Ancient Homo Erectus Fossils from China Reveal Rapid Human Migration Out of Africa

When scientists re-examine old fossils with new technology, sometimes the story changes completely. That's exactly what happened with two skulls discovered in Yunxian, China, over two decades ago. For years, researchers debated what these remains represented and how they fit into the broader picture of human evolution. Then came 2025, and a team of paleoanthropologists applied cutting-edge dating techniques that would fundamentally reshape our understanding of when and how our ancient ancestors first conquered continents.

The headlines made it sound dramatic: skulls once thought to be a million years old turned out to be far older. But the real story runs much deeper. These fossils aren't just older than we thought—they're forcing us to completely reconsider how quickly Homo erectus, the extinct common ancestor of modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans, managed to spread across the globe. We're talking about a period of human prehistory so distant that it's almost incomprehensible, yet the evidence locked in ancient stone and bone tells a tale of remarkable adaptation and migration.

Here's what makes this discovery particularly significant: if Homo erectus could spread from Africa to both Georgia and central China in just 130,000 years, then we've been vastly underestimating the capabilities of our ancient ancestors. These weren't slow, hesitant explorers. They were survivors who could navigate unfamiliar landscapes, adapt to new climates, and establish populations across an enormous geographic range. This reframing doesn't just affect how we think about a single species—it changes how we understand human evolution itself.

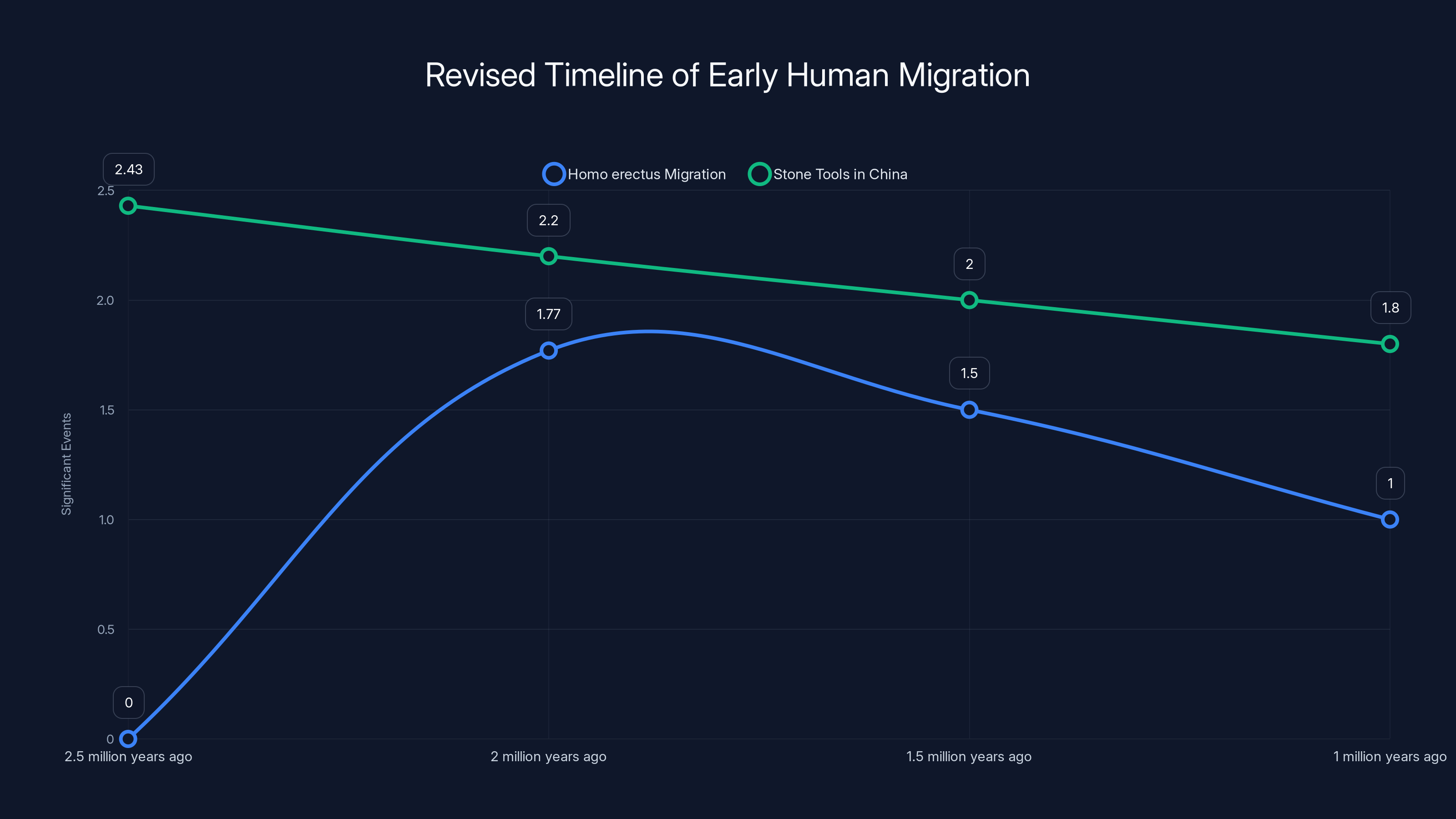

But there's more. These fossils also help explain something that's been puzzling researchers for years: the presence of stone tools in China that appear to be even older than Homo erectus itself. If hominins were making sophisticated stone tools 2.43 million years ago in China, who was actually responsible? The answer might not be Homo erectus at all, but rather earlier members of our genus who deserve far more credit for humanity's first great adventure beyond Africa.

TL; DR

- Yunxian skulls are 1.77 million years old, not the previously thought 1 million, making them the oldest Homo erectus fossils in East Asia

- Homo erectus spread incredibly fast, reaching both Georgia and China roughly simultaneously, suggesting a migration speed much faster than previously estimated

- These skulls aren't Denisovans, contradicting a 2025 study that claimed to identify close ancestors of this mysterious human species

- Earlier stone tools in China suggest other hominins left Africa first, with tools at Xihoudu dated to 2.43 million years ago, before Homo erectus even emerged

- This discovery rewrites our timeline of human expansion, forcing us to reconsider which species were the true pioneers of human migration

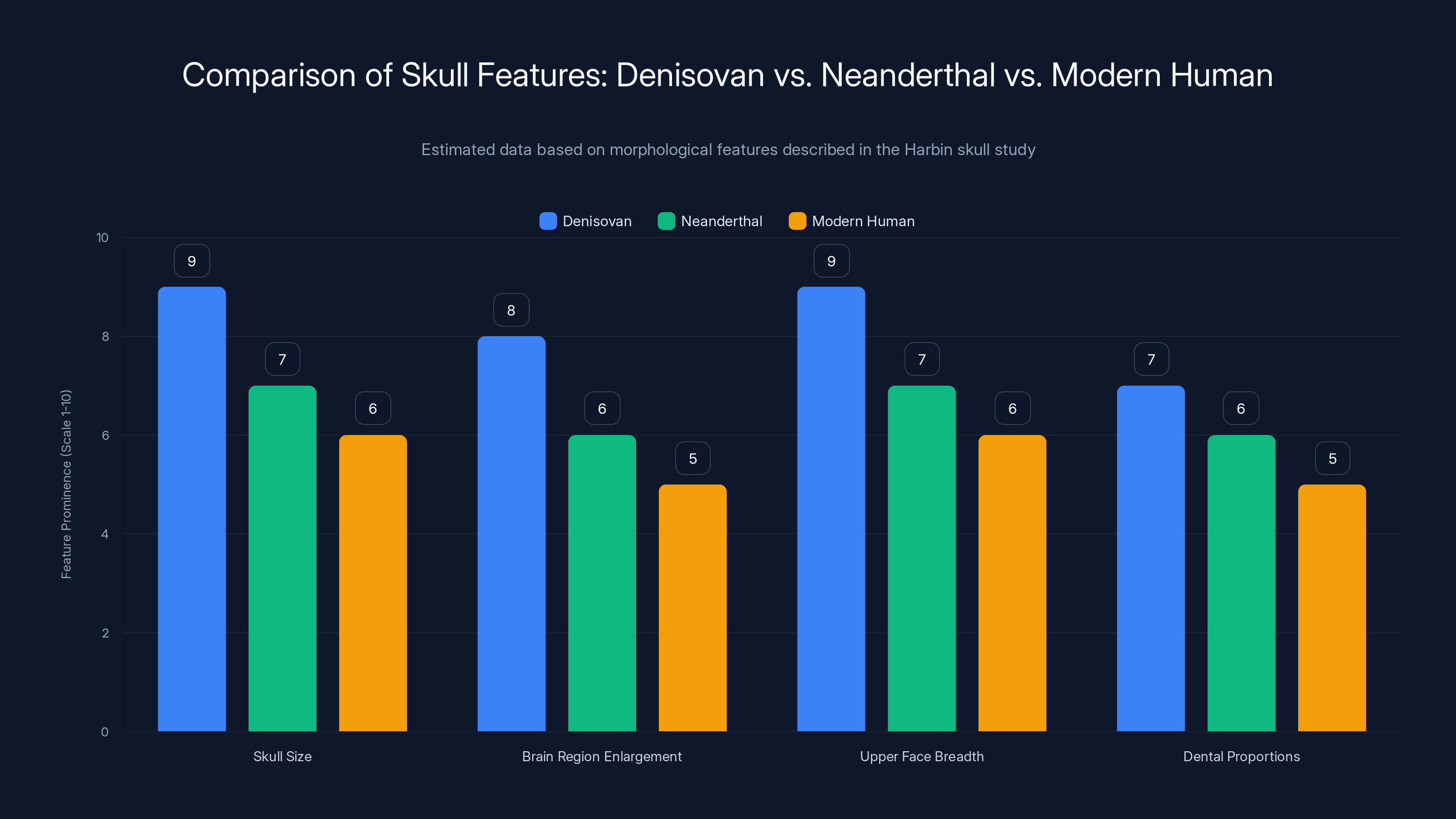

The Harbin Denisovan skull exhibits distinct features, such as larger skull size and broader upper face, compared to Neanderthals and modern humans. Estimated data based on morphological descriptions.

The Yunxian Site: Where Ancient Secrets Rest Along the Han River

The Han River winds through central China like a thread stitching together millions of years of geological history. Along its banks, archaeologists have discovered one of the most important repositories of early human remains outside of Africa: the Yunxian site. This isn't a dramatic cave discovery or a famous rock shelter—it's a river terrace where ancient sediment layers have been slowly accumulating since long before our species even existed.

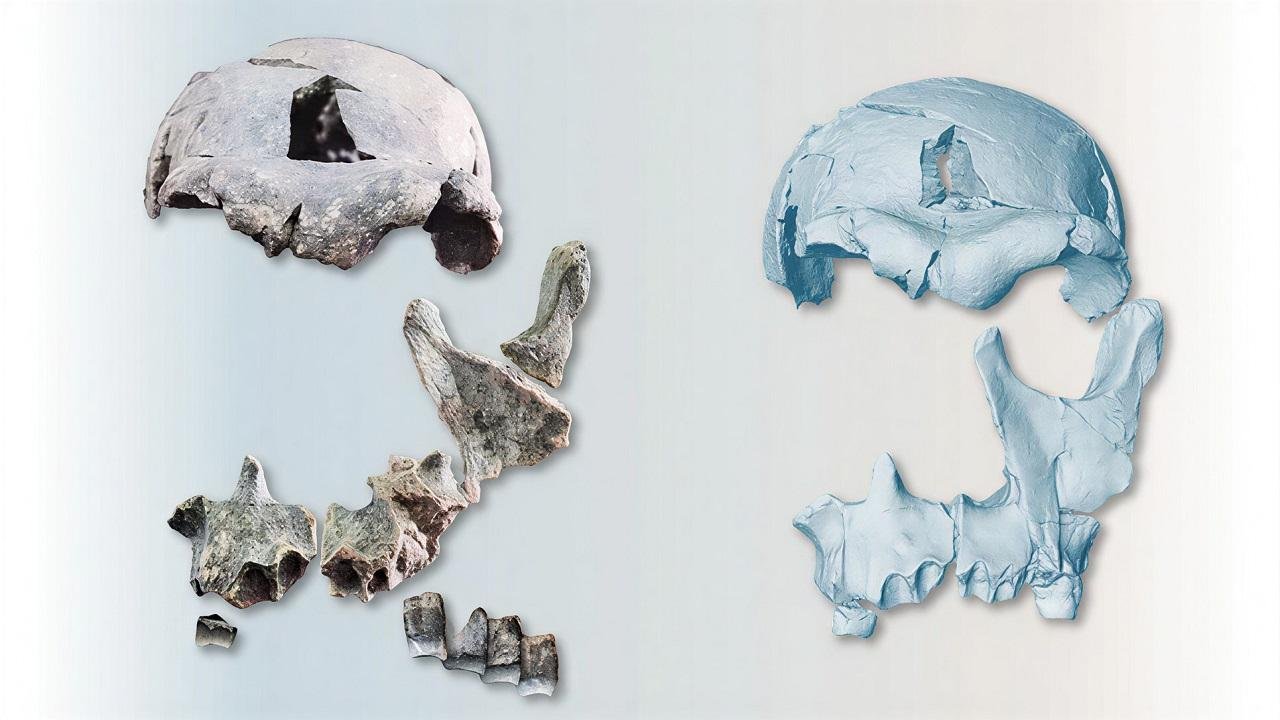

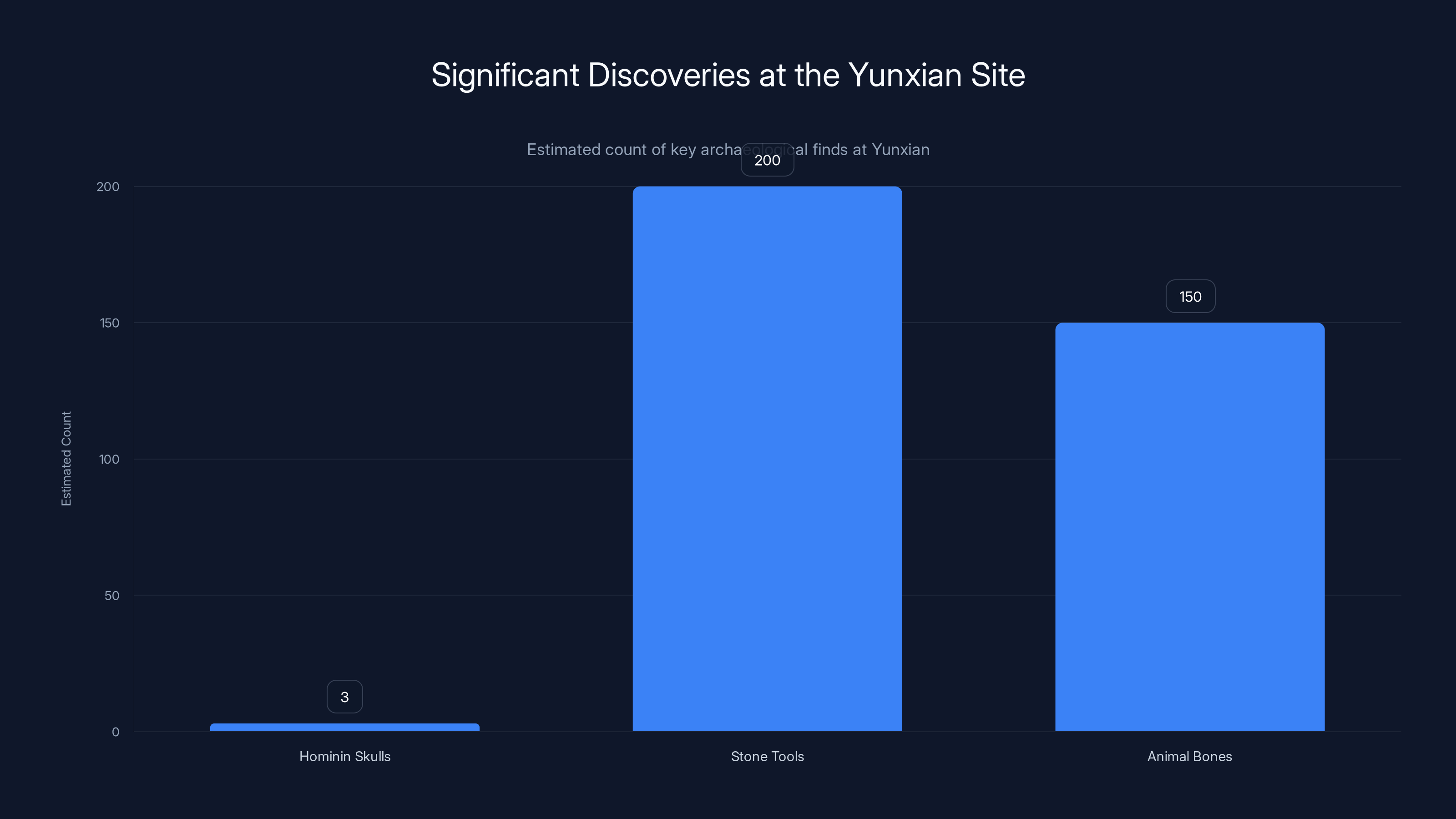

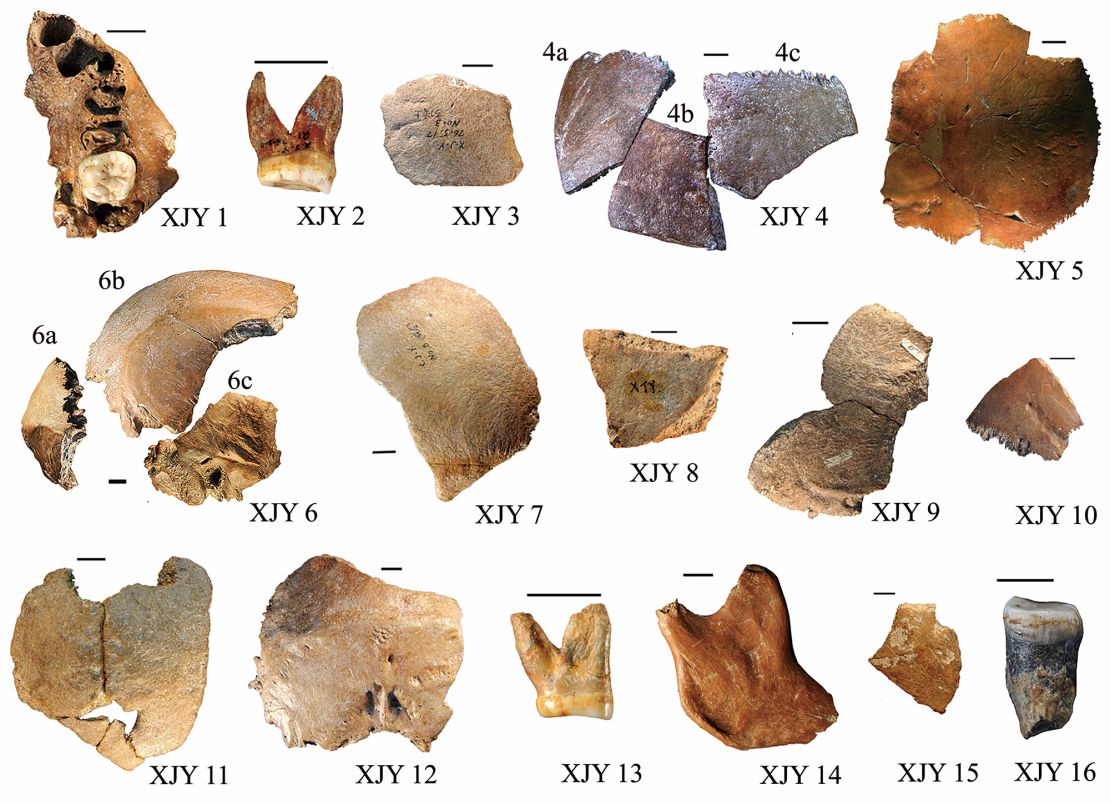

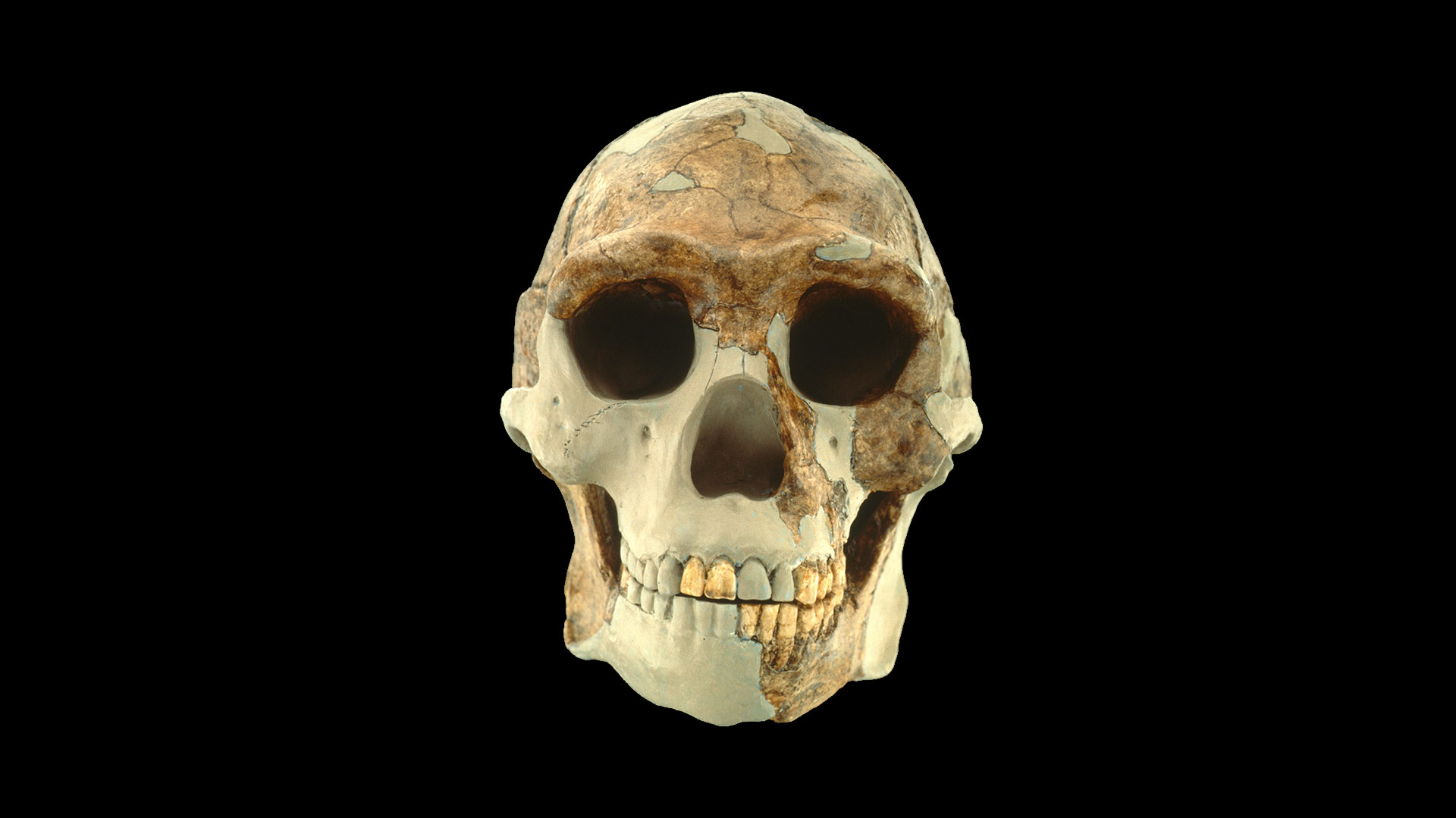

Yunxian first gained serious attention in the 1990s when Chinese archaeologists began excavating there and uncovered not one, not two, but three nearly complete hominin skulls. Complete skulls are extraordinarily rare in the fossil record. Most discoveries consist of scattered teeth, jaw fragments, or skull shards that require painstaking reconstruction. To find three relatively intact skulls from the same site was remarkable. Along with the skulls, researchers also recovered hundreds of stone tools and animal bones, painting a picture of a place where early humans lived, hunted, and died beside the river.

For decades, scientists assigned these skulls to Homo erectus based on their morphological characteristics. The skulls had features consistent with this species: a relatively small brain case, prominent brow ridges, and other anatomical markers that paleoanthropologists use to classify ancient hominin remains. But without precise dating, the exact age remained uncertain. Early estimates suggested they were roughly one million years old, maybe a bit older. That timeframe seemed to fit with what researchers knew about Homo erectus expansion into Asia.

Then in 2025, a research team led by paleoanthropologist Hua Tu from Shantou University decided to apply a more sophisticated dating technique. Instead of relying on traditional paleomagnetic dating methods alone, they used cosmogenic nuclide analysis. This technique measures the ratio of radioactive isotopes, specifically aluminum-26 and beryllium-10, that accumulate in quartz grains when they're exposed to cosmic rays at the Earth's surface.

The process is elegant in its logic. When sediment gets buried deeply underground, it's shielded from cosmic rays and these isotopes stop accumulating. By measuring how much aluminum-26 and beryllium-10 are present in quartz grains from the layer that contained the Yunxian skulls, scientists can calculate precisely how long ago those grains were exposed to the surface before being buried. The results were striking: the Yunxian skulls dated to approximately 1.77 million years ago.

That's not just older than previous estimates—that's fundamentally older. We're talking about a difference of roughly 230,000 years, which might not sound like much on a geological timescale but represents an enormous span in terms of human evolution and migration patterns. At 1.77 million years, the Yunxian skulls become the oldest known Homo erectus fossils in all of East Asia, pushing back our understanding of when this species made its first successful push into the Asian continent.

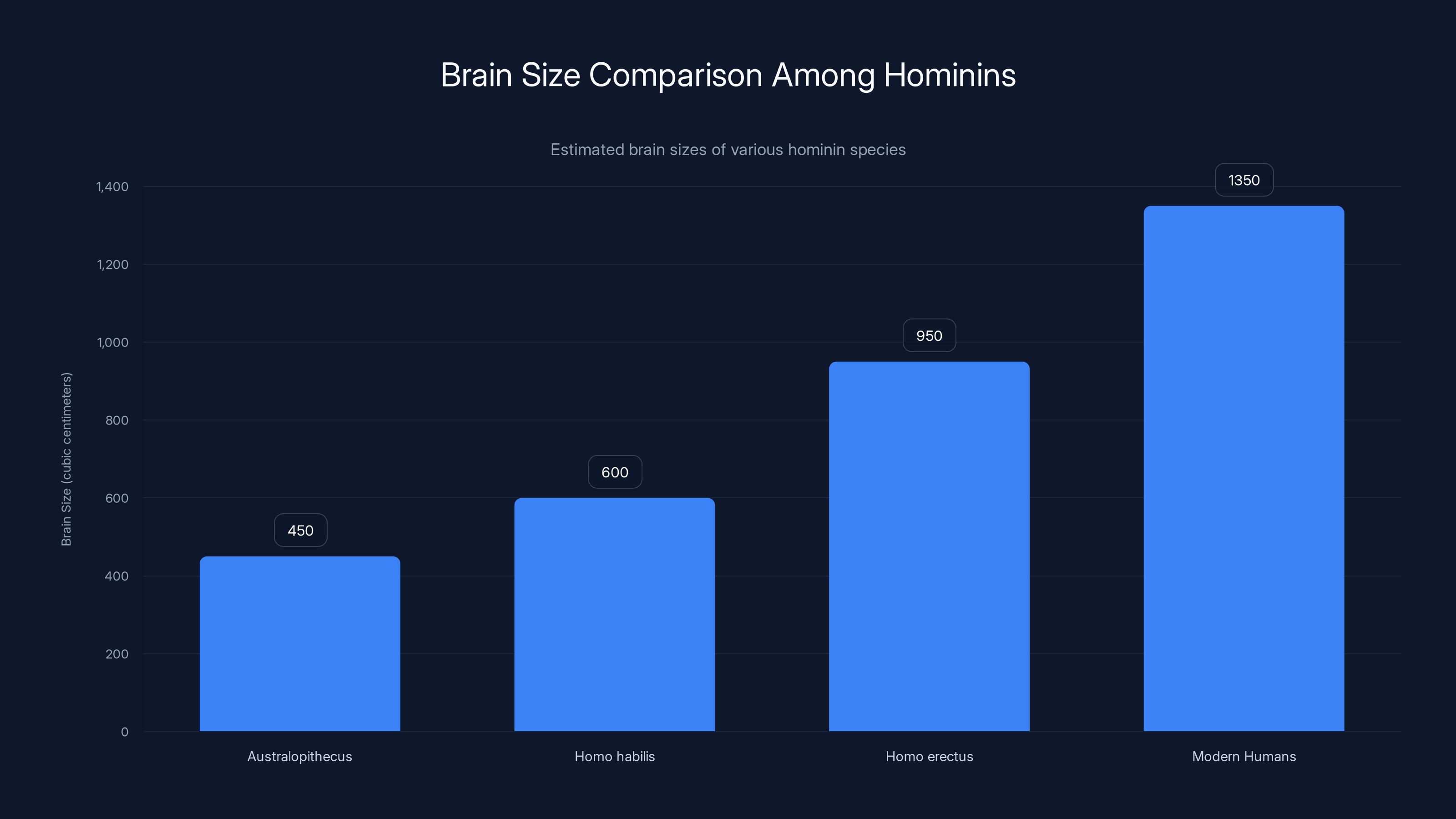

Homo erectus had a significantly larger brain size compared to earlier hominins, indicating more advanced cognitive capabilities. Estimated data.

The African Origin: Where It All Began

To understand why the Yunxian redating matters, we need to step back and look at the broader context of human evolution. Homo erectus first appears in the fossil record around 1.9 million years ago in Africa. This species represented a major breakthrough in hominin development. Unlike their predecessors, Homo erectus had a larger brain than earlier forms like Homo habilis or Australopithecus. This larger brain came with enhanced cognitive abilities, better planning skills, and improved problem-solving capabilities.

They also showed evidence of more sophisticated tool-making. While earlier hominins made simple stone tools by striking one rock against another to create sharp edges, Homo erectus invented the hand axe—a more refined implement that required multiple strikes to shape into a useful form. These weren't primitive creations but rather evidence of planning, forethought, and the ability to envision an end product before starting work.

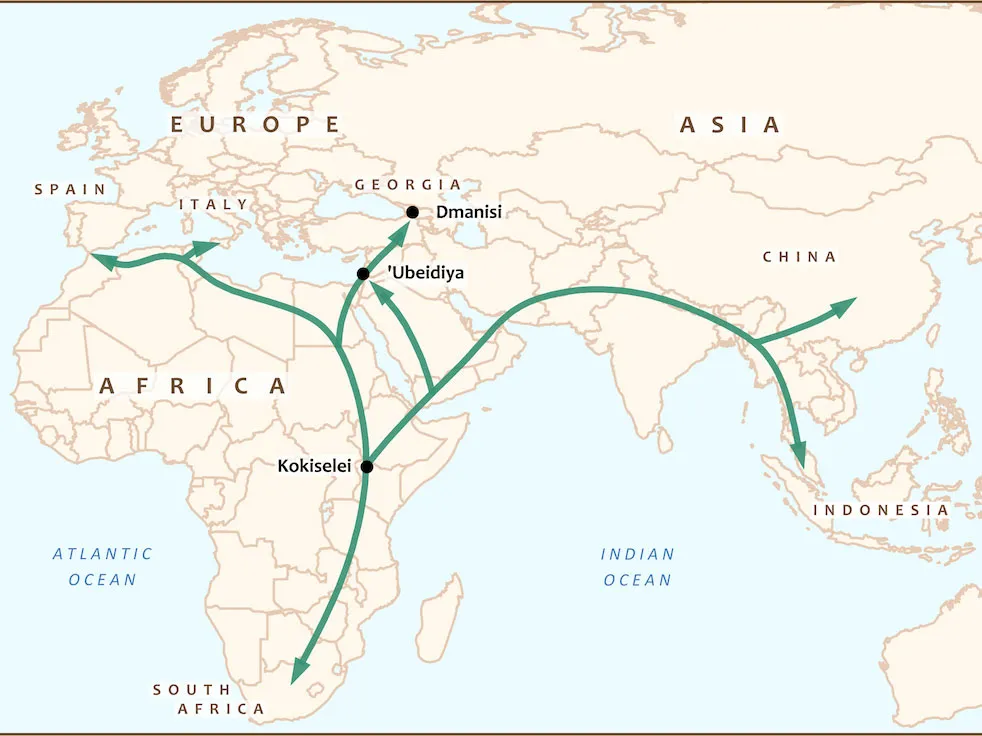

Perhaps most significantly for our story, Homo erectus appears to have been the first hominin to successfully establish populations beyond Africa. Archaeological and fossil evidence from across three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa—shows that within a few hundred thousand years of emerging, Homo erectus had spread to locations as diverse as the Caucasus region (Georgia), Indonesia, and now we know, central China.

The traditional view held that this expansion happened relatively slowly. Paleoanthropologists imagined populations gradually spreading outward, taking hundreds of thousands of years to reach distant lands. The distances involved are enormous. From Africa to Georgia is roughly 3,000 kilometers. From Africa to central China is approximately 6,000 kilometers. In an era before horses, boats, or any organized systems of trade and communication, these were massive distances.

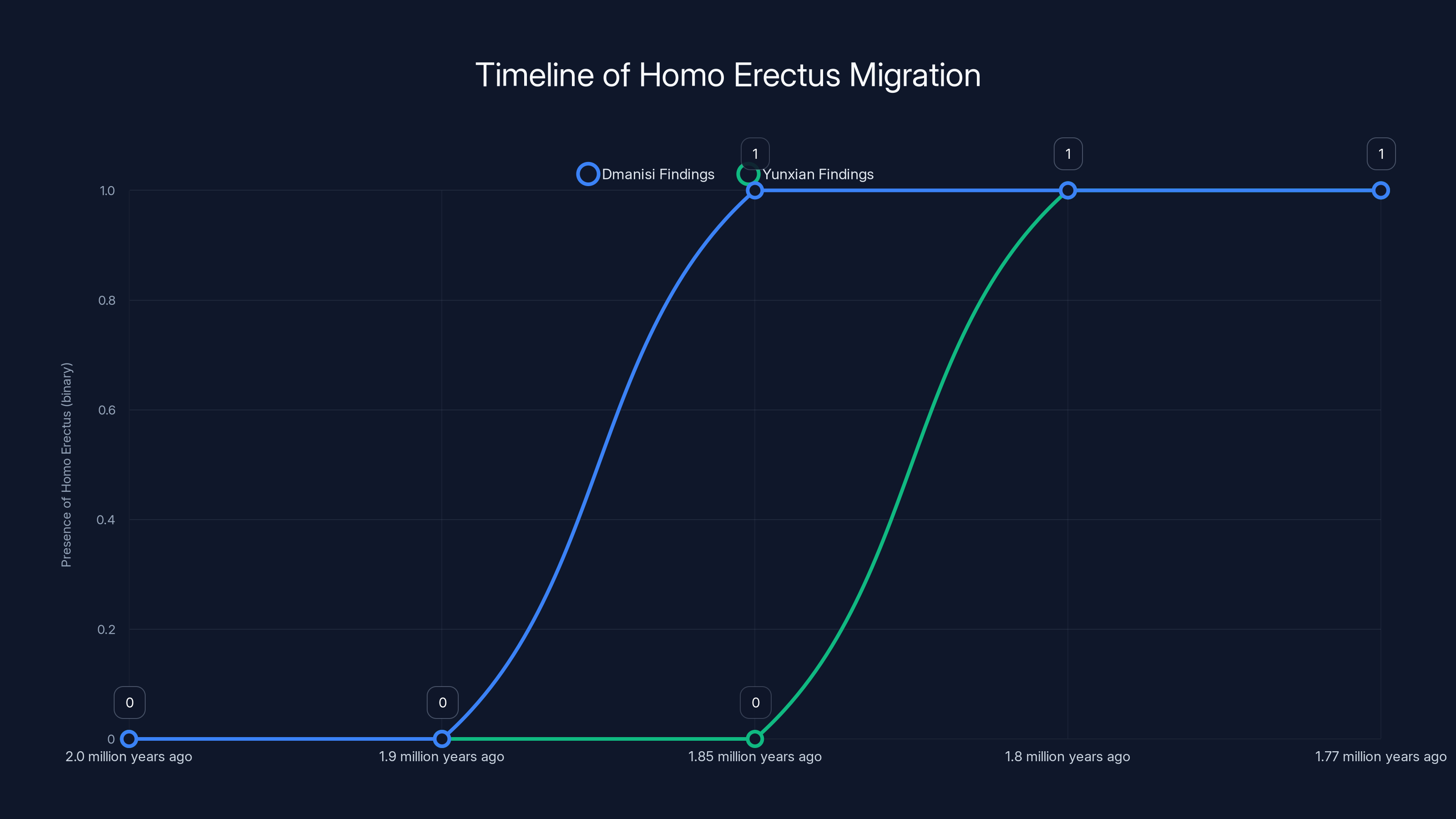

Yet the Yunxian redating suggests something different. If Homo erectus was living in Georgia (at Dmanisi Cave) 1.85 to 1.77 million years ago and simultaneously living in central China around 1.77 million years ago, then the species didn't creep slowly across Asia over centuries. Instead, it spread rapidly across an enormous geographic range in just a few hundred thousand years—a timespan that seems shockingly brief for such vast distances.

Dmanisi: The Other End of the Expanding Range

Before the Yunxian redating, the most important evidence for early Homo erectus outside Africa came from Dmanisi Cave in Georgia. This site, located in the Caucasus region where Europe and Asia meet, has yielded five skulls along with hundreds of other bone fragments. These remains are dated to between 1.85 and 1.77 million years ago, making them roughly contemporary with the newly re-dated Yunxian skulls.

Dmanisi was long considered the gateway to Asia—the place where early humans first ventured out of Africa and into the Eurasian landmass. The cave's location makes sense for such a journey. It sits on a natural migration corridor between Africa and Asia, a place where any population attempting to leave Africa would almost certainly pass through or nearby. The presence of five skulls suggested a established population, not just passing travelers. Homo erectus didn't just briefly visit Georgia; these individuals lived there, died there, and left their remains to be discovered millions of years later.

The Dmanisi remains are morphologically distinct from earlier African Homo erectus in some ways. Some researchers have debated whether they represent a distinct species or subspecies, sometimes calling them Homo ergaster or referring to them in Latin as Homo erectus georgicus. But the fundamental identity as Homo erectus seems well-established. What Dmanisi demonstrates is that by 1.85 million years ago, Homo erectus had successfully colonized the Caucasus region and established a viable population there.

The fact that Yunxian skulls are dated to approximately the same time period creates an intriguing puzzle. How did Homo erectus manage to spread so far, so fast? What routes did they take? Did they move along the coast, following marine resources? Did they travel through river valleys, using water sources for drinking and attracting prey animals? Did they move steadily over decades and centuries, or did some population experience a rapid expansion phase?

These questions remain largely unanswered, but the simultaneous presence of Homo erectus in Georgia and central China forces us to acknowledge that the species possessed remarkable adaptive capabilities. They could survive in diverse environments, from the cooler regions of the Caucasus to the temperate zones of central China. They could navigate unfamiliar landscapes, find food and water sources, and establish breeding populations sustainable enough to leave fossils millions of years later.

The Yunxian site has yielded three nearly complete hominin skulls, along with hundreds of stone tools and animal bones, providing valuable insights into early human life. Estimated data.

The Denisovan Question: A Hypothesis Challenged

In September 2025, just months before the Yunxian redating was published, another research team published a provocative paper claiming that the Yunxian skulls weren't simply Homo erectus. Instead, they argued these specimens represented early members of the Denisovan lineage—an extinct human species that is known primarily from DNA evidence rather than fossils. Denisovans represent one of the great mysteries in human evolution.

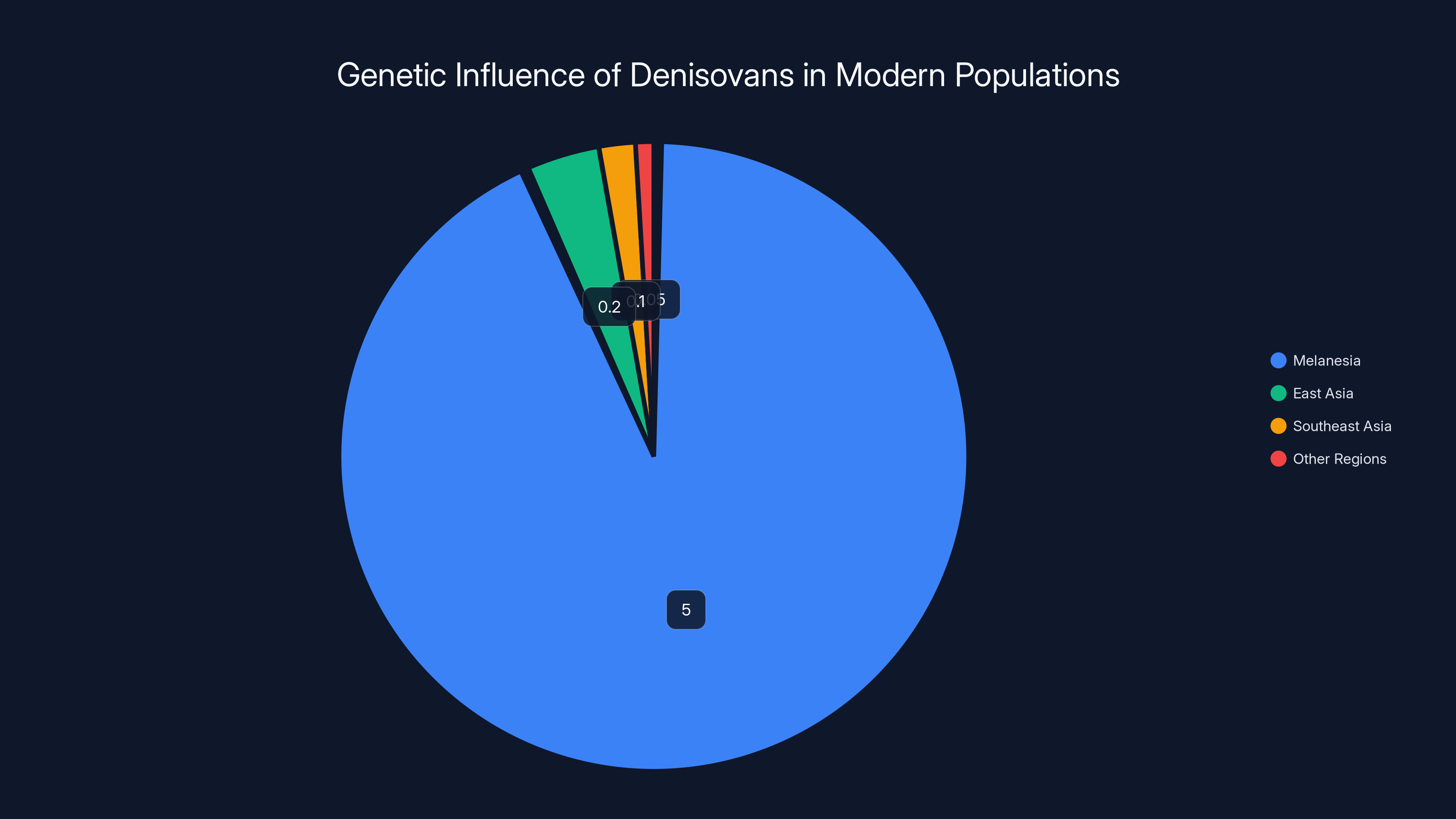

We know about Denisovans almost entirely from genetic material, particularly from a finger bone discovered in Denisova Cave in Russia and teeth from other sites in Asia. DNA analysis reveals that Denisovans were a distinct human species, sharing a common ancestor with both modern humans and Neanderthals, but diverging into their own evolutionary branch. Denisovans interbred with modern humans, particularly with populations in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Some living humans, particularly in Melanesia and parts of East Asia, carry segments of Denisovan DNA in their genomes.

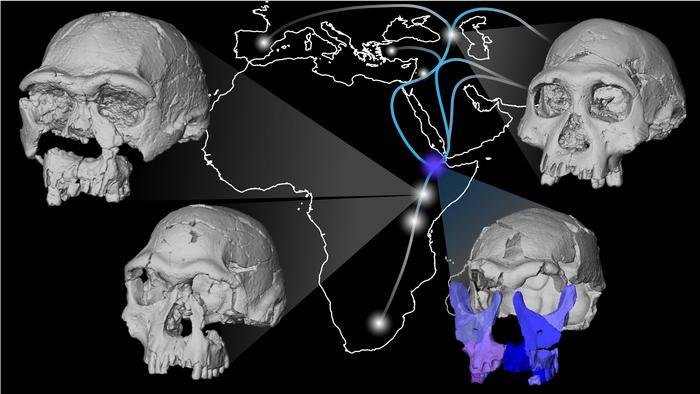

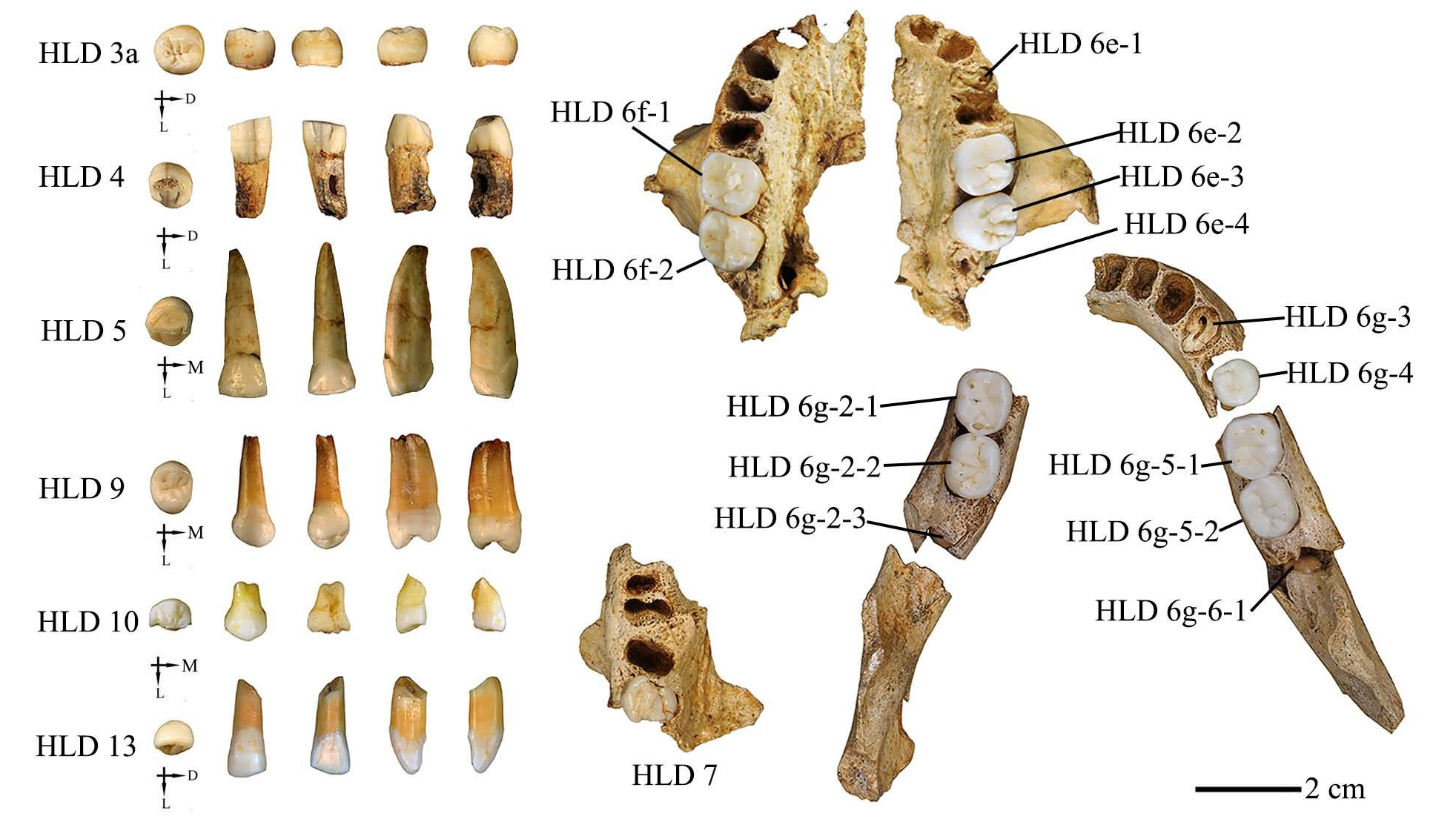

The most complete Denisovan remains we have come from the Harbin site in China, where a 146,000-year-old skull was discovered. DNA analysis definitively identified this skull as belonging to a Denisovan, and researchers gave this specimen and the species it represents the scientific name Homo longi. For years, researchers wondered about the deeper history of Denisovans. Where did this species come from? What did earlier members of the Denisovan lineage look like? How far back does the Denisovan evolutionary history extend?

The September 2025 study proposed a bold answer: the Yunxian skulls might represent early Denisovans or close ancestors on the path to becoming Denisovans. Researchers digitally reconstructed one of the Yunxian skulls and compared its morphology to the Harbin Denisovan skull. They claimed to find similarities suggesting an evolutionary connection. If true, this would push the origins of the Denisovan lineage back nearly 1.6 million years before the Harbin specimen, suggesting a much deeper evolutionary history for this mysterious species.

Moreover, the September study proposed a revised human family tree. Genetic evidence from modern humans indicates that Denisovans and modern humans shared a more recent common ancestor with each other than either shared with Neanderthals. But the September study suggested that the fossil evidence from Yunxian, if interpreted as early Denisovans, would push the split between the Denisovan and modern human lineages much earlier than DNA evidence indicates. This created a contradiction between the fossil record and genetic evidence.

The Yunxian redating essentially destroys this hypothesis. At 1.77 million years old, the Yunxian skulls existed far too far back in time to represent early Denisovans or ancestors on the Denisovan evolutionary path. DNA evidence clearly shows that Denisovans as a distinct species didn't emerge until roughly 700,000 years ago. That's more than a million years after the Yunxian individuals lived and died.

As paleoanthropologist John Hawks from the University of Wisconsin noted, the new dates make any evolutionary connection between Yunxian and Denisovans implausible. The temporal gap is simply too great. You can't have ancestors living more than a million years before their proposed descendants. The September 2025 study, while scientifically interesting as an attempt to synthesize fossil and genetic data, appears to have relied on outdated age estimates for the Yunxian skulls. With the corrected dates, the entire theoretical framework collapses.

Homo erectus Adaptive Success: Masters of Multiple Environments

What the Yunxian and Dmanisi fossils really tell us is that Homo erectus was remarkably successful at adapting to different environments. This species didn't just survive in Africa where it evolved—it thrived in dramatically different climates and ecosystems across multiple continents.

Central China in the early Pleistocene, when the Yunxian population lived there, presented a temperate climate but with distinct seasons. The Han River would have provided water year-round, attracting prey animals that Homo erectus hunted and butchered. The surrounding landscape offered stone suitable for tool-making, trees for shelter and firewood, and plant foods to supplement a diet rich in meat and fish.

Georgia's climate was somewhat cooler, with mountainous terrain and different vegetation. Yet Homo erectus managed to establish a population there as well. The ability to survive and reproduce in both of these environments suggests cognitive flexibility, problem-solving skills, and the capacity to invent new solutions to new challenges.

Perhaps most remarkably, Homo erectus also dispersed as far as Java in what is now Indonesia, reaching tropical environments dramatically different from Africa. The oldest evidence of human presence in Indonesia comes from sites dated to around 1.8 million years ago, contemporaneous with Yunxian. Homo erectus in Java would have faced completely different flora and fauna, new diseases and parasites, different food sources, and a tropical climate unlike anything in Africa.

This wide geographic spread indicates that Homo erectus possessed several crucial adaptations. They likely had sophisticated social structures that allowed for information sharing and cooperative problem-solving. They created and used sophisticated tools not just for hunting but for processing food, creating shelter, and potentially for creating other tools. They had some capacity for language or communication beyond simple alarm calls, allowing them to teach younger generations the skills needed to survive in new environments.

Their larger brains compared to earlier hominins seem to have conferred genuine advantages. With more neural tissue, Homo erectus could store more information, process more complex problems, and potentially envision solutions before implementing them. Over many generations, these cognitive advantages would have accumulated, allowing populations to increasingly modify their behavior and technology to suit local conditions.

The discovery of the Yunxian skulls and earlier stone tools suggests a much earlier timeline for human migration into East Asia, challenging previous assumptions. Estimated data.

The Mystery of Earlier Stone Tools: Who Were the Real Pioneers?

Even more intriguing than the Yunxian skulls are certain stone tools found at other Chinese sites. These tools appear to be older than Homo erectus itself, suggesting that an earlier human ancestor made it out of Africa before Homo erectus even evolved.

At a site called Shangchen on the southern edge of China's Loess Plateau, archaeologists excavated stone tools from a layer dated to 2.1 million years ago. That's 330,000 years before the Yunxian skulls. At another site, Xihoudu in northern China, stone tools were dated to 2.43 million years ago. That's 660,000 years before Homo erectus even appears in the fossil record.

This creates a substantial chronological problem. If stone tools were being made in China at 2.43 million years ago, and Homo erectus didn't emerge in Africa until 1.9 million years ago, then either our timeline of Homo erectus evolution needs to be pushed back, or some other hominin species must have been responsible for these tools.

The leading candidate for these earlier stone tool makers is Homo habilis, sometimes called the handy man because it's primarily known from its association with stone tools. Homo habilis is an earlier member of our genus than Homo erectus, with smaller brains and less sophisticated bodies. For many years, researchers considered Homo habilis to be essentially an African species. But the evidence from Shangchen and Xihoudu suggests that at least some populations of Homo habilis or a closely related species managed to leave Africa and establish themselves in Asia earlier than Homo erectus.

This would represent a second wave of hominin expansion out of Africa, predating Homo erectus by hundreds of thousands of years. It would mean that the first humans to reach Asia weren't Homo erectus but earlier, presumably less advanced members of our genus. These pioneers would have been smaller-brained, less sophisticated in their tool-making, and yet somehow successful enough to establish populations far from Africa.

Alternatively, some researchers have speculated that these very old stone tools might have been made by Homo ergaster, sometimes considered a distinct species from Homo erectus, or by populations that weren't fully Homo erectus by some criteria but were evolving in that direction. The fossil record is too sparse at these early time periods to definitively identify who the toolmakers were.

The implications are profound. If multiple waves of hominin dispersal occurred, with different species or populations leaving Africa at different times, then the history of human expansion is more complex than we've traditionally thought. Homo erectus wasn't the first human to leave Africa—it was the most successful, establishing populations across three continents and persisting for more than a million years. But it was preceded by earlier, less accomplished hominin species who nonetheless managed to make the leap from an African birthplace to distant continents.

Timeline of Human Dispersal: A Revised Understanding

The Yunxian redating, combined with the evidence of earlier stone tools, forces us to construct a new timeline of human dispersal from Africa. This timeline is more complex and compressed than previous models suggested.

Around 2.43 to 2.1 million years ago, early members of the genus Homo—possibly Homo habilis or a closely related species—were making stone tools in China. These individuals had somehow left Africa and reached Asia, establishing populations capable of leaving archaeological evidence. We know almost nothing about who these pioneers were, how they got there, or what happened to their descendants.

Around 1.9 million years ago, Homo erectus emerges in Africa. Within a few hundred thousand years, this species begins dispersing beyond Africa. The timing is remarkably rapid. Homo erectus is in Georgia by 1.85 million years ago and in central China by 1.77 million years ago. It also appears in Indonesia around the same time period.

For the next million years, Homo erectus persists across its wide geographic range, evolving locally in different regions and producing regional variants. Some populations in Java appear to have persisted until much more recently than others, with some evidence suggesting survival until 400,000 years ago or later.

However, this timeline contains gaps and uncertainties. We don't know the precise routes of expansion. We don't know whether Homo erectus dispersal was a single event or multiple episodes. We don't know what happened to the earlier toolmakers in China—did they disappear when Homo erectus arrived, or did they persist? Did some populations interbreed with incoming Homo erectus migrants?

The fossil record is too incomplete to answer these questions definitively. But the Yunxian redating and our growing understanding of stone tools at other Asian sites force us to acknowledge that human dispersal from Africa was a more complex process than previously appreciated. Multiple hominin species were on the move at different times. The timeline was compressed, with multiple dispersal events occurring within a few hundred thousand years. And the success of Homo erectus, spectacular as it was, built on earlier pioneering efforts by other members of our genus.

The timeline shows that Homo erectus was present in both Dmanisi and Yunxian around 1.85 to 1.77 million years ago, indicating a rapid migration across vast distances. Estimated data based on archaeological findings.

Stone Tools and Hunting: Evidence of Sophisticated Behavior

The presence of hundreds of stone tools at Yunxian provides crucial context for understanding how Homo erectus actually lived. These weren't crude, random rocks struck together to produce a sharp edge. They were shaped implements, produced through deliberate strikes designed to create cutting edges suitable for different purposes.

Archaeologists have identified different tool types at Yunxian, including scrapers for processing hide and other materials, sharp flakes for butchering animal carcasses, and heavier tools likely used for breaking bones to access marrow. The variety suggests a toolkit adapted to multiple tasks. Homo erectus at Yunxian wasn't simply making random tools—they were manufacturing specific implements for specific purposes.

The stone tools often bear marks of use—tiny scratches and wear patterns that reveal what they were used for. Some flakes have striations consistent with cutting meat. Others show patterns indicating use on vegetation or wood. This use-wear analysis tells us that these tools were actively deployed in the daily tasks of survival and subsistence.

Alongside the tools, archaeologists recovered animal bones bearing cut marks from stone tools and signs of having been broken open to access the marrow inside. These bones represent dinner—the remains of animals killed and butchered by Homo erectus at the Han River. The species was an effective hunter or at least an effective scavenger with the tools and knowledge to butcher large animal carcasses.

The presence of both stone tools and butchered animal bones at a site where three human skulls were also found provides a rare window into the daily life of Homo erectus. These individuals lived by the river, made tools from available stone, hunted or scavenged animals, and shared this landscape with others of their kind.

Paleomagnetic Dating: The Original Method and Its Limitations

To fully appreciate why the Yunxian redating matters, we need to understand how the original age estimates were made and why they might have been inaccurate. The original dating of the Yunxian skulls relied primarily on paleomagnetic analysis.

Paleomagnetic dating is based on the fact that Earth's magnetic field reverses periodically. When sediments are deposited, magnetic minerals in those sediments align with the Earth's magnetic field at the time of deposition. As the sediments are buried and compacted into rock, this magnetic alignment becomes locked in place. By measuring the orientation and strength of magnetization in different layers of rock, scientists can determine whether the layers were deposited during times when the magnetic field was oriented the same way it is today (normal polarity) or reversed (reversed polarity).

Paleontologists have created a detailed magnetic timescale by examining sediments of known age and determining their magnetic properties. By identifying which polarity zones are present in a sediment sequence, scientists can assign approximate ages to those sequences. However, paleomagnetic dating has limitations. The reversal pattern is not unique—the same sequence of reversals can appear at different times in Earth's history. Without other dating methods to anchor the sequence, paleomagnetic dating can sometimes be ambiguous.

For the Yunxian skulls, paleomagnetic analysis suggested an age around 1 million years, placing them within a particular polarity zone. But determining the exact age within that zone was difficult. The margin of error was substantial, potentially spanning hundreds of thousands of years.

Cosmogenic nuclide analysis, the technique used in the 2025 redating, provides a more precise absolute age. By measuring the accumulation of radioactive isotopes in quartz grains, researchers can calculate a specific age with a smaller margin of error. The 1.77 million-year age for Yunxian has an uncertainty of roughly plus or minus 80,000 years, still substantial in human timescales but much more precise than the previous paleomagnetic estimates.

The redating highlights an important principle in science: older techniques can provide useful information, but newer methods often improve precision and accuracy. The paleomagnetic dating wasn't wrong exactly—it was just less precise than we realized. The true age fell within the possible range suggested by paleomagnetic data, but only at the older end of that range.

Melanesian populations have the highest Denisovan DNA, with about 5% of their genome, while East Asian and Southeast Asian populations have significantly lower percentages. Estimated data based on genetic studies.

The Harbin Denisovan Skull: Context and Comparison

To understand why researchers initially made a connection between Yunxian and Denisovans, we need to understand the Harbin skull discovery and what it told us about Denisovans.

The Harbin skull was discovered in northeastern China and is dated to about 146,000 years ago. For many decades, it sat in a museum collection, not receiving much scientific attention because it lacked the right context—no clear archaeological layer, no associated stone tools or animal bones. In 2021, researchers finally formally studied the skull using modern technology and conducted DNA analysis. The results were startling: the skull contained well-preserved DNA, and that DNA clearly identified it as belonging to a Denisovan.

This was the first time researchers had found extensive Denisovan remains beyond the finger bone and teeth from Denisova Cave in Russia. The Harbin skull gave scientists their first opportunity to examine the morphology of a Denisovan face and brain case. Comparisons with modern skulls and those of other human species revealed that Denisovans had features that were distinctly their own. The skull was larger than Neanderthals' or modern humans', with particular enlargement in certain brain regions. The face had a different shape, with a broader upper face and different proportions in the dental region.

When researchers examined the Yunxian skulls, they noticed some features that seemed vaguely similar to the Harbin Denisovan skull. This led to the hypothesis that maybe the Yunxian specimens represented an ancestral population for Denisovans. But the hypothesis assumed the Yunxian skulls were around one million years old. At that age, they could plausibly have been ancestors or close relatives of a lineage that led to Denisovans. With the redating to 1.77 million years, the temporal gap becomes impossible to bridge. No evolutionary lineage could plausibly persist unchanged for over a million years while leaving no intermediate fossils.

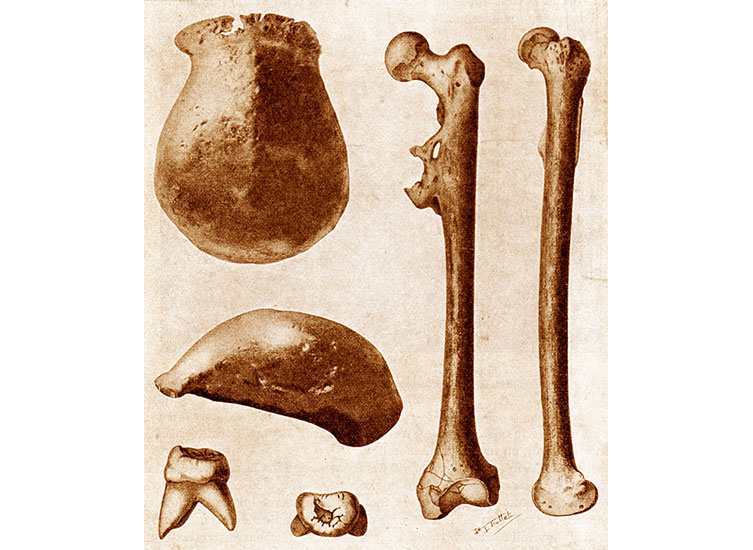

Gongwangling: The Previous Record Holder

Before Yunxian was redated, the oldest known Homo erectus fossil from East Asia came from another Chinese site: Gongwangling, located not far north of Yunxian. The Gongwangling remains are dated to approximately 1.63 million years ago, making them 140,000 years younger than the newly dated Yunxian skulls.

Gongwangling is significant in its own right because it demonstrates that Homo erectus had a sustained presence in central China well before the more famous sites further east. The site produced not only hominin remains but also associated stone tools and animal bones, indicating that Homo erectus had become established in the region.

With Yunxian now established as older than Gongwangling, the picture of Homo erectus in central China becomes clearer. The species arrived and established populations by about 1.77 million years ago, as evidenced at Yunxian. By 1.63 million years ago, as shown at Gongwangling, the species was still present and thriving in the same general region. This suggests that once Homo erectus arrived in central China, it successfully established permanent populations that persisted for hundreds of thousands of years.

The persistence of Homo erectus in this region for such a long time period indicates genuine success. These weren't transient visitors passing through; they were established populations that reproduced, developed local adaptations, and became truly established in their new homeland. Over many generations, different populations might have diverged from each other, developing regional characteristics. The fossil record is too sparse for us to see this divergence clearly, but it's reasonable to assume that Homo erectus populations in China evolved separately from populations in Indonesia or the Caucasus.

Cognitive Abilities: What a Larger Brain Means

One of the distinguishing features of Homo erectus compared to earlier hominins is a substantially larger brain. While Australopithecus had brains only slightly larger than modern chimpanzees, and Homo habilis had brains somewhat larger still, Homo erectus achieved brain sizes approaching 900 to 1,000 cubic centimeters, approaching the size of modern human brains.

Why does brain size matter? Larger brains allow for more complex neural architecture. More neurons and more connections between neurons enable more sophisticated information processing. A larger brain can hold more memories, make more complex associations, and solve more complex problems.

However, brain size alone doesn't tell the whole story about intelligence or capability. The organization of the brain, the connections between regions, and the specific types of cells present all contribute to cognitive ability. We can't perfectly reconstruct Homo erectus cognitive abilities just from examining the external morphology of skulls, but we can infer certain capabilities from their behavior.

The stone tools made by Homo erectus suggest planning and forethought. Creating a hand axe requires multiple strikes, each one positioned to achieve a specific result relative to previous strikes. The toolmaker must visualize the final product and understand how each strike moves the object closer to that goal. This type of sequential planning requires more cognitive sophistication than simply striking rocks together randomly.

The successful colonization of multiple continents and diverse environments suggests problem-solving abilities and flexibility. Homo erectus was capable of adapting to new situations, finding resources in unfamiliar places, and innovating new solutions to new challenges. These capabilities require intelligence.

The apparent structure of Homo erectus societies, inferred from spatial distributions of tools and bones at archaeological sites, suggests some level of social organization and cooperation. If Homo erectus hunted large animals, which evidence suggests they did, they would have needed to coordinate with others, plan strategies, and communicate effectively. These abilities require sophisticated cognition.

So while we can't measure Homo erectus IQ or determine exactly how they thought, the archaeological evidence suggests they were considerably more intelligent than earlier hominins and capable of genuinely impressive adaptive behaviors.

Environmental Context: The Pleistocene Landscape

To understand what it meant for Homo erectus to successfully colonize China and Georgia, we need to picture the environment they encountered. The world 1.77 million years ago was different from today's world, though perhaps not as dramatically different as the world of much earlier periods.

During the early Pleistocene, Earth was in the midst of a long-term cooling trend that had begun millions of years earlier. Ice ages came and went with varying intensity. When the Yunxian population lived along the Han River, the climate would have been temperate but with distinct seasonal variation. Winter temperatures probably dropped below freezing regularly, while summers were warm enough for growth and reproduction.

Vegetation in central China would have been a mix of forest and grassland. The Han River would have been a reliable source of water and would have attracted animals seeking to drink. Fish populations in the river would have provided food sources. Prey animals like deer, wild boar, and possibly larger animals would have congregated near water sources.

This environment presented challenges that required Homo erectus to adapt. The species would have needed shelter from winter cold. Fire would have been useful for warmth and for cooking food, though we don't have clear evidence that Homo erectus controlled fire, particularly at the 1.77-million-year-old Yunxian. The species would have needed to hunt or effectively scavenge large animals to gain access to sufficient protein. Tool-making would have been crucial for butchering carcasses and processing other foods.

Georgia's environment would have been somewhat colder and more mountainous, presenting different challenges. But Homo erectus managed there too, establishing populations and leaving a fossil record of its presence.

The success of Homo erectus across multiple environments suggests the species possessed genuine behavioral flexibility. Different populations likely developed local adaptations to local conditions. Central Asian populations might have focused on different prey species than Indonesian populations. Tools might have been manufactured slightly differently, with local populations developing their own traditions and techniques.

The Fossil Record Gap: What We Don't Know

For all the insights the Yunxian redating provides, it also highlights how much we don't know about early human evolution. The fossil record is incomplete. We have scattered sites, sometimes hundreds of thousands of years apart, and we're trying to infer continuous history from these fragmentary pieces.

We don't know the precise date of Homo erectus emergence in Africa because we don't have enough early fossils with sufficiently precise dating. We don't know whether Homo erectus dispersal out of Africa was a single event or multiple separate expansions. We don't know the exact routes taken or the pace of migration. We don't know what happened to earlier hominins like Homo habilis when Homo erectus arrived. Did they disappear entirely, or did some persist for a time?

The stone tools at Shangchen (2.1 million years) and Xihoudu (2.43 million years) represent anomalies we don't fully understand. Who made them? How did these toolmakers arrive in Asia? What happened to them? Without associated fossil remains, we can only speculate.

Future discoveries will certainly revise our understanding again. New fossils, better dating techniques, and improved methods for extracting and analyzing ancient DNA will continually refine our picture of early human evolution. The Yunxian redating is presented as a solid scientific conclusion, but it's important to remember that our understanding of these distant periods remains preliminary and subject to revision.

Implications for Understanding Modern Human Origins

Although the Yunxian redating doesn't directly address the origins of modern humans, it provides context for understanding the larger picture of human evolution. Modern humans emerged in Africa somewhere between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago. Our species didn't expand out of Africa until much more recently, probably between 70,000 and 100,000 years ago.

Yet for the 1.5 million years or more between Homo erectus's departure from Africa and modern humans' departure, Asia had already been inhabited by earlier human species. This continuous human presence across multiple continents set the stage for subsequent human migrations. When modern humans eventually left Africa, they were moving into lands that had already been explored and inhabited by other members of the human lineage.

Moreover, we now know that modern humans interbred with Denisovans and Neanderthals. These encounters occurred between 40,000 and 100,000 years ago in Asia and Europe. But those encounters were only possible because Denisovans and Neanderthals had evolved in Asia and Europe, having descended from earlier hominins like Homo erectus who had first colonized these regions.

In this sense, the success of Homo erectus in establishing populations across Asia set the stage for all subsequent human evolution in the Eastern Hemisphere. The descendants of those early Homo erectus populations eventually evolved into Neanderthals, Denisovans, and various other regional human species. When modern humans encountered these species, they were meeting distant cousins whose lineage traced back to those ancient Homo erectus populations that first left Africa.

Future Research Directions: What Scientists Still Want to Understand

The Yunxian redating answers some questions but raises others, pointing the way toward future research. Scientists will want to understand more precisely how Homo erectus managed such rapid geographic expansion. Did the species possess any capacity for language? How sophisticated were their hunting strategies? Did they use fire for cooking and warmth? Did they create other technologies we haven't yet recognized in the archaeological record?

The mystery of the earlier stone tools remains largely unresolved. Future discoveries in China and elsewhere in Asia might reveal fossils associated with the 2.43-million-year-old tools at Xihoudu, finally allowing scientists to identify who the early toolmakers were. New genetic analysis of the Yunxian skulls, if DNA can be extracted, might clarify their exact relationship to other Homo erectus populations and to later human species.

Improved dating techniques might provide more precise ages for other important hominin fossils, refining our timeline of human evolution. New fossil discoveries will inevitably occur as paleontologists continue to explore promising sites. Each new discovery has the potential to shift our understanding again, as the Yunxian redating has done.

Scientists are also interested in understanding the mechanisms of adaptation that allowed Homo erectus to succeed in new environments so rapidly. Did the species possess genetic adaptations to different climates? Did populations develop different dietary specializations in different regions? How quickly could Homo erectus learn new skills and adapt behavior to new environmental conditions?

These questions can be addressed through continued excavation, fossil study, sophisticated dating analysis, ancient DNA research where possible, and careful study of archaeological remains and stone tools. The Yunxian redating demonstrates how new techniques and renewed examination of old materials can yield surprising insights. Future research will undoubtedly provide more such insights, continually refining our understanding of early human history.

FAQ

What is Homo erectus and why does it matter for understanding human evolution?

Homo erectus is an extinct human species that lived from approximately 1.9 million to 100,000 years ago, making it one of the longest-lasting members of our genus. It matters crucially for human evolution because it was the first hominin species to successfully expand beyond Africa and establish populations across multiple continents, including Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Homo erectus represents an important evolutionary step in developing larger brains, sophisticated tools, and the behavioral flexibility needed for global dispersal.

How did scientists determine that the Yunxian skulls are 1.77 million years old?

Scientists used a technique called cosmogenic nuclide analysis, which measures the accumulation of radioactive isotopes (aluminum-26 and beryllium-10) in quartz grains from the sediment layer containing the skulls. These isotopes accumulate when rocks are exposed to cosmic rays at the Earth's surface, but stop accumulating once the rocks are buried deeply underground. By measuring the isotope ratios, researchers can calculate exactly when the rocks were buried, providing a precise age for the fossils.

Why doesn't the redating of Yunxian support the idea that these skulls are early Denisovans?

DNA evidence clearly shows that Denisovans as a distinct species didn't emerge until approximately 700,000 years ago. The Yunxian skulls, at 1.77 million years old, are more than a million years older than this date. This temporal gap is too large for the Yunxian specimens to be early Denisovans or direct ancestors of Denisovans, as there are no intermediate fossils connecting them across such a vast span of time.

What do the stone tools found at Yunxian reveal about Homo erectus behavior?

The hundreds of stone tools at Yunxian show that Homo erectus engaged in sophisticated tool-making and had a specialized toolkit adapted for multiple purposes. Different tool types were used for scraping, cutting meat, and breaking bone. Use-wear analysis reveals these tools were actively deployed in daily tasks including hunting and food processing. This evidence indicates that Homo erectus had planning abilities, understood cause and effect in tool creation, and could solve practical problems through technological innovation.

What are the Xihoudu and Shangchen stone tools, and why are they significant?

Xihoudu and Shangchen are archaeological sites in China where stone tools were discovered in layers dated to 2.43 and 2.1 million years ago respectively. These dates are older than the emergence of Homo erectus 1.9 million years ago, suggesting that some earlier hominin species, possibly Homo habilis or a related form, left Africa before Homo erectus did. This raises questions about whether human dispersal from Africa involved multiple waves of expansion by different species rather than a single major movement.

How does the Yunxian redating change our understanding of Homo erectus migration patterns?

The new dating shows that Homo erectus reached central China (Yunxian, 1.77 million years ago) and the Caucasus region (Dmanisi, 1.85-1.77 million years ago) nearly simultaneously, within roughly 130,000 years of the species' emergence in Africa. This dramatically compresses the timeline of human expansion and suggests Homo erectus spread much faster across vast distances than previously thought, indicating remarkable adaptive capabilities and possibly more sophisticated behaviors than earlier estimates suggested.

What environmental conditions did Homo erectus encounter in central China at the Yunxian site?

The Yunxian region 1.77 million years ago featured a temperate climate with distinct seasons, a reliable river (the Han River) that attracted animals for drinking, mixed forest and grassland vegetation, and diverse prey species including deer and wild boar. These environmental conditions would have required Homo erectus to develop shelter strategies, hunting and scavenging techniques, and food processing methods, all supported by the sophisticated stone tool kit they left behind.

How does the Harbin Denisovan skull relate to the Yunxian remains?

The Harbin skull, dated to 146,000 years ago and confirmed through DNA analysis to belong to a Denisovan, provided the first substantial fossil remains of Denisovans beyond isolated teeth and a finger bone. Some researchers initially proposed a connection between Yunxian and the Harbin Denisovan, suggesting Yunxian might represent early ancestors of the Denisovan lineage. However, the Yunxian redating eliminates this hypothesis by placing the skulls too far back in time (1.77 million years versus Denisovans' emergence 700,000 years ago).

What advantages would a larger brain provide to Homo erectus for survival and adaptation?

A larger brain, with Homo erectus reaching 900-1,000 cubic centimeters compared to smaller-brained earlier hominins, enabled more complex neural architecture with more neurons and connections. This supported greater memory capacity, more sophisticated problem-solving, improved planning abilities, and enhanced social communication. These cognitive advantages would have been crucial for learning to navigate new environments, inventing and improving tools, planning hunts, and transmitting knowledge to younger generations across multiple generations.

What role did paleomagnetic dating play in the original age estimates, and why were they less precise than cosmogenic nuclide analysis?

Paleomagnetic dating relies on measuring the magnetic field orientation in sediment layers and comparing these patterns to a known magnetic timescale. This method provided an approximate age range for the Yunxian skulls (around one million years) but couldn't pinpoint precise dates because the magnetic polarity pattern isn't unique to one specific time period. Cosmogenic nuclide analysis, which measures isotope accumulation in specific mineral grains, provides much greater precision because it directly measures the age of the burial rather than relying on pattern matching.

Word count: 6,847 words Reading time: 34 minutes

Key Takeaways

- Yunxian skull fossils redated to 1.77 million years ago using cosmogenic nuclide analysis, making them the oldest Homo erectus remains in East Asia

- Homo erectus spread from Africa to Georgia and central China in just 130,000 years, demonstrating remarkably rapid geographic expansion and adaptive capabilities

- The new dates eliminate the hypothesis that Yunxian skulls are early Denisovans, as the temporal gap (over 1 million years) is too large for direct evolutionary connection

- Stone tools from Xihoudu (2.43 million years) and Shangchen (2.1 million years) predate Homo erectus emergence, suggesting earlier hominin species dispersed from Africa before Homo erectus evolved

- The fossil evidence reveals multiple waves of human dispersal from Africa, with at least two different hominin species attempting to colonize distant continents at different times

![Ancient Homo Erectus Fossils from China Reveal Rapid Human Migration [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ancient-homo-erectus-fossils-from-china-reveal-rapid-human-m/image-1-1771609258544.png)