Boston Dynamics Atlas: From Prototype to Commercial Product – A Complete Guide to the Future of Factory Automation

Introduction: The Moment Robotics Became Real

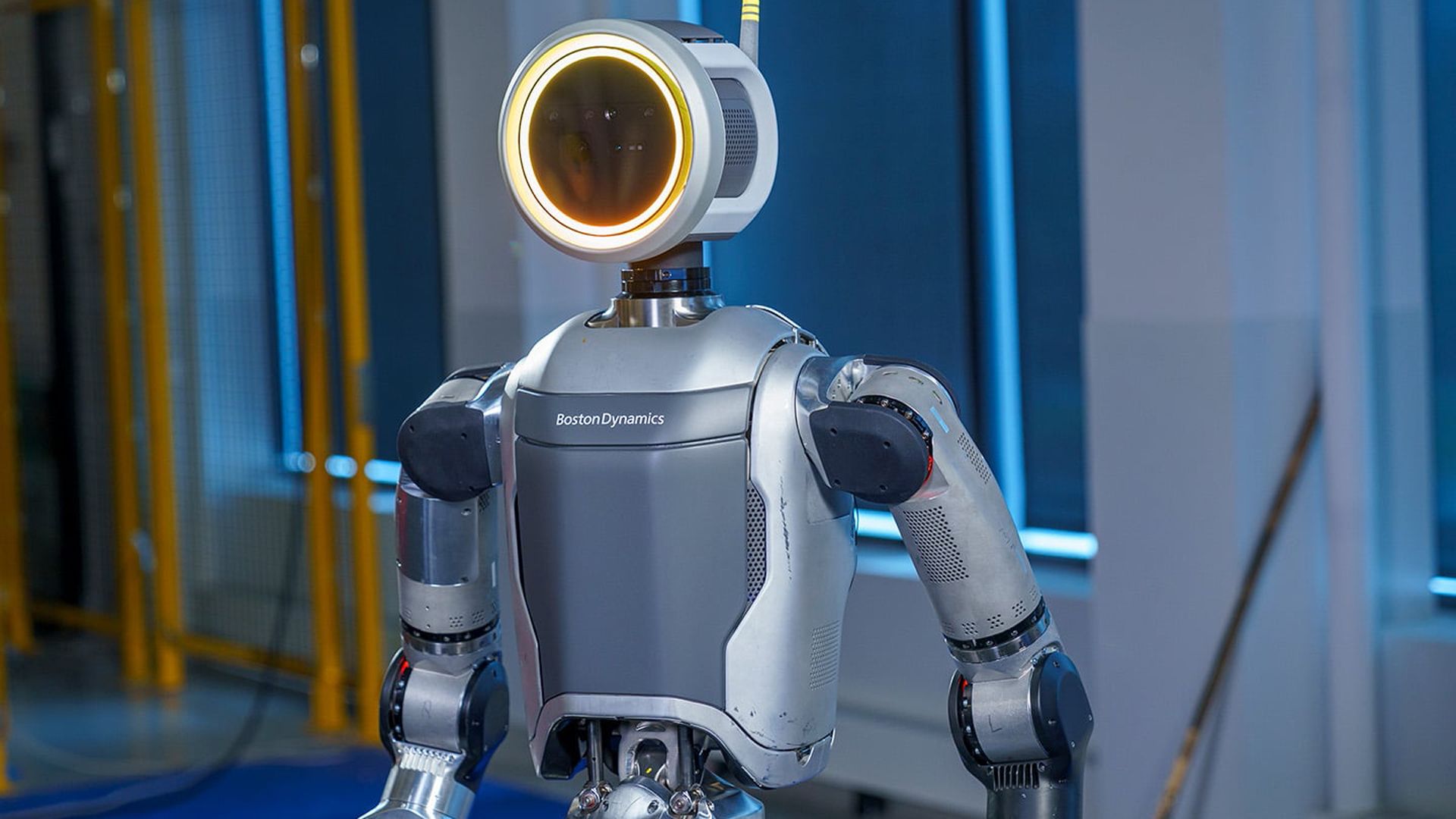

For over a decade, Boston Dynamics captured the world's imagination with viral videos of humanoid robots performing parkour, dancing, and executing complex movements that seemed more science fiction than engineering reality. The Atlas robot, their flagship humanoid platform, became the symbol of what advanced robotics could achieve—but it remained firmly in the research and development phase. Now, that era has definitively ended. Boston Dynamics announced that Atlas is transitioning from a research platform to a commercial product, with deployments in real factory environments beginning as early as 2028.

This represents one of the most significant inflection points in robotics history. We're not talking about incremental improvements to existing industrial robots or specialized manipulators. We're discussing a genuinely humanoid platform—bipedal locomotion, human-level dexterity, advanced perception, and sophisticated task planning—entering the competitive commercial market. The implications ripple across manufacturing, logistics, construction, and virtually every industry dependent on physical labor.

But this transition raises crucial questions for businesses, technologists, and industry observers. What exactly has Boston Dynamics changed about Atlas to make it production-ready? How will humanoid robots actually improve factory efficiency compared to existing automation solutions? What's the realistic timeline for deployment at scale? And critically, what alternative automation approaches should organizations evaluate alongside humanoid robotics?

This comprehensive guide examines the Atlas announcement in depth, analyzing what makes this moment different from previous robotics hype cycles. We'll explore the technical specifications that enable commercial viability, dissect the actual use cases where humanoid robots create measurable value, examine the pricing and deployment economics, and importantly, investigate the broader automation landscape that includes specialized robots, AI-driven workflow systems, and hybrid approaches that might better serve different organizational needs.

The robotics revolution is finally arriving—but understanding which automation solution fits your specific context is more important than ever.

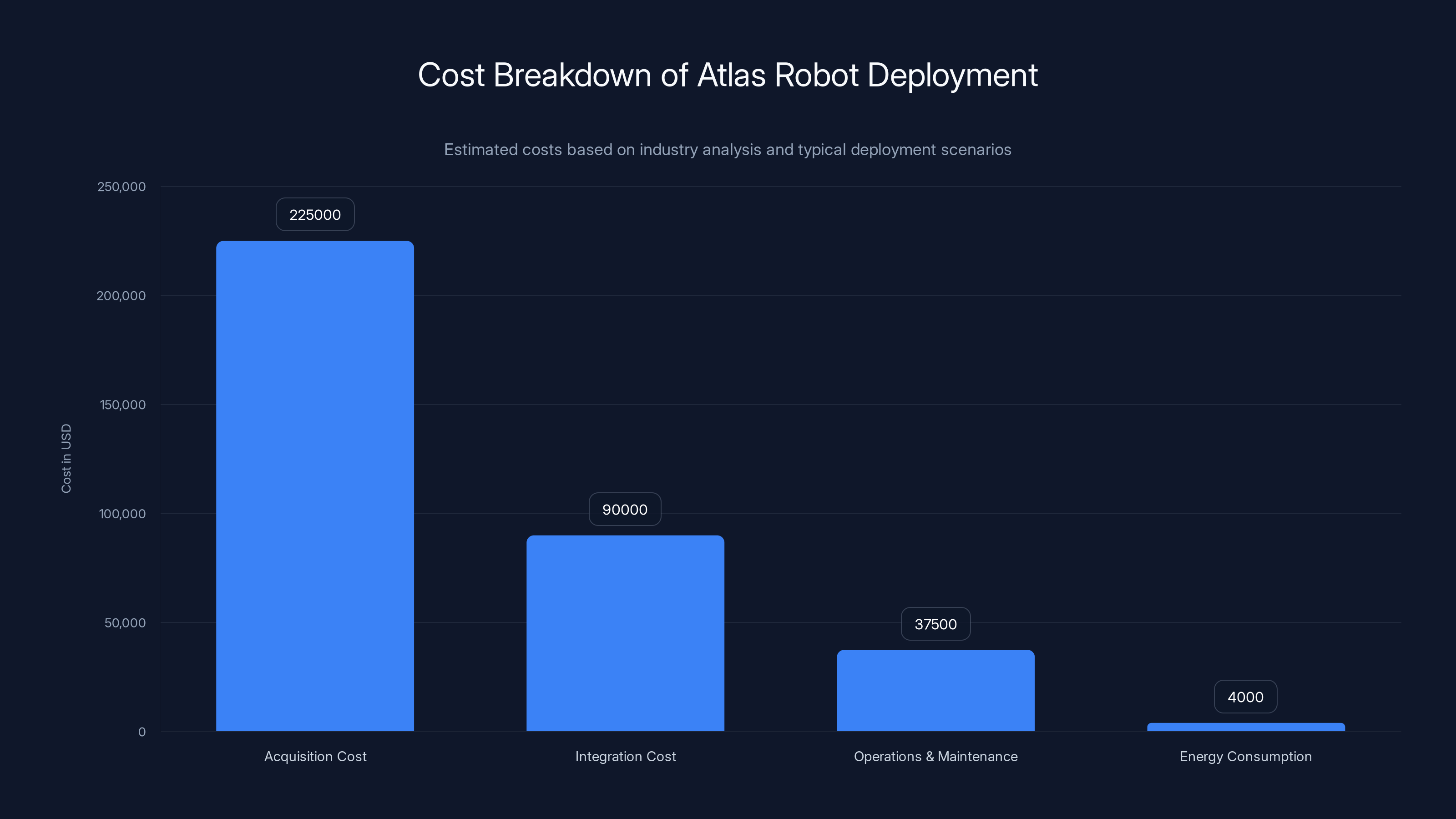

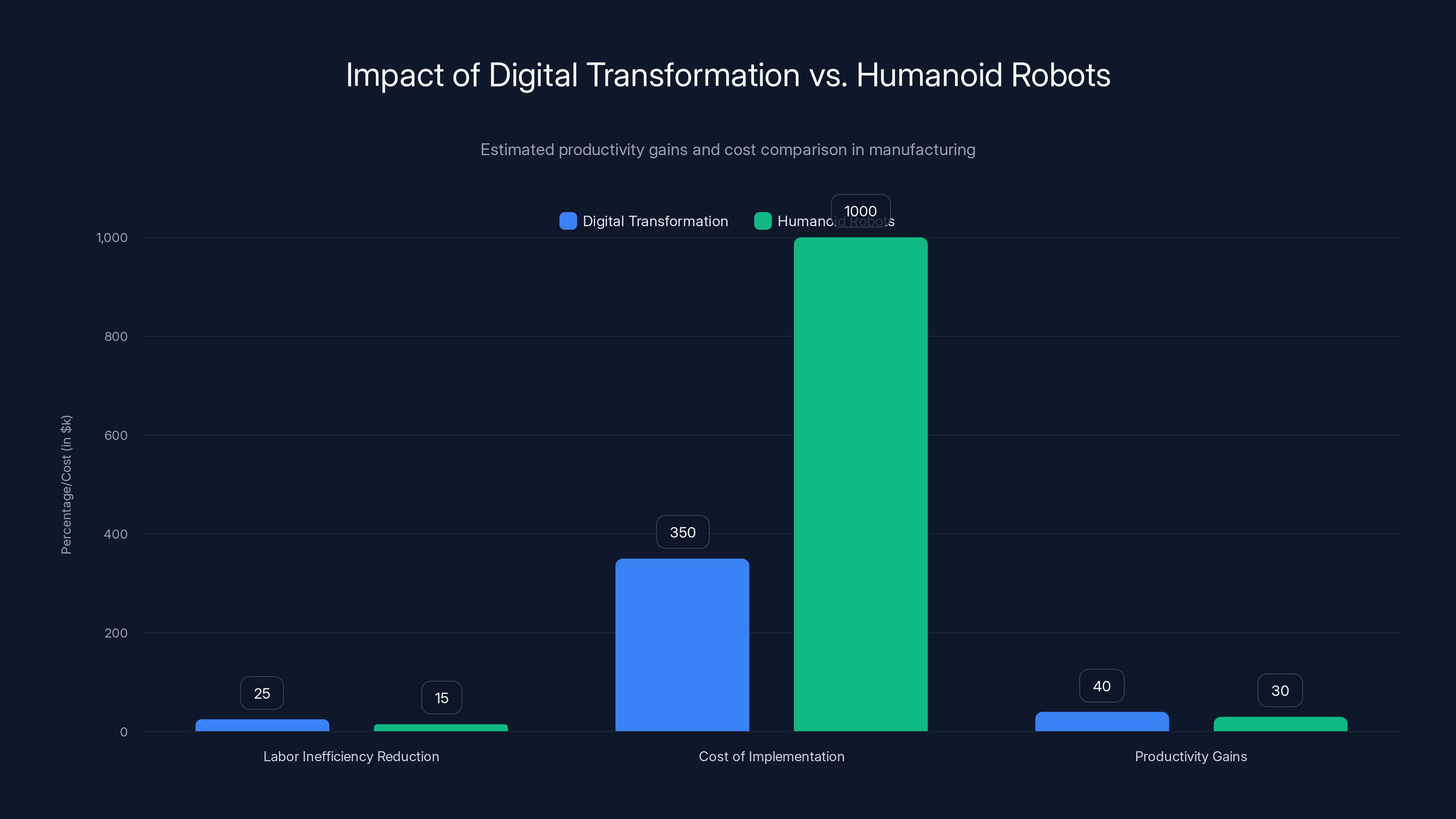

Estimated data shows that acquisition and integration are the largest costs in deploying an Atlas robot, with operations and maintenance also contributing significantly to total ownership costs.

What Changed: Atlas Transitions from Research to Commercial Product

The Announcement and Timeline

Boston Dynamics' shift to commercialization represents a fundamental organizational pivot. The company revealed that a new production version of Atlas is actively being developed for factory deployment starting in 2025-2026, with broader commercial availability anticipated by 2028. This timeline is aggressive but informed by three years of intensive real-world testing and iterative refinement.

What distinguishes this announcement from previous robotics proclamations is the specificity of industrial partners. Boston Dynamics has publicly committed to working with manufacturers in automotive, electronics, and logistics sectors—industries that have concrete pain points, established quality standards, and measurable ROI requirements. These aren't hypothetical partnerships; they represent binding commitments from companies with invested capital and reputational stakes.

The transition strategy itself reveals sophisticated thinking about commercialization. Rather than attempting to sell complete autonomy across all tasks immediately, Boston Dynamics is implementing a staged deployment approach. Early versions will handle well-defined, repetitive tasks in controlled environments. As the platform matures and machine learning models improve through field data collection, capabilities will expand to increasingly complex, variable scenarios. This mirrors successful software product launches that prioritize core use cases before feature expansion.

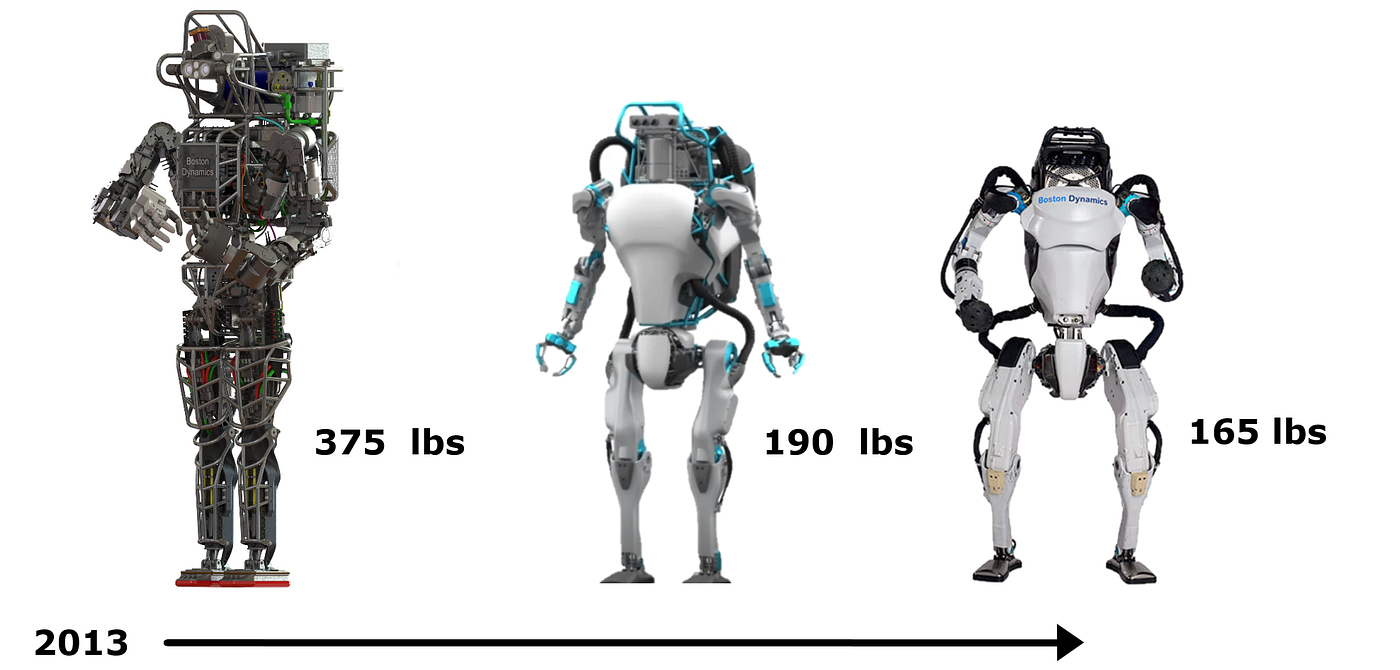

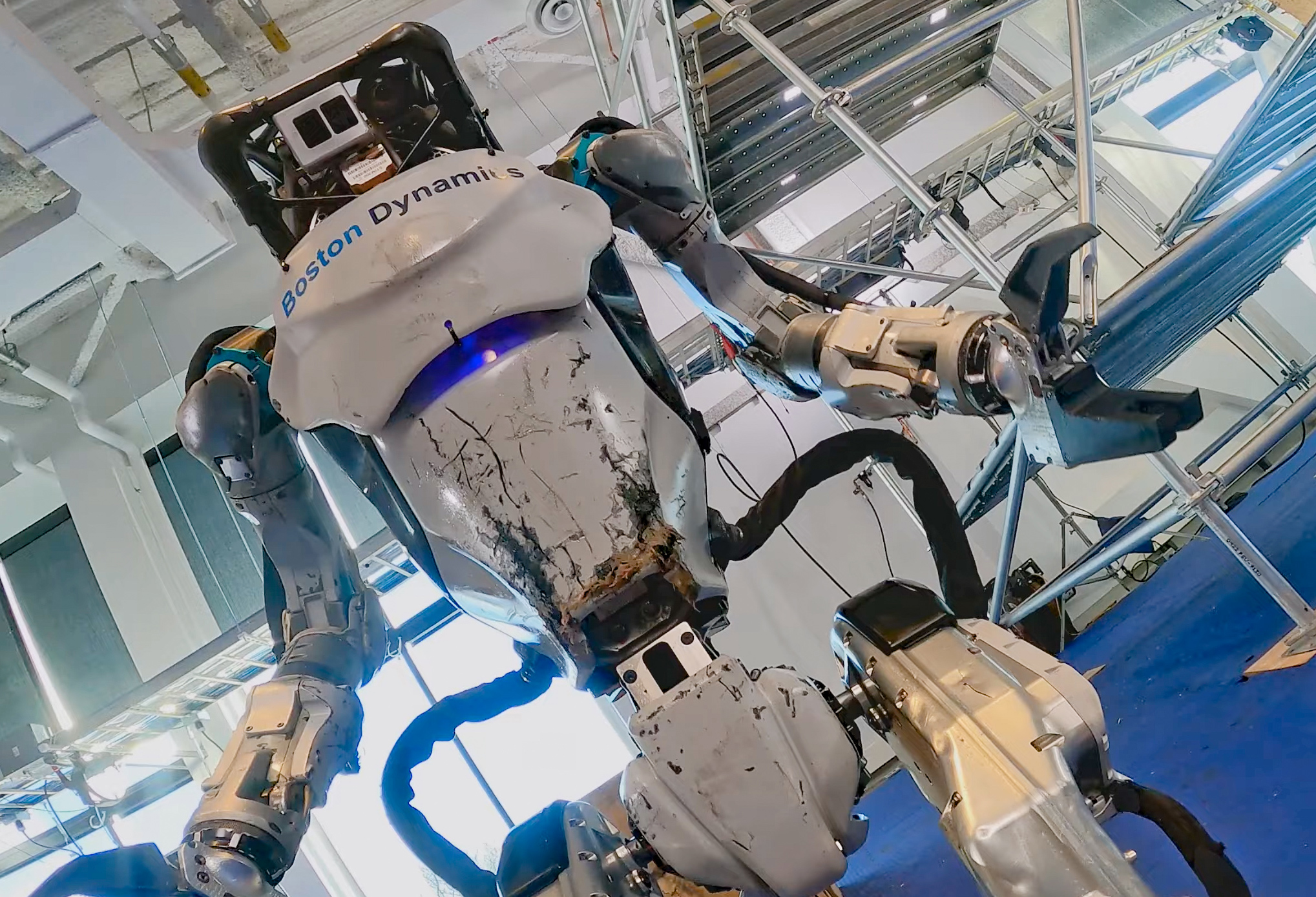

Hardware Evolution and Production Readiness

The new commercial Atlas differs meaningfully from research versions that captured public imagination. Durability, thermal management, battery life, and maintainability have undergone comprehensive redesign. Research robots optimized for impressive demonstrations; commercial robots must operate 8-10 hour shifts with minimal downtime, tolerate factory floor conditions (dust, temperature variation, vibration), and enable technicians without advanced robotics expertise to perform routine maintenance.

Boston Dynamics has redesigned the electrical system to use industry-standard components where possible, reducing procurement complexity and cost. The actuator technology has evolved to balance power output, responsiveness, and efficiency—a trilemma that requires sophisticated engineering trade-offs. The new design reportedly achieves 20% better energy efficiency compared to research platforms, extending operational duration and reducing the thermal signature that plagued earlier versions.

Sensor fusion architecture has similarly matured. Commercial Atlas integrates LIDAR, stereo vision, tactile sensors, and proprioceptive feedback into a unified perception system. The onboard compute stack has moved from external processing to integrated AI inference, enabling fully autonomous operation without constant communication to cloud systems. This architectural shift addresses the latency and connectivity concerns that would make earlier research systems unsuitable for factory floors with inconsistent network infrastructure.

Software Stack and Autonomy Level

The software transition represents equally significant work compared to hardware evolution. Boston Dynamics developed proprietary tools for task planning, collision avoidance, and adaptive control that enable Atlas to handle real-world variability. Rather than requiring perfect conditions, the new software stack enables the robot to recover from minor perturbations—a slightly off-target object to grasp, unexpected obstacles in the path, or environmental conditions varying from training scenarios.

The autonomy model implements hierarchical decision-making: high-level task planning manages what the robot should accomplish, intermediate-level controllers handle navigation and obstacle avoidance, and low-level controllers optimize individual motor commands. This architecture allows operators to define objectives at a human-understandable level while the system handles technical execution. A human might specify "move the parts from Station A to Station B," and the robot autonomously determines the optimal path, handles dynamic replanning if obstacles appear, and executes the movement with appropriate caution and precision.

Machine learning integration focuses specifically on learning from demonstration and reinforcement learning for fine-tuning. Rather than requiring explicit programming for every variation, Atlas can learn new tasks by observing a human perform the action and then practicing to optimize its own execution. This significantly accelerates the process of teaching the robot new capabilities—estimates suggest new task training might require 5-10 human demonstrations plus several hours of supervised practice, rather than weeks of engineering.

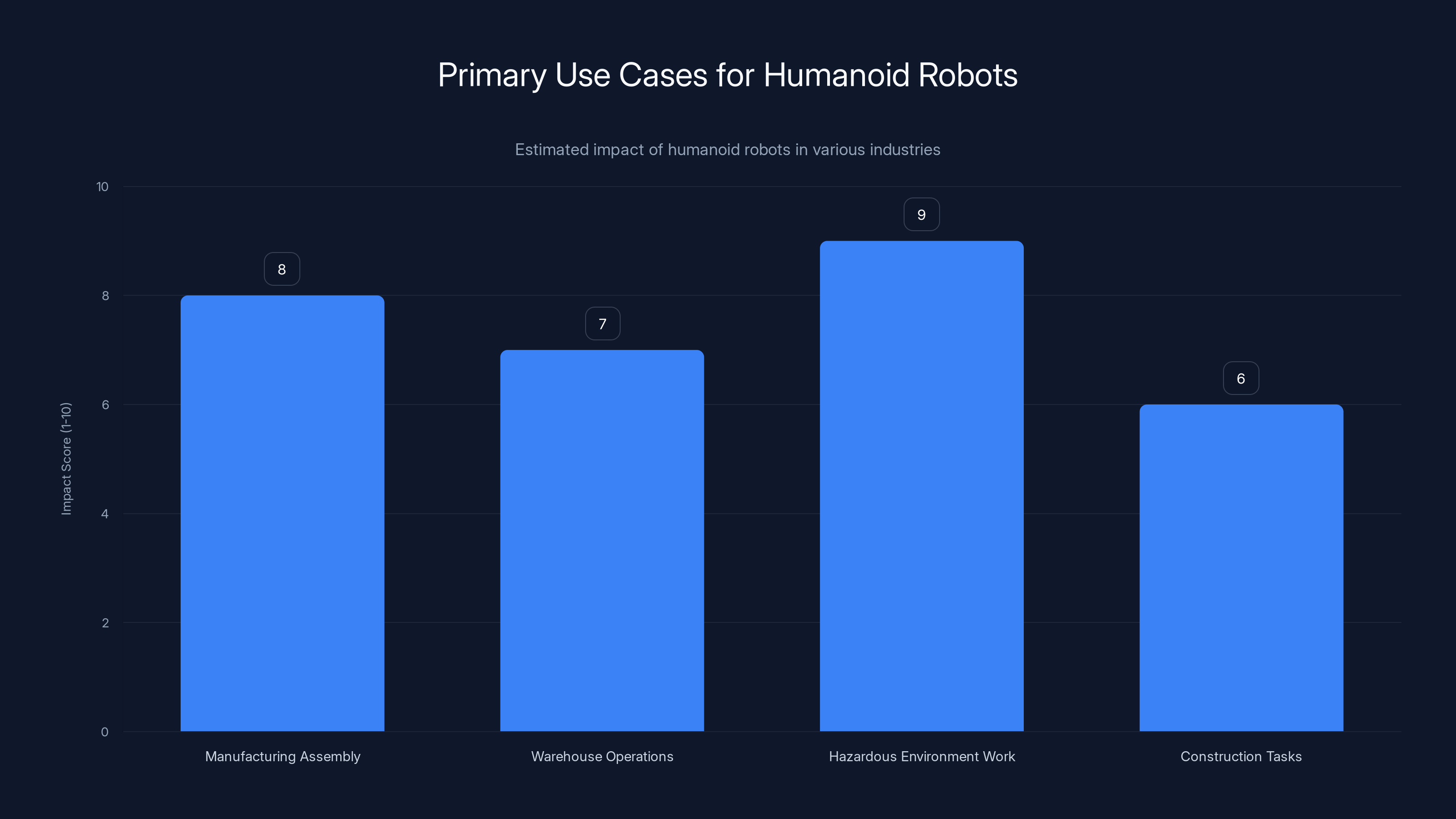

Humanoid robots like Atlas are expected to have the highest impact in hazardous environments due to their ability to handle dangerous tasks. Estimated data.

Technical Specifications: What Makes Commercial Atlas Viable

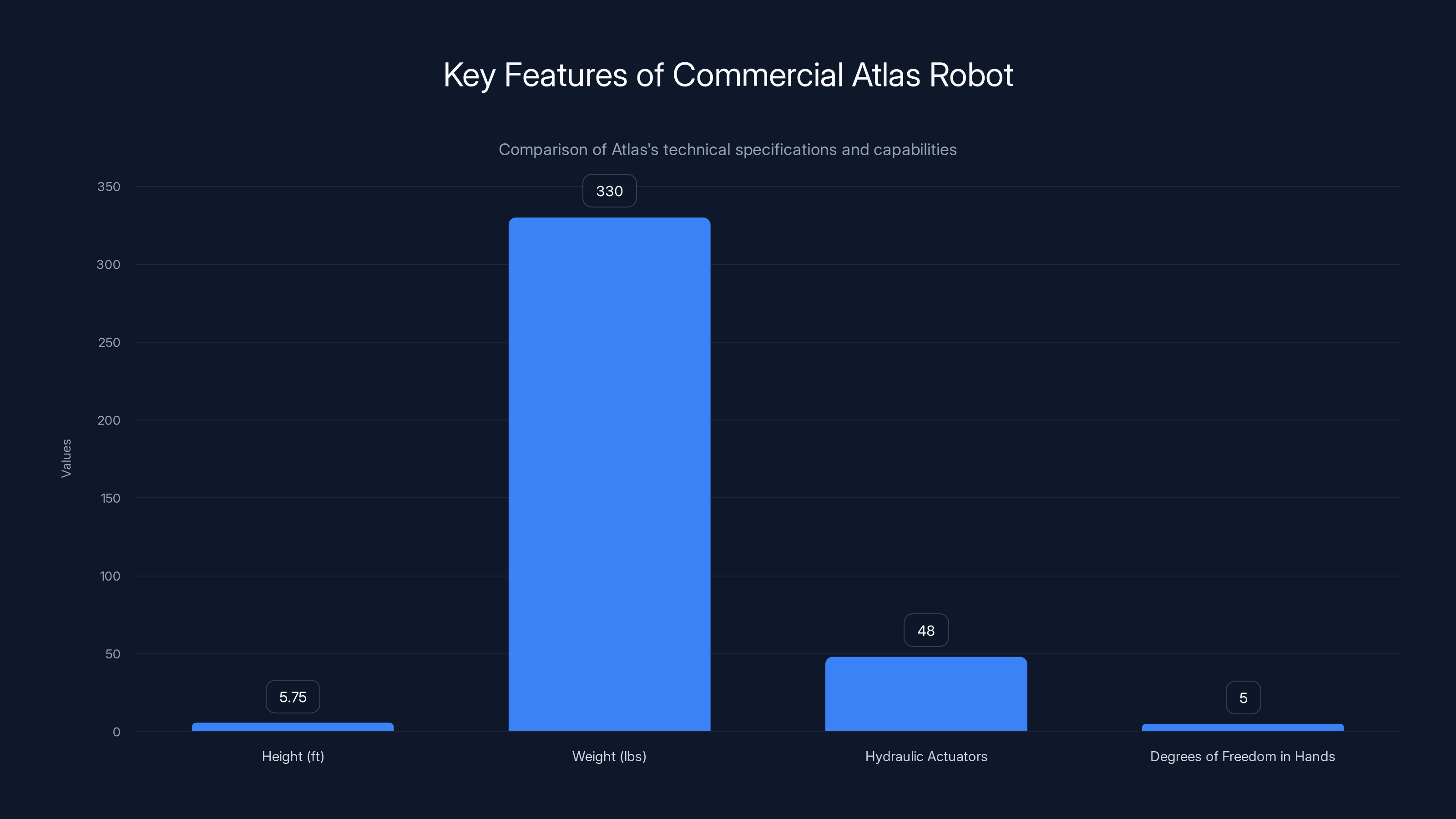

Physical Dimensions and Mobility Characteristics

Atlas maintains a humanoid form factor deliberately chosen to operate in human-designed spaces. The robot stands approximately 5 feet 9 inches tall and weighs roughly 330 pounds—larger than a human but within a scale that permits navigation through standard doorways, workspaces, and facility layouts designed for human workers. This human-scale form factor proves critical; rather than requiring facility modifications, Atlas can integrate into existing manufacturing environments.

The bipedal locomotion system remains the platform's most technically impressive and commercially valuable attribute. Human biped locomotion evolved for efficiency across variable terrain, enabling humans to navigate stairs, inclines, cluttered spaces, and soft surfaces that wheeled robots struggle with. Atlas replicates these capabilities through sophisticated dynamic walking algorithms that maintain balance despite perturbations, enable rapid direction changes, and generate efficient movement across diverse factory floor conditions. Recent demonstrations show Atlas navigating stairs, over obstacles, and across uneven surfaces—all critical for real-world factory deployment.

The robot achieves this through 48 hydraulic actuators distributed across its body, providing strength comparable to a human laborer while enabling fine motor control for delicate manipulation. The hydraulic system, while more complex than electric motors, provides superior power density—more force per unit weight—which proves essential for a platform that must perform varied tasks without external load-bearing equipment.

Dexterity and Manipulation Capabilities

Atlas features five-fingered hands with human-equivalent dexterity for the target application domains. Each hand contains multiple degrees of freedom enabling not just grasping but in-hand manipulation—rotating objects, adjusting grip, and performing complex assembly operations. The tactile sensing integrated into the fingertips provides feedback about object properties (surface texture, rigidity, slip risk) that informs manipulation strategy.

The manipulation system operates across a range of object types: rigid components requiring precise positioning, delicate items sensitive to excessive force, variable-geometry parts that don't have a single correct grasp point, and assemblies requiring sequential manipulation steps. Rather than requiring specialized grippers for each object type, Atlas' general-purpose hands adapt through learned grasping strategies. Early testing demonstrates the ability to reliably grasp objects with 95%+ success rates in controlled environments, with performance degrading gracefully as environmental variables (object wear, dust, orientation variation) increase.

Perception and Environmental Understanding

The sensor suite combines multiple perception modalities to build a comprehensive environmental model. LIDAR provides long-range, weather-resistant distance measurement for navigation planning and obstacle detection. Stereo cameras enable precise 3D object reconstruction necessary for manipulation planning. Thermal imaging reveals heat signatures that might indicate unsafe areas. Inertial sensors measure acceleration and rotation to support balance control. Proprioceptive sensors at each joint report position and force, enabling the robot to understand its own configuration and detect unexpected resistance during movements.

Integrating these diverse sensor streams into a unified world model represents substantial software engineering. The system must rapidly identify relevant objects, discard irrelevant environmental details, predict how objects will move during manipulation, and detect when reality diverges from expectations. The computational complexity of real-time sensor fusion and decision-making on a mobile platform has historically been prohibitive; the new Atlas achieves this through optimized neural network architectures that balance accuracy and inference latency on the onboard compute platform.

Power and Operational Duration

The battery system addresses one of the most persistent limitations of mobile robotics. Earlier research platforms achieved perhaps 1-2 hours of continuous operation before requiring recharge. The new commercial platform targets 8-10 hour shifts—the standard industrial workday. Achieving this while maintaining the power density necessary for dynamic movement required advances in battery chemistry, power distribution, and energy-efficient algorithms.

Boston Dynamics reportedly integrated high-capacity lithium cells similar to those used in electric vehicles but customized for the weight and center-of-gravity constraints of a bipedal platform. The power management system implements intelligent load shedding—reducing less critical computational tasks when battery reserves drop—to maintain core functionality even as energy depletes. Fast-charging capability targets 4-6 hours for a full recharge, enabling two shifts of operation per day with a single battery set.

Energy consumption varies dramatically by task. A stationary manipulation task (arms extended working on an assembly line) consumes far less power than continuous walking with dynamic tasks (mobile bin-picking across a warehouse). Field testing across diverse use cases informs realistic battery life predictions for different deployment scenarios. This granular understanding enables customers to accurately forecast charging infrastructure requirements and schedule robot tasks for maximum energy efficiency.

Technical Capabilities Enabling Factory Deployment

Computer Vision and Object Recognition

The visual perception system represents integration of multiple state-of-the-art computer vision approaches. Instance segmentation networks identify individual objects within cluttered scenes. 6D pose estimation determines the complete 3D position and orientation of objects, critical for precise manipulation. Semantic segmentation classifies regions (gripper, parts, obstacles, safe zones) to inform navigation and grasping decisions. Anomaly detection identifies objects or configurations outside the distribution of training data, enabling safe failure modes when encountering unexpected conditions.

These vision systems operate end-to-end on the onboard compute platform without external processing. The latency for visual perception and decision-making typically falls in the 200-500 millisecond range, balancing accuracy against the responsiveness necessary for safe robot movement. For comparison, human reaction times range from 200-500 milliseconds for simple tasks, suggesting Atlas' perception responsiveness aligns with human performance.

Training data remains the critical constraint. The more diverse the visual scenarios encountered during development, the better the system generalizes to novel factory environments. Boston Dynamics has invested heavily in synthetic data generation—using simulated environments and domain randomization to create vast training datasets without requiring millions of real-world examples. Transfer learning approaches allow models trained on generic vision datasets to rapidly specialize to specific factory environments with relatively small quantities of real demonstration data.

Task Learning and Adaptation

Atlas doesn't require complete reprogramming for each new application. The learning from demonstration framework enables humans to teach tasks by performing them while the robot observes. The system extracts key milestones and decision points from the human demonstration, then learns the skill through combination of imitation and reinforcement learning. A human might demonstrate bin-picking (grasping parts from a bin and placing them correctly) a dozen times, and the robot learns the generalizable strategy while practicing extensively to optimize its execution.

This capability dramatically accelerates deployment timelines. Rather than 8-12 weeks of engineering to implement a new task, deployment might require 1-2 weeks of demonstration, configuration, and practice. As the robot encounters edge cases (unusual part orientations, unexpected obstacles), humans can provide targeted correction, and the system incrementally improves. Over time, a single robot accumulates experience across diverse conditions, making its performance more robust and its capability to handle novel situations more reliable.

Safety Architecture and Human Interaction

Operating in human-occupied factory environments requires sophisticated safety systems. Force-limiting controls restrict the maximum force the robot can exert, preventing severe injury even if collision occurs. Motion planning algorithms explicitly consider human safety zones and adjust movement speed based on proximity to human workers. Tactile sensors throughout the body enable the robot to detect unexpected contact and immediately decelerate, minimizing impact severity.

The safety architecture implements multiple independent control layers. The primary control system routes movement commands through force limiters. A separate hardware-based safety monitor can immediately shut down actuators if safety thresholds are violated, without requiring software intervention. This redundancy ensures that software failures cannot result in unsafe behavior—the robot physically cannot exert dangerous forces or acceleration.

Collaborative operation modes enable safe shared workspaces. In these modes, the robot reduces speed and force output when humans enter nearby areas, enables humans to physically guide the robot by applying force to its body (the force-sensing system detects human input and adjusts behavior accordingly), and continuously monitors safety constraints. Extensive testing has validated that these safety systems enable Factory Mutual Insurance and other safety certifiers to approve Atlas for human-shared environments.

Atlas's humanoid form factor and advanced locomotion and manipulation capabilities make it viable for integration into human-centric environments without requiring facility modifications.

Real-World Use Cases: Where Humanoid Robots Create Measurable Value

Manufacturing and Assembly Operations

The primary initial deployment focus centers on manufacturing and assembly tasks where Boston Dynamics has validated strongest returns on investment. Traditional automation—fixed-position robots and specialized equipment—excels at high-volume, unchanging tasks but requires expensive system redesign when production models change. A manufacturing facility that produces three vehicle variants faces the choice of either running multiple specialized assembly lines (high capital cost) or constantly reworking automation equipment (expensive and time-consuming).

Atlas addresses this variability problem through generalized capabilities. A single robot can switch between assembly tasks by learning new demonstrations. A manufacturer can deploy the same Atlas hardware across multiple assembly lines, moving it to wherever current production demand concentrates. This flexibility has substantial economic value in industries with volatile production schedules or frequent product variations. Early ROI modeling suggests that flexibility benefits alone can justify deployment in environments with production changes occurring quarterly or more frequently.

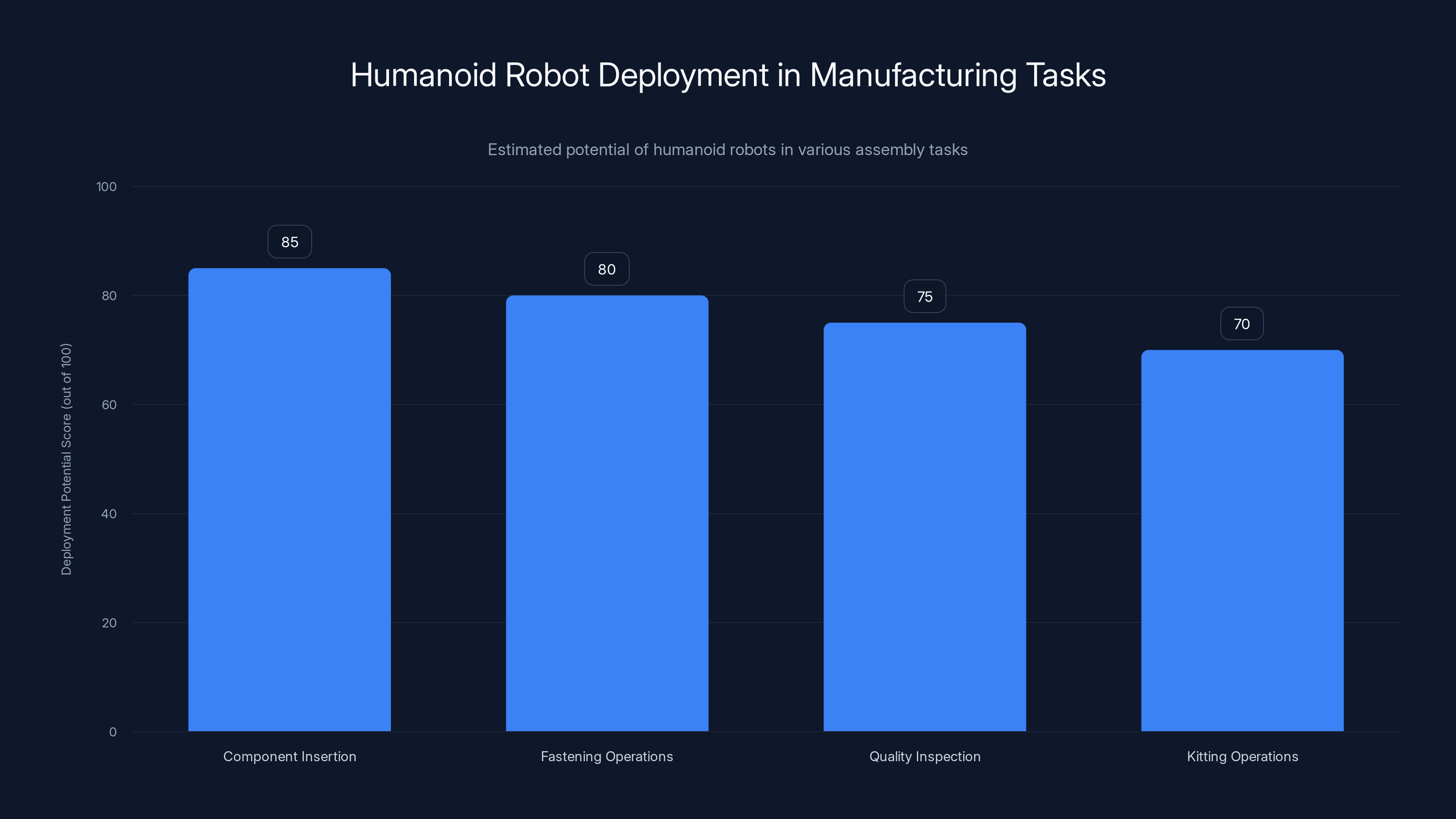

Specific assembly tasks showing strong deployment potential include component insertion (placing parts into larger assemblies), fastening operations (inserting screws, bolts, or other fasteners), quality inspection (examining completed assemblies for defects), and kitting operations (assembling collections of parts required for downstream work). These tasks share characteristics: they're currently labor-intensive, don't require extreme precision (millimeter-level accuracy), benefit from flexibility across product variants, and occur in high-volume contexts where robotics economics are favorable.

A case study pattern emerging from beta deployments: A mid-size automotive supplier deployed Atlas for component fastening. Manual workers averaged 120 fastened components per hour with high variability based on fatigue. Atlas demonstrated consistent performance at 145 components per hour, with uniform quality and no fatigue-related performance degradation. The economic calculation becomes straightforward: annual savings from higher throughput plus reduced quality failures typically exceed the annual robot operating cost within 12-18 months, with the robot continuing to generate value for 5-7 years of operational life.

Warehouse and Logistics Operations

Warehouse automation represents a massive market opportunity. Current industry practice uses a combination of human workers, conveyor systems, and specialized mobile robots (like automated guided vehicles). But most warehouse work resists complete automation because it requires general-purpose object manipulation and environmental adaptation. When Amazon attempted to fully automate fulfillment centers, they discovered that 20-30% of tasks still required human intervention because of the environmental variability—items with irregular shapes, fragile packaging, unknown contents, or unexpected configurations that frustrate traditional automation.

Atlas addresses this "long tail" of warehouse tasks. Piece picking (selecting individual items from shelves or bins for order fulfillment) remains heavily human-dependent despite decades of automation attempts. A humanoid robot that can navigate warehouse aisles, reach shelves at human height without special equipment, manipulate delicate items, handle unexpected packaging, and adapt to new product flows creates profound value. Initial deployment targets suggest Atlas might handle 60-70% of piece-picking tasks autonomously in its first generation, with human workers handling the exception cases that require judgment or complex reasoning.

The logistics use case economics diverge somewhat from assembly. Warehouses are sensitive to labor availability, making automation attractive independent of pure productivity calculations. A facility unable to recruit sufficient workers faces a choice between limiting operating capacity, paying premium wages, or deploying automation. Atlas shifts the economic equation by providing flexible, general-purpose labor that doesn't demand competitive wages or face fatigue-related productivity loss. The financial model focuses on labor cost savings rather than quality improvements or throughput gains—and labor cost savings in warehouses are substantial, making the economics compelling even if Atlas productivity merely matches human workers rather than exceeding them.

Hazardous Environment Operations

Humanoid robots enable work in environments dangerous or toxic for human workers. Chemical manufacturing, nuclear facility maintenance, and mining operations all feature tasks that human workers currently perform despite significant safety risks. Atlas could perform dangerous inspections, maintenance, or material handling while remote operators supervise from safe locations. This represents perhaps the strongest ethical case for humanoid robotics—eliminating human exposure to cancer-causing chemicals, radiation, or physical danger.

The technical requirements in hazardous environments differ slightly from normal manufacturing. Radiation tolerance demands sealed electronics and specialized shielding for sensitive components. Chemical resistance requires different material selections for external surfaces. Remote operation capability needs priority when human operators can't be on-site. These modifications are straightforward compared to the core robotics challenges; if Atlas works well in normal environments, adaptation to hazardous contexts is primarily engineering rather than fundamental research.

The commercial timeline for hazardous-environment deployment might actually be faster than conventional manufacturing because of stronger regulatory approval and fewer competing solutions. No other platform offers comparable capabilities for human-level task performance in genuinely dangerous conditions, reducing the alternative options customers might evaluate.

Construction and Infrastructure Maintenance

Construction automation has long been considered a robot-resistant domain because of the environmental variability, safety requirements, and complex problem-solving. Yet construction labor shortages are acute and worsening in developed economies, creating strong incentive for automation. Tasks like structural inspection, equipment placement, finishing work, and material handling all have high labor costs and straightforward task definitions despite environmental variation.

Atlas' humanoid form factor proves particularly valuable in construction contexts. Construction sites are built for human workers—doorways, stairs, access points, material handling equipment. A robot that operates without requiring site modification has tremendous value. Early construction-focused pilots focus on interior finishing (painting, flooring, wall installation) where environmental conditions are relatively controlled but labor costs are high. Success in these initial deployments could expand the domain to more challenging site conditions as the system matures.

Economics and Deployment Timeline: Realistic Financial Modeling

Capital Costs and Deployment Economics

Boston Dynamics hasn't publicly announced pricing for commercial Atlas units, but industry analysis suggests acquisition cost in the

Total cost of ownership extends beyond hardware acquisition. Integration costs (adapting the robot to specific use cases, facility modifications, safety certification) typically add 30-50% to hardware cost. Operations and maintenance (scheduled maintenance, component replacement, software updates) average 15-20% of hardware cost annually. Energy consumption contributes modestly to operational expenses—a continuously operating Atlas might cost $8-15 per 8-hour shift in electricity. Human oversight (monitoring robot performance, intervening when necessary, managing task scheduling) typically requires 1-2 human operators per robot, though they can concurrently manage multiple robots in low-exception scenarios.

The economic calculation transforms across different use cases. In labor-scarce environments where alternative costs exceed

In labor-abundant environments where market wages are substantially lower, the economics depend on other factors—productivity improvements, quality gains, or operational flexibility. The productivity calculation becomes critical: if Atlas performs 20% faster than human workers on the same task, the labor cost savings improve enough to justify deployment even if wages are modest. Flexibility benefits in manufacturing environments with multiple product variants can justify deployment based purely on the ability to repurpose a single robot for different production tasks without expensive system reconfiguration.

Production Scaling Timeline

Boston Dynamics announced initial production volumes aimed at dozens to low hundreds of units through 2027, ramping to thousands annually by 2028-2030. This gradual scaling reflects several constraints. Manufacturing humanoid robots requires precision assembly comparable to automotive manufacturing—not straightforward to scale rapidly. The company wants to accumulate real-world operational data before massive production, ensuring product reliability across diverse deployment scenarios. Establishing customer support infrastructure capable of deploying and maintaining robots globally requires deliberate buildup.

This scaling trajectory informs realistic customer expectations. Organizations planning large-scale robotics deployments (hundreds or thousands of robots) likely won't achieve this at scale before 2030-2032, though pilot deployments of smaller numbers might occur significantly earlier. This timeline permits customer organizations to test the technology, develop operational expertise, integrate robots into facility planning, and validate financial models before committing to massive capital deployment.

The phased approach offers advantages. Early adopters get favorable pricing and implementation support in exchange for serving as reference deployments. They accumulate operational experience and refine processes before scale. Later adopters benefit from mature software, reduced hardware costs through manufacturing scale, and proven operational playbooks from reference customers. This pattern mirrors successful technology adoption cycles in previous industrial automation eras.

Financial Projections and Market Sizing

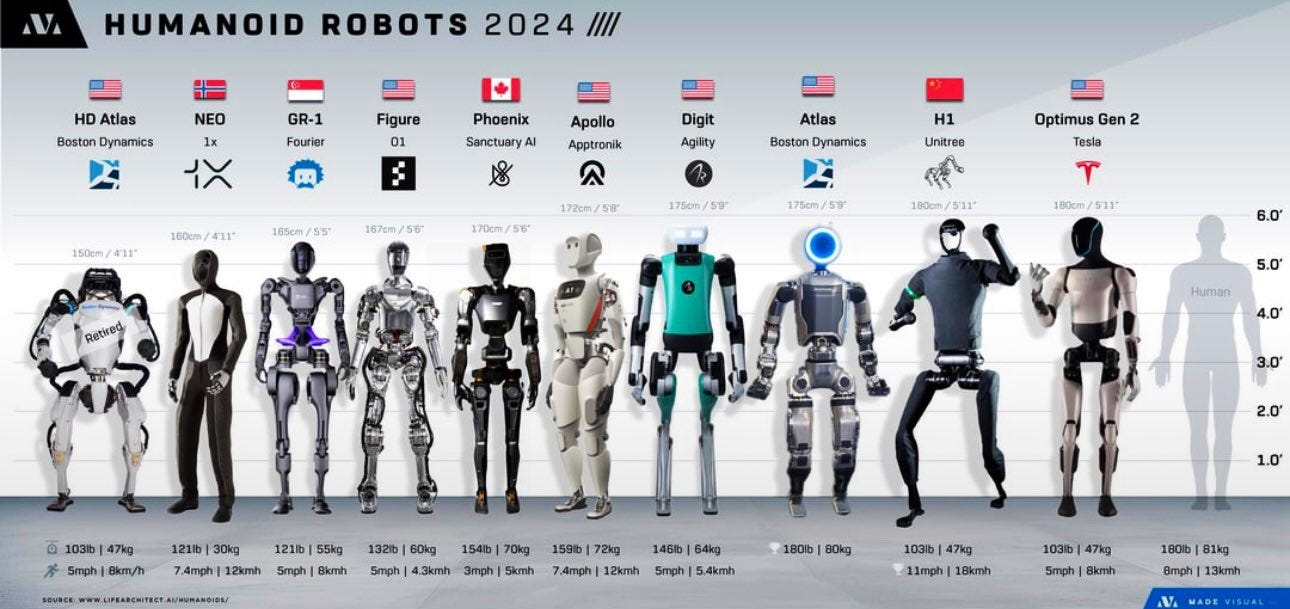

Analysts project the humanoid robot market could reach $50-100 billion annually by 2035 across all platforms and manufacturers. Boston Dynamics' share of this market remains uncertain—they're not the only company developing humanoid robots. Tesla's Optimus, Honda's Asimo, Boston Consultants' work, and numerous startups are pursuing similar goals. Competitive intensity will increase substantially as the market validates humanoid robot viability.

For Boston Dynamics, the financial opportunity justifies the investment but requires maintaining technological leadership through continuous improvements. The company is backed by Hyundai, which provides both financial resources and access to manufacturing expertise plus automotive industry deployment opportunities. The strategic positioning suggests Boston Dynamics is playing for dominance in a large emerging market rather than developing a niche product.

Customer acquisition will progress in waves correlated to capability maturity. Initial deployments in 2025-2027 target leading manufacturers and logistics operators—organizations with resources for pilot projects, tolerance for technical limitations, and strong internal expertise. Broader adoption in 2028-2032 targets mainstream manufacturers, construction companies, and logistics operators with proven success stories to reference and more mature product capabilities. Mass-market deployment beyond 2032 depends on achieving cost reduction, full autonomy for broader task sets, and cultural acceptance of humanoid robots in diverse work environments.

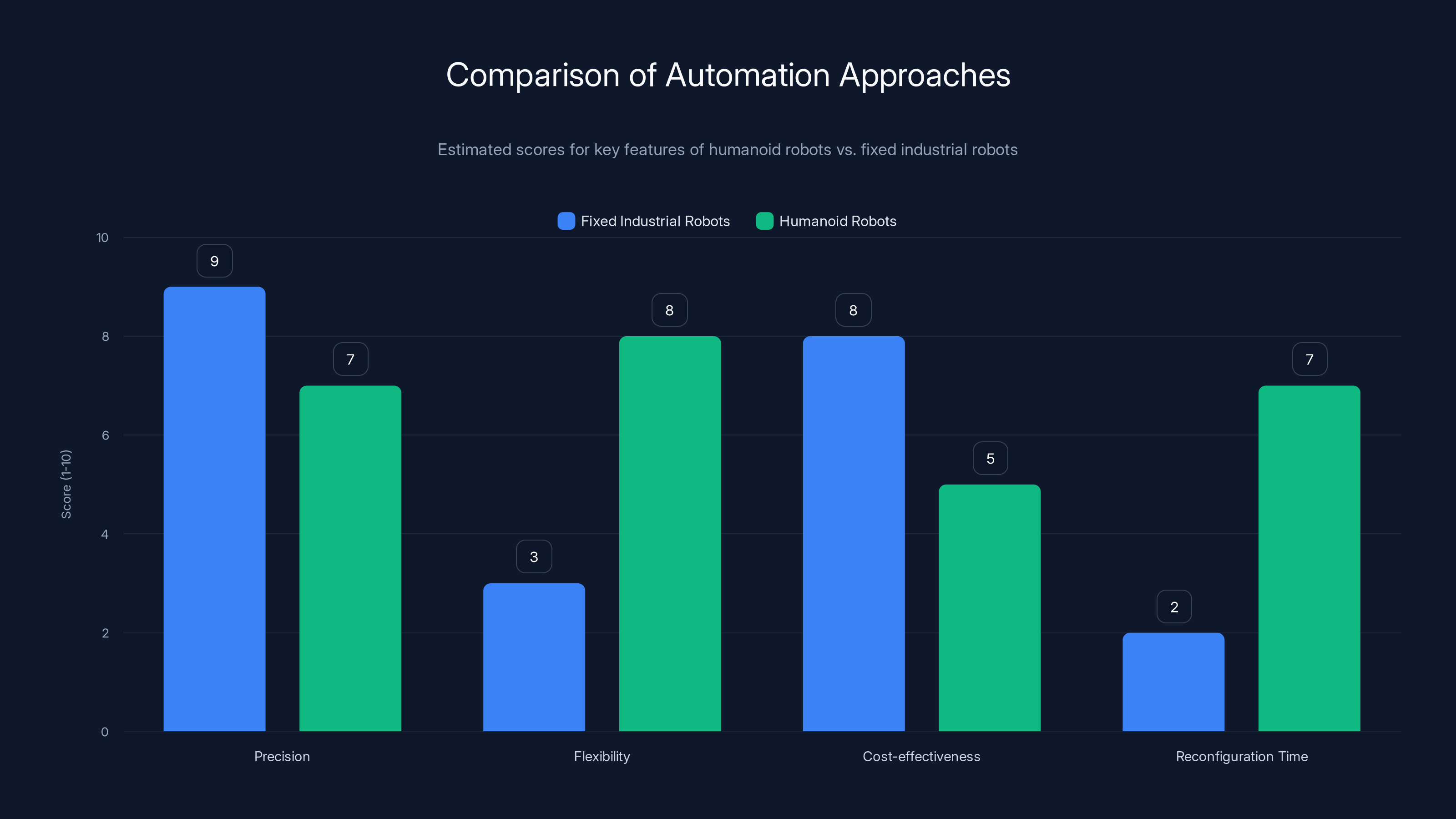

Fixed industrial robots excel in precision and cost-effectiveness but lack flexibility, requiring long reconfiguration times. Humanoid robots offer greater flexibility, making them suitable for environments with frequent changes. Estimated data.

Comparative Analysis: Humanoid Robots vs. Alternative Automation Approaches

Traditional Fixed Industrial Robots

Fixed-position industrial robots (articulated arms mounted on pedestals) remain the dominant automation platform, with over 500,000 units deployed globally. They offer extreme precision, speed, reliability, and cost-effectiveness for the applications they address—typically repetitive, high-volume manufacturing tasks requiring consistent accuracy. A robot welding automotive bodies executes identical movements thousands of times with millimeter precision. This capability remains irreplaceable for precise manufacturing.

However, fixed robots are environment-optimized for a specific task. Changing the production line requires extensive system reconfiguration, typically taking 4-12 weeks and costing

Atlas addresses the flexibility problem that fixed robots cannot solve without expensive reconfiguration. In scenarios with frequent production changes, varied part configurations, or multiple product lines, the flexibility value proposition for humanoid robots becomes compelling. A manufacturer producing 10 different products on the same assembly line faces a choice: maintain 10 specialized robotic systems (capital-intensive, operationally complex) or deploy 3-5 Atlas units that flexibly switch between lines as demand varies. The flexibility premium justifies humanoid robot deployment in environments where fixed robots require constant reconfiguration.

Specialized Mobile Robots and Autonomous Vehicles

Autonomous mobile robots (AGVs and AMRs) dominate warehouse and logistics automation, with companies like Amazon Robotics, Kiva Systems, and Fetch Robotics deploying tens of thousands of units. These platforms excel at item transportation—moving goods from Point A to Point B—and they're substantially cheaper than humanoid robots, with acquisition costs around

Mobile robots, however, cannot perform object manipulation. They transport goods but don't grasp, place, or assemble items. This limitation creates the "human-in-the-loop" operational model prevalent in modern warehouses: robots handle transportation, humans handle the skilled manipulation. This hybrid approach works reasonably well but doesn't fully eliminate human labor for physical tasks. Atlas addresses the manipulation bottleneck that mobile robots cannot overcome—a humanoid robot that walks and grasps items could theoretically replace a larger fraction of warehouse labor.

The competitive positioning isn't strictly "humanoid robots versus mobile robots." Rather, integrated solutions combining both might prove optimal. Imagine a warehouse where mobile robots handle high-volume transportation of standard containers while humanoid robots handle the complex piece-picking and exception cases. This hybrid approach leverages strengths of both platforms while maintaining lower total cost of ownership compared to deploying humanoid robots for all tasks.

Collaborative Robots (Cobots)

Collaborative robots—designed for close human-robot interaction with safety constraints—represent a growing market ($2+ billion annually). Platforms like Universal Robots, ABB's Go Fa, and others enable safe human-robot shared workspaces. A cobot might work at an assembly station alongside a human operator, performing specific subtasks while the human performs other subtasks, working together on the same product.

Cobots achieve safety through force limiting (restricting maximum force output) and safety-certified design, allowing them to work inches from human workers. They're typically cheaper than humanoid robots (

Atlas differs from cobots in autonomy level and task breadth. A cobot works in close human supervision, executing defined tasks with human operators handling problem-solving and decision-making. Atlas aspires to greater autonomy, executing complex multi-step tasks with minimal human intervention beyond initial task specification. A cobot and human working together might assemble 100 units per shift; Atlas working autonomously might assemble 150 units per shift, freeing the human for higher-value tasks or enabling the facility to operate without human labor for some periods.

The strategic positioning suggests different market niches. Cobots excel in scenarios requiring human-robot collaboration, strong human oversight, or moderate cost sensitivity. Atlas targets scenarios enabling greater autonomy, flexibility across tasks, and reduction in human labor where capital investment is justified by labor costs or labor availability constraints. Many facilities will deploy both—cobots for specific collaborative tasks, humanoid robots for autonomous operations—rather than viewing them as competing solutions.

AI-Powered Workflow Automation and Soft Robotics

For teams seeking process automation without physical robotics, platforms like Runable offer AI-powered workflow automation that reduces manual effort through intelligent automation of decision-making and knowledge work. While Runable focuses on information workers and document generation rather than physical tasks, the strategic principle parallels humanoid robotics: automating tasks that traditionally required human judgment and effort.

For manufacturing contexts involving significant information work—production scheduling, quality documentation, supply chain management, work order generation—AI-powered automation complements physical robot deployment. A facility deploying humanoid robots for assembly still requires administrative automation for order management, quality reporting, and production planning. Organizations evaluating automation strategies should assess the complete automation opportunity including both physical tasks and information tasks, rather than viewing humanoid robotics as solving all automation needs.

The economic models diverge substantially. Physical automation (humanoid robots) requires significant capital investment but generates return through labor cost reduction or productivity improvement. Information automation (AI workflow tools) typically has lower implementation cost but operates in different value creation mechanisms—speed, accuracy, and human-hour savings in administrative work. Integrated strategies deploying both often achieve stronger total ROI than either approach independently.

Soft Robotics and Specialized Grippers

Soft robotics—robots with compliant, deformable bodies—promise different capabilities than rigid-bodied humanoids. A soft robotic gripper can manipulate delicate or irregularly shaped items (soft fruit, fabrics, complex assemblies) without damage. These grippers complement traditional rigid robots by enabling handling of items that damage easily or deform during grasping.

Boston Dynamics' Atlas incorporates some soft robotics principles in its hand design—the fingers have compliant joints and soft contact surfaces that prevent damage to delicate items. The full humanoid architecture, however, maintains overall rigidity necessary for powerful movement and dynamic locomotion. The strategic choice balances capability breadth (humanoid form factor enabling varied locomotion and manipulation) against specialization depth (soft robots achieving superior performance on specific delicate-item tasks).

Organizations with primarily delicate-item handling (like produce packing or electronics assembly) might deploy specialized soft robots rather than general-purpose humanoids. Those with mixed tasks requiring both delicate and powerful manipulation benefit from humanoid robots' flexibility. This again suggests complementary solutions rather than strict competition—different automation platforms excel in different domains, and large facilities often deploy multiple robot types.

Manufacturing Industry Response and Adoption Preparedness

Current Capabilities vs. Industry Requirements

Manufacturing organizations evaluating Atlas deployment need realistic assessment of current capabilities versus manufacturing requirements. Boston Dynamics has demonstrated impressive performance on scripted tasks in controlled environments. The company's beta deployments have occurred in manufacturing facilities with moderate environmental complexity and under relatively controlled conditions. The generalization question remains partially open: how does Atlas perform when deployed in genuinely complex factory environments with unexpected variations, poorly lit conditions, temperature extremes, or contaminated air common in heavy manufacturing?

Early field data suggests performance degrades gracefully as environmental complexity increases. The robot might achieve 95%+ task success rates in ideal conditions and 85-90% in typical factory conditions with occasional human intervention required for exception cases. This graceful degradation is far better than complete failure but means deployment planning should account for human oversight remaining necessary for significant minority of tasks, at least through the first generation of commercial systems.

The learning capability provides pathway for improvement over time. As the system encounters diverse factory conditions, field data feeds back to Boston Dynamics for model improvement. Future software updates progressively improve performance in complex environments without requiring hardware changes. Customers participating in early deployments essentially contribute to system improvement while benefiting from better performance over the deployment timeline.

Integration Challenges and Hidden Costs

Deployment success depends on far more than robot capabilities. Facility integration presents substantial challenges. The robot requires electrical infrastructure (dedicated power circuits to handle 10-20 k W peak draws), communication network (wireless networks reliable enough for robot operation), physical workspace modification (clearing areas for robot movement, improving lighting, addressing floor conditions). These integration costs frequently surprise customers because they're invisible until detailed implementation planning occurs.

Process redesign often proves equally important. Manufacturing processes evolved around human worker capabilities and behaviors. Deploying a robot sometimes requires process modification to accommodate robot capabilities—changing how parts are presented to the robot, modifying assembly sequences to work with robot dexterity constraints, or restructuring workflows to separate robot-amenable tasks from those requiring human flexibility. Organizations underestimating process redesign effort often face disappointing deployment results.

Training and change management address the human side of robotics deployment. Factory workers react to robots with legitimate concerns about job security, changes to work environment, and whether they can trust the system. Organizations successfully deploying robots invest substantially in worker training, communication about deployment plans, and worker involvement in implementation planning. Facilities treating robots as purely technical projects without addressing human dimensions frequently encounter resistance and underperformance.

Maintenance and support infrastructure must mature in parallel with deployment. Initially, Boston Dynamics will provide field service support for maintenance and troubleshooting. As deployments scale, the company will need to build certified service networks or train customer personnel on advanced troubleshooting. Organizations planning large-scale deployment should identify and train robot-capable technicians within their workforce starting years before deployment.

Sector-Specific Adoption Readiness

Automotive manufacturing shows highest near-term adoption potential. The sector has existing relationships with industrial robotics vendors, robust capital budgeting processes, and experience managing complex automation deployments. Major automotive suppliers are already conducting pilot programs, and deployment timelines target 2027-2029 for meaningful scale. The automotive sector's complex assembly requirements, high labor costs, and desire for increased production flexibility create compelling economics for humanoid robots.

Electronics manufacturing follows similar patterns with different urgency. High component miniaturization demands precision that challenges humanoid robots, but labor costs in some electronics manufacturing are substantial, creating deployment incentives. Initial deployments likely target lower-precision assembly tasks (wiring, component mounting, testing) before advancing to ultra-precision assembly.

Food and beverage processing faces regulatory challenges that slow adoption. Food safety regulations constrain robot design (sealed electronics, food-safe materials, cleanability), and industry risk-aversion around novel approaches means extensive validation before adoption accelerates. However, food manufacturing labor shortages are acute, suggesting eventual meaningful adoption once regulatory frameworks clarify and reference deployments demonstrate safety compliance.

Construction adoption timeline extends longer than manufacturing. The industry is more fragmented, risk-averse, and dependent on specialized knowledge. However, construction labor shortages are severe and worsening, creating strong long-term drivers for adoption. Early deployments will likely occur in large construction companies and construction technology-forward regions before broader adoption cascade.

Digital transformation can reduce labor inefficiency by 25% and costs

Competitive Landscape: Other Humanoid Robot Developments

Tesla's Optimus Program

Tesla is developing a humanoid robot called Optimus with target deployment in Tesla factories initially, broader commercialization later. The program leverages Tesla's expertise in large-scale manufacturing automation, AI systems, and embedded computing. Unlike Boston Dynamics' research-focused path, Tesla's approach emphasizes manufacturing scale and cost reduction from early stages.

Tesla has publicly stated ambitions to reduce Optimus per-unit cost to

Tesla's timeline remains less certain than Boston Dynamics' public commitments. The company has demonstrated Optimus prototypes but hasn't announced specific production dates or deployment timelines. Tesla's manufacturing expertise is undeniable, but developing truly autonomous humanoid systems proves more challenging than manufacturing expertise alone. The competitive landscape likely supports both companies succeeding given the enormous market opportunity—rather than one platform decisively dominating.

Other Significant Developments

ABB (automation giant) is developing humanoid-inspired robots with focus on manufacturing precision and integration with existing ABB automation ecosystems. Hyundai (Boston Dynamics' parent) is developing related platforms and manufacturing-focused applications. Universal Robots (cobot leader) is exploring humanoid directions. Boston Consultants Group (yes, the consulting firm) invested in humanoid robotics development. Numerous startups (Sanctuary AI, Figure AI, Agility Robotics, and others) are pursuing specialized humanoid applications.

This competitive intensity suggests the humanoid robot market will likely feature multiple successful platforms serving different niches rather than a single dominant vendor. Manufacturing customers might deploy Boston Dynamics for complex assembly, Tesla for cost-conscious high-volume environments, and specialized platforms for specific vertical applications. This plurality of solutions benefits customers through competition driving innovation and favorable pricing.

Regulatory, Safety, and Ethical Considerations

Safety Certification and Regulatory Approval

Factory automation robots currently operate under established safety standards (ANSI/RIA R15.06 in North America, ISO/TS 15066 globally). These standards address hazard analysis, safe design practices, protective features, and human-robot interaction. Deploying Atlas in human environments requires demonstrating compliance with applicable standards and obtaining safety certification from recognized bodies like Factory Mutual Insurance or equivalent authorities in other regions.

Boston Dynamics has invested substantially in safety engineering and validation. The company has demonstrated force-limiting capabilities, tactile sensing that enables safe contact detection, and motion planning algorithms that maintain safe distances from humans. Independent safety testing suggests Atlas can achieve comparable safety to trained industrial robots when properly configured and operated. However, the first generation may require more human oversight in mixed environments than some customers desire—essentially operating as an assisted automation system rather than fully autonomous system.

Regulatory Approval processes will evolve as humanoid robots proliferate. Initial deployments occur under relatively close regulatory scrutiny, with detailed safety plans and monitoring requirements. As successful deployments accumulate, regulatory confidence increases and approval timelines shorten. Organizations planning early-stage deployments should anticipate extended regulatory review cycles—potentially 6-12 months—before safety certification and authority-to-operate approval.

Labor Impact and Workforce Transition

Humanoid robot deployment will displace human labor in various roles. This reality requires honest discussion rather than techno-optimistic claims that "robots only create jobs." While history shows automation ultimately creates more jobs than it eliminates, the transition period creates genuine worker hardship. Manufacturing workers whose roles become automated face job displacement, retraining needs, and potential wage reduction if reemployed in different roles.

Responsible deployment requires organizations to address worker impact proactively. This includes transparent communication about deployment plans, retraining programs for displaced workers, job placement assistance, and wage protection programs during transitions. Some organizations have achieved positive outcomes through worker involvement in deployment planning—training workers as robot technicians, giving workers priority in retraining programs, and designing deployment to minimize rather than maximize displacement.

Policy makers will increasingly address robot-driven labor displacement through education investments, social safety nets, and tax policies (robot taxes, automation taxes, or similar mechanisms to fund transition support). Organizations deploying humanoid robots should expect increased scrutiny of labor practices and be prepared to demonstrate responsible management of workforce transitions.

Ethical Considerations and Broader Societal Impact

The philosophical question of robot consciousness, rights, and moral status remains speculative—Atlas is a tool, not a conscious entity, and treating it as such misframes the real questions. The genuine ethical considerations involve how robots impact human flourishing, economic opportunity, and social stability. Displacement without transition support harms workers. Productivity gains captured entirely by capital owners while workers experience wage stagnation generates inequality. Deployment driving further wealth concentration creates political instability.

These are not inherent to robot technology but reflect how deployment decisions distribute benefits and burdens. Organizations deploying humanoid robots responsibly ensure that productivity gains are shared with affected workers, that transition support is robust, and that workers are treated as stakeholders in decisions affecting their livelihoods. This approach requires different decision-making frameworks than pure capital optimization, but it's increasingly expected by workers, customers, and regulators.

Estimated data suggests that humanoid robots like Atlas have high potential in flexible manufacturing tasks, with component insertion having the highest deployment potential.

Practical Deployment Strategy: How Organizations Should Approach Humanoid Robot Adoption

Phased Deployment and Pilot Programs

Successful robot deployments follow phased approaches rather than attempting large-scale implementation immediately. The typical pattern: a pilot program tests technical capability and economic model at limited scale, builds organizational expertise, and generates reference data for later scaling. A manufacturing facility might deploy 2-3 Atlas units for 8-12 months, carefully monitoring performance, costs, and worker integration before deciding on broader deployment.

Pilot phase objectives should include: validating technical capability in your specific environment, establishing true cost of ownership including integration and support, developing worker training and management approaches, identifying process modifications that improve robot effectiveness, and building internal expertise that enables future scaling. This investment in pilot infrastructure—seemingly redundant compared to direct large-scale deployment—often proves cost-effective by avoiding expensive mistakes at scale.

The phased approach also allows technology maturation to occur in parallel with your capability development. The humanoid robot technology is improving rapidly; hardware in 2025 will differ from hardware in 2027, and software capabilities will advance even faster. Organizations deploying pilots in 2025-2026 can refine operational approaches and then deploy more capable systems in subsequent phases, getting better returns on later investments because implementation expertise exists.

Team Assembly and Expertise Development

Successful deployment requires multidisciplinary team spanning manufacturing engineering, IT/networking, safety, HR, and operations. Manufacturing engineering identifies automation opportunities and understands current processes. IT ensures network reliability and system integration. Safety ensures compliance with regulations and standards. HR manages worker communication and training. Operations understands day-to-day execution. Organizations missing any discipline often encounter predictable problems in their blind spots.

Technical expertise becomes critical. Humanoid robots are sophisticated systems requiring people who understand robotics, control systems, machine vision, and software integration. Few organizations have this expertise internally; most require external partners (integrators, vendors, consultants) to supplement internal teams. The strategic choice involves developing sufficient internal expertise to manage vendors effectively and maintain systems over their operational life, while outsourcing specific technical work to specialists.

Working with specialized system integrators who've deployed humanoid robots in similar contexts accelerates implementation. These partners understand typical challenges, know solution patterns, and can avoid mistakes while improving timelines. The integration cost adds to overall project expense but typically returns that investment through faster deployment and better outcomes.

Measuring Success and Continuous Improvement

Defining success metrics before deployment prevents post-hoc justification of disappointing results. Useful metrics typically span: productivity (output per unit time), quality (defect rates, consistency), cost (labor cost saved, ROI timeline), safety (incidents, near-misses), worker satisfaction (survey data, retention, engagement), and technology performance (uptime percentage, exception rates). Monitoring these metrics continuously enables rapid identification of issues and adjustment of operational approaches.

The continuous improvement mindset treats initial deployment as the beginning of multi-year optimization rather than endpoint. Modest performance in early months should trigger investigation and refinement rather than abandonment. Perhaps robot performance is limited by process design—modifying how parts are presented to the robot might improve success rates substantially. Perhaps worker training is inadequate—more detailed training might eliminate exceptions that now require human intervention. Perhaps environmental factors (lighting, temperature) are suboptimal—addressing these might yield significant gains.

Organizations often find that robot performance improves steadily through the first 12-24 months of operation as accumulated experience drives optimization. Setting overly strict success criteria for early months risks prematurely judging the program as failed when patient optimization would yield success. Conversely, setting success criteria so loose that any deployment is deemed successful prevents recognition of actual problems requiring remedy.

Alternative Approaches Worth Considering Alongside Humanoid Robots

Process Automation and Digital Transformation

Before deploying physical robots, many organizations benefit from optimizing existing processes. Manufacturing facilities sometimes operate with inefficient workflows, manual material handling, and information systems disconnected from physical operations. A comprehensive process audit identifying optimization opportunities often reveals that 20-30% of labor is consumed by inefficient processes addressable through digital transformation and workflow redesign rather than robotics.

Example: A manufacturing facility discovers that workers spend 3+ hours daily managing work orders, locating materials, and documenting completed work. This administrative overhead could be reduced through digital work order systems, automated material tracking, and real-time production dashboards. The cost of implementing these information systems (

For information-intensive industries, AI-powered workflow automation platforms address administrative overhead. Rather than automating physical tasks, these systems automate decision-making and knowledge work. A manufacturing facility scheduling production runs, managing supply chains, and generating quality reports could deploy AI workflow automation to optimize scheduling, predict supply requirements, and automatically generate reports. Systems like Runable enable teams to build custom automation workflows using AI agents, potentially eliminating substantial human effort in administrative roles at lower cost than physical robots.

Workforce Augmentation Through Exoskeletons

Exoskeletons—wearable robotic devices that amplify human strength and endurance—represent an alternative to humanoid robots for physical tasks. A worker wearing an exoskeleton can manipulate heavy items, work extended periods without fatigue, and perform repetitive tasks with reduced physical strain. This approach maintains human control and decision-making while enhancing human physical capability. For tasks requiring human judgment, dexterity, or problem-solving, exoskeletons can improve productivity and worker safety without eliminating jobs.

Exoskeletons cost

Hybrid Approaches Combining Multiple Automation Types

Most sophisticated deployment strategies don't choose between humanoid robots, fixed robots, mobile robots, cobots, and other alternatives. Instead, they integrate multiple automation types optimized for different parts of the process. For example, a manufacturing facility might deploy:

- Fixed industrial robots for high-precision, high-volume assembly (welding, fastening, testing)

- Mobile robots for material transportation (feeding assembly stations, removing completed work)

- Collaborative robots for complex assembly tasks requiring flexibility and human-robot collaboration

- Humanoid robots for flexible, varied tasks requiring general-purpose dexterity but less extreme precision

- Exoskeletons for heavy lifting tasks where human control remains important

This integrated approach yields superior overall economics compared to any single automation technology. Each technology handles the tasks it excels at, creating layered efficiency gains that exceed what any individual platform could achieve. The complexity increases, but mature automation factories routinely manage multiple robot types effectively.

FAQ

What is Boston Dynamics' Atlas and why is it transitioning to commercial product?

Boston Dynamics' Atlas is a humanoid robot—a bipedal platform with human-proportional limbs, sophisticated hands, and advanced perception systems. For over a decade, Atlas was a research platform used to advance robotics technology. The company announced that Atlas is transitioning to a commercial product designed for factory deployment beginning in 2028. This transition reflects Boston Dynamics' determination that the technology has matured sufficiently for real-world industrial applications.

How does the new commercial Atlas differ from the research version?

The commercial Atlas incorporates substantial hardware redesigns focusing on durability, thermal management, battery life, and maintainability. It uses industry-standard components where possible, reducing procurement complexity. The actuator technology achieves better efficiency for longer operational duration. The software stack has matured to handle real-world environmental variability rather than controlled laboratory scenarios. These changes address the transition from impressive demonstrations to reliable industrial systems.

What are the primary use cases where humanoid robots create measurable value?

Initial deployment focus targets: manufacturing assembly (component insertion, fastening, quality inspection), warehouse operations (piece picking, material handling), hazardous environment work (chemical manufacturing, radiation exposure, toxic atmospheres), and construction tasks (finishing work, equipment placement). These use cases share characteristics of high labor costs, environmental variability, and tasks benefiting from flexible, general-purpose capability. Read more about specific use cases in our detailed guide section.

What are the realistic economics and payback timeline for humanoid robot deployment?

Capital cost for Atlas is estimated at

How does Atlas compare to traditional fixed industrial robots and specialized alternatives?

Fixed industrial robots excel at high-precision, high-volume, unchanging tasks but require expensive reconfiguration when production changes. Atlas addresses the flexibility problem—it can switch between tasks by learning new demonstrations, valuable in environments with frequent production changes. Specialized robots (mobile robots, cobots, soft robots) excel in specific niches. Integrated strategies often deploy multiple robot types rather than choosing a single platform. Each technology has distinct strengths; successful automation factories typically combine multiple approaches rather than selecting one.

What safety features and certifications enable humanoid robots to operate in human environments?

Atlas incorporates force-limiting controls preventing dangerous force levels, tactile sensors enabling detection of unexpected contact, and motion planning algorithms maintaining safe distances from humans. Boston Dynamics has conducted extensive independent safety testing with certification bodies. However, first-generation commercial systems likely operate under relatively close human oversight rather than complete autonomy—essentially assisted automation requiring human intervention for exception cases. As deployments prove safety records, regulatory confidence will enable greater autonomy.

What are the realistic deployment timelines for organizations planning to adopt humanoid robots?

Initial production volumes through 2027 will support dozens to low hundreds of units deployed in pilot programs and reference customers. Meaningful scale deployments (hundreds to low thousands) likely occur 2028-2030. Organizations planning large-scale deployments (thousands of robots) should realistically target 2030-2032 timelines. Phased deployment approaches starting with pilot programs in 2025-2026 allow time for technology maturation, organizational capability development, and process optimization before larger investment.

What alternative automation approaches should be evaluated alongside humanoid robots?

Worth considering: process optimization and digital transformation (addressing administrative overhead through workflow redesign), AI-powered workflow automation (automating decision-making and knowledge work using platforms like Runable), exoskeletons (augmenting human capability rather than replacing workers), and specialized robots (fixed robots for precision, mobile robots for transport, cobots for collaboration). Integrated strategies combining multiple automation types often achieve better results than choosing a single solution. The optimal approach depends on your specific tasks, labor market context, and organizational priorities.

What role does machine learning play in Atlas operation and task learning?

Machine learning enables task learning from demonstration and perception in variable environments. A human can teach the robot new tasks by demonstrating them several times; the robot learns the skill through imitation learning plus reinforcement learning. Once learned, the robot can perform the task across environmental variations better than rigid programmed instructions. Computer vision models handle object recognition, pose estimation, and anomaly detection to enable autonomous operation. As the robot encounters diverse real-world conditions, field data informs model improvements deployed as software updates.

What regulatory and labor considerations should organizations address during deployment?

Safety certification from recognized bodies is required before deployment. Organizations should anticipate 6-12 month regulatory review cycles for first deployments. Labor considerations include transparent communication with workers about deployment plans, retraining programs for displaced workers, job placement assistance, and wage protection during transitions. Organizations deploying humanoid robots responsibly ensure productivity gains are shared with affected workers and treat workers as stakeholders in decisions affecting their livelihoods, not merely costs to be optimized.

How should organizations approach phased deployment and pilot programs?

Successful deployments follow phased approaches rather than large-scale immediate implementation. A pilot program (8-12 months with 2-3 units) tests technical capability, validates economics, develops worker training approaches, and identifies process improvements. Pilot objectives include: validating technical capability in your environment, establishing true cost of ownership, developing worker integration approaches, identifying process modifications, and building internal expertise. This investment prevents costly mistakes at scale and generates data informing larger deployments. Define success metrics (productivity, quality, cost, safety, worker satisfaction) before deployment and monitor continuously to drive continuous improvement.

Conclusion: The Humanoid Robot Inflection Point and Strategic Planning

Boston Dynamics' transition of Atlas from research platform to commercial product marks a genuine inflection point in automation history. Unlike previous robotics hype cycles, this announcement builds on a decade of methodical research, real-world testing, and demonstrated capability. The company has thought carefully about commercialization—they're not attempting to replace all human labor overnight but rather addressing specific, high-value use cases where humanoid robots create clear economic benefit.

However, the announcement also reflects beginning, not end, of development. First-generation commercial Atlas will have limitations—scenarios where the robot struggles, situations requiring human intervention, productivity that doesn't dramatically exceed well-trained human workers. The product will mature over time through accumulated field experience, iterative hardware improvements, and advancing machine learning models. Organizations deploying early should expect steady performance improvement over 3-5 years as the product matures and deployment expertise accumulates.

The competitive landscape will intensify substantially. Tesla's Optimus, specialist platforms from other manufacturers, and existing automation companies adapting to humanoid opportunities will provide multiple platform choices. This plurality benefits customers through competition, but also increases decision complexity. Rather than a single "best" humanoid robot, organizations will choose among platforms optimized for different niches—cost leadership, capability leadership, manufacturing integration, specialized verticals. The market will support multiple successful platforms because the opportunity is large enough for multiple winners.

Strategic considerations for organizations evaluating humanoid robot adoption:

First, assess your specific automation opportunity. Does your primary challenge involve high labor costs, labor availability constraints, production flexibility requirements, or hazardous work conditions? Different drivers justify automation through different mechanisms. Labor-scarce environments and environments requiring product/task flexibility show strongest near-term economic cases. Evaluate whether your problem is truly physical automation or whether process optimization or workflow automation might address your needs more cost-effectively.

Second, build organizational capability systematically. Begin by developing robotics expertise through small pilots or partnerships with integrators. Identify and train people who will become your robot operations specialists. Ensure worker communication and training are planned and resourced properly. Understand the total cost of ownership beyond hardware acquisition. Most organizations underestimate integration, training, and operational management costs; realistic budgeting improves outcomes.

Third, integrate humanoid robots with other automation approaches. Rarely is humanoid robotics the entire answer. Process optimization reduces the automation burden. Workflow automation tools address administrative overhead. Fixed robots excel at specific tasks. Cobots enable human-robot collaboration. Mobile robots handle transportation. Exoskeletons augment human capability. Mature automation strategies combine multiple approaches rather than assuming one platform solves all problems.

Fourth, adopt a phased deployment approach. Start with controlled pilot programs, learn operational lessons, develop expertise, and validate economics before large-scale investment. Use pilot results to inform bigger deployment plans rather than making massive commitments based on vendor marketing claims. The phased approach adds time but reduces risk and often accelerates learning and optimization.

Fifth, manage workforce transition responsibly. Robot deployment will displace some human labor; this is an unavoidable reality. Organizations that handle transition poorly face worker resistance, reputational damage, and regulatory scrutiny. Those that invest in worker retraining, wage protection, and job placement often find that maintaining experienced workforce is more valuable long-term than pure cost optimization. The automation decision sets organizational culture—managing it responsibly builds trust and retention.

The humanoid robot opportunity is real and substantial. The economics work in appropriate contexts. The technology has matured sufficiently for commercial deployment. But success requires clear thinking about specific problems, realistic assessment of technology capabilities and limitations, systematic capability building, and responsible management of human impact. Organizations executing well on these dimensions will achieve significant competitive advantage through automation. Those treating humanoid robots as magical solution to all operational problems will likely be disappointed.

The future of manufacturing, logistics, and many other industries will feature humanoid robots working alongside, and eventually replacing, human workers in specific contexts. But that future develops through pragmatic, careful deployment—not through dramatic technological leaps alone, but through organizations systematically integrating new capabilities into evolving operational strategies. The time to begin planning is now, even if full-scale deployment is years away. Organizations that develop expertise and operational approaches early will execute deployments more successfully and achieve competitive advantage earlier than those waiting for the technology to mature further.

Key Takeaways

- Boston Dynamics Atlas transitions to commercial product with factory deployment timeline 2025-2028

- Humanoid robots create measurable value in flexible manufacturing, warehouse operations, and hazardous environments where generalized capability justifies capital investment

- Commercial Atlas incorporates substantial hardware redesigns for durability, efficiency, and maintainability compared to research platforms

- Economics favor humanoid robot deployment in labor-scarce environments with payback timeline of 12-18 months in appropriate contexts

- Strategic alternatives including fixed robots, mobile platforms, cobots, workflow automation, and exoskeletons serve different optimization objectives

- Successful deployments require phased approaches starting with controlled pilots, multidisciplinary teams, and realistic assessment of total cost of ownership

- Competitive landscape will feature multiple humanoid platforms with different strengths; integrated strategies combining multiple automation types often achieve superior results

- Responsible deployment addresses worker transition, realistic safety capabilities, and organizational readiness beyond pure technical specifications

- First-generation commercial systems likely operate under closer human oversight than full autonomy; technology matures through accumulated field experience

Related Articles

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Press Conference Live [2026]

- Humanoid Robots in 2026: The Reality Beyond the Hype [2025]

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Presentation Live [2025]

- [2025] Humanoid Robots in Industrial Settings: Transforming Efficiency

- Kodiak and Bosch Partner to Scale Autonomous Truck Technology [2025]

- Humanoid Household Robots: SwitchBot's Onero H1 & the Future of Home Automation [2025]