Yann Le Cun on Intelligence, Learning & the Future of AI Beyond LLMs

Introduction: The Godfather of Modern AI Charts a New Course

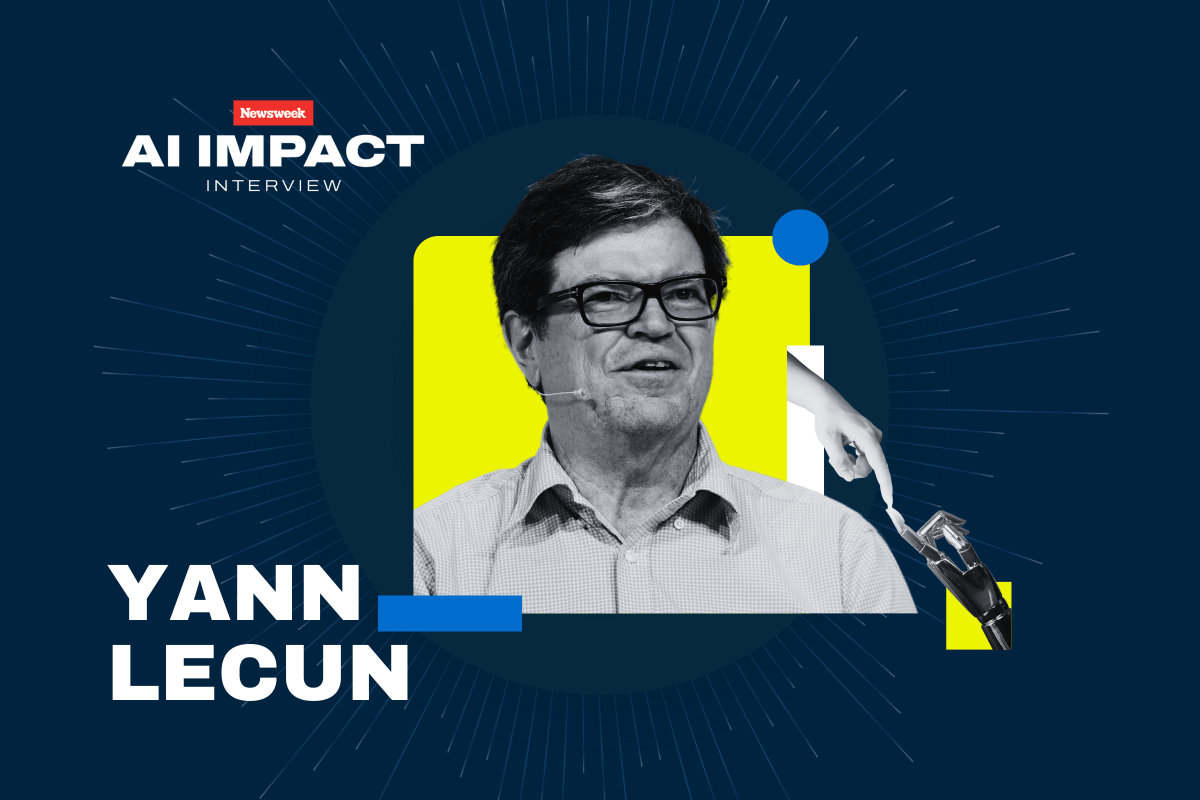

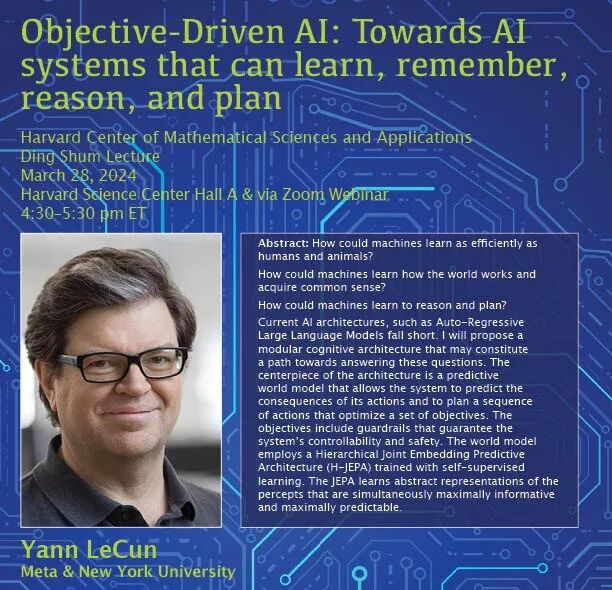

In the heart of Paris, nestled beside the Grand Palais where President Emmanuel Macron orchestrated an international AI summit to showcase French technological ambition, one of the computing world's most influential figures is making a pivotal career transition. Yann Le Cun, a Turing Award recipient and one of the three "godfathers" of deep learning alongside Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio, has announced his departure from Meta after years as the company's chief AI scientist. This moment represents far more than a personnel change—it signals a fundamental shift in how the field's most respected voice views the trajectory of artificial intelligence development.

For nearly two decades, Le Cun has been at the forefront of shaping the modern AI landscape. From pioneering convolutional neural networks that revolutionized computer vision to advancing deep learning architectures that became foundational to contemporary machine learning, his fingerprints appear across virtually every major breakthrough in the field. Yet today, standing at a crossroads in AI development, Le Cun is stepping away from one of tech's most powerful positions to pursue a radically different vision for machine intelligence—one that directly challenges the current Silicon Valley consensus around large language models.

The timing of Le Cun's transition is particularly significant. We find ourselves in a moment where generative AI has captured the popular imagination and dominated investment flows, with massive language models treated as the presumed pathway to artificial general intelligence. Yet Le Cun, whose scientific credibility is essentially unquestionable given his contributions to the field, is positioning himself to champion an alternative approach. This isn't a dismissal born of skepticism or envy, but rather the careful conclusion of someone who has spent decades thinking deeply about how intelligence actually emerges in both biological and artificial systems.

The fundamental thesis underlying Le Cun's new venture—Advanced Machine Intelligence Labs—rests on a deceptively simple but profoundly important observation: intelligence is not primarily about language, but about learning. This represents a critical correction to what he views as a dangerous detour in AI research. While large language models have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in generating human-like text and solving certain types of problems, Le Cun argues they remain fundamentally constrained by their architecture and training paradigm. To achieve genuine artificial general intelligence that matches or exceeds human cognitive capabilities, the field must develop systems that understand the physical world through observation, can plan and reason about future states, and maintain persistent memory of their experiences.

This article explores Le Cun's perspective on the future of AI, examines his critique of current approaches, analyzes his vision for what comes next, and considers what his departure from Meta means for both the company and the broader AI ecosystem. We'll examine the technical foundations of his proposed systems, the philosophical reasoning behind his positions, and the practical implications for anyone building AI systems or thinking about the field's trajectory.

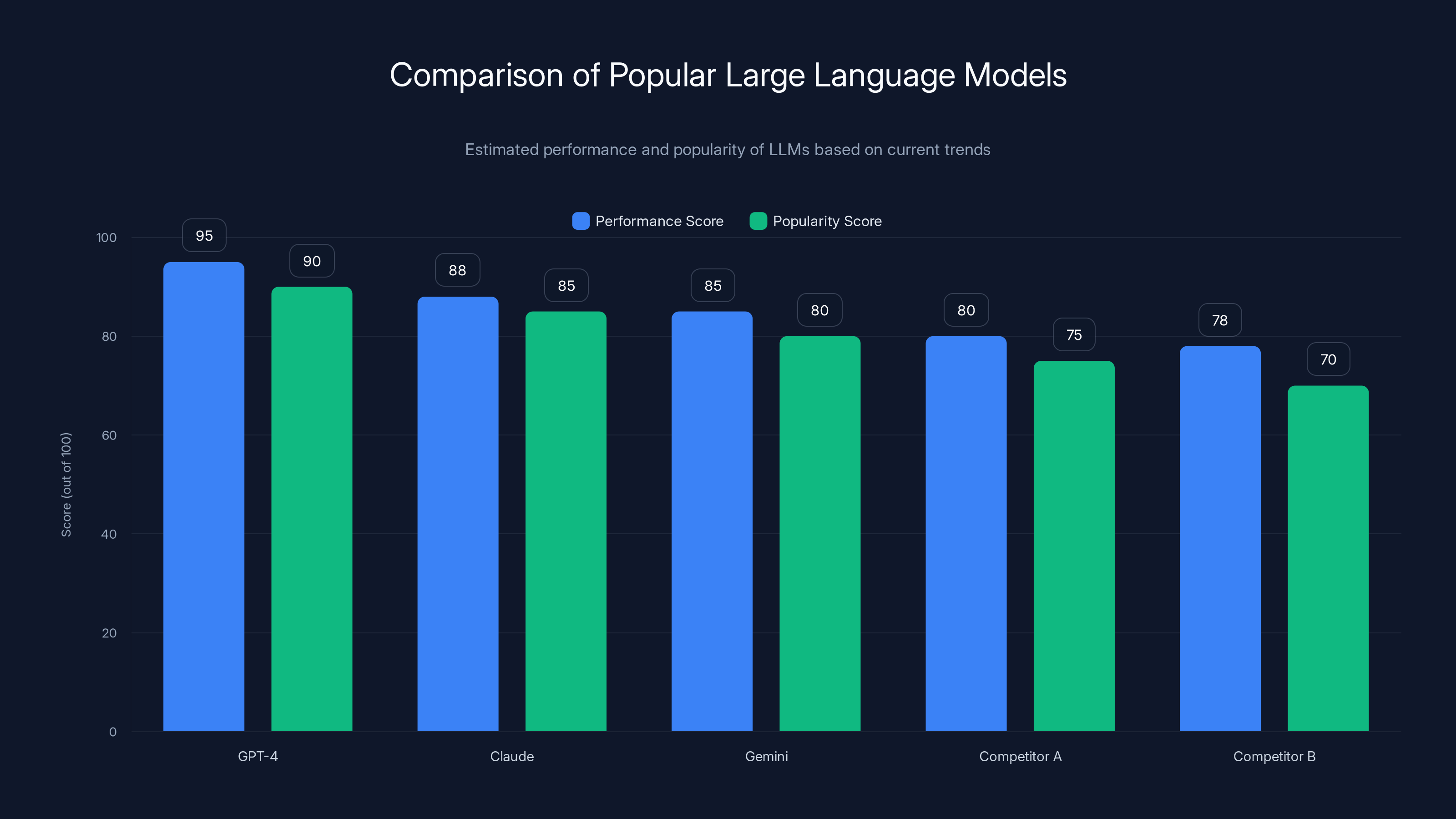

Estimated data shows GPT-4 leading in both performance and popularity among LLMs, with Claude and Gemini following closely. Estimated data.

Who is Yann Le Cun? A Brief Technical Biography

The Formation of an AI Pioneer

Born in 1960 in the suburbs of Paris, Yann Le Cun's fascination with intelligence and how it emerges began with a film. At eight or nine years old, he watched Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" and experienced something close to an intellectual awakening—a moment where the fundamental question of machine consciousness became real to him. This wasn't idle childhood daydreaming; it crystallized into a lifelong research agenda that would shape his entire career.

Le Cun's path into mathematics and computer science was not straightforward. A teacher once told him he was too poor at mathematics to study it at university, an assessment that revealed more about the limitations of traditional educational assessment than about Le Cun's actual capabilities. Rather than pursue pure mathematics, he directed his energies toward engineering, enrolling at the École Supérieure d'Ingénieurs en Électrotechnique et Électronique (ESIEE) in Paris during the 1980s.

The intellectual environment of that era was crucial to his development. Neural networks, the foundational technology underlying modern deep learning, had fallen into disrepute within the scientific community. Early iterations of artificial neural networks had failed to deliver on their promises, and the field was widely considered not just unpromising but actively taboo among serious researchers. This created an unusual opportunity: those working in neural networks during this period were often driven by genuine intellectual conviction rather than career advancement, creating tight-knit communities of researchers united by shared vision rather than herd mentality.

The Breakthrough Insight: Learning Over Language

The pivotal moment in Le Cun's intellectual development came when he was reading about a classic debate in cognitive science and developmental psychology between two giants of their respective fields: the linguist Noam Chomsky and the psychologist Jean Piaget. Chomsky's position was that human language capacity is fundamentally innate—that humans possess built-in biological structures specifically designed to acquire language. Piaget, by contrast, argued that while some basic structures are innate, the vast majority of human intelligence and language ability emerges through learning and interaction with the environment.

Le Cun's insight was radical: he concluded that Piaget was essentially correct, and that Chomsky's theory, while intellectually sophisticated and aesthetically appealing, simply did not match observable reality. More importantly, he recognized that this insight had profound implications for artificial intelligence. If human intelligence is fundamentally a learning phenomenon, then the path to artificial intelligence must also be fundamentally rooted in learning—not in pre-programmed rules, not in innate structures, but in the capacity to learn from experience.

This seemingly simple conclusion became the foundation for decades of work. It led him to conclude that "intelligence really is about learning," a statement that sounds obvious once articulated but that required enormous intellectual courage to accept fully in the context of 1980s AI research, where expert systems and symbolic reasoning still dominated the field.

Contributions That Shaped Modern AI

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Le Cun made successive technical contributions that would eventually make deep learning the dominant approach in artificial intelligence. He developed convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a breakthrough architecture specifically designed to handle the structure present in visual data. Rather than treating images as unstructured collections of pixels, CNNs exploit the spatial structure of images by using local connectivity patterns and weight sharing, dramatically reducing the number of parameters needed and making training more efficient.

These networks became the foundation for virtually all modern computer vision systems. From facial recognition to medical image analysis, from autonomous vehicle perception to satellite image interpretation, the fundamental architecture that powers these systems traces directly back to Le Cun's work in the 1980s. The practical validation came in 1998 when his team deployed a CNN to read handwritten digits on checks—a real-world application that demonstrated that neural networks could solve actual problems, not just serve as theoretical curiosities.

Beyond specific architectures, Le Cun also contributed to the theoretical understanding of deep learning, developed practical training techniques, and championed the use of gradient descent and backpropagation when much of the field was skeptical. His work at Bell Labs and later at Facebook (now Meta) established him not just as a brilliant researcher but as someone with the rare combination of theoretical insight and practical engineering sense.

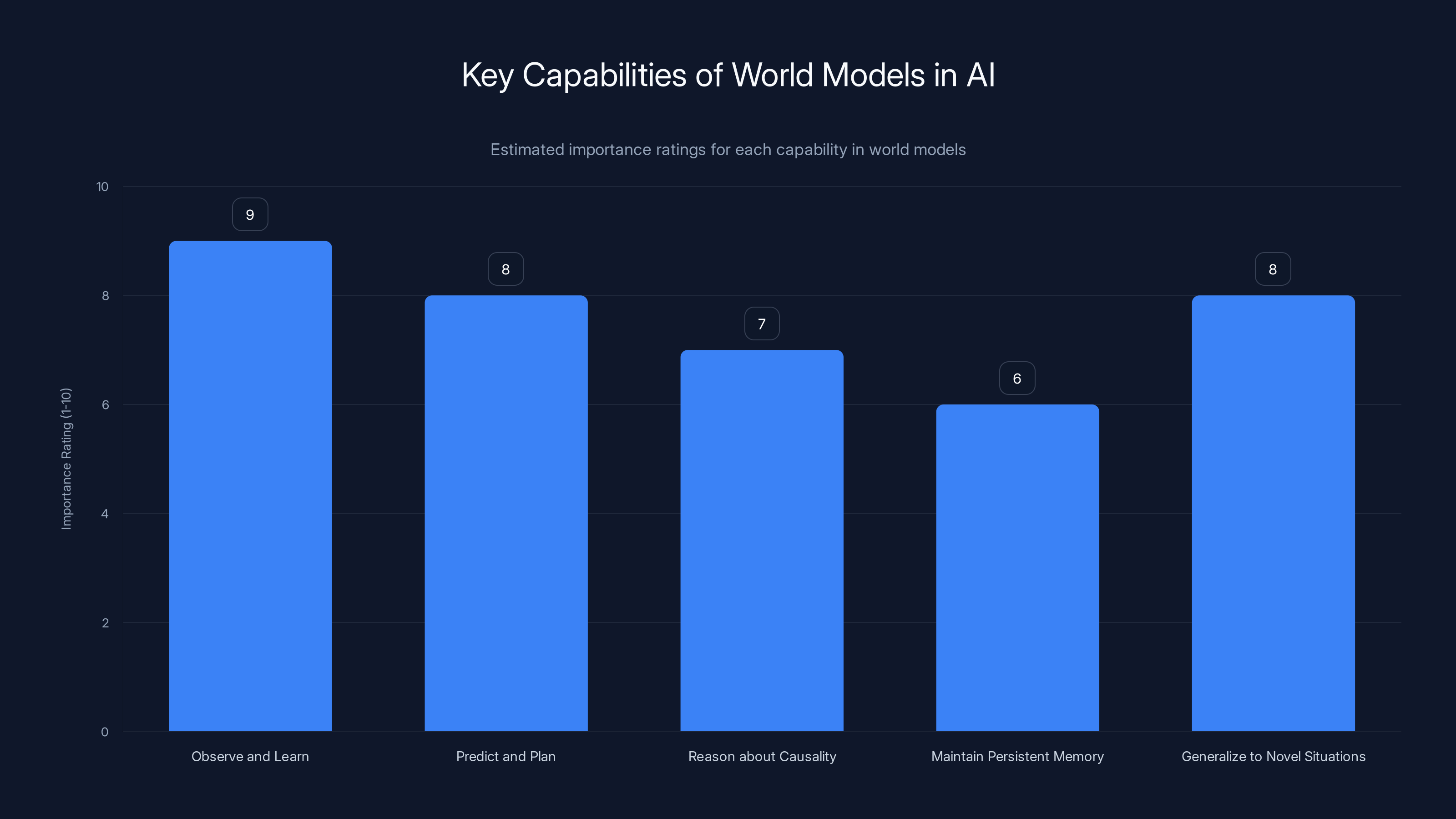

This chart estimates the relative importance of various capabilities in world models for AI, highlighting 'Observe and Learn' as the most critical feature. Estimated data.

The Current State of AI: LLMs and Their Limitations

The LLM Dominance and Its Appeal

The past few years have witnessed an extraordinary concentration of attention, investment, and research effort around large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4, Claude, Gemini, and their various competitors. These systems represent a genuinely impressive engineering achievement: transformer-based architectures trained on vast quantities of text data can generate coherent, contextually appropriate, and often surprisingly insightful responses to natural language queries. The capabilities demonstrated by these systems have astonished even researchers who understood the underlying technology.

The appeal of LLMs is understandable. They work, demonstrably and at scale. They can be deployed relatively straightforwardly as chat interfaces. They generate revenue through API access. They capture public imagination in ways that make them natural focal points for investment. Perhaps most importantly for the AI community, they've shown that scaling—making models much larger and training them on more data—produces capabilities that were not obviously present in smaller systems. This has created a narrative in which the path to AGI (artificial general intelligence) is simply a matter of continued scaling.

For venture capitalists and large tech companies, LLMs represent a clear business opportunity with existing customers, measurable metrics, and a plausible path to profitability. This creates powerful economic incentives that reinforce the focus on language models, independent of whether they represent the optimal research direction.

Le Cun's Fundamental Critique

Yet Le Cun's critique of this dominance is not born from pessimism about what LLMs can do, but from a sober assessment of what they cannot do. He acknowledges straightforwardly that large language models are useful. They solve real problems. They generate genuine value. But he contends that they are fundamentally constrained by their architecture and training paradigm in ways that make them poor candidates for achieving artificial general intelligence.

The core limitation is deceptively simple: language models understand language, not the world. They are trained to predict the next token in a sequence based on previous tokens, using only the statistical patterns present in text. This creates systems that are remarkably good at certain linguistic tasks—summarization, translation, question answering within the bounds of what can be expressed in language—but that lack genuine understanding of physical causality, spatial reasoning, or temporal dynamics.

Consider a seemingly simple example: imagine describing to a language model a scenario where you drop a cup of coffee on a hardwood floor. The model can generate text describing what might happen, and the text would sound plausible to a human reader. But the model doesn't actually understand why coffee spills in a particular way, how liquid dynamics work, or how the specific properties of hardwood affect the outcome. It's matching patterns in its training data that relate to similar scenarios.

This distinction between linguistic plausibility and genuine understanding becomes increasingly important when considering more complex domains. A language model might be able to describe how a chemical reaction works, but it hasn't actually observed chemicals interacting. It might explain how to repair an engine, but it hasn't developed intuitions about mechanical systems through interaction and observation. These kinds of physical intuitions—what philosophers call "common sense"—emerge from embodied interaction with the world, not from reading about the world.

The Scaling Plateau and Emergent Limitations

Le Cun argues that the current trajectory of LLM development is hitting fundamental limitations that scaling alone cannot overcome. While larger models do demonstrate improved performance on many benchmarks, the improvements follow predictable scaling laws that are well understood, and the gains are increasingly marginal relative to the computational costs. More importantly, the kinds of capabilities that emerge from scaling are largely variations on what smaller models can already do—they become better at retrieving and recombining patterns from training data, but they don't develop genuinely new cognitive capacities.

This is not to say LLMs are useless. For many practical applications—customer service, content creation, code generation, information retrieval—they are genuinely valuable tools. But for the problem of creating artificial general intelligence that can reason, plan, explore unfamiliar domains, and understand novel situations, the limitations of pure language-based systems become disqualifying.

The fundamental issue is that language is a bottleneck. Human intelligence did not emerge from reading text; it emerged from millions of years of embodied interaction with the physical world. Humans learn through observation, experimentation, and active engagement with their environment. Language is something we built on top of this foundational understanding—it's a tool for communicating about our knowledge of the world, not the primary mechanism through which we acquire that knowledge.

The World Model Approach: V-JEPA and Advanced Machine Intelligence

What is a World Model?

Rather than constraining AI systems to language, Le Cun proposes developing world models—AI systems capable of learning from observation (particularly from video and spatial data) to develop an internal representation of how the physical world works. The key insight is that a world model should be able to:

- Observe and learn: Watch videos and spatial data to understand patterns in how the world changes

- Predict and plan: Use its understanding to predict future states and to plan sequences of actions that achieve goals

- Reason about causality: Understand not just correlations but causal relationships between actions and outcomes

- Maintain persistent memory: Remember past experiences and integrate them into decision-making

- Generalize to novel situations: Apply learned principles to situations that differ from training experience

This approach draws inspiration from how human intelligence actually develops. Infants don't learn about the world primarily through language; they learn through observation and experimentation. A baby learns about gravity not by reading a physics textbook but by dropping objects and observing what happens. They develop an intuitive understanding of object permanence, spatial relationships, and basic physics through direct interaction.

A world model is essentially an attempt to replicate this kind of learning mechanism in artificial systems. Rather than training on text, the system would be trained on video, observing how the world changes over time and learning to predict those changes based on the current state and any actions taken.

V-JEPA: Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture

Le Cun and his team at Meta developed a specific architecture called V-JEPA (Video Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture) as a concrete implementation of the world model concept. The architecture works by:

-

Encoding observations into embeddings: Converting raw video frames or sensor data into a compressed representation that captures the essential information

-

Learning predictive mappings: Training the system to predict future embeddings based on current embeddings and action information

-

Masking and context: Using masked prediction (similar to masked language models, but applied to spatiotemporal data) where parts of the video are hidden and the system must predict them

-

Action conditioning: Incorporating information about what actions were taken or what goals are being pursued, allowing the model to predict how the world will change given specific interventions

The elegance of this approach is that it doesn't require labeled data about what's happening in videos. The system doesn't need humans to annotate "this is a person picking up an object" or "this is the object falling to the ground." Instead, it learns entirely through self-supervised learning—by predicting parts of the video from other parts, it develops an understanding of the underlying dynamics.

Advantages Over Language-Based Systems

World models offer several profound advantages over language-based approaches:

Physical intuition: A system trained on video learns actual physics, not just descriptions of physics. It develops intuitions about how objects move, how friction works, how liquids behave—not as abstract concepts but as predictive expectations.

Fewer training examples needed: Humans and animals don't need millions of examples to learn about the world. A child observes gravity working once in dozens of different contexts and immediately generalizes. A world model can similarly develop broad understanding from relatively limited experience.

Transferability: Understanding learned from one domain can transfer to novel situations. A robot arm trained to manipulate objects in one environment can apply those principles in a different environment. This kind of transfer is difficult for language models because they're not learning about causal structure—they're learning statistical patterns in text.

Planning and reasoning: Once a system has a world model, it can use that model to plan—to imagine different sequences of actions and their consequences, and to select actions that lead toward desired goals. This is planning with foresight, not just pattern matching.

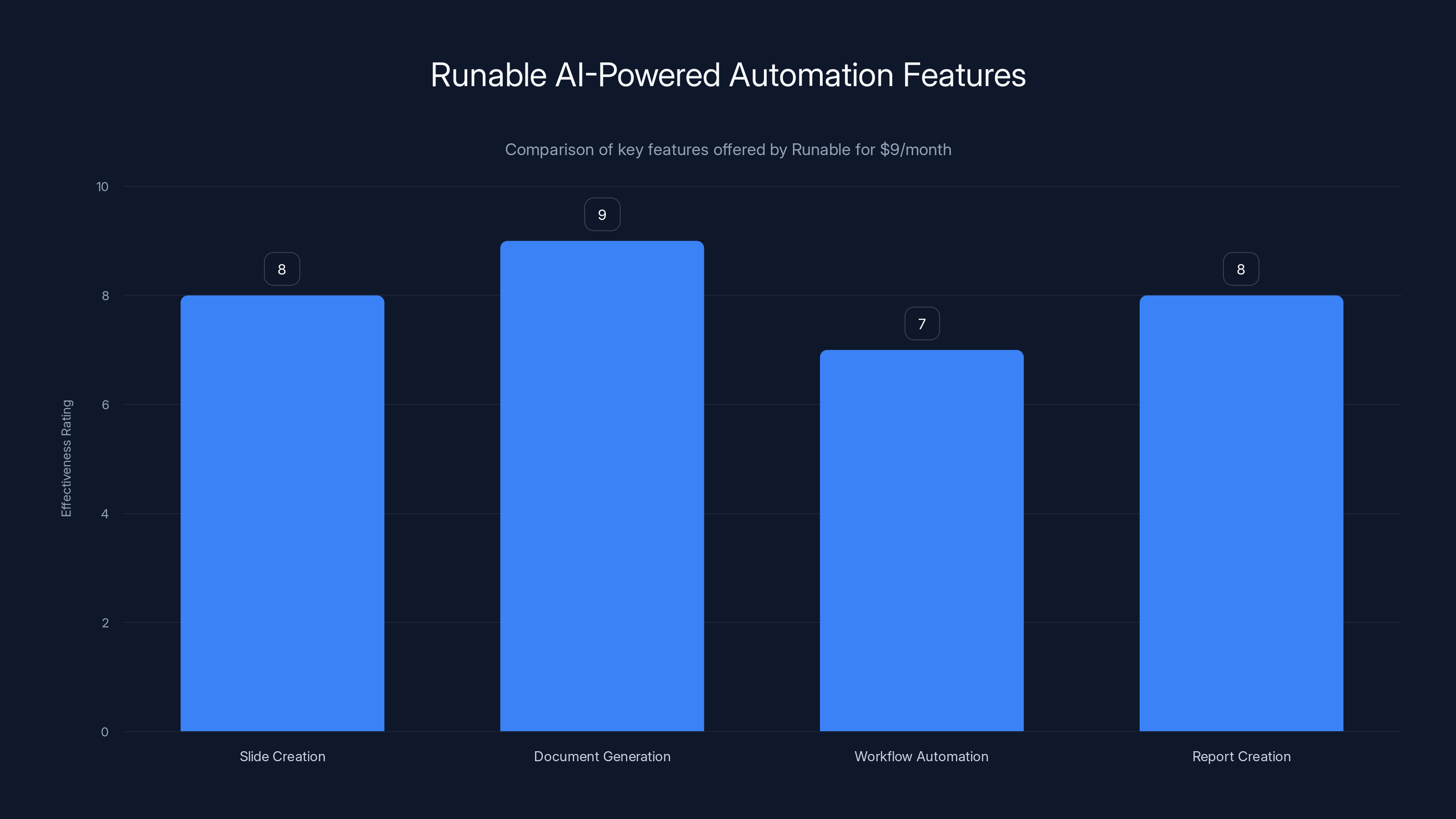

Runable provides effective AI-powered automation tools for content and workflow tasks, rated highly for document generation and slide creation. Estimated data.

The Philosophy Behind Le Cun's Vision

Intelligence as an Emergent Property of Learning

Underlying Le Cun's technical proposals is a coherent philosophical position about what intelligence actually is. In his view, intelligence is fundamentally an emergent property of learning systems that interact with their environment. It's not something programmed in—it emerges from the interaction between:

- A learning mechanism: The ability to update internal representations based on experience

- Rich environmental feedback: Consequences of actions that provide information about the structure of the world

- Temporal structure: The ability to learn from sequences of observations and to predict into the future

This position has deep roots in cognitive science and developmental psychology, but it has been somewhat marginalized in recent years as the field focused on pattern matching in text. Le Cun is essentially arguing that the field needs to return to first principles and think carefully about what intelligence actually requires.

From this perspective, the extraordinary capabilities of large language models in text generation are a kind of sophisticated pattern matching—and while pattern matching is certainly part of intelligence, it's not the whole story. To get to genuine intelligence, you need systems that can learn causal structure, that can plan, that can generalize to completely novel domains, and that can integrate knowledge from multiple modalities and types of experience.

Learning as the Fundamental Principle

Le Cun's statement that "intelligence really is about learning" is not just a slogan but the summary of a deep commitment to understanding intelligence scientifically. He means that:

- Intelligence is not fixed or pre-programmed

- Intelligence emerges from the capacity to extract patterns from experience

- Different types of learning (supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement) combine to produce sophisticated behavior

- The structure of the learning mechanism matters profoundly for what can be learned

This learning-centric view has direct implications for how AI systems should be built. Rather than focusing on the specific task (e.g., predicting the next word), the focus should be on building systems that learn to learn—that develop general principles from observation that can be applied across domains.

Bridging Neuroscience and AI

A recurring theme in Le Cun's thinking is the close relationship between how biological brains work and how artificial intelligence should be structured. This isn't naive biological copying—the brain is far too complex for direct replication—but rather extracting principles from neuroscience that should guide AI architecture.

From neuroscience, we know that:

- Most of the brain is devoted to unsupervised learning—learning the structure of the world without explicit labels

- The brain learns through self-supervised mechanisms—predicting consequences of actions, using context to understand meaning

- Intelligence is fundamentally embodied—rooted in interaction with a physical environment

- Learning is continuous and incremental—the brain doesn't reset and retrain from scratch; it learns throughout life

Current AI systems, particularly large language models, are somewhat divorced from these principles. They're trained on static datasets with explicit objectives, they don't update their weights after training, and they're not grounded in physical interaction. A learning-based approach to AI would bring artificial systems closer to how biological intelligence actually works.

Le Cun's Departure from Meta: What It Means

The Decision and Its Timing

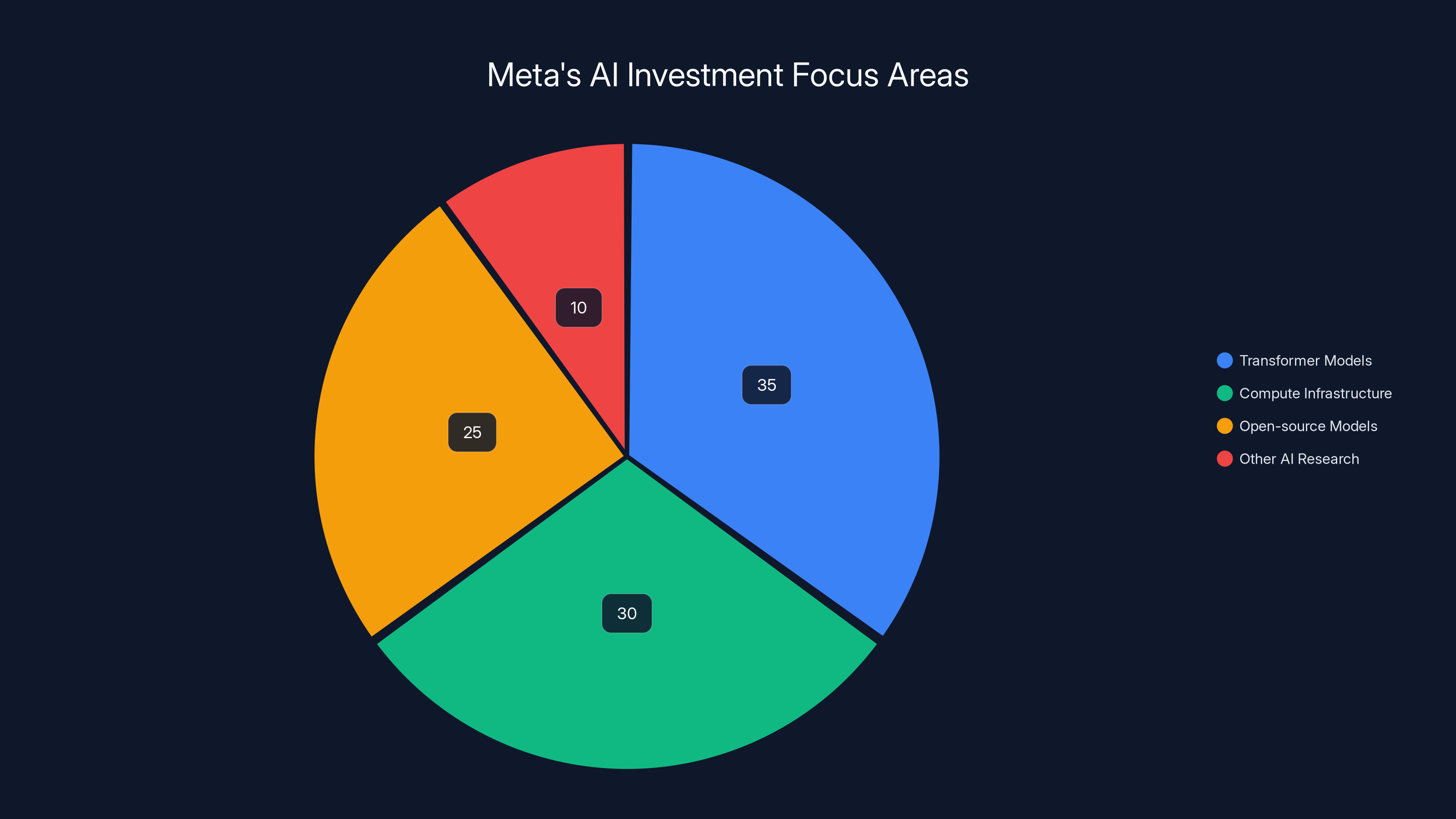

Le Cun's announcement that he would step down from his role as chief AI scientist at Meta sent ripples through the tech industry. The timing was particularly notable: Meta has invested billions in AI research, including the development of transformer models, the funding of large-scale compute infrastructure, and the open-sourcing of LLa MA (now Llama) models that have become widely used throughout the industry.

The decision to leave was not made lightly, and it reflects a conviction about the direction the field needs to take that apparently diverged from Meta's current priorities. Le Cun had publicly criticized the focus on large language models as representing a "dead end" for achieving artificial general intelligence, which is a remarkable statement for someone working at one of the companies most heavily invested in LLM development.

In interviews, Le Cun has acknowledged the awkwardness of his position: "I'm sure there's a lot of people at Meta who would like me to not tell the world that LLMs basically are a dead end when it comes to superintelligence." This candor reveals the genuine tension between his conviction about the right research direction and the strategic focus of his employer.

Why a CEO Cannot Also Be a Visionary Researcher

Crucially, Le Cun has stated he will not serve as CEO of his new venture. Instead, he'll take the role of executive chair, which allows him to maintain the freedom to pursue research and intellectual direction without being consumed by management responsibilities. His reasoning is straightforward and self-aware: "I'm a scientist, a visionary. I can inspire people to work on interesting things. I'm pretty good at guessing what type of technology will work or not. But I can't be a CEO. I'm both too disorganised for this, and also too old!"

This is an important insight about the different skill sets required in science and business. Running a company requires discipline around budgets, timelines, quarterly results, and stakeholder management—exactly the kinds of structured, process-oriented activities that can constrain creative research. Having led large AI labs at both Bell Labs and Meta, Le Cun understands that his greatest value to the organization would be in defining research direction and intellectual leadership, not in operational management.

The decision reflects a mature understanding of comparative advantage: bring in someone who has the operational skills and management discipline to be CEO, while maintaining personal freedom to pursue the research vision that motivated creating the company in the first place.

Advanced Machine Intelligence Labs and Future Direction

Le Cun's new venture, Advanced Machine Intelligence Labs (reported to be led by Alex Le Brun, co-founder of the healthcare AI startup Nabla), represents an attempt to build an organization specifically focused on the vision of developing intelligent systems through learning mechanisms rather than scaling language models. The company's focus on the word "Intelligence" rather than "Learning" or "Language" signals the ambitious scope of the work.

The decision to build this company in France, with connections to the French government and the ecosystems built around Paris, also reflects a strategic choice. France has been positioning itself as a center for AI research and development, and Le Cun's return (he has maintained ties to Paris throughout his career) represents a significant intellectual resource for the country.

What the new venture signals is that Le Cun is willing to place significant personal capital—his reputation, his time, his intellectual energy—behind a vision fundamentally different from the current industry consensus. This is a meaningful vote of confidence in the learning-based, world-model-centric approach to AI.

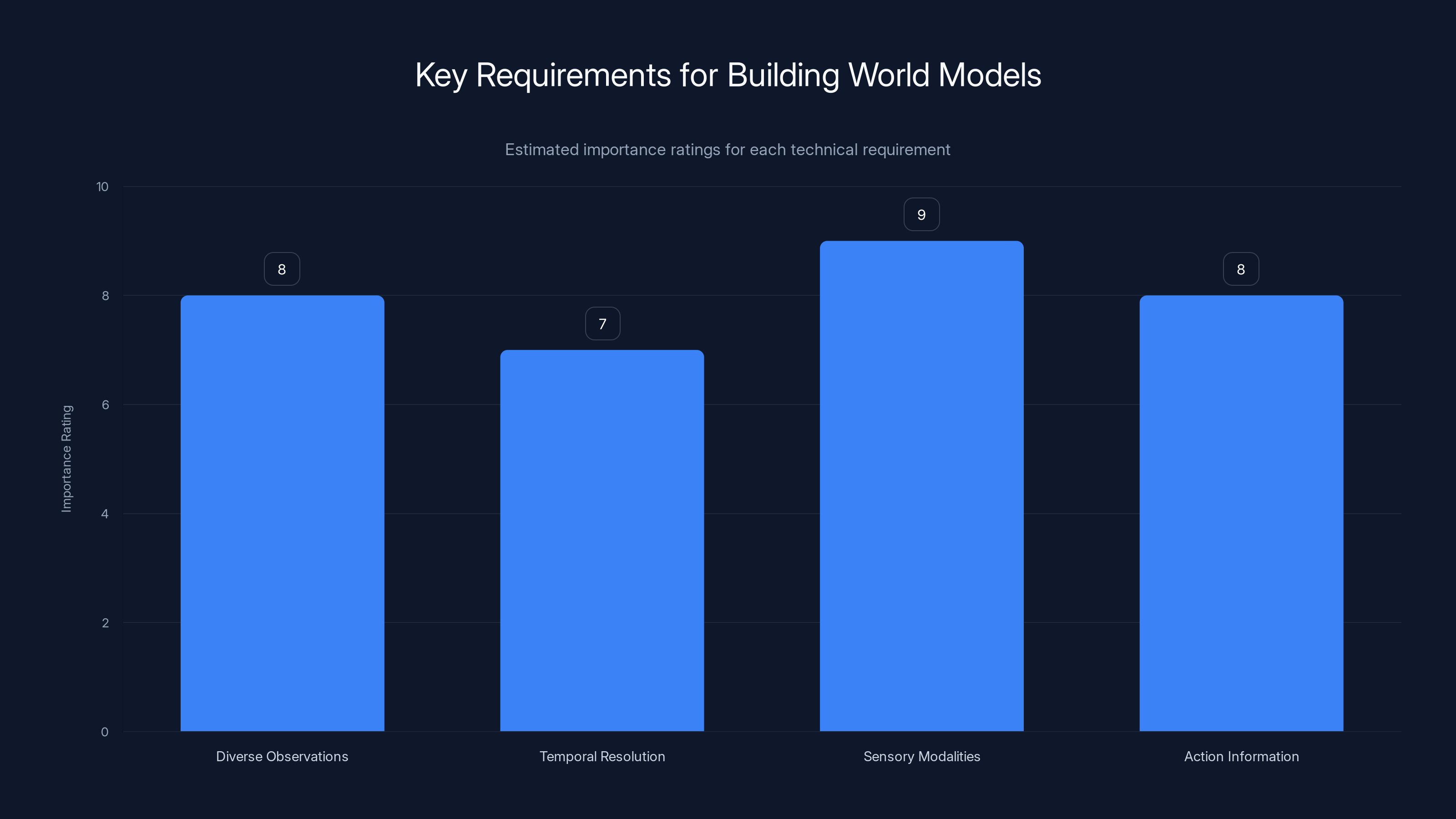

Estimated data shows that multiple sensory modalities and diverse observations are crucial for developing effective world models.

The Technical Requirements for World Models

Data Requirements and Challenges

Building effective world models requires addressing several technical and practical challenges. First and foremost is the question of data: what does a system trained on videos or sensor data actually need to develop genuine understanding?

One key insight from Le Cun's work is that the amount of data required might be lower than many assume. A system that learns to predict should be able to do so relatively efficiently—much like humans don't need billions of examples to understand physics. However, the system does need:

- Diverse observations: Examples from many different environments and contexts

- Sufficient temporal resolution: Smooth video or sensor data that captures the dynamics of change

- Multiple sensory modalities: Visual information, potentially combined with proprioceptive information (sense of body position and movement)

- Relevant action information: Understanding what actions were taken and what their consequences were

The challenge is collecting and organizing such data in ways that are useful for training. Unlike text data, which exists in abundance on the internet, video data with sufficient detail and diversity requires more careful curation. And unlike language, where sequence length is naturally limited (sentences have bounded length), video understanding requires processing long temporal sequences, which creates computational challenges.

The Compute Question

A persistent question about world models is whether they require more or less computation than language models. This depends on many factors:

- Model size: A world model might be similarly large in parameter count to a language model

- Training efficiency: Self-supervised learning on video might be more sample-efficient than language modeling

- Inference requirements: Using a world model for planning might require less computation than generating long text sequences

- Updating and adaptation: A world model that can continuously update based on new observations might require different computational patterns than frozen language models

Le Cun's perspective is that computational efficiency matters less than capability. If world models enable systems to learn more effectively and transfer learning to new domains more successfully, then the computational cost is justified.

Integration with Other Systems

A complete intelligent system would likely need to integrate world models with other components:

- Memory systems: Episodic memory that stores important experiences, semantic memory that stores learned concepts

- Language understanding: Ability to parse linguistic descriptions and relate them to world model understanding

- Goal and reward specification: Mechanisms for incorporating objectives and evaluating whether goals have been achieved

- Planning mechanisms: Systems that use the world model to imagine future trajectories and select promising action sequences

- Continual learning: Ability to update the world model based on new experiences without forgetting previously learned knowledge

No single component is sufficient for artificial general intelligence. The challenge is understanding how these components interact and what properties the overall system needs to possess.

The Broader AI Research Context

Where Does Le Cun's Vision Fit?

It's important to understand Le Cun's position not as an isolated perspective but as one important voice in a broader debate about the future of AI. The field contains several competing perspectives on how to progress toward artificial general intelligence:

The scaling hypothesis: The view that current approaches (particularly large language models) will eventually lead to AGI through continued scaling. Proponents argue that emergent capabilities appear with scale and that we simply need to build larger models.

The architecture innovation perspective: The view that current architectures have fundamental limitations and that progress requires developing new neural network designs. Le Cun's world models fall into this category.

The embodied AI perspective: The view that intelligence requires robotic embodiment and physical interaction. This perspective emphasizes robotics and real-world testing.

The symbolic AI revival: A perspective that neural networks need to be combined with more structured, symbolic reasoning approaches.

The neuroscience-inspired approach: The view that closer attention to how biological brains actually work should guide AI architecture decisions.

Le Cun's position is perhaps closest to the combination of architecture innovation and neuroscience-inspired approaches. He's not saying scaling is worthless, but rather that scaling alone, applied to language-based systems, won't get us to genuine AGI.

Why This Debate Matters

These different perspectives have profound implications for research funding, corporate strategy, and the actual trajectory of AI development. If the scaling hypothesis is correct, then the current focus on training ever-larger language models is exactly right. If Le Cun's perspective is correct, then vast resources are being directed toward a dead end, and the field should reallocate attention to developing world models and learning-based systems.

This is not a debate about competing commercial products or services—it's a debate about what research direction is most likely to lead toward genuine artificial general intelligence. The practical consequence is that billions of dollars are being allocated based on different assumptions about this question.

Meta's AI investments are heavily focused on transformer models and compute infrastructure, with significant resources also allocated to open-source models. (Estimated data)

Practical Implications: What This Means for AI Development

For Researchers and Laboratories

Le Cun's perspective suggests several research directions that deserve increased attention:

Self-supervised learning on multimodal data: Developing methods to learn from video, audio, and sensor data without requiring explicit labels. This is computationally challenging but potentially very rewarding.

Planning and reasoning over learned models: Once a world model exists, how can it be used for planning? This requires developing algorithms that can imagine futures and evaluate their desirability.

Continual learning and adaptation: Rather than training a fixed model and deploying it, developing systems that continuously update based on new observations.

Robustness and generalization: Understanding why world models might generalize better than language models to novel situations and how to build robustness into the learning process.

Integration of language and world models: How can linguistic understanding be integrated with physical world understanding? How do they inform each other?

For Product Development and Deployment

For companies building AI products, Le Cun's perspective has some immediate implications:

Current language models remain useful: The critique is not that language models are worthless, but that they have fundamental limitations. They're still useful tools for many applications.

Multimodal systems: There's value in building systems that combine language understanding with visual understanding and physical reasoning.

Robotics and embodiment: If intelligence requires interaction with the physical world, then robotics becomes a critical area for AI development, not a side issue.

Data diversity: Rather than focusing solely on text scale, collecting and curating diverse, high-quality datasets across modalities becomes important.

For Policy and Governance

From a policy perspective, Le Cun's emphasis on understanding how intelligence actually works has implications:

Safety and alignment: If the path to AGI is through learning-based world models rather than scaling language models, the safety challenges might be somewhat different. A system learning to understand physics is differently aligned than a system learning to predict text.

International competition: The focus on AI safety and alignment has sometimes treated it as orthogonal to capability research. Le Cun's perspective suggests that building the right kinds of systems is itself a form of alignment—systems that learn through interaction might have better properties than systems that just predict text.

Compute and resources: If world models require different computational patterns than language models, resource allocation for AI research might shift.

Le Cun's Personal Intellectual Journey

From Musician to Computer Scientist

An interesting aspect of Le Cun's background is his involvement with music. As a young person, he played Renaissance instruments including the crumhorn—a somewhat obscure wind instrument used in Renaissance dance music. He even played in a Renaissance dance music band, suggesting someone with a musical sensibility and appreciation for how different elements combine to create complex wholes.

This musical background may have influenced his approach to building complex systems. Music is fundamentally about patterns, about how different elements can be combined and orchestrated to create something coherent and meaningful. A computer vision system is not unlike a musical composition—different elements (features, representations, learning mechanisms) must be carefully combined to create something that works.

Model Aeronautics and the Love of Building

Le Cun's father was an aeronautical engineer and inventor, and he instilled in his son a love of building and tinkering. Young Yann spent time constructing model airplanes, learning the practical skills of engineering—how to design, build, test, and iterate on physical systems. This hands-on engineering sensibility is evident in his approach to AI: he doesn't just theorize about what systems should be like, he builds them and tests them.

This background in physical engineering is particularly relevant to his current direction. The focus on world models and physical understanding isn't abstract theorizing—it comes from someone with genuine engineering experience and appreciation for how the physical world actually works.

The Convergence of Interests

What's remarkable about Le Cun's trajectory is how his various intellectual interests converge. His childhood fascination with artificial intelligence (sparked by "2001: A Space Odyssey"), his musical training, his engineering background, his psychological interest in how intelligence develops—all of these feed into his current vision for how AI should be built.

This is not someone who stumbled into AI research for commercial reasons. This is someone with a genuinely integrated intellectual vision, who has devoted decades to thinking deeply about the problem and who is now making significant personal sacrifices (departing from a position of enormous influence and comfort) to pursue what he believes is the right direction.

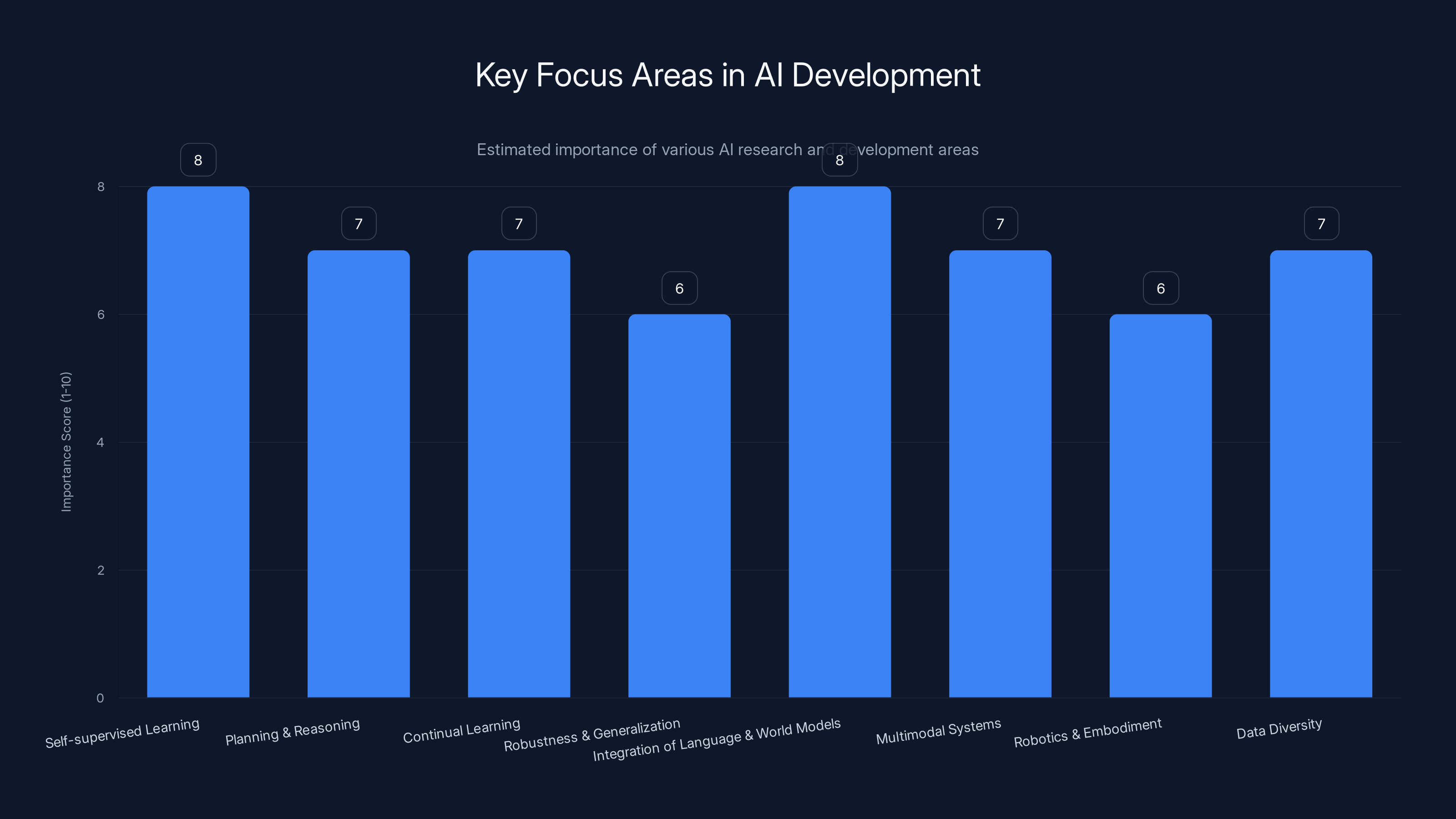

The chart highlights the estimated importance of various AI research and development areas. Self-supervised learning and integration of language with world models are considered top priorities. Estimated data.

Critical Questions and Open Problems

The Knowledge Problem

One persistent challenge with world models is understanding what kind of knowledge they can actually capture. A language model can store facts explicitly (though not perfectly): facts about people, places, historical events, scientific knowledge. Can a world model capture this kind of knowledge as effectively?

The answer is probably yes, but in a different form. A world model would understand facts through their physical implications. It would understand "Napoleon died in 1821" not as an abstract fact but through understanding history as a causal sequence of events. Whether this kind of implicit factual knowledge is sufficient for all purposes remains an open question.

The Scaling Question

Le Cun argues that language model scaling is hitting fundamental limits. But world models might also hit scaling limits. How much does a world model improve with scale? At what point do the gains diminish? These are empirical questions that can only be answered through building and testing systems.

The Embodiment Requirement

A theoretical question underlies world model research: does genuine intelligence require embodiment? Can a system that only observes video develop true understanding, or is there something essential about being able to act in the world and observe the consequences? This is both a philosophical and practical question with significant implications.

The Generalization Challenge

Humans can see something happen a handful of times and generalize to completely novel situations. Can world models do this? If a world model is trained in one environment, can it transfer to a radically different one? These transfer learning challenges are among the hardest problems in machine learning.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Working on This?

Academic Research Groups

Le Cun is not alone in pursuing world model approaches. Research groups at various universities have been exploring similar ideas:

- UC Berkeley: Drew Bagnell and others working on learning from video and robotic interaction

- MIT: Antonio Torralba's group exploring visual understanding and physical reasoning

- CMU: Various robotics labs working on learning from observation

- Deep Mind and Google: Published research on video prediction and world models

There's a substantial research community exploring these directions, though it's smaller than the large language model community.

Industry Investments

Beyond Le Cun's venture, other companies have been investing in multimodal learning and robotics:

- Tesla: Developing vision-based world models for autonomous driving

- Boston Dynamics: Working on robotic learning and physical understanding

- Open AI: Despite focus on language models, also exploring multimodal systems

- Deep Mind/Google: Exploring learning from video and robotics applications

The difference with Le Cun's venture is the explicit, primary focus on world models as the central research direction rather than one component among many.

Runable and AI-Powered Automation: An Alternative Approach

While Le Cun's vision focuses on fundamental AI research toward artificial general intelligence, there's an important intermediate layer worth considering: how can current AI capabilities be leveraged to solve practical problems for developers and teams today?

Runable, an AI-powered automation platform, represents a different approach to applying AI: rather than focusing on building systems that understand the world through learning, it focuses on automating specific workflows and content generation tasks that teams face regularly. For developers building applications, content creators managing multiple projects, or teams handling routine documentation, Runable's AI agents for automated slide creation, document generation, and workflow automation offer immediate practical value.

The distinction is important: Le Cun's vision is about fundamental research aimed at AGI decades hence. Runable addresses the immediate present—how can AI agents help developers and teams be more productive right now? For $9/month, teams can access automated content generation, report creation, and workflow optimization without waiting for world models to mature.

These are not competing visions but rather different points on the timeline. Le Cun's work represents the long-term research direction for AI, while products like Runable represent practical applications of current AI capabilities to real business problems. A developer might use Runable to automate documentation while following Le Cun's research on world models to understand where AI is heading.

The Future Trajectory: What Comes Next?

The Next Five Years

In the near term, we should expect several developments:

Continued LLM capability expansion: Despite Le Cun's critique, language models will continue to improve. They may plateau in some dimensions, but new applications and capabilities will likely emerge.

Increased investment in world models: Le Cun's departure from Meta and the creation of Advanced Machine Intelligence Labs signals that serious research efforts and capital will flow toward world model development.

Multimodal system integration: Systems combining language models with visual understanding and reasoning about physical systems will become increasingly common.

Robotics acceleration: If world models require embodied interaction, robotics research will receive increasing attention and resources.

Safety and alignment focus: Regardless of which research direction proves most fruitful, the AI community will intensify focus on ensuring systems are safe and aligned with human values.

The Long-Term Implications

If Le Cun's perspective proves correct and world models become the primary path to AGI, the landscape of AI research and application will shift dramatically. Companies that have invested billions in language model infrastructure might need to reallocate resources. Research groups that have focused on scaling might need to pivot toward learning mechanisms. The entire ecosystem could undergo a significant transformation.

Conversely, if the scaling hypothesis proves correct and language models continue to improve dramatically through pure scale, Le Cun's vision might represent an interesting research direction but not the primary path to AGI. Both trajectories are possible, and the field doesn't yet know which will prove more fruitful.

What's certain is that this fundamental disagreement among the field's most respected researchers will continue to shape AI research and development for years to come.

Conclusion: The Vision of a Lifetime

Yann Le Cun's departure from Meta and transition to leading a new venture focused on world models and Advanced Machine Intelligence represents far more than a career move. It's the culmination of a lifelong intellectual journey rooted in a fundamental conviction about how intelligence works: intelligence emerges from learning, not from pre-programmed rules or pure pattern matching. To build truly intelligent artificial systems, we must create mechanisms for learning from observation, for understanding causality, for planning with foresight, and for transferring knowledge to novel domains.

This conviction, developed over decades and rooted in careful thinking about cognitive science, neuroscience, and how biological intelligence actually emerges, positions Le Cun as a counterweight to the current industry consensus around scaling language models. He doesn't dismiss the value of these systems—he acknowledges their utility—but he argues that they represent a kind of dead end for the pursuit of artificial general intelligence.

The remarkable aspect of Le Cun's move is not that he has a different opinion; many researchers have alternative views. It's that he's willing to place significant personal capital—his reputation, his time, his energy—behind that conviction by leaving one of the most influential positions in AI to pursue it. This signals genuine commitment to the research direction, not casual theorizing.

For the broader AI field, Le Cun's perspective and actions serve as an important reminder to think carefully about fundamental principles rather than being swept along by current hypes and massive capital flows. The fact that the person who pioneered the deep learning revolution is now arguing that the current focus on language models is insufficient for achieving AGI deserves serious consideration, even from those who disagree.

The next several years will be crucial for testing these competing visions. Will world models prove to be the key missing ingredient for achieving artificial general intelligence? Or will continued scaling of language models, combined with other techniques and architectures, prove sufficient? Will the integration of language understanding with physical reasoning through world models unlock new capabilities? These are not idle academic questions—they will shape billions of dollars in investment and the actual trajectory of artificial intelligence development.

What's clear is that serious researchers taking fundamentally different approaches and backing up their beliefs with significant commitment creates the conditions for genuine progress. In a field where consensus sometimes masquerades as truth, Le Cun's willingness to challenge the conventional wisdom and bet on an alternative vision is not just intellectually honest—it's essential for ensuring that AI research doesn't get locked into local optima.

The question of what intelligence actually is, how it emerges, and what the most fruitful path to artificial general intelligence might be remains fundamentally unsettled. Le Cun's work, both in developing world models and in articulating the limitations of current approaches, represents one of the most serious and well-informed efforts to answer these questions. Whether his vision proves to be the correct direction or not, the rigor of his thinking and the courage of his convictions make his perspective essential to the ongoing conversation about AI's future.

FAQ

What exactly is a world model in AI?

A world model is an artificial intelligence system trained to understand and predict how the physical world behaves by learning from observations like video or sensor data, rather than from text. Instead of predicting the next word in a sentence (like language models do), a world model predicts how environments will change over time, develops causal understanding of physical systems, and can plan sequences of actions to achieve goals. The key advantage is that such systems learn through self-supervised learning—they don't require explicit labels, just need to observe patterns in how the world evolves.

How does V-JEPA technology work and what makes it different?

V-JEPA (Video Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture) works by converting video frames into compressed representations called embeddings, then training the system to predict future embeddings based on current ones and action information. The system learns by masking parts of videos and predicting the hidden portions, similar to masked language models but applied to spatiotemporal data. What makes it different from language models is that it learns physics and causality from visual observation rather than text patterns, theoretically giving it better understanding of how the real world actually works.

Why does Yann Le Cun believe large language models have fundamental limitations?

Le Cun argues that large language models are constrained by their training method—predicting the next text token based on previous tokens. While this creates systems good at language tasks, it doesn't develop genuine understanding of physics, causality, or how to apply knowledge to novel situations. Language models essentially perform sophisticated pattern matching rather than developing causal models, which Le Cun views as essential for true artificial general intelligence. He acknowledges LLMs are useful tools but contends they represent a dead end for achieving AGI.

What is Advanced Machine Intelligence (AMI) and how is it different from current AI approaches?

Advanced Machine Intelligence (AMI) is Le Cun's umbrella term for the next generation of AI systems built around world models and learning-based approaches rather than pure language scaling. AMI systems would combine world model understanding of physics with planning capabilities, persistent memory, reasoning about causality, and the ability to generalize to novel situations. The difference from current approaches is philosophical: rather than treating intelligence as pattern-matching (which LLMs do), AMI treats intelligence as emerging from interactive learning with the environment.

What was Le Cun's breakthrough contribution to artificial intelligence?

Le Cun is most famous for developing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in the 1980s, a breakthrough architecture specifically designed for visual data that dramatically reduced computational requirements compared to fully connected networks. This work was validated in 1998 when his CNN successfully read handwritten digits on checks in real-world deployment, proving neural networks could solve practical problems. He also made fundamental contributions to understanding deep learning, training techniques, and championed neural networks when the field was skeptical of the approach.

Why did Le Cun leave Meta after being chief AI scientist?

Le Cun departed Meta because his vision for AI's future—focused on world models and learning-based systems—diverged from Meta's current strategic emphasis on large language models. He wanted to pursue research without the operational constraints of a corporate structure. Rather than become CEO of his new venture, Le Cun chose to be executive chair, maintaining the freedom to pursue research vision while someone else handles management responsibilities, reflecting his insight that "I'm a scientist, a visionary... but I can't be a CEO."

How does embodied AI relate to world model development?

Embodied AI refers to systems that interact with the physical world through robotics, allowing them to act on their environment and observe consequences. World models can benefit enormously from embodied interaction because the system doesn't just observe—it experiments. A robot trying different actions and seeing results learns causality more directly than a system passively watching video. Many of Le Cun's world model concepts are intended to work with robotic systems that can physically test hypotheses about how the world works.

What makes learning the fundamental principle for intelligence according to Le Cun?

Le Cun's philosophy, rooted in developmental psychology and cognitive science, holds that intelligence emerges from the capacity to extract patterns and causal structure from experience, not from pre-programmed knowledge or pure language ability. Humans don't learn intelligence primarily through reading; we learn through embodied interaction with our environment from infancy. Applying this insight to AI means building systems whose fundamental mechanism is learning from experience—whether through observation, experimentation, or interaction—rather than static training on labeled datasets.

How will world models impact practical AI applications for developers?

For developers building applications today, world models represent a future capability that will eventually enable more general, transferable AI systems that can adapt to novel situations rather than relying on task-specific training. In the immediate term, products like Runable continue to offer practical AI automation for content generation and workflows using current language model capabilities, while researchers work on developing world models that might eventually replace or enhance these approaches with deeper physical reasoning and better generalization.

What is the relationship between neuroscience and Le Cun's AI architecture ideas?

Le Cun believes artificial intelligence should learn from neuroscience principles about how biological brains actually work. The brain uses massive amounts of unsupervised and self-supervised learning (learning structure without explicit labels), grounds learning in physical embodiment, updates continuously throughout life rather than training once and freezing, and uses local learning rules rather than centralized optimization. World models incorporate these neuroscience-inspired principles, attempting to create artificial systems that learn more like biological brains learn rather than through the scaled-up pattern matching of current language models.

Key Takeaways

- Intelligence emerges from learning, not from pre-programmed rules or pure text pattern-matching, according to Le Cun's foundational philosophy

- World models trained on video and sensor data offer an alternative to language models, potentially providing genuine understanding of physics and causality

- Large language models have fundamental limitations despite their impressive capabilities—they understand language patterns, not the world itself

- Le Cun's departure from Meta signals serious investment in world model research, not just academic theorizing, with Advanced Machine Intelligence Labs bringing this vision to practical implementation

- The AI research community is at a crossroads, with competing visions about whether language scaling or learning-based world models represent the true path to artificial general intelligence

- Physical embodiment and interaction with environments appears crucial for developing the kind of general intelligence that can transfer knowledge across domains

- This fundamental disagreement among field leaders will shape AI research priorities and investment allocation for years to come

- Multiple approaches coexist: from Le Cun's fundamental research on AGI to practical AI automation tools solving immediate business problems for developers and teams

- The next five years will provide empirical testing grounds for these competing hypotheses about AI's future trajectory

- Both research directions matter: long-term fundamental research on world models and immediate practical applications of current AI capabilities serve different but important purposes in advancing the field