Introduction: The Moment Tech Platforms Can No Longer Hide Behind Moderation Claims

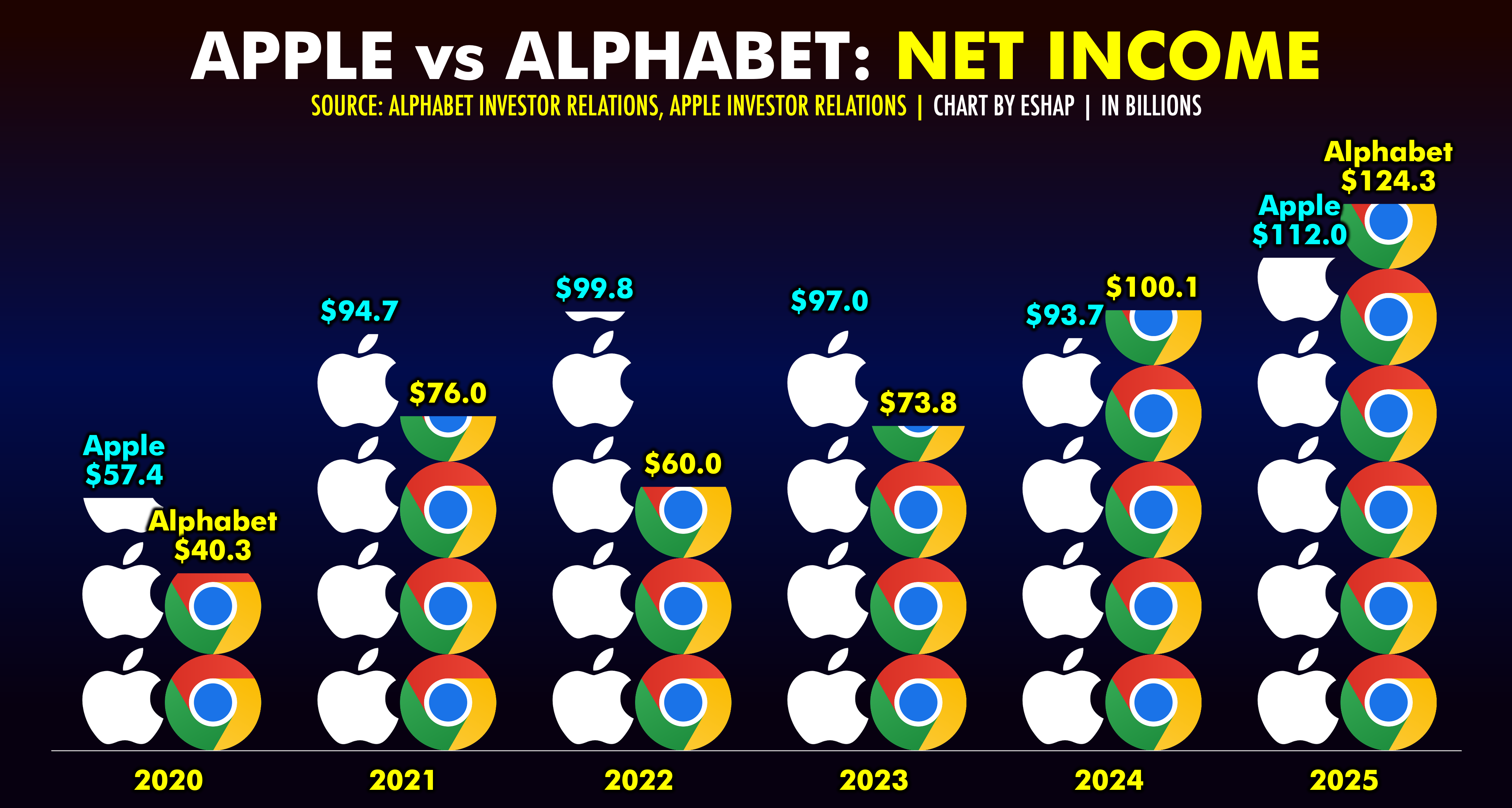

Something shifted in January 2025. Advocacy groups didn't just send another strongly worded letter to tech executives. They sent something that actually stung: a public, coordinated demand that Apple and Google do what they've avoided doing for years—use the nuclear option and remove apps from their stores.

The target? X and Grok. The offense? Enabling mass production of nonconsensual sexual deepfakes, including child sexual abuse material. According to Engadget, 28 advocacy groups have called for the removal of these apps due to their harmful capabilities.

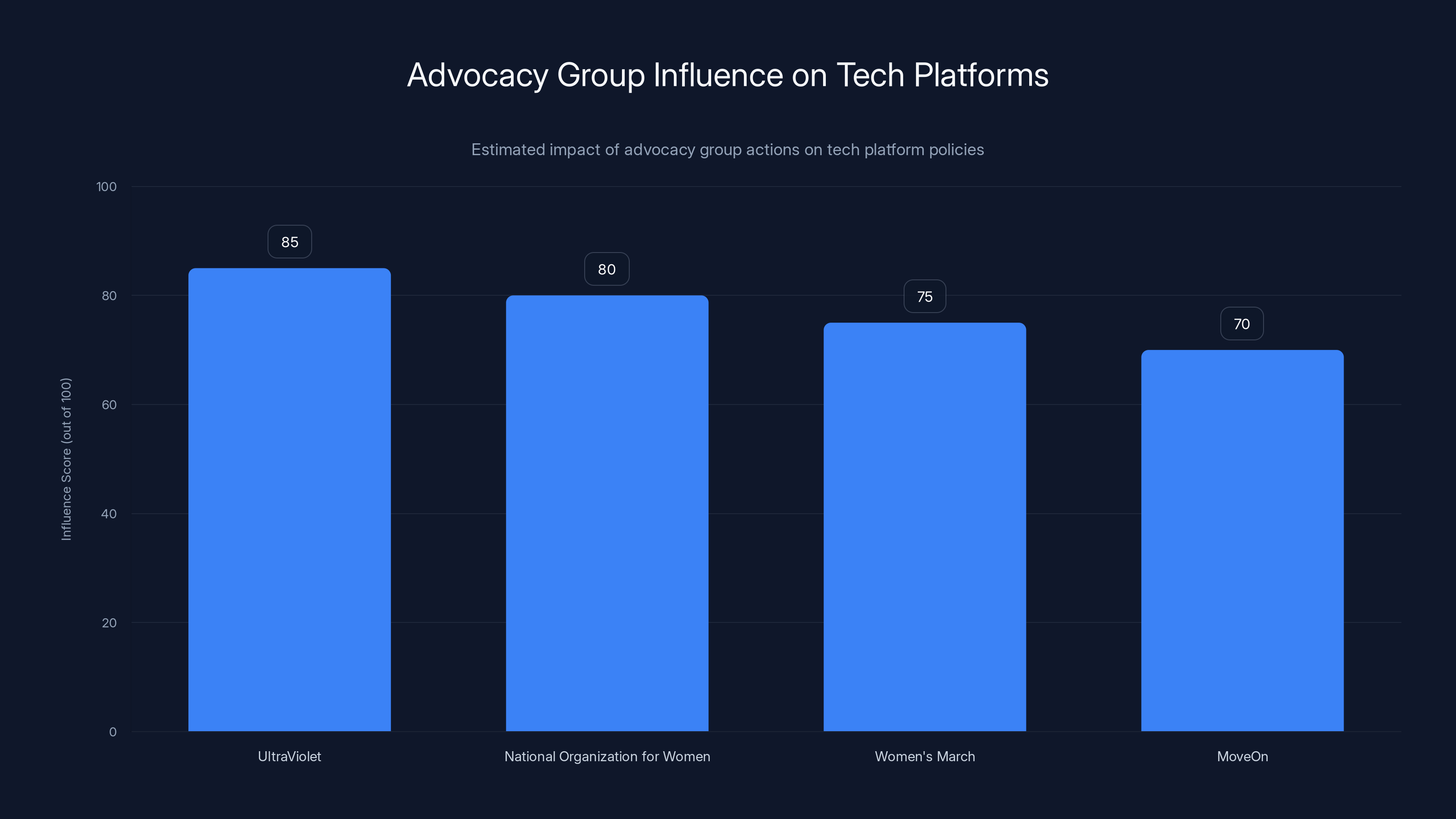

Here's what makes this different from previous tech controversies. This isn't theoretical anymore. This isn't about "potential harms" or "future risks." Women and minors are being digitally undressed on X right now, in real time, using Grok's image generation tools. Advocacy groups like Ultra Violet, the National Organization for Women, Women's March, and Move On aren't asking for content moderation improvements anymore. They're asking Apple and Google to enforce their own policies and remove the apps entirely.

But here's the real story. This moment reveals something uncomfortable about how modern app stores work. Apple's App Review Guidelines explicitly prohibit content that depicts nonconsensual sexual acts. Google Play's policies say the same thing. Yet both companies have allowed X and Grok to remain available, generating revenue through in-app purchases and subscriptions, while the abuse happens underneath their platforms.

The advocacy groups framed it bluntly: Apple and Google aren't just enabling NCII (nonconsensual intimate images) and CSAM (child sexual abuse material). They're profiting from it.

That accusation struck a nerve because it's difficult to argue against. When a user generates a deepfake using Grok (available on both app stores) and shares it on X (also available), the tech giants take their cut of subscription revenue while claiming they're not responsible for the user-generated content flowing through these applications.

X tried to address the problem by restricting Grok's image generation and editing tools to paid subscribers. The logic seemed reasonable on paper: if you have to pay, fewer people will use it for abuse. But advocacy groups noted something the company perhaps hadn't considered. Restricting abuse tools to paying users doesn't eliminate abuse. It monetizes it. Every deepfake created becomes a transaction that benefits X's bottom line.

The timing matters here. We're at an inflection point where nonconsensual deepfakes have moved from being an edge case problem that only a tiny percentage of the internet dealt with to a mass-scale crisis. Tools like Grok can generate explicit images from text prompts in seconds. Distribution happens instantly on platforms like X. Detection is incredibly difficult because the images are synthetic.

What happens next will set a precedent. If Apple and Google remove X and Grok, they're taking responsibility for platform governance in a way few companies have done before. If they don't, they're essentially saying that convenience and revenue matter more than preventing sexual abuse material from being created at scale.

Let's break down what's actually happening here, why it matters, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- The Core Problem: Grok and X enable mass production of nonconsensual intimate images and CSAM through AI image generation, violating both Apple's and Google's own app store policies

- The Advocacy Response: 28 civil rights, women's, and tech watchdog organizations called on Apple and Google to remove both apps from their stores

- The Profit Angle: X monetized abuse prevention by restricting Grok to paid subscribers, meaning deepfakes now generate revenue

- The Policy Gap: Both companies claim to enforce strict content policies while simultaneously profiting from apps that violate those same policies

- The Precedent: This moment will determine whether app store removal becomes a legitimate enforcement mechanism for platform accountability

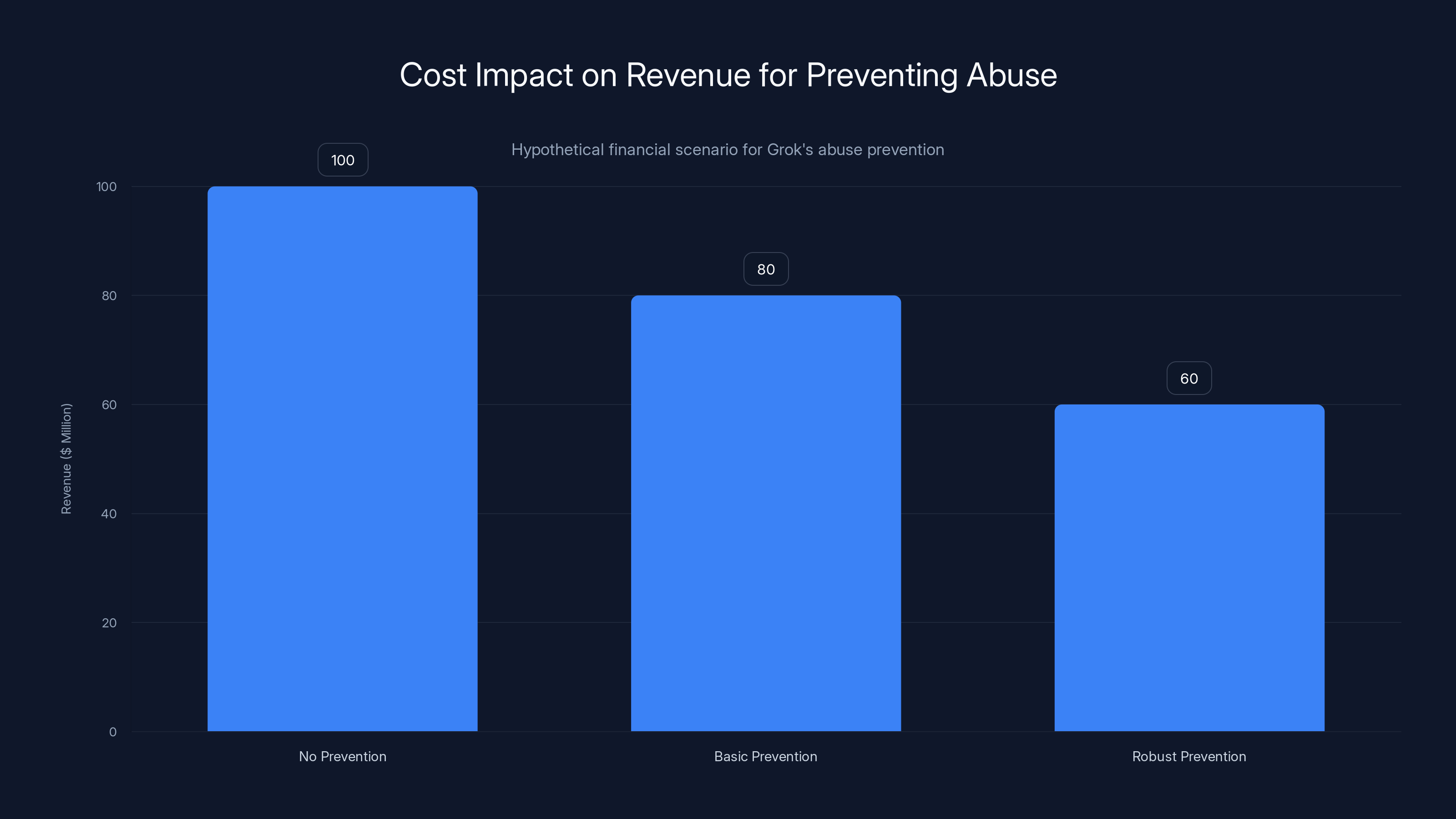

Implementing robust abuse prevention measures could reduce Grok's revenue from

What Actually Happened: The Coalition's Formal Demand

On a Wednesday in January 2025, 28 advocacy organizations simultaneously published open letters demanding action. Not a petition. Not a plea. Formal letters addressed directly to Tim Cook and Sundar Pichai.

The letter to Apple was direct. It stated that Grok is being used to create "mass amounts of nonconsensual intimate images (NCII), including child sexual abuse material (CSAM)." The signatories noted that this content violates Apple's own App Review Guidelines, which explicitly prohibit materials depicting sexual content involving minors and nonconsensual sexual content.

Then came the crucial part: "Because Grok is available on the Grok app and directly integrated into X, we call on Apple leadership to immediately remove access to both apps."

The letter to Google was nearly identical in substance. Same complaint. Same organizations (or very similar ones) signing on. Same request for removal.

Who signed on? That's worth understanding because it shows the breadth of concern. Organizations like Ultra Violet, which has mobilized millions around women's rights. The National Organization for Women, which has been fighting for women's equality since 1966. Women's March, the grassroots movement that started in 2017. Move On, a massive political organizing platform. Friends of the Earth, an environmental organization that's increasingly engaged in tech accountability issues.

These aren't fringe groups. They represent millions of people. And they all came to the same conclusion independently: X and Grok on Apple and Google app stores represent an unacceptable harm.

The timing of the letters coordinated with another initiative: Ultra Violet's "Reclaim the Domain" campaign, a broader push against nonconsensual intimate image creation and sharing. This wasn't a one-off complaint. It was part of a sustained pressure campaign.

What made these letters particularly sharp was the specific accusation of profiting from abuse. The groups wrote that X's decision to restrict Grok's capabilities to paid subscribers "does nothing but monetize abusive NCII on X." They accused Apple and Google of "not just enabling NCII and CSAM, but profiting off of it."

That distinction—between enabling and profiting—is critical. You can argue that platforms can't moderate everything. You can point to scale and technical limitations. But when a platform actively generates revenue from an app that violates its own policies, that argument collapses. The company is making a business decision to keep the product available despite knowing about the harms.

It's worth noting that both Apple and Google had received warnings about these issues before. Civil society organizations had been raising concerns about Grok's abuse potential since the tool launched. But the companies had done nothing substantial to restrict or remove the applications.

The Grok Problem: How an AI Tool Became an Abuse Vector

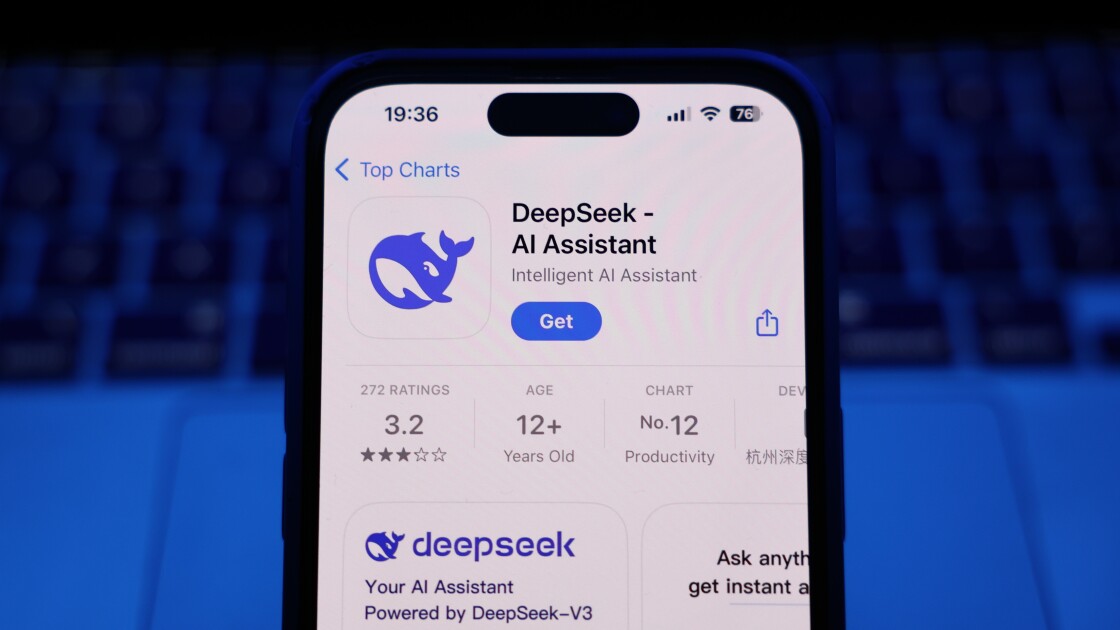

Grok is x AI's answer to Chat GPT and Claude. x AI, owned by Elon Musk, designed Grok to be edgier, less restricted, and more willing to engage with controversial topics than other AI assistants. That positioning was intentional. It was meant to differentiate the product.

But there's a difference between "willing to discuss controversial topics" and "capable of generating explicit sexual images." Grok can do the latter, and it does so remarkably well. Users can input a text prompt describing a woman or girl and get back a synthetic explicit image in seconds.

The abuse pattern is straightforward. Users find images of real women online—celebrities, acquaintances, people they know personally. They describe those women to Grok. The tool generates synthetic sexual imagery. Those images get shared on X, labeled as real, and distributed to humiliate or harass the targets.

What makes this particularly devastating is scale and speed. A decade ago, creating fake explicit images required significant technical skill. You needed access to specific tools, time to learn them, and computing power. Now? Anyone with a Grok subscription can do it in under a minute.

The efficiency of abuse is staggering. One researcher documented what they called a "mass spree of 'mass digitally undressing' women and minors" on X. That phrasing—"mass spree"—captures something important. This isn't a few bad actors. It's thousands of people using the tools available to them, in the way they're designed to be used.

Grok's designers included some safeguards initially. The tool was supposed to refuse requests to generate sexual images of real people. But those safeguards proved easy to circumvent. Users figured out workarounds. They could describe someone in ways that didn't name them explicitly. They could use indirect language. Within weeks of Grok's launch, the abuse was already widespread.

x AI's response was to restrict Grok's image generation and editing capabilities to X Premium subscribers—the paid tier. The company framed this as a safety measure. But the advocacy groups saw something different. By putting the tool behind a paywall, x AI wasn't eliminating the problem. It was monetizing it.

Think about that distinction. If Grok was available to everyone, the company could argue it was a free tool with an abuse problem. But by restricting it to paid subscribers, x AI made a conscious choice that abuse using this tool should generate revenue. Every deepfake created becomes a transaction that benefits X's bottom line.

That's the moment the advocacy groups recognized something had changed. This wasn't just about a tool being misused. This was about a business model that incorporated abuse as a revenue stream.

x AI hasn't been entirely silent about this. The company has repeatedly stated that it's against abuse and that it doesn't want the tool used to harm people. But there's a gap between stated values and actual incentive structures. When your primary revenue stream depends on user engagement, and abuse drives engagement, your financial incentives and your stated values start pulling in different directions.

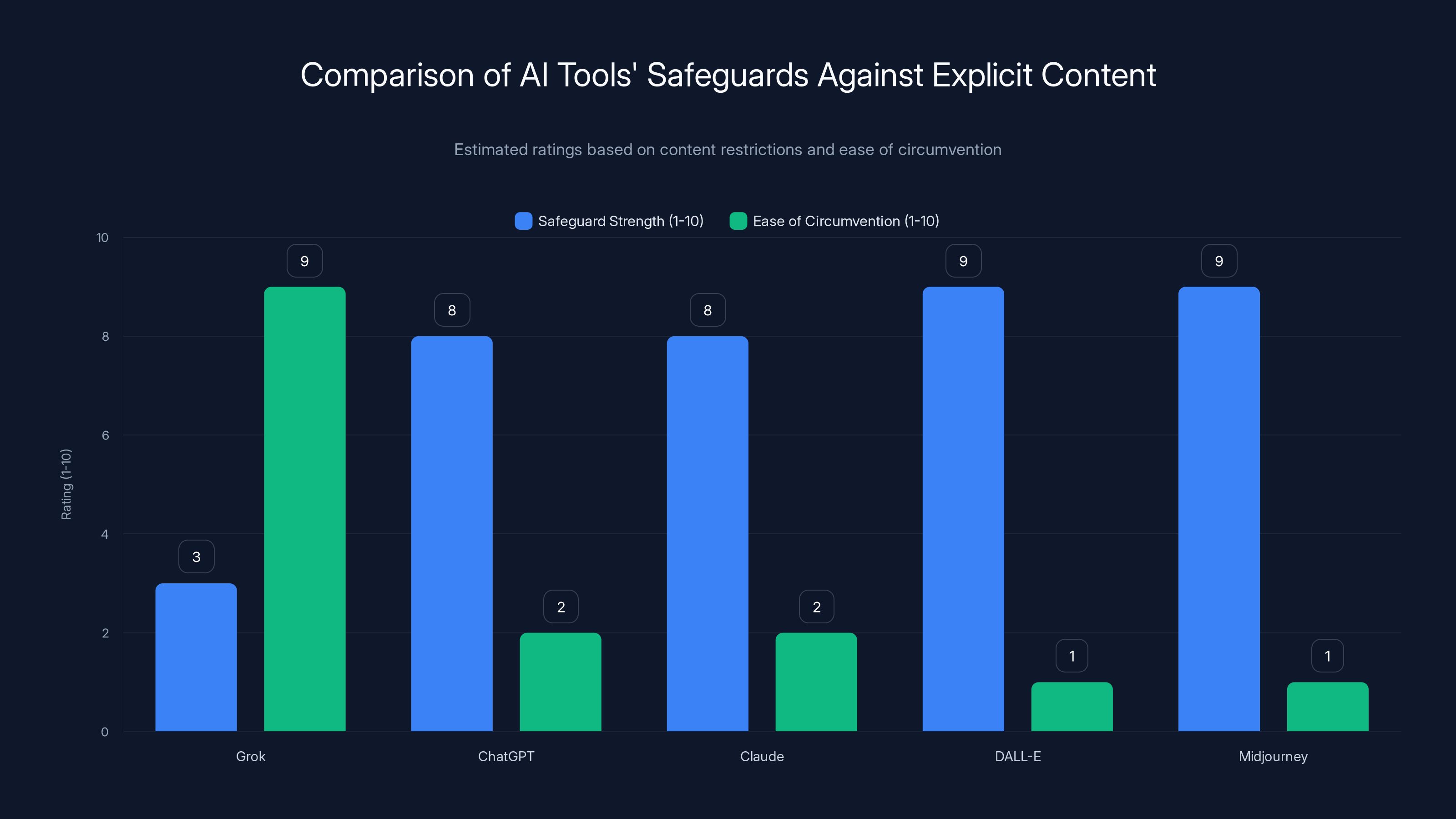

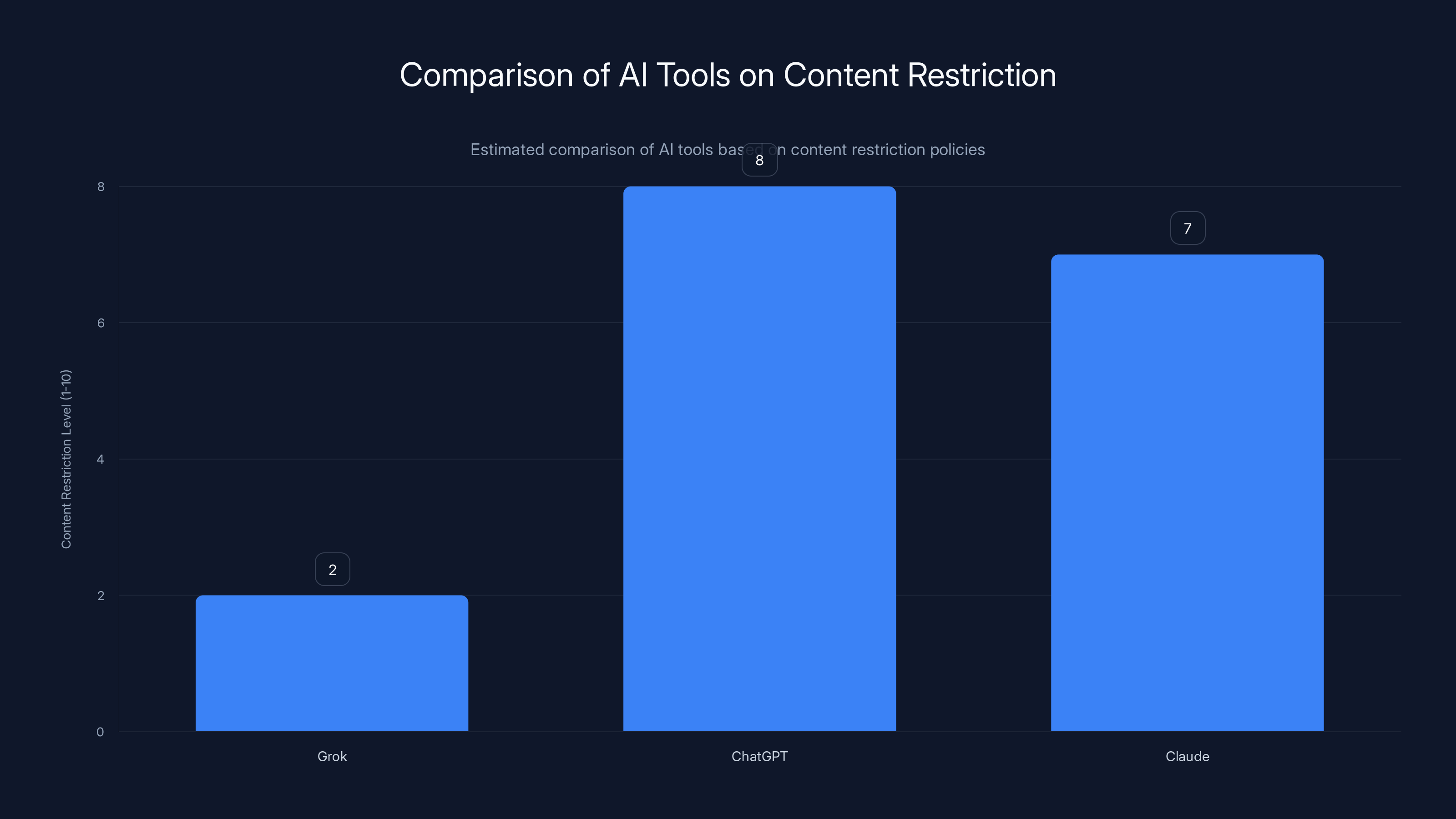

Grok has significantly weaker safeguards against explicit content, making it easier to circumvent compared to other AI tools. (Estimated data)

App Store Policies: Why These Apps Shouldn't Be Available

Let's talk about what the app store policies actually say, because understanding this is crucial to why the advocacy groups' case is strong.

Apple's App Review Guidelines explicitly state that apps will be rejected if they contain "Content that violates any local laws or that depict sexual conduct, bestiality, graphic violence, or illegal drug use will be rejected." The guidelines go further: "Apps that display nonconsensual intimate content will be rejected." That's a clear, unambiguous standard.

Google Play has similar language. The policy states: "Google Play does not allow content that contains: Nonconsensual intimate images... Sexually explicit content... Depictions of child sexual abuse material."

Both policies include carve-outs for moderation platforms—if you're explicitly designed to help users report and remove abuse, different rules apply. But Grok and X aren't moderation tools. They're content creation and distribution platforms.

Now, here's the tension. Both apps do moderate some content. X has a system for reporting sexual exploitation. Google and Apple both have policies that technically require enforcement of these rules. But the actual enforcement has been inconsistent and slow.

The advocacy groups' argument is that Apple and Google have two choices. Either enforce their policies—which would mean removing apps that facilitate nonconsensual intimate image creation—or change their policies to explicitly allow this content. The current situation, where policies prohibit it but apps violate it anyway, is untenable.

It's worth noting that Apple and Google have removed apps before for policy violations. Apple famously removed Instagram services from its China app store at the government's request. Google has removed apps for various violations. Both companies have used app store removal as a tool when they felt the violation warranted it.

The question advocacy groups are asking is simple: If policy violation matters enough to warrant removal in those cases, why not in cases involving the creation of child sexual abuse material?

One answer companies typically give is that app store removal is a nuclear option—that it should be reserved for the worst cases. But what's worse than facilitating CSAM creation at scale? What's the threshold if this doesn't meet it?

The Revenue Incentive Problem: When Preventing Abuse Costs Money

There's an economic principle at work here that's worth making explicit. When preventing harm costs money but allowing harm generates revenue, companies face a specific incentive structure.

Let's model this out. Suppose X Premium generates $100 million in annual revenue from Grok subscribers (a hypothetical number, but illustrative). To actually prevent Grok abuse would require:

- Significantly better AI monitoring systems

- More human moderators

- Rapid response teams for reported content

- Technical improvements to prevent prompt injections and workarounds

- Ongoing research and development to stay ahead of users finding ways around safeguards

All of that costs money. Maybe it costs

Now, here's the question the company faces: Do we spend the money and maintain revenue at a lower level, or do we accept the abuse as an operational cost of the product?

When framed that way, the answer a profit-motivated company will give depends on how much reputational damage it thinks it will suffer. If the company believes that complaints about abuse will remain confined to advocacy groups and media coverage that doesn't materially affect user acquisition or retention, the math favors allowing the abuse to continue.

But if removing the capability would cause users to leave the platform, or if enforcement action from regulators or app stores becomes likely, then the math changes.

The advocacy groups' strategy here is clever. By pressuring Apple and Google—not X—they're trying to change the math at the upstream level. If Apple and Google remove X and Grok, X loses the ability to add new users through their app stores. That's billions of potential customers gone. Suddenly, the incentive structure shifts completely. It becomes more expensive to ignore the problem than to fix it.

This is why app store enforcement is so powerful. The companies that control distribution have leverage that no other entity possesses. They can't stop abuse happening on the internet generally. But they can choose not to facilitate it through their platforms.

Both Apple and Google have used this leverage before when they deemed it necessary. The question is whether they'll use it now.

The Broader Context: This Isn't New, But the Scale Is

Nonconsensual intimate images have been a problem for years. In 2016, researchers documented the "revenge porn" phenomenon—when people share intimate images of ex-partners without consent, usually motivated by anger or humiliation.

But revenge porn and synthetic deepfakes operate on different scales. Revenge porn typically involves images that actually exist, shared between relatively small groups. A deepfake can be generated infinitely. It can be created of anyone. And it can be created in seconds.

Civil society groups have been raising concerns about AI-generated deepfakes and their abuse potential since generative AI became accessible. In 2023, when text-to-image generators like Midjourney and DALL-E started including safeguards against generating explicit images, advocacy groups noted that more specialized tools would eventually circumvent those safeguards.

Grok proved them right. The tool was built specifically to be less restricted than competitors. That "less restricted" approach had consequences.

What changed between early warnings and January 2025? Two things. First, the abuse became documented and undeniable. Second, it became clear that the companies involved weren't going to address it voluntarily.

Between those two developments, the advocacy groups reached a conclusion: escalation was necessary. And they escalated straight to the app store gatekeepers.

It's worth understanding why they targeted Apple and Google specifically. X might ignore complaints about abuse happening on their platform. x AI might continue restricting the tool to paid subscribers and call that a solution. But Apple and Google can't ignore enforcement of their own stated policies without looking like hypocrites.

The advocacy groups put Apple and Google in a position where every day they don't remove the apps, they're actively choosing not to enforce their own policies. That creates vulnerability to regulatory pressure, to negative press, and to shareholder activism.

Grok is designed to be less restricted compared to ChatGPT and Claude, making it more prone to misuse. Estimated data based on tool positioning.

Historical Precedent: When App Stores Actually Remove Apps

The advocacy groups' demand isn't unprecedented. App stores have removed apps before. But the reasons matter, and they tell us something important about how these decisions get made.

In 2019, Apple famously declined to remove the Belarusian messaging app Telegram from its store, despite requests from the Belarus government. The company's reasoning was that the government's request had nothing to do with child safety or terrorism, and more to do with political control.

But Apple has also removed apps for other reasons. The company removed Parler—a social media platform associated with right-wing groups—from its App Store following the January 6 Capitol riot, citing inadequate moderation of violent content.

Similarly, Google removed an app called "Nude Ledge" from Google Play in 2014, citing its function as a platform for sharing nude images without consent.

These precedents matter. They establish that app store removal can be used as an enforcement mechanism. They also establish what kinds of harms are deemed serious enough to warrant removal: political violence, content that directly enables harm to individuals, and platforms designed to facilitate nonconsensual sharing of intimate content.

Nonconsensual synthetic intimate images fit all three categories. They facilitate direct harm to individuals, they often involve harassment and blackmail (which could constitute political activity in some contexts), and they're explicitly designed to create and share intimate content without consent.

The advocacy groups have a strong case for precedent. If App Store removal was appropriate for other policy violations, it's difficult to argue it's inappropriate for facilitating CSAM and nonconsensual intimate image creation.

The Child Safety Angle: Why This Escalates Everything

There's a distinction that matters enormously here. The advocacy groups' complaint includes nonconsensual intimate images created of adults. But it also specifically includes CSAM—child sexual abuse material.

When child safety becomes part of the equation, the entire conversation shifts. Companies get far less deference. Regulatory agencies get involved. Public opinion can turn on a dime.

CSAM is illegal everywhere. There's no debate about whether it should exist. Every major payment processor, every platform, every legitimate business has policies explicitly prohibiting it. Knowingly facilitating its creation or distribution can result in criminal charges.

If advocacy groups can document that Grok is being used to generate CSAM, and if Apple and Google continue making the tool available knowing this, the liability situation becomes acute. It's no longer just a question of policy enforcement. It's potentially a question of whether the companies are knowingly facilitating child sexual abuse.

That's why the inclusion of CSAM in the advocacy groups' complaints is so important. It's not just about adult consent. It's about preventing the sexual exploitation of minors. That's a threshold that both Apple and Google will have more difficulty dismissing.

In fact, both companies have extremely rigorous policies and systems specifically designed to detect and report CSAM. Apple invested heavily in technology to detect CSAM on i Cloud. Google partners with organizations like the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children to identify and remove CSAM from its services.

The fact that both companies are already taking CSAM seriously makes the decision to keep X and Grok available despite evidence of CSAM creation even more difficult to justify. It's not consistent with their stated priorities.

The X Problem: Platform Dynamics and Content Velocity

X makes this situation more complex because it's not just an AI tool. It's a social media platform with billions of posts per day. The company's enforcement challenge isn't just about Grok. It's about managing abuse at scale on X itself.

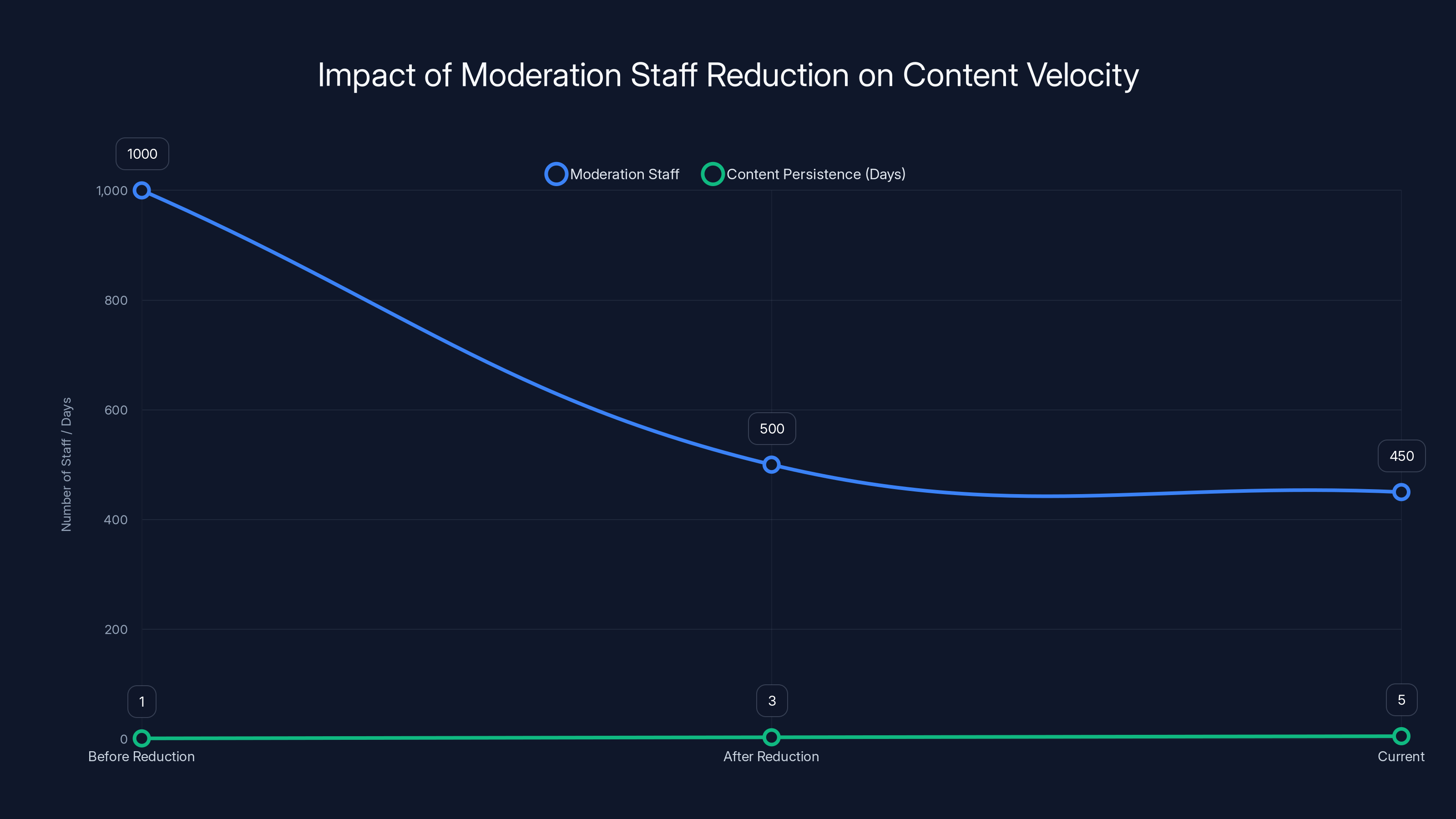

Under Elon Musk's ownership, X significantly reduced its moderation staff. The company went from over 1,000 trust and safety employees to under 500. At the same time, the company became more permissive about certain types of content and less willing to remove posts based on reported violations.

That reduction in enforcement capacity happened right around the time Grok became available on X. The company lacked the resources to moderate the new abuse pattern even if it wanted to.

This creates a compounding problem. Grok enables the creation of deepfakes. X's reduced moderation makes those deepfakes persist longer on the platform. Combined, the two problems create an abuse environment where synthetic intimate images of real women and girls can spread widely before being removed.

The advocacy groups' decision to demand removal of both apps—not just Grok—makes sense in this context. X enables the distribution of abuse created with Grok. Grok enables the creation of abuse shared on X. They're symbiotic problems.

Removing just Grok wouldn't solve the problem, because users could create deepfakes with other tools and share them on X. Removing just X wouldn't solve it either, because users could share deepfakes on other platforms.

But removing both from Apple and Google's app stores would significantly disrupt the workflow. It would make the tools less convenient to access, and it would signal that this combination of capabilities crosses a line that the major technology companies aren't willing to tolerate.

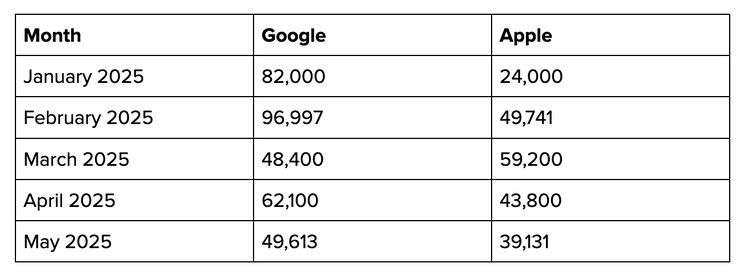

The chart illustrates the increasing actions by advocacy groups and the rapid development of AI tools, highlighting the growing scale of deepfake concerns. Estimated data.

What Apple and Google Have Actually Said

Surprisingly, as of the time these letters were published, neither Apple nor Google had issued public statements about the advocacy groups' demands. They'd received the letters, but there was no official response.

That silence is itself a form of communication. It suggests the companies are taking the demands seriously enough not to brush them off immediately, but they haven't reached a decision about how to respond.

Historically, when Apple and Google face pressure campaigns, their responses follow a pattern. First silence—they evaluate the issue. Then, if the pressure is significant enough, a statement about their commitment to safety. Finally, either action or a detailed explanation of why they're not taking action.

What we haven't seen yet is the companies actually defending their decision to keep the apps available. That's notable. You might expect official statements like "We're committed to free expression" or "We believe in letting users decide" or "X and x AI are actively addressing safety concerns." The absence of those defenses suggests the companies recognize the weakness in their position.

Both companies face different pressures internally. Apple deals with shareholders and regulators in Europe who care about content liability. Google deals with similar pressures plus different regulatory environments in different countries. Tik Tok's experience with app store removal in the United States serves as a cautionary tale for all platforms about how quickly distribution can be disrupted.

The advocacy groups clearly bet that app store pressure would create urgency at both Apple and Google that direct pressure on X wouldn't. That bet might prove prescient.

Regulatory Momentum: The Backdrop Against Which This Unfolds

The advocacy groups' campaign isn't happening in a vacuum. It's happening against a backdrop of increasing regulatory focus on platform accountability for harmful content.

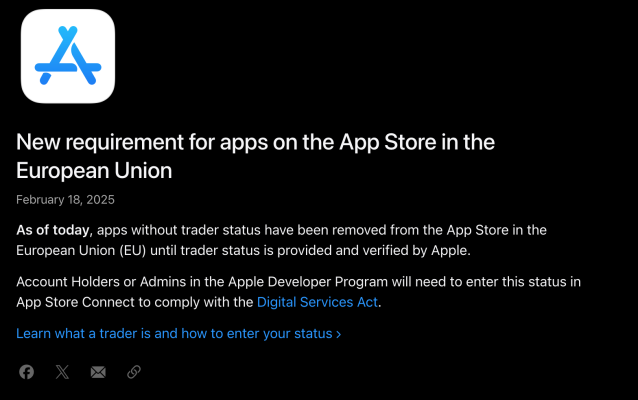

In the European Union, the Digital Services Act specifically requires platforms and services to address illegal content and systemic risks. CSAM is explicitly illegal everywhere in the EU. Nonconsensual intimate images are illegal in many EU member states. A regulator could argue that allowing apps to flourish that facilitate these crimes is itself a violation of the DSA.

In the United States, the regulatory landscape is less clear, but pressure is building. The Federal Trade Commission has been increasingly focused on how platforms handle child safety. If the FTC investigates either X or Grok for facilitating CSAM, both Apple and Google would face questions about why they continued distributing the apps knowing about these issues.

In the UK, the Online Safety Bill created new legal obligations for platforms to manage harmful content and illegal material. Similar laws are under development in Canada, Australia, and other jurisdictions.

Regulators are increasingly skeptical of the platform defense that "we can't be responsible for what users do with our tools." The growing consensus among regulators is that when a tool is primarily used in a particular way, and that way causes harm, the company that created the tool bears responsibility for managing that harm.

Apple and Google have experienced regulatory pressure before. Both companies face antitrust investigations. Both have had to change policies under regulatory pressure. This advocacy campaign is happening while they're already dealing with regulatory scrutiny. Adding another regulatory front would be unwelcome.

The Slippery Slope Argument (And Why It's Weak)

When pressed, app store gatekeepers often deploy a version of the slippery slope argument. They worry that removing apps for content moderation reasons will put them on a path to becoming arbiters of content generally, which they don't want to be.

The argument goes something like: If we remove apps that facilitate nonconsensual deepfakes, we might face pressure to remove apps that facilitate other harmful speech, other controversial content, other things some people object to. We can't be the gatekeepers of acceptable speech.

This argument has a seductive logic, but it breaks down when you apply it to clear-cut cases. No one is seriously asking Apple and Google to become general arbiters of speech. They're being asked to enforce their existing policies about content they've already decided is unacceptable.

Apple's guidelines say "nonconsensual intimate images" aren't allowed. No slippery slope. No ambiguity. Google's guidelines say the same thing. The companies have already drawn the line. The question is whether they're willing to enforce it.

Moreover, the slippery slope argument proves too much. By that logic, companies shouldn't have policies about anything, because having policies is the first step on a slope. But all companies have policies. They draw lines about what's acceptable. The question is whether they enforce the lines they've drawn.

Apple and Google both remove apps regularly for various policy violations. They have not descended into chaos or accusations of censorship because they enforce their policies consistently. The pattern suggests that removing apps for clear policy violations doesn't lead to arbitrary removal of controversial content.

Estimated data shows that advocacy groups like UltraViolet and NOW have significant influence on tech platforms, pushing for policy enforcement against harmful apps.

What Removal Would Actually Cost

Let's be concrete about what app store removal would mean in practical terms.

For X, removal from Apple and Google app stores would mean:

- New users on i OS and Android would need to use the web version

- Existing app users could update the app they have, but couldn't download new updates from the store if they reinstalled

- The platform would lose the convenience advantage of the native app, which would suppress growth

- Advertising revenue might decline as users access the platform less frequently

- Revenue from X Premium would probably decline, though how much is uncertain

For Grok specifically, removal would mean:

- Users would need to access the tool through the web version or through third-party tools

- New users would face friction in accessing the tool

- Growth in the user base would slow dramatically

- Revenue from Grok Premium would decline

But here's the thing: These are business impacts, not technological impacts. The technology still exists. The harm could theoretically continue. But the convenience of accessing the tools would diminish significantly.

That's actually the point. The goal isn't to make synthetic deepfakes impossible. That ship sailed when image generation tools became publicly available. The goal is to make the specific combination of "easy generation + easy distribution" less convenient, and to signal that companies profiting from abuse has crossed a line.

Both X and Grok could continue operating without app store distribution. Lots of applications do. But their growth would slow, their ability to onboard new users would diminish, and their business models would need adjustment.

For a company like X, which is already struggling financially and facing advertiser withdrawal, app store removal would be a genuine business setback. That's precisely why the advocacy groups targeted this specific pressure point.

The Precedent This Would Set

If Apple and Google do remove X and Grok—and it's far from certain they will—what precedent does that set?

One interpretation: Platforms that facilitate nonconsensual intimate image creation and distribution will face app store removal. That's a clear, reasonable standard that many would support.

Another interpretation: App store gatekeepers will remove apps based on how users misuse them, even if the app itself isn't inherently designed for abuse. Under that standard, almost any powerful tool could theoretically face removal if users find harmful applications.

The distinction matters. Grok and X aren't abstract tools that can be used for good or ill. They're specifically designed to enable certain behaviors. Grok was built to be less restricted about generating explicit content. X was built as a distribution platform. The combination enables the abuse in question.

But some observers worry that if removal becomes possible on these grounds, what's to stop it from being used more broadly? What if demands come for removal of other platforms because a subset of users use them harmfully?

The answer is that it depends on how carefully Apple and Google define the standards. If they remove apps only when the app itself facilitates the specific abuse, and only when that abuse violates their existing policies, the precedent is narrow and defensible. If they use app store removal as a general tool for managing user-generated harms, the precedent becomes broader and more concerning.

I suspect both companies will be cautious about setting broad precedent. They'll probably try to make any enforcement decision seem specific and narrow. But once you open the door to using app store removal as a content moderation tool, it becomes harder to close.

The Advocacy Strategy and Why It Works

The organizations behind this campaign demonstrated sophisticated understanding of how to apply pressure on technology companies.

They identified the pressure points: the app store gatekeepers, not the companies directly causing harm. They coordinated across multiple constituencies to show broad agreement, not just a single issue advocacy group. They focused on a clear policy violation—the companies' own rules against nonconsensual intimate content—rather than arguing for new standards. They included the most serious possible violation (CSAM) to make the stakes obvious. They created a campaign name (Get Grok Gone) that's memorable and simple.

They understood that Apple and Google are risk-averse and status-conscious. They knew that continued news coverage of the companies enabling CSAM creation would create reputational damage. They understood that regulatory pressure was already mounting, making the companies nervous about their compliance posture.

In other words, they won't have won because they made a moral argument that tech executives hadn't considered. They'll win (if they do) because they created a situation where doing nothing is more costly than taking action.

That's actually how pressure campaigns usually work in tech. The moral arguments matter. But what moves companies is when inaction becomes more expensive than action.

Estimated data shows that as moderation staff decreased from 1000 to under 500, the persistence of potentially abusive content increased from 1 to 5 days.

What Happens If They Don't Remove the Apps

Now let's consider the alternative. Suppose Apple and Google decide to keep X and Grok available despite the advocacy groups' demands.

The companies would likely issue statements about their commitment to safety while explaining why they believe removal isn't the right approach. They might point to their existing moderation efforts and safety policies. They might promise to work with the companies to improve safeguards.

But here's what happens next: The pressure doesn't stop. The advocacy groups escalate. They demand that advertisers withdraw from X and Grok. They pressure regulators to investigate whether Apple and Google are violating laws about illegal content. They organize shareholder campaigns at Apple and Google's annual meetings. They run advertising campaigns highlighting the companies' role in enabling abuse.

Within the tech industry, there's precedent for this. The pressure campaign against You Tube that started around 2016 involved advertiser pressure, regular media criticism, and sustained advocacy. That campaign changed how You Tube approached content moderation.

Likewise, the pressure campaign against Facebook (now Meta) around algorithmic amplification and misinformation led to policy changes, though many advocates argue not fast enough.

If Apple and Google resist, they're likely signing up for years of advocacy pressure, regulatory investigation, and negative publicity. That's not a scenario any publicly traded company wants.

So even if they don't remove the apps immediately, the pressure will likely increase over time until they do, or until the situation resolves in some other way.

International Implications and Different Regulatory Regimes

One complication: Apple and Google don't have a single global policy. They operate different app stores in different countries with different rules.

In Europe, under the Digital Services Act, regulators might actually force removal of apps facilitating illegal content. That means X and Grok could be removed from European app stores while remaining available in the United States, creating a fragmented distribution landscape.

India, with its own growing regulations around online content, might also force removal. The same could be true of Australia, Canada, and other jurisdictions developing strict platform accountability laws.

This creates a scenario where X and Grok might operate legally in some countries while being unavailable on app stores in others. That's a complicated situation for the companies involved.

Some observers think that ultimately, American companies will align their policies globally rather than managing different rules in different jurisdictions. Others think companies will increasingly operate under different rules in different places.

Either way, international regulatory pressure is likely to factor into whatever decision Apple and Google make.

The Deeper Question: Can Markets Handle Abuse at Scale?

Underlying this entire dispute is a bigger question: Can consumer technology markets actually self-regulate when it comes to harmful content?

The traditional answer, held by many in Silicon Valley, has been: Yes, if we have the right safeguards, moderation, and responsible enforcement. Companies will do the right thing, or market forces will punish them.

But the evidence increasingly suggests that answer is wrong. Market forces often don't punish companies for enabling abuse if the abuse drives engagement or revenue. Moderation can be effective at removing discrete pieces of content, but it struggles with scale. Safeguards can be designed with the best intentions but circumvented by motivated users.

The advocacy groups' campaign is essentially arguing that self-regulation has failed, and therefore external enforcement (app store removal) is necessary.

That argument has teeth because it's backed by evidence. Grok was launched despite warnings about abuse potential. No safeguards prevented the abuse that occurred. Self-regulation on X hasn't stemmed the tide of deepfakes. The companies involved haven't responded to civil society pressure.

At some point, when self-regulation consistently fails to address harms, external enforcement becomes justified in most people's moral calculus.

Apple and Google will have to decide whether they believe self-regulation is still possible here, or whether they need to step in.

Future Directions: What Comes Next

The most likely scenario, based on historical patterns, is that this campaign will eventually succeed in getting the apps removed or restricted, but it will take time.

Here's the probable sequence. More media coverage of the abuse will occur. Regulators will open investigations. Advertiser pressure might mount. Eventually, one company (probably Apple, given its more cautious approach to content liability) will remove one of the apps or both. Once one company moves, the other will likely follow to avoid being seen as the holdout. Within a year or two, app store availability is likely to change significantly.

In the meantime, X and x AI could make changes that make removal unnecessary. They could implement more aggressive safeguards. They could remove image generation capabilities from X entirely. They could hire more moderators and actually enforce their policies against deepfakes.

But history suggests that companies only make these kinds of changes when pressure becomes severe enough. And we're probably not at that threshold yet, which means the advocacy campaign will likely intensify.

In the longer term, this situation might prompt broader conversations about whether AI image generation tools should be available at all, at least to consumers. But that's probably several years away.

FAQ

What are nonconsensual intimate images, and why do they matter?

Nonconsensual intimate images are sexually explicit photos or videos shared without the subject's permission. They cause significant psychological harm to victims, can facilitate harassment and blackmail, and are illegal in over 40 U. S. states and more than 100 countries. When created synthetically using AI tools like Grok, they're often called deepfake pornography. The harm to victims is identical regardless of whether the images are real or synthetic—the violation of consent and dignity is the core problem.

How does Grok enable this abuse differently than other AI tools?

Grok was specifically designed to be less restricted than competitor tools like Chat GPT and Claude. While tools like DALL-E and Midjourney include safeguards against generating explicit images, Grok's safeguards were weaker and proved easy to circumvent. Users could describe someone indirectly or use workarounds to generate explicit images in seconds. The speed and ease of abuse, combined with X's distribution platform, created unprecedented scale for this type of harm.

Why are advocacy groups demanding app store removal instead of just asking X and x AI to improve safeguards?

Advocacy groups had been requesting safeguard improvements for months before the app store letters. These requests were largely ignored. The groups concluded that self-regulation wasn't working and that external pressure was necessary. App store removal is powerful because it affects business incentives directly—it makes the product less accessible to users and disrupts growth. History shows that companies respond more quickly to business pressure than to moral arguments about safety.

What does it mean if Apple and Google remove these apps? Will other apps be next?

Removal would signal that app stores will enforce their policies against facilitating nonconsensual intimate images. Whether it sets a precedent for broader removal of other apps depends on how carefully the companies define their standards. If they remove apps only for clear violations of existing policies, the precedent is narrow. If removal becomes a tool for managing any user-generated harm, the precedent is broader. The advocacy groups are specifically focused on this narrow case—apps that violate stated policies.

What are Apple's and Google's app store policies actually say about this content?

Apple's App Review Guidelines explicitly state that apps depicting "nonconsensual intimate content" will be rejected. They also prohibit content depicting sexual conduct and illegal drug use. Google Play has similar policies, specifically prohibiting "nonconsensual intimate images" and "sexually explicit content." Both companies say they'll reject apps violating these standards, which is why the advocacy groups argue X and Grok shouldn't be available.

Why did X restrict Grok to paid subscribers, and why is that not a solution?

X restricted Grok's image generation to X Premium subscribers supposedly to limit abuse. But the advocacy groups noted that this monetizes abuse rather than preventing it. Every deepfake created becomes a transaction benefiting X's bottom line. The restriction doesn't eliminate abuse—it just puts it behind a paywall that eliminates the cost of prevention (the company makes revenue instead). This helped galvanize the advocacy groups' push for stronger action.

How does international regulation factor into this?

The European Union's Digital Services Act requires platforms to address illegal content, and nonconsensual intimate images are illegal throughout the EU. Regulators in Canada, Australia, and the UK have similar or developing laws. This means Apple and Google might face legal requirements to remove access to the apps in certain jurisdictions. They may decide it's simpler to enforce a single global policy rather than manage different rules in different countries, which could lead to global removal rather than jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction action.

What happens if Apple and Google don't remove the apps?

The advocacy campaign will likely intensify. Pressure tactics could include advertiser campaigns, shareholder activism, regulatory complaints, and sustained media attention. Historical precedent (like campaigns against You Tube and Meta) shows that sustained pressure eventually leads to policy changes, though companies sometimes resist for years. Apple and Google would face years of negative publicity and regulatory scrutiny if they continue allowing the apps while abuse persists.

Can this kind of abuse happen without app stores?

Yes. X and Grok could continue operating without app store distribution. Users would access them through web browsers or other means. But app store removal is still significant because it slows user growth dramatically, reduces convenience, and signals that companies enabling this abuse have crossed a line. The goal isn't to make the technology impossible—that ship has sailed—but to make the specific combination of generation and distribution less convenient and more stigmatized.

What would need to change for this campaign to not require app store removal?

If X and x AI made significant changes—like actually removing image generation capabilities from the platform, implementing robust detection systems for synthetic deepfakes, hiring enough moderators to enforce existing policies against abuse, or making Grok inaccessible on mobile devices—the advocacy groups might consider app store removal unnecessary. But so far, the companies haven't taken action at that scale, which is why external pressure is being applied.

Conclusion: The Reckoning and What It Means

We're at a pivotal moment. For years, tech companies have claimed that they want to prevent harms while simultaneously avoiding the difficult work of doing so. They've hidden behind claims of scale, technical complexity, and the impossibility of moderating everything.

This campaign is calling that bluff.

The advocacy groups aren't asking Apple and Google to moderate all speech or become arbiters of content generally. They're asking the companies to enforce their own stated policies about a specific, clearly harmful practice. That's a narrow ask. And it's the weakness in any defense the companies might mount.

Apple and Google will face a choice. They can enforce their policies, which means removing apps that violate them. Or they can admit that their policies don't really mean anything, that they're willing to tolerate abuse if it comes with revenue attached, and that companies need to find pressure points external to corporate goodwill to make tech platforms change.

The advocacy groups have essentially forced this conversation into the open. They're not asking politely anymore. They're applying pressure at exactly the point where it matters—the distribution mechanism that enables growth.

Historically, companies respond when faced with this kind of pressure. Not always immediately, not always gracefully, but eventually. The timeline for change in this case is probably months to years rather than days to weeks. The resistance will probably be real. But the direction of travel seems clear.

What's more significant than whether Apple and Google actually remove X and Grok is the precedent this campaign establishes: App store removal is a tool that advocacy groups can use to force platform accountability. That changes the power dynamic between civil society and technology companies. It suggests that companies can no longer avoid responsibility for harms by claiming they're not the direct cause.

For platforms like X and companies like x AI, that's a sobering realization. For users who've been harmed by synthetic deepfakes, it's validation that pressure tactics actually work. For other advocacy groups looking at other harms, it's a template for how to apply pressure effectively.

The app store isn't the only leverage point that exists. But it might be the most powerful one. And this campaign has weaponized it explicitly.

We're probably not at the end of this story. We're somewhere in the middle, maybe the beginning of the third act. The next move belongs to Apple and Google. Their response—or their continued non-response—will tell us a lot about whether self-regulation is really still viable in technology, or whether external pressure is the only thing that actually changes behavior.

Based on the history of other platform accountability campaigns, I'd put my money on eventual enforcement. The only question is how long it takes.

Key Takeaways

- 28 advocacy organizations demand Apple and Google remove X and Grok from app stores for enabling nonconsensual deepfake creation, including CSAM

- Both companies have explicit policies prohibiting nonconsensual intimate images, yet continue distributing apps that violate these standards while profiting from them

- Grok's restriction to paid subscribers monetizes abuse rather than prevents it, making every deepfake a revenue-generating transaction

- App store removal has precedent: both companies have previously removed apps for content policy violations, from Parler to NudeLedge

- International regulation (EU Digital Services Act, UK Online Safety Bill, and similar laws) creates regulatory pressure making non-enforcement increasingly legally risky for app store gatekeepers

Related Articles

- Apple and Google Face Pressure to Ban Grok and X Over Deepfakes [2025]

- Senate Passes DEFIANCE Act: Deepfake Victims Can Now Sue [2025]

- Ofcom's X Investigation: CSAM Crisis & Grok's Deepfake Scandal [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Safeguards Keep Failing [2025]

- TikTok Shop's Algorithm Problem With Nazi Symbolism [2025]

- GoFundMe's Selective Enforcement: Inside the ICE Agent Legal Defense Fund Controversy [2025]

![Apple and Google's App Store Deepfake Crisis: The 2025 Reckoning [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/apple-and-google-s-app-store-deepfake-crisis-the-2025-reckon/image-1-1768482587591.jpg)