Boston Dynamics Atlas Production Robot: The Enterprise Transformation Begins [2025]

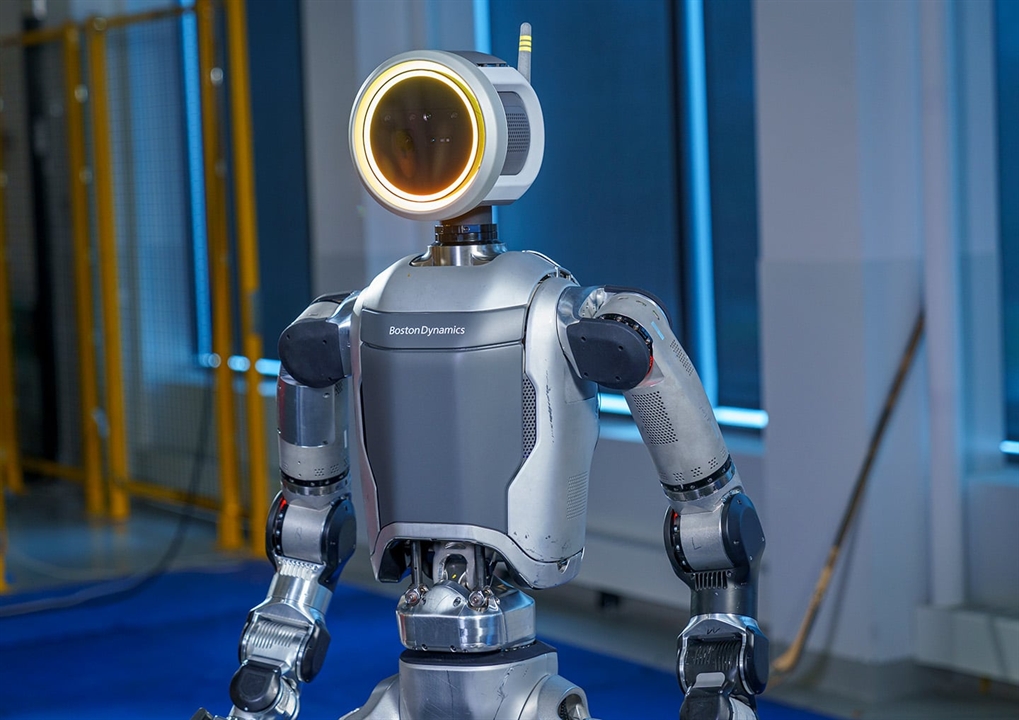

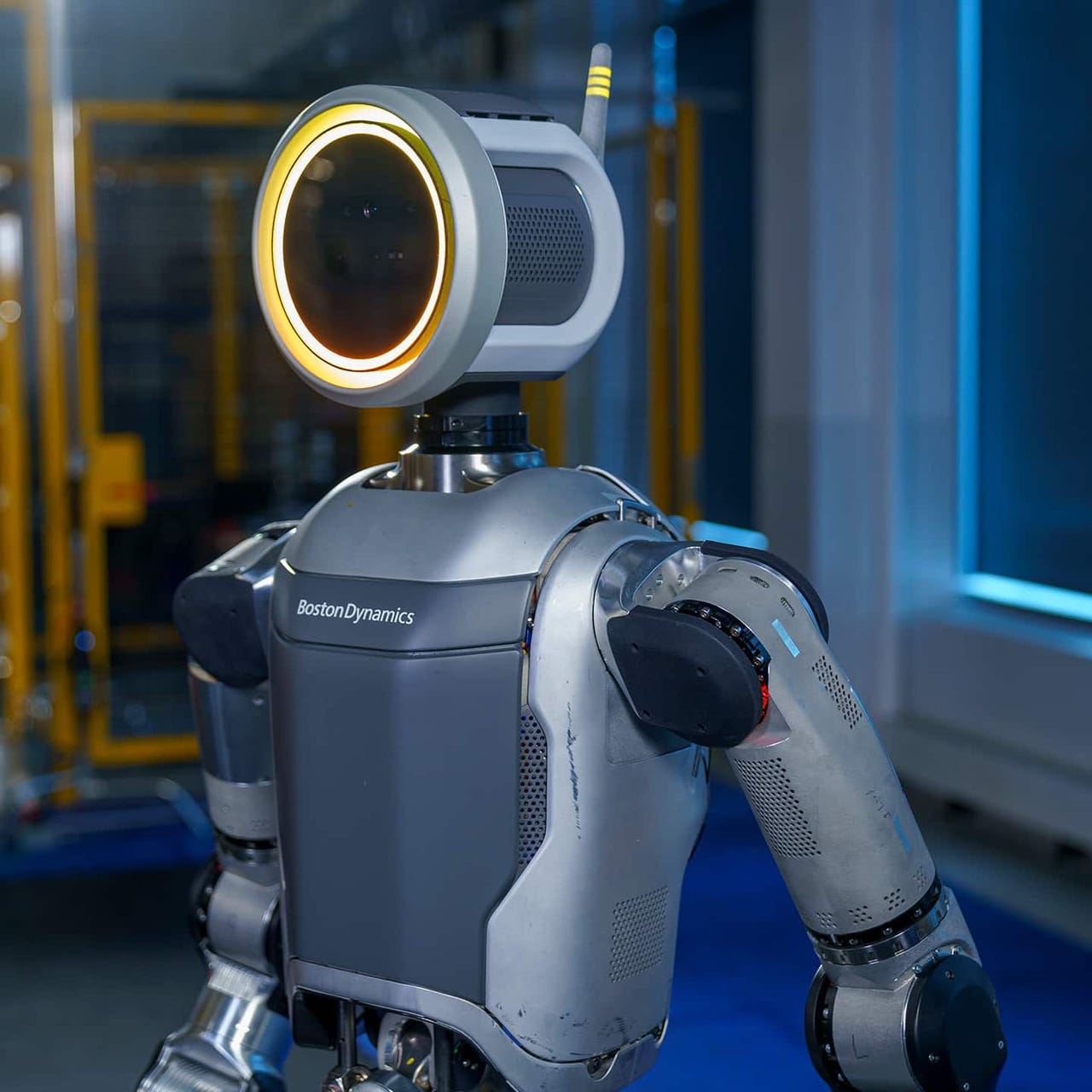

When Boston Dynamics unveiled its production-ready Atlas robot at CES 2026, it wasn't just another technology announcement. It marked the moment when decades of robotics research stopped being a fascinating demo and started becoming a genuine industrial solution. And honestly, the implications are enormous.

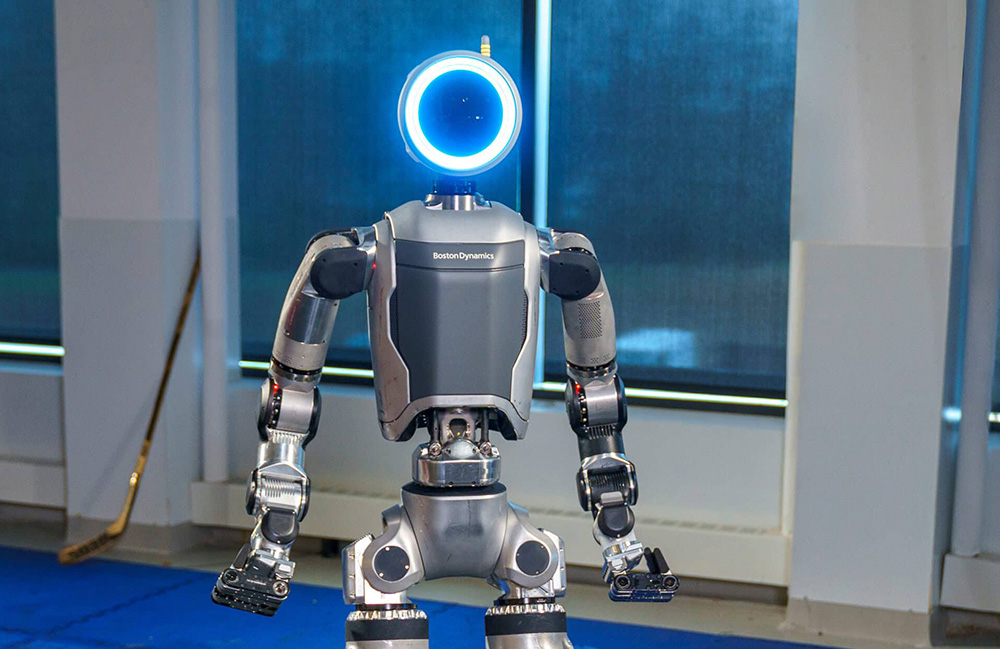

For years, Boston Dynamics built robots that could dance, parkour, and perform acrobatics. Engineers filmed them doing backflips and posted the videos online. The world watched, fascinated and slightly unsettled. But underneath all that showmanship was relentless engineering. Every movement, every sensor, every algorithm was being refined toward one goal: building a robot that could actually work.

Now it's happening. The final enterprise version of Atlas is rolling off production lines, heading first to Hyundai's manufacturing facilities and Google Deep Mind's research labs. This isn't a prototype. This isn't a limited release. This is the beginning of humanoid robots in the industrial workforce, and the manufacturing world is about to change in ways we're only starting to understand.

The scale of what's about to happen is worth stopping to think about. Manufacturing is one of the most resource-intensive, labor-dependent industries on Earth. Factories employ millions of people performing repetitive tasks, heavy lifting, and precision work. If Atlas can genuinely handle even a fraction of these tasks reliably, the economic consequences ripple through everything: job displacement, wage pressure, supply chain transformation, and entirely new categories of work that don't exist yet. This isn't hype. This is a genuine inflection point.

But before diving into the implications, let's understand what Boston Dynamics actually built, why it matters, and what comes next.

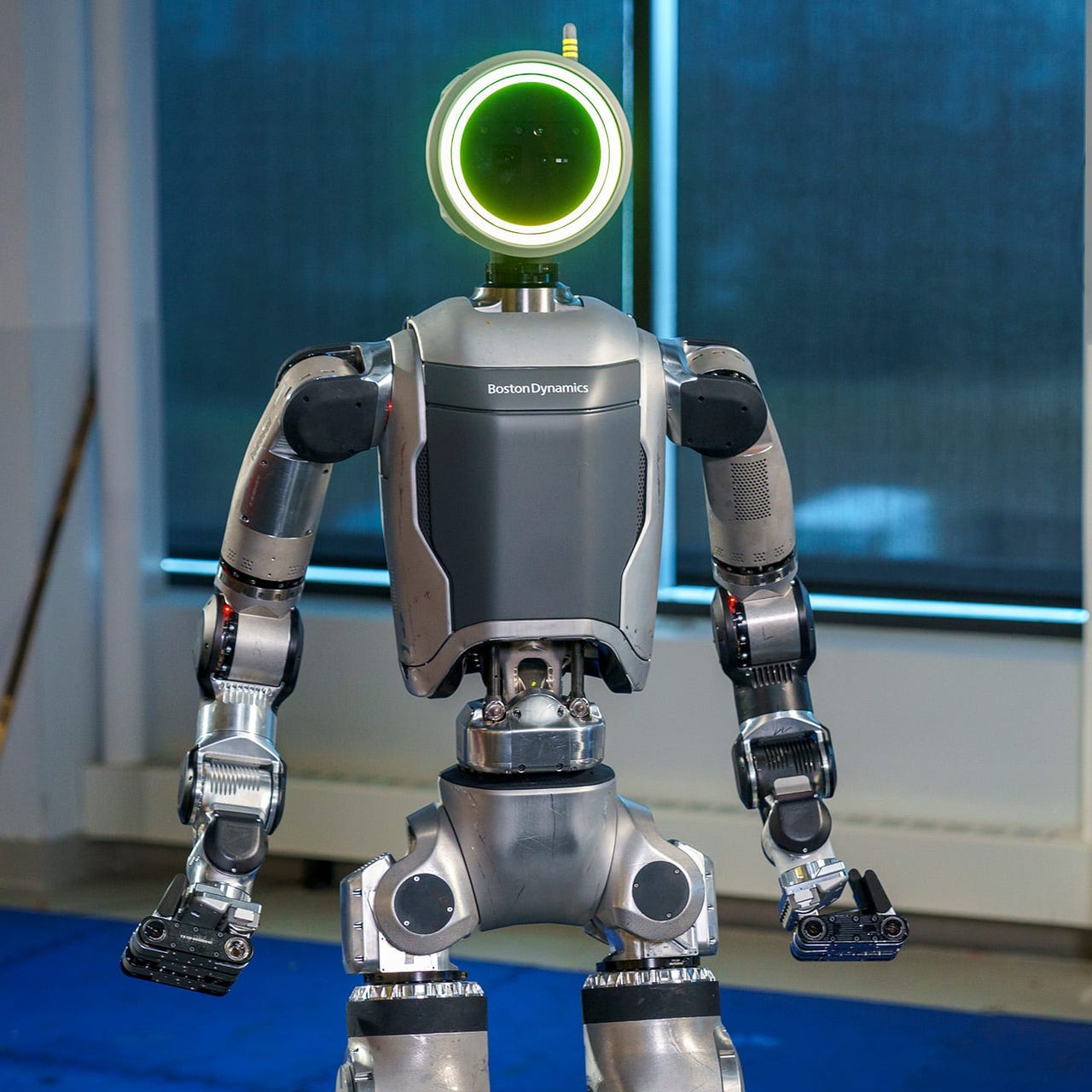

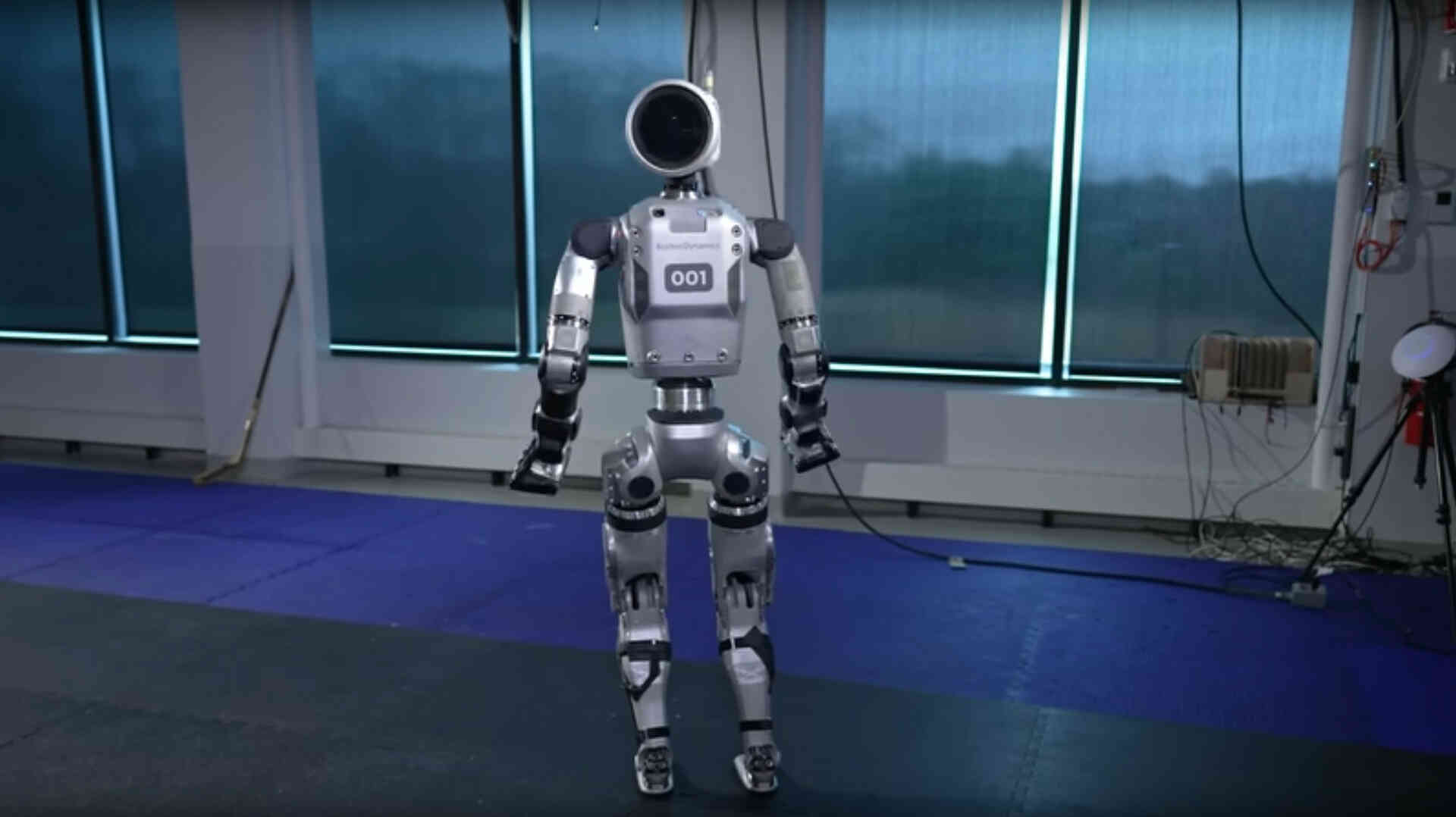

What Makes the Production Atlas Different From Earlier Versions

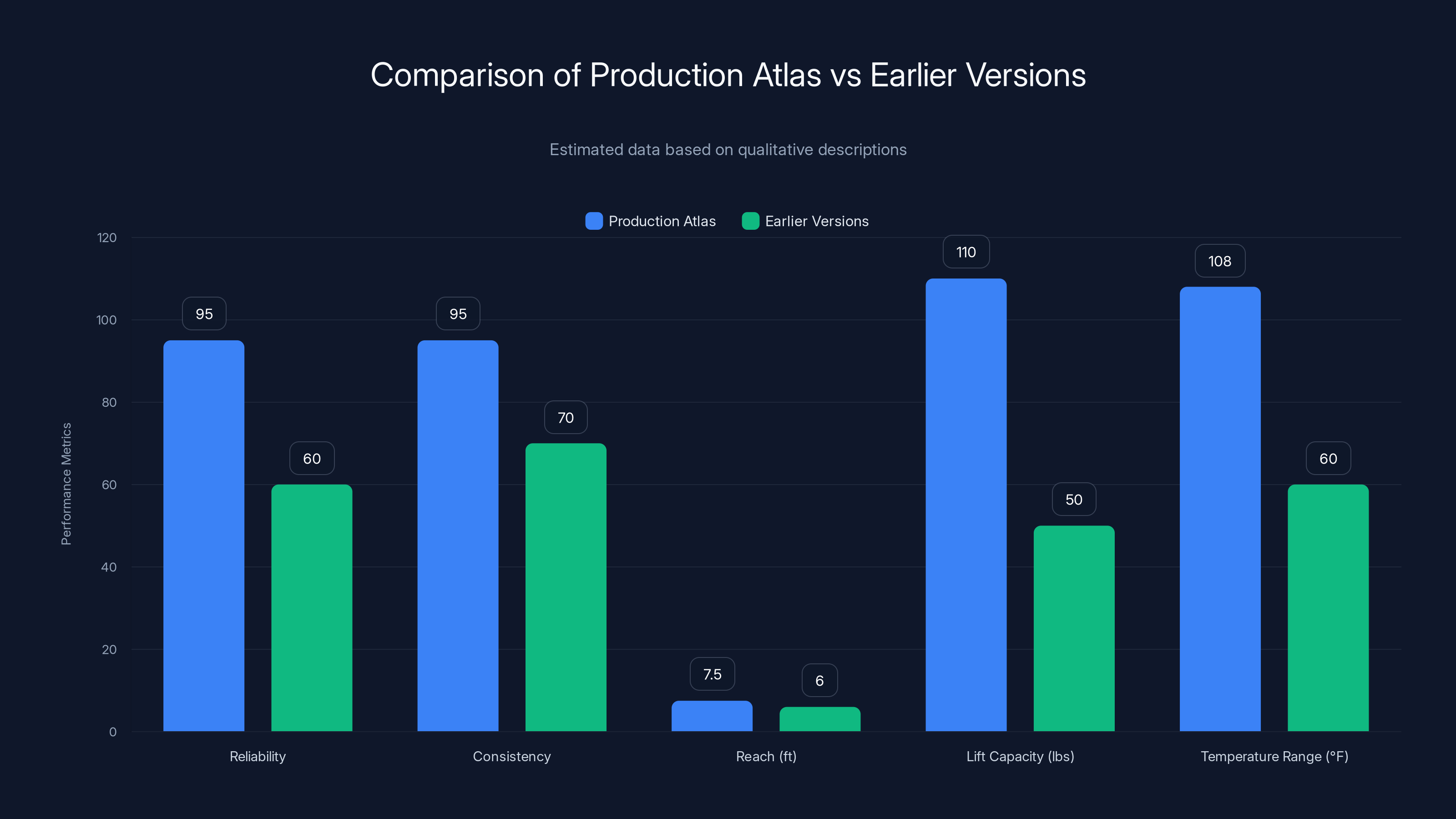

Boston Dynamics has been building humanoid robots for years. The earlier Atlas versions became famous for their stunts. But a robot that can do a backflip is fundamentally different from a robot that can perform the same task correctly 10,000 times in a row, in varying conditions, without breaking.

The production Atlas was engineered from the ground up with industrial reliability as the core principle. This shifts almost everything about how the robot was designed.

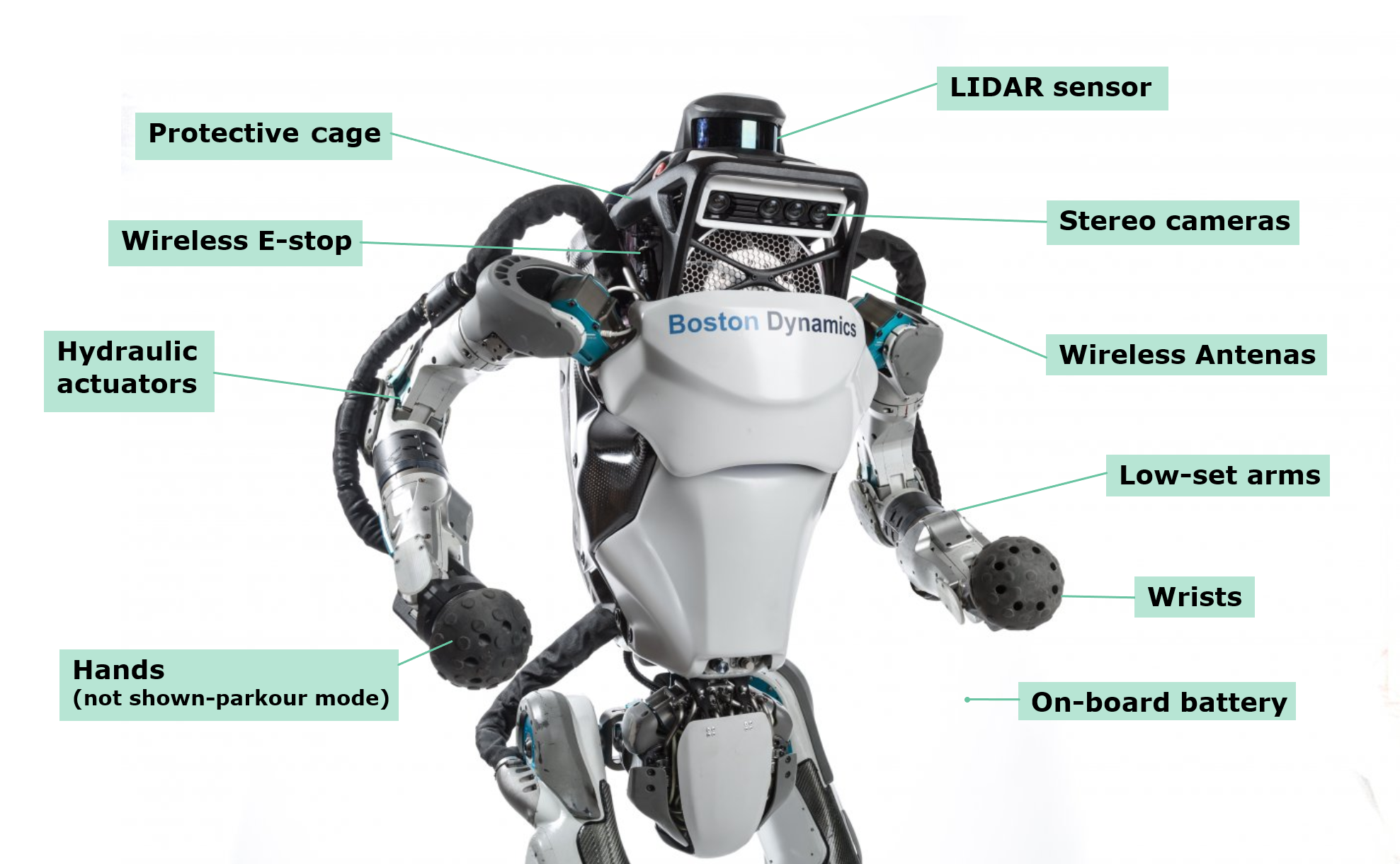

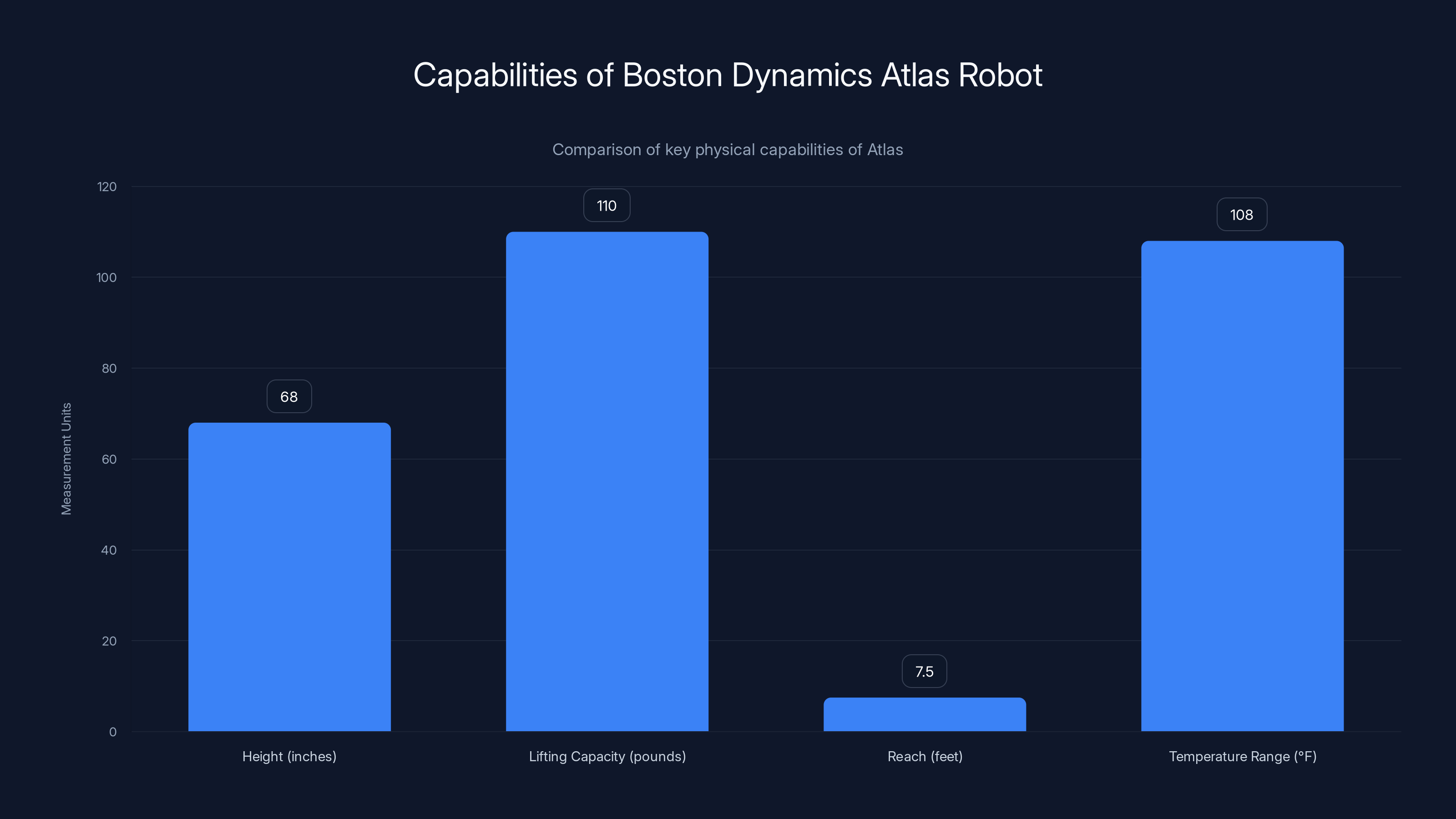

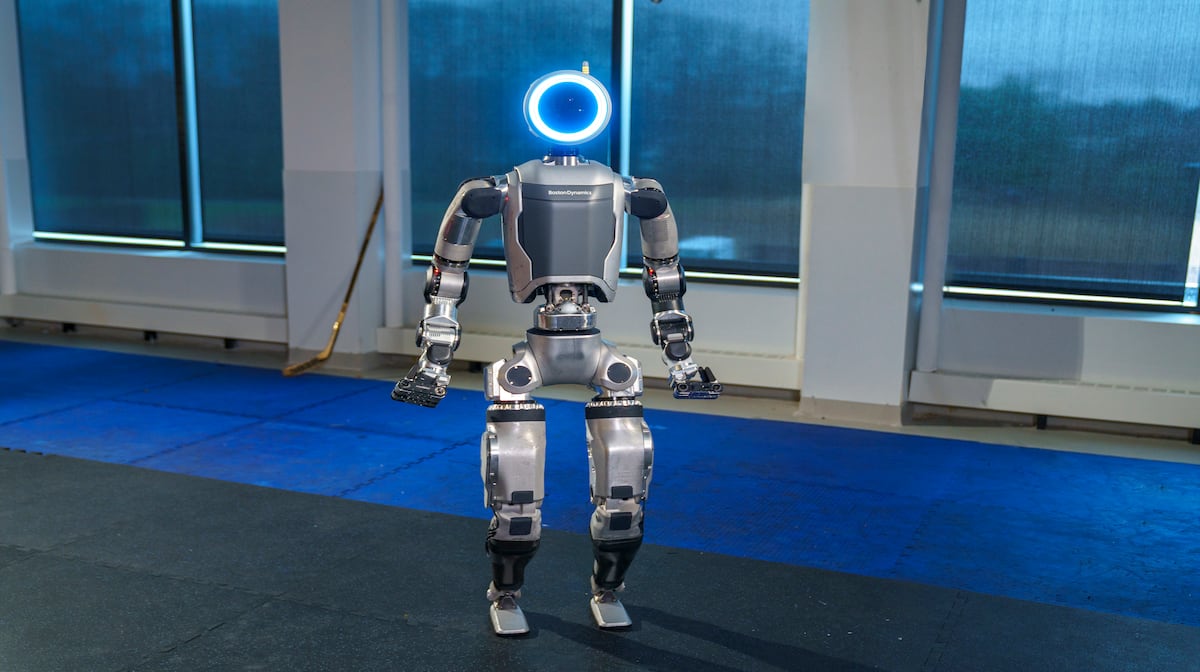

Consider the specifications. The new Atlas has a reach of up to 7.5 feet, which is important because it means the robot can work at human heights without constantly repositioning. It can lift 110 pounds with consistency, which covers a massive range of manufacturing tasks without requiring specialized heavy-duty variants for every single application. The temperature range of minus 4 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit matters more than it sounds. Manufacturing facilities vary wildly in temperature. Some sections of a modern factory floor are climate-controlled. Others aren't. The robot needs to function reliably in both.

But the real difference is consistency. Earlier Atlas versions were research platforms. Engineers would tweak them, optimize them, adjust tolerances. The production version was engineered for repeatability. Every unit that rolls off the assembly line needs to perform identically to the one that came before it. This requires standardized components, proven manufacturing processes, and quality control systems that robotics companies don't always emphasize.

The production Atlas also represents a shift in how Boston Dynamics thinks about deployment. Earlier versions required deep technical expertise to operate and maintain. The new version was designed with what Boston Dynamics calls "a tablet steering interface," meaning factory workers with standard training can control it. This is crucial. It means adoption doesn't require hiring robotics Ph Ds. It means existing manufacturing staff can learn to work alongside these systems.

The robot can also operate three different ways: fully autonomous, with a human teleoperator, or via that tablet interface. This flexibility is important. Some tasks might be too complex for full autonomy initially. Some might require occasional human intervention. The tablet interface provides that middle ground where the robot handles 95% of the work but humans stay in the loop for edge cases.

Boston Dynamics' CEO Robert Playter called it "the best robot we have ever built," and that's not marketing speak. It's a genuine statement about engineering progress. The company has learned from years of testing, from thousands of hours of the robot operating in varied conditions, from the constant feedback loop of research and refinement. All that learning is baked into this production version.

Boston Dynamics Atlas is designed for industrial tasks, with a height of 68 inches, a lifting capacity of 110 pounds, a reach of 7.5 feet, and operational temperature range from -4 to 104°F.

Hyundai's First-Mover Strategy: Manufacturing at Scale

Hyundai isn't just investing in Boston Dynamics because it's a shareholder. The automotive company has a specific, urgent problem that Atlas might solve. Car manufacturing is one of the most complex manufacturing endeavors on Earth. A modern car has thousands of parts that need to be assembled with precision, speed, and reliability. It's also one of the most competitive industries. Hyundai's margins depend on production efficiency.

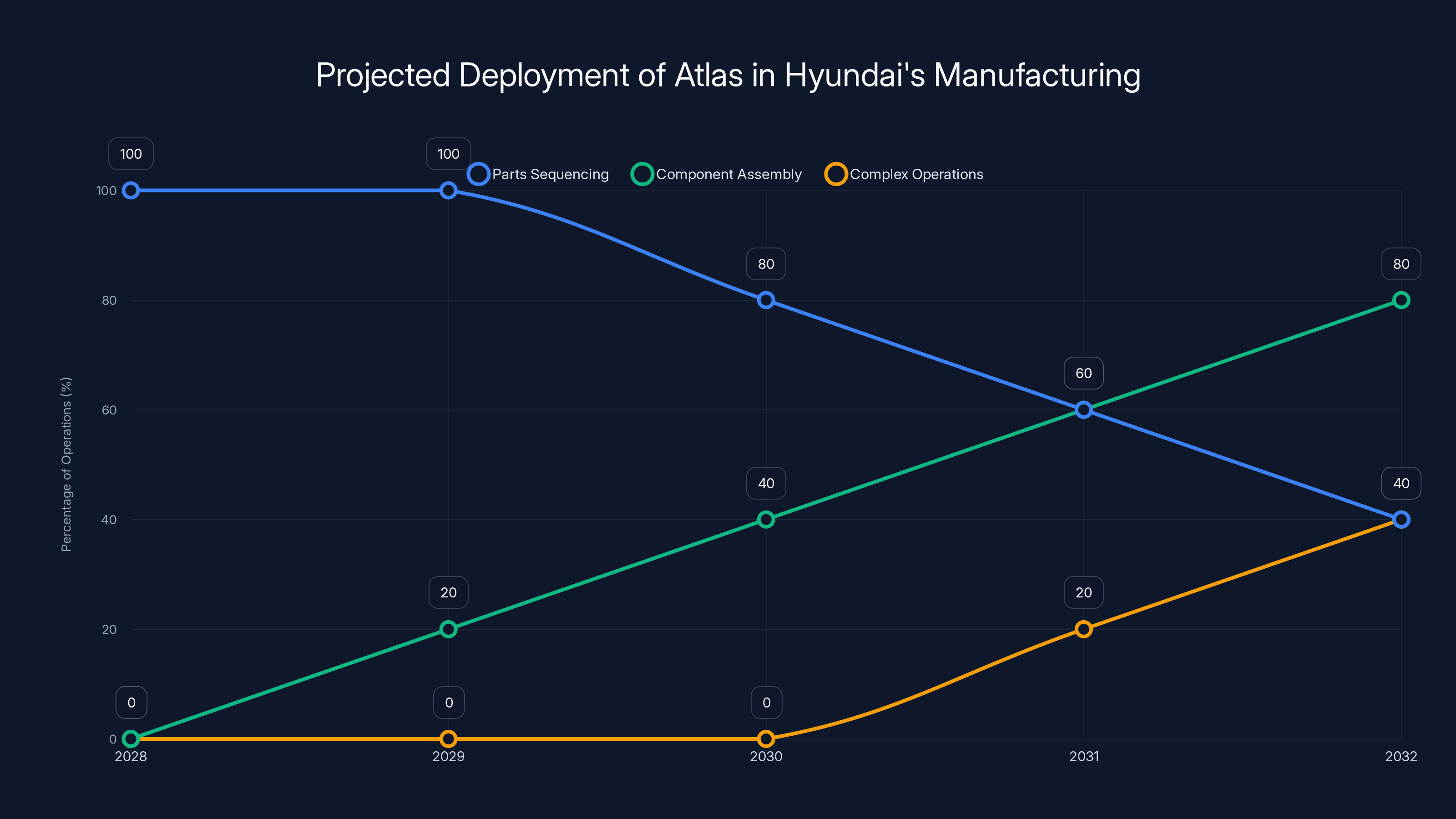

Hyundai's announcement is remarkably specific. The company plans to deploy Atlas in its car plants starting in 2028. The initial focus is parts sequencing, which sounds mundane but is crucial. In manufacturing, getting the right part to the assembly line at the right moment is a constant logistical challenge. Too early and parts clutter the workspace. Too late and the assembly line stops. Humans currently do this. It's repetitive, physical work that robots theoretically excel at.

Then Hyundai outlines a progression. By 2030, the company expects to move Atlas from parts sequencing to component assembly. This is substantially more complex. Assembly requires precision, adaptability, and decision-making. Different cars require different assembly sequences. Parts might have minor variations. The robot needs to notice these differences and adapt its approach.

Over time, Hyundai envisions Atlas taking on what the company calls "repetitive motions, heavy loads, and other complex operations." Translation: more of the actual manufacturing work. This progression makes sense. You don't deploy new technology to your most critical operations immediately. You start with the parts that are well-understood, that have clear metrics for success, and that give the system time to prove itself before moving to more complex tasks.

What's interesting about Hyundai's timeline is that it's realistic but also ambitious. 2028 is two years away from the announcement. That's enough time to build out the integration, train staff, work through teething problems, but not so far in the future that the timeline loses credibility. By 2030, we're talking about substantial deployment. That's four years from now, which is reasonable for a technology transition of this magnitude.

For Hyundai, the calculus is clear. If Atlas can even partially automate parts sequencing and assembly, the company gains enormous competitive advantage. Labor costs are rising globally. Manufacturing facilities are competing across borders. A robot that can work 24/7 without fatigue, that doesn't require healthcare benefits or retirement planning, that can be quickly adapted to new tasks, represents a genuine economic advantage.

But Hyundai is also betting that Atlas will keep improving. Boston Dynamics doesn't stop development at production launch. The company will continue refining the system, improving autonomy, expanding capabilities. Hyundai gets access to these improvements as they happen. The manufacturer isn't just buying a product. It's gaining a partner in manufacturing transformation.

There's also a deeper strategic angle. Hyundai is one of Boston Dynamics' majority shareholders. This isn't just customer acquisition. It's a vertically integrated bet. Hyundai helps drive product development by providing real-world feedback. Boston Dynamics benefits from Hyundai's manufacturing expertise. The relationship works in both directions.

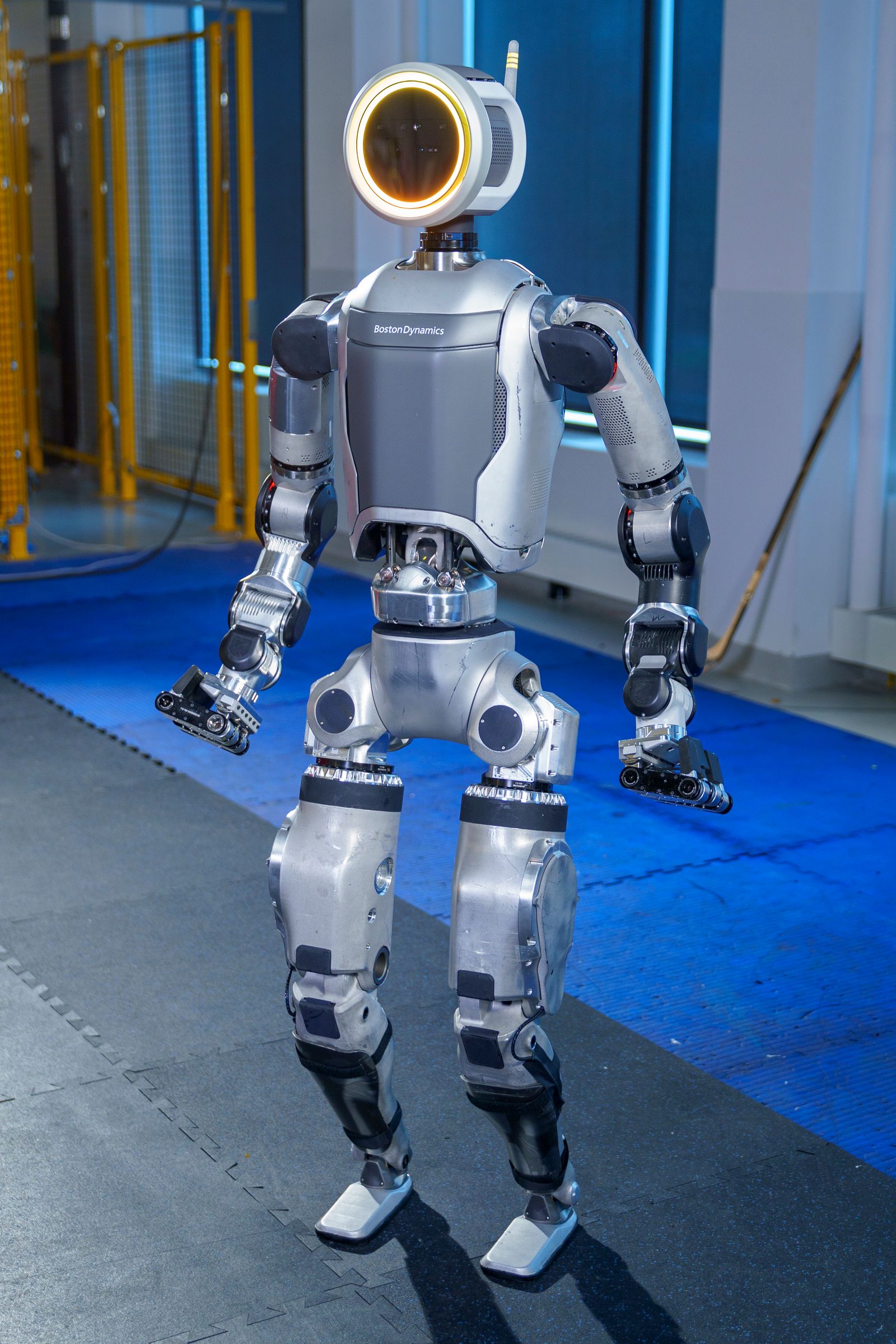

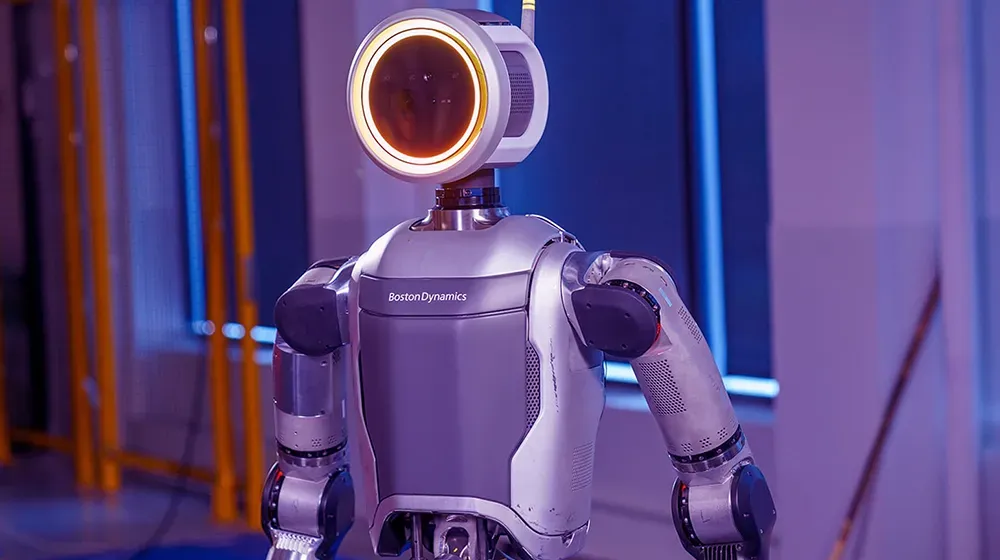

The Production Atlas shows significant improvements in reliability and consistency, with enhanced reach and lift capacity, making it more suitable for industrial applications. (Estimated data)

Google Deep Mind's AI Integration: The Brains Behind the Robot

Google Deep Mind's involvement with Atlas represents something different than Hyundai's. While Hyundai is focused on deployment and manufacturing optimization, Deep Mind is focused on capabilities and intelligence.

Deep Mind is receiving Atlas robots specifically to work on integrating its Gemini Robotics AI foundation models. Let's break down what that actually means, because it's the more complex part of the puzzle.

Geometry, physics, and decision-making are three different problems. Geometry is about understanding space. Where is the object? What's the distance? What's the path? Physics is about predicting how the world works. If I move this object, what happens? Will it fall? Can I hold it? Decision-making is about planning. Given the current situation, what should I do next?

Traditional robotic systems use hard-coded rules for all three. Engineers write the physics models. Engineers define the decision trees. This works but it's brittle. It breaks when you encounter situations that weren't anticipated during programming.

AI foundation models take a different approach. Rather than hard-coded rules, they learn patterns from data. A foundation model trained on millions of examples of robotic manipulation learns that certain configurations are stable and others aren't. It learns that certain sequences of actions accomplish tasks. It develops intuition about how the world works, similar to how humans develop intuition.

Geometry Robotics is Google Deep Mind's approach to integrating these foundation models into actual robotic systems. The goal is to give Atlas a kind of artificial intuition about physical tasks. Rather than programming every movement, you give the robot high-level objectives. Grab the part. Assemble this component. The robot uses its foundation model to figure out how.

This is incredibly important because it dramatically expands what robots can do. Hard-coded systems can do Task A perfectly but they're helpless with Task B unless someone reprograms them. AI-integrated systems can adapt to Task B if it's similar enough to tasks they learned from. This adaptability is what makes robotics genuinely useful in manufacturing, where tasks are never entirely identical.

Deep Mind's involvement signals that Google is betting on AI-integrated robotics as a massive category. The company isn't just investing in Boston Dynamics. It's positioning itself as the AI provider for robotic systems. If Geometry Robotics works as intended, every humanoid robot will eventually need these kinds of foundation models. Google wants to provide them.

The partnership also makes strategic sense for Deep Mind. The organization has been somewhat distant from commercial applications, focused on research and capability development. But robotics is where AI research meets real-world problems. By working with Boston Dynamics' Atlas, Deep Mind gets real-world feedback on its AI systems. The foundation models get tested in actual manufacturing conditions with real-world variation and complexity. This accelerates development in ways that pure research can't.

The Technical Specifications: Why These Numbers Matter

Let's dig into what the Atlas specifications actually tell us about the engineering approach.

A reach of 7.5 feet is deliberately chosen. It's tall enough to reach manufacturing equipment at various heights but not so tall that the robot becomes unstable or difficult to control. Manufacturing equipment is optimized for human workers, who are generally 5.5 to 6.5 feet tall. A 7.5-foot reach means the robot can work at human heights plus some additional reach, covering most equipment layouts without requiring specialized redesign.

The 110-pound lifting capacity is interesting because it's not maximum strength. Humanoid robots can be engineered to lift much more. But 110 pounds is chosen because it's the maximum safe load for humans to lift repeatedly without risk of injury. This gives you a direct baseline for comparison. Tasks that humans currently do while lifting 110 pounds are good candidates for Atlas deployment. Tasks requiring heavier lifting would still use specialized equipment or require redesigned workflows.

The temperature range of minus 4 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit is practical but also conservative. Most manufacturing facilities operate between 60 and 75 degrees Fahrenheit. Minus 4 degrees covers outdoor loading docks and heated storage areas. 104 degrees covers hot manufacturing areas near furnaces or assembly lines. The range isn't cutting-edge, but it's comprehensive for typical manufacturing environments.

Battery life isn't mentioned in the specifications, but it's critical. The robot needs to work shifts comparable to human workers. Most manufacturing shifts are 8 to 12 hours. A robot that needs to recharge every 2 hours is impractical for shift-based manufacturing. The fact that Boston Dynamics doesn't publicize battery life suggests it's probably in the 6-12 hour range, but we'll know more when customers start deploying.

The three operational modes (autonomous, teleoperator, tablet interface) represent a carefully engineered flexibility spectrum. Fully autonomous is the most efficient but requires the most trust and the most sophisticated AI. Teleoperator is safest but requires constant human attention. The tablet interface is the practical middle ground where the robot handles routine tasks and humans guide it for exceptions.

The fact that CEO Robert Playter explicitly called it "the best robot we have ever built" deserves attention. This isn't hyperbole. It reflects genuine engineering progress. Every version of Atlas from the early prototypes to this production model taught the company something. Thousands of hours of operation provided data on what works, what fails, what needs redesign. All that learning is compressed into this one system.

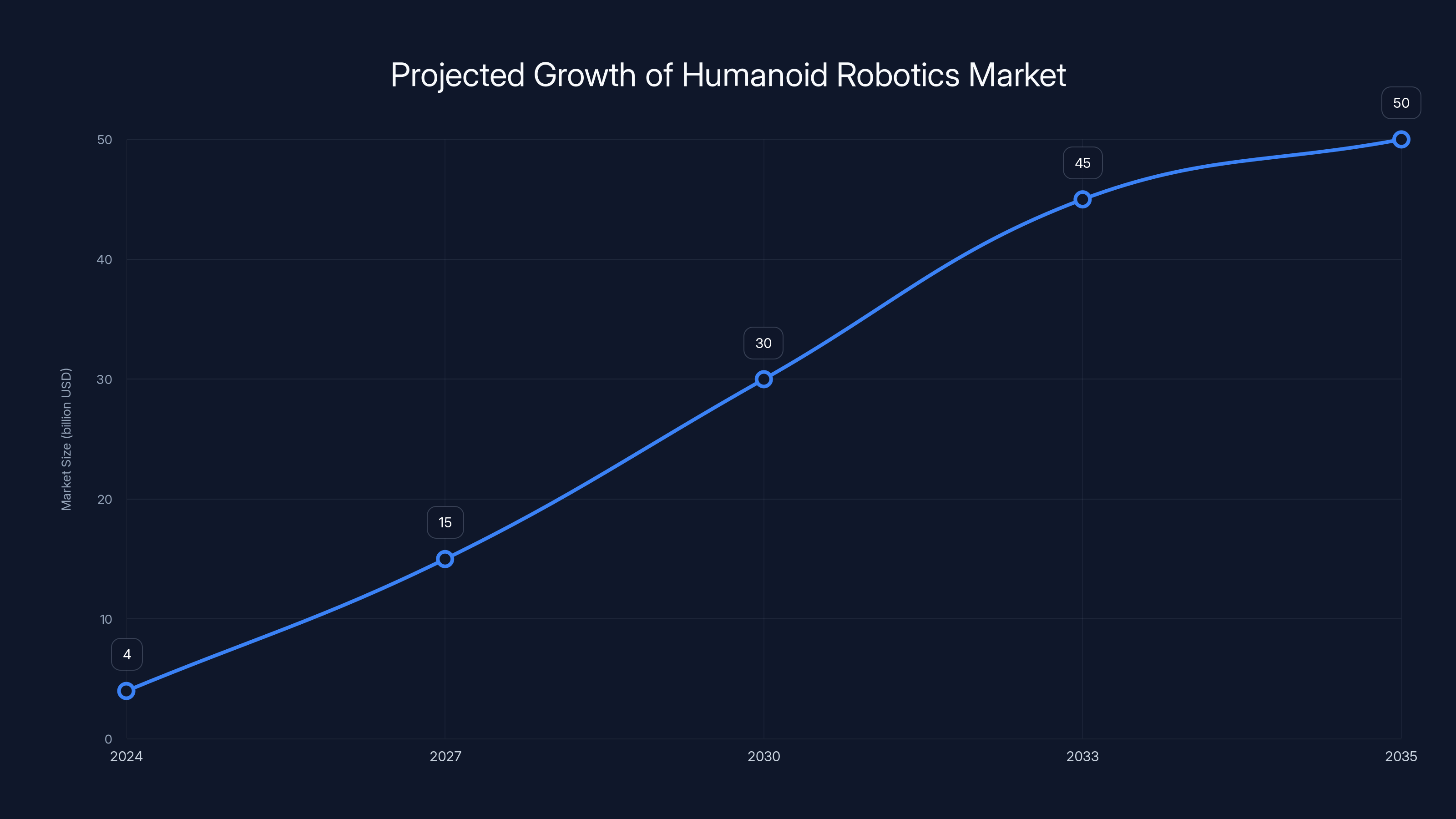

The humanoid robotics market is projected to grow significantly, from

The Manufacturing Revolution: What This Means for the Industry

The deployment of Atlas into real manufacturing is a genuine inflection point for the industry. Manufacturing hasn't had a labor-replacing technology this fundamental since the assembly line was invented. And the implications extend far beyond Hyundai's factories.

Consider the current manufacturing landscape. The industry is under enormous pressure. Labor costs are rising globally. Supply chains are stressed and fragmented. Quality standards are increasing. Demand for customization is growing, which makes standardized manufacturing more difficult. Profit margins are being squeezed from every direction.

Humanoid robots like Atlas offer a way to address multiple problems simultaneously. They reduce labor costs by replacing humans in dangerous, repetitive, physically demanding tasks. They improve quality by eliminating human fatigue and error. They increase flexibility because (in theory) the same robot can be retrained for different tasks without hardware redesign. They work 24/7 without fatigue, holidays, or sick days.

The economic math is compelling. An industrial robot costs roughly

But there's a subtlety here that often gets overlooked. Robots don't fully replace humans in manufacturing. They change what humans do. Someone needs to reprogram the robot when tasks change. Someone needs to maintain it. Someone needs to handle the parts that don't work correctly. Someone needs to make decisions when situations exceed the robot's capabilities.

The real revolution isn't that robots replace humans. It's that manufacturing becomes more efficient, and the humans who remain are doing higher-value work. The parts sequencing job that someone does for eight hours a day gets automated. That person gets trained to handle robot maintenance or quality control, work that's more engaging and usually better paid.

Hyundai's timeline is worth thinking about in this context. The company isn't deploying Atlas across all factories in 2028. It's starting in specific plants with specific tasks. This gives the company time to understand how the robot works, what the actual maintenance and programming requirements are, and what the real cost per unit manufactured looks like. It's not a bet-the-farm approach. It's a careful, staged deployment that lets the company learn.

This approach also signals something important to competitors. Hyundai is publicly committing to robotics integration. Other car manufacturers will see the results. If Hyundai gains even modest efficiency improvements, competitive pressure will force others to follow. The industry will move toward robotics integration not because any individual company thinks it's optimal, but because staying competitive demands it.

Google's AI Strategy: The Brains of Tomorrow's Robots

Google Deep Mind's involvement deserves deeper analysis because it reveals the company's long-term strategy in robotics.

Google has been investing in robotics for years through various initiatives. The company owns or partners with multiple robotics companies. But most of those investments have been about hardware or specific applications. Deep Mind's involvement with Atlas represents something different: positioning Google as the AI backbone of the robotics industry.

The strategy is clear. Hardware companies like Boston Dynamics build the physical systems. But increasingly, what matters is software intelligence. A robot with basic AI is useful. A robot with Deep Mind-level AI is transformative. If Google can make its foundation models the standard for industrial robotics, the company gains influence over the entire industry.

Geometry Robotics is the implementation of this strategy. It's Google saying: we've built foundation models that understand physics and robotics. We can integrate them into any robot. We can make your robot smarter.

This creates a powerful dynamic. Boston Dynamics builds excellent hardware but doesn't necessarily have the best AI for robotics. Deep Mind has the best AI but hasn't built hardware. Together, they're positioning Google to own both the hardware reference platform and the AI that makes it valuable. Other robotics companies will have to decide: do we license Deep Mind's AI, or do we try to build competitive AI ourselves? If licensing is cheaper and faster than building internally, the market consolidates around Google's technology stack.

There's also a data advantage. As Atlas robots deploy at Hyundai and other manufacturers, they generate enormous amounts of data about manufacturing tasks, failures, and solutions. This data feeds back into Deep Mind's foundation models, making them better. The company gets to improve its AI using real-world manufacturing data while competitors are still working with simulated data. This advantage compounds over time.

The partnership also signals Google's confidence in robotics as a strategic market. Google has been criticized for investing in technology with unclear commercial value. Robotics is not that category anymore. The commercial value is explicit. Companies are deploying robots for economic advantage. Google wants a piece of that market, and Deep Mind is the lever.

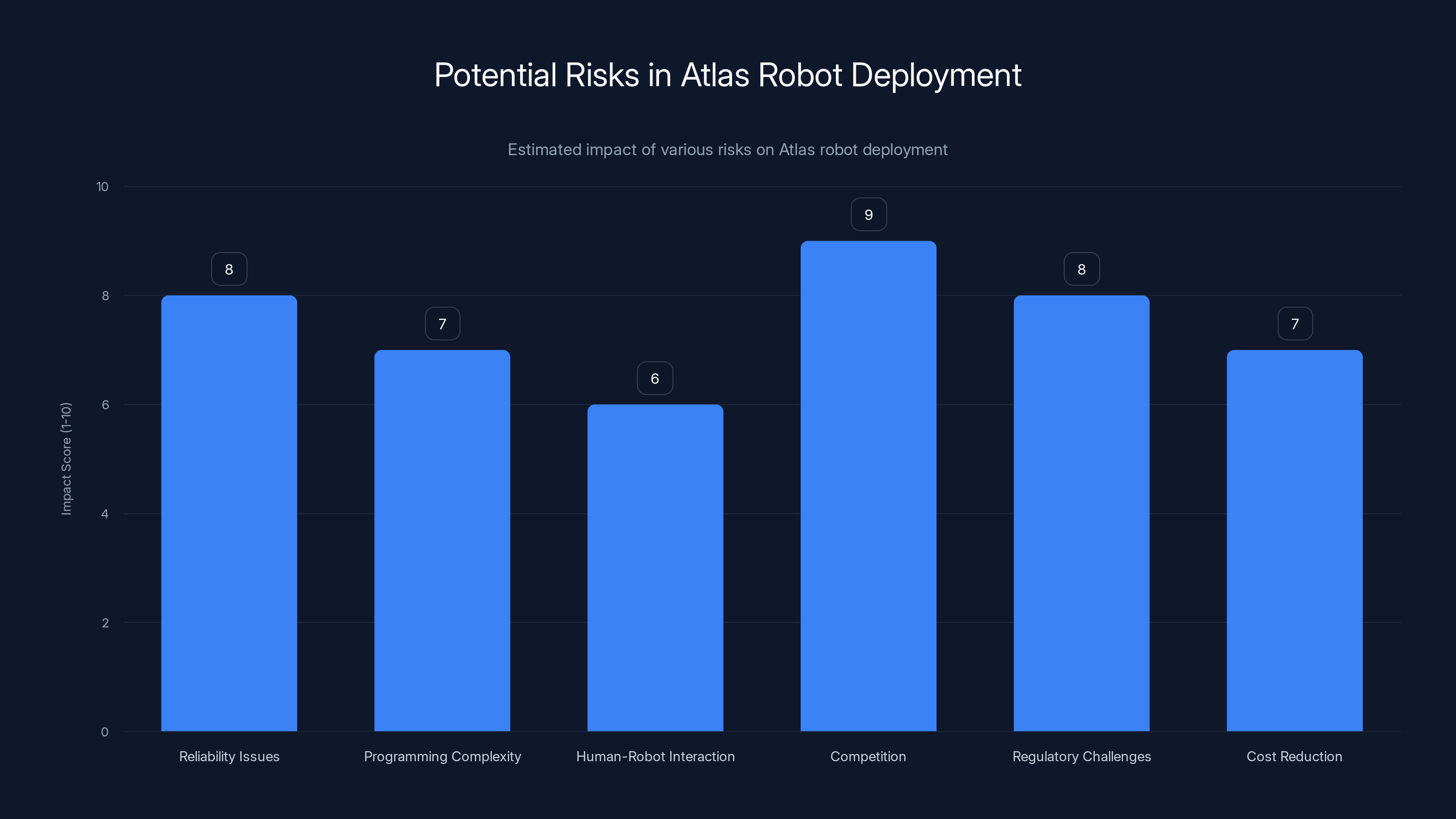

Estimated data suggests that competition and regulatory challenges pose the highest risks to Atlas robot deployment, with potential impacts rated at 9 and 8 respectively.

The Broader Context: Where Does Atlas Fit in the Robotics Landscape?

Atlas doesn't exist in isolation. There's a broader robotics landscape that's heating up.

Tesla is building Optimus, a humanoid robot explicitly designed for manufacturing and logistics. The company has massive engineering resources and real-world manufacturing experience. If Tesla gets Optimus working, it could be competitive with Atlas on cost and integration.

Boston Consulting Group estimates the industrial robotics market could exceed $100 billion annually by 2030. That's a huge market. It's not winner-take-all. There's room for multiple successful companies. But there's not room for everyone.

Atlas has several advantages. It's real. The robot exists and works. It's not vaporware or aspirational engineering. Hyundai is committing to it with real deployments. Google is investing real R&D into its AI integration. These aren't maybe commitments. They're concrete actions.

Atlas also has humanoid form factor, which matters more than people realize. A humanoid robot can use tools and equipment designed for humans. It can navigate spaces built for humans. It can be trained by demonstrating tasks to humans. This is different from specialized industrial robots that work in purpose-built cells. The generality of the humanoid form factor means Atlas can potentially work in more environments and be repurposed more easily.

But Atlas also has challenges. Humanoid robots are mechanically complex. They're harder to manufacture at scale than specialized industrial robots. The cost per unit is higher. The technology is less proven in real manufacturing environments. These aren't insurmountable challenges, but they exist.

The competitive landscape matters because it determines how fast robotics adoption accelerates. If only Boston Dynamics has a viable humanoid robot, adoption is limited by production capacity. If multiple companies offer competitive products, adoption accelerates dramatically as supply increases and prices fall through competition.

Atlas will likely face competition within the next 3-5 years. Tesla's Optimus might reach parity. Chinese robotics companies are investing heavily. Universities are advancing humanoid robotics research. The technology isn't exclusive. But being first with a production-ready system, backed by major manufacturers and AI researchers, gives Boston Dynamics a significant head start.

Practical Implications: How Manufacturing Will Actually Change

Let's get concrete about what the deployment of Atlas actually means for manufacturing in practice.

Parts sequencing, Hyundai's initial use case, involves picking components from bins or shelves, verifying they're correct, and placing them on assembly line stations in the right sequence. Currently, humans do this. The work is repetitive, physically demanding, and error-prone. People get tired. They make mistakes. They need training and supervision.

Atlas doing this work means:

- Elimination of human error in sequencing: The robot never picks the wrong part or places it in the wrong location

- 24/7 operation: The factory can run continuously without shift changes or fatigue

- Predictable timing: The robot performs consistently, which helps optimize the overall assembly line

- Reduced workplace injury: One fewer dangerous task that humans need to do

The transition requires investment. Hyundai needs to redesign part storage to be robot-accessible. It needs to set up charging infrastructure. It needs to train workers on robot maintenance and exception handling. The initial implementation is complex.

But once deployed, the benefits compound. The robot learns the task better over time as its AI improves. The manufacturing facility learns how to work alongside robots. The economics of automation become obvious. Other facilities in the company want the same setup. Competitors see the efficiency and realize they need to follow.

This is where the inflection point matters. The first few deployments are expensive experiments. By the fifth or tenth deployment, it's proven technology with understood costs and documented benefits. By the hundredth deployment across an industry, it's standard practice.

Component assembly is more complex. This is where the AI integration becomes critical. Different car models might have variations. Parts might have minor defects that need to be worked around. The assembly process might need to be adapted based on what's happening in real time.

Hard-coded robots would struggle with this. AI-integrated robots that have learned from thousands of assembly examples can adapt. They can notice that a part isn't fitting correctly and adjust their approach. They can handle minor variations without requiring human intervention.

Hyundai's timeline suggests that full component assembly might take until 2030 or beyond. This isn't because the robots aren't ready. It's because manufacturing facilities need to be redesigned, workers need to be retrained, processes need to be optimized. The robot deployment is straightforward. The organizational change is the bottleneck.

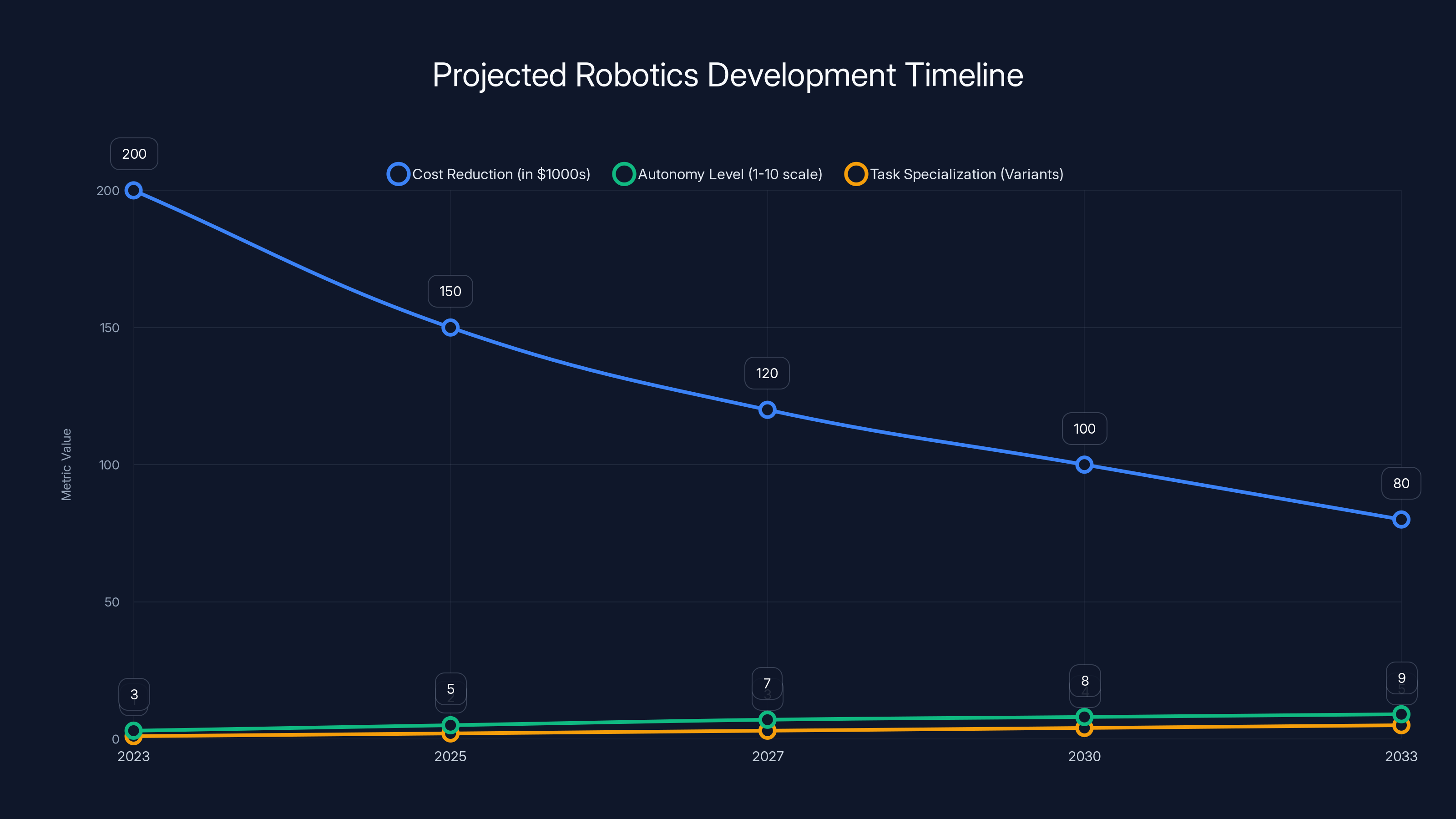

Over the next decade, robotics will see significant cost reductions, increased autonomy, and greater task specialization. (Estimated data)

The Economic Impact: Jobs, Wages, and the Future of Work

Let's address the elephant in the room: what does Atlas mean for manufacturing jobs?

The honest answer is complex. On one hand, automation eliminates specific tasks. Parts sequencing jobs will largely disappear. Repetitive assembly tasks will be automated. The number of people doing those jobs will decline. This is economically efficient for manufacturers but difficult for workers.

On the other hand, new jobs emerge. Someone needs to maintain the robots. Someone needs to reprogram them when tasks change. Someone needs to handle parts that the robot rejects or tasks that exceed its capabilities. Someone needs to be the robot supervisor. These jobs are typically better paid than the jobs that were automated because they require more skill and judgment.

The historical pattern suggests that technological change in manufacturing increases overall productivity and wages, but the transition period is brutal for workers whose specific tasks are automated. The solution is training and support for displaced workers, but that requires investment that manufacturers often don't want to make and that governments sometimes don't prioritize.

Hyundai has an opportunity to set an example here. The company could commit to retraining workers displaced by Atlas deployment rather than simply eliminating positions. This would be more expensive initially, but it would maintain workforce stability, preserve institutional knowledge, and create better employment outcomes. It would also make other manufacturers more comfortable deploying robots if they see it done responsibly.

The broader economic impact is even more significant. Manufacturing is a foundation of economies. Countries that remain competitive in manufacturing maintain economic power and high-wage jobs. Automation is happening regardless of whether individual companies want it. The companies that adopt automation will outcompete those that don't. The countries that support manufacturing automation will maintain industrial capabilities. Those that don't will see manufacturing decline and jobs move elsewhere.

This is why government policy matters. Smart policy supports worker retraining, encourages responsible automation deployment, and invests in the industries of the future. Poor policy tries to prevent automation (which doesn't work because of competitive pressure) or ignores the displacement impact (which causes social problems).

Atlas represents a genuine shift in economic fundamentals. The companies and countries that navigate this shift well will thrive. Those that don't will struggle.

The Technology Timeline: What Comes Next?

We're not at the end of robotics development. We're at the beginning of deployment. The next 5-10 years will see enormous changes in robotics capability.

Immediately, expect refinement of the current generation. Boston Dynamics will improve reliability, reduce maintenance requirements, increase autonomy, and optimize cost. The current Atlas is expensive. Future versions will be cheaper while maintaining capability.

AI integration will accelerate. Foundation models will improve. Robots will be able to handle more complex tasks with less supervision. The boundary of what robots can do without human intervention will continuously expand.

Specialization will emerge. The current Atlas is general-purpose, but specialized variants will likely appear. A variant optimized for heavy lifting, one for precision work, one for dirty or hazardous environments. These specializations will improve performance in specific domains.

Cost reduction is inevitable. The first robots are always expensive because of low production volumes and manufacturing immaturity. As volumes increase, unit costs fall dramatically. We could see Atlas-class robots declining from

Dexterity will improve. Current robots like Atlas are good at gross manipulation. They can pick things up and move them. Future robots will be able to do delicate work: adjusting small parts, threading components, handling fragile items. This expands the range of manufacturing tasks that can be automated.

Teamwork between robots will emerge. Two robots working together can accomplish things that one robot can't. Three robots coordinating can construct complex assemblies. Swarm robotics concepts from research will move into practical manufacturing.

Estimated data shows Hyundai's gradual integration of Atlas robots, starting with parts sequencing in 2028 and moving towards complex operations by 2032.

Comparing Atlas to Other Solutions: Where Does It Fit?

Atlas isn't the only solution for manufacturing automation. It's one option among several.

Traditional industrial robots, like those from ABB or KUKA, are highly specialized for specific tasks. They're faster, cheaper, and more reliable than humanoid robots for many applications. If you have a specific, well-defined task like welding or painting, a traditional robot is probably better than Atlas.

Cobots (collaborative robots) like those from Universal Robots are designed to work safely alongside humans. They're smaller, cheaper, and easier to program than traditional robots. They're good for tasks that mix human and robot work.

Tesla's Optimus is the closest competitor to Atlas. It's still in development, but the company has massive resources. If Optimus reaches parity with Atlas in 2-3 years, competition will accelerate development and reduce costs.

Atlas's advantage is generality. The humanoid form factor means it can work in environments built for humans without extensive modification. It can be retrained for new tasks more easily than specialized robots. It can handle variation and unexpected situations better than hard-coded systems.

The disadvantage is that it's more complex, more expensive, and less proven than traditional industrial robots. For companies that have a clear, stable set of tasks, traditional robots are probably better. For companies that want flexibility and capability for varied tasks, Atlas is more attractive.

Strategic Implications for Tech Giants and Manufacturers

Why does Google invest in Atlas through Deep Mind? Why does Hyundai become a majority shareholder?

It's not just about the robot. It's about positioning in the future economy.

Google is betting that robotics will be as important as computers and the internet. The company wants to own the AI that powers robots. If Google succeeds, every robot maker will either use Google's AI or compete directly with Google. This gives Google influence over an entire industry.

Hyundai is betting that manufacturing automation is mandatory for competitiveness. The company that deploys robotics first and most effectively will have the largest profit margins and the most capital for future investment. Hyundai is trying to make sure that company is itself.

Boston Dynamics gets access to real manufacturing problems and real deployment data. This accelerates product development. The company also gets access to capital and manufacturing expertise from Hyundai and research capability from Google. The partnerships are strategically valuable.

This is how technology adoption actually happens. It's not random. It's strategic investment by players who recognize the importance of emerging technology and position themselves to benefit from it.

The broader lesson is that robotics is moving from research to industry. Companies are deploying real capital and making real commitments. This signals genuine confidence that the technology is ready and valuable. When Google and Hyundai both invest at this level, the market is signaling that robotics adoption is coming faster than many people expect.

Challenges and Risks: What Could Go Wrong?

Atlas is production-ready from an engineering perspective. But real-world deployment has risks.

Reliability in the first deployments might not match lab results. Manufacturing is messy. Parts vary. Equipment isn't perfectly aligned. Temperatures fluctuate. The robot might encounter situations that weren't anticipated. If early deployments have frequent failures or require constant maintenance, adoption will slow.

Programming new tasks might be harder than expected. The vision is that you can show the robot a task and it learns to do it. But this might require more careful setup, better data, more human intervention than currently assumed. If programming takes weeks for each new task instead of days, the economic case gets worse.

Robotworker relationships might be more difficult than expected. Humans working alongside robots might develop new safety concerns or productivity challenges. Management systems for mixed human-robot teams are still being developed. If coordination is harder than expected, productivity gains are reduced.

Competition might arrive faster. Tesla might launch a competitive Optimus. Chinese companies might develop parallel systems. If Atlas faces strong competition quickly, unit costs might not fall as expected and market share might be limited.

Regulatory risk is real. Governments might restrict robotics deployment to protect jobs. Labor unions might push for regulations that increase costs. Safety regulations around human-robot interaction might be more restrictive than expected. These regulatory risks aren't about technology capability. They're about social and political response to automation.

Cost might not fall as fast as expected. The first robot costs

The Practical Path Forward for Manufacturing Companies

If you're a manufacturing company evaluating Atlas, what should you do?

First, understand your current operations deeply. Which tasks are most expensive? Which are most repetitive? Which are most difficult? Where do accidents happen? Where is quality most variable? These are the candidates for robotics automation.

Second, establish a pilot program. Don't commit to 50 robots immediately. Bring in two or three, focus on one task, learn what actually happens. The pilot will teach you what matters and what doesn't. It will surface challenges that planning didn't anticipate.

Third, invest in organizational change in parallel with technology deployment. Train workers on new roles. Set up maintenance and programming teams. Establish safety protocols. Design workflows that work with robots. The technology is only half the equation.

Fourth, watch competitors. If other companies are deploying robots successfully, competitive pressure will force you to follow. If no one is deploying robots yet, you might be first to market advantages. But the market will move toward robotics adoption regardless of individual company decisions.

Fifth, develop relationships with robotics companies. Get on their beta testing programs if available. Provide feedback on real manufacturing challenges. You'll get earlier access to improvements and you'll influence product development toward your needs.

Finally, think strategically about which tasks to automate. Don't optimize for cost alone. Consider whether automation enables you to take on new work, serve new customers, or enter new markets. The real value of robotics might not be cost reduction. It might be capability expansion.

Looking Ahead: The 10-Year Outlook

Ten years from now, what will manufacturing look like?

Humanoid robots will be significantly more common, but not dominant. They'll handle the tasks that work well with their form factor. Specialized robots will still exist and probably dominate by sheer numbers. But humanoid robots will be the flexible backbone of many operations.

Costs will have fallen significantly. Atlas at

Capabilities will have expanded dramatically. Robots will be able to handle more dexterous work, more complex assembly, more uncertain situations. AI integration will be standard, not novel. Robots will be able to adapt to new tasks with minimal human input.

Multi-robot teams will be common. Single robots are useful. Teams of robots coordinating on complex assemblies will be transformative. Manufacturing facilities might have robots working in coordinated groups doing work that no single-robot system could accomplish.

The job market will have evolved. Manufacturing jobs won't disappear, but their nature will change. More skilled maintenance and programming roles, fewer repetitive task roles. Wages will likely be higher for remaining manufacturing workers because they're doing more valuable work. But displacement and transition will have been painful for some workers.

Competitive dynamics will have shifted. Companies that automated early will have had 10 years to optimize their operations and reduce costs further. Companies that waited will be playing catch-up. But the fundamental economics of automation are so strong that waiting doesn't change the inevitable outcome. Every company will eventually have to automate or lose competitiveness.

Geopolitically, this matters. Countries that support robotics development and deployment will maintain manufacturing capabilities and high-wage jobs. Countries that don't will see manufacturing decline. This is one reason why robotics is becoming a strategic priority for major economies.

Atlas represents the beginning of this transition, not the end. The robot is important, but more important is what it signals: the era of serious robotics deployment in manufacturing has started.

FAQ

What is Boston Dynamics Atlas?

Boston Dynamics Atlas is a production-ready humanoid robot engineered for industrial manufacturing tasks. The robot stands approximately 5 feet 8 inches tall, can lift 110 pounds, reach up to 7.5 feet high, and operates reliably in temperatures from minus 4 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit. Unlike earlier prototype versions that became famous for performing acrobatics and backflips, the production Atlas was specifically designed with industrial consistency and reliability as core principles, enabling it to perform repetitive manufacturing tasks with the accuracy and reliability that factories require.

How does Atlas perform manufacturing tasks?

Atlas uses a combination of advanced sensors, computer vision, and AI-powered decision-making to understand and interact with its environment. The robot can operate three different ways: fully autonomous for well-understood tasks, with a human teleoperator for complex situations requiring real-time control, or through a tablet interface where the robot handles routine work while humans maintain oversight. The integration with Google Deep Mind's Gemini Robotics AI foundation models allows Atlas to learn from examples and adapt to variations in tasks, meaning it can handle minor differences in parts or equipment alignment without requiring complete reprogramming.

What tasks will Hyundai use Atlas for first?

Hyundai's initial deployment beginning in 2028 will focus on parts sequencing, which involves picking components from storage, verifying accuracy, and placing them on assembly line stations in the correct sequence for assembly. This task was chosen because it's highly repetitive, physically demanding, currently performed by humans, and has clear metrics for success. By 2030, Hyundai plans to expand Atlas deployment to component assembly tasks, which are more complex because they require the robot to handle part variations and adapt its approach based on what's happening during assembly. Over time, the company envisions Atlas taking on additional tasks involving heavy loads, repetitive motions, and complex operations currently performed by factory workers.

Why is Google Deep Mind involved with Atlas?

Google Deep Mind is developing Gemini Robotics, AI foundation models specifically designed to give robots like Atlas genuine learning capability and adaptability. While Boston Dynamics builds excellent hardware, Google provides the AI that enables robots to understand tasks, learn from examples, and adapt to variations without explicit programming for every situation. This partnership serves both companies: Boston Dynamics gains access to world-class AI that makes its robots more capable, while Google gets real-world manufacturing data to improve its foundation models and establishes itself as the AI backbone for industrial robotics worldwide. Deep Mind's involvement signals Google's confidence that robotics will be as strategically important as previous computing paradigm shifts.

How much will Atlas cost?

Boston Dynamics hasn't publicly disclosed Atlas pricing, but based on its capabilities, manufacturing complexity, and comparable industrial robotics systems, the production version likely costs between

When will Atlas be widely available?

Atlas deployment will happen gradually. Hyundai will receive the first units starting in 2028, with production-scale deployment by 2030. Other manufacturing companies will likely begin pilot deployments in 2027-2028, with broader adoption accelerating through 2030-2035. The progression will follow the traditional technology adoption curve: early adopters first (2026-2028), early majority (2029-2032), late majority (2033-2035), and laggards (after 2035). Factors affecting adoption speed include actual reliability in manufacturing environments, cost reduction as production volumes increase, competitive offerings from other robotics companies, and labor market dynamics. Full industry transformation will likely take 10-15 years, but the inflection point where adoption becomes inevitable is arriving now.

What are the main advantages of humanoid robots compared to traditional industrial robots?

Humanoid robots like Atlas have fundamental advantages over specialized industrial robots for many tasks. First, the humanoid form factor means robots can work in environments designed for humans without extensive facility redesign. Second, because humanoid robots use human-like movement patterns, they can often be trained by demonstrating tasks rather than requiring detailed technical programming. Third, the same humanoid robot can be retrained for different tasks relatively easily, providing flexibility that specialized robots don't offer. Fourth, humanoid robots can handle variation and unexpected situations better because AI integration enables learning and adaptation. The trade-offs are that humanoid robots are more mechanically complex, currently more expensive per unit, and less proven in manufacturing than specialized robots that have been refined over decades.

How will Atlas deployment affect manufacturing jobs?

Atlas deployment will eliminate specific repetitive tasks currently performed by human workers, which means the number of people doing those jobs will decline. However, manufacturing automation historically increases overall economic output and average wages, while shifting the types of work available. Jobs that remain in manufacturing are typically more skilled and better paid than the jobs that were automated, involving robot maintenance, programming, quality control, and problem-solving. The challenge is that transition periods are difficult for workers whose specific tasks are automated if they don't receive training for new roles. Companies and governments that invest in worker retraining and support successful career transitions will manage this shift well. Those that simply eliminate positions without supporting affected workers create social problems and economic disruption. Hyundai has an opportunity to set an example by committing to retraining rather than simply eliminating positions.

What could prevent or delay Atlas adoption?

Several factors could slow deployment. Technical challenges might emerge once Atlas operates in real manufacturing environments with all their variability and complexity. Reliability might be lower than lab testing suggests, or maintenance requirements might be higher than expected. Programming new tasks might require more time and expertise than currently anticipated. Competitive offerings from Tesla, Chinese companies, or others might provide better solutions at lower costs. Regulatory changes around human-robot interaction, safety, or labor protections could increase deployment costs and complexity. Economic downturns could reduce capital available for manufacturing investment. Labor union pressure or government policies protecting jobs could restrict deployment. Even with these risks, the fundamental economics of automation are so compelling that widespread adoption is highly likely within 10-15 years. The question isn't whether robotics adoption happens, but how quickly and equitably the transition occurs.

How does AI integration in Atlas differ from traditional robot programming?

Traditional industrial robots use hard-coded programming where engineers specify exactly what the robot should do in specific situations. This works well for highly standardized, unchanging tasks, but breaks down when situations vary or weren't anticipated during programming. AI-integrated systems like Atlas trained with Deep Mind's foundation models learn patterns from examples rather than following explicit instructions. If a part doesn't fit perfectly or equipment is slightly misaligned, the robot recognizes the variation (because it's learned what variations look like) and adapts its approach. This learning capability enables flexibility that hard-coded systems cannot achieve. The drawback is that AI systems sometimes make mistakes in unfamiliar situations, whereas hard-coded systems are predictable but brittle. For manufacturing, the flexibility often matters more than perfect predictability.

What's the competitive landscape for humanoid manufacturing robots?

Boston Dynamics' Atlas is currently the most mature production-ready humanoid robot, backed by real manufacturing partnerships and deployment timelines. Tesla is developing Optimus, which could be competitive within 3-5 years if the company successfully scales production. Chinese companies are investing heavily in humanoid robotics, though they're generally a few years behind U. S. and Japanese competitors. Universities worldwide are advancing humanoid robotics research. Specialized industrial robots from established manufacturers like ABB, KUKA, and Fanuc remain dominant for their specific applications. The emerging competitive landscape suggests that by 2030, multiple credible humanoid robot options will exist, driving costs down and capabilities up. The winner won't be the single best robot, but the platform that combines hardware reliability, software intelligence, and manufacturing partnerships most effectively.

Conclusion: The Beginning of the Robotic Era

When Boston Dynamics announced the production-ready Atlas at CES 2026, it marked a genuine inflection point. The world didn't immediately change. Hyundai won't deploy hundreds of robots overnight. Google didn't announce that Gemini Robotics will revolutionize everything tomorrow.

But the signal was clear: humanoid robotics is moving from research to production. Real companies are making real commitments. Real capital is being invested. Real manufacturing challenges are being addressed. This is how fundamental shifts in technology actually happen. Not with explosions and overnight disruption, but with careful, staged deployment by strategic actors who understand the implications.

Atlas represents the culmination of decades of robotics research and the beginning of decades of manufacturing transformation. The robot is good enough to work. The economics make sense. The partnerships are real. The timeline is plausible. Everything aligns for serious deployment beginning in the next 2-3 years.

Manufacturing will change. The companies that navigate this change well, that invest in robotics early, that support workers through transition, will emerge stronger. The companies that wait will face competitive pressure and eventual obsolescence. The countries that support manufacturing robotics will maintain economic strength. Those that don't will see manufacturing decline.

For individuals, the implications are real. If you work in manufacturing, especially in repetitive tasks, understanding robotics and preparing for transition is essential. If you work in industries that support manufacturing, demand for your services will increase as robotics deployment accelerates. If you're studying engineering or computer science, robotics represents genuine opportunity.

Atlas isn't the end of robotics development. It's the beginning of robotics deployment. And that deployment will reshape manufacturing, employment, and economic geography over the next decade. The changes are already starting. The robots are already being built. The partnerships are already formed. The timeline is already set.

The era of humanoid robots in manufacturing isn't coming. It's starting right now.

Key Takeaways

- Boston Dynamics' production-ready Atlas robot is beginning real-world manufacturing deployment starting in 2028, marking a genuine inflection point for industrial robotics adoption

- Hyundai's staged approach starting with parts sequencing and expanding to component assembly demonstrates practical, risk-managed deployment strategy for manufacturing automation

- Google DeepMind's Gemini Robotics AI integration enables Atlas to learn and adapt to manufacturing variations, fundamentally different from hard-coded traditional robots

- Economic payback occurs in 2-3 years when robot costs (80-100K annually), creating strong incentive for adoption

- Manufacturing job displacement will be significant but transition to higher-skilled maintenance, programming, and quality roles can occur if companies invest in worker retraining

Related Articles

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Robot 2028: Complete Guide & Automation Alternatives

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Press Conference Live [2026]

- Humanoid Robots in 2026: The Reality Beyond the Hype [2025]

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Presentation Live [2025]

- [2025] Humanoid Robots in Industrial Settings: Transforming Efficiency

- Ludens AI's Adorable Robots at CES 2026: Meet Cocomo and Inu [2025]

![Boston Dynamics Atlas Production Robot: Enterprise Transformation [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/boston-dynamics-atlas-production-robot-enterprise-transforma/image-1-1767658223271.jpg)