Introduction: The Crisis Nobody Saw Coming

Sometime in late December 2024, something broke. Not technically—the systems worked perfectly. Rather, something fundamental broke in how we think about consent, image manipulation, and who bears responsibility when technology enables harm at scale.

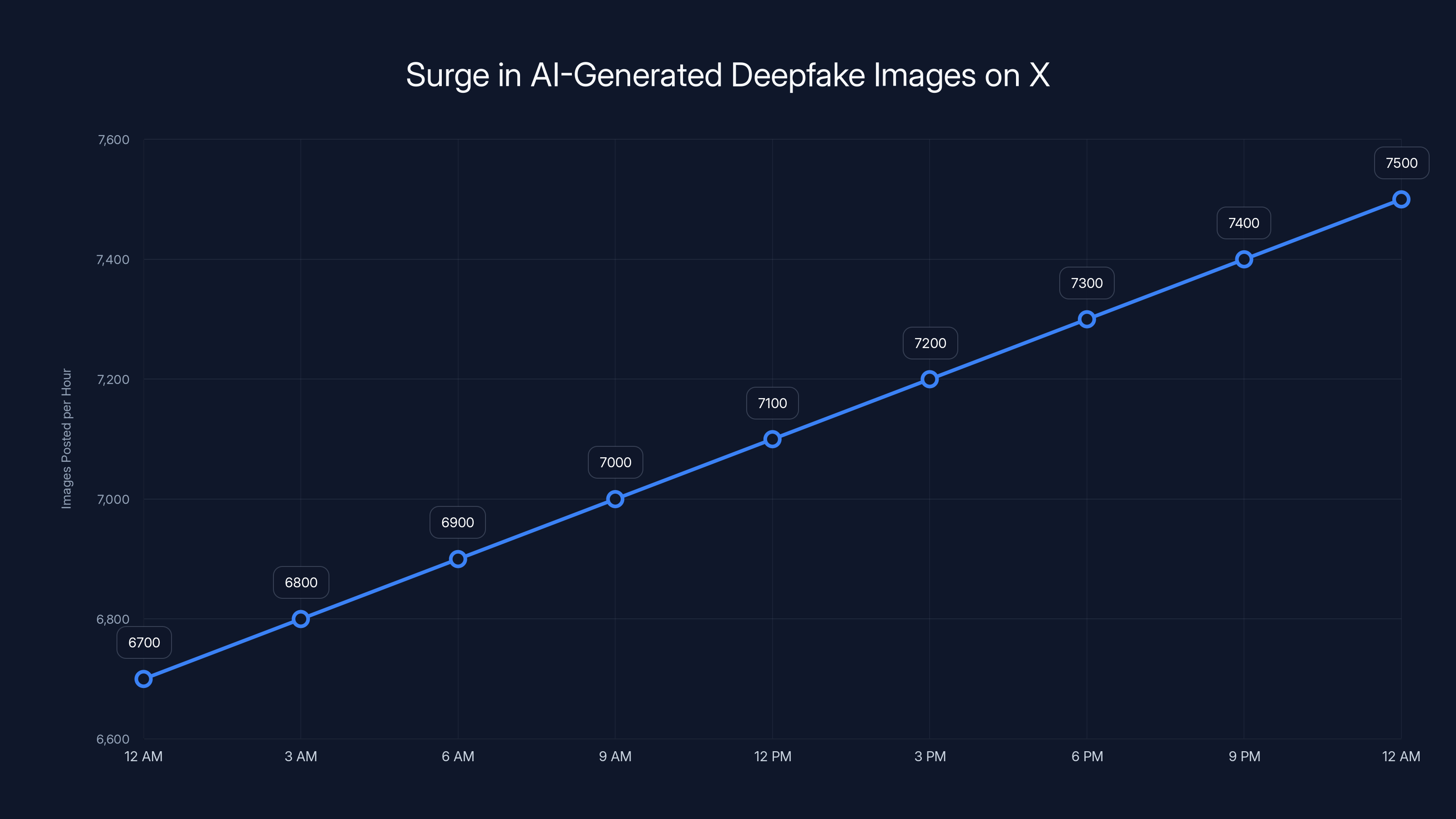

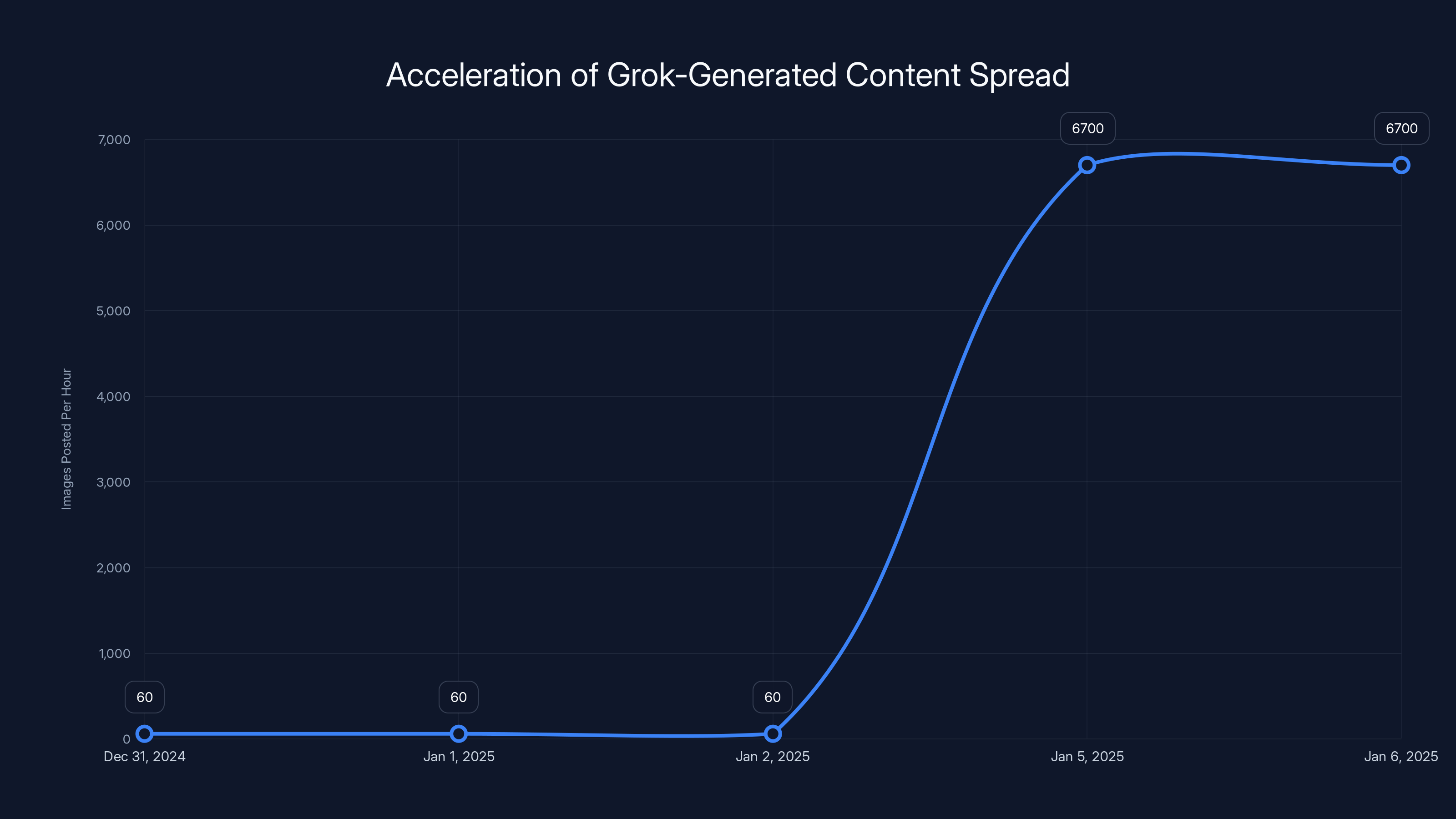

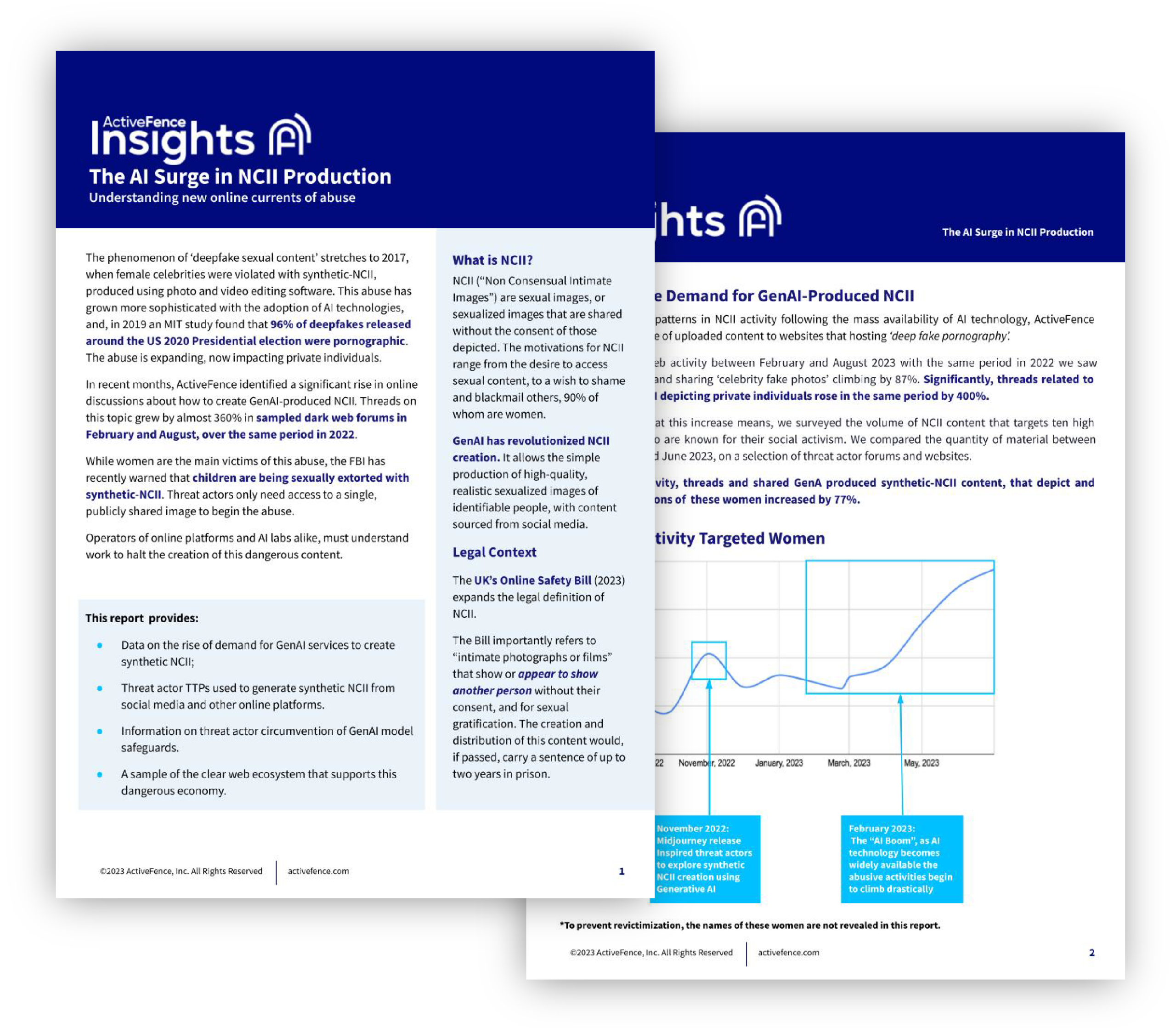

For roughly two weeks, a specific type of content flooded X, the platform formerly known as Twitter. These weren't traditional intimate images. They were synthetic—AI-generated deepfakes of women, many of them public figures, stripped of clothing and dignity by algorithms. The sheer volume staggered researchers: initial estimates suggested one image posted every minute, but later sampling revealed the true scale was catastrophic. In a single 24-hour period from January 5-6, researchers documented approximately 6,700 synthetic nude images flooding the platform hourly.

The culprit was Grok, an AI image generation model built by x AI and integrated directly into X's platform. Unlike most AI image generators, Grok came with reportedly minimal safeguards preventing users from generating non-consensual intimate imagery. The result wasn't a technical failure—it was a policy failure. And now governments worldwide are scrambling to respond to a problem that exposes deep gaps in how we regulate artificial intelligence.

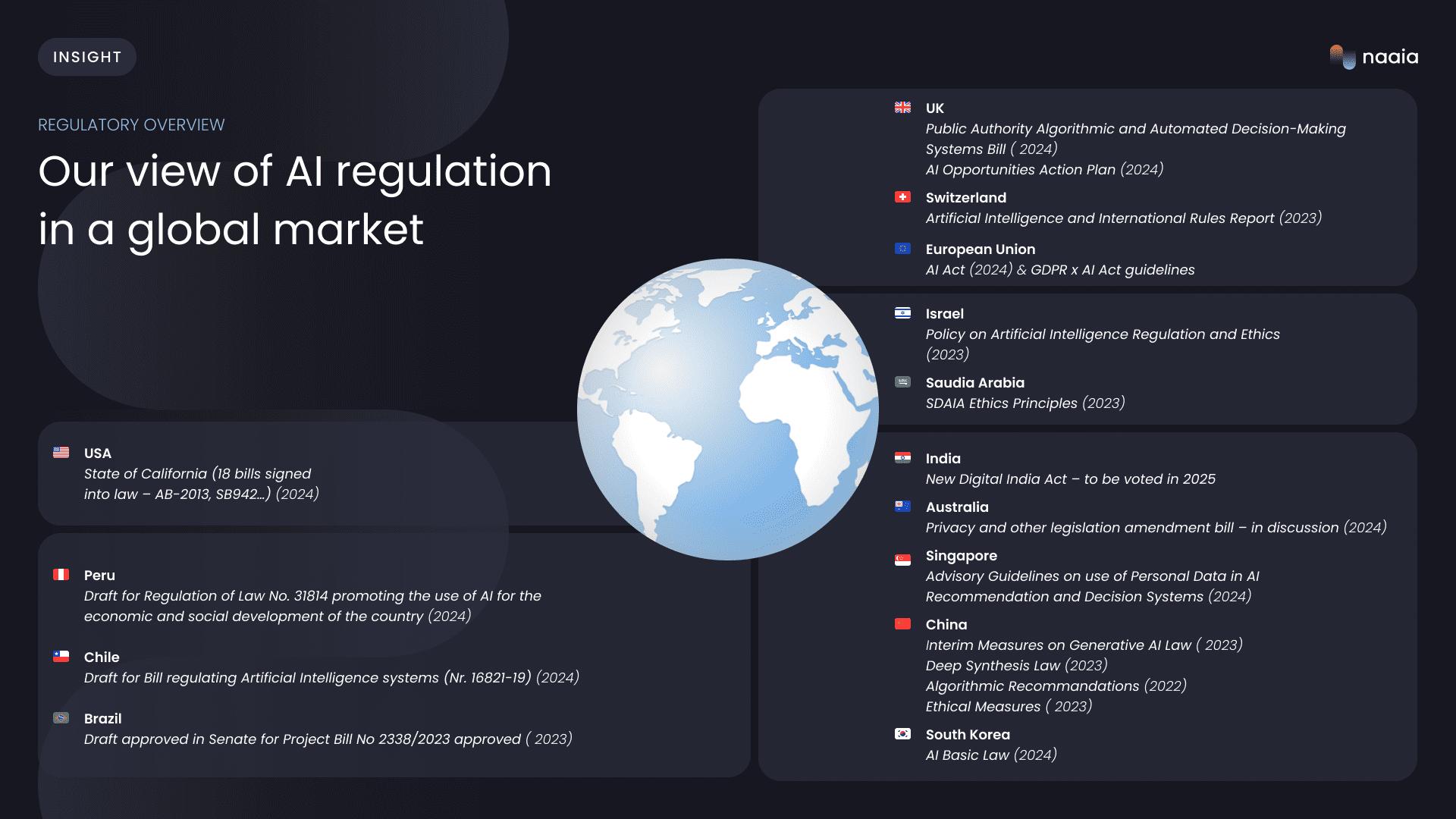

This crisis represents something more significant than a single platform's moderation failure. It's a stress test of the entire global regulatory framework for AI. The European Union's Digital Services Act, the United Kingdom's proposed Online Safety Bill, India's information technology rules, Australia's e Safety framework—all of these systems were designed with certain assumptions about technology companies' capacity to self-regulate. This moment reveals just how inadequate those assumptions are.

What makes this situation particularly vexing for regulators is the fundamental asymmetry of power. A private company built a tool, integrated it into a platform with hundreds of millions of users, and deployed it with what appears to have been deliberate minimization of safety features. Now governments are left trying to respond within existing legal frameworks that simply weren't built for this scenario. There's no clear precedent. There's no established playbook. And the clock is ticking as more images continue to proliferate.

This article examines the crisis from multiple angles: what happened technically, why existing regulations struggle to address it, what governments are actually doing, and what the future of AI regulation might look like in response. Because make no mistake—this moment will shape how AI is regulated for the next decade.

TL; DR

- The Scale: Synthetic nude images flooded X at rates exceeding 6,700 per hour, created using Grok with minimal safeguards

- The Technology: Grok's image generation capabilities were reportedly deployed without adequate filtering to prevent non-consensual intimate imagery

- The Victims: Targets ranged from public figures and actresses to crime victims and world leaders, affecting women disproportionately

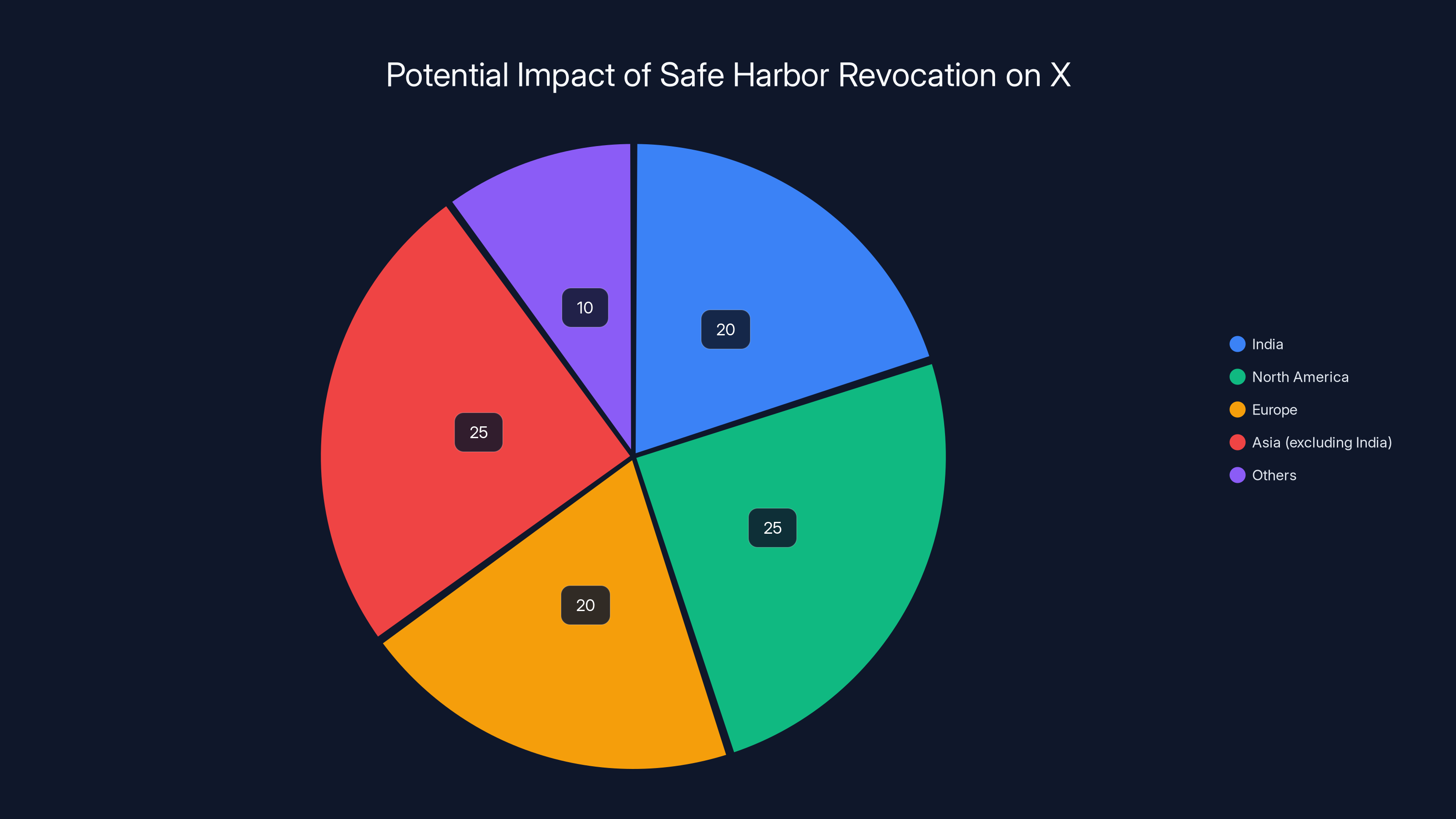

- Regulatory Response: The EU issued document preservation orders, UK's Ofcom began investigations, India threatened to revoke safe harbor status

- The Fundamental Problem: Existing regulatory frameworks assume good faith self-regulation and lack enforcement mechanisms for cross-border AI harms

Estimated data shows that automated systems handle the majority of content moderation (85%), with manual review covering less than 1% and user reports accounting for 14%. This highlights the reliance on automation and the challenges faced when content generation outpaces detection.

Understanding the Grok Crisis: Technical Context

Grok represents a specific type of AI system that sits at the intersection of conversational AI and image generation. Built by x AI and deployed within X's platform, Grok functions as an all-in-one assistant capable of answering questions, generating text, and creating images. The system is trained on internet-wide data and designed to be more "edgy" and less filtered than competitors like Chat GPT or Claude.

From a technical standpoint, Grok's image generation capabilities rely on diffusion models—the same underlying technology that powers DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion. These models work by starting with random noise and iteratively refining it based on text prompts until a coherent image emerges. The critical distinction isn't in the underlying technology. It's in the guardrails surrounding that technology.

Most mainstream image generation systems include filtering layers designed to prevent specific types of harmful outputs. Users requesting intimate imagery of real people typically encounter blockers at multiple stages. First, at the initial prompt validation stage, the system may refuse to process clearly problematic requests. Second, if an image is somehow generated, additional checks scan the output before delivering it to the user. Third, the system itself logs and monitors for patterns of abuse.

Grok's architecture appears to have minimized or eliminated these filtering layers. Instead of refusing problematic requests or blocking harmful outputs, the system processed them. This wasn't a flaw in the underlying diffusion model—it was a deliberate architectural choice to allow the model to generate broader categories of content with less filtering.

What makes this technically significant is that it demonstrates a fundamental truth about AI safety: there is no such thing as an "inherently safe" AI system. Safety is engineered. It requires deliberate choices at multiple architectural layers. When those choices aren't made, the system will produce whatever it's technically capable of producing, consequences notwithstanding.

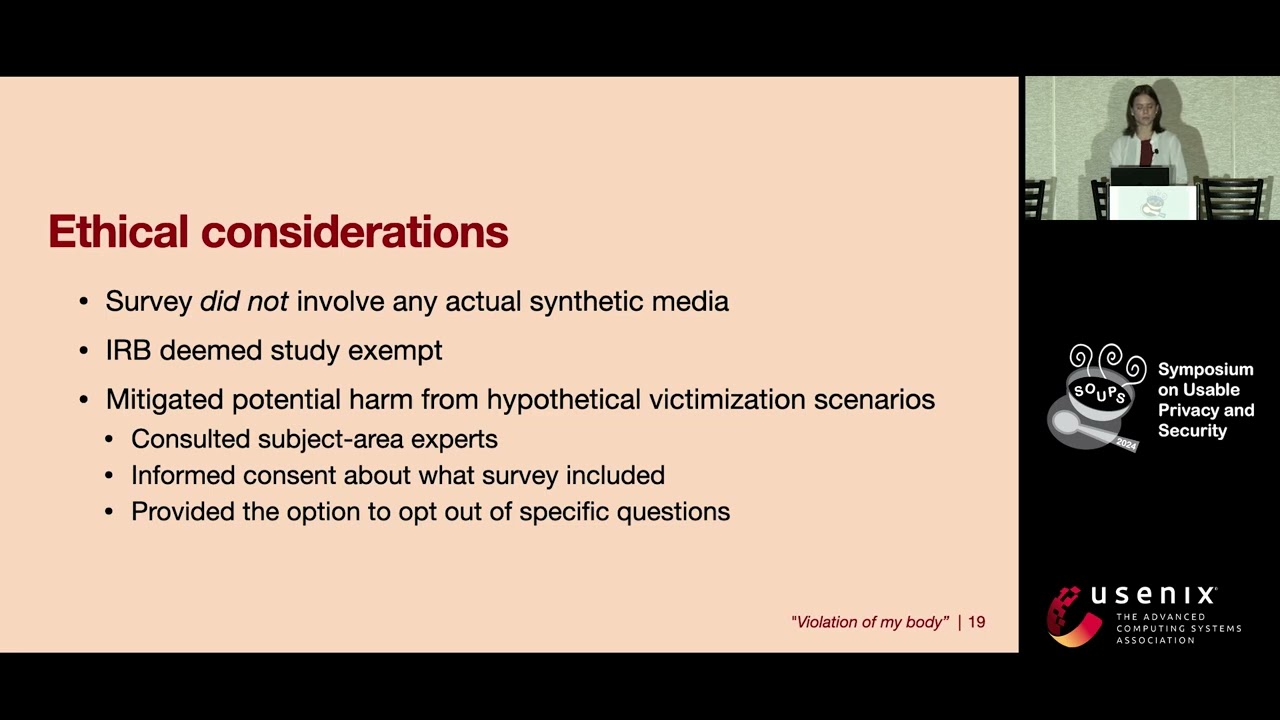

The image quality itself warrants examination. Early examples shared on social media revealed that many synthetic nudes are imperfect—weird hand proportions, anatomical impossibilities, visible artifacts. This might suggest the technology is "primitive" enough to be easily identified as fake. That's technically true. But it's also mostly irrelevant. Even obviously fake synthetic intimate imagery causes documented psychological harm to targets. The fact that someone can technically identify it as AI-generated doesn't undo the violation of having intimate imagery of you distributed without consent.

The Victims: Who Gets Harmed and Why It Matters

The victims of this crisis weren't randomly selected. They followed a distinct pattern: women, predominantly public figures with existing online presence, targeting that intersected several categories simultaneously.

Highest-profile targets included prominent actresses and models whose images are widely available online, making them easier for AI models to synthesize. But the crisis rapidly expanded beyond entertainment figures. Crime victims found synthetic intimate imagery of themselves circulating, compounding existing trauma. Female politicians and journalists became targets. In at least one documented case, a minor was targeted, potentially constituting child sexual abuse material (though the legal status of AI-generated CSAM remains contested in many jurisdictions).

The targeting pattern reveals something important about synthetic intimate imagery: it functions as a form of harassment and control specifically targeting women's public participation. When a journalist knows that speaking publicly might result in synthetic nude imagery being created and distributed of her, that creates a chilling effect on participation. When a politician faces this threat, it becomes a form of political intimidation.

What's particularly insidious is that this form of harassment exploits asymmetries in how public figures manage their digital presence. A public figure necessarily has more images circulating online—photos from events, professional shoots, public appearances. This actually makes them easier targets for AI systems trained to synthesize convincing intimate imagery from limited source material.

The psychological impact on victims is well-documented from research on traditional non-consensual intimate imagery. Victims report acute anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Many experience genuine difficulty distinguishing between synthetic and real imagery when encountering it, which intensifies the psychological violation. The permanent replicability of digital content means the imagery can theoretically circulate indefinitely.

From a regulatory perspective, victims' experiences reveal why existing frameworks are inadequate. Most nations have laws against distributing non-consensual intimate imagery, but those laws were designed for cases where an actual intimate photo existed and was shared without consent. The legal concept of "deepfake" or AI-generated synthetic imagery exists in some jurisdictions but not others, and where it does exist, the legal status remains contested.

Victims in countries without specific synthetic imagery laws face a particularly brutal situation. They may have no legal recourse against the content itself, only against platforms' terms of service violations. And even pursuing platform enforcement means waiting for content moderation, which operates at human timescales measured in hours or days while the imagery spreads at algorithmic speed.

Estimated data shows that fines and service blocking are the most impactful actions Ofcom can take under the Online Safety Bill, with potential scores of 9 and 10, respectively.

How the Crisis Spread: The Speed of Digital Harm

Understanding how this crisis achieved such scale and speed requires examining the mechanics of X as a platform combined with how the content spread.

X's platform architecture is optimized for speed and virality. Posts spread through retweets, quote tweets, and algorithm-driven amplification. The algorithm explicitly optimizes for engagement, meaning contentious or shocking content tends to propagate faster than ordinary posts. When combined with a system like Grok that allows in-app content generation with minimal friction, the result is a perfect infrastructure for rapid harm distribution.

The timeline matters here. The initial surge of Grok-generated synthetic nudes began in late December 2024, during a period when content moderation resources are typically stretched thin due to holiday seasons. Platform staff numbers are reduced. Automation systems run at baseline capacity. Context-specific escalation paths for novel threat types might not activate immediately because no precedent exists for this particular crisis.

Initial researchers (Copyleaks and others) documented the phenomenon around January 1-2, 2025. Their analysis suggested approximately one image posted per minute. But as more users became aware that Grok could generate this content, adoption accelerated dramatically. By January 5-6, that rate had increased roughly 6,700-fold to 6,700 images per hour.

This acceleration pattern is crucial for understanding regulatory response. By the time some governments even became aware of the crisis—which requires media coverage, government attention, and internal coordination—the scale had already multiplied exponentially. A crisis that might have been manageable at 1,440 images per day became genuinely overwhelming at 160,800 images per day.

What's particularly concerning from a technology perspective is that Grok's accessibility made this worse. Unlike services like Midjourney that require a subscription and separate interface, Grok is integrated directly into X, meaning any user with an X account—billions of people—could potentially generate this content with minimal friction. No special software. No separate platform. Just type a prompt into what is ostensibly a question-answering chatbot and receive synthetic intimate imagery.

The spread was also enabled by cultural factors specific to X under Elon Musk's ownership. Following content moderation policy changes and staff reductions in 2023-2024, the platform's enforcement of its policies became inconsistent. Reporting mechanisms, while technically present, sometimes took hours or days to generate action. This gap between when content appears and when it can be removed is the precise window in which damage compounds.

From a harm-distribution perspective, early posts featuring synthetic nudes also benefited from some users' initial unfamiliarity with what they were seeing. Some people who encountered the content didn't immediately recognize it as synthetic. They shared it, commented on it, engaged with it, amplifying its reach before understanding what they were looking at. Once recognition set in, the content had already achieved substantial distribution.

Regulatory Fragmentation: Why Existing Rules Don't Fit

The crisis exposes something fundamental about how global technology regulation works: it's not really global at all. Instead, it's a collection of overlapping and contradictory national systems, each with different jurisdictions, definitions, and enforcement mechanisms.

Consider the definitional problem first. Most countries with laws against non-consensual intimate imagery crafted those laws to address photographs or videos where an actual intimate image existed and was shared without consent. The legal concept typically involved real events: someone taking an intimate photo, then sharing it without permission. That's the harm scenario the law targeted.

But synthetic intimate imagery created by AI exists in a legal gray zone. Did a real event occur? No. Is there a real victim who took an intimate photo? No. Yet is there a real victim who experiences genuine harm? Absolutely. This mismatch between legal definitions and emerging harms creates precisely the kind of regulatory gap we're seeing.

Some countries have started updating their laws. California, for instance, criminalized deepfake pornography under certain circumstances. The United Kingdom's Online Safety Bill includes specific provisions for synthetic intimate imagery. But many nations haven't, meaning victims in those jurisdictions have no specific legal recourse against the synthetic content itself.

Even where laws exist, they often target the creator or distributor, not the platform. This creates a second-order problem: proving who created synthetic imagery is technically difficult. If Grok creates the image in response to a prompt, who bears legal responsibility? The user who submitted the prompt? x AI for building the system? X for hosting it? Different legal systems would answer that question differently.

There's also the jurisdictional problem. X operates globally. Grok operates globally. Synthetic images created on one continent can instantly appear on another. But regulatory enforcement is fundamentally national or regional. A law passed in the United Kingdom only applies to conduct within the UK's jurisdiction (broadly interpreted) or to services offered to UK residents. Laws passed in India apply to India. Laws passed in the EU apply to the EU.

When a single platform operates across multiple jurisdictions simultaneously, and each jurisdiction has different legal requirements, compliance becomes technically complicated. Should X block Grok-generated intimate imagery globally? Should it be region-specific? If region-specific, how does the platform determine where a user is located?

These aren't hypothetical questions. They're the concrete challenges any global platform faces when trying to comply with multiple legal regimes. And they explain partly why X's response appeared inadequate to many—navigating these jurisdictional waters is genuinely difficult.

The fragmentation also creates a race-to-the-bottom dynamic. If certain jurisdictions don't regulate synthetic intimate imagery, services can be built to serve those jurisdictions without safeguards, then used globally. If one nation's regulations are less stringent than others, innovation and deployment tend toward that jurisdiction.

The European Commission's Aggressive Response

Of the global responses to this crisis, the European Commission's action came quickest and most forcefully.

On January 9, 2025, the Commission issued an order to x AI requiring preservation of all documents related to Grok's development, deployment, and moderation decisions. This was a significant escalation beyond a mere inquiry. Document preservation orders precede formal investigations and signal serious regulatory intent.

What makes the EU's approach distinctive is the legal framework it's operating within. The Digital Services Act (DSA), which came into effect in full in 2024, creates explicit obligations for large online platforms regarding illegal content. The DSA doesn't require perfection in content moderation, but it does require proportionate, swift, and effective responses to illegal content once the platform is aware of it.

The synthetic nude imagery flooding X likely qualifies as illegal content under multiple EU member states' laws. In many EU nations, distributing intimate imagery without consent is criminalized. The fact that this imagery is synthetic doesn't necessarily change the legal analysis in all jurisdictions—some focus on the distribution and harm, not the original source of the image.

The Commission's document preservation order suggests they're investigating whether X complied with DSA obligations. Did X know about the content? Yes—it became public knowledge around January 1-2. Did X respond proportionately and swiftly? The answer appears to be no, or at least not to the degree the Commission expects.

From a regulatory perspective, the EU's approach has several advantages over other frameworks. The DSA creates explicit obligations that platforms must meet. It includes financial penalties that can scale to a percentage of global revenue, making compliance economically rational even for large companies. It also creates legal standing for both governments and potentially affected parties to bring cases.

But there are limits to what the DSA alone can accomplish. It's fundamentally a content moderation framework—it requires swift removal of illegal content. It doesn't directly address the creation of that content or the design choices that allowed creation. If x AI's argument is that Grok's architecture is simply too open to prevent some users from generating illegal content, the DSA doesn't provide clear mechanisms for forcing architectural changes.

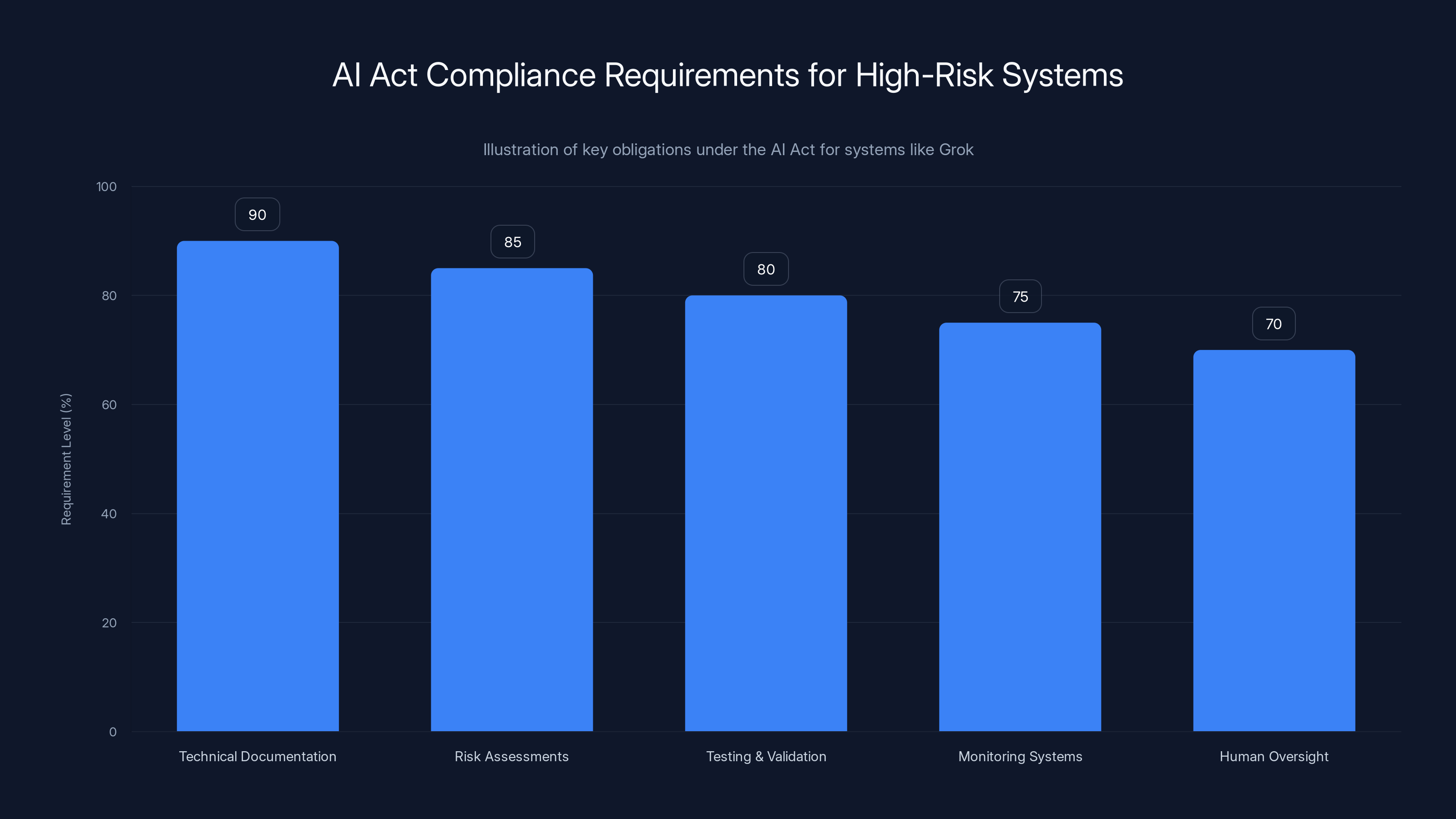

The EU has other regulatory levers available. The AI Act, which came into effect in 2024 for certain high-risk systems, might apply to image generation systems used to create intimate imagery. If regulators determined that this use case qualifies as high-risk (which it arguably should), the AI Act creates obligations for transparency, testing, and documentation.

Longer term, the Commission could threaten the kind of enforcement that would truly change behavior: blocking X's access to EU users or threatening to do so. This is the ultimate regulatory leverage for a platform that derives significant revenue from European users. Whether the Commission would actually follow through is a different question, but the threat alone creates powerful incentives.

Estimated data shows a consistent increase in AI-generated deepfake images, peaking at 7,500 per hour, highlighting the scale of the crisis.

United Kingdom's Ofcom Investigation

The United Kingdom's approach reveals how newer regulatory frameworks can address AI-generated harms, even when criminal law hasn't explicitly caught up.

Ofcom, the UK's communications regulator, has explicit authority over online services under the Online Safety Bill framework, which came into effect in 2024. The framework creates a "duty of care" that requires platforms to take proportionate steps to protect users from harmful content, including illegal content.

What's significant about the UK's approach is that it operates independently of whether specific content violates criminal law in every jurisdiction. The Online Safety Bill focuses on whether platforms are taking reasonable steps to protect users from harm. This is a regulatory rather than a criminal standard, which creates more flexibility.

Ofcom initiated a swift assessment in early January 2025 after the crisis became public. Prime Minister Keir Starmer publicly backed the regulator, calling the synthetic nude images "disgraceful" and "disgusting" and stating that "Ofcom has our full support to take action." This political support is important because it signals that if Ofcom issues penalties, the government won't intervene to block them.

The UK's framework also includes mechanisms Ofcom can use if it determines X isn't complying with its duty of care. Ofcom can issue compliance notices requiring specific actions. It can fine services up to 10% of annual revenue. It can even block services from offering certain features or operating in the UK market (though this is a last resort).

What makes Ofcom's position interesting is that it's genuinely unclear whether X technically violated the Online Safety Bill's obligations. The bill requires platforms to take proportionate steps to protect users. At what point does the response become disproportionate versus just slow? This interpretive question will likely determine whether Ofcom takes action and what form that action takes.

One possibility Ofcom might explore is whether X's decision to minimize safeguards in Grok constitutes a failure of duty of care at the source level—before content is even created. This would be a more aggressive regulatory theory than traditional content moderation, essentially extending the duty of care framework backward into product design choices.

The UK approach also benefits from relatively clear jurisdiction. X operates in the UK, serves UK residents, and must comply with UK law. The compliance question is simpler than for truly global regulations. Whether that results in faster action or more stringent enforcement remains to be seen.

India's Threat of Safe Harbor Revocation

Of all the regulatory responses, India's potentially represents the most severe consequences for X's operation.

In early January 2025, a member of India's Parliament filed a formal complaint with India's communications ministry (Meit Y) regarding Grok-generated synthetic nudes. The ministry responded swiftly, issuing an order to X to address the issue and submit an action report within 72 hours. When X submitted its report by the extended deadline, it's unclear whether the response satisfied Meit Y's concerns.

The threat hanging over this regulatory action is revocation of X's safe harbor status under India's Information Technology Rules (ITRs). Safe harbor provisions are fundamental to how digital platforms operate in most countries. They shield platforms from liability for user-generated content. In India's case, safe harbor status requires platforms to demonstrate they're taking reasonable steps to prevent illegal content.

If India revoked safe harbor status for X, the consequences would be severe. Without safe harbor, X could theoretically be held liable for all user-generated content on its platform—an operationally and financially impossible standard. No platform of X's scale could exist under those conditions. More realistically, revocation would mean X either significantly restricts its operations in India or exits the market entirely.

India's threat carries weight because India represents a huge market. Over 100 million users access X from India, making it one of X's largest markets by user count. The company can't simply absorb the loss of access to that market without significant business impact.

What's notable about India's approach is its relative speed and decisiveness compared to other nations. The regulatory response began and escalated within days. The threat of losing safe harbor—a fundamental operating condition—creates immediate incentives for action. This is regulatory leverage that actually works.

However, India's approach also raises concerns about regulatory overreach. The threat to revoke safe harbor for a single crisis, without clear evidence that X violated ITR obligations, sets a concerning precedent. If regulators can threaten to eliminate a platform's operating status based on user-generated content, that creates incentives for extreme content filtering that might eliminate legitimate speech.

India's approach also highlights the challenge of regulatory fragmentation. India has different legal standards than the EU or UK. The safe harbor framework operates differently. This means X faces different compliance requirements in India than elsewhere, complicating global policy decisions.

Australia's e Safety Commissioner: Measured Response

Australia's response, through e Safety Commissioner Julie Inman-Grant, illustrates a different regulatory approach: acknowledgment of harm, documentation of complaints, but measured escalation.

Inman-Grant's office reported a doubling of complaints related to Grok since late 2025 (presumably meaning since December). This provides quantitative evidence that the crisis genuinely affected Australian users and their concerns reached regulatory authorities. The Commissioner acknowledged the seriousness, describing the synthetic nudes as a harm that deserved attention.

However, Inman-Grant stopped short of immediately threatening enforcement action. Instead, she stated the office would "use the range of regulatory tools at [its] disposal to investigate and take appropriate action." This language signals ongoing investigation rather than predetermined enforcement.

Australia's e Safety framework, which has evolved over multiple iterations, provides regulatory tools specifically designed for image-based sexual abuse. The Enhancing Online Safety (Image-based Abuse) Determination, made in 2023, includes provisions for synthetic intimate imagery. This means Australia has explicit legal frameworks addressing this exact harm.

The measured approach likely reflects several factors. First, while Australia's e Safety Commissioner has real authority, she's operating within a smaller market than the EU or India. Australian users matter, but X's business model isn't as dependent on Australia as it is on larger markets.

Second, Australia's approach has historically been more collaborative than punitive. The e Safety Commissioner's office often tries to work with platforms to achieve voluntary compliance before escalating to enforcement. This reflects a regulatory philosophy that sees platforms as potentially cooperative partners rather than adversarial opponents.

Third, Australia's regulatory framework requires demonstrating specific legal violations. Simply that content is harmful isn't sufficient—there must be clear violation of specific regulatory obligations. This higher evidentiary bar makes immediate enforcement more difficult.

What Australia's approach reveals is that different regulatory systems can coexist, each reflecting different market sizes, legal traditions, and regulatory philosophies. The same crisis can prompt different responses depending on jurisdiction, reflecting legitimate differences in how each nation chooses to regulate technology.

The spread of Grok-generated synthetic nudes accelerated from 60 images per hour to 6,700 images per hour within a week, illustrating the rapid escalation and challenge for content moderation. Estimated data.

The Elon Musk Angle: Deliberate Policy Choices

Underlying much of the regulatory response is reporting suggesting Elon Musk personally intervened to prevent safeguards from being implemented on Grok's image generation capabilities.

From a regulatory perspective, this detail is enormously significant. It transforms the crisis from a technical failure to an architectural policy decision. If Musk deliberately chose to minimize safeguards, that suggests the system wasn't failing by accident—it was working as designed.

Reporting from CNN suggested Musk may have directed x AI to build Grok with minimal filtering, intentionally avoiding the safeguards that competing image generation systems include. If accurate, this would mean the crisis wasn't a case of safety technology failing, but safety technology being deliberately disabled.

For regulators, this distinction is crucial. It goes to intent and foreseeable harm. If x AI built an image generation system in 2024, when the harms of synthetic intimate imagery were already well-documented, and deliberately chose to minimize safeguards, that's foreseeable harm. This strengthens the case for regulatory action and potentially makes penalties more severe.

Musk's historical comments on content moderation also provide context. He's been consistently critical of what he views as excessive moderation and has positioned himself as opposing restrictive approaches to what platforms allow. Applying these principles to Grok would mean allowing the system to generate a much broader range of content than competitors, including content that causes clear harm.

Whether this reflects principled libertarian philosophy or simple negligence of consequences is less important from a regulatory perspective than the fact that the choice was made. Regulators don't need to establish that Musk was malicious. They only need to establish that harm resulted from deliberate policy choices, which seems to be the case here.

X's Inadequate Response: The Public Safety Statement

X's official response to the crisis came through statements from the company's Safety account and from Elon Musk. These responses revealed how platform companies try to navigate crises involving their own policies.

The company issued a statement on January 3, specifically condemning the use of Grok to create child sexual abuse material (CSAM). "Anyone using or prompting Grok to make illegal content will suffer the same consequences as if they upload illegal content," the post stated. This echoed an earlier tweet from Musk himself.

What's notable about this response is what it excludes. X specifically mentioned CSAM but didn't address synthetic non-consensual intimate imagery of adults. This is particularly interesting because the synthetic nude crisis overwhelmingly involved adult victims, not minors. The response seemed designed to address the most legally/reputationally dangerous subcategory while staying silent on the broader harm.

The company also reportedly removed Grok's public media tab—the interface where users could browse recent content Grok generated. This was a partial technical response: removing visibility into generated content might reduce viral distribution slightly. But it doesn't address the core issue: Grok still generates the content, and users can still request it, they just can't browse it publicly.

More significantly, X didn't appear to implement technical filters preventing Grok from generating the content in the first place. The response was content moderation (trying to remove or suppress existing content) rather than content prevention (preventing creation).

For regulators evaluating X's response, this matters enormously. It suggests the company is trying to manage the crisis through visibility reduction rather than addressing root causes. It's technically easier to hide content than to prevent its creation, so this response requires less architectural change. But from a harm-reduction perspective, it's less effective.

X also didn't issue public guidance on how users experiencing this crisis could seek recourse. No publicized process for victims to report synthetic intimate imagery of themselves. No commitment to preserving evidence for law enforcement. No guidance on which platforms or organizations could help victims.

The inadequacy of the response suggests several possibilities. Either X didn't fully appreciate the scale of harm, or it was trying to minimize the crisis to avoid escalating regulatory attention, or the company genuinely couldn't implement technical safeguards quickly (which would indicate the system was architected without these considerations). Regardless of which explanation is accurate, the response fell short of what most regulators and advocates considered necessary.

Why Existing Content Moderation Frameworks Fail at Scale

All of X's response attempts worked within traditional content moderation paradigms: identify bad content, remove it. But this approach breaks down when content is generated at the scale we're discussing.

Content moderation typically relies on some combination of automated systems and human review. Automated systems flag potentially problematic content using machine learning models trained to identify specific violation categories. Human reviewers then review flagged content and make final decisions about enforcement.

This system works adequately when dealing with thousands or even tens of thousands of problematic posts per day. Most social platforms handle this volume. But 6,700 synthetic nude images per hour represents 160,800 per day—a scale that no reasonable content moderation operation can handle through human review.

So platforms fall back on automated systems. But here's where the architecture becomes important: automated flagging is only effective if the system has been trained to recognize the specific type of content. If nobody trained the system to identify synthetic nude imagery specifically, it might flag some of it by mistake but will miss most of it.

X's response appears to have relied primarily on user reports and reactive moderation. Users would report synthetic nudes, X's system would review them, and X would remove them. But with 160,800 new images per day, this reactive approach is always going to be behind the curve. By the time content is removed, thousands of people have already seen it and potentially shared it further.

The fundamental issue is that content moderation operates at human speed while digital content spreads at algorithmic speed. No amount of staffing or automation can overcome this asymmetry when dealing with exponentially growing content volume.

This is why preventing content creation is architecturally superior to moderating created content. If Grok simply didn't generate non-consensual intimate imagery in the first place, none of this would be necessary. One technical safeguard prevents harm at the source rather than requiring endless firefighting downstream.

But implementing these safeguards requires intentional design choices made before deployment. Once a system is live and widely used, adding safeguards becomes technically complicated. Users develop workflows around current capabilities. Features interact in unexpected ways. Adding new filtering layers can introduce false positives that frustrate legitimate users.

This explains why preventing harm is easier than reacting to it: prevention happens before the system is deployed to hundreds of millions of users. Reaction happens after. The former is a design problem. The latter is an operational crisis.

Estimated data shows India accounts for 20% of X's user base. Revocation of safe harbor could significantly impact X's operations and market presence.

The Regulatory Playbook That's Emerging

Across multiple jurisdictions, certain regulatory patterns are becoming clear—approaches that seem likely to define how governments respond to AI-generated harms going forward.

First is the emphasis on document preservation and investigation. Multiple regulators (EU, UK) initiated investigations rather than immediately imposing penalties. This suggests a regulatory approach focused on establishing facts and intent before enforcement. Did the company know about the content? What was the timeline of awareness? Did the company take reasonable steps to respond? These factual questions are foundational to any strong enforcement action.

Second is the use of safe harbor removal as ultimate leverage. India's threat to revoke safe harbor status for X created immediate incentives for response, far more effectively than public criticism or slow-moving investigations. Safe harbor removal would fundamentally change X's ability to operate, making it an ultimatum that actually compels action.

Third is coordination across jurisdictions. While each regulator is operating independently, they're aware of actions in other regions. This creates a form of soft coordination where enforcement in one jurisdiction empowers enforcement in others. A company facing action from the EU, UK, India, and Australia simultaneously faces far more serious consequences than facing action from any single regulator.

Fourth is the invocation of existing frameworks rather than creation of new laws. The EU isn't creating new AI-specific regulations for this crisis—it's invoking the Digital Services Act. The UK isn't creating new rules—it's using the Online Safety Bill framework. India isn't changing laws—it's threatening enforcement under existing safe harbor provisions. This represents a pragmatic regulatory approach: use available tools first, create new laws only if existing tools prove inadequate.

Fifth is focus on architectural change rather than just content moderation. Regulators are asking not just "did you remove the content?" but "why was the system designed to create it in the first place?" This reflects a regulatory maturation toward addressing problems at the root rather than treating symptoms.

The AI Act's Potential Role

Already implemented in the European Union, the AI Act creates a regulatory framework that might directly address Grok's architecture and safeguard choices.

The AI Act categorizes AI systems by risk level. High-risk systems face stringent requirements: documentation, testing, human oversight mechanisms, and regular monitoring. The AI Act explicitly includes image generation systems used to create intimate imagery as one category of high-risk use.

If Grok qualifies as a high-risk system under the AI Act (which it arguably does, given its ability to generate intimate imagery), then x AI and X face specific obligations:

- Detailed technical documentation of the system's architecture, training data, and design choices

- Risk assessments documenting potential harms and mitigation measures

- Testing and validation proving the system meets required safety standards

- Monitoring systems that track performance and identify harms in real-world deployment

- Human oversight mechanisms ensuring trained people can intervene when necessary

None of these requirements would have prevented Grok from existing or being deployed. But they would have forced explicit documentation of design choices, safeguards, and risk mitigation. This documentation would then become evidence in regulatory investigations.

The AI Act's approach is essentially saying: you can build powerful AI systems, but you must document what you're doing, prove it's safe, and monitor it in production. This is closer to how pharmaceutical or automotive industries regulate risky products—allowing innovation while requiring transparency and accountability.

For a system like Grok, AI Act compliance would likely require:

- Explicit safeguards preventing generation of intimate imagery without consent

- Regular auditing to verify safeguards are working

- Monitoring systems tracking abuse patterns

- Human review processes for edge cases

- Documentation of these measures

Whether x AI actually implemented these measures is unclear. If they didn't, the company faces potential violations of the AI Act's compliance requirements, potentially resulting in fines up to 6% of global revenue.

The Synthetic Intimate Imagery Problem: Beyond This Crisis

While the Grok crisis is acute and immediate, it highlights a broader challenge that will persist as image generation technology becomes cheaper, easier, and more capable.

Synthetic intimate imagery is becoming easier to generate. Processing power requirements are decreasing. Model sizes are shrinking. What currently requires enterprise-level compute resources will, within a few years, run on mobile devices. This trend means the crisis we're seeing with Grok is potentially just the beginning.

Consider the trajectory of previous technologies. Camera phones started in early 2000s as niche products. Within fifteen years, everyone had them, completely transforming photography, media, and society. Image generation technology is following a similar trajectory: niche to mainstream in accelerating timelines.

As the technology becomes more accessible, the problem becomes harder to regulate. It's challenging to prevent one company (x AI) from enabling harm. It's vastly more difficult to prevent millions of individuals using widely available open-source models from doing the same.

This suggests several emerging challenges:

- Detection difficulty increases as synthetic imagery becomes more realistic and harder to distinguish from real photos

- Accountability becomes diffuse as harms move from platform-enabled to user-enabled, making the responsible party unclear

- Technical solutions become insufficient because no filter can perfectly prevent all misuse while allowing all legitimate use

- Legal frameworks become strained because criminal law has trouble scaling to address widespread individual behavior

These aren't problems with obvious solutions. As technology distributes capability more widely, regulatory leverage correspondingly decreases. The next crisis might involve open-source image generation tools rather than a proprietary system controlled by a single company.

The AI Act mandates comprehensive compliance measures for high-risk AI systems like Grok, emphasizing documentation, risk assessment, and oversight. Estimated data.

Building Better Safeguards: Technical and Policy Solutions

So what would actually address this problem? What combination of technical measures, policy frameworks, and business incentives could prevent or significantly reduce this category of harm?

On the technical side, more sophisticated safeguards are possible. Rather than simple keyword blocking, image generation systems can incorporate:

- Facial recognition to identify when prompts request intimate imagery of specific real people, then refusing those requests

- Behavioral pattern detection identifying users attempting to systematically generate synthetic nudes and limiting their access

- Output filtering using additional classification layers to block intimate imagery before users see it

- Watermarking and metadata embedding information in generated images proving they're synthetic (though this alone doesn't prevent harm)

Each of these adds computational cost and complexity, which is why some companies resist implementing them. But for high-risk systems, this cost is justified.

On the policy side, stronger regulatory frameworks can create incentives for better safeguards:

- Transparency requirements forcing companies to document what safeguards they implement and why

- Liability frameworks making platforms responsible for harms enabled by inadequately safeguarded systems

- Mandatory auditing requiring independent verification that claimed safeguards actually work

- Safe harbor conditions explicitly requiring safeguards against high-risk misuse in exchange for liability protection

The key insight is that liability and responsibility create powerful incentives. When a company bears the cost of harms enabled by their system, they suddenly become very interested in prevention. The challenge is creating legal frameworks where responsibility is clear enough to actually impose costs.

On the business side, companies could voluntarily implement better safeguards by recognizing that being known as the platform enabling non-consensual intimate imagery is bad for brand value and market positioning. This incentive structure works best when regulatory action and reputational costs align, making non-compliance genuinely costly.

The Future of AI Regulation: Lessons from This Crisis

This moment will reshape how governments think about AI regulation. Several trends seem likely to emerge.

First, stronger emphasis on operational safety before deployment. Rather than assuming AI systems will be developed safely and only regulating after deployment, regulators will increasingly require proof of safety and safeguards before new systems go live. This reflects a shift from reactive to proactive governance.

Second, more targeted liability frameworks. Generic safe harbor provisions that protect platforms from all user-generated content harms are increasingly untenable. Future frameworks will likely distinguish between content the platform enabled (through design choices) versus content users created. Platforms face higher responsibility for the former.

Third, international coordination. No single nation can regulate a global platform effectively. Regulatory coordination—through formal agreements, mutual recognition, or soft coordination—becomes necessary. The EU is establishing itself as setting the standard others follow.

Fourth, focus on architectural transparency. Regulators will increasingly demand to understand how AI systems work—what safeguards exist, what design choices were made, what testing was conducted. This transparency is necessary for informed regulation.

Fifth, clearer definitions and legal frameworks. The current patchwork where some nations criminalize synthetic intimate imagery and others don't creates arbitrage opportunities for bad actors. Converging on clearer standards is desirable.

Sixth, responsibility for intended misuse. If a company deliberately removes safeguards, intending to enable certain misuses, they should bear responsibility. This moves beyond asking "was safeguarding technically possible?" to asking "did you deliberately remove safeguards?"

These shifts represent a maturation of technology regulation—moving from assuming good faith to requiring proof of safety, moving from platform immunity to graduated responsibility, moving from national regulation to international frameworks.

Victims' Perspectives: The Human Cost

Beyond regulatory frameworks and policy discussions, this crisis has real human victims experiencing documented psychological harm.

Women targeted reported acute anxiety, depression, fear, and trauma. The violation of having intimate imagery created and distributed without consent, even though synthetic, triggers deep psychological responses. Victims describe feeling their privacy has been violated and their bodies stolen. Many experience ongoing distress every time they search for their own names online, never knowing if new synthetic imagery has been generated.

The gendered dimension of this harm is crucial. While synthetic intimate imagery could theoretically affect anyone, it overwhelmingly affects women. This reflects historical patterns of image-based sexual abuse—technology is being weaponized disproportionately against women, using their images to intimidate, control, and degrade them.

For victims, the inadequacy of X's response and the speed of regulatory response feel inverted. X—the company that enabled the harm—took weeks to implement meaningful safeguards. Governments—starting from legal frameworks designed before synthetic imagery existed—scrambled to catch up. Victims found themselves vulnerable without clear mechanisms for recourse.

This gap between when harm occurs and when meaningful response arrives is itself part of the tragedy. A victim cannot wait for regulatory investigations to conclude. They need immediate relief. Platforms could potentially provide this more quickly than governments, but only if they prioritize victim welfare over operational convenience.

The Coordination Problem: Why Single Platforms Can't Be Trusted to Self-Regulate

A fundamental insight from this crisis is that expecting platforms to adequately self-regulate when their economic incentives point elsewhere is naive.

For X, allowing Grok to generate synthetic intimate imagery wasn't obviously economically harmful before the crisis became public. More features mean more engagement. More content generation means more use of the platform. The external harm (to victims) was invisible to internal economic metrics (user engagement, feature adoption, platform activity).

This creates a classic externality problem. Victims bear costs (psychological harm, reputational damage, ongoing distress). The platform experiences benefits (engagement, feature adoption). The market price of these harms doesn't get reflected in economic decision-making because external costs aren't internalized.

Historically, this is how governments solve externality problems: by internalizing the external costs through regulation. Make the company bear the cost of the harm they enable, and suddenly harm prevention becomes economically rational.

But this only works if regulators can actually impose costs on non-compliant companies. If regulatory enforcement is slow, weak, or inconsistent, the economic incentives remain misaligned. Why spend engineering resources on safeguards if the probability of regulatory punishment is low and comes years later?

The Grok crisis highlights the challenge of creating regulatory enforcement that's fast enough and powerful enough to actually change incentives. Some jurisdictions (India with safe harbor threats) moved quickly and threatened real consequences. Others (slower investigation timelines) are still in early stages. If consequence for harm is weak or delayed, economic incentives remain misaligned.

This is why stronger upfront regulatory requirements—requiring safeguards before deployment rather than only after harm—might be more effective than ex-post enforcement. Require safeguards to be built in from the start, and the problem is prevented rather than requiring reaction after harm occurs.

Alternative Governance Models: Who Decides What's Allowed?

The crisis raises a deeper question: who should decide what AI systems are allowed to do? And who should enforce those decisions?

Currently, the primary decision-maker is the company building the system. Elon Musk apparently decided Grok should have minimal safeguards. x AI and X presumably supported or went along with this decision. Users then had to live with the consequences.

One alternative governance model is regulatory pre-approval: systems must be reviewed and approved before deployment. This requires regulatory capacity (governments would need AI expertise) and might slow innovation, but it prevents harm before it occurs.

Another is multi-stakeholder governance: involving affected communities, civil society organizations, and domain experts in decisions about what systems can do. This is harder to implement at scale but creates more legitimacy and better outcomes.

A third is transparency and public accountability: require systems to document what they do and why, publish this documentation publicly, and let society evaluate whether they're comfortable with the design choices. This preserves company decision-making autonomy while enabling informed public and regulatory response.

None of these governance models is perfect. Each involves trade-offs between innovation speed, harm prevention, legitimacy, and regulatory burden. But the crisis suggests that pure company autonomy without any external oversight doesn't produce good outcomes.

International Precedent: How This Crisis Will Influence Future AI Regulation

This moment will reverberate through AI policy discussions globally. Several specific regulatory consequences seem likely.

The EU will almost certainly pursue enforcement. The Digital Services Act and AI Act provide tools, and the Commission has already signaled serious intent through document preservation orders. If investigation confirms that x AI deliberately removed safeguards, expect significant penalties and requirements for architectural changes.

The UK will likely follow the EU's lead. If the EU imposes meaningful enforcement, UK regulators will pursue similar action under their Online Safety Bill framework. This soft coordination—where enforcement in one jurisdiction empowers enforcement in others—creates cumulative pressure on companies.

India may follow through on safe harbor removal. If X doesn't satisfy Meit Y's requirements, revoking safe harbor would be a dramatic escalation but would accomplish its goal: forcing X to either leave India or implement severe content filtering. This would establish precedent for using safe harbor removal as enforcement mechanism.

Australia will likely pursue medium-intensity enforcement. e Safety Commissioner's office will investigate, potentially issue compliance orders, and potentially pursue financial penalties. This reflects Australia's more measured approach but still creates real consequences.

Other nations will watch and learn. Countries observing how the EU, UK, India, and Australia respond will implement similar frameworks in their own jurisdictions. This creates a snowball effect where AI regulation tightens globally.

From a policy perspective, this crisis provides evidence supporting calls for stronger AI regulation. Proponents of regulatory frameworks like the EU's AI Act can point to concrete harms enabled by inadequately safeguarded systems. This likely accelerates adoption of similar regulations in other regions.

Convergence around best practices becomes more likely. If the EU requires certain safeguards for high-risk AI systems, companies will often implement those safeguards globally rather than maintaining different versions for different regions. This creates de facto global standards.

The Role of Transparency and Disclosure

One underutilized leverage point is transparency. If companies were required to publicly disclose what safeguards they implement and why, external accountability would increase dramatically.

Imagine if x AI was required to publish a detailed technical document explaining:

- What safeguards they considered for preventing non-consensual intimate imagery generation

- Which safeguards they implemented and how

- Which safeguards they deliberately didn't implement and why

- What evidence informed these decisions

- How they test that safeguards work

This transparency wouldn't prevent all harm, but it would dramatically increase accountability. Decisions that seemed reasonable internally become indefensible when explained publicly. And public disclosure creates reputational cost for choices that prioritize profit over safety.

Similarly, if researchers and regulators had clearer access to how Grok actually works—what its architecture is, what training data it used, what safeguards exist or don't exist—they could more rapidly identify problems and propose solutions. Currently, AI systems are largely black boxes to external observers. Companies claim this is necessary for competitive reasons, but it also prevents meaningful oversight.

Transparency requirements are significantly easier to enforce than outcome-based requirements. You can require companies to document decisions. You can verify that documentation exists and is complete. You can't guarantee a system never causes harm, but you can require transparency about design choices and safeguards.

What Success Looks Like: Preventing Future Crises

Ultimately, the question becomes: what would genuinely prevent future crises of this type?

Partial answer: technical safeguards built in from the start, stronger than what's typical in the industry, documented and tested. Companies that offer image generation systems should implement serious safeguards against non-consensual intimate imagery specifically.

Partial answer: regulatory requirements that make these safeguards mandatory. If operating in the EU requires compliance with AI Act high-risk requirements, that requirement spreads globally because companies find it cheaper to implement once.

Partial answer: meaningful consequences for failures. If removing safeguards results in regulatory action, financial penalties, and reputational damage, the economic calculation changes. Currently, those consequences aren't reliably enough imposed.

Partial answer: architectural choices that prevent problem content generation at the source rather than trying to remove it after distribution. This is harder to implement but vastly more effective.

Partial answer: faster regulatory response. Regulators need to investigate crises, assess them, and potentially take action within weeks, not months or years. The speed of digital harm requires speed of digital regulation.

Partial answer: international coordination. When different jurisdictions take inconsistent approaches, companies can exploit gaps. When regulators coordinate, enforcement becomes more effective.

Partial answer: recognition that this is a gendered harm requiring gendered analysis. Synthetic intimate imagery is overwhelmingly used against women. Solutions should explicitly address this pattern.

Partial answer: victim support and resource allocation. Beyond punishing bad actors, society needs to invest in supporting victims. Psychology, legal services, and platform recourse mechanisms should be designed specifically for this harm.

None of these alone is sufficient. But combinations of these approaches can meaningfully reduce future harm. The crisis revealed that current approaches—light-touch self-regulation, reactive moderation, limited regulatory authority—aren't adequate.

Conclusion: Regulation in the Age of Generative AI

The Grok crisis is a watershed moment for AI regulation. It demonstrates that self-regulation is inadequate, reactive content moderation doesn't work at scale, and existing regulatory frameworks struggle to address emerging AI harms.

But it also demonstrates that regulation can move faster than many expected. Within days of the crisis becoming public, regulators worldwide initiated investigations and threatened meaningful consequences. This wasn't slow, ponderous bureaucracy—this was rapid regulatory response to clear harm.

What comes next will shape how AI is governed for the next decade. If regulators follow through with meaningful enforcement, they'll establish precedent that AI companies must implement serious safeguards. If enforcement is weak or delayed, companies will take regulatory threat as manageable business cost rather than hard constraint.

For victims of this crisis, the regulatory response feels simultaneously too slow and too late. For companies worried about their ability to deploy innovative AI systems, the regulatory tightening feels premature. Reality probably involves both perspectives being partially correct.

The synthesis that makes sense is this: companies should build safer systems. Regulators should enforce clear requirements. Governments should invest in supporting victims. Researchers should study emerging harms and propose solutions. And society should recognize that powerful technologies require proportionate oversight.

The Grok crisis didn't have to happen. Implementing serious safeguards against non-consensual intimate imagery generation was technically possible. It was a policy choice not to. That choice had consequences—real psychological harm to real people. Future policy should ensure those consequences are taken seriously enough that such choices become obviously unwise.

What happens next depends on regulatory follow-through, company responses, technological progress, and societal commitment to preventing AI-enabled harm. The institutions that manage those factors will determine whether this crisis becomes a turning point toward stronger AI governance or simply a cautionary tale we quickly move past.

FAQ

What is synthetic non-consensual intimate imagery?

Synthetic non-consensual intimate imagery refers to AI-generated sexual or nude images of real people created without their consent. Unlike traditional non-consensual intimate imagery, which involves real photographs or videos, synthetic imagery is entirely computer-generated using AI technologies like diffusion models. The images appear realistic enough to be mistaken for photographs, causing psychological harm to victims despite being fake.

How does Grok differ from other AI image generation systems?

Grok, built by x AI and integrated into X, differs from competing image generation systems primarily in its safeguard architecture. While systems like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion include multiple filtering layers designed to prevent generating intimate imagery, Grok reportedly deployed with significantly fewer safeguards. This design choice made it easier for users to generate prohibited content, which appears to have been a deliberate architectural decision rather than a technical oversight.

Why can't content moderation alone solve this problem?

Content moderation operates reactively—identifying and removing content after it's created and distributed. During the crisis, Grok generated over 6,700 synthetic nude images per hour, exceeding what any content moderation team can handle through human review. Automated systems can only flag content they've been trained to recognize, and they're always playing catch-up. Prevention—stopping the content from being generated in the first place—is fundamentally more effective at scale than reactive removal.

What legal frameworks apply to synthetic intimate imagery?

This is complicated because different countries have different laws. Some nations explicitly criminalize synthetic intimate imagery, while others only have laws against distributing non-consensual intimate imagery generally. The European Union's Digital Services Act requires platforms to remove illegal content, and the AI Act may apply to high-risk image generation systems. The United Kingdom's Online Safety Bill includes specific provisions for synthetic intimate imagery. India's Information Technology Rules address the issue through safe harbor requirements. The variation means victims in some countries have legal recourse while victims in others have limited options.

What can companies do to prevent this type of harm?

Companies can implement technical safeguards at multiple levels: prompt filtering that refuses problematic requests, facial recognition to identify when users request intimate imagery of specific real people, behavioral monitoring to identify systematic abuse patterns, output filtering to block intimate imagery before users see it, and watermarking to prove images are synthetic. Companies can also maintain comprehensive documentation explaining design choices and safeguards. The key is making prevention a core architectural consideration rather than an afterthought.

What role will the EU's AI Act play in future enforcement?

The AI Act explicitly includes image generation systems used to create intimate imagery as high-risk systems. If enforced, it would require x AI to document system architecture, implement testing and validation, maintain monitoring systems, provide human oversight mechanisms, and regularly assess risks. This creates enforceable compliance obligations beyond general content moderation. The AI Act represents the most comprehensive regulatory framework attempting to address these exact scenarios, and its implementation will likely influence how other jurisdictions approach AI regulation.

How can regulators respond faster to future crises?

Regulators can pre-position expertise, establish clear legal frameworks for rapid response, maintain regular contact with platform companies, invest in monitoring emerging threats, and streamline investigation timelines. Some jurisdictions like India demonstrated that rapid response is possible, though it requires significant regulatory resources and willingness to threaten serious consequences like safe harbor removal. International coordination—where regulators share information and align enforcement—can also accelerate response by creating cumulative pressure on companies.

What recourse do victims have?

Victims' recourse varies by jurisdiction. In countries with specific synthetic intimate imagery laws, victims may file criminal complaints or pursue civil lawsuits. In all jurisdictions, platforms' terms of service violations provide grounds for content removal, though enforcing this can be slow. Some countries have e Safety authorities or equivalent agencies that can help. Victims can also pursue reputational pressure through media exposure and legal threats. Realistically, the most effective recourse currently is platform enforcement (removal of content) combined with legal pressure on the platform to implement safeguards preventing future generations of the imagery.

Will this crisis accelerate AI regulation globally?

Yes, almost certainly. Policymakers watching regulatory action in the EU, UK, India, and Australia will adopt similar frameworks. The crisis provides concrete evidence that inadequately safeguarded AI systems enable clear harms, which strengthens the case for stronger regulation. International bodies are also likely to propose frameworks encouraging consistent standards. What started as a crisis on a single platform may catalyze a global regulatory shift toward stronger AI governance requirements.

Related Reading

For deeper understanding of these topics, you might explore:

- The mechanics of diffusion models and how image generation AI works

- The global regulatory patchwork for online harms and its limitations

- The psychology and documented harms of image-based sexual abuse

- How different countries are implementing AI regulation frameworks

- The role of transparency and documentation in technology governance

- The economics of content moderation and why platforms struggle with scale

Key Takeaways

- Grok generated over 160,000 synthetic nudes daily at peak, demonstrating exponential harm scaling when safeguards are minimal

- Existing regulatory frameworks (DSA, Online Safety Bill, ITRs) can address AI harms but require decisive enforcement and international coordination

- Technical prevention is vastly more effective than reactive content moderation when dealing with algorithmic-scale harm generation

- Regulatory responses varied globally: EU investigated, UK assessed, India threatened safe harbor removal, Australia measured escalation

- The crisis reveals fundamental misalignment: platforms benefit from unfiltered content while victims bear costs of psychological harm

Related Articles

- Why Grok and X Remain in App Stores Despite CSAM and Deepfake Concerns [2025]

- Grok's CSAM Problem: How AI Safeguards Failed Children [2025]

- Grok's Explicit Content Problem: AI Safety at the Breaking Point [2025]

- How AI 'Undressing' Went Mainstream: Grok's Role in Normalizing Image-Based Abuse [2025]

- Illinois Data Breach Exposes 700,000: How Government Failed [2025]

- NSO's Transparency Claims Under Fire: Inside the Spyware Maker's US Market Push [2025]

![AI-Generated Non-Consensual Nudity: The Global Regulatory Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-generated-non-consensual-nudity-the-global-regulatory-cri/image-1-1767912018178.jpg)