Introduction: The Accountability Crisis We're Living Through

We're at a strange moment in technology history. AI systems are making decisions that affect millions of lives—from who gets hired, to who gets approved for loans, to what information shapes your worldview—yet nobody's actually accountable when things go wrong. According to TechRadar, this lack of accountability is a significant issue in the current AI landscape.

This isn't a philosophical debate anymore. It's a practical problem. When a hiring algorithm discriminates against protected classes, who gets sued? The company? The engineers? The model itself? When a chatbot confidently gives medical advice that harms someone, who's legally responsible? When an AI training dataset includes stolen creative work, who compensates the artists? As discussed in JD Supra, these questions are critical as AI systems become more integrated into daily life.

These questions aren't hypothetical. They're happening right now, and our legal and ethical frameworks are struggling to keep up. According to a report by Microsoft, the rapid adoption of AI technologies is outpacing the development of accountability mechanisms.

Jaron Lanier, often called the godfather of virtual reality, has been one of the most consistent voices pushing back on the myth that AI can simply "do its thing" without consequences. He's not anti-technology. He's anti-accountability-vacuum. His argument is straightforward: societies literally cannot function when responsibility is diffused across so many actors that nobody actually bears the consequences of their systems' failures.

The problem runs deeper than most people realize. We've built an entire AI ecosystem where companies profit from the output, engineers claim they didn't design the harmful behavior (it emerged from the data), regulators don't understand the technology well enough to enforce rules, and users have no legal recourse. It's a perfect storm of misaligned incentives. As noted by EconoFact, the economic incentives currently favor rapid deployment over careful accountability.

What makes this crisis unique is that it's not about whether AI is good or bad. That's the wrong frame. It's about whether we can create systems where someone—somewhere—actually has skin in the game when things break.

In this deep dive, we'll explore what accountability really means in the age of AI, why it matters, what's preventing it, and what it might look like if we actually got serious about building it into our AI systems and companies.

TL; DR

- Accountability Gap: Nobody's legally responsible when AI systems cause harm, creating a dangerous void where corporations profit and users suffer consequences. This issue is highlighted in a World Economic Forum report.

- Distributed Responsibility Problem: Companies, engineers, and platforms all claim different stakeholders bear responsibility, effectively diffusing accountability to zero, as discussed in Skadden's insights.

- Regulatory Fragmentation: Different countries and jurisdictions have conflicting AI rules, making consistent enforcement impossible and incentivizing regulatory arbitrage. This is a significant issue according to Route Fifty.

- Corporate Incentive Misalignment: Companies optimize for speed-to-market and profit, not for building in safety, oversight, and accountability mechanisms, as noted in Governor Newsom's report.

- Bottom Line: Without clear accountability frameworks backed by legal teeth, AI will continue enabling harm at scale with minimal consequences for the systems' creators, as highlighted by Britannica.

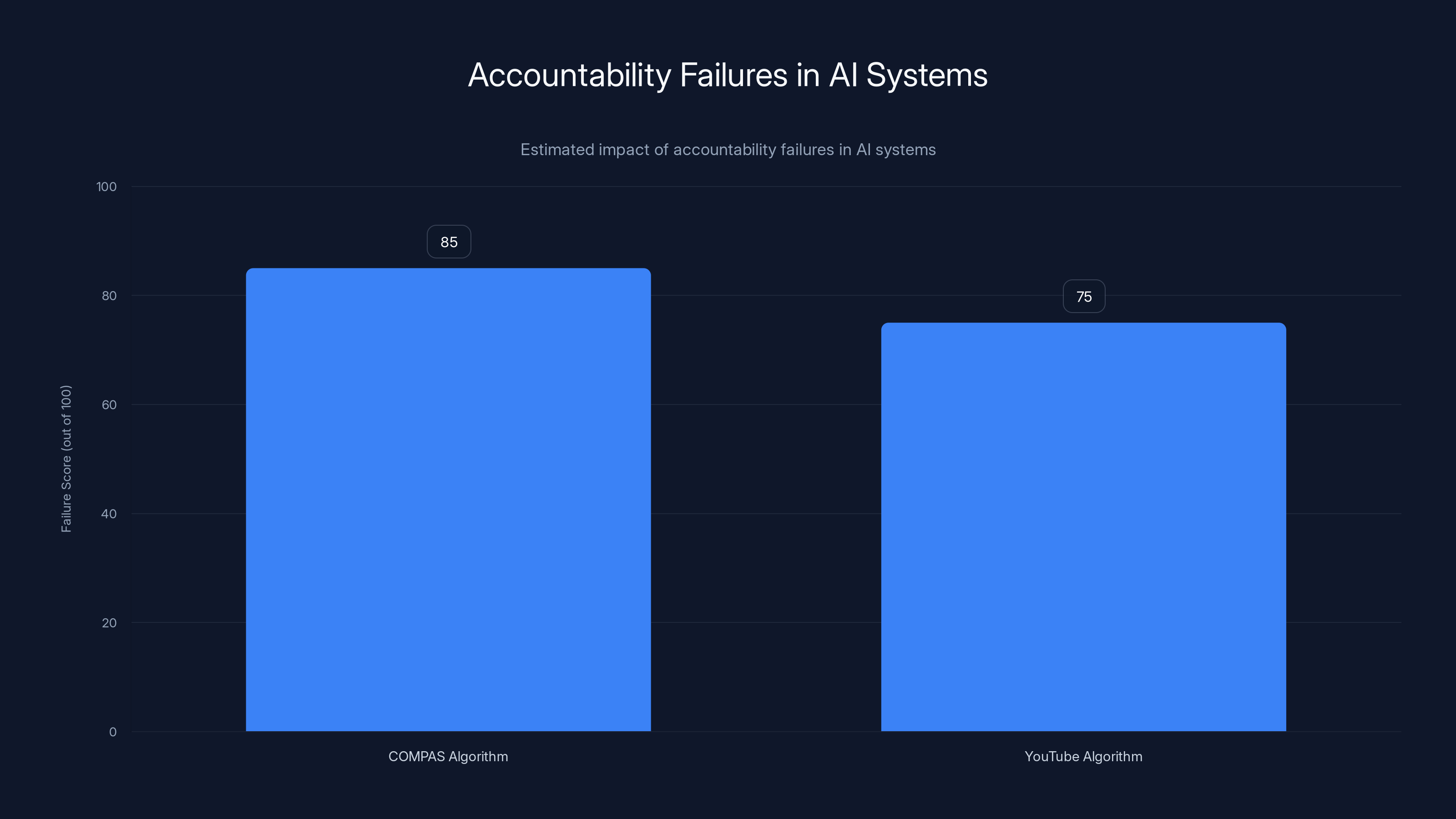

Estimated data shows that both COMPAS and YouTube algorithms have high accountability failure scores due to bias and radicalization issues, respectively. Estimated data.

What Accountability Actually Means (And Why We're Missing It)

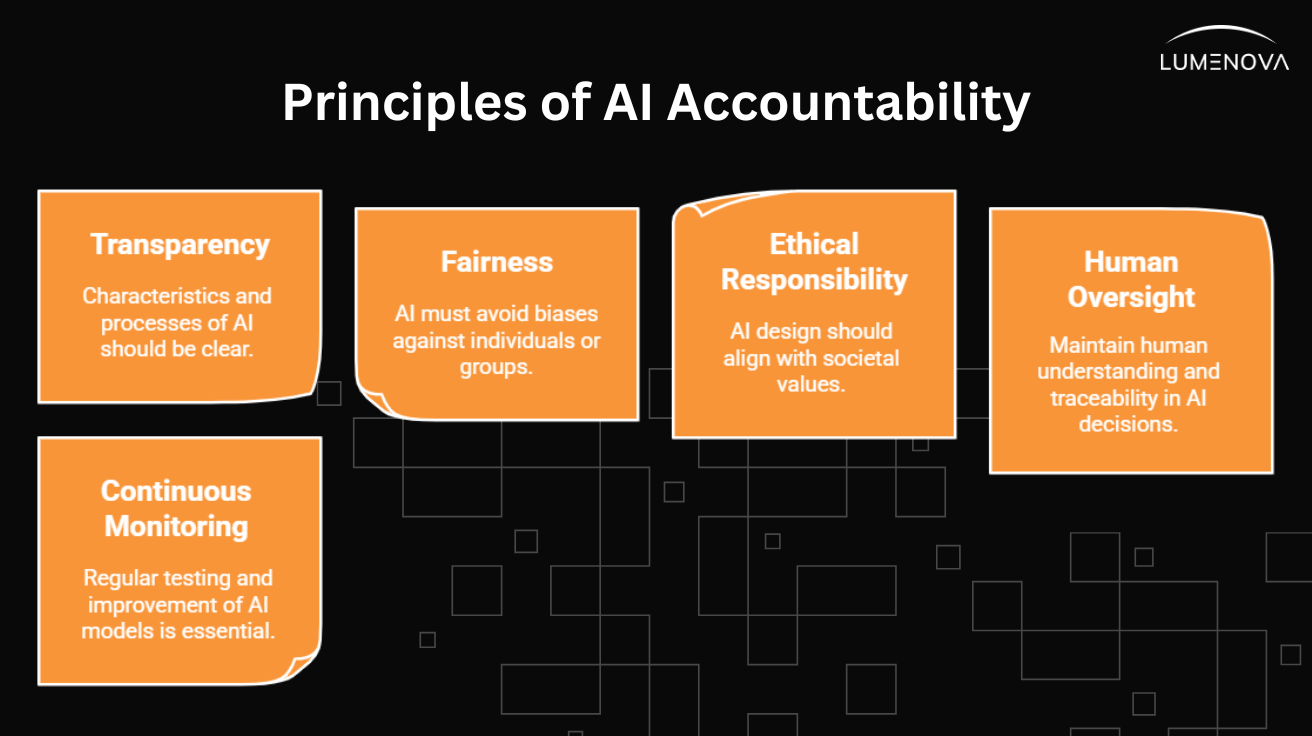

Let's start with something basic: accountability isn't just a buzzword. It's a practical mechanism that makes people and organizations change behavior.

When you're accountable for something, you face real consequences if it goes wrong. A surgeon can lose their license. A car manufacturer can face massive recalls. A pharmaceutical company can get sued into bankruptcy if their drug causes harm. These mechanisms aren't perfect, but they create incentives: do good work, or pay the price. According to CarPro, accountability mechanisms in the automotive industry have led to significant improvements in safety standards.

AI breaks this entire model. Here's why:

First, AI systems are opaque in ways traditional products aren't. A defective car's failure is measurable. A faulty drug's side effect is documentable. But when an AI system discriminates, it's often because of patterns in the training data—patterns nobody explicitly programmed, nobody explicitly approved. The harm emerges. It's not designed in the way a bridge design flaw is designed in.

Second, responsibility gets distributed across too many actors. The company that built the system didn't write all the training data. The engineers didn't personally vet every dataset. The data came from third parties who don't understand how it'll be used. The company that deployed it might have used the system in ways the creators didn't anticipate. By the time harm happens, everyone can point to someone else and say, "That's their responsibility."

Third, there's often no legal framework at all. When Tesla's autopilot kills someone, there's at least a clear legal question: did the car do what it was supposed to do? But when an AI makes a decision, was it a "mistake" or just how the system works? When a recommender algorithm radicalizes someone, is the platform responsible? The AI company? The person who created the content being recommended? As discussed in The New York Times, these questions are at the forefront of current legal debates.

Lanier's core insight is that societies need someone to answer for failures. Not because we need someone to punish, but because without that accountability, nobody improves the systems. There's no negative feedback loop. The incentive is to deploy faster and ignore the damage.

Consider a simple example: a resume screening AI that systematically rejects female candidates because it was trained on historical hiring data from a male-dominated field. The harm is real. Someone didn't get a job. But who's accountable?

The company using the tool? They might claim they didn't know it was biased.

The AI vendor? They might claim the company used it wrong or didn't properly audit their data.

The engineers? They might say the bias was in the training data, not in the code they wrote.

The result: a woman loses a job opportunity, and nobody actually bears responsibility for fixing it. The company might face bad press (if the bias is discovered), but there's no mechanism forcing them to do better next time except reputation damage. And reputation damage only happens if the bias becomes public, which most AI harms don't.

This illustrates the core problem: accountability mechanisms in AI are currently based on reputation damage and regulatory pressure. They shouldn't be. They should be based on clear legal responsibility, the way they are for every other industry.

When a pharmaceutical company's drug causes harm, there's a regulatory approval process that happens before the drug goes to market. There's documentation. There's a chain of responsibility. If someone gets hurt, there's a clear path to find out what went wrong and who made the decisions that led to harm.

We don't have that for AI. We have companies deploying systems at scale with minimal pre-deployment testing, minimal documentation of what the system does and doesn't do, and minimal consequences if things go wrong. That's not innovation. That's negligence at scale.

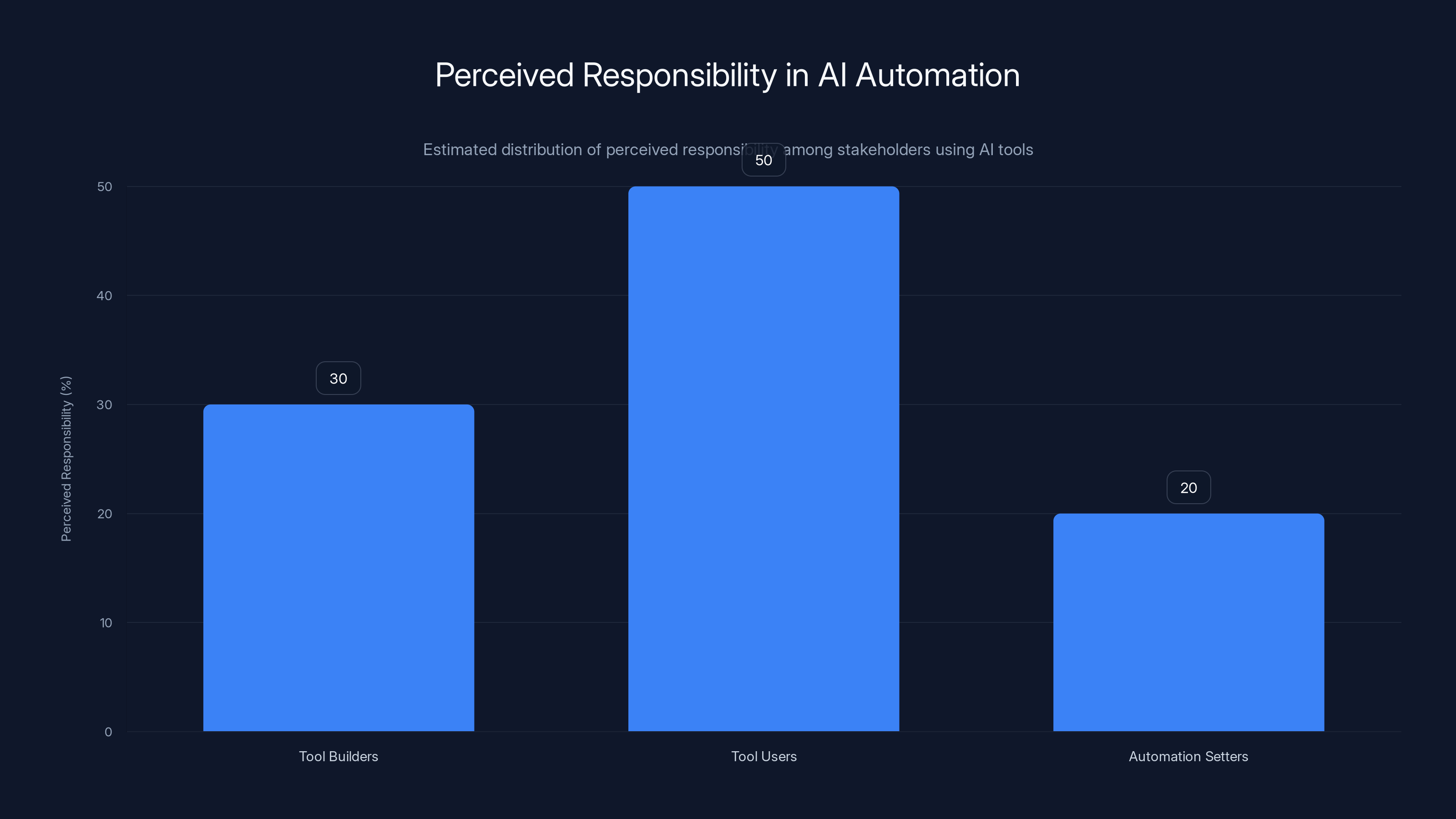

Estimated data shows that tool users are perceived to hold the most responsibility (50%) in AI automation, followed by tool builders (30%) and those setting up the automation (20%).

The Distributed Responsibility Problem: Everyone's Accountable, So Nobody Is

Here's what makes AI accountability uniquely difficult: responsibility gets diffused across so many actors that you end up with what philosophers call the "diffusion of responsibility" problem.

In psychology, diffusion of responsibility is when a group shares responsibility for something, and as a result, each individual's sense of personal responsibility decreases. When there are five people in a room and someone needs help, each person thinks, "Oh, someone else will help." Nobody helps. Responsibility dissolves.

AI systems create this problem at scale.

Consider the journey of a typical AI system:

The Data Stage: The training data comes from somewhere. Public datasets scraped from the internet. Purchased datasets from data brokers. Internal company data. Each data source has different provenance, different licensing, different ethical baggage.

Who's responsible for ensuring the data is accurate, unbiased, and ethically sourced? The data scientists who curated it? The company that owns the data? The original creators of the data? If the data came from the internet, is it the platform's responsibility to have licensed it properly?

The Training Stage: Engineers train a model on that data. They don't explicitly program every behavior. The model learns patterns from the data. If those patterns encode discrimination, injustice, or falsehoods, whose decision was it to include them? The engineers didn't choose to encode bias. They just trained the model on data that happened to be biased.

Who's responsible for catching bias at this stage? The engineers? But they often can't see what patterns the model has learned until they test it. The company? But they might not have the expertise to know what to look for. Regulatory bodies? But they don't have access to the model during training.

The Deployment Stage: The company releases the system. But they often don't fully know what it can and can't do. Large language models are notorious for this. The company trains the model, releases it, and then discovers through user interaction what unexpected behaviors it exhibits.

When unexpected harmful behaviors emerge post-launch, who's responsible? The company for deploying something untested? The engineers for not anticipating the behavior? The users for using it in unintended ways? Open AI, when it first released Chat GPT to the public, didn't fully know what the system could or would do. It became a public research experiment. That's efficient for getting feedback, but it's irresponsible from an accountability standpoint.

The Use Stage: The customer uses the AI system. They might use it exactly as intended, or they might use it in novel ways. If they use it wrong and it causes harm, whose fault is that?

Consider a company using an AI tool for medical recommendations. The tool was trained on available medical data, which has gaps and biases. A doctor uses the tool to recommend treatment for a rare condition. The treatment is appropriate based on the data the AI saw, but the AI didn't see specific contraindications that a human expert would know. The patient gets harmed.

Who's accountable?

The company that built the AI? They might say, "We didn't claim it was infallible."

The doctor? They might say, "I was just following the AI's recommendation."

The patient? They might say, "I trusted my doctor."

The result: harm happens, but the accountability chain breaks. Nobody feels fully responsible because responsibility is spread across the entire system.

This is fundamentally different from traditional industries. When a pharmaceutical company makes a drug, they're responsible for clinical trials, for side effects, for communicating risks. When a car manufacturer makes a car, they're responsible for crash testing, for recalls, for design flaws. The responsibility is clear because it's concentrated.

But AI companies have successfully created a business model where responsibility is diffused. They claim to be neutral platforms. They say they're not responsible for how users use their systems. They say they did their best to remove bias (even if they didn't do very well at it). They say the failures are edge cases.

The problem is that this diffusion is built into the business model. It's not accidental. It's not even necessarily malicious. It's just how AI companies have been structured.

When you're trying to move fast and deploy systems at scale, you don't want to be responsible for everything. You want to say, "This is a tool. We built it. How people use it is their choice. The biases in it come from the training data, which we did our best with. If something goes wrong, it's probably an edge case or user error."

That's a great business model for growth. It's terrible for accountability.

Lanier's argument is that this structure is unsustainable. Eventually, enough harm occurs that societies demand accountability. When they do, the lack of clear responsibility chains becomes a massive problem. You can't improve systems whose failures are nobody's fault. You can't build trust in institutions that won't own their mistakes. And you can't create incentives for safer AI if no one's incentivized to be safer.

Why Current Regulation Falls Short of Real Accountability

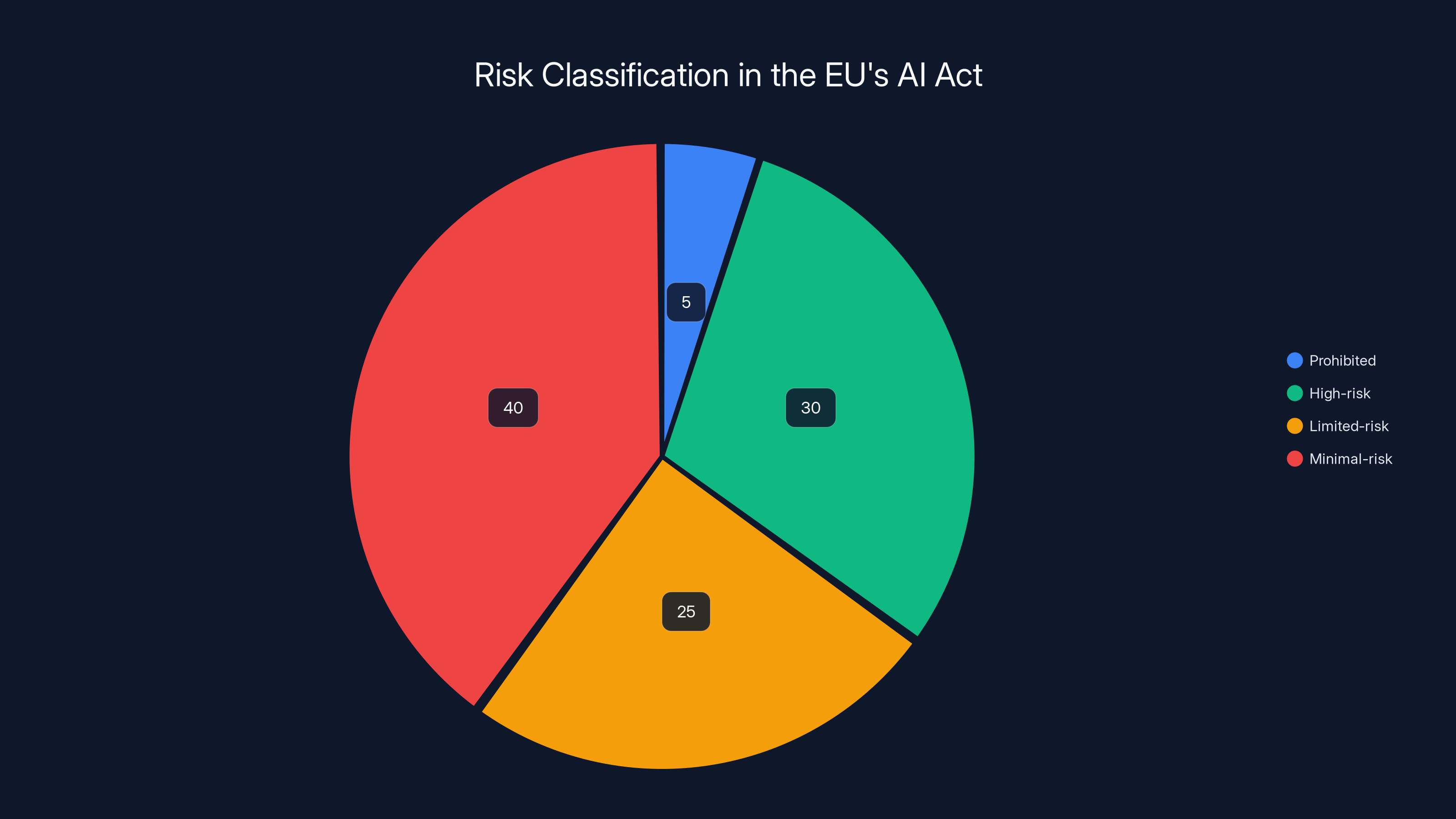

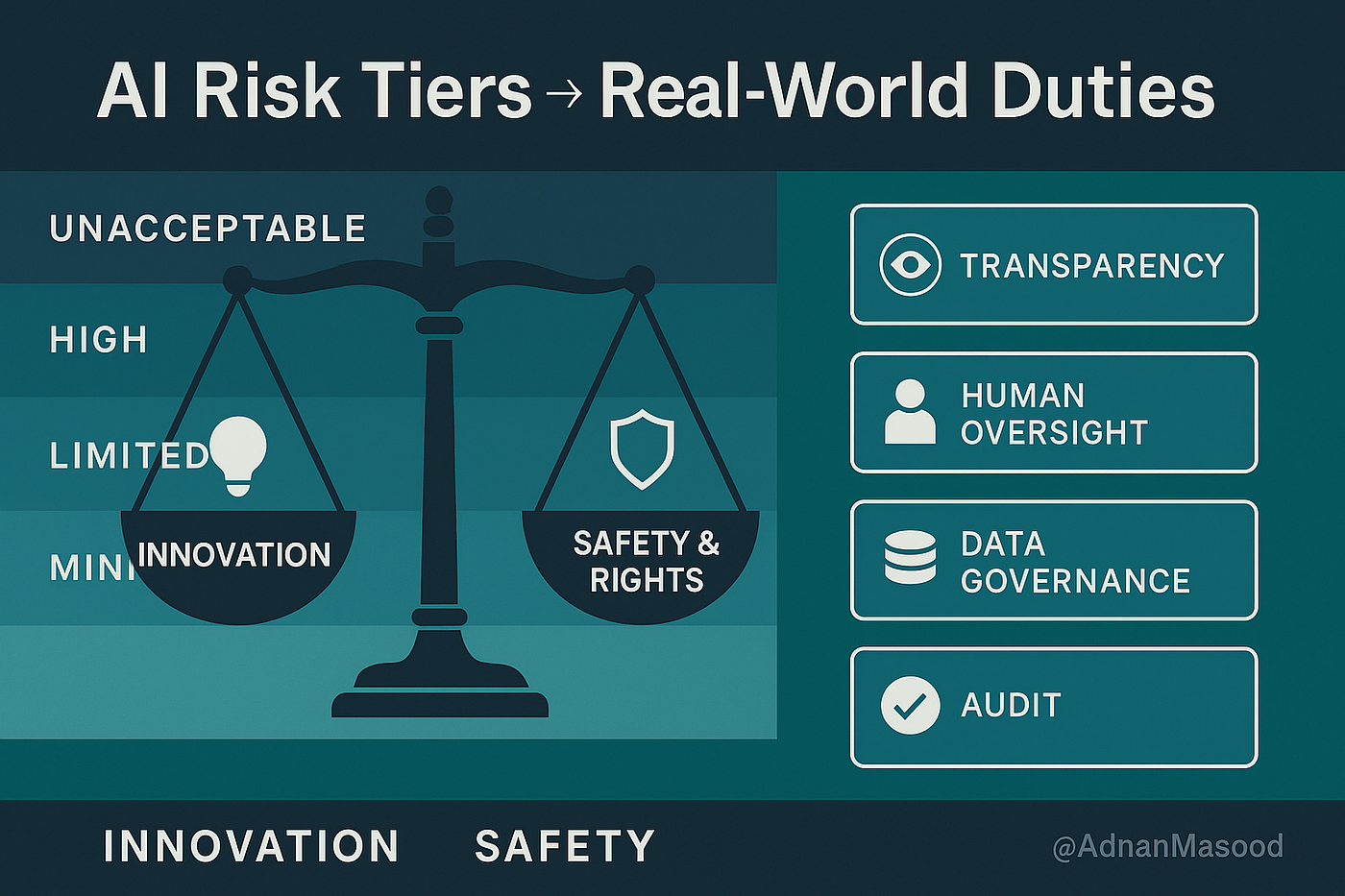

Several countries and regions have taken stabs at AI regulation. The EU's AI Act. China's recommendation algorithm rules. Biden's executive order on AI oversight. These are genuine attempts to create accountability frameworks.

But they have profound structural problems that keep them from actually solving the accountability crisis.

The Speed Problem: AI moves faster than regulation. By the time a regulatory body understands a technology well enough to write rules for it, that technology is already obsolete. Regulatory frameworks written for traditional language models might not apply well to multimodal systems. Rules written for image generation might not work for reasoning systems. As noted in Morgan Lewis, this speed mismatch is a significant challenge for regulators.

This doesn't mean regulators should give up. But it means any regulation that's too specific will fail. The EU's AI Act tries to be future-proof by focusing on "high-risk" AI. But defining what counts as high-risk requires understanding what different AI systems can do, which changes constantly.

The Expertise Problem: Most regulators don't understand AI at a technical level. They can't read a model's documentation and understand what it can or can't do. They can't perform technical audits. So they rely on companies' own safety assessments. But companies have obvious conflicts of interest. The company that built the system has a motive to say it's safe.

This creates a principal-agent problem: the regulator (principal) wants to ensure AI is safe, but they're relying on the companies (agents) that built it to self-report on safety. The agents have an obvious incentive to downplay risks.

The International Arbitrage Problem: AI isn't regulated globally. Different countries have different rules. This creates a powerful incentive: companies build what's legal in the most permissive jurisdiction, then sell it globally.

Want to train an AI system on data that would be illegal to use in Europe? Train it in a country with no data protection laws. Want to deploy a system that would be illegal in one country? Deploy it in a country with no regulations against it.

This isn't just theoretical. It's happening. Companies are currently navigating the patchwork of global AI regulation by building to the lowest common denominator and deploying globally.

The Enforcement Problem: Even when regulations exist, enforcement is weak. Who investigates when a company violates AI regulations? Who has the resources to audit systems at scale? Who can demand transparency about how AI systems work?

The answer is: not many people. Regulatory bodies are underfunded. They don't have the technical expertise to audit AI systems. When they do try to enforce rules, companies can claim confusion about what the rules require.

Look at data protection enforcement. GDPR is one of the most stringent data protection laws on Earth. The EU has invested heavily in enforcement. Yet massive tech companies still routinely collect data in ways that seem to violate GDPR, and enforcement is painfully slow.

Now apply that same slow, resource-constrained enforcement to AI. You get a system where regulations exist but don't actually prevent harm.

The Definition Problem: Most AI regulations try to define what AI is and what rules apply to it. But the definitions keep changing. Is a recommendation algorithm AI? Is a search engine AI? Is a spell-checker AI? At what point does a tool become "AI" and trigger regulatory requirements?

Companies exploit this ambiguity. They deploy systems that clearly use machine learning but claim they're "just software." They claim their systems aren't "artificial intelligence" in the regulatory sense. They find loopholes in how the rules are written.

Regulation based on definitions fails because the technology doesn't respect definitions.

The Liability Problem: Even when regulations exist, the question of who's liable when something goes wrong remains murky. In traditional product liability, you can sue the manufacturer. But with AI, the question of what the manufacturer is responsible for is unclear.

If an AI system gives bad medical advice, is the company that built the AI liable? Is the platform that deployed it liable? Is the doctor who used it liable? Or is the user who followed the advice liable for their own harm?

Different jurisdictions answer this differently. Some courts have started to hold AI companies responsible for outcomes. Others haven't. This patchwork of liability means that companies can shift their operations to jurisdictions with weaker liability standards.

What emerges from all this is a regulatory system that looks strict on paper but has massive gaps in practice. Companies can navigate around it. Users have minimal legal recourse. And the fundamental accountability problem—that nobody's actually responsible when things go wrong—remains unsolved.

This isn't to say regulation is pointless. The EU's AI Act does create some real constraints on what companies can do. But it's to say that regulation alone isn't creating meaningful accountability. Companies are still deploying systems at scale with unclear responsibility for outcomes.

Transparency and legal liability are estimated to be the most crucial factors for developing accountable AI, with scores of 9 and 8 respectively. Estimated data.

The Corporate Incentive Problem: Profit Over Accountability

Here's the uncomfortable truth about why accountability doesn't exist in AI: it's not in companies' financial interest to create it.

Think about what accountability requires:

-

Transparency: You have to clearly document what your system does, doesn't do, and is uncertain about. You have to be honest about limitations.

-

Testing: You have to thoroughly test your system before releasing it. You have to document what tests you ran, what they revealed, and why you decided to release it anyway.

-

Responsibility: You have to accept that if your system causes harm, you're responsible for fixing it and compensating those harmed.

-

Slow Deployment: You can't move as fast because you have to be careful. You have to think about potential harms. You have to set up processes to catch problems before they affect millions of people.

Now think about what speed and profit require:

-

Opacity: You move faster if you don't have to explain everything. You deploy faster if you don't have to document limitations.

-

Minimal Testing: You get to market faster if you skip the expensive testing phase. Let users find the problems.

-

Distributed Responsibility: You reduce your legal liability if responsibility is unclear. You want to claim you're a neutral platform, not the party responsible for outcomes.

-

Fast Deployment: You want to move quickly because first-mover advantage is huge. You want to capture market share before competitors do.

These two sets of requirements are in direct conflict.

A company that takes accountability seriously might release a language model in 18 months after extensive testing, documentation, and safety evaluation. A company optimizing for speed might release it in 8 months with minimal testing, maximal hype, and a claim that "the community will help find problems."

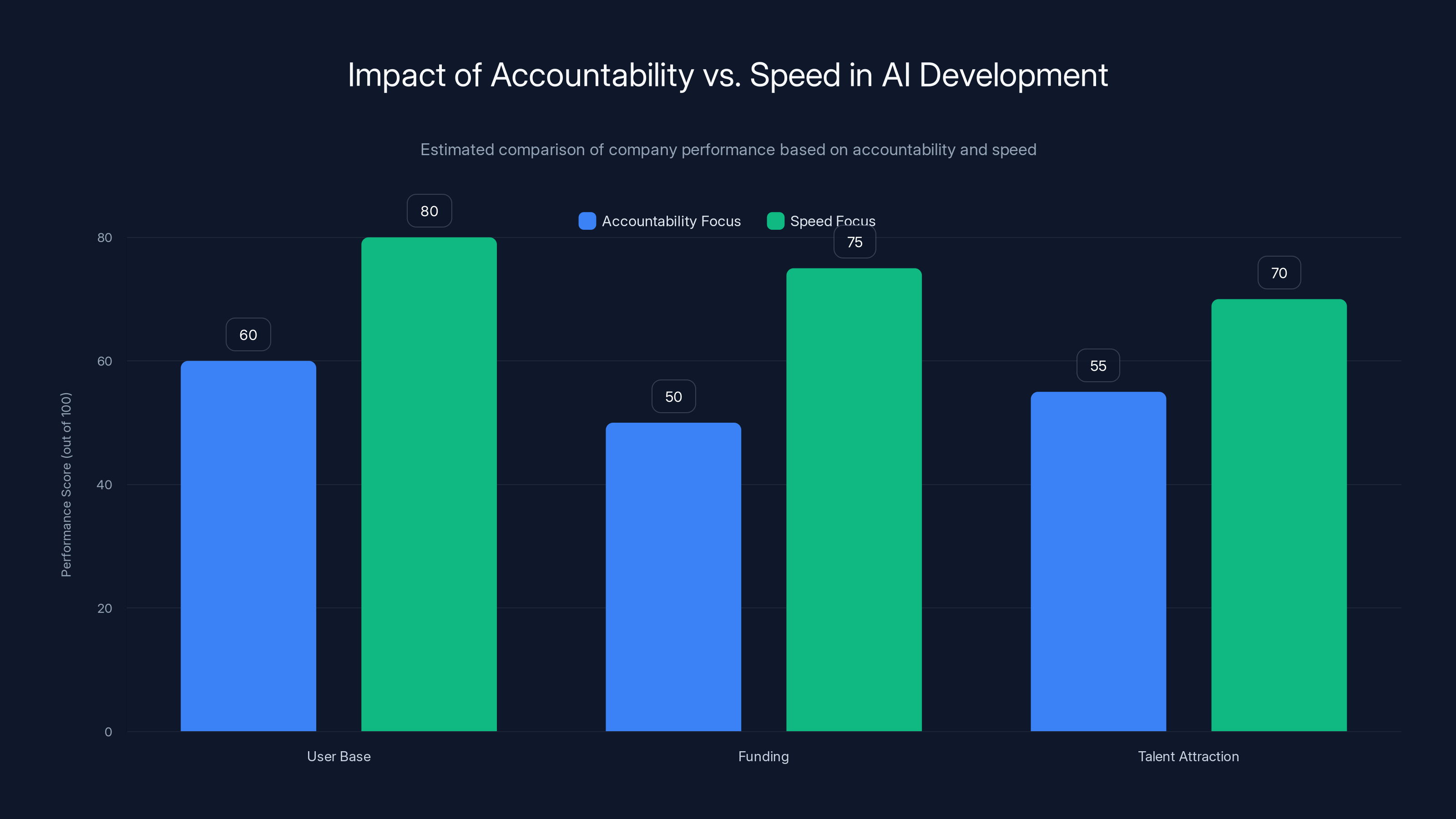

Which company gets more users? Which gets more funding? Which attracts the best talent? It's not even close. The fast, transparent-about-limitations company loses to the fast, opaque company that hypes up benefits and downplays risks.

This is a classic market failure. Individual companies are incentivized to move fast and be opaque. But society is harmed when all companies do this. Yet the individual company that unilaterally decides to move slowly and be transparent gets punished by the market.

So what do companies do? They optimize for speed and profit. They create business models where responsibility is diffused. They lobby against regulations. They make acquisition choices that consolidate power in ways that make external accountability harder.

This isn't unique to AI, by the way. Tobacco companies did the same thing. Oil companies did the same thing. Financial companies did the same thing before the 2008 crisis. Industry finds ways to resist accountability because accountability is expensive.

But Lanier's argument goes deeper. He's saying that the absence of accountability isn't just bad for society. It's bad for the companies themselves and for the technology.

When nobody's accountable, nobody improves the system. There's no feedback loop. Users suffer problems, but the company doesn't face consequences, so why would they fix it? Bias persists because there's no mechanism forcing the company to root it out. Failures repeat because there's no legal reason not to repeat them.

Contrast this with industries where accountability is clear. Aviation has an extraordinary safety record because there's clear accountability. When a plane crashes, there's a federal investigation. The manufacturer, the airline, the airport—someone's responsible. So everyone involved works obsessively on safety.

AI doesn't have that. There's no federal AI crash investigation board. There's no clear responsibility when AI causes harm. So the incentive to obsess over safety doesn't exist.

What would it look like if companies actually took accountability seriously?

First, they'd be transparent about what their systems can and can't do. They'd publish clear documentation. They'd disclose known biases. They'd be honest about edge cases and failure modes.

Second, they'd have regulatory approval before deploying high-risk systems. They'd undergo the equivalent of clinical trials for AI, where independent bodies verify the system is safe before release.

Third, they'd accept liability for harms caused by their systems. If someone is harmed by AI that your company built, you're responsible for fixing it and compensating them.

Fourth, they'd move slowly. They'd release fewer systems more carefully rather than hundreds of systems as fast as possible.

Fifth, they'd limit their systems' ability to cause harm. If a system is designed for job recommendations, it shouldn't be able to do medical diagnosis. If it's designed for English, it shouldn't be deployed on languages it wasn't tested on.

Would any company do this voluntarily? Almost none. Would customers even want this? Maybe not, if it meant paying more or waiting longer. But from a societal perspective, this is what accountability looks like.

The question is: how do we create incentives for companies to be accountable when individual companies moving fast and being opaque beat companies that move slowly and are transparent?

That's the core problem Lanier is highlighting. And it's not solved by writing stricter regulations. It's solved by fundamentally rethinking how AI companies should be structured, measured, and incentivized.

The Empathy Gap: Where Does Responsibility End?

One of the more unusual arguments Lanier makes is about empathy. He asks: how far does our responsibility extend?

Normally, when we talk about accountability for AI, we talk about harm to humans. A biased hiring algorithm harms a person who doesn't get a job. A recommender system that radicalizes people causes societal harm. A medical AI that gives wrong diagnoses harms patients.

But Lanier pushes the question further. He asks: what about people whose labor was used to build the AI without their consent? What about artists whose work was used to train image generators without compensation? What about people whose words were scraped into training datasets without permission?

The current model is: if you post something on the internet, it's fair game for AI training. Millions of artists' work has been used to train image generators. Millions of authors' words have been used to train language models. They weren't asked. They don't get paid. They have no say in how their work is used.

Who's accountable for that? The AI companies claim the training data was public. The users claim they didn't know their data was being used. The platforms claim they have the right to host the data. Responsibility dissolves.

But there's a real harm here. Artists are losing income as image generators get better. Writers are losing income as language models replace writing work. The economic value that was created from their work is captured by the AI companies, not shared with the creators.

Lanier argues that this is a failure of accountability. The AI companies didn't ask for permission. They didn't compensate the creators. They claimed their use was legal and left it at that. But legal doesn't mean ethical. And if we want accountability, we need to account for everyone harmed by the system, including people whose labor created the system.

This is a harder problem to solve than traditional AI bias. It's not about fixing an algorithm. It's about rethinking who should be compensated for building AI systems and how that compensation should work.

Lanier's argument about empathy is subtle. He's not saying we need to feel sorry for AI systems. He's saying we need to extend accountability to everyone involved in building them. That includes:

- Data creators: The people whose content is in the training data

- Data annotators: The people who labeled data so the AI could learn

- Users: The people affected by AI decisions

- Affected communities: The groups systematically harmed by AI bias

Current accountability frameworks don't account for most of these people. The AI company takes the legal risk, but everyone else bears the consequences without recourse.

What would empathy-based accountability look like?

First, transparency about whose data and labor went into the system. You built an AI? Disclose where the training data came from. Who created it? Was it used with permission?

Second, compensation for creators whose work is in the training data. If your image generator uses millions of artists' work, those artists should get a cut of the revenue.

Third, opt-out mechanisms for people who don't want their data used. If you post something on the internet, the default shouldn't be that it's available for AI training. You should be able to opt out.

Fourth, benefits sharing with communities that are harmed by or contribute to AI systems. If a system is trained on medical data from a hospital in a poor country, that hospital and that community should benefit from the system's success.

These requirements would slow down AI development. They'd make it more expensive. But from an accountability perspective, they're the minimum you'd expect. You'd expect it for any other industry. You'd expect companies to get permission before using people's work. You'd expect compensation.

That AI doesn't operate this way is a sign of just how far the accountability gap extends. It's not just about the end users affected by AI. It's about everyone in the entire chain of creating AI systems.

Companies focusing on speed tend to gain a larger user base, more funding, and attract more talent compared to those prioritizing accountability. (Estimated data)

Concrete Examples of Accountability Failures

Let's ground this in specific cases where the accountability gap caused real harm.

Case 1: The COMPAS Recidivism Algorithm

Companies use AI for predicting recidivism in criminal justice. COMPAS is one of the most famous examples. It's used by courts to help decide bail amounts, sentencing, and parole eligibility.

In 2016, Pro Publica investigated COMPAS and found that it was significantly more likely to mark Black defendants as high-risk than white defendants, even when they had identical criminal histories.

Who's accountable for this?

The company that built COMPAS claimed the bias came from historical data—the data included historical racism in the criminal justice system. They claim they didn't encode bias; bias was in the data.

The courts using COMPAS claim they're just using a tool to inform decisions. They still have final say.

The criminal justice system as a whole claimed this was a technical issue, not a policy issue.

The result: years of defendants being marked as higher risk than they should have been. Some got longer sentences. Some were denied parole because the system flagged them as high-risk. And nobody faced meaningful consequences.

Eventually, Pro Publica's investigation generated enough pressure that some jurisdictions stopped using COMPAS. But that's because of reputation damage, not accountability mechanisms.

A truly accountable system would have:

- Required the company to identify the bias before deployment

- Required the courts to use the system only if bias was within acceptable limits

- Created a legal mechanism for defendants harmed by the bias to get relief

- Held the company liable for harms caused by their bias

None of that happened.

Case 2: YouTube's Recommendation Algorithm and Radicalization

YouTube's recommendation algorithm is designed to maximize watch time. A massive amount of research shows that this incentive structure causes the algorithm to recommend increasingly extreme content. People watching moderate content get recommended extreme content. Moderate content creators lose viewers to extreme content creators.

Multiple researchers have documented this. Multiple journalists have traced radicalization paths facilitated by YouTube recommendations. The algorithm didn't intentionally radicalize people—but the optimization target (maximize watch time) had that effect.

Who's accountable?

Google/YouTube claims they're not responsible for what content creators put up. They're a platform, not a publisher. Content moderation is hard. They do their best.

The content creators who benefit from the algorithm's radicalization properties claim they're just posting content people want to watch.

Users claim they're just clicking what interests them.

The result: a documented mechanism that radicalizes people at scale, and no accountability for it.

A truly accountable system would have:

- Measured the impact of the algorithm on radicalization before deployment

- Adjusted the optimization target if it was causing radicalization

- Monitored the algorithm's effects after deployment

- Created a legal mechanism for people harmed by radicalization to get relief

- Held the company liable for documented harms from the algorithm

Google started to do some of this after pressure, but only after massive documented harm. And they made changes reluctantly, because they were pressured, not because accountability mechanisms required it.

Case 3: LinkedIn's Facial Recognition and Bias

LinkedIn's photo verification system used facial recognition to verify that profile photos actually matched the person creating an account. But the system had bias: it worked better for people with lighter skin tones than darker skin tones.

People with darker skin tones had higher failure rates. Some couldn't verify their accounts. The system rejected legitimate photos from some people while accepting photos from others.

Who's accountable?

LinkedIn claimed they were trying to prevent fraud and impersonation. They tested the system. But their testing didn't catch the racial bias.

The facial recognition vendors claimed the bias was in their training data and model.

Users claimed they had no way to know the system was biased.

The result: people with darker skin tones had worse experiences on the platform, and nobody paid a legal price for it.

LinkedIn eventually fixed the system (or at least claimed to), but again, this happened because of reputational pressure, not accountability.

Pattern Across Cases

Look at the pattern in these cases:

- Harm is real and documented: People are systematically harmed

- No direct intent to harm: The companies didn't explicitly choose to harm these groups

- Responsibility diffuses: Company, engineers, data, users, everyone points to someone else

- Accountability is reputation-based: The company only fixes it after public pressure

- No legal consequences: Nobody pays a price except in reputation and market share

Imagine if pharmaceutical companies operated this way. A drug causes harm. The company claims the harm came from unexpected side effects in user populations. No mechanism to hold them accountable. They only fix it if public outcry gets loud enough.

But that's not how pharmaceuticals work. There's pre-approval testing. There's regulatory oversight. There's post-market surveillance. There are legal consequences for harm. If a company withholds safety data, they get sued. If a drug causes harm that the company should have caught, they're liable.

AI doesn't have any of this structure.

The Path Forward: What Meaningful Accountability Looks Like

So what would it look like if we actually solved the accountability problem?

Lanier's argument (and the argument of others pushing for AI accountability) is that we need systemic change, not just tweaks to existing frameworks.

First, we need legal accountability with teeth. Companies that deploy AI systems should be liable for harms caused by those systems. This should work the way it does for pharmaceuticals or cars: you deployed the system, you're responsible for injuries it causes.

This doesn't mean the company is liable for absolutely everything a user does with the AI. But if the system causes systematic harm—bias, discrimination, radicalization—the company should be accountable.

The threshold for liability should be high enough that companies aren't liable for rare user misuse. But it should be low enough that companies can't get away with deploying biased or harmful systems.

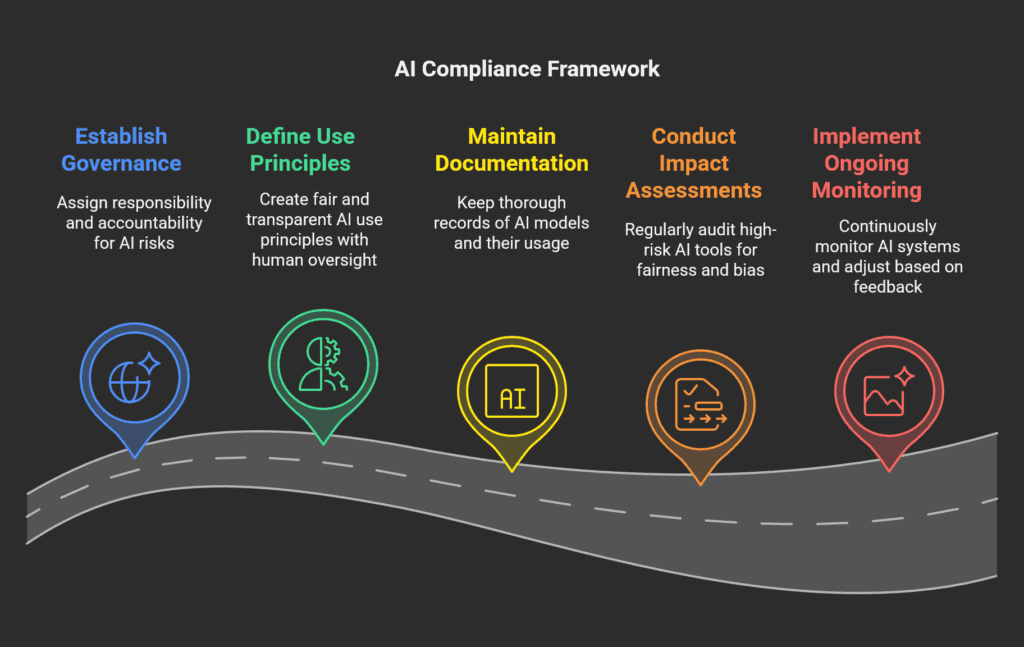

Second, we need pre-deployment review and approval for high-risk systems. Some AI systems are just too consequential to deploy without oversight. Hiring AI. Medical AI. Criminal justice AI. Loan approval AI. These systems should undergo regulatory approval before deployment, the way drugs do.

This means:

- Independent testing of the system

- Documentation of limitations

- Testing for bias across demographic groups

- Simulation of potential harms

- Approval only if risks are acceptable

Not every AI system needs this level of scrutiny. A personal photo-editing AI doesn't need FDA-like approval. But systems that make decisions affecting people's lives do.

Third, we need transparency requirements. Companies should have to publicly disclose:

- Where training data came from

- What tests were run

- What biases were found and not fixed

- Who had final decision-making authority

- What appeals mechanisms exist for people harmed

This might slow down AI development, but it makes companies accountable for what they deploy.

Fourth, we need compensation mechanisms for harm. If someone is demonstrably harmed by an AI system—denied a job interview, denied a loan, wrongly flagged by content moderation—there should be a clear path to compensation.

This doesn't require anyone to sue. There should be an administrative process. The person files a complaint. The company has to respond. If the complaint is valid, they compensate.

Fifth, we need creators' rights. People whose data or work is used to train AI should have rights:

- The right to know if their data is being used

- The right to opt out of their data being used

- The right to compensation if their work is used commercially

This is particularly important for artists whose work has already been used to train image generators without consent.

Sixth, we need algorithmic transparency requirements. For consequential AI systems, companies should have to make the system's decision-making process transparent.

This doesn't mean releasing the full model weights. It means explaining to the user why the AI made a particular decision. If a hiring AI rejected your resume, you should be able to ask why and get a meaningful answer.

Seventh, we need international coordination. AI regulation won't work if companies just move their operations to permissive jurisdictions. There needs to be enough international agreement on minimum standards that regulatory arbitrage becomes harder.

This is hard. Different countries have different values and different levels of tolerance for AI risk. But without some baseline international standards, the accountability mechanisms in one jurisdiction get undermined by permissive operations in another.

Eighth, we need independent oversight bodies. Right now, companies are largely self-regulating. They decide what's safe. They do their own testing. They judge their own outcomes.

That's a conflict of interest. We need independent bodies—maybe government agencies, maybe non-profit auditors, maybe industry watchdogs—that can audit AI systems and hold companies accountable.

None of these changes are magic bullets. All of them have costs. Pre-deployment review slows innovation. Transparency requirements might reveal trade secrets. Compensation mechanisms increase legal liability.

But all these costs exist because accountability has value. It prevents harm. It creates incentives for companies to build safer systems. It builds trust that AI systems are being treated seriously.

Without these mechanisms, AI will continue being deployed at scale with minimal oversight and minimal consequences for harm. And societies genuinely cannot function under those conditions. As Lanier argues, eventually the harm becomes visible enough that people demand change. But by then, the damage is done.

The EU's AI Act categorizes AI systems into four risk levels, with 'Minimal-risk' systems making up the largest portion. 'High-risk' systems require significant oversight. Estimated data.

Regulatory Frameworks Being Tested Right Now

Several jurisdictions are experimenting with different accountability frameworks. Understanding what they're trying to do—and where they fall short—helps illustrate what meaningful accountability might look like.

The EU's AI Act

The EU has taken the most comprehensive regulatory approach with the AI Act, which took effect in 2024. The Act classifies AI systems by risk level:

Prohibited: AI systems that are considered too risky (emotion recognition in educational settings, social scoring, etc.)

High-risk: Hiring AI, criminal justice AI, educational AI, etc. These require:

- Documentation of what the system does

- Testing for bias

- Human oversight mechanisms

- Transparency to users

Limited-risk: Systems that might mislead people (deepfakes, chatbots) must disclose they're AI

Minimal-risk: Everything else

On paper, this looks comprehensive. But it has gaps:

First, enforcement is weak. The EU doesn't have enough people to audit all the AI systems subject to the Act. Companies can claim compliance without rigorous external verification.

Second, definitions are ambiguous. What counts as "high-risk"? What counts as "bias"? Companies are already exploiting the ambiguity.

Third, the Act applies only in the EU. Companies outside the EU can build systems however they want and sell them to EU users. The Act has extraterritorial reach, but it's weak.

Fourth, the liability mechanisms are unclear. If someone is harmed by AI covered by the Act, can they sue the company? On what grounds? The Act doesn't clearly establish liability.

So the EU's AI Act is a step forward. It creates some accountability mechanisms. But it doesn't fully solve the problem.

China's Approach

China has taken a different approach, focusing on algorithmic recommendation transparency and content safety. The requirement is that algorithms used for recommendations (news feeds, video recommendations, etc.) must disclose how they work and allow users to opt out of personalization.

This is narrower than the EU's AI Act. It only covers recommendation algorithms. But it's more specific and arguably more enforceable.

However, it has limitations:

First, it doesn't cover other high-risk uses like hiring or credit decisions.

Second, enforcement is through government agencies that are also using AI for surveillance and control, which raises questions about whether the framework is actually designed to protect users or to ensure government control over AI.

Third, it doesn't address creators' rights or compensation for data used in training.

The US Approach

The US has been slower to regulate AI. Biden's executive order in 2023 focused on specific high-risk areas (critical infrastructure, cybersecurity, etc.) but didn't create comprehensive AI regulation.

Some US states are experimenting with their own rules. California has been pushing for algorithmic transparency. New York required audits of hiring AI.

But there's no comprehensive US AI regulation yet. This means:

First, companies can navigate the patchwork of state regulations by operating to California's standard and claiming compliance everywhere.

Second, the liability framework is unclear. If an AI system causes harm, is the company liable? Under what legal theory? Courts are still figuring this out.

Third, there's no pre-deployment approval process for high-risk AI. Companies can deploy whatever they want and face consequences only if harm becomes visible.

Common Gaps Across Frameworks

Look at what all these frameworks have in common:

- Weak enforcement: Regulators don't have resources to audit all systems

- Ambiguous definitions: What counts as AI? What counts as high-risk? Companies exploit ambiguity

- Limited pre-deployment review: Most systems aren't reviewed before deployment

- Unclear liability: When harm occurs, it's not always clear who's legally responsible

- No compensation mechanisms: Even when systems are found to be biased or harmful, there's no automatic compensation

- International gaps: Companies can shift operations to permissive jurisdictions

What's emerging is a regulatory landscape that looks strict but has massive loopholes. It creates some friction for companies, but it doesn't fundamentally change the accountability problem.

Meaningful accountability would require solving all these gaps simultaneously. That's hard, but it's what's needed.

How Automation Tools Are Shifting Responsibility

One interesting way the accountability gap emerges is through automation. As companies build AI systems to do more, the question of who's accountable gets even more diffuse.

Consider how tools like Runable are being used. Runable is an AI-powered platform that automates content creation, document generation, presentations, and reports.

Now imagine a company using Runable to generate customer service responses. Or to create marketing copy. Or to draft legal documents.

If those AI-generated outputs cause harm, who's accountable?

- The company using Runable? They're responsible for what they publish.

- Runable? They built the tool, but they didn't make the specific decision to use it for legal documents.

- The human who set up the automation? They didn't write the actual outputs.

Responsibility becomes unclear. And if responsibility is unclear, accountability mechanisms fail.

This pattern repeats across automation tools. Zapier, Make, and other workflow automation platforms are making it easier for non-technical people to build complex automations using AI.

It's great for productivity. But it creates new accountability gaps. The person building the automation might not fully understand what the AI will do. The AI vendors claim they're just providing tools. The companies using the tools claim they didn't know there'd be problems.

Meaningful accountability would require:

- Tool builders (like Runable) to clearly disclose what their systems can and can't do

- Tool builders to provide safeguards for high-risk uses

- Tool users to verify that automated outputs are correct before deploying them

- Clear liability for tool users (they're responsible for what they publish)

- Clear liability for tool builders (they need to prevent known harms)

This is harder than it sounds, because tool builders can't anticipate all the ways their tools will be used.

Lanier's argument here is that automation shouldn't obscure accountability. It should make it clearer. If an automated system causes harm, you should know exactly who's responsible and they should face real consequences.

Right now, automation often diffuses responsibility: everyone involved in the chain claims they're not fully responsible because someone else is in the chain.

AI accountability issues are significant, with lack of legal frameworks scoring the highest impact. Estimated data.

The Future: Can We Actually Build Accountable AI?

Where does this go? Is there a realistic path to accountability, or is this just how AI will work—high impact, diffused responsibility, minimal consequences for harm?

Lanier's optimistic argument is that eventually, societies will demand accountability and build it in. The pessimistic argument is that by the time they do, the harm will be enormous and the power of AI companies will be so concentrated that building in accountability becomes nearly impossible.

Let's consider both scenarios.

The Optimistic Path

In the optimistic scenario, we eventually get serious about AI accountability. Here's what that looks like:

First, societies establish clear legal liability for AI systems. Companies that deploy AI are responsible for harms, the way pharmaceutical companies are responsible for drugs.

Second, high-risk AI requires pre-deployment approval. Governments establish approval processes similar to drug approval. Companies must prove their system is safe before deploying at scale.

Third, transparency becomes standard. AI companies disclose what their systems can do, what biases were found, where the training data came from. Transparency is expected, not resisted.

Fourth, creators get compensation for their work. Artists and writers used in AI training are compensated. Data is licensed properly.

Fifth, oversight agencies develop the expertise to audit AI systems. We build regulatory infrastructure specifically for AI.

Sixth, international standards develop. Most countries require minimum standards for AI, reducing the temptation to move operations to permissive jurisdictions.

In this scenario, AI development slows down. Companies invest more in safety and less in raw capability. But AI gets deployed more responsibly. The systems that exist cause less systematic harm. Trust in AI increases because companies are actually accountable.

Is this realistic? Maybe. We've done it before. Aviation started fast and loose. Then crashes happened. Now aviation is heavily regulated, pre-deployment approval is required, and it's the safest form of transportation.

We could do the same for AI. It would require political will. It would require regulators developing expertise. It would require companies accepting more oversight. But it's possible.

The Pessimistic Path

In the pessimistic scenario, accountability never really develops. Here's why:

First, AI companies are now some of the most powerful companies on Earth. They have enormous resources to lobby against regulation. They can afford to fight any regulatory framework.

Second, AI is moving too fast for regulators to keep up. By the time regulations are written, the technology is obsolete.

Third, there are genuine international conflicts about how AI should be regulated. China's approach is very different from Europe's. The US has no comprehensive approach. Without international agreement, individual regulations fail.

Fourth, people like the productivity benefits of AI. They like AI chatbots and AI image generators. They're willing to accept some risk to get those benefits. So there's not enough popular pressure for strict regulation.

Fifth, the people harmed by AI are often dispersed and unorganized. A hiring algorithm harms thousands of individuals, but they don't organize as a political force. A recommender algorithm radicalizes millions, but they don't sue as a bloc. Diffuse harms are hard to organize against.

In this scenario, AI keeps getting deployed with minimal oversight. Harms accumulate. But because the benefits are visible and the harms are diffuse, nothing changes. We live in a world where powerful AI systems are making important decisions, nobody's clearly accountable, and when things go wrong, the solution is just another AI system to fix the problems the first one created.

The Middle Path

Most likely, we get something in between. Some accountability mechanisms develop. Not all of them. Some AI companies self-regulate responsibly. Others resist any oversight.

The EU's AI Act is an example. It's real regulation, but it has gaps. It's a step toward accountability, but not a complete solution.

We probably see a gradual tightening of rules. As harms become visible, regulations strengthen. But the process is slow and uneven.

Some jurisdictions develop strong accountability frameworks. Others don't. This creates a two-tier world where responsible AI exists in regulated jurisdictions and less responsible AI exists elsewhere.

Companies navigate between these jurisdictions. They build different versions of their systems for different markets. They lobby against regulations everywhere.

Overall, the accountability problem improves but doesn't get fully solved.

Which path do we take? It depends on decisions being made right now. Do we build accountability into AI as it's being developed? Or do we wait until the harm is visible, then try to retrofit accountability?

History suggests we do the latter. We usually wait until harm is visible. But in the case of AI, waiting might be more costly than usual, because AI systems at scale can cause harm to millions of people quickly.

What This Means for Everyone

If you're using AI, what does the accountability gap mean for you?

First, understand that when you use an AI system, you're often assuming the liability. If an AI tool gives you bad advice and you act on it, you're responsible for the consequences, not the tool's maker.

This is changing as regulations develop, but it's still mostly true.

Second, expect that AI systems will be biased in ways you don't expect. Not because the companies are malicious, but because accountability for bias is weak. Companies don't have strong incentives to find and fix bias.

Third, advocate for accountability. Demand that companies disclose what their systems do. Ask for transparency about where training data came from. Support regulations that create accountability.

Fourth, be cautious about consequential AI. Don't trust an AI system to make high-stakes decisions without human review. Hiring decisions, medical decisions, financial decisions—these should use AI as input, not as the decision-maker.

Fifth, if an AI system harms you, document it. Get others to document similar harm. Make it visible. The one leverage you have is attention. When harm becomes visible enough, companies are forced to respond.

Sixth, if you're building or deploying AI, take accountability seriously. Don't assume it's someone else's responsibility. Think about what could go wrong. Test for bias. Document what you found. Be transparent about limitations.

Actually taking accountability means moving slower and spending more on safety. But it's the right thing to do, and it's what responsible AI looks like.

FAQ

What does AI accountability actually mean?

AI accountability means that when an AI system causes harm, there's a clear legal and ethical responsibility chain. Someone is responsible for the harm, faces consequences, and has incentives to prevent similar harms in the future. Currently, this chain is diffused across data creators, engineers, companies, and users, so nobody feels fully responsible.

Why is accountability particularly hard with AI systems?

Traditional products have clear cause and effect. A defective car fails in predictable ways. But AI systems emerge behaviors from data patterns that weren't explicitly programmed. When an AI system discriminates, nobody explicitly chose that behavior. Additionally, AI systems are deployed at global scale but regulated locally, creating gaps in accountability across jurisdictions.

Who should be legally liable when an AI system causes harm?

That depends on the situation, but generally: the company that deployed the system should bear primary responsibility, with secondary responsibility potentially shared with data providers if the harm came from biased training data. Engineers shouldn't be personally liable, but the company should be. Users shouldn't be liable for harm caused by the system, though they might be liable for misusing it intentionally.

What would meaningful pre-deployment review of AI look like?

It would involve: independent testing of the system for bias and harmful behaviors, documentation of what the system can and can't do, testing across different demographic groups, simulation of potential harms, and approval only if risks are acceptable. Similar to how pharmaceutical drugs require FDA approval before release to the public.

Can regulation actually work for AI if it's changing so fast?

Yes, but not if regulations are too specific. Regulations should focus on principles (like "AI systems must not systematically discriminate") rather than technical specifics (like "neural networks must have X architecture"). Principle-based regulation can evolve as technology changes, while technique-based regulation becomes obsolete quickly.

How should creators be compensated for data used in AI training?

There are several models: licensing fees for data used in commercial systems, revenue sharing if the AI company profits from the system, or a collective licensing pool where data creators receive compensation based on how much their data was used. The key is that data creators should have opted in and received compensation, rather than having their work used without permission.

Is there any AI system currently operating with strong accountability?

A few. Some companies have voluntarily implemented strong accountability measures. But most don't because it's expensive and gives competitors an advantage. That's why regulation is necessary—to level the playing field and create incentives for accountability across the industry.

What's the difference between responsibility and accountability?

Responsibility is the obligation to do the right thing. Accountability is the mechanism that makes you pay a price if you don't. A company can be responsible for ensuring their AI isn't biased, but without accountability mechanisms (liability, fines, loss of ability to operate), they might choose not to invest in preventing bias.

Can AI companies self-regulate or do we need government enforcement?

Historically, industries that can self-regulate don't. They optimize for profit, not safety. Self-regulation might work for non-consequential issues, but for AI systems that affect people's lives (hiring, healthcare, criminal justice), government oversight is necessary. However, government regulators should work with industry to understand the technology well enough to regulate it effectively.

What happens if accountability frameworks aren't built before AI becomes more powerful?

If accountability lags behind AI capability, you get a situation where powerful systems are making important decisions, but nobody's responsible when things go wrong. This is unsustainable for society. Either accountability catches up, or there's a political crisis that forces a reset. The sooner we build accountability in, the better.

Conclusion: Why This Matters More Than You Might Think

Lanier's core argument is simple: societies cannot function without accountability. When powerful systems can cause harm and nobody's responsible, you get erosion of trust, accumulation of injustice, and eventual political backlash.

We've seen this pattern before. Trust in financial institutions eroded after the 2008 crisis, partly because nobody was held accountable for the recklessness. Trust in tobacco companies eroded once it became clear they knew about health risks but didn't disclose them. Trust in pharmaceutical companies eroded when they were found to have hidden drug side effects.

AI is following the same pattern, just faster. Companies are deploying systems at scale. Harms are accumulating. But accountability mechanisms are weak. Eventually, this breaks down. People stop trusting AI. Regulators crack down hard. The entire industry gets more restrictive.

The question isn't whether accountability will happen. It's when and whether we can do it thoughtfully before the crisis forces us to.

If we wait until massive harm is visible, the backlash might be so strong that we overcorrect. We might ban AI entirely or so tightly regulate it that beneficial uses become impossible. If we build accountability in now, we can enable beneficial AI while preventing harms.

That's the opportunity we're at. We have a brief window—maybe a few years—where we can still shape how AI and accountability develop together. After that window closes, the technology might be too powerful and too entrenched to regulate meaningfully.

What's needed is:

- Clear legal liability for companies deploying AI

- Pre-deployment review for high-risk systems

- Transparency requirements about what systems do and how they work

- Compensation mechanisms for people harmed

- Creators' rights to compensation and consent

- Independent oversight bodies to audit systems

- International coordination to prevent regulatory arbitrage

- Political will to prioritize safety over speed

None of this is technically impossible. None of it is even that expensive in the grand scheme of AI spending. What's needed is a decision that accountability matters more than moving fast.

That decision has to come from multiple places: from regulators who are willing to require it, from companies that are willing to implement it, from engineers that are willing to build it in, and from users that are willing to demand it.

Lanier is essentially saying: don't wait. Build accountability in now. Because societies genuinely cannot function when powerful systems cause harm and nobody's responsible.

And he's right. That's not a controversial or radical position. That's just how functional societies work. The fact that we're debating whether AI companies should be accountable for the systems they deploy is the real issue. Of course they should be. The question is just how we build that accountability in.

The next few years will tell us whether we choose the thoughtful path or the reactive path. But eventually, we'll get there. Accountability always wins in the end. The only question is what the cost of delay will be.

Key Takeaways

- Accountability is missing: When AI systems cause harm, responsibility is diffused across so many actors that nobody feels legally or ethically accountable

- This is unsustainable: Societies need someone to be responsible for powerful systems, otherwise there's no feedback loop to improve them

- Regulation exists but has gaps: The EU's AI Act and other regulations are steps forward, but they don't fully solve the accountability problem due to weak enforcement and definition ambiguity

- Corporate incentives don't align: Companies moving fast and deploying systems with minimal oversight beat companies moving slowly and being cautious, creating a race to the bottom

- Multiple paths forward exist: We can build accountability through legal liability, pre-deployment review, transparency requirements, compensation mechanisms, and independent oversight

- The window is closing: We have a limited time to shape AI accountability before the technology becomes too powerful and entrenched to regulate meaningfully

Related Articles

- UK Police AI Hallucination: How Copilot Fabricated Evidence [2025]

- Grok AI Regulation: Elon Musk vs UK Government [2025]

- Why Grok's Image Generation Problem Demands Immediate Action [2025]

- Apple and Google Face Pressure to Ban Grok and X Over Deepfakes [2025]

- Senate Defiance Act: Holding Creators Liable for Nonconsensual Deepfakes [2025]

- Wikipedia's Enterprise Access Program: How Tech Giants Pay for AI Training Data [2025]

![AI Accountability & Society: Who Bears Responsibility? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-accountability-society-who-bears-responsibility-2025/image-1-1768475390837.jpg)