Artemis II Crew Quarantine: Why Astronauts Must Isolate Before Moon [2025]

Two weeks before launch, the Artemis II crew disappears from public view. No hugs from family. No handshakes with colleagues. No casual trips to the grocery store. They live in controlled isolation, their every movement monitored by medical experts, their daily routines stripped of the normal human contact the rest of us take for granted.

Sounds extreme? It's actually brilliant preparation for what might be the most challenging two weeks of their lives.

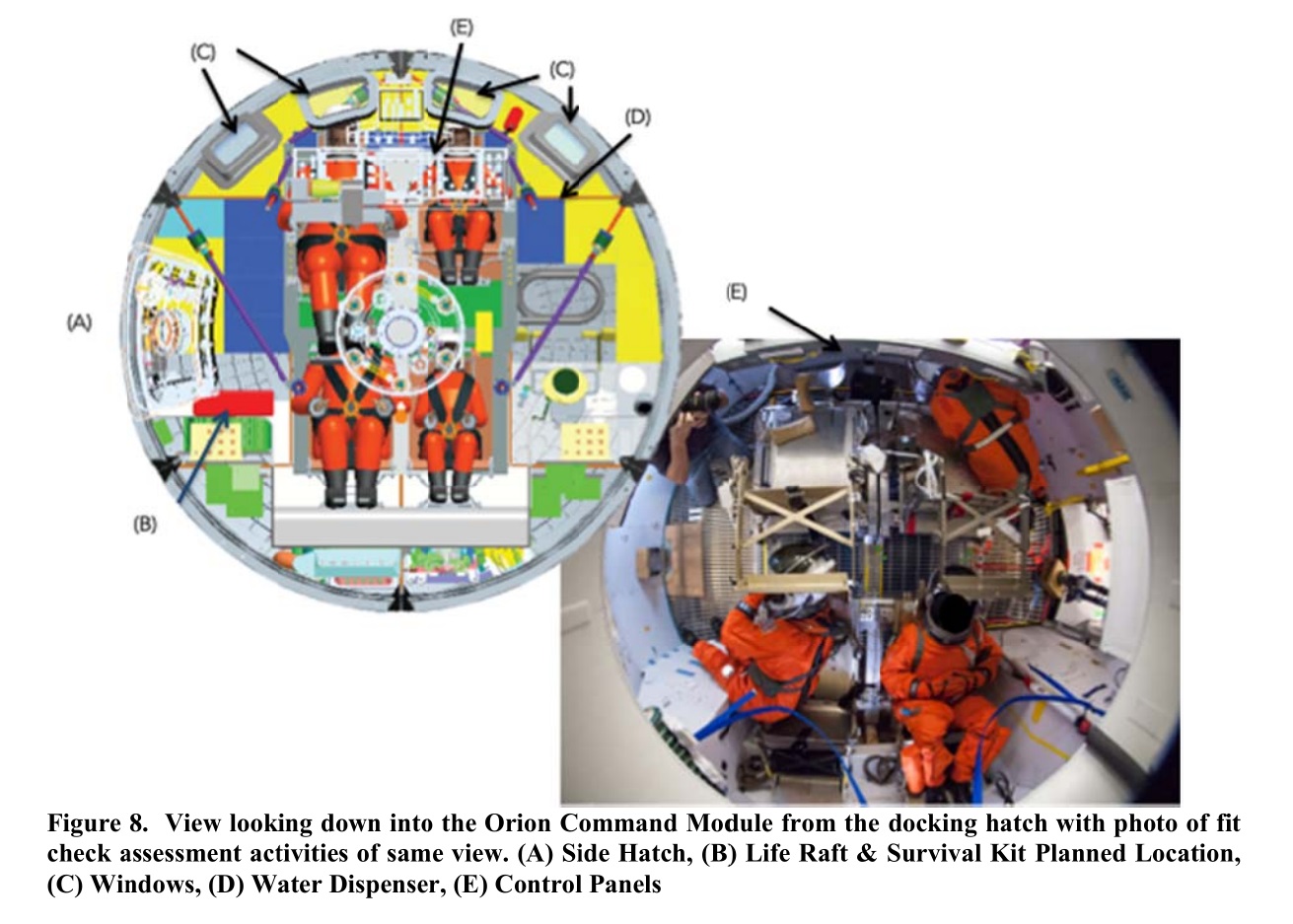

This isn't paranoia or over-the-top caution. This is NASA's Health Stabilization Program, a protocol born from lessons learned during the Apollo era and refined over decades of spaceflight experience. The Artemis II mission represents humanity's return to deep space exploration, carrying astronauts farther from Earth than anyone has traveled since 1972. Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, and Christina Koch from NASA, along with Jeremy Hansen from the Canadian Space Agency, will live inside the Orion spacecraft—a capsule roughly the size of two minivans parked end-to-end—while orbiting the Moon's far side.

The margin for error up there? Essentially zero.

Back here on Earth, during those critical final two weeks before launch, a single virus could compromise the entire mission. A stomach bug could render an astronaut unable to perform critical tasks in microgravity. A cold could escalate into something more serious once they're millions of miles away from medical help. And that's before we even discuss the delicate balance of protecting not just the crew, but an entire celestial body from contamination.

Let's dig into why NASA takes this quarantine so seriously, what the crew actually does during those 14 days, and what happens if someone gets sick just days before lift-off.

TL; DR

- 14-day isolation required: NASA's Health Stabilization Program mandates pre-launch quarantine to prevent illness from compromising the mission

- Orion's cramped environment: The spacecraft interior equals roughly two minivans in size, making illness a safety and performance issue

- Moon's south pole priority: NASA aims for regions where microbes from Earth could survive decades in frozen conditions, making planetary protection critical

- Apollo-era foundation: Quarantine protocols trace back to 1970s lunar missions, updated with modern medical monitoring

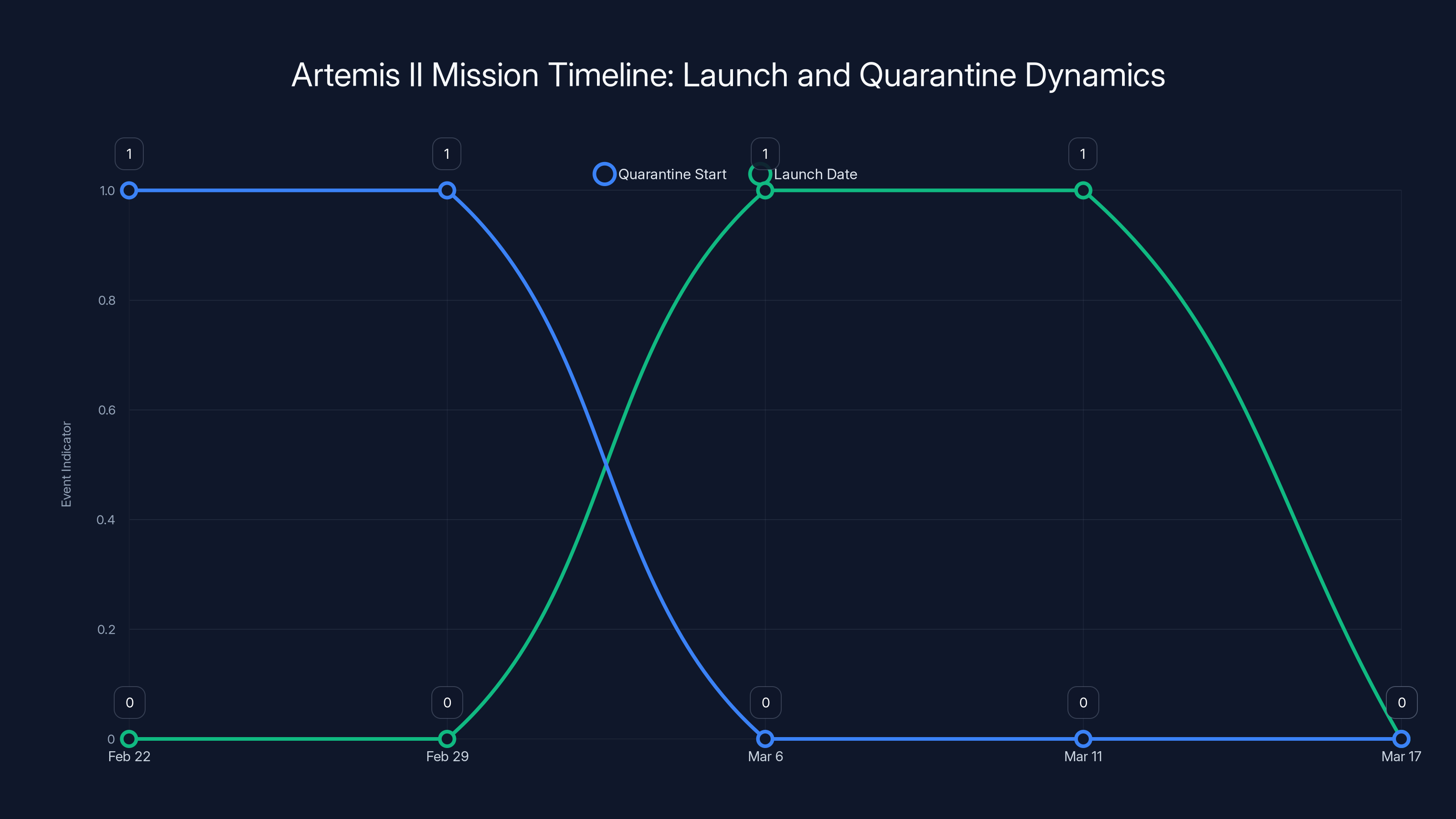

- Launch window shift: Artemis II moved from February 2026 to March 6-11, 2026, with crew already isolated

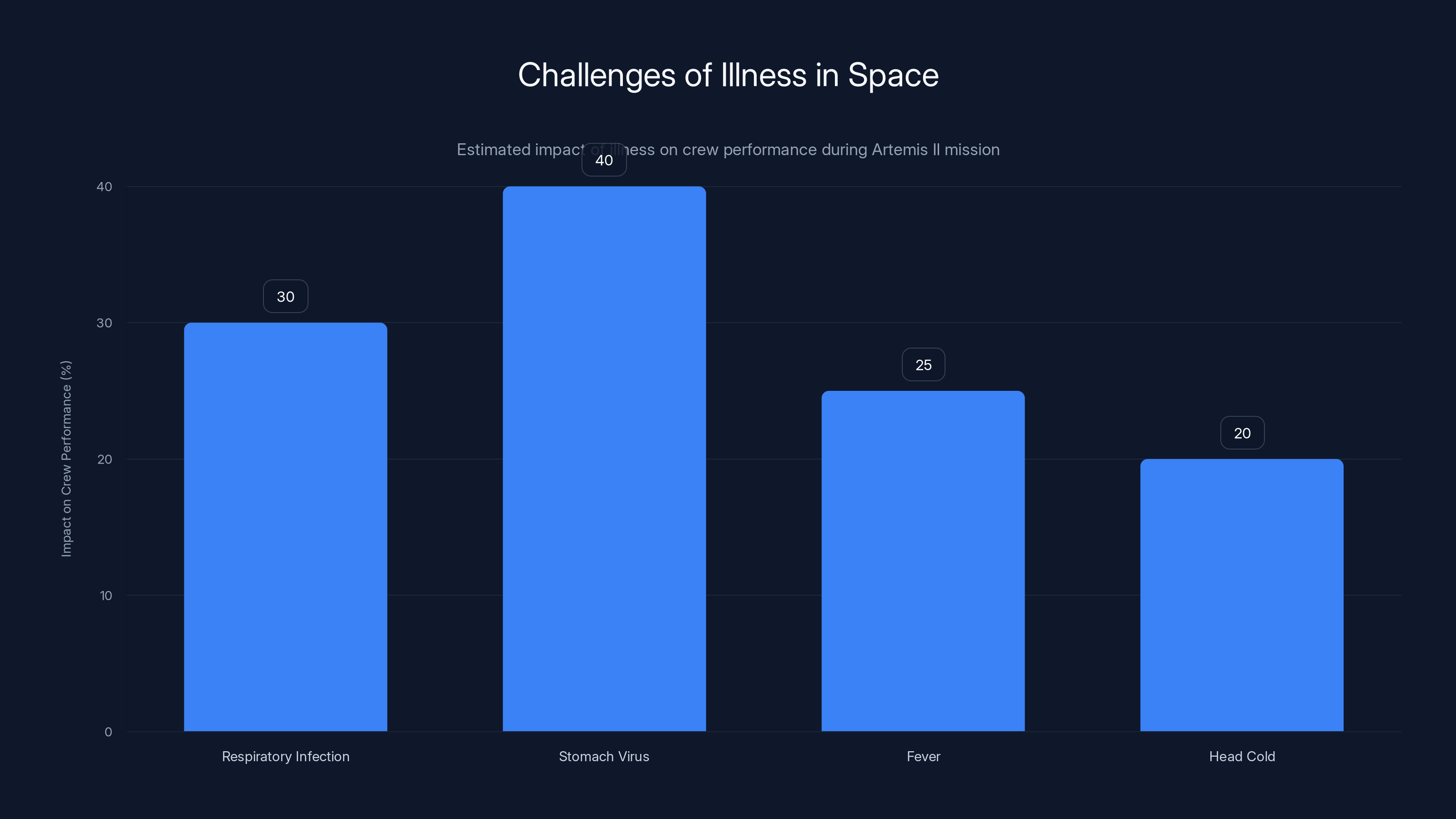

Estimated data shows that illnesses like stomach viruses and respiratory infections can severely impact crew performance, posing significant risks to mission success.

Understanding the Health Stabilization Program: NASA's Quarantine Protocol

The Health Stabilization Program didn't emerge from theoretical concerns or paranoid planning. It emerged from hard experience.

When Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins returned from Apollo 11 in 1969, nobody knew what they might bring back from the Moon. Was the lunar surface sterile? Could alien microorganisms exist in the lunar soil? What if the crew encountered a pathogen their immune systems had never encountered?

NASA didn't take chances. Armstrong and his crewmates spent 21 days in a quarantine facility while physicians monitored them constantly for abnormal symptoms. No signs of infection appeared. No extraterrestrial pathogens emerged. But the protocol stuck around for later Apollo missions, creating a tested framework for protecting crew health before launch.

Today's Health Stabilization Program preserves that foundation while adding layers of modern medical monitoring. The program requires 14 consecutive days of isolation before any crewed lunar launch. During this period, the crew:

- Avoids public places entirely

- Wears N95 masks when they must be around other people

- Maintains physical distance from family members (typically at least six feet)

- Refrains from any contact sports or activities that might cause injury

- Follows a specialized diet designed to support immune function

- Undergoes daily medical checks including temperature readings and symptom screening

- Lives in a controlled environment with filtered air and sanitized surfaces

The four Artemis II crew members are currently at a facility in Houston, where this protocol is in full effect. They can see their families, but only from a distance. They can watch the world outside, but only through windows. It's psychological training as much as medical precaution.

The Orion Spacecraft: Why Being Sick 250,000 Miles Away is Dangerous

Imagine being trapped inside an airplane lavatory with three other people for ten days. That's roughly the living situation the Artemis II crew will endure.

The Orion spacecraft is purpose-built for deep space missions, and every cubic inch is engineered with meticulous precision. But that precision comes at a cost: space. The entire habitable volume of Orion approximates the interior of two standard minivans placed end-to-end. Inside that confined area, the crew must eat, sleep, work, exercise (barely), and manage waste.

Now add illness to that equation.

If one crew member develops a respiratory infection, the other three will be exposed to that infection repeatedly, daily, with no ability to isolate. The Orion's life support system recycles air continuously, which is efficient for resource management but efficient for pathogen transmission too. A stomach virus means someone is using that toilet repeatedly in close quarters with minimal privacy and no escape route.

On Earth, if you're sick, you stay home. You rest. You minimize contact with others. You can visit a doctor if things get serious. In Orion, orbiting the Moon with a round-trip communication delay measured in seconds, those options evaporate.

The mission timeline for Artemis II spans approximately 10 days of actual spaceflight, from launch through splashdown. That's a full week-plus of living in a space roughly equivalent to two minivans. Any crew member operating at reduced capacity due to illness jeopardizes not only their own safety but potentially the safety of the entire mission. Specific tasks—equipment repairs, course corrections, emergency procedures, scientific observations—require peak cognitive and physical performance.

An astronaut with a fever might make a critical error. An astronaut with nausea might become dehydrated, leading to cognitive decline. An astronaut with a head cold might not hear a warning signal clearly. The redundancies are built in, but they assume a fully capable crew.

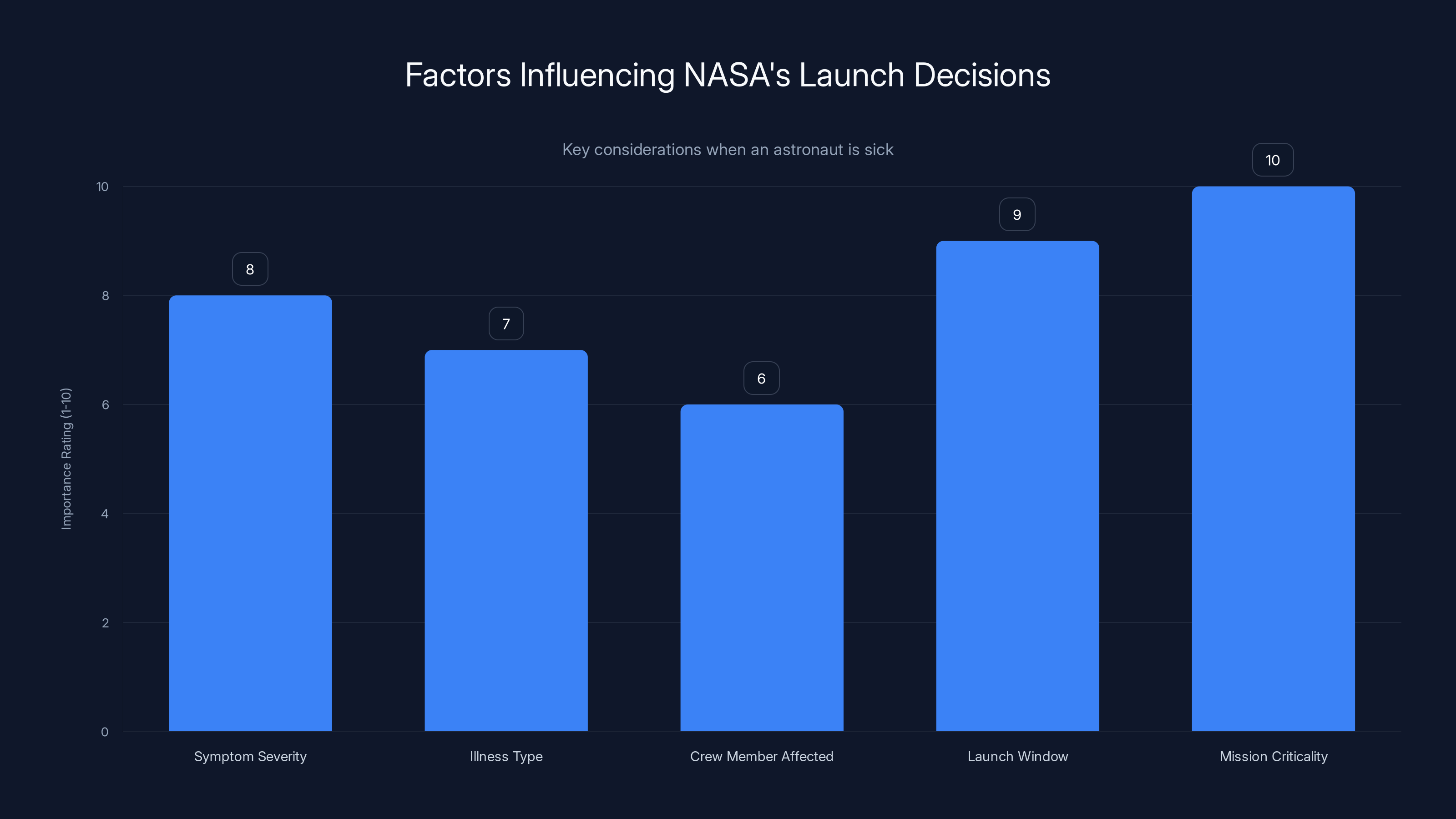

NASA prioritizes mission criticality and launch window availability when deciding to delay a launch due to an astronaut's illness. Estimated data based on typical decision-making processes.

The Lunar Mission Window: March 2026 and Why Timing Matters

The original launch window for Artemis II was February 8, 2026, or shortly thereafter. That date wasn't arbitrary. NASA calculates launch windows based on complex celestial mechanics, orbital mechanics, and mission-specific requirements.

Then NASA moved it to March 6-11, 2026.

The delay came from multiple sources: refinements to the Orion spacecraft, additional testing of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, and schedule adjustments across the entire Artemis program. But regardless of the exact date, the quarantine protocol remains the same. Fourteen days before whenever launch occurs, the crew enters isolation.

That's the critical detail people often miss. The quarantine doesn't start on a fixed calendar date. It starts exactly 14 days before launch. If launch gets delayed by a day due to weather, the quarantine extends by a day too. If a crew member develops symptoms and mission launch is postponed, the 14-day clock resets when the new launch date is confirmed.

This timing sensitivity creates interesting constraints for mission planning. NASA must be reasonably confident in the launch date before starting formal quarantine. A week before the originally scheduled launch, a sudden two-week delay would mean extending quarantine indefinitely, which raises its own challenges. The crew can't stay in isolation forever—mentally and physically, they need baseline freedom to maintain psychological resilience.

Planetary Protection: Preserving the Moon from Earth's Microbes

Here's the thing most people don't realize about the quarantine protocol: it's not just about protecting the crew or ensuring mission success. It's about protecting an entire celestial body.

Earth is filthy with microorganisms. We're talking trillions of bacteria, fungi, and other microscopic organisms living on our skin, in our gut, throughout our environment. They've evolved alongside us. Our immune systems know how to handle them. We don't even notice they're there.

But if those microorganisms end up on the lunar surface, especially in certain protected regions, they could become a serious problem.

NASA's Artemis program specifically targets the Moon's south pole region, including permanently shadowed craters where sunlight never reaches. Why? Because those areas contain water ice—precious frozen water that could support future lunar bases and provide resources for deeper space exploration. These permanently shadowed craters function as natural freezers. Temperatures drop to negative 370 degrees Fahrenheit. Under those conditions, microorganisms from Earth could survive essentially indefinitely. Not thriving, not reproducing necessarily, but persisting in a kind of frozen stasis.

It sounds abstract until you consider the implications. Those south pole regions are scientifically pristine. They hold geological records from the Moon's early formation, information about the solar system's origins, and potentially evidence about how water came to exist on the Moon. If Earth microorganisms contaminate those areas, they become impossible to study properly. A scientist centuries from now, discovering what looks like extraterrestrial life in a lunar crater, wouldn't be able to distinguish between organisms that arrived billions of years ago and bacteria that hitched a ride on an astronaut's spacesuit in 2026.

This is why the quarantine extends beyond the crew themselves. NASA also ensures that equipment, spacesuits, and machinery that will contact the lunar surface are sterilized according to strict planetary protection standards. The crew's health stabilization is one piece of a larger puzzle aimed at preserving the Moon as a scientific resource.

Pre-Launch Medical Screening: What Disqualifies an Astronaut

The quarantine period itself isn't the first layer of medical screening. It's the final layer.

By the time the Artemis II crew enters quarantine, they've already passed extensive medical evaluations over months and years. But during those final 14 days, the medical scrutiny intensifies.

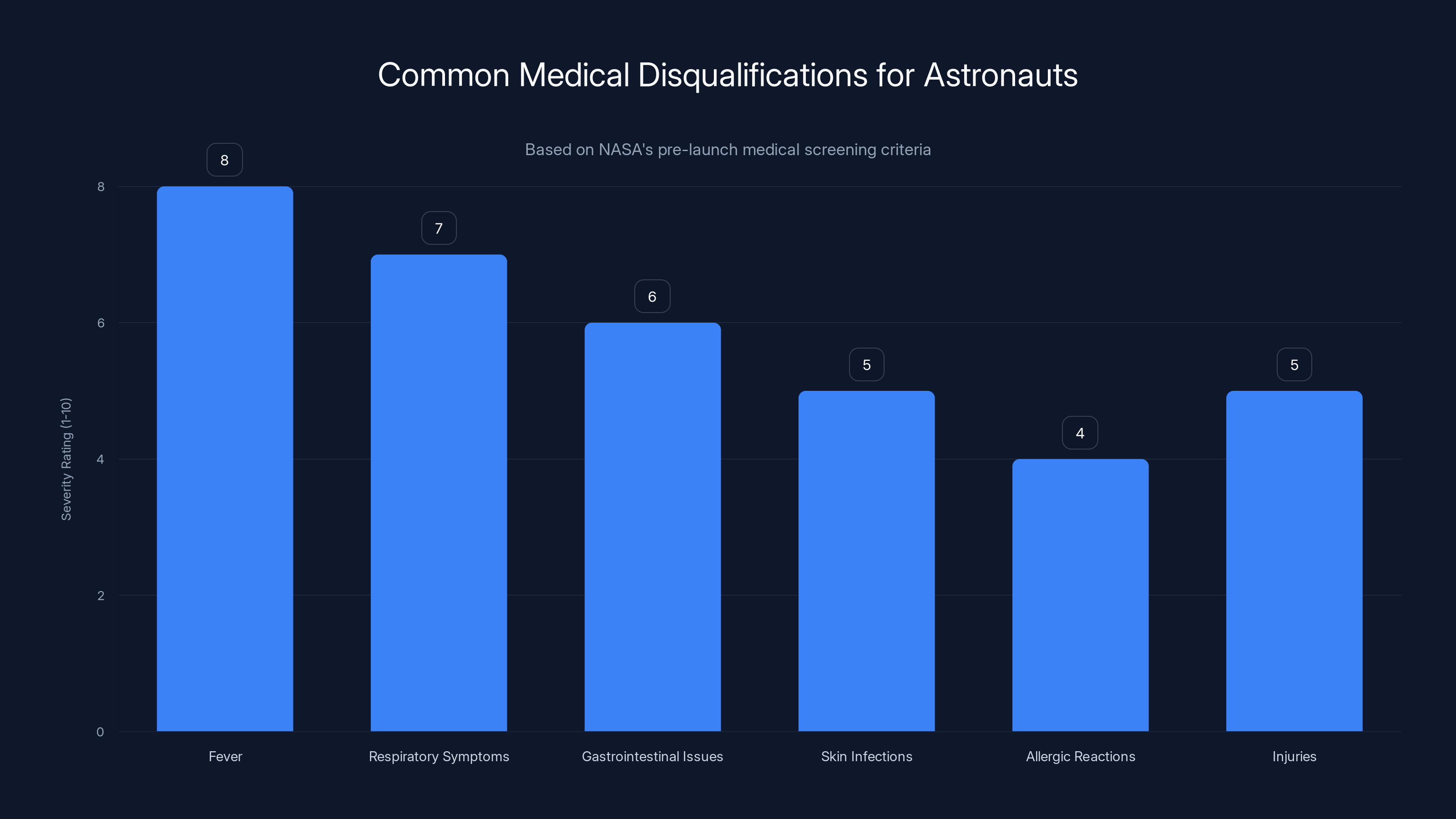

NASA has documented specific conditions that could disqualify a crew member from launch:

- Fever over 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit: Even a slight fever indicates an ongoing infection

- Respiratory symptoms: Cough, congestion, sore throat—any indication of viral or bacterial infection

- Gastrointestinal issues: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea—conditions that could worsen in microgravity

- Skin infections: Any open wound or infected lesion that could spread in the closed environment

- Allergic reactions or medication side effects: Anything that impairs judgment or physical capability

- Injury or musculoskeletal problems: Sprains, fractures, or strains that limit mobility

Daily medical checks during quarantine serve as an early warning system. Medical staff take temperatures, ask detailed symptom questions, and observe the astronauts for signs of illness. If anyone shows symptoms of infection, especially within 72 hours of launch, NASA faces a critical decision.

Launch or delay?

Delaying a launch is costly. The SLS rocket requires careful fueling procedures. The launch facility ties up resources. But launching with a compromised crew member is riskier. NASA has historically chosen to delay rather than risk mission safety. In early 2024, NASA postponed an ISS resupply mission for the first time in years due to a medical emergency with one of the crew members.

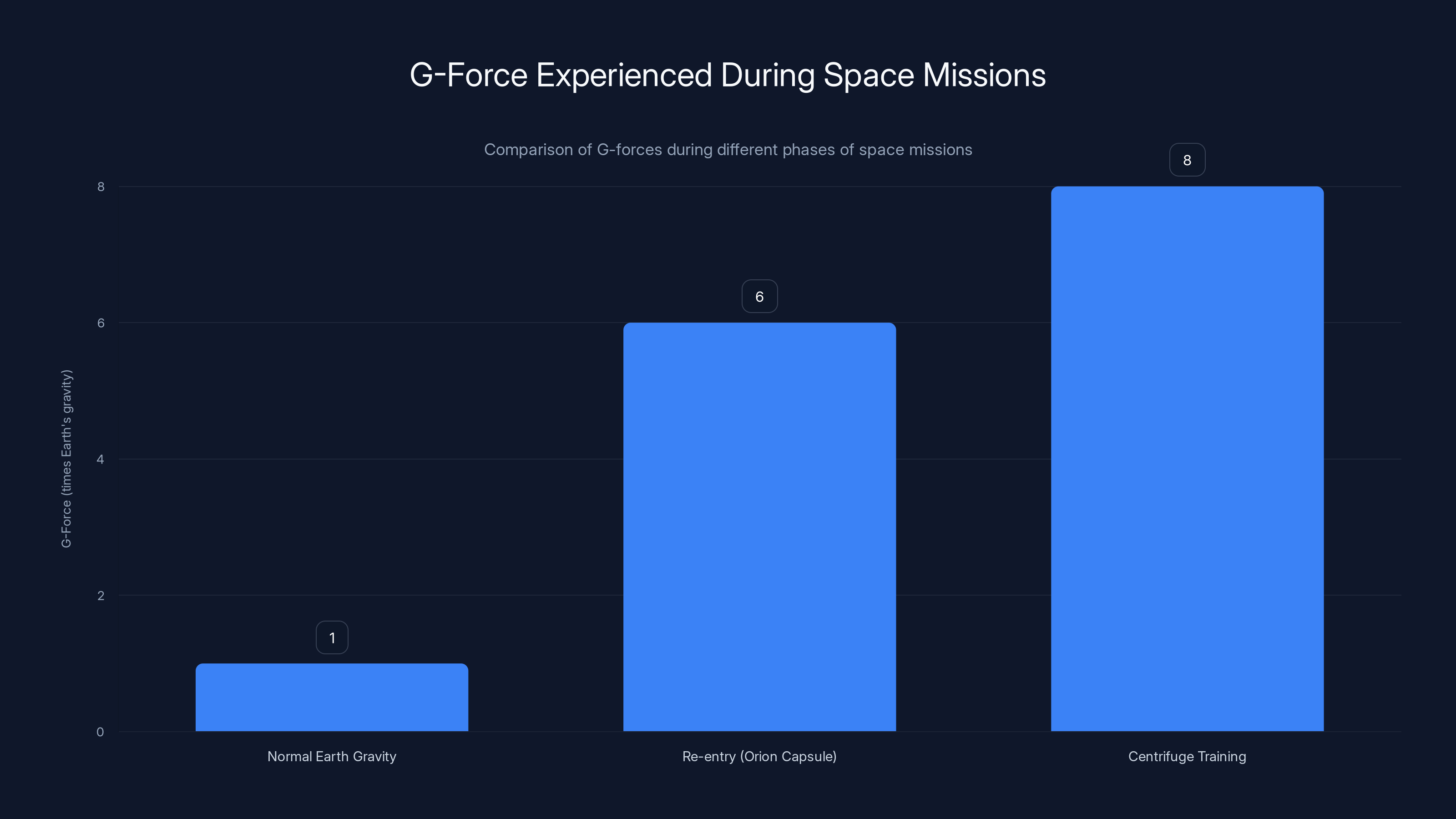

Re-entry subjects astronauts to 6 G's, a significant physical challenge compared to normal Earth gravity and centrifuge training. Estimated data.

The Quarantine Experience: What Astronauts Actually Do

Quarantine isn't solitary confinement. The crew lives together in a facility designed specifically for this purpose, and they have activities, training, and some flexibility.

During quarantine, the Artemis II crew continues mission preparation. They review procedures, go through simulations, study their instruments, and rehearse emergency protocols. They maintain physical fitness through exercise equipment available in the quarantine facility (though contact sports are forbidden). They participate in psychological evaluations and team-building activities designed to ensure mission cohesion.

They also have access to communication with families, though in controlled ways. Video calls are permitted. Family members can visit, but only from behind glass or maintaining physical distance. It's isolating without being completely disconnected from loved ones.

The mental component of quarantine is underestimated. Astronauts are extraordinary people, but they're still human. Fourteen days of enforced isolation, knowing the entire world is watching your preparation, knowing that getting sick could end your chance at a lifetime dream—that's psychological pressure. NASA provides counseling and support during this period to ensure the crew maintains mental resilience alongside physical health.

The facility itself—located in Houston where NASA's Johnson Space Center is headquartered—includes communication systems, training equipment, sleeping quarters, dining facilities, and medical areas. It's not a prison. It's a controlled environment designed to support mission preparation while minimizing disease exposure.

Historical Context: Apollo-Era Quarantine and How It Evolved

When NASA first implemented quarantine protocols in 1969, they were making educated guesses about what might be necessary. The Lunar Module would touch down on terrain humanity had never visited. The astronauts would collect samples of lunar material. They would return with those samples, and nobody knew what those samples might contain.

Apollo 11 astronauts spent 21 days in quarantine after returning from the Moon. So did the Apollo 12 crew. By Apollo 14, after examining numerous lunar samples and finding no evidence of extraterrestrial life or dangerous microorganisms, NASA felt confident reducing the quarantine period. By later Apollo missions, the post-lunar quarantine was eliminated entirely.

But the pre-launch quarantine remained.

Why? Because the logic behind it never changed. A healthy crew is essential for mission success. Illness in space is dangerous. Prevention is always better than treatment when you're millions of miles from medical facilities.

Modern quarantine protocols differ from Apollo-era versions in important ways. Medical monitoring is more sophisticated. Temperature readings, blood pressure checks, and symptom screening happen daily rather than periodically. Air filtration systems are more advanced. Isolation facility design incorporates lessons from decades of spaceflight experience and infectious disease prevention.

The psychological support available to crews during quarantine has also evolved. Apollo astronauts endured isolation with less understanding of its psychological impact. Modern crews have access to counseling, family communication systems, and activities designed specifically to maintain mental health during this stressful period.

Risks of Launch with a Compromised Crew: The NASA Decision Matrix

What happens if an astronaut develops symptoms the day before launch?

NASA faces a calculated decision based on a framework developed through decades of spaceflight experience. The agency weighs several factors:

Severity of symptoms: A minor scratchy throat might be manageable. A fever over 101 degrees is not.

Type of illness: A bacterial infection that could worsen in space is different from a viral infection that might resolve naturally.

Crew member role: Some roles are more critical than others for mission success, though NASA designs missions with redundancy to account for reduced crew capability.

Launch window: Is another launch window available soon, or is the next opportunity months away?

Mission criticality: Is this a routine resupply mission or a historic first-crewed lunar return in 50+ years?

For Artemis II, the stakes are extraordinarily high. This is the first crewed lunar mission since 1972. It's a test of systems that will eventually support sustained lunar exploration. It carries international prestige—a Canadian astronaut is part of the crew. Delaying it has enormous ripple effects across the entire Artemis program.

But NASA has consistently chosen to delay rather than risk crew safety. That's not just policy; it's institutional culture. The agency understands that launching with a compromised crew doesn't save time—it potentially creates disaster that sets the program back years.

This timeline illustrates the relationship between quarantine start dates and potential launch dates for Artemis II. Quarantine begins 14 days before the planned launch, with flexibility for delays. Estimated data.

The Psychological Impact: Living in Controlled Isolation Before Launch

Quarantine is physically straightforward to describe but psychologically complex to endure.

These four astronauts have trained for years. They've sacrificed enormously—relationships strained by years of preparation, families moved to Houston, personal lives subordinated to mission requirements. They're days away from achieving a dream that defines their careers. And now they're confined to a facility, unable to hug their spouse, unable to take a walk outside, unable to engage in normal human social behavior.

The psychological literature on isolation is clear: fourteen days is manageable but not trivial. Humans are social creatures. Extended isolation, even in relatively comfortable conditions, creates stress, mood changes, and cognitive impacts. Add the high stakes of their situation, and you've created a genuinely challenging environment.

NASA addresses this with psychological support during quarantine. Astronauts have access to counselors trained in pre-flight stress management. They receive regular briefings about what to expect psychologically. They're encouraged to maintain routines, exercise, engage in hobbies, and maintain family contact within the protocols.

Interestingly, quarantine also serves as a psychological test. It reveals how well the crew works together under stress and confinement. Some of that evaluation feeds into final assessments about crew readiness.

International Cooperation: The Canadian Space Agency Connection

Jeremy Hansen, representing the Canadian Space Agency as part of the Artemis II crew, brings interesting dimensions to the quarantine and mission.

International space missions involve coordination between agencies with different protocols, standards, and communication structures. The Artemis program, while NASA-led, involves international partners including the Canadian Space Agency, ESA, and others. Coordination during quarantine requires ensuring that all crew members follow the same health protocols regardless of which agency employs them.

Hansen's inclusion in Artemis II marks a significant moment: the first non-American astronaut to travel beyond Earth orbit in decades. That international dimension adds diplomatic and political significance to the mission, making mission success—and therefore crew health—even more critical.

Equipment Sterilization: Planetary Protection Beyond the Crew

While the crew undergoes Health Stabilization Protocol, the Orion spacecraft and all equipment designated for lunar surface contact undergo their own sterilization procedures.

NASA maintains planetary protection standards that govern what can be brought into contact with the lunar surface. Equipment is cleaned according to strict protocols. Spacesuits are disinfected. Tools and scientific instruments are sanitized. The goal is to minimize the potential for Earth microorganisms to contaminate the lunar environment, particularly those pristine south pole regions.

This sterilization process is separate from crew quarantine but complementary. You might have a perfectly healthy crew boarding a spacecraft that contains equipment properly sterilized according to planetary protection standards. Together, these measures minimize contamination risk.

The sterilization process is labor-intensive and time-consuming. Equipment must be cleaned without damaging delicate instruments. Materials must be selected to survive sterilization while remaining functional. It's a meticulous process that extends the preparation timeline for lunar missions.

Estimated data shows fever and respiratory symptoms as the most severe disqualifications for astronauts, highlighting the critical nature of infection control.

Mission Duration and Re-entry: Why Health Matters Throughout

The Artemis II mission timeline spans approximately 10 days from launch through splashdown. But the health risks don't end when the spacecraft lifts off.

Re-entry is one of the most physically demanding portions of spaceflight. The Orion capsule experiences extreme deceleration as it enters Earth's atmosphere—forces exceeding 6 G's (six times Earth's gravity). For comparison, astronauts in training experience about 8 G's in centrifuge training, but that's brief and controlled. A re-entry force of 6 G's sustained for minutes is physically demanding.

If a crew member is weakened by illness, dehydrated, or cognitively impaired, handling those forces becomes more dangerous. Recovery from re-entry—the physical toll, the sensory adjustment, the potential nausea—is harder for someone already fighting infection.

This is why the quarantine extends pre-launch rather than attempting post-mission quarantine. By the time the mission launches, ensuring the crew is as healthy as possible has already been maximized.

Artemis II's Role in Lunar Exploration: Stakes and Timeline

Artemis II isn't just another space mission. It's the gateway to sustained lunar exploration and eventual human missions to Mars.

The Artemis program aims to establish a human presence on the Moon, eventually building bases that support long-term research and exploration. Artemis II circles the Moon, tests systems, and validates procedures. Artemis III will land astronauts on the lunar surface, specifically targeting those south pole regions with water ice.

Each mission builds on previous missions. If Artemis II experiences problems—mechanical failures, crew health crises, navigation issues—those problems inform what needs to be fixed before Artemis III. A successful Artemis II means confidence in the systems and procedures that Artemis III will depend on.

The timeline matters. NASA set the original February 2026 window, then moved to March 2026. If delays keep accumulating, the entire Artemis schedule shifts. Lunar research timelines extend. Mars missions slip further into the future. The quarantine protocol, while it might seem like a small bureaucratic step, is actually a critical gate in a program that defines human spaceflight for the next decade.

Contingency Planning: What Happens If Launch Gets Delayed

NASA doesn't enter quarantine blindly. The agency has contingency plans for multiple scenarios.

If a crew member develops illness within 72 hours of launch, launch is postponed. A new launch date is selected, and the quarantine clock resets. The crew exits quarantine, receives medical treatment if needed, and re-enters isolation 14 days before the new launch date.

If weather prevents launch (which happens frequently in Florida), the crew remains in quarantine if the delay is brief (typically less than 48 hours). If the delay extends longer, they exit quarantine and return to normal activities, then re-enter quarantine for the new launch date.

Multiple launch windows exist within the March 2026 window, providing flexibility. If March 6 isn't feasible, March 8 or March 10 might be viable. This flexibility is built into mission planning specifically to provide options if health or weather issues arise.

For a mission as significant as Artemis II, NASA can afford to delay. The resources, the international partnerships, the scientific objectives—none of them disappear if launch slips by weeks. What can't be afforded is launching with inadequately healthy crew or inadequately prepared equipment.

Future of Quarantine: Could It Change for Mars Missions?

As human spaceflight extends further—to the Moon for extended stays, eventually to Mars—quarantine protocols may evolve.

A Mars mission involves six-month flight durations each way, plus two-year surface missions. Fourteen days of pre-launch quarantine becomes negligible compared to the isolation astronauts will endure in transit and on the Martian surface. Future protocols might be more relaxed pre-launch but more intensive during the multi-year mission itself.

The underlying principle remains unchanged: healthy crew equals successful mission. But as missions extend in duration and distance, the mechanisms for maintaining crew health will necessarily evolve. Medical care in deep space, preventive health protocols during multi-year missions, and psychological support systems will all become more sophisticated.

Artemis II's quarantine protocol isn't just protecting a single mission. It's validating approaches and testing systems that will inform how humanity manages health during much longer, much more challenging deep space endeavors.

FAQ

What is the Health Stabilization Program?

The Health Stabilization Program is NASA's mandatory pre-launch quarantine protocol requiring astronauts to isolate for 14 consecutive days before spaceflight. During this period, crew members undergo daily medical screening, maintain physical distance from others, wear masks in necessary situations, and avoid public places. The program aims to prevent illness from compromising mission safety and success, particularly for long-duration or distant missions like Artemis II.

How does NASA decide whether to launch if an astronaut is sick?

NASA evaluates multiple factors including symptom severity, illness type, which crew member is affected, launch window availability, and mission criticality. The agency has consistently chosen to delay rather than risk crew safety. A fever over 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit or any respiratory symptoms typically result in launch postponement. NASA maintains multiple launch windows specifically to accommodate health-related delays.

Why is the Orion spacecraft so small if the crew will live in it for 10 days?

The Orion spacecraft is engineered for efficiency and performance in the extreme environment of space, not comfort. The compact design minimizes weight, reduces fuel requirements, and ensures all critical systems fit within the vehicle. For a 10-day mission, the crew can manage the confined space, though it remains a significant physical and psychological challenge during missions of longer duration.

What happens to the Orion spacecraft during quarantine?

While the crew undergoes Health Stabilization Protocol, the Orion spacecraft and all equipment designated for lunar surface contact undergo separate sterilization procedures. These processes follow NASA's planetary protection standards designed to minimize contamination of the lunar environment, particularly pristine south pole regions that could harbor important scientific information.

Can family members visit astronauts during quarantine?

Family members can visit during quarantine, but only with physical distancing measures in place—typically behind glass or maintaining at least six feet of distance. Video calls are permitted, allowing astronauts to maintain emotional connection with loved ones while minimizing infection transmission risk. The facility in Houston where quarantine occurs is equipped with communication systems and visitation areas designed for this purpose.

Why is the Moon's south pole region scientifically important?

The Moon's south pole contains permanently shadowed craters where temperatures remain below negative 370 degrees Fahrenheit. These regions contain water ice and represent scientifically pristine environments holding geological records from the Moon's early formation and the solar system's origins. Protecting these areas from Earth microorganism contamination ensures they remain available for future scientific study and analysis.

How often has NASA postponed launches due to crew health issues?

Launch postponements due to crew health are rare but do occur. In early 2024, NASA postponed an ISS resupply mission for the first time in years due to a medical emergency with a crew member. The rarity of such postponements reflects the effectiveness of pre-flight medical screening and the astronaut selection process, though NASA maintains willingness to delay when necessary to ensure crew safety.

What is the psychological impact of 14-day quarantine on astronauts?

Quarantine creates measurable psychological stress through isolation, social deprivation, and awareness of high-stakes mission responsibility. Research on isolation indicates 14 days is manageable but not trivial for most people. NASA addresses this with psychological support including counseling, family communication, structured activities, and exercise opportunities. The quarantine also serves as an assessment period to evaluate how crew members handle stress and confinement together.

Does international crew participation affect quarantine protocols?

International crew members like Jeremy Hansen from the Canadian Space Agency follow the same Health Stabilization Protocol as NASA astronauts. International partnerships require coordination between space agencies to ensure standardized health protocols. This coordination adds complexity but reflects the reality that modern human spaceflight increasingly involves multinational teams with shared mission objectives and safety standards.

Will future deep space missions require quarantine protocols?

The underlying principles of health stabilization will likely persist for future deep space missions to Mars and beyond. However, quarantine mechanics may evolve. Pre-launch quarantine might become brief compared to in-flight health protocols during multi-year missions. The focus may shift from 14-day pre-launch isolation to longer-duration health management systems addressing the challenges of six-month transit periods and multi-year surface exploration.

The Bottom Line: Why 14 Days of Isolation Actually Matters

Two weeks in quarantine doesn't sound like much. It's less time than a vacation. It's a fraction of the preparation astronauts undergo to qualify for spaceflight.

But those two weeks exist at the boundary between preparation and execution. Everything before quarantine is training, refinement, and practice. Everything after quarantine is commitment. The four Artemis II astronauts, living in controlled isolation at a Houston facility, are essentially at the final gate before attempting something humanity hasn't done in more than 50 years.

The quarantine protects them. It protects the mission. It protects an entire celestial body from potential contamination. And it reflects a fundamental truth about spaceflight: success depends on relentless attention to details that seem small until they matter enormously.

When Artemis II launches in March 2026, carrying its crew toward lunar orbit, that flight will succeed or fail partly because of decisions made thousands of times by thousands of people. The quarantine represents one of those decisions: the commitment to ensuring crew health at every stage of the mission.

There's no glamour in isolation. There's no excitement in daily temperature readings and masked conversations with family members through glass barriers. But those unsexy, meticulous details form the foundation of missions that push humanity forward. That's the real story of the Artemis II quarantine.

It's boring. It's essential. And that's exactly how NASA likes it.

Key Takeaways

- NASA's Health Stabilization Program requires 14 consecutive days of pre-launch isolation to prevent illness from compromising mission safety

- The Artemis II crew lives in spacecraft roughly the size of two minivans for 10 days, making crew health absolutely critical for mission success

- Planetary protection standards require sterilization of crew and equipment to prevent Earth microorganisms from contaminating pristine lunar south pole regions

- Launch postponement is preferable to health risks; NASA maintains multiple launch windows to accommodate crew medical issues or bad weather

- Quarantine protocols established during Apollo era have evolved with modern medical monitoring but remain fundamentally unchanged in principle

![Artemis II Crew Quarantine: Why Astronauts Must Isolate Before Moon [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/artemis-ii-crew-quarantine-why-astronauts-must-isolate-befor/image-1-1770379689045.jpg)