The Flu Problem We Can't Seem to Solve

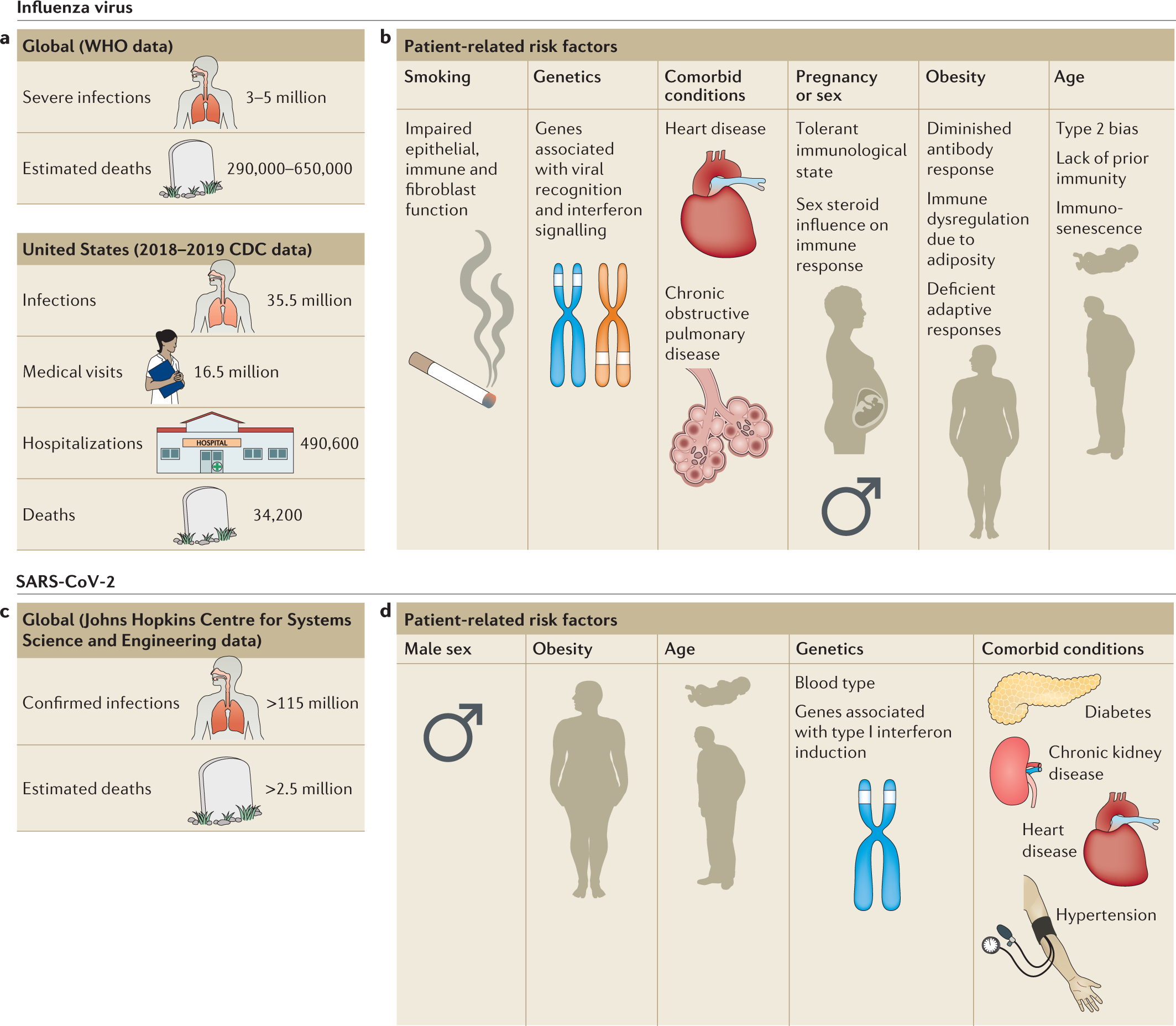

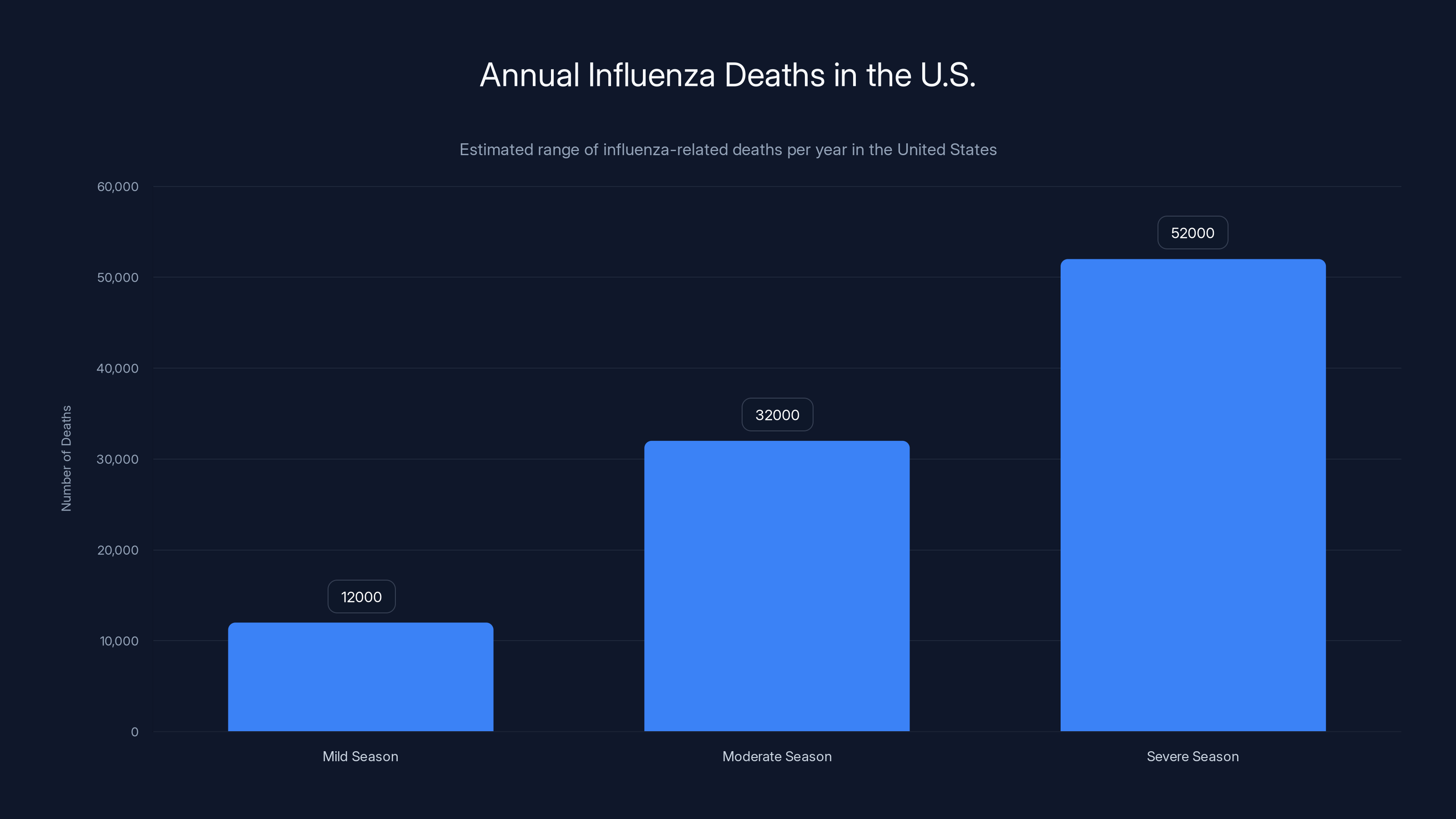

Influenza kills between 12,000 and 52,000 Americans every single year, depending on how brutal the flu season gets. That's not a typo—the range is genuinely that wide. Some winters are manageable. Others are absolute nightmares. And what makes this even more frustrating? We've had flu vaccines for decades. We have antiviral drugs like Tamiflu. We have public health campaigns telling people to wash their hands. Yet the flu keeps finding ways around everything we throw at it.

The problem is fundamental. Influenza mutates constantly. Think of it like playing whack-a-mole with an opponent who's learning your strategy every single game. Traditional antivirals target specific parts of the virus, which means the virus adapts, gains resistance, and suddenly your drug is useless. Vaccines are created months in advance based on predictions about which strains will circulate, but those predictions are educated guesses at best.

What if we could change the game entirely? Instead of fighting the flu with yesterday's weapons, what if we could use cutting-edge gene-editing technology to rewrite the rules?

That's where CRISPR comes in. And specifically, a less-famous cousin of the CRISPR system that's already making headlines in rare disease treatment. Researchers at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne have started developing something genuinely novel: using CRISPR-Cas 13 as a next-generation antiviral that could work against all flu strains simultaneously.

This isn't science fiction. The research is real, the early results are promising, and the implications are staggering.

TL; DR

- CRISPR-Cas 13 targets viral RNA directly, exploiting a fundamental vulnerability in how influenza viruses replicate

- Early lab studies show the technology can neutralize multiple flu strains including H1N1 and H3N2, without the off-target damage previously feared

- The delivery method uses lipid nanoparticles in a nasal spray or injection, similar to mRNA vaccine technology

- Key challenges remain: immune response to bacterial proteins, delivery to deep lung cells, and potential viral mutation acceleration

- Clinical trials are still years away, but the foundation is solid enough that major research institutions are investing resources

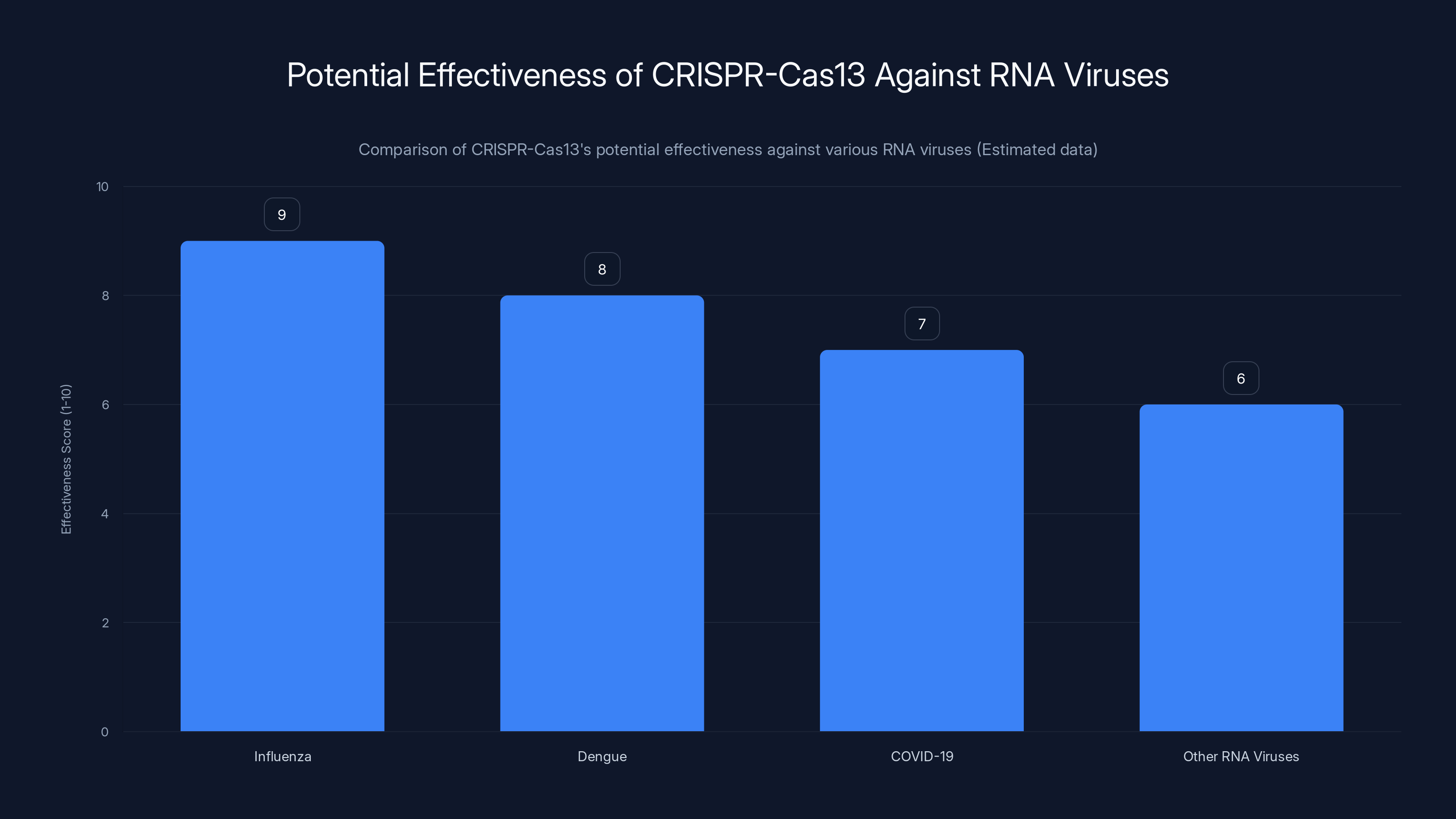

CRISPR-Cas13 is projected to be highly effective against influenza and dengue, with slightly lower effectiveness against COVID-19 and other RNA viruses. Estimated data based on current research.

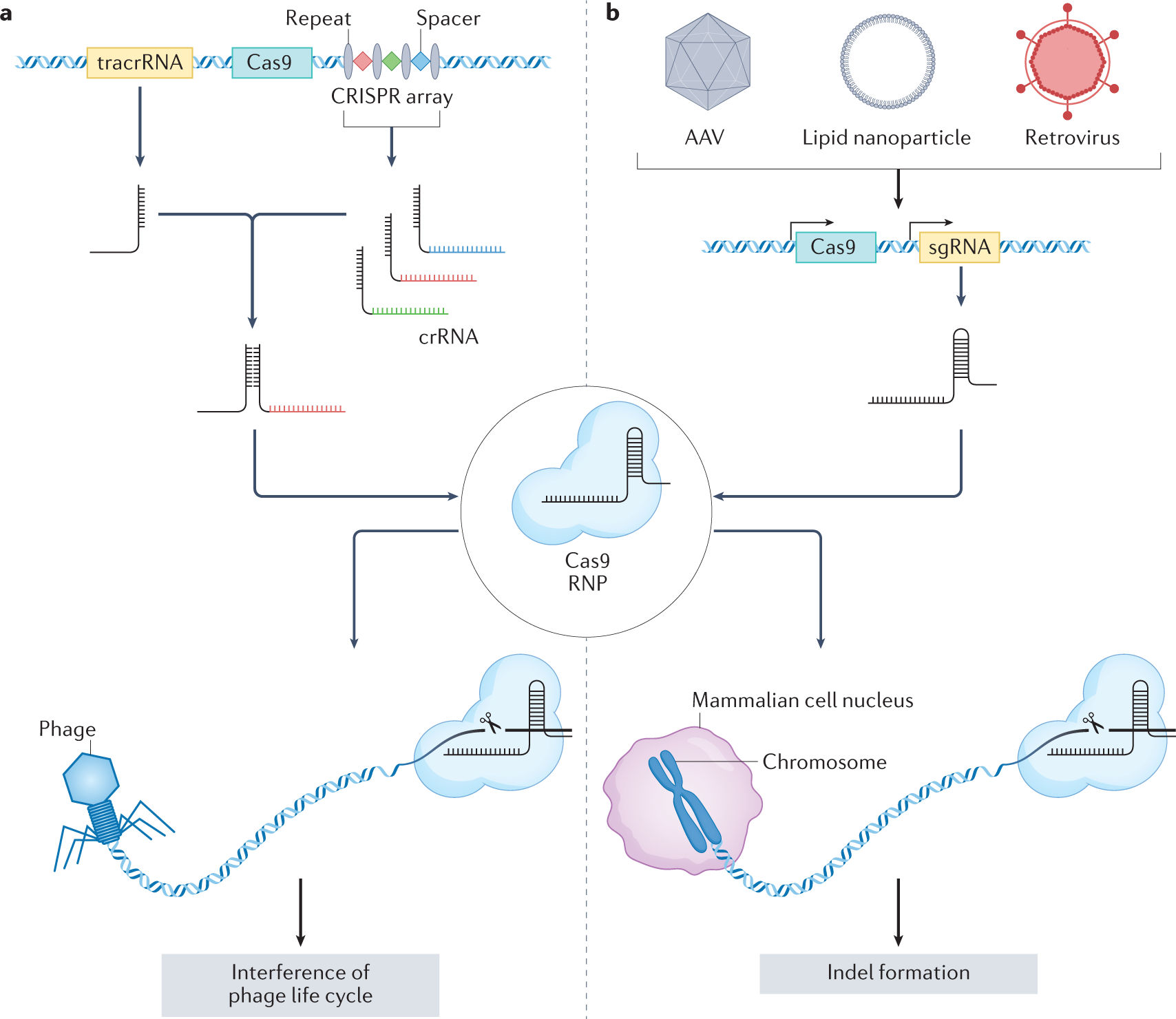

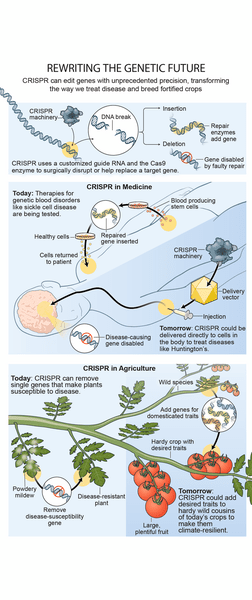

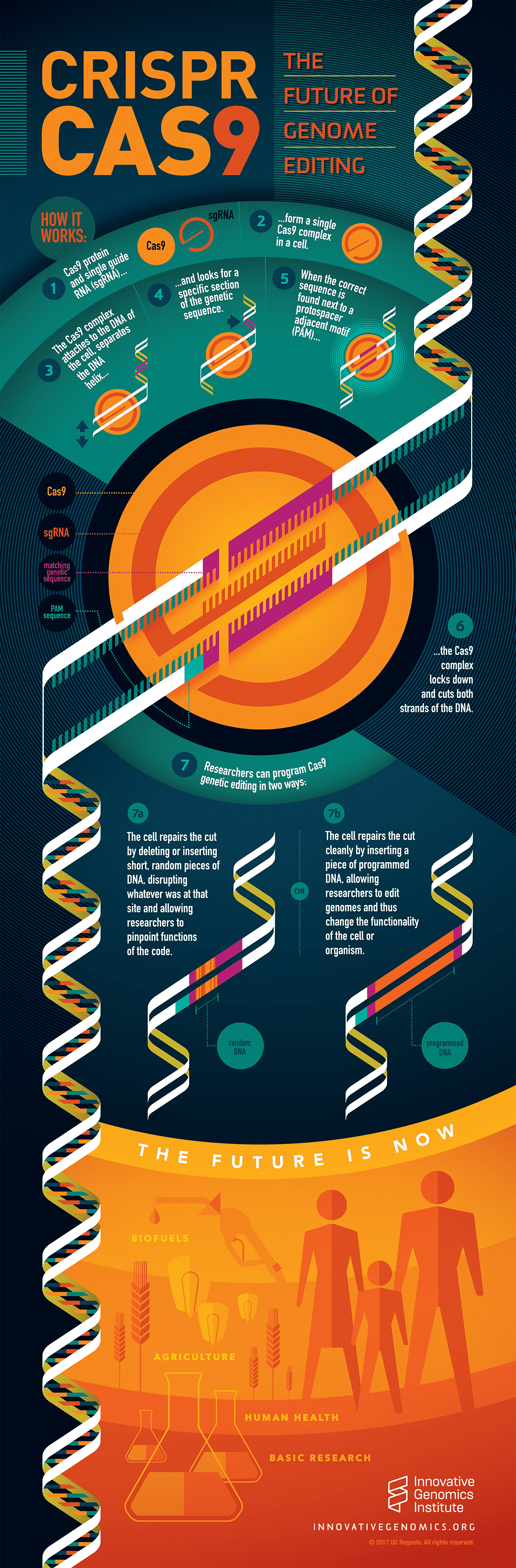

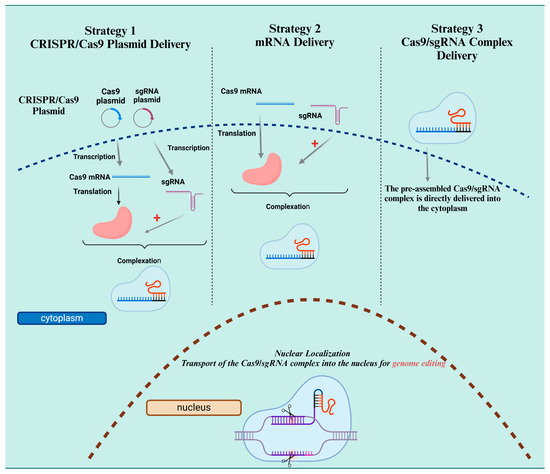

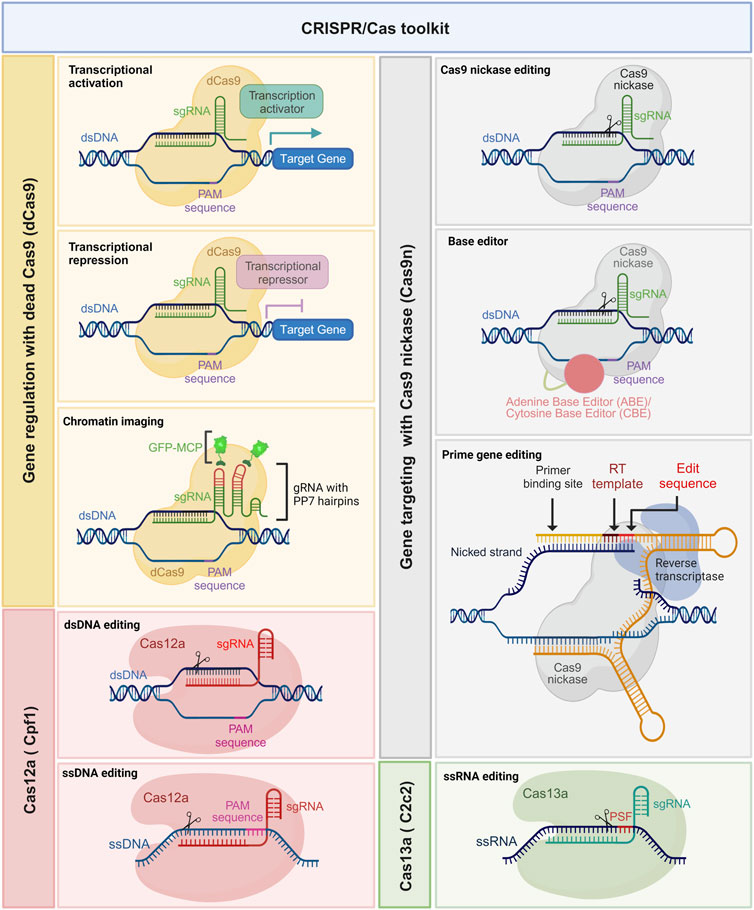

Understanding the CRISPR Distinction: Cas 9 vs. Cas 13

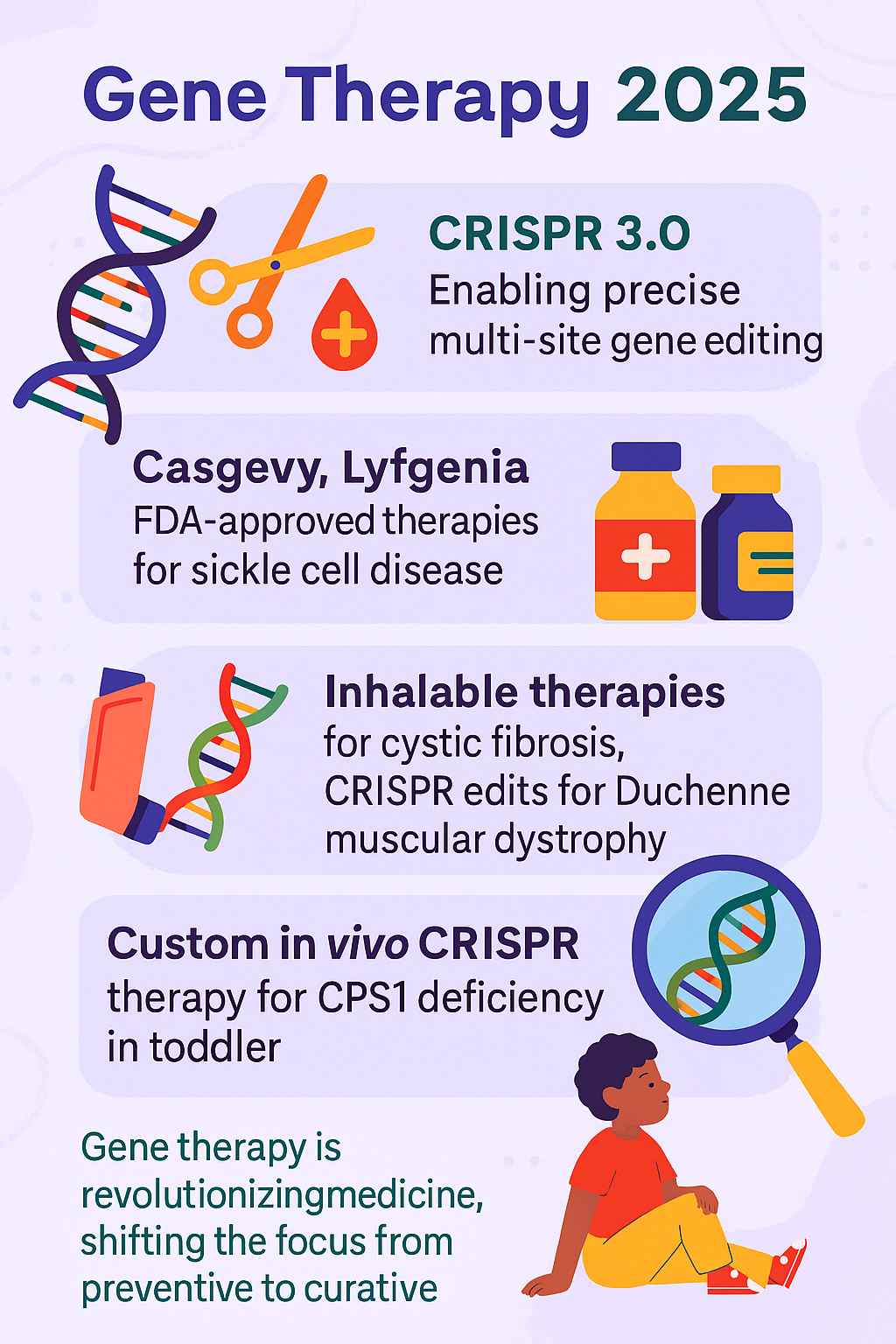

Most people have heard of CRISPR, but the version they know about—CRISPR-Cas 9—is only half the story. When the media talks about using CRISPR to cure genetic diseases, they're usually talking about Cas 9. This enzyme cuts DNA, the double-stranded genetic code in human cells. It's revolutionary for treating inherited conditions like sickle cell disease or hemophilia, where you need to fix or silence a faulty gene in your own cells.

But viruses don't play by the same rules. Influenza viruses have a completely different genetic structure. They don't carry DNA at all. Their entire genetic instruction set is made of RNA—a single-stranded cousin of DNA. This creates a problem for Cas 9: it's built to edit DNA, not RNA. It's like trying to edit a document written in a different language with a spell-checker designed for English.

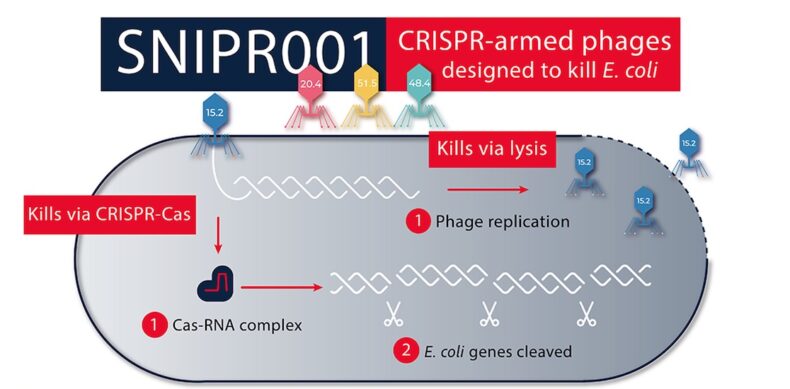

Enter Cas 13. This enzyme evolved in bacteria and archaea specifically to target RNA. Nature designed it as a defense mechanism against invading RNA viruses called phages. Bacteria use Cas 13 to slice up viral RNA before the virus can replicate. It's a genetic immune system that's been refined over millions of years of evolutionary warfare.

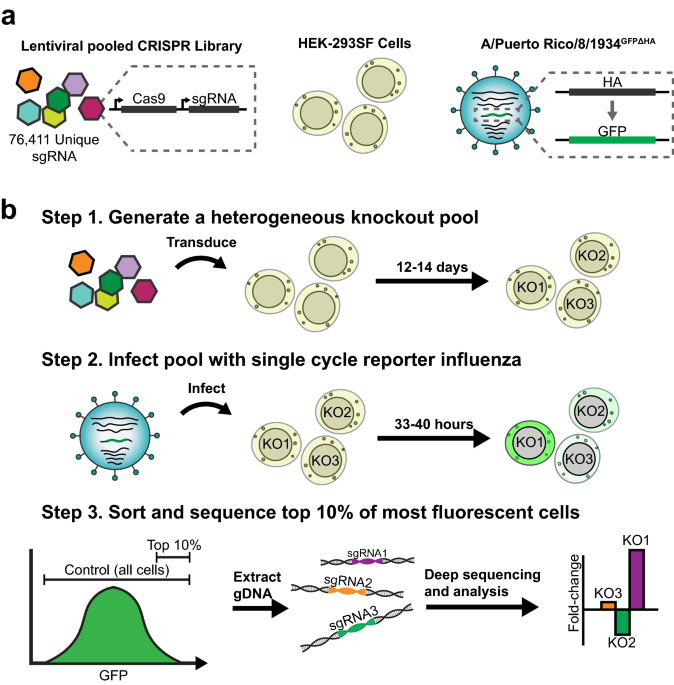

When Wei Zhao and his colleagues at the Peter Doherty Institute realized that human cells could be taught to produce Cas 13, the possibilities clicked into place. You could essentially give human cells the same bacterial defense system that's been protecting single-celled organisms since the dawn of microbiology.

The technical difference matters because RNA is more vulnerable than DNA. RNA molecules are chemically less stable—they break down more easily, and they're simpler in structure. Once Cas 13 identifies and cuts the RNA, the virus can't repair it. The viral RNA fragments are degraded, and the virus dies. It's quick, clean, and efficient.

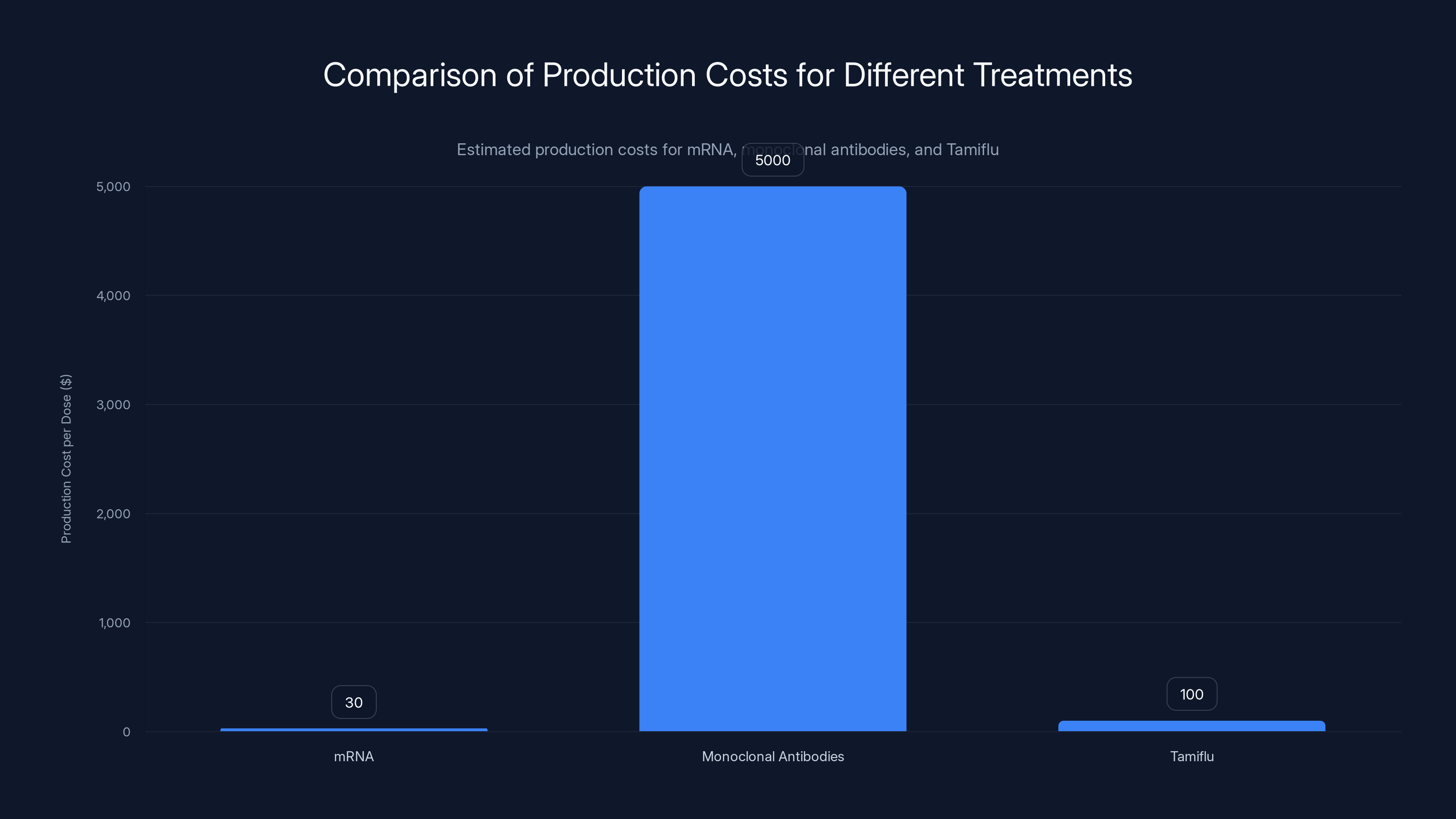

Estimated data: mRNA treatments are significantly cheaper to produce than monoclonal antibodies and Tamiflu, potentially enhancing global accessibility.

How the Two-Stage CRISPR-Cas 13 System Actually Works

Here's where it gets clever. You can't just inject Cas 13 protein directly into cells. The protein would be immediately attacked by the immune system or broken down in the bloodstream. Instead, researchers use a two-molecule delivery system that mirrors the logic of mRNA vaccines.

The first molecule is mRNA that codes for Cas 13. When this mRNA enters a cell, the cell's own machinery reads it and manufactures Cas 13 protein. Now the cell is armed. It's producing the antiviral enzyme directly, from instructions delivered from the outside.

The second molecule is a guide RNA. Think of this as a bloodhound. It's programmed with the genetic sequence of influenza RNA—specifically the parts that don't change between strains. The guide RNA leads Cas 13 to the right target, like a GPS coordinate embedded in the virus's genome.

There's a reason this targeting matters so much. Most flu antivirals target variable regions of the virus—the parts that mutate rapidly. This is why resistance develops. The flu virus tweaks these regions, and suddenly the drug doesn't recognize the target anymore. It's like changing the lock when the key no longer fits.

But researchers can engineer Cas 13 to target conserved regions instead. These are genetic sequences that can't change without breaking the virus's ability to replicate. Modify these regions, and the virus dies. It's not a matter of luck or prediction—it's targeting structural requirements that can't be mutated away without destroying the virus itself.

Both molecules get packaged into lipid nanoparticles. These are tiny fat-based spheres that can cross cell membranes and deliver their cargo inside. This is the same technology used in mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, so we already have a proven delivery framework.

The proposed delivery method is either a nasal spray or an injection. A nasal spray makes sense because influenza replicates in cells lining the respiratory tract. You'd be delivering the antiviral machinery directly to the infection site. An injection would work for serious cases where the virus has spread throughout the lungs or bloodstream.

Once inside the cell, the sequence unfolds: mRNA gets translated into Cas 13 protein. Guide RNA enters the nucleus. Cas 13 encounters the viral RNA, recognizes the conserved target sequence, and cuts it. The viral RNA is degraded. Replication stops. The infection ends.

From concept to execution, it's elegant. From complexity to practicality, it's manageable using technology we already understand.

Why Conserved Regions Are the Achilles Heel of Influenza

Influenza viruses are masters of disguise. They evolve at a rate 100 times faster than most organisms. Every year, they mutate enough that people who've had the flu once can catch it again. This is why you need a new flu vaccine almost annually.

But the virus can't mutate everything. There are certain stretches of genetic code that are absolutely essential to survival. These are the conserved regions. They code for proteins that directly enable the virus to enter cells, replicate its genome, or assemble new viral particles. If these regions change, the entire viral machine falls apart.

It's a catch-22 for the virus. Mutate the variable regions freely and dodge the immune system. But don't touch the conserved regions, or lose the ability to replicate. This is where CRISPR-Cas 13 creates a genuine strategic advantage. You're not attacking the decoys—you're targeting the foundation.

Historically, influenza researchers have known about these conserved regions. Monoclonal antibodies, another next-generation flu treatment in development, also targets these regions. But antibodies work by binding to viral proteins on the outside of cells. They're effective at blocking infection, but they don't prevent the virus from mutating.

Cas 13 works at the genetic level. It doesn't just block the virus—it cuts its RNA to pieces. Even if the virus mutates everything else, as long as the conserved regions exist (and they must, for the virus to function), Cas 13 will find them and destroy them.

The research team identified multiple conserved regions across different flu strains. H1N1 from the 2009 swine flu pandemic? Cas 13 could target it. H3N2, which causes severe seasonal outbreaks? Same enzyme works. H5N1 bird flu, which has recently been detected in humans? The conserved regions are identical. Hypothetically, Cas 13 designed for one region could work against multiple variants, multiple strains, multiple subtypes.

This is the real innovation. It's not just an antiviral. It's the first pan-flu antiviral that works on genetic principles that can't be evaded through standard mutation.

Influenza-related deaths in the U.S. vary widely, from 12,000 in mild seasons to 52,000 in severe ones. Estimated data based on historical trends.

The Lung-on-a-Chip: Testing CRISPR-Cas 13 in Human Tissue

Before you test something in humans, you need a relevant model system. You can't just use cell cultures—they're too artificial. You need something that mimics how the lungs actually work, with real tissue architecture and cellular interactions.

This is where the lung-on-a-chip comes in. Researchers at Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering created a microfluidic device lined with human lung cells and blood vessel cells. It sounds like science fiction, but it's actually an elegant piece of engineering. The device is roughly the size of a AAA battery. Inside are tiny channels separated by a porous membrane, with lung cells on one side and blood vessel cells on the other. Air flows across one side. Fluid flows across the other. It mimics the actual gas exchange that happens in your lungs.

When influenza infects real lungs, it specifically attacks cells lining the alveoli—the tiny air sacs where oxygen enters the bloodstream. This is why severe flu causes pneumonia. The virus destroys these cells, and fluid accumulates in the lungs.

When researchers infected the lung-on-a-chip with various flu strains and then introduced the CRISPR-Cas 13 system, they observed something remarkable. The virus replicated normally in untreated cells. In cells producing Cas 13, viral replication was suppressed significantly. The guide RNA successfully directed Cas 13 to the viral RNA. The cuts happened. The virus died.

But the really important finding was what didn't happen. Researchers were concerned about off-target effects—the possibility that Cas 13 might cut human RNA as well as viral RNA, causing cellular damage. They ran extensive tests. The cells remained healthy. Inflammation decreased. There was no collateral damage to the human cells themselves.

According to Donald Ingber, the founding director of the Wyss Institute and a pioneer of lung-on-a-chip technology, the results were surprisingly clean. "We didn't see any off-target effects, which was amazing," he noted. "We suppressed viral replication, but also the molecules that mediate inflammation which are secreted when your tissues are infected."

This is actually better than just stopping the virus. Severe flu kills not through direct viral destruction of lung tissue, but through the immune system's inflammatory response. Your body recognizes the infection and launches an attack, releasing inflammatory molecules that damage tissue. If CRISPR-Cas 13 reduces both viral replication and the inflammation response, you're addressing both mechanisms of disease.

The lung-on-a-chip isn't perfect. It's a model, not a human. But it's light-years ahead of petri dishes for understanding how a treatment will behave in actual tissue.

The Delivery Challenge: Getting Cas 13 Deep into the Lungs

Here's where theory meets reality, and reality pushes back. Designing a treatment in the lab and delivering it where it needs to go are completely different problems.

Influenza lives deep in the lungs, specifically in alveolar cells. These aren't on the surface—they're at the far end of the respiratory tract. Getting a molecule into those cells requires navigating multiple barriers.

A nasal spray is convenient, but getting lipid nanoparticles from the nasal mucosa down to the alveoli is mechanistically challenging. The nanoparticles need to be small enough to penetrate deeply but stable enough to survive the journey. They need to cross multiple cell layers. They need to avoid getting caught in mucus or attacked by immune cells in the upper respiratory tract.

Intramuscular injection bypasses some of these problems—you're getting the molecules into the bloodstream where they can circulate throughout the body. But now you have a different problem: the nanoparticles need to cross the barrier between blood and lungs, and then specifically target the right cells.

Nicholas Heaton, a professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University, raises legitimate concerns. "Figuring out a way to deliver a lipid nanoparticle containing the instructions to make Cas 13 directly to alveoli cells deep within the lungs is no easy task," he notes. It's one thing to prove it works in a controlled lab setting. It's another to make it work reliably in real humans.

There are potential solutions. Researchers could engineer the nanoparticles with specific proteins on their surface that help them target lung cells. You could modify the nanoparticles to be smaller or larger depending on whether you're going nasal or systemic. You could time the delivery to match the natural immune response or the viral replication cycle.

But these aren't solved problems yet. They're engineering challenges that need solutions. And solving them takes time, money, and iterative testing.

mRNA vaccine technology has actually paved a useful path here. Lipid nanoparticle delivery is proven safe in humans at scale—billions of people have received mRNA vaccines using this exact delivery method. But mRNA vaccines are targeting the immune system broadly, not specific cells deep in the lungs. The problem is adjacent but not identical.

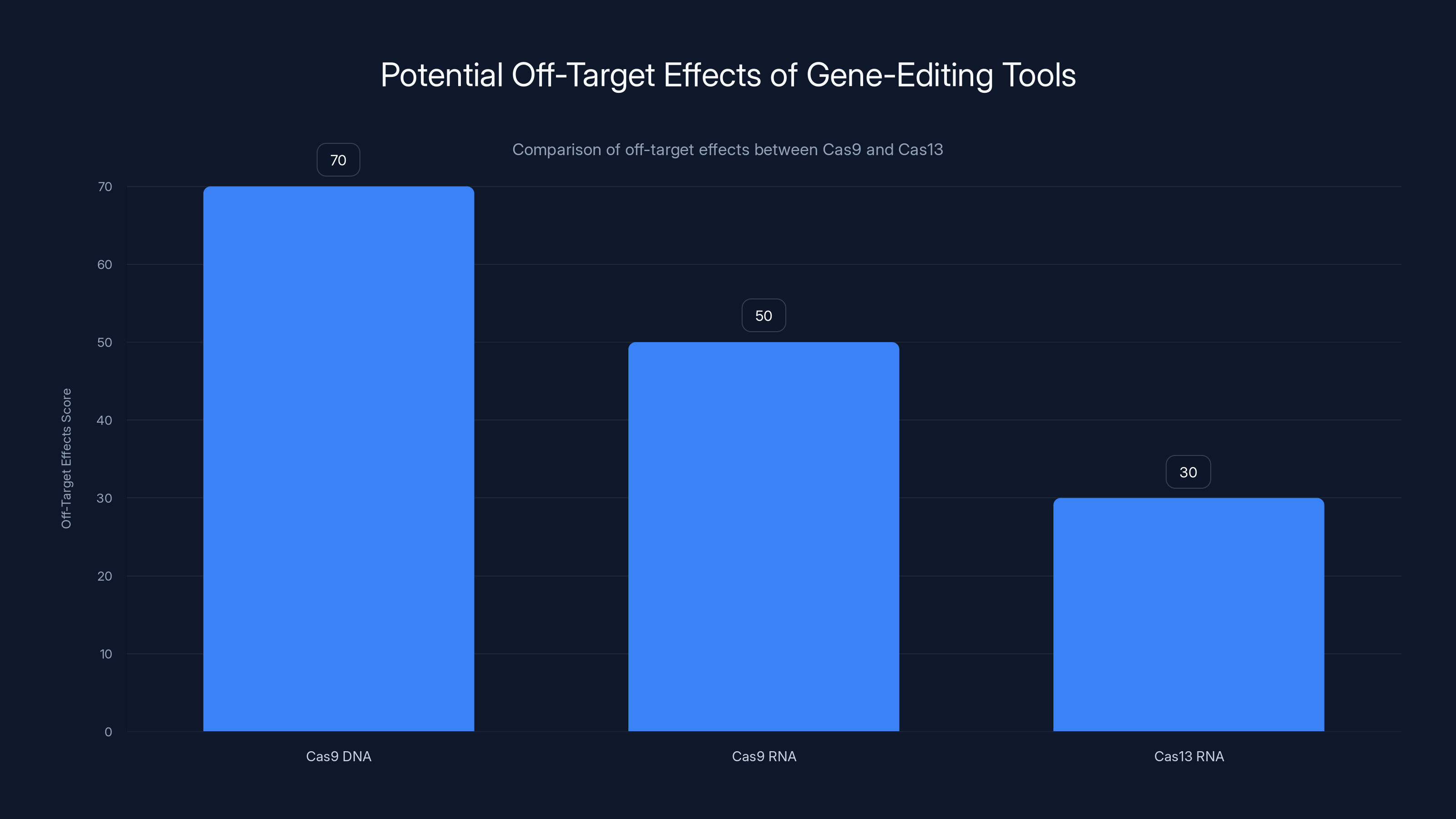

Cas9 shows higher off-target effects on DNA compared to RNA. Cas13, targeting RNA, has lower off-target effects, making it potentially safer for RNA editing. Estimated data based on typical findings.

The Immune Response Question: Bacteria Aren't Welcome in Your Body

Here's the uncomfortable truth: Cas 13 is a bacterial protein. Your immune system evolved to recognize bacteria as invaders and attack them. If you introduce a bacterial protein into the human body, there's a real risk that the immune system will treat it as a threat and mount a response against it.

This is called immunogenicity. It's a major concern for any treatment using proteins sourced from bacteria. Your immune system might attack the Cas 13 protein itself, rendering it ineffective. Or it might trigger inflammation that causes side effects.

Heaton highlights this directly: "I like the idea of it, but it's putting a foreign protein from a bacteria into someone's body. So will the body make an immune response against it?"

It's a fair question with no obvious answer yet. mRNA vaccines avoid this problem somewhat—the body makes the spike protein itself, rather than you injecting the protein directly. With CRISPR-Cas 13, you're instructing cells to make the protein, which is similar. But the guide RNA is completely foreign, and if there's any leakage of Cas 13 outside the targeted cells, the immune system will see it.

Some possible solutions exist. You could pre-treat with immune-suppressing medications. You could modify the Cas 13 protein to be less recognizable as bacterial. You could design the treatment for short-term use during acute infection, minimizing the time the immune system has to respond. You could engineer the guide RNA to be less immunogenic.

But these are all potential solutions, not proven ones. The research needed to demonstrate safety here is substantial. It's not a showstopper—plenty of treatments use bacterial proteins or engineered versions thereof—but it's a real obstacle.

In the mRNA vaccine trials, immunogenicity existed but was generally manageable. The question is whether Cas 13-based treatments will follow a similar pattern. Early data is encouraging, but early data is always less comprehensive than full clinical trial data.

Off-Target Effects: The Risk That Cuts More Than Just Viral RNA

When Cas 13 enters a cell, it carries the guide RNA with it. The guide RNA is supposed to direct Cas 13 specifically to the influenza viral RNA sequences. But what if the guide RNA's target sequence appears elsewhere? What if it appears in the human genome?

Off-target effects occur when a gene-editing tool cuts DNA or RNA it wasn't supposed to cut. With Cas 9, this has been extensively studied. Cas 9 occasionally cuts sites that share some similarity with the intended target. This can cause unintended mutations in human genes, which could theoretically cause problems.

With Cas 13 and RNA targets, the problem is somewhat different. RNA molecules turn over much faster than DNA. A mistake in RNA editing is temporary and localized—the damaged RNA gets degraded and replaced. But if Cas 13 accidentally cuts human messenger RNA that's essential for cell survival, even temporarily, that cell could die.

The lung-on-a-chip studies suggested this isn't happening. The research team didn't detect off-target cuts to human RNA. Cells remained healthy. Inflammation actually decreased. This is genuinely encouraging.

But the lung-on-a-chip is a simplified system. It's not a whole organism with billions of cells and complex organ interactions. There's always the possibility that off-target effects emerge at scales or in cell types not represented in the model.

To address this, researchers can engineer more specific guide RNAs. They can include multiple guide RNAs targeting different conserved regions, reducing the chance that an imperfect match leads to viral survival. They can design the system to be self-limiting—active only in infected cells, with a built-in off switch after the virus is cleared.

Safety testing in animals comes next, followed by small human trials where researchers carefully monitor for any signs of off-target cutting. It's methodical, but it's necessary.

The reassuring part: Cas 9 and Cas 13 have already been used in clinical trials for genetic diseases. If major off-target problems existed, they would have shown up by now. The fact that we're using these enzymes therapeutically without widespread reports of damage suggests the risk is manageable.

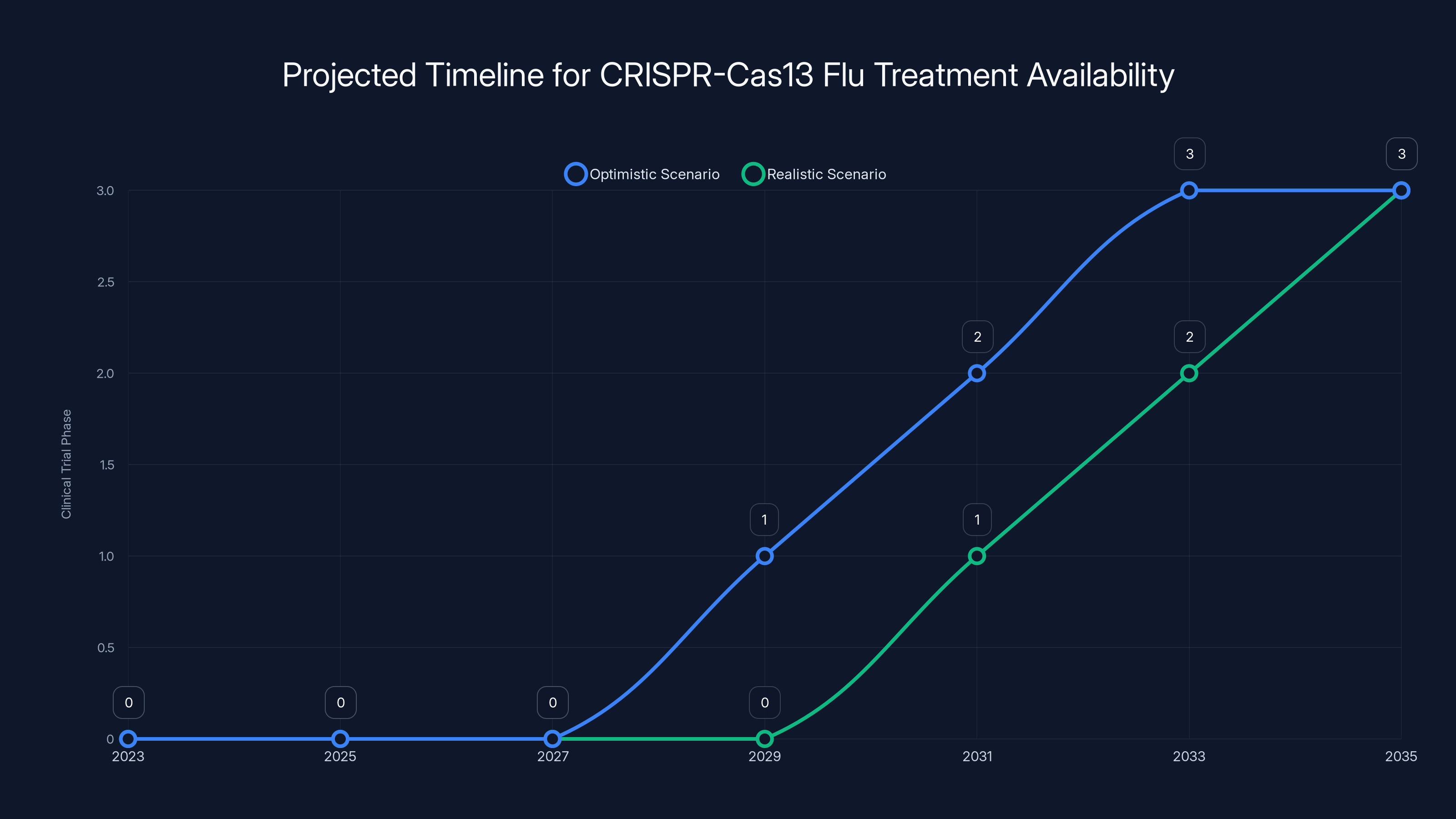

The CRISPR-Cas13 flu treatment could optimistically be available by 2030-2032, but more realistically by 2033-2035, considering typical clinical trial durations and regulatory processes. Estimated data.

The Resistance Question: Can Influenza Evolve Around CRISPR-Cas 13?

Here's the deepest concern, and it's one that even the researchers admit they're still thinking through. Tamiflu was revolutionary when it came out. It targeted a specific viral protein, preventing the virus from leaving infected cells. Within a few years, resistant strains emerged. The virus mutated the target protein just enough to avoid Tamiflu while maintaining function.

Could the same happen with CRISPR-Cas 13?

The argument for resistance developing is straightforward: if you apply selective pressure on a rapidly mutating virus, you'll eventually get resistant variants. Cas 13 creates that selective pressure by targeting certain conserved regions. Even though these regions are essential, couldn't the virus find alternative mutations that preserve function?

The argument against resistance is equally compelling: the whole point of targeting conserved regions is that they can't mutate freely without losing essential function. The viral proteins encoded by these regions have specific three-dimensional shapes. They fit into other proteins like a key in a lock. Mutate them, and the key no longer fits. The virus dies.

But viruses are incredibly creative. They might find compensatory mutations elsewhere that allow the conserved region to function differently. They might develop mechanisms to chop up the guide RNA before Cas 13 uses it. They might evolve to produce less essential protein, requiring fewer viral particles to achieve infection.

Nicholas Heaton points out this concern directly: "Any antiviral that targets a virus directly may help encourage the pathogen to further mutate, even if it is targeting seemingly integral parts of its genetic code."

It's a fair warning. This isn't a unique problem for CRISPR-Cas 13, but it's worth taking seriously. The answer likely involves using CRISPR-Cas 13 as part of a cocktail, much like HIV treatments use multiple antivirals simultaneously. Hit the virus from multiple angles. Even if it develops resistance to one, the others keep working.

Alternatively, limit use to acute treatment or seasonal prevention, so the virus isn't under constant selection pressure. Or combine with vaccines, which work through a completely different mechanism. A vaccinated person's immune system recognizes infected cells and kills them, whereas Cas 13 kills virus directly. Together, they're much harder for the virus to evade.

The resistance question won't be fully answered until the treatment is in use. But the fact that it's being asked seriously by researchers suggests they're not overlooking the risk.

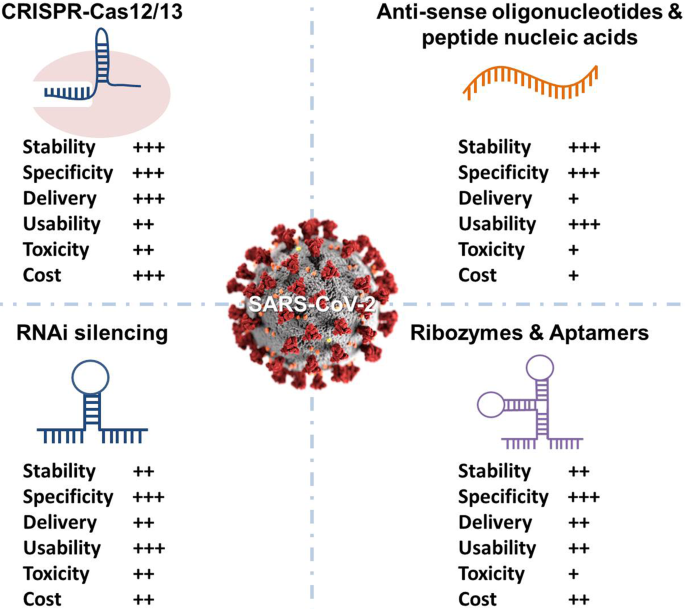

How This Compares to Other Next-Generation Flu Treatments

CRISPR-Cas 13 isn't the only next-generation approach in development. Understanding how it compares to alternatives clarifies its real advantages and limitations.

Monoclonal antibodies represent one major alternative. These are lab-designed proteins that bind to specific parts of the flu virus, preventing it from infecting cells. The key advantage: they're already well-understood. Monoclonal antibodies have been used therapeutically for decades. Manufacturing is established. Safety profiles are clear.

The disadvantage: they're still targeting proteins on the virus surface, which means the virus can mutate to avoid them. They're also proteins, so they face similar immunogenicity concerns as Cas 13. They need to be administered by injection or infusion, which requires medical infrastructure. They cost more to produce than mRNA-based treatments.

Interferon inducers are another approach. These drugs boost your body's natural antiviral response by ramping up interferon production—the signaling molecules that tell immune cells an infection is happening. In theory, this is elegant: you're not directly attacking the virus; you're putting your immune system on high alert.

The problem: if interferons are so good at stopping viruses, why don't they stop the flu normally? Influenza has evolved specific mechanisms to suppress interferon. Interferon inducers might work in some cases, but the virus can adapt. Plus, too much interferon causes inflammation and tissue damage.

Direct-acting antivirals like Tamiflu or the newer baloxavir marboxil target specific viral proteins. They work fast and effectively, but resistance develops predictably. They're the old guard of flu treatment.

CRISPR-Cas 13 occupies unique territory. It's mRNA-based, like vaccines, so it's cheap to manufacture and delivery technology is proven. It's genetic, so it's potentially harder for the virus to escape through simple mutation. It's RNA-targeting, so it works on the virus's most fundamental replication machinery.

But it's also more novel, which means less long-term safety data. It requires delivery to specific cells deep in the lungs. It involves a bacterial protein, creating immunogenicity concerns. It has the theoretical resistance question hanging over it.

The most realistic scenario is that CRISPR-Cas 13 isn't a replacement for vaccines and existing antivirals. It's a complementary tool. Use it for severe infections where traditional antivirals have failed or resistance exists. Use it as a preventive during high-risk situations. Use it in combination with other treatments to reduce resistance risk. Use it as a backup when the flu mutates beyond current vaccine coverage.

It's a sophisticated toolbox approach, not a silver bullet.

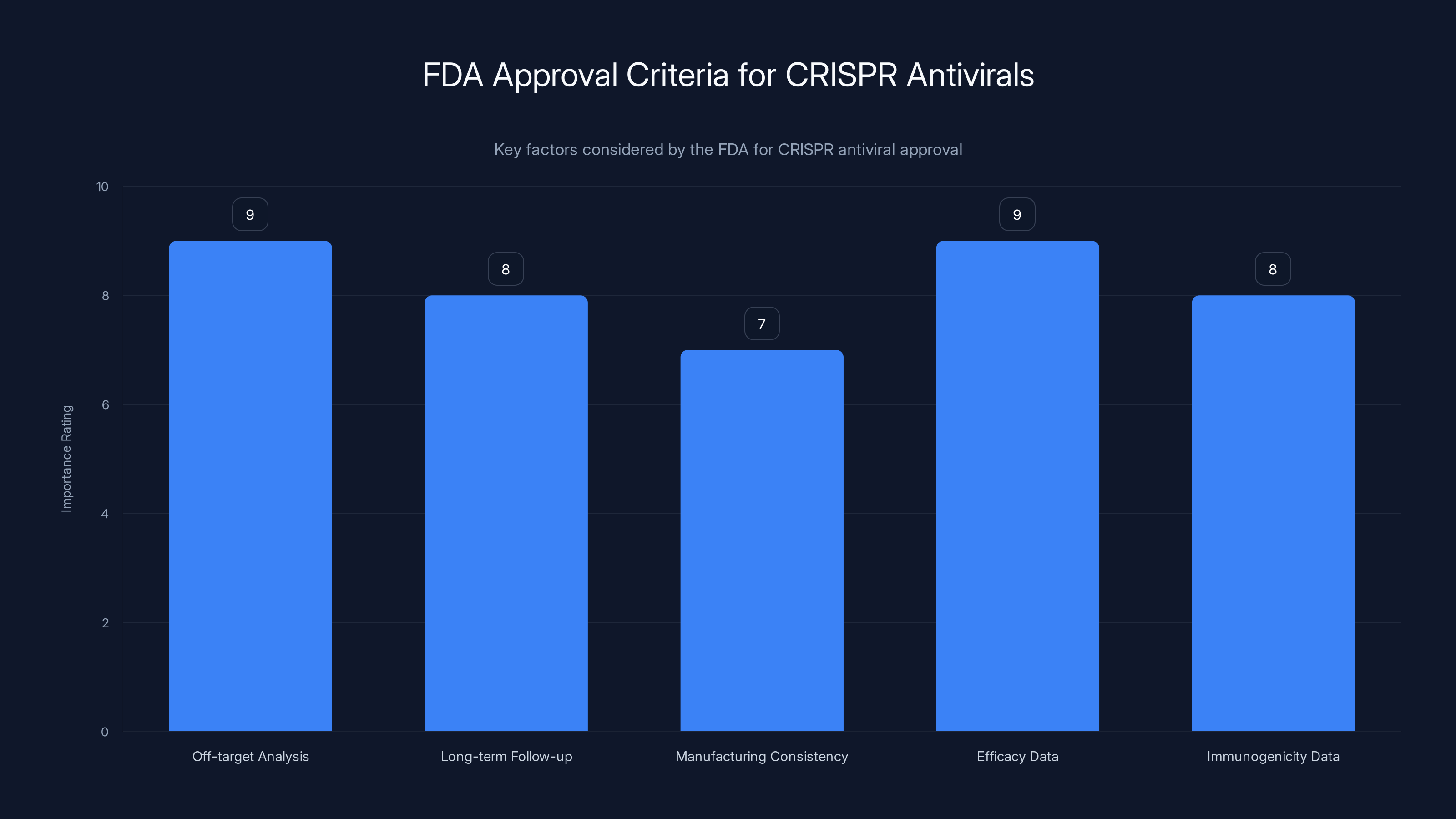

The FDA's approval process for CRISPR antivirals emphasizes comprehensive off-target analysis and efficacy data, both rated highest in importance. Estimated data.

Tropical Viruses and Beyond: Could This Work for More Than Just Flu?

Influenza is the initial target, but researchers are already thinking bigger. Dengue fever, Zika, West Nile virus—these are all RNA viruses. They replicate through similar mechanisms. Many of them have conserved regions that are just as essential as influenza's.

Theoretically, Cas 13 could be adapted for any RNA virus. The specific guide RNA would change—instead of targeting influenza conserved regions, you'd target dengue conserved regions. But the fundamental mechanism would be identical.

Dengue is particularly interesting because it's a massive global health problem. Around 400 million dengue infections occur annually. There's no specific antiviral. Vaccines are available but don't work for all dengue strains. A Cas 13-based dengue treatment could be transformative.

Zika was a pandemic threat not long ago. Measles, mumps, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)—these are all potential targets. Even COVID-19, if novel coronavirus variants continue emerging beyond vaccine coverage, could theoretically be addressed with a CRISPR-Cas 13 approach.

The implication is massive. We could move away from designing new drugs for each virus and instead toward a platform approach: identify conserved regions, design guide RNAs, and deploy the same Cas 13 protein system against multiple targets.

But this is future thinking. The research is currently focused on influenza because it's a well-characterized virus with clear public health need. Success here provides the template for everything else.

Timeline: When Could This Actually Be Available?

Let's be realistic about the timeline. The lung-on-a-chip work is proof of concept. It's compelling, but it's not a human clinical trial.

The next steps: animal studies in mice, then larger animals like ferrets or primates. These will establish basic safety and efficacy. You need to show the treatment works in a living organism, not just in a tissue model. You need to observe for long-term effects. You need to establish doses.

Animal studies typically take 12 to 24 months. Then comes the IND (Investigational New Drug) application to regulatory agencies like the FDA. More papers. More data. More justification.

Assuming all that goes well, you get to Phase 1 human trials: small groups of healthy people to establish safety. Phase 2: larger groups of sick people to establish efficacy. Phase 3: even larger groups to confirm benefits and monitor for rare side effects.

Each phase typically takes 1 to 2 years. So Phase 1 to 3 spans roughly 3 to 6 years minimum.

Optimistically, if everything goes perfectly and there are no unexpected safety issues, a CRISPR-Cas 13 flu treatment could reach patients around 2030 to 2032. More realistically, accounting for bureaucratic delays and complications that always emerge, 2033 to 2035 is a better estimate.

That might sound distant, but it's actually aggressive for a novel treatment platform. Some researchers are pushing for expedited pathways since flu is a known public health threat, which could accelerate timelines.

The good news: the research is real, funded, and progressing. It's not speculative. Peter Doherty Institute is a legitimate research institution. Harvard's Wyss Institute is producing real data. This will happen. The question is how quickly.

The Economic Argument: Cost and Production

CRISPR-Cas 13 treatments would be mRNA-based, which carries enormous economic implications. mRNA is cheap to make once you have the sequence. The manufacturing process is standardized. You don't need living cells or complex fermentation like some biologics. It's basically chemistry.

Compare this to monoclonal antibodies, which require cell culture and purification. Or to Tamiflu, which requires chemical synthesis with complex supply chains. mRNA production scales easily and costs relatively little once the initial infrastructure is in place.

For influenza, this matters enormously. The flu vaccine is mass-produced because it's needed globally, in massive quantities, cheaply. If CRISPR-Cas 13 antivirals can be produced at similar scales and costs, they could be accessible globally, not just in wealthy countries.

The mRNA vaccine rollout demonstrated this. Companies ramped up production from zero to billions of doses in under a year. That same manufacturing infrastructure could be adapted for therapeutic mRNA.

The pricing will be interesting to watch. mRNA vaccines are relatively affordable—

Given that influenza is a public health threat, not a rare disease, the economics should drive toward accessibility. But that's not guaranteed.

Practical Prevention: Using CRISPR-Cas 13 Defensively

Most of the research focuses on treating acute flu infections. But there's a secondary application that might be even more important: prevention.

Wei Zhao mentioned this possibility directly: the nasal spray could be used prophylactically during peak flu season or during predicted outbreaks. You'd apply it before infection, and it would prepare respiratory cells to produce Cas 13. When virus inevitably encountered those primed cells, it would be neutralized.

This is like vaccinating against a genetic level instead of an immune level. Your cells are pre-armed with the molecular defense system. If the virus enters, it's destroyed before it replicates significantly.

The advantage over vaccination: no dependence on predicting which strains will circulate. The advantage over prophylactic antivirals like oseltamivir: no systemic side effects and no development of resistance through long-term use.

The timing matters. You'd probably apply the preventive spray weekly during flu season—short and simple. It would be perfect for healthcare workers, elderly populations, immunocompromised patients, or anyone at high risk.

Practically, this makes CRISPR-Cas 13 a dual-use tool: treatment for active infections and prevention during high-risk periods. That versatility increases its value tremendously.

The Regulatory Pathway: Does the FDA Know How to Approve This?

CRISPR therapies are already moving through the FDA approval process for genetic diseases. In 2023 and 2024, the first in vivo CRISPR treatments are expected to receive approval. This means the FDA has experience reviewing CRISPR mechanisms, delivery methods, and safety profiles.

But CRISPR antivirals are different from CRISPR gene therapies. Gene therapies are typically one-time treatments for genetic diseases. Antivirals are for acute infections, potentially repeated across populations. The safety bar is different. The benefit-risk calculation is different.

The FDA will likely require:

- Comprehensive off-target analysis showing Cas 13 doesn't cut human RNA inadvertently

- Long-term follow-up data on treated patients, watching for delayed side effects

- Manufacturing consistency data proving the treatment is reliably produced

- Efficacy data from clinical trials showing the treatment actually cures flu faster than standard care

- Immunogenicity data addressing concerns about immune response against bacterial proteins

None of this is insurmountable. It's all precedented in other antiviral approvals. But it's thorough and necessary.

One advantage: CRISPR has public familiarity now. The FDA won't be explaining an alien concept to regulators or the public. CRISPR gene editing has been in the news for years. The safety profile is becoming clearer. This might actually accelerate approval, despite the novelty.

The Research Momentum: Funding and Institutional Commitment

What makes this really credible is the institutions involved. The Peter Doherty Institute is Australia's premier infectious disease research center. Harvard's Wyss Institute is one of the world's leading biomimetic engineering institutes. These aren't fringe researchers. They're mainstream, well-funded, institutionally supported.

The Pandemic Research Alliance Symposium where Wei Zhao first presented this work was attended by virologists from multiple countries. There's international interest and momentum. Researchers are sharing data and collaborating.

This is the opposite of a speculative technology. It's real science with real results being built on real infrastructure.

Funding is the ultimate test of institutional commitment. If major funding bodies—government grants, venture capital, pharmaceutical companies—commit resources, it signals that the science is real and the timeline is achievable. The fact that this research is happening suggests funding exists.

The Ethical Landscape: Why This Matters Beyond Medicine

CRISPR-Cas 13 as a therapeutic tool raises interesting ethical questions. It's not gene editing in the germline sense—we're not modifying the human genome permanently. We're temporarily giving cells an antiviral tool. The modified cells eventually die and are replaced with normal cells. It's temporary, reversible, and therapeutic.

But it does involve a bacterial gene-editing system in human cells. Some people have philosophical concerns about introducing non-human biological machinery into bodies. That's a valid perspective worth discussing, even if it's not a scientific barrier.

There's also the question of access and equity. If CRISPR-Cas 13 antivirals are expensive, wealthy populations get them first. Disadvantaged populations get them later, if at all. That's not unique to CRISPR—it's true for all new medicines—but it's worth acknowledging.

The most optimistic scenario: mRNA-based antivirals are cheap enough to produce and distribute globally. During future pandemics, every country could have access to CRISPR-Cas 13 treatment. That would be genuinely transformative for global health equity.

The Bottom Line: A Realistic Assessment

CRISPR-Cas 13 for influenza is genuinely innovative. The mechanism is sound. The early data is encouraging. The timeline is feasible. The economic case is compelling.

But it's not a miracle cure. It's not going to eliminate the flu overnight. It's not going to prevent seasonal outbreaks without combination strategies. It's not going to be available for several years.

What it will be: another tool in the antiviral toolkit. A complementary approach that addresses limitations of existing treatments. A platform technology that could be adapted for other RNA viruses. A sophisticated example of how modern molecular biology can solve old problems.

Influenza has killed 12,000 to 52,000 Americans every year for decades. Vaccines help but aren't perfect. Antivirals exist but resistance develops. The need for better options is clear and ongoing.

CRISPR-Cas 13 is not the solution to everything. But it's a solution to something important. And right now, with the research progressing, it looks like it might actually work.

FAQ

What is CRISPR-Cas 13?

CRISPR-Cas 13 is a gene-editing enzyme derived from bacteria that targets and cuts RNA molecules instead of DNA. Unlike the more famous CRISPR-Cas 9, which is used for editing genetic code in inherited diseases, Cas 13 is specifically designed to target viral RNA, making it potentially effective against RNA viruses like influenza, dengue, and COVID-19. The enzyme works by following a guide RNA to a specific RNA sequence, then making precise cuts that degrade the viral genetic material.

How does CRISPR-Cas 13 stop the flu virus?

When flu infects respiratory cells, CRISPR-Cas 13 targets conserved regions of the viral RNA—genetic sequences that all flu strains share because they're essential for viral replication. The guide RNA directs Cas 13 to these critical sequences, and Cas 13 cuts the RNA into fragments. The cell's natural degradation machinery then destroys the fragmented viral RNA, preventing the virus from replicating and stopping the infection at the genetic level.

What are the main advantages of CRISPR-Cas 13 for treating flu?

Unlike traditional antivirals that target specific proteins and allow resistance to develop, CRISPR-Cas 13 targets conserved genetic regions that can't change without destroying the virus's ability to function. This makes it theoretically effective against multiple flu strains simultaneously, from H1N1 to H3N2 to bird flu variants. Additionally, because the delivery system uses mRNA technology similar to COVID-19 vaccines, manufacturing is relatively inexpensive and scalable globally.

How is CRISPR-Cas 13 delivered to the lungs where flu replicates?

Researchers are developing two delivery methods: a nasal spray for mild to moderate infections and an injection for severe cases. Both methods use lipid nanoparticles—tiny fat-based spheres that can cross cell membranes—to deliver mRNA instructions that teach respiratory cells to produce Cas 13, along with guide RNA that directs Cas 13 to the viral target. This two-stage delivery is similar to mRNA vaccine technology, which has proven safe in billions of people.

What are the main safety concerns with CRISPR-Cas 13?

Three major concerns exist: first, Cas 13 is a bacterial protein, so the immune system might attack it (immunogenicity); second, Cas 13 might accidentally cut human RNA it wasn't supposed to (off-target effects); third, influenza might evolve resistance by mutating around the Cas 13 target, even though those regions are theoretically essential. Early lung-on-a-chip studies suggest off-target effects aren't occurring, but full human trials are needed to confirm safety.

When will CRISPR-Cas 13 treatment be available to patients?

Based on typical drug development timelines, animal studies will take 12-24 months, regulatory application another 6-12 months, and human trials (Phase 1-3) another 3-6 years. Optimistically, CRISPR-Cas 13 flu treatment could be available around 2030-2032, though 2033-2035 is a more realistic estimate accounting for regulatory delays and complications that typically emerge in novel therapies.

Could CRISPR-Cas 13 be used to treat other RNA viruses besides influenza?

Yes, theoretically CRISPR-Cas 13 could be adapted for any RNA virus with conserved regions, including dengue, Zika, West Nile virus, measles, and even novel coronavirus variants. Researchers would simply design different guide RNAs targeting each virus's conserved regions while keeping the same Cas 13 enzyme. This "platform" approach could eventually provide treatments for multiple viral diseases using the same underlying technology.

How much will CRISPR-Cas 13 treatment cost?

While pricing hasn't been finalized, mRNA-based treatments typically cost less to manufacture than monoclonal antibodies or chemical drugs. If priced similarly to mRNA vaccines (

Could resistance to CRISPR-Cas 13 develop like it does with Tamiflu?

It's a legitimate concern. While targeting conserved regions theoretically prevents simple resistance, viruses are creative and could potentially develop compensatory mutations or suppress the guide RNA. To prevent this, CRISPR-Cas 13 will likely be used in combination with other antivirals (like cocktail therapy for HIV) or with vaccines that attack the virus through different mechanisms, making it extremely difficult for resistance to emerge against both simultaneously.

How does CRISPR-Cas 13 compare to current flu treatments and next-generation options?

Traditional antivirals like Tamiflu work fast but resistance develops within seasons. Monoclonal antibodies target conserved regions but are expensive and face immunogenicity issues. Interferon inducers boost natural immunity but have limited effectiveness. CRISPR-Cas 13 combines the genetic precision of monoclonal antibodies with the manufacturing efficiency of mRNA vaccines, while avoiding resistance by targeting genetic code itself rather than just proteins. Most likely, it will complement rather than replace existing treatments.

Key Takeaways

- CRISPR-Cas 13 is a bacterial enzyme that cuts RNA, making it uniquely suited to target influenza's RNA genome

- By targeting conserved regions of viral RNA that can't mutate without destroying the virus, Cas 13 creates a pan-influenza treatment effective against multiple strains simultaneously

- Early lung-on-chip studies demonstrate the technology eliminates multiple flu strains without damaging human cells

- Delivery uses mRNA technology proven safe in billions of people, enabling scalable, affordable manufacturing

- Key challenges remain: immune response to bacterial proteins, delivery to deep lung cells, and potential for viral mutation

- Clinical availability estimated at 2030-2035, making it a genuine near-term innovation, not distant future technology

- Success with influenza could enable CRISPR-Cas 13 treatments for dengue, Zika, and other RNA viruses globally

![CRISPR Gene Editing for Flu: The Future of Antiviral Treatment [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/crispr-gene-editing-for-flu-the-future-of-antiviral-treatmen/image-1-1767609524982.jpg)