How UK Police Accidentally Used AI Hallucinations to Ban Football Fans: A Watershed Moment for AI Accountability

It started with a conversation that shouldn't have happened. In October 2025, West Midlands Police sat down with Birmingham's Safety Advisory Group to discuss whether an upcoming Aston Villa match against Maccabi Tel Aviv was safe enough to host with fans present. The stakes felt high. A terror attack on a Manchester synagogue had killed multiple people just days earlier. The atmosphere was tense.

The police made their case. They painted a picture of dangerous Maccabi Tel Aviv supporters who'd caused mayhem in Amsterdam, allegedly targeting Muslim communities, throwing people into rivers, and requiring 5,000 police officers to contain. They presented this as historical fact. A decision was made: ban the fans. The match went ahead on November 6, 2025, but without the Israeli supporters.

Then everything fell apart.

Amsterdam police said the West Midlands account was wildly exaggerated. Dutch authorities confirmed the violence claims were inaccurate or simply fabricated. But the most damning detail? Police included a match that never happened: West Ham versus Maccabi Tel Aviv. It didn't exist. And here's where this story gets genuinely troubling for anyone paying attention to AI in critical infrastructure: that phantom match came from Microsoft Copilot.

For weeks, police chief Craig Guildford denied using AI. He told Parliament twice that officers simply Googled the information. This wasn't true. When pressed further, Guildford finally admitted in a letter dated January 12, 2026, that "the erroneous result concerning the West Ham v Maccabi Tel Aviv match arose as a result of a use of Microsoft Copilot." He claimed he'd only recently learned this fact himself. Nobody was buying it.

This isn't just another story about AI getting things wrong. This is a story about AI hallucinations influencing real-world government decisions that affected real people's rights. It's a story about institutional denial, shifting explanations, and a fundamental failure to understand what AI tools actually are and what they actually do. It's also a story that raises urgent questions about how technology should (and shouldn't) be deployed in sensitive domains like security, law enforcement, and civil liberties.

Let's untangle what happened, why it matters, and what this tells us about where we are with AI in 2025.

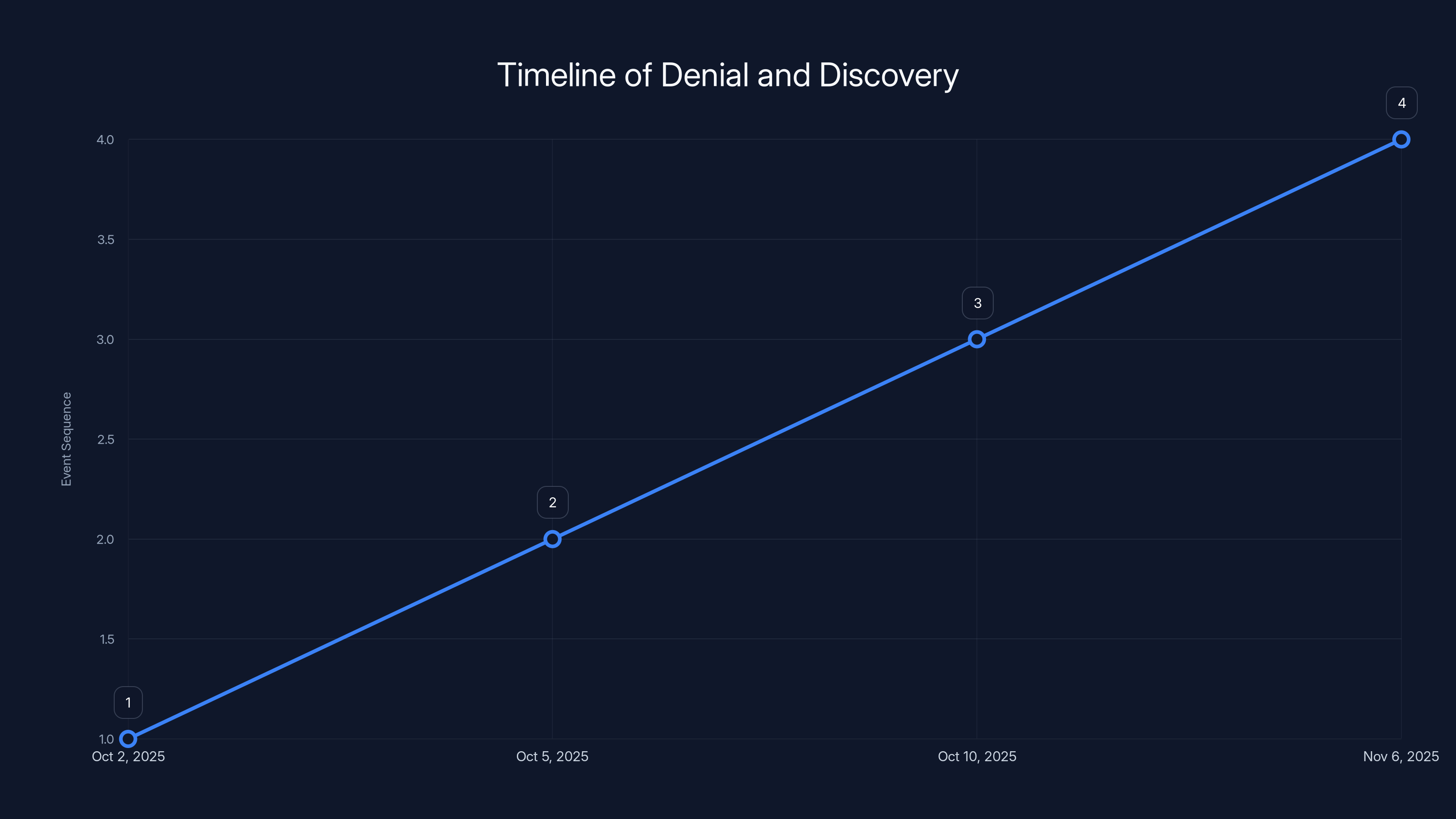

What Actually Happened: The Timeline of Denial and Discovery

Understanding this case requires understanding the sequence of events, because the timeline itself tells a story about institutional response patterns that we're seeing play out across government and corporate entities.

On October 2, 2025, a terror attack occurred at a Manchester synagogue, killing multiple people. The attacker was identified as acting from Islamic extremist motivations. This event immediately became the context for everything that followed. Tensions around security for Jewish events in the UK spiked. This is genuinely important context because it explains why authorities felt pressure to be restrictive, even if their reasoning turned out to be based on fabricated intelligence.

Days later, Birmingham's Safety Advisory Group met to assess risk for the upcoming Aston Villa versus Maccabi Tel Aviv match. West Midlands Police presented intelligence they claimed showed Maccabi Tel Aviv fans were a serious security threat based on their behavior in Amsterdam. The police's narrative was specific: 500-600 fans had targeted Muslim communities the night before the fixture, assaults had occurred, people had been thrown into rivers, and Dutch authorities had needed to deploy 5,000 officers to manage the disorder.

Based partly on this intelligence, the recommendation was made: ban Maccabi Tel Aviv fans from attending the match. The decision was controversial immediately. Jewish organizations and conservative politicians argued this looked like Jewish fans were being pre-emptively punished based on religious identity rather than actual evidence. Counterarguments pointed out that the terror attack and legitimate security concerns justified a precautionary approach. Either way, the match proceeded without fans on November 6.

Here's where the narrative really diverges from reality. BBC journalists started digging into the police claims about Amsterdam. They obtained a letter from the Dutch inspector general confirming that the West Midlands Police account was "highly exaggerated" and materially inaccurate. Amsterdam police pushed back publicly and clearly: the claims about targeting Muslim communities and mass assaults didn't match what actually happened. The numbers were wrong. The characterization was wrong.

Then came the detail that should have been a minor footnote but became the whole story. Police had listed a West Ham versus Maccabi Tel Aviv match as evidence of fan violence. Journalists checked. The match didn't exist. Never happened. The club has no record of it. There was no match to have violence at.

Where did this phantom match come from? That became the central question. Given the impossibility of the false information, and given that this is 2025 and everyone understands what AI is, the obvious answer was AI hallucination. But Craig Guildford, the chief constable of West Midlands Police, initially denied this possibility completely.

Guildford's explanations for the phantom match issue decreased in plausibility from December 2025 to January 2026, indicating potential inconsistencies in the narrative. Estimated data.

The Denial Phase: "We Do Not Use AI"

When hauled before Parliament in December 2025, Guildford was asked directly about AI usage. His answer was categorical: "We do not use AI." He blamed the West Ham phantom match on something else: social media scraping gone wrong. The implication was that automated scraping systems had pulled in corrupted data. This explanation felt plausible enough if you didn't think about it too hard. Maybe some automated system had mixed up data and spit out garbage.

Then in January 2026, Guildford appeared before Parliament again. The phantom match issue hadn't gone away. This time he offered a different explanation: officers had simply Googled it. "On the West Ham side of things and how we gained that information, in producing the report, one of the officers would usually go to a system, which football officers use all over the country, that has intelligence reports of previous games. They did not find any relevant information within the searches that they made for that. They basically Googled when the last time was. That is how the information came to be."

This explanation was more detailed. It was also completely false. But at the time, Guildford was stating it as fact to Parliament. He wasn't being coy or hedging. He was making a clear claim about what had happened.

The problem with both explanations is that they assumed bad data could exist without intentional fabrication somewhere in the pipeline. But the West Ham match didn't exist because bad data got corrupted. It didn't exist because it had never been real. Something had to have generated it from whole cloth. Given that this is an AI hallucination case we're discussing in 2025, the most likely candidate was obvious.

But Guildford had ruled out AI. So what was happening? Was he not aware that his department used Copilot? Or was he aware but attempting to manage the optics by claiming they didn't use AI tools?

This distinction matters because it changes the nature of the institutional failure. If Guildford genuinely didn't know his officers were using Copilot for intelligence work, that's a massive failure of institutional awareness. If he knew and was denying it, that's a failure of integrity. The truth appears to be somewhere in between.

The timeline highlights key events from the terror attack on October 2 to the fan ban decision on November 6, showing how initial intelligence influenced decisions. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Admission: The Friday Afternoon Email That Changed Everything

On Friday afternoon, January 10, 2026, Guildford apparently learned something new. By Monday, January 12, he sent a letter admitting the truth: Microsoft Copilot had been used to research the phantom West Ham match. This wasn't a gradual realization. This was a sudden, complete reversal of his parliamentary testimony.

The letter is carefully worded. Guildford claims he "only recently became aware" that Copilot was involved. He says that "up until Friday afternoon" he had understood the West Ham match came from Google searches. The implication is that someone finally told him what actually happened, or someone finally checked, and the truth emerged. Either way, his previous statements to Parliament were now officially inaccurate.

What's remarkable about the letter is what it doesn't explain. It doesn't explain how officers had access to Copilot in the first place. It doesn't explain whether this was authorized or rogue usage. It doesn't explain whether there was training on how to use Copilot for intelligence work. It doesn't explain why nobody had caught this error before it influenced a major public safety decision.

Guildford added that he "had not intended to deceive anyone" with his previous statements. This statement might be technically true, but it's also somewhat irrelevant. Whether deception was intentional or whether it resulted from profound organizational opacity, the effect was the same: Parliament and the public were given inaccurate information about how a consequential decision had been made.

Why This Matters: AI Hallucinations Aren't Just Technical Bugs Anymore

If you read most coverage of AI hallucinations, they're treated as technical problems. An AI model makes up information that sounds plausible but is false. It's presented as a fascinating failure mode of large language models. Chat with Chat GPT long enough and it will confidently assert facts that are completely made up. Same with Copilot, Claude, Gemini, and every other LLM currently in operation. This is a known, documented characteristic of how these systems work.

But when hallucinations influence government decision-making, they stop being technical problems and become governance problems. When a police force uses an AI tool to research intelligence and doesn't catch that the tool has fabricated information, when that fabricated intelligence influences a decision to restrict people's civil liberties, when officials then deny that AI was involved at all, we've crossed a line.

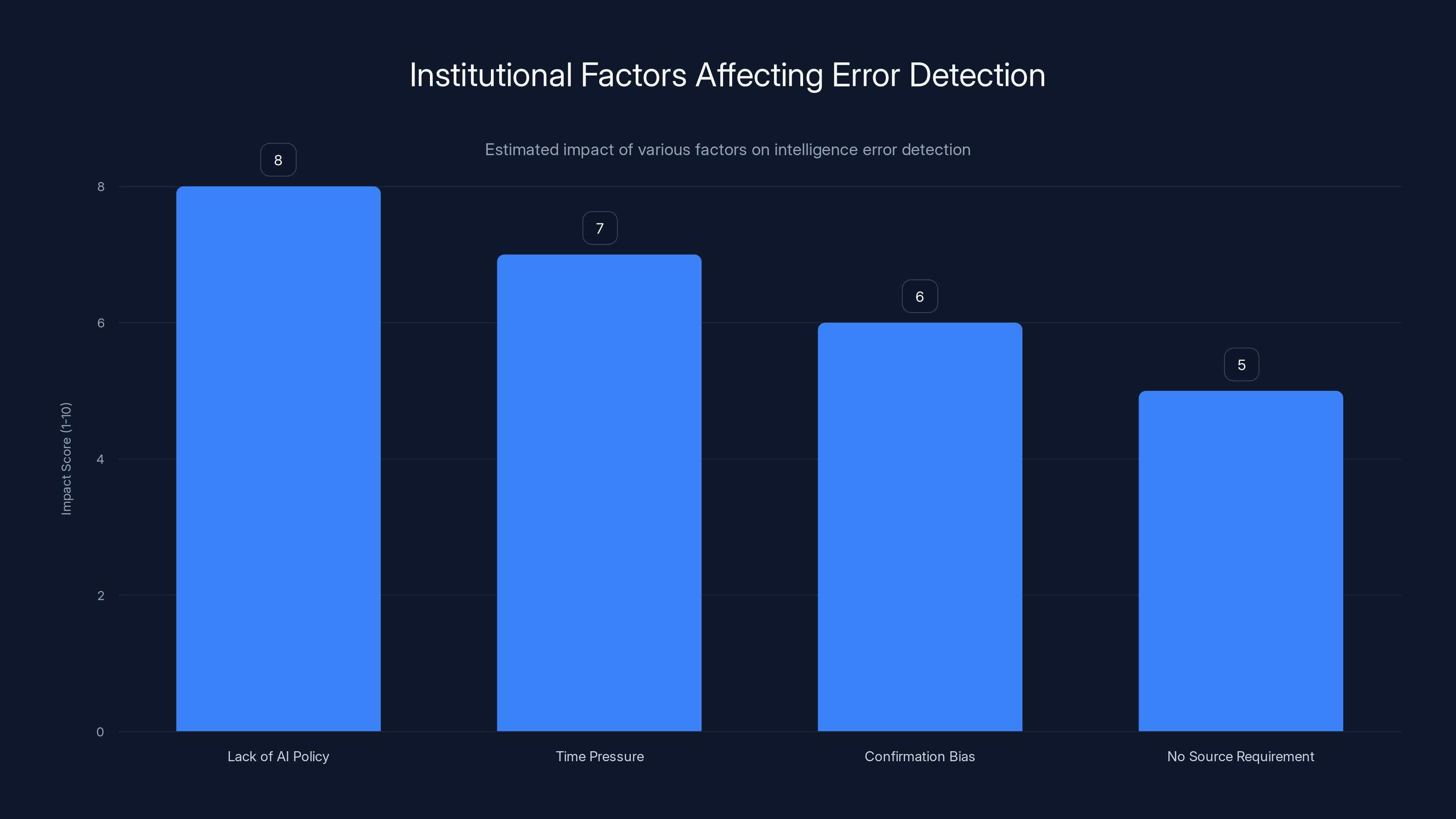

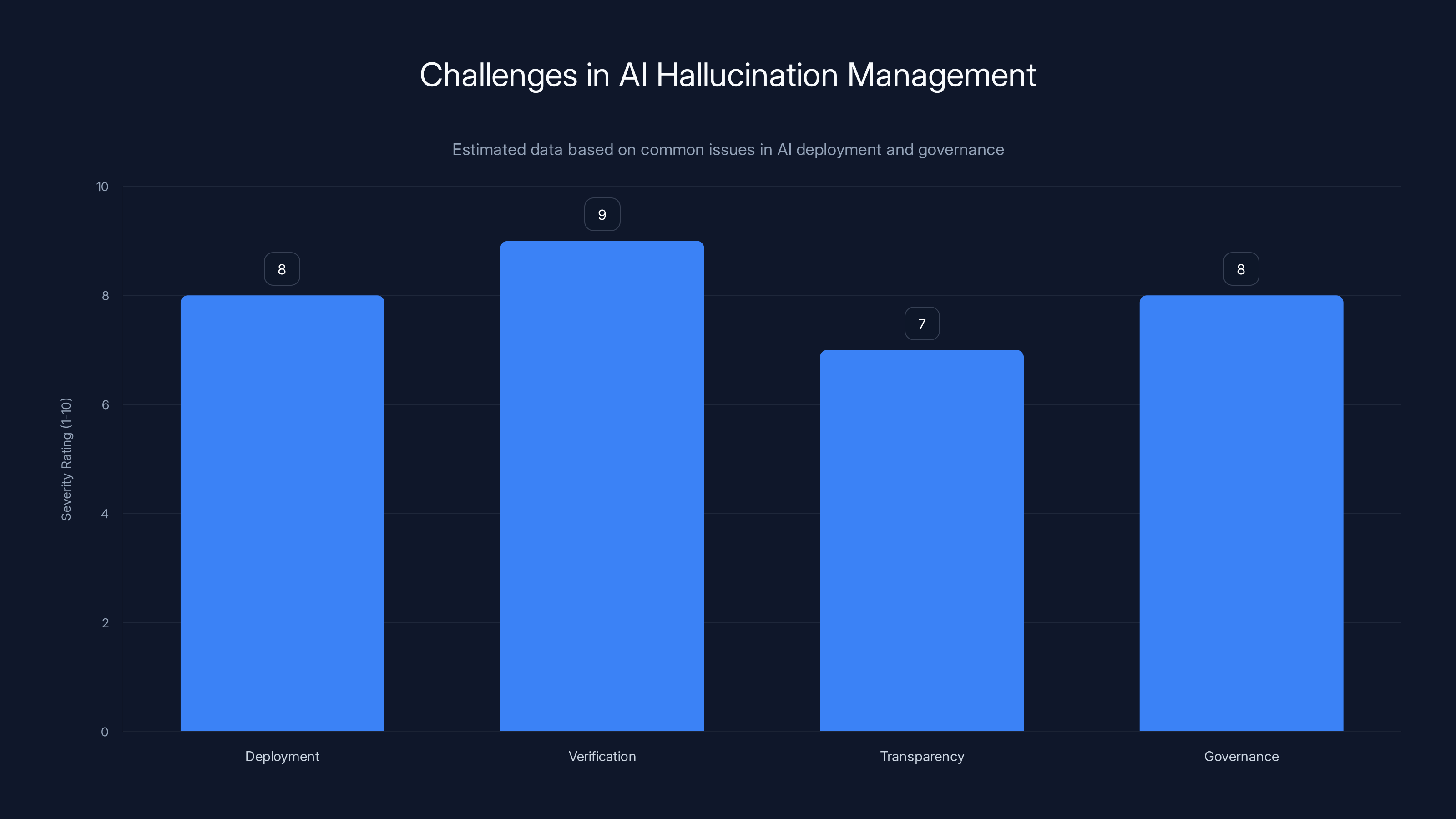

The West Midlands Police case reveals several systemic failures that go way beyond "the AI made something up." First, there's the deployment problem. Police officers were apparently using Microsoft Copilot to conduct intelligence research without formalized policies about how to use it, when to use it, what to verify, and how to assess information quality. This is like finding out that crime scene investigators have been using Wikipedia to identify forensic techniques.

Second, there's the verification problem. Even if you use an AI tool, you need robust processes to verify its outputs before acting on them. The fact that a completely fabricated match made it into an intelligence report that influenced a major public safety decision suggests there was no meaningful verification process at all.

Third, there's the transparency problem. When authorities are asked about how decisions were made, they should know. They should be able to say, accurately, what tools and processes were involved. Guildford couldn't (or wouldn't) say this initially. This suggests either that the organization had such poor governance that the chief constable didn't actually understand what his officers were doing, or that there was a deliberate opacity.

Fourth, there's the accountability problem. If an AI tool has hallucinated information that influenced a decision affecting public rights, there should be clear mechanisms to identify this, correct it, and prevent it from happening again. Instead, what happened here was that the error was discovered through external investigation, the organization denied it, and only after significant pressure did the truth emerge.

For anyone paying attention to AI governance in 2025, this case is a window into what happens when powerful technology gets deployed in sensitive domains without adequate institutional preparation.

External verification tools and human review are currently the most effective strategies for mitigating AI hallucinations, though none are perfect. Estimated data.

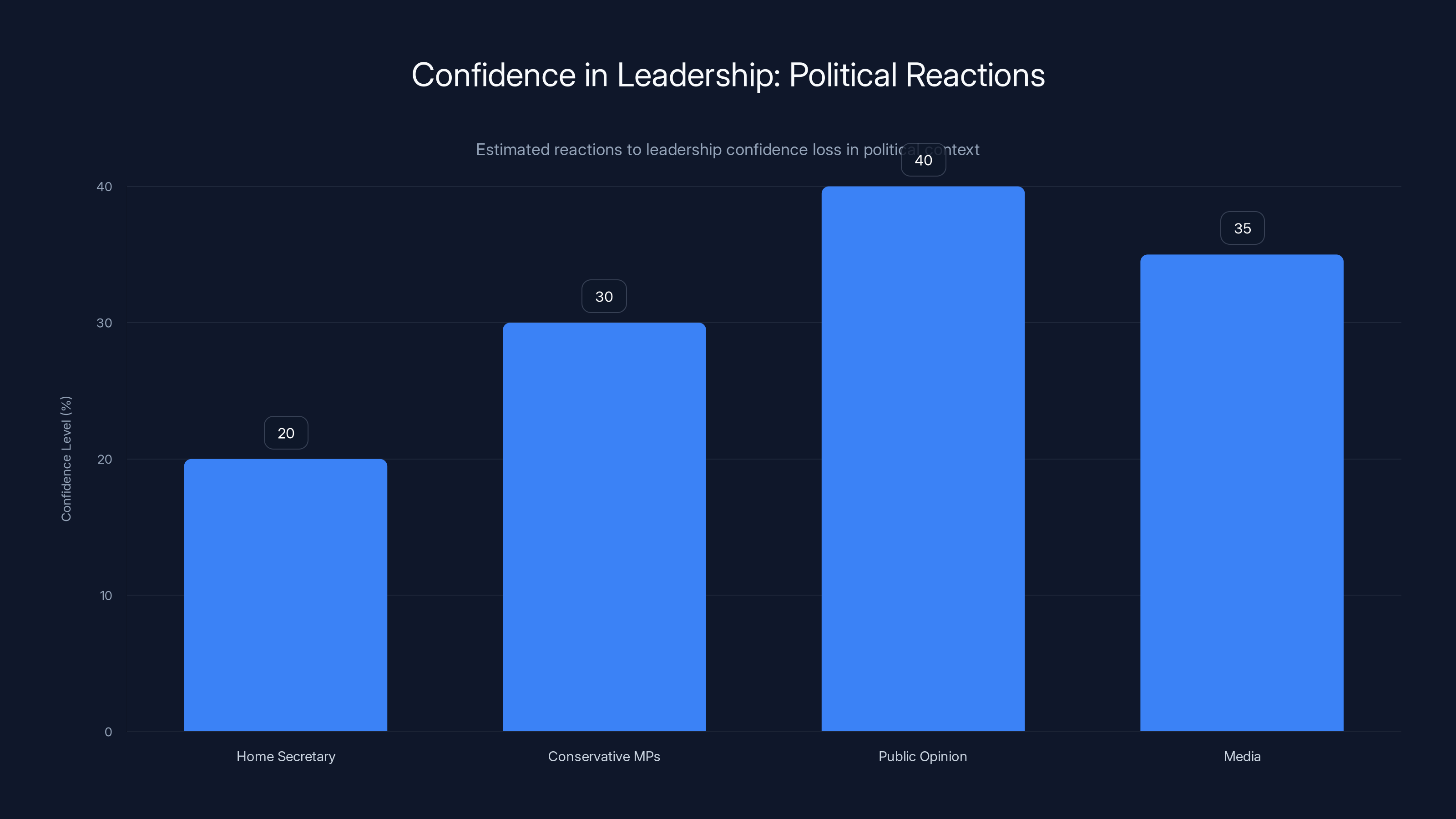

The Political Fallout: When Leadership Loses Confidence

Political responses to institutional failures have predictable patterns. Someone has to be blamed. Someone has to apologize. Someone usually has to resign. In this case, the someone was Craig Guildford.

Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood gave a statement in the House of Commons that was remarkable for its thoroughness in throwing Guildford under the bus. She called out the confirmation bias that had apparently infected the police investigation. She highlighted that the claims about Amsterdam were "exaggerated or simply untrue." But her most cutting observation was about the AI denial itself.

Mahmood pointed out that Guildford had claimed "AI tools were not used to prepare intelligence reports" but now the organization was blaming AI hallucination for the false match. The contradiction was stark. Either AI was or wasn't used. You can't deny using technology and then later claim that technology caused an error. Well, technically you can, but it doesn't look good politically.

Mahmood concluded that this was a "failure of leadership" and that Guildford "no longer has my confidence." That phrase—"no longer has my confidence"—is politically significant in the UK context. When a Home Secretary says this about a police chief, it's essentially a death sentence for the appointment. The chief constable's position became untenable.

Conservative opposition wasn't far behind. MPs like Nick Timothy erupted on social media and in Parliament about the misuse of AI by police. Timothy emphasized that the police had "denied it to the home affairs committee" and had "denied it in FOI requests." They claimed to have "no AI policy." This meant officers were "using a new, unreliable technology for sensitive purposes without training or rules."

The political consensus that emerged was clear: this situation was unacceptable. The questions were now about whether systemic changes would follow.

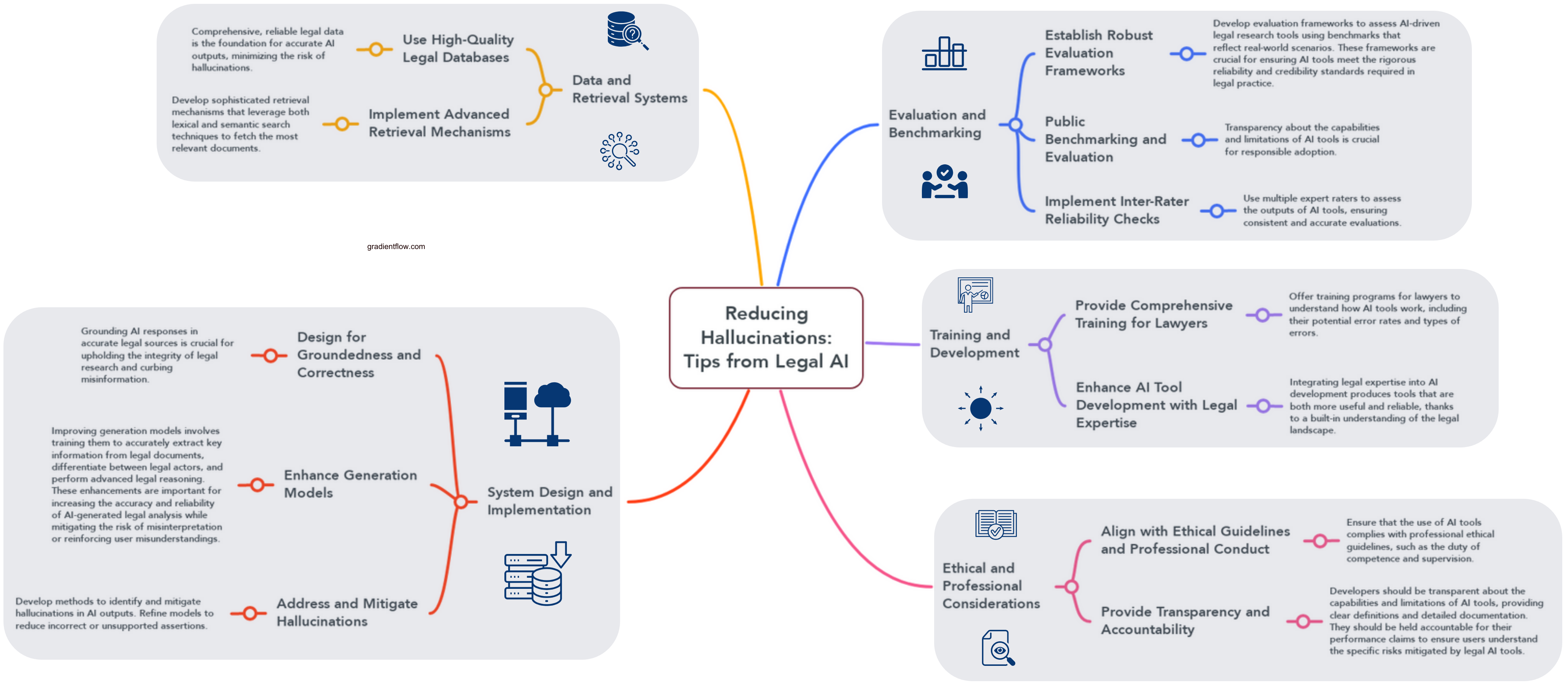

Understanding AI Hallucinations: Why This Happens and Why It's Hard to Catch

Before we talk about solutions, we need to understand the technical reality of what happened. Microsoft Copilot (like all current large language models) operates by predicting the next most likely word in a sequence. Given a prompt like "West Ham vs Maccabi Tel Aviv match date," the model generates a response by calculating probabilities. When the model doesn't have reliable information about a topic, those probability distributions become essentially guesses based on training data patterns.

In this case, the model apparently saw a prompt asking about a West Ham vs Maccabi Tel Aviv match and generated a response asserting that such a match occurred. The model didn't know it was fabricating. It was just generating the most statistically likely continuation of the token sequence. From the model's perspective, it was doing exactly what it's designed to do.

But here's the critical part: LLMs have no internal mechanism to flag uncertainty. They can't say "I'm not sure about this" or "I'm making this up." They output with the same confidence whether they're drawing on genuine training data or hallucinating. To a user unfamiliar with how these systems work, the confident assertion of false information is indistinguishable from the confident assertion of true information.

This is a fundamental limitation of current LLM architecture. Companies have implemented various mitigation strategies. Some models have been fine-tuned to express uncertainty more often. Some systems have been given access to external tools like search engines to verify information. Some implementations require human review of outputs. But none of these mitigations are perfect, and many require extra effort from users.

If a police officer uses Copilot naively, simply asking it a question and trusting the answer, they'll get unreliable results on topics where the training data is sparse or contradictory. A match between a UK team and an Israeli team in October 2025 is exactly the kind of specific, recent event that might have limited training data. The model might have seen patterns in training data about football matches and simply generated a plausible-sounding response.

What's particularly interesting about this case is that the hallucination wasn't random gibberish. It was specifically crafted in a way that fit the narrative the police were already constructing. West Ham is a real team. Maccabi Tel Aviv is a real team. Football matches are real events. The hallucination involved combining real elements in a false configuration. This is actually harder to catch than obvious nonsense would be.

Lack of a clear AI policy had the highest estimated impact on the failure to catch errors, followed by time pressure and confirmation bias. Estimated data based on context.

The Institutional Context: Why Police Didn't Catch This Error

The technical explanation for hallucination doesn't fully explain why the police failed to catch it. Organizations have quality control processes for a reason. Intelligence reports are supposed to be checked. Sources are supposed to be verified. Claims are supposed to be corroborated. So why did a completely fabricated match make it into an intelligence report?

Several institutional factors seem relevant. First, there was apparently no established process for using AI tools in intelligence work. If a technology is new to an organization, and there's no policy guiding its use, then individuals make their own decisions about how to deploy it. Some officers might have been using Copilot as a quick research tool without understanding its limitations. They might have thought of it as similar to a Google search, not realizing that AI-generated content requires different verification protocols than search results.

Second, there might have been time pressure. Intelligence work often operates under time constraints, especially around events with security implications. If officers felt rushed to produce intelligence, they might have cut corners on verification. Using an AI tool feels faster than traditional research, but only if you don't account for the time needed to verify outputs.

Third, there might have been confirmation bias in the review process. Once the police had decided that Maccabi Tel Aviv fans were a security threat (based on real incidents in Amsterdam that were, to be fair, somewhat documented), the organization might have been looking for information that confirmed this belief. A report mentioning the West Ham match, even if completely fabricated, might have passed through review because it fit the existing narrative.

Fourth, there was apparently no requirement to explicitly cite sources for intelligence claims. If the report had included a source attribution ("According to Copilot, West Ham played Maccabi Tel Aviv on..."), someone might have questioned it. Without explicit sourcing, a fabricated claim can blend into the background of real claims.

Institutional factors like these are often more important than technical factors in explaining organizational failures. A well-run organization with good governance processes would catch AI hallucinations even if the AI itself hasn't improved. A poorly-run organization with weak processes won't catch hallucinations no matter how accurate the AI becomes.

The Bigger Picture: AI in Government and Law Enforcement

The West Midlands Police case isn't isolated. It's part of a broader pattern of government and law enforcement agencies experimenting with AI tools without adequate governance frameworks. Police departments around the world have been piloting facial recognition systems, predictive policing algorithms, and risk assessment tools. Many of these deployments have preceded formal policy frameworks.

The difference with the Copilot case is that it's so explicitly caught. The hallucination created evidence of itself through impossibility. A match that never happened is easy to verify never happened. But consider other domains where AI hallucinations might be harder to catch.

What if the error had been subtler? What if an AI tool had generated a slightly inaccurate account of a real event, inflating numbers or mischaracterizing details? Those errors would be much harder to spot, especially if they confirmed existing institutional beliefs. You might never discover them unless someone independently investigated, as the BBC did in this case.

This raises uncomfortable questions about how many decisions influenced by AI hallucinations are already embedded in government systems without anyone knowing. How many immigration decisions, benefit determinations, law enforcement recommendations, or regulatory actions have been influenced by AI systems generating false information that nobody caught?

The answer is probably more than we'd like to think. And that's the real story here. The West Midlands Police case is notable not because it's the worst misuse of AI in government, but because it's one of the few cases where the error was detected, investigated, and publicly acknowledged. For every detected case, there might be dozens of undetected cases.

Estimated data suggests that verification is the most severe challenge in managing AI hallucinations, followed by deployment and governance issues.

What Regulation Might Look Like: Learning from the Copilot Failure

If we're going to prevent similar incidents, what should regulation or institutional policy look like? Several principles emerge from analyzing this case.

First, there needs to be explicit disclosure of AI tool usage in sensitive domains. If a government agency uses an AI tool to inform a decision that affects people's rights, that usage should be documented and disclosed. This isn't about banning AI use—it's about transparency. It's about enabling oversight and accountability.

Second, there need to be mandatory verification protocols for AI-generated information. Depending on the context, this might mean requiring independent source confirmation, requiring multiple AI systems to agree, requiring human expert review, or requiring combination with traditional research methods. The specific protocol should depend on how consequential the decision is.

Third, there need to be AI literacy requirements for agencies using these tools. Police officers shouldn't be deploying Copilot for intelligence work without understanding how LLMs work, what hallucinations are, and what verification processes are necessary. This is a training and education problem.

Fourth, there need to be clear audit trails. When AI tools are used, organizations should maintain records of prompts, outputs, and verification steps. This enables after-the-fact investigation if something goes wrong. The West Midlands Police case was only discovered because external parties investigated. Internal audit trails would enable earlier detection.

Fifth, there need to be accountability mechanisms. If an organization deploys an AI tool negligently and that negligence causes harm, there should be consequences. This could mean professional consequences for individuals, institutional consequences for organizations, or legal consequences depending on jurisdiction and context.

The UK government has begun developing AI governance frameworks, but much of this remains in early stages. Other jurisdictions are further ahead. The EU's AI Act, for instance, imposes requirements around documentation and transparency for high-risk AI applications. But even well-intentioned regulation will only work if it's actually enforced.

The Technical Response: How AI Companies Are Reacting

Microsoft, for its part, has been relatively quiet about the West Midlands Police case. The company hasn't made major public statements defending Copilot or explaining how hallucinations happen. Instead, the company appears to be focused on technical improvements.

Recent updates to Copilot have included enhanced grounding features that allow the system to cite sources for factual claims. When used in certain configurations, Copilot can now point to specific sources for information rather than just generating text. This addresses one aspect of the hallucination problem: if the AI asserts something factual, at least now it can potentially point to where it believes that information comes from.

But this is still not sufficient for high-stakes domains like law enforcement. Citing sources doesn't mean the sources are accurate. An AI system that can point to a web page and say "this is where I got this information" is marginally better than a system that can't, but it's not a complete solution. If that web page contains false information, or if the AI misinterpreted that web page, the problem persists.

Other AI companies are working on similar improvements. Claude, made by Anthropic, has been trained with enhanced transparency about uncertainty. GPT-4, made by Open AI, has access to search capabilities in some configurations. But all of these are incremental improvements to systems that have a fundamental limitation: they can generate confident-sounding assertions about things they don't actually know.

The real solution isn't just technical. It's institutional and legal. We need organizations to treat AI tools as tools that require careful deployment, not as solutions that can simply be applied without thought. We need regulators to enforce standards around transparency and accountability. And we need the public to understand what these systems actually are and what they actually can do.

Estimated data shows low confidence levels across key stakeholders following leadership controversy. Home Secretary's confidence is notably low, reflecting political fallout.

International Perspectives: How Other Countries Are Handling AI in Government

The UK isn't alone in grappling with how to govern AI use in sensitive domains. Other countries have begun developing frameworks.

The European Union's AI Act, which entered force in early 2025, imposes strict requirements on high-risk AI applications. Law enforcement uses of AI are explicitly categorized as high-risk, meaning they require extensive documentation, transparency, and human oversight. This framework would likely prevent the kind of casual Copilot usage that led to the West Midlands Police problem. But the EU approach is also more restrictive and potentially slows innovation.

The United States has taken a more fragmented approach. Federal agencies are developing guidelines, but there's no single overarching legal framework. Some states have passed their own AI regulation. Cities like San Francisco have implemented restrictions on facial recognition technology used by police. But there's significant variation in how aggressively different jurisdictions are approaching AI governance.

Canada has been developing principles-based guidance on AI governance in government. The emphasis is on transparency, accountability, and public trust. But like most principles-based approaches, the specifics of enforcement remain unclear.

China has taken a more top-down approach, with strict control over what AI systems can be used for and explicit party oversight of AI deployment. This approach prevents unauthorized usage like the West Midlands Police case, but at the cost of less innovation and less public agency.

The common thread across these approaches is recognition that AI in government, particularly in law enforcement and security contexts, requires special consideration. The West Midlands Police case will likely accelerate these governance efforts globally.

The Human Cost: How the Decision Affected Real People

Amidst all the discussion of AI, hallucinations, and institutional governance, it's easy to lose sight of the human dimension. Real people were affected by the decision to ban Maccabi Tel Aviv fans from the match.

Fans who had traveled to Birmingham expecting to attend found themselves excluded. Family members who had hoped to share the experience together were separated by the ban. The decision sent a message about what threats were being prioritized and what groups were being viewed with suspicion.

From one perspective, the security concerns were legitimate. A terror attack had occurred days earlier. Heightened vigilance made sense. From another perspective, the ban looked like collective punishment based on nationality and religion, informed by exaggerated or false intelligence.

What's particularly troubling is that the false intelligence came from an AI hallucination. If the decision had been made on the basis of genuine security concerns based on real evidence, there would be room for legitimate disagreement about whether it was the right call. But a decision influenced by false information generated by an AI tool that the decision-makers initially denied using—that's something else entirely.

This is part of why the institutional opacity matters so much. People deserve to know how decisions affecting their rights are made. They deserve to know what evidence is being used. They deserve to know if that evidence came from AI systems. The repeated denials that AI was involved, followed by the eventual admission, undermined public trust.

Looking Forward: Building Better AI Governance

The West Midlands Police case is a watershed moment not because it's unprecedented, but because it's been thoroughly investigated and publicly acknowledged. The case provides a template for how AI governance failures can occur and how they can be detected.

Moving forward, we should expect several developments. First, government agencies will likely develop more formal policies around AI tool usage. The days of officers casually using Chat GPT or Copilot without institutional guidance are probably ending. Second, there will be more emphasis on AI literacy for government employees, particularly those in sensitive roles. Understanding how AI works and what hallucinations are should become standard training. Third, there will be regulatory requirements around transparency and documentation of AI usage, at least in high-stakes domains.

But regulation can only go so far. The real protection against AI failures in government is organizational culture. Organizations need to treat new technology with appropriate skepticism until they understand it. They need to maintain robust verification processes. They need to embrace transparency about how decisions are made. They need leaders who understand what's happening in their organizations and take responsibility for it.

The good news is that these are learnable lessons. The bad news is that learning them requires admitting failures and making genuine institutional changes. History suggests that happens slowly and often only after crises make change unavoidable.

The West Midlands Police case might be that kind of crisis. It certainly has enough attention focused on it to make ignoring the lessons impossible. Whether that attention translates into meaningful change in how governments deploy AI remains to be seen.

FAQ

What exactly is an AI hallucination?

An AI hallucination occurs when a language model generates false or fabricated information with confidence, as if it were true. The model isn't intentionally lying—it's generating text based on statistical patterns in its training data. When information is sparse or contradictory, the model's probability distributions become essentially guesses, resulting in confident assertions about things that never happened. In the West Midlands Police case, Copilot generated a match between West Ham and Maccabi Tel Aviv that never actually took place.

Why didn't the police catch the fabricated match immediately?

The fabricated match wasn't obvious nonsense—it was cleverly constructed from real elements. West Ham is a real team, Maccabi Tel Aviv is a real team, and football matches between various teams do happen. The specific combination (West Ham vs Maccabi Tel Aviv) was false, but it fit into the existing narrative the police were constructing about Maccabi Tel Aviv fans being a security threat. Additionally, there appeared to be no formal verification process requiring sources to be checked or cross-referenced.

How did BBC journalists discover the phantom match wasn't real?

BBC journalists investigated the police's claims about Maccabi Tel Aviv fan violence as part of broader reporting on the decision to ban fans from the match. When they checked the specific claim about a West Ham match, they contacted West Ham and verified that no such match had occurred. This external investigation uncovered the error that internal police processes had missed.

What did Craig Guildford claim was the cause before admitting to AI usage?

Guildford initially blamed "social media scraping gone wrong," suggesting that automated systems had corrupted data. Later, he changed his explanation and told Parliament that officers had simply Googled for information about when West Ham last played. Both explanations were designed to avoid mentioning AI usage, even though AI (specifically Microsoft Copilot) was the actual source of the fabricated information.

What consequences did Guildford face for the false statements to Parliament?

After the Home Secretary stated that Guildford "no longer has my confidence," his position became politically untenable. Conservative opposition also called for his resignation. The combination of institutional and political pressure effectively ended his tenure as chief constable. He had to resign or face forced removal.

How is this case connected to broader government AI policy?

The West Midlands Police case has become a catalyst for discussions about AI governance in government more broadly. It demonstrates risks of deploying AI tools in sensitive domains without adequate policies, training, or verification processes. The case has likely accelerated efforts to develop formal AI governance frameworks across multiple countries and government sectors.

What changes might prevent similar incidents in the future?

Experts recommend several interventions: mandatory disclosure of AI tool usage in sensitive decisions, mandatory verification protocols for AI-generated information, AI literacy training for government employees, clear audit trails documenting AI tool usage, and accountability mechanisms for negligent deployment. Additionally, government agencies should develop formal policies governing when and how AI tools can be used for high-stakes decisions.

Is Microsoft Copilot being restricted from law enforcement use?

Microsoft hasn't announced blanket restrictions on law enforcement use of Copilot, but the West Midlands Police case has prompted discussions about appropriate guardrails. Some jurisdictions may implement policies restricting or controlling how AI tools can be used for intelligence work. The focus is typically on improving verification processes and transparency rather than outright bans.

How do other countries regulate AI usage in government?

The European Union's AI Act explicitly categorizes law enforcement use of AI as high-risk, requiring extensive documentation and human oversight. The United States takes a more fragmented approach with varying regulations by agency and state. Canada emphasizes transparency and accountability through principles-based guidance. These varied approaches reflect different cultural and regulatory philosophies around government technology deployment.

What's the difference between this case and typical AI hallucination examples?

Most AI hallucination examples are relatively harmless—a chatbot making up false information about a fictional topic, or generating plausible-sounding but incorrect advice. The West Midlands Police case is different because the hallucination directly influenced a government decision that restricted people's civil liberties. This transforms the issue from a technical curiosity into a governance and accountability problem with real-world consequences for real people.

Conclusion: A Moment of Reckoning for AI in Critical Infrastructure

The West Midlands Police case isn't an isolated incident of technology gone wrong. It's a symptom of a broader challenge: institutions are deploying powerful AI tools without adequate preparation, governance, or understanding. The fact that this particular failure was caught, investigated, and publicly acknowledged is actually somewhat unusual. Most AI hallucinations in government systems probably go undetected.

What makes this case significant is that it brought together several elements that force accountability. There was an external investigation by serious journalists. There was public and political interest. There were repeated contradictory statements that finally broke down. There was enough pressure to force institutional admission of error.

But the structural problem remains. Governments around the world are adopting AI tools to make decisions about immigration, benefits, criminal justice, security, and countless other domains that affect people's lives. Most of these deployments are happening without the kind of robust governance frameworks, verification processes, and transparency requirements that would protect against hallucinations and other AI failures.

The good news is that this is solvable. We don't need to wait for AI to become more reliable. We need to deploy it more carefully. We need organizations to understand what they're using, why they're using it, and what could go wrong. We need verification processes that catch errors before they influence consequential decisions. We need transparency so that people understand how decisions affecting them are made.

The West Midlands Police case provides a template for what can go wrong. It also provides a template for what accountability looks like when things go wrong. The question now is whether this case becomes an isolated incident that gets forgotten, or whether it catalyzes the kind of institutional change that makes similar failures less likely in the future.

Given that multiple countries are already developing or tightening AI governance frameworks, and given that this case has received significant attention, the trajectory seems to be toward change. But regulation alone won't solve the problem. Individual organizations need to embrace a culture of careful technology deployment, robust verification, and genuine accountability.

The police chief who denied using AI and then had to admit he was using it learned this lesson the hard way. Hopefully, other institutions will learn it without requiring public scandals to force the lesson home.

Key Takeaways

- West Midlands Police used Microsoft Copilot to research intelligence, leading to a fabricated West Ham vs Maccabi Tel Aviv match that influenced the decision to ban fans

- Police initially denied AI usage multiple times to Parliament before admitting the hallucination on January 12, 2026

- AI hallucinations in government decisions affecting civil liberties represent a critical governance and transparency problem beyond just technical failures

- Organizations deploying AI tools in sensitive domains lack adequate verification processes, AI literacy training, and institutional policies to catch hallucinations before decisions are made

- International regulatory responses vary from EU's strict high-risk classification requiring transparency to fragmented US state-by-state approaches, with governments accelerating AI governance frameworks

Related Articles

- OpenAI Contractors Uploading Real Work: IP Legal Risks [2025]

- Indonesia Blocks Grok Over Deepfakes: What Happened [2025]

- Grok Image Generation Restricted to Paid Users: What Changed [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why the Paywall Isn't Working [2025]

- Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself: The New AI Likeness Battle [2025]

- UK Scraps Digital ID Requirement for Workers [2025]

![UK Police AI Hallucination: How Copilot Fabricated Evidence [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uk-police-ai-hallucination-how-copilot-fabricated-evidence-2/image-1-1768408687940.jpg)