AI's Impact on Enterprise Labor in 2026: What Investors Are Predicting

Introduction: The Reckoning Is Coming

We're standing at a peculiar moment in tech history. AI systems can now write code, design graphics, analyze spreadsheets, and handle customer service calls with surprising competence. Yet for all the breathless hype, the real economic impact on jobs remains frustratingly unclear. Nobody actually knows whether 2026 will be the year AI replaces millions of workers, augments them to extraordinary productivity, or does something messier that involves both.

But venture capitalists are placing bets. And they're increasingly betting that 2026 will be the year things get real.

In a recent survey, multiple enterprise-focused venture investors independently raised concerns about AI's impact on labor—without being prompted about the topic. That's significant. It suggests the conversation has moved beyond speculative think pieces into actual boardroom strategy. Companies are making budget decisions based on these expectations. HR departments are being asked difficult questions. Executives are eyeing their payroll numbers differently.

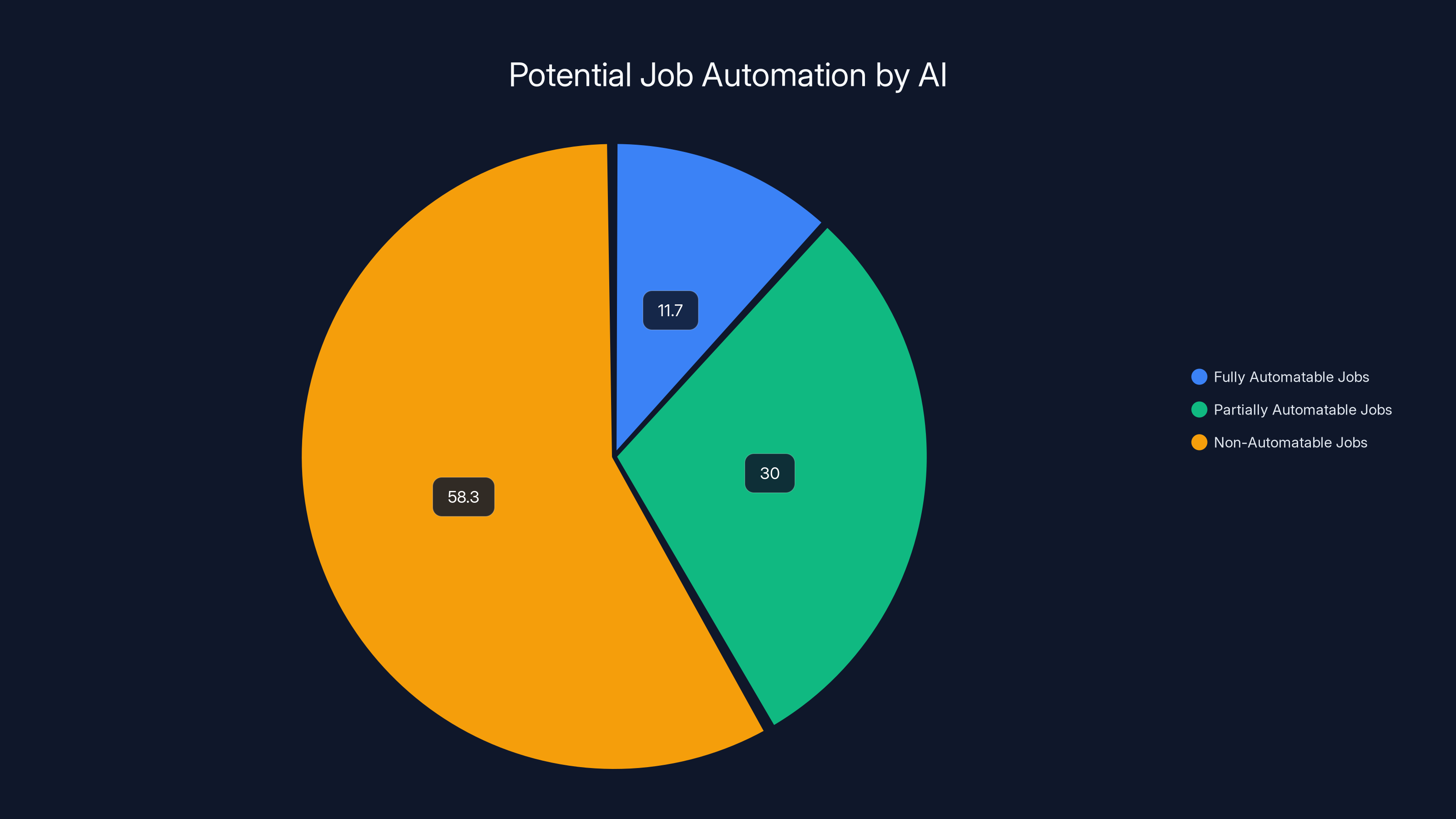

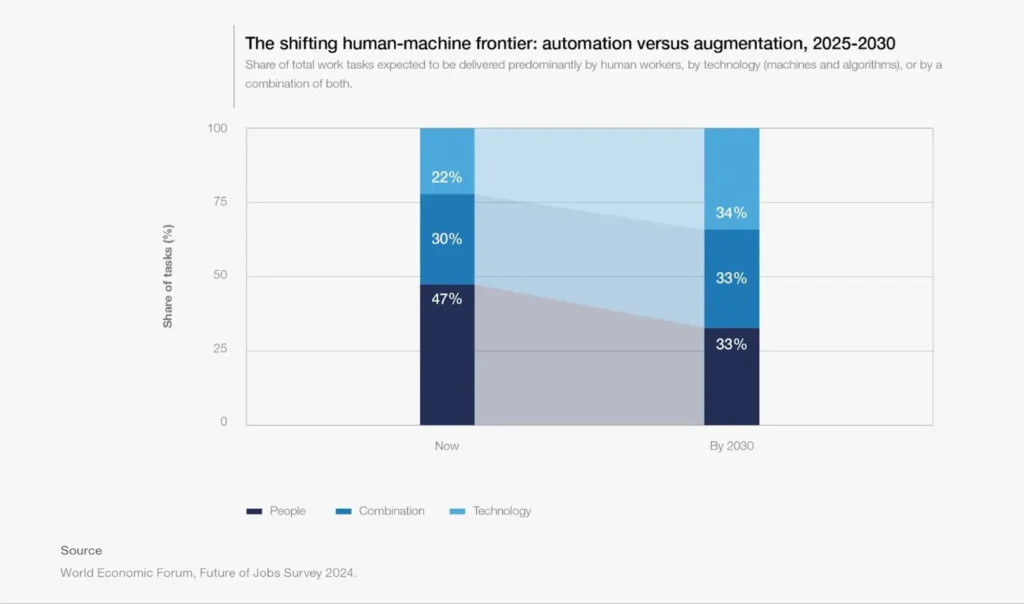

The scale of potential displacement is real. A November MIT study found that an estimated 11.7% of jobs could already be automated using current AI technology. That's not 2026—that's today. Surveys have shown employers are already eliminating entry-level positions because of automation. Entire companies are openly citing AI as justification for layoffs. Yet the MIT figure also means 88.3% of jobs still exist, and many of them will likely be transformed rather than eliminated.

So what happens in 2026? Nobody knows for sure. But the uncertainty itself is the story. Investors are hedging bets across a spectrum of outcomes, from catastrophic job displacement to a genuinely new equilibrium where humans focus on creative and strategic work while machines handle the repetitive grind.

This article explores what venture investors are actually predicting, what the research shows, and—most importantly—what it might mean for your career, your company, and the broader economy.

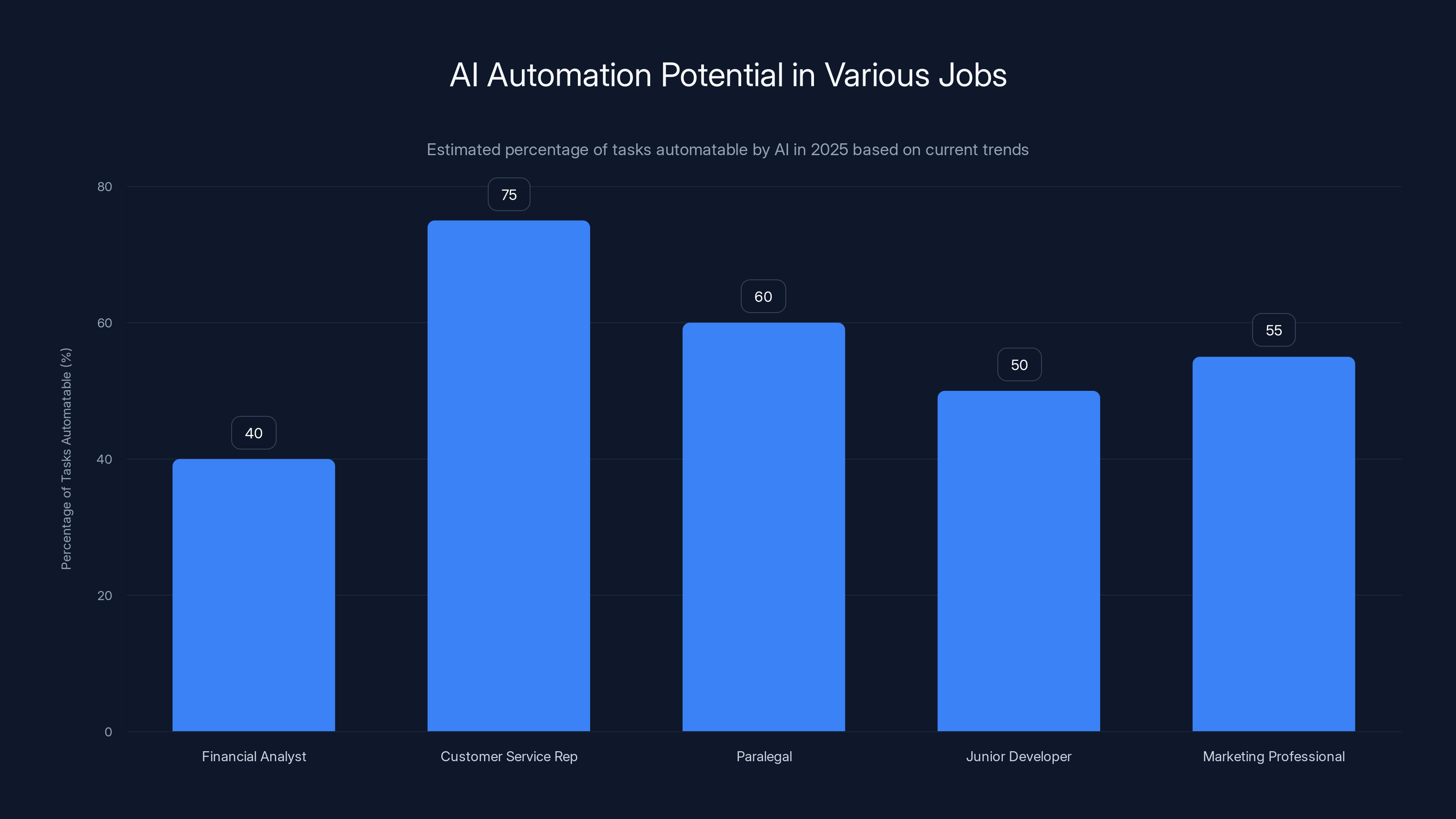

AI is capable of automating significant portions of tasks in various job roles, with customer service representatives seeing up to 75% of their tasks potentially automated. Estimated data based on current trends.

TL; DR

- MIT research shows 11.7% of jobs could be automated today using existing AI technology, suggesting the automation potential is already here

- Enterprise VCs predict major workforce changes in 2026, though opinions diverge sharply on whether this means layoffs, productivity gains, or both

- Companies are already eliminating entry-level roles and using AI as the justification for budget cuts, complicating the picture between genuine automation and opportunistic downsizing

- The shift from AI as a tool to AI as a replacement is the critical inflection point investors are watching—the difference between augmentation and displacement

- Budget reallocation from labor to AI is already happening, with some executives using AI adoption as cover for restructuring unrelated to actual automation needs

Estimated data suggests that AI adoption is significantly impacting workforce planning, with increased automation investments and hiring freezes being the most prominent trends.

The Current Automation Landscape: What Can AI Actually Do Right Now?

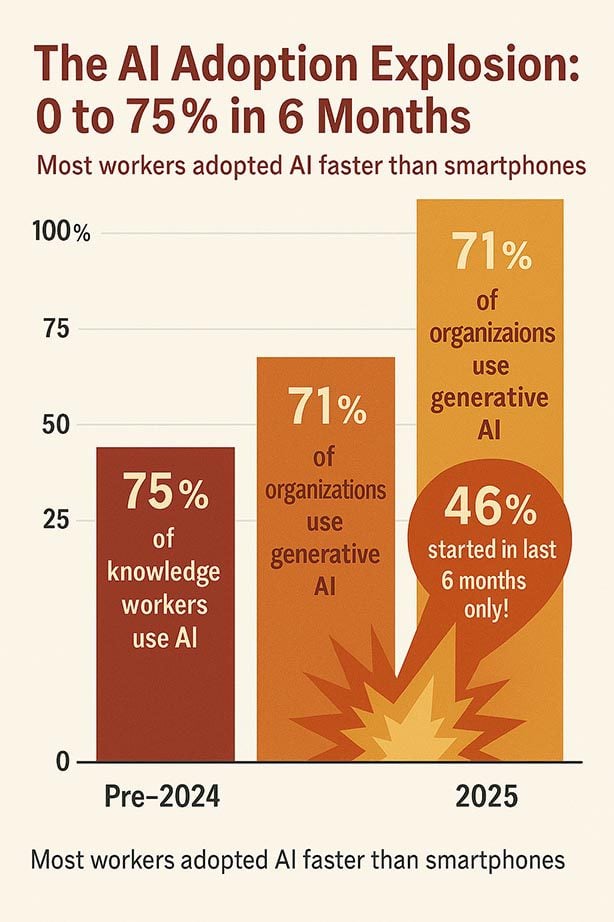

Before predicting 2026, we need to understand what AI can do in 2025. The data here is sobering—not because AI is all-powerful, but because it's already competent at specific tasks that represent meaningful portions of certain jobs.

The MIT study that found 11.7% automation potential wasn't speculative. Researchers analyzed actual job descriptions and mapped them to specific tasks. They asked: which of these tasks could current large language models and AI systems handle? The answer was surprising in its precision. It's not that entire job categories disappear—it's that segments within jobs become unnecessary.

Consider a financial analyst. Maybe 40% of their week involves gathering data, formatting reports, and running standard analyses. Those tasks are increasingly automatable. The other 60%—judgment calls, strategic recommendations, client relationships—still requires human thinking. So the job doesn't disappear. It changes. The analyst either becomes more efficient (and their company needs fewer analysts) or shifts focus to higher-value work (and the question becomes whether companies will actually promote people into those roles or just eliminate positions).

This pattern repeats across knowledge work. Customer service representatives can be partially replaced by AI chatbots that handle 70-80% of routine inquiries. Paralegals see their research and document review work compressed by AI tools. Junior developers spend less time on boilerplate code. Entry-level marketing professionals find their content calendar and email campaign work increasingly templated.

But here's the crucial detail: these are partial displacements, not total job eliminations—yet. The MIT figure of 11.7% represents complete job automation only. It doesn't count positions that become partially redundant or where headcount can be cut without eliminating the role entirely.

The distribution of automation risk is uneven. Entry-level positions are most vulnerable because they typically involve higher percentages of repetitive, rule-based work. Senior roles are more protected because they involve judgment and strategy. Administrative support, data entry, basic bookkeeping—these are exposed. Executive decision-making, creative direction, complex negotiation—these remain human.

Yet there's another layer: companies don't always deploy new capabilities efficiently. Many organizations buy AI tools and use them to accelerate existing processes rather than eliminate roles. A company might purchase an AI writing tool and have marketing teams produce twice as much content with the same headcount. That's productivity gain, not displacement. Until it isn't—and the company realizes they needed half the staff all along.

What's actually happening now: surveys show employers are already making changes. Some companies have explicitly frozen entry-level hiring, redirecting that budget toward AI platforms. Others have conducted layoffs with AI adoption cited as justification. Most are in the middle—experimenting with AI tools, seeing productivity gains, and quietly wondering if they need as many junior staff as they currently employ.

Why Investors Are Suddenly Talking About Labor in 2026

The timing of this conversation is worth examining. VCs aren't typically shy about discussing labor impacts—if they believed it was happening now, they'd say so. Instead, they're specifically calling out 2026. Why that year?

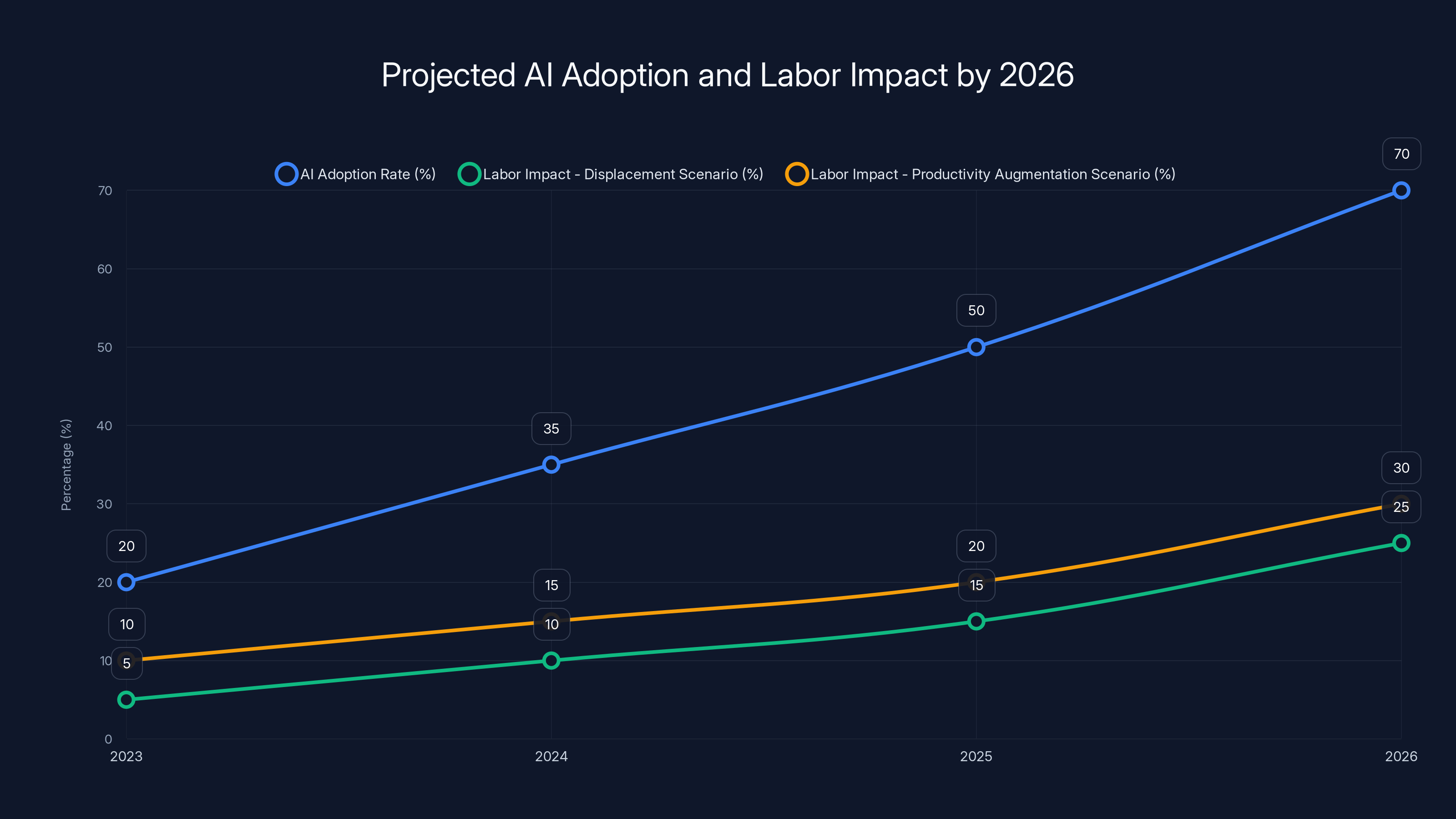

Part of it is timeline realism. AI adoption follows adoption curves. Early adopters (roughly 15-20% of enterprises) are already experimenting heavily. By 2026, you're moving into early majority adoption (the next 35% or so). That's when systemic changes become visible. The companies in the middle of the pack—the ones that are moderately sized, somewhat mature, and manage to avoid being first-movers—will be forced to make decisions. And decisions about AI almost always involve decisions about labor.

Another reason is budget cycles. Many enterprises operate on annual or biennial budget planning. A decision made in late 2025 or early 2026 about AI spending cascades into hiring freezes, workforce restructuring, and reorganization that plays out through the year. If companies decide collectively to spend 20% more on AI infrastructure and 20% less on entry-level hiring, that's visible by Q2 2026.

But there's also honest uncertainty. The investors surveyed didn't claim certainty. Eric Bahn from Hustle Fund explicitly said he doesn't know what the changes will look like—only that something significant will happen. That honesty is refreshing. It acknowledges that AI's labor impact could go multiple directions.

The spectrum they outlined includes:

Scenario 1: Aggressive Displacement - Companies use AI to eliminate redundant positions, particularly in junior roles, administrative functions, and routine knowledge work. Unemployment rises. Wage pressure increases for specialized positions that can't be automated. Social and political consequences emerge.

Scenario 2: Productivity Augmentation - AI tools make existing workers more capable. Companies maintain headcount but produce more output. Entry-level hiring continues (maybe increases) as companies need workers who understand AI tools. Wages stagnate because productivity gains accrue to companies, not workers.

Scenario 3: Role Transformation - AI handles routine work, humans shift to higher-value activities. This requires active upskilling and reorganization, which many companies fail to execute. Net result: some jobs change dramatically, others disappear, and workers in industries undergoing rapid transformation face real disruption.

Scenario 4: The Scapegoat Scenario - Companies use AI adoption as political cover for restructuring that was planned anyway, or driven by other factors. Executives blame AI for layoffs, but the real cause was declining business, management mistakes, or cost-cutting mandates from private equity owners. AI becomes a convenient narrative for changes that might have happened regardless.

What's interesting is that VCs like Antonia Dean from Black Operator Ventures think Scenario 4 is already happening. She suggested that companies will adopt AI, see the opportunity to cut labor costs, and credit AI for changes that might be more about opportunistic restructuring than genuine automation.

This creates a statistical problem: we won't actually know in 2026 whether displacement happened because AI replaced workers or because executives used AI adoption as justification for planned cost cuts. The data will show layoffs and hiring freezes. The causation will remain ambiguous.

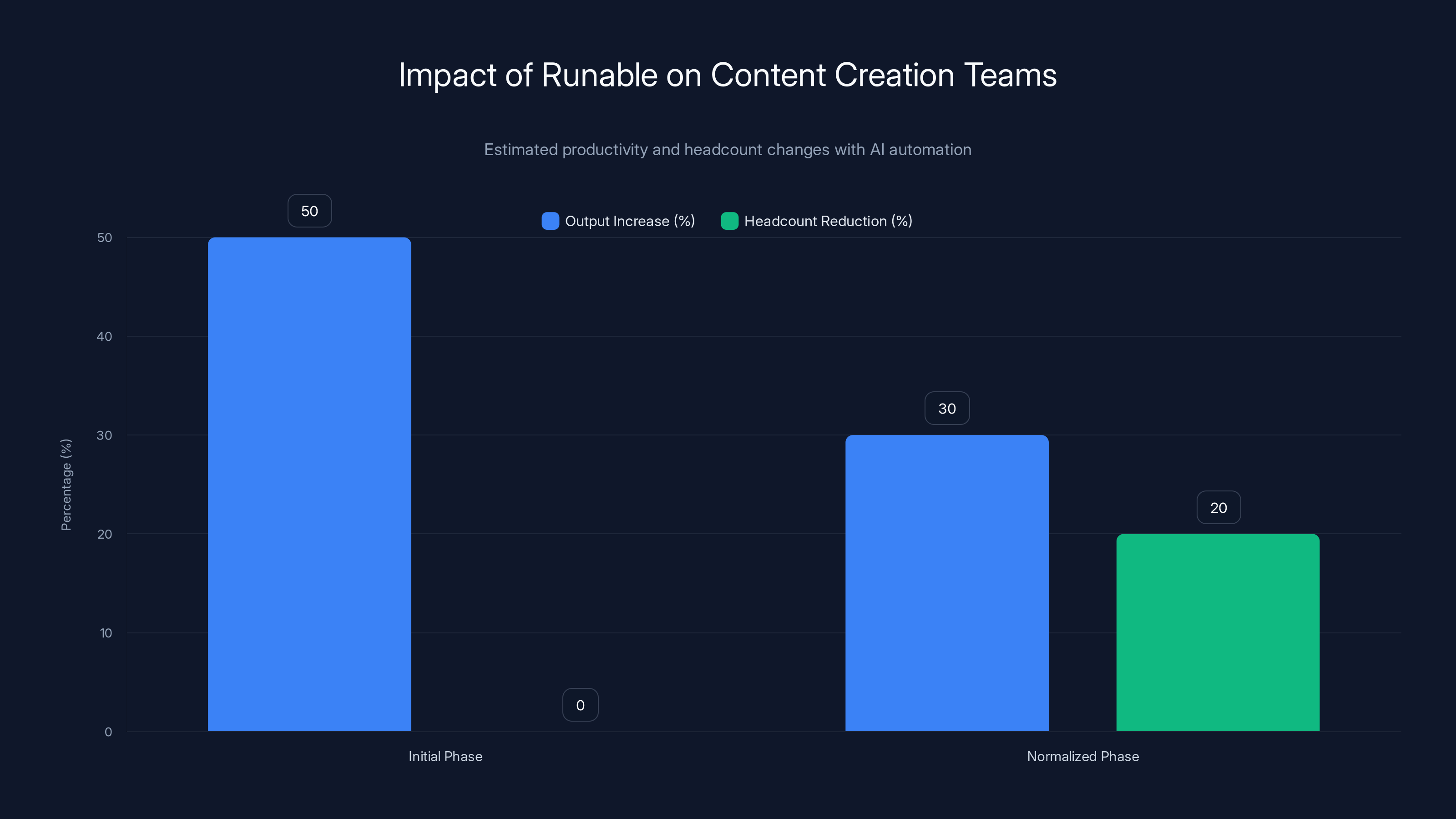

Initially, Runable increases output by 50% without reducing headcount. Over time, as output normalizes, headcount may decrease by 20%. (Estimated data)

The Evidence That Companies Are Already Adjusting Labor Plans

We don't need to wait for 2026 to see shifts. Evidence is already accumulating.

First, there's the hiring freeze phenomenon. Multiple tech companies and enterprises have paused or reduced entry-level hiring explicitly citing AI adoption and productivity gains. They're not laying off existing junior staff, but they're not replacing departing junior employees either. Over 12-24 months, this creates meaningful workforce reductions without visible layoffs. It's the HR equivalent of attrition-based population control.

Second, there's the direct evidence. Companies including Amazon, Google, and various enterprise software firms have announced headcount reductions with AI cited as a factor. Amazon specifically mentioned AWS AI tools making certain roles redundant. Google reduced a full business unit (You Tube shorts team reduction involved AI-driven features handling work). These aren't theoretical impacts—they're happening.

Third, surveys of employer plans show clear patterns. When asked about AI spending and workforce planning, employers report expecting to shift budgets from labor to technology. The Conference Board survey from 2024 found that 63% of CFOs expected to increase automation investment in the next two years. When automation increases, labor costs typically decrease—even if it's not immediate displacement.

Fourth, there's the structural economic signal. If AI genuinely increased productivity without reducing labor needs, you'd expect corporate spending on labor to hold steady or increase slightly. Instead, you're seeing companies announce AI investments alongside hiring freezes or headcount targets. That correlation is the smoking gun. Companies believe—whether correctly or not—that AI reduces labor requirements.

The wildcard is entry-level hiring specifically. If the only change is that companies hire fewer junior employees while keeping senior staff, the labor market adjusts but doesn't catastrophically break. Junior employees would face tighter competition, might need more experience to get hired, and could see wage pressure. But they wouldn't see unemployment spikes. The problem emerges if AI starts affecting mid-level roles significantly, or if the cumulative effect of entry-level hiring freezes across thousands of companies creates bottlenecks in career progression.

The AI-to-Agent Transition: When Tools Become Replacements

One investor used language that matters: 2026 will be "the year of agents." This is technical jargon, but it represents a critical transition.

For the past 18 months, AI systems have primarily been tools. You use Chat GPT to draft an email. You use Copilot to suggest code. You use Claude to analyze a document. You're still the agent—you're deciding what to do, reviewing the output, and taking responsibility. The AI is an instrument in your hands.

Agents are different. An agent is an AI system that operates independently, makes decisions, and takes actions on behalf of a human. You set parameters and goals, then the agent works toward those goals without requiring human decision-making at every step. It's the difference between a calculator (tool) and a chess engine (agent). The calculator helps you compute. The chess engine plays the game.

Agents represent a fundamental shift in labor dynamics. When AI is a tool, you need humans to wield it. When AI is an agent, you need humans to supervise it—and supervision requires fewer people than operation. A human can supervise multiple AI agents. But a human cannot hand off decisions to an AI agent and then claim they weren't responsible for the outcomes, so some human oversight persists.

This is where 2026 becomes critical. Several companies are moving toward agentic AI systems right now. If that transition accelerates through 2025 and into 2026—if systems become reliable enough and effective enough that companies trust them with less human oversight—the labor displacement could accelerate significantly. Not because the technology suddenly changes, but because the business case for using AI differently shifts.

Consider a scenario: an AI agent handles customer support interactions, escalates complex issues to humans, and learns from human feedback. You need one human supervisor for what previously required five full-time support staff. That's meaningful displacement without the AI being perfect—it just needs to be better than having no automation.

Or consider accounts receivable: an AI agent processes invoices, tracks payments, follows up on overdue accounts, and flags unusual patterns. A human accountant reviews flagged items. This reduces headcount without eliminating the role. Again, the AI doesn't need to be perfect—it just needs to handle the 85% of routine work, leaving humans for the 15% requiring judgment.

Multiple investors mentioned this agent transition as the key inflection point. Current AI tools are impressive but still require heavy human input. Agents, if they reach sufficient reliability, could reduce human input substantially.

The timeline matters. If agents become genuinely reliable and trustworthy in 2026, then 2026 becomes the turning point. If they remain experimental and temperamental through 2026, then the disruption pushes into 2027-2028. That one-year difference affects millions of people's career plans.

Approximately 11.7% of jobs could be fully automated with current AI, while partial automation could affect a larger portion. Estimated data for partially and non-automatable jobs.

Corporate Budget Dynamics: How Money Moves From Labor to AI

When a CTO proposes an AI investment, where does the budget come from? That's not rhetorical—it's fundamental to understanding labor impacts.

There are three possible sources: new money (the company's revenue increased), money redirected from other technology spending, or money taken from labor budgets. Most companies aren't experiencing new money in the form of incremental revenue. And most already have mature technology stacks where optimization is possible but not transformative.

So the path of least resistance is taking money from labor budgets. Not from executive salaries or middle management, but from entry-level hiring, contractor budgets, and "headcount growth plans." A company might have budgeted for hiring 50 junior developers next year. Instead, they hire 20 junior developers and spend the freed-up capital on AI infrastructure and platforms.

This creates a cascade of effects. Fewer entry-level hires means fewer people entering the career pipeline. Over time, this creates gaps in mid-level talent as people who would have been promoted into those slots simply aren't present. It creates career bottlenecks for people trying to move up. And it affects universities and coding bootcamps as fewer companies are willing to hire inexperienced people.

The second-order effect is wage pressure. If there are fewer entry-level jobs, people have to compete harder for them. Some will demand higher wages. Others will undersell themselves out of desperation. Many will leave the field entirely, reducing labor supply and potentially pushing some wages up—but in a chaotic, uneven way that disadvantages those without strong networks or credentials.

Venture investors mentioned another dynamic: companies will shift budgets from labor to AI even if the AI investment doesn't directly replace those workers. The justification is "we need to be competitive," or "we need to invest in AI to stay relevant." The labor reduction happens separately, for different reasons, but both are attributed to "AI transformation." This makes it impossible to know the true causal effect.

One investor specifically mentioned this: companies will "increase their investments in AI to explain why they are cutting back spending in other areas or trimming workforces." In other words, AI becomes the narrative cover for cost-cutting that might be driven by other factors—investor pressure, declining profit margins, management changes, or general belt-tightening.

If this is accurate, then the labor market impact in 2026 might be substantial without AI being the primary driver. AI would be the scapegoat, not the cause. This distinction matters enormously for policy makers trying to address labor impacts, because it suggests AI is partly a symptom of broader economic pressures rather than purely a technological driver of change.

The Counterargument: AI as Amplifier, Not Replacement

Not everyone in the VC world sees 2026 as a displacement year. Some argue that AI, despite its capabilities, will primarily amplify human productivity rather than replace human workers.

The theory goes like this: yes, AI can automate routine tasks. But jobs aren't 100% routine tasks. And when AI handles the routine part, humans can focus on higher-value work. A paralegal doesn't disappear—they stop doing document review and start doing case strategy. A developer doesn't disappear—they stop writing boilerplate and start architecting systems. A marketing analyst doesn't disappear—they stop running standard reports and start developing strategic insights.

This is theoretically sound. It describes what should happen. The evidence is mixed on whether it actually does.

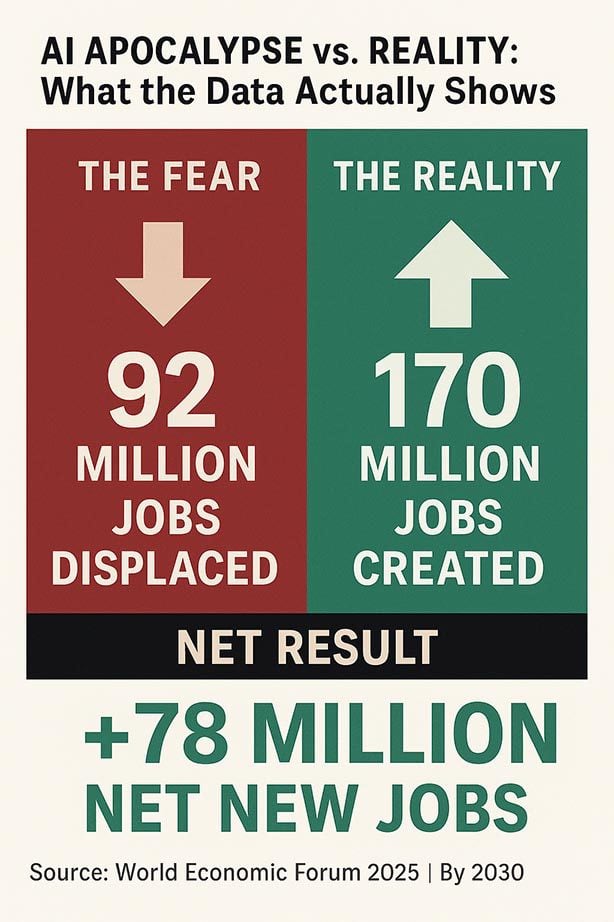

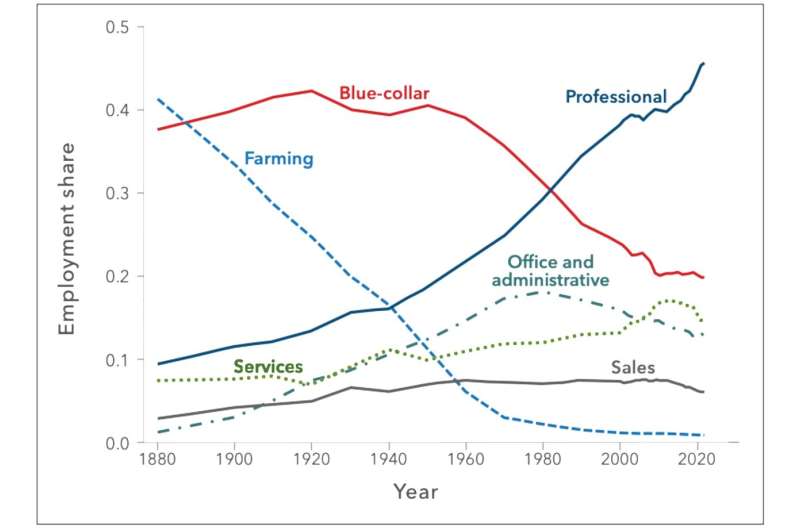

Historically, technology has destroyed jobs in specific categories while creating new jobs in different categories. The net effect on employment has usually been positive—technology creates more jobs than it destroys, just in different sectors requiring different skills. The problem is transition: workers displaced by automation often can't simply move into the new jobs being created. A textile mill worker doesn't automatically become a software engineer. The adjustment period is painful, and for some workers, the new jobs pay less than the old ones.

With AI, the concern is speed. Previous technological transitions happened over 10-20 years. AI is moving faster. If the transition period compresses, the pain concentrates. You get visible unemployment and disruption before the economy has a chance to adapt and create new roles.

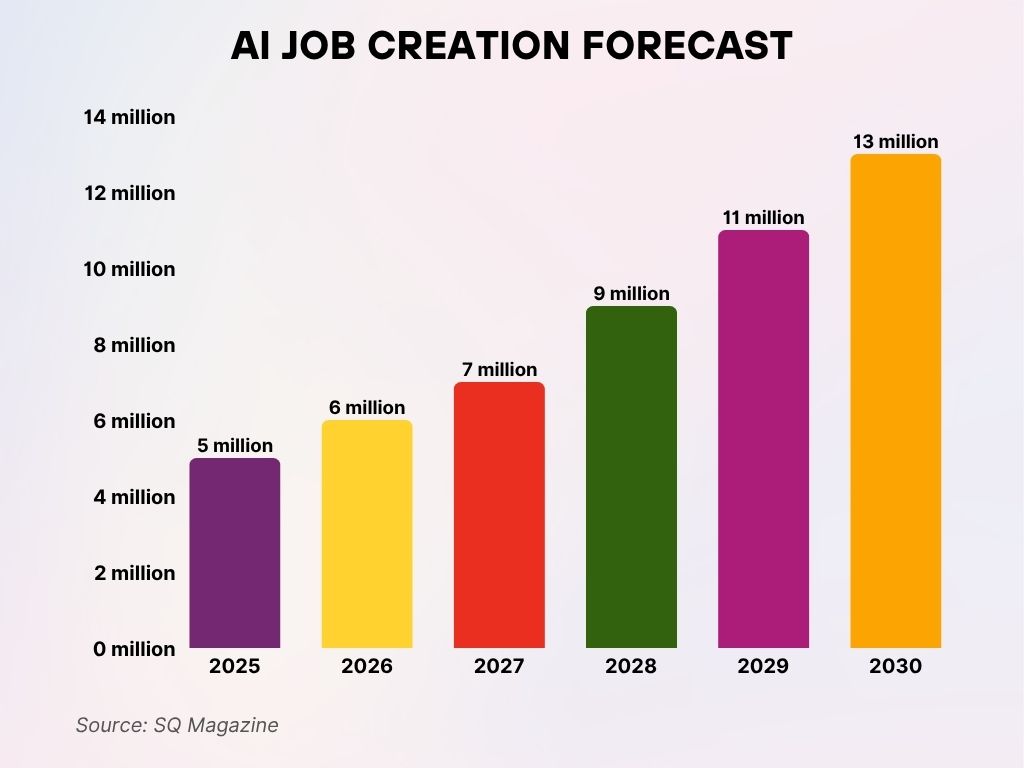

Also, the jobs AI might create are different from the jobs it destroys. If AI eliminates 50,000 entry-level customer service roles, what new jobs get created? Probably supervision and management roles for AI systems—but maybe only 5,000-10,000 of them, and they might require advanced degrees. The other 40,000-45,000 displaced workers don't simply get promoted into management. They have to find completely different careers.

So the counterargument—that AI augments rather than replaces—is plausible but requires active labor market management and rapid upskilling. It doesn't happen automatically. Companies have to choose to retrain workers rather than replace them. Workers have to have access to education. The economy has to be dynamic enough to create new categories of roles.

None of that is guaranteed. So even if AI's theoretical impact is augmentation, the practical impact could be displacement if companies and institutions fail to manage the transition.

By 2026, AI adoption is expected to reach 70%, with significant labor impacts. Displacement could affect up to 25% of roles, while productivity augmentation might enhance 30% of positions. Estimated data.

Entry-Level Hiring: The Canary in the Coal Mine

If you want to predict what happens in 2026, watch entry-level hiring in 2025. This is the most sensitive indicator of AI's labor impact.

Companies hire junior employees for several reasons: to fill growing demand, to find emerging talent, to offload routine work that senior people shouldn't do, and to have a pipeline for future leadership. When entry-level hiring drops significantly, it signals that companies don't believe they need junior staff anymore—or at least not as many as before.

Why junior staff specifically? Because junior employees do a lot of routine work. They handle junior-level customer support, junior-level coding, junior-level analysis, junior-level marketing. These tasks are the most automatable. Senior staff move to these roles as punishment or as a natural career track before becoming senior. When you remove the junior layer, you either eliminate that work (it's now automated) or compress it—senior people do less of it, spending more time on senior work.

The data on entry-level hiring is preliminary but concerning. Multiple sources report tech companies being more cautious about new graduate hiring. Some companies have explicitly stated they're using AI tools as alternatives to hiring junior staff. It's not yet a dramatic collapse—entry-level hiring hasn't crashed—but the trend is visible.

Here's the danger: entry-level hiring is how most people start careers. If it shrinks substantially, you create a lost generation of early-career professionals who can't break in. They don't have experience because they can't get jobs without experience. Companies don't hire them because there's no entry point. The result is talent scarcity a decade down the line as there are fewer mid-level professionals because there were fewer entry-level professionals five years prior.

This is a market failure that requires intervention. If AI genuinely reduces demand for junior staff, the market needs alternate pathways for early-career professionals. Apprenticeships, industry-specific bootcamps with employer partnerships, or subsidized entry-level roles could work. But these require intentional choices. They don't happen automatically.

So entry-level hiring in 2025-2026 is the key metric. If it holds steady or grows, the augmentation narrative is probably correct. If it drops sharply, displacement is likely. And if it drops modestly but leads to compressed career paths (fewer people reach senior levels), then you're seeing transformation without the worst-case scenario.

The Role Transformation Scenario: Winners and Losers

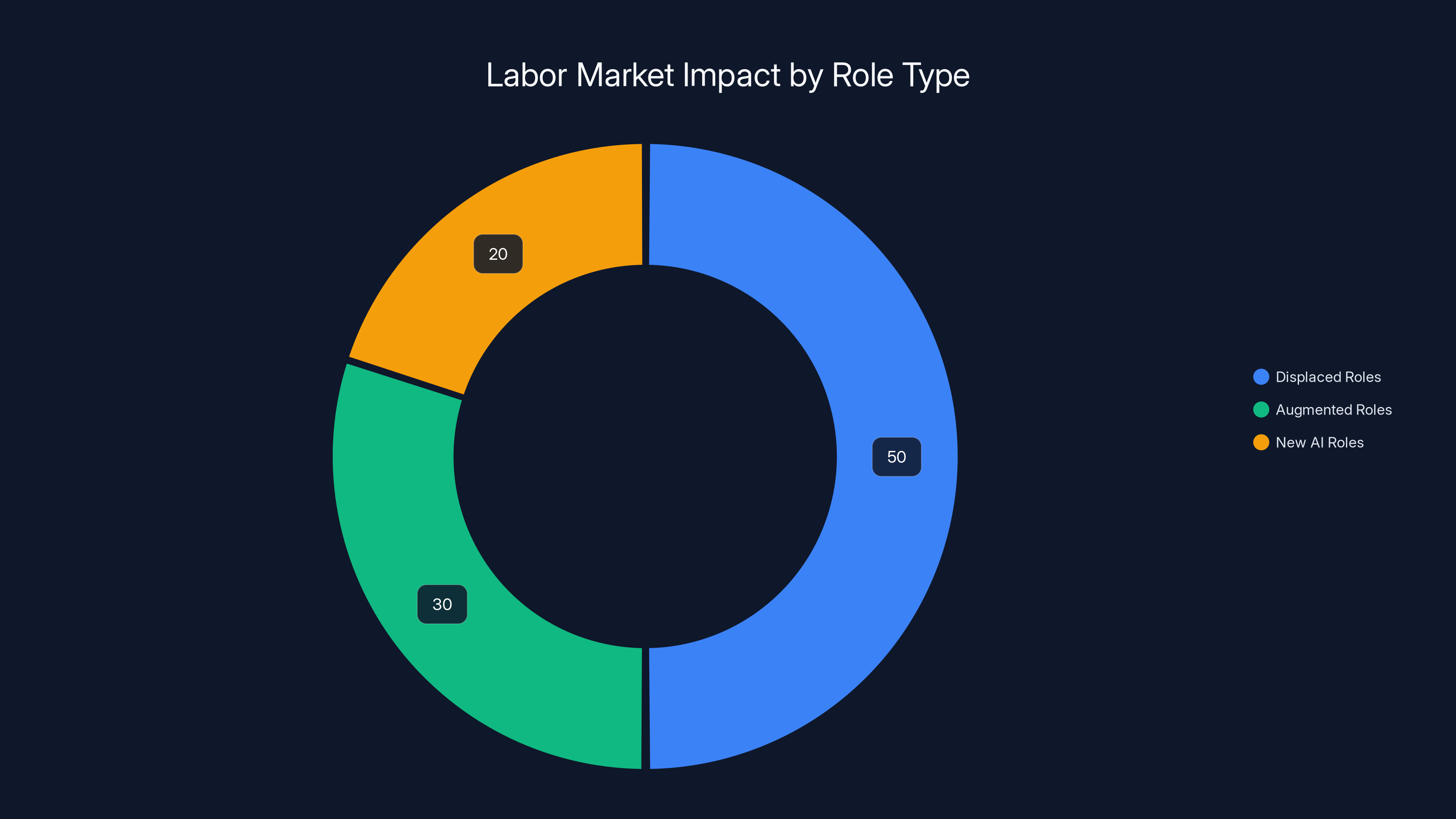

Perhaps the most realistic outcome is somewhere between pure displacement and pure augmentation. Some roles transform dramatically. Others disappear. New ones emerge. The labor market reshuffles.

In this scenario, the big losers are routine knowledge workers without significant experience or credentials. A college graduate with a degree in business administration who would have gotten an entry-level business analyst role finds that role doesn't exist anymore—it's been automated or consolidated. They have to either acquire technical AI skills (retraining) or find a completely different field.

The medium-term winners are people with expertise in fields where AI is a tool, not a replacement. Experienced accountants, lawyers, doctors, engineers, and managers use AI to become more efficient. They might work less, produce more, or spend time on higher-value work. Their compensation holds steady or increases, even if their company headcount shrinks.

The potential new winners are people who understand AI systems and can manage them. AI operations roles, prompt engineering (maybe), AI training and fine-tuning, and roles that don't exist yet but involve human oversight of AI systems. The question is whether there are enough of these roles to absorb displaced workers. The answer is probably not—maybe 10-20% as many new roles as displaced ones.

The transformation also affects different industries unevenly. Software development, customer support, accounting, paralegal work, data analysis, and content creation are most exposed. Healthcare, skilled trades, personal services, and creative fields are less exposed (though not immune). So labor market impacts are localized. Some regions and industries face substantial disruption. Others experience minimal change.

For individual workers, the strategy is clear: if your job is 50%+ routine, automatable tasks, you should be concerned. You should either develop expertise that makes you less replaceable (moving up the value chain) or develop skills in areas less exposed to automation. The people who will do well in a transformed labor market are those who can do work that AI either can't do (requires human judgment, creativity, interpersonal connection) or requires human oversight of AI systems (knowing both how to use the technology and when to override it).

Estimated data suggests that 50% of roles may be displaced, 30% augmented, and 20% new AI roles created. This highlights the uneven impact of AI on the labor market.

What Happens if the Prediction Is Wrong?

There's a meaningful chance that 2026 is not the year of significant labor disruption. Several factors could push the timeline back.

First, AI might hit a capability wall. The systems we're building have plateaued on some benchmarks. Newer architectures might be needed for meaningful improvements. If that research takes longer than expected, the timeline for economically viable agents extends into 2027 or beyond.

Second, companies might be more conservative with AI adoption than expected. The technology hype cycle suggests this is possible—lots of experimentation with little widespread adoption. Companies might buy AI tools, experiment briefly, find limited value, and slow their investment. Labor impacts would be muted.

Third, regulation could slow deployment. If governments pass AI labor regulations—requirements for retraining displaced workers, restrictions on mass automation, AI impact assessments—companies might hesitate. This wouldn't prevent AI adoption but could slow it enough to push major labor impacts into 2027.

Fourth, the economy could weaken, making 2026 a year of general belt-tightening rather than AI-specific changes. If there's a recession, companies cut labor for economic reasons, not AI reasons. The labor impact is real, but the cause is different, and the recovery pathway might be different.

If 2026 doesn't bring significant labor disruption, the narrative shifts. "AI will transform labor" becomes "AI is overhyped." Investment cools. Companies shift resources. The timeline extends. It's still happening, just later than predicted. Which might actually be better—it gives more time for adaptation.

Preparing for Disruption: What Workers and Companies Should Do

Whether the disruption comes in 2026 or later, preparation is sensible.

For workers: If your job is routine-heavy, spend 2025 upskilling in areas that AI can't easily automate. This probably means developing domain expertise, people skills, or creative skills. A customer service representative becomes a customer success strategist. A data analyst becomes an analytics leader with judgment and strategic insight. A junior programmer becomes a systems architect. The goal is to be valuable not because you can do routine work, but because you understand when and how to apply tools (including AI) to solve meaningful problems.

Also, build optionality. Don't be so specialized in one narrow skill that displacement forces you into an entirely different field. But don't be so generic that you're easily replaced. The sweet spot is being solid at a core skill and knowledgeable about adjacent areas.

For companies: If you haven't invested in understanding your labor in terms of task composition, do it now. Map roles to tasks. Understand which tasks are automatable and which require human judgment. Then make conscious decisions about what you want automation to do. Do you want to eliminate roles? Transform them? Increase productivity? Different answers lead to different labor strategies.

Also, think about retention and upskilling. If you're automating routine work, you need people who can do the non-routine work. Those people need to be trained, developed, and retained. That costs money. If you plan to cut labor costs by eliminating junior roles, you're accepting that you'll have difficulty promoting people into senior roles in 5-10 years. That's a structural economic risk.

For investors: If you're betting on AI labor impacts, be specific about timing and mechanisms. "2026 will be disruptive" is less useful than "companies adopting agent-based systems will reduce support staff by 30-50% by Q4 2026." Specific predictions are falsifiable. General ones let you claim victory whatever happens.

Also, recognize that labor displacement creates policy and political risks that don't show up in cap tables. If AI causes substantial unemployment, regulation is likely. That affects every AI company's business model. Thinking through that tail risk early is smarter than being surprised by it later.

The Policy and Political Dimension: Why 2026 Matters Beyond Economics

If significant AI-driven labor displacement happens in 2026, it will be political dynamite. And politicians will care more about the appearance of the problem than the nuance of its causes.

A doubling of entry-level hiring or a sharp increase in layoffs attributed to AI will create pressure for regulation, even if the true cause is complex. Some of that regulation might be useful—requirements for corporate transparency about AI impacts, support for worker retraining, taxation of automation. Some might be destructive—bans on AI tools, regulations so strict they prevent beneficial uses, protectionist policies.

The risk is that by 2026, if displacement is visible and significant, the political window for thoughtful policy closes. You get reactive regulation that addresses the headline problem without understanding the underlying economics. You get populist policies that feel good but don't actually help displaced workers. You get capital flight as companies move to jurisdictions with fewer AI regulations.

So 2026 matters not just economically but politically. It's the year when AI labor impacts move from theoretical to apparent. That reality will shape policy for the next decade.

For workers in 2026, the political response will matter as much as the economic reality. If governments respond with effective retraining programs and labor market support, the transition is painful but manageable. If they respond with AI bans or restrictions that slow economic growth without helping workers, the outcome is worse for everyone.

Looking Beyond 2026: What Comes After

Even if 2026 is the inflection point, it's not the endpoint. The transformation continues beyond that year.

If major labor displacement begins in 2026, you'd expect it to accelerate in 2027-2029 as AI capabilities improve, system reliability increases, and companies gain confidence in automation. The labor market would continue reshuffling. You'd see sectoral changes intensify. Some industries would stabilize with fewer workers but higher productivity. Others would continue turbulent adaptation.

You'd also see policy responses begin in 2027-2028. Governments, if they're smart, would introduce retraining programs and labor market support that takes a couple years to build. That might ease transitions for workers displaced in 2026-2028.

By 2030, the new equilibrium might be clearer. You'd have real data about whether AI created more jobs than it destroyed, whether displaced workers found new roles, whether the transition was painful or catastrophic, whether policy interventions helped or hurt.

The people currently making career decisions—college students choosing majors, early-career professionals deciding whether to stay in their fields—are basically gambling on this timeline. They're choosing skills and fields with incomplete information about whether those skills will be valuable in 2030.

That's not new—careers have always involved uncertainty. But the pace and magnitude of potential change are higher with AI. The cost of choosing wrong might be higher. The adjustment period might be shorter. That concentration of risk in a narrow time window is the unique challenge of AI labor impacts.

The Honest Uncertainty: Acknowledging What We Don't Know

Here's what we actually know:

AI systems can automate some routine, well-defined tasks. We know this empirically. We know it's happening right now. Companies are already using AI to reduce labor in specific areas.

We don't know at what pace this will accelerate. We don't know if it will hit capability limits or continue improving steadily. We don't know if companies will use automation to eliminate roles or transform them. We don't know if the economy will create new roles fast enough to absorb displaced workers. We don't know if 2026 is the inflection point or if disruption comes in 2028 or 2032.

We don't know if AI labor displacement will be worse than previous technological transitions or if it will follow similar patterns. We don't know if policy responses will be helpful or harmful. We don't know if workers will successfully retrain or if displacement becomes permanent for some cohorts.

What we know is that uncertainty itself is consequential. People are making decisions—career choices, investment choices, policy choices—based on predictions about AI labor impacts. If those predictions are wrong, the consequences compound. A worker who sacrifices early-career income to get AI training hoping for premium salaries later faces a different world if those premiums don't materialize. A company that invests heavily in automation faces disruption if the technology doesn't deliver expected productivity gains. A government that restricts AI development faces economic slowdown if the restrictions prevent beneficial innovations.

So the honest take from venture investors shouldn't be taken as gospel. It's an educated guess. It's worth considering. But it's not certain. And reasonable people can disagree about 2026's likely outcomes.

Runable and the AI Productivity Frontier

As enterprises navigate these labor transitions, platforms like Runable represent a specific use case: augmentation rather than displacement. Runable provides AI-powered automation for creating presentations, documents, reports, images, and videos—work that traditionally requires human effort but is increasingly standardized and templatable.

The question Runable users face is exactly the labor question investors are debating. Does using Runable (at $9/month) to automate content creation mean you need fewer content creators? Or does it mean your existing creators produce more and higher-quality content? The answer depends on how companies choose to use the tools. If a marketing team of 10 can now produce the output that previously required 15, does the company cut to 10 people? Or does it keep 10 people and aim for 50% more output?

Most evidence suggests companies initially increase output rather than immediately cutting headcount. But over time, as the expanded output becomes normalized, headcount expectations adjust downward. The tool temporarily augments productivity, but eventually it transforms labor requirements.

Use Case: Automate your weekly reporting and free up hours for strategic analysis instead of manual document creation.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways and Strategic Implications

So where does all this leave us?

First: Venture investors are genuinely predicting significant labor market changes in 2026. This isn't speculation or thought leadership—it's their actual belief shaping their investment decisions and portfolio company guidance.

Second: The specific outcome is uncertain. Will it be displacement, augmentation, transformation, or a mix? Nobody truly knows. But the uncertainty shouldn't paralyze decision-making. You can prepare for multiple scenarios simultaneously.

Third: Entry-level hiring is the key indicator to watch. If it holds steady through 2025, the augmentation narrative is probably correct. If it drops sharply, displacement is likely.

Fourth: Policy response in 2026-2027 will be as important as technological change in determining outcomes. Good policy can ease transitions. Bad policy can amplify disruption.

Fifth: Individual workers should focus on developing skills that make them less automatable: judgment, creativity, relationship-building, strategic thinking. Routine, rule-based skills are most at risk.

Sixth: Companies should be intentional about whether they want automation to eliminate roles or transform them. Different strategies require different labor policies and different implications for remaining staff.

Finally: This is the decade for adaptation. Whether the inflection point is 2026 or 2028 or 2030, the fundamental dynamics are moving in one direction. The labor market is shifting. Workers, companies, and governments need to prepare for that shift intentionally, transparently, and with genuine attention to how to help people navigate disruption.

FAQ

What percentage of jobs could be automated by AI right now?

According to MIT research, approximately 11.7% of current jobs could be fully automated using existing AI technology. However, this doesn't account for partial automation or role transformation where portions of jobs become unnecessary. The actual labor impact is likely higher when you include jobs that could be substantially changed through automation, even if not completely eliminated.

Why are venture investors specifically predicting 2026 as the turning point?

Venture investors point to 2026 as the year when AI adoption moves from early adopters to the broader market, when budget cycles force decisions about AI investment versus labor spending, and when agentic AI systems might reach sufficient reliability to reduce human oversight requirements. It's the convergence of technology readiness, market adoption, and financial decision-making cycles.

Are companies already eliminating jobs because of AI?

Yes, companies are already eliminating some positions and freezing entry-level hiring in response to AI adoption. However, it's difficult to isolate whether this is purely due to AI capability or whether companies are using AI as justification for cost-cutting driven by other factors. The trend is visible but still too early to measure precisely.

How is AI's labor impact different from previous technological transitions?

The pace is significantly faster, which concentrates disruption into a shorter timeframe. Previous technological revolutions played out over 15-20 years, allowing gradual labor market adjustment. AI is accelerating change on a 2-5 year timeline, which could create unemployment spikes before the economy adapts and creates replacement roles.

What should workers do to prepare for AI-driven labor changes?

Workers should focus on developing skills that AI cannot easily replace, including strategic judgment, creative thinking, complex problem-solving, relationship management, and domain expertise. They should also build optionality by understanding adjacent fields and developing skills that transfer across multiple roles, making them valuable if their current role transforms.

Could the 2026 prediction be wrong?

Absolutely. AI development could hit technical limits, companies could be more conservative with automation than expected, regulatory constraints could slow deployment, or economic conditions could change the timeline. Predictions about emerging technology are inherently uncertain. The 2026 timeline should be considered a scenario, not a certainty.

How should companies decide whether to use AI to eliminate roles or augment workers?

This requires explicitly mapping tasks within roles to understand what can be automated, then making intentional choices about desired outcomes. Companies that want to eliminate positions should plan retraining and exit support for affected workers. Companies that want to augment should focus on how to redeploy freed-up worker capacity to higher-value activities, which requires active management and culture change.

What does "agentic AI" mean and why is it important for labor?

Agentic AI refers to systems that operate independently toward specified goals, making decisions without human input at each step. This is different from current tools that require human direction. Agentic systems are important for labor because they reduce the ratio of humans to automated work—one human might supervise multiple AI agents, whereas tools typically require human operation. If agents become reliable in 2026, labor displacement could accelerate.

Is there evidence that AI augments productivity rather than replacing workers?

Theoretically, AI should augment productivity by automating routine work so humans can focus on higher-value tasks. Some evidence supports this in early deployments. However, the economic incentive for companies is to reduce labor costs, not increase productivity per se. So even if AI augments capability, companies might respond by reducing headcount rather than increasing output.

What role could policy play in managing labor disruption?

Policy responses could significantly moderate or amplify labor disruption. Effective policies might include worker retraining programs, transition assistance, tax incentives for companies that retain workers, and transparency requirements about AI adoption. Poor policies might include blanket AI restrictions that prevent beneficial uses, or regulations that force specific labor practices without evidence they work. The policy response in 2026-2027 could be as important as the technology itself.

Conclusion: 2026 as Inflection Point

We're at one of those rare moments in economic history where predictions from informed observers carry weight because they're shaping actual decisions. Venture capitalists believing that 2026 will bring significant AI labor impacts means those investors are guiding portfolio companies toward (or away from) certain strategies. It means companies are making hiring decisions based on expectations about future labor needs. It means workers are choosing skills and careers with these expectations in mind.

Whether the prediction proves accurate or not, the fact that it's being made and believed is itself consequential. Markets are forward-looking. They price in expected changes. So the mere expectation of 2026 labor disruption creates economic consequences even before the disruption materializes.

That said, we should hold these predictions loosely. Technology adoption is uncertain. Economic outcomes are harder to predict than technical capabilities. And human responses to disruption are infinitely variable. The specific 2026 timeline could easily be off by a year or three. The magnitude of change could be smaller or larger than expected. The distribution of impacts—who wins, who loses, which industries transform fastest—will likely surprise everyone.

But the direction is clear. AI is capable of automating routine work. Companies have economic incentives to deploy it. Labor markets will eventually adjust, but the transition period will involve real disruption for real people. How well we navigate that transition depends on preparation, intention, and policy response over the next 18-24 months.

So investors might be right about 2026. Or they might be early. But they're almost certainly right about the direction. The question for workers, companies, and policymakers is not whether AI will impact labor, but how—and what we do about it.

Your career decisions in 2025 and your company's labor strategy should account for that reality. Not with panic, but with clear-eyed recognition that the ground is shifting. The ones who prepare thoughtfully will adapt successfully. The ones who wait for certainty will be caught in the transition.

![AI's Impact on Enterprise Labor in 2026: What Investors Are Predicting [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-s-impact-on-enterprise-labor-in-2026-what-investors-are-p/image-1-1767200898320.jpg)