The AI Paradox: Promised Productivity, Hidden Pressure

Here's what nobody tells you about AI in the workplace: it doesn't actually make work easier. It just makes work different.

You've probably heard the pitch. AI automates routine tasks. It handles administrative burden. It frees up humans to focus on high-value work. All true. Except for one major detail that's causing serious problems inside organizations worldwide: when AI takes over the routine stuff, someone still has to babysit it.

A groundbreaking report published in an Occupational Medicine journal has quietly exposed something the tech industry has been glossing over. As AI systems become integrated into daily workflows, workers aren't getting lighter workloads. They're getting heavier ones. And their paychecks? They're staying exactly the same.

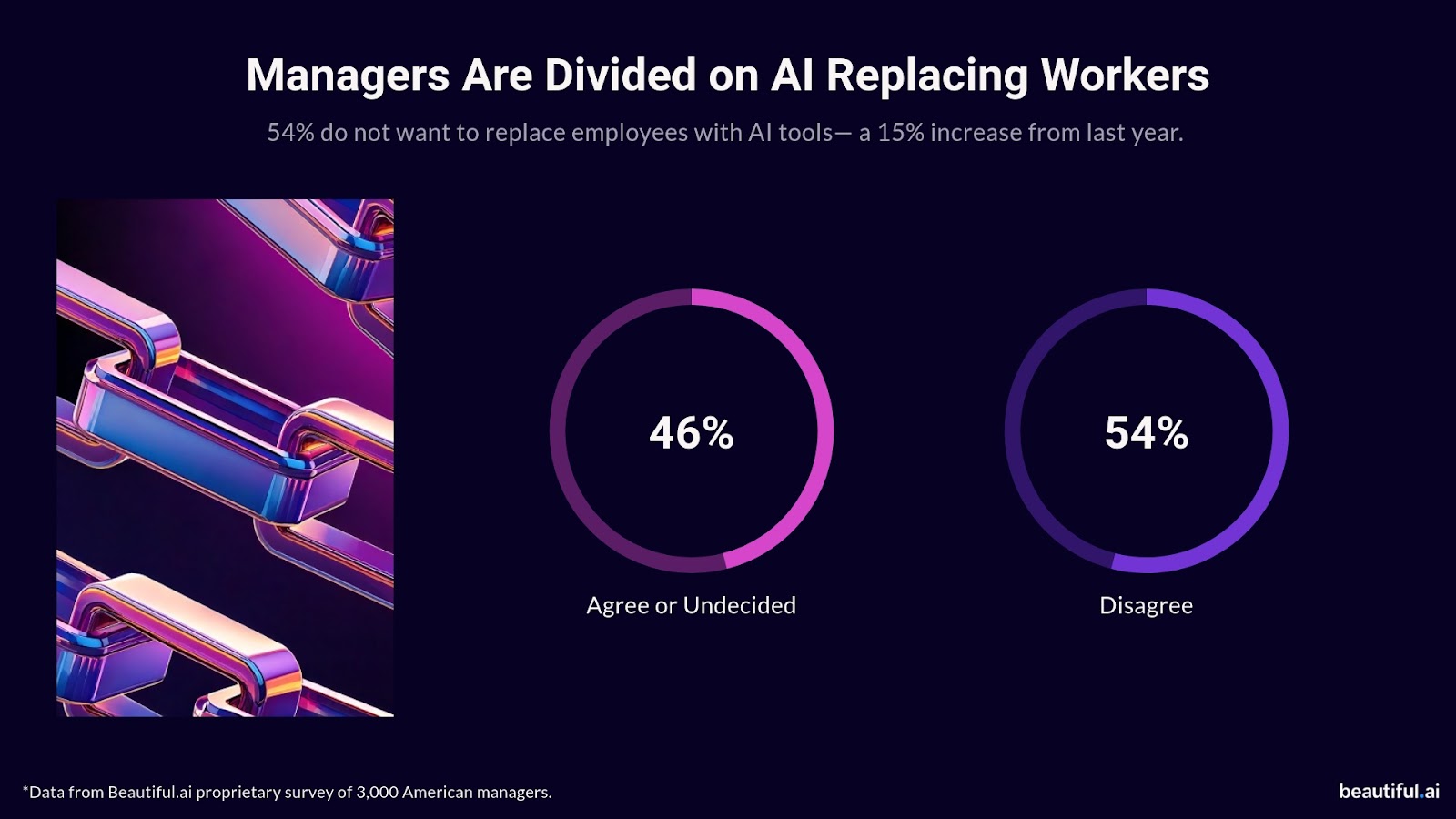

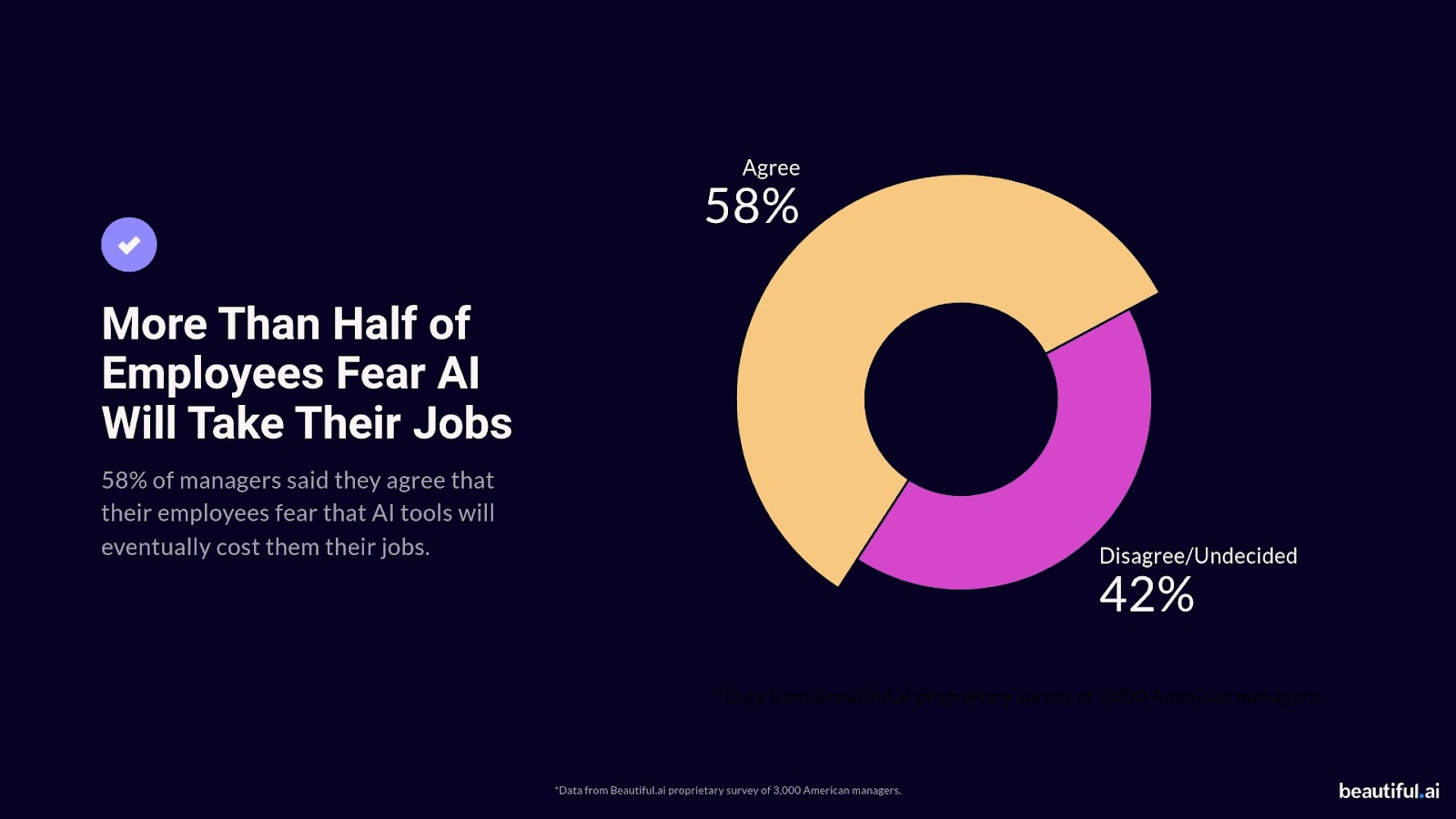

The research uncovered a fundamental flaw in how organizations are implementing AI. Managers see AI as a replacement for people, or at least as a way to do more with existing staff. But what's actually happening is that employees are being handed a new set of responsibilities: managing, checking, correcting, and validating the work AI produces. The job title might say "analyst" or "operator," but the actual role has morphed into something closer to "AI supervisor."

This creates what researchers call "hidden workloads." They're hidden because they're not officially tracked in job descriptions. They're hidden because managers don't budget for them. And they're hidden because most employees just absorb the extra work without complaint, hoping that eventually the technology will catch up to the hype.

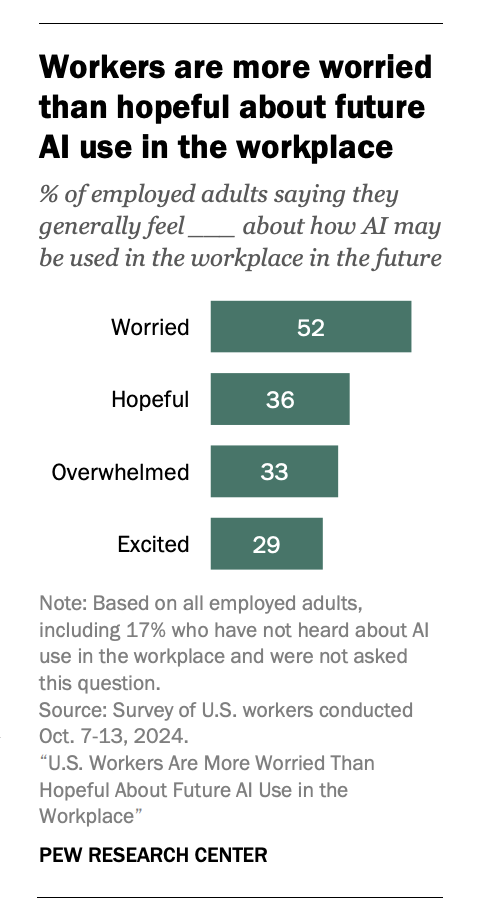

But there's a cost to this invisibility. Stress increases. Burnout accelerates. And the supposed efficiency gains vanish because humans spend hours fixing problems that shouldn't exist in the first place.

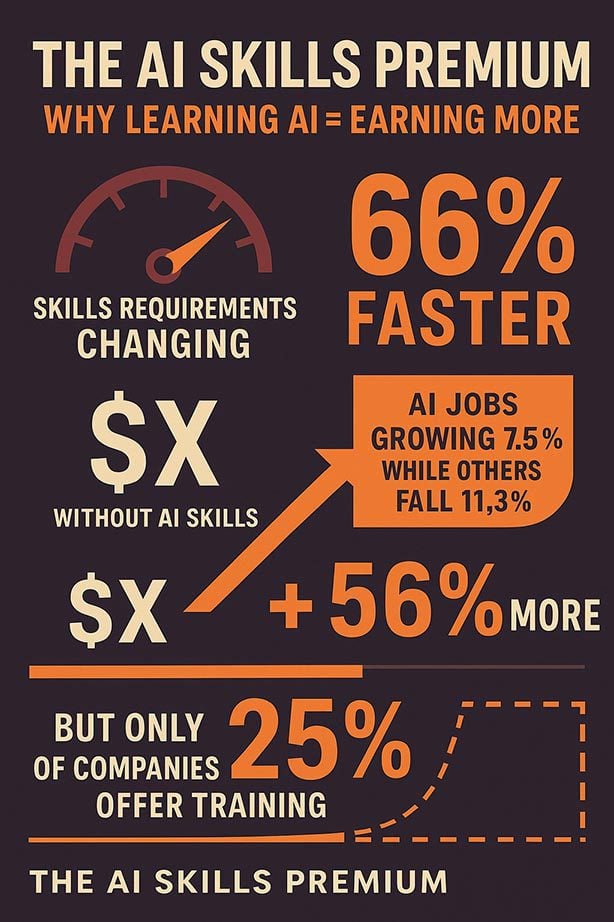

What makes this worse is the psychology of how managers perceive AI-assisted roles. When a job is perceived as easier, salary expectations drop. A role that previously required years of experience and commanded premium pay gets reclassified as entry-level because "the AI does most of the thinking now." Except it doesn't. The human has just become a more complex problem-solver, working faster under more pressure, for less money.

This isn't just about individual paychecks. This is about sustainability. If we implement AI in ways that make work worse for the people doing it, we're not building a future of productivity. We're building a future of burnout, attrition, and organizations that can't retain talent because nobody wants the job.

TL; DR

- AI creates hidden workloads: Employees now manage, check, and correct AI outputs that weren't supposed to require human oversight

- Pay doesn't follow responsibility: Roles perceived as "easier" due to AI aren't receiving corresponding salary increases despite added complexity

- Stress and burnout are increasing: Workers face higher pressure without training or resources to manage AI oversight duties

- Job displacement is accelerating: Entry-level positions are being redefined or eliminated as AI takes on junior-level work

- Sustainability requires rethinking: Organizations need to deliberately design human-AI workflows that create real productivity gains without exploitation

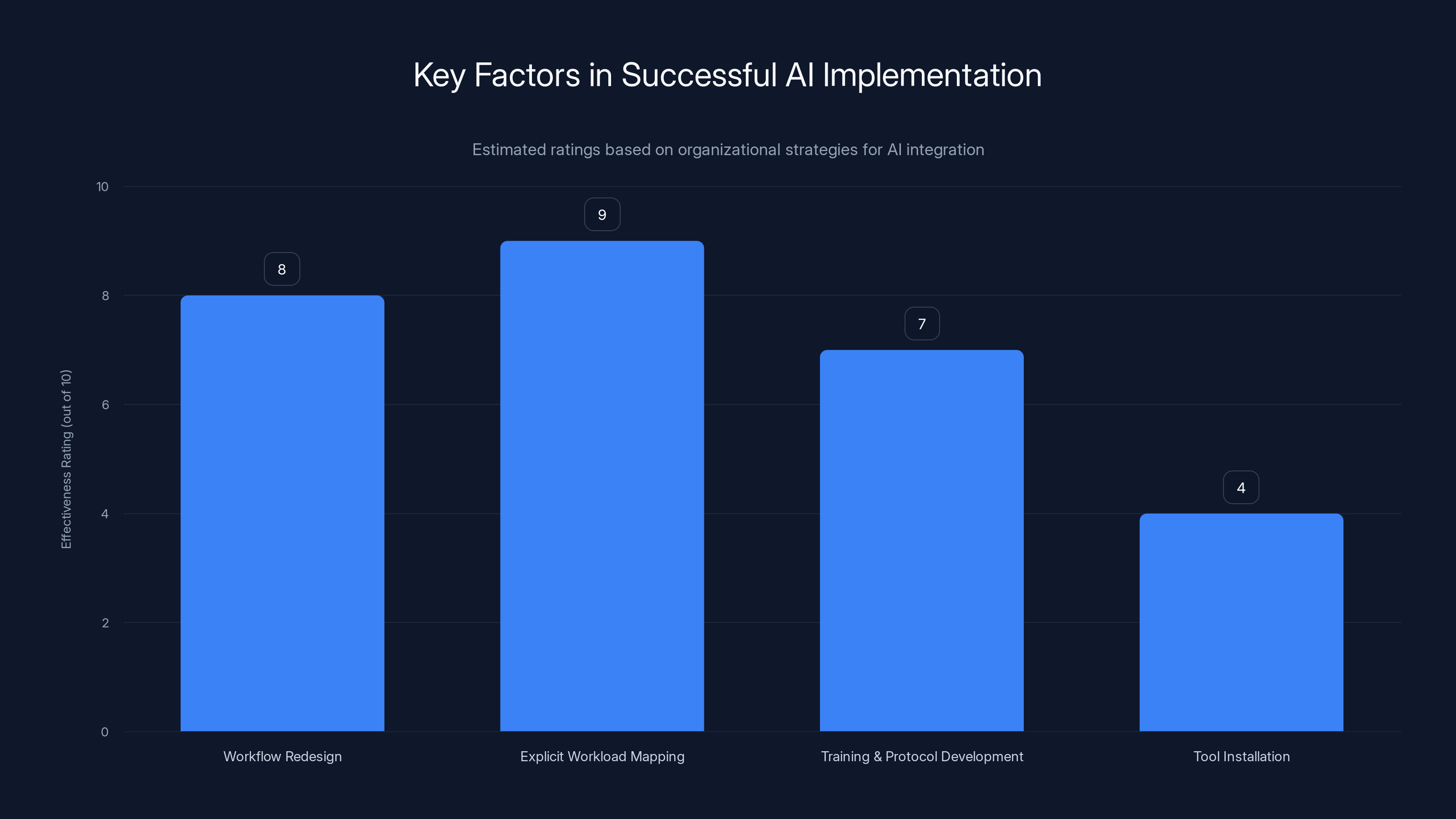

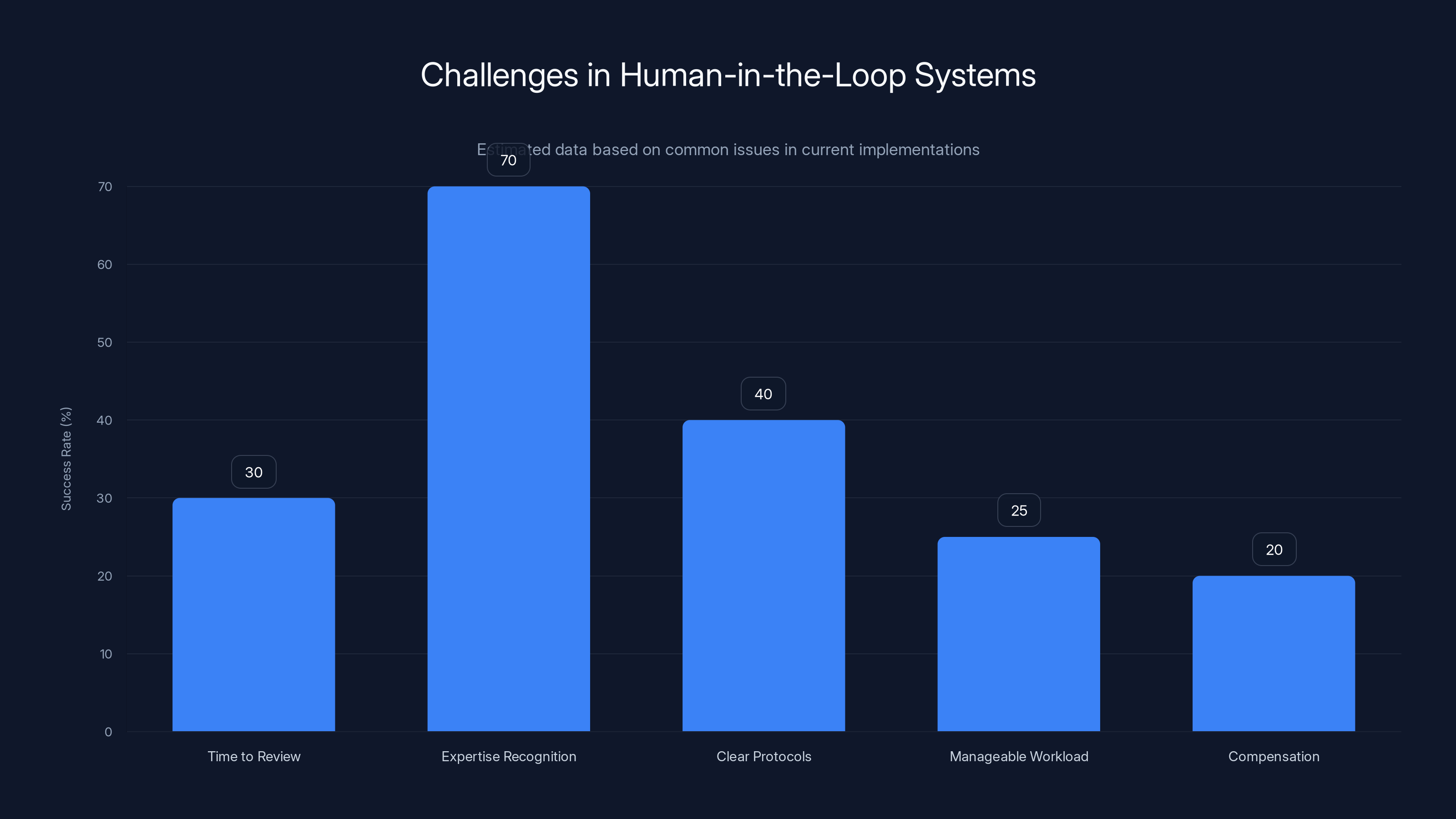

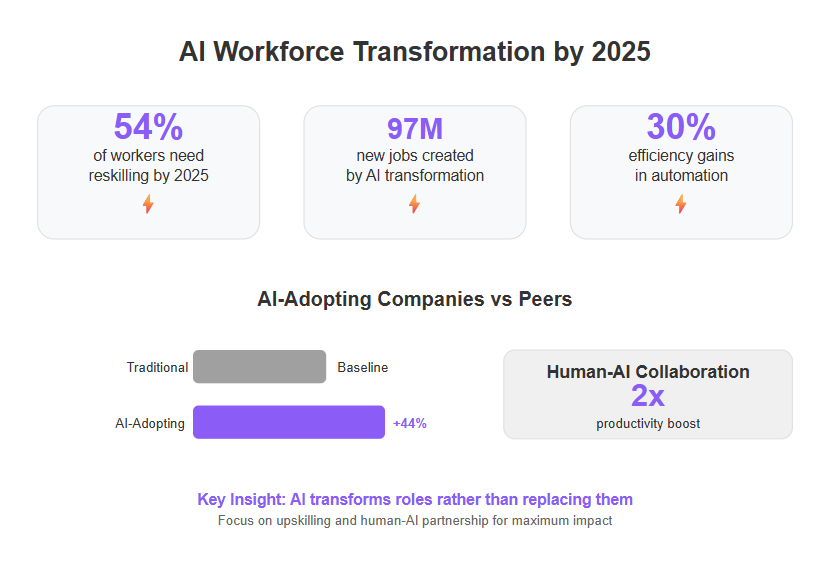

Workflow redesign and workload mapping are crucial for effective AI integration, while simple tool installation is less effective. Estimated data.

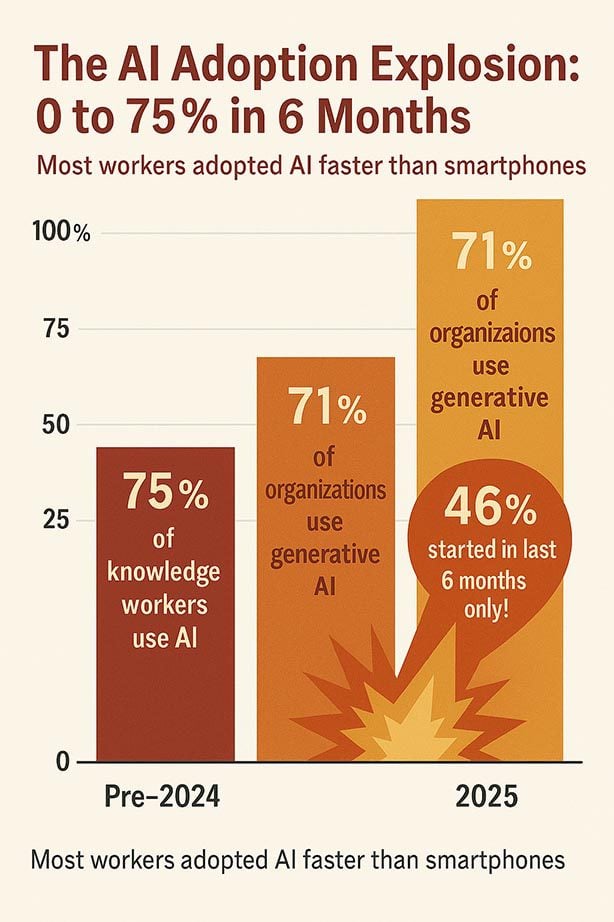

The Real AI Adoption Numbers: What Companies Won't Admit

Let's talk actual data, because the marketing numbers don't match reality.

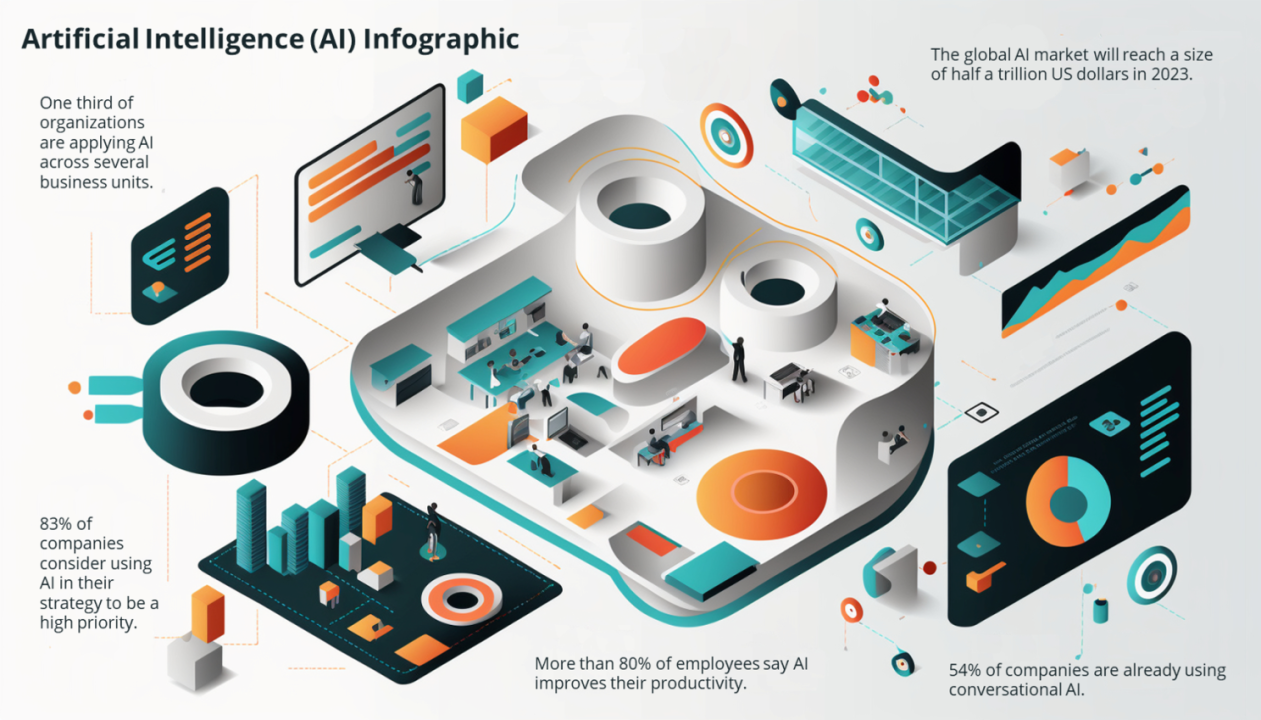

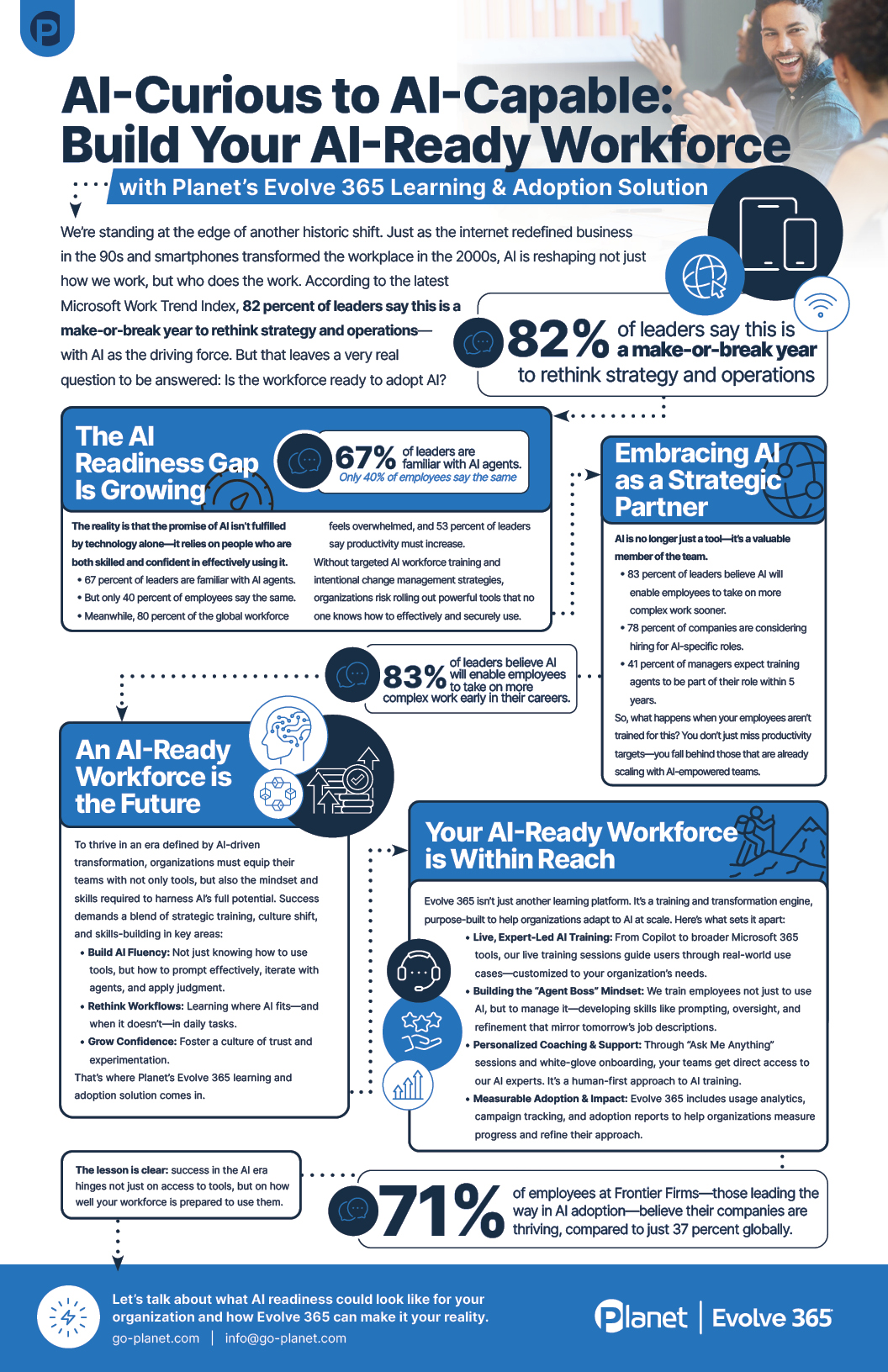

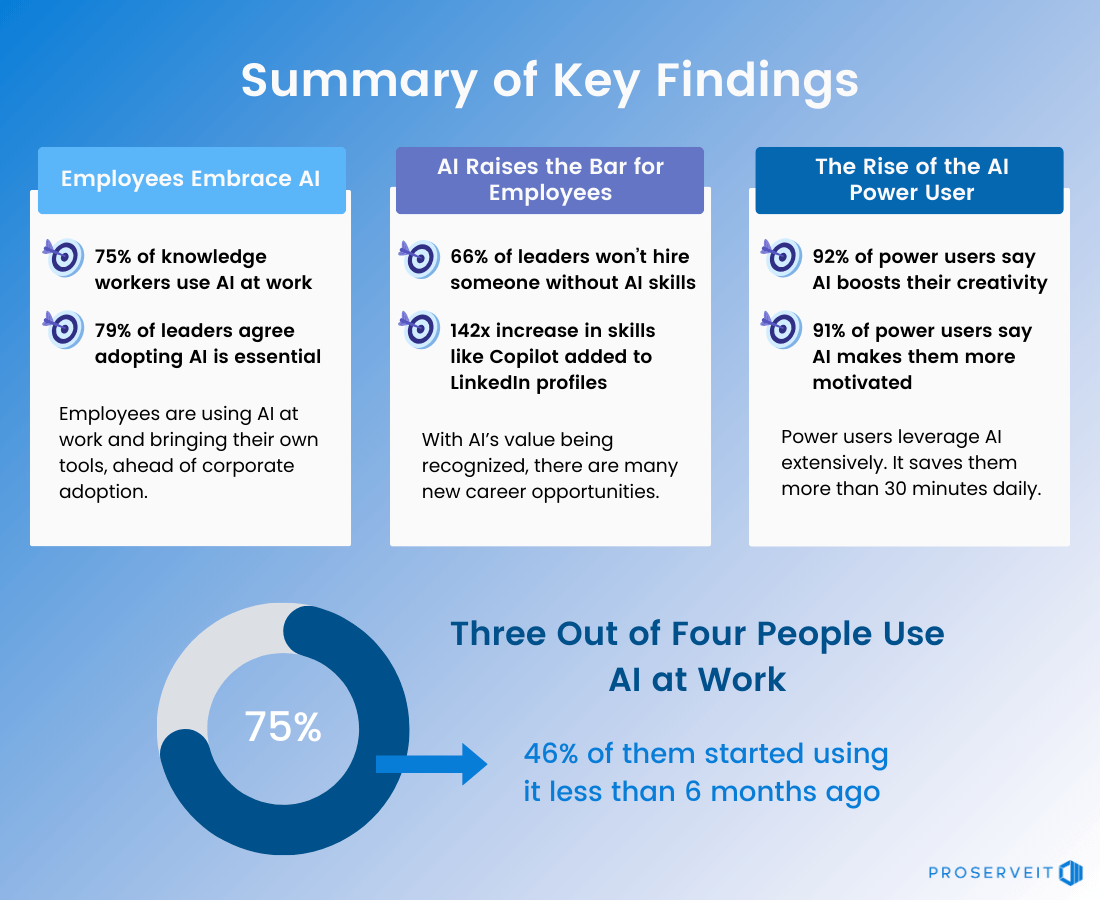

AI adoption is happening fast. We're seeing implementations across finance, healthcare, manufacturing, customer service, and knowledge work at unprecedented scale. Companies are shipping AI features monthly, sometimes weekly. Budgets are getting allocated. Teams are being formed. The momentum is real.

But here's what the adoption metrics don't show: how many of those implementations actually worked as intended.

Research from major tech organizations shows that roughly one-third of AI projects get abandoned or severely downscoped after initial deployment. Not because the AI isn't smart enough, but because the operational burden of keeping it functional exceeds the benefits. A single AI system might require 3-4 people to monitor, validate, and correct it continuously. That's not automation. That's shifting the work from machines to humans and calling it progress.

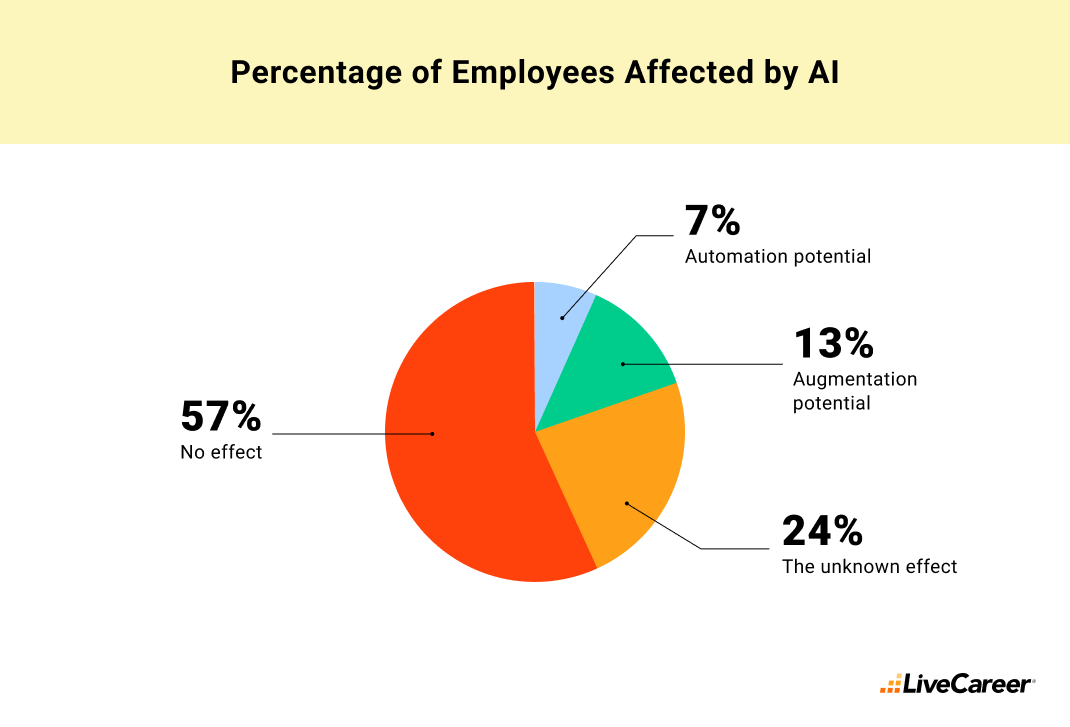

The occupational health research highlights something critical: when organizations implement AI without redesigning workflows, they don't reduce headcount. They redistribute it. Instead of 10 people doing work, you get 8 people doing the same work plus oversight. The 2 people theoretically freed up? They either don't exist (hiring freezes), or they get redeployed to maintain the AI system itself.

Separate studies from 2024 showed that workers using AI tools without proper training or clear protocols actually produce worse results than workers without AI access. The technology introduces friction. Employees spend time learning the tool, debugging outputs, reconciling differences between AI suggestions and domain knowledge, and managing false confidence in wrong answers.

One critical finding: AI doesn't just introduce hidden workloads. It introduces hidden complexity. A junior analyst working without AI needs to know their job reasonably well. An AI-assisted junior analyst needs to understand their job AND understand what the AI is doing AND understand where they diverge AND make judgment calls about which is right. That's not a simpler job. That's a harder job with a lower salary.

Regional data shows variation, but the pattern is consistent. Entry-level hiring has dropped significantly in AI-intensive roles. Mid-level positions are consolidating. Senior roles are getting more responsibility. Overall headcount in many organizations stays flat while output expectations climb.

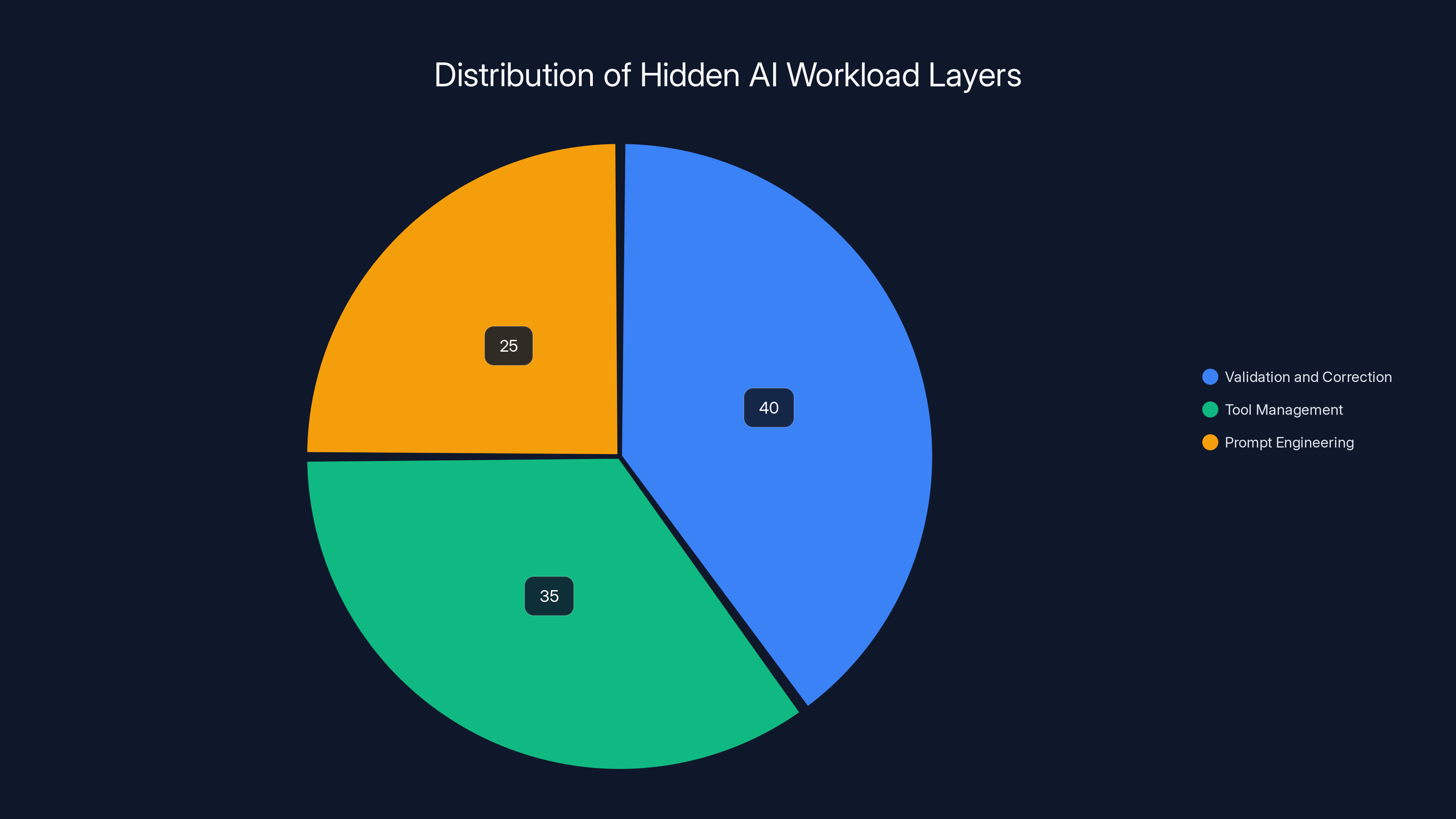

The Three Layers of Hidden Workload AI Creates

When people talk about AI workload, they usually mean one thing: humans checking AI output. That's real, but it's only the surface layer. The hidden workloads go much deeper.

Layer One: Validation and Correction Work

This is the most obvious. AI generates something. A human needs to verify it's correct. For simple tasks like summarizing an email, this is genuinely quick. For complex work like financial analysis, medical diagnosis, or legal document review, it's substantial.

The problem is that this validation work requires domain expertise. You can't just hire a cheap validator without deep knowledge. A radiologist still needs to review AI imaging analysis. An accountant still needs to check AI-generated financial reports. A lawyer still needs to validate AI contract summaries. You've automated the routine work but made the expert work harder because now the expert needs to catch both human errors AND AI errors (which have different patterns and are often more subtle).

A radiologist with AI assistance might review 50% more images per day, but those images now require more careful attention because AI can miss things humans catch easily, and vice versa. The net effect: harder, faster work without corresponding compensation.

Layer Two: Tool Management and Prompt Engineering

People don't realize this until they actually start using AI systems. Just getting good results requires skill. You need to phrase prompts correctly. You need to understand model limitations. You need to know when to use different tools for different tasks. You need to maintain institutional knowledge about what works and what doesn't.

This becomes somebody's job. Often it becomes everybody's job in an informal way, which means every team member is partially responsible for AI tool management without it being officially recognized.

Organizations that handle this well create prompt engineering roles or AI specialist positions. Organizations that don't handle it well end up with inconsistent results, frustrated employees, and AI systems that underperform not because the technology is bad, but because nobody knows how to use it properly.

The hidden workload here is invisible: time spent experimenting with prompts, documenting what works, training colleagues, troubleshooting why results changed, and adapting to model updates and changes.

Layer Three: Exception Handling and Decision-Making

AI systems work great in the normal cases. The hard part is everything outside normal. When do you override AI? When do you accept AI output despite your doubts? When do you escalate to a human expert? When do you flag unusual situations that break the model's assumptions?

These decisions used to be built into human expertise. Now they're meta-decisions: decisions about what to do with AI decisions. This adds a layer of cognitive load that doesn't show up in productivity metrics.

A customer service representative with AI assistance might handle 30% more tickets, but the tickets they handle now include deciding whether to accept the AI's suggested response, which response template to use, when to escalate rather than let AI handle it, and how to manage customer complaints about AI errors. The job got broader and more complex, not simpler.

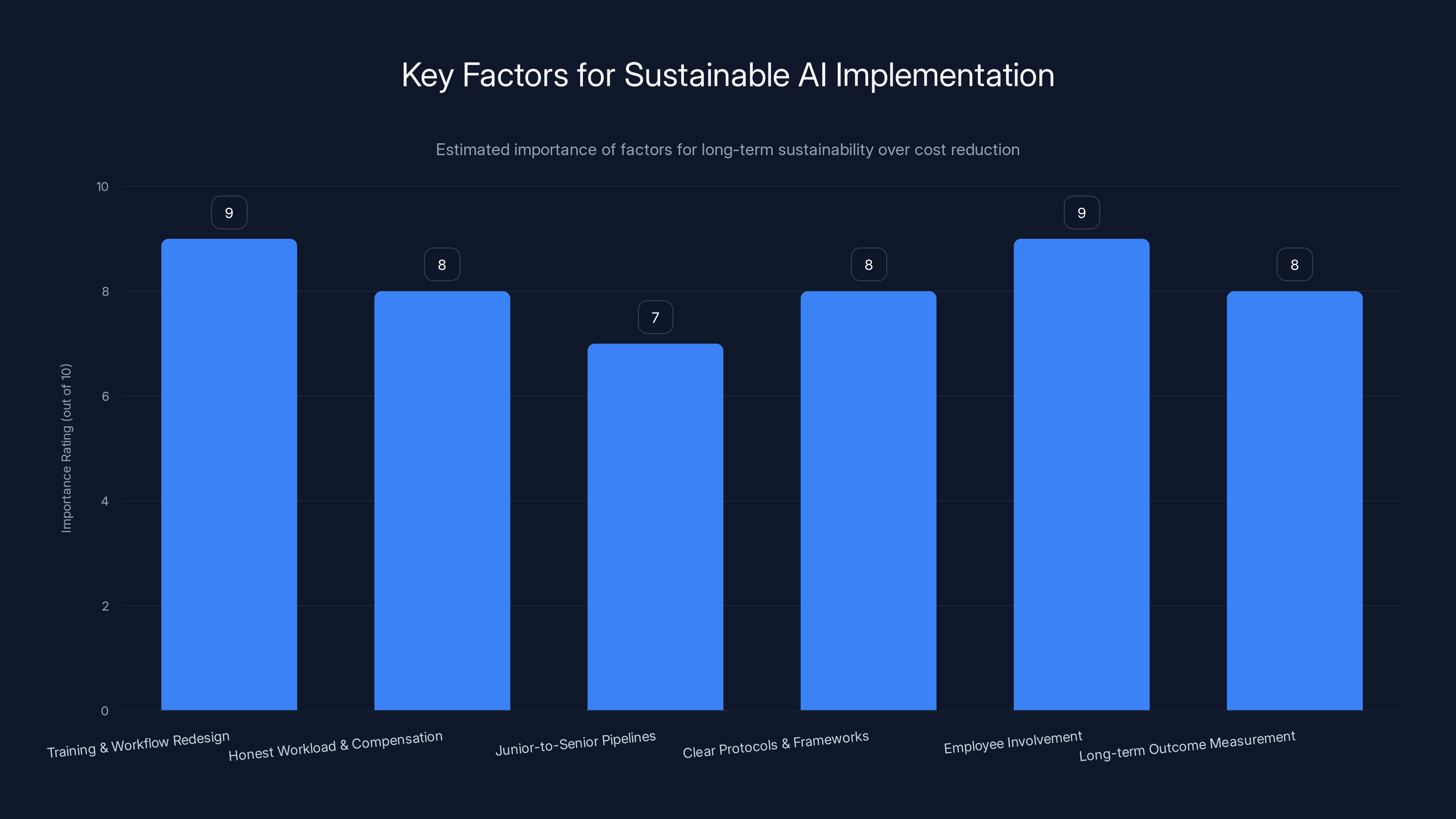

Investing in training, honest workload management, and employee involvement are crucial for sustainable AI implementation. Estimated data.

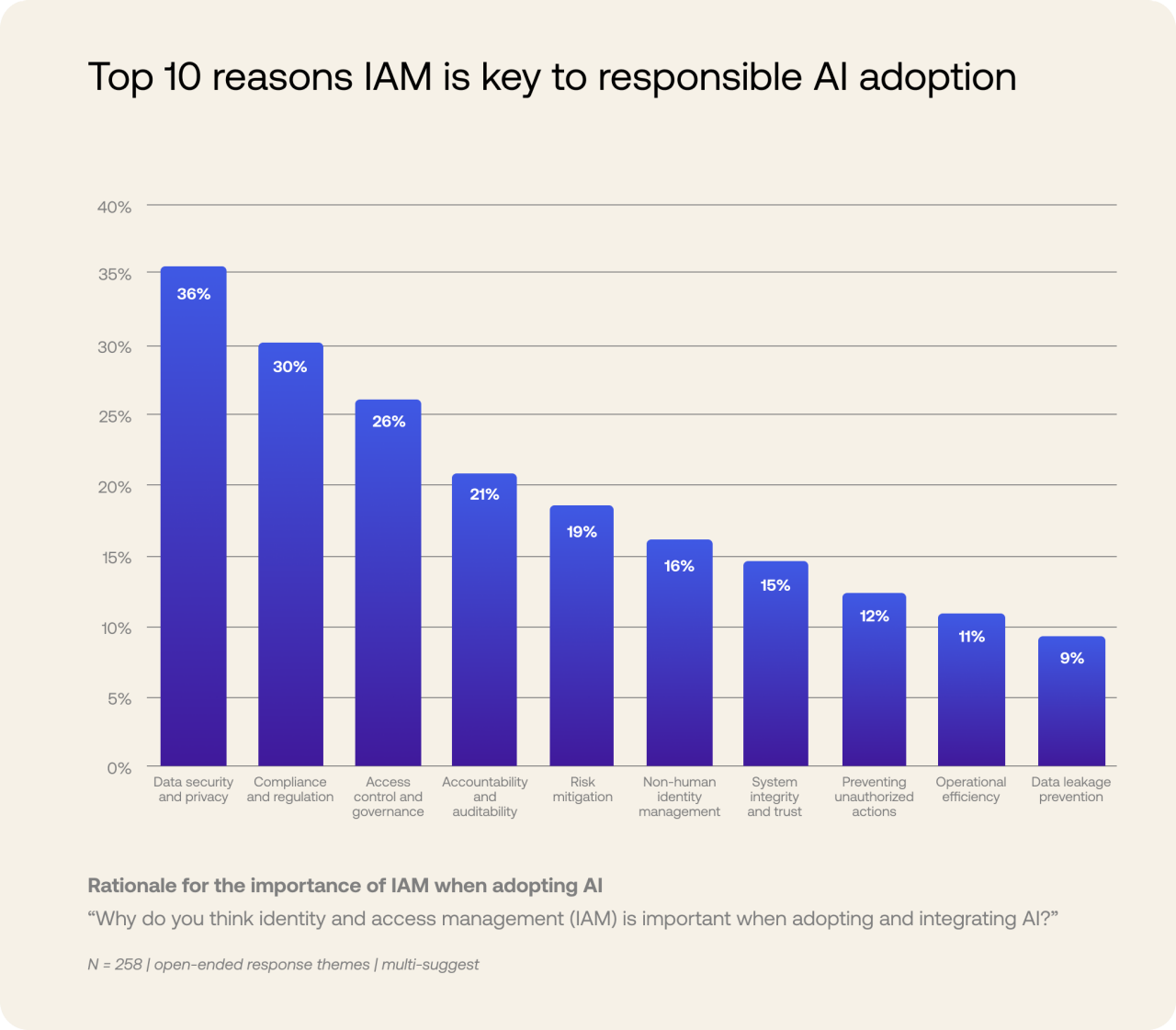

Why Organizations Misclassify Responsibilities When AI Enters the Picture

This is where things get economically interesting, and a bit dark.

When an organization adds AI to a role, managers face a perception choice. They can either:

- Recognize that the role changed and became more complex, therefore deserves higher compensation for the added cognitive burden and training requirements

- Frame the role as made easier by AI, therefore the compensation stays flat or decreases

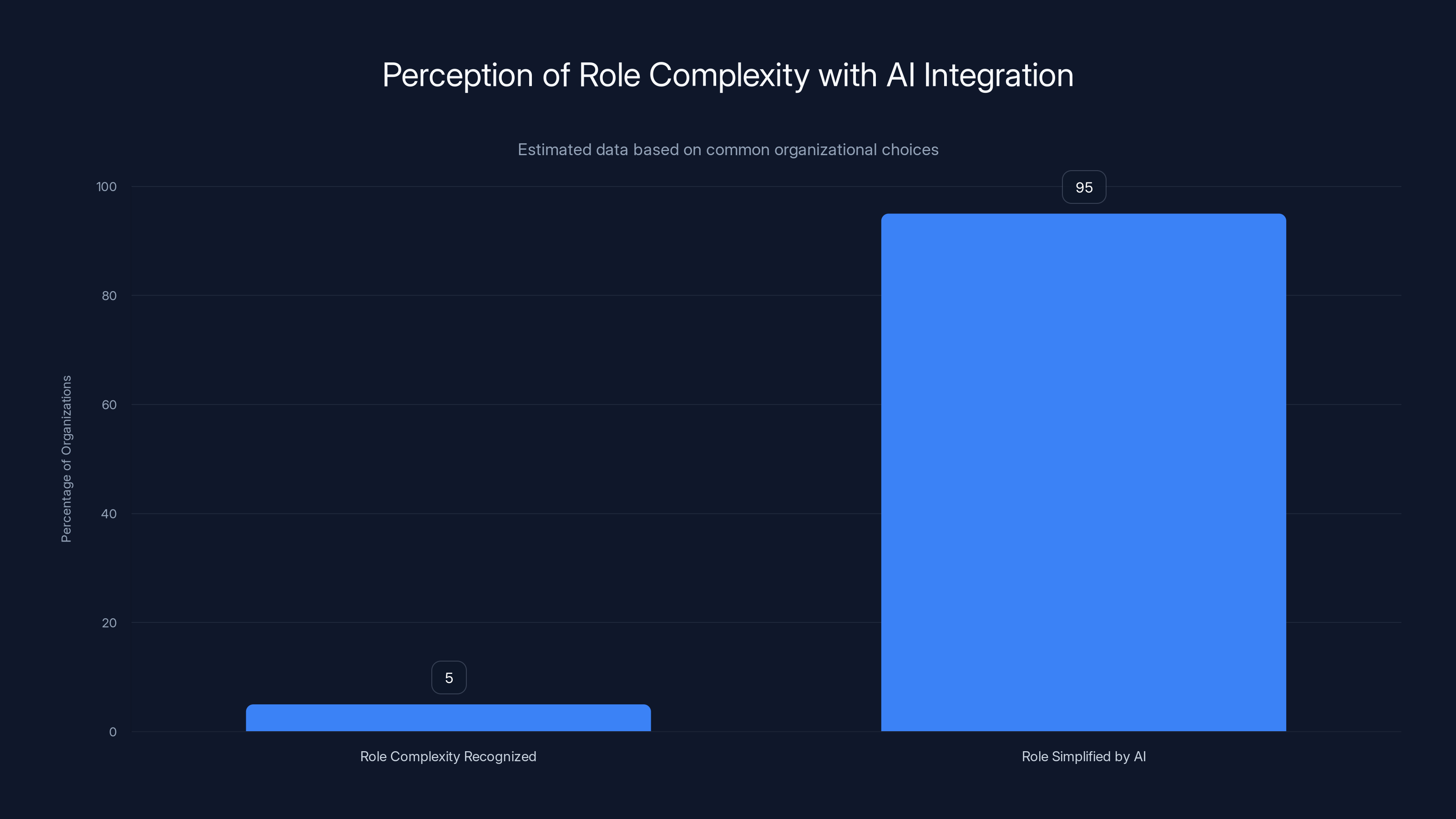

Guess which choice gets made 95% of the time?

The misclassification happens because of how management thinks about technology. Technology = cost savings. If we implement technology without reducing headcount, where are the savings? The only place to find them is compensation. If the role is now easier, the salary adjusts downward or sideways. If it's filled by someone externally, the hiring band drops.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Managers are incentivized to frame AI adoption as simplifying work because that's how they hit cost targets. At the same time, employees understand what's really happening. The job got harder, not easier. They're just not in a position to argue.

There's also the momentum of job market dynamics. If position X (AI-assisted analyst) suddenly starts paying 20% less because "AI handles most of the work," then that becomes the market rate. New hires negotiate based on that rate. External candidates expect that compensation. The downward pressure becomes systemic.

Meanwhile, the employees doing these jobs aren't stupid. They see what's happening. Either they absorb the stress, or they leave. Which means you get turnover in the exact positions where continuity matters most, because these are the people who actually understand how your AI systems are being used and where the gaps are.

The Youth Unemployment Connection: How AI Disrupts Entry-Level Pathways

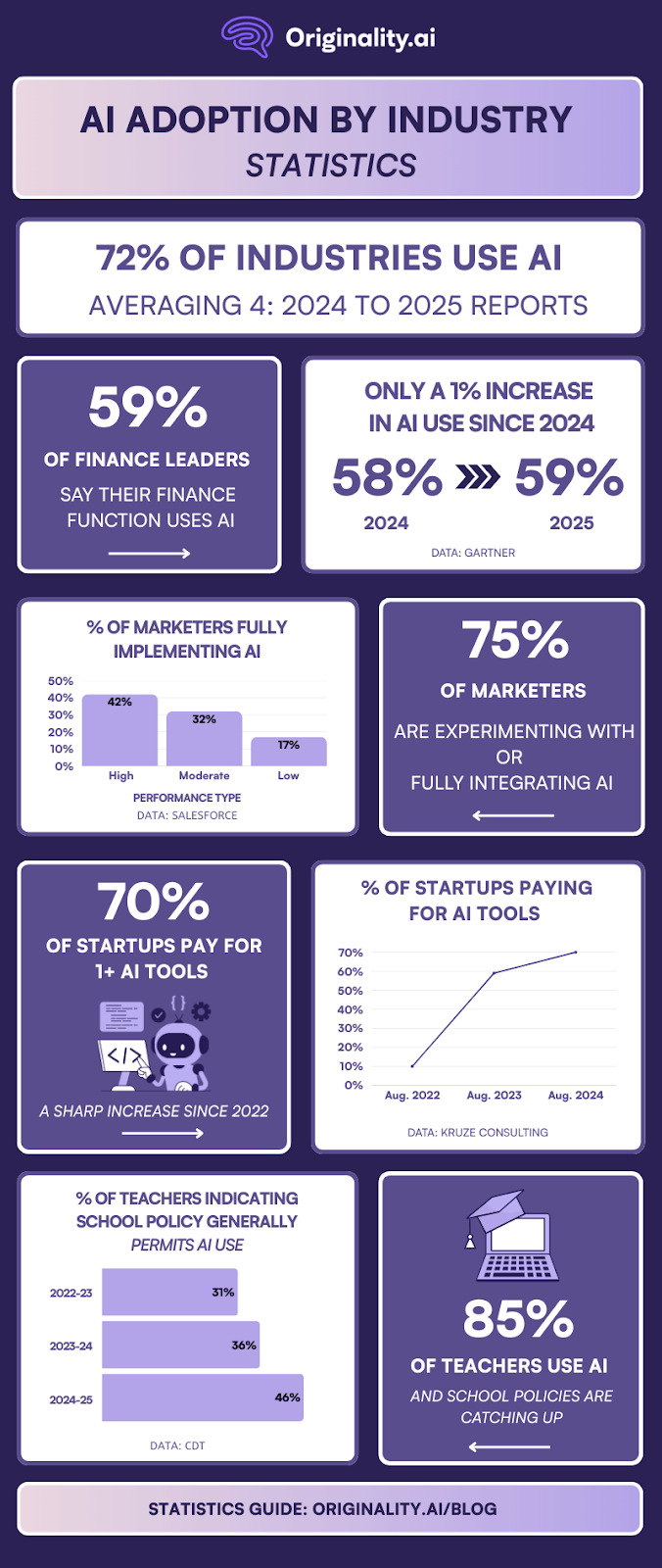

There's a secondary effect that's harder to see but more damaging long-term. Entry-level work is disappearing faster than mid-level work.

Historically, entry-level roles served as training grounds. You did routine, supervised work, learned the domain, built expertise, and gradually took on more complex responsibility. It was inefficient, but it worked.

AI is collapsing that pathway in many fields. Why hire a junior analyst to do routine analysis when you can hire a senior analyst and an AI system? The junior analyst position gets eliminated. The senior analyst supervises the AI and handles exceptions.

This creates a hidden unemployment crisis, particularly among younger workers. The data from the UK and US shows youth unemployment rising across sectors. Some of this is cyclical economic effects, but a growing portion is structural: there simply aren't entry-level positions to climb from anymore.

A young person trying to break into finance, law, accounting, customer service, or content work suddenly finds no entry point. They need experience. But there are no low-complexity positions where they can gain experience because those have been automated or merged with mid-level roles.

This is sustainable for corporations in the short term (lower costs, same output) but destructive for the economy long-term. You're essentially skipping a generation of skill development. The people who would have become the excellent mid-level and senior people in 2030 are instead unemployed or working in completely different fields in 2025.

The Stress Multiplier: How Combining Tasks Creates Disproportionate Pressure

There's a psychological component to this that matters more than people realize.

Adding one new responsibility to someone's job is manageable. Adding multiple new responsibilities while maintaining the same productivity expectations creates exponential stress, not linear stress.

When you introduce AI to a workflow, you're not adding one task. You're adding several:

- Learning the tool (ongoing, as features change)

- Validating AI output (task-dependent, could be 5-50% of work)

- Deciding on edge cases and exceptions (cognitive load, no clear answer)

- Maintaining prompt templates or parameters (institutional knowledge)

- Troubleshooting when results change (detective work)

- Training new team members on AI-assisted workflows (management load)

Each of these is relatively small. Together, they can easily add 30-40% to actual workload while creating a different type of pressure than the original work. The original work had clear expectations and evaluation criteria. AI work is ambiguous: how good is good enough? What's an acceptable error rate? When is human judgment better than AI judgment?

Employees aren't just doing more. They're doing more while being less certain about what success looks like. That's the kind of pressure that creates burnout faster than straightforward overwork.

The research specifically notes that without proper training and clear protocols, this pressure becomes unsustainable. Organizations that implement AI without investing in training, documentation, and clear decision frameworks end up with stressed employees and worse outcomes than organizations that treat AI implementation as a major change management initiative.

Research indicates that only 40% of AI projects are successfully implemented, while 30% are abandoned and another 30% are downscoped due to operational challenges. (Estimated data)

Job Redefinition vs. Job Displacement: The Subtle Difference That Matters

When people talk about AI and jobs, there's usually a binary discussion: will AI replace my job? But what we're actually seeing is more nuanced, and probably more problematic.

Job displacement (AI replacing humans) is visible. You lose a job, you seek a new one. It's painful, but it's clear what happened.

Job redefinition (AI changing what a job is) is invisible and insidious. You keep your job. But the job is now different. More responsibility, more complexity, different skills required. And nobody officially acknowledges that you've been reclassified into something harder.

The research shows that job redefinition is happening to significantly more workers than displacement. A company might eliminate one data entry role by automating it, but in the process, they're redefinining five analyst roles to include data entry oversight. Net result: job count stays flat, but the nature of work has shifted dramatically.

This redefinition is often presented as upskilling. "You're not just doing analysis anymore, you're managing AI analysis." Except that's not usually true. You're doing the same analysis plus managing AI, which means you're doing more, not something different.

The worst cases involve actual deskilling disguised as upskilling. A domain expert who previously made complex judgments now spends half their time correcting AI mistakes instead of doing what they were trained to do. They're technically still employed in the same role, but they're not actually doing that role anymore.

The Trust Paradox: Why Managers Favor AI Over People

Here's something the research uncovered that's particularly revealing: managers report trusting AI systems more than junior staff.

This isn't rational in most cases, but it's psychologically understandable. An AI system is predictable. It doesn't have bad days. It doesn't develop idiosyncratic preferences. It doesn't make judgment calls based on incomplete information and personal bias (well, it does, but in consistent, documentable ways).

A junior employee is unpredictable. They learn over time. They sometimes miss things. They need mentoring and correction. They require management attention.

When you have to choose between trusting an AI system or trusting a junior person, and you're evaluated on output metrics, the AI wins every time. Even if the AI is less accurate, it's more consistent and requires less overhead.

This creates a reinforcing cycle: junior roles get eliminated or downscaled because managers prefer AI. Junior people can't get the jobs they need to become senior people. Therefore, there are fewer senior people in the pipeline. Organizations end up with a hollowed-out middle of the organization: either entry-level contract workers and AI, or senior people managing systems.

The long-term problem is that this doesn't scale. AI catches edge cases that are outside its training distribution. Senior people can handle those. When you don't have enough senior people because you never developed a junior-to-senior pipeline, you have a problem. The AI fails on something novel, and there's nobody qualified to handle it.

This is why certain research suggests the current AI implementation approach is unsustainable. It looks like short-term cost savings but creates long-term capability gaps.

Sectoral Differences: Where AI Creates Worse Working Conditions

AI's impact on work isn't uniform. Some industries are handling it reasonably well. Others are creating genuinely exploitative conditions.

Knowledge Work (Finance, Legal, Consulting): These sectors are seeing significant role redefinition. Paralegals and junior analysts are being replaced by AI plus senior person oversight. The senior people are working harder than ever. Salaries for mid-level positions are stagnating or declining. This is probably the worst-hit sector in terms of hidden workloads.

Healthcare: Medical professionals are adding AI review duties to existing workloads. A radiologist or pathologist now needs to verify AI analysis before signing off. This increases accuracy but doesn't reduce work—it adds a layer of review. Some organizations are adjusting compensation; many aren't.

Customer Service and Support: This sector is split. Some organizations are using AI to augment human support (agents use AI suggestions) while maintaining quality standards. Others are deploying AI alone with minimal human oversight, which creates customer satisfaction issues that eventually require more human intervention than the original system. The worst outcomes happen when organizations reduce human staff while deploying AI that's not ready to operate independently.

Manufacturing and Operations: AI is actually improving working conditions in some manufacturing contexts. Predictive maintenance and optimization systems can reduce dangerous, repetitive work. But this only happens when organizations invest in worker retraining and transition support. When they don't, you get workers doing the same work plus AI monitoring, which increases stress without clear benefits.

Content Creation and Communications: This is becoming a mixed picture. Writers and designers are discovering that AI can accelerate some tasks (research, initial drafts, design comps) but also create additional review and quality control work. Salaries in these fields are being pressured by the perception that AI does the work now.

The pattern across sectors: AI creates value, but that value is being captured entirely by organizations, not shared with employees doing the work. Workers are doing more work with higher complexity and stress for the same or lower compensation.

Estimated data suggests that validation and correction work constitutes the largest portion of hidden AI workloads, followed by tool management and prompt engineering.

The Gap Between AI Promise and Implementation Reality

There's a massive gap between what AI is theoretically supposed to do and what it actually does in practice.

Theory: AI automates routine tasks, freeing humans for creative and strategic work.

Reality: AI creates new routine tasks (validation, correction, tool management) while humans still do creative and strategic work. Net result: humans do both.

Theory: AI increases productivity for everyone who uses it.

Reality: AI increases productivity for organizations that use it well with appropriate workflow redesign and training. AI decreases productivity for organizations that just drop the technology into existing workflows and expect people to figure it out.

Theory: AI handles the boring work, so employees have higher job satisfaction.

Reality: Employees have lower satisfaction because AI handles the predictable work they found fulfilling, while they're left with error correction and edge cases, which are frustrating and cognitively taxing.

Theory: AI levels the playing field for less experienced workers.

Reality: AI creates new barriers to entry because you need to understand both your domain and how the AI works, and you need to be good at catching AI errors, which requires expertise.

These gaps exist because implementations are being driven by cost reduction goals rather than productivity optimization goals. If the goal is to reduce headcount, you implement AI to eliminate jobs. If the goal is to improve productivity and quality, you implement AI to augment human capabilities, which is expensive, requires training, and doesn't reduce headcount.

Most organizations choose the first path because it's simpler to justify financially. That's the core problem.

The Sustainability Question: Can This Continue?

The research concludes with a question that keeps organizational leaders up at night: is this sustainable?

Short answer: No. Not in the current form.

If you implement AI in ways that make work worse for the people doing it, you create attrition. Good people leave. You get less experienced replacements. Quality degrades. You hire more AI to compensate. The cycle accelerates until something breaks.

This is exactly what we're seeing in some sectors now. Customer service organizations that deployed AI without human fallback are experiencing rising complaint rates and customer churn. Some are bringing humans back in, which means the AI saved nothing. Legal firms that cut junior positions to use AI are discovering they need junior people for exception handling, but nobody qualified is available, so they have to hire back at senior rates. Hospitals that added AI review without adjusting radiologist workload are experiencing radiologist burnout and departure, which makes AI critical again.

Sustainability requires intentional design. Organizations need to:

- Redesign workflows around AI capability, not just drop AI into existing workflows

- Explicitly map the hidden workloads that AI creates and plan for them

- Invest in training so employees understand both their domain and the technology

- Adjust compensation and evaluation metrics to reflect the new reality

- Create clear protocols for when to trust AI and when to override it

- Maintain a development pathway for junior people to become senior people (the most overlooked part)

Companies that are doing this well have better outcomes and lower attrition. They're investing more upfront but getting better long-term returns. Organizations just throwing AI at problems and hoping for savings are creating situations where the technology becomes a liability.

The research specifically calls for "finding routes to sharing learning." That means industries need to collectively figure out what works and what doesn't, and organizations need to share frameworks and lessons instead of each one fumbling through it independently.

Right now, most organizations are in the fumbling phase. That's why we're seeing these stress and compensation issues. As best practices emerge, we might see better implementation. But that requires deliberately prioritizing human sustainability in AI adoption, which currently isn't happening.

Structural Solutions: How Organizations Can Actually Implement AI Well

If the problem is that AI creates hidden workloads and unsustainable working conditions, what's the actual solution? It's not "don't use AI." It's "use AI differently."

Workflow Redesign, Not Tool Installation

The worst implementations treat AI as a tool to install in existing workflows. "We're adding this AI assistant to your team. Use it if you want." That's how you get hidden workloads.

Good implementations redesign the entire workflow around the AI capability. You're not adding AI to an analyst role. You're redesigning what an analyst does when they have AI access. Maybe they do less validation and more interpretation. Maybe they do less data collection and more strategy. Maybe the role splits into different positions: someone who prompts the AI and validates it, someone who interprets results, someone who handles exceptions.

This takes time and costs money upfront. It also requires being honest about what work is actually disappearing versus what work is changing. Once you're honest about that, you can design transitions that don't destroy careers.

Explicit Workload Mapping and Adjustment

Before implementing AI, map the actual work: hours per task, frequency, required expertise, error rate, downstream impact. Then implement the AI and map the new work: validation time, exception handling, tool management, learning curves.

Compare them honestly. If the same person is doing both the new work and the old work, that's not automation. That's adding a job. Pay accordingly, or redesign the role to drop something that's truly automated.

This requires measuring things that organizations often don't measure: time spent on validating AI output, time spent on exceptions and corrections, time spent on tool maintenance. Once you measure it, you can't ignore it.

Investment in Training and Protocol Development

AI doesn't work well without clear protocols about when to trust it, when to override it, when to escalate, and when to use different approaches. Developing these protocols requires domain experts working with AI engineers, testing, iterating, and documenting.

This is expensive. It's also absolutely necessary. Organizations that skip it are essentially asking employees to figure out AI on the job, which creates stress and inconsistent results.

Compensation Adjustment Models

Here's what few organizations do: explicitly acknowledge that a role has changed and adjust compensation. "This role now includes AI management responsibilities. Based on the workload analysis, we're adjusting the salary range up by 15% and providing training for the new skills required."

Instead, most organizations quietly downgrade the compensation because the role seems "easier." The result is a job that's actually harder, but pays less, with worse conditions. That's not a path to retention.

Maintaining Development Pathways

The most overlooked solution: keep hiring junior people, keep training them, and keep creating growth pathways. Don't let the organization hollowed out in the middle with AI at the junior level and humans at the senior level.

This means some roles that could be fully automated stay partially staffed because they're training grounds. It means accepting that junior people are less efficient than AI. It means investing in developing the next generation of domain experts who understand both the field and how AI fits into it.

Organizations that do this have better long-term outcomes because they have a pipeline of people who can handle exceptions, innovate, and adapt when technology changes.

95% of organizations tend to frame AI integration as simplifying roles, which often leads to stagnant or reduced compensation. Estimated data.

What Workers Actually Need: The Overlooked Solutions

Most research on AI and work focuses on what organizations should do. Less focuses on what workers actually need.

Workers need transparency. They need to know whether they're being asked to do the same job with AI assistance, or whether the job has changed. They need clarity on what's expected and how they'll be evaluated.

Workers need training. They need to understand the AI they're using, its capabilities and limitations, and when to trust it. This isn't optional. Without training, people make worse decisions and feel more stress.

Workers need voice. They need mechanisms to flag that workloads are unsustainable, that protocols aren't working, that quality is degrading. Organizations that ignore employee feedback about AI implementation end up with worse outcomes and higher turnover.

Workers need compensation adjustment. If the job changed, the compensation should change. If workloads increased, compensation should increase. This doesn't happen automatically; employees need to advocate for it.

Workers need job security. This is where the research gets dark. Right now, workers understand that advocating for themselves around AI could be seen as resistance to automation, which could make them seem like a liability. They need explicit protection: policies that say raising concerns about workload, safety, or quality won't result in being made redundant.

Without these things, you get what we're seeing: workers absorbing stress, managers implementing cost-cutting measures that look like productivity gains, and systems that work for short-term financial goals but fail at long-term sustainability.

Industry-Specific Predictions: Where This Gets Worse Before It Gets Better

Based on current trajectories, certain sectors are going to experience severe AI-related work disruption before implementing better practices.

Knowledge Work Professions (Law, Finance, Accounting, Consulting): These will probably get worse before better. There's extreme pressure to reduce junior roles, which will create skill gaps. Eventually, when junior people can't be developed, senior people will become scarce and expensive, which will create demand to develop juniors again. But between now and then, there's going to be career disruption for people in their 20s and early 30s trying to break in.

Healthcare: Imaging specialties (radiology, pathology) will likely move toward the AI-plus-senior-expert model within 5 years. Clinical medicine will take longer because the variability and exception handling is harder. Nurses and support staff might actually benefit from AI because it could reduce some of the task-switching and routine work that currently causes burnout.

Customer Service: This will bifurcate. Organizations that invest in quality AI will reduce human needs. Organizations that deploy cheap AI will eventually bring humans back in because customers hate interacting with bad AI. The net effect: reduced employment, but better-paid remaining positions.

Creative Fields: This is the wildcard. Right now, AI is replacing entry-level creative work (junior copywriting, graphic design templates, stock content). But demand for high-quality creative work hasn't declined; if anything, it's increased because there's more content. So you might see fewer junior copywriters and designers, but same or more demand for senior creative directors. The pathway from junior to senior becomes shorter and more competitive.

Skilled Trades: These are more AI-resistant than people think. Plumbing, electrical work, construction, skilled manufacturing—these have high variability and physical components that AI can't automate. But they can be augmented with AI. A technician with AI diagnostic support can probably work faster and with fewer errors. If organizations adjust compensation accordingly, these could actually be improved by AI rather than threatened.

The common pattern: sectors with clear escalation pathways and willingness to invest in training will adapt well. Sectors that try to avoid junior hiring and hope AI fills the gap will experience skill crises within 5-10 years.

The Case for Intentional Design: Success Stories and Counterexamples

There are organizations implementing AI well, and they're getting better results than the average.

The common traits: they're treating AI implementation as a strategic change, not a tool deployment. They're investing in training before implementation, not after. They're honest about workload impacts and adjusting compensation accordingly. They're maintaining junior-to-senior pipelines. They're creating clear decision protocols instead of expecting people to figure it out.

The results are measurable: lower attrition, higher quality output, employees who trust the technology, and better ability to adapt when the technology changes.

Counterexamples are visible too. Organizations that deploy AI and immediately cut junior staff, then wonder why they have a crisis when the AI malfunctions. Organizations that don't train employees, then blame them for poor AI results. Organizations that increase workload while reducing compensation, then are shocked when their best people leave.

The research points toward a fundamental truth: AI adoption outcomes depend far more on implementation approach than on the technology itself. The same AI system creates better conditions in one organization and worse conditions in another, based on how it's integrated.

This means the solution to the "workers face complex responsibilities for lower pay" problem isn't to reject AI. It's to demand better implementation.

Current human-in-the-loop systems often fail in providing manageable workloads and adequate compensation, with only 20-40% success in these areas. Estimated data.

The Sustainability Framework: What Long-Term AI Integration Requires

The research concludes with a call for sustainable AI integration. What does that actually look like?

Phase One: Assessment (Before Implementation)

- Map current work and required expertise

- Model AI capability and where it actually helps

- Identify hidden workloads AI will create

- Calculate true cost of implementation (including training, workflow redesign, workload management)

- Set honest expectations about timeline to productivity gains

Phase Two: Redesign (Before Implementation)

- Redesign workflows around AI, not fitting AI into existing workflows

- Create decision protocols for when to trust AI, when to override, when to escalate

- Identify which roles change and how

- Plan compensation and job title adjustments

- Plan training programs

- Maintain commitments to junior hiring and development

Phase Three: Implementation (During Implementation)

- Train thoroughly before deployment, not after

- Monitor workload closely in the first weeks and months

- Adjust protocols based on what actually happens

- Collect feedback from employees doing the work

- Adjust compensation if workload is higher than planned

- Maintain management attention; don't treat AI as self-managing

Phase Four: Optimization (After Implementation)

- Measure actual workload impact against projections

- Adjust roles, responsibilities, and compensation based on reality

- Share learning with rest of organization and industry

- Plan for next iteration

- Monitor employee wellbeing and attrition

Most organizations are skipping phases one and two, doing a half-implemented phase three, and never reaching phase four. That's why they're creating the problems the research describes.

Sustainability requires patience and investment. It also requires honesty about what's actually happening, which is the biggest obstacle because organizations are heavily incentivized to present AI adoption as purely cost-saving, not cost-shifting.

The Human-in-the-Loop Reality: Designing Systems That Actually Work

There's a concept in AI called "human-in-the-loop"—systems where humans and AI work together with humans making final decisions. This is theoretically optimal, but it's also where we're seeing the worst hidden workload problems.

Human-in-the-loop only works if:

- The human has time to actually review and make decisions

- The human has expertise to recognize when AI is wrong

- The human has clear protocols for what to do

- The human workload is manageable alongside other duties

- The human is compensated for this responsibility

Right now, most human-in-the-loop systems fail criteria 1, 4, and 5. You have humans in the loop, but they're overloaded, they're doing it without clear protocols, and nobody's paying them for it.

The research specifically highlights this: the way human-in-the-loop is currently being implemented is creating worse outcomes than either full AI automation (which fails on exceptions) or full human control (which is slow).

What would actually work: organizations would need to either:

- Hire enough people to actually do human oversight with time to think (expensive, defeats the purpose of AI for cost reduction)

- Or develop AI systems that are good enough to require minimal human oversight (expensive, requires better training data and more development)

- Or clearly define what human-in-the-loop means for each decision: maybe it's 100% of decisions, maybe it's 5%, maybe it's "call a human if this situation looks unusual"

Instead, organizations are vague about what human-in-the-loop means, which leaves employees making it up as they go, creating massive stress and inconsistent results.

Future of Work: Where This Needs to Go

The research doesn't offer crystal ball predictions, but it does suggest directions that could lead to better outcomes.

One path: AI becomes genuinely autonomous in specific domains, removing the human-in-the-loop bottleneck entirely. This is the Silicon Valley narrative. It's possible, but it requires far better AI than currently exists and far better problem definition than currently happens.

More likely path: AI becomes augmentation that works well enough that humans can supervise multiple systems instead of being tied to one. A radiologist might review AI-flagged images instead of reading every image, which is actually more sustainable than adding AI review duties to existing reading duties.

Another path: jobs reorganize around human-AI partnerships with different role definition. Instead of a radiologist+AI, you get an AI interpreter (someone who understands medical imaging and AI) and an AI trainer (someone who improves the models with feedback). These are new roles, not modifications of existing ones.

The research suggests the most sustainable path requires acknowledging that humans and AI have different strengths, and designing systems that leverage both rather than trying to optimize AI upward while humans absorb the gaps.

Right now we're in a transitional phase where organizations are discovering that the cost-cutting approach to AI implementation doesn't work sustainably. Over the next 3-5 years, we'll probably see consolidation around approaches that actually do work, with significant disruption for workers and organizations in between.

Actionable Takeaways: What Workers and Organizations Should Do

If you're a worker in an AI-integrated role right now, what should you do?

Document everything. Track your actual workload before and after AI implementation. How much time validating? Correcting? Learning? Maintaining? This documentation is powerful when compensation or workload conversations happen.

Understand the AI you're using. This isn't optional. You need to know its capabilities and limitations so you can catch errors and use it effectively. Don't expect the organization to train you; do it yourself if necessary.

Flag unsustainable conditions clearly. Don't accept the premise that you should just work harder. When workload becomes unsustainable, say so explicitly. Provide data. Suggest solutions.

Build irreplaceable skills. Focus on things AI can't do: complex judgment, relationships, understanding nuance, handling exceptions. These become more valuable as AI takes on routine work.

If you're an organization implementing AI, the path is clearer:

Invest in the implementation. The temptation is to deploy AI and expect people to figure it out. Resist this. Training, workflow redesign, and workload management are non-negotiable.

Be honest about what work changes. If a role becomes harder and more complex, acknowledge it and pay accordingly. If work truly disappears, handle the transition deliberately.

Keep development pathways. Even if AI could replace junior staff, don't do it. The cost of reattracting capable people later is higher than the cost of developing them now.

Measure what matters. Track not just productivity metrics, but workload, quality, employee satisfaction, and turnover. These tell you whether your implementation is actually working.

Share learning. The organizations figuring this out are doing themselves and the industry a disservice by keeping it secret. This problem affects everyone; solutions should be shared.

Conclusion: Sustainability Over Cost Reduction

The research uncovered a fundamental contradiction in how AI is being implemented: we're optimizing for short-term cost reduction at the expense of long-term sustainability.

It looks smart in the spreadsheet. Implement AI, reduce headcount or hold it flat while output increases, capture the difference as margin. Except it doesn't work that way in reality.

What actually happens: you increase workload, increase complexity, decrease compensation, increase stress. People leave. Quality declines. You have to hire back at higher rates or deploy more AI that requires more management. The cost savings disappear, and now you're operating a worse system with less experienced people.

Sustainability requires a different approach: optimize for long-term productivity and quality, with cost reduction as a side effect rather than the goal.

This means:

- Investing in training and workflow redesign before deployment

- Being honest about workload and compensating accordingly

- Maintaining junior-to-senior pipelines even if it costs more short-term

- Creating clear protocols and decision frameworks

- Involving employees in optimization rather than dictating it

- Measuring long-term outcomes, not just implementation metrics

The organizations that do this will have significant competitive advantages: better employee retention, higher quality output, better ability to adapt as technology changes, and more sustainable growth.

The organizations that pursue cost reduction through AI will experience periodic crises where the technology fails without people to handle it, or turnover so severe that they lose critical knowledge.

The research is essentially calling for the industry to choose sustainability. Whether that happens depends on whether executives prioritize long-term organizational health over short-term financial targets. Based on current trends, that's not happening voluntarily, which suggests regulatory pressure or market consequences might be necessary to force the change.

For now, the responsibility falls on individual organizations to decide: do we implement AI in ways that work sustainably, or do we implement AI in ways that look good on paper while creating hidden costs and problems? The research makes clear that the easy choice isn't actually easier; it just hides the problems until they become crises.

FAQ

What does "hidden workload" mean in the context of AI at work?

Hidden workload refers to tasks that emerge when AI is integrated into workflows but aren't officially recognized or compensated. These include validating AI output, correcting errors, deciding when to override AI decisions, maintaining prompt templates, troubleshooting, and training colleagues. They're called hidden because they're not in job descriptions and management often doesn't account for them when calculating productivity gains.

Why do organizations reduce compensation for roles that become AI-assisted instead of recognizing increased complexity?

Organizations face pressure to quantify cost savings from AI investments. If a role appears easier because AI handles routine work, compensation gets downgraded to achieve cost reduction targets. This ignores that the role often becomes more complex, requiring oversight and judgment. The misclassification happens because cost reduction metrics are simpler to track than actual workload impact, and managers are incentivized to hit cost targets more than to fairly compensate employees for changed roles.

How does AI adoption affect entry-level employment differently than mid-level or senior employment?

Entry-level positions are disappearing faster than other roles because AI can handle routine junior-level work. This eliminates the training ground where people build expertise to advance. Organizations hire experienced professionals to supervise AI instead of developing juniors, creating a structural barrier for people trying to break into fields. This contributes to rising youth unemployment in sectors with rapid AI adoption, as there's no pathway for newcomers to gain foundational experience.

What's the difference between job displacement and job redefinition, and why does it matter?

Job displacement means losing your position entirely; you must find new work. Job redefinition means keeping your position but the nature of the work changes significantly—usually becoming more complex and demanding while compensation stays flat or decreases. Redefinition is more common with AI but less visible, so workers don't realize their role has effectively become harder without corresponding benefits. This creates unsustainable pressure without the clarity that comes from outright job loss.

How can organizations implement AI sustainably without creating hidden workloads?

Sustainable implementation requires redesigning workflows around AI (not fitting AI into existing workflows), explicitly mapping workload impacts before and after, investing in training and clear protocols, adjusting compensation for changed roles, maintaining junior hiring and development pathways, and measuring actual outcomes rather than just productivity metrics. It's more expensive upfront but prevents the attrition, quality decline, and crises that occur when AI is deployed without these foundations.

What should a worker do if they're experiencing unsustainable workload after AI implementation?

Document your actual workload with time tracking before and after implementation. Understand the AI system you're using, including its limitations. Flag unsustainable conditions with data and specific examples rather than complaints. Request appropriate compensation adjustment if workload increased. Focus on building skills AI can't replicate: judgment, relationships, exception handling. Consider whether the organization is willing to address the problem sustainably, as some organizations won't change without external pressure.

Is the research suggesting AI should be rejected, or that implementation needs to change?

The research isn't anti-AI; it's anti-unsustainable-implementation. AI creates real value and productivity benefits. The problem is how organizations are deploying it, optimizing for short-term cost reduction while ignoring long-term impacts on employee sustainability, skill development, and organizational capability. Better implementation approaches exist and are being used by some organizations successfully. The research calls for industry-wide adoption of these sustainable practices rather than rejection of the technology.

How does this relate to the "human-in-the-loop" AI concept?

Human-in-the-loop is theoretically ideal: humans make final decisions, AI provides suggestions. In practice, it creates the worst conditions when humans are overloaded, lack clear protocols, don't have time to actually review AI output, and aren't compensated for oversight work. Sustainable human-in-the-loop requires either hiring enough people to actually do meaningful oversight, or developing AI that's autonomous enough to require minimal human intervention. Most current implementations do neither, just adding oversight duties to existing workloads.

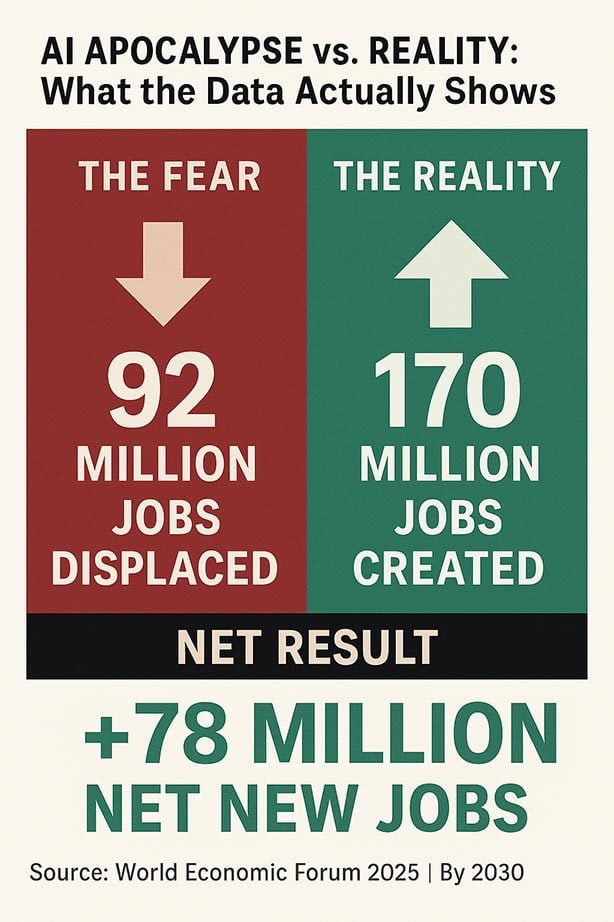

What does the data show about how AI adoption is affecting global employment patterns?

Data from the UK and US shows youth unemployment rising while overall employment stays relatively stable, suggesting structural displacement of entry-level work. Mid-level positions are consolidating faster than senior roles, creating an hourglass employment distribution. Regional variation exists but the pattern is consistent: automation is specifically targeting junior-level work, disrupting the career development pathways that historically moved workers from entry to senior positions. This creates both immediate unemployment and long-term skill development crises.

What can executives and organizational leaders do right now to prevent AI-related work problems?

Leaders should pause the cost-cutting focus and ask explicitly: "What are we trying to accomplish with AI?" If it's purely cost reduction, the implementation will likely create hidden problems. If it's productivity and quality improvement, that requires different decisions: training investment, workflow redesign, compensation adjustment, maintaining junior hiring, measuring actual workload impact. Leaders should also mandate that workload analysis happens before and after implementation, and that employee feedback is actively solicited and addressed. The best outcomes come from treating AI implementation as a strategic change initiative, not a cost-reduction tool deployment.

Key Takeaways

- AI creates hidden workloads through validation, tool management, and exception handling that aren't officially recognized or compensated

- Roles perceived as easier due to AI receive stagnant or declining salary adjustments despite increased complexity and cognitive load

- Entry-level positions are disappearing faster than other roles, disrupting career pathways and contributing to youth unemployment in AI-intensive sectors

- Organizations implementing AI without workflow redesign, training, and compensation adjustment experience higher attrition and worse long-term outcomes

- Sustainable AI adoption requires intentional design phases including assessment, redesign, training, and ongoing workload management rather than simple tool deployment

![AI at Work: Why Workers Face More Responsibilities Without Higher Pay [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-at-work-why-workers-face-more-responsibilities-without-hi/image-1-1767722898147.jpg)