AI Funding Mega-Rounds 2025: Anthropic's $350B Valuation, Open AI's Existential Risks, and Why Venture Capital Math is Fundamentally Changing

Introduction: The AI Gold Rush That's Reshaping Silicon Valley

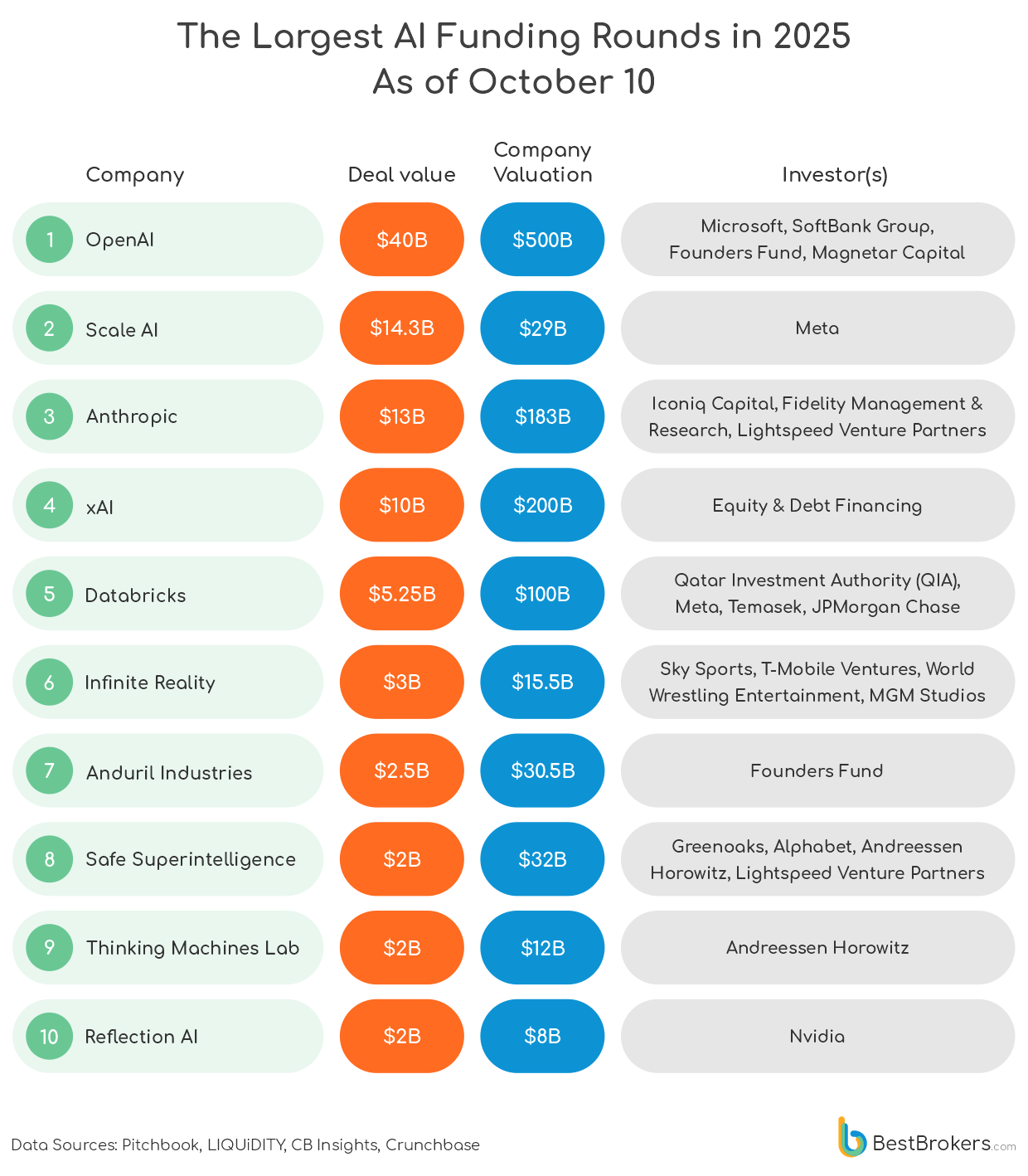

We've entered a new era of venture capital. The numbers are staggering, the valuations are stratospheric, and the implications are profound. In early 2025, Anthropic closed a

But here's what most tech commentators are missing: many of these valuations aren't actually as crazy as they sound. When you run the fundamental math—examining revenue multiples, growth rates, and market TAM—some of these companies are trading at valuations comparable to established SaaS darlings. Others reveal genuine existential risks to household names. And some represent bets on markets so large that even "expensive" appears like a bargain.

This comprehensive analysis examines the three biggest stories dominating AI funding conversations: Anthropic's valuation mathematics and enterprise dominance, Open AI's surprisingly precarious competitive position, the future of mega-funds and venture capital concentration, and what California's proposed wealth tax means for founder relocation and innovation centers. We'll dig into the underlying metrics, explore the game theory at play, and help you understand why the AI funding landscape of 2025 represents a genuine inflection point—not just for technology, but for how capital allocation itself works.

The stakes are higher than most realize. The companies winning this moment will define the next decade of computing. The investors funding them are placing trillion-dollar bets. And the venture capitalists who misread this moment will be explaining themselves to LPs for years to come.

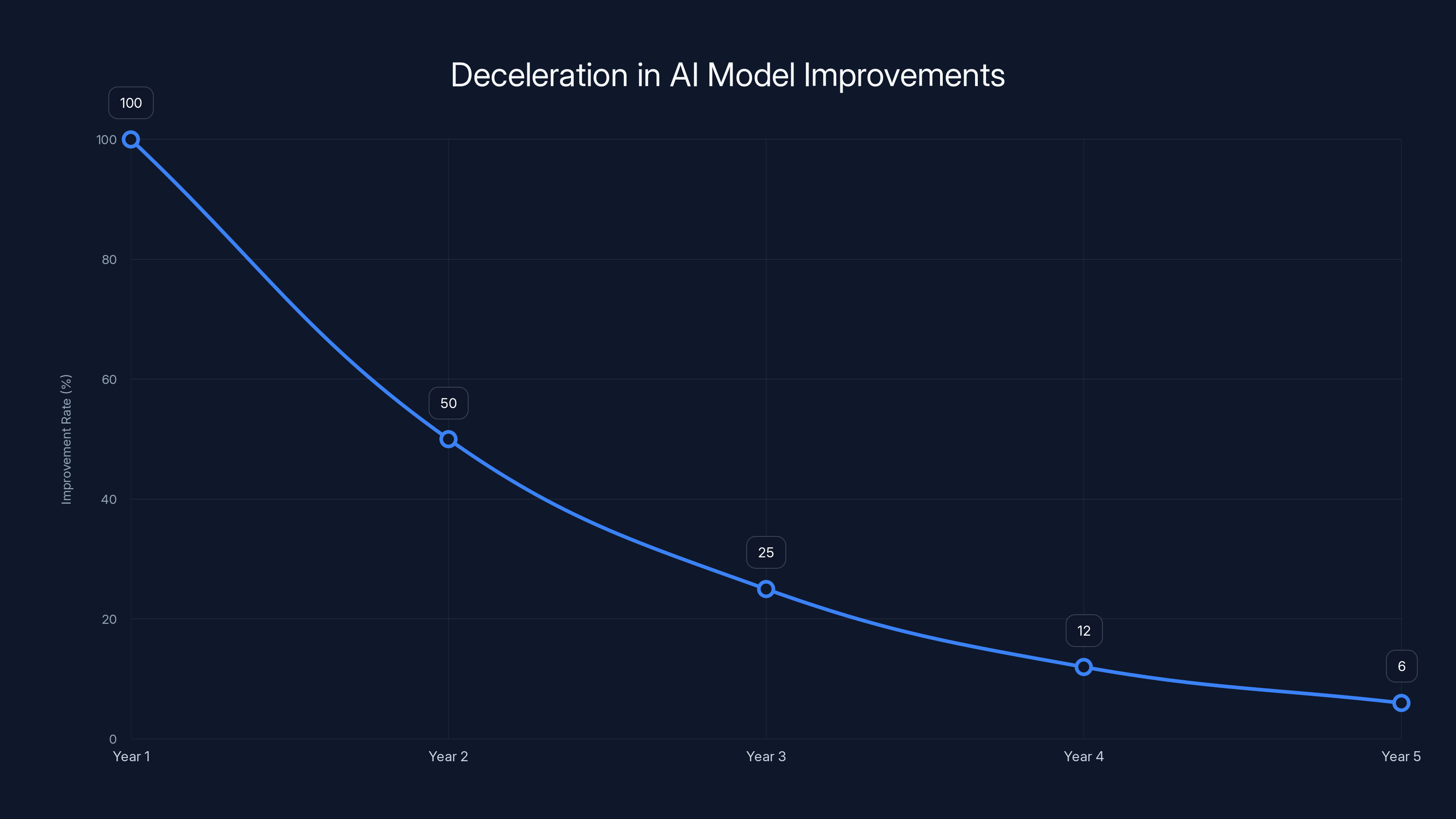

The chart illustrates a projected deceleration in AI model improvements, following an S-curve trajectory. Estimated data suggests significant slowdowns in advancement rates over the next five years.

Section 1: Anthropic's $350 Billion Valuation—Expensive or Actually Reasonable?

The Headline That Made Everyone Gasp

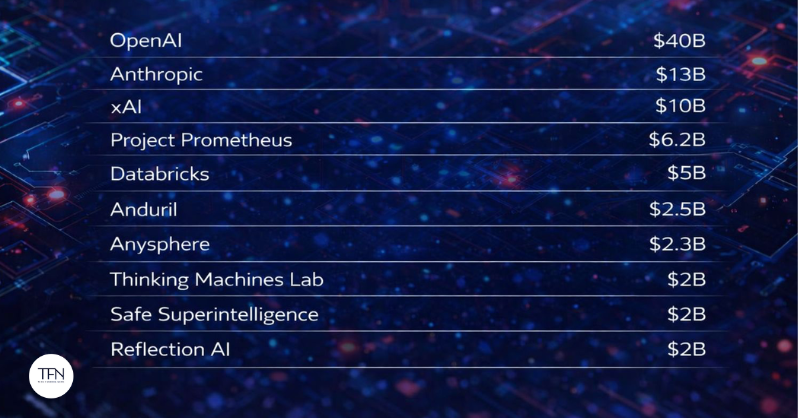

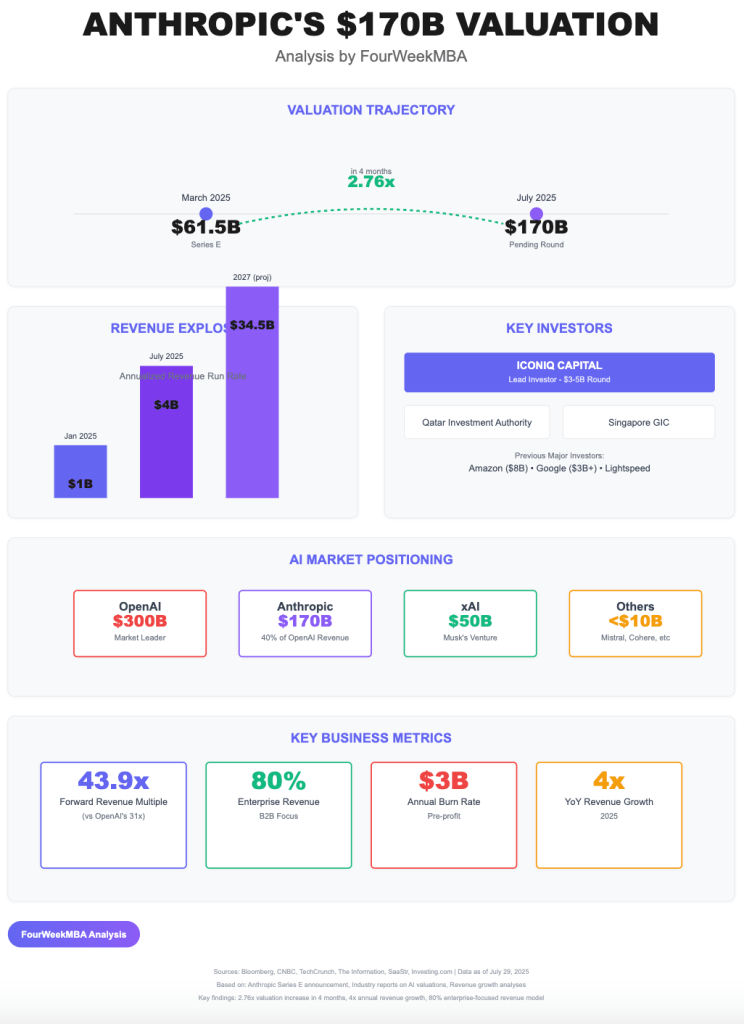

When news broke that Anthropic raised

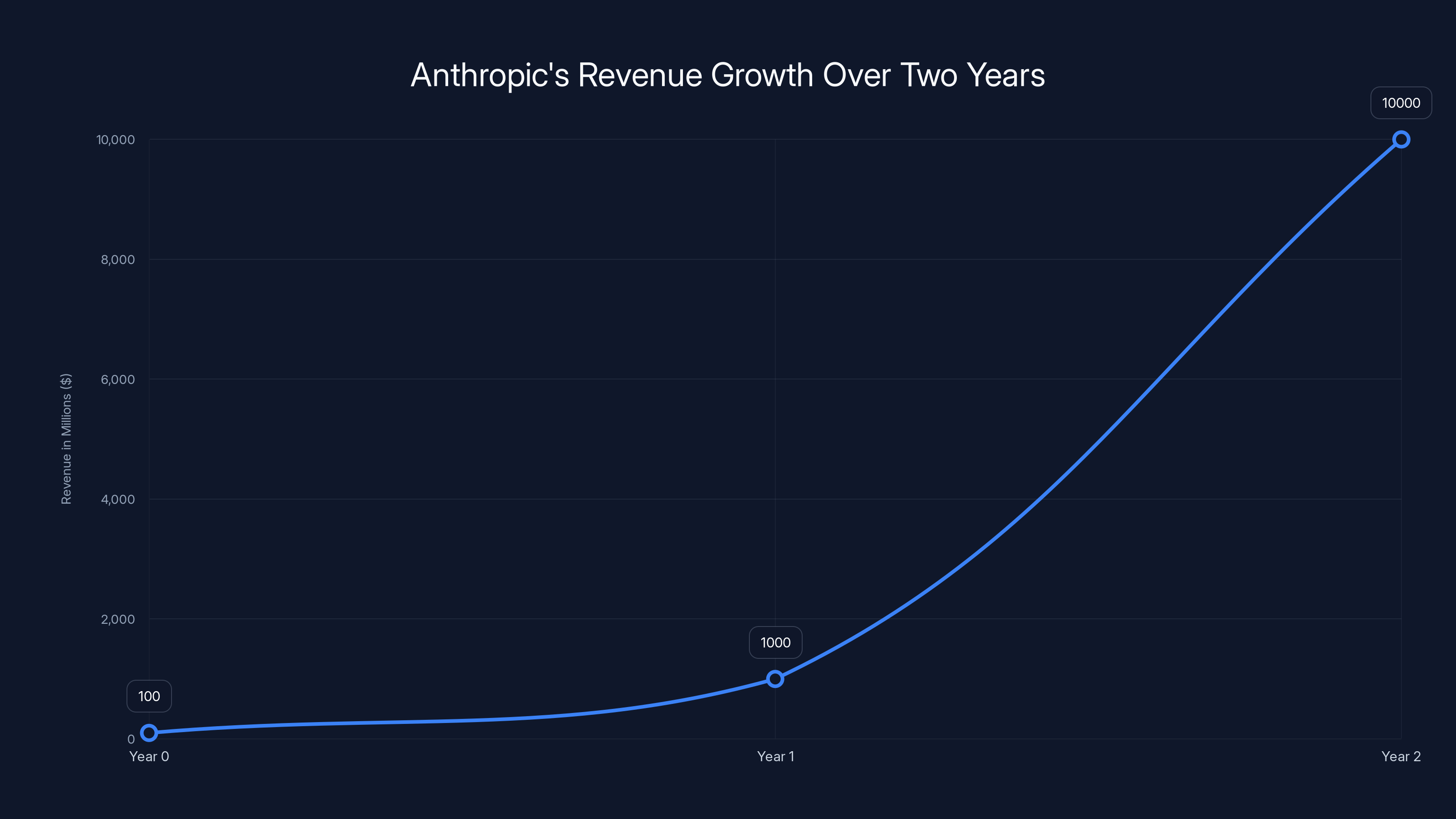

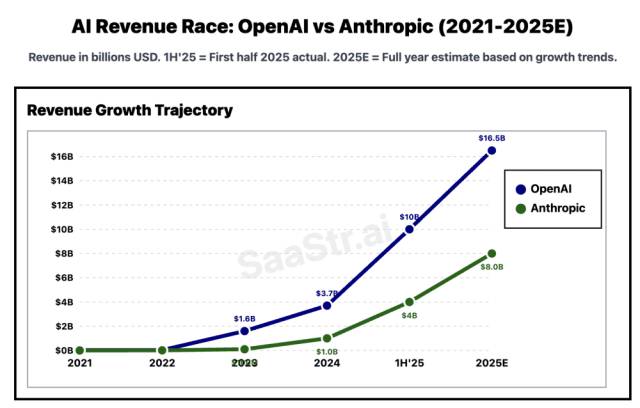

But here's where understanding revenue multiples transforms your perspective. Two years ago, Anthropic was doing approximately

Let's do the math on what this actually means for the valuation multiple. If Anthropic achieves even conservative 3x growth in 2026 to reach

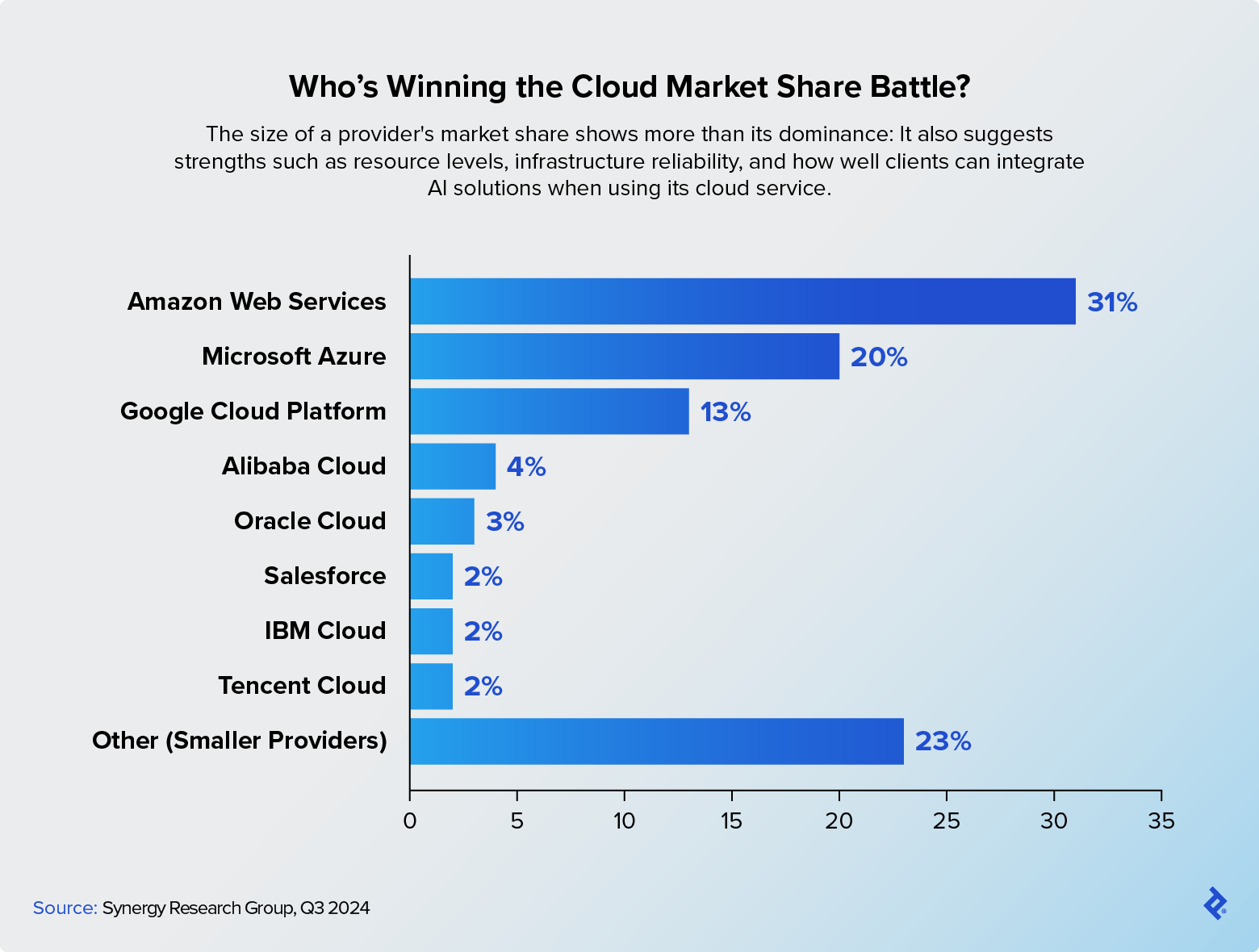

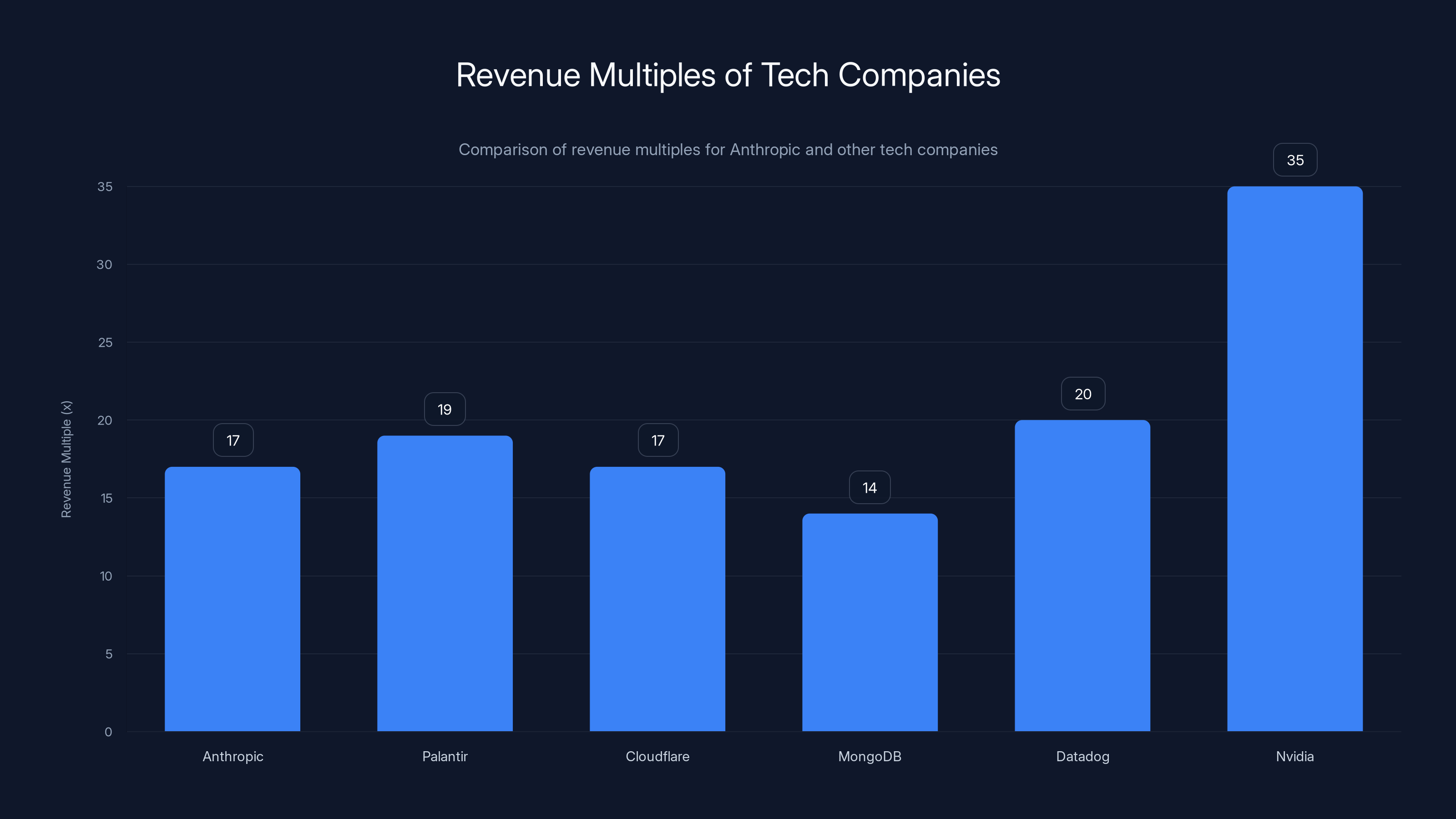

For context, here's where established companies trade:

- Palantir Technologies: Trading at 18-20x revenue

- Cloudflare: Valued at 16-18x revenue

- MongoDB: Historically valued at 12-15x revenue

- Datadog: Trades at 19-22x revenue

- Nvidia (during AI boom periods): 30-40x revenue

Suddenly, Anthropic at 17x revenue doesn't look like an outlier. It looks like a reasonable valuation for a company showing 10x annual growth in the fastest-growing market in technology. The investors who got in at $170 billion three months prior just doubled their money in a four-month period—an annualized IRR of approximately 600-800%. That's the kind of return that justifies risk and attracts capital.

The Growth Trajectory That Broke the Models

What separates Anthropic from previous "expensive" startup valuations is the sustained growth rate. Most SaaS companies that reach billion-dollar revenue levels experience dramatic deceleration. Their growth curves flatten. Anthropic's curve doesn't look like a typical sigmoid. It looks like exponential growth that's defying gravity.

The question isn't whether $350 billion is expensive in absolute terms. The question is whether a company showing this growth rate—in the highest-TAM market in technology—justifies a high multiple. And the answer, according to fundamental venture investing mathematics, is yes.

But there's a critical assumption baked into this thesis: Anthropic must maintain or grow its competitive moat. If they stumble on model quality, if open-source alternatives improve faster than expected, if regulatory constraints suddenly limit their addressable market—the valuation would decompress rapidly. The premium they're trading at is entirely justified by their current position, but fragile if that position erodes.

Section 2: Enterprise AI Has a Clear Winner—And It's Claude

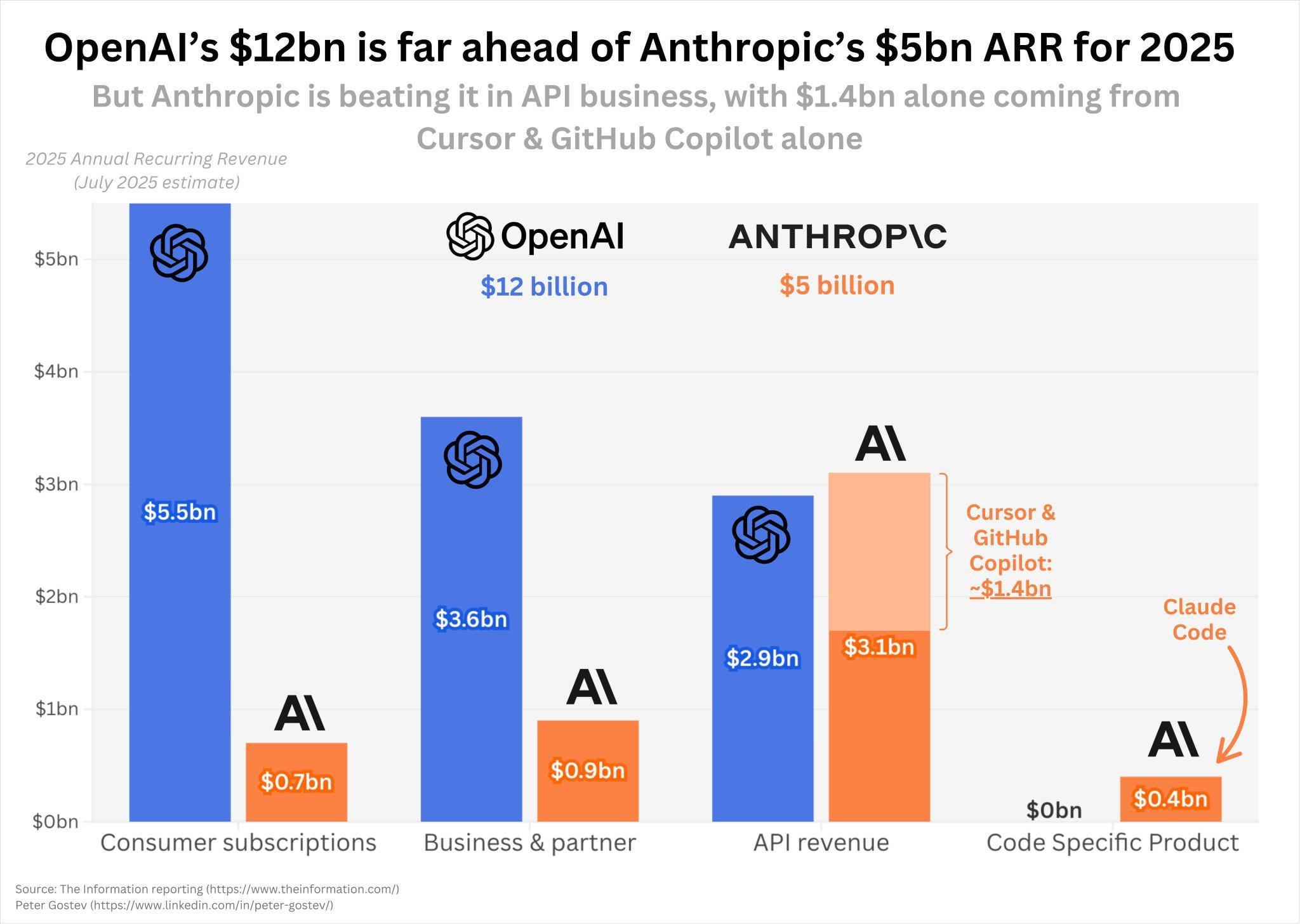

The API Wars: Claude's Unexpected Victory

One of the most under-discussed facts in AI is that Claude has functionally won the enterprise API market. This isn't based on marketing hype or venture narratives. It's based on what developers are actually building with, where ISVs are placing their bets, and which models are being integrated into production systems.

At the API level, the competitive landscape is remarkably clear:

- Enterprise customers evaluating AI infrastructure choose Claude-based solutions at significantly higher rates than alternatives

- Developer sentiment surveys show Claude consistently ranking above GPT-4 for reliability, output quality, and consistency

- The companies that have built billion-dollar valuations on top of AI foundations (Cursor, Lovable, Replit, Harvey, Lore) predominantly use Claude as their underlying model

- Anecdotal feedback from CTOs and engineering leadership suggests a decisive preference for Claude's architecture, token limits, and cost economics

This matters because it represents the first time a company other than Open AI has achieved clear technical and market superiority at the foundational AI layer. It suggests that Open AI's first-mover advantage and network effects weren't as durable as many assumed. It demonstrates that technical excellence and competitive execution can overcome product inertia. And it indicates that the AI market has room for multiple winners at the platform level—but clear hierarchy at the model level.

The signal is significant: when you're building something important in AI in 2025, you're probably building on Claude. That assumption was impossible to make about anything besides Open AI two years ago.

Anthropic's Three-Market Strategy: Why They're Not Just a Model Company

What elevates Anthropic beyond being "the better model company" is their expansion into distinct product markets. Understanding these three markets is essential to understanding where their $350 billion valuation actually derives from.

Market 1: Enterprise API and ISV Partnerships

This is the foundation. Anthropic sells access to Claude through their API, enabling enterprises and independent software vendors to build AI-powered products on top of their models. This is the traditional cloud infrastructure play—similar to AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud selling compute resources. The economics are favorable: high gross margins, predictable consumption-based billing, and sticky customers who've integrated deeply into their architecture.

The competitive advantage here is technical superiority. If your model is better, faster, and more reliable than alternatives, enterprises will pay a premium. Anthropic's position here appears durable.

Market 2: Claude Code—The Developer Tools Play

In 2025, Anthropic launched Claude Code, directly competing in the developer productivity tooling space that Cursor has pioneered. Instead of developers using Cursor for 50% of their coding work and GPT-powered alternatives for the other 50%, Anthropic wants to own 100% of that workflow.

This is a power move because it:

- Captures higher per-developer ARPU (annual recurring per user) than API sales

- Creates switching costs as developers embed the tool into their daily workflow

- Enables direct customer relationships rather than selling through ISVs

- Builds a product category that could command premium valuations (see: Figma's enterprise value relative to usage-based alternatives)

The risk for Cursor, which raised at a $27 billion valuation, is that Claude Code attracts the same users they've worked hard to onboard. The risk for Anthropic is that they're now competing directly with GitHub Copilot (backed by Microsoft's distribution and Azure integration) and Cursor (a pure-play developer tool that can iterate faster).

Market 3: Claude Workspaces—The Microsoft Office Killer Bet

Perhaps most audacious is Claude Workspaces, Anthropic's play for the knowledge worker suite market. This is explicitly positioning Claude as the AI layer for the tasks that Microsoft Office dominates: document creation, data analysis, presentation building, spreadsheet manipulation, and collaborative work.

The scale of this market is almost incomprehensible. Every knowledge worker on Earth uses some version of office productivity tools. Microsoft Office has 365+ million users. Google Workspace has 6+ million organizational customers. The annual spend on productivity software exceeds $50 billion globally. If Anthropic can capture even 5-10% of this market by making Claude Workspaces genuinely better at knowledge work than traditional tools, the revenue potential exceeds their current enterprise API business by 2-3x.

This is why Claude Workspaces is a "terrifying proposition for Microsoft" from the podcast analysis—it threatens not just a product category, but one of the largest revenue streams in enterprise technology. Microsoft's entire enterprise licensing strategy assumes knowledge workers need Office. If Claude Workspaces becomes genuinely superior for the kinds of work these tools enable, that assumption evaporates.

Anthropic experienced a 10x annual growth in ARR, reaching $10 billion in just two years. Estimated data.

Section 3: The Cursor Paradox—When Your Supplier Becomes Your Competitor

The Scorecard Shift

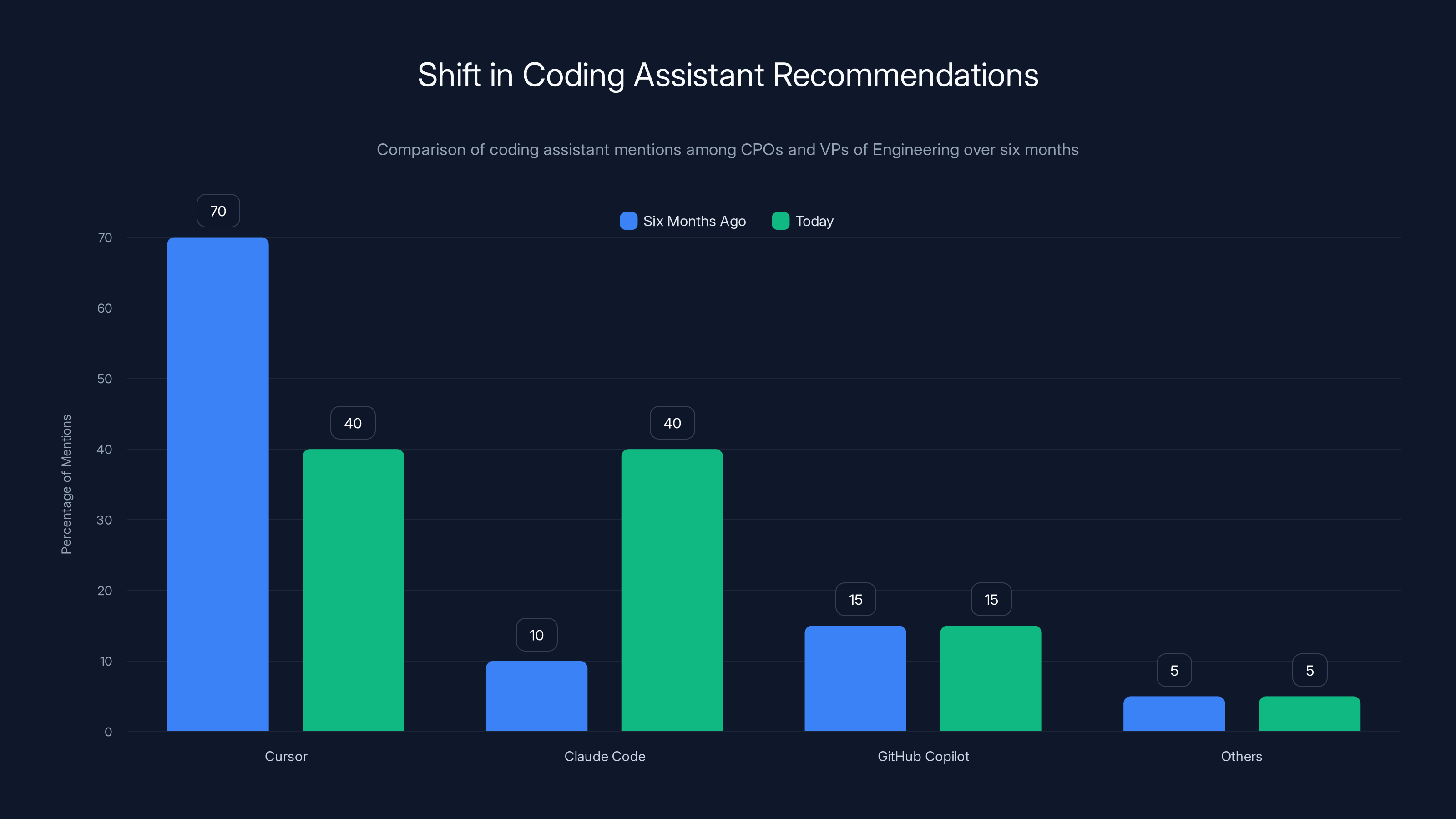

Six months ago, if you asked 100 CPOs (Chief Product Officers) and VPs of Engineering what coding assistant they recommended, the majority would mention Cursor first, with GitHub Copilot second, and others scattered across the remaining landscape. Today, that conversation has shifted. Claude Code is mentioned with the same frequency as Cursor in sophisticated engineering organizations. And Cursor—still an excellent product—has dropped in mentions from roughly 70% to 40% in a compressed timeframe.

This isn't because Cursor got worse. The product is arguably better than it was six months ago. But Cursor exists in a market where the supplier they depend on (Anthropic, via Claude) just launched a direct competitor. The game theory here is stark and uncomfortable.

Why Cursor Should Be Nervous (But Not Panicking Yet)

Cursor has graduated into a competitive tier that few startups ever reach. They're not competing with small YC companies or forgotten dev tools. They're directly competing with:

- Claude Code (backed by a $350B valuation and unlimited R&D budget)

- GitHub Copilot (backed by Microsoft's distribution, Azure credits, and enterprise relationships)

- Vim and VSCode extensions (backed by existing editor dominance)

That Cursor has a seat at this table at all is a signal of success. Many competitors have been eliminated entirely. But the competitive dynamics are treacherous. They're outgunned on distribution (GitHub Copilot has GitHub's 100M+ developers), on capital (Claude Code has Anthropic's multi-billion dollar backing), and on business model flexibility (Microsoft can subsidize Copilot losses to protect Office productivity revenue).

The existential risk isn't immediate. It's medium-term. If Anthropic decides that owning the full developer productivity stack is more valuable than taking API revenue from Cursor, they could:

- Restrict API access for coding-specific use cases

- Prioritize Claude Code development with better models before making them available via API

- Undercut Cursor's pricing by bundling Claude Code with other productivity products

- Acquire the team (Cursor's founders would likely command a $5-10B acquisition price given the company's performance)

The scorpion-and-the-frog metaphor from the original analysis applies here. Anthropic has no rational reason NOT to eventually compete more aggressively with Cursor. But Cursor currently represents roughly $1 billion a year in essentially free revenue for Anthropic (in the form of API consumption). Killing that would be economically irrational unless the upside from owning the full stack exceeds this number.

The Real Opportunity: Product Differentiation

But here's the path where Cursor survives and thrives: pure product differentiation and developer lock-in.

Cursor's advantages are real:

- Editor integration: Cursor is building a complete IDE experience, not bolting AI onto an existing tool

- Iteration speed: A focused startup can ship features faster than a model company can

- UX focus: Cursor's interface and user experience are specifically designed for developer workflows

- Switching costs: Developers who've trained on Cursor's keyboard shortcuts, features, and interface experience friction moving to GitHub Copilot or Claude Code

- Community and ecosystem: Cursor has a rabid user base providing feedback and creating plugins

If Cursor can maintain a 10-15% feature advantage and deliver dramatically superior UX compared to Claude Code and GitHub Copilot, they have a viable long-term business. Developers will pay premium prices for tools that make them materially faster. The question is whether Cursor can maintain this differential as Anthropic and Microsoft pump unlimited resources into their competing offerings.

Section 4: Open AI's Existential Risk—The Competitive Moat That Eroded Faster Than Expected

The Valuation Collapse That Hasn't Been Named Yet

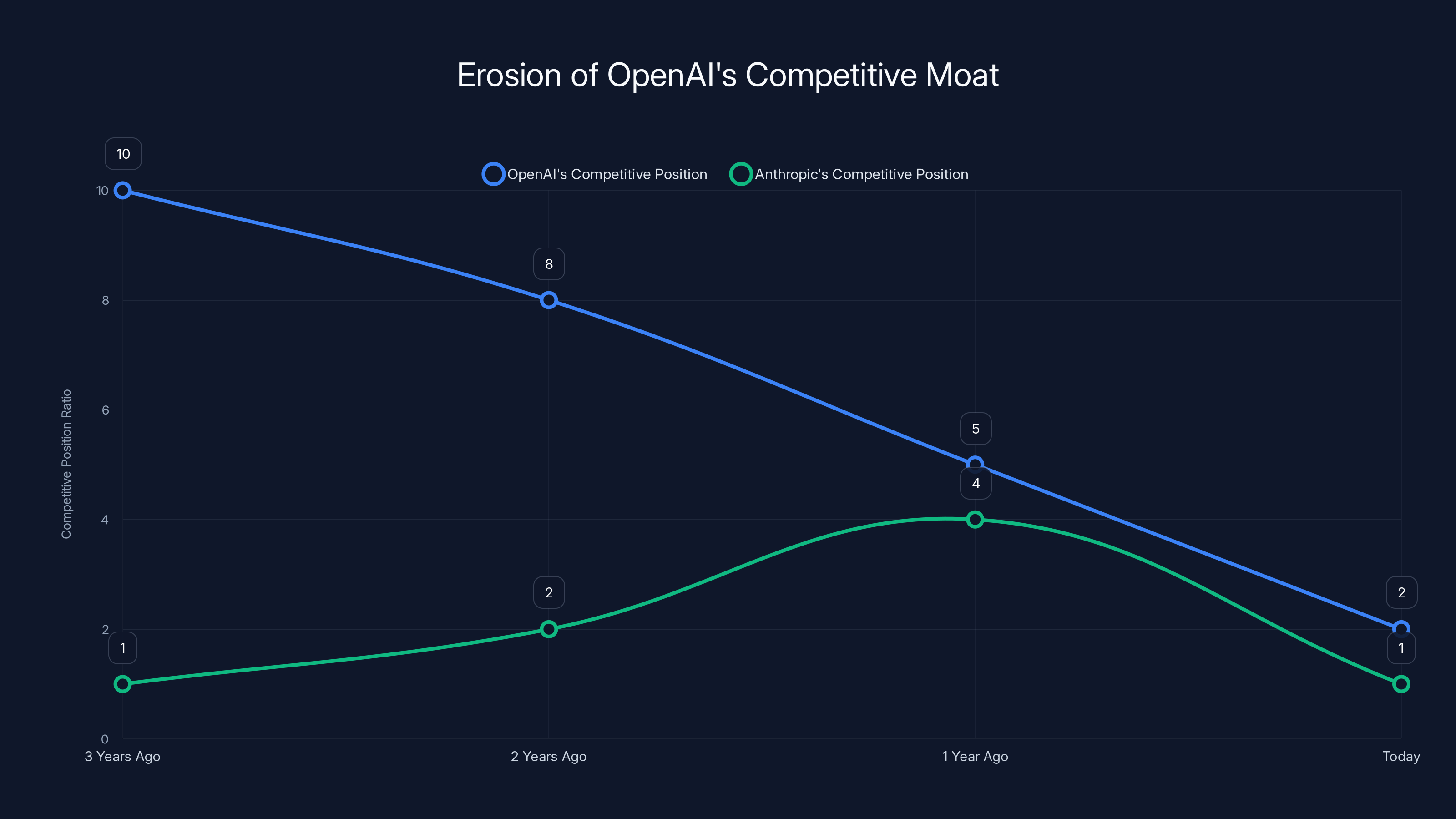

Three years ago, Open AI's competitive position relative to Anthropic was approximately 10:1 in Open AI's favor. They had:

- The only production-grade large language model

- Hundreds of millions of users via Chat GPT

- Dominant developer mindshare and API adoption

- First-mover advantage in the enterprise market

- Relationships with Microsoft, partners, and ecosystem companies that reinforced their position

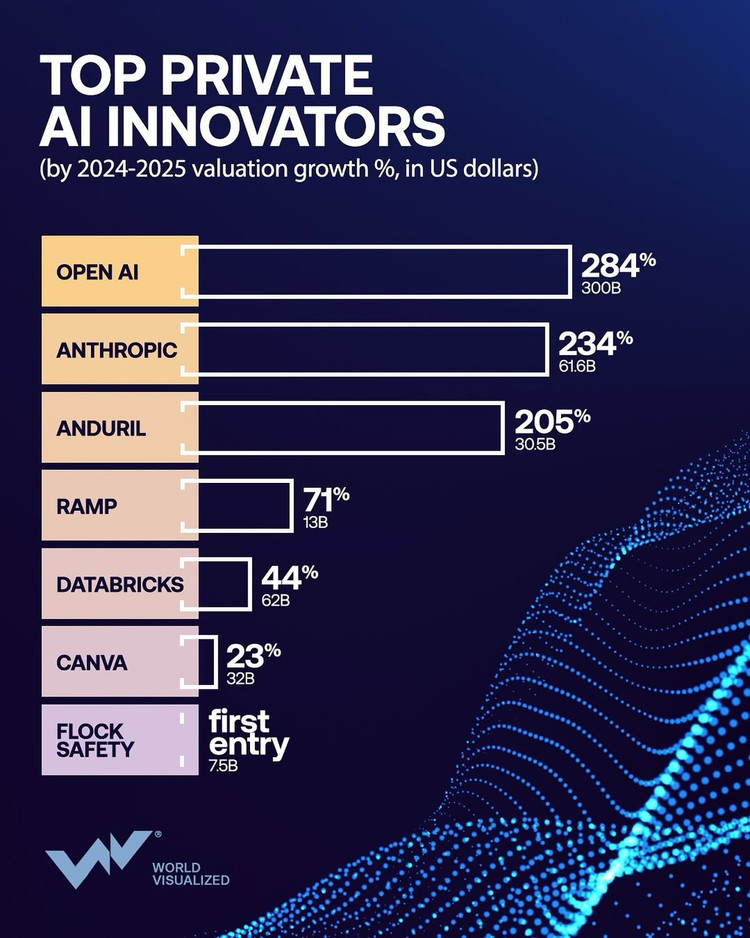

Today, the competitive ratio has inverted. Anthropic's relative position has improved from 1:10 to approximately 1:2—meaning Anthropic is only 50% of the size in competitive strength compared to Open AI, rather than 10% of the size. In a two-year period, Open AI's competitive moat eroded by 80%.

This isn't a narrative about two companies with different business models competing in harmony. This is a zero-sum competitive dynamic in one of the fastest-growing markets in technology. Every developer choosing Claude is a developer not using GPT-4. Every enterprise deploying Anthropic models is capital and resources not flowing to Open AI. And the second-order effects are severe.

The $100 Billion Problem

Open AI's computational infrastructure requirements are growing faster than their revenue. Training frontier models requires exabytes of compute, which translates to billions in annual infrastructure costs. The half-life of an LLM—the time before a model becomes technically obsolete and must be replaced—has shrunk to less than 100 days. A model released 90 days ago that doesn't improve on the current frontier is immediately deprecated in developer workflows.

This means Open AI isn't just competing to stay ahead. They're competing in an arms race where falling behind even temporarily means losing developers, customers, and enterprise relationships. And the capital requirements are staggering.

Industry analysis suggests Open AI will need approximately $100 billion in capital over the next 2-3 years to:

- Fund frontier model training

- Compete with Anthropic's expanding product offerings

- Build infrastructure to compete with Microsoft (in enterprise) and Anthropic (in pure AI capability)

- Maintain margins as competition increases and pricing pressures mount

This is more capital than Open AI has spent cumulatively since inception. It's more capital than most companies will raise in their entire history. And the assumption is that Open AI can access this capital continuously, without macroeconomic disruption, without investor sentiment shifting, and without better opportunities emerging.

The Comparative Strength Analysis

Meanwhile, their competitors are in substantially better positions:

Anthropic's Advantages:

- Superior model quality at the frontier (consensus among developers and enterprises)

- Better unit economics: Higher gross margins from API sales and cleaner business model

- Diversified revenue streams: Not dependent on enterprise subscriptions (Chat GPT Plus) but building product layers (Claude Code, Claude Workspaces)

- Stronger funding: Access to seemingly unlimited capital, no urgency to monetize immediately

- Cleaner cap table: Fewer investor relationships to manage

Gemini's Advantages (via Google):

- Unlimited capital: Google's enterprise cash flows can fund Gemini development indefinitely

- Distribution: Integrated into Search, Gmail, Google Workspace, Android—reaching billions of users

- Massive cash flow: Google's core business generates $90B+ annually, making Gemini development an rounding error

- Patience: Can absorb losses for years while capturing market share

x AI's Advantages:

- Founder capability: Elon Musk's track record building companies and moving fast

- Potential capital: Trump administration relationships could translate to government contracts and funding

- Uncompromised vision: No board dynamics or investor constraints limiting product decisions

Open AI, conversely, faces capital constraints, competitive pressure, governance complexity, and the expectation from investors and the public that they'll continue accelerating. The margin for error is nonexistent.

The AOL Scenario—Still Existing, But Irrelevant

The scariest bear case for Open AI isn't that they go to zero. They won't. With 800 million users, they'll always be able to monetize Chat GPT. The scary scenario is that Open AI becomes AOL in the broadband era: technically still existing, still generating revenue, still used by grandmothers looking up recipes, but completely irrelevant to the actual cutting edge of technology.

An AOL-like future for Open AI would look like:

- Developers choosing Anthropic, Google, or others for new projects

- Enterprise customers gradually migrating off GPT-4 to competitive models

- Chat GPT remaining popular as a consumer product, but treated as a legacy tool

- Investors and top talent departing as the company trajectory becomes clear

- Management churn as the original vision of AGI development shifts to derivative products

This outcome wouldn't require Open AI to completely fail. It would just require them to fail to maintain leadership in a market where being first doesn't guarantee long-term dominance. The precedent exists: IBM was the dominant computer company. Intel was the inevitable winner of processors. Yahoo owned web search. Nokia owned phones. Market leadership in technology is notably temporary.

Open AI's challenge is executing a turnaround before capital constraints, competitive pressure, or macroeconomic disruption eliminate their runway. The clock is ticking.

Section 5: Apple's Gemini Choice—Why Platform Relationships Trump Product Excellence

The Decision That Shocked Nobody (And Everyone)

When Apple announced it was defaulting to Google's Gemini for Siri integration rather than continuing its relationship with Open AI, the reaction was split. Some interpreted it as a signal that Open AI had lost Apple's confidence. Others understood it as a straightforward business decision based on existing relationships and integration economics.

The reality is both. Apple's decision was rational, but the implications of that decision extend far beyond the specific partnership.

The Historical Context: Google Pays Apple

Google and Apple have maintained a multi-billion-dollar relationship for over a decade, structured as follows: Google pays Apple substantial sums (estimated at $10-20 billion annually, though never officially disclosed) in exchange for default search placement in Safari and other Apple products. This arrangement is one of the largest revenue-sharing agreements in technology.

When Apple needed to choose an AI model provider for Siri, the logical decision was to default to a company they already have an established financial relationship with. The incremental cost of integrating Gemini versus Open AI is minimal, but the benefit of reinforcing their existing relationship with Google is significant. Google gets to expand their market share in AI. Apple maintains their partnership dynamics. Everyone wins except Open AI.

Why This Matters More Than Surface Analysis Suggests

The decision itself (Gemini over GPT) is a small loss for Open AI. Siri integration is a meaningful but not transformative use case. More significant is what the decision signals about platform relationships and distribution leverage.

Apple just demonstrated that they'll default to models based on relationship and business partnerships, not necessarily technical merit. This suggests:

-

Platform defaults matter more than quality: If Apple (known for obsessive product quality) chose a partner based on business relationships, other platforms will too. This favors Google, Amazon, and Microsoft who have existing revenue-sharing arrangements.

-

Distribution is becoming more consolidated: The companies that control platforms (Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon) will increasingly default to their own AI or to partners they have business relationships with. This creates a moat for dominant platforms and disadvantages pure-play AI companies.

-

Integration depth reduces competition: Once Gemini is deeply integrated into Apple's ecosystem, the switching cost to replace it is high. Apple users will encounter Gemini as "the AI assistant" and won't have reason to try alternatives.

-

Relationship economics exceed technical excellence: Open AI proved they could build better models than Google. But technical superiority doesn't overcome the gravitational pull of existing business relationships.

The Broader Implication: Platform AI vs. Standalone AI

This decision is emblematic of a larger trend: the AI market is fragmenting into platform-integrated AI (Google AI in Google products, Microsoft Copilot in Microsoft products, Apple Intelligence in Apple products) and standalone AI (Open AI, Anthropic, and others selling their capabilities via API or direct product).

In the platform-integrated layer, companies with existing distribution and business relationships have a durable advantage. In the standalone layer, technical excellence and developer adoption matter more. Open AI has historically been strongest in the standalone layer. The Apple decision suggests that the platform layer—larger in revenue and users—will be dominated by companies with existing platforms.

This dynamic favors Anthropic (which can establish distribution through multiple partners without existing relationships) over Open AI (which is being sidelined by strategic partnerships). It explains why Anthropic's three-market strategy (API, Claude Code, Claude Workspaces) focuses on building direct relationships and products rather than relying on platform partnerships.

Cursor's mentions have dropped from 70% to 40%, while Claude Code has risen to match Cursor's current level. Estimated data based on narrative.

Section 6: The a 16z $15 Billion Fund—Why Mega-Funds Make Mathematical Sense

The Numbers That Justify the Narrative

Andreessen Horowitz's $15 billion fund announcement shocked the venture market for one simple reason: it represented 22% of all venture capital raised in the entire year of 2025. In other words, a single firm raised capital equivalent to roughly one-fifth of the entire venture ecosystem.

This prompted immediate criticism. How can a single fund represent such a large portion of the market? Doesn't this create concentration risk? Can any firm effectively deploy $15 billion? Where's the alpha when you're putting money into markets this large?

The cynical narrative is that venture capital has become a game of assets under management (AUM), with firms optimizing for fund size rather than returns. The mathematical narrative is more compelling: mega-funds actually make sense if the investment thesis is concentrated in a small number of huge bets.

The Portfolio Math

Imagine a

Conservative scenario:

- 15 portfolio companies

- Average check size: $1 billion per company

- Average return: 10x

- Fund return: 15 × 10x = 150x, or $2.25 trillion net

- IRR (over 10 years): 58%

Moderate scenario:

- 10 portfolio companies

- Average check size: $1.5 billion per company

- Average return: 20x

- Fund return: 10 × 20x = 200x, or $3 trillion net

- IRR (over 10 years): 68%

Aggressive scenario:

- 5 portfolio companies

- Average check size: $3 billion per company

- Average return: 30x

- Fund return: 5 × 30x = 150x, or $2.25 trillion net

- IRR (over 10 years): 58%

In all scenarios, a concentrated

How Mega-Funds Changed the VC Dynamic

The emergence of mega-funds (

- Make 20-50 bets of $5-25M each

- Accept that most companies would fail, and success would come from a few massive winners

- Build diversified portfolios that reduced concentration risk

- Enable junior partners to lead deals and develop expertise

Mega-funds invert this logic. A $15 billion fund can't make 100 small bets efficiently. The transaction costs, due diligence burden, and management overhead don't scale. Instead, they optimize for:

- 10-20 large bets of 2B each

- Concentrated thesis in high-TAM markets with clear winners emerging

- Participation in mega-rounds where the firm can write checks large enough to maintain ownership percentages

- Access to deal flow from other mega-funds and limited partners

The dynamics create a winner-take-most outcome in venture capital itself. Firms like a 16z, Sequoia, and Khosla Ventures that can deploy mega-fund capital have access to the best deals. Smaller firms get to follow or are excluded entirely. The skill differential required to manage a

The Hidden Risk in Mega-Fund Concentration

But there's a critical risk baked into this structure: what happens when returns decelerate?

A16z's $15 billion fund is betting that AI will deliver extraordinary returns. But if:

- Open-source models reduce the premium of frontier models

- Regulation constrains AI development

- Macroeconomic pressures reduce capital availability for follow-on rounds

- The AI market consolidates and 90% of value accrues to 2-3 companies rather than 10-20

Then a $15 billion fund concentrated in AI companies might return 3-5x instead of 10-50x. That's still excellent returns, but it dramatically underperforms the public markets in a scenario where AI becomes a mature industry rather than an explosive growth phase.

Mega-funds are rational bets on explosive growth in concentrated markets. They're somewhat irrational if growth moderates or if the market becomes commoditized. a 16z's thesis requires that AI remains a white-hot growth market for the entire fund lifecycle, and that their portfolio companies capture outsized value.

Section 7: California's Wealth Tax—The Founder Exodus and Its Implications

The Tax That Triggered the Great Migration

In 2024-2025, California passed and moved toward implementation of a wealth tax on ultra-high-net-worth individuals, projected to impact founders and early-stage investors with net worth exceeding $50-100 million. The immediate response was pronounced: Sergey Brin, Larry Page, Peter Thiel, and dozens of other prominent founders began relocating out of California to tax-advantaged jurisdictions (primarily Texas, Nevada, and Florida).

This wasn't symbolic migration. It was mass relocation of capital, decision-making authority, and founder networks out of the state that created Silicon Valley. The implications extend far beyond tax policy—they represent a potential inflection point in American innovation geography.

The Mathematics of the Wealth Tax

California's wealth tax structure (specific details vary by proposal, but the general framework is consistent) operates as follows:

- 2% annual tax on net worth above $50 million

- Potential increases to 3-4% on net worth above $100 million

- Applied to residents and "economically engaged" individuals in the state

For a founder with a

By contrast, Texas and Florida have no state income tax and no wealth tax. Florida also offers homestead exemptions that protect primary residences from property taxes. This creates a simple economic incentive: a founder with a $500 million net worth can:

- Remain in California and pay $10-20 million annually in wealth taxes

- Relocate to Florida or Texas and pay approximately $0 in equivalent taxes

- Over a 30-year period, the tax arbitrage exceeds $300 million

This isn't a marginal incentive. This is a structural, economically overwhelming incentive to leave the state.

The Flywheel Effect of Founder Exodus

But the implications extend far beyond individual tax savings. When founders and ultra-high-net-worth individuals leave a region, the flywheel effects are severe:

1. Capital Flight

- Founders take their venture funds with them or shift LP relationships to funds based in their new state

- LPs in California-headquartered funds become concentrated in migrating founders with new tax residency

- Venture dollars that historically flowed to California-based investments increasingly flow to Texas, Florida, and Nevada-based companies

2. Founder Network Fragmentation

- Silicon Valley's competitive advantage has historically been concentrated founder and investor networks

- When founders disperse, the density of relationships, collaboration, and intelligence-sharing decreases

- A founder in Austin or Miami has less casual access to other mega-successful founders and investors

- This network effect favors early-stage companies in the new hubs but disadvantages later-stage acceleration

3. Talent Migration

- Founders and wealthy technologists often take key employees with them

- The most skilled engineers, product managers, and operators receive equity compensation and participate in founder relocation decisions

- Talent concentration in new geographic hubs creates competing innovation centers

4. Institutional Inertia Failure

- Universities and research institutions in California (Stanford, Berkeley, Caltech) maintain their innovation advantages

- But startup formation and capital concentration can shift to regions that offer better tax treatment

- The result is a bifurcated innovation landscape: basic research in California, commercialization in Texas and Florida

Will This Reverse Innovation Geography?

The long-term implication is a potential decentralization of venture capital and startup formation out of California. But this decentralization comes with caveats:

Arguments for Persistent California Dominance:

- University research output and Stanford's engineering capabilities remain unmatched

- Existing venture ecosystem depth and network effects persist despite individual relocation

- High-TAM companies (AI, biotech) still benefit from proximity to leading researchers

- Network effects are sticky; many founders may relocate for tax reasons but maintain relationships in California

Arguments for Genuine Geographic Shift:

- Texas (Austin) and Florida (Miami, Tampa) have built credible startup ecosystems with lower regulatory burden

- Founder migration creates concentrated capital in new hubs, enabling larger and larger rounds

- Tax arbitrage is a permanent advantage, not temporary

- The next generation of founders may not have the California network dependencies that older generations do

The most likely outcome is bifurcation: California remains a center for frontier research and later-stage scale-up activity, while Texas and Florida capture more startup formation and early-stage capital. This is economically rational from a pure taxation perspective but reduces California's historical dominance as the innovation center of the world.

For venture capital, this means the future involves multiple hubs competing on capital, network, and founder access rather than California's historic monopoly.

Section 8: The Model Optimization Race—Why Improvements Are Decelerating

The Frontier of Diminishing Returns

One of the most under-discussed dynamics in AI is that the pace of frontier model improvements may be decelerating faster than expected. In 2023, Open AI released GPT-4, which represented a massive leap over GPT-3.5. In 2024, Anthropic released Claude 3 Opus, which demonstrated meaningful improvements in reasoning and task performance. But the gap between Claude 3 (released in early 2024) and GPT-4 Turbo (released mid-2023) was smaller than previous generation jumps.

The question for the AI market is whether we're approaching a plateau where frontier model quality improves incrementally rather than dramatically. If this is true, it has profound implications for venture returns and competitive dynamics:

The Mathematics of Marginal Improvement

Consider the following progression:

- GPT-3 to GPT-4: ~500% improvement in MMLU scores (benchmark for language understanding)

- GPT-4 to GPT-4 Turbo: ~15-20% improvement in speed and efficiency, ~5-10% improvement in accuracy

- Claude 1 to Claude 3: ~30-40% improvement in reasoning capability

- Claude 3 to Frontier Today: ~10-15% incremental improvements

If improvements continue decelerating, the trajectory looks like:

- Year 1: 100% improvement (baseline)

- Year 2: 50% improvement

- Year 3: 25% improvement

- Year 4: 12% improvement

- Year 5: 6% improvement

This is a classic S-curve learning trajectory. The frontier moves, but the pace of movement slows as we approach the asymptote of what's possible with current architectural approaches.

Why This Threatens Venture Returns

If frontier model improvements are decelerating, the venture thesis for new AI companies becomes less clear. The original Anthropic thesis was that they could:

- Build superior models that outperform GPT-4

- Capture market share from Open AI

- Grow revenue exponentially as their models improved

- Expand into product categories (Claude Code, Claude Workspaces) that amplified value

All of this assumes sustained frontier improvement. If improvements plateau, then:

- The competitive differentiation between Claude and GPT-4 becomes smaller

- Enterprise customers have less reason to migrate from one platform to another

- Pricing power decreases as models become commodity-like

- Venture returns compress as revenue growth moderates

This is why mega-funds are racing to deploy capital now. The window for venture returns in AI is potentially limited. Once frontier improvements plateau and models commoditize, the economics shift from venture-scale returns (10-50x) to public-scale returns (2-5x), and venture capital migrates to other markets.

The race isn't just to build better models. It's to capture market share and build defensible products before the frontier improvements plateau and the market consolidates.

OpenAI's competitive position has eroded significantly from a 10:1 advantage to a 2:1 advantage over Anthropic in three years. Estimated data.

Section 9: Enterprise AI Adoption—Moving From Proof of Concept to Production

The Gap Between Pilot and Deployment

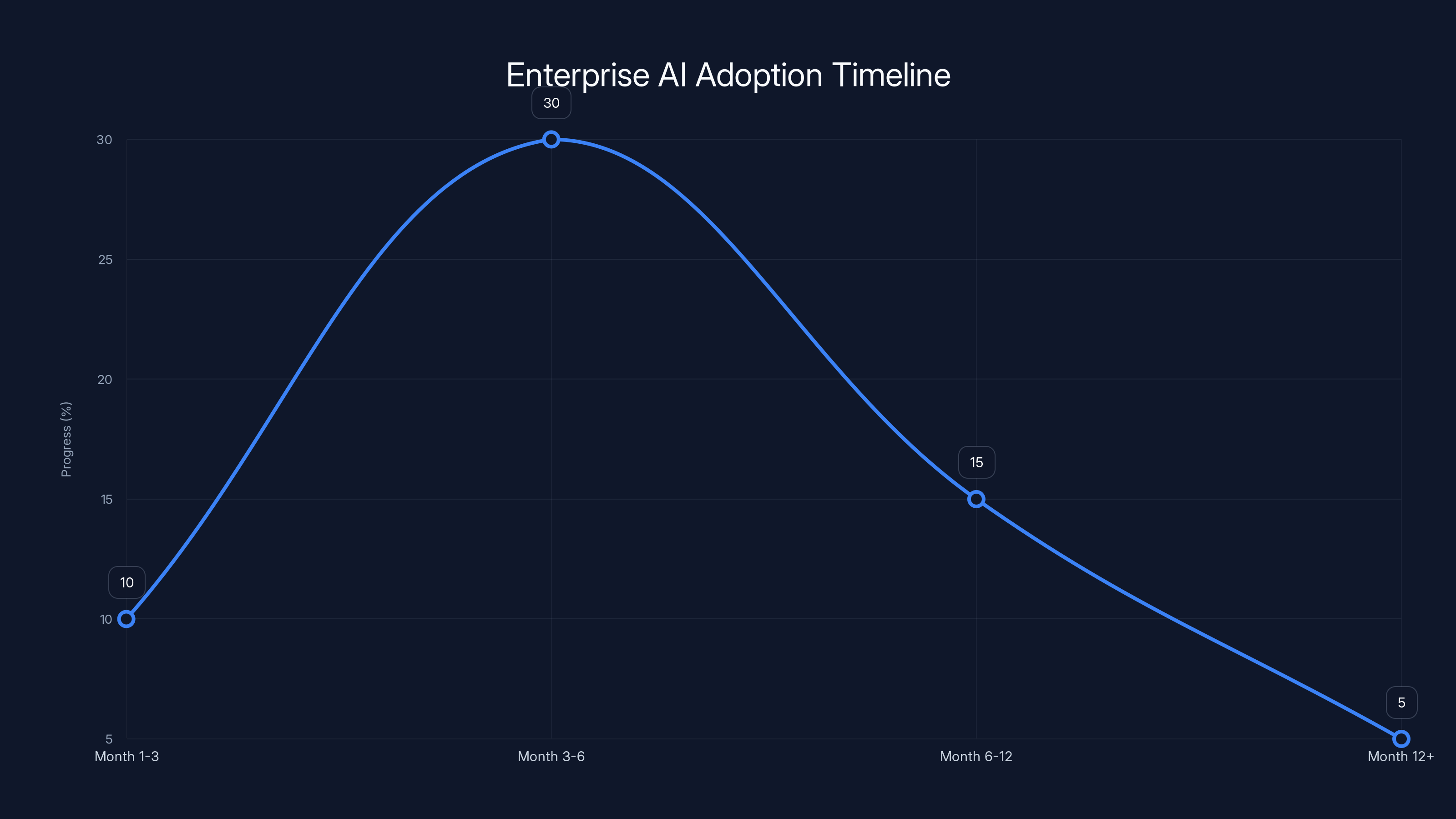

One of the most consistent patterns in enterprise AI adoption is the massive gap between proof-of-concept pilots and actual production deployment. A typical pattern looks like:

- Month 1-3: Enterprise evaluates AI solutions, runs pilot projects with 1-5 teams

- Month 3-6: Pilot shows promise, team expands to 10-20 users, generates positive sentiment

- Month 6-12: Actual deployment stalls. Security concerns, governance requirements, compliance issues, and integration complexity emerge

- Month 12+: Pilot either gets quietly shelved or gets deployed at 1/10th the scale originally envisioned

The conversion rate from pilot to full deployment in enterprise IT has historically been 20-30%. This means a company running an AI pilot with promise has only a 1-in-3 to 1-in-5 chance of enterprise-wide deployment.

This creates a revenue recognition problem for AI platform companies:

- Enterprise evaluations generate pilot revenue (~200K annually for a mid-size enterprise)

- Full deployment generates enterprise revenue (~10M annually for a mid-size enterprise)

- But only 20-30% of pilots convert to enterprise deployments

This means an AI platform company needs a 3.5-5x pipeline of pilot programs to generate the deployment revenue growth investors expect.

Why Anthropic's Enterprise Position Is Durable

One reason Anthropic's enterprise position appears durable is that they're solving concrete production problems that have clear ROI. Claude is being deployed for:

- Code generation and debugging (measurable productivity impact)

- Document analysis and knowledge extraction (clear cost reduction)

- Customer support ticket resolution (measurable efficiency gains)

- Data analysis and reporting (time savings)

These use cases have clear metrics, measurable cost impact, and often ROI that pays for the AI investment within weeks or months. This drives conversion from pilot to production because the business case is transparent and defensible to finance and procurement organizations.

Compare this to more speculative AI use cases ("AI-powered strategic insights", "AI-enhanced brainstorming") where ROI is vague and hard to measure. Anthropic's dominance is partially driven by competing in use cases with clear metrics, not just technical superiority.

Section 10: The Regulatory Wildcard—How Policy Could Reshape the Competitive Landscape

The Policy Uncertainty That Haunts Every Funding Round

One factor that's discussed in venture circles but rarely appears in public analysis is the regulatory uncertainty haunting every AI mega-round. The companies raising billions in 2025 are placing bets in an environment where regulation is still undefined.

Potential regulatory scenarios:

1. Aggressive Regulation Scenario

- Government establishes strict requirements for model transparency and interpretability

- Requirements for human oversight and explainability in certain applications

- Restrictions on training data (potentially limiting access to copyright-protected content)

- Potential export restrictions on frontier models

Impact: Companies like Open AI and Anthropic might see deployment restricted to certain applications or geographies, reducing TAM by 30-50%. However, regulatory barriers also reduce competition, helping market leaders. Venture returns compress from frontier companies but consolidate in leaders.

2. Moderate Regulation Scenario (Most Likely)

- Sector-specific regulations (healthcare AI has specific requirements, financial services has different requirements)

- Transparency and disclosure requirements (must disclose AI use in content generation, decision-making)

- Bias and fairness requirements (models must pass tests for demographic bias)

- Data governance requirements (clear policies on training data sourcing)

Impact: Regulatory compliance becomes a feature investment, not a moat. Companies with resources to handle compliance (Anthropic, Open AI, Google) benefit. Smaller competitors struggle. Returns moderate but don't collapse.

3. Light-Touch Regulation Scenario

- Voluntary industry standards and best practices

- Self-regulation by major players

- Market-driven solutions to risks and harms

Impact: Competitive intensity increases. Venture returns remain high. AI companies race on capability without regulatory constraints.

4. Existential Risk Regulation Scenario

- Frontier model development restricted or banned

- Significant compute requirements for development

- Mandatory safety testing before deployment

- Potential AI licensing requirements

Impact: This would be catastrophic for venture returns. Most mega-rounds assume unrestricted frontier development. This scenario would reduce TAM dramatically and might necessitate M&A consolidation.

Why This Matters for Capital Allocation

A16z's $15 billion fund is implicitly betting on scenario 2 (moderate regulation) where AI remains a high-growth market and regulatory barriers don't fundamentally constrain adoption. If scenario 4 materializes, mega-fund returns compress dramatically.

This is the hidden bet in AI mega-rounds: that regulation will be moderate enough to allow explosive growth but stringent enough to protect established players from disruption by open-source or adversarial competitors.

Section 11: Open-Source AI—The Long-Term Wildcard Nobody's Betting Against Properly

Meta's Llama Release and Its Implications

Meta's decision to open-source Llama models (starting with Llama 2, continuing with Llama 3) was a strategic decision that's dramatically underestimated in its long-term implications. By open-sourcing a competitive language model, Meta made a statement: frontier model quality can be achieved and distributed without proprietary licensing.

This doesn't directly threaten Anthropic or Open AI in the next 1-2 years. Frontier proprietary models are still better than Llama. But the trajectory is concerning. Consider the gap:

- Llama 2 (2023): ~85% of GPT-4 quality

- Llama 3 (2024): ~90-95% of GPT-4 quality

- Llama 4 (2025, hypothetical): 95-98% of frontier model quality

If this trajectory holds, open-source models will achieve parity or near-parity with proprietary models within 2-3 years. This would compress the pricing power of companies like Anthropic and Open AI dramatically.

Why Open-Source Doesn't Kill Enterprise Adoption (Yet)

The conventional argument is that open-source AI will commoditize the market and destroy venture returns. This is partially true but incomplete. Reasons why open-source doesn't immediately kill proprietary AI:

-

Deployment costs exceed licensing costs: Running Llama requires compute infrastructure. For enterprises, proprietary API access (pay-per-token) is often cheaper than deployment and operation.

-

Frontier performance still matters: Even at 95% of proprietary quality, that 5% gap can be the difference between acceptable and unacceptable for certain use cases.

-

Support and reliability: Proprietary vendors provide SLAs, support, and reliability guarantees that open-source doesn't.

-

Optimization and efficiency: Anthropic and Open AI are constantly optimizing their models for inference speed and efficiency, creating ongoing performance advantages.

But the long-term trajectory is clear: open-source models are closing the gap. This isn't a threat for 2025. It's a structural risk for 2026-2027 and beyond.

Investors in mega-funds are implicitly betting that frontier proprietary models will maintain a performance advantage sufficient to justify premium pricing. If open-source models achieve true parity, those returns compress.

Anthropic's valuation at 17x revenue multiple is comparable to other tech giants, aligning with industry standards despite its rapid growth. Estimated data.

Section 12: International Competition and China's AI Strategy

The Geopolitical Dimension Nobody's Discussing

One factor conspicuously absent from most venture capital discussions about AI is the emergence of frontier-quality AI models from Chinese companies. Byte Dance, Alibaba, and others have built or are building competitive language models that rival Western models in certain benchmarks.

The implications are significant:

-

If Chinese models become genuinely competitive, the addressable market for Western AI companies (Anthropic, Open AI) is limited to non-China jurisdictions, reducing TAM by 20-30%.

-

If China restricts adoption of Western AI models, as they've done with other Western technology, enterprises operating in China must use domestic models. This creates a bifurcated global AI market.

-

If China leads in certain AI applications (e.g., e-commerce AI, content moderation for Chinese-language content), they capture outsized value in those categories.

Most venture capital analysis treats AI as a global TAM expansion. In reality, it may be a geo-split expansion where Western companies dominate certain regions and Chinese companies dominate others. This reduces the total addressable market for companies like Anthropic by a material percentage.

A16z's $15 billion fund is effectively betting on a global AI market. If the market splits along geopolitical lines, returns compress.

Section 13: The Talent War—Why Top Researchers Command $10M+ Compensation Packages

When Employees Negotiate Like Founders

One of the most significant shifts in AI company economics is the emergence of $10-20 million annual compensation packages for frontier AI researchers and engineers. These packages (combination of salary, equity, and sign-on bonuses) have become common at Anthropic, Open AI, Google Deep Mind, and other frontier companies.

This creates a cascading problem for smaller AI companies and those focused on applications rather than models:

- Frontier companies (Anthropic, Open AI) can afford $10M+ packages for top researchers

- Large tech companies (Google, Microsoft) can afford $5-10M packages for researchers

- Application companies (companies building on top of models) can barely afford 2M salaries

This talent concentration means the best researchers are working on frontier models, not on building applications. This is inefficient from a market perspective but rational from individual incentive perspective.

It also means frontier model companies have massive labor cost inflation that compresses margins. If Anthropic has 200 researchers each earning

This creates a structural disadvantage for companies without massive funding: they can't hire the talent necessary to compete on frontier research. This reinforces the winner-take-most dynamics of AI.

Section 14: The Platform War—Who Wins If AI Becomes Truly Commodified

Why Distribution Trumps Technology Eventually

Historically in technology, there's a pattern: the company with the best technology initially wins, but eventually the company with the best distribution wins. Consider:

- Search: Google's algorithm was better than Alta Vista's, but Google won because of distribution and network effects

- Cloud: AWS's technology wasn't dramatically better than alternatives, but AWS won because of brand, sales force, and ecosystem

- Mobile: iOS's technology was better than Android's, but Android won because of distribution partners

In AI, if models eventually commoditize (proprietary models lose their technical advantage), the company that can embed AI into the widest user base and workflows wins. That company is Microsoft (via Office, GitHub, Azure), Google (via Workspace, Search, Android), or Amazon (via AWS, Alexa).

Anthropic's three-market strategy (API, Claude Code, Claude Workspaces) is partially a hedge against this outcome. By building direct products, they're not relying on platform partners to distribute their models. They're building distribution themselves.

Open AI's challenge is deeper. They're dependent on partnerships (Microsoft Copilot, Apple, others) for distribution. If models commoditize, those partnerships offer little moat.

Estimated data shows a significant drop in progress after initial pilot success, with only 5% reaching full deployment.

Section 15: The Infrastructure Play—Why Compute Is the Real Winner

The Unglamorous but Durable Business

While venture capital focuses on AI companies and models, the infrastructure business (compute, chips, data centers) may be the more durable winner. Consider the dynamics:

- Model companies compete on capability: Anthropic vs. Open AI vs. Google competes on model quality. One of these may fade as others improve.

- Infrastructure companies compete on cost and availability: Nvidia, AMD, and cloud providers compete on compute economics. There's high price competition, but durable demand.

Every AI model company requires compute. Anthropic needs

Nvidia's dominance in AI chips is partially a result of technical superiority, but increasingly a result of customer lock-in and ecosystem effects. Companies have built their entire AI infrastructure around Nvidia GPUs. Switching to AMD or other competitors involves re-architecting systems, which is expensive and risky.

From a venture perspective, investing in infrastructure (though capital-intensive and lower-margin) may be more durable than investing in model companies. But it doesn't fit the venture return profile as neatly as mega-rounds in application companies.

Section 16: The M&A Endgame—When Consolidation Becomes Inevitable

Why the Venture Market May Look Very Different in 2030

History suggests that venture-backed companies don't stay independent forever. They either go public, achieve sustainable profitability as private companies, or get acquired. Given the capital intensity of frontier AI, the likely endgame for many AI startups is M&A consolidation.

Possible consolidation scenarios:

Scenario 1: Big Tech Acquires the Winner

- Google acquires Anthropic for 1T

- Microsoft acquires Open AI for $200-400B (completing their partial ownership)

- Amazon or Facebook acquires smaller AI companies

Scenario 2: Frontier AI Companies Consolidate

- Open AI and Anthropic merge (unlikely given competitive dynamics)

- One of the smaller AI companies (x AI, other startups) gets acquired by larger founders/operators

Scenario 3: Fragmentation and Sustainability

- AI companies remain independent, competing on capability and applications

- Some go public (Anthropic at $500B+ market cap)

- Others remain private, sustained by massive cash flows

The venture math suggests that mega-rounds only make sense if the company eventually achieves massive scale or gets acquired at a premium valuation. Neither of these is guaranteed. A16z's $15 billion fund is betting on scale and consolidation at high valuations. If that doesn't materialize, returns disappoint.

Section 17: The Ethical and Safety Reckoning—How Values Affect Valuation

When Doing the Right Thing Has Financial Implications

One factor that's rarely quantified in venture analysis is how AI companies' positioning on safety, ethics, and responsible AI affects their valuations and customer adoption. Anthropic has positioned itself as the "safe AI" company, with organizational commitment to Constitutional AI and extensive safety research.

This positioning has tangible business benefits:

- Regulatory advantage: If regulation eventually requires safety testing and verification, Anthropic's existing safety infrastructure provides competitive advantage.

- Enterprise trust: Risk-averse enterprises (financial services, healthcare, government) may prefer Anthropic because of perceived safety commitment.

- Talent attraction: Researchers concerned about AI safety are more attracted to Anthropic than companies perceived as less safety-focused.

- Long-term sustainability: A company that can credibly claim it's built AI responsibly has fewer regulatory and reputational risks.

Open AI, despite founding with a safety mission, has been perceived as increasingly commercial and less focused on safety. This perception may cost them enterprise customers and regulatory goodwill.

While not quantifiable in traditional venture returns models, the safety and ethical positioning of AI companies affects their addressable market, competitive moat, and regulatory risk profile. Companies that can credibly claim ethical AI development may have durable competitive advantages.

Section 18: The Lessons From Previous Technology Booms—What History Teaches Us

When Valuations Based on Exponential Growth Prove Unrealistic

The current AI funding environment is reminiscent of previous technology booms and busts. To understand the implications, it's worth examining what happened in similar environments:

The Dot-Com Boom (1998-2000)

- Companies valued on "eyeballs" and user growth, not revenue

- Massive mega-rounds for companies with no path to profitability

- The bust: 80% of venture-backed companies failed, returning no capital to investors

The Cloud Boom (2008-2012)

- Companies valued on aggressive growth assumptions

- Mega-rounds for companies like Zynga, Groupon, and others

- Some succeeded spectacularly (Salesforce, AWS, Workday), others failed or underperformed

The Mobile Boom (2010-2015)

- Every company needed a mobile strategy or founder

- Mega-rounds for mobile app companies and mobile ad networks

- Most mobile-first companies failed or became acquisition targets

The Pattern In each boom, a new technology category emerges with genuinely massive TAM. Venture capital rushes to fund companies in that category. Some companies are valued rationally based on growth and market dynamics. Others are valued based on hype and speculation. When growth moderates or competition intensifies, the speculative valuations decompress.

The question for AI is: how much of the current mega-round activity is based on rational growth assumptions, and how much is based on speculation and FOMO?

A16z's analysis (mega-funds make mathematical sense) suggests rational thesis. But it assumes that AI companies will continue 10x+ growth for years. If growth moderates to 3-5x, valuations must decompress. History suggests that when exponential growth assumptions prove optimistic, the downside is severe.

Section 19: Strategic Implications for Developers and Builders

What This Funding Landscape Means for Your Startup

If you're building an AI startup or considering an AI strategy, the mega-fund activity creates both opportunities and risks:

Opportunities:

- Capital availability: Never has capital for AI been more available. If you're building in this space, you can raise at favorable terms

- Talent migration: As mega-funds push capital into AI, some of the best talent is being allocated to frontier research. But this creates gaps in application-building talent

- Ecosystem growth: Massive capital in AI creates ecosystem effects: better infrastructure, more tools, more potential customers

- Founder-friendly markets: In competitive funding environments, founders have leverage over investors

Risks:

- Valuation compression: If growth moderates, valuations won't sustain current multiples. Today's mega-round might become tomorrow's cautionary tale

- Consolidation pressure: As mega-funds concentrate capital, smaller companies face pressure to get acquired or raise at down rounds

- Talent wars: The concentration of capital in frontier research means application companies struggle to hire experienced talent

- Market timing risk: If you're building an AI startup at the peak of hype, you're vulnerable to the inevitable correction when growth moderates

Strategic Recommendations:

- Focus on defensible metrics: Don't just chase growth. Focus on unit economics, customer retention, and profitability

- Build real products: Not just AI wrappers. The companies that survive will be those that genuinely improve customer outcomes

- Diversify revenue: Don't be entirely dependent on one customer or use case

- Maintain capital discipline: In capital-abundant markets, it's easy to overspend. Conservative founders often outperform in downturns

Section 20: Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The Biggest Takeaway: AI Funding Is Rationalizing, Not Speculating

If you've read this far, the central thesis should be clear: many of the mega-rounds and mega-fund announcements that seem speculative actually make rational sense when you examine the fundamental metrics. Anthropic at

This doesn't mean all valuations are rational. It means that some of the mega-round activity is based on legitimate growth assumptions rather than pure speculation. The market has learned from previous booms and is pricing AI companies more rationally than some of the most speculative dot-com or crypto plays.

But this also means venture returns are constrained. The mega-valuations leave less upside for subsequent investors. If Anthropic is worth

The Second Major Insight: Competitive Consolidation Is Underway

Open AI's erosion of competitive advantage, Cursor's vulnerability to Anthropic's Claude Code, and the overall winner-take-most dynamics in AI suggest we're entering a consolidation phase. The companies that achieved scale and locked in customers in 2024-2025 will dominate the next 5-10 years. The companies that failed to achieve critical mass are likely to be acquired or fail.

This has implications for venture returns. The mega-funds deployed in 2025 are betting on companies that achieve dominant positions. If concentration increases, returns for market leaders are excellent. But returns for second and third-place companies compress dramatically.

The Third Insight: Regulation and Geopolitics Are Underpriced Risks

Most venture capital analysis treats AI regulation and international competition as secondary factors. But both could materially impact venture returns:

- Regulation could constrain the addressable market or create competitive advantages for established players

- Geopolitics could split the AI market along national lines, reducing TAM for Western companies

- Open-source development could commoditize frontier models faster than expected

Investors in mega-funds should stress-test their returns against these scenarios.

What This Means for Capital Allocation in 2025 and Beyond

The AI funding boom is real, justified by genuine TAM expansion and technical breakthroughs. But it's also creating a bifurcated venture market:

- Mega-fund capital (A16z, Sequoia, Khosla) is concentrated in 10-20 companies that have achieved scale and demonstrate frontier capabilities

- Traditional venture capital is increasingly focused on later-stage or application-focused AI companies

- Smaller funds and micro-VCs are being starved of deal flow and competitive advantage

This concentration will likely persist. The mega-funds will continue to return excellent results for their LPs. Smaller funds will struggle to compete unless they have specific theses or access to deal flow that mega-funds don't.

For builders and developers, the key is to focus on building defensible products with real customer value rather than chasing funding narratives. The companies that will succeed long-term aren't those that raise the most capital—they're those that build solutions that customers genuinely value.

A Final Thought: We're Still in the Early Innings

Despite the mega-rounds, the mega-funds, and the stratospheric valuations, the AI market is still early. Frontier models continue improving. New applications and use cases are emerging constantly. The infrastructure continues being built out. And the regulatory environment is still taking shape.

For venture investors, this is both a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that the market is large enough that multiple companies can achieve multi-billion-dollar valuations. The curse is that competitive intensity will increase, growth will moderate, and valuations that seem reasonable today may seem expensive in retrospect.

The venture capital that gets deployed in 2025-2026 will determine the shape of AI markets for the next decade. Getting the bets right matters enormously. Getting the valuations right is equally important. And understanding the fundamental metrics—revenue growth, market TAM, competitive dynamics—is the only rational way to navigate this uncertainty.

The AI funding boom is real. Whether it produces exceptional venture returns or disappointing returns depends on execution by founders, strategy by investors, and whether the market dynamics play out as anticipated. The good news: the fundamentals are sound. The risk: assumptions about growth, regulation, and competition could prove wrong, with major implications for returns.

FAQ

What makes Anthropic's $350 billion valuation justified?

Anthropic's valuation becomes rational when you examine their growth metrics and revenue multiples. The company has grown from

How does Claude's dominance affect Open AI's market position?

Open AI's competitive position has eroded significantly as Anthropic's Claude emerged as the preferred model in enterprise and developer circles. Three years ago, Open AI had a 10:1 competitive advantage over Anthropic. Today, that ratio is approximately 2:1, meaning Anthropic has closed 80% of the competitive gap in just three years. This is evidenced by major applications (Cursor, Lovable, Replit) being built primarily on Claude rather than GPT-4, and enterprise customers showing stronger preference for Anthropic's models in production deployments.

Why is a $15 billion mega-fund mathematically sensible in AI?

Mega-funds make mathematical sense if deployed in mega-rounds at companies destined for billion-dollar valuations. A

What competitive risks does Cursor face from Anthropic?

Cursor faces significant existential risk because Anthropic, their primary model supplier, is launching Claude Code—a direct competitor in the developer productivity space. While Cursor has currently maintained customer preference due to superior UX and integration depth, Anthropic has unlimited resources, access to better models, and the ability to restrict API access or deprioritize Cursor in model improvements. The long-term survival of Cursor depends on maintaining feature parity or superiority and building customer lock-in through switching costs that overcome Anthropic's structural advantages.

How does California's wealth tax affect AI startup funding ecosystems?

California's wealth tax (approximately 2-4% annually on net worth above

What percentage of AI pilots convert to enterprise production deployment?

Historical data from enterprise IT adoption suggests that only 20-30% of pilot programs convert to full production deployment. This creates a revenue recognition challenge for AI platforms: a typical pilot might generate

How does open-source AI development affect proprietary model company valuations?

Open-source models (particularly Meta's Llama series) are rapidly closing the gap with proprietary frontier models. Llama 2 achieved 85% of GPT-4 quality, while Llama 3 is estimated at 90-95% of frontier performance. If this trajectory continues, open-source models will achieve parity with proprietary models within 2-3 years, which would compress pricing power and create commoditization pressure on companies like Anthropic and Open AI. However, proprietary companies maintain advantages in deployment optimization, reliability, support infrastructure, and continued frontier improvements that may sustain premium pricing even as open-source quality approaches parity.

What geopolitical risks exist in the AI funding landscape?

The emergence of frontier-quality AI models from Chinese companies (Byte Dance, Alibaba) and potential China-West bifurcation of the AI market represents a material but often-overlooked risk. If China restricts adoption of Western AI models or Western models cannot operate in Chinese markets due to regulatory requirements, the addressable market for Anthropic, Open AI, and others contracts by 15-25%. Additionally, if China achieves technical leadership in specific AI applications (e-commerce, content moderation for Asian languages), the global market consolidates differently than anticipated, with reduced TAM for Western companies.

How do talent costs affect AI company profitability and valuation?

The emergence of

Key Takeaways

-

Anthropic's $350B valuation is rational based on growth metrics, trading at 17x revenue multiples comparable to other high-growth frontier companies like Cloudflare and Palantir

-

Open AI faces genuine existential competitive risk as Anthropic has closed an 80% competitive gap in just three years, eroding Open AI's historical 10:1 advantage

-

Claude has functionally won enterprise AI with clear developer preference, dominant ISV partnerships (Cursor, Lovable, Replit), and superior production deployment metrics

-

Cursor faces strategic vulnerability as their primary model supplier (Anthropic) launches competing products, though UX differentiation and customer lock-in offer survival paths

-

**A16z's

100B+ valuations -

California's wealth tax triggers founder exodus reducing venture ecosystem concentration and bifurcating innovation between California (research) and Texas/Florida (commercialization)

-

Enterprise AI adoption faces pilot-to-production conversion challenges with only 20-30% of pilots deploying to full enterprise scale, requiring 3-5x pipeline for growth

-

Regulatory and geopolitical risks are underpriced in venture valuations, with potential market bifurcation and open-source commoditization affecting long-term returns

-

Talent cost inflation compresses margins with researchers commanding $10-20M packages, creating cost structures requiring massive scale for profitability

-

The AI market is still early but consolidating rapidly with mega-fund capital concentrating in 10-20 companies destined for dominance, leaving limited upside for secondary players