The Cost of a Viral Moment: Understanding the TikTok Livestreaming Tragedy

It started like thousands of other TikTok livestreams. A creator holding their phone, speaking to an invisible audience, documenting their day in real-time. But this one ended with a loud thud and a question from a child: "What was that?" The answer came quickly: "I hit somebody."

This wasn't a viral moment or a trending sound. It was a tragedy that would forever change how we think about social media, attention, and the price of digital validation.

In December 2024, Zion Police charged Tynesha McCarty-Wroten, who posted to TikTok under the handle Tea Tyme, with reckless homicide and aggravated use of a communications device resulting in death. The victim was Darren Lucas, a pedestrian who was struck by her vehicle while she was actively livestreaming. Surveillance footage showed her vehicle entering an intersection while the light was red, with no indication she slowed down or attempted to avoid the collision, as reported by The Guardian.

This incident isn't an outlier. It's a symptom of a much larger crisis that's unfolding across America's roads. Every day, roughly 3,500 people die in traffic accidents, and an estimated 1 in 4 are caused by distracted driving. Yet we've normalized the behavior that causes them. We check our phones at red lights. We text while driving. We scroll while behind the wheel. And now, some of us are livestreaming.

But what makes this case different is what it reveals about the intersection of social media platforms, human psychology, and the law. It forces us to ask uncomfortable questions: How far is a platform responsible when its features enable fatal behavior? What laws are actually designed to prosecute this? And perhaps most importantly, why are we still treating distracted driving as a personal choice rather than a public health emergency?

This article explores the implications of the McCarty-Wroten case, examines the psychology behind livestreaming while driving, breaks down the legal landscape, and investigates what platforms like TikTok are—or aren't—doing to prevent this from happening again.

TL; DR

- The Incident: An Illinois driver livestreaming on TikTok struck and killed a pedestrian while driving through a red light; she's been charged with reckless homicide and aggravated use of a communications device resulting in death, as detailed by ABC7 Chicago.

- The Scale: Distracted driving kills approximately 1 in 4 traffic fatalities annually in the United States, with a growing percentage involving social media and livestreaming.

- Platform Responsibility: TikTok and similar platforms have faced criticism for not implementing sufficient safeguards to prevent livestreaming while driving, despite the obvious dangers.

- Legal Gaps: Most states lack specific laws targeting livestreaming while driving, forcing prosecutors to use older distracted driving statutes that may not adequately address the behavior.

- The Psychology: Livestreaming creates a compulsive feedback loop that makes users more likely to stay engaged and less likely to stop, even in dangerous situations.

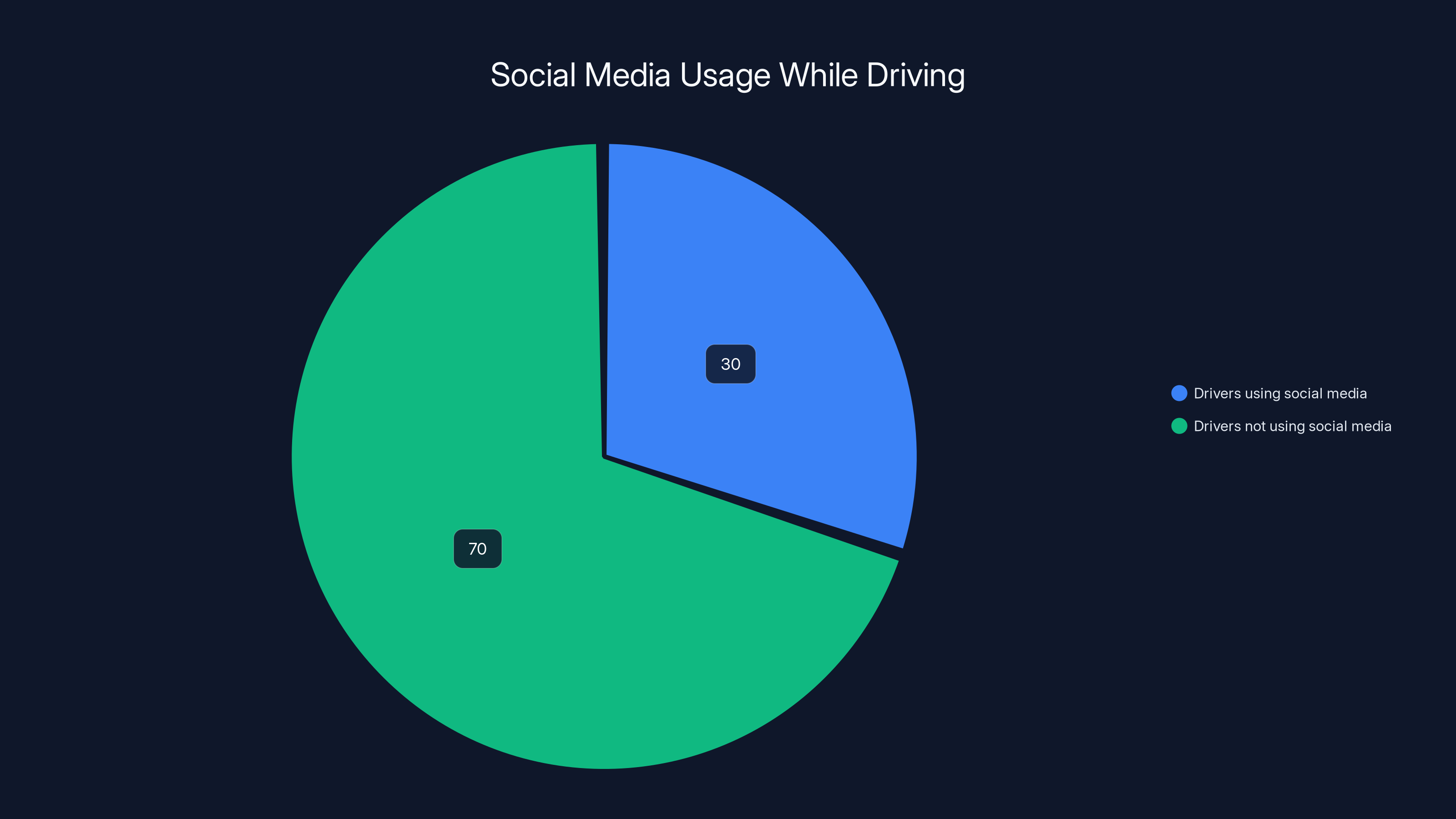

Approximately 30% of drivers admit to using social media while driving, highlighting a significant safety concern. Estimated data.

What Happened: The McCarty-Wroten Case Explained

The Incident Timeline

On the evening of the incident, Tynesha McCarty-Wroten was behind the wheel of her vehicle, phone in hand, actively livestreaming to her TikTok followers. The MSN report detailed how her livestream captured the moment of impact. In the video, she can be heard speaking into her phone when there's a distinct thud. An offscreen child asks, "What was that?" Her response was matter-of-fact: "I hit somebody."

But the audio told only part of the story. Surveillance footage from the intersection revealed the full picture. McCarty-Wroten's vehicle approached an intersection while the traffic light was still red. She didn't brake. She didn't swerve. She didn't appear to react at all. The vehicle continued at what investigators determined was an unaltered speed before striking Darren Lucas, who was crossing legally in the intersection.

Lucas was transported to a nearby hospital where he was later pronounced dead. He was the father of young children, known in his community, mourned by people who knew him.

The Legal Charges

The Zion Police Department charged McCarty-Wroten with two felonies. The first, reckless homicide, is a standard charge in fatal traffic accidents where the driver's behavior demonstrates a conscious disregard for the safety of others. The second charge, aggravated use of a communications device resulting in death, is more significant because it directly ties her actions to the livestream. This charge acknowledges that her use of the phone—specifically, her decision to livestream—directly contributed to the death.

The charges carry serious penalties. If convicted, McCarty-Wroten could face up to 14 years in prison for reckless homicide and up to 20 years for the aggravated use charge, though sentences would likely run concurrently.

What's notable about these charges is how they highlight the existing legal framework's attempt to address a fundamentally modern problem. Illinois prosecutors are using statutes that were written decades before livestreaming existed, applying them to a situation the lawmakers never imagined.

The Defense Response

McCarty-Wroten's attorney has maintained that what happened was an accident—a negligent act, but not an intentional or reckless one. This defense strategy is common in distracted driving cases, arguing that the defendant didn't consciously disregard safety, but rather made a mistake.

But here's where the evidence becomes crucial. The prosecution will likely argue that livestreaming while driving inherently demonstrates a conscious disregard for safety. It's not a momentary glance at a text message. It's an active, ongoing engagement that requires sustained attention. You can't livestream and also maintain full attention to the road. The two behaviors are mutually exclusive. The evidence of the unaltered speed through a red light strengthens this argument considerably.

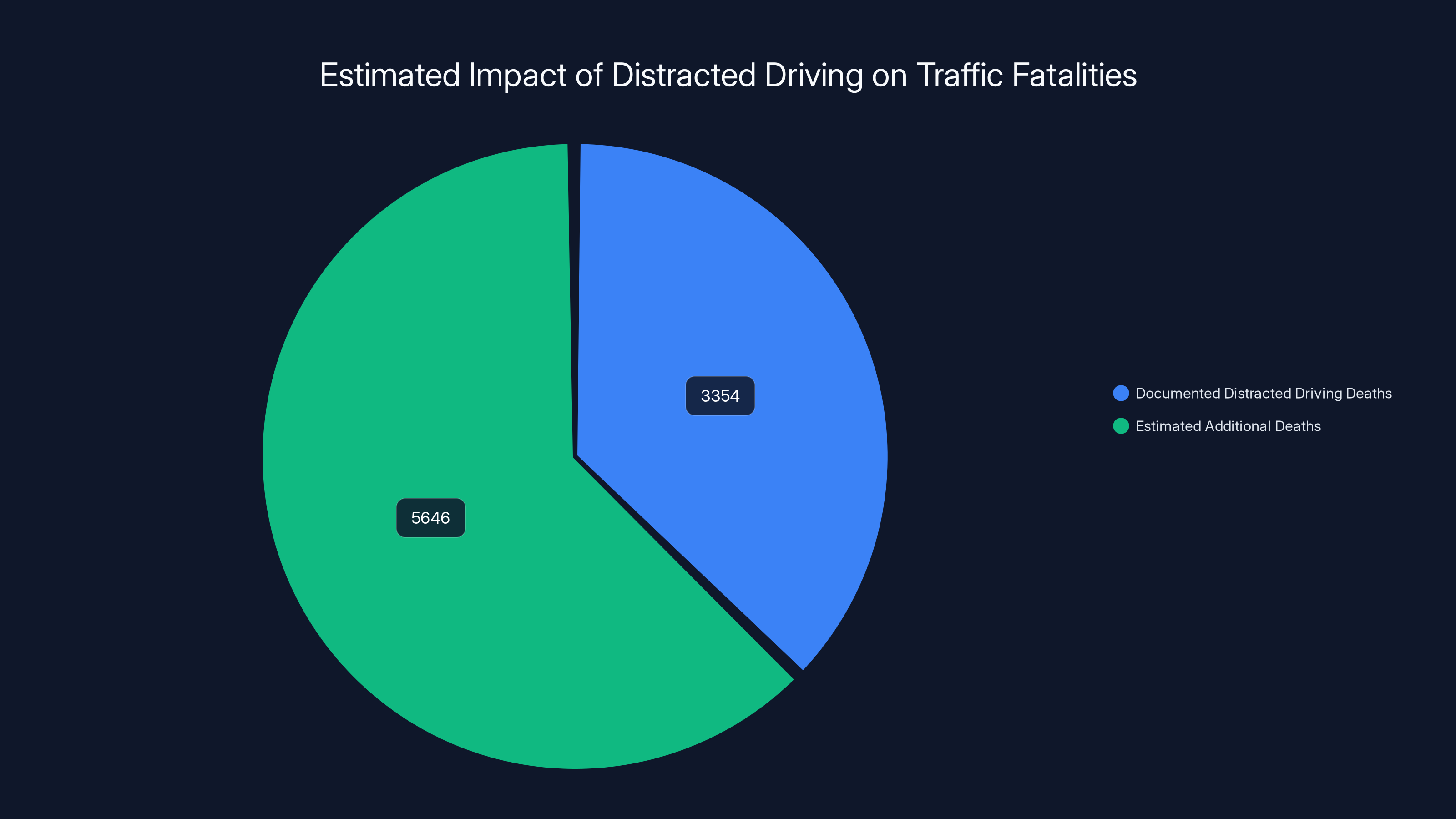

Estimated data suggests that distracted driving may account for up to 9,000 deaths annually, significantly higher than the documented 3,354 deaths in 2022.

The Broader Crisis: Distracted Driving Statistics and Trends

How Many Deaths Are We Actually Talking About?

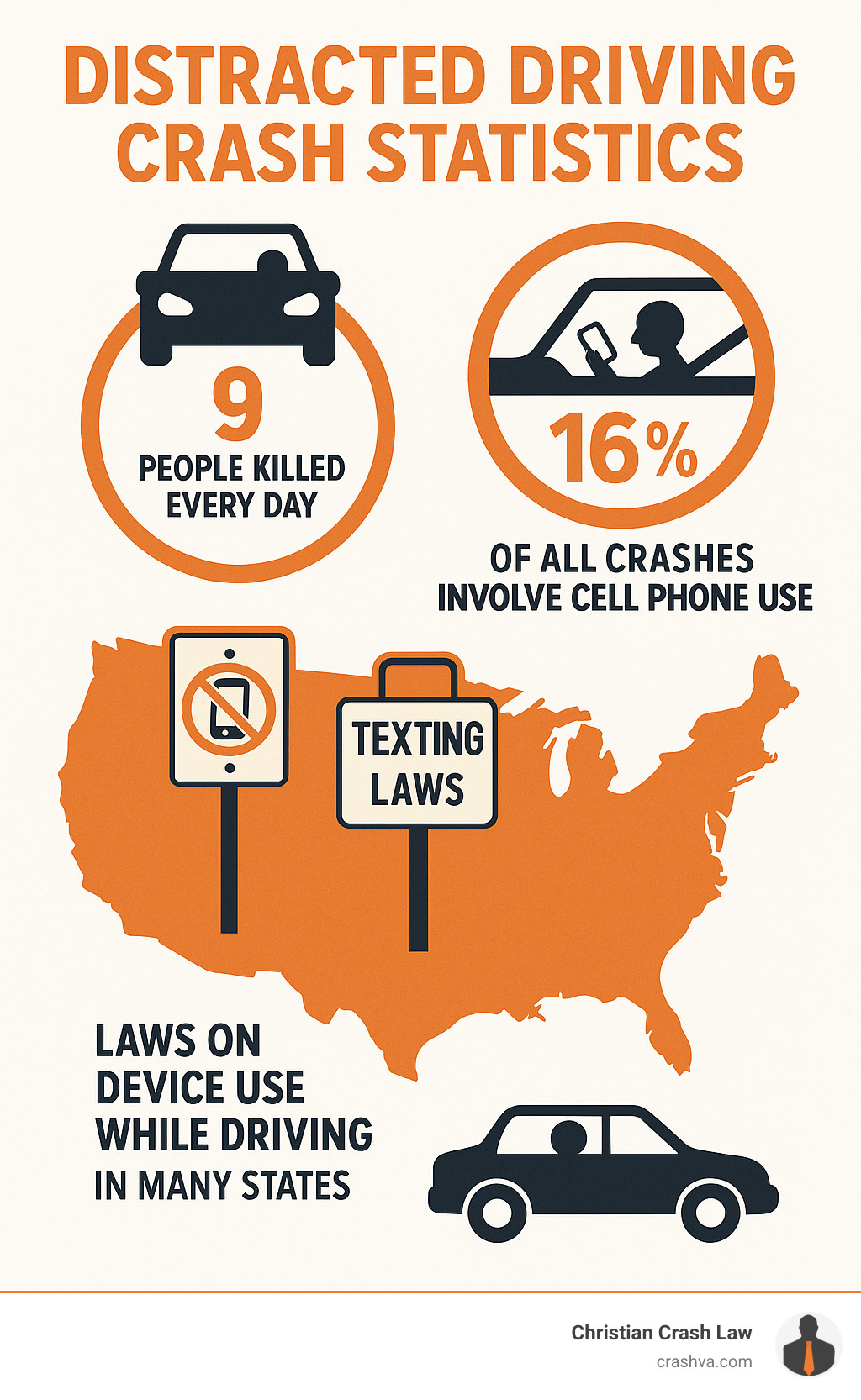

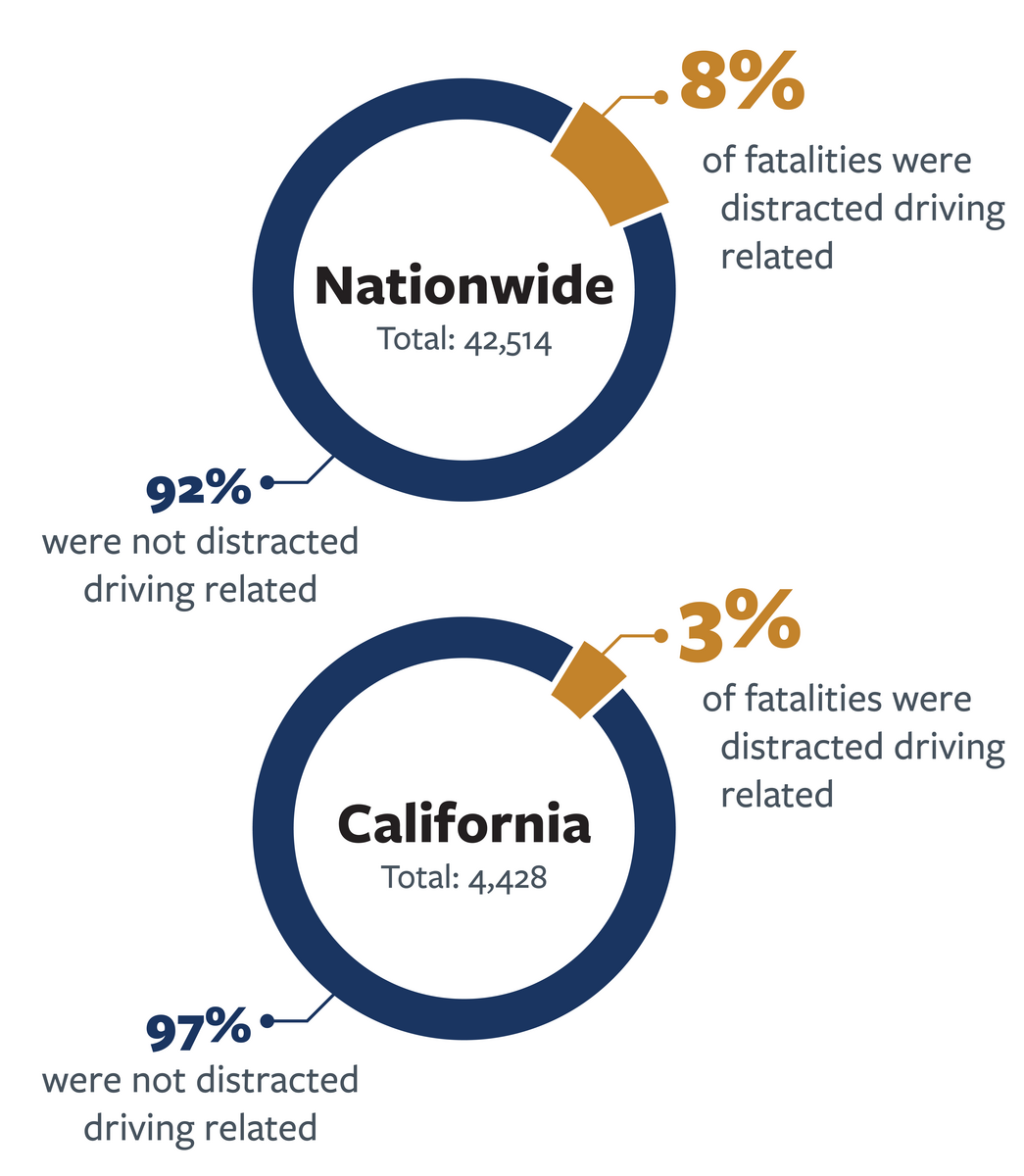

Let's establish the baseline. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), distracted driving claimed 3,354 lives in 2022, the most recent year with complete data. That's about 9 people every single day. But here's what's important to understand: these are only the deaths where distracted driving was clearly documented as the primary cause. Many accidents where a phone was involved aren't recorded as "distracted driving deaths" because investigators can't definitively prove the phone caused the crash.

The actual number is almost certainly higher.

Some research suggests that distracted driving is responsible for closer to 25% of all traffic fatalities, which would put the real number somewhere around 9,000 deaths per year. That would make it roughly equivalent to the total number of Americans who die from homicide annually. Yet we talk about one far more than the other.

The Social Media Specific Trend

What makes the current moment different is the rise of social media as a driving distraction. Traditional distracted driving research focused on texting and phone calls. You could put the phone down. But social media, particularly livestreaming, creates a different psychological pressure. There's an audience. There's a real-time engagement metric. If you stop streaming, you're losing that audience's attention.

According to surveys from the National Safety Council, approximately 30% of drivers admit to using social media while driving. Among young drivers aged 18-24, that number jumps to closer to 50%. But "using social media" encompasses a range of behaviors. Opening Twitter for a second is different from actively livestreaming.

The truth is, we don't have comprehensive data on livestreaming specifically because it's a relatively recent phenomenon. The 2022 NHTSA data predates the explosion of TikTok livestreaming. By 2025, the platforms have grown exponentially more sophisticated, making it easier and more intuitive to livestream with minimal friction.

Who's Most at Risk?

Young drivers are disproportionately affected. Drivers aged 15-19 have the highest rate of fatal accidents per mile driven, and a significant portion of those involve distraction. The psychology matters here. Younger drivers have less driving experience, which means their baseline attention allocation is already stretched thin. Add a demanding secondary task like livestreaming, and the cognitive load becomes impossible to manage.

But it's not just young drivers. Parents livestreaming while driving their children. Workers streaming for audiences to boost their side hustle. Influencers chasing engagement metrics. The problem spans demographics and cuts across socioeconomic lines.

The Psychology of Livestreaming: Why Users Can't Stop

The Feedback Loop Problem

Here's something important to understand about livestreaming: it's psychologically engineered to be addictive in ways that even texting isn't. When you send a text message, you might wait for a response, but you can put the phone down. Livestreaming creates a different dynamic. You have viewers. Real people, watching you in real-time. Some platforms show you viewer counts, which updates constantly. If you stop streaming, those people leave. The engagement metric drops.

This creates what behavioral psychologists call a "variable reward schedule." You never know when the next interesting comment will come, or when your viewer count will spike. This unpredictability is exactly what triggers the most compelling form of addiction—more so than a predictable reward.

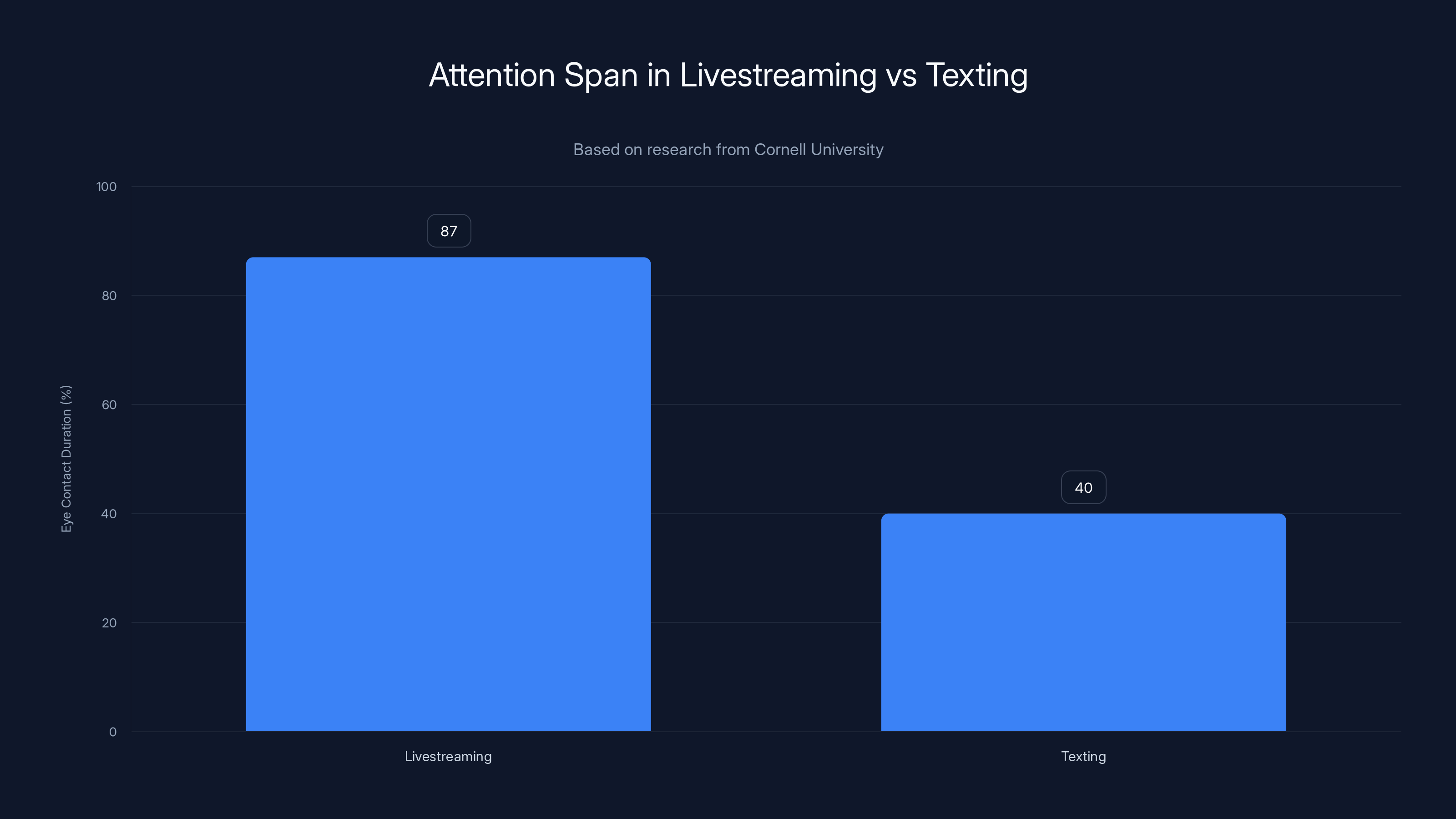

Research from Cornell University on livestreaming behavior found that users maintain eye contact with their phones for an average of 87% of the livestream duration, compared to about 40% when texting. The sustained attention requirement is dramatically higher.

Social Pressure and Validation

For many creators, livestreaming has become their job or a significant part of their social identity. TikTok's creator fund and various monetization programs mean that some livestreamers earn money based on views and engagement. This creates financial incentive to stay live, to maintain the stream, to keep the audience engaged.

But beyond money, there's social validation. Comments come in. People are "liking" your stream. Your follower count increases. These are measurable metrics of social acceptance in a way that sitting in your car in silence simply isn't.

The psychological research on social media is clear: likes, comments, and shares trigger dopamine releases in the brain similar to other addictive behaviors. Livestreaming intensifies this because the feedback is real-time and interactive. It's not just passive scrolling; it's active engagement with people who are validating you in real-time.

The Normalization Problem

Perhaps most concerning is how normalized this behavior has become. If you watch TikTok for five minutes, you'll see dozens of livestreams from cars, trucks, and even commercial vehicles. Some creators specifically stream while driving as part of their content—drive-thru hauls, road trip content, "What's my next order?" streams. It's become a genre.

When a behavior becomes normalized, it becomes invisible. You don't think of it as dangerous anymore; you think of it as a typical part of your day. Social media has made this happen at scale and at speed.

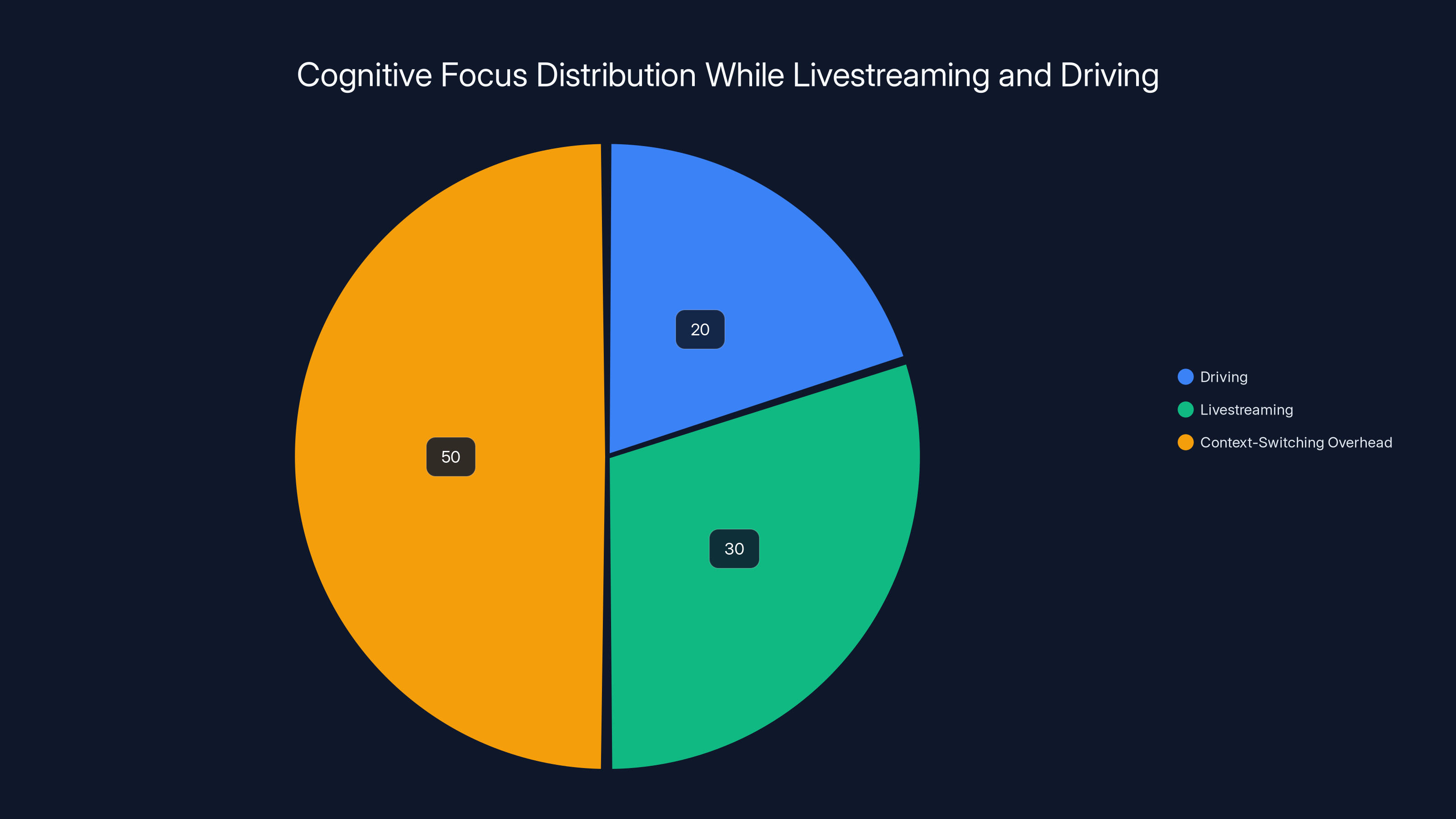

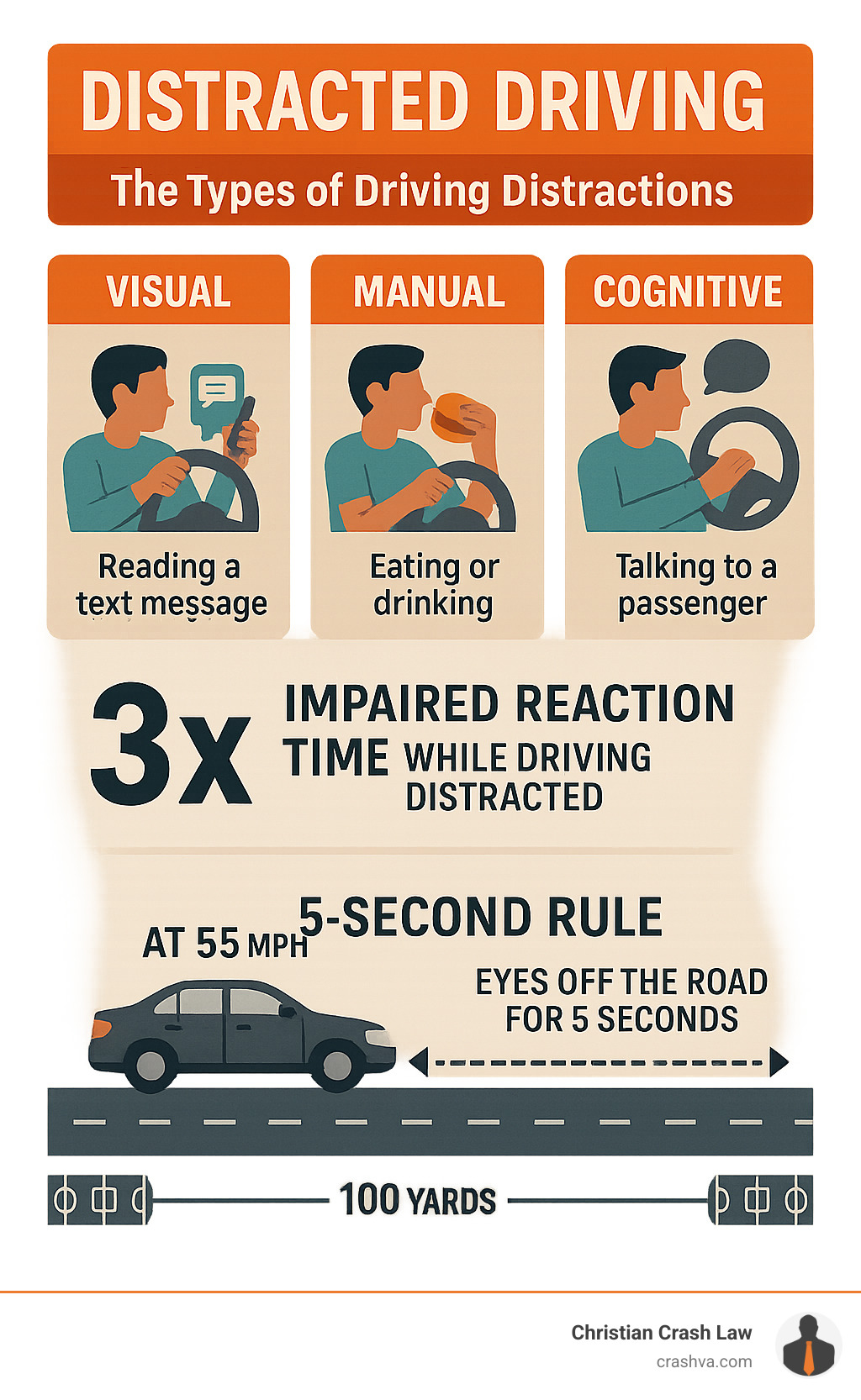

Estimated data shows that while livestreaming and driving, only 20% focus is on driving and 30% on livestreaming, with 50% lost to context-switching overhead.

Platform Responsibility: What TikTok, YouTube, and Others Are (and Aren't) Doing

Current Safety Features

TikTok has implemented some safety features. If you're driving, the app can now send notifications reminding you that you're driving and suggesting you put your phone down. Some accounts report seeing warnings when they attempt to livestream.

But here's the reality: these warnings are easy to dismiss. They're not hard blocks. Users can acknowledge the warning and continue livestreaming. It's safety theater—it allows the platform to claim it's addressing the problem without actually preventing the behavior.

YouTube has similar features, as does Instagram. Meta has implemented more aggressive interventions in some markets, including features that prevent you from going live while the phone detects that you're driving. But in other markets and on other platforms, the interventions are minimal.

The Legal Gray Area

Platforms argue that they're not responsible for how users choose to use their tools. This is a common defense. TikTok didn't tell anyone to livestream while driving. The feature exists, yes, but so do hundreds of other features. It's the user's choice.

This argument has some merit. You can use a knife to cook a beautiful meal or to harm someone. The knife manufacturer isn't responsible for how you use it. But here's where it breaks down: knives aren't algorithmically optimized to encourage you to use them in specific ways. Social media platforms are.

TikTok's algorithm learns what keeps you engaged and shows you more of it. If you regularly watch driving-related content, you'll see more of it. If your own driving streams get good engagement, the algorithm will promote them. The platform is actively, through its design, creating an environment where this behavior is encouraged, even if no one explicitly says "go livestream while driving."

The International Difference

In some countries, the legal pressure on platforms is stronger. The European Union's Digital Services Act, for instance, creates more direct liability for platforms regarding harmful content. Some countries have begun pushing back harder on livestreaming-while-driving content specifically.

But in the United States, the Communications Decency Act Section 230 has traditionally protected platforms from liability for user-generated content. This means TikTok is not legally responsible for what users do with their livestreams. The argument is that they're a platform, not a publisher. They don't control what users create.

But Section 230 has exceptions, and the landscape is shifting. Courts have begun asking whether algorithmic promotion of harmful content crosses the line from "platform" to "publisher." If the algorithm is actively promoting driving livestreams, is the platform still just a neutral platform?

Legal Framework: Distracted Driving Laws in 2025

The State of State Laws

Distracted driving laws in America are a patchwork. Every state has some version of a distracted driving law, but they vary dramatically in specificity and penalty.

Some states have primary laws, meaning police can pull you over solely for using a phone while driving. Others have secondary laws, meaning they can only cite you for distracted driving if you're also committing another violation. Some states ban handheld phone use entirely while driving. Others only ban texting. A few have no specific distracted driving statutes at all.

Illinois, where the McCarty-Wroten incident occurred, has relatively comprehensive distracted driving laws. It bans texting while driving for all drivers and bans handheld phone use for drivers under 19. But the statute that applies to her case—aggravated use of a communications device resulting in death—is more recent and more specific to situations where phone use directly causes a fatality.

The Problem with Older Laws Applied to New Problems

Many distracted driving convictions still rely on statutes written before smartphones existed. A law against "reckless driving" or "negligent operation of a motor vehicle" can certainly be applied to someone who's livestreaming, but the statute wasn't written with livestreaming in mind.

This creates challenges for prosecution. You have to argue that livestreaming constitutes "reckless behavior" under a statute that doesn't mention phones, cameras, or social media. It's like trying to prosecute someone for streaming deepfake content using laws written for photocopying. The law eventually covers it, but not elegantly.

Some states have begun updating their statutes. Several states have now criminalized livestreaming or actively streaming video while driving specifically. But most haven't. The legal framework is racing to keep up with technology, and it's losing.

Federal Possibilities

There have been discussions at the federal level about implementing uniform distracted driving standards, similar to how federal law addresses drunk driving. But this hasn't materialized, partly because transportation law is traditionally a state matter, and partly because of political resistance to federal overreach.

What's more likely in the near term is increased state-level legislation. As more cases like McCarty-Wroten's emerge, legislatures will feel pressure to act. We're already seeing this. Several states have drafted or passed laws specifically targeting livestreaming while driving in 2024 and 2025.

Livestreaming demands significantly more sustained attention, with users maintaining eye contact for 87% of the duration compared to 40% during texting. This highlights the immersive and engaging nature of livestreaming.

The Victim's Story and Community Impact

Who Was Darren Lucas?

Much of the media coverage of this incident focuses on the driver and the mechanics of the crash. But it's important to center the victim. Darren Lucas wasn't a statistic or a cautionary tale. He was a person.

Reports indicate he was a father. He was part of a community. His death created a void that no amount of legal proceedings can fill. His children lost a parent. His community lost someone they knew. The woman he was trying to cross the street to see lost a loved one.

This is what gets lost in discussions about distracted driving policy. It's abstract until it affects someone you know. But it's happening repeatedly across America, and most of the time, we don't hear about it.

Systemic Failures That Led to This Moment

No single person, law, or company is exclusively responsible for this death. It's the result of a systemic failure at multiple levels:

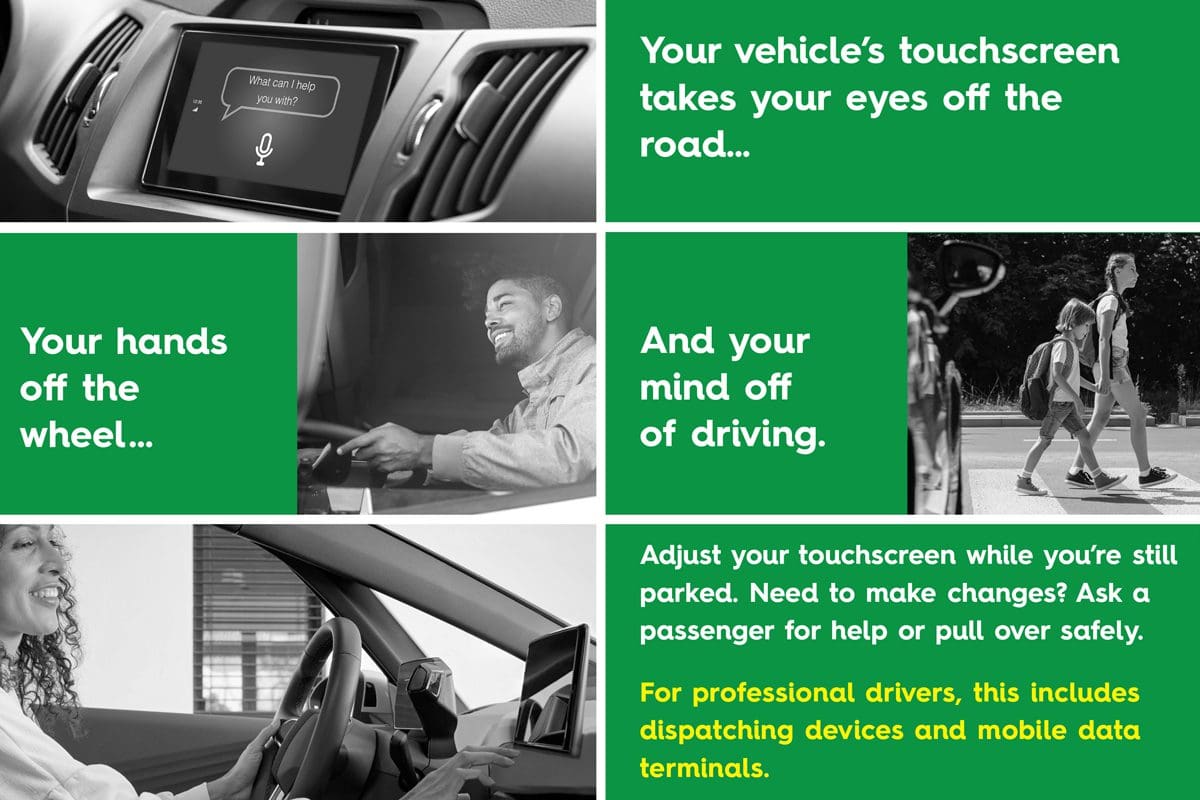

Platform design that creates compulsive engagement loops. Legal frameworks that haven't kept pace with technology. Road design that expects human perfection—even a momentary lapse in attention becomes fatal. Cultural normalization of phone use while driving. Weak enforcement of existing laws. Lack of education about the severity of distracted driving risks.

To prevent another Darren Lucas, we need to address all of these simultaneously. No single solution will work.

What Platforms Should Be Doing: Best Practices and Proposed Solutions

Hard Blocks vs. Soft Warnings

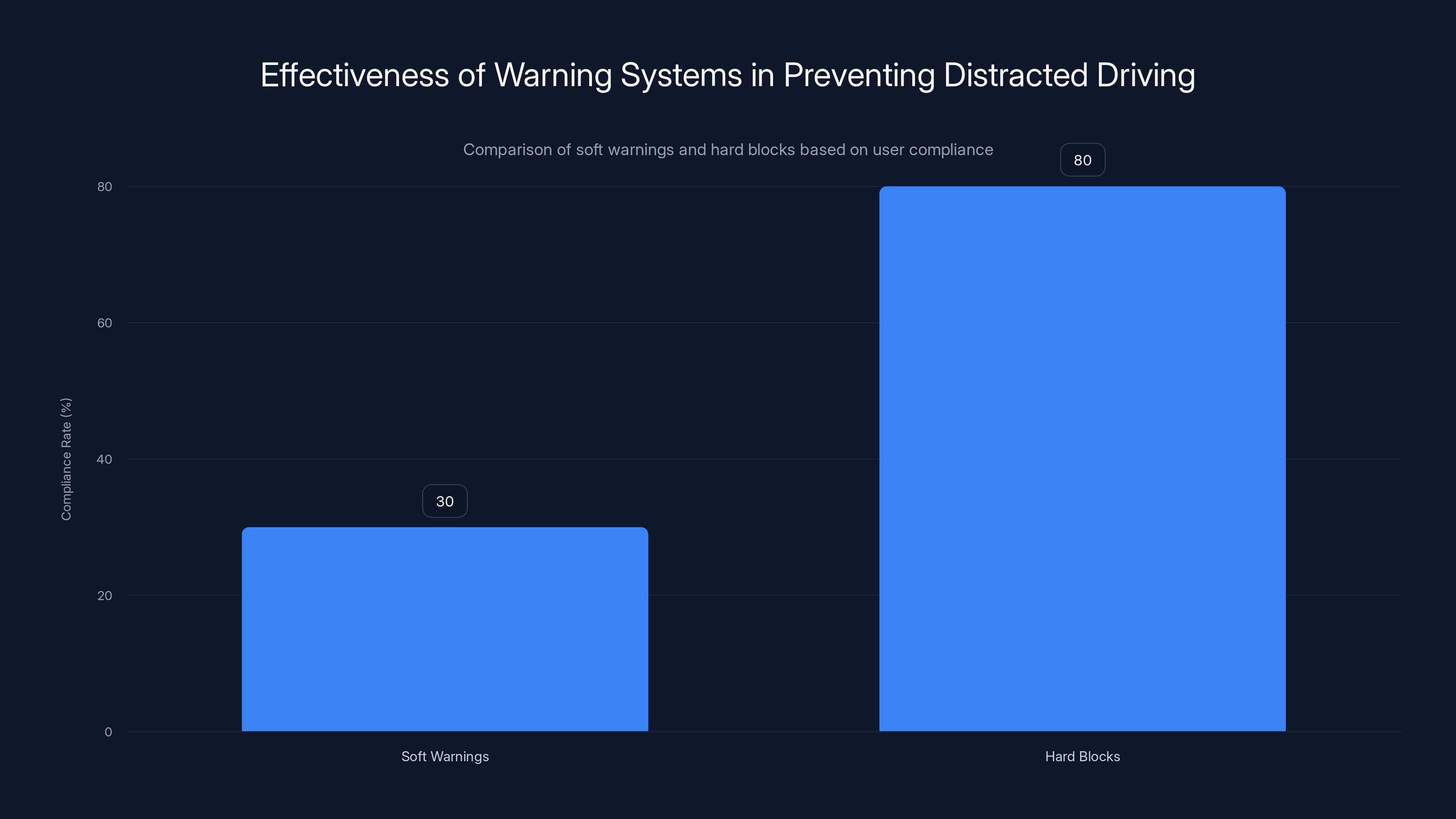

Most platforms currently use soft warnings—notifications that suggest you stop, but allow you to continue. This is better than nothing, but barely. Research on warning systems shows that soft warnings are ignored in about 70% of cases when the user is motivated to continue the behavior.

Hard blocks would be more effective. If the phone detects motion consistent with driving, the app could block livestream functionality, much like how some music apps disable certain features while you're driving. This isn't technically complicated—phones already have the sensors and the capability.

Why don't platforms implement this? Partly it's liability concern (what if the detection is wrong?). Partly it's friction—any feature that prevents monetization or engagement is seen as bad for business. And partly, frankly, it's that the platforms don't face enough legal pressure to do so yet.

Age Restrictions and Enhanced Warnings for Young Drivers

Young drivers are disproportionately affected by distracted driving. Platforms could implement age-based restrictions. For users under 21, livestreaming could be disabled while the device detects driving. For users aged 21-25, enhanced warnings with longer cooldown periods could be implemented.

This isn't paternalism; it's harm reduction. We already restrict driving privileges based on age in many ways. We could extend that to phone-based distractions.

Real-Time Accountability Features

Some platforms could implement features that make the stakes of distracted driving behavior more apparent. For instance, when you start a livestream, a notification could inform viewers that you're currently driving. This social pressure might actually be more effective than warnings. If your viewers knew you were risking people's lives for content, some might call it out.

This could backfire if not designed carefully—it might create a challenge culture around livestreaming while driving. But if implemented with clear messaging about the dangers, it could shift the social norm around the behavior.

Partnership with Public Health Campaigns

Platforms could partner with organizations like the National Safety Council to include distracted driving awareness in their educational content. Not as ads, but as organic content. Platforms already create awareness campaigns for mental health, social issues, and other public health concerns. Distracted driving could be treated similarly.

Hard blocks are estimated to achieve an 80% compliance rate, significantly higher than the 30% compliance rate for soft warnings. Estimated data based on typical user behavior patterns.

Insurance and Liability Questions: Who Pays?

Criminal Liability vs. Civil Liability

McCarty-Wroten faces criminal charges, which is the focus of most coverage. But there's also the civil side. Darren Lucas's family will likely sue for damages. This is where insurance comes into play.

Her auto insurance will almost certainly deny coverage for willful misconduct (which livestreaming while driving likely qualifies as). This means she could be personally liable for damages, potentially ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars depending on jury awards and settlement amounts.

The family could also potentially sue TikTok, arguing that the platform's design and lack of safety features made them liable as an accessory to the harm. This is a novel legal theory—nothing exactly like this has been litigated extensively in American courts. But it's becoming more plausible as courts reconsider platform liability more broadly.

Insurance Industry Pressure

Insurance companies are beginning to pay attention to distracted driving in new ways. Some insurers are considering surcharges for drivers with documented distracted driving violations. Some are beginning to push for stronger legislative action at the state level.

Insurance is a powerful pressure point. When insurance companies start charging more for behavior, that behavior often changes. If livestreaming while driving became a documented distraction (tracked similarly to speeding tickets), insurance costs would skyrocket, creating a financial deterrent on top of the legal one.

What About the Platform's Responsibility? A Deeper Analysis

Algorithmic Amplification of Dangerous Content

The key issue isn't whether TikTok "told people" to livestream while driving. It's whether TikTok's algorithm amplifies that content once users create it. If you're a TikToker and you film a road trip livestream, does the algorithm show it to more people? If so, TikTok is actively promoting a behavior it acknowledges is dangerous.

We don't have public access to TikTok's algorithm, so we can't definitively prove this. But based on how social media algorithms generally work, it's highly probable. Entertainment content gets engagement. Driving content is inherently active and immediate. Livestreams get promoted more than prerecorded videos because they're live. The algorithmic incentives all point toward promoting this content.

The Platform Immunity Question

Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, platforms are generally immune from liability for user-generated content. But there's been a notable shift in how courts interpret Section 230. In recent years, courts have begun to argue that algorithmic amplification might not be covered by Section 230 because it constitutes editorial action.

If TikTok is algorithmically promoting livestreams from cars, a court might decide that it's no longer acting as a neutral platform but as an editor. And if it's editing (through algorithmic curation) to promote dangerous content, does immunity apply?

This is still an open legal question. But it's the direction the law is shifting, especially in response to pressure around other harms amplified by algorithms.

While over 90% of drivers believe distracted driving is dangerous, 70% still use their phones while driving. Estimated data highlights the belief-behavior gap.

Solutions That Could Actually Work: A Multi-Layered Approach

Technical Solutions

The most immediate solution is technical. Smartphones already have the capability to detect when they're in a moving vehicle. Apple and Google could mandate that all apps implement features that disable certain functionalities while driving is detected. This wouldn't require legislation; it could happen within existing platform governance frameworks.

Mobile operating systems could treat "driving" as a permission similar to location or camera access. Apps would need explicit permission to function while driving. Most would be blocked by default. Only navigation apps would be excepted.

This is within the technical capability of Apple and Google right now. The question is whether they have the political will to implement it.

Legislative Solutions

States need to update their distracted driving laws to specifically address livestreaming and real-time social media engagement. The law should be clear: actively livestreaming while operating a vehicle is a felony if death results, a misdemeanor if serious injury results.

Critically, these laws should also create a liability framework that makes it clear the penalty applies regardless of fault in the broader accident. Even if you're hit by someone else and you hit a pedestrian, but you were livestreaming, you bear responsibility.

Federal legislation could set minimum standards, though that would be politically difficult. But states can act immediately.

Cultural Solutions

Normalization of distracted driving didn't happen overnight. It resulted from years of gradual acceptance. Changing the culture will require sustained messaging about the dangers, but also social influence from credible messengers.

TikTok creators themselves could be powerful messengers here. If influential creators began calling out the danger—if they refused to create driving content—that would shift cultural norms faster than any PSA. This would require TikTok to encourage this messaging, or at minimum, not algorithmically suppress it.

Enforcement Solutions

Right now, distracted driving is notoriously underenforced. Police pull people over for speeding regularly. They rarely pull people over for phone use unless it's egregious. Police departments lack training on spotting distracted driving. There's no systematic way to report it.

Communities could implement anonymous distracted driving reporting systems, similar to what exists for DUI. This would create data and pressure on police to enforce existing laws.

The Influencer Impact: How Creator Culture Contributes

The Monetization Incentive

Tynesha McCarty-Wroten wasn't livestreaming for fun. She was building an audience. Building an audience can lead to monetization through TikTok Creator Fund payments, brand partnerships, merchandise sales, or other revenue streams.

For creators with limited income opportunities, these can be significant. TikTok's creator fund pays between

This creates a perverse dynamic where the riskier the content, the more engagement it gets, the more money it makes. A calm driving livestream might get 50 viewers. An erratic, dangerous driving livestream might get 500. That's a 10x difference in potential earnings.

Platforms could address this by explicitly excluding certain content categories from monetization. If livestreams from cars generated no ad revenue, the incentive structure would shift immediately.

The Peer Influence Effect

But it's not just about money. It's about status. If your peers are getting thousands of views for their driving content, you feel pressure to do the same. If the top creators in a particular niche are all driving livestreamers, that becomes the expected content format.

This is how dangerous behaviors spread in communities. Someone does it first. They get rewarded (views, engagement, money). Others copy them. The behavior becomes normalized. By the time people recognize the danger, it's embedded in the culture.

Breaking that cycle requires early intervention—before the culture becomes entrenched.

Precedent Cases and How They Inform This One

The History of Distracted Driving Prosecutions

Before this case, there were other high-profile prosecutions for distracted driving resulting in death. Some resulted in convictions, others in plea deals. The challenge has always been proving that the distraction directly caused the death.

What makes the McCarty-Wroten case unique is the recorded evidence. She literally captured the moment of impact on video. There's an audio record of her reaction. There's a visual record of the collision. This eliminates the ambiguity that typically surrounds distracted driving cases.

But this also highlights how unusual it is to have such clear evidence. Most distracted driving deaths don't have this kind of documentation. In most cases, it becomes a he-said-she-said situation about whether the person was using their phone.

Phone Records as Evidence

In many distracted driving prosecutions, phone records become crucial. Investigators can subpoena records showing that the driver sent or received text messages at the moment of the accident. But livestreaming creates a digital record that's even more complete.

The livestream platform itself has records of when the stream started, how long it lasted, how many viewers it had, what the video contained, etc. This creates an audit trail that makes prosecution much more straightforward.

The Role of Neuroscience: Understanding the Brain on Social Media

Cognitive Load and Divided Attention

Driving is a complex task that requires sustained attention to multiple information sources simultaneously. Your brain needs to monitor the road, check mirrors, track traffic patterns, anticipate other drivers' moves, and execute precise physical movements.

Livestreaming while driving creates cognitive load at the limit of human capability. You're trying to maintain conversation, monitor comments, ensure the camera is steady, watch the road, and operate the vehicle all simultaneously. Most people's brains simply can't handle this.

Neuroscientific research shows that sustained multitasking causes noticeable degradation in performance on both tasks. You're not just doing two things at half efficiency. The interaction between them makes you worse at both than if you were doing them alone. Driving while livestreaming isn't 50% focused on each; it's more like 20% focused on driving and 30% focused to the livestream, with the remaining 50% burned up in context-switching overhead.

The Reward Pathway Problem

When you see a notification that someone has liked your livestream, your brain's reward center activates. This is mediated by dopamine, the same neurotransmitter involved in addiction. The more frequently the reward occurs, and the more unpredictable it is, the more powerful the addiction mechanism.

A livestream is the most frequent-feedback social media environment. You can see real-time engagement in a way you can't with a posted video. Viewers send comments, emojis, gifts (in monetized livestreams). The feedback is constant and unpredictable. Your brain is being bombarded with dopamine signals.

This isn't a moral failing of livestreamers. It's their brains being hijacked by engineered feedback systems. People are biologically vulnerable to this dynamic, and platforms are intentionally exploiting that vulnerability.

What Drivers Actually Think: Surveys and Research on Distracted Driving Attitudes

The Disconnect Between Belief and Behavior

Surveys show that the vast majority of drivers (over 90%) believe that distracted driving is dangerous. They acknowledge that using a phone while driving increases crash risk. They recognize that it's illegal in most places.

Yet many of these same drivers regularly use their phones while driving. This disconnect between belief and behavior is significant. It tells us that knowledge alone isn't sufficient to change behavior.

People rationalize. "I'm just checking one message." "I'm only driving for five minutes." "I'm experienced; I can handle it." "It's just a red light." The rationalizations vary, but the pattern is consistent.

Age Differences in Risk Perception

Younger drivers are statistically worse at assessing risk related to distracted driving. They're more likely to believe they can multitask effectively. They're more likely to downplay the danger. This is partly because of brain development (the prefrontal cortex, which handles risk assessment, isn't fully developed until the mid-20s) and partly because of limited driving experience.

This means that public health interventions targeting young drivers need to be different. Traditional risk-based messaging ("3,000 people die from distracted driving") has limited effectiveness. But peer-based messaging and social norm shifting work better.

Economic Impact: The Cost of Distracted Driving to Society

Direct Medical Costs

Every fatal accident generates enormous costs. Emergency response, hospitalization, surgery, long-term care for survivors with permanent injuries. A single fatal car crash can generate

Nonfatal serious injuries are often even more expensive in aggregate because there are more of them. A severe spinal cord injury might require lifelong care costing millions. A traumatic brain injury might result in permanent disability.

When you multiply this across thousands of distracted driving incidents annually, we're talking about tens of billions of dollars in medical costs.

Lost Productivity and Income

When someone dies in a car crash, they stop working. Income stops. If they have children, there's lost financial support. If they're a worker, businesses lose productivity. Multiply this across the workforce, and you get a significant economic drag.

For nonfatal injuries that result in disability, there's often lost work capacity. Someone in a wheelchair might not be able to return to their previous job. Someone with cognitive impairment might lose earning capacity.

Ripple Effects

Then there are the less obvious costs. Psychological treatment for trauma. Higher insurance premiums for everyone. Traffic congestion from accidents. Property damage. Legal costs.

Estimates suggest that distracted driving costs the American economy between

Yet we spend far less on prevention than we do on treating the consequences.

The Road Ahead: Predictions for Legal and Platform Changes

Likely Legislative Changes in 2025-2026

Based on current trends, we can expect:

- State-level specific statutes criminalizing livestreaming while driving, with enhanced penalties if death results

- Federal minimum standards for platform safety features, possibly included in broader social media regulation

- Insurance industry changes incorporating distracted driving violations into premium calculations more explicitly

- Enhanced penalties for repeat offenders and for livestreaming specifically (higher penalties than general distracted driving)

Platform Changes We Should Expect

Platforms will likely implement:

- Hard blocks on livestreaming when driving is detected (probably first Apple, then Google, then social media platforms)

- Age-based restrictions on livestreaming while driving

- Content moderation of driving livestreams, removing or demonetizing them

- Public awareness campaigns featuring creators discussing the risks

These won't happen immediately, but the pressure is mounting.

The Broader Conversation About Platform Accountability

The McCarty-Wroten case is part of a larger conversation about platform responsibility. Over the past few years, there's been growing momentum to hold platforms accountable for algorithmic amplification of harmful content. This case might become a test case for that argument.

If the civil lawsuit against TikTok (which will likely be filed by Lucas's family) succeeds in establishing that algorithmic amplification created liability, it could change the entire landscape of platform responsibility in America.

Conclusion: What This Case Reveals About Our Technology and Our Society

The death of Darren Lucas and the prosecution of Tynesha McCarty-Wroten isn't just a story about one bad driver or one dangerous moment. It's a symptom of something much larger: a collision between technology, human psychology, legal frameworks, and cultural values that we haven't figured out how to navigate.

We've created devices and platforms that are phenomenally effective at capturing and holding human attention. We've designed business models around that attention. We've normalized behaviors that would have seemed insane a decade ago—filming yourself while doing inherently dangerous activities, broadcasting your life to strangers, chasing metrics of validation from invisible audiences.

But we haven't created the social, legal, or technical infrastructure to manage the consequences of these innovations. We're operating with 20th-century laws and 20th-century social norms applied to 21st-century technology. Of course the system is failing.

Fix it requires multiple simultaneous interventions:

Technical: Phones need to be equipped with better driving detection and functionality limiting while driving. This is straightforward and should happen immediately.

Legal: Laws need to catch up with technology. Livestreaming while driving should be a specific felony with enhanced penalties. This will happen, gradually, state by state.

Cultural: We need to shift the social norm around documenting our lives while driving. Creators need to refuse to create this content. Audiences need to stop rewarding it with engagement. This is the hardest change and the slowest, but it's essential.

Structural: Platforms need to align their incentives away from amplifying dangerous content. If driving livestreams don't generate engagement bonuses, they won't be created. If they generate liability, they won't be hosted.

None of these interventions is controversial in principle. Everyone agrees that livestreaming while driving is dangerous. The disagreement is about who bears responsibility and what should be done.

What's clear is that the status quo—where platforms express concern but do minimal intervention, where laws are inadequate, where culture treats dangerous behavior as normal—isn't sustainable. Another person will die. Then another. And at some point, the pressure for change will become undeniable.

Darren Lucas's death might be the case that finally forces that reckoning.

FAQ

What exactly was Tynesha McCarty-Wroten charged with?

She was charged with two felonies: reckless homicide and aggravated use of a communications device resulting in death. The first charge applies to fatal traffic accidents where the driver's behavior shows disregard for safety; the second specifically addresses her use of the phone (livestreaming) during the incident. These charges carry potential sentences of 14 and 20 years respectively, though they would likely be served concurrently.

How common is livestreaming while driving?

While specific data on livestreaming while driving is limited, surveys indicate that approximately 30% of all drivers and up to 50% of drivers aged 18-24 admit to using social media while driving. Livestreaming is a subset of this behavior, but it's growing, particularly among content creators building audiences. The behavior isn't rare, but it's historically underreported in distracted driving statistics because platforms don't systematically track it.

Can the victim's family sue TikTok?

They almost certainly will attempt to, though the outcome is uncertain. Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, social media platforms have traditionally been immune from liability for user-generated content. However, there's a growing legal argument that algorithmic amplification of harmful content might not be protected by Section 230, since algorithms constitute editorial curation rather than neutral platform hosting. The family's case would need to prove that TikTok's design and algorithms actively encouraged driving livestreams, making the platform liable as an accessory to the harm.

What safety features do social media platforms currently have for driving?

Most major platforms (TikTok, Instagram, YouTube) have implemented soft warnings that notify users they're driving and suggest putting their phone down. Some have automatic triggers that activate when the phone detects motion consistent with vehicle movement. However, these are generally easy to dismiss, and enforcement is minimal. Apple and Google have more aggressive features on their operating systems that can disable certain functionality while driving, but social media platforms themselves have not implemented hard blocks that prevent livestreaming while driving is detected.

What changes to distracted driving laws are likely coming?

Experts predict that states will increasingly implement specific statutes criminalizing livestreaming while driving, with enhanced penalties if the behavior results in injury or death. Federal legislation is less likely in the short term but could eventually establish minimum standards that states must meet. Insurance industry changes are also probable, with distracted driving violations being incorporated more explicitly into premium calculations. The trend is toward stricter regulation, particularly given high-profile cases like this one.

How does livestreaming compare to texting in terms of danger?

Livestreaming is substantially more dangerous than texting. Research shows that users maintain visual attention on their phones during 87% of a livestream, compared to about 40% when texting. The sustained engagement requirement, combined with the psychological reward system of real-time feedback, makes livestreaming create higher cognitive load and more distraction than other phone behaviors. Additionally, you can complete a text in seconds and put the phone down, whereas livestreaming requires continuous engagement.

What role does the algorithm play in this?

TikTok's algorithm learns what content generates engagement and promotes more of it. If driving livestreams get high engagement, the algorithm will show them to more users, potentially creating a feedback loop where the behavior becomes normalized and encouraged. This is distinct from the platform simply existing; it's the platform's design actively promoting the behavior. This distinction matters legally because it raises questions about whether the platform remains a neutral host or becomes an active publisher of the content.

How does this case compare to previous distracted driving prosecutions?

The McCarty-Wroten case is unusual in the clarity of the evidence. She livestreamed the collision, creating an audio and video record of the moment of impact and her reaction. Most distracted driving prosecutions rely on phone records, witness testimony, and accident reconstruction—all of which can be ambiguous. This case has essentially unambiguous evidence that she was actively engaged with her phone at the moment of impact, which significantly strengthens the prosecution's case and makes the charges more straightforward to prove.

What responsibility do content creators have?

Content creators have an ethical responsibility to avoid creating content that models dangerous behavior, particularly for audiences of young people who are disproportionately susceptible to both distracted driving and social media influence. Legally, creators aren't typically held responsible for viewers imitating their dangerous behavior, but this could change. Socially, there's a growing expectation that creators will be mindful of their influence and won't promote obviously harmful activities for engagement metrics.

Could platforms face criminal charges themselves?

Under current U.S. law, it's highly unlikely that platforms would face criminal charges. Civil liability is more plausible, though Section 230 immunity protects them from most civil lawsuits related to user-generated content. The more likely scenario is that victims' families pursue civil suits arguing that algorithmic amplification of dangerous content created liability, which could eventually result in legislative changes requiring platforms to implement specific safety features.

The Bigger Picture

This incident reveals a profound tension in our modern world: we've created technologies and business models that are excellent at capturing attention, but we haven't created the governance structures to prevent that attention-capture from harming people.

TikTok didn't invent distracted driving. But it created a system that monetizes and algorithmically amplifies risky behavior. The responsibility for Darren Lucas's death isn't solely on Tynesha McCarty-Wroten, though she bears legal and moral responsibility for her choices. It's distributed across platforms that optimize for engagement without adequately considering consequences, legal systems that haven't kept pace with technology, a cultural normalization of constant documentation, and a business model that rewards putting yourself and others at risk.

Changing this will require sustained effort on multiple fronts. Technical solutions alone won't work—people will find workarounds. Laws alone won't work—they require enforcement and cultural buy-in. But a coordinated effort addressing all these dimensions could genuinely prevent the next tragedy.

The question is whether we'll wait for that effort to materialize gradually through market pressure and litigation, or whether we'll be proactive and implement the changes now, before more people die.

Darren Lucas doesn't have the luxury of waiting.

Key Takeaways

- An Illinois driver livestreaming on TikTok struck and killed a pedestrian, facing charges for reckless homicide and aggravated use of a communications device resulting in death.

- Distracted driving kills approximately 3,500 people annually in the US, with livestreaming creating psychological addiction loops that make the behavior particularly dangerous.

- Social media platforms currently use soft warnings rather than hard blocks for driving livestreams, leaving dangerous content accessible and algorithmically amplified.

- Legal frameworks haven't kept pace with technology—most states lack specific statutes criminalizing livestreaming while driving.

- Comprehensive solutions require coordinated technical interventions, legislative updates, cultural norm shifts, and business model realignment away from amplifying dangerous content.

![Distracted Driving and Social Media: The TikTok Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/distracted-driving-and-social-media-the-tiktok-crisis-2025/image-1-1766959555495.jpg)