The Last Big Test Before Humans Head Back to the Moon

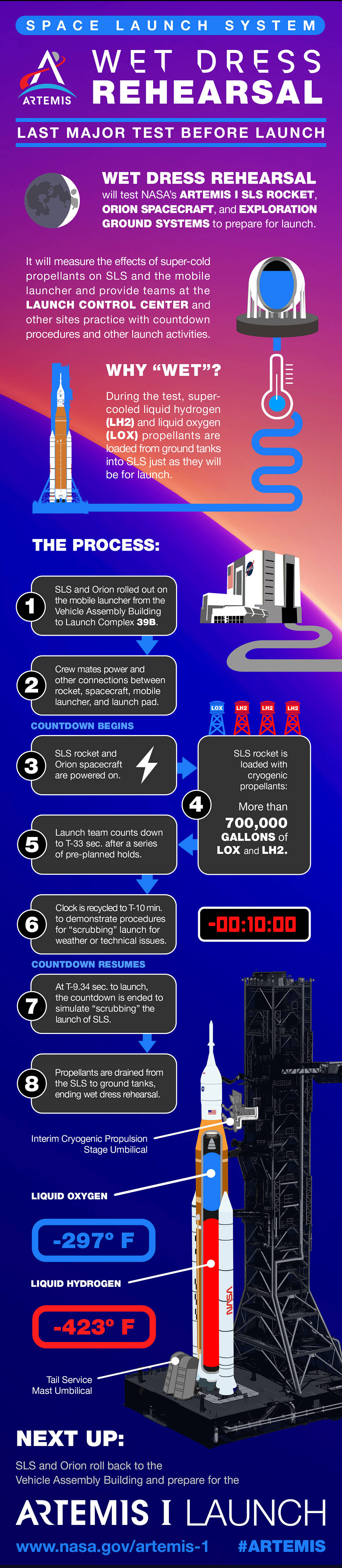

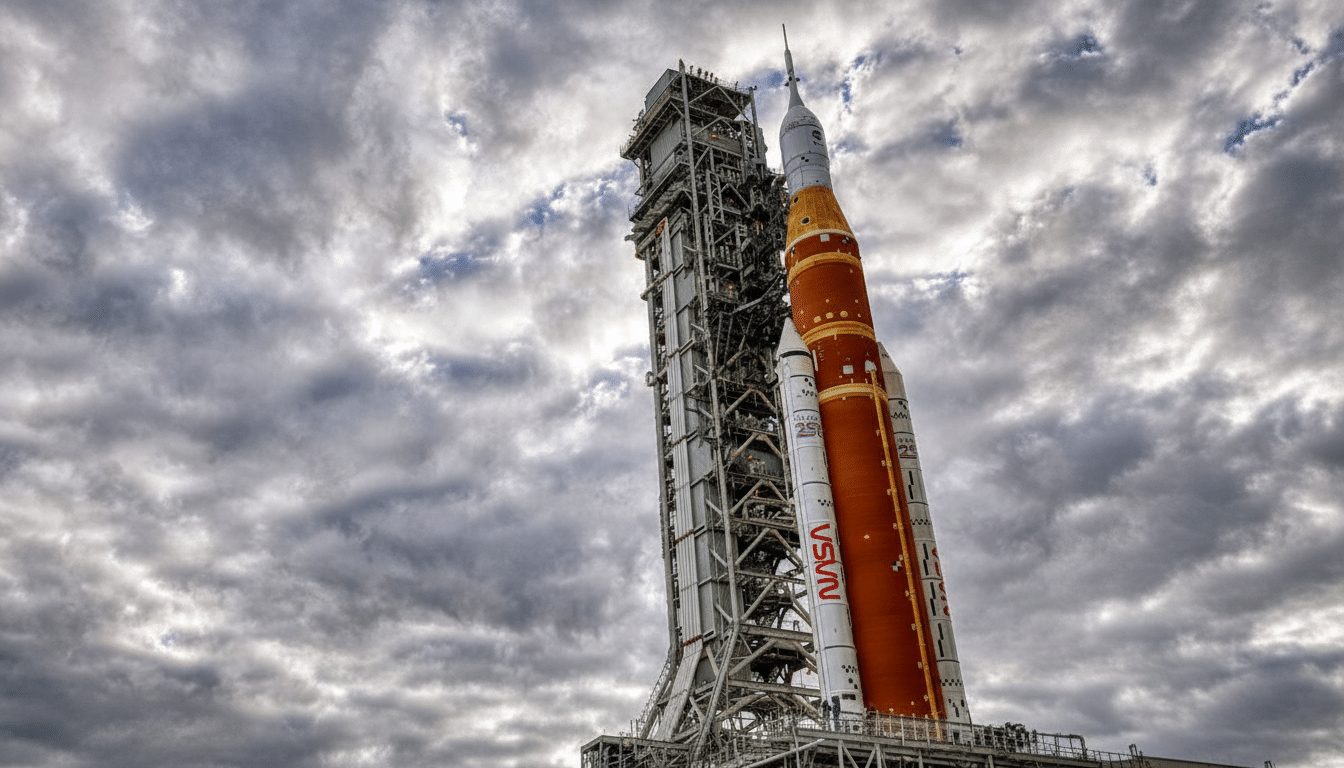

NASA's about to run one of the most consequential dress rehearsals in decades. On Monday, engineers at Kennedy Space Center will load 755,000 gallons of super-cold propellants into the Space Launch System rocket, simulating an actual launch countdown. This isn't a casual test. This is the final check before NASA sends four astronauts farther from Earth than any humans have traveled in more than half a century, as detailed in NASA's mission overview.

The Artemis II mission represents something genuinely historic. These astronauts will launch on the most powerful rocket NASA has ever built, swing around the far side of the Moon, and return home. It's been 53 years since humans last ventured to the lunar vicinity. The next few days will determine whether that happens in February or gets pushed back again.

Here's the reality: space programs live or die by their ability to execute flawlessly under pressure. The Wet Dress Rehearsal, or WDR as NASA calls it, is where that rubber hits the road. Everything that could go wrong in a real countdown gets stress-tested beforehand. Loading propellants, cycling systems, managing pressure, venting gases, routing power, checking communications. All of it happens here, with astronauts conspicuously absent but every other system running hot.

The stakes feel enormous because they are. Miss February's launch windows, and NASA doesn't get another shot until March 6. Miss that, and the timeline slips further. The Artemis program has already absorbed years of delays. Hardware testing takes longer than expected. Hardware itself needs redesign. Budget constraints force reprioritization. Every month matters now.

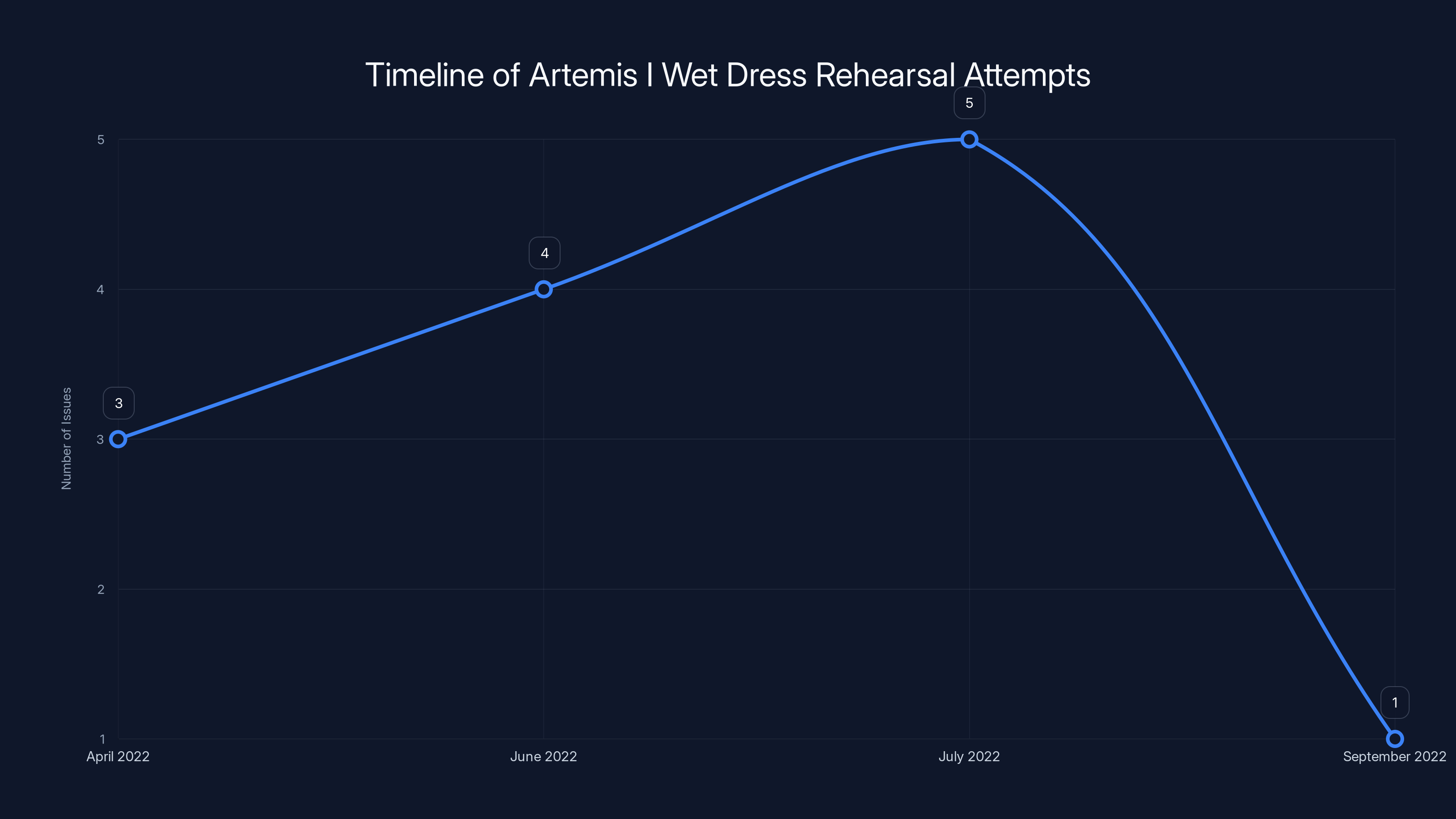

But the real tension isn't about timelines or budgets. It's about whether NASA has actually learned from Artemis I. The first test flight, in 2022, required four separate attempts just to load propellants. Engineers fought with liquid hydrogen leaks, seal failures, temperature problems, and systems that refused to cooperate. Getting a rocket to hold super-cold fuel at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit without springing leaks is harder than it sounds. Much harder.

The question now is simple: has NASA fixed those problems? The answer determines everything about what happens next.

Understanding the Wet Dress Rehearsal: Why It Matters

The term "wet dress rehearsal" comes from its core purpose. "Wet" means propellants are flowing. It's not a simulation or a test from a control room. Real fuel enters real tanks. Real pressure builds. Real systems cycle. Everything that would happen on launch day happens now, except the engines don't ignite.

Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, NASA's launch director for Artemis II, called this "the best risk reduction test" available. She wasn't overstating it. You can run computer simulations all day. You can test individual components in labs. You can review procedures endlessly. But nothing substitutes for putting thousands of gallons of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen into a rocket and seeing what actually happens.

The WDR serves multiple critical functions. First, it validates that all ground systems work correctly. The fueling lines, the cooling systems, the pressure regulators, the valves, the sensors, the computers running the show. Second, it confirms that the Space Launch System rocket itself tolerates the loading process without unexpected problems. Third, it gives engineers a chance to identify issues before they become disasters on launch day. Fourth, it proves the team can execute a full countdown under realistic stress.

There's also a psychological component. Countdowns are complex orchestrations involving hundreds of people making thousands of decisions over many hours. People get tired. Communication breaks down. Mistakes happen. Running a full WDR lets the team practice being tired and still executing flawlessly.

NASA originally scheduled the WDR for earlier in the week, but delayed it by two days. The reason wasn't technical. Central Florida experienced unusually cold weather, and launch vehicle cold weather restrictions would have been violated. The team wanted to rehearse under conditions closer to what they might actually see on launch day. This decision reveals something important about modern NASA culture. They're not chasing calendar dates at the expense of realistic preparation.

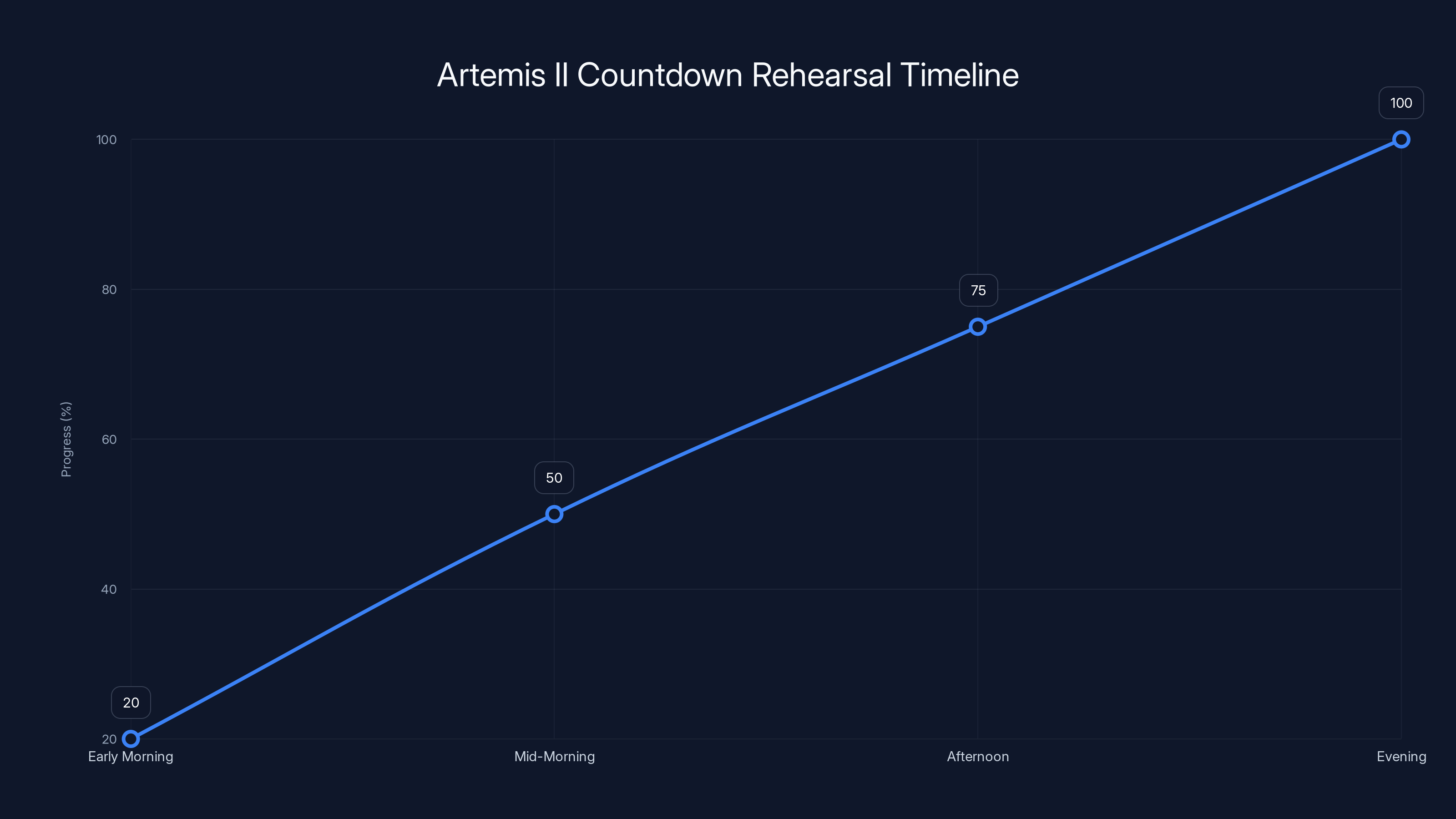

The rehearsal officially started Saturday night with the initiation of a two-day countdown clock. But the critical work happens Monday. That's when fuel loading begins. That's when systems get tested under full stress. That's when the team discovers whether last year's lessons stuck.

Estimated data showing the progression of events during Monday's rehearsal, from early morning preparations to evening conclusion.

The Hydrogen Problem: Why Liquid Hydrogen Is a Nightmare

If there's one technical challenge that haunted Artemis I and could haunt Artemis II, it's hydrogen. Not the element itself, but the liquid form of it. Liquid hydrogen is extraordinarily useful for rockets. It packs enormous energy into a lightweight package. The Space Launch System's core stage uses 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen as fuel. That's nearly 72,000 pounds of hydrogen in liquid form.

The catch? Hydrogen is notoriously difficult to contain. The molecule is tiny. Its mass is almost nothing. At normal temperatures, hydrogen gas wants to escape anywhere there's even a microscopic gap. But at cryogenic temperatures, liquid hydrogen creates even worse problems.

Think about what happens when you cool something to minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit. Materials don't just get cold. They contract. Seals and gaskets that fit perfectly at room temperature shrink. Gaps form. But that's only half the problem. When liquid hydrogen touches those seals and gaskets, it causes thermal shock. The material changes shape even more. Rubber gaskets that sealed perfectly suddenly have leak paths. The liquid hydrogen escapes, and the system pressure drops.

Here's where it gets worse. At ambient temperatures, those leak paths close again as the gasket returns to normal size. So engineers can't even detect the problem by ground-testing the system at normal temperatures. The leaks only appear when cryogenic fuel is actually flowing. This reality played out repeatedly during Artemis I's rehearsals.

Engineers documented hydrogen leaks in the fueling line between the Space Launch System's core stage and the ground launch platform. Not just one leak. Multiple leaks. Persistent leaks. Leaks that appeared and disappeared. Leaks that violated launch safety protocols. Engineers would attempt to fix one leak, only to have another appear. They'd load fuel, pressure would build, new leaks would develop. They'd drain fuel, gaskets would warm up, leaks would vanish.

The problem got so bad it nearly prevented Artemis I from launching. The mission slipped from August 2022 to September 2022 to October 2022. Engineers couldn't figure out how to keep hydrogen in the rocket. Every attempt to load propellants ended in frustration and another round of troubleshooting.

Finally, someone had a different idea. Instead of ramping up pressure aggressively, what if NASA reduced pressure more slowly? What if fuel flow rates increased gradually rather than all at once? What if the entire process moved at a gentler pace? The team devised what they called the "kinder, gentler" approach to fueling the Space Launch System.

The revised procedure wasn't elegant. It wasn't faster. It added time to the fueling timeline. But it worked. By reducing thermal shock to seals and gaskets, by letting materials adjust gradually to temperature changes, by not forcing the system to transition too quickly from one state to another, engineers finally got hydrogen to stay in the rocket. Artemis I finally launched in November 2022.

The question now: will the same procedure work for Artemis II? NASA is betting it will. They'll use identical fueling procedures. But there's no guarantee. Hardware is never identical. Fuel from different batches might behave slightly differently. New gaskets might have slightly different properties. Temperature on the launch pad might be different. Success is never certain, which is exactly why the WDR matters so much.

The Artemis I Wet Dress Rehearsals faced increasing issues from April to July 2022, with a successful attempt in September after addressing key problems.

The Countdown Timeline: What Happens Monday

The WDR doesn't just load fuel and shut everything down. It's a full rehearsal of everything that happens between when the countdown clock starts and the moment ignition occurs. On launch day, the actual countdown for Artemis II will span many hours. Monday's rehearsal will follow the same schedule.

The two-day countdown officially began Saturday night. Early Sunday involved preparation work. Engineers inspected equipment, ran system checks, verified that everything needed for the fueling process was ready and in position. They loaded consumables, checked power systems, verified launch control systems were operational. Most of this work happens behind the scenes, invisible to public watching the mission.

Monday morning is when things get real. The countdown clock reaches the fueling operations window. Launch pad teams begin activating systems. Ground support equipment starts cycling. Tanker trucks full of liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen position themselves near the launch pad. Crews don safety gear. Communication systems activate. The firing room at Launch Control Center goes to full staffing.

The actual fuel loading typically begins around mid-morning and extends into the afternoon. Liquid oxygen flows first. Then liquid hydrogen. Pressure builds gradually in the tanks. Sensors everywhere monitor temperatures, pressures, flow rates, and tank levels. Any anomaly triggers immediate investigation. If problems develop, teams pause operations, diagnose the issue, and determine whether to continue or drain the tanks and try again.

The timeline for a complete WDR typically extends into Monday evening or night. It's mentally exhausting work. People stare at screens. They monitor data streams. They communicate constantly. They make decisions. They deal with problems when they emerge. By the time the rehearsal concludes, the team has lived through what amounted to a full launch day.

A successful WDR means more than just loading fuel and surviving. It means loading fuel smoothly. It means no major anomalies or leaks. It means systems performing as designed. It means the team executing flawlessly under stress. If the rehearsal goes well, Blackwell-Thompson and her team gain confidence that launch is achievable.

If the WDR encounters significant problems, the implications ripple outward. NASA has only limited launch opportunities each month where orbital mechanics, weather, and scheduling align for an Artemis II launch attempt. Those opportunities are February 8, 10, and 11. If Monday's rehearsal fails, or encounters major problems that require extensive troubleshooting, NASA likely misses all three dates. That pushes the next opportunity to March 6.

The Artemis I Lessons: What Went Wrong Before

Understanding why this rehearsal matters requires understanding what happened in 2022. Artemis I was supposed to launch in August. It didn't. The Wet Dress Rehearsal became the bottleneck. Engineers couldn't load propellants without encountering problems.

The first WDR attempt in April 2022 revealed issues with the mobile launcher platform. Gaseous nitrogen supply systems—used to pressurize tanks and push propellants—malfunctioned. The problems were tractable but time-consuming to fix. NASA drained the tanks, made repairs, and scheduled another attempt.

The second attempt in June encountered different problems. Liquid oxygen proved difficult to keep at the proper temperature. Sensors recorded unexpected temperature variations. Engineers questioned whether the insulation on fuel lines was adequate. Questions multiplied about whether temperature management systems designed on paper would actually work under real conditions. Another drain. Another round of troubleshooting.

The third attempt in July encountered the hydrogen seal problems described earlier. Leaks in the fueling line. Pressure anomalies. Valve issues. Engineers focused intensely on the hydrogen pathway. They tested seals separately. They investigated gasket properties. They debated whether existing components were adequate or required replacement. The problems seemed to multiply the more engineers investigated.

By this point, August's launch window had passed. September arrived. NASA scheduled another WDR attempt for September 2022. This fourth attempt finally succeeded in loading propellants relatively smoothly. Hardware was ready. Teams were prepared. Lessons from three previous attempts had been integrated into procedures. And most critically, NASA had time to implement the "kinder, gentler" fueling approach that addressed the root cause of hydrogen leaks.

Artermis I finally launched on November 16, 2022, more than three months behind its original schedule. The mission succeeded, establishing proof of concept for the Space Launch System and the Orion spacecraft. But the painful WDR campaign left scars. Engineers and managers understood viscerally that propellant loading on this rocket was a bottleneck that could threaten any future mission.

NASA learned hard lessons from Artemis I. The revised fueling procedure is one. But there were others. Engineers learned which sensors were most critical to monitor. They learned which communication protocols worked best under stress. They learned which team members performed best in specific roles. They learned where procedures needed clarification. Every issue from 2022 became a data point for 2025 planning.

But here's the critical point: past success is not guaranteed future success. New hardware might have different characteristics. Environmental conditions might be different. Fuel from different batches might behave differently. Cosmic ray hits could have degraded some component. The team isn't just repeating 2022. They're applying lessons from 2022 to a new situation with inherent uncertainties. That's why the WDR matters. That's why success Monday matters. That's why this final test is called the "best risk reduction test."

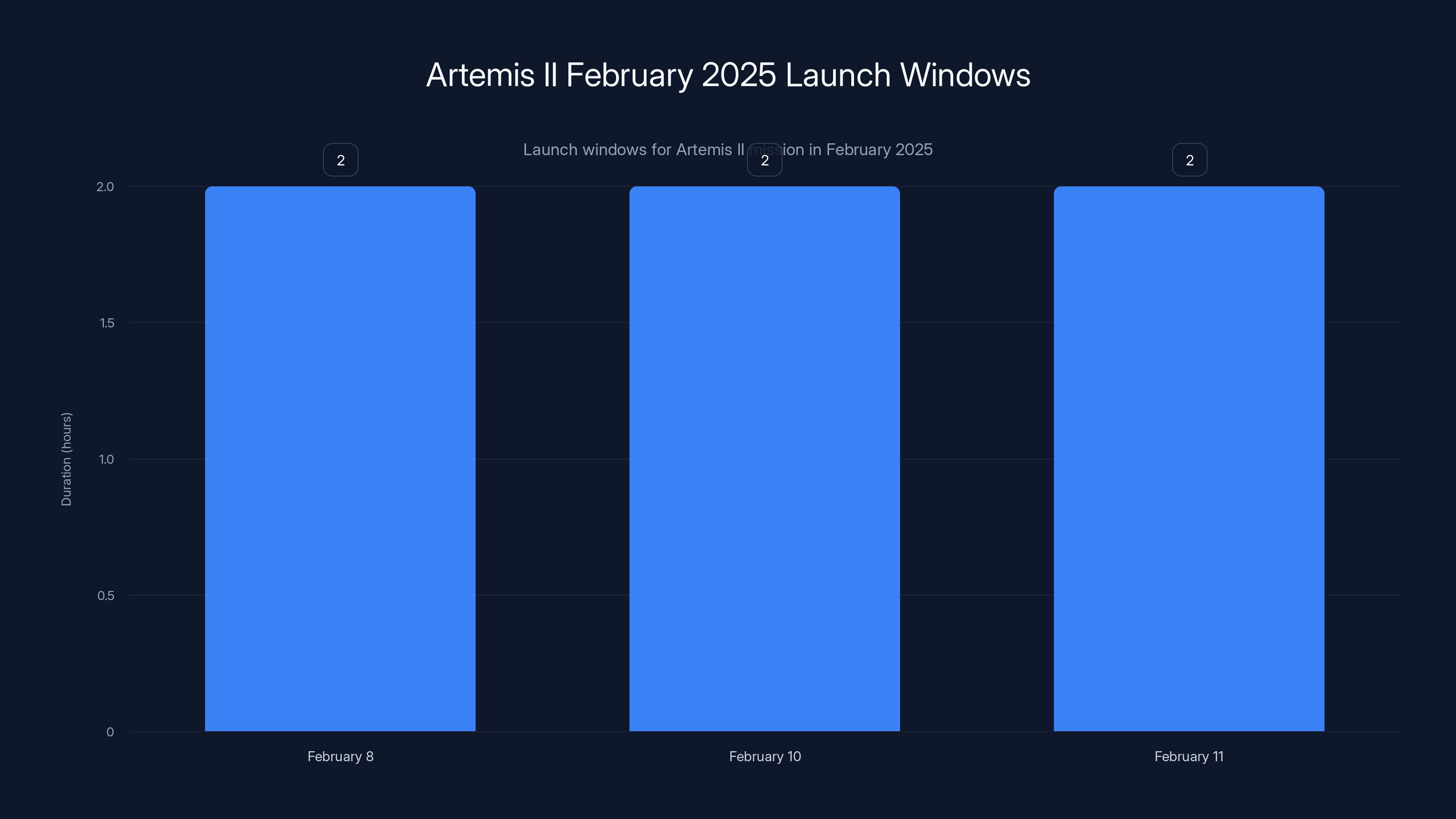

Artemis II has three two-hour launch windows in February 2025. If the WDR encounters issues, the next window is March 6, 2025.

The New Complication: Astronauts on the Rocket

Artermis I was unpiloted. The Orion spacecraft launched empty. No humans strapped into seats. No crew cabin that needed to be verified as safe. That simplified things, but it also meant the WDR didn't need to simulate the crew boarding procedure.

Artermis II changes that fundamentally. Four astronauts will actually fly this mission. They'll strap into the Orion spacecraft sitting atop the SLS rocket. But they won't board until after fueling is complete. They won't climb in through the access arm until the rocket is fully loaded with hydrogen and oxygen.

This creates a new wrinkle in the countdown. At some point during Monday's rehearsal, there's a built-in pause. Normally, the crew wouldn't be present. But the rehearsal includes a pause point where, on launch day, astronauts would leave the crew quarters, make their way to the launch pad, ride an elevator up the launch tower, and board the Orion spacecraft.

This pause is crucial to simulate accurately. It tests whether the planned timing works. It verifies that crew boarding procedures don't interfere with other countdown activities. It ensures that launch control systems handle crew transition smoothly. But it also introduces complexity that didn't exist in 2022. The countdown isn't just about loading fuel and running systems. It's about coordinating human activities in a live environment.

The fact that NASA incorporated crew boarding procedures into the WDR demonstrates maturation in mission planning. They're not just rehearsing propellant loading. They're rehearsing the entire mission operation from start to finish. Every element gets tested. Every contingency gets considered. Every procedure gets validated.

For the four astronauts who will eventually fly Artemis II, Monday's rehearsal is more than abstract preparation. Video feeds from the WDR will show them exactly what the launch pad looks like. They'll see the vehicle from the same angles they'll see it on launch day. They'll understand the timeline viscerally. They'll know what to expect when they actually show up to strap in for real.

The Launch Windows: What Happens If Monday Fails

NASA's scheduling for Artemis II is tightly constrained by orbital mechanics. You can't launch to the Moon on any arbitrary day. The Moon's position relative to Earth, combined with the Earth's orbit around the Sun and other factors, create launch opportunities. Miss one opportunity, and you wait for the next one.

February 2025 offers three launch windows where everything lines up for an Artemis II mission:

- February 8: Launch window opens at 11:20 pm EST, closes at 1:20 am EST (two-hour window)

- February 10: Launch window opens at 12:06 am EST, closes at 2:06 am EST (two-hour window)

- February 11: Launch window opens at 1:05 am EST, closes at 3:05 am EST (two-hour window)

Note that these are night launches. That's not accidental. Orbital mechanics dictate when launch windows occur. Artemis II couldn't launch during daylight even if NASA wanted to. February 8 and 9 were originally available before NASA delayed the WDR two days.

If the WDR succeeds without major problems, NASA could potentially launch as soon as February 8. That's the best-case scenario. The team would have confidence, hardware would be ready, and weather would need to cooperate. But that scenario is far from guaranteed.

More realistically, if the WDR goes smoothly, NASA might delay launch to February 10 or 11. That provides breathing room. It allows extra time for post-rehearsal inspections and data analysis. It reduces pressure on the launch team. Modern spaceflight generally favors caution over rushing.

If the WDR encounters problems that require minor troubleshooting, NASA might miss February 8 but still make February 10 or 11. The team would work overnight if necessary, diagnose issues, implement fixes, and be ready for launch within a few days.

But if the WDR encounters major problems requiring extensive troubleshooting, all three February windows vanish. The next available launch window is March 6, 2025. That's two weeks later. Missing February would be disappointing, but March 6 is achievable if Artemis II hardware doesn't require deep investigations.

NASA has published an extensive launch schedule showing available Artemis II windows through the end of April. Why so many options? Because the space agency learned hard lessons from earlier programs. Flexibility matters. If one window closes, you need alternatives. Backup dates provide insurance against unexpected problems.

Charlie Blackwell-Thompson's comment that "wet dress is the driver to launch" captured the priority perfectly. Monday's rehearsal is the critical decision point. Success unblocks February. Failure likely means March.

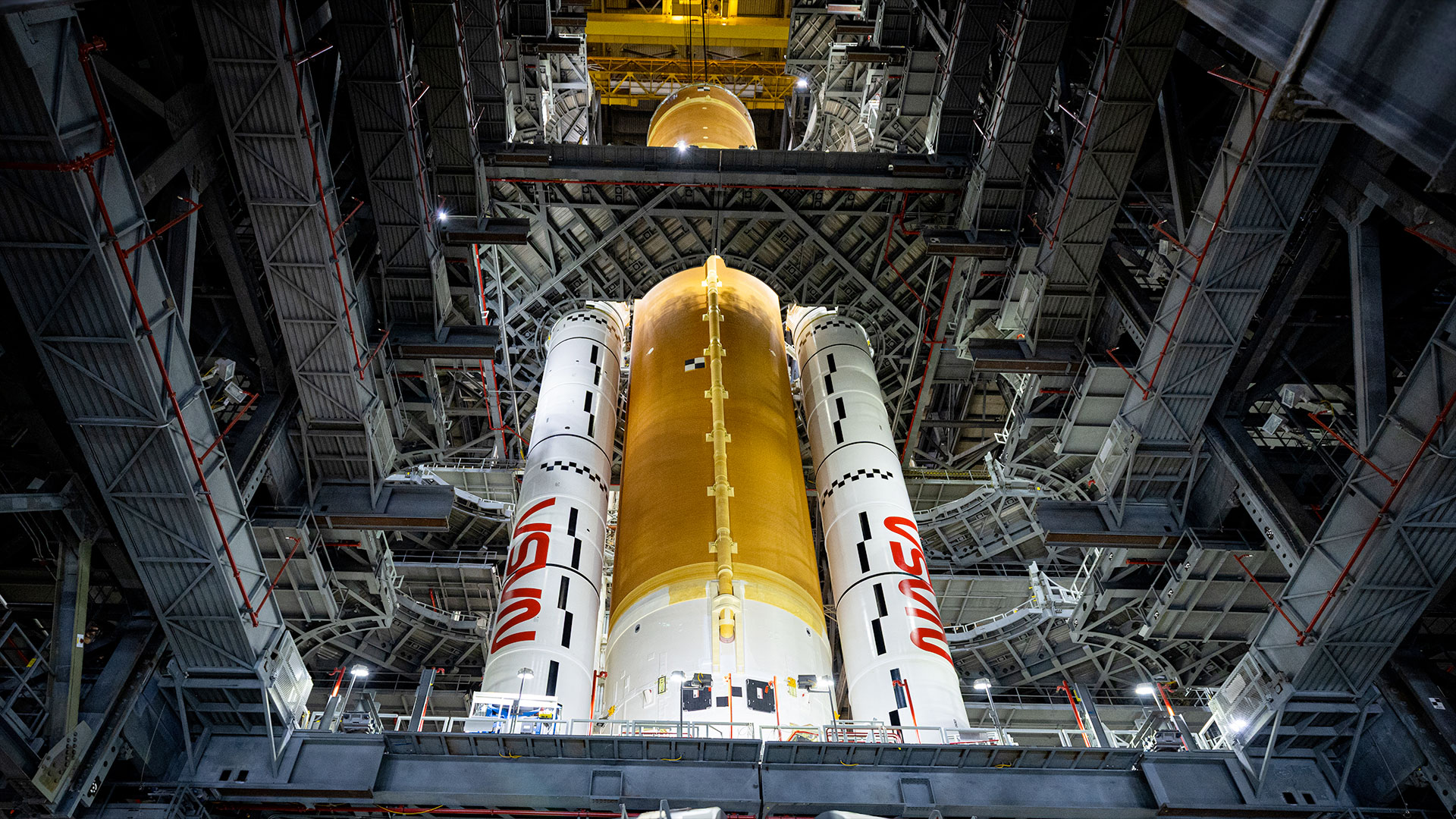

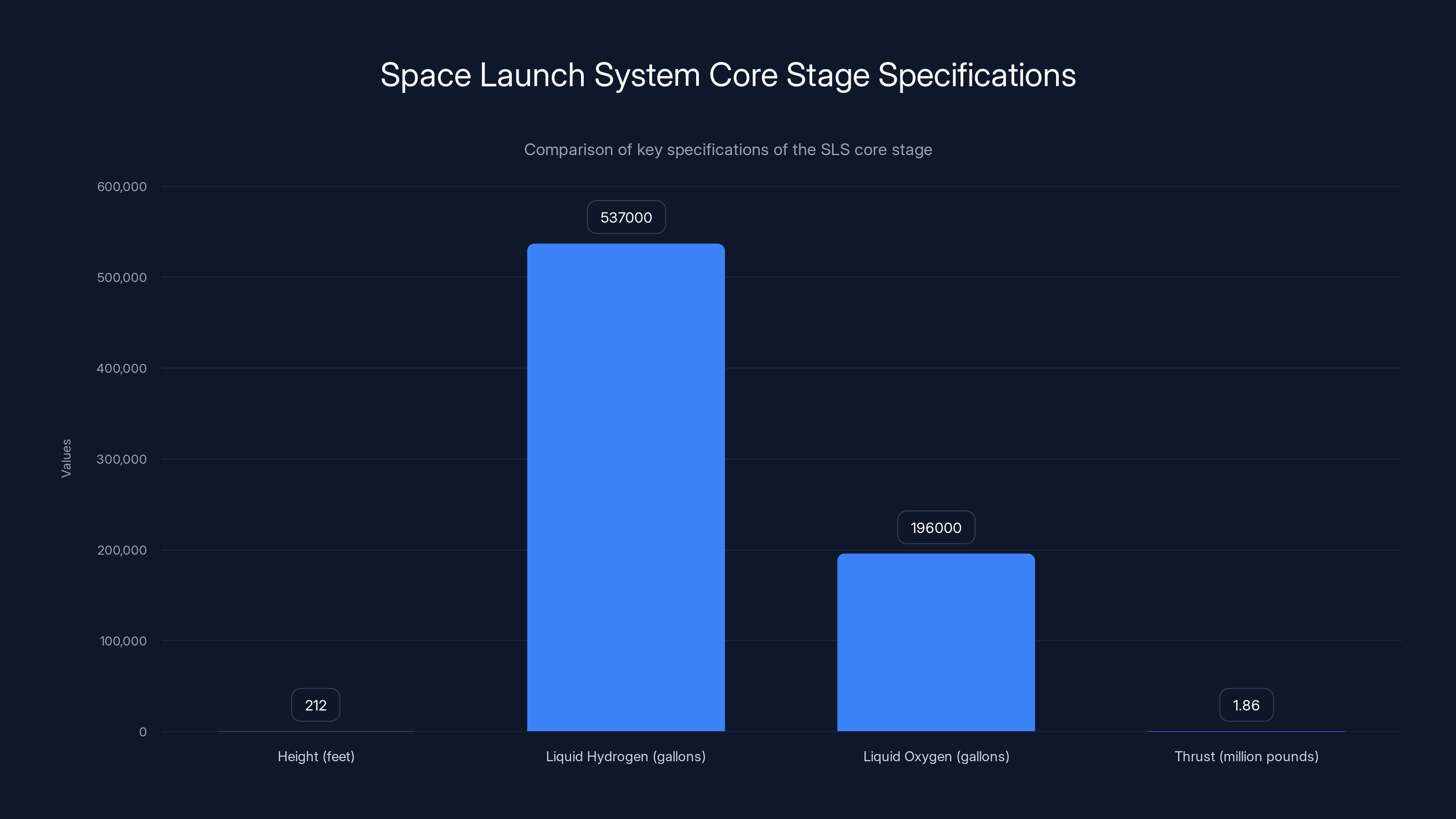

The Space Launch System's core stage is a massive structure, standing 212 feet tall and housing 755,000 gallons of fuel, producing 1.86 million pounds of thrust.

The Space Launch System: An Enormous, Complex Machine

To understand why the WDR is important, you need to understand the Space Launch System itself. This isn't just a bigger version of earlier rockets. It's a fundamentally new architecture designed to achieve capabilities no existing vehicle provides.

The SLS stands 322 feet tall. That's taller than the Statue of Liberty. The core stage alone is 212 feet from the bottom of the main engines to the top where the Orion spacecraft sits. This core stage burns 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen and 196,000 gallons of liquid oxygen. That's 755,000 gallons total. Roughly the volume of a medium-sized swimming pool.

The core stage houses the main engines, fuel tanks, avionics, and life support systems. Everything else is supplementary. The vehicle launches with solid rocket boosters strapped to the sides, but the real power comes from the core stage's RS-25 engines. These engines produce 1.86 million pounds of thrust total.

OK, so that's enormous. But why does it matter for the WDR? Because loading 755,000 gallons of super-cold fuel into a vehicle this complex requires managing dozens of systems simultaneously. The liquid oxygen tank sits at the bottom of the core stage. The liquid hydrogen tank sits above it. Fuel lines run between the tanks and the main engines. Pressurization lines run to keep tanks at proper pressure. Vent lines release excess pressure. Sensing systems monitor every parameter. Computers orchestrate the entire flow.

Any single system failure could compromise the entire WDR. If the liquid oxygen system pressurizes incorrectly, fuel loading stops. If a valve sticks, flow stops. If a seal leaks, pressure drops. If a sensor malfunctions, engineers question whether data is accurate. If communications break down, teams lose situational awareness. The WDR tests all of this simultaneously.

The Space Launch System was designed with deep learning from Space Shuttle and earlier programs. Engineers incorporated decades of knowledge about what works and what doesn't. But incorporating knowledge and eliminating all failure modes are different things. Hardware is never perfect. No vehicle is ever fully debugged until it actually flies with humans aboard.

The WDR is a chance to get as close to perfect as possible before people strap in. It's the final verification that all the design, analysis, testing, and engineering throughout the SLS development program actually produces a vehicle capable of executing its mission.

The Team: Charlie Blackwell-Thompson and Mission Control

Spaceflight operations depend on teams. Individual heroes make good stories, but reality is collective execution under pressure. Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, NASA's launch director for Artemis II, represents the team that will execute Monday's WDR and eventually launch the mission.

Blackwell-Thompson has been working in spaceflight for decades. She's supervised countdowns. She's managed launch operations. She's learned from successes and failures. When she describes the WDR as "the best risk reduction test" available, she's drawing on deep professional experience.

The launch director role combines technical expertise with leadership responsibility. Blackwell-Thompson doesn't personally load fuel or calibrate sensors. But she makes critical decisions. She determines whether to continue or abort. She manages communication between dozens of teams. She maintains situational awareness of the entire operation. She bears ultimate responsibility for decisions made in the firing room.

When Blackwell-Thompson says "we need to see what lessons we learn as a result of that, and that will ultimately lay out the path toward launch," she's articulating a philosophy. The WDR isn't just a task to complete. It's an information-gathering operation. Every anomaly, every unexpected behavior, every system interaction teaches something. That knowledge informs go/no-go decisions about launch readiness.

Behind Blackwell-Thompson are teams of specialists. Propulsion engineers monitoring fuel systems. Avionics engineers watching vehicle computers. Communications specialists maintaining control channel continuity. Weather officers monitoring conditions. Safety officers ensuring protocols compliance. Hundreds of people in the firing room and at the launch pad, each with specific responsibilities.

The team culture matters more than people generally understand. If the organization encourages speaking up about problems, issues get surfaced early. If people fear punishment for bringing bad news, problems hide until they become critical. NASA learned painful lessons about organization culture during past programs. The agency deliberately built a culture where engineers can raise concerns without retaliation.

Monday's WDR will succeed or fail partly based on hardware, but equally based on how well the team functions. Can they communicate clearly? Do they trust each other? Do they make good decisions under pressure? Do they maintain focus for extended periods? Do they handle unexpected anomalies calmly?

These human factors don't show up on checklists, but they determine mission success as much as hardware specifications do.

The Artemis II mission is projected to launch in February 2024, with key milestones including the Wet Dress Rehearsal and potential launch windows extending into March 2024. Estimated data based on current plans.

The Physics of Propellant Loading: Why It's Harder Than It Sounds

Loading fuel into a rocket sounds straightforward. Open valves, pump fuel into tanks, close valves. Elementary. But the reality involves sophisticated physics operating at extreme conditions.

Liquid oxygen requires temperature management around minus 297 degrees Fahrenheit. That's cold enough to turn air liquid. At these temperatures, materials become brittle. Rubber and plastic components can crack. Metal contracts slightly. Insulation becomes critical. Any gap allows heat to leak in, warming the fuel slightly.

Liquid hydrogen is worse. At minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit, hydrogen approaches absolute zero. The molecule itself barely wants to exist in liquid form. Thermal insulation must be extraordinary to prevent boil-off. Even tiny temperature changes matter. The fuel naturally wants to evaporate. Engineers must actively manage heat flow to keep hydrogen liquid.

Both fuels expand and contract as they warm or cool. The expansion rate differs for different materials. This creates stress. Metal fuel tanks expand differently than the insulation layer or the outer structure. Different expansion rates create mechanical stress that could fail seals or gaskets if not managed correctly.

Pressure adds another layer of complexity. As fuel is loaded, pressure in the tank increases. Engineers must control that pressure increase gradually to avoid overstressing tank structures or lines. Too much pressure too fast risks rupture. Too little pressure allows fuel to boil or slosh.

Flow rates matter. Fast fuel flow creates momentum. When you suddenly shut a valve on fast-moving liquid, pressure spikes can develop. These pressure spikes could damage valves or burst lines. Engineers manage flow rates carefully to avoid these transient pressure problems.

Then there's the issue of thermal stratification. As fuel enters the tank, it might be at a different temperature than fuel already in the tank. Temperature differences can cause the fuel to stratify into layers. If those layers don't mix properly, sensors in one layer might read different values than sensors in another layer. Engineers must manage fuel loading to promote mixing and uniform temperature distribution.

All of this happens simultaneously. The team is loading fuel, managing pressure, controlling flow rates, monitoring temperatures, watching for leaks, and ensuring nothing exceeds safe operating limits. One mistake—a valve opening too fast, a temperature spike in an unexpected location, a sensor malfunction—propagates through the system and could compromise the entire operation.

This is why the "kinder, gentler" fueling procedure matters. By slowing everything down, by reducing pressure ramp rates, by preventing sudden transients, engineers give materials time to respond naturally to changing conditions. Seals can accommodate temperature changes gradually. Tanks can manage pressure increases smoothly. The entire system behaves more predictably.

The Launch Pad Infrastructure: More Than Just Concrete

The Space Launch System doesn't stand on a bare concrete pad. It stands in an elaborate ecosystem of infrastructure designed to support launch operations. Understanding what happens Monday requires understanding what all that infrastructure does.

The mobile launcher platform is essentially a massive steel structure on hydraulic legs. It contains fuel distribution systems, electrical systems, water systems for cooling and sound suppression, and structural elements to hold the rocket upright. Two of those hydraulic legs are the tail service masts—the gray structures visible jutting up from the launch pad.

These tail service masts house the critical connections where liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen flow into the Space Launch System's core stage. It's here that the seal failures plagued Artemis I. These masts house dozens of connection points, valve manifolds, and instrumentation. Any single leak in this area could compromise the entire WDR.

Beyond the mobile launcher platform, the pad has underground systems. Fuel storage tanks for propellant hold large quantities of liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. These tanks are insulated, refrigerated, and instrumented. They're connected to the pad via underground lines that must maintain pressure and temperature.

Above ground, the pad has power systems delivering electrical power to all systems. Water systems cooling electronic equipment and supporting sound suppression. Communications systems connecting the pad to mission control miles away. These systems aren't glamorous, but they're absolutely critical.

The launch tower itself provides crew access. Elevators and walkways allow personnel to reach various levels. The Orion spacecraft access arm is mounted to the tower. This arm will eventually swing aside when the rocket clears the pad, but during loading and countdown, it provides physical access to the crew compartment.

All of this infrastructure must function flawlessly for the WDR to succeed. A single major system failure could halt operations. A communications breakdown could leave mission control blind to launch pad conditions. A power glitch could interrupt critical systems. A water system malfunction could affect cooling systems needed to manage fuel temperatures.

This is why launch pad inspections and maintenance between missions matter so much. Seals get replaced. Valves get calibrated. Sensors get tested. Electrical systems get checked. Water systems get flushed. Every component gets verified as ready for the next operation. This preventive maintenance prevents problems from emerging during critical periods.

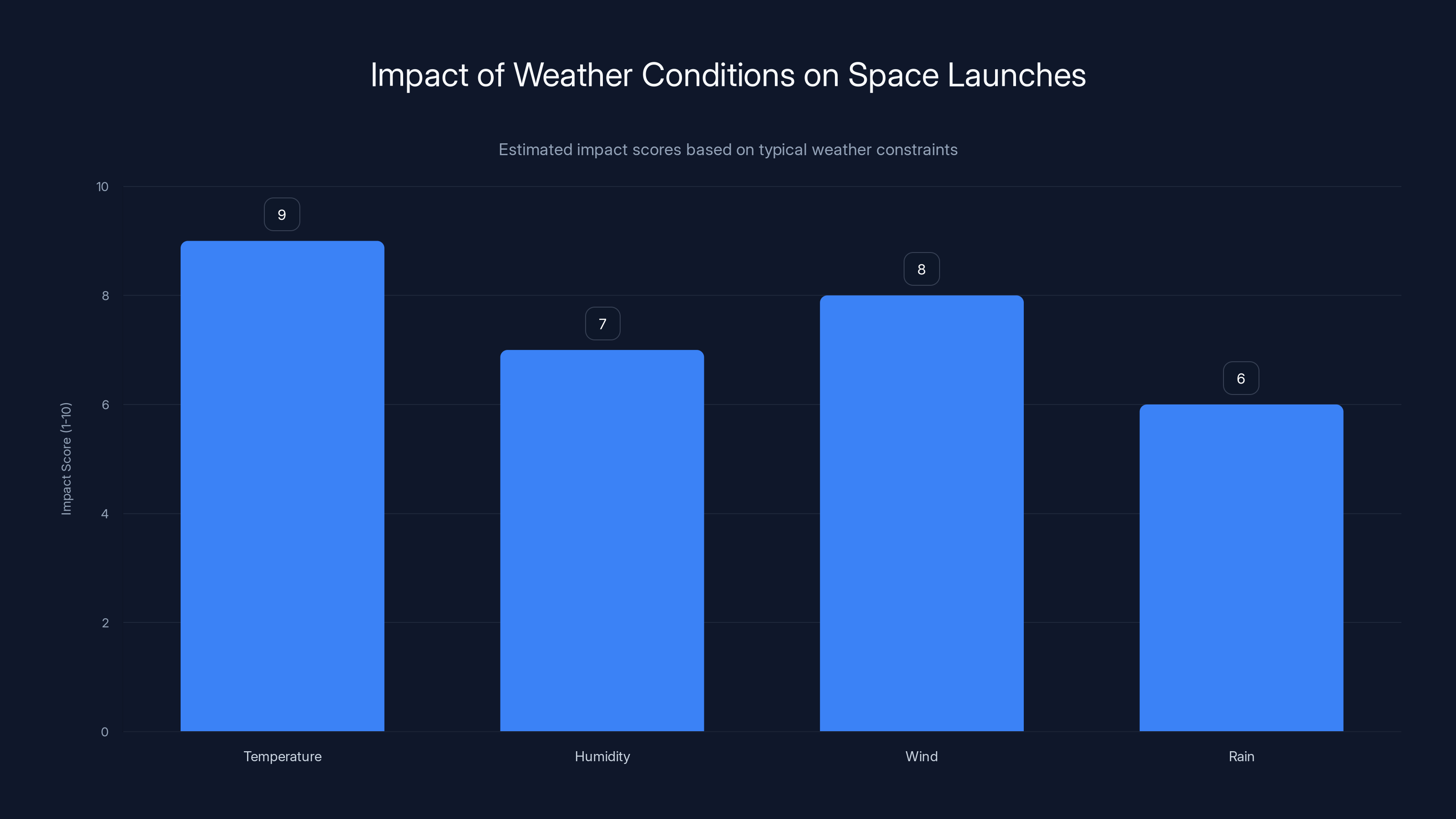

Temperature has the highest impact on space launches due to material and system constraints. Estimated data.

The Environmental Factor: Why Weather Matters

NASA delayed the WDR two days because of cold weather. That decision reveals something important about spaceflight. Environmental conditions aren't just inconveniences. They're fundamental constraints on operations.

Rockets have cold weather restrictions for good reasons. Extremely cold temperatures affect how materials behave. Metals become more brittle. Some rubber components can crack. Electrical systems might malfunction. Fuel systems behave differently. The Space Launch System was designed with assumptions about minimum operating temperatures.

When Central Florida experienced unusually cold temperatures, operations planners faced a decision. They could proceed with the WDR anyway, operating outside normal temperature constraints. Or they could delay and rehearse under more representative conditions. They chose to delay.

This decision prioritizes learning over schedule adherence. By rehearsing under conditions closer to what might actually occur on launch day, the team gains more realistic confidence. If they rehearsed in unusually cold conditions but launched in normal temperatures, they'd learn something different than what happens during the actual launch.

Weather affects more than just temperature. Humidity matters. Wind matters. Rain matters. All of these interact with launch vehicle systems in ways that aren't always obvious. The team wants to rehearse under conditions they might actually encounter.

There's also the practical matter of personnel safety. People working on launch pads need to be comfortable enough to function effectively. Extreme cold reduces dexterity, increases risk of mistakes, and causes personnel fatigue. Delaying two days to avoid working in unusually cold conditions is a reasonable operational decision.

Once the actual launch window arrives, weather becomes a hard constraint. If conditions are outside launch vehicle constraints, launch doesn't happen. No exceptions. Period. But during rehearsals and preparations, flexibility exists. NASA chose to use that flexibility to maximize learning and preparation quality.

The Path to Astronaut Certification: Why Unmanned Testing Comes First

Artermis II carries four astronauts into harm's way. Those astronauts need absolute confidence that the vehicle will protect them. That confidence doesn't come from analysis alone. It comes from demonstrated performance.

The sequence of testing matters. Artemis I, though unpiloted, proved fundamental concepts. It demonstrated that the Space Launch System could launch without catastrophic failure. It proved the Orion spacecraft could survive launch forces. It showed that basic operations work. But it didn't prove everything.

Artermis II will complete the circle. It will carry a crew on a lunar transit mission. That's fundamentally different from unmanned operations. Crew life support systems come into play. Radiation exposure becomes a consideration. Landing and recovery procedures become critical.

But before crew flies, the vehicle gets tested with maximum rigor. The WDR is part of that process. It's validation that propellant loading works. It's confirmation that the vehicle tolerates loading stresses. It's evidence that procedures developed on paper actually work in practice.

Each successful WDR, each successful test flight, each successful robotic mission builds confidence. This confidence eventually translates to the agency's willingness to accept the risk of putting humans aboard.

For the four Artemis II astronauts, Monday's WDR matters. A successful rehearsal means hardware is being prepared correctly. It means procedures developed by engineers actually work under realistic conditions. It means the team executing the mission has practiced. When the astronauts eventually board the Orion spacecraft on launch day, they'll know that this specific team, this specific hardware, and this specific procedure were validated in the WDR.

The Ripple Effects: Why This Mission Matters Beyond NASA

Artemis II might seem like a NASA mission. It is, technically. But the implications ripple outward much further. This mission represents the cumulative efforts of thousands of people, hundreds of companies, and decades of development. It demonstrates whether human spaceflight can reliably achieve lunar operations. It sets precedent for future deep space missions.

International partners are watching. The European Space Agency contributed components to the Orion spacecraft. Canada provided robotic systems. Japan, South Korea, and other nations follow the mission closely. Success builds confidence that lunar exploration is achievable. Failure creates doubt.

Commercial spaceflight companies are watching. Companies like Space X, Blue Origin, and others are developing their own lunar and deep space capabilities. They're learning from NASA's experience. Success in Artemis II validates approaches to lunar spaceflight. Failure raises questions about feasibility.

Policymakers and the public are watching. The Artemis program has been a continuous budget commitment requiring decades of sustained support. If Artemis II succeeds, it justifies continued funding for Artemis III and beyond. If delays continue indefinitely, political support erodes.

The four astronauts selected for Artemis II represent a statement that humans are ready to return to the Moon. It's a profound statement. These individuals have trained for years. They've prepared psychologically and physically for the mission. They believe in the system enough to trust their lives to it.

Monday's WDR doesn't directly involve those astronauts, but it validates the system they'll eventually fly. A successful rehearsal is a vote of confidence in the entire program.

The History: How We Got Here

Understanding Artemis II requires context about how we arrived at this moment. The Space Launch System wasn't built overnight. Development began years ago, driven by Congressional mandates to develop heavy-lift capability for deep space missions.

Early concepts date to around 2010. The Space Shuttle program was ending. NASA needed a new heavy-lift vehicle to reach destinations beyond low Earth orbit. Various designs were considered. Arguments raged about optimal configurations. Budgets were debated. Eventually, concepts solidified around the Space Launch System architecture.

Development proceeded slowly, constrained by budget limitations and competing priorities. Contractors built components. NASA tested systems. Engineers solved problems. Progress happened, but not rapidly. Costs escalated. Timelines slipped. The program absorbed setbacks that are endemic to large aerospace development efforts.

Artermis I finally launched in November 2022, more than a decade after development began. The mission succeeded technically but was delayed due to the propellant loading issues described earlier. Artemis II was scheduled for 2024. That didn't happen. Funding constraints, schedule pressures, and technical issues pushed it to 2025.

Now, in February 2025, the WDR represents the gateway to resuming human lunar missions. The path forward hinges on this single test and eventual launch. Success would be historic. Failure would be devastating—not catastrophic to hardware, but psychologically significant to a program that's absorbed so many delays.

The program represents a generational commitment. People who started careers on Artemis are now reaching middle age. New recruits have joined the effort. Throughout, a core group has remained committed to returning humans to the Moon. Monday's WDR represents one major milestone in a much longer journey.

Looking Forward: What Happens After February

If the WDR succeeds and Artemis II launches successfully, the space program enters a new era. Humans will return to lunar space for the first time since 1972. The mission will demonstrate that NASA can execute complex deep space operations reliably.

Artemis III is already in development. That mission will land humans on the lunar surface. It's a progression. Artemis II circles the Moon and validates systems. Artemis III goes to the surface. Artemis IV and beyond establish sustained presence.

Other nations have lunar aspirations too. China is pushing toward human lunar missions. Private companies are developing lunar landers and spacecraft. The Moon is becoming a destination for multiple actors. Artemis II validates that approach and establishes precedent.

Beyond the Moon lies Mars. Human Mars missions require technologies and capabilities being developed now. Artemis missions test those capabilities in the lunar environment before the deeper commitment of Mars exploration. Success compounds future possibilities.

But all of that is contingent on what happens in February and March. Monday's WDR is the critical waypoint. Success unblocks everything that follows. Failure delays progress but doesn't end the program. The team would regroup, investigate, and eventually try again.

These are the highest stakes in spaceflight. Not because hardware might be damaged—rockets are tools, replaceable. But because human confidence in the space program depends on demonstrating capability to execute complex missions reliably. The WDR matters because everything downstream depends on it succeeding.

The Human Element: Trust, Training, and Execution

Space missions succeed because trained teams execute flawlessly under pressure. Equipment quality matters. Procedures matter. Luck matters. But ultimately, teams execute complex operations involving thousands of interdependent systems and dozens of critical decisions. That's fundamentally a human endeavor.

The launch team has trained extensively. They've rehearsed procedures. They've discussed contingencies. They've studied what happened in 2022. They've mentally prepared for the challenges Monday brings. But no amount of preparation eliminates all uncertainty.

When the countdown clock starts Monday, the team will face situations they've never encountered. They'll need to make decisions with incomplete information. They'll need to stay calm when unexpected anomalies appear. They'll need to maintain focus across many hours of intense activity. These are skills honed through experience and professional discipline.

Trust is fundamental. Launch directors must trust their specialists. Specialists must trust each other. The entire team must trust the procedures and equipment. When trust breaks down, decisions become slow and communication becomes unclear. The team's performance degrades. This is why organizational culture matters as much as technical specifications.

Monday's WDR will be stressful. Things will go wrong—they always do in complex operations. The question isn't whether problems emerge. The question is how the team responds to problems. Do they panic? Do they communicate clearly? Do they make good decisions? Do they learn from the problems they encounter?

The astronauts who will eventually fly Artemis II are trusting the team at Kennedy Space Center. They're trusting engineers throughout NASA and contractor companies. They're trusting procedures developed by thousands of people. That trust isn't given casually. It's earned through demonstrated competence and successful missions.

When the WDR succeeds—and most indicators suggest it should—that trust becomes even stronger. The team proves again that they can execute complex missions successfully. The astronauts gain confidence that when launch day arrives, they're in capable hands.

FAQ

What is the Wet Dress Rehearsal for Artemis II?

The Wet Dress Rehearsal is a full simulation of the Artemis II launch countdown where engineers actually load 755,000 gallons of super-cold liquid propellants into the Space Launch System rocket. It's called "wet" because fuel flows, unlike dry dress rehearsals that use computers to simulate operations. The WDR verifies that all ground systems, the rocket itself, and launch procedures work correctly before the actual launch attempt.

Why did NASA delay the Wet Dress Rehearsal by two days?

NASA delayed the WDR to avoid performing the test during unusually cold temperatures in Central Florida. The space agency wanted to rehearse under conditions closer to what might occur on actual launch day. The Space Launch System has cold weather restrictions to ensure all vehicle systems operate within their design parameters. Additionally, cold weather makes working conditions harder for launch pad personnel, increasing error risk.

What are the launch windows if the WDR succeeds?

If the WDR succeeds without major problems, NASA has three launch windows available in February 2025: February 8 at 11:20 pm EST, February 10 at 12:06 am EST, and February 11 at 1:05 am EST. Each window is two hours long. All are overnight launch windows dictated by orbital mechanics. If NASA misses all three February opportunities, the next available launch window is March 6, 2025.

What problems did Artemis I's propellant loading encounter?

Artemis I experienced hydrogen seal failures during its four Wet Dress Rehearsal attempts in 2022. Liquid hydrogen at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit caused seals and gaskets to change shape, creating leak paths. Engineers also encountered problems with gaseous nitrogen supply systems and liquid oxygen temperature management. The issues delayed launch from August to November 2022 but eventually were resolved using a slower, "kinder, gentler" fueling procedure.

Why is liquid hydrogen so difficult to contain in rockets?

Liquid hydrogen is extremely cold (minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit) and has a tiny molecular size, making it prone to leaking from even microscopic gaps. When liquid hydrogen contacts seals and gaskets, it causes thermal shock that changes material shape and size. Leaks that appear at cryogenic temperatures disappear when materials warm up at room temperature, making ground-testing nearly impossible. Pressure management and controlled fueling rates are critical to prevent seal failures.

How many astronauts will Artemis II carry?

Artemis II will carry four astronauts on a nearly 10-day mission around the far side of the Moon and back to Earth. These will be the first humans to launch on the Space Launch System rocket and the first people to travel to the vicinity of the Moon since 1972, making this the farthest humans have traveled from Earth in over 53 years.

What is the role of Charlie Blackwell-Thompson in the WDR?

Charlie Blackwell-Thompson is NASA's launch director for the Artemis II mission. She supervises the practice countdown from the firing room at Launch Control Center, about a few miles from the launch pad. Her role includes making critical go/no-go decisions, managing communication between multiple teams, and maintaining overall situational awareness. She bears ultimate responsibility for the launch operation's success.

How does the Space Launch System compare to previous NASA rockets?

The Space Launch System is the most powerful rocket NASA has ever built. It stands 322 feet tall and produces 1.86 million pounds of thrust from its four RS-25 main engines. The core stage alone is 212 feet long and carries 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen fuel and 196,000 gallons of liquid oxygen. It's specifically designed for deep space missions requiring heavy lift capability beyond low Earth orbit operations.

Conclusion: The Gateway to the Next Era of Spaceflight

Monday's Wet Dress Rehearsal represents far more than a procedural milestone. It's the gateway to humanity returning to the Moon after more than fifty years. It's validation that the Space Launch System can reliably support deep space missions. It's proof that NASA can sustain multi-decade programs and eventually execute the complex missions they were designed to achieve.

The test won't be perfect. Anomalies will emerge. Engineers will troubleshoot. Problems will be identified and addressed. That's not failure—that's exactly how complex systems get validated. The goal isn't zero problems. The goal is identifying problems in rehearsal where they can be fixed, not during the actual launch where consequences are infinitely higher.

Charlie Blackwell-Thompson and her team at Kennedy Space Center have trained for this moment. Engineers throughout NASA and contractor companies have refined procedures. Hardware has been inspected and verified. The team is as ready as any human endeavor can be to conduct a major spaceflight operation.

For the four astronauts waiting to fly Artemis II, Monday's success represents one more confirmation that their trust is justified. When they eventually strap into the Orion spacecraft atop the Space Launch System, they'll know that this specific team, this specific rocket, and these specific procedures were validated in realistic conditions. They'll know they're flying on hardware that's been stress-tested and proven reliable.

The implications extend beyond NASA. International partners watching the program gain confidence in human spaceflight capability. Commercial companies developing lunar systems learn from Artemis success. Policymakers see validation that sustained space programs can achieve extraordinary goals. The public witnesses something that's become rare: a government program executing on its most ambitious promises.

Failure wouldn't end the Artemis program. Hardware is replaceable. Schedules can slip. But decades of investment, human commitment, and national aspirations converge on one mission. Getting to the Moon—returning humans to lunar space—has been deferred too many times already. This launch window might slip if Monday goes poorly. But eventually, Artemis II will fly. Humans will return to the Moon.

Monday's Wet Dress Rehearsal is the critical test that clears the path forward. Everything else flows from whether this team succeeds in the next 48 hours. The countdown is running. The rocket is being prepared. The world is watching. And in the firing room at Kennedy Space Center, launch director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson and her team are ready to execute the most important test before humanity's next giant leap.

Key Takeaways

- Monday's Wet Dress Rehearsal loads 755,000 gallons of super-cold propellants into the Space Launch System to simulate actual launch countdown

- Success clears the way for Artemis II launch as soon as February 8, 2025; failure likely pushes to March 6 or later

- Liquid hydrogen at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit caused persistent seal failures during Artemis I's four WDR attempts in 2022

- NASA refined fueling procedures using a slower, 'kinder, gentler' approach that reduces thermal shock and prevents seal leaks

- Four astronauts will fly Artemis II on a nearly 10-day mission around the far side of the Moon—the farthest humans have traveled since 1972

Related Articles

- Artemis II Launch Delayed by Cold Weather: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Artemis II: The Next Giant Leap to the Moon [2025]

- NASA's Crew-11 Early Return: What the Medical Concern Means [2025]

- NASA Spacewalk Delay: Medical Concerns, ISS Operations & Crew Safety [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development [2025]

- NASA Used Claude to Plot Perseverance's Mars Route [2025]

![Artemis II Wet Dress Rehearsal: NASA's Final Test Before Moon Launch [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/artemis-ii-wet-dress-rehearsal-nasa-s-final-test-before-moon/image-1-1770041298292.jpg)