Avoiding Ultraprocessed Foods for Healthier Aging: What New Research Reveals

Here's something that probably won't surprise you: the foods we eat shape how we age. But the details matter more than you might think. The processed food industry has spent decades perfecting products that taste incredible, cost almost nothing, and require zero effort to prepare. The trade-off? Your health.

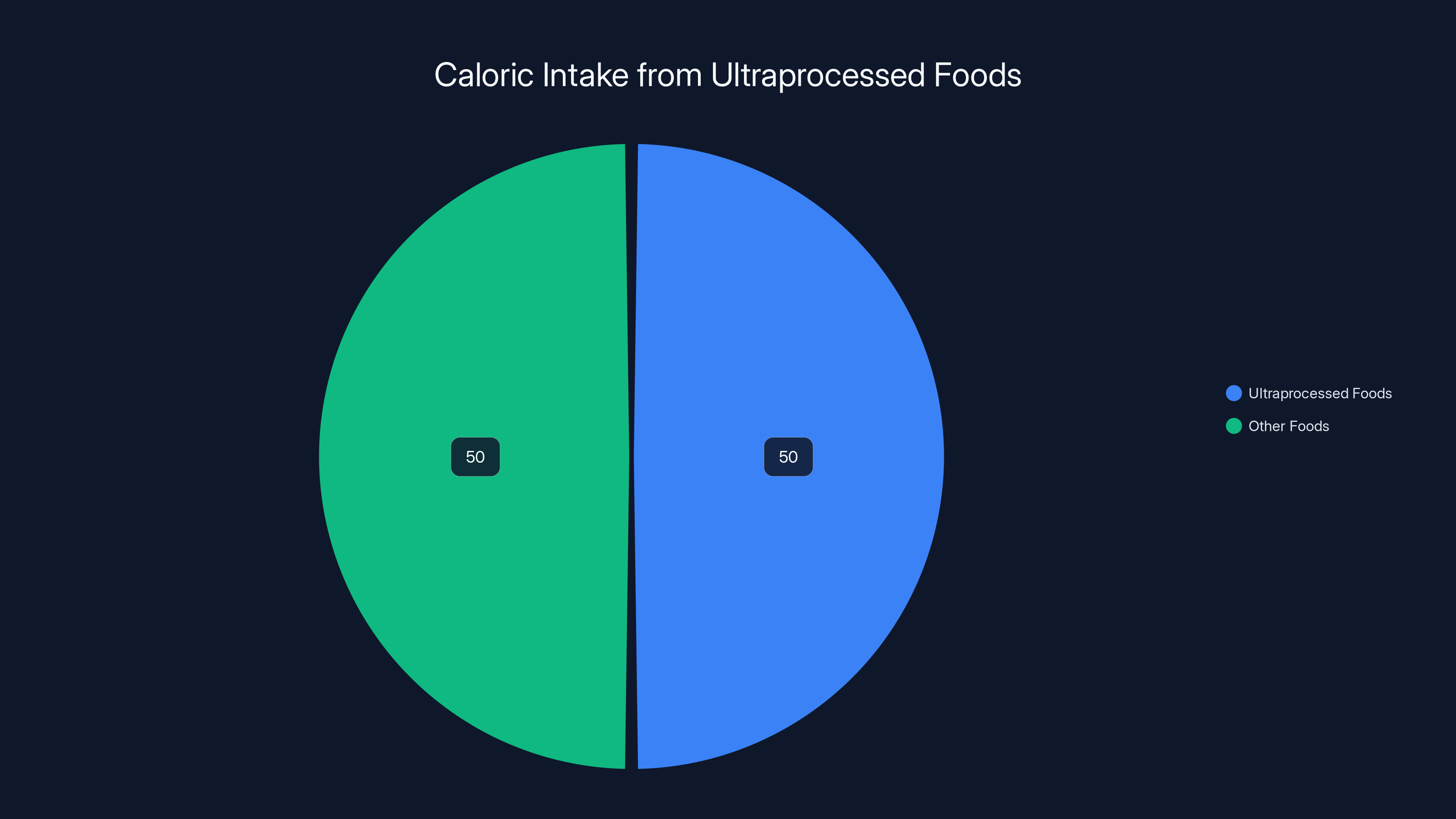

I'm not being dramatic. Over 50% of the calories consumed by the average American comes from ultraprocessed foods. That's not a small slice of the diet—that's the foundation of how most people eat. And the consequences accumulate quietly over years, manifesting as weight gain, sluggish metabolism, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation that sets the stage for disease.

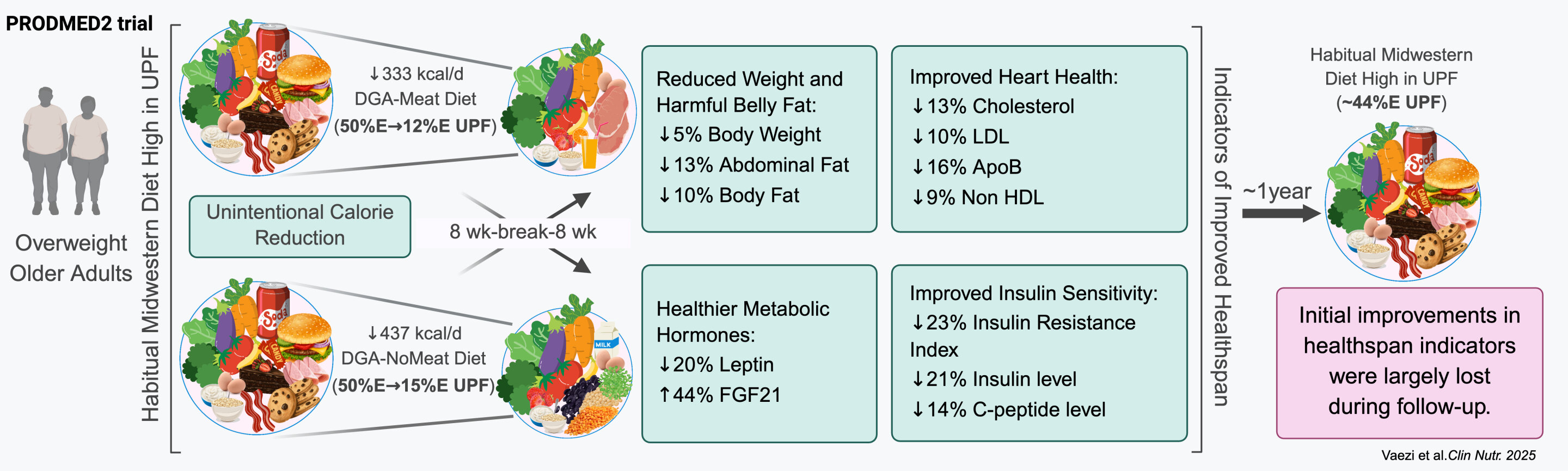

But here's the encouraging part: you don't need a complete dietary overhaul to see real improvements. New research published in Clinical Nutrition shows that older adults can make meaningful progress with a realistic, everyday reduction in ultraprocessed foods. Not a 100% elimination. Not a restrictive diet. Just less processed stuff, more real food.

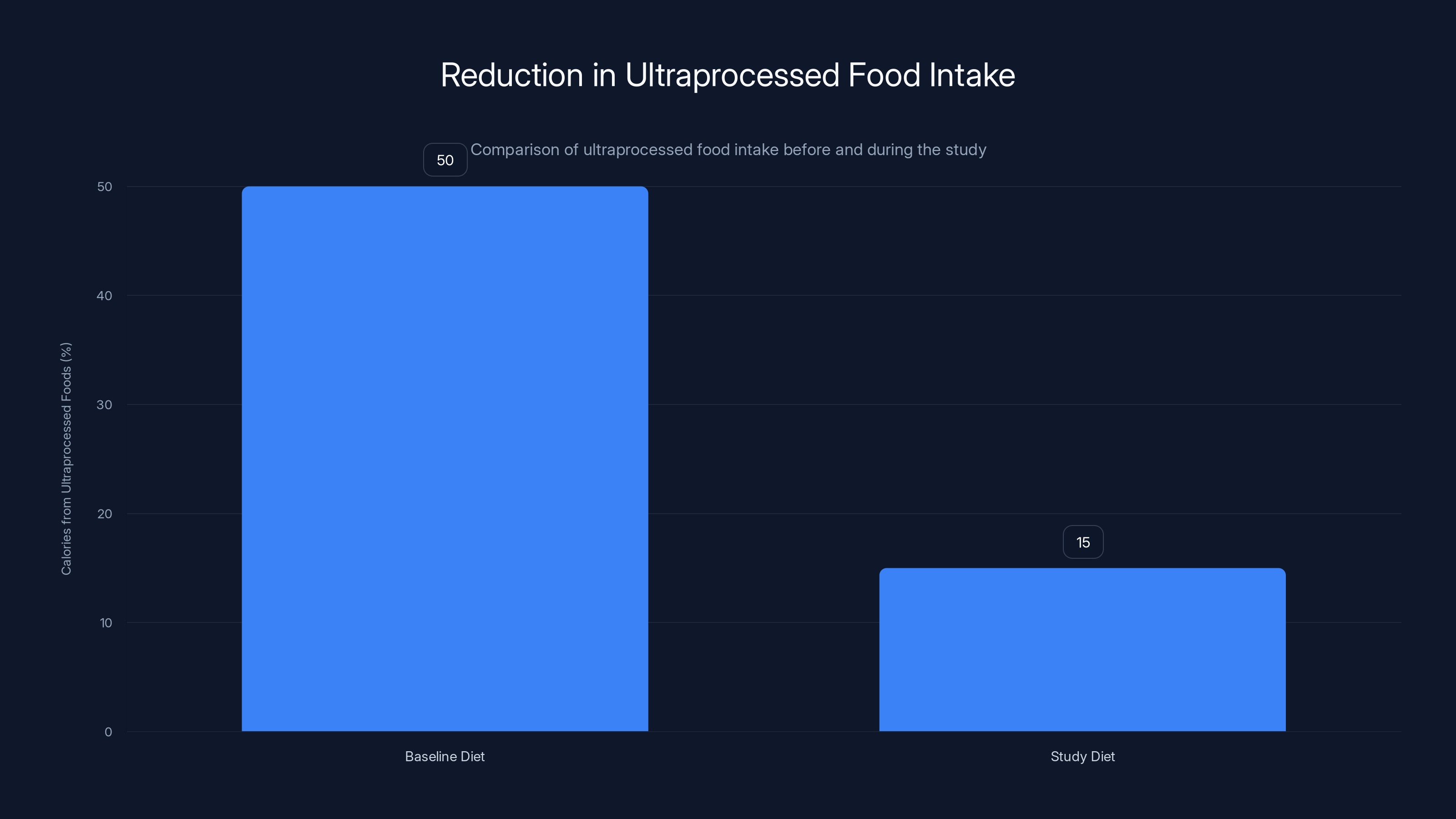

The study enrolled Americans ages 65 and older, many dealing with weight challenges and metabolic issues. For eight weeks, participants ate two different diets, each keeping ultraprocessed foods to less than 15% of total calories. That's a dramatic shift from their baseline, but it's achievable. And the results? Weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, healthier cholesterol, reduced inflammation, and better appetite regulation hormones. These weren't minor tweaks on a lab report—these were meaningful, measurable improvements in the biological markers that predict healthy aging.

What makes this research different is that it mirrors real life. Participants weren't living in a clinical trial center. They were eating actual meals designed to be familiar and balanced. The foods were prepared for them to control for consistency, but the diets looked like something normal people could actually eat at home.

This guide breaks down what the research actually shows, why ultraprocessed foods damage your metabolism specifically, and how to make practical changes that stick without turning your life upside down.

TL; DR

- Ultraprocessed foods comprise over 50% of calories in typical American diets, but recent research shows reducing them to 15% yields measurable health improvements

- Weight loss and metabolic improvements occurred naturally without calorie restriction or exercise changes when ultraprocessed foods were reduced

- Insulin sensitivity, cholesterol levels, inflammation markers, and appetite hormones all improved in just eight weeks of eating less processed food

- The improvements were similar across both meat-based and vegetarian diets, suggesting the processing level matters more than specific protein sources

- Real-world applicability is key: the diet wasn't extreme or restrictive, making it sustainable for older adults and others managing metabolic health

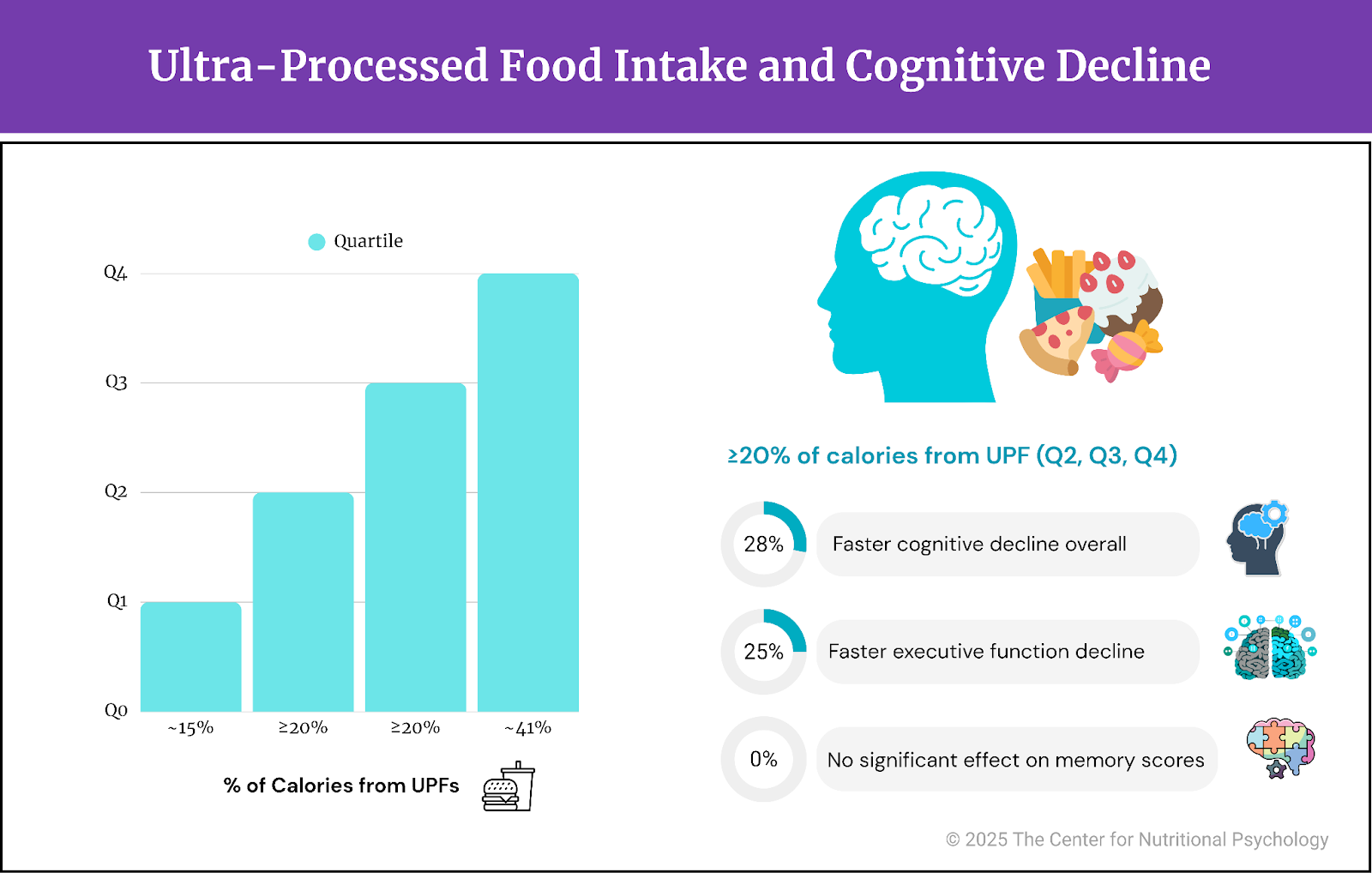

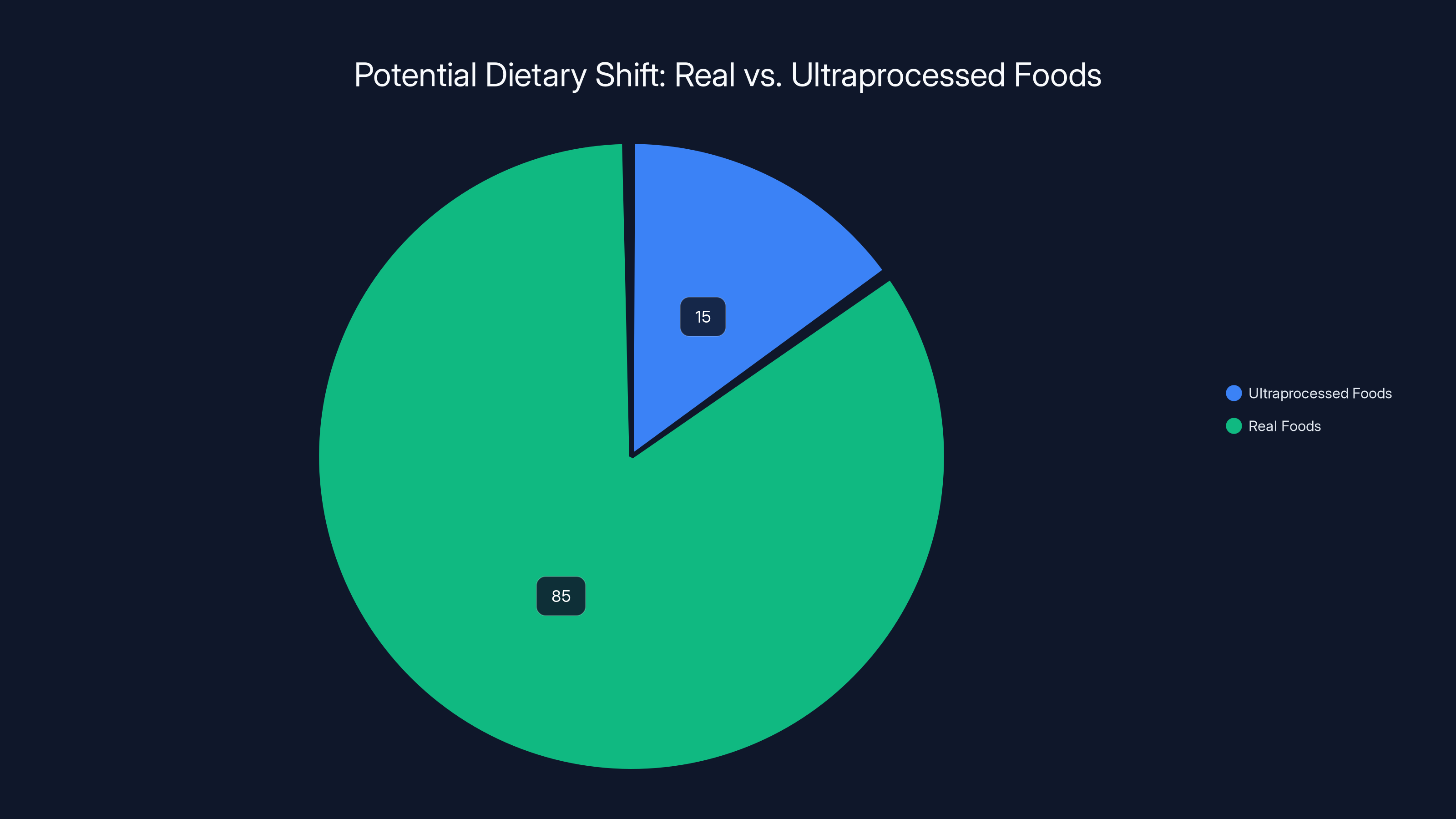

The study participants reduced their ultraprocessed food intake to 15% of total calories, compared to the average American's 50%, leading to significant health improvements. Estimated data based on study context.

What Exactly Are Ultraprocessed Foods, and Why Do They Matter?

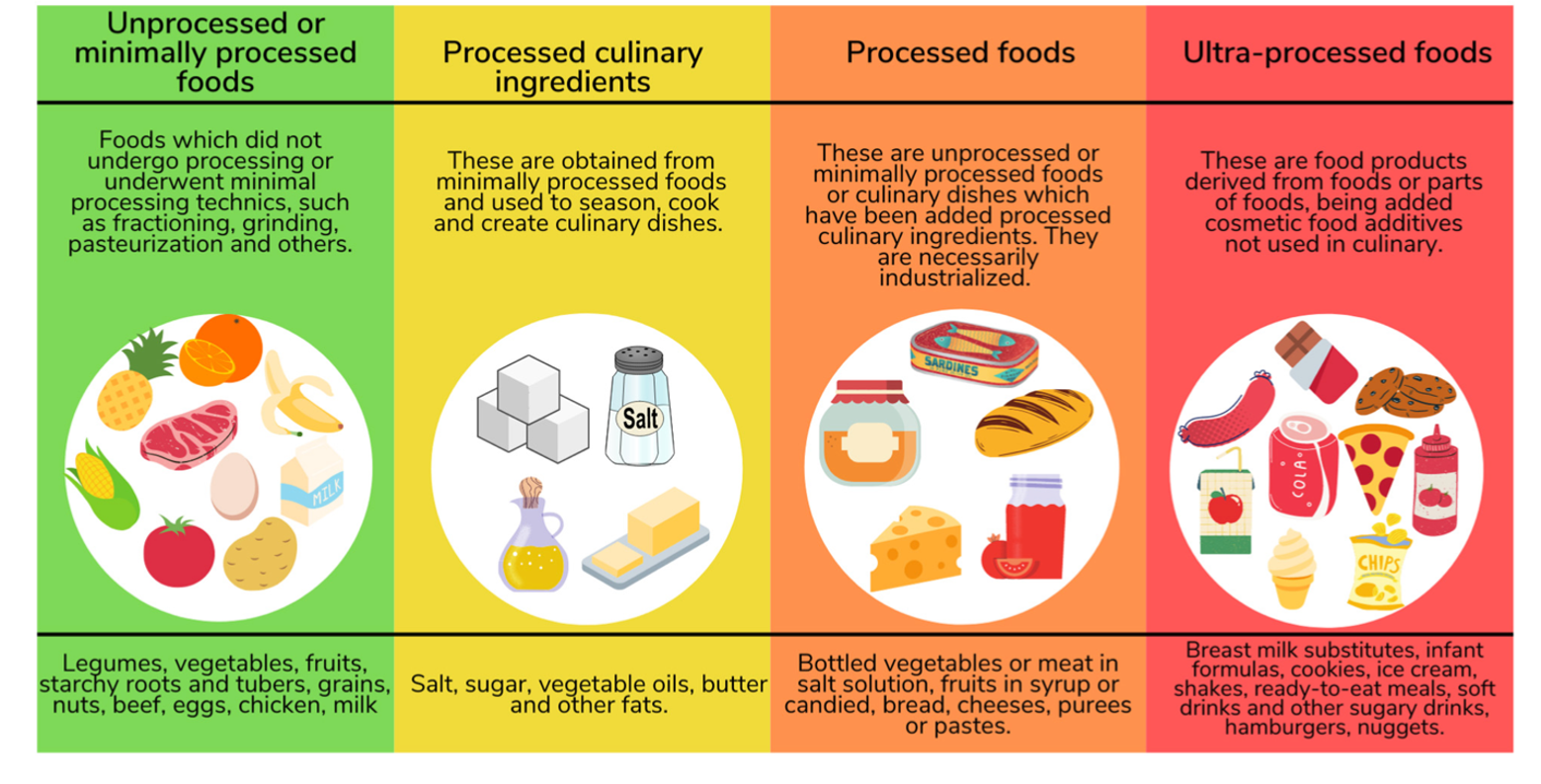

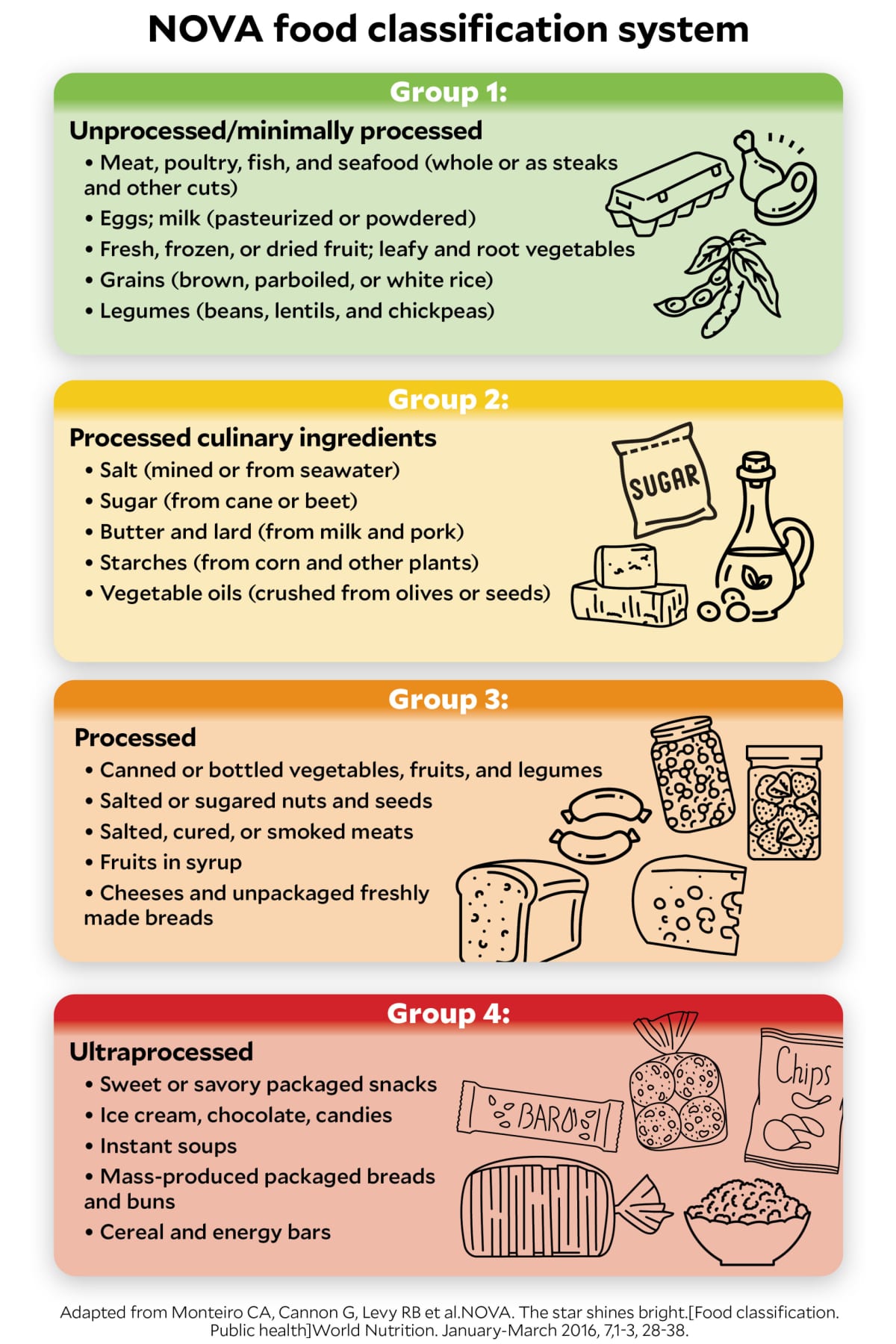

When you hear "ultraprocessed foods," your mind probably jumps to junk food. That's partially true, but the definition is actually more technical and revealing. Ultraprocessed foods are manufactured using industrial techniques and ingredients that you'd never use in home cooking. They're engineered products, not foods that happen to be processed.

Think about the difference. A can of beans is processed: the beans are cooked and preserved. You could theoretically do this at home. But a flavored yogurt-like product with 12 additives, emulsifiers, and artificial sweeteners? That's ultraprocessed. You couldn't make it at home if you tried.

The hallmark ingredients of ultraprocessed foods include emulsifiers that keep ingredients mixed together, flavorings that are chemically synthesized rather than derived from food, artificial colors, preservatives that extend shelf life far beyond what nature allows, and texture modifiers that make mushy ingredients feel crispy or crunchy.

Common examples you probably buy regularly include packaged snacks like chips and cookies, ready-to-eat meals that just need reheating, most flavored cereals, sweetened beverages, processed meats like hot dogs and deli meat, instant noodles, many breakfast bars, flavored yogurts, and most fast food. The category is huge. The average supermarket probably dedicates 60% of its shelf space to ultraprocessed products.

Why does this matter for aging? Because ultraprocessed foods are designed to override your body's natural satiety signals. Manufacturers and food scientists specifically engineer these products to be hyper-palatable—more appealing than naturally occurring foods. They hit taste, texture, and visual appeal in ways that trigger dopamine release and diminish your feeling of fullness.

You'll eat past the point where you'd stop with regular food. You'll reach for seconds and thirds. The calories add up before your brain even registers that you should be satisfied. Over weeks and months, this drives weight gain. Over years, it drives metabolic dysfunction.

The additives themselves aren't inert. Emulsifiers have been shown to alter gut bacteria composition in ways that promote inflammation. Artificial sweeteners confuse your body's metabolic signaling, making it harder to regulate appetite accurately. The combination of high-calorie density and appetite dysregulation creates a metabolic disaster for aging adults who are already facing natural metabolic slowing.

Participants reduced their intake of ultraprocessed foods from over 50% to less than 15% of total calories during the study, highlighting a significant dietary change.

The Aging Problem: Why Metabolism Changes After 65

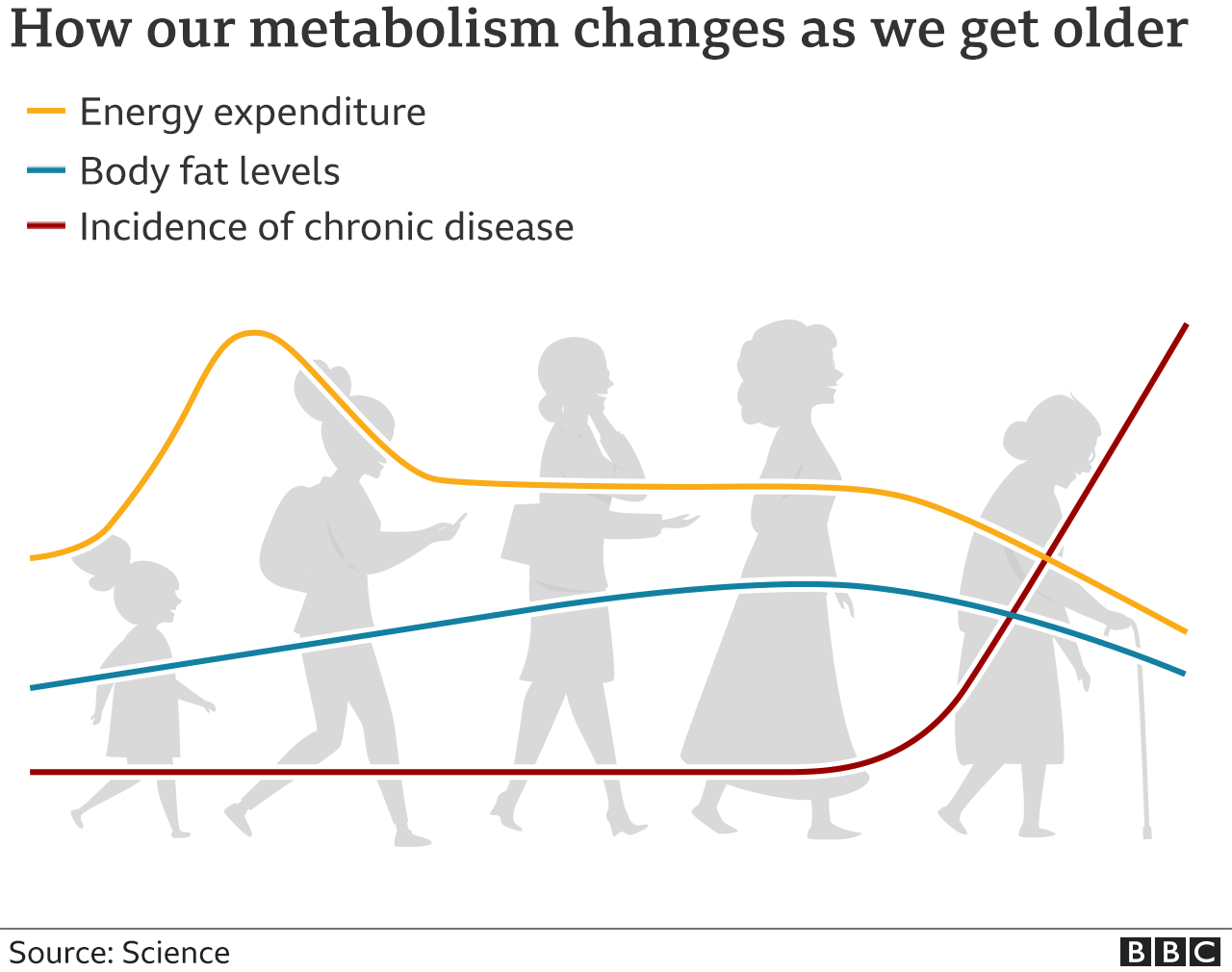

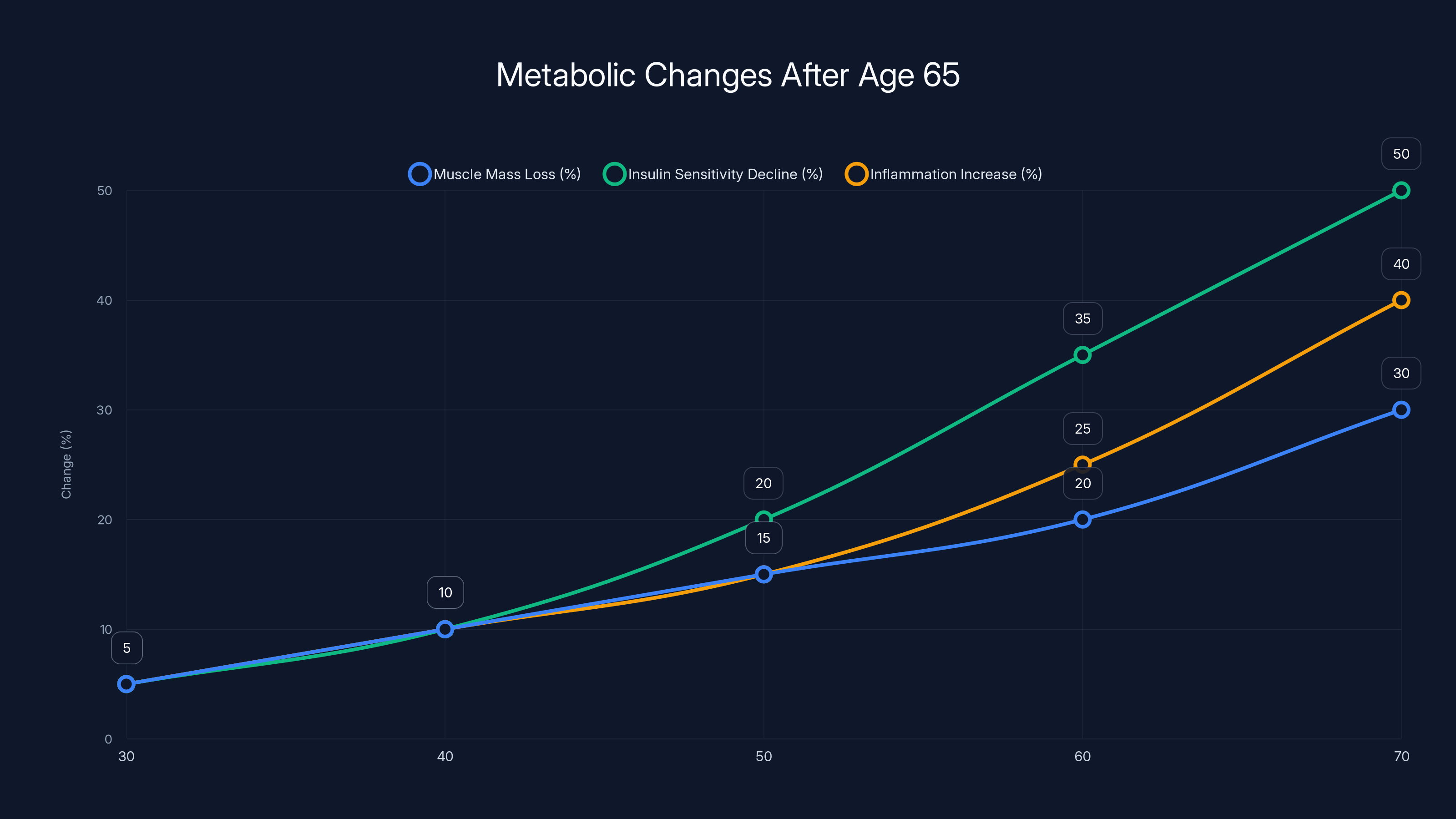

The human body doesn't age in a straight line. There are inflection points where things shift. Around age 65, several metabolic changes accelerate simultaneously, and this is exactly why the research on ultraprocessed foods focused on this age group.

After 65, you naturally lose muscle mass at a faster rate, a process called sarcopenia. You lose roughly 3-8% of muscle per decade after age 30, but the rate increases after 60. Muscle is metabolically active tissue—it burns calories just sitting there. When you lose it, your resting metabolic rate drops. Suddenly, the same diet that maintained your weight at 60 causes weight gain at 70.

Your insulin sensitivity declines with age. Your pancreas still makes insulin, but your cells respond less effectively to it. This is why Type 2 diabetes prevalence jumps so dramatically in older populations. It's not just that older people make worse food choices—it's that their bodies are biologically more vulnerable to the metabolic disruption that ultraprocessed foods cause.

Hormonal changes accelerate aging-related weight gain. Ghrelin, the hunger hormone, increases. Leptin, the satiety hormone, becomes less effective. These aren't new hormones—they've been active your whole life—but their signaling shifts in ways that promote overconsumption. Ultraprocessed foods supercharge this effect because they're specifically designed to maximize ghrelin stimulation and minimize leptin signaling.

Inflammation increases with age in a process called inflammaging. This is chronic, low-level inflammation that doesn't cause obvious symptoms but drives tissue damage, joint degradation, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline. Ultraprocessed foods containing emulsifiers and high levels of refined carbohydrates directly increase inflammatory markers.

The combination of these changes means that older adults face a perfect storm. Their bodies are already pushing them toward metabolic dysfunction, and dietary choices that younger people might tolerate create significant problems.

But here's the encouraging part: the research shows these changes aren't irreversible. They're responsive to dietary change. Within weeks, not years, metabolic markers improve.

The Research: How They Tested Real-World Dietary Change

Most nutrition studies are garbage. I don't mean that harshly, I mean that as a technical assessment. They're either so artificial that they don't reflect real life, or they rely on self-reported dietary data where participants guess what they ate. Both approaches produce unreliable results.

This study took a different approach. Researchers enrolled 43 older Americans with metabolic risk factors. Many were overweight. Some had insulin resistance or high cholesterol. These weren't health-conscious individuals who already ate well—they were typical Americans with typical metabolic problems.

Participants followed two different diets for eight weeks each. The first was a meat-based diet emphasizing lean pork. The second was vegetarian, including milk and eggs. Between the two diet periods, they returned to their normal eating patterns for two weeks. This design served a purpose: it let researchers see the contrast between their baseline intake and the intervention.

The critical detail is what researchers actually controlled. They prepared, portioned, and provided all meals and snacks. Participants didn't go grocery shopping, didn't prepare their own food, didn't estimate portions. This eliminated the variables that plague most nutrition studies. Researchers knew exactly what participants ate.

In both diet periods, ultraprocessed foods made up less than 15% of total calories. To understand how dramatic this shift was, consider the baseline. The typical American diet derives more than 50% of calories from ultraprocessed foods. So this was more than a 65% reduction in processed food calories. Not trivial.

But here's what made it realistic: participants weren't told to restrict calories, lose weight, or change their exercise habits. They weren't following a formal diet. They were simply eating meals and snacks that were lower in processing. The calories were roughly matched to their typical intake. The macronutrients aligned with government dietary guidelines. The foods were familiar—chicken, fish, vegetables, fruits, whole grains, beans. Nothing exotic.

Both diets emphasized minimally processed ingredients and aligned with the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the government's evidence-based recommendations for healthy eating. The diets provided similar total calories and comparable amounts of key nutrients like protein, fiber, and micronutrients. The main difference was processing level.

Out of 43 participants who started, 36 completed the full study. That completion rate is excellent for a feeding study, suggesting that participants found the diets livable.

Controlled feeding studies provide the highest accuracy (95%) in dietary data, compared to self-reported methods which can be as low as 60%.

Weight Loss and Body Composition: The Obvious but Important Results

Let's start with the most straightforward finding: participants lost weight. And they did it without being told to restrict calories or exercise. The weight simply came off when they reduced ultraprocessed foods.

This isn't actually surprising if you understand how ultraprocessed foods work. They're calorie-dense and appetite-dysregulating. A typical ultraprocessed snack might pack 300 calories and leave you feeling hungrier than before. A real-food equivalent might be 150 calories and leave you satisfied. When you replace one with the other, without actively restricting, you naturally consume fewer calories.

But the body composition changes were more interesting than simple weight loss. Participants lost not just weight but specifically body fat, including visceral abdominal fat. This matters because visceral fat—the fat around your organs—is metabolically active and inflammatory. It's more strongly linked to metabolic disease and mortality than subcutaneous fat, the fat under your skin.

Visceral fat reduction is harder to achieve than general weight loss, yet it happened here without intentional exercise change. This suggests that the dietary shift had a direct metabolic effect beyond simple calorie reduction.

Weight loss happened at nearly identical rates whether participants followed the meat-based or vegetarian diet. This is important because it means the protein source didn't matter much. The processing level mattered far more. Too many dietary conversations get hung up on whether to eat meat or avoid it, as if that's the primary lever. This research suggests that if you're eating ultraprocessed versions of either diet, the type of protein barely matters. The processing level dominates the health outcome.

The weight loss itself had metabolic significance. Each pound of weight loss, particularly of visceral fat, improved insulin sensitivity and reduced inflammatory markers. But the metabolic improvements actually exceeded what you'd expect from weight loss alone, suggesting that something about eating real food—beyond just weighing less—improved metabolic function.

Insulin Sensitivity: The Most Important Metabolic Marker You Don't Monitor

Here's a metabolic reality: you can look thin and be metabolically broken. You can have a BMI in the normal range and have terrible insulin sensitivity. Conversely, you can improve insulin sensitivity without dramatic weight loss.

Insulin sensitivity is your body's ability to respond to insulin signaling and take glucose out of the bloodstream. When you eat carbohydrates, your blood sugar rises. Your pancreas releases insulin. That insulin tells your cells to take up glucose and either use it for energy or store it. If your cells respond effectively, blood sugar normalizes quickly. If they don't—if you have insulin resistance—blood sugar stays elevated, your pancreas releases more insulin, and the whole system gets more dysfunctional.

Insulin resistance is a direct pathway to Type 2 diabetes. It's also linked to cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, and faster aging at the cellular level. Improving insulin sensitivity is arguably the single most important thing you can do for healthy aging.

The research showed marked improvements in insulin sensitivity within eight weeks of reducing ultraprocessed foods. This was measured using established markers that reflect real metabolic change, not just numbers on a lab report.

Why did this happen? Several mechanisms are likely involved. First, ultraprocessed foods typically have a high glycemic index—they cause rapid blood sugar spikes. Your pancreas has to work harder to manage these spikes. Over time, this damages insulin signaling. Remove the spikes, and the system recovers.

Second, many ultraprocessed foods contain refined carbohydrates that lack fiber. Fiber slows glucose absorption and improves insulin signaling. Real food diets naturally contain more fiber, which improves glucose metabolism independently of calorie content.

Third, additives in ultraprocessed foods may directly damage insulin signaling. Some emulsifiers have been shown to impair gut barrier function and increase systemic inflammation, both of which promote insulin resistance.

The improvement in insulin sensitivity was similar across the meat and vegetarian diets, again emphasizing that protein source mattered less than processing level.

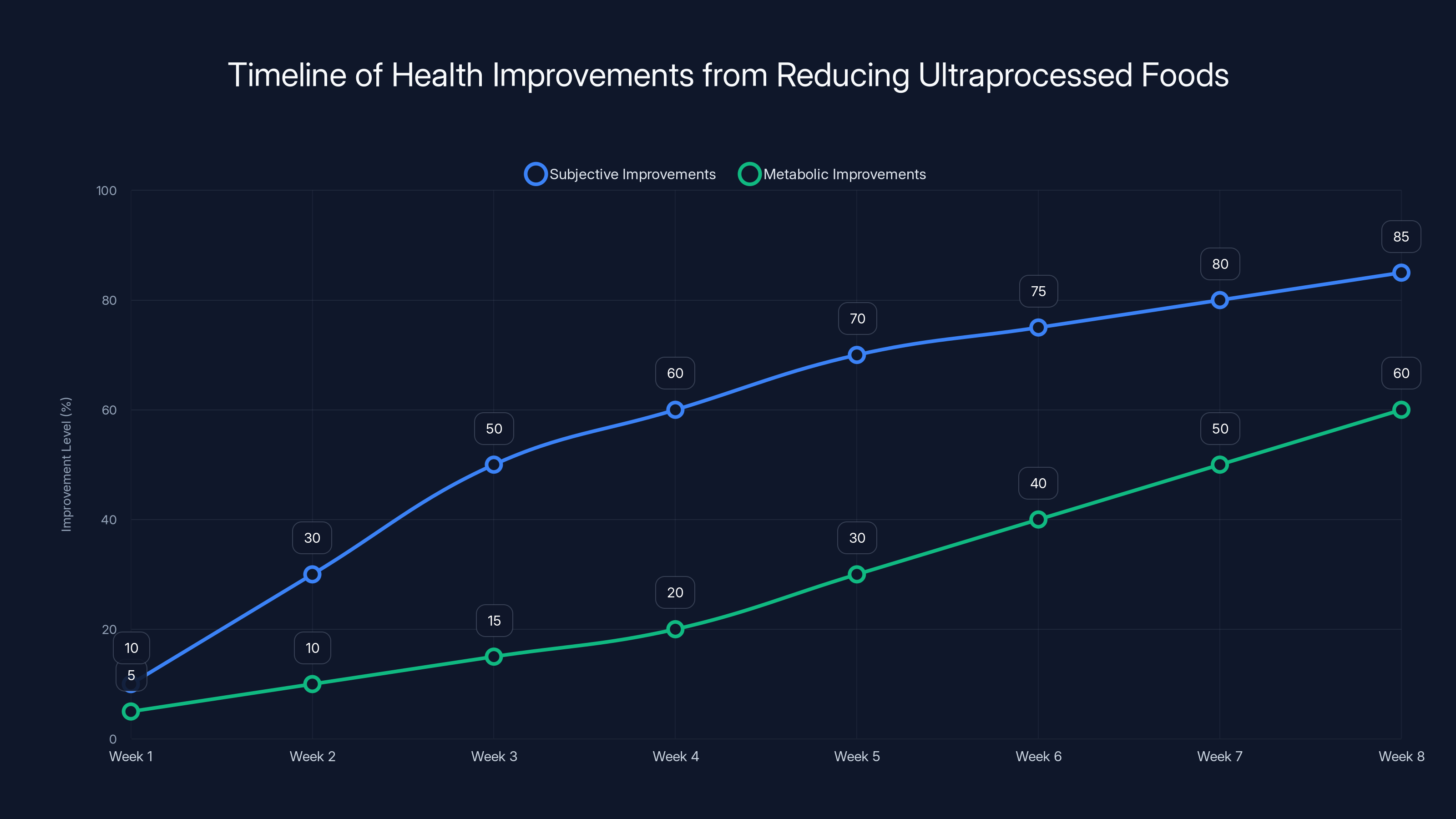

Research indicates subjective health improvements, such as better energy and digestion, can be noticed within 2-3 weeks of reducing ultraprocessed foods. Metabolic improvements become measurable within 8 weeks.

Cholesterol and Lipid Profiles: Beyond Just Total Cholesterol

When most people think about cholesterol and diet, they think about avoiding fat and keeping total cholesterol low. This is outdated thinking. Your cholesterol profile is far more nuanced.

The research showed improvements in multiple lipid markers. But which ones matter most? Total cholesterol is almost meaningless. LDL cholesterol is more relevant, but even that misses important details. HDL cholesterol—the "good" cholesterol—is often more predictive of cardiovascular health than LDL. Triglycerides, often ignored in casual health conversations, are actually strongly linked to cardiovascular disease and metabolic dysfunction.

The ultraprocessed food diets had worsened lipid profiles. The real-food diets improved them. Why? Ultraprocessed foods are typically high in refined carbohydrates, which elevate triglycerides. They often contain unhealthy fats—trans fats or highly oxidized vegetable oils. They lack the polyphenols and fiber that improve HDL and reduce triglycerides.

Real food diets, by contrast, naturally contain more fiber, which lowers LDL cholesterol. They contain healthy fats—from nuts, seeds, olive oil, fish—that improve HDL. Whole grains contain compounds that reduce triglycerides. The lipid improvements weren't from fat restriction; they came from food quality improvement.

Again, meat-based and vegetarian diets showed similar improvements, suggesting that cholesterol improvements weren't about animal product avoidance—they were about avoiding ultraprocessed versions of whatever diet you followed.

Inflammation Markers: The Aging Accelerator

Inflammation is the thread connecting most chronic diseases of aging: cardiovascular disease, arthritis, cognitive decline, cancer, and metabolic disease. It's not like a fever—it's subtle, ongoing, and doesn't announce itself with obvious symptoms.

When researchers measure inflammation, they typically look at markers like C-reactive protein, cytokines, and other inflammatory signaling molecules. These markers increased when participants ate their normal diets (which typically contained 50%+ ultraprocessed food) and decreased significantly when they shifted to real-food diets.

How does ultraprocessed food drive inflammation? Multiple pathways. High-sugar diets directly activate inflammatory pathways. Advanced glycation end products—compounds formed when sugars interact with proteins—accumulate in tissues and trigger inflammation. Emulsifiers in ultraprocessed foods damage the intestinal barrier, allowing bacterial products into circulation where they trigger immune activation. Refined carbohydrates shift gut bacteria composition toward species that produce inflammatory metabolites.

Real food, by contrast, contains anti-inflammatory compounds. Polyphenols from fruits and vegetables are potent anti-inflammatories. Fiber feeds healthy gut bacteria that produce anti-inflammatory metabolites. Omega-3 fats from fish and seeds provide raw material for anti-inflammatory signaling molecules.

The inflammation reduction happened relatively quickly—within weeks, not months. This suggests that inflammation from ultraprocessed foods is a reversible process, at least in early stages.

Estimated data shows significant increases in muscle mass loss, insulin sensitivity decline, and inflammation after age 65, highlighting the metabolic challenges faced by older adults.

Appetite Regulation Hormones: Why You Overeat on Ultraprocessed Food

This might be the most personally relevant finding. Have you noticed that after eating ultraprocessed snacks, you're hungrier than before? That's not willpower weakness—that's biology.

Your body uses hormonal signaling to regulate appetite. Ghrelin increases appetite. Leptin decreases appetite. Peptide YY and other hormones modulate fullness. These systems work well in nature—they keep you eating when you need energy and stop you when you've consumed enough.

Ultraprocessed foods actively disrupt this signaling. Their hyperpalatable combination of sugar, salt, fat, and texture stimulates ghrelin release. Their refined carbohydrates don't trigger normal satiety signaling. They contain additives that may directly impair leptin signaling.

The research showed that appetite-regulating hormones shifted significantly when participants reduced ultraprocessed foods. Ghrelin decreased—they felt less hungry. Leptin signaling improved—their bodies better recognized fullness. Other satiety hormones increased.

This is why real-food diets work for weight loss without feeling like dieting. You're not fighting your biology constantly. You're eating food that your body correctly interprets as nourishing, so you stop eating when satisfied.

The hormone changes were similar across meat and vegetarian diets, reinforcing that the food engineering matters more than the food type.

The Realistic Diet Approach: What Actually Works for Long-Term Change

Here's where most nutrition advice fails: it's not based on how people actually eat. Academic papers recommend Mediterranean diets or DASH diets or plant-based diets, and then everyone abandons them in three weeks because they're too restrictive or too different from their baseline eating patterns.

This research took the opposite approach. Instead of prescribing an ideal diet, researchers used real-world eating patterns as the baseline and minimized the shift needed to achieve health benefits. Participants' baseline diet was typical American food—familiar, accessible, convenient. The intervention diet was the same familiar foods, just without the ultraprocessed versions.

This matters practically. You don't need to learn a new cuisine. You don't need to spend three hours per week on meal prep. You don't need to buy expensive specialty ingredients or visit multiple stores. You need to make relatively simple swaps within the foods you already eat.

If you typically eat pizza, real food means making pizza at home with real cheese and crust, rather than ordering delivery. If you eat pasta, it means whole grain pasta with homemade sauce rather than ultraprocessed sauce from a jar. If you eat breakfast, it means oatmeal with berries rather than flavored instant packets.

The diet was designed to be realistic specifically because researchers understood that sustainable change requires minimal disruption to baseline behavior. You're not changing your entire relationship with food—you're upgrading the quality of foods you already eat.

Both the meat-based and vegetarian diets provided similar health benefits, suggesting that the specific dietary philosophy matters less than the processing level. You can improve your health on a meat-inclusive diet or a vegetarian diet, as long as you're eating real food.

Estimated data suggests a shift to 85% real foods could maintain health benefits while still allowing 15% ultraprocessed foods. This balance supports sustainable dietary changes.

Why Previous Studies Missed This Finding

Before this research, we actually had less clear evidence that reducing ultraprocessed foods produces health benefits independent of other dietary changes. Why? Most feeding studies had major methodological problems.

Some studies compared diets that were almost entirely ultraprocessed with diets containing little to no processed food. While these studies showed dramatic health differences, they didn't reflect real-world conditions. Nobody goes from a typical American diet to a 100% whole-food diet overnight.

Other studies used self-reported dietary data. Participants estimated what they ate, kept food diaries, or answered questionnaires about their typical diet. These methods are notoriously inaccurate. People underestimate calories by 20-40%, misremember portion sizes, and report what they think they should eat rather than what they actually eat.

This research eliminated those variables by providing all food. Researchers knew with certainty what participants consumed. The shift was realistic—65% reduction in ultraprocessed foods rather than 100% elimination. The duration was long enough to see biological changes but not so long that adherence became difficult.

This is why the findings matter. They're not just academically interesting—they translate to real world. If you can achieve similar health improvements with a realistic, moderate reduction in ultraprocessed foods, the pathway to better health becomes much more accessible.

Common Ultraprocessed Foods in Disguise: What to Actually Avoid

Ultraprocessed foods aren't just junk food. Many foods that seem healthy are actually ultraprocessed. If you're going to reduce ultraprocessed foods, you need to identify them.

Flavored yogurts are a classic example. Plain yogurt with fruit is minimally processed. Flavored yogurt with 20 grams of added sugar and a dozen additives is ultraprocessed. The difference is obvious on a nutrition label but not obvious when you see them sitting next to each other in the store.

Whole grain bread can be either. Bread made with just flour, water, salt, and yeast is minimally processed. Bread with 12 ingredients including dough conditioners, emulsifiers, and preservatives is ultraprocessed. Many "whole grain" breads fall into the latter category.

Breakfast cereals vary wildly. Oatmeal is minimally processed. Most commercial cereals are ultraprocessed, even supposedly healthy ones. Check the ingredient list: if it has more than six ingredients, it's probably ultraprocessed.

Flavored instant oatmeal packets are ultraprocessed. Steel-cut or rolled oats with actual fruit added are not. The convenience comes with a processing cost.

Processed meats like hot dogs, deli meat, bacon, and sausage are ultraprocessed. Regular chicken breast or ground beef from a butcher is not. The difference is the additives, curing, and processing used to create shelf stability and specific textures.

Plant-based meat alternatives are often ultraprocessed. They're engineered to mimic meat using texture modifiers, emulsifiers, and various additives. A hamburger patty made from real beef is less processed. A plant-based patty designed to "bleed" is more processed, even if it's technically vegetarian.

Granola and granola bars are usually ultraprocessed, even when marketed as healthy. They typically contain refined grains, added sugar, and various binders and emulsifiers.

Smoothies, when store-bought, are often ultraprocessed despite being marketed as healthy. They contain added sugars, emulsifiers, and stabilizers. Blended whole fruit at home is not.

Salad dressings are frequently ultraprocessed. They contain emulsifiers to keep oil and water mixed, plus added sugars and thickeners. Making dressing from oil, vinegar, and spices at home takes two minutes.

The pattern is clear: if you can make it at home with a small number of real ingredients, it's probably not ultraprocessed. If it requires industrial techniques and additives to exist, it probably is.

Practical Implementation: How to Reduce Ultraprocessed Foods Without Feeling Deprived

Knowing that ultraprocessed foods are bad doesn't automatically translate to better eating. You need specific strategies that work with your life, not against it.

Start with breakfast. This is often the easiest meal to shift from ultraprocessed to real food. Replace flavored instant oatmeal or sweetened cereal with steel-cut oats, add berries, and drizzle with honey. Or eat eggs with toast. Both take about the same time as cereal but provide real food. The satiety improvement alone will make you feel better all morning.

Next, tackle the snacks. Ultraprocessed snacks are convenient, but real-food snacks can be just as convenient. Hard-boiled eggs, Greek yogurt (plain, then add honey), nuts, cheese, fruit, and whole grain crackers with hummus all require zero preparation. They satisfy hunger better than processed snacks.

For lunch, if you typically eat prepared meals or fast food, start making simple lunches at home. Grilled chicken with roasted vegetables and rice takes 30 minutes on a Sunday and gives you five days of lunches. This is faster than many fast food restaurants once you include drive time.

For dinner, use the fact that you probably already cook some meals. Identify your regular meals and improve the processing level. If you eat tacos, use ground beef you season yourself rather than seasoning packets. If you eat pasta, use jarred sauce from ingredients you recognize rather than canned sauce. If you eat burgers, grind your own beef or buy it ground from the butcher.

The swap approach works better than the elimination approach. Don't try to avoid all ultraprocessed foods immediately. Instead, replace one category at a time. Replace your breakfast, keep everything else the same. After two weeks, it becomes automatic, and you swap the next category.

This approach actually aligns with how the research participants ate. They weren't told to overhaul their diet. They were given real food in place of ultraprocessed food. They ate familiar meals—chicken, beef, vegetables, grains—just in non-ultraprocessed forms.

Time investment is minimal if you're strategic. If you cook dinner anyway, cooking real food instead of reheating ultraprocessed meals takes roughly the same time. You're not adding hours to your week—you're just changing what you do during the time you already spend on food.

Cost is actually lower if you optimize. A rotisserie chicken and roasted broccoli costs less than the equivalent fast food meal. Eggs are among the cheapest proteins available. Dry beans and lentils are cheaper than any processed food. The ultraprocessed food industry markets convenience and affordability, but neither is actually true compared to real food if you're efficient.

The Gaps: What Still Isn't Known

The research is compelling, but it's important to recognize its limitations. The study was relatively small—43 participants starting, 36 completing. This limits how confident we can be about the findings, particularly whether they apply equally across different demographics.

The study shows that reducing ultraprocessed foods improves short-term metabolic markers. But it doesn't show whether these improvements prevent or delay disease over years or decades. Do people with improved insulin sensitivity actually develop Type 2 diabetes less frequently? Does reduced inflammation lead to longer lifespan? The research can't answer these questions—longer, larger studies would be needed.

The study provided food for participants, removing real-world barriers like food access, cost, and knowledge about preparation. Researchers haven't yet tested whether people can make these dietary changes in their actual lives without structured support. This is a critical unknown. Can someone living in a food desert with limited income and time actually reduce ultraprocessed foods? Maybe, maybe not. The research doesn't tell us.

Which specific aspects of ultraprocessed foods matter most remain unclear. Is it the additives? The emulsifiers specifically? The extrusion process used to create certain textures? The combinations of these things? Answering these questions would help food manufacturers improve products and help consumers make choices within processed foods.

The research also doesn't tell us whether the benefits come from what people are adding—real food—or what they're subtracting—ultraprocessed foods. Probably it's both, but we don't know the relative importance.

These gaps don't invalidate the findings. They just define the scope and suggest future research directions.

Why This Matters for Aging Well

Healthy aging isn't just about living longer. It's about maintaining independence, mobility, cognitive function, and quality of life. Metabolic health directly enables these things.

When you have good insulin sensitivity, stable blood sugar, low inflammation, and healthy weight, your body has resources to maintain muscle, repair tissues, and function optimally. When you have insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and excessive weight, your body is in constant defensive mode, diverting resources to manage damage rather than maintain function.

This is why the improvements in the research matter beyond the numbers. The participants who reduced ultraprocessed foods weren't just losing weight or improving a lab value. They were restoring metabolic function that directly determines health span—the years you live in good health rather than declining health.

The improvements happened without restrictive dieting, without intensive exercise programs, without supplements or medications. Just food. Better food. This is within reach for almost anyone, regardless of income, education, or access to medical care.

The research also suggests that waiting until you have a disease diagnosis to change eating patterns might be too late. The metabolic improvements happened in eight weeks. But preventing the metabolic damage in the first place through decades of eating real food is even better. This is relevant not just for older adults but for anyone who will eventually be older.

The Future: Can This Scale Beyond the Study?

One critical unanswered question: can these results scale? Can people maintain these improvements outside the research setting where someone else isn't preparing meals?

There's reason to be cautiously optimistic. The study used realistic foods and a realistic shift—not elimination, just reduction. The improvement happened without willpower-dependent restriction. The foods were familiar, not exotic. These factors suggest that adherence might be possible in real life.

But barriers certainly exist. Food marketing aggressively pushes ultraprocessed products. Most fast food and restaurant food is ultraprocessed. Ultraprocessed foods are typically cheaper and more convenient than real food at the moment of purchase, even if not overall. Changing eating patterns requires habit change, which is always difficult.

What might help? Understanding that you're not restricting or dieting—you're upgrading. Convenience isn't gone, it's just different convenience. The time to cook real food isn't much different than the time to drive through a drive-through or unpack prepared meals. The cost difference, when honestly calculated, favors real food.

Education helps. Many people genuinely don't know how to cook basic meals. If cooking skills become more common, dietary changes become easier. Cooking classes, recipe simplification, and accessible instructions could all help.

Food environment changes would help tremendously. If real food were as available and marketed as heavily as ultraprocessed food, the choice becomes easier. This is a systems-level change that's beyond individual responsibility.

But the research proves that the change is possible and produces real benefits. That's valuable whether or not everyone makes it.

Key Takeaways and Next Steps

The research is clear: older adults can improve metabolic health by reducing ultraprocessed foods without making extreme dietary changes. The improvements happen relatively quickly—within weeks—and affect multiple biological systems that determine health span and quality of life.

The shift doesn't require elimination of favorite foods, just upgraded versions. It doesn't require calorie restriction or intensive exercise. It works regardless of whether you eat meat or follow a vegetarian diet—the processing level matters more than the specific foods.

If you're over 65 and dealing with weight gain, metabolic challenges, or age-related health issues, this research offers a practical pathway forward. You don't need a complete lifestyle overhaul. You need better food.

Start small. Pick one meal to upgrade. Notice how you feel. Notice that you're fuller on less food, that energy is more stable, that digestion improves. These immediate benefits make continued change easier.

Talk to your doctor if you have existing health conditions or take medications that might be affected by dietary changes. Share this research with them. Improving insulin sensitivity and reducing inflammation often reduces medication needs—something your doctor should monitor.

Understand that this isn't a diet. Diets are temporary. This is dietary upgrade—a permanent shift toward food that nourishes rather than dysregulates your body. Once you make it, you typically don't want to go back. The feeling difference alone drives continued adherence.

The research proves that healthy aging isn't dependent on genetics or luck. It's dependent on decisions you make daily. Food is the most important of those decisions.

FAQ

What exactly are ultraprocessed foods and how do they differ from regular processed foods?

Ultraprocessed foods are manufactured using industrial techniques and contain ingredients not typically used in home cooking, including additives like emulsifiers, artificial flavorings, colors, and preservatives. Regular processed foods—like canned beans or whole wheat bread—can be made at home and contain recognizable ingredients. The key distinction is whether you could theoretically make the food yourself; if you can't, it's likely ultraprocessed. Most packaged snacks, ready-to-eat meals, flavored cereals, and processed meats are ultraprocessed, while whole foods and minimally processed versions of staples are not.

How quickly will I see health improvements from reducing ultraprocessed foods?

The research showed measurable improvements in metabolic markers within eight weeks of reducing ultraprocessed foods to less than 15% of total calories. However, most people notice subjective improvements—better energy, reduced hunger, improved digestion—within just two to three weeks. These earlier benefits often motivate continued adherence, while the deeper metabolic improvements accumulate over months and years. The key is that this isn't a slow process; real change happens relatively quickly.

Can I still eat some ultraprocessed foods occasionally while maintaining health benefits?

Yes. The research showed benefits at 15% ultraprocessed foods, not zero. This means you can include some processed foods—occasional fast food, packaged snacks, or convenience foods—while still achieving significant health improvements. Complete elimination isn't necessary. The dose-response suggests that reducing from the typical 50%+ to 20-30% produces meaningful improvements. The 15% level in the study was chosen as realistic and achievable, not as a minimum requirement.

Is this dietary change more important than exercise for healthy aging?

Both matter, but the research focused solely on dietary changes and found significant improvements without exercise changes. Food quality likely has a larger impact on metabolic health, weight, and inflammation than exercise level, though this doesn't mean exercise isn't important. The research specifically showed that metabolic improvements happened without participants being asked to change physical activity, suggesting that diet is the primary lever for the health outcomes measured. However, combining improved diet with exercise would likely produce even better results.

How much does it cost to eat real food instead of ultraprocessed foods?

Real food is typically cheaper than ultraprocessed food when honestly compared. A rotisserie chicken costs less than fast food equivalent calories. Eggs are among the cheapest proteins. Dried beans and lentils cost less than processed foods providing similar nutrition. The ultraprocessed food industry markets convenience and affordability but neither is actually true when you account for preparation time and nutritional value. Initial perception of cost is higher because preparation is your own, but actual money spent is typically lower.

Does this dietary approach work for specific health conditions like diabetes or heart disease?

The research specifically tested improvements in insulin sensitivity and cholesterol levels, both critical for managing and preventing Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The improvements were substantial enough that they likely reduce disease risk significantly. However, if you have diagnosed conditions, you should work with your healthcare provider before making major dietary changes, as improved metabolic markers sometimes allow medication reduction. The research proves that the dietary approach improves the underlying biological abnormalities that drive these diseases.

What if I don't have time to cook or live in a food desert with limited real food access?

This is a legitimate barrier the research didn't directly address. However, real food doesn't always require cooking. Rotisserie chicken, bagged salads, pre-cut vegetables, plain yogurt, nuts, and fruit require no preparation. Many of these are available in convenience stores. Additionally, learning a few simple meals—rice and beans, pasta with jar sauce from basic ingredients, scrambled eggs with toast—takes minimal time. If genuine food access is limited, advocacy for better food environments is important, but individual dietary improvements are still often possible.

Will these improvements continue indefinitely, or do they plateau?

The research measured eight-week changes but didn't test longer duration. Typically, initial improvements in metabolic markers continue for months if dietary changes are maintained. Some plateauing likely occurs as your body adapts to the new metabolic state. However, the sustained benefits of avoiding inflammation, maintaining insulin sensitivity, and supporting healthy weight are ongoing. Long-term adherence is necessary to maintain improvements, but the changes don't require increasing effort—they're simply sustained with continued dietary choices.

Can younger people benefit from reducing ultraprocessed foods, or is this only for older adults?

While the research specifically tested older adults, the biological mechanisms—reducing inflammation, improving insulin sensitivity, supporting satiety hormones—apply across all ages. Younger people likely benefit even more because they haven't yet accumulated decades of metabolic damage. Preventing insulin resistance and chronic inflammation early is probably better than fixing them later. The ultraprocessed food problem is more severe in younger people than in previous generations, suggesting that dietary improvement is increasingly important across all age groups.

How do I know if a food is ultraprocessed when shopping?

Read the ingredient list, not just the nutrition label. If a food has more than five ingredients or contains words you wouldn't use in home cooking—emulsifiers, modified starch, artificial flavors, dextrose, sodium phosphate—it's likely ultraprocessed. If you can make the food at home with a small number of real ingredients, it's not ultraprocessed. Price can be a clue too; real food is often cheaper than the ultraprocessed version. Over time, you'll develop intuition, but the ingredient list never lies.

Conclusion: Your Metabolic Future Is Still Yours to Determine

Aging is inevitable. Metabolic decline isn't. The research proves this consistently: what you eat determines how well your metabolism functions, and metabolic function determines quality of life, independence, and longevity.

The encouraging finding isn't that you should eat perfectly or restrict yourself dramatically. It's that meaningful improvement comes from reasonable dietary shifts. Moving from 50% ultraprocessed to 30% or 15% produces measurable health benefits. You don't need to be extreme to see real results.

This matters most because it's achievable. You're not waiting for a medication that doesn't exist or hoping that genetics work in your favor. You're making choices available to you right now. Food you can buy or grow. Meals you can prepare or learn to prepare. Habits you can change one meal at a time.

The study participants were representative of many Americans—older, dealing with weight and metabolic challenges, eating typical American food. They saw real improvements. Not because they're exceptional or unusually motivated, but because they upgraded what they were eating. That same upgrade is available to you.

Start today. Not perfectly. Not all at once. Just better. Add one real-food meal. Replace one ultraprocessed snack. Notice how it feels. Build from there.

Your metabolic future isn't determined by age or genetics alone. It's determined by the thousands of eating decisions you make. This research shows what those decisions can produce: weight loss, better metabolic health, improved inflammation, stronger appetite regulation, and genuine improvements in the biological markers that determine healthy aging.

You don't need permission. You don't need an ideal diet plan. You just need to eat real food more often than you eat ultraprocessed food. That's it. That's the change that produces real results.

The future you'll thank current you for making that shift.

Related Articles

- CES 2026 Bodily Fluids Health Tech: The Metabolism Tracking Revolution [2025]

- 7 Walking Styles for Fitness: Rucking to Japanese Walking [2025]

- Magnesium Supplements Complete Guide [2026]: Benefits, Types & Science

- Withings Body Scan 2: The Ultimate Smart Scale for Longevity Tracking [2026]

- How Poor Sleep Accelerates Brain Aging: Science & Prevention [2025]

![Avoiding Ultraprocessed Foods for Healthier Aging [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/avoiding-ultraprocessed-foods-for-healthier-aging-2025/image-1-1768234084082.jpg)