Introduction: The Problem With Incremental Updates in a Stagnant Market

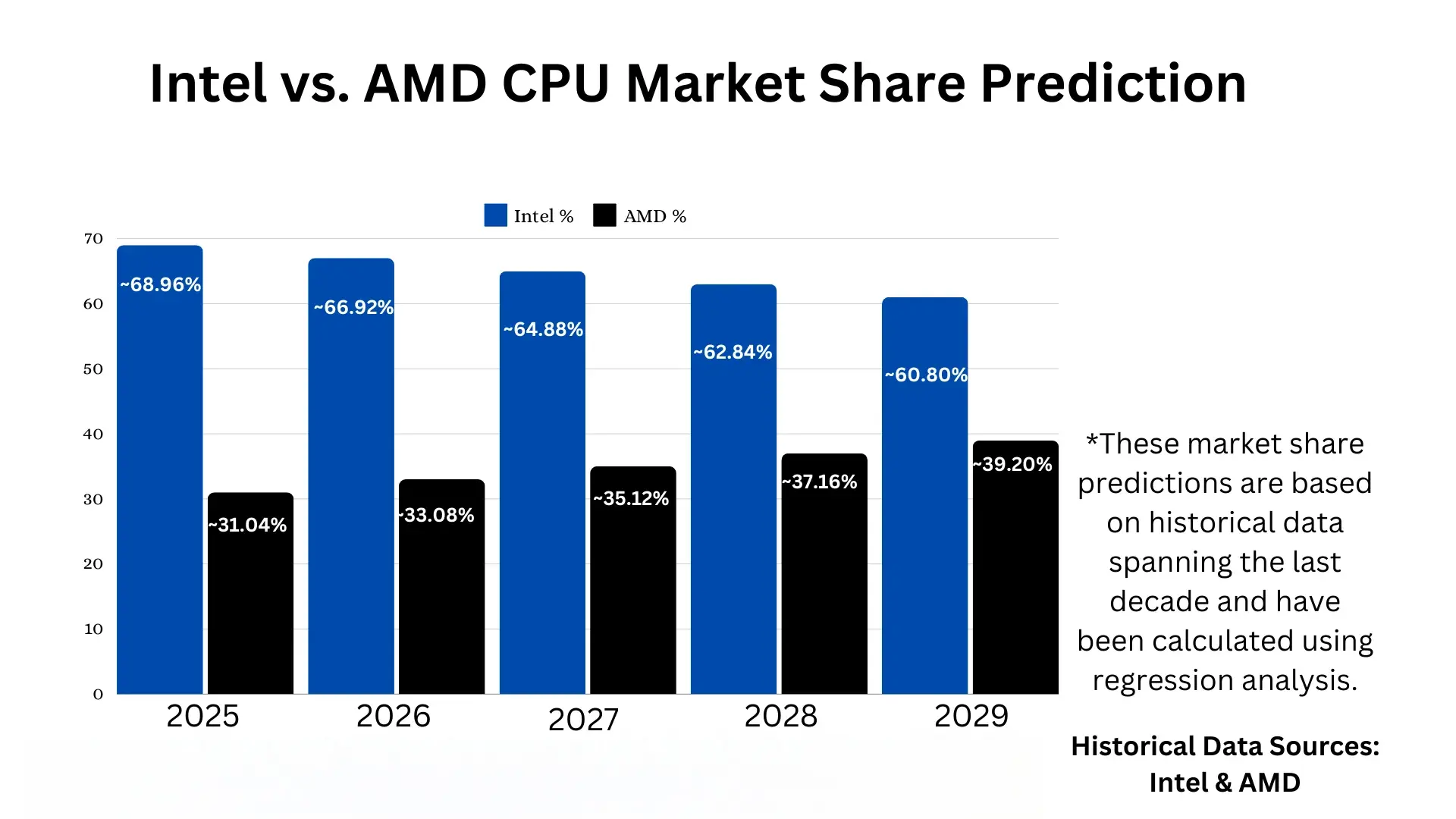

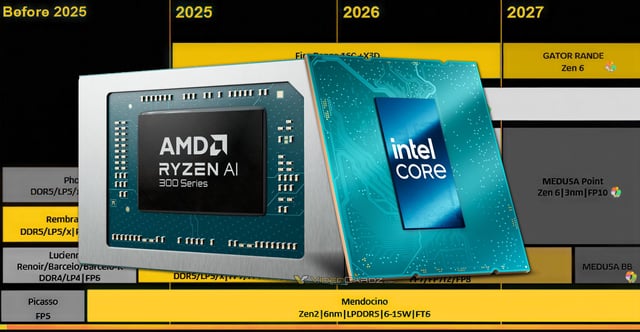

There's a peculiar moment that happens in the CPU market every few years. A major chipmaker stands on stage at a tech conference, announces new processors with fanfare and marketing budget, and then you read the fine print: these chips are basically last year's model with slightly higher clock speeds and adjusted memory support.

This is exactly where AMD finds itself heading into 2026.

The company just announced its Ryzen lineup for the coming year, and it's... fine. Not bad, not exciting—just fine. We're talking about Ryzen AI 400 series laptops, Ryzen AI Max+ variants with different CPU-to-GPU configurations, and a single new desktop chip: the Ryzen 7 9850X3D. If you're expecting revolutionary performance leaps or groundbreaking architecture changes, you'll be disappointed. But if you understand why AMD is taking this approach, the strategy actually starts to make sense.

The semiconductor industry doesn't move as fast as we'd like to believe. Yes, there are genuine innovations happening. But between those innovations, companies need to keep selling products, manage inventory, and maintain product lineups that make sense to customers and retailers. AMD's 2026 announcements are fundamentally about that unglamorous business reality.

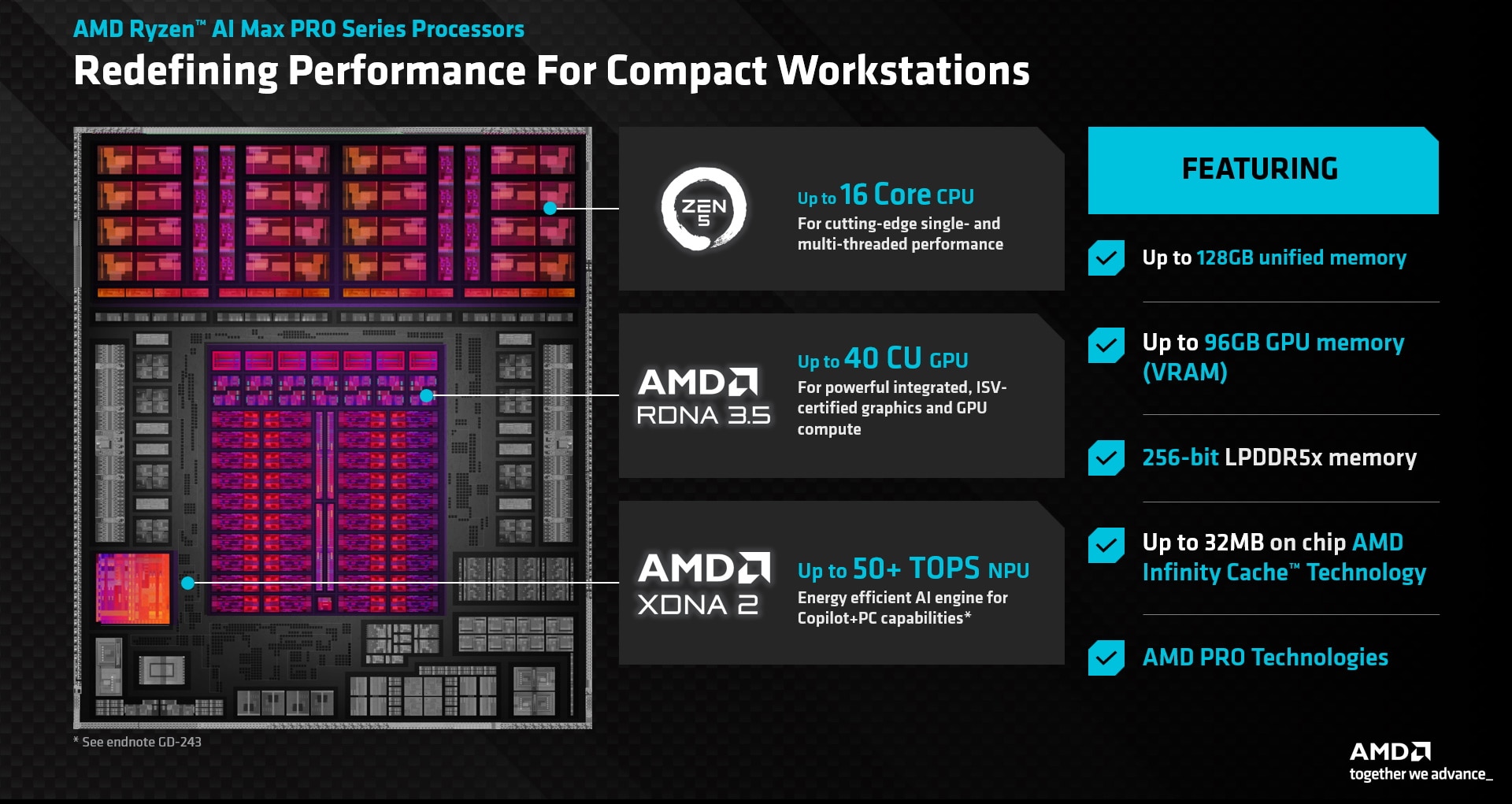

Here's what's actually happening: AMD's Zen 5 architecture, released in 2024, is still competitive. Their RDNA 3 graphics technology still powers gaming laptops effectively. Their 3D V-Cache technology continues to deliver impressive gaming performance. So rather than rush out completely new architectures on compressed timelines, AMD is doing what every mature technology company does—optimizing what already works, addressing specific market gaps, and making sure customers have options at different price points.

But there's more to this story than just "same chips, different clock speeds." Understanding AMD's 2026 strategy requires looking at the broader CPU market dynamics, the constraints of modern semiconductor manufacturing, and the specific customer segments AMD is trying to serve. It's about recognizing that sometimes the most interesting technology story isn't about breakthrough performance, but about intelligent product portfolio management.

Let's dig into what AMD is actually doing, why they're doing it, and what it means for anyone considering a new laptop or desktop system in the coming year.

TL; DR

- Ryzen AI 400 series are incremental updates to 2024's Ryzen AI 300 chips, featuring modest clock speed increases and faster memory support but identical architecture

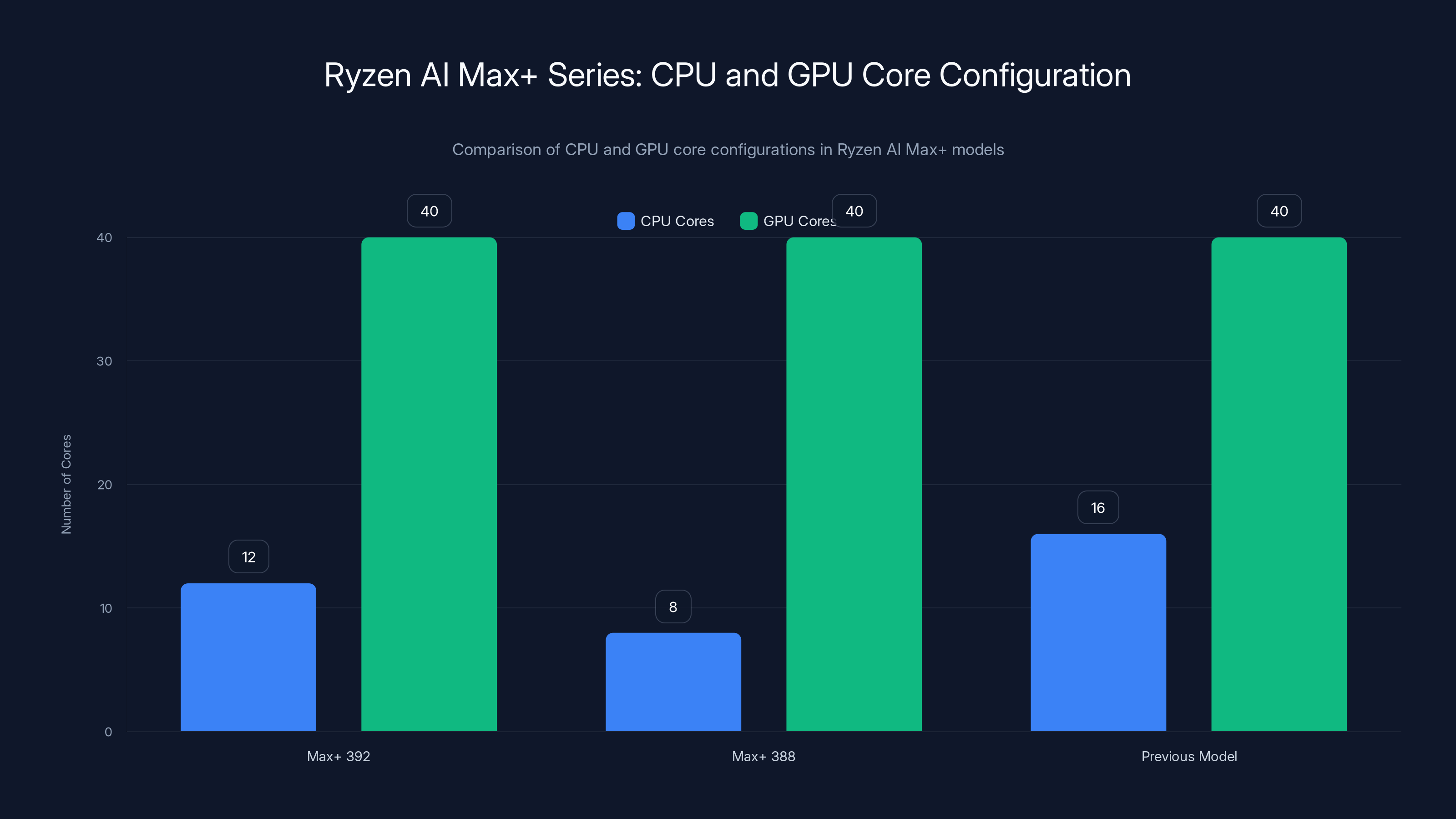

- New Ryzen AI Max+ models offer GPU optimization with full 40-core integrated graphics but reduced CPU cores (12 or 8 instead of 16), creating cheaper options for gaming laptops

- Desktop sees single X3D update: the Ryzen 7 9850X3D boosts clock speeds to 5.6 GHz but remains fundamentally an enhanced Ryzen 7 9800X3D

- RDNA 3 GPUs won't access FSR Redstone tech, missing next-gen graphics upscaling and frame generation features reserved for RDNA 4 dedicated cards

- Bottom line: AMD is optimizing existing architectures rather than innovating, a pragmatic response to competitive pressures and manufacturing realities

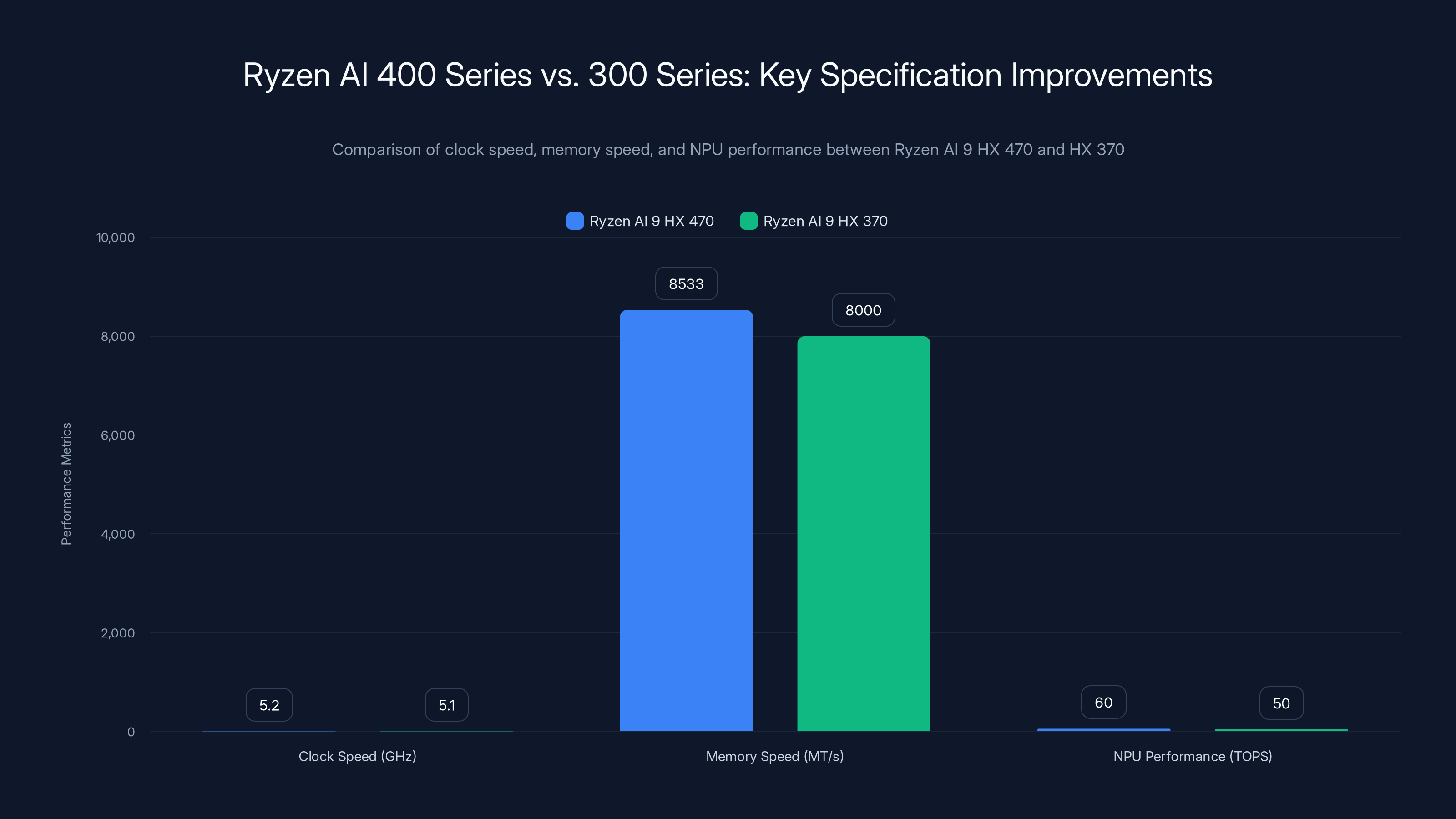

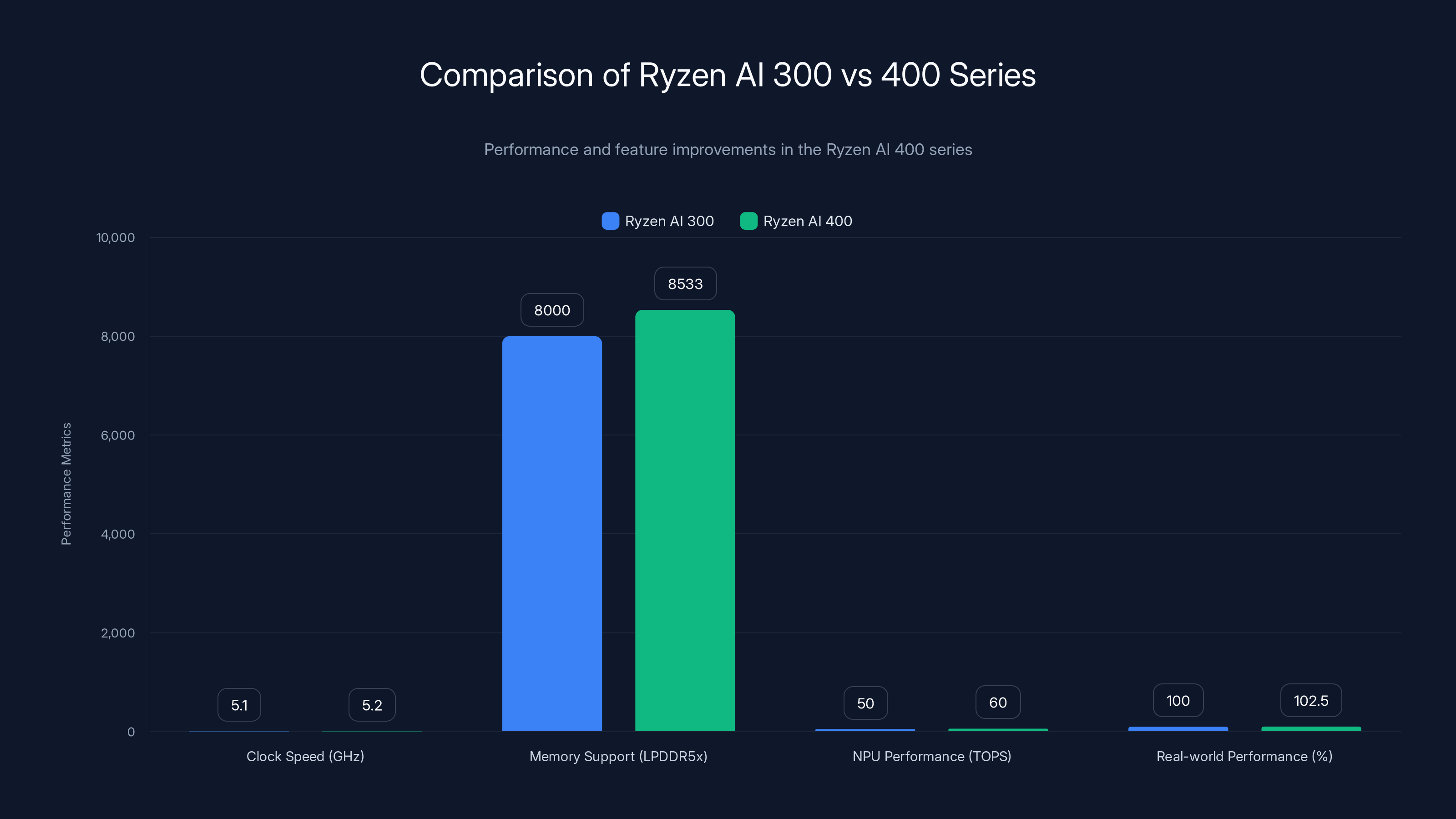

The Ryzen AI 9 HX 470 shows modest improvements over the HX 370 with a 100 MHz increase in clock speed, a 6.6% increase in memory bandwidth, and a 20% boost in NPU performance.

The Ryzen AI 400 Series: Clock Speeds and Memory Speed as Innovation

Let's talk about what AMD considers "new" with the Ryzen AI 400 series, because understanding the modest improvements tells you a lot about where the CPU market actually sits.

The flagship Ryzen AI 9 HX 470 represents the most interesting update here. It gets a 5.2 GHz peak boost clock, up from the Ryzen AI 9 HX 370's 5.1 GHz. That's a 100 MHz increase. For memory, it now supports LPDDR5x-8533, compared to the previous generation's LPDDR5x-8000. The neural processing unit gets bumped from 50 TOPS (trillion operations per second) to 60 TOPS—a 20% improvement in that specific metric.

These are the actual, measurable differences. Let me be clear about what they mean: they're small. A 100 MHz clock speed increase typically translates to roughly 2-3% better performance in CPU-intensive tasks. The memory speed improvement might help in very specific scenarios, particularly when the system is doing massive data transfers. The NPU improvement matters if you're running AI workloads that specifically rely on the neural processor, but for typical laptop use, NPU performance isn't a bottleneck most people experience.

But here's where context matters. AMD is working within genuine constraints. The Ryzen AI 300 series launched in mid-2024 using a proven architecture. That architecture still works well. Pushing toward higher clock speeds on a mature manufacturing process requires more power consumption and generates more heat—neither of which is desirable in thin laptops. So AMD had to make calculated decisions about where those improvements could come from.

Memory speed improvements are particularly interesting because they're one of the few places where you can get legitimate performance gains without pushing the CPU further. LPDDR5x-8533 versus LPDDR5x-8000 represents a 6.6% bandwidth increase. In real-world terms, this means your laptop can move data between system memory and the GPU or CPU more efficiently. If you're doing creative work—video editing, 3D rendering, or gaming—this extra bandwidth can occasionally matter.

The Ryzen AI 400 series shares the exact same building blocks as its predecessor: a mix of Zen 5 performance cores and Zen 5c efficiency cores, between four and sixteen depending on the specific SKU. The integrated GPU still uses RDNA 3, the same architecture that powered the previous generation. The manufacturing process remains TSMC's 4nm node.

This isn't unusual in AMD's recent history. A couple of generations back, the company did something nearly identical with Ryzen 8040 series laptop chips, which were essentially Ryzen 7040 series chips with slightly elevated clock speeds and not much else. The pattern repeats because it's economically sensible: you amortize engineering costs across a longer product cycle, you maintain manufacturing efficiency on proven processes, and you give customers incremental improvements without forcing them into expensive new systems.

Where Ryzen AI 400 Makes Sense

If you're shopping for a laptop in early 2026 and see "Ryzen AI 400 available," the honest assessment is this: if you can find a Ryzen AI 300 system at a meaningful discount because it's considered "last year's model," you should probably take it.

The performance difference won't be noticeable in everyday tasks. You won't feel that extra 100 MHz when you're browsing, writing documents, or even doing moderate video work. The Ryzen AI 400 starts to make a legitimate difference only if you're already pushing these systems hard—running demanding simulations, handling large datasets, or working with sophisticated creative applications simultaneously.

That said, there's a structural reason these updates exist beyond pure performance metrics. Manufacturers and retailers need fresh SKUs. When laptops have the same chip inside, they all look the same to customers on a spreadsheet. New numbering allows OEMs to position products at slightly different price points, justify marketing angles ("new for 2026!"), and manage inventory transitions smoothly.

From a consumer perspective, this means you're not missing anything crucial by going with the previous generation. But if you're buying new anyway and prices are similar, the Ryzen AI 400 series does offer marginally better efficiency and performance headroom, even if it's not a dramatic leap.

The NPU Evolution

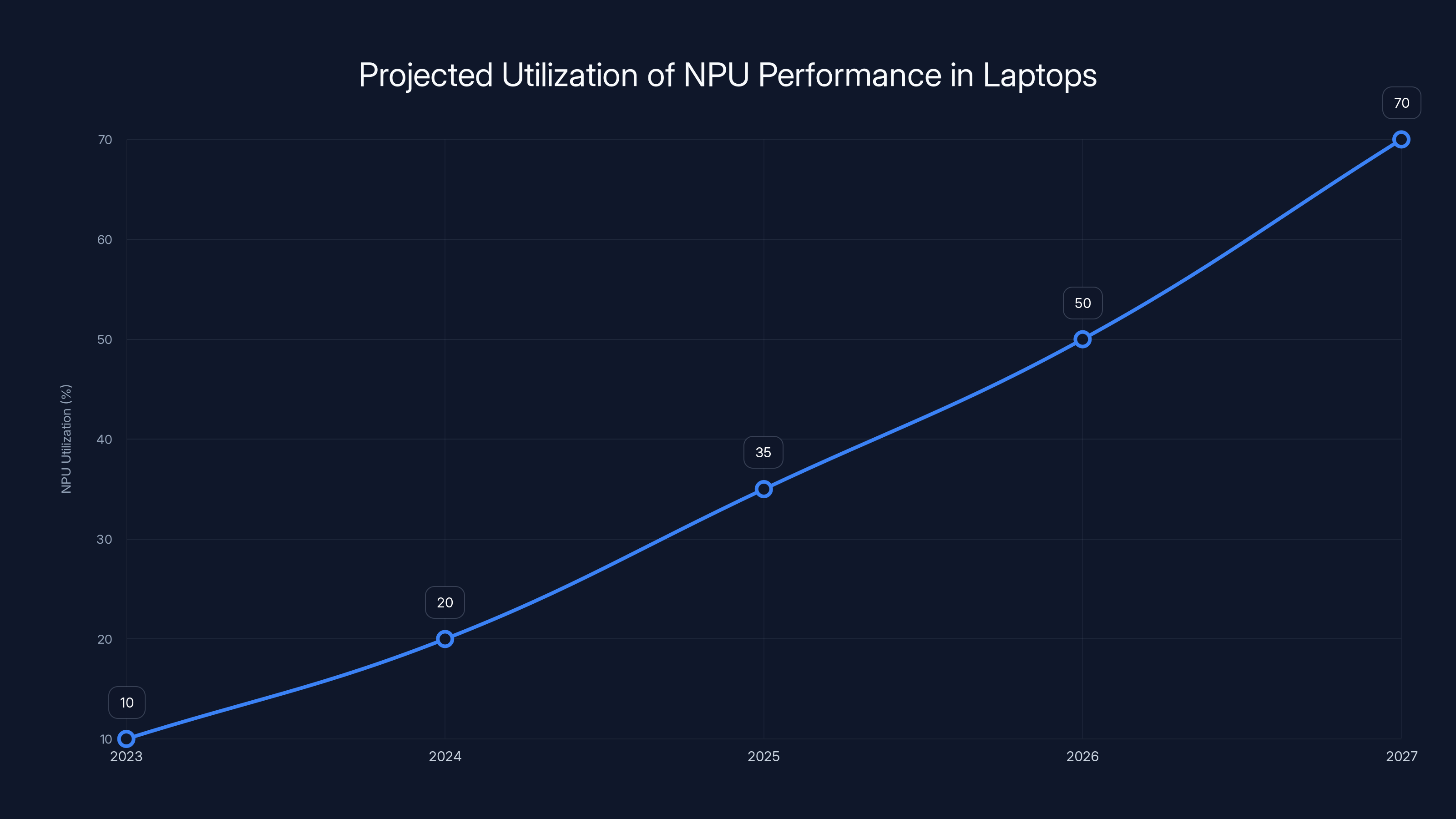

One component worth examining more closely is the neural processing unit. AMD is pushing the AI narrative pretty hard, and rightfully so—AI acceleration has become a genuine selling point for modern laptops.

The jump from 50 TOPS to 60 TOPS isn't magical, but it is meaningful for specific workloads. Tasks like image recognition, natural language processing within local applications, or AI-powered features in creative software do rely on that throughput. If you're using tools that explicitly leverage the NPU—and increasingly, Windows AI features are starting to—that extra 20% capacity could matter.

However, and this is important, most laptop users still won't interact directly with their NPU. Cloud-based AI services handle most of what people think of as "AI" today. Local NPU acceleration is becoming more important, but we're still in the early phases of that transition. In a year or two, once software fully exploits these capabilities, that 60 TOPS figure will look more relevant. Right now, it's preparation for where the market is heading.

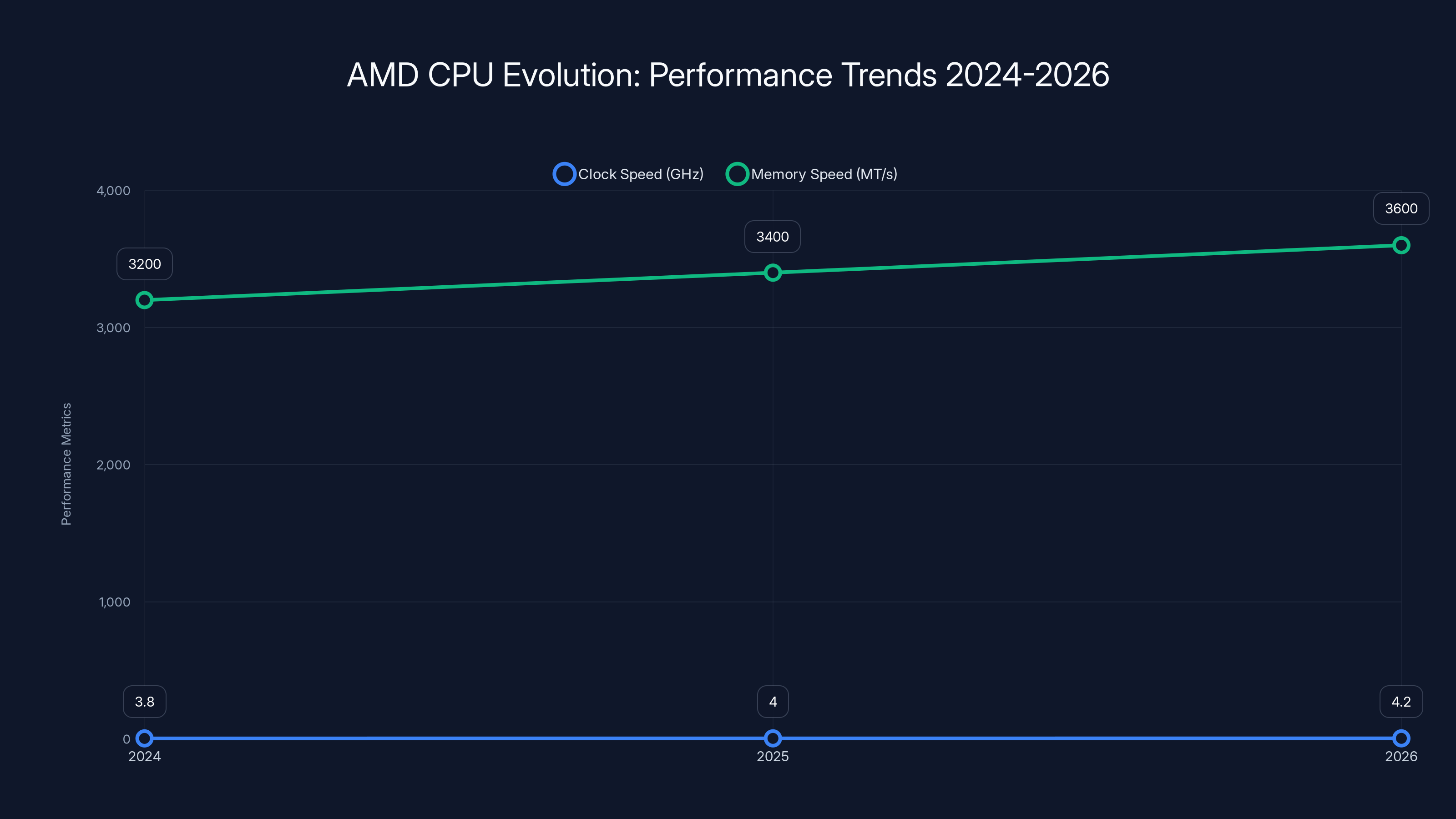

AMD's CPU performance improvements from 2024 to 2026 show modest increases in clock and memory speeds, reflecting an evolutionary rather than revolutionary approach. (Estimated data)

Ryzen AI Max+: GPU Optimization as Product Strategy

Now here's where AMD's 2026 strategy gets actually interesting. The Ryzen AI Max+ 300 series includes two new models—the Max+ 392 and Max+ 388—that represent genuine product line optimization rather than just clock bumps.

Until now, if you wanted a Ryzen AI Max+ CPU with all 40 RDNA 3 graphics cores enabled, you got 16 CPU cores. Period. This made sense from a manufacturing perspective—you produce chips with the full configuration, then disable cores if needed for lower-tier SKUs. But from a market perspective, it created an inefficiency. Some customers, particularly gaming enthusiasts and content creators working with graphics-heavy tasks, don't need all those CPU cores. They want the GPU power without paying for CPU performance they won't use.

AMD is addressing this with the Max+ 392 (12 CPU cores, full 40-core GPU) and Max+ 388 (8 CPU cores, full 40-core GPU). This opens up several interesting possibilities.

First, there's the cost argument. If AMD can reduce the number of enabled CPU cores, they reduce power consumption, heat output, and likely the bill of materials slightly. That translates to cheaper laptops for people who actually need GPU performance more than CPU performance. In practice, this could mean gaming laptops or GPU-accelerated workstations that cost a few hundred dollars less.

Second, there's the performance argument that might seem counterintuitive but is actually valid: for pure GPU-bound gaming, having fewer CPU cores doesn't hurt. Modern games, especially at high frame rates, are increasingly GPU-limited anyway. The CPU bottleneck happens at lower frame rates or very high frame rates over 144fps. In the sweet spot where most gaming happens—100-144fps at high settings—the GPU matters far more than having 16 cores instead of 12.

Third, this is smart marketing. It gives OEMs more configuration options, which means more SKUs at different price points. More SKUs means better shelf presence and more ways for customers to find something that fits their budget and actual needs.

Gaming Laptop Implications

For gaming laptop buyers, this is worth understanding. The Ryzen AI Max+ chips already featured integrated GPUs that could genuinely compete with entry-level discrete graphics cards like an NVIDIA RTX 3050. They don't match higher-end discrete GPUs, but for 1440p gaming at medium-to-high settings, they're competent.

The new 392 and 388 models will let manufacturers build gaming laptops without those beefy 16-core CPUs, which means they can reduce system prices while maintaining the same GPU performance. For the specific use case of "I want to game and maybe do some light streaming," a Max+ 392 is probably perfectly adequate and cheaper than the full-fat 16-core variant.

However—and this is a meaningful caveat—gaming laptop performance is complicated. You need not just the GPU, but also sufficient RAM bandwidth, proper cooling, and adequate power delivery. A cheaper laptop built around the 392 or 388 might have inferior cooling or slower RAM, which could actually hurt performance more than the reduced CPU cores help with cost.

This is why seeing actual review units matters before making a purchase. The raw specs might suggest the Max+ 392 is a great value, but if the laptop manufacturer cheaped out on cooling or RAM to hit that lower price point, you might actually be getting worse overall performance.

The GPU Cores That Don't Upgrade

Here's a critical limitation that AMD is being fairly transparent about: these Ryzen AI Max+ chips use RDNA 3 graphics architecture. That matters because AMD just announced something called FSR Redstone for its dedicated RDNA 4 graphics cards, and integrated RDNA 3 GPUs will never access those features.

FSR Redstone represents AMD's answer to NVIDIA's DLSS technology suite. It includes graphics upscaling (running games at lower resolution, then upscaling to your monitor's native resolution using AI) and frame generation (AI-created intermediate frames to boost frame rates). These are becoming table-stakes features in gaming. NVIDIA has had DLSS frame generation for a while, and their newer hardware supports more sophisticated versions. AMD is catching up with RDNA 4.

But here's the problem: RDNA 3, which is in all these Ryzen AI chips, doesn't have the hardware structures needed for Redstone. It can run older FSR versions (which do basic upscaling but no frame generation), but it can't do what RDNA 4 can do.

This creates a subtle but real problem for gaming laptop buyers. If you buy a Ryzen AI Max+ laptop in 2026, you're getting a machine that will be increasingly left behind in game support over the next few years. Games are going to assume frame generation is available. DLSS frame generation will be the default quality setting for NVIDIA systems. Games optimized for Xbox Series X (which has AMD hardware) will increasingly expect frame generation capabilities. Ryzen AI Max+ laptops won't have that.

It's not a dealbreaker for today's games. But if you're planning to keep the laptop for 3+ years and care about gaming performance, it's something to keep in mind.

The Desktop Story: One Chip to Rule Them... Slightly

If you're a desktop builder looking for something new from AMD in 2026, you're getting the Ryzen 7 9850X3D. That's it. One new socketed AM5 processor.

Let's be clear about what this is: it's a Ryzen 7 9800X3D with better clock speeds. The 9850X3D boosts to 5.6 GHz versus the 9800X3D's 5.2 GHz. Both use the exact same core configuration: 8 Zen 5 cores with 64 MB of 3D V-Cache stacked on top.

The 3D V-Cache is AMD's secret sauce for gaming and single-threaded performance. It's a massive on-die cache that's almost as large as the main processor cores themselves. This cache is so large and so fast that it eliminates most memory bottlenecks in gaming workloads, resulting in dramatically better frame rates compared to equivalent chips without the V-Cache.

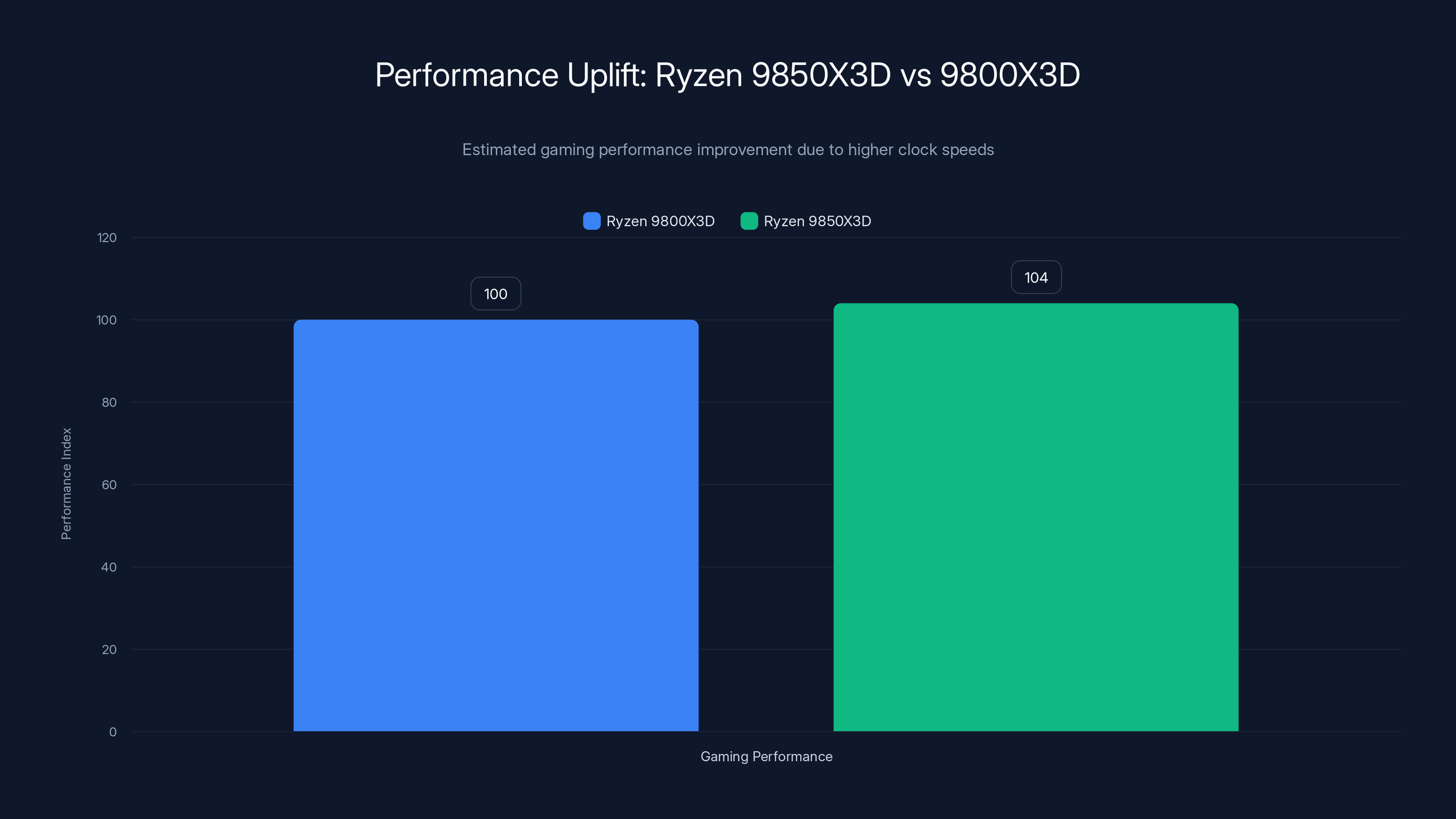

The 9800X3D already offers exceptional gaming performance. The 9850X3D makes it incrementally better through those 400 MHz higher clock speeds. The performance uplift is meaningful—probably 3-5% better in gaming workloads, potentially more in certain games—but it's not transformative.

Here's why AMD probably made this decision: the Ryzen 9000 desktop lineup is already strong. AMD's position in gaming is solid. They don't need to revolutionize the desktop market right now. Instead, they need to keep giving existing customers a reason to upgrade, keep performance moving forward incrementally, and avoid disrupting the current market where Ryzen 7000 and 9000 series chips are still selling well.

The V-Cache Economics

3D V-Cache is an expensive feature. It adds manufacturing complexity, requires additional packaging steps, and increases defect rates compared to standard chip designs. This is why only the top-end gaming chips get the feature. AMD can't make a $200 Ryzen 5 with full V-Cache. The economics don't work.

The 9850X3D gives enthusiasts a path to upgrade. If you have a 9700X3D or an older Ryzen 7000 chip, stepping to the 9850X3D is a clear performance gain. Not huge, but real. For someone who bought a 5000X3D or 7000X3D a year or two ago, the 9850X3D offers enough improvement to justify the motherboard swap and CPU upgrade if they're a performance enthusiast.

But for someone with a 9800X3D? The upgrade logic is weaker. You're paying a lot for a 400 MHz clock speed bump. That's not compelling unless you're running into specific performance limits with your current system.

Where Desktop CPUs Actually Stand

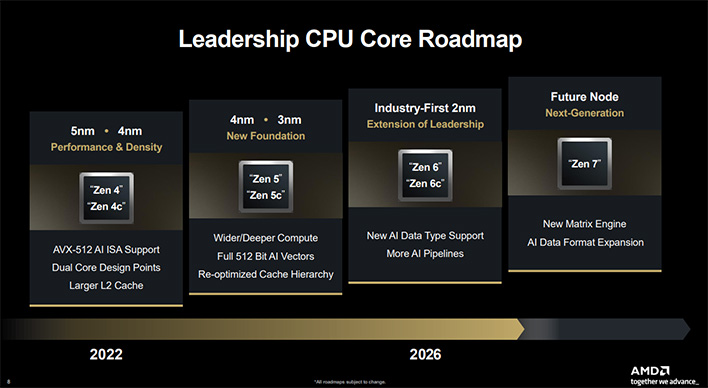

It's worth stepping back and acknowledging where desktop CPUs sit in the product cycle. We're nearly two years into the Ryzen 9000 series now. Zen 5 launched in 2024. Before that came Zen 4, which is still competitive.

AMD's desktop CPU architecture is mature and strong. It's not exciting anymore—and that's actually fine. The mid-2020s are a weird time in CPUs. Performance has plateaued. The last generation is still plenty fast for almost everything. The gains year-over-year are in the 5-10% range at best.

If you're building a PC in early 2026, a Ryzen 7 7700X or Ryzen 9 7950X3D from 2023 is still plenty capable. The 9850X3D is better, sure, but not "must-have" better unless you're chasing frame rates in competitive gaming or doing specialized computational work.

This is why AMD probably isn't rushing out Zen 6 or completely new desktop architectures. They're not in a desperate competitive situation. Intel's latest chips have been competitive, but AMD's position is solid. The smart play is to keep the current architecture optimized, push incremental improvements, and work on the next big thing in parallel.

The Ryzen 9850X3D offers an estimated 4% performance improvement in gaming workloads over the 9800X3D due to its higher clock speeds. Estimated data.

The Elephant in the Room: Why Innovation Has Slowed

Underlying all these incremental updates is a fundamental question: why isn't AMD pushing bigger changes?

The answer is manufacturing reality. Getting from one generation of CPU architecture to the next requires years of engineering. TSMC's process node advancement follows Moore's Law, but that's slowing down. Getting to 2nm from 3nm takes time. Getting from 3nm to the next node is proving harder than previous transitions.

AMD is balancing several competing pressures. They need to deliver products regularly. They need to keep customers engaged with "new" offerings even when the fundamental architecture hasn't changed. They need to manage inventory and transitions smoothly. They need to wait for manufacturing processes to mature enough to make new architecture viable.

Zen 5 was released in 2024. It represented real improvements over Zen 4: better per-clock performance, better efficiency, better integrated graphics. But Zen 5 isn't dramatically different from Zen 4. The core designs are similar. The manufacturing process moved from 5nm to 4nm, but that's incremental node advancement, not a revolutionary jump.

Zen 6 is presumably in development somewhere. But rushing out an incomplete or barely-different architecture just to hit a specific release date makes no sense. Better to perfect what you have, optimize it for specific use cases (like 3D V-Cache for gaming), and save the architectural changes for when you have something genuinely better to introduce.

The Manufacturing Constraint

There's also a manufacturing perspective most people overlook. TSMC's 4nm process is mature now. It's stable. It's efficient. Yields are good. Transitioning to a new node—whether that's TSMC's 3nm or N3E or whatever comes next—introduces risk. New nodes have lower yields initially. They require different design techniques. They increase costs per chip until volumes ramp and processes stabilize.

Making incremental improvements on a mature node is actually a reasonable engineering decision. You get better margins on proven manufacturing, and you can invest in making sure the next architectural generation is truly better rather than just "designed for a new node."

This is frustrating for people who want CPU innovation to continue accelerating. But it's the reality of semiconductor manufacturing in the late 2020s. The easy gains have been taken. Getting the next wave of performance requires better architecture design, smarter software optimization, and sometimes specialized approaches like V-Cache that add complexity and cost.

NPU Evolution and the AI Accelerator Trend

One trend worth diving deeper into is the neural processing unit acceleration that AMD is pushing in both the Ryzen AI 400 series and previous generations.

NPUs represent a recognition that AI workloads are becoming more common in laptops. Unlike the cloud-based AI that powered the last decade, local AI is starting to become a thing. Windows 11 is integrating AI features that can run locally. Applications are starting to leverage local NPUs for features like image enhancement, noise cancellation, and language processing.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: most laptops' NPUs are underutilized today. AMD is selling 60 TOPS of NPU performance when most applications need a fraction of that. This will change as software catches up, but we're not there yet.

The reason AMD keeps pushing NPU improvements is forward-looking. The infrastructure exists now. The hardware is there. When software eventually demands it—and it will—Ryzen AI systems will already have the capability. For AMD, marketing 60 TOPS is a way to signal "we're ready for the AI future" even if today's software isn't fully prepared.

This is smart product strategy. It builds the installed base. It gives developers a reason to write software that targets these systems. It positions AMD ahead of the curve when the infrastructure actually matters.

But from a buying perspective, if you're considering a laptop purchase, the NPU improvement from Ryzen AI 300 to 400 probably won't affect your real-world experience in 2026. It's a foundation for 2027 and beyond.

The Ryzen AI 400 series offers modest improvements over the 300 series, including a 100 MHz increase in clock speed, enhanced memory support, and a 10 TOPS boost in NPU performance. Real-world performance sees an incremental 2-3% improvement. Estimated data for real-world performance.

The Gaming Graphics Gap: RDNA 3 vs RDNA 4

Let's dig into one specific technical limitation that deserves more attention: the graphics architecture gap between integrated RDNA 3 and the dedicated RDNA 4 in high-end Radeon cards.

RDNA 3 was released in 2023 for dedicated cards and integrated into Ryzen processors in 2024. It's a good architecture. It competes reasonably well with NVIDIA's RTX 4000 series equivalents. For gaming at 1440p and below, RDNA 3 integrated GPUs in Ryzen AI Max+ chips are entirely viable.

RDNA 4 represents the next generation. It's more power-efficient, supports new instructions, and most importantly, includes hardware specifically designed for frame generation and advanced upscaling. These features enable techniques like temporal upsampling where AI reconstructs frames at higher resolution from lower-resolution input.

The problem is architectural. You can't retrofit frame generation support into RDNA 3. The fixed-function hardware units that handle the compute and data movement for frame generation don't exist in RDNA 3. It's like asking a car from 2019 to support a 2026 infotainment system—you can't just update the software; the underlying hardware isn't there.

This creates a weird middle ground for Ryzen AI Max+ gaming laptops. They're competitive today. But by 2027-2028, as games start assuming frame generation is available as a default feature, these laptops will feel increasingly dated. A system with RDNA 4 discrete graphics will be able to run new games at 60+ fps with upscaling and frame generation. A Ryzen AI Max+ laptop will hit 30-40 fps if it wants to match the visual quality without upscaling tricks.

It's not a disqualifier if you're planning to buy a gaming laptop in early 2026 and upgrade in 3-4 years. But if you want longevity and don't want to feel like your GPU is holding you back, this is worth considering.

Product Portfolio Strategy and Market Segmentation

Among all these chips—Ryzen AI 400, Ryzen AI Max+ variants, the 9850X3D—there's a coherent portfolio strategy emerging.

AMD is creating fine-grained market segmentation. Want a cheap Ryzen AI laptop for office work? There's a SKU. Want gaming in a thin-and-light form factor? Max+ 388 with 8 cores and a massive GPU. Want a gaming desktop? 9850X3D with gaming-focused cache. Want a workstation? Different SKU.

This segmentation serves multiple purposes. First, it lets OEMs position products more precisely. Instead of "here's the Ryzen AI laptop" and "here's the gaming Ryzen AI laptop," manufacturers can now offer five different configurations that hit five different price points and use case scenarios.

Second, it uses manufacturing efficiency. AMD doesn't have to make chip variants specifically for each market segment. They make chips, test them, and enable or disable cores based on defects and market demand. The Max+ 392 and 388 probably aren't entirely separate products; they're likely the same chip with different cores enabled.

Third, it extends the product lifespan. A generation of chips that might have felt stale with two configurations feels fresher with five. It gives customers and reviews something "new" to write about even though the underlying technology is the same.

From a business perspective, this is smart. From an innovation perspective, it's keeping the lights on while waiting for the next big thing.

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in NPU utilization as software catches up with hardware capabilities, reaching 70% by 2027.

The Real Problem: Waiting for Process Innovation

Here's the uncomfortable broader truth: CPU innovation is currently bottlenecked by manufacturing processes more than architecture.

The jump from 5nm to 3nm to 2nm is real progress, but each transition takes time and money. Getting to 2nm with reasonable yields and reasonable costs takes years. TSMC and other fabs are pushing hard, but it's slower than the pace we saw from 2015-2020 when Moore's Law was still easily achievable.

Until the next major process node is mature enough for high-volume production, CPU companies can't achieve the kind of performance and efficiency leaps that make architectures feel revolutionary. You can optimize your current architecture all you want, but you're ultimately constrained by the size and speed of your transistors.

AMD is in good position here. They have access to TSMC's latest nodes. They have sufficient revenue to invest in architectural R&D. But they're also wise enough not to force out incomplete architectures just to hit quarterly targets. Zen 6 will come, probably with TSMC's next matured node. When it does, it'll likely have meaningful improvements. Until then, incremental updates make perfect sense.

This is genuinely frustrating if you're enthusiast who wants cutting-edge performance. But it's actually healthy for the industry. AMD isn't burning resources on dead-end designs. They're investing where it matters and shipping products that work well today.

Competitive Context: What Intel and NVIDIA Are Doing

Understanding AMD's strategy requires understanding what the competition is doing.

Intel's latest Meteor Lake processors (Core Ultra, released late 2024) represent their push into integrated graphics and AI acceleration. They're competitive but not dramatically ahead of Ryzen AI. Intel's stuck in their own process transition problems (Intel 7, Intel 4, eventually Intel 3), which makes it harder for them to push aggressive clock speeds.

NVIDIA doesn't sell traditional CPUs anymore. They've focused on GPUs and accelerators. This means AMD doesn't have a direct competitor in the integrated graphics space—it's AMD against Intel's integrated graphics. And AMD is winning that fight with RDNA 3.

On the discrete GPU side, AMD's RDNA 4 is coming but behind schedule. NVIDIA already has Ada and will soon have Blackwell. AMD is playing catch-up, which might explain why they're not rushing out completely new GPU architectures in integrated form factors. The engineering resources are focused on getting RDNA 4 right for discrete GPUs.

This context shows that AMD's incremental update strategy isn't lazy or unprepared. It's strategic. They're solid on CPUs, competitive on integrated graphics, and working hard on discrete GPUs. Trying to innovate everywhere simultaneously would spread them too thin.

The new Ryzen AI Max+ models offer full GPU core performance with fewer CPU cores, optimizing for GPU-intensive tasks and potentially reducing costs.

The Thermal and Power Consumption Reality

One aspect that doesn't get discussed enough: thermal envelopes and power limits.

Laptops have strict thermal and power budgets. A gaming laptop can probably dissipate 100-150W continuously. An ultrabook might be limited to 25-30W. These limits are hard physical constraints set by the laptop's cooling solution, battery, and power delivery circuitry.

When you hit those limits, you can't just push more voltage into the CPU and get higher clock speeds. You have to make a choice: increase clock speed and let the system run hotter, or accept the existing clock speed ceiling.

AMD's decision to boost from 5.1 GHz to 5.2 GHz on the Ryzen AI 9 HX 470 was probably made after careful thermal analysis. They determined they could add 100 MHz without exceeding thermal budgets in thin gaming laptops. Pushing further—say, to 5.4 GHz—might require thicker cooling solutions, more expensive power delivery, or accepting that the chip would thermal throttle in thin-and-light laptops.

This is why memory speed improvements are interesting: they provide performance gains without adding heat. LPDDR5x-8533 is faster, but not substantially more power-hungry than LPDDR5x-8000. It's a clever way to eke out performance without hitting thermal ceilings.

This manufacturing and thermal reality is invisible to most users, but it's fundamental to why CPU designs look the way they do.

Looking Forward: What's Actually Coming

If you're wondering when AMD will do something genuinely new, here's the likely timeline.

Zen 6 is presumably in development. Based on AMD's past patterns, it'll probably arrive in late 2026 or 2027. It'll likely be built on a more advanced TSMC node (probably 3nm or its successor). It'll have architectural improvements: better instruction-level parallelism, better branch prediction, better cache hierarchies, improved vector instruction support.

For mobile, AMD is probably working on next-generation Ryzen AI chips that will use RDNA 4 or its successor for integrated graphics. That's what will truly obsolete the Max+ 300 series—not more clock speed, but new GPU architecture with frame generation capabilities.

For desktops, AMD probably has Zen 6 X3D variants in the pipeline. Getting V-Cache working with new architectures requires new design approaches, so there's always a delay between the standard architecture and the V-Cache variants.

But all of this is coming in 2026-2027 timeframe at the earliest. For now, 2025-2026 is about optimization, not innovation. That might feel disappointing, but it's actually reasonable engineering.

Practical Buying Advice: What Should You Actually Buy?

If you're shopping for a laptop in early 2026, here's honest guidance.

For gaming laptops, the Ryzen AI Max+ 300 series (whether the new 392/388 models or the older 16-core variants) are legitimately competitive. They're not better than discrete RTX 4070 systems, but they're cheaper, they run cooler, and they don't require dedicated GPU power delivery. If gaming is important but you also care about price and portability, Max+ is worth serious consideration.

Just understand the RDNA 3 limitation. You're getting current-generation gaming capability, but you're buying into an architecture that won't support next-gen frame generation. Plan to upgrade the whole system in 3-4 years if gaming stays important.

For productivity laptops, Ryzen AI 400 series is fine. The Ryzen AI 9 HX 470 or even the mid-range Ryzen 7 AI chips are overkill for most work. They'll comfortably handle multitasking, video calls, and moderately heavy creative work. The 100 MHz clock bump over the 300 series won't be noticeable in real work.

For desktops, the 9850X3D is a solid gaming chip if you need a new CPU. If you have a 9800X3D, the upgrade isn't compelling unless you're already hitting performance limits. If you have a 7000-series chip, the upgrade is worth considering if you play games at high frame rates (120+ fps).

For everything else, the previous generation's parts are probably fine. There's no reason to wait for 2026 chips if you need a system now.

The Bigger Picture: Maturity Signals in the CPU Market

What AMD's 2026 announcements really signal is that the CPU market has reached maturity.

We're well past the days when new CPU generations delivered 50% performance improvements. We're in an era where 5-10% yearly improvement is actually pretty good. That's not necessarily bad—it means computers have gotten good enough for most people. An eight-year-old CPU still does most of what people need.

For AMD, pushing marginal improvements while infrastructure catches up (manufacturing nodes maturing, software making use of NPUs, next architecture launching) is the right move. It keeps the product line fresh, it extends margins on proven architecture, and it buys time for the next innovation.

For consumers, it means that older systems are still viable, incremental upgrades are less compelling, and waiting for the next big thing is often a smarter buy than chasing the latest marginal improvement.

It's not as exciting as the mid-2010s when every new generation felt revolutionary. But it's a more mature, stable market. And there's something to be said for that.

Conclusion: Evolution Over Revolution

AMD's 2026 CPU announcements are anticlimactic if you expect revolutionary performance leaps. They're modest clock speed bumps, modest memory speed improvements, and intelligent market segmentation using the same architecture from 2024-2025.

But they're entirely reasonable given where the market sits. The Zen 5 architecture is proven and competitive. RDNA 3 integrated graphics are legitimately capable. 3D V-Cache technology works well for gaming. There's no compelling reason to abandon these approaches just to announce something more dramatic.

Instead, AMD is optimizing what works. They're creating more SKU variety to serve different market segments better. They're giving customers incremental reasons to upgrade without forcing revolutionary technology shifts. And they're buying time for genuinely new architectures to mature in parallel.

From an engineering standpoint, this is how mature technology markets actually function. You don't innovate everywhere simultaneously. You innovate strategically, optimize what's proven, and phase out what's becoming obsolete on your own timeline, not on a quarterly announcement schedule.

If you're shopping for a system in early 2026, the Ryzen AI 400 series and Ryzen 9850X3D represent solid choices, but they're not must-haves if you have comparable recent-generation chips. The real innovation is probably arriving in late 2026 or 2027 when Zen 6 and next-generation GPU architectures launch.

Until then, AMD's approach is pragmatic. It keeps customers happy, keeps the engineering pipeline healthy, and acknowledges the reality that revolutionary CPU innovation has slowed down not because of any single company's choices, but because of fundamental physical constraints in semiconductor manufacturing.

The most interesting CPU story in 2026 might not be what AMD announces. It might be what you can buy used or at discount from previous generations. Sometimes the smart play is recognizing when incremental updates truly are incremental—and not falling for the marketing narrative that marginal improvements are reasons to upgrade everything.

Use Case: Need to automate technical comparisons and competitive analysis reports for product launches? Runable can generate these automatically from data inputs.

Try Runable For Free

FAQ

What makes the Ryzen AI 400 series different from the 300 series?

The Ryzen AI 400 series features modest improvements over the 300 series: clock speeds increased by 100 MHz (from 5.1 GHz to 5.2 GHz on the flagship), memory support improved to LPDDR5x-8533 from LPDDR5x-8000, and NPU performance increased from 50 TOPS to 60 TOPS. However, the fundamental architecture—Zen 5 CPU cores and RDNA 3 GPU cores—remains identical. Real-world performance difference is typically 2-3%, making these updates incremental rather than revolutionary.

Should I wait for Ryzen AI 400 or buy a Ryzen AI 300 laptop now?

If you need a laptop today, buying a discounted Ryzen AI 300 system is perfectly reasonable. The performance difference won't be noticeable in everyday tasks. However, if you're comparing systems at similar prices and one has the Ryzen AI 400, the newer chip offers slightly better future-proofing and memory bandwidth. The real decision should be based on price and other laptop features (display, build quality, cooling) rather than the CPU generation.

What is RDNA 3 and why does it matter for gaming?

RDNA 3 is AMD's GPU architecture used in Ryzen AI Max+ integrated graphics and older Radeon dedicated cards. It's fully capable of handling 1440p gaming at medium-to-high settings, but it lacks hardware support for frame generation—a new feature available only in RDNA 4 (the newer architecture in 2026 dedicated GPUs). Games increasingly rely on frame generation for performance, so RDNA 3 integrated GPUs will gradually feel outdated for gaming over the next 2-3 years.

Is the Ryzen 7 9850X3D worth upgrading to from the 9800X3D?

Only if you're pushing gaming frame rates consistently above 100 fps in competitive games or running specialized computational workloads. The 9850X3D offers a 400 MHz clock speed bump (5.6 GHz vs 5.2 GHz), which translates to roughly 3-5% better gaming performance. If your 9800X3D is meeting your performance targets, the upgrade isn't compelling. However, if you're building a new system and gaming performance matters, the 9850X3D is worth the extra cost over the 9800X3D.

What does NPU (Neural Processing Unit) do and should I care about it?

The NPU is a specialized processor designed to accelerate AI workloads locally on your laptop. While the Ryzen AI 400 series features a 60 TOPS NPU (compared to 50 TOPS in the 300 series), most current software doesn't fully utilize these capabilities. As of early 2026, NPU improvements are more about future-proofing than current performance. Windows AI features and AI-powered creative tools are beginning to leverage NPUs, but the real benefit will become apparent in 2027 and beyond as software catches up to the available hardware.

Why doesn't AMD release Zen 6 desktop chips if Zen 5 feels outdated?

Zen 5 isn't actually outdated—it remains highly competitive, and the performance gains from major architectural changes are only achieved when paired with advanced manufacturing process improvements. AMD is waiting for TSMC to mature the next-generation process node (likely 3nm or beyond) before launching Zen 6, ensuring the new architecture can properly exploit the enhanced manufacturing capabilities. Rushing out Zen 6 on the current 4nm process would provide minimal benefits and waste engineering resources better spent perfecting the design for a more advanced node.

What is 3D V-Cache and which chips have it?

3D V-Cache is AMD's stacked memory technology that adds a massive on-die cache layer to CPU cores, dramatically improving gaming performance by reducing memory bottlenecks. Only high-end gaming chips feature it: currently the Ryzen 7 9800X3D and the new Ryzen 7 9850X3D for desktops, and various Ryzen AI Max+ models for laptops. The massive cache eliminates typical CPU-to-memory bandwidth limitations in gaming, resulting in 20-30% better frame rates compared to equivalent chips without V-Cache.

Are older Ryzen generation chips still worth buying in 2026?

Absolutely. The Ryzen 7000 series (released in 2022) and Ryzen 5000 series (2020-2021) remain entirely competent for gaming and productivity work. CPUs have reached a maturity point where generation-to-generation improvements are small. If you find a deal on older Ryzen chips, the performance difference compared to 2026 models won't be game-changing for most workloads. The decision should be based on your specific performance needs and budget rather than chasing the newest generation.

Quick Takeaway

AMD's 2026 CPU announcements are evolutionary, not revolutionary. Ryzen AI 400 chips offer modest clock and memory speed improvements, new Ryzen AI Max+ configurations provide better GPU-to-CPU ratios for gaming, and the Ryzen 7 9850X3D increments gaming performance on proven architecture. While these updates feel underwhelming compared to historical leaps, they're strategically sound in a maturing market where next-generation architecture requires manufacturing process improvements not yet widely available. Buyers should focus on actual needs rather than generational numbers—last year's chips still deliver solid performance in 2026.

Key Takeaways

- Ryzen AI 400 series improvements are modest: 100 MHz clock boost and LPDDR5x-8533 support, same Zen 5 and RDNA 3 architecture as 2024 generation

- New Ryzen AI Max+ 392 and 388 models optimize for gaming by offering full 40-core GPUs with reduced 12-core or 8-core CPU configurations

- Ryzen 7 9850X3D brings 5.6 GHz clock speeds to proven 3D V-Cache gaming formula, offering 3-5% performance improvement over 9800X3D

- RDNA 3 integrated GPUs lack frame generation hardware support, putting Ryzen AI Max+ systems at disadvantage versus RDNA 4 for future game titles

- AMD's incremental update strategy reflects manufacturing and thermal constraints, not lack of innovation—next major architecture requires process node maturity

Related Articles

- AMD Ryzen AI 400 Series: Complete Guide & Developer Alternatives 2025

- Alienware's New Slim and Budget Gaming Laptops [2025]

- HP's Keyboard Computer: The Eliteboard G1a Explained [2025]

- Vivoo FlowPad: Smart Menstrual Pad Hormone Testing [2025]

- Eureka Z50 Mopping Robot: Smart Carpet Shield Technology [2025]

- NAOX EEG Wireless Earbuds: Brain Monitoring Technology [2025]

![AMD's 2026 CPU Strategy: Why Incremental Ryzen Updates Matter [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/amd-s-2026-cpu-strategy-why-incremental-ryzen-updates-matter/image-1-1767672745485.jpg)