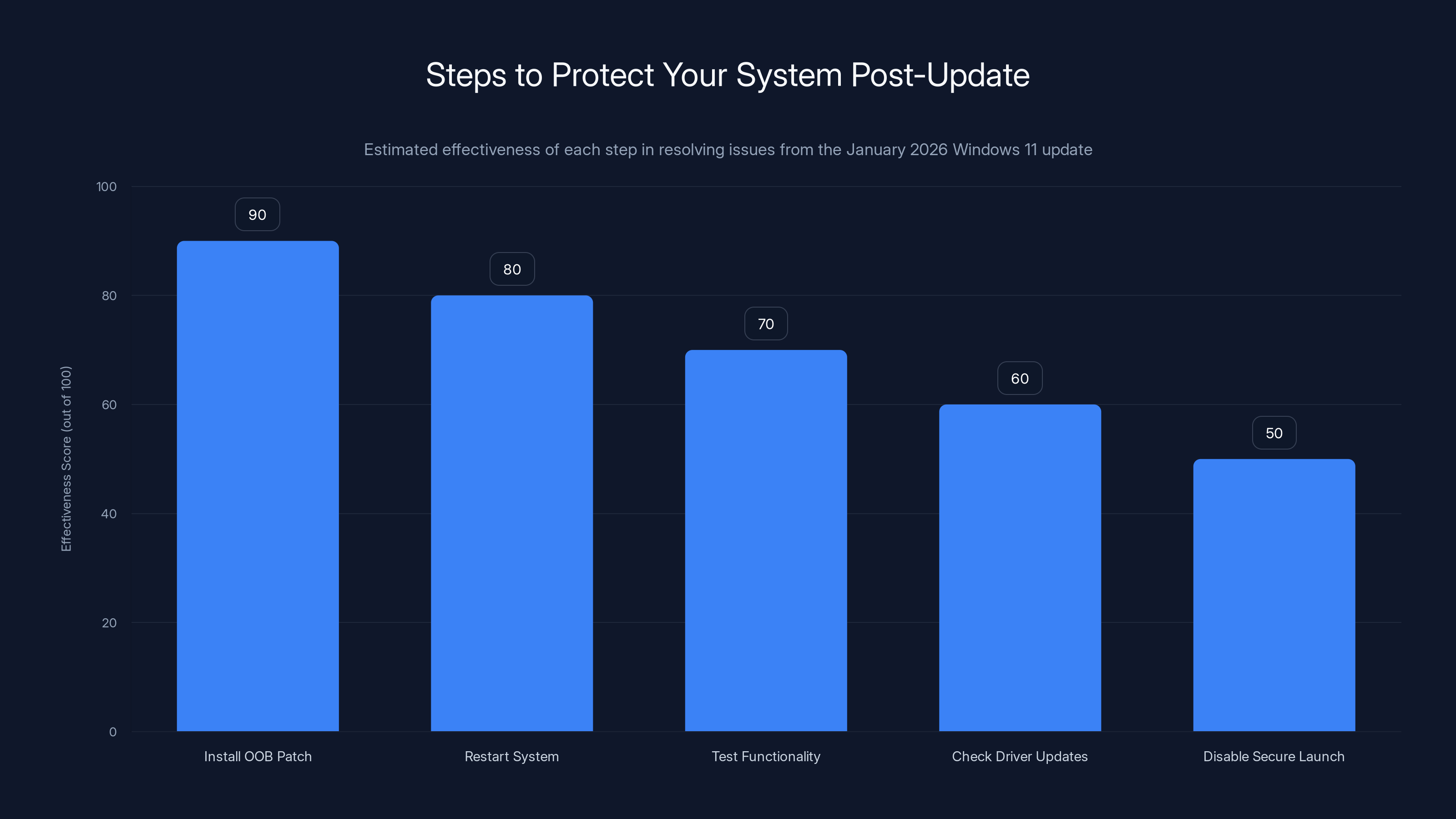

Installing the OOB patch is the most effective step, with a score of 90, in resolving issues from the January 2026 Windows 11 update. Estimated data.

What You Should Do: Practical Steps to Protect Your System

If you're running Windows 11 and were affected by the January 2026 update, here's what you need to do:

Step 1: Install the OOB patch. Go to Settings > System > About and click "Check for updates." Windows will offer KB5051127 or a newer security update that includes the fix. Install it.

Step 2: Restart your system. Once the patch is installed, restart your computer. This ensures the new code paths are fully initialized.

Step 3: Test critical functionality. If you use Remote Desktop, test connecting to another computer. If you have Secure Launch enabled, test shutting down your system to ensure it fully powers off.

Step 4: Check for driver updates. Sometimes buggy updates interact poorly with outdated drivers. Check your motherboard manufacturer's website for UEFI/BIOS updates and check Windows Device Manager for driver updates.

Step 5: Consider disabling Secure Launch temporarily (only if you're experiencing persistent shutdown issues). Open Windows Security > Device Security > Core isolation and toggle "Virtualization-based security" off. This disables Secure Launch. Only do this if the OOB patch doesn't fully resolve your issue.

For enterprise organizations:

Step 1: Test the OOB patch in a staging environment. Don't deploy directly to production. Create a test group of 5-10 systems running the same configuration as your production environment and apply the patch.

Step 2: Monitor for regressions. After deploying to test systems, monitor event logs for any unusual activity or errors. Run your standard test suites to verify functionality.

Step 3: Deploy in waves. Once you're confident the patch is safe, deploy to production in waves. Don't update all systems simultaneously. This lets you catch any unforeseen issues before they affect your entire infrastructure.

Step 4: Maintain a rollback plan. Have a documented process for uninstalling the patch if it causes unexpected problems. For uninstalling Windows updates, open Settings > System > Optional features > More options > View update history > Uninstall updates.

Step 5: Consider extending patch management windows. If you're seeing frequent OOB patches, extend your testing window from days to a week or two before deploying broadly.

The Technical Root Cause: What We Can Infer

While Microsoft hasn't published detailed technical information about the root causes, we can make some educated inferences based on what we know.

For the shutdown issue: The bug was most likely introduced in code that handles the shutdown sequence for systems with Secure Launch. This could be in the Windows kernel, the UEFI bootloader, or the hypervisor communication layer. The code probably added a new API call or changed how shutdown notifications are passed to the hypervisor. Under specific timing conditions or with certain hardware configurations, this new code path deadlocks or times out, preventing the shutdown sequence from completing.

The fact that it only affected some systems suggests it's dependent on:

- Specific processor families or microcode versions

- Particular UEFI implementations or versions

- Specific firmware configurations or settings

- Device drivers that interact with shutdown sequences

For the remote desktop issue: This is likely in the authentication layer. RDP on Windows depends on the Local Security Authority (LSA), credential providers, and Kerberos implementation. The January update probably changed something in one of these components, making it incompatible with how RDP passes or validates credentials.

The breadth of affected systems (Windows 10, 11, and Server 2025) points to a shared component. Most likely candidates:

- A change to Kerberos token handling

- A modification to credential caching

- An update to the Remote Desktop Protocol server code

- A change to how TLS certificates are validated for RDP connections

The fact that the fix was released four days later suggests either:

- The root cause was identified quickly (pointing to a recently modified code section)

- The fix was a revert of the problematic change (the safest approach)

- A small targeted patch was created that doesn't fully address the underlying issue (risky but fast)

Microsoft likely used option 1 or 2, given how quickly the patch was released.

Looking Forward: Will This Keep Happening?

Unfortunately, yes. The January 2026 incident was not a one-time occurrence, and it won't be the last time a Windows update breaks critical functionality.

Here's why:

The complexity problem doesn't go away: Windows's complexity will continue to increase as new features are added. The codebase is too large for complete comprehensive testing.

Pressure to ship patches increases: As cyber threats evolve, the need to patch vulnerabilities quickly becomes more urgent. This creates pressure to ship patches faster, at the potential expense of thorough testing.

Hardware diversity keeps growing: Every year, new processor architectures, firmware implementations, and hardware configurations emerge. Microsoft's testing labs can't keep up with this diversity.

Third-party dependencies remain problematic: Windows depends on thousands of third-party drivers and software. A Windows change that seems safe might break compatibility with an obscure driver that millions of users still rely on.

What might improve the situation:

Better staged rollouts: Microsoft could deploy new updates to a percentage of machines first (1%, then 5%, then 25%, etc.), monitoring for issues before broader deployment. This would catch problems affecting even 1% of users before affecting everyone.

More transparency: Microsoft could publish more detailed post-mortems explaining how bugs escaped testing and what changes are being made to prevent similar issues.

Extended testing windows: Microsoft could extend the time between when an update is finalized and when it's shipped to users, allowing for more real-world testing before broad deployment.

Better integration with cloud telemetry: Windows now collects extensive diagnostic data. Microsoft could use this data to test updates on representative samples of real hardware before shipping broadly.

None of these changes are happening yet, which is why we'll likely see similar incidents in the coming months and years.

Best Practices for Windows Update Management Going Forward

Given the reality of buggy updates, here's a strategic approach to Windows update management:

For home users:

- Don't install updates immediately. Wait at least a week after release, then check tech news and social media for reports of problems.

- Install critical patches quickly, wait on others. If Microsoft releases an emergency patch for a zero-day vulnerability, install immediately. Regular monthly patches can wait a few days.

- Maintain backups. Always have a full system backup before installing major updates. If something breaks, you can restore.

- Join the Windows Insider program if you're tech-savvy. This lets you test future updates before they're released broadly.

For small businesses:

- Implement a staged deployment. Never deploy updates to all systems simultaneously.

- Maintain a test environment. Keep 2-3 representative systems that get updates first, before your production environment.

- Document your system configurations. Know what versions of drivers, firmware, and third-party software you're running. This helps troubleshoot when updates break things.

- Subscribe to Microsoft's security update notifications. Register for email alerts when updates are released.

For enterprises:

- Extend your patch management window. Instead of deploying patches on the day they're released, test for a full week before deploying to production.

- Use Windows Update for Business. This allows you to defer updates by up to 365 days while still receiving security patches.

- Implement driver update management. Many update issues come from outdated drivers. Establish a process for updating drivers alongside OS patches.

- Create rollback procedures. Document exactly how to uninstall problematic updates and have procedures in place to do this quickly at scale.

- Monitor Microsoft's support pages. Check for known issues with each update before deploying. Microsoft maintains a "Known Issues" document for each monthly update.

The Bigger Picture: Software Quality in 2026

The January 2026 Windows update incident isn't unique to Microsoft. It's symptomatic of a broader software industry trend: complexity increasing faster than our ability to test it.

Every major software company experiences this. Apple's macOS gets regular updates that break functionality for some users. Linux distributions have driver compatibility issues. Even small companies with focused products occasionally ship bugs that should have been caught in testing.

The difference is that Microsoft's updates affect hundreds of millions of machines globally, making even a 1% failure rate a significant problem affecting millions of users.

This incident serves as a reminder that software perfection is impossible. The best we can do is:

- Test as thoroughly as possible

- Deploy in stages to catch problems early

- Fix issues quickly when they're found

- Communicate transparently with users

Microsoft did okay on points 2-4. On point 1, they clearly fell short. Whether that improves in future updates remains to be seen.

FAQ

What was the January 2026 Windows 11 update bug?

Microsoft's January 13, 2026 security update for Windows 11 contained two critical bugs. The first prevented devices with Secure Launch enabled from shutting down or hibernating properly. The second broke Remote Desktop Protocol authentication for users on Windows 11 25H2, Windows 10 22H2 ESU, and Windows Server 2025. Both issues were fixed with an emergency patch released on January 17, 2026 as detailed by Windows Central.

How many people were affected by this update bug?

Exact numbers weren't released by Microsoft, but estimates suggest the shutdown bug affected 5-15% of Windows 11 users globally (those running version 23H2 with Secure Launch enabled), while the remote desktop issue primarily impacted enterprise environments using RDP for system management. The remote desktop issue was more damaging per affected user due to its critical nature for IT infrastructure as reported by PhoneArena.

Does the OOB patch fix all the problems?

Yes, according to Microsoft, the OOB patch released on January 17, 2026 (KB5051127) fully addresses both the shutdown/hibernation issue and the remote desktop authentication failures. The patch also includes all legitimate security fixes from the original January 13 update, so installing it provides both the bug fixes and the security protection as detailed by Windows Central.

Should I disable Secure Launch if I'm having shutdown issues?

Only as a last resort. Secure Launch provides important security protection against low-level firmware attacks and rootkits. If the OOB patch doesn't resolve your shutdown issues, disabling Secure Launch will temporarily fix the symptom but leaves your system more vulnerable to attacks. Instead, try updating your UEFI/BIOS firmware first, which may resolve the incompatibility without disabling security features.

Why do buggy updates keep happening if Microsoft has massive testing resources?

The core issue is scale and complexity. Windows runs on billions of devices with millions of different hardware configurations, firmware versions, and third-party driver combinations. It's mathematically impossible to test every combination. Additionally, the pressure to ship security patches quickly sometimes conflicts with the need for thorough testing. Out-of-band patches are becoming more common as a result of these systemic issues as discussed by The Verge.

How can I check if my system was affected by this bug?

For the shutdown issue, check if you have Secure Launch enabled (Windows Security > Device Security > Core isolation) and if you're running Windows 11 version 23H2. For the remote desktop issue, test connecting to another computer via Remote Desktop. If connection works fine before January 13 but fails afterward, you were likely affected. Both issues should be resolved after installing the OOB patch.

What's the safest way to deploy this update to multiple computers?

For organizations, implement a staged rollout: test the patch on 5-10 representative systems first, monitor those systems for 24-48 hours for any issues, then deploy to additional systems in waves (perhaps 25%, then 50%, then 100%). Never deploy updates to all systems simultaneously. Monitor event logs and system performance after each wave before proceeding to the next.

Will Microsoft's update quality improve after this incident?

Improvement is unlikely without significant changes to how Microsoft develops and tests updates. The company would need to implement staged rollouts (testing with 1%, 5%, then 25% of users before broad deployment), extend testing windows before release, and improve monitoring of real-world hardware configurations. While Microsoft's response time to problems has improved, preventing problems in the first place requires systemic changes that haven't been announced.

What's the relationship between this bug and Secure Launch technology?

Secure Launch is a hardware-based security feature that uses virtualization to protect the Windows kernel. The January update modified how Windows interacts with the Secure Launch hypervisor during shutdown. The code change apparently caused a deadlock or timeout in systems with certain hardware and firmware combinations where the hypervisor failed to properly complete the shutdown sequence, keeping the CPU in a powered-on state as discussed by The Verge.

Can I roll back to the previous version of Windows 11 if this patch causes problems?

Yes, you can uninstall updates on Windows 11. Go to Settings > System > Optional features > More options > View update history, then click "Uninstall updates" and select the patch you want to remove. This will roll back the problematic update, though you'll lose whatever security fixes it included. This is why having a backup is essential before installing any major update.

Key Takeaways and Moving Forward

The January 2026 Windows 11 update incident was significant not because it was unprecedented, but because it illustrates a growing pattern: Microsoft's quality assurance processes aren't keeping pace with Windows's complexity.

The incident contained two distinct critical bugs that managed to pass through testing and reach hundreds of millions of users. One prevented systems from shutting down properly. The other broke remote desktop connections crucial for IT infrastructure. Both were serious enough to require an emergency out-of-band patch released within four days.

What made this particularly frustrating for Windows users and IT professionals is that it wasn't the first time. Similar incidents occurred in 2021 (Print Nightmare), 2023 (Outlook), and multiple times in 2024 and 2025. The pattern is clear: test more thoroughly, ship faster, break things, release emergency patches, repeat.

The technical root causes are understandable but not acceptable. Windows's scale and complexity make comprehensive testing difficult. Hardware diversity means the combination of systems Windows runs on is nearly infinite. Third-party drivers introduce unpredictable variables. Pressure to ship security patches quickly creates a schedule that conflicts with thorough testing.

But understanding the root causes doesn't make the outcome acceptable. Users who couldn't shut down their computers and administrators who couldn't access their remote systems weren't helped by explanations about testing limitations.

Moving forward, the responsibility falls to both Microsoft and Windows users/administrators.

Microsoft needs to:

- Implement staged rollouts that catch problems affecting even 1% of users before 100% rollout

- Extend testing windows and formalize post-mortem processes for bugs that escape

- Improve monitoring of real-world system configurations to catch compatibility issues earlier

- Balance the urgency of security patching with the need for thorough testing

Windows users and administrators need to:

- Stop treating Windows Update as something to install immediately

- Implement testing windows before deploying updates to critical systems

- Maintain backups so you can recover if updates break things

- Monitor Microsoft's known issues documentation and tech news before updating

The January 2026 incident will eventually fade from memory, replaced by the next update disaster. But it's a reminder that modern software, despite our best efforts, remains fundamentally fragile. One change in one component can cascade into system-wide failures affecting millions of users. Until Microsoft's testing processes and release procedures improve, we can expect similar incidents to continue occurring several times per year.

For now, the advice remains the same: install security patches, but don't install them immediately. Wait a week, check for reported issues, test in a non-critical environment first, and only then deploy to systems that matter. It's not ideal, but it's the pragmatic approach to managing Windows in an era of increasingly frequent update failures.

The broader lesson is sobering: as software complexity increases, our testing and quality assurance processes aren't scaling along with it. We're in an era where perfect software is impossible, and increasingly common update disasters are the cost of that impossible complexity.

Related Articles

- Windows 11 26H1 Update: Why Limited Snapdragon X2 Rollout Might Be Smart [2025]

- Why PCs Don't Need AI: Dell's Marketing Reality Check [2025]

- 5 Major Windows 11 Problems Microsoft Must Fix in 2026

- Windows 10's Legacy: What Microsoft Got Right (and How It Led to Windows 11 Problems) [2025]

- Windows 11 Needs to Drop AI Hype and Master the Basics [2025]

![Windows 11 Update Shutdown Bug: What Happened & How to Fix [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/windows-11-update-shutdown-bug-what-happened-how-to-fix-2026/image-1-1768755973414.jpg)