Digital Rights in 2025: The Year Everything Changed

Something shifted in 2024. The world finally woke up to the fact that our digital lives weren't just being monitored—they were being weaponized.

It started quietly. A few news stories about spyware targeting activists. Some concern about AI companies training models on your personal data. The usual warnings about privacy that most people scrolled past. But then the pieces started connecting. Governments were buying surveillance tools that made Cold War spying look quaint. Tech companies were racing to deploy AI systems with almost no guardrails. And regulators in Europe? They were actually doing something about it.

By the end of 2024 and moving into 2025, it became impossible to ignore: digital rights were no longer an abstract concept for privacy advocates. They'd become a fundamental issue touching every person with a phone, email account, or social media profile. And the stakes were higher than most people realized.

This isn't just about VPNs or encrypted messaging anymore. The digital rights landscape of 2025 involves governments, corporations, AI systems, and billions of people caught in the middle. Some of these developments are genuinely concerning. Others are promising. Most are complicated in ways that traditional tech coverage completely misses.

Let me walk you through what actually happened in digital rights over the past year. Not the hyped-up version you'll see in headlines. The real story, with specifics that matter.

TL; DR

- Spyware became a global crisis: Government-backed surveillance tools like Pegasus targeted journalists, activists, and opposition politicians across multiple continents, with new variants emerging regularly

- AI surveillance scaled rapidly: Tech companies deployed AI systems that monitored user behavior at unprecedented scale, while AI-powered deepfakes and synthetic content created new privacy risks

- EU regulations actually started working: The Digital Services Act and emerging AI Act created enforceable rules with real penalties, reshaping how platforms operate globally

- Privacy became a luxury good: Only users willing to pay premium prices for privacy-focused services got meaningful protection, creating a two-tier system

- Bottom line: Your digital rights in 2025 depend on where you live, how much you spend, and whether you're willing to opt completely out of mainstream platforms

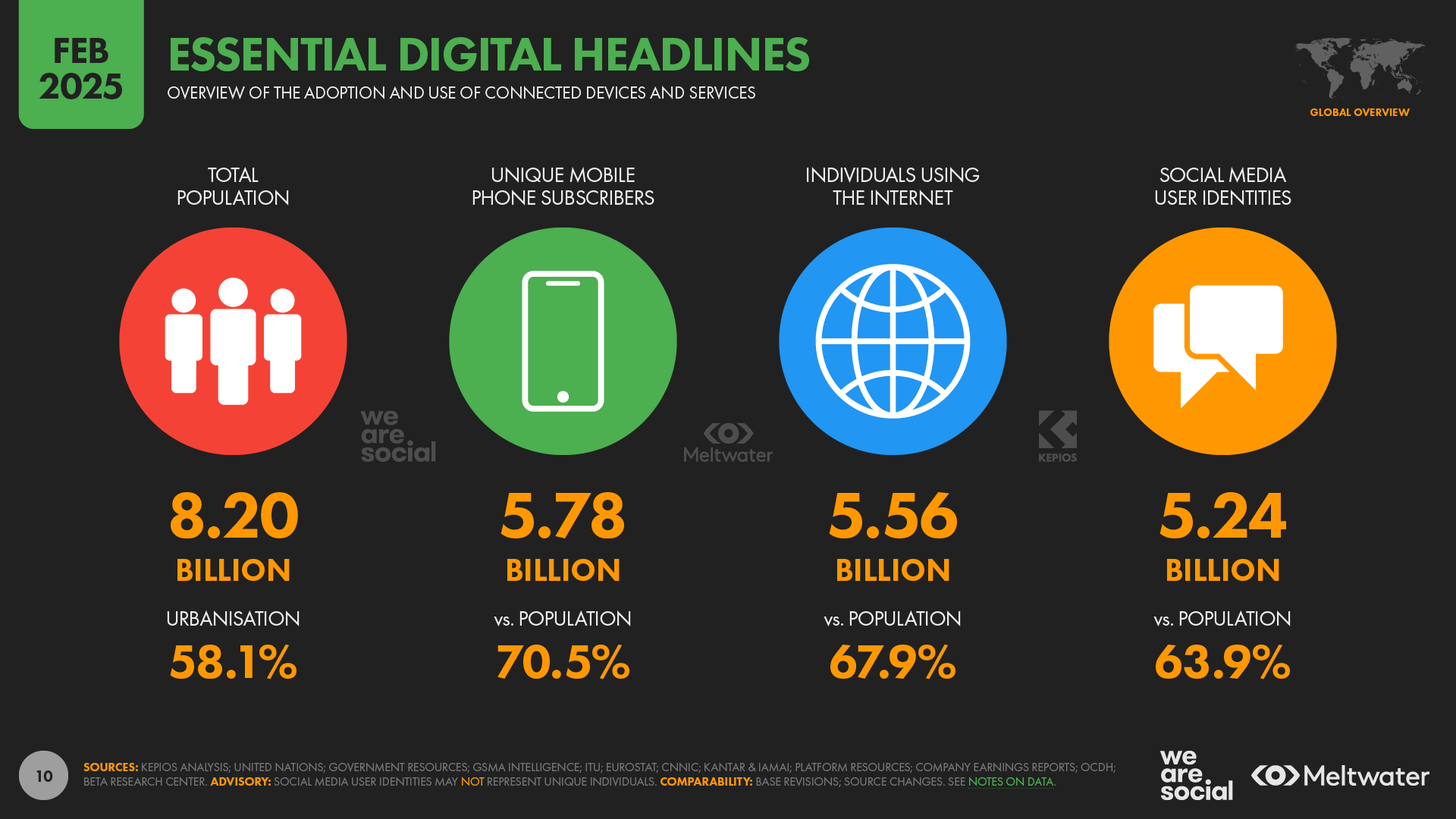

Estimated data shows that Asia and Europe had the highest number of countries using Pegasus spyware, highlighting the widespread adoption of surveillance tools across continents.

The Spyware Crisis Went Global and Got Worse

Let's start with the uncomfortable truth: if you've been touched by politics, activism, or journalism in certain parts of the world, your phone might already be compromised.

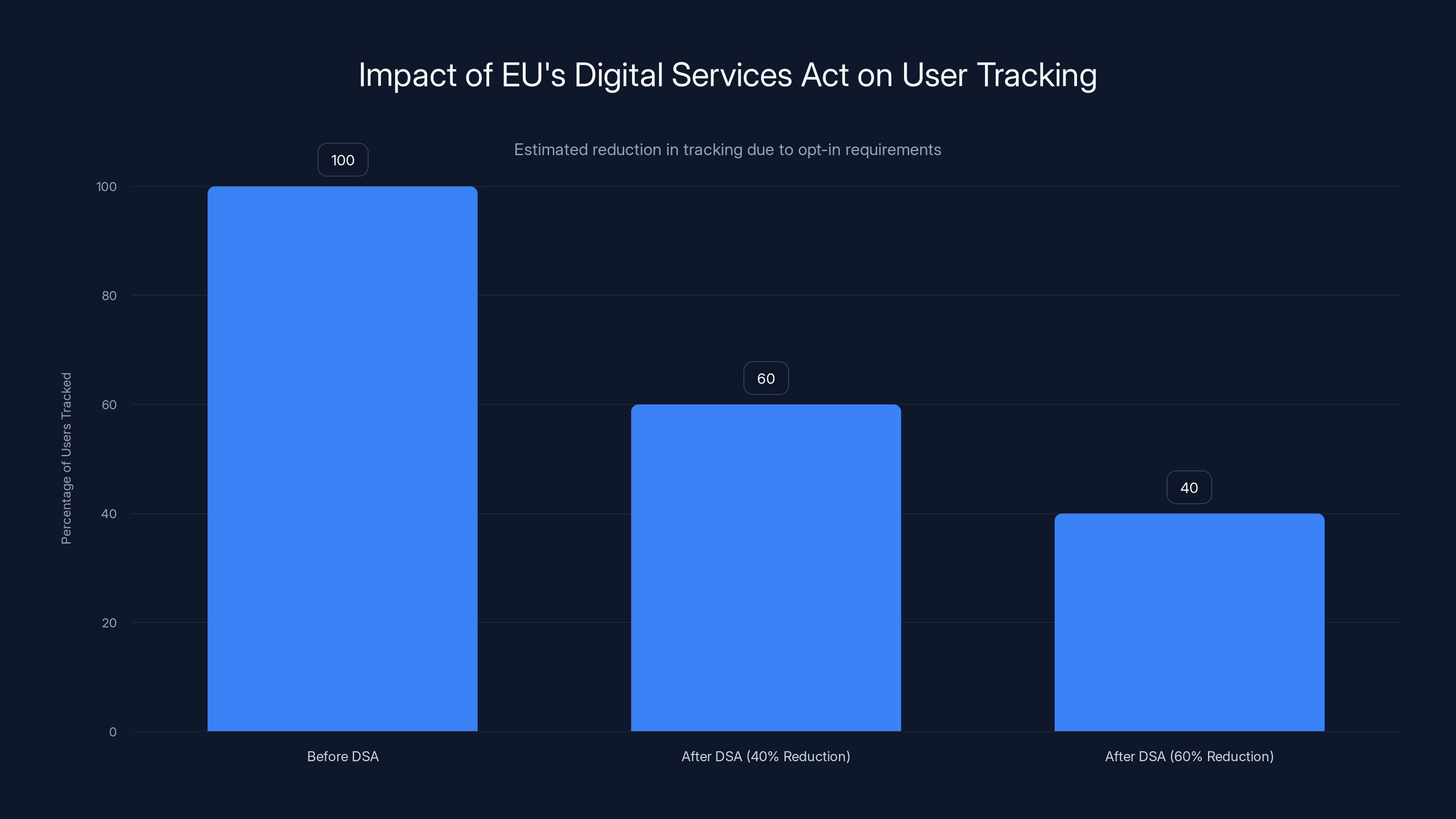

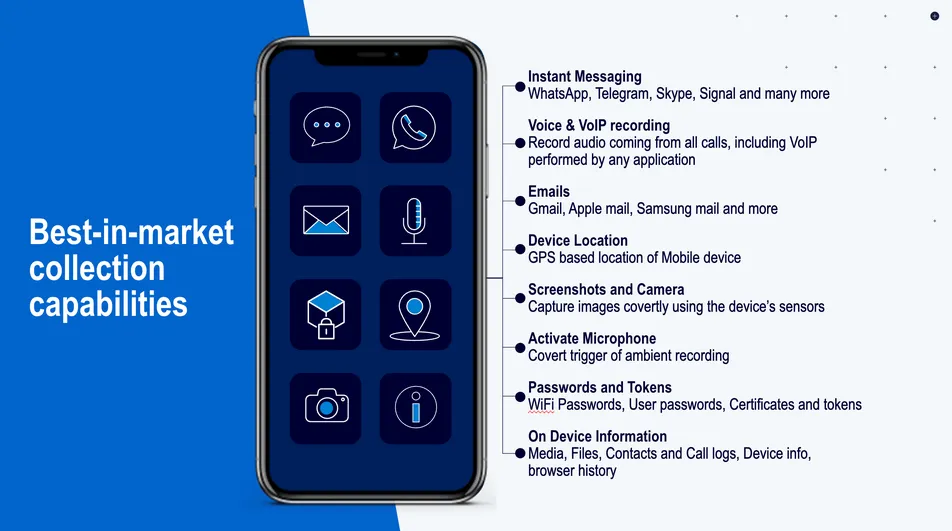

Spyware isn't new, but the scale and sophistication reached in 2024-2025 represents a qualitative shift. Forbidden Stories and Amnesty International released investigations showing that governments across multiple continents were systematically purchasing and deploying spyware tools against activists, journalists, and opposition politicians. We're talking about tools that could activate your phone's microphone without any indication. Tools that could read encrypted messages by accessing them before encryption happened. Tools that could photograph your location in real-time.

The scary part? Many of these tools were being sold openly by private companies. Citizen Lab, the digital research group at the University of Toronto, identified over 60 countries using NSO Group's Pegasus spyware alone. That's not a fringe problem. That's industrial-scale surveillance, and the governments buying it weren't shy about it.

Pegasus and the New Generation of Spyware

Pegasus became the public face of government spyware in 2024, but honestly, the situation was even more fragmented and chaotic than that.

NSO Group's Pegasus could do things that seemed impossible. It didn't require you to click a link or open a suspicious file. It could infiltrate your phone through a missed call. Through a photo in WhatsApp. Through iMessage. The infection was often invisible—no pop-ups, no performance degradation, nothing that would tip you off. Once in, it had access to everything: messages, photos, location history, passwords, and microphone feeds.

But Pegasus was just one tool in a growing arsenal. Research documented at least three other major spyware ecosystems operating simultaneously. Candiru's Fim 7 tool. Variston's Subzero. Positive Technologies' Voodoo. Each had slightly different capabilities, different pricing models, and different government clients.

What made 2024-2025 different from previous years? The tools got better at hiding. Previous generations of spyware would eventually degrade your phone's battery or cause glitches. The new generation? Essentially undetectable unless you knew exactly what you were looking for.

Who Was Actually Being Targeted?

This isn't hypothetical. Real people were being surveilled.

Journalists investigating corruption in Mexico found their phones compromised. Opposition politicians in India reported spyware on their devices. Human rights lawyers in multiple countries discovered they were being monitored. Women's rights activists in the Middle East had their locations tracked in real-time.

The pattern was consistent: if you threatened someone in power, your phone became a surveillance device against you. The sophistication meant you'd never know. You'd just be having private conversations that somehow turned into government action against you. Or your family members would be arrested based on information only you could have shared. Or your sources would dry up because sources realized their communications weren't safe.

This wasn't paranoia. This was documented, verified surveillance. And most targets never found out until journalists and researchers investigating the spyware ecosystem exposed it publicly.

The Countermeasures (That Didn't Work)

Apple and Google tried to fight back with OS-level protections, and they did help. But they weren't enough.

Apple's Lockdown Mode disabled certain features—auto-loading web content, some iCloud integration, USB connectivity—to reduce spyware attack surface. It helped. But determined attackers with zero-day exploits could still get in. Google implemented similar hardening in Android, but the fragmented Android ecosystem meant many devices never got the protections.

The real problem was fundamental: these tools exploited the gap between what the OS designers imagined users would do and what's actually possible with deep system access. Pegasus didn't just find bugs. It exploited assumptions about how software was supposed to work. Fixing one vulnerability just meant the spyware makers found another.

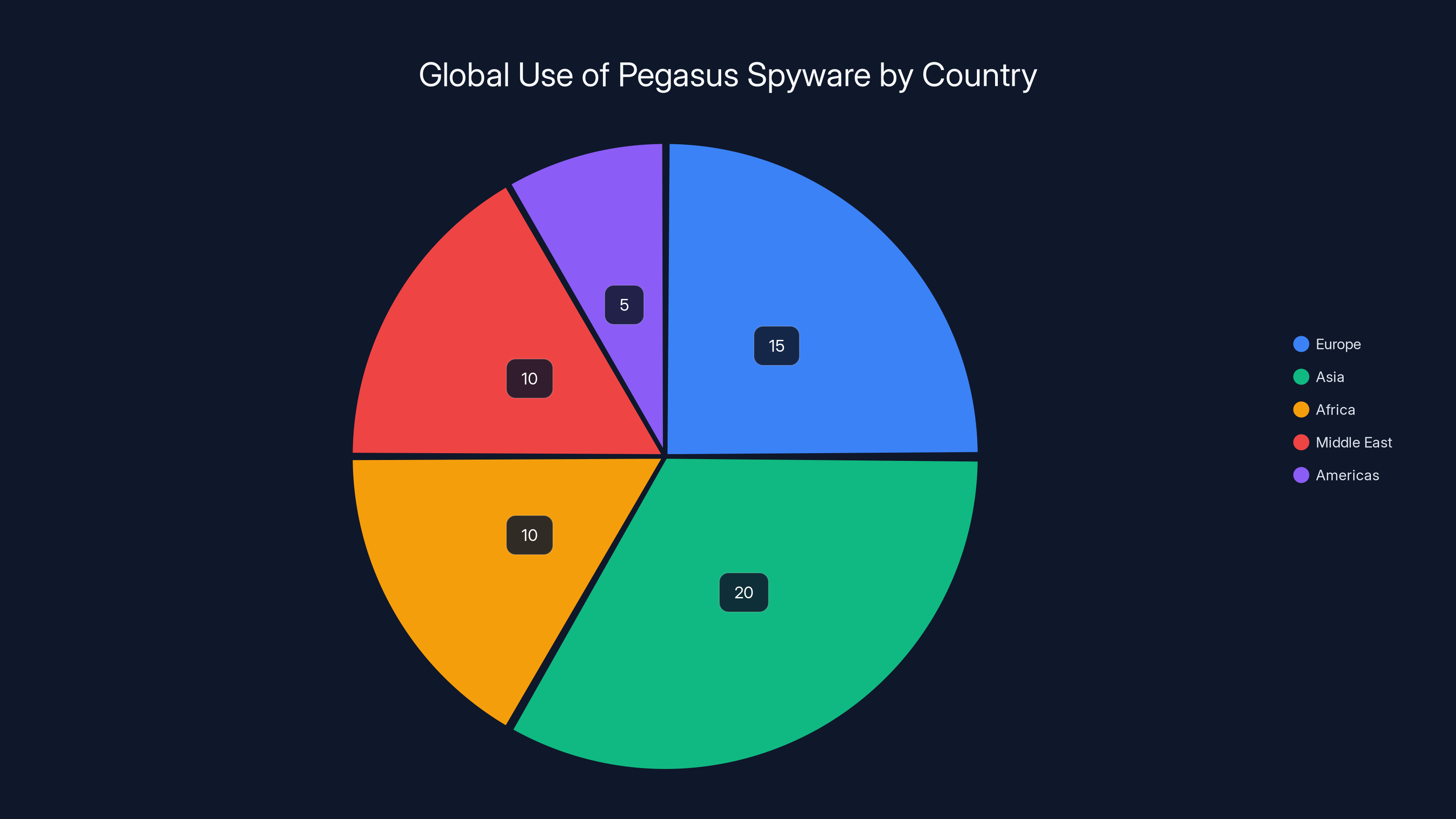

The EU's Digital Services Act led to a significant reduction in user tracking, with estimates suggesting a decrease of 40-60% among users who opted out of algorithmic personalization.

AI Became the New Surveillance Infrastructure

While governments were buying spyware tools, the tech industry was building something arguably more invasive: AI systems that monitored everyone, all the time, at scale.

This is the part people don't talk about enough. Spyware is terrifying, but it targets specific people. AI surveillance targets everyone. And unlike spyware, it's built into the platforms you're already using.

How AI Became an Omniscient Monitor

Starting in 2023 and ramping up through 2024, every major tech company deployed AI systems trained to analyze user behavior in real-time. Not the AI you talk to like ChatGPT. Different systems entirely. Systems designed to predict what you'd do next, who you'd talk to, what you'd buy, what political views you held, what personal secrets you harbored.

Google's AI systems could analyze your search history to predict health conditions before you saw a doctor. They could infer your sexual orientation, political beliefs, and personal struggles from your search patterns. Facebook's algorithms could predict whether you'd click on political content designed to manipulate you. TikTok's AI knew what would keep you on the app obsessively, and it exploited that knowledge ruthlessly.

The sophisticated part? This wasn't even hidden. It was in the terms of service. "We use AI to personalize your experience." Translated to English: "We feed everything you do into neural networks that predict and manipulate your behavior."

But the 2024-2025 escalation was different. Companies started using AI to infer information you explicitly didn't share. Your Bluetooth-enabled devices created networks that AI could analyze to determine who lived in your house. Your WiFi network name patterns indicated your interests. Your payment history revealed your political donations and religious affiliation.

The Deepfake and Synthetic Content Explosion

AI also became the weapon for creating convincing disinformation at scale.

Deepfakes in 2023 were impressive but obvious if you looked closely. By late 2024, they were nearly indistinguishable from reality. Tools existed that could create convincing video of anyone saying anything in minutes. The cost of creating a deepfake video dropped from thousands of dollars to essentially free.

Worse: the detection systems couldn't keep up. AI detection tools would beat deepfake creators for a few months, then the creators would find new techniques, and the detection tools would fail again. It became an arms race where the arms were getting cheaper and easier to deploy faster than defenders could respond.

The real damage wasn't just the deepfakes themselves. It was the psychological effect. If any video could be fake, how do you know what's real? By mid-2024, major news outlets couldn't publish video evidence without extensive forensic analysis. That was intentional—undermine trust in video evidence, and you undermine journalism.

AI-Powered Misinformation Campaigns

The combination of deepfakes and language models created new attack vectors.

Generative AI could produce realistic-sounding text at scale. Political campaigns could generate thousands of plausible-sounding personalized messages. Scammers could craft convincing phishing attacks in languages they didn't speak. Propaganda campaigns could be scaled to target millions of people simultaneously with personalized messaging.

The concerning part: these tools weren't particularly advanced. ChatGPT, Claude, and other language models required jailbreaks or workarounds to generate truly harmful content, but those workarounds were widely known. The barrier to entry for running a sophisticated disinformation campaign dropped from requiring a team of specialists to requiring one person with $20/month for an API subscription.

By late 2024, researchers estimated that 10-15% of viral social media posts in contested elections were entirely synthetic—created by AI, not by humans. That's not a small number. That's a structural threat to information integrity.

The EU Actually Started Enforcing Digital Rights

While the rest of the world struggled with spyware and AI surveillance, the EU did something radical: it passed laws with teeth and actually started enforcing them.

The Digital Services Act Changes Everything

The Digital Services Act (DSA) isn't the most exciting regulatory document. Reading it won't thrill you. But its impact was genuinely transformative in ways that affected every platform globally.

The DSA's core mechanism was simple: platforms operating in the EU had to be transparent about their algorithms. They had to provide users with options to opt out of algorithmic personalization. They had to remove illegal content within specific timeframes. And crucially, they had to face fines up to 6% of global revenue for violations.

That last part mattered. For Meta, 6% of global revenue meant billions of dollars. For Google, it meant existential pressure. The companies couldn't just ignore it or work around it.

So what actually changed? Three things:

First, algorithmic transparency became real. Users in the EU could now see why they were seeing specific content. They could request their data from platforms. They could understand, at least partially, how they were being manipulated.

Second, the default changed. Instead of being opted into tracking by default, EU users had to actively choose algorithmic personalization. Some reports suggested this reduced tracking by 40-60% for opt-in users.

Third, platforms started hiring compliance teams. Real people, with real expertise, dedicated to following European law. That might sound boring, but it meant that when regulators had questions, there were actual answers instead of runarounds.

The AI Act: Regulations for a Technology That Didn't Exist

The EU's AI Act was even more ambitious than the DSA. It tried to regulate AI itself—not just how platforms use AI, but the technology at a fundamental level.

The structure was risk-based. Prohibited AI (like social credit systems that score people). High-risk AI (hiring algorithms, law enforcement tools) that needed extensive testing and documentation. Limited-risk AI that needed transparency. Minimal-risk AI that was mostly unregulated.

The implementation was messy. What counts as "high-risk"? A hiring algorithm from a major tech company? Obviously. A resume-screening tool from a small startup? Less obvious. An AI that flags suspicious financial transactions? That seemed high-risk, but the financial industry pushed back.

But the structure forced a conversation that was missing globally. How should AI be regulated? What risks actually matter? What level of transparency should users expect?

By late 2024, the AI Act was still being finalized and implemented, but its influence was already spreading. Canada, the UK, and other jurisdictions were looking to European precedent. When the EU writes a law with enforcement mechanisms and real penalties, other governments eventually follow.

GDPR in Practice: Enforcement Gets Serious

GDPR, the European privacy law that went into effect in 2018, finally had enough legal precedent and enforcement mechanisms to actually matter in 2024-2025.

The fines weren't theoretical anymore. Meta was hit with a €1.2 billion fine for violating data protection rules around data transfers. Google faced €90 million for GDPR violations. These weren't small, forgettable expenses. They were signals that regulators were serious.

More importantly, GDPR enforcement created case law. Courts ruled that certain common practices—like forcing users to accept all tracking to access a service, or making it harder to opt out than opt in—were violations. Each ruling became precedent for the next enforcement action.

By 2025, the legal landscape around user data had fundamentally shifted. It was no longer a question of "can companies get away with this?" It was "how long until they're caught and fined?"

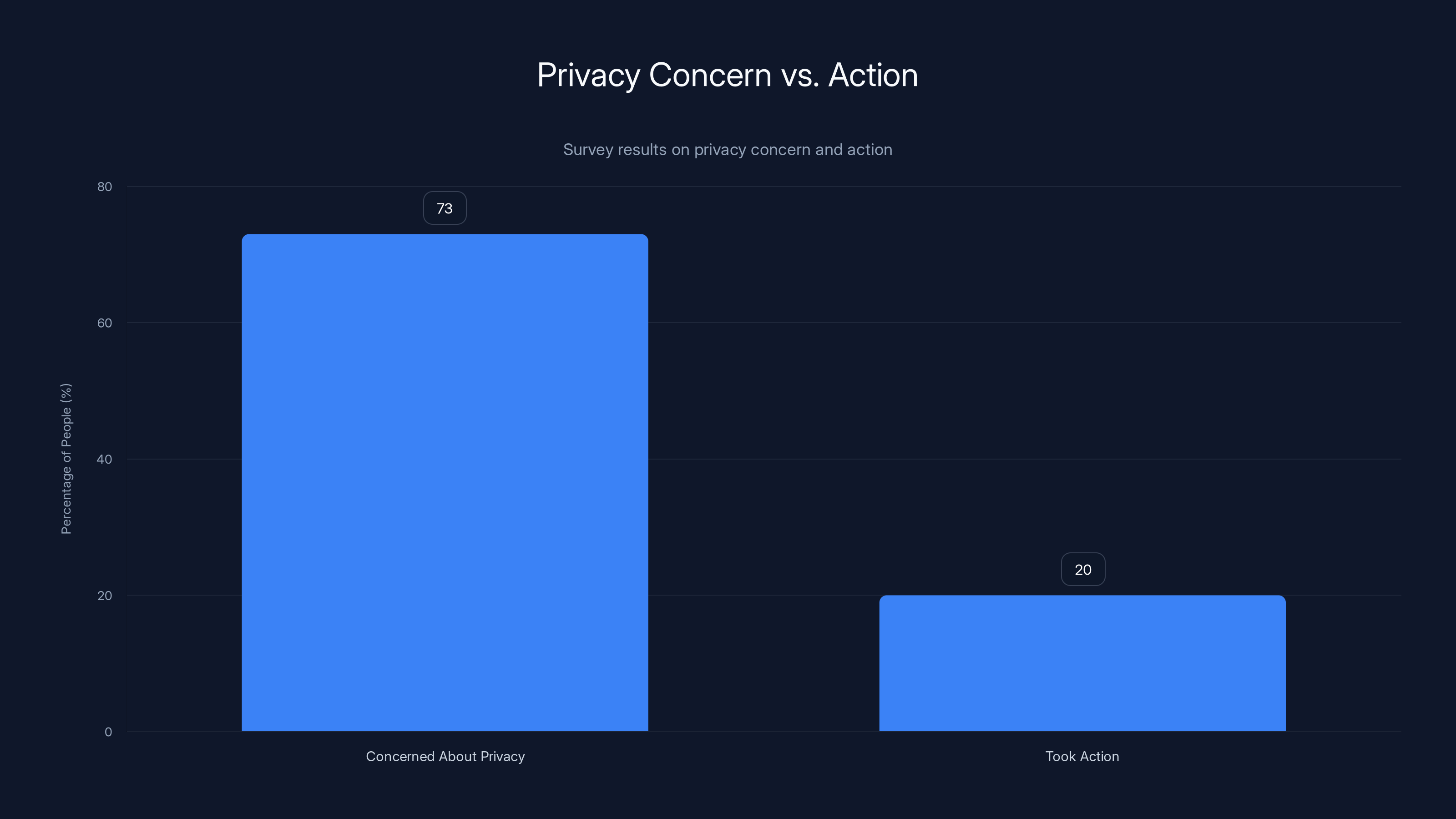

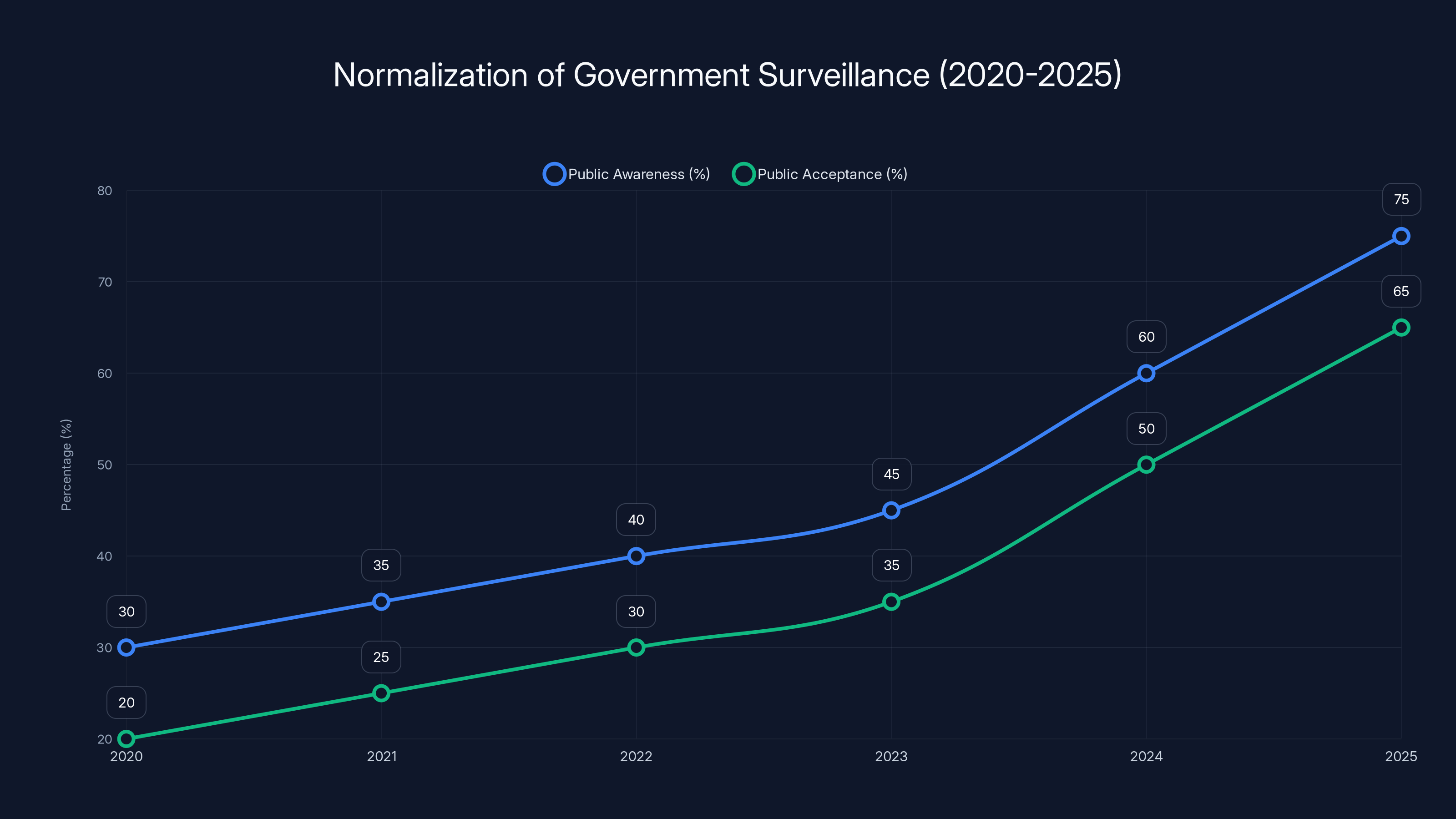

Despite 73% of people being concerned about privacy, less than 20% actually took steps to protect themselves, highlighting a significant gap between awareness and action.

The Privacy Paradox: Knowing Doesn't Mean Protecting

Here's the uncomfortable part that most digital rights discussions avoid: awareness about privacy threats didn't actually translate into people protecting themselves.

In surveys, 73% of people said they were concerned about privacy. When asked if they actually did anything about it, the number dropped to under 20%. People installed VPNs at high rates when they made news, then stopped using them. They read about spyware, nodded along, and continued using Facebook. They learned about data collection, felt briefly violated, and continued living the same digital lives.

Why? Several reasons.

Structural Helplessness

First, the problem was too big for individual solutions. You could encrypt your messages, but if the other person wasn't encrypting theirs, you had a vulnerability. You could use a privacy-focused browser, but everyone else used Chrome. You could avoid Facebook, but you'd lose access to community groups, marketplace, and event planning.

The infrastructure didn't offer genuine opt-out. Opting out meant opting out of modern life. That's not a real choice.

Convenience Tax on Privacy

Second, privacy had a convenience cost. Privacy-focused tools often required more setup, more manual configuration, more friction. Privacy-respecting services required payment (see: ProtonMail, Signal). The convenient options all involved trading privacy.

Most people chose convenience.

The Exploitation of Fatigue

Third, there was "privacy fatigue." After years of hearing about breaches, data collection, and surveillance, people just stopped caring. The threat felt abstract. Their daily lives didn't change when data was breached. The fines that companies paid were trivial compared to their revenue. Apathy won.

It's worth noting that this fatigue was partially manufactured. Companies with incentive to maximize data collection funded research and ran campaigns suggesting privacy concerns were overblown. They funded think tanks that published papers arguing regulation would stifle innovation. They created just enough doubt that people could convince themselves everything was fine.

Government Surveillance Went Mainstream (Not Just Hidden)

Before 2024, government surveillance was something authoritarian regimes did. Democratic governments, we were told, had oversight and laws protecting citizens.

That story broke in 2024-2025.

The Democracy Intelligence Agencies Problem

Documented cases showed that intelligence agencies in democratic countries were using spyware and surveillance tools in ways that violated their own laws. Agencies were supposed to have warrants. Instead, they had vague justifications. Oversight committees were supposed to actually review surveillance programs. Instead, they received briefings and rubber-stamped everything.

The most concrete example: GCHQ, the British signals intelligence agency, was storing data on millions of people without apparent legal basis. When courts reviewed the programs, they found systematic violations of privacy law. The punishments? Procedural fixes that didn't meaningfully change how the surveillance worked.

In the US, the Electronic Frontier Foundation documented that the NSA was conducting bulk surveillance of Americans' phone records without congressional authorization. Congressional authorization for that surveillance had lapsed in 2020. For four years, the agency continued the program anyway.

The Normalization of Mass Surveillance

What made 2024-2025 different wasn't that governments were conducting surveillance. They'd been doing that forever. It was that the surveillance became normalized. It wasn't hidden in classified programs anymore. It was part of public infrastructure.

City governments deployed surveillance cameras that used facial recognition to identify wanted suspects. The technology worked sometimes. The accuracy was ... imperfect. But the deployment continued. Innocent people were arrested based on false facial recognition matches, and the only consequence was that the department improved their process slightly.

Airports used biometric systems that tracked you through checkpoints. Phone companies collected location data and sold it to marketing companies and, occasionally, law enforcement. Internet service providers logged which websites you visited and made that available to law enforcement without warrants.

Each piece individually seemed reasonable. Taken together, they created a surveillance apparatus that would have seemed like science fiction in 2000.

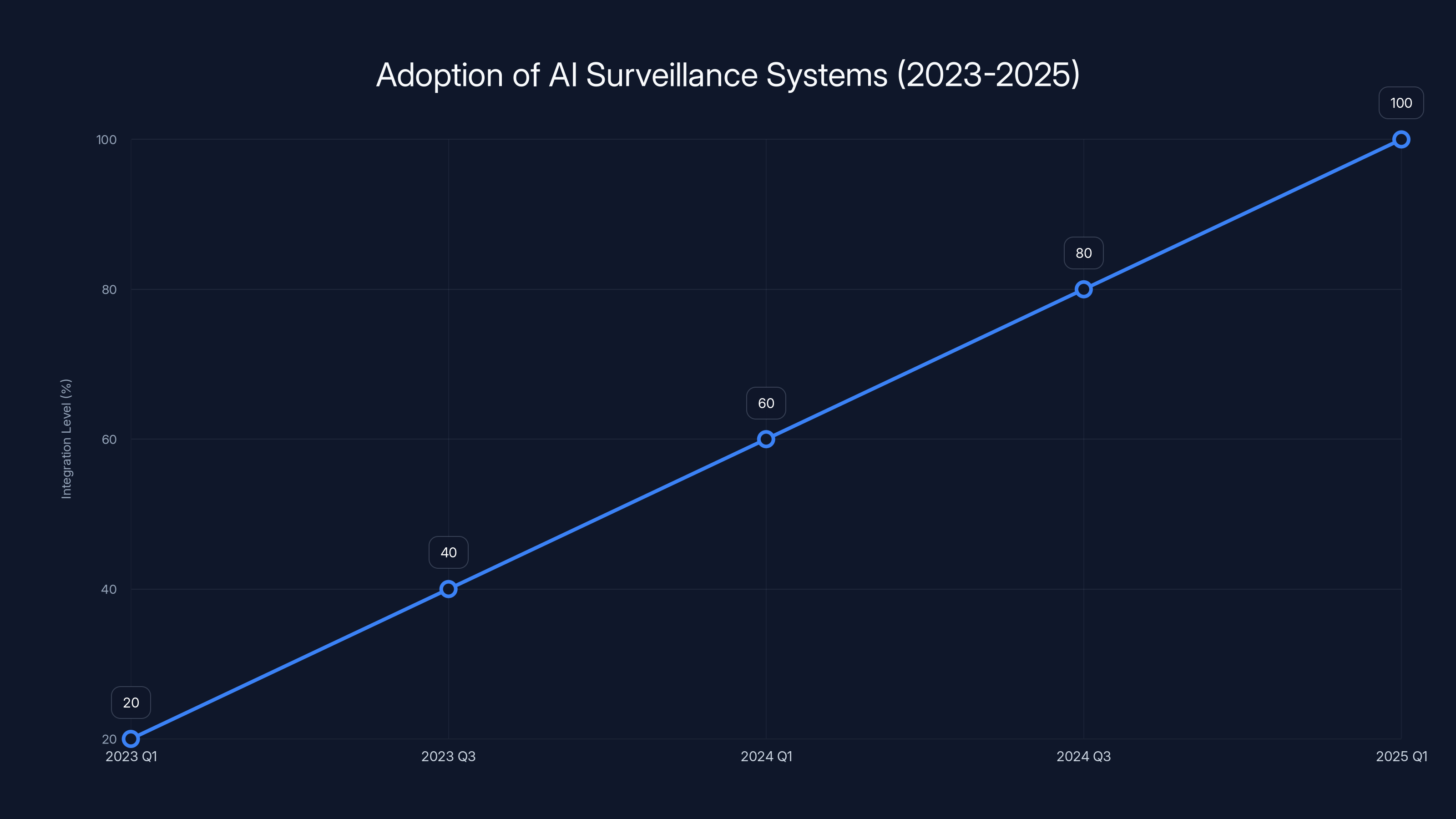

Between 2023 and 2025, the integration of AI surveillance systems by major tech companies is estimated to have increased significantly, reaching full deployment by early 2025. (Estimated data)

The Data Broker Ecosystem Exploded

While governments were building surveillance infrastructure, a private industry was building something complementary: data brokers who aggregated, analyzed, and sold information about billions of people.

You know about some data brokers. Acxiom is the famous one. But by 2024, there were hundreds. Equifax, TransUnion, Experian (the credit agencies). Lots of lesser-known ones: Intelius, PeopleSearch, WhitePages.

These companies had files on billions of people. They knew your address. Your phone number. Your family structure. Your shopping habits. Your medical conditions (inferred from your purchases). Your political leanings. Your sexual orientation. Your financial situation.

Some of this data came from legitimate sources: public records, voter registration data, property records. But most came from data brokers buying and selling information from tech companies, retailers, and data aggregators. It was an entire ecosystem built on the principle that information about people is a commodity to be bought and sold.

The horrifying part: you couldn't really opt out. Some brokers had opt-out mechanisms, but they were obscure and didn't always work. Opting out of one broker didn't help because another had the same data. By the time you found out data brokers had information about you, they'd already sold it dozens of times.

Data Brokers Enabling Abuse

The real damage happened when this data flowed to bad actors. Abusive partners used data broker services to stalk their exes. Scammers used data broker information to create convincing social engineering attacks. Law enforcement sometimes used data brokers to bypass warrant requirements (buying data that intelligence agencies couldn't legally collect).

By late 2024, several states had passed laws restricting data brokers. Vermont required data brokers to register and disclose what data they collected. California gave people the right to know what data brokers held on them. But these regulations applied to brokers operating in those states. The infrastructure remained essentially unchanged.

The Pushback: Privacy Tech Grew Up

Not everything in 2024-2025 was dystopian. There was genuine progress on the privacy technology front.

Privacy-Respecting Tools Went Mainstream

Signal grew from niche security tool to messaging app with hundreds of millions of users. Tor had more users. ProtonMail and Tutanota offered truly encrypted email. DuckDuckGo grew as a privacy-respecting search alternative.

The key change: these tools became user-friendly enough that non-technical people could actually use them. That mattered. Privacy technology only works if normal people can use it.

Acceptance expanded too. Using encrypted messaging stopped seeming suspicious. Using a VPN became common practice. Caring about privacy stopped being a fringe concern.

Open-Source Alternatives Matured

NextCloud became a genuinely functional Dropbox alternative. Matrix created decentralized messaging infrastructure. Pixelfed, Mastodon, and other Fediverse projects offered alternatives to corporate social media.

These projects had limited adoption compared to mainstream platforms. But they existed. They worked. They offered a genuinely different model.

The most interesting development: big tech companies started noticing. Apple began moving toward on-device machine learning to avoid storing personal data on Apple servers. Google started shipping privacy-preserving technologies, though with mixed results.

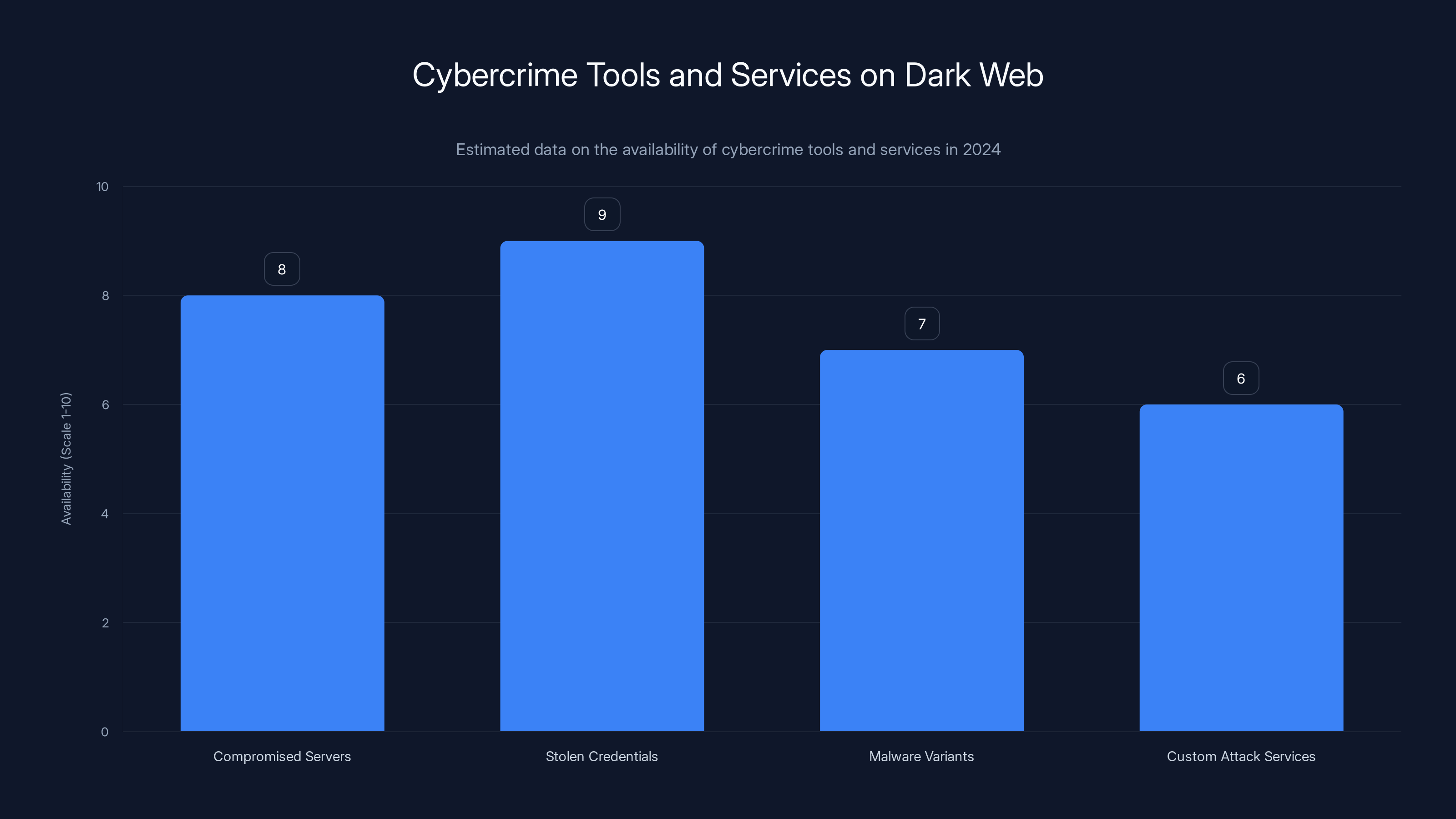

Estimated data shows that stolen credentials and compromised servers were highly available on dark web marketplaces in 2024, making it easier for cybercriminals to execute sophisticated attacks.

The Great Privacy Divide: Class-Based Digital Rights

By 2025, something uncomfortable became obvious: digital rights were increasingly separated by class.

If you had money, you could buy privacy. Privacy-focused tools and services cost money. ProtonMail Premium cost money. VPN services cost money. Privacy-respecting hosting cost more than privacy-invading hosting. Phone manufacturers that prioritized privacy (Apple) cost more than those that monetized surveillance (many Android manufacturers).

For most people, though? The private option was convenience and free services that collected data. If you wanted to use a computer without providing data to tech companies, you were living differently from everyone else. You couldn't use popular apps. You couldn't integrate with institutional systems. You were opting out of modern life.

This created two digital classes: people who paid for privacy and accepted missing some conveniences, and people who accepted surveillance and got convenience.

The middle ground kept disappearing. You couldn't have privacy at scale without paying. You couldn't have convenience at scale without surrendering data.

The Surveillance Escalation Dilemma

There was a feedback loop making this worse. As companies invested in surveillance (because it made them money), privacy-conscious people had fewer options. As fewer people used privacy tools, companies had less incentive to build privacy features. Privacy became a niche product.

At the same time, the people most needing privacy—activists, journalists, vulnerable populations—were often the least able to afford premium privacy services. The people who could afford privacy were often the least at risk.

This inversion wasn't accidental. It was the natural result of turning privacy into a commodity.

The Corporate Privacy Theater Problem

Big tech companies weren't quietly breaking privacy laws. Many of them publicly announced privacy commitments. The problem was that the commitments were theater.

The Illusion of Transparency

Companies would announce "privacy controls" that technically gave users options. But the defaults collected maximum data. Making privacy your default required multiple clicks in buried menus. Many users never found the settings. Months after a privacy announcement, research would show that most users still had data collection enabled by default.

The Definition Trick

Companies would redefine what counted as "personal data." If data was anonymized, it wasn't personal data (even though it often could be re-identified). If data was aggregated, it wasn't about individuals (even though aggregate data revealed patterns about specific groups). If data was used for "improving services," it was exempt from restrictions (even though improving services and targeting advertising used identical mechanisms).

The Impossible Compliance

Companies would create privacy policies so complex that no reasonable person could understand them. Technically compliant. Practically impossible to parse. The actual terms of data collection buried in subsection of subsection of subsection.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in public awareness and acceptance of government surveillance from 2020 to 2025, highlighting the normalization of such practices.

Cybercriminals Weaponized Surveillance Infrastructure

It's easy to focus on governments and corporations. But organized crime got sophisticated too.

The Dark Web Matured

The dark web wasn't hidden anymore in the sense that law enforcement couldn't find it. Silk Road had been shut down. Major marketplaces were regularly busted. But the infrastructure remained. New marketplaces launched. Sophisticated criminals used increasingly sophisticated techniques to avoid detection.

More importantly, the tools available on dark web marketplaces got better. You could buy access to compromised servers. You could buy stolen credentials. You could buy malware variants. You could hire actual programmers to customize attacks.

The barrier to entry for cybercriminals dropped. You didn't need specialized knowledge anymore. You just needed money and the ability to navigate dark web marketplaces.

The Ransomware Epidemic

Ransomware wasn't new, but the sophistication and scale reached in 2024-2025 was unprecedented. Ransomware groups weren't just encrypting files and asking for payment. They were exfiltrating data, threatening to release it, and extorting multiple parties.

They targeted hospitals. They locked patients out of critical systems. People died because their medical records were encrypted and unavailable. The attackers got paid anyway.

They targeted infrastructure. Power plants. Water treatment facilities. The attacks didn't actually cause major outages, but they could have. The only thing stopping catastrophic damage was luck.

The Credential Marketplace

Stolen credentials became a commodity. Your email and password, if stolen in a breach, would end up on dark web marketplaces within weeks. For $5, someone could buy access to your email account. With your email, they could reset passwords for other accounts. They could use your identity for credit fraud. They could sell access to other criminals.

The scale was incomprehensible. By 2024, billions of stolen credentials were available for sale. Major breaches would dump hundreds of millions of credentials. The market price per credential was at all-time lows (literally pennies) because supply so massively exceeded demand.

International Digital Rights Chaos

Different countries were running different experiments with digital rights, creating a fractured landscape.

The Chinese Surveillance Model Spread

China's social credit system, which scores people based on their behavior and restricts opportunities for low-scorers, was adopted in modified forms by other countries. Russia built surveillance infrastructure to identify and arrest protesters. Iran used surveillance to target opposition groups. Hong Kong enacted laws allowing surveillance that would have seemed dystopian elsewhere.

The concerning part: these weren't isolated to authoritarian regimes. Democratic countries were moving in similar directions. Not the explicit social credit system, but the infrastructure: integrated databases, algorithmic decision-making, surveillance networked across agencies.

The Data Localization Wars

Countries started mandating that data about their citizens stay within their borders. India required personal data to be stored in India. Russia mandated local data storage. These rules framed themselves as protecting citizens, but they also gave governments easier access to the data, and they fragmented the internet.

The result: the global internet was splintering into regional internets. Data couldn't move freely. Services couldn't operate globally. This fragmenting made life harder for normal users and easier for governments to control information flow.

The TikTok Obsession

Every democratic country became obsessed with TikTok. The argument was that Chinese ownership meant the Chinese government could access user data. Which was probably true. But the same concerns applied to American social networks and their relationships with US intelligence agencies—a point that was carefully not mentioned.

The obsession reflected something real though: massive platforms concentrating power in the hands of a single company created risks. But the solution wasn't banning TikTok. It was decentralizing social media. Actually building the alternatives that open-source communities had been working on for years. Funding them. Supporting them.

Instead, democracies just argued about whether to ban specific foreign apps while doing nothing to fix the underlying structural problem.

What Actually Worked: Small Victories

Despite the dystopian elements, some things actually improved in 2024-2025.

Right to Repair Gets Real

Right to repair legislation started passing. New York passed a law requiring manufacturers to sell parts and provide repair manuals. The EU moved toward similar rules. This might seem unrelated to digital rights, but it's connected: repair prevents manufacturers from forcing you to buy new devices, which means you can keep using older phones with better privacy protections if you choose.

Algorithm Audit Frameworks

Regulators started developing frameworks for auditing algorithms. The FTC began conducting algorithmic audits of major platforms. The results were embarrassing for the companies (and should have been for regulators—they let it get that bad), but they also showed that auditing was possible. You could look at what an algorithm was doing and hold it accountable.

Encryption Remains

Despite governments pushing for backdoors, encryption remained strong. End-to-end encrypted services continued to be available. Signal remained uncompromised. Tor still worked. The technical foundation for privacy remained intact.

Governments couldn't force mathematical weaknesses into encryption. They could harass companies. They could pass laws. But they couldn't break math. That was something.

Predictions for 2025 and Beyond

Based on what happened in 2024-2025, several things seem likely to continue.

Surveillance Will Keep Escalating

Governments and companies have invested too much in surveillance infrastructure to abandon it. The surveillance won't stay still. It will get more sophisticated. It will get more integrated. It will become harder to opt out of.

The only counterbalance is regulation. If regulators treat surveillance as something that needs limits, it can be slowed. If they don't, it accelerates.

Privacy Will Stay Expensive

Privacy-respecting tools will remain expensive because privacy tools can't monetize surveillance. They have to charge money. As surveillance becomes more normal, the willingness to pay for privacy might decrease, making it harder for privacy companies to survive.

This is a real risk: privacy tools go out of business because not enough people will pay for them, creating a monopoly for surveillance-based services.

AI Regulation Will Continue, Imperfectly

The EU will continue pushing AI regulation. Other jurisdictions will eventually follow. The regulations will be imperfect and won't address all the risks. But they'll force companies to at least think about risks they'd previously ignored.

The Internet Will Keep Fragmenting

Data localization requirements, different regulatory standards, and geopolitical tensions will continue pushing toward regional internets. The global internet won't disappear, but it will become less global and more fragmented.

What You Can Actually Do

Given this landscape, here's what actually helps:

Accept That Perfect Privacy Isn't Possible

You're not going to have complete privacy in 2025. The best you can do is meaningful privacy for things that matter most to you. Choose your battles. You probably can't avoid all data collection. But you can probably minimize it for sensitive areas.

Use Signal for Sensitive Communication

Signal actually works. It's not perfect. The metadata (who you're talking to) still shows. But the content is secure. If you're having confidential conversations, use it.

Consider a VPN for General Browsing

A VPN doesn't make you anonymous. It hides your traffic from your ISP and some tracking. It helps. Not perfect, but helps. Mullvad, ProtonVPN, and ExpressVPN are all reasonable choices.

Use DuckDuckGo or Similar for Search

DuckDuckGo isn't perfect, but it doesn't build a profile on you like Google does. That matters.

Use Different Passwords Everywhere

If one service gets breached and your credentials are stolen, attackers should only have access to that one account. Use a password manager. Bitwarden is free and open-source. 1Password is commercial.

Accept That Some Services Require Data Sharing

You probably need an email account. You probably need some way to contact people. You might need to use platforms where everyone else is. Accept that and focus privacy efforts on the most sensitive communications.

The Bottom Line

2024 and the start of 2025 showed us what a world with weaponized digital infrastructure looks like. Governments with spyware. Companies with AI surveillance. Criminals with access to billions of stolen credentials. Internet fragmenting along national lines.

But it also showed us that pushback is possible. The EU actually passed regulations with enforcement mechanisms. Privacy tools went mainstream. People became aware of the problem.

Digital rights in 2025 aren't guaranteed. They require active defense. They require regulation. They require technology. They require people choosing to value them even when convenience suggests otherwise.

The year ahead won't be easier. Surveillance technology will get better. AI will get better. The economic incentives pushing toward data collection will remain. But awareness is there now. The foundation for pushback exists.

What happens next depends on whether enough people decide digital rights matter.

FAQ

What is the Digital Services Act and how does it affect me?

The Digital Services Act (DSA) is European Union legislation requiring platforms to be transparent about their algorithms and remove illegal content within specific timeframes. If you're in the EU, it gives you the right to see why platforms show you specific content and to opt out of algorithmic personalization. Even if you're outside the EU, it affects you because major platforms have had to change globally rather than maintain separate systems for different regions.

How can spyware infect my phone if I'm careful?

Modern spyware like Pegasus doesn't require you to click anything. It can infect your phone through a missed call in WhatsApp, a photo in iMessage, or a file you receive but never open. The sophisticated part is that once installed, it's essentially invisible—no battery drain, no performance degradation, nothing that would tip you off. Amnesty International offers a security check tool, but the most reliable protection is having a security team actively protecting you, which most people don't have access to.

Is encryption actually safe from government backdoors?

Mathematically, yes. Governments can't force weaknesses into encryption math—that's just impossible. They can harass companies that make encrypted services. They can pass laws. But they can't break encryption itself. So services like Signal that use strong encryption remain secure. The problem is metadata (who you're talking to), which is separate from the encrypted content.

What's the difference between a VPN and using Tor?

A VPN encrypts your traffic and routes it through a VPN server, hiding your IP address from websites. Tor routes your traffic through multiple servers, making it much harder to trace. Tor is more private but slower and doesn't encrypt everything (DNS queries might leak). A VPN is faster but depends entirely on whether the VPN provider logs traffic and shares it. Tor is free and open-source. Most VPNs cost money. Both have legitimate uses and security trade-offs.

Why do data brokers have information about me if I've never given it to them?

Data brokers buy information from many sources: public records, voter registration data, property records, but mostly from other companies that have collected data about you. That retailer you bought from? They sold your information. That app you installed? It sold location data. That website you visited? It shared browsing behavior. Each transaction is usually legal because of privacy policies you agreed to without reading. Opting out requires contacting individual brokers, which is tedious and doesn't work completely.

Should I be worried about AI creating deepfakes of me?

Depending on your public profile, yes. If you're a public figure, someone could create a deepfake. The technology is easy and cheap. If you're a private person, you're lower priority. But the real risk is deepfakes of public figures used to spread disinformation, which affects everyone because it undermines trust in any video evidence. The concerning part isn't individual deepfakes—it's the systemic erosion of trust in media.

What's the most important thing I can do for digital privacy right now?

Choose what information matters most to you and protect that. You can't protect everything without becoming a hermit. But you can use Signal for sensitive conversations, use different passwords everywhere (with a password manager), and consider a VPN for general browsing. Accept that some convenience will be sacrificed and some data will be collected. Privacy in 2025 is about being intentional, not being perfect.

Digital rights matter in 2025 more than ever. The infrastructure for surveillance is real. The regulations are starting to exist. The tools for protecting yourself are available. What's missing is the collective commitment to demand better. That starts with individuals choosing to care, which means you.

Key Takeaways

- Spyware like Pegasus represents industrial-scale government surveillance that can infiltrate phones without user interaction, targeting activists, journalists, and opposition figures across 60+ countries

- AI surveillance systems now analyze user behavior at unprecedented scale across platforms, inferring sensitive personal attributes and enabling manipulation through algorithmic optimization

- The EU's Digital Services Act and AI Act created enforceable regulations with significant penalties (up to 6% of global revenue), forcing global platforms to change operational practices

- A two-tier privacy system emerged where meaningful digital rights protection requires either premium paid services or technical expertise, creating inequality in privacy access

- Data broker ecosystems enable surveillance by aggregating information from hundreds of sources, making effective opt-out nearly impossible despite legal efforts to increase transparency

Related Articles

- Age Verification Changed the Internet in 2026: What You Need to Know [2025]

- The Complete Guide to Breaking Free From Big Tech in 2026

- California's DROP Platform: Delete Your Data Footprint [2025]

- VPN Regulation & Legislation in 2026: Loopholes, Laws & What's Next [2025]

- The Complete Tech Cleanup Checklist for 2025: 15 Essential Tasks

- US Removes Spyware Executives From Sanctions: What Actually Happened [2025]

![Digital Rights 2025: Spyware, AI Wars & EU Regulations [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/digital-rights-2025-spyware-ai-wars-eu-regulations-2025/image-1-1767607646893.png)