Introduction: The Moment Africa Takes Control of Its Own Defense

Imagine waking up to news that your nation's critical infrastructure—power plants, oil pipelines, water systems, communication networks—is being monitored and protected by technology built thousands of miles away, controlled by foreign governments with their own geopolitical interests. That's been Africa's reality for decades. But something just shifted.

In early 2025, two Gen Z entrepreneurs did something that seemed impossible: they convinced some of the world's most sophisticated venture capital firms to back a fundamentally African solution to Africa's most pressing security challenge. Nathan Nwachuku, 22, and Maxwell Maduka, 24, launched Terra Industries out of Nigeria's capital, Abuja, with a mission that sounds simple but carries seismic implications for the entire continent. They're building Africa's first truly sovereign defense prime—a company that designs, manufactures, and operates the autonomous systems, surveillance infrastructure, and intelligence platforms that African nations have historically relied on Western powers, China, and Russia to provide.

The numbers tell the story. Terra just raised

But here's what makes this moment historically significant. Africa currently experiences more terror-related deaths than any other region globally. Boko Haram, Al-Shabaab, ISWAP, and countless militant groups exploit a fundamental vulnerability in continental infrastructure: the absence of real-time, sovereign intelligence and response capabilities. When African governments need to know what's happening at their oil fields, hydroelectric plants, or national borders, they often depend on intelligence from foreign governments—intelligence that may or may not align with African interests, arrives with significant delays, or comes with strings attached.

Terra is attacking this at the root. The company's founders recognized something that previous generations of African entrepreneurs missed or lacked the resources to pursue: the continent is experiencing rapid industrialization, attracting massive foreign investment, and building critical infrastructure at an unprecedented scale. But that infrastructure remains vulnerable to the very threats that have plagued Africa for two decades. The opportunity wasn't just to build a business—it was to fundamentally reshape power dynamics across an entire continent.

What started as a conversation between two engineers—one who spent years building educational technology, the other who previously founded a drone company at 19 and served as an engineer in the Nigerian Navy—has become something much larger. It's become a demonstration that Africa doesn't need to wait for external solutions. The continent has the talent, the capital, and now, the proof points.

This article explores how Terra Industries emerged, why the moment matters beyond venture capital metrics, what autonomous defense systems actually look like on the ground, and what this signals about Africa's future relationship with its own security and sovereignty.

TL; DR

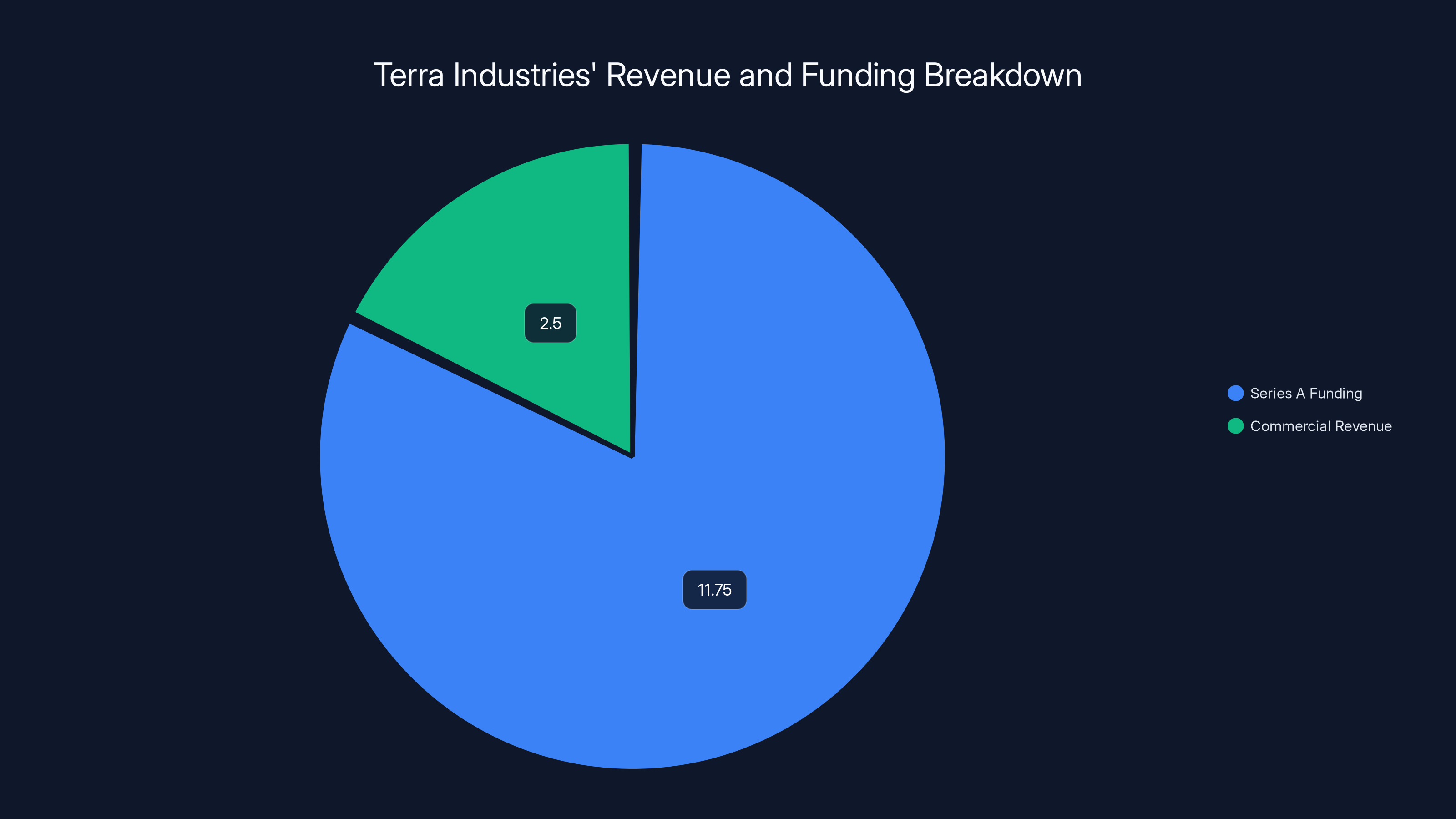

- Terra Industries closed $11.75M Series A funding led by 8VC to build Africa's first sovereign defense prime with autonomous systems and AI-powered intelligence platforms

- **Already generating 11 billion in critical infrastructure across multiple African nations

- 40% of engineering team comes from Nigerian military with advisors including Nigeria's Vice Air Marshal Ayo Jolasinmi, establishing deep institutional credibility

- Multi-domain approach covering air (long and short-range drones), ground (surveillance towers, ground drones), and maritime (offshore rig and pipeline protection) systems

- Sovereign intelligence model eliminates dependence on Western, Chinese, or Russian intelligence services, giving African governments real-time data and decision-making autonomy

- Bottom Line: Terra represents the beginning of Africa building its own defense infrastructure rather than remaining dependent on foreign powers

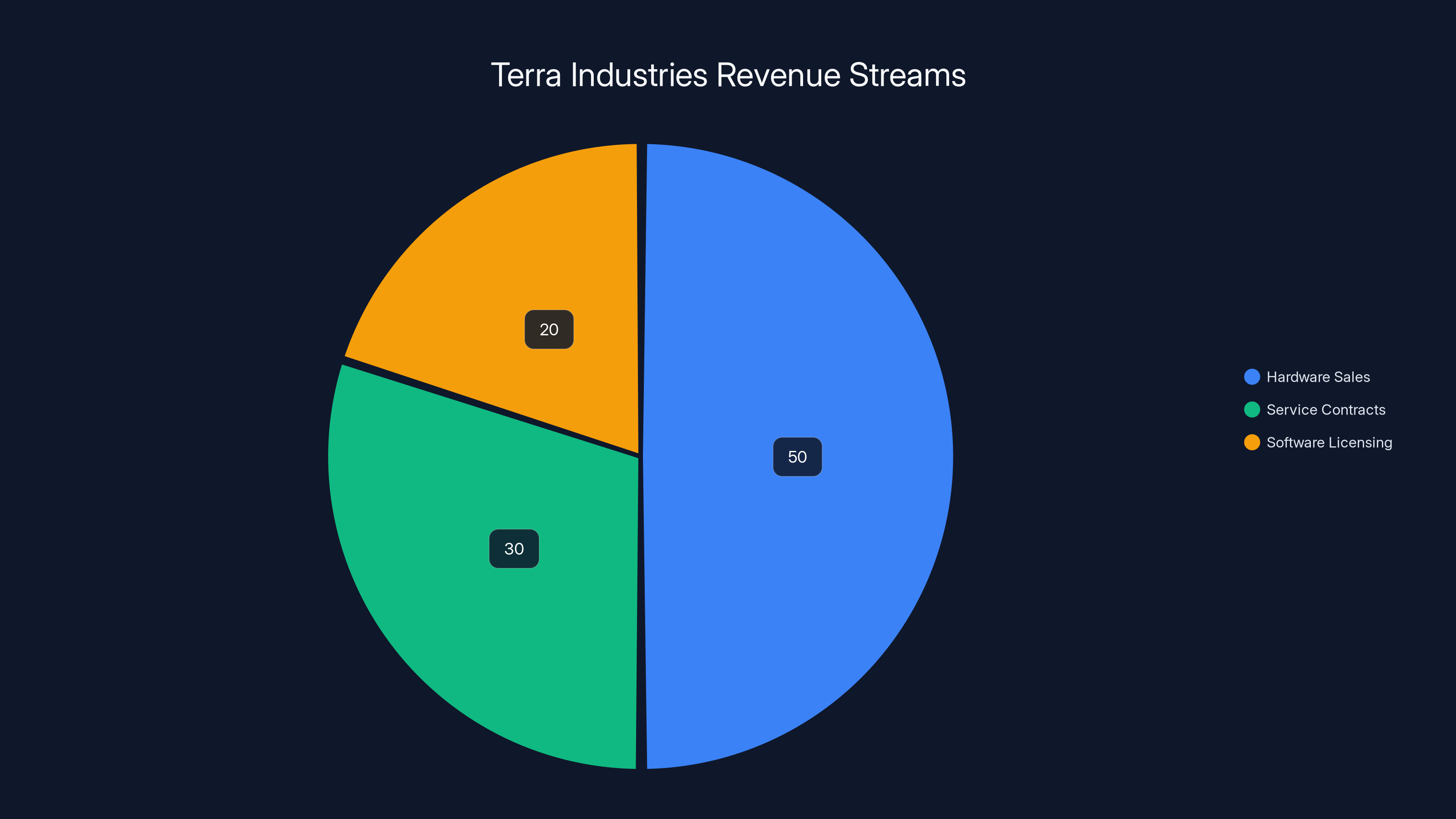

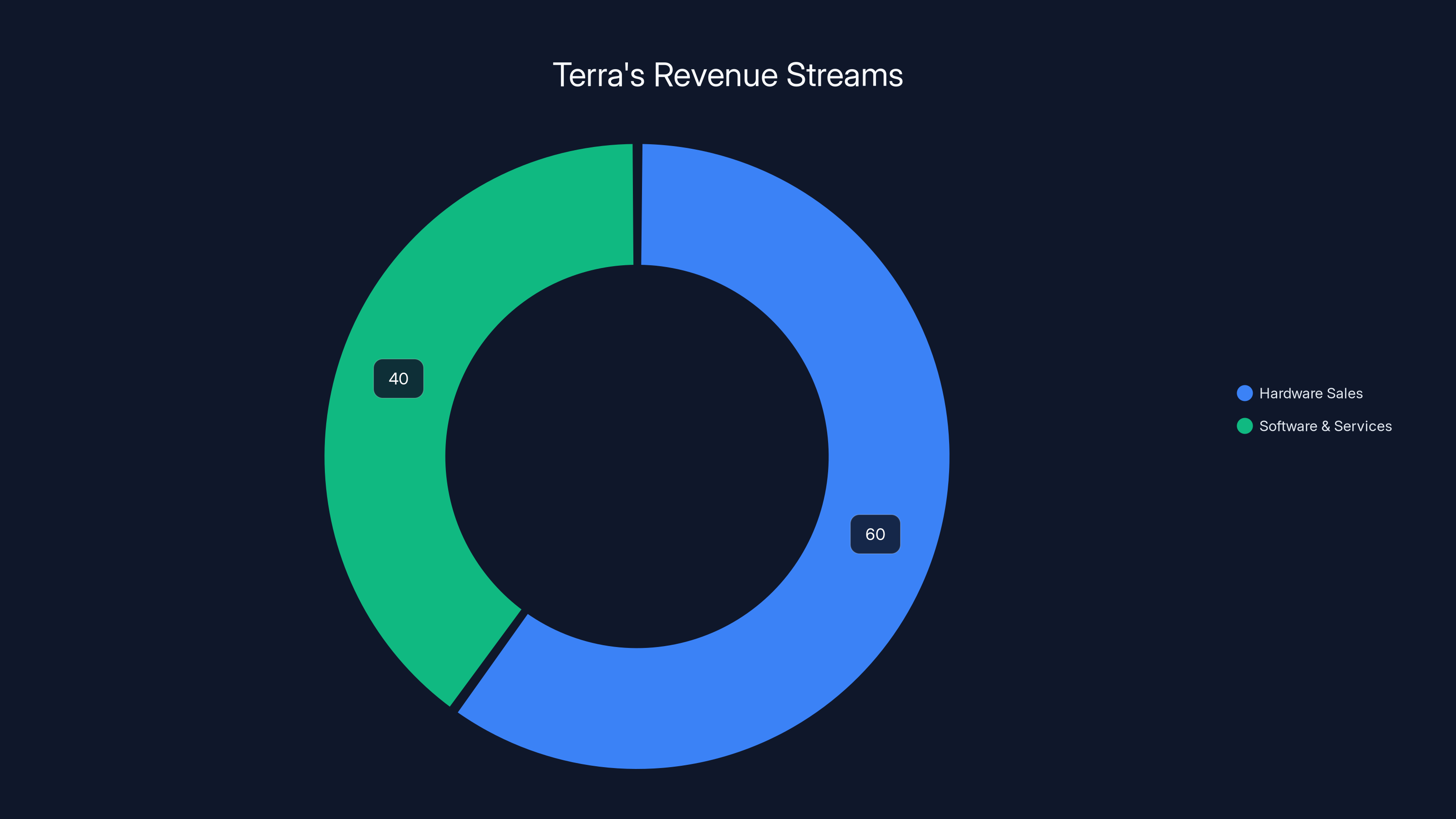

Estimated data shows that Terra Industries likely generates 50% of its revenue from hardware sales, 30% from service contracts, and 20% from software licensing.

The African Security Crisis That Nobody Talks About

When we discuss global terrorism, the conversation typically centers on the Middle East. We hear about conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Afghanistan. We see documentaries about extremist networks in those regions. But the uncomfortable statistical reality is that Africa experiences more terror-related deaths annually than the entire Middle East. In 2024 alone, terrorist attacks in Africa claimed tens of thousands of lives—more than any other continent, despite receiving a fraction of the international security investment.

This isn't random violence. It's highly organized, well-resourced, and increasingly sophisticated. Groups like Boko Haram have evolved from ragtag militias into structured military organizations with their own supply chains, training programs, and intelligence operations. Al-Shabaab controls territory across multiple African nations and coordinates operations with precision that would rival established military units. The Islamic State's African franchises operate across the Sahel with growing capability.

But here's the part that makes this an economic and development problem, not just a security problem. These groups don't just attack villages. They attack the infrastructure that powers economic growth. They target power plants, sabotage oil and gas pipelines, destroy water systems, and disable communication networks. A 2023 study found that terrorism-related infrastructure damage costs African economies over

When Shell loses control of a pipeline in Nigeria to militant groups, that's not just a corporate loss. That's lost tax revenue that could fund schools, hospitals, and roads. When a power plant gets sabotaged, it's entire regions plunging into darkness. When communication infrastructure gets destroyed, it creates humanitarian crises because nobody can coordinate emergency response.

The traditional response to this problem has been military intervention from foreign powers or reliance on foreign intelligence services. The United States maintains military bases across Africa. France operates security operations throughout the Sahel. China and Russia have quietly expanded their security presence across the continent. When an African government needs intelligence about a threat at a specific location, they often make calls to Washington, Paris, Beijing, or Moscow.

This creates a fundamental power asymmetry. Foreign intelligence services have their own priorities. They may prioritize information that serves their geopolitical interests over African interests. Intelligence sharing happens slowly, sometimes selectively. Response times stretch from minutes to days. African nations essentially outsource their ability to respond quickly to threats on their own territory.

Terra's founders understood this dynamic intimately. Nwachuku's epiphany came after spending years building educational technology in Nigeria. He watched the continent transform—new money flowing in, infrastructure projects expanding, young people creating startups and building companies. But underneath that promise, he saw a fundamental vulnerability that could derail everything. You can't build a knowledge economy if roads get blown up. You can't attract foreign investment if investors fear supply chain disruption. You can't create jobs if companies flee due to insecurity.

The insight was elegant: Africa doesn't need charity or military aid. It needs sovereignty over its own security apparatus. It needs to be able to know what's happening in its own backyard in real time, and respond with its own forces, based on decisions made by African leaders.

Terra's strategic growth from a

Who Are Nathan Nwachuku and Maxwell Maduka?

Most Silicon Valley origin stories involve founders who were coding since age seven, dropped out of elite universities, or had access to mentors from previous startup successes. Nwachuku and Maduka's path was different. Neither fits the typical venture capital founder archetype. Both are West African. Both represent something the technology industry desperately needs more of: perspectives built from deep understanding of actual problems in their own communities.

Nwachuku started his professional career building educational technology—the kind of work that's necessary but doesn't typically attract flashy venture capital. Education technology in Africa is important, but it doesn't make venture partners' hearts race. Yet it gave him something more valuable than a headline: it gave him credibility and access within African ecosystems. He understood regulatory environments. He understood how African organizations actually work. He understood the difference between what works in theory versus what works when implemented across Nigerian cities.

But more importantly, his work in edtech made him realize the constraint on everything. Terrorism and insecurity. Not lack of education—Africa has incredibly motivated students. Not lack of resources—Africa has capital and international support. The limiting factor was constant. Without solving security, nothing else mattered.

Maduka's background was more directly tied to the problem. At 19, he founded a drone company—a bold move in an environment where most people his age were choosing safe corporate jobs or trying to migrate to the United States. Drone technology, especially in African contexts, sits at the intersection of multiple regulatory, technical, and political challenges. You need to understand aviation regulations, coordinate with military and security agencies, solve complex engineering problems, and operate in regulatory environments that didn't yet have clear rules for commercial drones.

But Maduka's real credibility came from his military service. He worked as an engineer in the Nigerian Navy, which gave him something that venture capital firms value enormously: legitimate understanding of how defense systems actually operate, credibility with military institutions, and access to problems that most private sector technologists never encounter.

When these two connected, they recognized they were aligned on a problem nobody else was addressing. The conversation probably went something like this: "What if we built this ourselves? Not overseas, not through foreign partnerships, but here, in Africa, with African engineers, solving African problems."

It sounds obvious stated that way, but it was genuinely radical. Africa had never produced a "defense prime"—a company that designs, manufactures, and operates integrated defense systems at the continental level. That's a category that exists in the United States (Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics), Europe (Airbus Defense, Thales, Leonardo), and increasingly in Asia and the Middle East. But not Africa.

The founding team they assembled was deliberately built to address this gap. They recruited heavily from the Nigerian military—not as consultants, but as full-time engineers. Forty percent of their engineering team held equivalent roles in the Nigerian military. This isn't just good hiring; it's a message. We're serious about understanding what the military actually needs. We have credibility with the institutions we're serving.

They brought Alex Moore, 8VC's defense investing specialist, onto the board. Moore has backed some of the most innovative defense startups globally. His presence signals that this isn't an Africa-focused charity project; it's a technically sophisticated defense company that happens to be African.

They recruited Nigeria's Vice Air Marshal Ayo Jolasinmi as an advisor—one of the most senior military figures in West Africa. His involvement carries weight that no venture capitalist could provide.

What emerged was a founding team with the rare combination of tech startup experience, military credibility, and deep African context. That combination became Terra Industries' actual competitive advantage.

Understanding Terra's Technical Architecture: More Than Drones

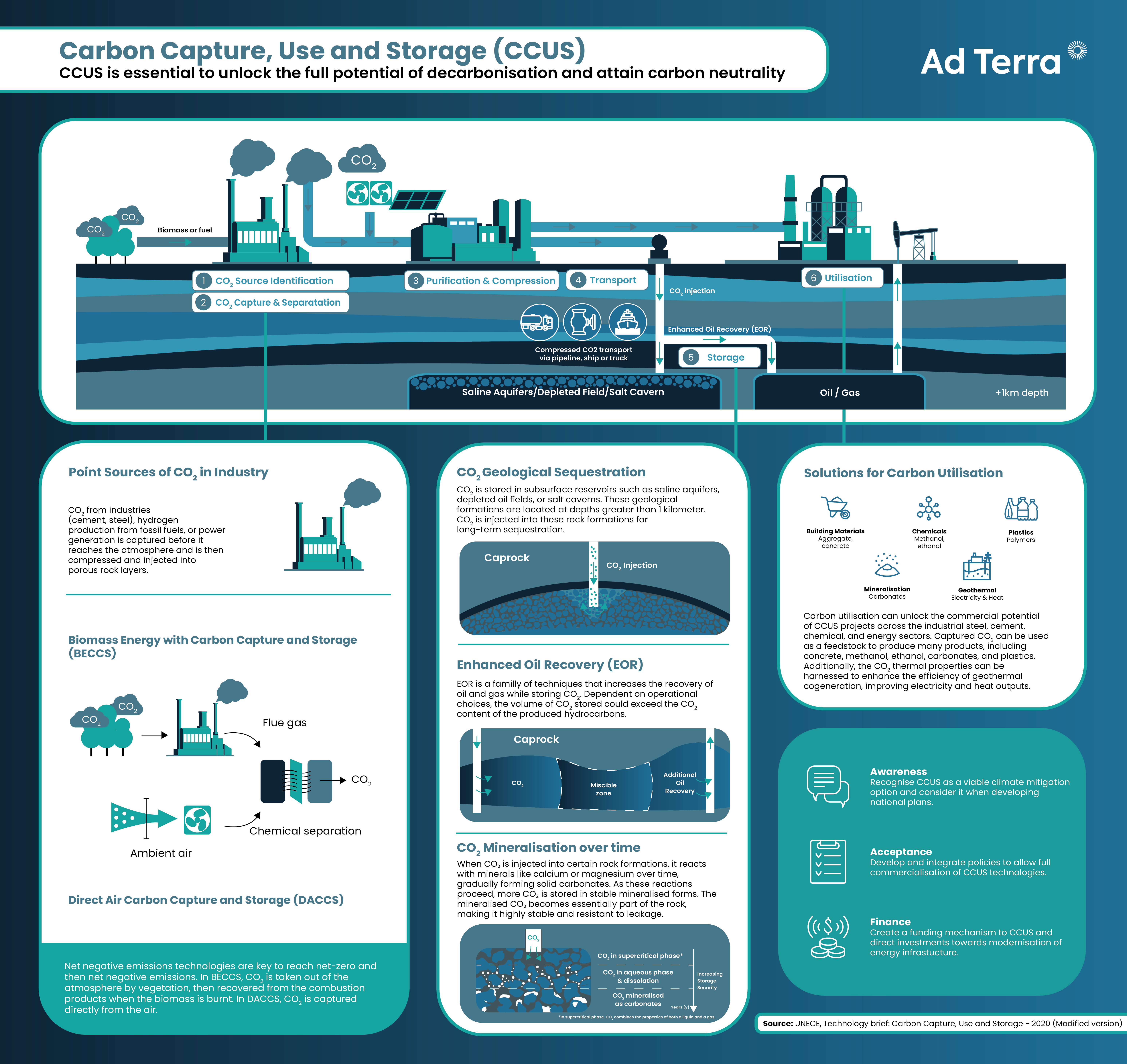

When people hear "defense startup," they often picture military drones dropping payloads or fighter jets. Terra's actual approach is more sophisticated and, frankly, more important. The company is building what amounts to a continental nervous system for African critical infrastructure.

The system works in three layers: detection, analysis, and response.

The Detection Layer: This is where Terra's multi-domain approach becomes critical. The company operates across air, ground, and maritime domains because threats come from all directions.

In the air, Terra manufactures both long-range and short-range drones. Long-range drones can monitor vast territories—imagine surveilling a 500-square-kilometer oil production area continuously. They stay aloft for hours, collecting data across multiple sensor types. Short-range drones provide tactical capability, allowing rapid response when a potential threat is detected in a specific location.

On the ground, the company operates surveillance towers equipped with sensor systems that watch approaches to critical infrastructure. These aren't simple cameras. They're integrated systems that combine multiple sensor types—radar, thermal imaging, acoustic sensors—to identify threats even in darkness or poor visibility. The company also produces ground drones that can move to investigate specific alerts or provide persistent surveillance in areas where stationary towers aren't effective.

The maritime layer is still in development, but it's crucial. Africa's critical infrastructure extends offshore. Nigeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, and other nations rely on offshore oil and gas platforms. Those platforms generate hundreds of billions in annual revenue. They're also vulnerable. An attack on a single platform can kill hundreds of people and disrupt global energy markets.

Terra is developing maritime surveillance systems to monitor approaches to offshore infrastructure, detect suspicious vessel activity, and provide real-time alerting when threats emerge.

The Analysis Layer: This is where Artemis OS, Terra's proprietary software platform, becomes the real innovation. The detection layer collects massive amounts of raw data. Thousands of hours of drone video. Radar returns from surveillance towers. Acoustic signatures from ground sensors. Maritime vessel tracking data. Without intelligent analysis, this is just noise.

Artemis OS aggregates all this data and applies machine learning models trained on years of actual threat patterns. The system identifies what's normal and what's anomalous. When a vehicle approaches an oil pipeline at night when nobody should be there, the system detects the anomaly. When a vessel's behavior doesn't match its declared purpose, the system flags it. When communication patterns suggest coordinated activity, the system connects the dots.

This is the intelligence layer that African governments have historically needed to import from foreign intelligence services. Terra is building it domestically.

The Response Layer: Detection and analysis are only useful if they enable faster response. Artemis OS doesn't just alert security agencies after the fact. It provides real-time geolocation, threat assessment, and routing information to response forces. A security team gets an alert that tells them not just that something's wrong, but exactly where it is, what kind of threat it appears to be, and the fastest route to intercept.

This compression of decision-making time from hours to minutes is where the system becomes genuinely transformative. Traditional security models work like this: something happens, intelligence trickles in slowly, decisions get made, response forces deploy hours later. By then, attackers have had plenty of time to complete their objectives.

Terra's model compresses this dramatically. Real-time detection, instantaneous analysis, immediate response.

The technical architecture matters because it demonstrates that Terra isn't just strapping cameras to drones. They're building an integrated system that requires deep understanding of military operations, sensor technology, data processing, machine learning, and human decision-making.

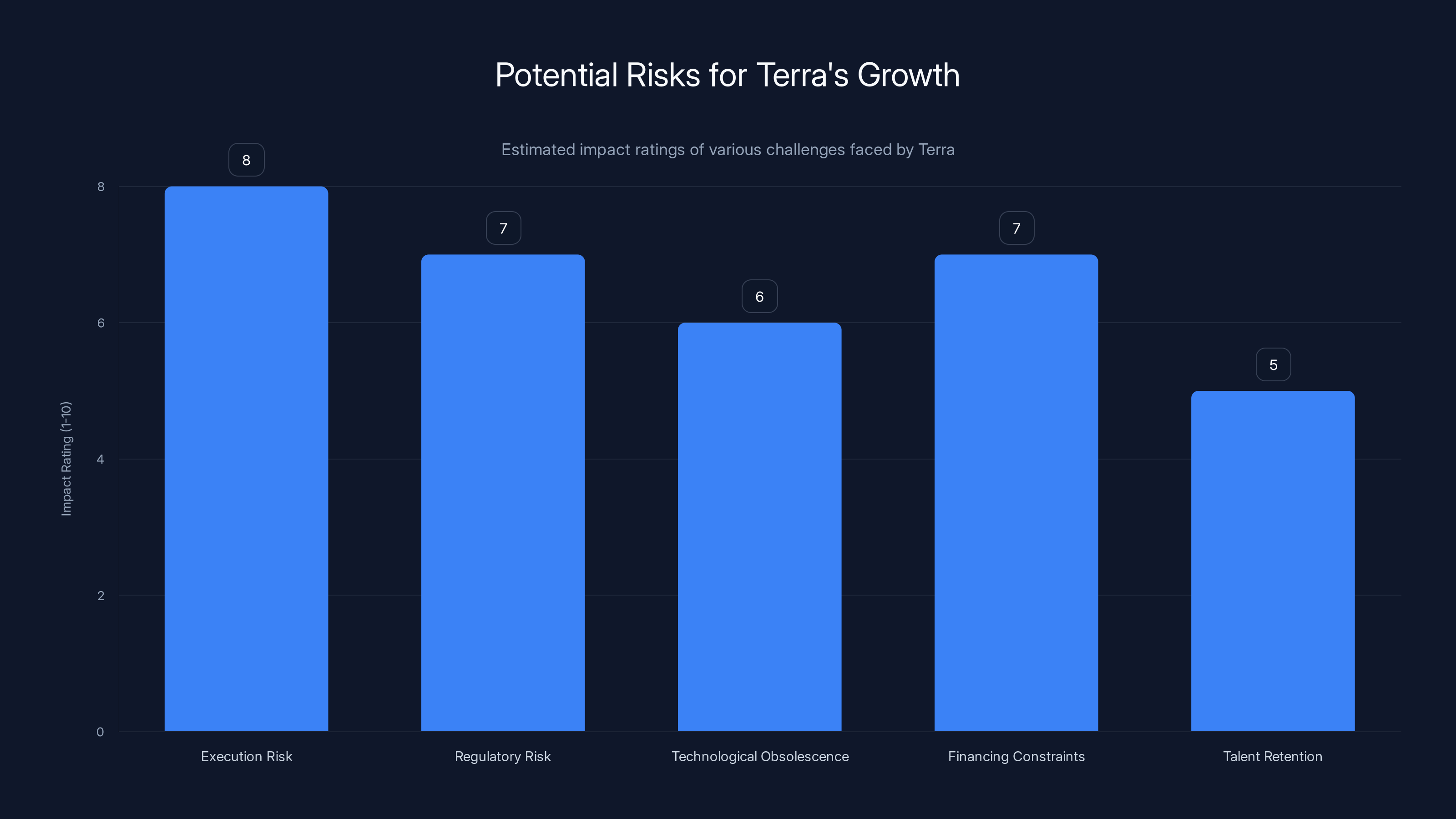

Execution risk is rated the highest due to the complexity of scaling operations across multiple nations, followed by regulatory and financing challenges. Estimated data.

The Sovereign Intelligence Problem That Shaped Terra's Mission

There's a dimension to Terra's value proposition that goes beyond the obvious security benefits. It's about something more fundamental: sovereignty. Specifically, informational sovereignty.

When an African nation's intelligence about its own territory comes from foreign intelligence services, that nation isn't actually in control of its own security decision-making. It's making decisions based on information filtered through another nation's priorities and political interests.

Consider a realistic scenario: Nigeria detects suspicious activity near an oil platform. The government asks the United States for intelligence because the U. S. maintains sophisticated surveillance capabilities in the region. The U. S. collects the data, analyzes it, and decides whether to share it, when to share it, and in what level of detail. If the activity might involve actors that the U. S. prefers not to antagonize, or if providing intelligence might complicate U. S. diplomatic efforts, the sharing might be delayed or incomplete.

This isn't theoretical. African governments have documented cases where timely intelligence was withheld or delayed due to foreign policy considerations that had nothing to do with African security interests.

With Terra, African governments can know what's happening on their own territory, make their own decisions, and execute their own response without waiting for external intelligence services to process and authorize information sharing.

Nwachuku articulated this clearly: the problem isn't lack of firepower. Most African armies have significant military capacity. The problem is lack of sovereign intelligence. Terra is specifically designed to shift that dynamic.

This has broader implications beyond the security domain. Once a nation has real-time intelligence about its critical infrastructure, it has something much more valuable: the ability to understand its own resource base and make economically rational decisions about it. It has the capacity to detect theft. It has the ability to prevent sabotage. It has the foundation for genuine economic planning and growth.

From a venture capital perspective, this is why 8VC invested. Defense investing in the U. S. and Europe is typically about incremental improvements to existing systems. Africa represents an opportunity to build integrated systems from scratch in markets that currently have almost zero indigenous defense technology capability.

But from an African perspective, it's about something deeper: reclaiming control over the most fundamental aspect of national sovereignty—the ability to protect your own territory and make your own security decisions.

How Terra Went From Stealth to $11.75M in Funding

Terra spent approximately five years in stealth mode before announcing publicly in early 2025. This timeframe matters because it reflects careful, deliberate execution rather than the move-fast-break-things mentality of typical venture-backed startups.

The company raised an initial $800,000 pre-seed round before stepping into the spotlight. In venture capital terms, that's modest—barely enough to hire a team and build initial prototypes. Yet the pre-seed round generated sufficient traction that when the company appeared on CNN, it caught the attention of sophisticated investors.

The CNN appearance is instructive. Terra didn't go on CNN to raise money. The company went public because it had achieved something concrete: it had built systems, deployed them, and was protecting actual African critical infrastructure. The press coverage was a byproduct of that operational reality, not the driver of fundraising.

By the time Terra announced its Series A round in early 2025, the company had already achieved remarkable metrics:

- $2.5 million in commercial revenue generated from customers paying for Terra's systems and ongoing data services

- $11 billion in protected assets across multiple African nations and diverse infrastructure types

- 40% of engineering team from military backgrounds, providing credibility and understanding of actual customer needs

- Federal contracts secured with African governments, validating the business model at scale

These aren't vanity metrics. Commercial revenue demonstrates that customers actually value the product enough to pay for it. Protected asset value shows scale. Military team composition shows credibility with the most demanding customers.

The Series A round itself tells a story about how investor appetite for African tech has evolved. 8VC leading the round is significant. 8VC is Joe Lonsdale's defense-focused fund, and Lonsdale is deeply embedded in U. S. defense and security ecosystems. For Lonsdale to lead a defense technology round in Nigeria signals that American defense investors see African security technology as strategically important.

The co-investors amplify this message. Valor Equity Partners focuses on defense and aerospace. Lux Capital invests in deep technology and physics-based companies. SV Angel is one of the most active early-stage funds globally. Nova Global focuses on emerging markets. Even among the co-investors, you see a pattern: sophisticated investors who understand defense, deep technology, and emerging markets all betting on Terra.

African investors also participated: Tofino Capital, Kaleo Ventures, and DFS Lab. This domestic capital backing signals that African investors see Terra as part of a broader opportunity in building African technology infrastructure that was previously impossible.

What makes the funding round particularly interesting is the speed with which it apparently came together. Terra had product-market fit before raising. The company was already generating revenue. The company had already deployed systems at scale. When you're in that position, raising capital becomes much easier because you're not asking investors to believe in your vision—you're asking them to participate in scaling something that's already working.

Terra's revenue is estimated to be split between hardware sales (60%) and recurring software and service fees (40%). This highlights the importance of their sustainable, recurring revenue model. Estimated data.

The Manufacturing Strategy: Why Keeping Production in Africa Matters

One decision Terra made explicitly in the fundraising announcement carries enormous symbolic and practical significance: manufacturing will remain in Africa, with plans to open more factories across the continent.

This is unusual for a defense technology company. Most defense primes manufacture in their home countries or in allied nations. There are good reasons for this: supply chain security, quality control, intellectual property protection. But Terra made a deliberate choice to build the manufacturing footprint in Africa itself.

From a business perspective, this makes sense. African labor costs are significantly lower than North American or European equivalents. African supply chains for certain components are already developed. And frankly, if you're positioning yourself as Africa's defense prime, it helps if you're actually manufacturing in Africa.

But there's a deeper rationale. Manufacturing creates jobs. Lots of them. When you open a factory that produces drone components, surveillance systems, and ground-based sensors, you're creating skilled manufacturing jobs in countries where unemployment, especially among young people, remains stubbornly high. An engineer in Nigeria earning $30,000 per year is a well-paid professional. That engineer's spending power then stimulates local economies, creates demand for housing and services, and builds the economic foundation for sustainable growth.

Terra announced plans to open software engineering offices in San Francisco and London, but kept manufacturing in Africa. This is actually a sophisticated geographic strategy. San Francisco and London are where you attract world-class machine learning engineers and build partnerships with the global technology ecosystem. But manufacturing stays where it serves the company's continental mission.

This also sends a message to other African founders and investors: you don't need to export your manufacturing to scale globally. You can build complex, sophisticated systems in Africa and compete on the world stage. That message cascades through ecosystems. If Terra can do it in defense hardware, why can't other companies do it in autonomous vehicles, industrial robotics, or advanced manufacturing?

From an African economic development perspective, this is almost as important as the defense capability itself. It signals that Africa isn't just a consumer market for technology. Africa is a producer. It's a place where sophisticated hardware gets designed, manufactured, and deployed.

Competitive Landscape: Why No One Has Done This Before

The obvious question emerges: if this opportunity was so clear, why didn't someone do it before? The answer reveals a lot about how global technology and defense markets actually work.

First, there's the capital and expertise barrier. Building defense systems requires deep technical knowledge, regulatory understanding, and operational credibility. That combination is rare globally, almost nonexistent in Africa. It requires people who understand both how to build software and how militaries actually operate. Most engineers who have military experience want to work for established defense contractors. Most software engineers haven't spent enough time around military operations to understand what they really need.

Nwachuku and Maduka's backgrounds solved this. Maduka had military experience but young enough to embrace startup methodology. Nwachuku had startup experience but deep enough African context to understand regulatory and operational realities. That combination rarely exists.

Second, there's the investor capital problem. Raising money for a defense company anywhere is difficult. Investors worry about regulatory risk, geopolitical complications, and export controls. In Africa, those concerns multiply. Previous investors would have assumed it was impossible to get export licenses, build sophisticated manufacturing, and compete against established defense primes. Maybe those assumptions were wrong, but they were real constraints on earlier attempts.

Third, there's the market development problem. A few years ago, African governments might not have been ready to buy from a private sector defense technology company. They might have preferred foreign partners. They might have lacked the capital to invest in new systems. But African economies have grown significantly. Oil and gas revenues have improved. Governments now have resources for capital investment in critical infrastructure. And the security threat environment has deteriorated enough that the status quo became clearly inadequate.

The timing was right. The team was right. The capital was available. And Terra capitalized on it.

There's also a competitive point worth noting: established defense primes probably couldn't do what Terra is doing. Lockheed Martin or Northrop Grumman entering the African defense market would involve completely different organizational dynamics. They'd need to navigate African political sensitivities around foreign military equipment. They'd face pricing expectations that wouldn't make sense for their cost structures. They'd struggle to integrate with African militaries in the way a homegrown company can.

Terra doesn't have these constraints. Being African is actually its competitive advantage, not a handicap.

Terra Industries secured

The Revenue Model: How Terra Makes Money

Understanding Terra's revenue model provides insight into the sustainability and scalability of the business. The company generates revenue through two mechanisms: hardware sales and software services.

Hardware Revenue: African governments and commercial customers order Terra systems. These might be drone platforms, surveillance towers, ground-based sensors, or integrated monitoring systems. When a government contracts with Terra to protect its critical infrastructure, that contract includes hardware procurement.

Software and Service Revenue: Once the hardware is deployed, customers pay annual fees for data processing, storage, and intelligence services provided through Artemis OS. This is the recurring revenue component that makes the business model attractive to investors and sustainable over time.

The recurring revenue model is particularly important. One-time hardware sales can be lumpy and unpredictable. But if a customer is paying annual fees for intelligence services, that creates predictable, recurring revenue that compounds over time. A customer acquiring cost is earned back through multiple years of service fees.

The company has achieved remarkable commercialization velocity:

The federal contracts Terra recently won but couldn't discuss publicly probably exceed the commercial revenue. African governments can typically afford to pay for systems with significant national importance, especially when the infrastructure being protected generates revenue itself (like oil platforms or hydroelectric facilities).

Looking forward, the revenue model should scale well. As more governments standardize on Terra's systems, the company can increase prices and expand service offerings. Artemis OS can be licensed to other parties. Training and professional services around system deployment create additional revenue streams.

The gross margins on software and services should eventually exceed 70%, which is typical for successful defense contractors. The hardware margins will be lower but still healthy once manufacturing reaches appropriate scale. The blended model creates a durable business with strong unit economics.

Regulatory and Export Control Challenges: The Elephant in the Room

There's an element of Terra's business that the company itself will navigate carefully: export controls and defense-related regulations.

When a company manufactures defense systems and wants to export them internationally, it typically needs export licenses. In the United States, these are controlled by the State Department and Commerce Department. Other countries have similar controls. The question becomes: what systems does Terra want to export, to whom, and how?

Terra's explicit focus on serving African nations is strategically smart partly because it sidesteps the most complex export control issues. If Terra sells exclusively within Africa to African governments, the export control challenges become much simpler. African Union members can trade with each other without the complex multilateral export control regime that would apply if Terra tried to export to Asia or the Middle East.

However, as Terra matures, the company may want to export systems internationally. A Middle Eastern customer might be interested in Terra's maritime surveillance systems. An Asian government might want ground-based sensors. At that point, the company will need to navigate export controls more carefully.

There's also a geopolitical dimension. Building sophisticated defense systems in Africa attracts attention from Western governments that have strategic interests in the region. American government agencies might have concerns about what technology Terra develops, how it's protected, and whether it might eventually reach adversaries. These aren't necessarily restrictions, but they're realities that Terra's leadership will need to navigate.

The company's decision to open software offices in San Francisco and London might partly address this. Having operations in the U. S. and U. K. provides those governments with some visibility into the company's operations and may ease export control processes. It also signals alignment with Western security interests, even as Terra maintains its African independence.

These regulatory considerations don't undermine Terra's value proposition. They're just part of operating in defense technology globally. But they're worth understanding as potential constraints on growth or expansion opportunities.

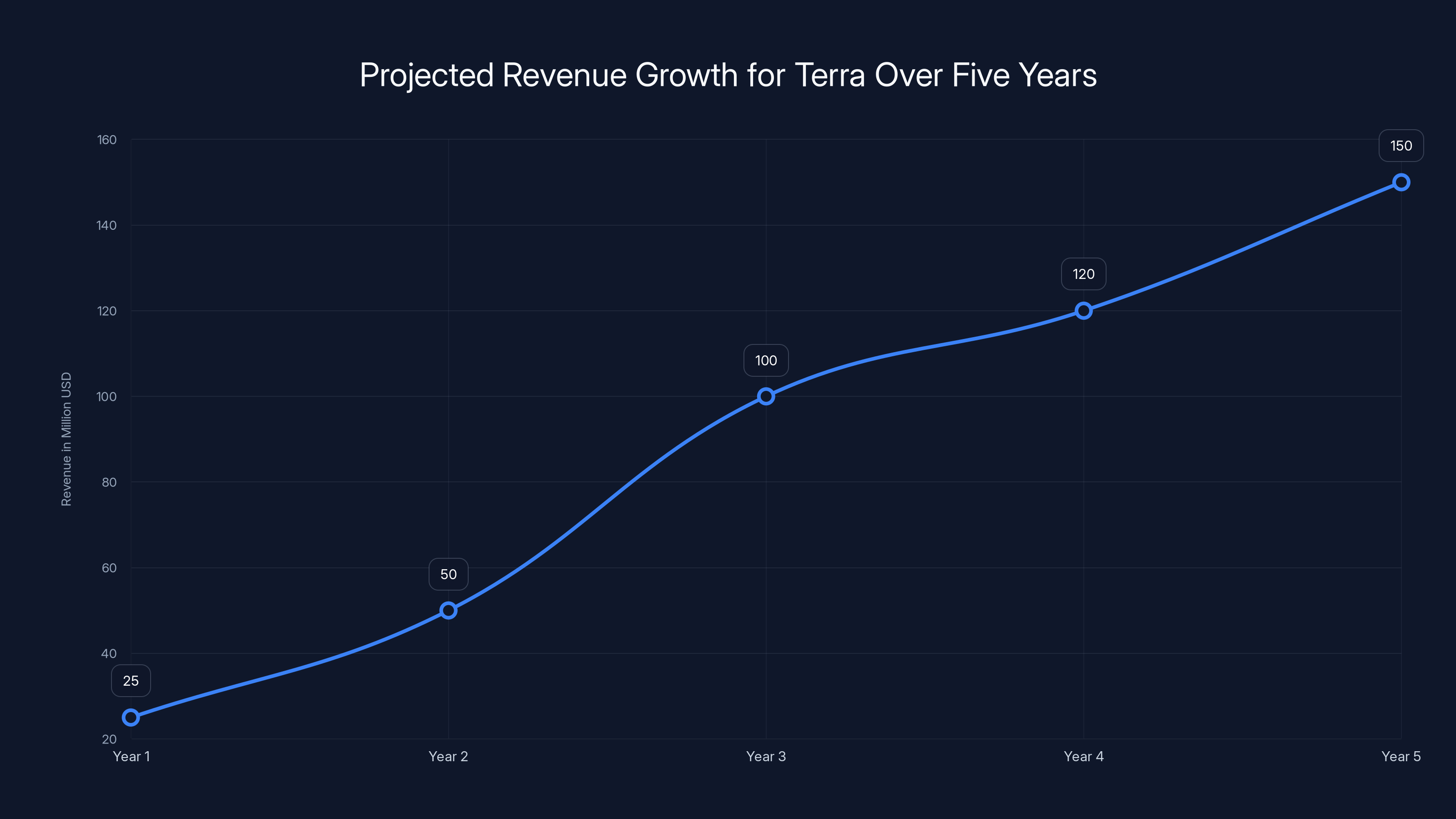

Terra aims to grow from

Why This Matters Beyond Terra: The Broader Significance

Terra's success becomes historically significant if we understand what it signals about Africa's future relationship with technology and sovereignty.

For decades, Africa's relationship with technology has been fundamentally asymmetric. Western companies sold technology to Africa. African companies mostly focused on small-scale services or niche applications. Critical infrastructure—telecommunications, energy, defense—relied on foreign technology and foreign expertise.

Terra represents a break from that pattern. It's not a startup that uses foreign technology to serve African customers more efficiently. It's a company building sophisticated technology that competes globally, serving African customers first, with African engineering talent and African manufacturing.

If Terra succeeds and scales, it becomes a template. Other African founders will see that you can build complex hardware technology in Africa. Other investors will see that African defense and infrastructure technology is investable. African governments will see that they don't need to rely on foreign powers for critical technological capability.

The ripples extend far beyond defense. If drone technology, manufacturing, and AI-powered analysis can be built in Nigeria, why not autonomous vehicles in South Africa? Why not advanced manufacturing in Ghana? Why not telecommunications infrastructure designed specifically for African conditions instead of generic global solutions?

This is fundamentally about African technological sovereignty. For centuries, Africa has been at the mercy of external technology and external actors. Terra is demonstrating that Africa can build its own sophisticated systems and compete globally while doing it.

The second significance is geopolitical. As Terra scales and African governments increasingly rely on Terra's systems instead of foreign intelligence services, the balance of power subtly shifts. African nations gain more autonomy in security decision-making. They become less dependent on any single external power. That doesn't mean they become adversarial to Western powers, but it means they have more leverage and more independence.

From an American strategic perspective, this is actually positive. An Africa with indigenous defense capabilities is more stable, more developed, and a better partner than an Africa dependent on external security guarantees. From an African perspective, it's obviously positive. From a global perspective, a more technologically autonomous Africa is a more economically dynamic Africa, which benefits global trade and stability.

The Challenges Ahead: What Could Go Wrong

Terra's trajectory so far has been impressive, but significant challenges remain.

Execution Risk: The company needs to scale manufacturing, expand software capabilities, and serve customers across multiple African nations simultaneously. That's complex. Manufacturing plants can have quality control issues. Software development can hit unexpected technical barriers. Customer integration can be messier than anticipated. Startups fail at execution all the time, and the fact that Terra has succeeded so far doesn't guarantee it will continue to.

Regulatory and Political Risk: Terra operates across multiple African nations with different regulatory frameworks, political systems, and military structures. A political coup in one country could disrupt operations. Regulatory changes could create barriers to expansion. International pressure could limit growth. These are real risks that established defense contractors manage carefully, but they're harder for a startup to navigate.

Technological Obsolescence: Defense technology moves quickly. AI capabilities are advancing rapidly. Drone technology evolves constantly. Sensor technology improves every year. Terra needs to continuously innovate to stay ahead of potential competitors or open-source alternatives. This requires sustained investment in R&D.

Financing Constraints: The $11.75 million raised is substantial, but scaling manufacturing and operations across Africa will likely require more capital. Future funding rounds might be harder if defense investors worry about political risk or if Terra's growth doesn't match projections.

Talent Retention: Terra is paying San Francisco software salaries in software offices in San Francisco and London. In Nigeria, the company is likely paying much less. The company needs to attract and retain world-class engineers in both locations. Brain drain has historically been a challenge for African tech companies. Terra's founders understand this, but it remains a risk.

Competitive Response: If Terra succeeds, competitors will emerge. Established defense contractors might build African operations. Other African startups might pursue similar approaches. Global drone and sensor manufacturers might position products specifically for African markets. Competition will intensify.

None of these challenges are disqualifying. Established defense contractors face similar risks. But they're real, and Terra's success isn't guaranteed. The company needs to execute well, navigate political realities carefully, and continuously innovate.

Investor Thesis: Why 8VC and Others Backed Terra

Understanding why sophisticated investors backed Terra provides insight into global venture capital thinking about emerging markets and defense technology.

For 8VC, Terra represents an attractive opportunity across multiple dimensions. First, there's the obvious market opportunity. African nations need defense systems. They have capital to spend. The market is currently served entirely by foreign suppliers. A company that can serve this market with better economics and better adaptation to African conditions has significant upside.

Second, there's the technological innovation angle. Artemis OS represents a genuine software innovation. The multi-domain approach to defense is thoughtful. The company isn't just strapping existing technology together. It's building integrated systems from scratch. That appeals to investors who back deep technology.

Third, there's the team signal. A 22-year-old and 24-year-old starting a defense company sounds risky. But when those founders have built previous companies, have military credibility, and understand African markets, the risk profile changes. Sophisticated investors know that startup success correlates with founder market knowledge and previous execution. Terra's founders have both.

Fourth, there's the defensibility angle. Once a government standardizes on Terra's systems, switching costs become high. A customer can't easily move from Terra's drones and intelligence software to a competitor's systems. That creates sticky revenue and barriers to competition.

Fifth, there's the geopolitical hedge. American investors backing African technology development is increasingly seen as strategically important. Africa is becoming more important geopolitically. Having American capital and expertise involved in African defense technology development ensures some level of Western influence and partnership, even as African nations build indigenous capabilities.

For Valor Equity Partners and other defense investors, the thesis is similar but perhaps slightly different. They're looking for the next Palantir or Anduril—companies that fundamentally reshape how nations think about defense and security. Terra could be that for Africa.

For Lux Capital and SV Angel, it's partly about being early in a category-defining company. If Terra becomes Africa's leading defense prime, early investors in the Series A round participate in significant returns.

The collective investor thesis is: Africa is developing rapidly, Africa's security challenges are genuine and growing, Africa's capital availability is increasing, and Africa has talented founders. A company serving Africa's security needs with African talent and manufacturing is exactly the kind of opportunity that comes around once a decade.

Lessons for Other African Founders and the Startup Ecosystem

Terra's success provides a template for other African entrepreneurs pursuing ambitious goals.

First Lesson: Identify problems where Africa has structural advantages over other regions. Terra's founders identified something that Western defense contractors struggle with: understanding African security contexts intimately and building systems optimized for African conditions. That local advantage became a competitive edge.

Second Lesson: Build credibility with your end customers before raising massive capital. Terra spent years building relationships with African militaries, securing contracts, and proving the concept. That credibility made raising $11.75 million much easier than it would have been if the company had approached investors with just an idea.

Third Lesson: Combine technical expertise with sector expertise. Maduka's military background and Nwachuku's understanding of African institutions meant they understood the problem deeply. They weren't learning about defense and Africa while building the company—they were applying deep knowledge they already possessed.

Fourth Lesson: Don't be constrained by geographic origin. Terra opened offices in San Francisco and London because that's where certain talent exists. Ambitious African founders should feel comfortable building globally while maintaining African operations and focus.

Fifth Lesson: Manufacturing and physical products aren't dead for African entrepreneurs. The assumption that Africa should focus only on software and services is false. Terra is proving that you can build sophisticated hardware in Africa and compete globally.

Sixth Lesson: Security and defense aren't forbidden topics for African founders. Previous African entrepreneurs might have assumed that defense technology was exclusively the domain of established Western corporations. Terra proved that African founders can build credible defense capabilities if they have the technical expertise and institutional connections.

For the broader African startup ecosystem, Terra's success also signals something important: there's capital available for ambitious African founders tackling big problems. The days of African startups being limited to copycat models or marginal innovations are ending. If you can identify real problems and build sophisticated solutions, capital will follow.

The Broader Context: Africa's Technology Trajectory

Terra's emergence must be understood in the context of broader African technology development. Over the past decade, Africa's technology sector has evolved dramatically.

A decade ago, African tech meant payment processing, e-commerce platforms, and financial inclusion services. All valuable, all important. But fundamentally serving consumers and small businesses. Companies like M-Pesa transformed financial services. Jumia built e-commerce. These successes were crucial for economic development.

But they didn't create the foundational infrastructure that more advanced economies rely on. They were solutions layered on top of existing (often inadequate) infrastructure rather than replacements for that infrastructure.

Terra represents a different category. It's building foundational infrastructure—critical technology that governments and major enterprises rely on to function. That's a step up in sophistication and importance.

Other examples of this evolution include companies building cloud infrastructure for African markets, companies developing advanced manufacturing technology, and companies addressing energy infrastructure challenges. These aren't consumer-facing services. These are foundational technology that enables everything else.

This evolution matters because foundational infrastructure generates more economic value, creates more jobs, and has multiplier effects throughout economies. When you build payment processing, you create value for merchants and consumers. When you build defense infrastructure, you enable governments to protect all economic activity occurring within their borders.

Terra is part of a wave of African founders who understand that Africa's development requires building foundational layers, not just optimizing existing systems.

The Role of Geopolitical Shifts in Creating Opportunity

Terra's founding and success reflect broader geopolitical shifts that have created space for African technological sovereignty.

For decades, any African country considering sophisticated defense systems would naturally turn to the United States, France, or another Western ally. The assumption was that these countries had the best systems, the most experience, and would provide preferential terms to allied nations.

But that equation is shifting. American defense companies are increasingly focused on large-scale conventional conflicts with other major powers, not on counterterrorism and internal security in developing nations. European defense companies face similar strategic shifts. Meanwhile, China has become increasingly active in African defense markets, offering equipment and training but often at terms that create long-term dependency.

African nations increasingly realize they need options. They don't want to be dependent on a single foreign power for critical technology. But they also can't easily develop indigenous capabilities alone.

Terra emerges in this gap. It offers African nations a third option: technology built specifically for African needs, by African founders, manufactured in Africa, but with partnership from global investors and expertise. It's independence without isolation.

That geopolitical evolution probably matters more to long-term opportunities than the specific technology Terra is building. As African nations increasingly assert technological sovereignty, the opportunities for local companies expand dramatically.

What Success Looks Like: Five-Year Projections

If Terra executes successfully over the next five years, what might success look like?

Year 1-2: Scale manufacturing operations. Open factories in 2-3 additional African countries. Expand customer base from primarily Nigeria to include at least 5 African nations. Reach $25-50 million in annual revenue (combining hardware and software). Secure additional federal contracts with African governments. Expand Artemis OS capability with additional AI features and sensor integrations.

Year 3-4: Become the leading defense technology provider across sub-Saharan Africa. Establish partnerships with international defense contractors for select capabilities. Begin exploring export opportunities to Asian or Middle Eastern markets. Reach $100+ million in annual revenue. Build software operations in multiple global cities beyond San Francisco and London. Achieve profitability or near-profitability.

Year 5+: Emerge as a globally competitive defense prime that happens to be African. Potentially go public or be acquired by a larger defense contractor at substantial valuation. Create thousands of direct manufacturing and engineering jobs across Africa. Establish Africa as a credible source of defense technology innovation on the global stage.

These projections aren't guaranteed. But they're plausible given Terra's current trajectory, funding, and team capability. Even if the company achieves 50% of these projections, it would represent a remarkable success story.

The Broader Vision: African Technological Independence

Underlying Terra's specific mission is a larger vision that extends across African tech development more broadly.

The vision is straightforward but profound: Africa should be able to build, maintain, and operate sophisticated technology without dependency on external powers. Not in isolation—Africa will always participate in global technology ecosystems. But with sufficient indigenous capability that no single external power can hold Africa hostage through technology control or information access.

That vision applies to defense, but also to telecommunications infrastructure, energy systems, financial networks, transportation systems, and advanced manufacturing. In each domain, Africa is currently too dependent on external actors for critical capability.

Terra is demonstrating that this vision is achievable. If defense—historically the most technical and capital-intensive domain—can be built indigenously, then less complex domains become easier.

This doesn't mean Africa rejects global partnerships or becomes protectionist. It means Africa builds sufficient internal capability that it negotiates with external partners from a position of strength, not weakness.

For founders, investors, and policymakers across Africa, Terra's story is permission. Permission to dream big. Permission to tackle hard problems. Permission to build in Africa for Africa and then extend globally. Permission to believe that Africa's young generation can solve problems that have frustrated the world for decades.

Nwachuku's comment captures this: "The only way for us to truly break ourselves from the shackles that have held us back for the last decade or two is ensuring the core resources, the core infrastructures of the continent, are entirely protected."

That's not just business strategy. That's a vision for African independence and prosperity built on technological capability.

Conclusion: The Inflection Point

We're living through a moment where Africa's relationship with technology is fundamentally shifting. For centuries, that relationship was extractive: African resources flowing out, foreign products and foreign expertise flowing in. For decades more, the relationship was dependent: Africa consuming technology and services built elsewhere, becoming more reliant on external actors for critical functions.

Terra Industries represents something different: Africa building its own sophisticated technology, solving problems that matter for African development, employing African talent, manufacturing in Africa. It's not revolutionary language. But the reality is revolutionary.

Two 22- and 24-year-olds from Nigeria, building a defense company in Abuja, raising capital from American defense investors, and deploying technology that protects $11 billion in African critical infrastructure. Five years ago, that wasn't a realistic path. Ten years ago, it wasn't even a conceivable path.

It's conceivable now because Africa's capital markets have deepened. Because African talent has proven itself capable of building sophisticated technology. Because African founders have developed credibility with global investors. Because the problems are real and the urgency is high.

Terra's success won't solve Africa's security challenges alone. Terrorism and insurgency are complex problems requiring military, political, economic, and social solutions. But Terra is addressing one critical component: the technological capability that African nations need to respond to threats in real time and protect their most valuable assets.

As African nations increasingly rely on Terra's systems instead of foreign intelligence services, the balance of power subtly shifts. African nations gain more autonomy. They develop more internal expertise. They become less dependent on external actors for fundamental national security.

From a global perspective, that's positive. A more technologically independent Africa is a more stable Africa, a more prosperous Africa, and a better partner for the global community. From an African perspective, it's essential for real development and real freedom.

Terra's founders understood this. They didn't just identify a business opportunity. They identified a path toward African technological sovereignty. The $11.75 million funding round is significant, but the larger significance is what it represents: the beginning of Africa building its own future rather than waiting for others to build it.

That's why Terra matters. That's why this moment matters. That's why the next chapter of African technology development might be written by entrepreneurs like Nathan Nwachuku and Maxwell Maduka.

FAQ

What is Terra Industries?

Terra Industries is an African defense technology company founded by Nathan Nwachuku and Maxwell Maduka that designs, manufactures, and operates autonomous defense systems, surveillance infrastructure, and AI-powered intelligence platforms for African governments and organizations. The company emerged from stealth in 2025 with an

How does Terra's technology work?

Terra's defense systems operate across three integrated layers. The detection layer uses long-range and short-range drones in the air, surveillance towers and ground drones on land, and developing maritime systems to identify threats. The analysis layer applies Terra's proprietary Artemis OS software, which aggregates sensor data and uses machine learning to detect anomalies and threats in real time. The response layer immediately alerts security and military forces with specific threat location, assessment, and response routing information to enable rapid interception.

What are the main benefits of Terra's approach?

Terra provides African governments with genuine sovereignty over their security and intelligence operations, eliminating dependency on foreign intelligence services for critical information about their own territory. The system compresses decision-making time from hours to minutes by providing real-time threat detection and analysis. The platform also enables rapid response to incidents, preventing attackers from completing objectives. Additionally, Terra's focus on African manufacturing creates skilled employment while developing indigenous defense technology capability that benefits long-term continental development.

How is Terra's revenue model structured?

Terra generates revenue through two primary mechanisms. Hardware revenue comes from government and commercial customers ordering drone systems, surveillance towers, ground-based sensors, and integrated monitoring platforms. Recurring software revenue comes from annual fees for data processing, storage, and intelligence services provided through Artemis OS. This mixed model creates both immediate revenue and predictable recurring revenue that compounds over time as customer bases grow.

Why is Terra's decision to manufacture in Africa important?

Keeping manufacturing in Africa rather than outsourcing to established defense countries serves multiple purposes. It creates skilled manufacturing jobs in African economies, signals that sophisticated technology can be built in Africa, demonstrates long-term commitment to African development beyond just capturing profits, and reduces supply chain vulnerabilities by localizing production. It also makes a powerful statement to other African founders that they can build complex hardware technology domestically and compete globally.

What is Artemis OS and why does it matter?

Artemis OS is Terra's proprietary software platform that aggregates data from all sensor types (drones, surveillance towers, radar, thermal imaging, acoustic sensors) and applies machine learning models trained on actual threat patterns to identify anomalies in real time. This represents the first African-built sovereign intelligence system, eliminating the need for African governments to depend on Western, Chinese, or Russian intelligence services for analysis of activity on their own territory. Real-time intelligence enables much faster security responses and more autonomous decision-making by African governments.

Who are the major investors backing Terra?

Terra's Series A round was led by 8VC, Joe Lonsdale's defense-focused venture capital firm, with participation from Valor Equity Partners, Lux Capital, SV Angel, and Nova Global. African investors including Tofino Capital, Kaleo Ventures, and DFS Lab also participated. The investor syndicate reflects confidence from sophisticated defense investors that Terra represents a significant opportunity in building indigenous African security technology.

What competitive advantages does Terra have against established defense contractors?

Terra's primary competitive advantages are deep understanding of African security contexts and regulatory environments, ability to design systems optimized for African conditions rather than generic global solutions, manufacturing and operations in Africa that reduce costs and improve integration with local militaries, and credibility with African military institutions due to the founders' military backgrounds and the team's 40% composition of former Nigerian military engineers. Established defense contractors struggle to match this combination of local knowledge, cost efficiency, and institutional credibility.

What are the main risks to Terra's success?

Key risks include execution complexity in scaling manufacturing and operations across multiple African nations simultaneously, regulatory and political risks that could disrupt operations in specific countries, pressure to continuously innovate in a rapidly evolving defense technology landscape, potential difficulty in future financing rounds if growth doesn't match projections or if defense investors worry about geopolitical risk, competition from established defense contractors or other African startups entering the space, and talent retention challenges in a global market for skilled engineers.

How does Terra's success impact broader African technological development?

Terra demonstrates that African founders can build sophisticated foundational technology (not just consumer-facing services) that competes globally and serves critical national needs. This success signals to other African entrepreneurs that building indigenous infrastructure technology is possible and investable. It also signals to African governments and institutions that they don't need to remain dependent on foreign powers for critical technological capability. If defense technology can be built in Africa, then telecommunications infrastructure, energy systems, transportation systems, and advanced manufacturing become more achievable, fundamentally shifting Africa's technological trajectory.

Key Takeaways

- Terra Industries represents the first African defense prime, built by Gen Z founders to provide sovereign intelligence and security capabilities without dependency on foreign powers

- The company already generates 11 billion in critical infrastructure across multiple African nations despite operating in stealth

- 40% of Terra's engineering team comes from Nigerian military backgrounds, providing genuine credibility with government customers and military institutions

- Multi-domain approach spanning air (drones), ground (surveillance towers, ground robots), and maritime (offshore infrastructure protection) demonstrates technical sophistication

- Success signals that African founders can build foundational infrastructure technology that competes globally, shifting continent's relationship with technological sovereignty

![Africa's Defense Revolution: How Gen Z Founders Are Reclaiming Continental Security [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/africa-s-defense-revolution-how-gen-z-founders-are-reclaimin/image-1-1768207034690.jpg)