FCC Cyber Trust Mark Program: UL Solutions Withdrawal & National Security Impact

Something significant just happened in the world of government cybersecurity, and honestly, it deserves more attention than it's getting. A major company overseeing the FCC's Cyber Trust Mark Program quietly withdrew from the role, and the reason reveals a troubling vulnerability in how we're securing connected devices across America.

The company in question, UL Solutions, operated as the Lead Administrator for the entire Cyber Trust Mark program. That's not a small job. They were literally writing the rules, managing the testing locations, and deciding which devices get the government-approved security stamp. Then investigators discovered something that couldn't be ignored: the company had deep financial ties to China through a joint venture with Chinese state-owned entities.

Here's the thing that keeps me up at night about this situation: if UL Solutions hadn't been caught, devices approved through this program could have carried hidden vulnerabilities introduced at Chinese testing facilities. We're not talking about theoretical risks. We're talking about cameras in government buildings, smart devices on military bases, and IoT infrastructure across federal agencies. All potentially compromised before they ever left the factory.

This article digs into what actually happened, why it matters far beyond just one company's withdrawal, and what this tells us about the massive gap between our cybersecurity ambitions and the reality of global supply chains.

TL; DR

- UL Solutions withdrew from overseeing the FCC's Cyber Trust Mark Program after investigators discovered ties to China National Import and Export Commodities Inspection Corporation

- Three testing locations in China were flagged as "particularly alarming" by national security investigations

- The Cyber Trust Mark program requires all IoT devices sold to the U.S. government to be certified by January 4, 2027, covering everything from security cameras to smart TVs

- Supply chain vulnerability: Chinese joint venture partners could theoretically insert backdoors or vulnerabilities during the testing and certification process

- Broader implications: This withdrawal exposes how difficult it is to maintain security standards when manufacturing and testing infrastructure is globally distributed

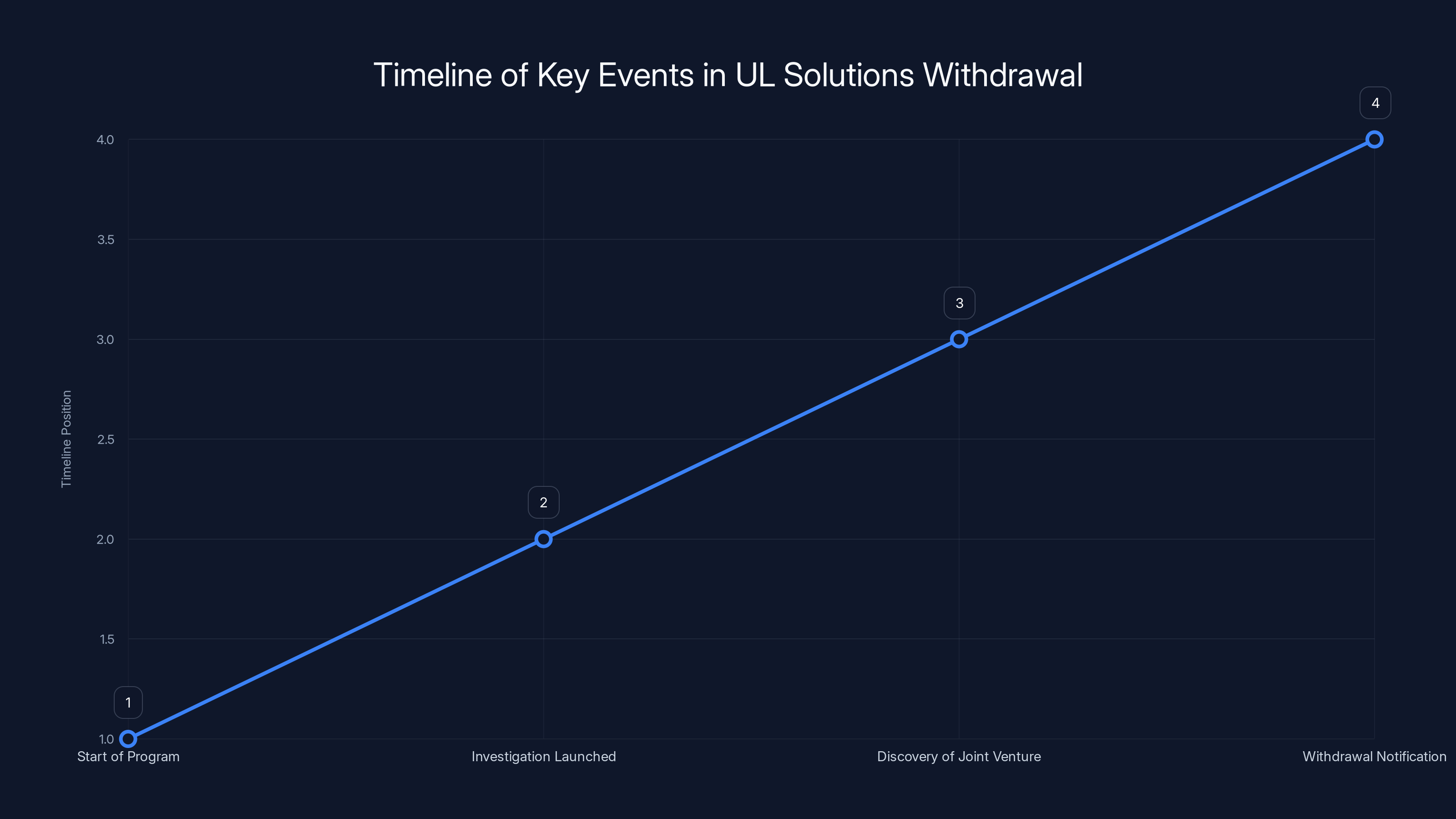

The timeline highlights the sequence of events leading to UL Solutions' withdrawal as Lead Administrator, with the discovery of a joint venture being a pivotal moment. (Estimated data)

Understanding the Cyber Trust Mark Program

What Is the Cyber Trust Mark?

The Cyber Trust Mark isn't just another label on a box. It's an official government certification that signals an IoT device meets minimum cybersecurity requirements set by the Federal Communications Commission. Think of it like the FDA approval for food, except for connected devices.

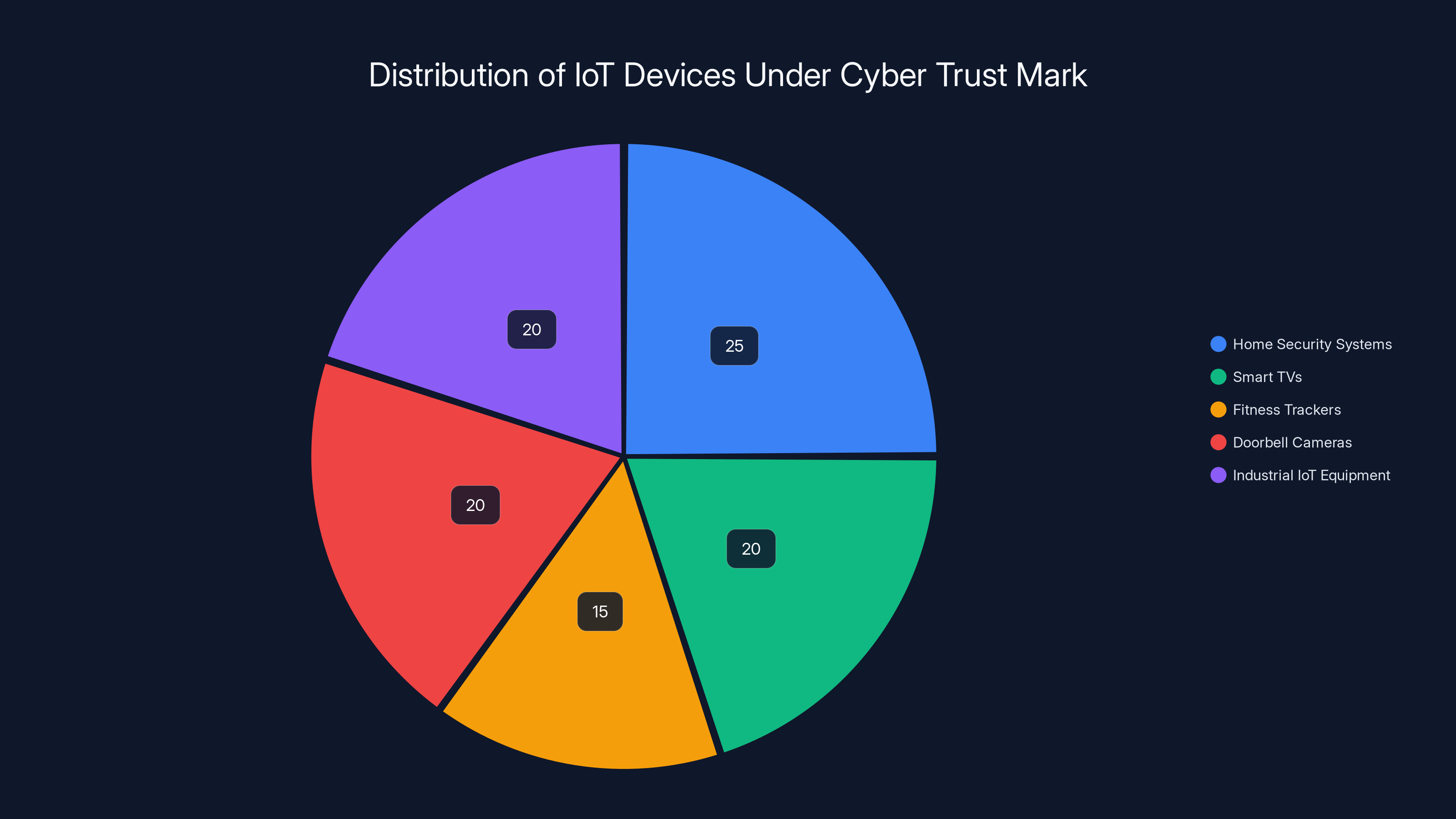

Starting January 4, 2027, every IoT device sold to the U.S. government has to carry this mark. But here's what makes it bigger than just government procurement: the standards are designed to apply to all IoT devices sold in America, which means home security systems, smart TVs, fitness trackers, doorbell cameras, and even industrial IoT equipment.

The program emerged from the Biden administration's push to strengthen national cybersecurity posture. After years of watching adversaries exploit vulnerable IoT devices as entry points into critical infrastructure, someone finally said, "We need a baseline standard." The Cyber Trust Mark was supposed to be that baseline.

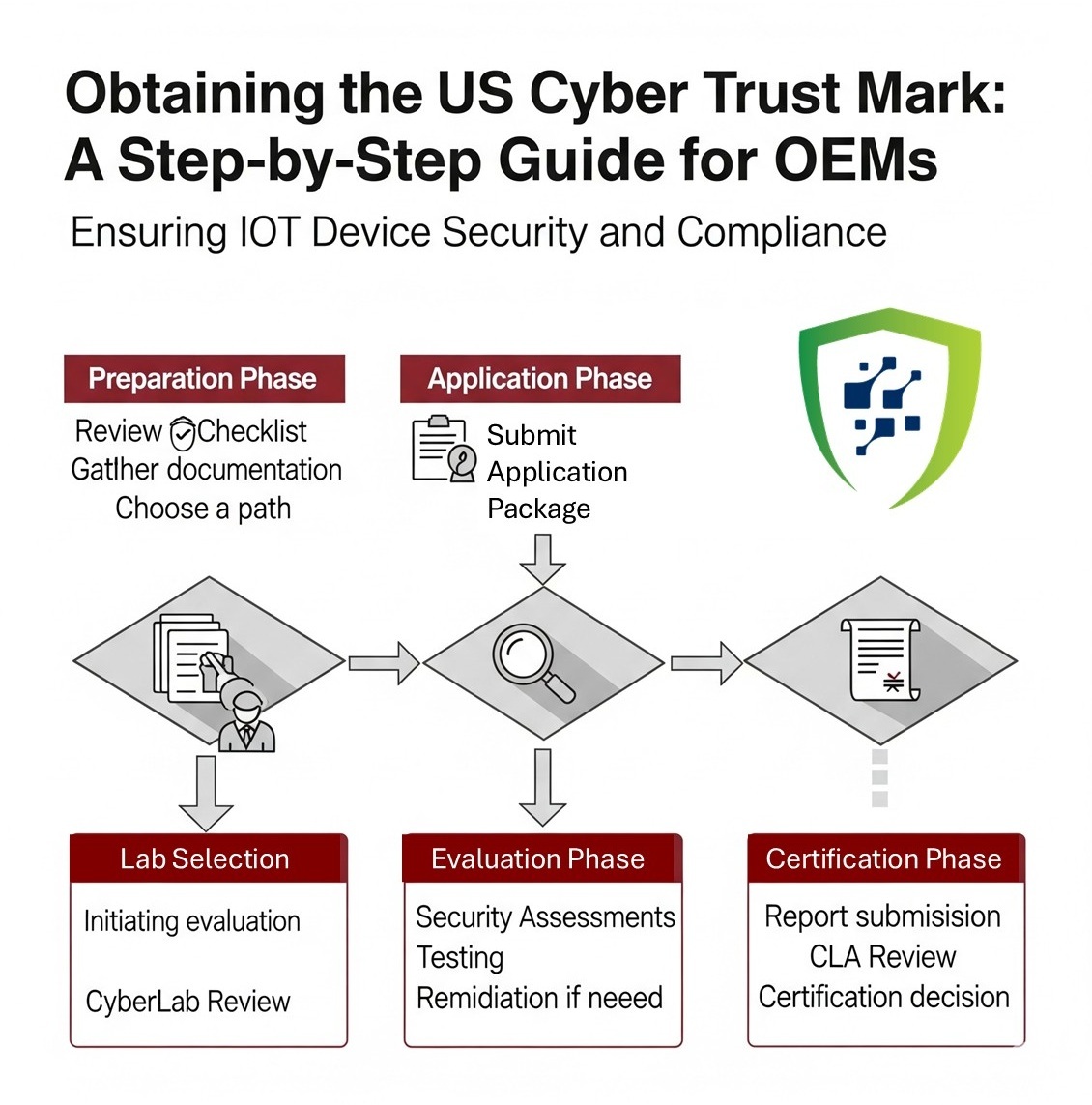

How the Program Actually Works

The program operates through a multi-layered approval structure. Manufacturers submit their devices for testing. Authorized testing laboratories verify that devices meet technical requirements for secure firmware updates, known vulnerability management, and basic security hygiene. Once approved, devices get the certification and can be marketed with the official Cyber Trust Mark.

UL Solutions was the Lead Administrator, meaning they didn't just run one testing lab. They were responsible for developing the technical recommendations, managing the entire program architecture, establishing surveillance practices, and designing the rules for how devices get certified. It's like asking someone to be both the restaurant inspector and the owner of the restaurants being inspected.

The program covers a massive range of devices. We're talking about smart home devices, medical IoT equipment, industrial sensors, network infrastructure, and consumer electronics. The scope is intentionally broad because vulnerabilities don't discriminate between consumer and enterprise devices.

The Original Vision and Its Challenges

When the program launched, the vision was straightforward: create a market signal that incentivizes manufacturers to build more secure devices. Consumers and government procurement officers would prefer certified devices. Manufacturers would compete on security. Market forces would push the industry toward better practices.

The challenge always lurked beneath this optimistic vision: testing and certification infrastructure is global. Devices come from everywhere. Components are made everywhere. Even devices manufactured in the U.S. often use foreign-made components or get tested internationally before final assembly.

This global reality creates decision points that look simple but carry massive implications. Who runs the testing labs? Who certifies the certifiers? What happens when a major certification company has financial incentives tied to countries with different security interests than ours?

These questions hung in the air until the investigation into UL Solutions forced them into the open.

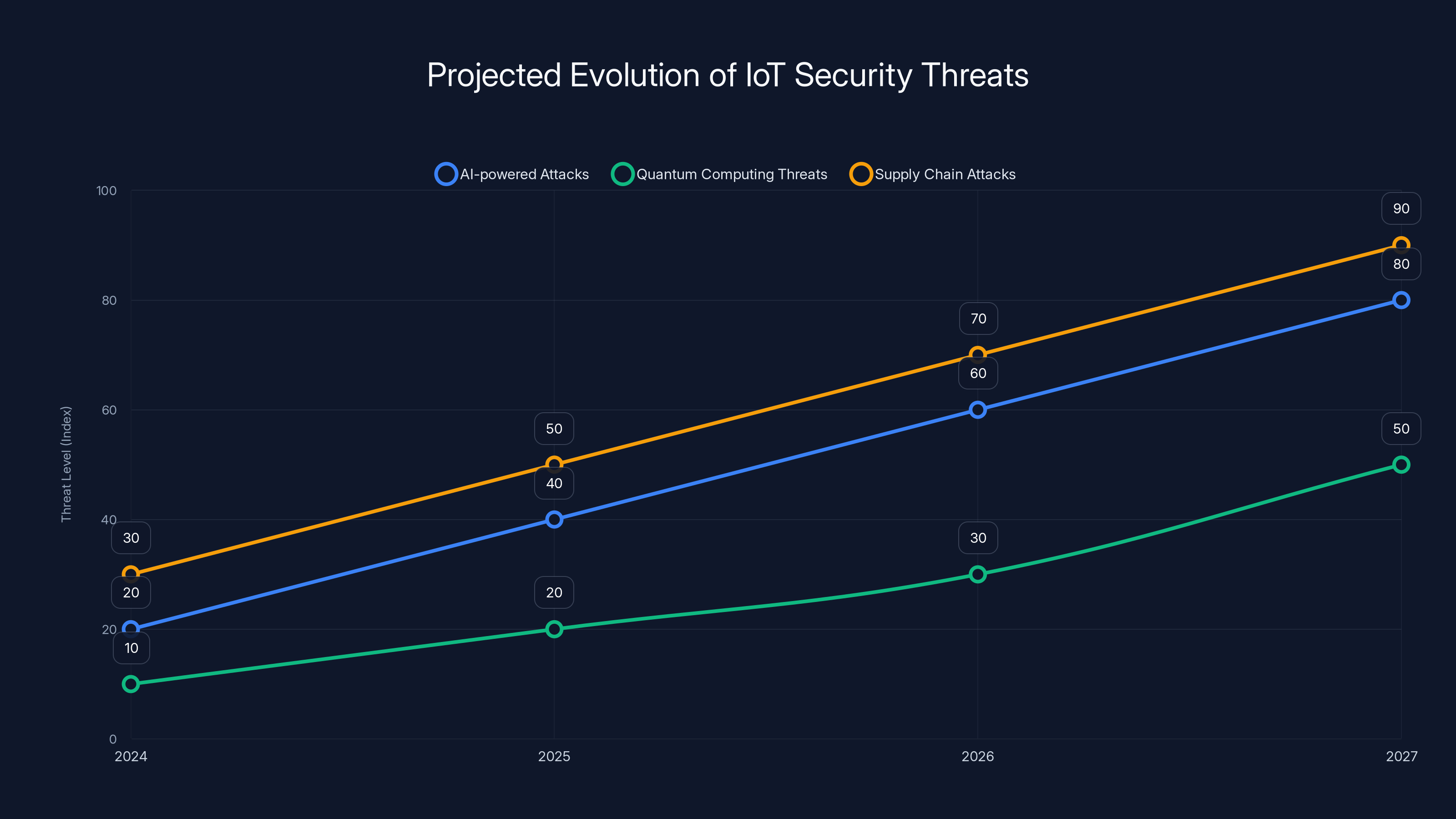

The chart illustrates projected increases in various IoT security threats by 2027, highlighting the need for adaptable security standards. Estimated data.

The UL Solutions Withdrawal: What Happened

Timeline of Events and Discovery

UL Solutions operated as the Cyber Trust Mark program's Lead Administrator from the beginning. For months, they worked on developing the technical framework, establishing testing procedures, and preparing the infrastructure for the January 2027 deadline.

Then came the investigation. The FCC launched a national security investigation into its Council on National Security, examining potential vulnerabilities in how the program was being overseen. As investigators dug into UL Solutions' corporate structure, they discovered something problematic: the company operated a joint venture with China National Import and Export Commodities Inspection Corporation, a state-owned Chinese enterprise.

This wasn't a minor partnership. The joint venture operated 18 testing locations in China. Of those 18 locations, three were flagged as particularly alarming in the investigation report. That's not just a red flag. That's a collection of red flags being waved simultaneously.

UL Solutions' VP, Chanté Maurio, sent a letter to the FCC formally notifying them of the company's withdrawal as Lead Administrator. The letter, dated shortly after the security concerns surfaced, stated that the company remained "committed to the success of the Program" but acknowledged that continuing in this role would be problematic given the circumstances.

Why the Chinese Ties Mattered

On the surface, having a Chinese joint venture might seem unremarkable. Lots of companies do international business. UL Solutions could rightfully point out that they employ people globally and serve international markets. That's just how modern business works, right?

Except this isn't about normal international commerce. This is about the company responsible for certifying devices that the U.S. government will use in sensitive contexts. FCC Chairman Brendan Carr warned publicly that the arrangement created a potential "back door to CCP sabotage." That's not casual language. That's a chairman of a federal agency explicitly stating that the certification process could be compromised.

The specific concern works like this: if testing facilities in China are operated by a joint venture where Chinese state interests have a voice, those facilities could potentially introduce vulnerabilities during the testing process. A device might arrive for testing with secure code, but leave the Chinese testing facility with a backdoor installed. The device passes certification because the testing facility itself is compromised.

Is this speculation? Partially. But it's informed speculation based on historical precedent. We've seen Chinese state-affiliated actors insert vulnerabilities into hardware and software before. We've documented supply chain attacks where components were compromised at the manufacturing or testing stage.

Representative John Moolenaar, head of the House Select Committee on the CCP, said it plainly: "Chinese companies with ties to the CCP could use this program to get a U.S. government-backed stamp of approval." That's the vulnerability. Not hypothetical. Not theoretical. A path that should have been blocked but wasn't.

The Withdrawal Letter and Its Implications

UL Solutions' withdrawal letter acknowledged the work they'd done developing the program framework and offered to continue supporting the transition. They didn't fight the decision. They didn't argue that their Chinese operations were separate from their cybersecurity work. They accepted that continuing in this role was untenable.

But here's what the withdrawal actually reveals: nobody caught this problem proactively. It took an active investigation to surface the concern. UL Solutions submitted their application, got selected, started the work, and nobody questioned the Chinese joint venture until investigators specifically looked into it.

This suggests a broader gap in how we're vetting entities before giving them control over critical cybersecurity infrastructure. Companies submit applications, we evaluate their technical credentials, and we move forward. The geopolitical risk assessment apparently happens later, if at all.

National Security Implications

Why IoT Device Security Matters at the Federal Level

You might wonder why the government cares so much about IoT devices. These are cameras and sensors, not nuclear weapons. Why the urgency?

IoT devices are attack vectors. A compromised camera in a federal building isn't just a privacy problem. An attacker with access to that device might use it as a pivot point to access the building's network. A vulnerable smart meter in a critical infrastructure facility could be used for reconnaissance. Connected sensors in power substations could be manipulated to cause outages.

The Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and intelligence agencies all rely on thousands of connected devices. So do hospitals, water treatment facilities, and transportation systems receiving federal funding. If those devices carry hidden vulnerabilities, they become liabilities rather than assets.

The scale is enormous. A single manufacturer might ship hundreds of thousands of devices that get deployed across federal facilities. If those devices have a backdoor, the attack surface expands exponentially. One vulnerability becomes a door into thousands of locations.

Supply Chain Attack Scenarios

Let's walk through how a supply chain attack would actually work in this context, because it's important to understand the mechanics.

Scenario One: A device manufacturer submits a camera for Cyber Trust Mark certification. The device is manufactured in the U.S., but before final certification, it gets shipped to a Chinese testing facility (part of the UL Solutions joint venture) for third-party validation. The testing facility has the capability to modify firmware during testing. They install a backdoor that allows remote access. The camera passes all tests because the testing facility itself is controlled by the attackers. The camera gets certified, shipped to U.S. government facilities, and the attackers have a foothold in those facilities.

Scenario Two: A supply chain compromise occurs at the component level before the device even reaches testing. A microcontroller manufactured in China includes hidden functionality. The U.S. manufacturer assembles the final device, sends it to testing at a compromised facility, and nobody detects the compromised component because the testing procedure doesn't specifically look for it. Again, the device gets certified and deployed.

Scenario Three: The joint venture operates as an intelligence collection point. Devices going through testing are photographed, analyzed, and data is sent back to Chinese intelligence services. The actual devices might not be compromised, but the testing process becomes a reconnaissance operation revealing what devices the U.S. government is deploying in sensitive locations.

None of these scenarios are theoretical. Each one represents an attack pattern we've seen before or know to be technically feasible.

Historical Precedent for Supply Chain Compromise

We don't have to guess at whether this kind of attack is possible. We have examples.

The Solar Winds attack showed how a software company's build infrastructure could be compromised, affecting thousands of customers including government agencies. Attackers inserted malicious code into legitimate updates, and the victims were elite organizations with significant security budgets.

The Huawei situation demonstrated how components from a manufacturer with state ties can create persistent security concerns. Even when Huawei products functioned normally, the possibility of state-directed backdoors was enough for U.S. and allied governments to restrict their use in critical infrastructure.

The Juniper Networks incident revealed that state actors had apparently placed backdoors in network equipment used by intelligence agencies and military organizations. The backdoors persisted for years before detection.

These incidents show that supply chain compromise isn't hypothetical. It's practiced. It's effective. And it's specifically something that Chinese state-affiliated actors have engaged in.

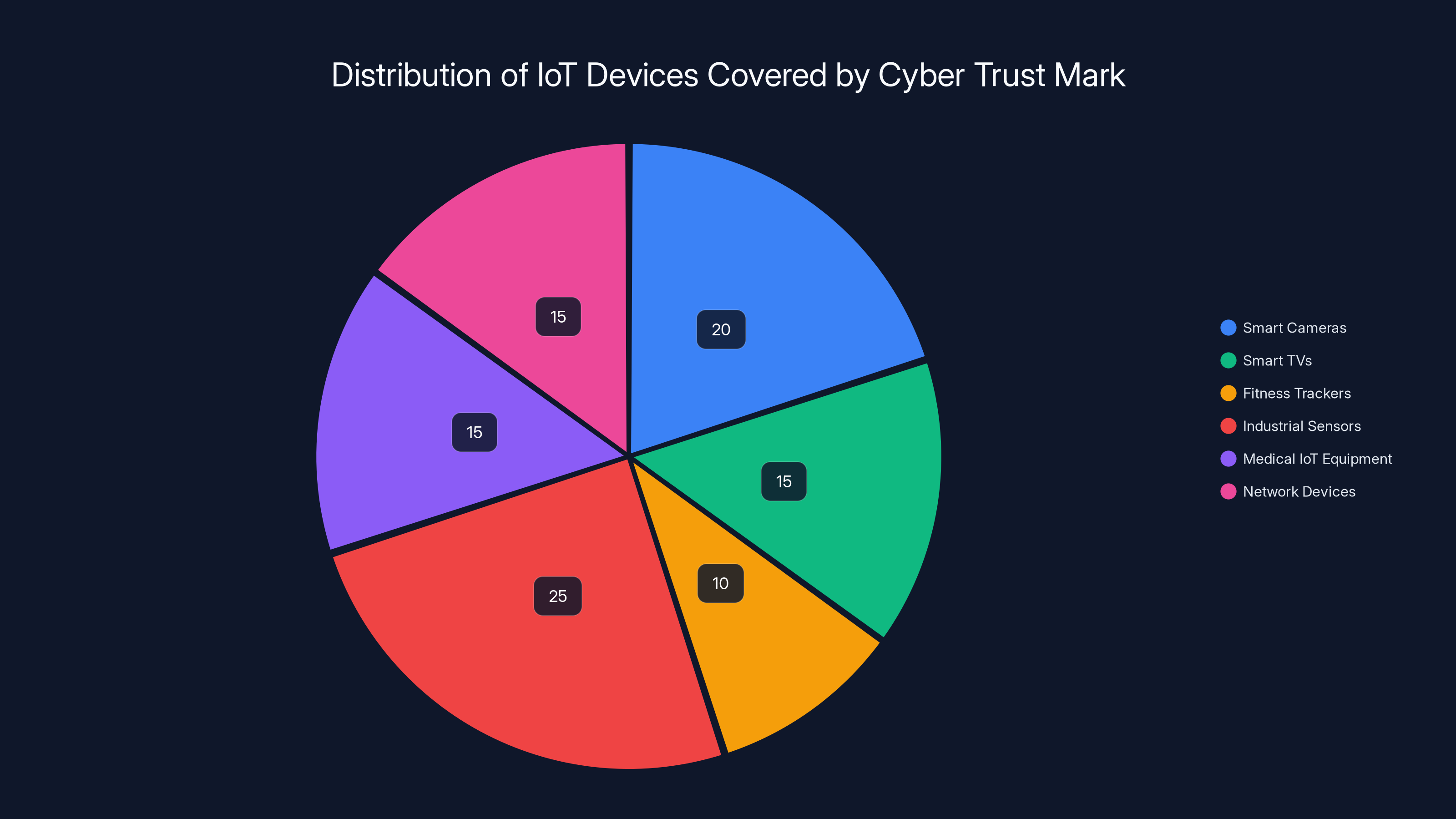

Estimated data shows a diverse range of IoT devices covered by the Cyber Trust Mark, with industrial sensors and smart cameras being the most common.

The Broader Cybersecurity Strategy Problem

Attempting to Certify Security in a Global Supply Chain

Here's the fundamental problem that the UL Solutions situation exposed: we're trying to certify cybersecurity in an ecosystem that's fundamentally global and fundamentally vulnerable to state-level interference.

The Cyber Trust Mark program assumes that testing facilities run independently and honestly. It assumes that a device certified in one location will maintain its security properties when deployed elsewhere. It assumes that the certifying entity has no conflicting interests.

But manufacturing reality doesn't match these assumptions. Devices are made in one country, tested in another, and deployed in a third. Components come from dozens of suppliers across multiple continents. Intellectual property is licensed from entities in various jurisdictions. The idea of a purely secure supply chain is almost quaint.

So how do you certify something when the supply chain is inherently international? You implement controls and verification points. You require testing at approved facilities. You verify that those facilities meet security standards. You audit the process.

And you hope that nobody with competing interests gets control of the process. Which is exactly what happened here until someone looked close enough to notice.

Trust Assumptions That Failed

The program implicitly trusted that an American company running certification infrastructure wouldn't allow foreign state actors to compromise that infrastructure. That seems like a reasonable assumption, except it fell apart immediately.

UL Solutions didn't start the joint venture recently. This wasn't a new development discovered by investigators. The company had been operating with these Chinese partnerships for years while simultaneously taking on responsibility for the nation's IoT device certification program.

Somebody should have asked: "Do we trust a company with Chinese state-owned joint venture partners to oversee a security program where all devices are verified as safe for U.S. government use?" Apparently, that question didn't get asked or didn't get asked forcefully enough.

This suggests a gap between security theory and security practice. In theory, we understand that state actors pose unique risks. In practice, we sometimes accept arrangements that enable those risks because companies are well-established, technically competent, and seem trustworthy.

Finding a Successor Administrator

What the FCC Needed to Do

UL Solutions' withdrawal created an immediate operational problem. The Cyber Trust Mark program had a deadline: January 4, 2027. Devices had to be certified by that date. Testing infrastructure had to be in place. Procedures had to be documented. Standards had to be finalized.

The FCC suddenly needed to find a new Lead Administrator or take on the role itself. Both options presented challenges.

Taking on the role internally meant federal agencies would have to immediately expand their cybersecurity workforce, build testing infrastructure, and manage a complex certification program. Government moves slowly, and a government-run certification program might lack the technical agility needed to respond to emerging threats.

Finding a successor meant vetting a new company carefully enough to avoid repeating the same mistake. That company would need to be technically competent, have no problematic foreign ties, and be willing to take on a complex role quickly.

The Solution: Distributed Responsibility

The FCC ultimately decided to transition the Lead Administrator duties to the agency itself, with support from other entities. This distributed the responsibility and reduced the risk that any single company could compromise the program.

This approach has advantages and disadvantages. On the plus side, removing a private company with Chinese ties eliminates the obvious vulnerability. The FCC has federal oversight and can't be influenced by foreign governments in the same way a corporation might be.

On the minus side, government agencies move slowly. The FCC is not a technology startup. Building testing infrastructure, establishing certification procedures, and managing thousands of devices requires resources and speed that large government agencies sometimes struggle to muster.

The transition period between UL Solutions' withdrawal and the FCC's assumption of full responsibility created uncertainty. Manufacturers had to know what standards they were building to. Testing requirements needed to be stable. Any gap in leadership risked pushing the January 2027 deadline or creating a situation where devices get certified under different standards.

Alternative Approaches Considered

Inside government, there was discussion about different models for oversight. Some advocated for creating a public-private partnership with multiple independent testing facilities overseen by a trusted administrator. Others suggested following the model of similar programs in allied countries like Canada or the UK, which have different oversight structures.

The challenge with any distributed model is maintaining consistency. If multiple testing facilities operate independently, how do you ensure they're applying standards uniformly? A device certified by one facility should be equivalent to a device certified by another facility, or the entire system loses credibility.

Centralized government oversight solves the consistency problem but creates the agility problem. It also means that any gap in government funding or political will directly impacts the program. A private company has financial incentive to keep the program running. A government program depends on congressional appropriations and agency priorities that can shift.

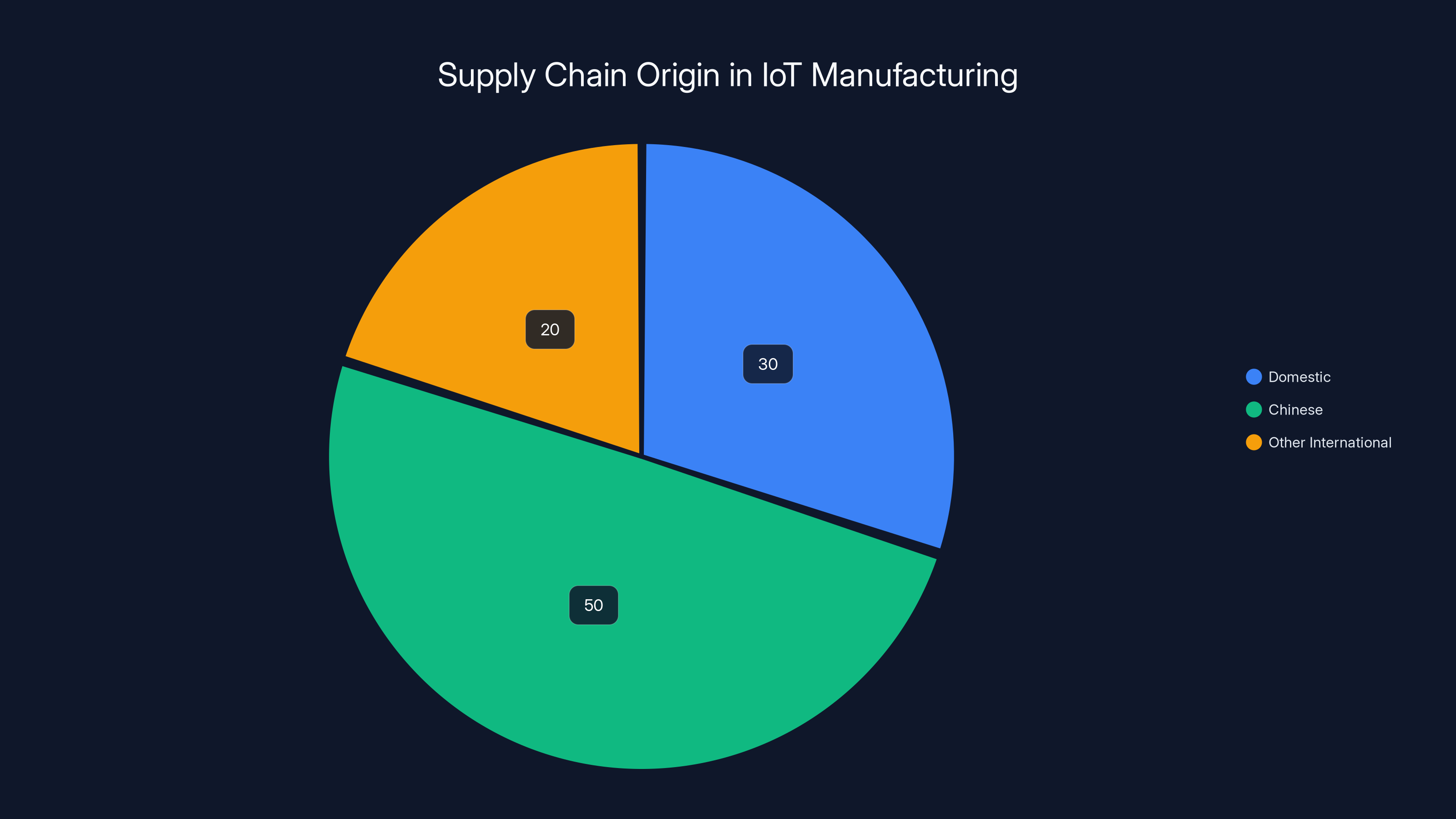

Estimated data shows that 50% of IoT manufacturing supply chains have Chinese origins, highlighting potential supply chain risks. Domestic supply chains account for 30%, offering a marketing advantage.

Government Procurement and Supply Chain Security

Current Federal Procurement Requirements

Federal agencies have detailed procurement requirements designed to ensure they're not buying compromised equipment. These requirements specify that contractors must certify the origin of components, use approved manufacturers, and maintain secure supply chains.

But here's the tension: these requirements make procurement more expensive. Choosing components from pre-approved vendors costs more than choosing from the cheapest global supplier. Requiring supply chain transparency adds compliance overhead. Building security into products increases manufacturing costs.

Budgets are finite. So procurement officers often face a choice between the most secure option and the most affordable option. Sometimes they choose security. Sometimes cost wins.

The Cyber Trust Mark was supposed to simplify this equation. Devices with the mark automatically meet baseline security standards, so procurement officers could choose certified devices without running extensive security evaluations themselves. The mark would become a trusted signal.

Except the mark only works if the certification process is actually trustworthy. Which means the entire burden of security shifts from thousands of procurement officers to whatever entity is certifying devices.

Risk Transfer vs. Risk Reduction

There's an important distinction between transferring risk and actually reducing risk. The Cyber Trust Mark transfers risk management from individual procurement officers to a centralized certifying entity. That can be more efficient if the certifying entity is trustworthy.

But it also concentrates the attack surface. Instead of thousands of devices with individual vulnerabilities, you get a centralized certification process that, if compromised, compromises everything it approves.

The UL Solutions situation demonstrates exactly this problem. A single company's conflict of interest potentially affected the security posture of all devices certified through their process.

Effective supply chain security requires acknowledging this trade-off. Centralized certification is more efficient but creates a single point of failure. Distributed verification is more resilient but more expensive and slower.

Implications for Technology Companies and Manufacturers

New Requirements for Device Manufacturers

The Cyber Trust Mark program affects companies across the consumer electronics, IoT, and industrial automation spaces. Manufacturers had to prepare to certify devices for federal procurement by the January 2027 deadline.

UL Solutions' withdrawal created uncertainty about what the certification process would actually look like under FCC oversight. Manufacturers had been building devices to specifications developed by UL Solutions. Would those specifications change? Would testing requirements shift? Would the timeline hold?

For manufacturers, this meant either pausing product development pending clarification, or continuing with the original specifications and hoping the FCC would maintain continuity. Neither option is ideal.

Companies with products already developed had to decide whether to pursue certification immediately or wait for the new process to stabilize. Companies in development could choose to wait for clarity, but that risked missing the January 2027 deadline.

Supply Chain Implications

The investigation into UL Solutions sparked broader discussion about supply chain risk in IoT manufacturing. If the company overseeing the certification program had Chinese state ties, what about the manufacturers themselves?

Many major IoT device manufacturers have manufacturing facilities in China or source components from Chinese suppliers. Some have Chinese investors. This doesn't automatically mean their devices are compromised, but it does mean that supply chain risk is endemic in the industry.

For manufacturers wanting to build confidence with government procurement, the implicit message was: carefully manage your supply chain and be prepared to document it. Companies with fully domestic supply chains have a marketing advantage. Companies with transparency about their supply chains can reduce government procurement risk.

This may actually benefit some manufacturers. Companies that have deliberately structured their supply chains for security and can demonstrate transparency might win more government contracts, even if their products are slightly more expensive.

Certification Costs and Compliance

Manufacturers now face the prospect of getting devices certified under a new process with potentially different requirements. This costs money. Testing, documentation, compliance verification, and potential redesigns to meet new standards all add up.

Smaller manufacturers face a particular challenge. Large companies can absorb certification costs across millions of units. Small companies might struggle. This could create a barrier to entry for smaller innovation-driven companies and entrench larger established players.

Government sometimes tries to mitigate this by offering certification assistance to small businesses or streamlining requirements for smaller manufacturers. But these programs are typically underfunded relative to demand.

Estimated data shows that home security systems and smart TVs make up the largest share of IoT devices requiring Cyber Trust Mark certification, each accounting for 20-25% of the total.

Lessons for Cybersecurity Strategy

Vetting Entities with National Security Responsibilities

The UL Solutions case demonstrates that we need better processes for vetting organizations before giving them control over critical cybersecurity infrastructure. Right now, the process seems to work like this: company applies, we evaluate technical credentials, we grant authority.

A better process would add explicit national security review. Before an organization takes on a role this sensitive, investigate: What are the company's foreign partnerships? Who are the major shareholders? What countries do significant business operations happen in? Are there any state actors with influence over the organization?

This isn't about discriminating against international companies. It's about understanding risks clearly before assuming them.

For organizations already in sensitive roles, periodic review makes sense. Companies change over time. Ownership structures shift. New partnerships form. A company might start with trustworthy governance and gradually drift toward riskier arrangements.

Decentralization and Resilience

One lesson from the UL Solutions situation is that concentrating too much authority in a single entity creates risk. If the program had been designed with multiple independent testing facilities from the start, no single company's withdrawal would have derailed everything.

Resilience in security systems often comes from decentralization. Instead of one certifier, have multiple competing certifiers who meet minimum standards. Instead of one administrator, have distributed governance with checks and balances.

This increases operational complexity and cost. It's slower than centralized authority. But it reduces the likelihood that a single compromise brings down the entire system.

Transparency and Public Accountability

UL Solutions operated with Chinese state ties for years before it became an issue. This wasn't classified information. The company's structure was available to people who looked. But apparently, the vetting process didn't look, or didn't look hard enough.

Better transparency about the organizations running critical programs helps Congress, oversight bodies, and the public understand the risks being assumed. This doesn't mean publishing classified information about security procedures. It means being clear about conflicts of interest and structural vulnerabilities in the oversight apparatus.

When Congress is briefed on a national security matter, they should understand not just what the technical problem is, but whether there are organizational conflicts of interest in how the solution is being implemented.

International Considerations

How Other Countries Handle IoT Certification

The United States isn't alone in trying to certify IoT device security. Canada, the UK, EU countries, and Australia have all launched or are developing similar programs. The interesting question is whether they're avoiding the same pitfalls.

The EU's approach has been more cautious. They're building certification infrastructure more slowly, with more distributed authority among national governments and EU agencies. This is slower but arguably more resilient to the kind of single-point-of-failure issue that the U.S. program experienced.

Canada's program is smaller and more focused on critical infrastructure rather than all IoT devices. This narrower scope means fewer devices are affected if something goes wrong, but it also limits the scale of security improvement.

The UK has been particularly focused on supply chain transparency, requiring companies to declare component origins and manufacturing locations. This approach emphasizes transparency over centralized certification.

Allied Coordination and Standards Alignment

One advantage the U.S. has is the ability to align standards with allied nations. If the Cyber Trust Mark standards are compatible with equivalent programs in other English-speaking countries (Canada, UK, Australia), then devices certified in one country could potentially be recognized in others.

This creates pressure for standards harmonization. Manufacturers benefit from being able to certify devices once and sell them across multiple markets. Governments benefit from being able to leverage each other's testing infrastructure.

But harmonization also creates risks. If all allied nations use similar standards and those standards are compromised, the compromise affects everyone. On the other hand, completely separate standards means duplication of effort and manufacturers facing multiple certification regimes.

The solution involves finding the middle ground: compatible standards that allow some sharing of testing infrastructure, but with enough national discretion that each government can maintain security oversight for devices used domestically.

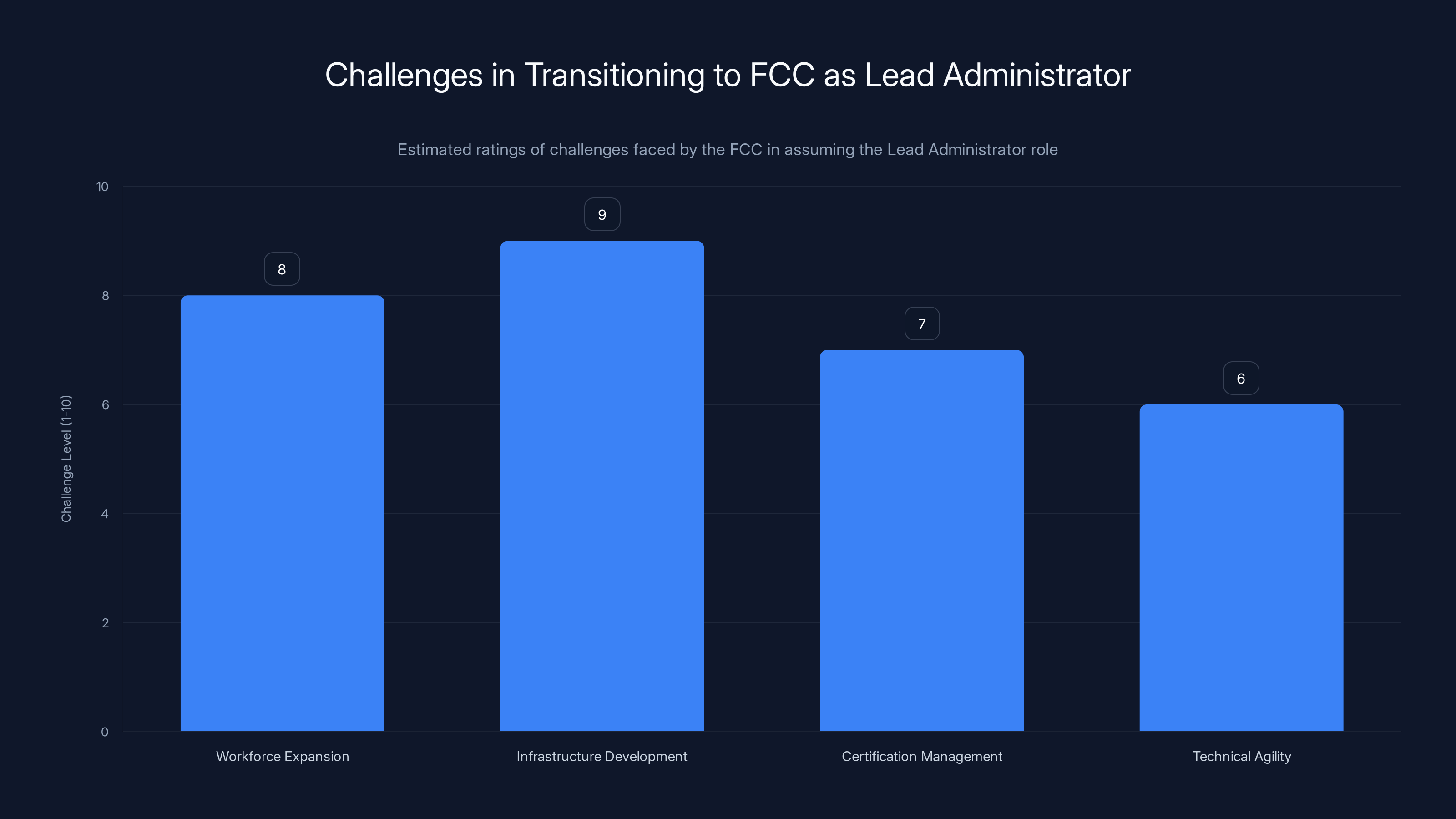

The FCC faces significant challenges in workforce expansion and infrastructure development, with high estimated difficulty levels. (Estimated data)

Looking Forward: The Future of IoT Security Standards

Emerging Threats and Evolving Requirements

The Cyber Trust Mark was designed with today's threats in mind. But the threat landscape evolves continuously. By 2027, when the program goes into full effect, new vulnerabilities will have been discovered, new attack patterns will have emerged, and manufacturers will have found creative ways to work around security requirements.

The program needs to be designed for evolution, not just implementation. That means standards should be revisable, testing procedures should be updatable, and the governance structure should allow for rapid response to new threats.

AI-powered attacks are one emerging area. Machine learning can be used to analyze devices for vulnerabilities at scale or to craft personalized exploits. Quantum computing could theoretically break encryption standards. Supply chain attacks continue to evolve in sophistication.

A certification program designed in 2024 that's never updated will be fighting yesterday's threats by 2027.

Market Dynamics and Competition

One question that will shape the program's success is whether the Cyber Trust Mark actually influences market behavior. Will consumers prefer certified devices? Will procurement officers demand them? Will manufacturers invest in security improvements to get certified?

For this to work, the mark needs to mean something to the market. It needs to be trustworthy enough that people actually care about it. The UL Solutions situation damaged that trust before the program even launched at scale.

If the program becomes widely adopted, we'll likely see market differentiation. Premium manufacturers will market certified devices and charge a premium. Value manufacturers might skip certification and compete on price. Over time, market forces might eliminate the difference as competition drives prices down and certification costs decrease.

But that only happens if the certification process remains trustworthy and the market sees the mark as valuable.

Technical Evolution

The standards embedded in the Cyber Trust Mark will evolve. Firmware update mechanisms will be refined. Vulnerability disclosure procedures will be improved. Testing methodologies will become more sophisticated.

The question is whether this evolution will outpace adversary innovation. Security is always a race between defenders and attackers. Certification programs need to stay ahead of attack sophistication, not just validate current best practices.

One way to stay ahead is to make the certification criteria intelligence-driven. If security researchers discover a new class of vulnerabilities, testing procedures should be updated quickly to detect them. If attack patterns shift, certified devices should be re-evaluated.

This requires resources, expertise, and flexibility. A government-run program can achieve this, but it requires ongoing investment and priority.

Recommendations for Government and Industry

For Government Agencies

First, establish explicit vetting criteria for any organization given responsibility for critical cybersecurity infrastructure. This should include foreign partnership review, shareholder analysis, and explicit consideration of any potential conflicts of interest.

Second, implement ongoing oversight and audit procedures. Organizations change over time. Regular review ensures that initial risk assessment remains valid.

Third, design for resilience. Avoid concentrating too much authority in a single entity. Build the program with distributed authority, multiple testing facilities, and checks and balances.

Fourth, invest in program stability and evolution. The Cyber Trust Mark needs steady funding and expertise to remain relevant as threats evolve. This means maintaining a team of security experts, updating standards regularly, and staying ahead of emerging attack patterns.

For Manufacturers and Technology Companies

First, prepare for certification seriously. This isn't a checkbox compliance exercise. Building truly secure devices requires investment in design, testing, and ongoing maintenance.

Second, understand your supply chain. Know where your components come from. Understand the security posture of your suppliers. Be prepared to document and verify this information to procurement officers.

Third, engage with the certification process constructively. The standards are being developed now. Industry input helps ensure that certification requirements are realistic and actually improve security without being impossibly expensive to achieve.

Fourth, maintain security over time. Devices will be deployed for years after certification. Plan for discovering vulnerabilities, releasing updates, and supporting devices in the field. The mark means you've certified security, not that devices never have problems.

For Procurement Officers

First, don't treat the Cyber Trust Mark as a complete security solution. It's a baseline certification, not a guarantee. Use it as one input into your security evaluation, not the only input.

Second, perform supply chain due diligence on manufacturers. Understand where devices are manufactured, where components come from, and whether the manufacturer's supply chain has any security vulnerabilities.

Third, plan for device lifecycle management. A device certified in 2025 will need security updates in 2026, 2027, and beyond. Budget for patch management, firmware updates, and potential replacement of devices that can't be updated.

Fourth, maintain relationships with multiple manufacturers. Avoid becoming so dependent on a single vendor that supply chain disruptions affect your entire operation.

FAQ

What is the Cyber Trust Mark Program?

The Cyber Trust Mark Program is a U.S. government initiative that certifies IoT devices as meeting baseline cybersecurity requirements. Starting January 4, 2027, all IoT devices sold to the U.S. government must carry this certification. The program also applies to IoT devices used in sensitive sectors and increasingly to consumer devices sold in the U.S. market.

Why did UL Solutions withdraw from the program?

UL Solutions withdrew after investigators discovered the company operated a joint venture with China National Import and Export Commodities Inspection Corporation, a state-owned Chinese entity. Of the 18 testing locations the joint venture operated in China, three were flagged as "particularly alarming" in a national security investigation. FCC Chairman Brendan Carr stated the arrangement created a potential "back door to CCP sabotage," making it untenable for the company to remain the Lead Administrator.

How does the Cyber Trust Mark certification process work?

Manufacturers submit IoT devices for testing at approved facilities. Testing verifies that devices meet technical requirements for secure firmware updates, known vulnerability management, and security hygiene. Once approved, devices receive the Cyber Trust Mark certification, signaling to government procurement officers and consumers that the device meets government-verified security standards.

What devices are covered by the Cyber Trust Mark Program?

The program covers all IoT devices sold to the U.S. government, including smart cameras, smart TVs, fitness trackers, industrial sensors, medical IoT equipment, network devices, and smart home devices. The standards are also designed to apply broadly to IoT devices sold in the U.S. market.

What are the supply chain risks in IoT device certification?

If testing facilities or manufacturing facilities are controlled by state actors with interests opposed to the U.S., they could compromise devices during testing or manufacturing. This could include installing backdoors, inserting vulnerabilities, or conducting reconnaissance on devices being deployed. These supply chain attacks are feasible because they occur during legitimate testing and manufacturing processes.

How will the FCC manage the Cyber Trust Mark Program now that UL Solutions has withdrawn?

The FCC transitioned the Lead Administrator duties in-house, with support from other federal agencies and private sector partners. This distributed the responsibility and eliminated the single point of failure that UL Solutions represented. The agency now directly oversees testing facility certification, standards development, and device approval processes.

Why is government oversight of IoT device security important?

IoT devices are attack vectors that adversaries use to gain access to networks and critical infrastructure. A compromised device in a federal building could provide attackers with network access. Compromised devices across thousands of government locations could create widespread vulnerabilities. Establishing baseline security standards helps prevent these risks at scale.

What should companies do to prepare for Cyber Trust Mark certification?

Manufacturers should invest in secure device design, implement robust firmware update mechanisms, establish vulnerability management procedures, and ensure their supply chains are secure and auditable. Companies should also engage with the certification process to understand requirements and plan development timelines accordingly.

How does the Cyber Trust Mark differ from other security certifications?

Unlike certifications focused on individual features or compliance frameworks, the Cyber Trust Mark emphasizes baseline security properties that are government-verified. It's designed to be a market signal that procurement officers and consumers can rely on, rather than requiring individual security evaluation of each device.

What happens if a certified device is found to have security vulnerabilities after deployment?

The device manufacturer is responsible for developing and releasing security patches. Procurement officers and users remain responsible for applying updates. The certification validates that the device has mechanisms for receiving updates and that the manufacturer has processes for managing vulnerabilities, but it doesn't guarantee the device will never have security problems.

Conclusion

The withdrawal of UL Solutions from the FCC's Cyber Trust Mark Program represents a critical moment in how America approaches government cybersecurity. On the surface, it's a personnel change in an oversight structure. Dig deeper, and it reveals a fundamental tension in our security posture: we're trying to build trustworthy systems in an environment where trust is increasingly difficult to establish.

Here's what actually happened: a company with deep financial ties to Chinese state-owned entities was given responsibility for certifying that devices were secure for U.S. government use. This company could have introduced vulnerabilities into the testing process, compromised devices before they reached federal agencies, or provided reconnaissance data to Chinese intelligence services. The company's withdrawal doesn't mean these things happened. It means we got lucky and caught the risk before it became a breach.

But luck isn't a security strategy.

The deeper lesson is that global supply chains and national security exist in tension. Manufacturing is distributed across countries. Components come from everywhere. Financing comes from international sources. Companies operating at the intersection of global commerce and national security face inherent conflicts of interest, whether intentional or not.

Solving this requires accepting some hard truths. First, we can't certify security in a fully globalized supply chain. We can verify that devices meet certain standards, but we can't guarantee that state actors haven't compromised the testing or manufacturing process. Second, centralized certification creates a single point of failure. If the certifying entity is compromised, so is everything it certifies. Third, security costs money. Building trustworthy certification infrastructure, maintaining supply chain oversight, and operating resilient testing facilities all require sustained investment.

Moving forward, the Cyber Trust Mark program has a chance to get this right. The FCC's assumption of direct oversight eliminates the obvious vulnerability that UL Solutions represented. But ongoing success requires consistent investment, technical expertise, evolution with emerging threats, and political will to maintain funding through budget cycles and changing administrations.

For manufacturers, the takeaway is clear: build security into devices from the beginning, know your supply chain, and prepare to document both. For procurement officers, the Cyber Trust Mark is a useful signal but not a complete solution. Continue performing due diligence, managing device lifecycle, and staying aware of supply chain risks.

For everyone else, understanding that devices we use daily could carry hidden vulnerabilities inserted by state actors should feel unsettling. It should be. That feeling of discomfort is accurate. But it's also the reason why having government oversight of IoT security, despite its imperfections, matters. The alternative is devices certified by nobody, standards set by nobody, and vulnerabilities deployed by whoever moves fastest.

The UL Solutions withdrawal proves that the system has some teeth. When a conflict of interest was discovered, the company was removed. The program didn't continue forward with a compromised administrator.

Now comes the harder part: maintaining that rigor for the next five years and beyond, as the Cyber Trust Mark evolves from a program in development to an actual government certification that millions of devices depend on. If we can do that, the mark means something. If we can't, it becomes another security theater where we feel like we're protecting ourselves but actually aren't.

The clock is running toward January 2027. We'll find out which it becomes.

Key Takeaways

- UL Solutions withdrew as Lead Administrator after investigators found ties to Chinese state-owned entity through a joint venture operating 18 testing facilities in China

- The Cyber Trust Mark program requires all IoT devices sold to U.S. government to be certified by January 4, 2027, covering everything from security cameras to smart TVs

- Compromised testing facilities could theoretically insert backdoors during device certification, creating a supply chain vulnerability affecting thousands of government deployments

- The FCC assumed direct oversight of the program following withdrawal, eliminating the single-point-of-failure vulnerability that a private company with conflicts of interest represented

- Government agencies and manufacturers must balance the need for centralized security standards with the risk of concentrating too much authority in a single entity

Related Articles

- NordVPN Salesforce Breach Claim: What Really Happened [2025]

- Trump's Venezuela Intervention: History, Oil Politics, and Global Fallout [2025]

- Critical Infrastructure Breach: Engineering Firm Hack Exposes US Utilities [2025]

- Offshore Wind Developers Sue Trump: $25B Legal Showdown [2025]

- Data Sovereignty for Business Leaders [2025]

- Post-Quantum Cryptography: Securing TLS for the Quantum Era [2025]

![FCC Cyber Trust Mark Program: UL Solutions Withdrawal & National Security Impact [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fcc-cyber-trust-mark-program-ul-solutions-withdrawal-nationa/image-1-1767820011299.jpg)