Introduction: The Clash Between Content Protection and Internet Freedom

Imagine being told you have 30 minutes to censor a website globally, with no court oversight, no due process, and no appeal. That's essentially what Italy's Piracy Shield law demands of tech companies. In January 2026, this collision between intellectual property enforcement and digital freedom came to a head when Italy's communications regulatory agency, AGCOM, slapped Cloudflare with a €14.2 million fine (approximately $17 million USD) for refusing to comply.

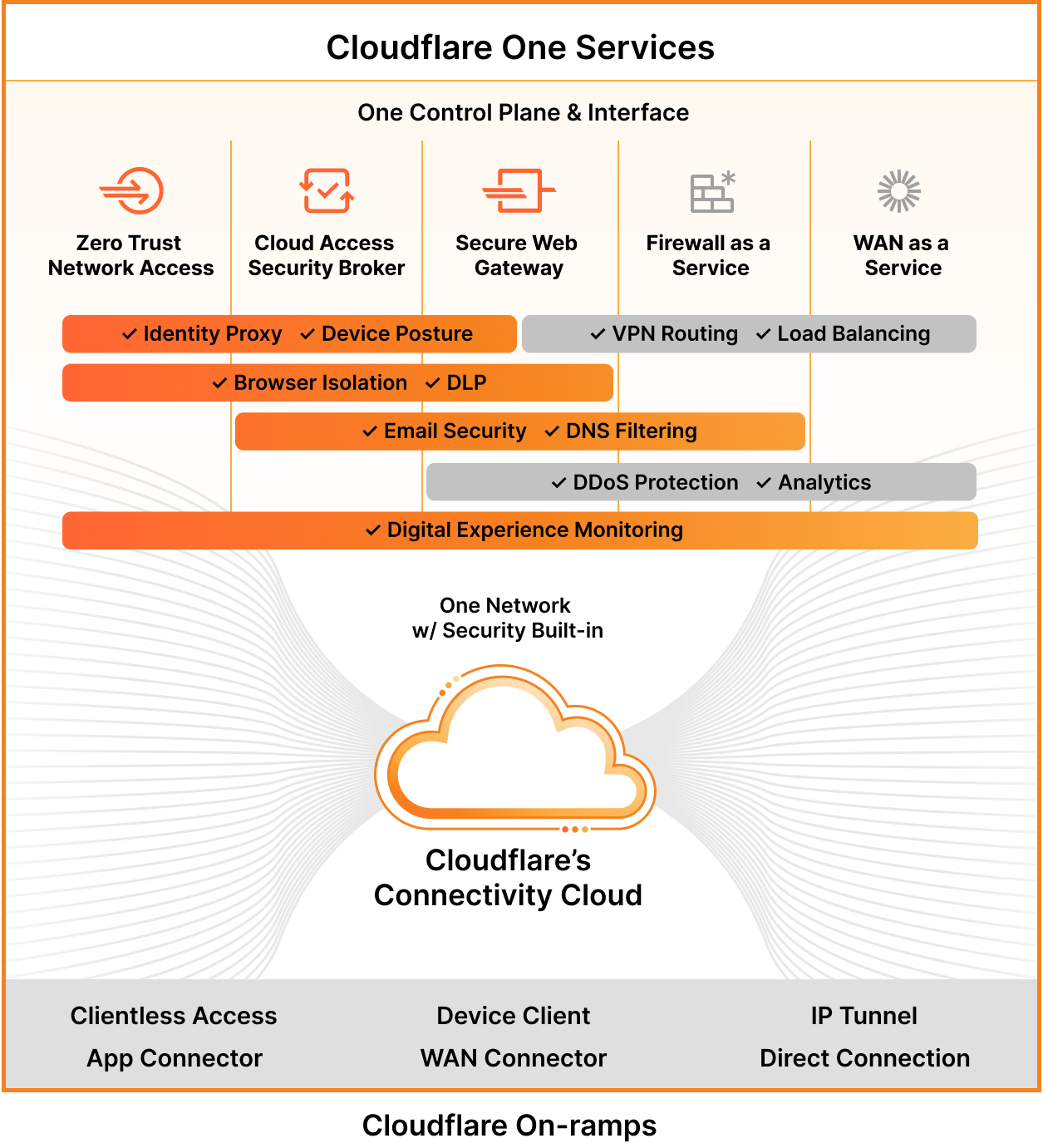

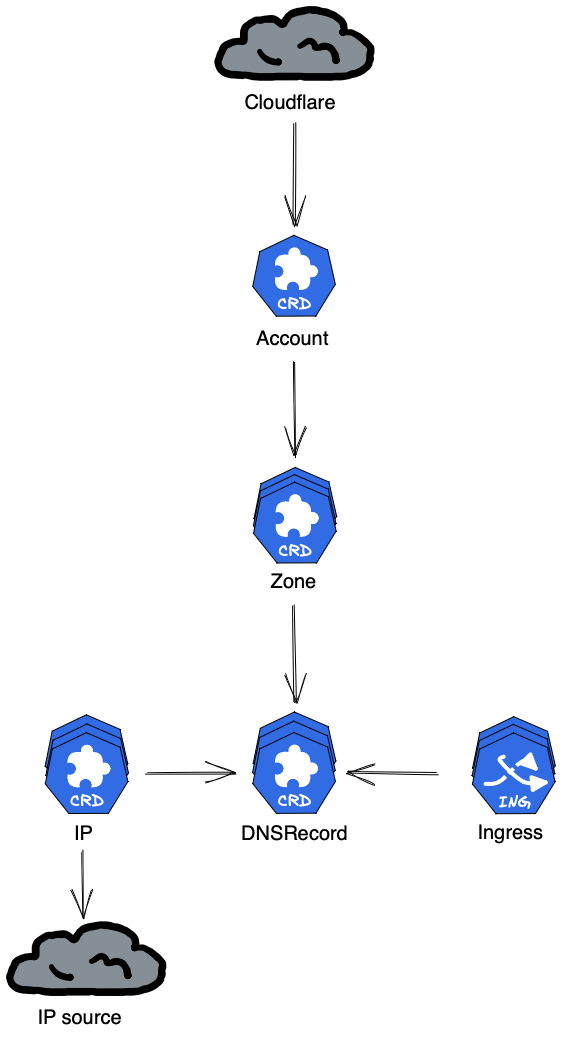

The dispute centers on Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 DNS resolver service—one of the world's fastest and most privacy-focused public DNS services. AGCOM ordered Cloudflare to block access to pirate sites by filtering DNS requests and IP routing at a global level. Cloudflare refused, arguing the order would degrade service quality for legitimate users and set a dangerous precedent for internet censorship. The company's co-founder and CEO Matthew Prince responded with an extraordinary statement, threatening to pull all servers from Italian cities, discontinue free services for Italian users, and withdraw from sponsoring the upcoming Milano-Cortina Olympics.

This isn't just a corporate dispute. It's a flashpoint in a much larger debate about who controls the internet, how content moderation happens at scale, and whether European media companies should have the power to reshape global internet infrastructure in their favor. The Piracy Shield law, adopted in 2024, represents the most aggressive automated content-blocking regime in the world. And Italy has just become the testing ground for what happens when tech companies push back.

In this deep dive, we'll explore what Piracy Shield actually does, why Cloudflare's technical arguments matter, how many legitimate sites are being caught in the crossfire, what this means for internet governance, and why this battle could reshape how the entire tech industry operates in Europe.

TL; DR

- Italy fined Cloudflare €14.2 million for not blocking pirate sites through its 1.1.1.1 DNS resolver, applying its controversial Piracy Shield law

- Piracy Shield requires blocking within 30 minutes with no judicial oversight, no due process, and no appeals—a framework even the EU has flagged as concerning

- Legitimate websites are collateral damage: Research found hundreds of legitimate sites unknowingly affected, and Google Drive was accidentally blocked for three hours

- Cloudflare threatens major retaliation: Removing all Italian servers, discontinuing free services, pulling Olympic sponsorship, and abandoning plans for an Italian office

- This sets a global precedent: If Italy's automated blocking system succeeds, other countries will likely adopt similar frameworks, fragmenting the internet

Estimated data shows that while Piracy Shield primarily targets pirate services, about 30% of affected services are legitimate, highlighting the issue of overblocking.

Understanding Italy's Piracy Shield Law: How It Works

Piracy Shield sounds technical, but its purpose is refreshingly straightforward: stop people from streaming sports without paying. Italian soccer leagues, tennis tournaments, and other major sports broadcasters lose billions annually to unlicensed streaming. In 2024, Italy decided the solution was to give rights holders the ability to shut down piracy in near-real-time.

Here's how the system actually operates in practice. A copyright holder or authorized representative identifies a pirate streaming site or domain name and submits it to AGCOM's automated platform. Within 30 minutes, ISPs across Italy must implement a DNS block at the resolver level. If a user tries to visit the site, their request gets intercepted before it even reaches the internet's nameservers. Simultaneously, ISPs must block the associated IP addresses at the routing level, preventing direct access even if someone bypasses DNS by using an IP address directly.

The speed is intentional. Live sports broadcast piracy happens in real-time—a major soccer match generates thousands of unauthorized streams simultaneously. By the time traditional legal processes work through courts, the event is over and the economic damage is done. Piracy Shield's 30-minute mandate means that rights holders can theoretically neutralize illegal broadcast feeds before most people even know they exist.

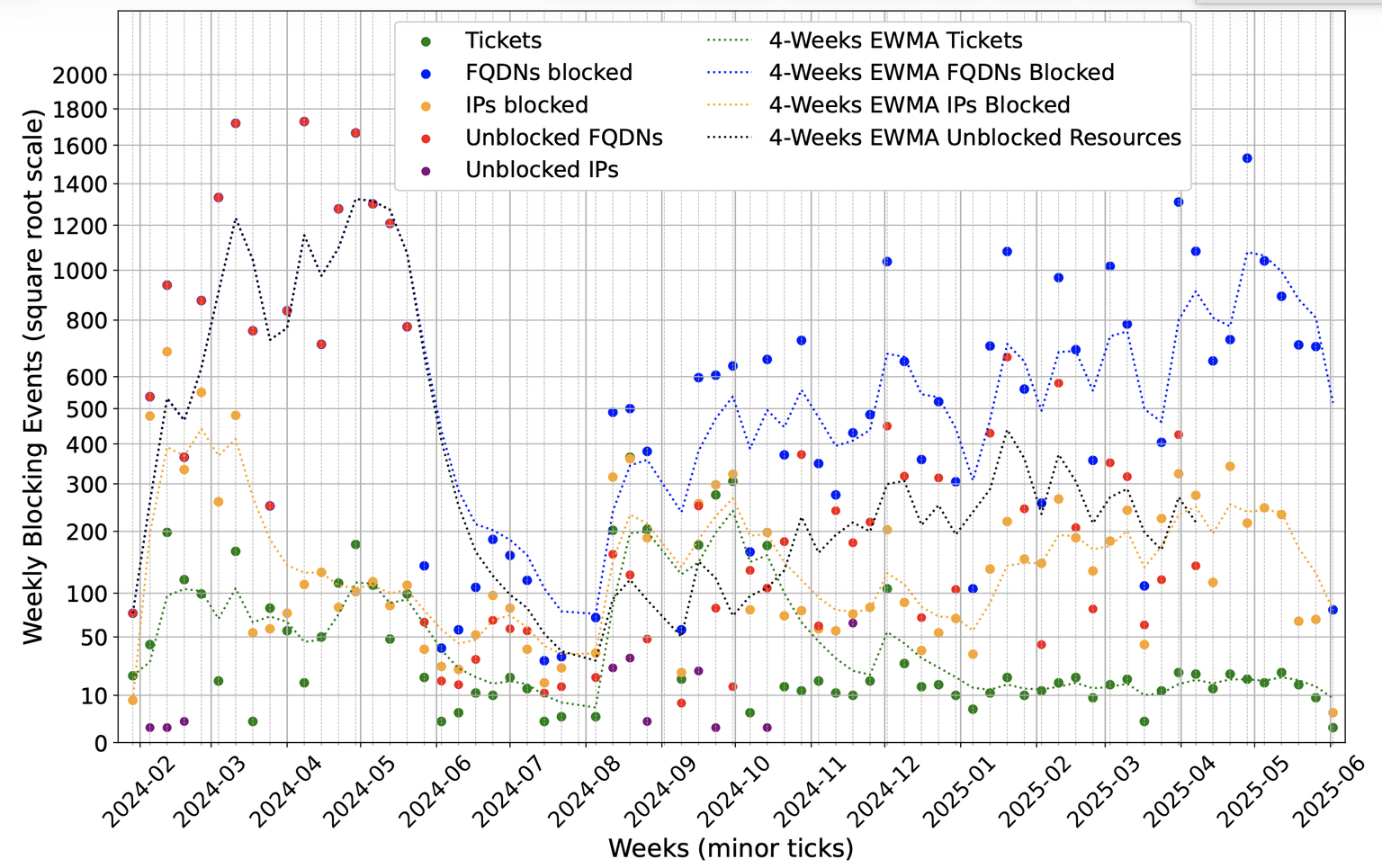

AGCOM claims this system has disabled over 65,000 domain names and about 14,000 IP addresses in its first two years of operation. On paper, that's an impressive enforcement record. But the speed and automation come with a brutal tradeoff: there's no time for human review, no mechanism to verify that the blocked domain actually facilitates piracy, and no appeal process if a legitimate business gets mistakenly blocked.

The law provides for fines up to 2 percent of a company's annual turnover. AGCOM applied a fine equal to 1 percent of Cloudflare's revenue—suggesting the agency was showing relative restraint, even though it clearly views the company's non-compliance as a serious violation.

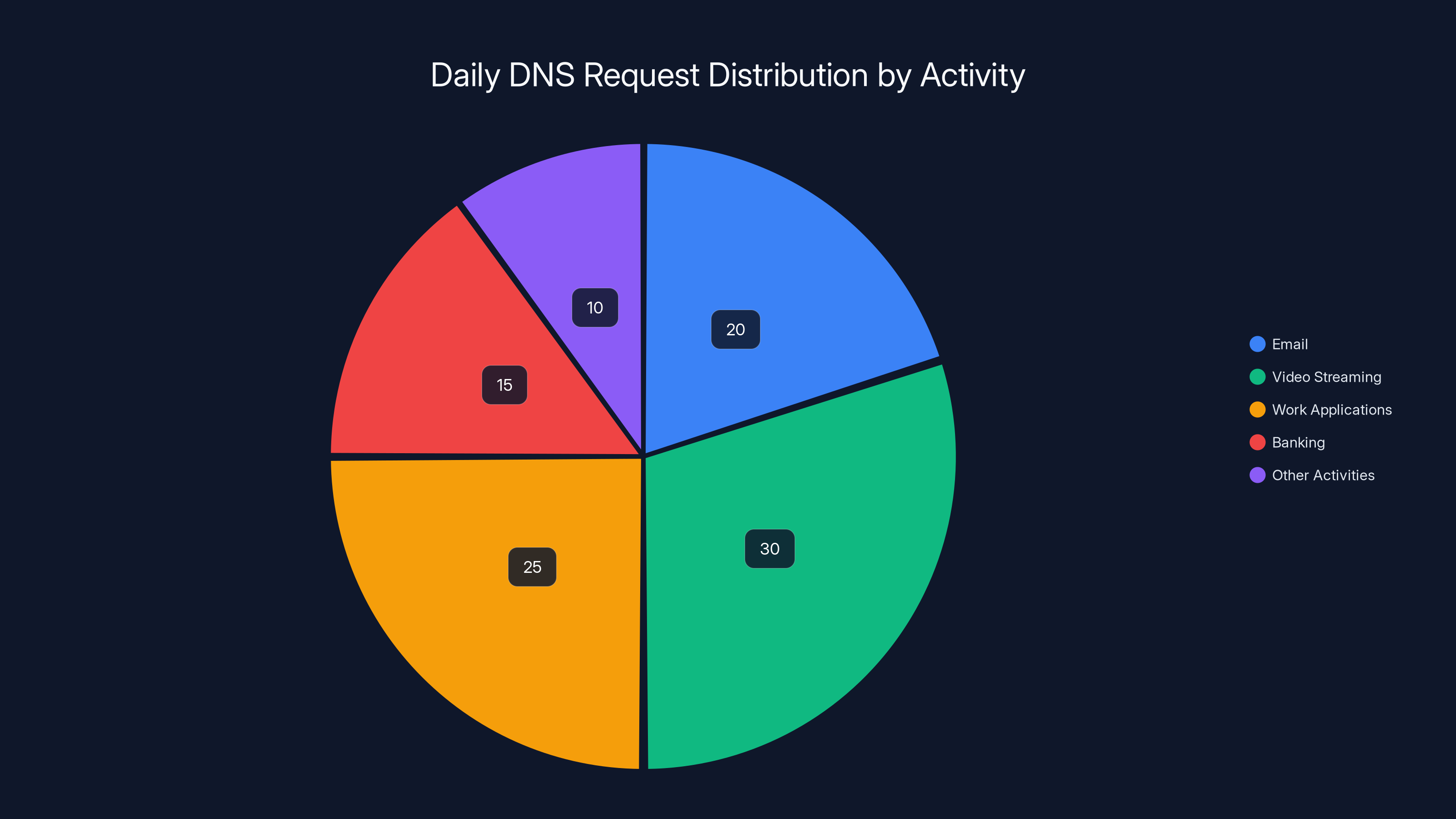

Estimated data shows video streaming and work applications account for the majority of Cloudflare's DNS requests, highlighting the potential widespread impact of DNS filtering.

The Technical Reality: Why Cloudflare's Resistance Matters

Cloudflare's refusal wasn't stubbornness or corporate arrogance. It was rooted in a legitimate technical reality: implementing Piracy Shield's requirements at the DNS resolver level would break things for innocent users.

Let's break down the scale involved. Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 DNS resolver handles approximately 200 billion DNS requests per day. That's roughly 2.3 million requests per second. These requests don't come from pirates—they come from millions of people checking email, watching YouTube, working on spreadsheets, banking online, and doing countless other normal internet activities.

When you set up a DNS filter, you're essentially creating a lookup table that says, "If someone asks for domain X, don't give them the real answer." With 200 billion daily requests, implementing and maintaining such filters in real-time introduces measurable latency. DNS is supposed to be fast—typically under 50 milliseconds. Adding filter lookups, comparisons, and decision-making to that process adds overhead. Cloudflare argued this would noticeably degrade performance for everyone, including people trying to access completely legitimate websites.

There's another problem: collateral damage. Pirate streaming sites often operate from compromised or hijacked servers. Sometimes, a single IP address hosts both a pirate site and legitimate services. If AGCOM orders the blocking of that IP address, the legitimate services go down too. Cloudflare cited this exact risk in its defense.

But here's where the story gets really complicated. AGCOM dismissed Cloudflare's technical concerns, arguing that "the targeted IP addresses were all uniquely intended for copyright infringement" and that no legitimate websites would be harmed. The agency's confidence seemed unshakeable. And then independent researchers checked AGCOM's work.

The Evidence of Overblocking: Real Harm to Legitimate Users

In September 2025, researchers published findings that contradicted AGCOM's confidence. The study examined Piracy Shield's actual performance and found something deeply troubling: the system was causing significant collateral damage.

The researchers documented "hundreds of legitimate websites unknowingly affected by blocking, unknown operators experiencing service disruption, and illegal streamers continuing to evade enforcement by exploiting the abundance of address space online." They described their findings as "a conservative lower-bound estimate," meaning the actual problem was likely worse than what they could measure.

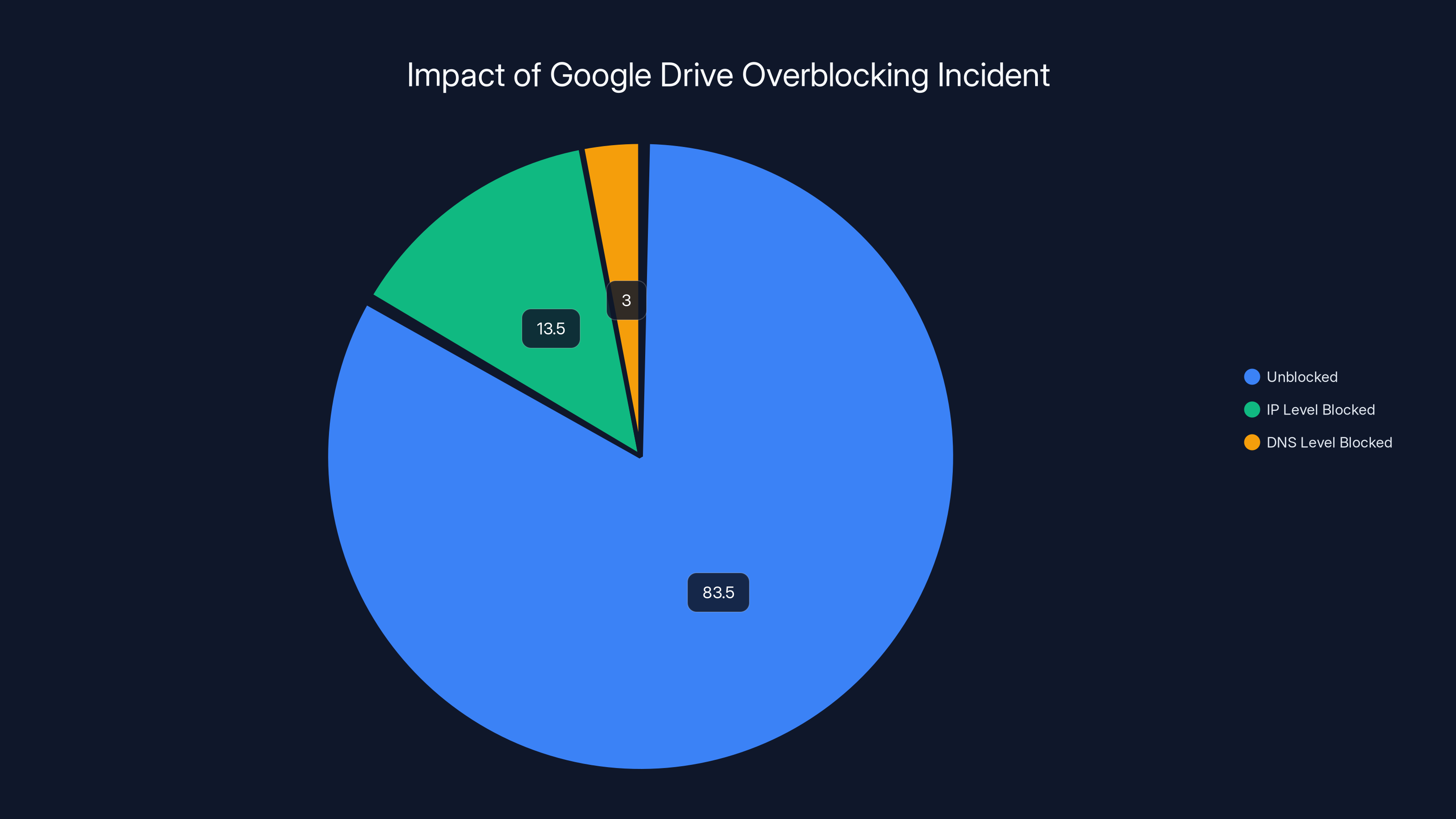

The most striking example came from Google. In October 2024, someone submitted Google Drive to the Piracy Shield blocking system, presumably by mistake. The system automatically accepted it and began blocking. For three hours, all Italian users lost access to Google Drive—one of the world's most widely used cloud storage services. Even after the block was lifted, 13.5 percent of users were still blocked at the IP level, and 3 percent remained blocked at the DNS level after 12 hours.

This wasn't a minor edge case. Google Drive is used by students, small businesses, journalists, and millions of ordinary people. The three-hour outage had real consequences: people couldn't access critical documents, couldn't collaborate on projects, couldn't submit assignments or complete work.

What's remarkable is that there's no clear mechanism for preventing this in the future. Piracy Shield requires submission, verification, and blocking—all within 30 minutes. There's no time for human review of whether a submission is actually a pirate resource. The system relies on the premise that rights holders won't abuse the power, which is optimistic at best.

A separate incident highlighted another risk. Researchers found that IP addresses blocked by Piracy Shield were becoming "unusable and polluted address ranges" that legitimate ISPs couldn't reuse for new services. Once an IP address gets flagged and blocked, even if it later hosts a legitimate service, the block often remains in place.

During the Google Drive overblocking incident, 13.5% of users remained blocked at the IP level and 3% at the DNS level even after the initial block was lifted. Estimated data based on reported figures.

DNS Resolvers: What They Are and Why They Matter

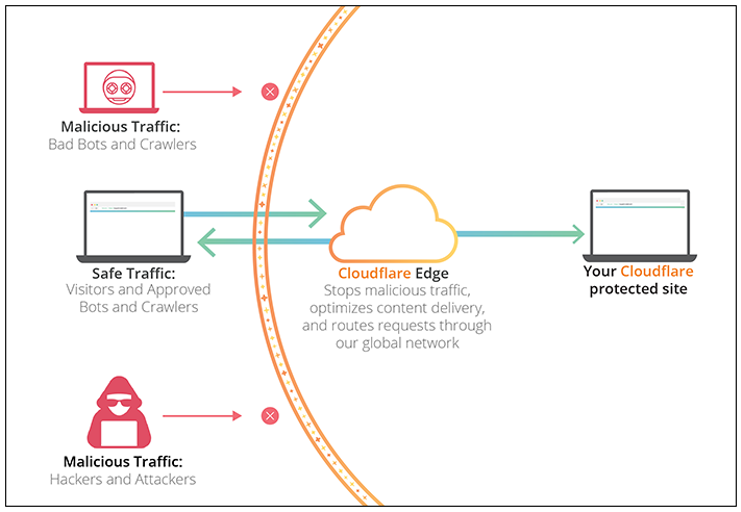

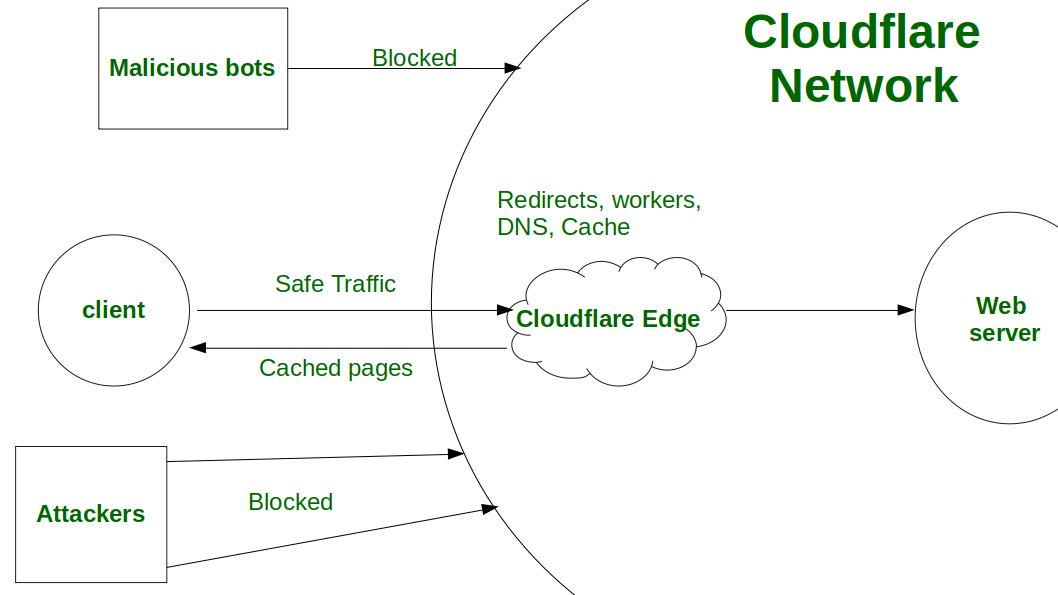

To understand why AGCOM's order to Cloudflare is so significant, you need to understand what a DNS resolver does and why it's different from other internet infrastructure.

Domain Name System (DNS) is essentially the phonebook of the internet. When you type a domain name into your browser—like runable.com or google.com—your device needs to convert that human-readable name into a numerical IP address. DNS resolvers handle that translation. They're the middlemen between users and the internet's actual address system.

There are several types of DNS resolvers. Your ISP provides one automatically. Google operates 8.8.8.8, a popular free resolver. Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 is one of the fastest and most privacy-focused options available. These public resolvers are used by hundreds of millions of people worldwide, not just in Italy.

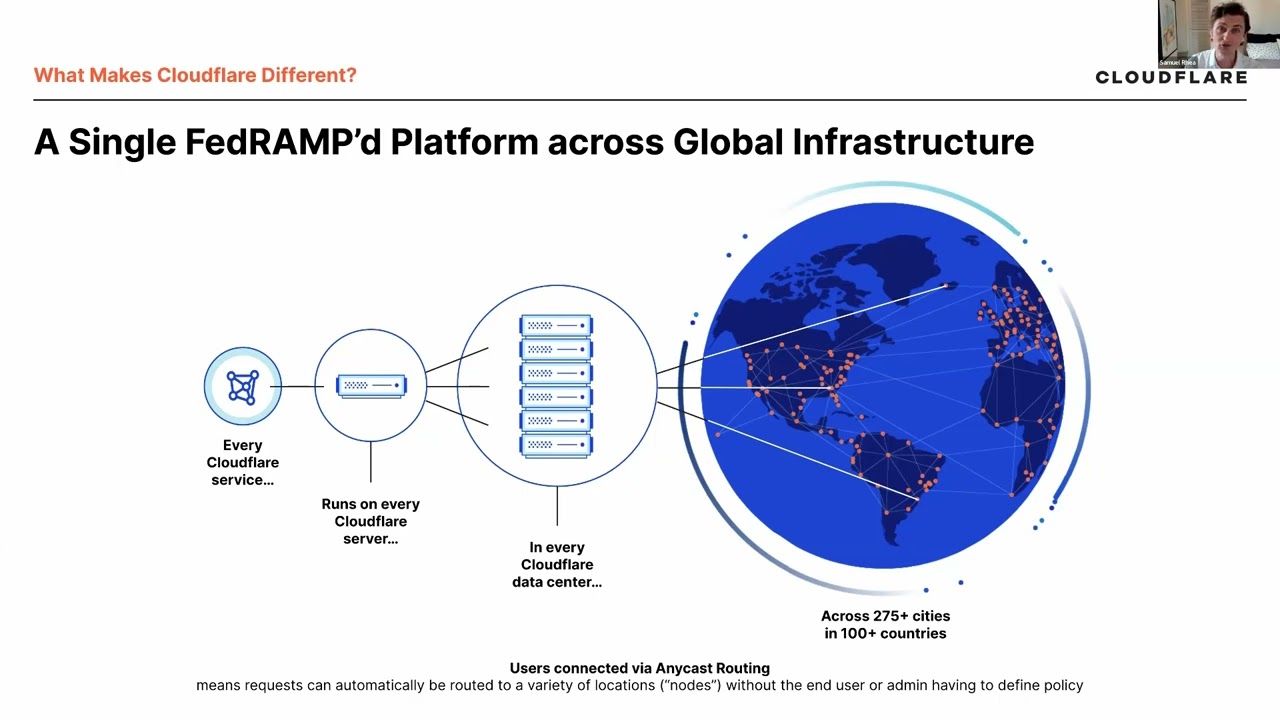

When AGCOM ordered Cloudflare to block pirate sites at the DNS resolver level, it was asking for something unprecedented: content moderation at a global chokepoint. Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 resolver serves users worldwide, not just in Italy. If Cloudflare implemented Italy's blocking orders at the resolver level, it would mean anyone using 1.1.1.1 from anywhere on Earth would be unable to access domains that Italy deemed illegal—even if those domains were legal in their own country.

This is why the concept of "local blocking" is so problematic. DNS doesn't inherently know where a user is located. A request could come from Italy, Germany, Brazil, or anywhere else. To implement geo-specific blocking at the DNS level, you'd need to identify the user's location (which requires additional infrastructure and privacy concerns), determine which blocking rules apply to their jurisdiction, and then apply those rules. It's technically possible but creates enormous complications.

Cloudflare's position is that if Italy wants content blocked within its borders, it should order ISPs operating in Italy to implement the blocks. That's how it traditionally works. ISPs have infrastructure inside Italy and can easily identify whether a user is in Italy or not. They can block content for Italian users while allowing it elsewhere. But AGCOM wanted Cloudflare to do the filtering instead—shifting the responsibility and the burden onto a global infrastructure provider.

Why Cloudflare's Threat to Leave Italy Is More Than Bluster

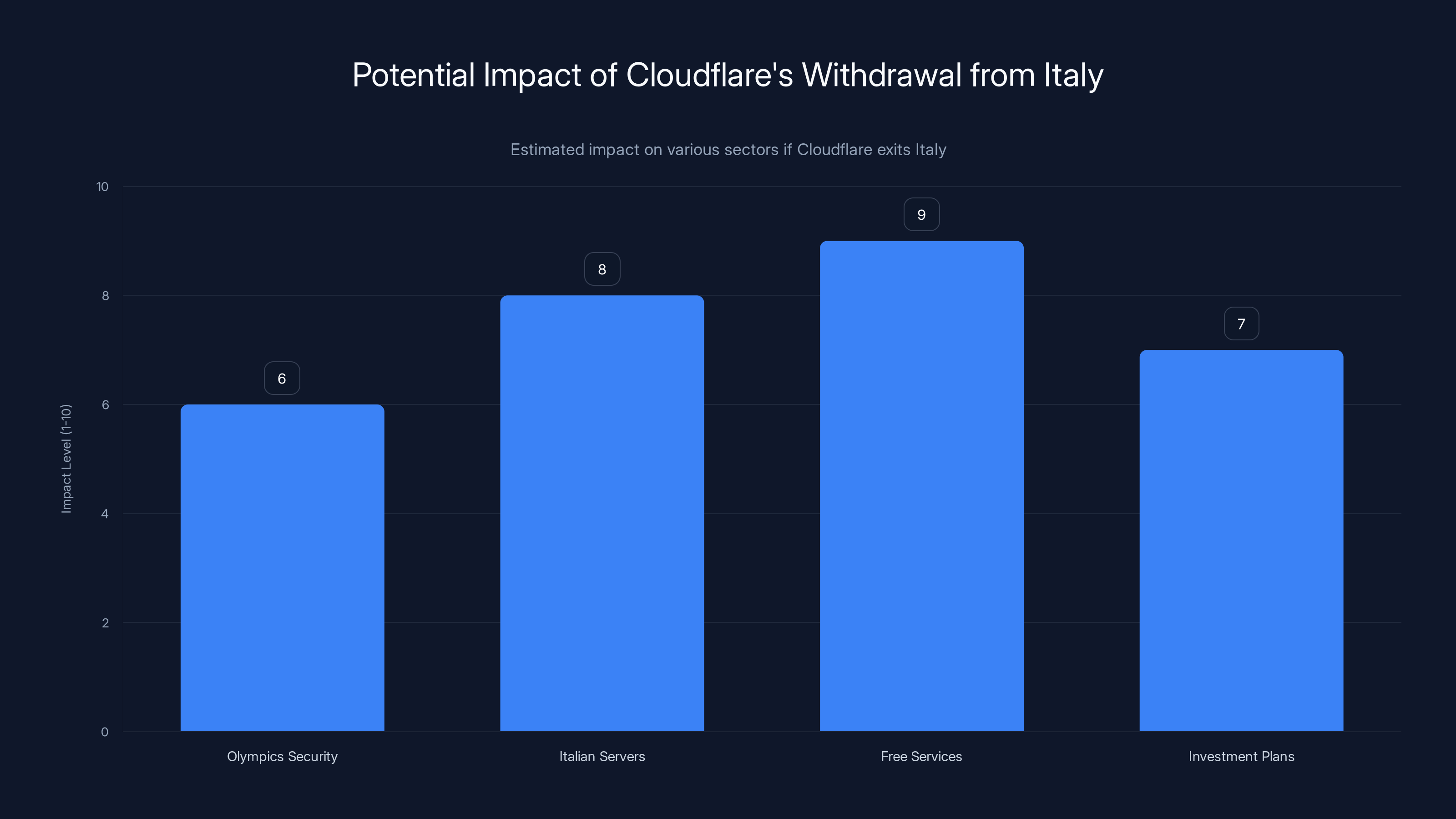

Mathew Prince's statement about potentially withdrawing from Italy wasn't idle posturing. Cloudflare outlined four specific actions it's considering: discontinuing pro bono cyber security services for the Milano-Cortina Olympics, discontinuing free services for Italian-based users, removing all servers from Italian cities, and abandoning plans to build an Italian office or make any investments in the country.

The Olympics sponsorship is the most visible. Cloudflare provides critical infrastructure for major sporting events, helping to protect them from cyber attacks and ensuring reliable broadcasts. Withdrawing that support would be disruptive but survivable for the Olympics. What's more significant is the threat to remove Italian servers and discontinue free services.

Cloudflare operates a global Content Delivery Network (CDN) and DDo S protection service. It has data centers in major cities worldwide, including Italy. These servers exist to reduce latency for users in that region—when someone in Italy accesses a Cloudflare-protected website, the request is handled by a server physically located in Italy, resulting in faster response times. If Cloudflare removes these servers, it means Italian users would be served from data centers in neighboring countries like France or Switzerland, resulting in measurable latency increases for Italian internet users.

More significantly, Cloudflare's free tier attracts millions of small businesses, student projects, and nonprofits that can't afford premium services. Discontinuing free service for Italian users would force these organizations to migrate to competitors, pay for premium tiers, or shut down. It's a credible threat because Cloudflare has actually done it before in limited circumstances when facing untenable regulatory situations.

Prince's statement suggests he's willing to escalate this into a major geopolitical issue. The mention of discussing the matter with US government officials next week indicates Cloudflare is considering framing this as a trade and technology policy matter, not just a corporate compliance dispute. The company might argue that Italy's Piracy Shield law creates an unfair burden on US-based companies and ask the US government to raise the issue through diplomatic channels.

For Italy, losing Cloudflare's infrastructure would be costly. It would slow down Italian internet access, harm Italian businesses that rely on Cloudflare's services, and potentially invite similar regulatory pressure on other US tech companies to withdraw. This creates a game of chicken where both sides face real consequences if neither backs down.

Estimated data shows that compliance infrastructure and precedent costs are the highest potential financial impacts for Cloudflare, while Italian users face significant service degradation risks.

The Broader Context: Europe's War on Piracy and Tech Freedom

Piracy Shield didn't emerge in a vacuum. It's part of a decades-long battle between European media companies and internet technology providers over how content should be protected online.

Europe has been aggressive about content liability for years. The EU's Copyright Directive (adopted in 2019) requires platforms to take responsibility for user-uploaded content, pushing companies like YouTube and TikTok to implement expensive content filtering systems. The Digital Services Act (effective in 2024) imposes requirements on platforms to police content and be transparent about their moderation practices. These represent a broader European philosophy that platforms should be responsible for what happens on their services.

But Piracy Shield takes this much further. It's not asking platforms to remove infringing content that users report. It's asking DNS providers and ISPs to preemptively block access to websites based on accusations from copyright holders, with minimal verification and no meaningful appeal process.

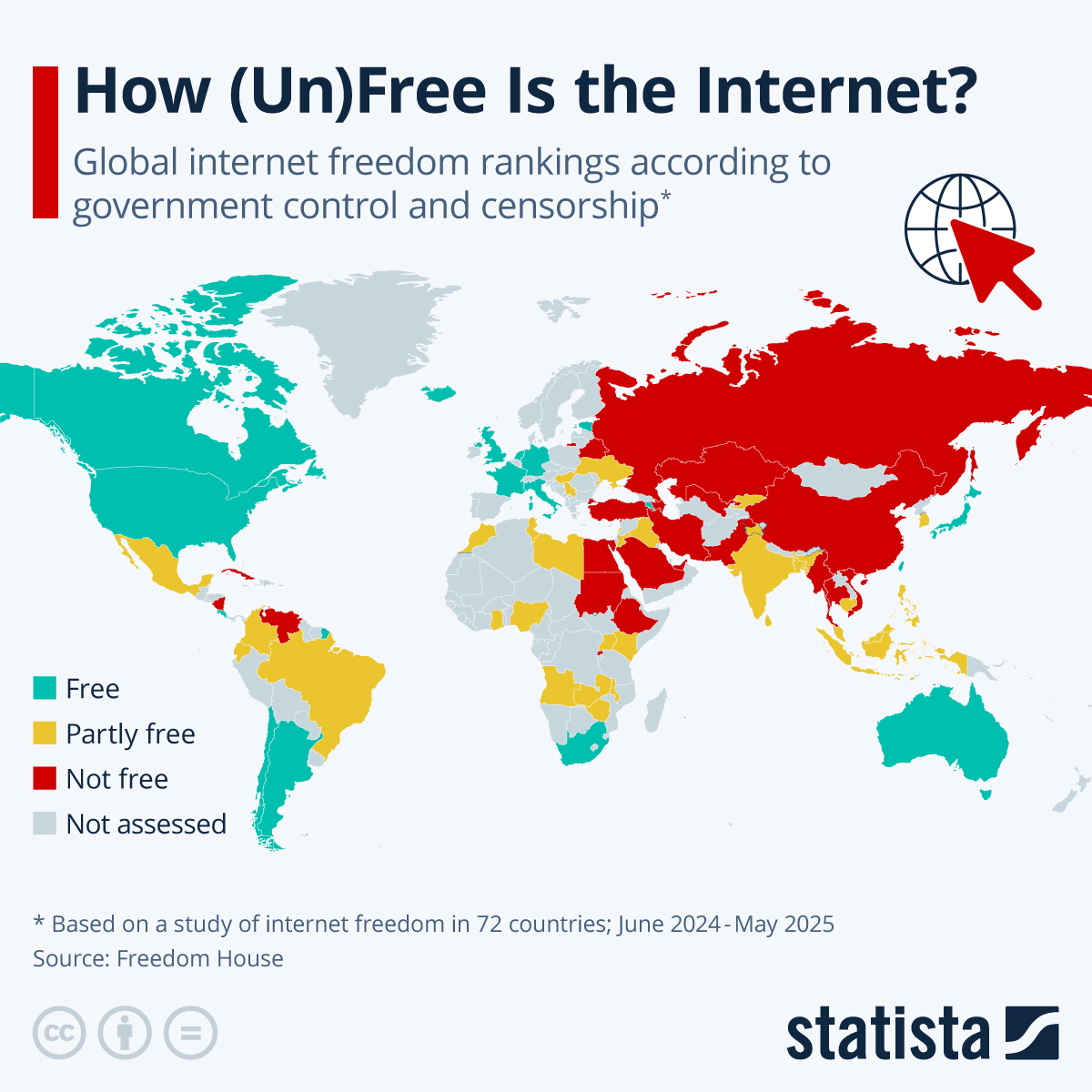

This approach has consequences beyond Italy. If it succeeds, other countries will adopt similar frameworks. China blocks DNS requests for websites it deems problematic. Russia and Iran do the same. But they're authoritarian regimes. What concerns tech companies and internet advocates is that a democratic EU country is implementing infrastructure-level blocking that rivals authoritarian approaches, just with different targets (pirate sites rather than political speech).

The Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA), which represents tech companies including Google and Cloudflare, filed a formal letter to European Commission officials criticizing Piracy Shield. The organization noted that the law "raises a significant number of concerns which can inadvertently affect legitimate online services, primarily due to the potential for overblocking." They specifically mentioned that the verification procedures between submission and blocking "are not clear, and indeed seem to be lacking."

This regulatory risk isn't unique to Cloudflare. Google has also been ordered to block pirate sites at the DNS level. The difference is that Google has more political capital and more resources to fight back. Cloudflare, as a smaller company that's primarily known to tech professionals rather than the general public, is in a weaker position to resist.

The Legal Questions: Due Process and Administrative Law

Cloudflare's strongest arguments against the fine relate to due process and administrative law principles. The company isn't arguing it shouldn't follow the law; it's arguing the law itself violates fundamental legal principles.

First, there's the issue of appeal. Piracy Shield allows no meaningful appeal of blocking orders before they take effect. A rights holder submits a domain or IP address, and within 30 minutes, ISPs must implement the block. If someone believes the block was improper, they can challenge it later—but by then, the damage is done. For a live sports event, 30 minutes is the difference between stopping piracy and watching it happen in real-time.

Compare this to traditional copyright enforcement, where a rights holder files a lawsuit, a judge issues an injunction, and then the defendant can appeal. The process takes time, but it includes multiple opportunities for error correction. Piracy Shield compresses this to 30 minutes with no judicial involvement.

Second, there's the lack of transparency. AGCOM never clearly specified which domains or IP addresses it wanted blocked or why. The blocking happens automatically based on submissions by unknown operators. Rights holders aren't required to publish what they've submitted or provide details about their reasoning. This opacity makes it impossible to know whether blocks are proportional or necessary.

Third, there's the question of proportionality. A €14.2 million fine on a company's annual revenue is substantial. But what's the legal basis for this specific amount? AGCOM says it applied 1 percent of Cloudflare's annual turnover, but it's unclear how it determined that Cloudflare's non-compliance warranted any fine at all, let alone such a large one. In traditional regulatory contexts, penalties should be proportional to the severity of the violation. Here, the violation is refusing to implement what Cloudflare argues is an illegal order.

Cloudflare's position is legally interesting because the company isn't saying it won't block pirate sites in general. Cloudflare already removes customers who use its services for piracy. The company also has policies preventing DNS hijacking and other malicious uses. The disagreement is specifically about whether Cloudflare should implement automated, infrastructure-level blocking at the resolver level based on submissions from private rights holders with minimal verification.

European administrative law has traditionally required due process in regulatory enforcement. AGCOM's approach seems to sidestep this by automating enforcement and removing human judgment from the process. A court might eventually agree with Cloudflare that Piracy Shield's procedures violate fundamental principles of administrative law, even if the underlying goal (stopping piracy) is legitimate.

Cloudflare's potential withdrawal from Italy could have significant impacts, particularly on free services and server availability, with estimated high impact levels of 8 and 9 respectively. Estimated data.

How Other Tech Companies Are Responding

Cloudflare isn't the only company resisting Italy's piracy enforcement regime, but it's the most vocal. Google has also received blocking orders and has been more quietly resistant, using legal channels rather than public statements to challenge the requirements.

What's interesting is the strategic difference. Cloudflare's Matthew Prince chose to make this a public fight, calling out Italy's approach as "unjust" and characterizing the system as controlled by "a shadowy cabal of European media elites." This rhetorical approach is designed to mobilize public opinion and political pressure. By framing this as a free speech issue and inviting US government involvement, Prince is trying to shift the conflict from a regulatory dispute to a geopolitical one.

Google's approach is more cautious. The company has presumably filed legal challenges and engaged in quiet negotiations with AGCOM, but hasn't made dramatic public threats. This reflects Google's different position—the company has more to lose in Europe (more users, more business, more regulatory exposure) but also more negotiating power (it's larger, more politically important, and harder for Italy to fully exclude).

Other DNS providers and CDN operators are watching closely. If Cloudflare loses and is forced to comply with Piracy Shield, it creates a precedent that other countries will copy. Every major tech company will then face similar orders from every jurisdiction. The alternative—refusing and facing massive fines—becomes untenable as a business strategy if multiple countries adopt the model.

This creates a coordination problem. If companies resist alone, they lose. But if they resist together through industry groups like CCIA, they have more political power. That's likely why CCIA filed its formal complaint to European Commission officials. The trade group is trying to get EU-level authorities to rein in Italy's most aggressive interpretations before other countries adopt similar frameworks.

Meanwhile, startups and smaller tech companies are potentially most vulnerable. They lack Cloudflare's resources to fight regulatory battles and Cloudflare's ability to threaten to withdraw major services. A small startup providing DNS services might simply have to comply with Piracy Shield or exit the Italian market entirely.

The Role of Automated Enforcement and AI

One overlooked aspect of Piracy Shield is that it's fundamentally an automated enforcement system. Humans aren't making individual blocking decisions; an automated platform accepts submissions and implements them. This reflects a broader trend in internet governance: replacing human judgment with algorithmic enforcement.

Automated systems have advantages: they're faster, cheaper, and more consistent. For blocking pirate sites with a 30-minute deadline, automation is the only way to achieve that speed. But automation also creates the overblocking problem. An automated system can't exercise judgment about whether a submission is legitimate, whether a domain actually facilitates piracy, or whether the blocking might harm innocent users.

This gets into deeper questions about the role of AI and automation in regulation. Modern regulatory systems are increasingly moving toward automated enforcement: automated content moderation on platforms, automated tax collection systems, automated driving behavior enforcement through camera networks. Each system trades human judgment for speed and scale.

The problem is that humans are actually pretty good at distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate uses. A human reviewer might recognize that Google Drive shouldn't be blocked even if someone submitted it. But an automated system will implement whatever rule it's given unless explicitly programmed to recognize exceptions. As these systems become more prevalent, the question of who bears responsibility when they fail becomes increasingly important.

Cloudflare's refusal to implement Piracy Shield is, in some sense, a refusal to become a cog in someone else's automated enforcement machine. By implementing the blocks, Cloudflare would be using its infrastructure to enforce Italy's rules globally. By refusing, the company is asserting that internet infrastructure providers shouldn't be responsible for enforcing every jurisdiction's content policies.

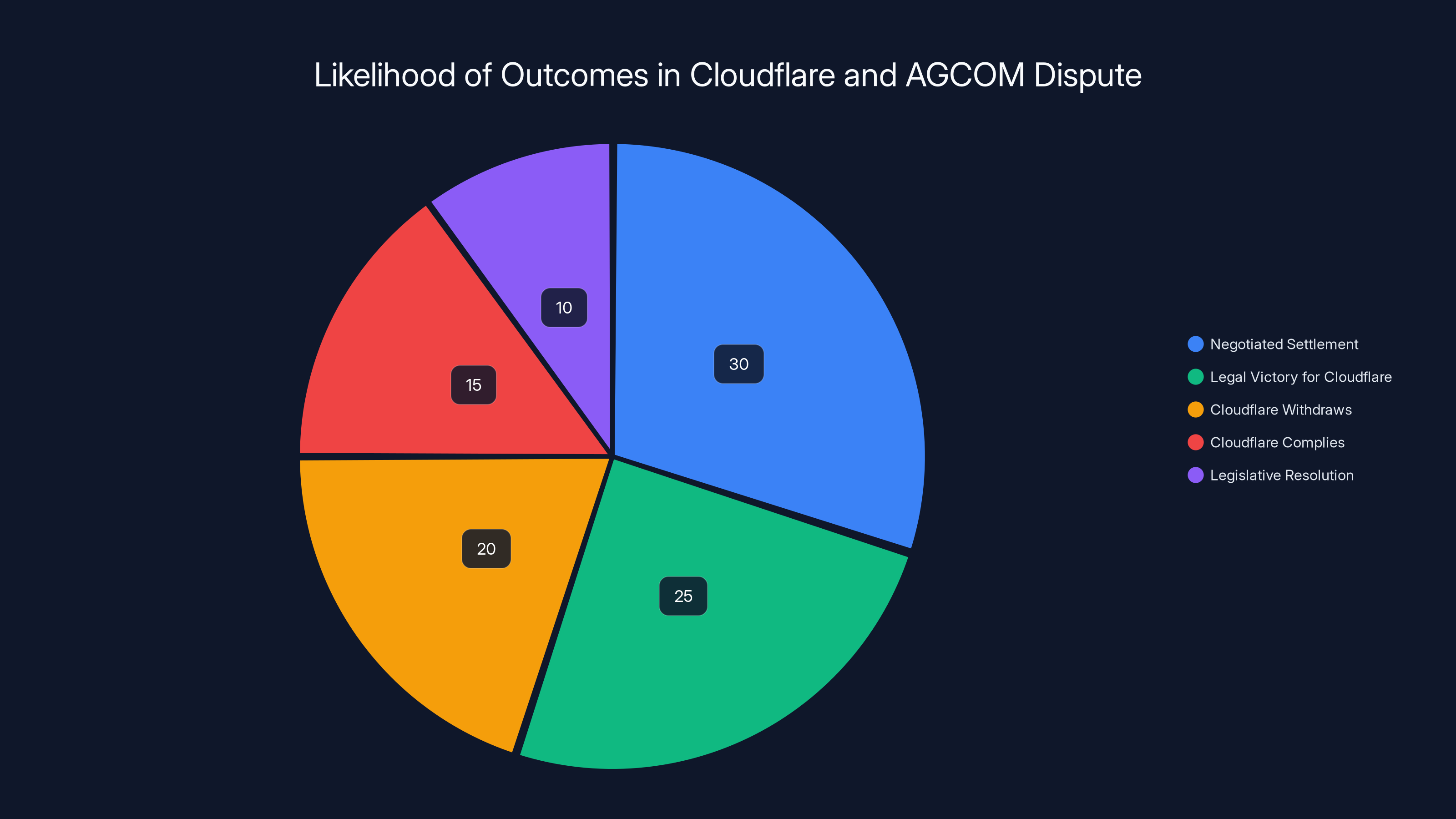

The most likely outcome is a negotiated settlement at 30%, followed by a legal victory for Cloudflare at 25%. Estimated data based on narrative analysis.

International Internet Governance and Jurisdiction

At its heart, the Cloudflare dispute reveals a fundamental tension in internet governance: the internet is global, but laws are national.

Cloudflare operates globally. Its 1.1.1.1 resolver serves users in every country. When Italy orders Cloudflare to implement blocking, Italy is essentially asserting the right to control what the entire internet shows to Italian users. That's a reasonable assertion—countries naturally want to enforce their laws within their borders. The problem comes when enforcing Italian law requires disrupting the global infrastructure itself.

In traditional telecommunications, this wasn't a problem. If Italy wanted to block a phone call, it could order Italian phone companies to block calls originating from a specific number. The technology made it easy to implement rules at borders. But the internet infrastructure is more global. DNS resolvers, CDNs, and cloud providers operate at a planetary scale. When they implement blocking, they're choosing between making it global or implementing complex geo-specific filtering.

This has created a fragmentation risk that internet advocates worry about constantly. If Italy can compel Cloudflare to block content, so can China, Russia, Iran, and every other country. Each jurisdiction imposes its own blocking requirements. Eventually, you end up with a globally fragmented DNS system where different countries see different versions of the internet.

Some technologists call this the "Balkanization" of the internet. It would be more efficient for everyone (technically and economically) if there were one global internet. But politically and culturally, countries naturally want to enforce their values within their borders. The tension between these two forces is the defining conflict in internet governance.

Cloudflare's position is that countries should enforce their laws through national ISPs, not global infrastructure providers. If Italy wants to block a domain for its citizens, Italian ISPs should do the blocking. This preserves the global internet while respecting national sovereignty. AGCOM's position seems to be that global providers like Cloudflare should implement blocking globally because they have the technical capability to do so.

The precedent set here will matter enormously. If Cloudflare is forced to implement Piracy Shield, it signals that global infrastructure providers can be compelled to enforce any country's laws globally. That's a much more fragmented and controlled internet than what currently exists.

Economic Impacts: Costs to Cloudflare and Italian Users

The financial implications of this dispute extend beyond the €14.2 million fine itself.

First, there's the direct cost of compliance. If Cloudflare implements Piracy Shield, it needs to maintain databases of blocked domains and IP addresses, query these databases on every DNS request, and manage the infrastructure overhead. For a company handling 200 billion daily DNS requests, adding just a few milliseconds of latency per query could require significant infrastructure investment. Cloudflare would need to deploy new filtering infrastructure in multiple regions, increase computational capacity, and probably hire additional staff to manage the system.

Second, there's the reputational cost. Cloudflare built its brand partly on being privacy-focused and resistant to censorship. The company has historically refused to comply with blocking orders and government surveillance requests beyond what the law strictly requires. If Cloudflare implements Piracy Shield, it contradicts this positioning. The company might lose customers who chose it specifically because of its resistance to censorship.

Third, there's the precedent cost. Every other jurisdiction will assume that Cloudflare will comply with its own blocking requirements. Spain will order blocks, France will order blocks, Germany will order blocks. Cloudflare will be drawn into implementing hundreds of different national blocking regimes, each with its own format, its own oversight level, and its own political implications.

From Italy's perspective, Cloudflare's resistance is costly too. If the company follows through on threats to withdraw infrastructure, Italian internet users will experience degraded performance for services protected by Cloudflare's CDN. Italian businesses that rely on Cloudflare's DDo S protection will be forced to find alternatives. The cost of losing a major infrastructure provider is real.

There's also a game-theory element. If Cloudflare successfully resists, it shows other tech companies that fighting is possible. If Cloudflare capitulates, it shows that massive fines will eventually break resistance. The amount of the fine—€14.2 million—is calibrated to hurt but not destroy Cloudflare. It's high enough to be costly but low enough that Cloudflare might rationally just pay it and move on, rather than fighting through years of litigation.

Unfortunately for Italy, Cloudflare seems willing to fight. The company is profitable, has financial resources, and its CEO has expressed ideological commitment to internet freedom. For a startup or smaller company, a €14.2 million fine might be existential. For Cloudflare, it's significant but survivable. And if the company can win this fight, it protects its long-term interests far more than the cost of the fine.

Piracy Solutions That Don't Require DNS Blocking

One question worth asking: are there better ways to fight piracy that don't require infrastructure-level blocking?

Yes, actually. Several existing approaches could be more effective and less harmful than Piracy Shield:

Payment friction: Most pirate streaming sites succeed because they offer a better user experience than legitimate services. They're easier to find, don't require subscriptions, and work from any device. If legitimate services became more convenient and affordable, piracy would decline naturally. Evidence suggests that when legitimate options are accessible, most people prefer them. The success of Netflix and Disney+ in reducing piracy demonstrates this.

Source tracing: Rather than blocking sites, rights holders could work backward to identify the sources of pirated content and prosecute the operators. Pirate streaming services typically require significant infrastructure and skilled operators. Remove the operators, and you remove the service. This requires more investigative work than automated blocking, but it addresses the root cause.

Financial choke points: Payment processors and advertisers are vulnerable points in the piracy ecosystem. Pirate sites need payment processors to charge subscription fees and advertisers to monetize traffic. Pressure on payment processors and ad networks to refuse service to known pirate sites is less infrastructure-intensive than DNS blocking and more targeted.

Content obfuscation: Rights holders could use digital rights management (DRM) technology to make content harder to capture and redistribute. Modern DRM is more sophisticated than it was a decade ago and could reduce the volume of available pirated content.

Transparency and accountability: For Piracy Shield specifically, adding verification procedures, transparency requirements, and meaningful appeal mechanisms would address many of the criticisms without eliminating the system entirely. Requiring human review before blocking, publishing lists of blocked domains, and allowing challenges could preserve piracy enforcement while protecting legitimate services.

What's notable is that Italy chose the most aggressive, least reversible approach rather than trying the less harmful options first. That's a common regulatory pattern, but it's also a risky one. Once you've built an automated blocking infrastructure and users have adapted to it, it's hard to reverse course even when better alternatives emerge.

What Happens Next: Likely Scenarios

This dispute won't be resolved quickly. Here are the most probable outcomes:

Scenario 1: Negotiated Settlement: Cloudflare and AGCOM reach a compromise where Cloudflare implements some but not all blocking requirements, or implements them only in ways that minimize service degradation. This requires both sides to declare partial victory and move on. Likelihood: 30 percent.

Scenario 2: Legal Victory for Cloudflare: An Italian court or European Union court rules that Piracy Shield's procedures violate administrative law principles or exceed regulatory authority. Cloudflare wins the case and is refunded or the fine is overturned. Likelihood: 25 percent.

Scenario 3: Cloudflare Withdraws: Cloudflare follows through on its threats, removing servers from Italy and discontinuing free services. The company becomes a symbol of resistance to overregulation, attracting customers who value its principles. Italy retaliates by imposing additional fines, but can't force compliance from a company no longer operating in the country. This becomes a standoff. Likelihood: 20 percent.

Scenario 4: Cloudflare Complies: After exhausting legal options, Cloudflare implements Piracy Shield, accepting the costs as a business decision. This sets precedent for other jurisdictions, leading to widespread implementation of similar blocking schemes globally. The internet becomes more fragmented by jurisdiction. Likelihood: 15 percent.

Scenario 5: Legislative Resolution: EU authorities intervene and modify either Piracy Shield or regulations on DNS providers to establish clearer rules. This requires political consensus and takes years. But it would create legal clarity for the entire industry. Likelihood: 10 percent.

Most likely is some combination of these scenarios, with the dispute stretching on for years through various legal and political channels while Cloudflare maintains non-compliance and continues threatening withdrawal.

Implications for Internet Regulation and Tech Policy

Regardless of how this specific dispute resolves, it's a signal that internet regulation is entering a new phase.

For the last two decades, tech companies have largely governed themselves. They wrote their own policies, determined their own content moderation standards, and set their own terms of service. Governments allowed this because the technology was complex and governments lacked expertise.

That's changing. Governments are becoming more sophisticated about internet technology. Regulators are more willing to assert authority over internet infrastructure. And public sentiment has shifted—there's less confidence in tech companies' ability to self-regulate and more interest in direct government supervision.

Piracy Shield represents one extreme: governments using technical infrastructure to enforce laws automatically, with minimal human judgment and limited appeal mechanisms. Other regulations, like the Digital Services Act and the Online Safety Bill, represent different approaches with different tradeoffs.

The question for tech companies is how to operate in an increasingly regulated environment while preserving the global, open internet. Some companies will choose to comply with every jurisdiction's requirements, accept the costs and complexity, and segment their services by region. Others will choose to exit certain markets rather than comply with unreasonable demands. Most will find themselves somewhere in the middle, fighting some battles and conceding others.

For users, the implication is that the global internet of the past two decades is unlikely to persist. As countries impose more different requirements, infrastructure providers will increasingly need to implement geo-specific rules. This could lead to a slower, more fragmented internet where services vary significantly by country.

The Bigger Picture: Content Control in the Modern Internet

The Cloudflare-Italy dispute is ultimately about who controls content on the internet and through what mechanisms. This is a question that will define the next decade of internet policy.

Traditionally, content control happened at two levels: the creator level (the person or organization publishing the content) and the platform level (the service hosting and distributing the content). If you published something on your blog, you controlled it. If you published something on YouTube, YouTube had some control and could moderate it. But the underlying internet infrastructure—the DNS system, the routing protocols, the data centers—was neutral. It didn't judge content or make decisions about what was legal.

What's happening now is a shift toward controlling content at the infrastructure level. Governments and organizations want DNS providers, ISPs, and CDNs to become the enforcement mechanism for content policy. This is technically possible—infrastructure providers have visibility into all traffic and could theoretically implement any filtering policy. But it's also powerful, because it means infrastructure providers become the arbiters of what the internet contains.

Cloudflare is resisting this shift. The company is essentially arguing that infrastructure providers should remain neutral and that content control should happen elsewhere (on platforms, through law enforcement, etc.). AGCOM is arguing that infrastructure providers should be active enforcers because they're the most efficient mechanism for rapid content removal.

This fundamental disagreement will persist and likely intensify. As piracy and copyright enforcement become a bigger issue (and they will, as sports leagues lose more money to unauthorized streaming), governments will create more laws like Piracy Shield. Infrastructure providers will face increasing pressure to comply. Some will, some won't. The internet will become less uniform.

The wildcard in all of this is public opinion. If enough people come to see Piracy Shield as unjust overreach, it could shift political pressure on AGCOM or the Italian government. If people come to see piracy as serious enough to warrant aggressive enforcement, it could shift pressure on Cloudflare to comply. Right now, public awareness of Piracy Shield is limited, which gives regulators room to act without political constraint.

But as more companies face similar pressures and more legitimate services get collateral-damaged by overly aggressive blocking, awareness will grow. The story of Google Drive being blocked for three hours is exactly the kind of concrete, relatable example that shifts public opinion. When ordinary people understand that internet regulation can break services they depend on, they become more interested in how those regulations work.

FAQ

What is Italy's Piracy Shield law and why was it created?

Piracy Shield is Italy's automated content-blocking system, adopted in 2024 to combat unauthorized sports streaming. The law allows rights holders to submit pirate domain names and IP addresses to a centralized platform, which automatically orders ISPs and DNS providers to block access within 30 minutes. Italy created the law because live sports piracy causes billions in losses to broadcasters—by the time traditional legal processes work through courts, the pirate streams have already run and the economic damage is done. The system aims to shut down illegal broadcasts in near-real-time.

Why did Italy fine Cloudflare €14.2 million?

Italian communications regulator AGCOM ordered Cloudflare to block pirate sites through its 1.1.1.1 DNS resolver service. Cloudflare refused, arguing it would degrade service quality for legitimate users and violate principles of due process. When Cloudflare didn't comply, AGCOM fined the company €14.2 million (about 1 percent of Cloudflare's annual revenue). This was one of the largest fines AGCOM has issued and signals the agency's commitment to enforcing Piracy Shield across all infrastructure providers, not just ISPs.

What are the technical problems with implementing Piracy Shield at the DNS resolver level?

Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 resolver handles approximately 200 billion DNS requests per day. Implementing filtering adds latency to every request, which slows down internet access for all users. Additionally, pirate services often operate on IP addresses that also host legitimate content. Blocking those IP addresses affects legitimate services, a phenomenon called overblocking. Research found that the system has already affected hundreds of legitimate websites, including a three-hour outage of Google Drive for Italian users.

What does Cloudflare do and why is this decision significant?

Cloudflare operates critical internet infrastructure including a DNS resolver service (1.1.1.1), a Content Delivery Network (CDN), and DDo S protection services. The company serves hundreds of millions of users globally. Cloudflare's refusal to comply with Piracy Shield signals that major infrastructure providers won't automatically implement every jurisdiction's content policies. If Cloudflare is forced to comply, it sets precedent for other countries to impose similar requirements, potentially fragmenting the global internet into country-specific versions.

What did Matthew Prince mean by threatening to pull servers out of Italy?

Cloudflare's CEO stated the company is considering removing all its physical servers from Italian cities, discontinuing free services for Italian users, and withdrawing from plans to build an Italian office. This would slow internet access for Italian users accessing Cloudflare-protected websites and force Italian businesses to migrate to alternative services. The threat is credible because Cloudflare has the economic resources to absorb the cost, unlike smaller companies that would be forced to comply or abandon the market entirely.

How does overblocking happen and why can't it be easily prevented?

Overblocking occurs when automated blocking systems inadvertently affect legitimate content. For example, when someone submitted Google Drive to Piracy Shield, the system automatically accepted it and blocked the service for three hours because it lacked human review mechanisms. The law requires blocking within 30 minutes, which leaves no time for verification or human judgment. Preventing overblocking would require slowing the process significantly or implementing more careful verification procedures, both of which defeat the purpose of rapid automated enforcement.

Could other countries adopt similar systems to Piracy Shield?

Yes, and this is the primary concern among tech advocates. If Piracy Shield succeeds in forcing Cloudflare to comply, it demonstrates that infrastructure providers can be compelled to implement automated content blocking. Other countries—including Spain, France, Germany, and potentially authoritarian regimes—could adopt similar frameworks, each with their own blocking requirements. This would fragment the internet into country-specific versions, making it slower, more complex, and less globally interconnected. The precedent set by Cloudflare's compliance or resistance will influence how quickly such systems spread.

What alternatives to infrastructure-level blocking exist for fighting piracy?

Several approaches could reduce piracy without requiring DNS-level blocking: improving access to affordable legitimate streaming services, which studies show reduces piracy; targeting payment processors and advertisers that enable pirate sites; tracing pirate operations back to their operators and pursuing legal action; and implementing stronger digital rights management technology. These approaches address piracy without requiring global infrastructure providers to implement jurisdiction-specific filtering, and they often prove more effective at eliminating piracy sources rather than just blocking access.

How does this dispute affect ordinary internet users?

If Piracy Shield enforcement spreads to other jurisdictions, users may experience slower internet speeds as infrastructure providers implement filtering at multiple chokepoints. Legitimate services may be disrupted due to overblocking. Different countries will impose different blocking requirements, meaning the internet will become increasingly fragmented. Users in countries with aggressive blocking laws may find certain services unavailable or degraded. The privacy and security implications of centralized content filtering at the infrastructure level remain unclear but potentially serious.

Conclusion: The Future of Internet Governance

Cloudflare's standoff with Italy isn't an isolated corporate dispute. It's a pivotal moment in internet governance that will influence how the internet functions for years to come.

On one side, you have governments and rights holders who want to enforce their laws and protect their intellectual property. That's a legitimate interest. Piracy costs businesses billions annually, and governments naturally want to prevent this within their borders. From AGCOM's perspective, Piracy Shield is a reasonable enforcement tool that works efficiently.

On the other side, you have infrastructure providers and internet advocates who believe that global infrastructure should remain neutral and that content control should happen elsewhere in the system. They argue that forcing infrastructure providers to implement jurisdiction-specific filtering fractures the internet and sets precedent for far worse restrictions. From Cloudflare's perspective, Piracy Shield represents a dangerous expansion of regulatory power with inadequate safeguards.

Both sides have valid points. The internet does need to respect national laws. Piracy is genuinely harmful to content creators and distributors. But the internet also benefits from being global and decentralized. Forcing global infrastructure to fragment by jurisdiction creates inefficiencies and opportunities for worse abuses.

The resolution of the Cloudflare-Italy dispute will shape which perspective prevails. If Cloudflare is forced to comply, it signals that infrastructure providers must implement jurisdiction-specific filtering, and we move toward a more fragmented, controlled internet. If Cloudflare successfully resists, it signals that infrastructure providers can push back against overreaching regulations, and we preserve more of the global internet as it currently exists.

Most likely, the truth will be somewhere in between. Some jurisdictions will impose rules on infrastructure providers. Some companies will comply while others won't. The internet will gradually become more fragmented, with different regions having different speeds, different available services, and different content policies. This isn't catastrophic—many people live in countries with restricted internet and manage fine—but it represents a meaningful shift from the relatively open internet of the past two decades.

For anyone paying attention to internet policy, this is the story to watch. The outcome will ripple through the entire tech industry and fundamentally reshape how the internet works.

Key Takeaways

- Italy's Piracy Shield law enables automated content blocking within 30 minutes but lacks judicial oversight, due process, or meaningful appeals

- Cloudflare's refusal is rooted in technical and legal concerns: DNS filtering adds latency and causes overblocking of legitimate services

- Research confirms significant overblocking: Google Drive suffered a three-hour outage and hundreds of legitimate sites were inadvertently blocked

- If Cloudflare capitulates, other jurisdictions will impose similar requirements, fragmenting the global internet into country-specific versions

- The dispute represents a pivotal decision about internet governance: whether global infrastructure remains neutral or becomes the enforcement mechanism for national content policies

Related Articles

- US Withdraws From Internet Freedom Bodies: What It Means [2025]

- Anna's Archive .org Domain Suspension: What It Means for Shadow Libraries [2025]

- Digital Rights 2025: Spyware, AI Wars & EU Regulations [2025]

- NordVPN in 2025: Post-Quantum Encryption, Scam Protection, and What's Next [2026]

- TechCrunch Disrupt 2026: Top Media & Entertainment Startups [2025]

![Cloudflare's $17M Italy Fine: Why DNS Blocking & Piracy Shield Matter [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cloudflare-s-17m-italy-fine-why-dns-blocking-piracy-shield-m/image-1-1767987451528.jpg)