Earliest African Cremation: 9,500 Years of Ritual and Community

Something extraordinary happened at the base of Mount Hora in Malawi around 9,500 years ago. An ancient community gathered to honor one of their own, a woman whose final rites would leave evidence so well-preserved that modern archaeologists could piece together the intimate details of her cremation millennia later.

This discovery, published in Science Advances, isn't just another archaeological find tucked into academic journals. It's a window into how early human societies organized themselves around shared purpose, community labor, and spiritual meaning. For decades, we've underestimated the complexity of hunter-gatherer rituals and the capacity of small communities to mobilize resources for something as demanding and resource-intensive as building and maintaining a cremation pyre.

The Hora-1 site sits beneath a granite overhang, a place ancient peoples returned to repeatedly over thousands of years. But this one cremation stands alone—a singular event so methodical, so intentional, that it forces us to reconsider what we thought we knew about prehistoric African societies. The remains tell a story of deliberate bone cutting, skull removal, and carefully arranged body positioning. They reveal a community willing to invest roughly 30 kilograms of carefully collected deadwood and grass into a single funeral ceremony. They demonstrate knowledge of fire management and temperature control that few historians credited to societies without written records.

What makes this discovery particularly significant isn't just that it's the oldest confirmed cremation pyre in Africa. It's that it arrived with zero warning in the archaeological record. The Hora-1 site had been excavated in the 1950s, with archaeologists carefully cataloging the uncremated burials already there. Nobody was looking for cremation evidence. Nobody expected to find it. When radiocarbon dating confirmed the 9,500-year age, it shattered the existing timeline of African cremation practices and raised urgent questions: Why this woman? Why this moment? Why here?

For researchers studying human ritual, community organization, and the emergence of complex social behaviors, the Hora-1 cremation represents a crucial missing link. It pushes cremation in Africa back by roughly 2,500 years beyond previously documented cases. It demonstrates that communities with minimal technological infrastructure could orchestrate complex, labor-intensive ceremonies. It shows that ritual sophistication and spiritual meaning aren't products of civilization as we traditionally define it.

This article unpacks everything we know about the Hora-1 discovery, explores what the evidence reveals about ancient communities, examines why cremation was so rare among hunter-gatherers, and considers what this finds means for how we interpret prehistoric social life.

TL; DR

- Oldest African pyre: The Hora-1 site in Malawi contains Africa's oldest known cremation pyre, dated to approximately 9,500 years ago through radiocarbon testing

- Intentional ritual: Evidence of cut marks on bones, skull removal, and positioned limbs suggests deliberate and choreographed funerary practices, not accidental or scavenger-caused disarticulation

- Massive community effort: Building and maintaining the pyre required approximately 30 kilograms of deadwood and grass, representing significant resource mobilization and collective labor

- Exceptional event: The cremation stands alone at a site containing multiple uncremated burials, suggesting this woman received singular, special treatment warranting investigation

- Persistent place-making: Continued fire use in the same location for several hundred years afterward indicates the cremation established a spiritually significant location linked to memory and ancestral veneration

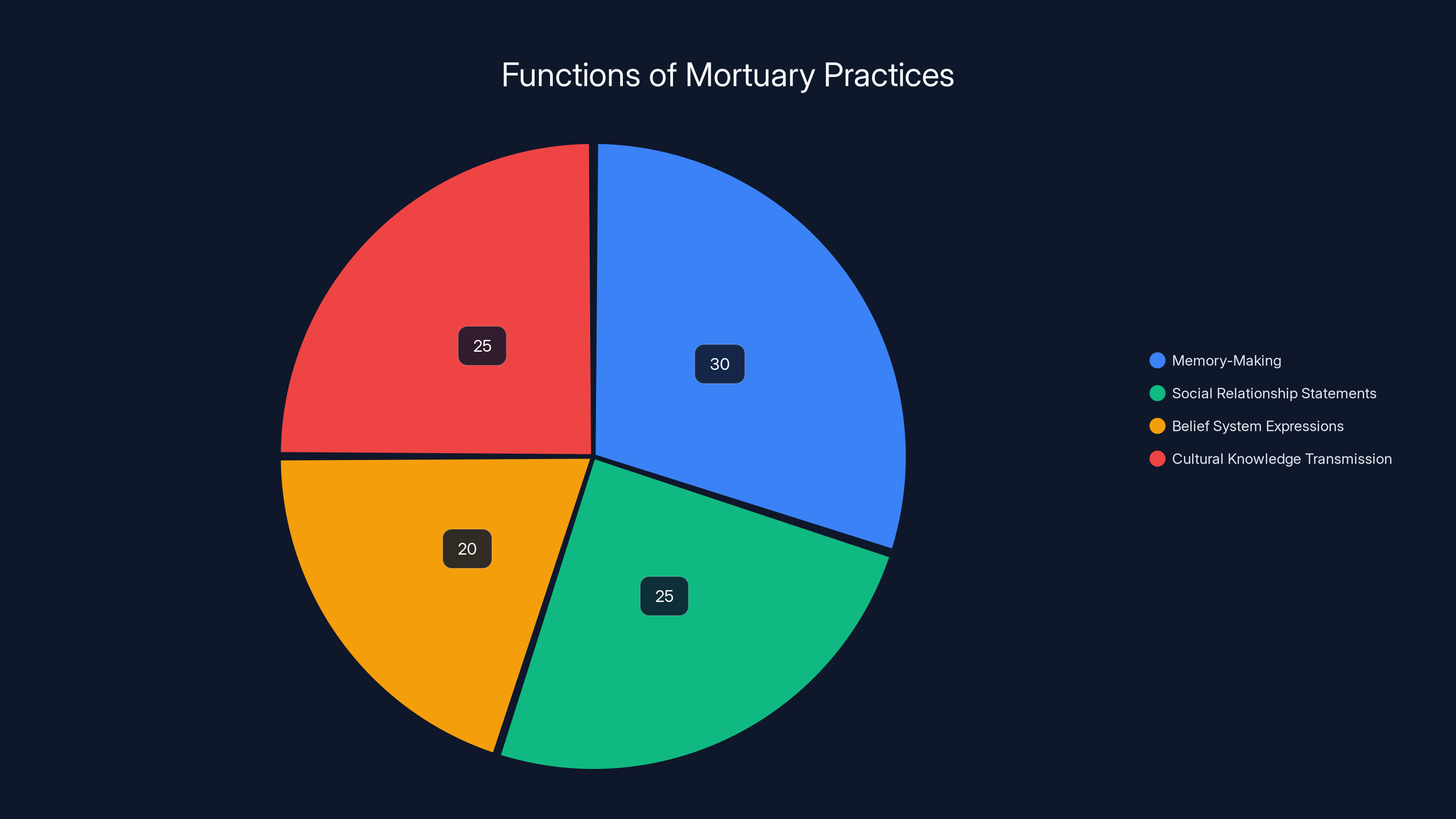

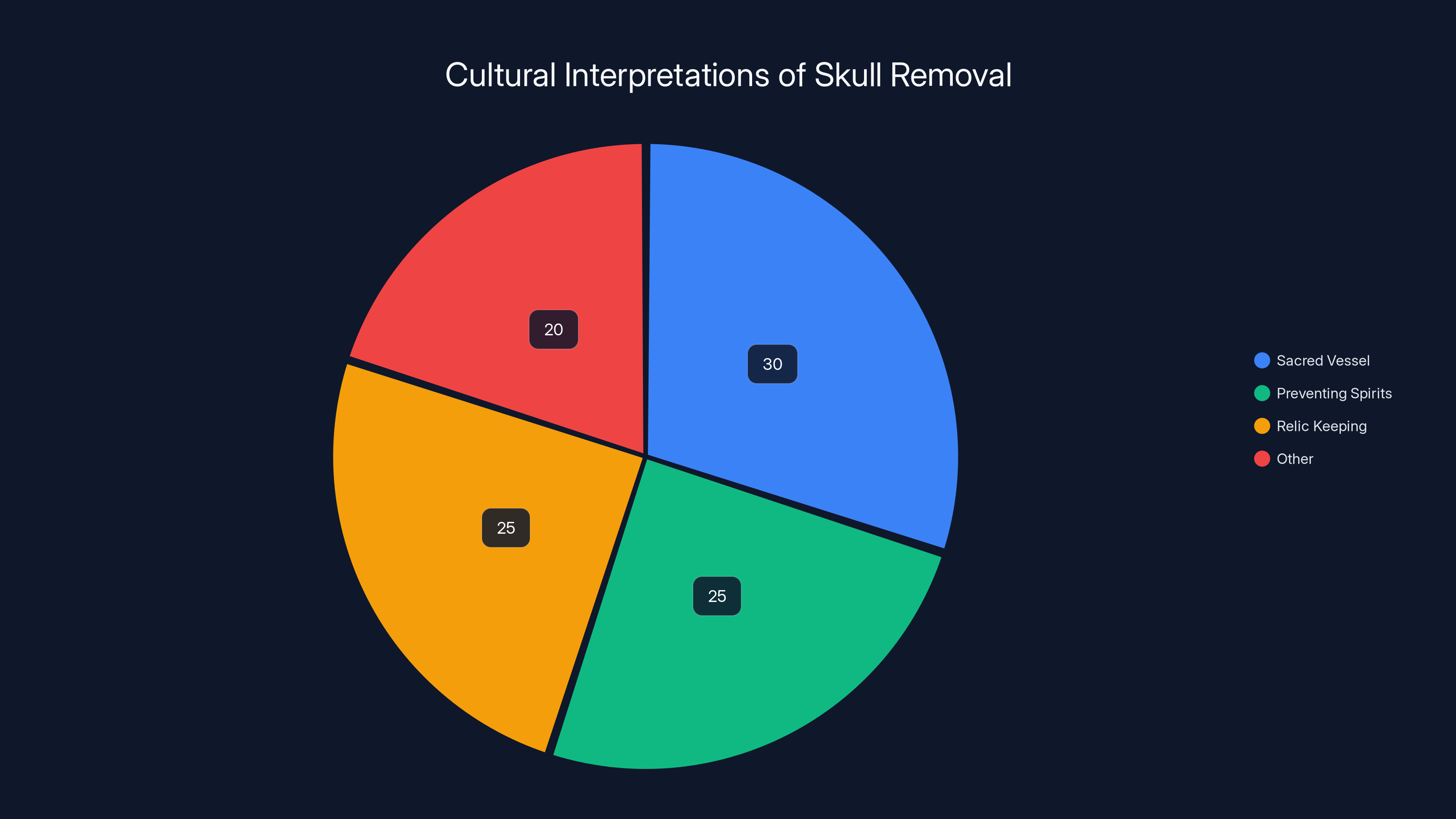

Mortuary practices serve multiple functions, with memory-making and social relationship statements being prominent. Estimated data.

The Hora-1 Site: Where Ancient Ritual Met Preservation

The Hora-1 site occupies a specific kind of archaeological real estate that researchers prize above almost all others: a location that combines excellent preservation conditions with repeated human occupation over millennia. Situated beneath an overhang at the base of a granite hill, the shelter offered protection from weathering and erosion. The ash bed that would eventually contain cremated remains sat undisturbed beneath layers of accumulated sediment, sealed away from the elements.

Archaeologists first excavated Hora-1 in the 1950s. That early work established the site's importance as a burial ground stretching back between 8,000 and 16,000 years. The team documented several intact, uncremated burials—flexed bodies of individuals interred through conventional inhumation. These burials provided a baseline chronology and demonstrated that the site had served as a meaningful place for the dead across an extended period.

What the 1950s work didn't identify was the cremation pyre itself. The distinction matters because cremation leaves a very different archaeological signature than inhumation. Cremated remains are fragmented, scattered, and often discolored by heat. They sit within ash beds and charcoal concentrations. Without modern analytical techniques, earlier excavators might have interpreted the burnt bone fragments and ashy sediment as natural deposition or recent intrusion rather than intentional cremation.

The renewed investigation of Hora-1 applied contemporary methodologies that simply didn't exist in the 1950s. Microscopic analysis of sediment layers revealed the precise sequence in which the pyre had been built and burned. Spectroscopic techniques identified chemical signatures of burning and combustion temperatures. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal samples pinpointed the event to 9,500 years ago with a remarkable degree of precision.

The cremation layer itself consisted of an ash bed spanning a contained area, containing 170 bone fragments predominantly from the arms and legs of a single individual. The ash bed's boundaries suggested a deliberately constructed pyre rather than a scattered burning event. The concentration of bone fragments in one location indicated that either the body had been burned in place or the cremated remains had been carefully gathered.

Surrounding the cremation evidence, researchers found stone points and evidence of flintknapping—tool-making activity concentrated within or immediately adjacent to the burning remains. The deliberate placement of stone tools suggested ritual significance or intentional deposition as grave goods, practices we associate with symbolic meaning rather than utilitarian accident.

What emerged from this reanalysis was the portrait of a highly organized, choreographed ceremony—not a chaotic or opportunistic burning, but something planned, resourced, and executed with precision.

The Woman: Who Was She and Why Was She Cremated?

The individual whose remains underwent cremation at Hora-1 was female, aged between 18 and 60 years old. That's the limit of what bioarchaeology can tell us with certainty. Her name is lost. Her specific achievements or status within her community—if she held any special position—remain unknowable. What we know is that someone, at some point around 9,500 years ago, judged her significant enough to warrant an extraordinary final ceremony.

The remains indicate that cremation occurred within a few days of her death. This matters because it suggests the decision to cremate happened quickly, while the body was still in reasonable condition for handling and burning. The family or community didn't preserve the corpse for extended periods; they responded rapidly to her death with a predetermined ritual.

Before the burning began, something remarkable happened. Someone—likely multiple people—carefully removed the flesh from her arm and leg bones. The cut marks visible on the skeleton indicate systematic defleshing with stone tools. This wasn't the random scarring of scavengers or the degradation caused by decomposition. These were deliberate, controlled incisions. Someone skinned her bones with intention.

After defleshing, the head was removed. The absence of skull bones and teeth in the cremation bed tells us this explicitly. Whether the head was removed before or after cremation remains unclear, but either way, it was separated from the body and didn't enter the pyre. This practice of skull removal appears in various ancient contexts and carries profound symbolic weight—potential veneration of the head as a vessel of identity or knowledge, or conversely, removal for spiritual containment of a potentially dangerous supernatural force.

With the body defleshed and the skull removed, the remaining skeleton was positioned with arms and legs flexed, suggesting careful arrangement before burning. The distribution of limb bones throughout the ash bed indicates this specific positioning. The body wasn't carelessly thrown into flames. It was choreographed, intentional, respectful—or at least laden with meaningful intent whether that meaning reflected respect by modern standards or something more complex.

Why defleshing occurred before cremation is a question without a definitive answer. Research on mortuary practices among recent ethnographic examples suggests multiple possibilities. Defleshing might have served practical purposes, making the skeleton easier to handle or arrange. It might have reflected beliefs about the relationship between body and spirit. It could have been part of secondary mortuary practices involving the curation and movement of bone—a practice documented among modern hunter-gatherers where bones of the deceased are kept, carried, or reinterred across long time spans.

Several bones bear evidence of heat exposure at different temperatures, suggesting the cremation wasn't a single, uniform burning but rather a carefully maintained fire with different zones of heat and different amounts of time in direct flame. Some bones show near-complete cremation while others retained more organic material. This variation speaks to knowledge of fire management—understanding that different parts of a pyre would achieve different temperatures and that maintaining consistent heat required constant attention.

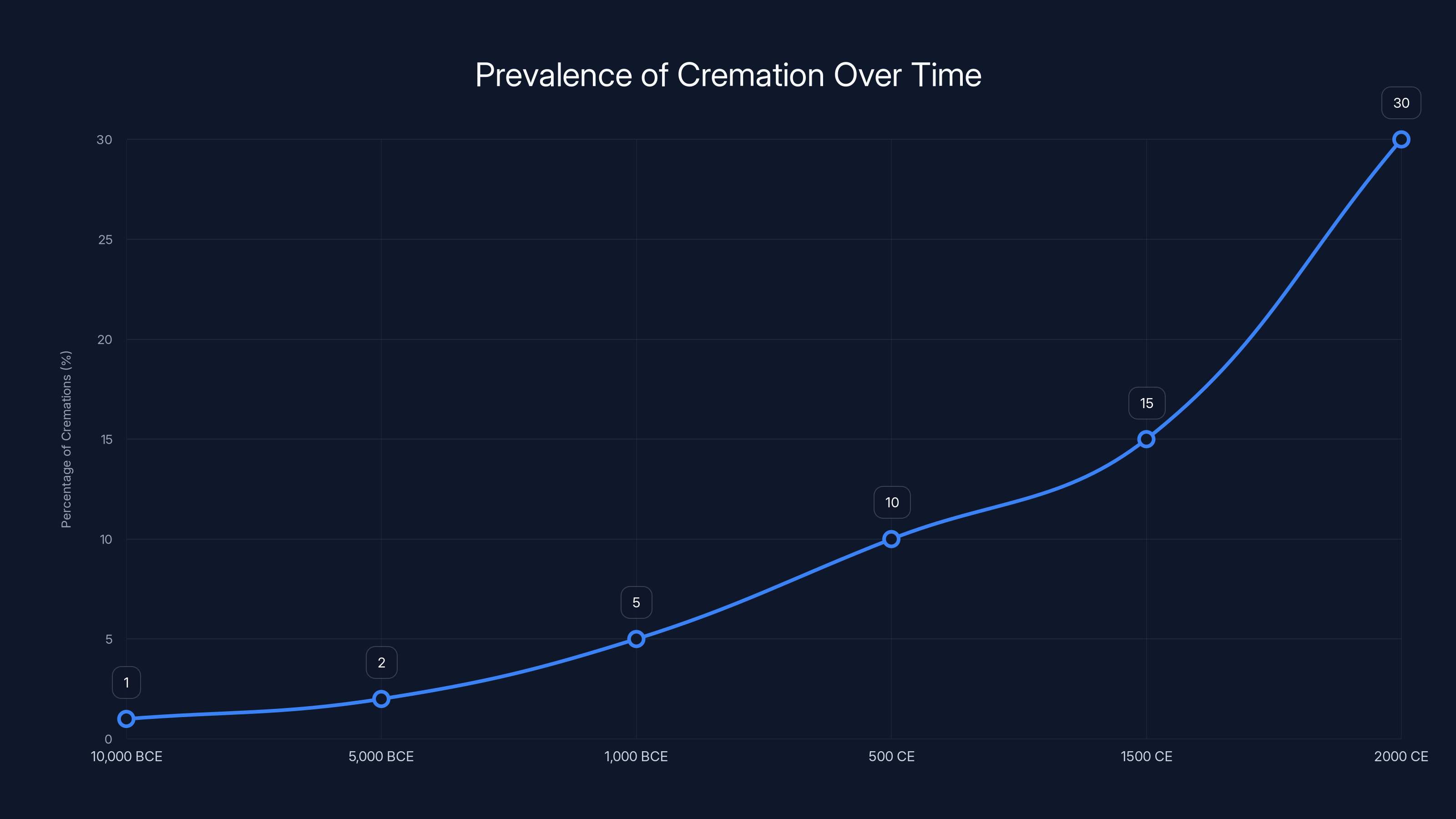

Cremation was extremely rare in prehistoric times due to resource demands. Its prevalence has gradually increased, particularly in modern times. (Estimated data)

Cremation Across Time: Why It Remained So Rare

Cremation is not a simple or economical funeral practice. This fundamental fact shapes the entire history of cremation across human societies and explains why it was so extraordinarily rare among hunter-gatherers for most of human prehistory.

Building a functional cremation pyre isn't like starting a campfire. It isn't about gathering a few dry branches and lighting kindling. A pyre capable of cremating a human body requires substantial fuel—at Hora-1, approximately 30 kilograms of carefully collected deadwood and grass. In regions like tropical Malawi, deadwood isn't always readily accessible. Grass must be gathered specifically. The entire fuel base must be assembled and arranged in a structure that maintains heat while allowing airflow.

Once constructed, the pyre requires constant tending. Temperature must be maintained above 500 degrees Celsius and typically above 800-900 degrees Celsius for complete cremation. This means someone must continuously feed fuel into the fire, regulate airflow, monitor the process, and maintain attention for hours. On a practical level, cremation demands multiple people contributing labor over an extended period—labor that can't be used for food procurement, shelter maintenance, or other community necessities.

From a resource perspective, cremation competes directly with other survival needs. Time spent maintaining a pyre is time not spent hunting, fishing, gathering, or making tools. Fuel collected for the dead is fuel not available for warmth, cooking, or defense. In subsistence economies operating at margins, this opportunity cost is significant. Inhumation, by contrast, requires digging a grave—labor-intensive but concentrated and completed relatively quickly. The deceased is then integrated into the landscape through decomposition, with minimal ongoing resource demand.

The global archaeological record before 5,000 years ago shows remarkably little evidence of cremation outside rare exceptions. Lake Mungo in Australia preserves evidence of burnt human remains dating back 40,000 years, but determining whether these represent actual pyre cremation or other forms of fire exposure remains unclear. Researchers found no definitive evidence of a constructed pyre at Lake Mungo, which makes the Hora-1 site genuinely unique as an intact, intact-pyre cremation from the deep past.

The Xaasaa Na' site in Alaska pushes back the date of confirmed pyre cremation to approximately 11,500 years ago, predating Hora-1 by roughly 2,000 years. However, the Xaasaa Na' cremation involved a child, suggesting potentially different social protocols for infant or juvenile death compared to adult burial practices. Whether adults were cremated at Xaasaa Na' remains unknown.

In Egypt, burnt human remains appear in the archaeological record around 7,500 years ago, but confirmed cremation burials don't appear until roughly 3,300 years ago. The early burnt remains might reflect natural fire exposure, ritual burning of specific body parts, or other mortuary practices distinguishing them from full-body cremation.

This scarcity of pre-Holocene cremation evidence contrasts sharply with the prevalence of cremation in later periods. Once Bronze Age civilizations emerged, cremation became increasingly common. Classical Greeks practiced cremation extensively. Romans cremated their dead and developed entire legal frameworks around cremation rights. Various Asian societies adopted cremation as a dominant mortuary practice. By historical times, cremation had become one of the world's most common funeral practices across multiple continents and cultures.

The shift from cremation's rarity to its commonality appears connected to social complexity, urban development, and the emergence of institutional religions that provided theological frameworks supporting cremation. But understanding what prompted communities to invest in cremation despite its inefficiency requires understanding the symbolic, spiritual, or social values that made the practice worth the cost.

The Pyre: Engineering a Prehistoric Cremation

Reconstructing the physical pyre from archaeological evidence requires combining direct material traces with experimental archaeology and ethnographic parallels. What emerges is a picture of remarkable sophistication.

The pyre at Hora-1 consisted of at least 30 kilograms of deadwood and grass. This represents a substantial gathering effort in itself. In tropical environments with seasonal variation, deadwood availability changes throughout the year. The choice to conduct cremation at a particular time might have been constrained by fuel availability, suggesting the ceremony occurred during seasons when sufficient fuel could be gathered without competing with other survival needs.

The arrangement of fuel suggests understanding of pyre architecture. Simply dumping 30 kilograms of wood into a heap wouldn't create temperatures sufficient for complete cremation. Effective pyres require layering—larger fuel at the base to establish a bed, progressively smaller pieces arranged to create airflow, gaps that allow heat to circulate while supporting the body being cremated.

Grass isn't typically used as primary pyre fuel in modern cremation contexts, but ethnographic examples show grass and straw can serve multiple functions in pyre construction. It fills gaps, improves airflow, provides quick-burning kindling to initiate combustion, and adds bulk to help maintain heat distribution. The inclusion of grass at Hora-1 suggests either practical knowledge of how different fuel types function in high-temperature burning or availability of grass as the primary accessible plant material.

Once the pyre was constructed, initiating combustion required fire. For pre-Holocene societies, obtaining fire meant either maintaining smoldering coals from a previous fire or using fire-starting techniques like friction-based methods (bow drill, hand drill) or percussion-based methods (striking rocks to create sparks). Either way, starting the pyre represented a committed action—you couldn't abort the process once combustion began and fuel was committed.

Temperature monitoring happened through observation rather than instrumentation. The cremation practitioners learned to recognize color changes in bone, timing of complete calcination, and visual cues indicating heat distribution throughout the pyre. The variation in burn intensity across different bones preserved at Hora-1 suggests the practitioners moved bones within the pyre, manipulated fuel distribution, and adjusted the burning process as it progressed.

Maintaining above-500-degree temperature required feeding fuel throughout the cremation process. The timing matters—adding fuel too early creates excessive heat that can warp bones; adding fuel too late allows temperature to drop. The practitioner maintaining the pyre needed experience or at minimum careful observation and responsiveness.

Complete cremation—where bones are reduced to ash and lose all visible organic material—requires the sustained attention represented by the Hora-1 pyre. Archaeological evidence suggests the cremation involved multiple people coordinating efforts, managing fuel, adjusting positioning, and maintaining attention across the entire process.

Evidence of Ritual: Stone Tools and Intentional Placement

Surrounding the cremation pyre, archaeologists discovered several stone points and evidence of flintknapping—the tool-making technique of striking stone to create sharp edges. These aren't random artifacts scattered near the cremation. They're concentrated within or immediately adjacent to the burning remains, suggesting deliberate placement contemporaneous with the cremation ceremony.

Stone tools at funeral sites can serve multiple functions. They might represent grave goods placed with the deceased to accompany them in the afterlife or beyond. They might have been tools used to prepare the body—the very implements employed for defleshing and skull removal left at the pyre to be burnt alongside the deceased. They might represent offerings or personal possessions of the mourners. They might constitute some form of symbolic gesture we no longer comprehend but can infer was meaningful.

The concentration and deliberate placement distinguish these tools from random debris. Flintknapping creates distinctive scatter patterns with unintended byproducts falling throughout an area where tool-making occurs. The stone points at Hora-1 appear to have been placed or positioned rather than scattered through tool-manufacturing activity elsewhere. This distinction suggests ritual intentionality rather than utilitarian accident.

The practice of placing objects with the cremated remains parallels practices documented across various cultures. Classical Greek burials included pottery vessels containing grave goods. Roman cremations included coins and valuable items. Scandinavian burials included weapons, jewelry, and tools positioned specifically with cremated remains. These practices reflect beliefs about the continuity of personal relationships across death, the provision of goods for the afterlife, or the resolution of obligations to the deceased.

At Hora-1, we lack the written records that allow us to specify exactly what placing stone tools meant to the community. But the evidence indicates they meant something—something sufficiently important to perform deliberately during a community funeral ceremony. This is the essence of ritual: actions performed for their symbolic significance rather than practical necessity.

Estimated data shows defleshing practices were most prevalent in Southeast Asia, followed by Scandinavia and Africa, indicating cultural variations in mortuary practices.

Community Mobilization: The Labor of Mourning

According to reconstruction based on experimental archaeology and ethnographic parallels, the cremation ceremony required meaningful community participation. Gathering 30 kilograms of fuel—deadwood and grass—isn't a solitary task easily accomplished by one person. In tropical environments where deadwood isn't superabundant and specialized knowledge might be required to identify the best fuel sources, this task likely involved multiple community members.

Construction of the pyre required coordination and knowledge. Arranging 30 kilograms of fuel into an effective pyre structure demands architectural understanding and likely required several people working simultaneously. Positioning the body atop the pyre required physical coordination and careful execution.

Maintaining the burning for the hours required for complete cremation couldn't be delegated to a single individual. Effective cremation requires constant attention, regular fuel additions, and monitoring of heat distribution. Multiple people rotating through the task of maintaining the fire would spread the labor burden while ensuring adequate attention to the process.

Cooling and collecting the cremated remains required careful work to preserve the fragmented bones. Ash is delicate material easily scattered by wind or disturbed by careless handling. Collecting and consolidating the remains likely required multiple careful workers and knowledge about how to handle cremated remains without further degradation.

This represents a substantial investment of community labor dedicated to honoring a single individual. In subsistence economies where labor is directly tied to survival resources, this investment implies the deceased held significant social value. She wasn't a marginal community member whose death was merely acknowledged. She was someone worth dedicating concentrated communal effort to honor.

The question of who participates in funeral ceremonies, who performs specific roles, and how that participation reflects social relationships is central to understanding community structure. At Hora-1, the evidence of coordinated, multi-person labor tells us this community could mobilize collective effort around shared purpose. They could suppress individual resource-gathering needs in favor of collective ritual obligation. These capabilities appear fundamental to complex human societies but are often assumed to require state-level organization or urban complexity. The evidence from Hora-1 demonstrates that hunter-gatherer communities possessed these organizational capabilities.

Defleshing and Secondary Mortuary Practice

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Hora-1 cremation is the evidence of deliberate defleshing before burning. Stone tool cut marks visible on the arm and leg bones indicate someone systematically removed flesh using carefully applied stone implements. This wasn't the casual degradation of decomposition or the random scarring of scavenger damage. This was controlled, methodical, and deliberate.

Defleshing practices appear sporadically in the archaeological record across various cultures and time periods. In Southeast Asia, some populations have practiced secondary mortuary practices where bodies are initially buried, allowed to decompose, then exhumed for defleshing and reburial. In Scandinavia, some burials show evidence of flesh removal. In various African contexts, ethnographic evidence documents practices where bones are handled, moved, and sometimes defleshed as part of extended mortuary sequences.

Why remove flesh before cremation? Several hypotheses emerge from the archaeological and ethnographic literature. Defleshing could facilitate cremation by reducing the amount of organic material needing incineration, potentially lowering fuel requirements. It could reflect beliefs about the relationship between body and spirit—the notion that separating flesh from bone achieves some spiritual transformation. It could constitute an act of secondary treatment signifying a transition in the deceased's status. It could represent a symbolic domestication of the corpse, transforming a recently-deceased person into handled remains requiring specific treatment.

The fact that only some individuals received defleshing suggests it wasn't standard practice but rather something reserved for particular people or particular circumstances. The Hora-1 site contains multiple inhumations with no apparent defleshing, suggesting this woman was singled out for treatment others didn't receive. Understanding why remains speculative, but the distinction is clear.

Defleshing also raises questions about gender, status, and social difference. Did women receive defleshing while men didn't, or vice versa? Did defleshing indicate high status as a costly, labor-intensive practice, or did it reflect something else entirely? Without additional sites showing similar patterns, we can't establish whether Hora-1 represents a unique idiosyncratic choice or a broader cultural practice specific to women, age groups, or particular social categories.

The Absent Head: Skull Removal and Its Significance

The cremation bed at Hora-1 contains bone fragments predominantly from arms and legs. The striking absence is the skull and teeth. Someone deliberately removed the head, and it either wasn't cremated with the body or was cremated separately somewhere else entirely.

Skull removal appears in various archaeological contexts and carries multiple interpretations depending on cultural context. In some societies, the skull was treated as sacred—a vessel of identity and thought that required special handling. Skulls appear in burials positioned prominently, sometimes separated from other skeletal material. In other contexts, skulls were removed to prevent the deceased from rising as malevolent spirits. In still others, skulls were kept as reliquaries, venerated objects continuing a relationship with the deceased.

The removal at Hora-1 could reflect any of these practices. If the community believed the head contained the seat of personhood or identity, separating it might have represented a ritual transformation—the removal of the individual in preparation for her cremation and transformation into ancestral status. If skull removal served protective purposes, preventing her from walking the world as a ghost, the practice reflects beliefs about the spiritual dangers posed by recently deceased individuals. If the skull was retained as a relic, it would continue a relationship with the woman even as her body was destroyed in cremation.

Secondary burial practices documented ethnographically show that separated bones, including skulls, are sometimes kept for extended periods, carried to ceremonial centers, consulted as oracular objects, or ultimately reburied in locations distinct from initial mortuary treatment. The Hora-1 skull might have experienced any of these trajectories.

The strategic separation of the head from the body raises questions about whether the cremation itself was truly whole-body cremation or whether it constituted one stage in a more extended mortuary sequence. Perhaps the cremation of the body represented one ceremony while the skull's treatment constituted another, separate ritual. This practice of dividing the mortuary process into stages, each with distinct locations, participants, or timing, appears in various ethnographic examples and might explain why the skull, which would likely survive cremation better than other bones, is entirely absent.

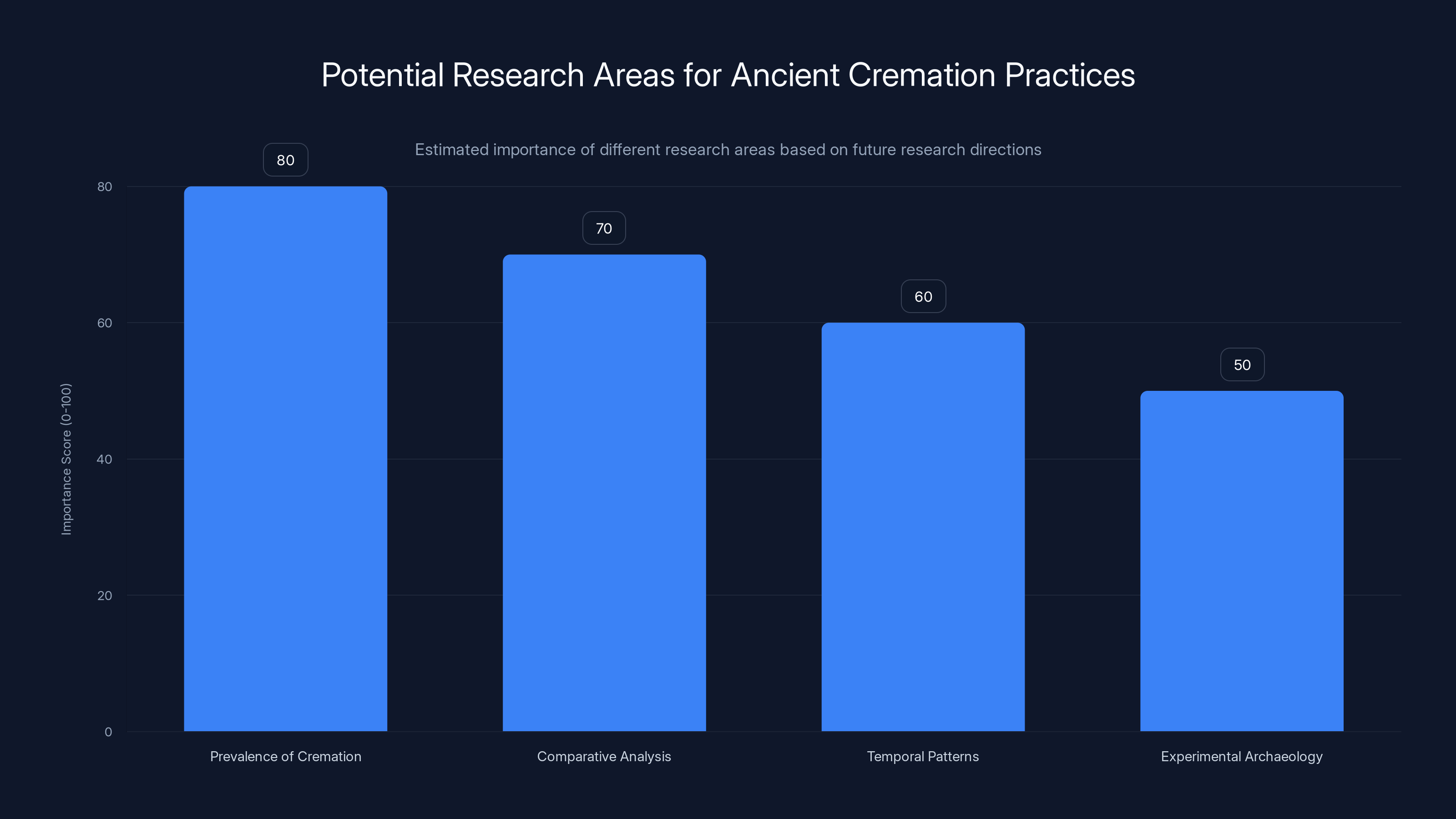

Estimated data suggests that understanding the prevalence of cremation in ancient Malawi is the most crucial research area, followed by comparative analysis and temporal patterns.

Persistent Places: The Continuing Significance of Hora-1

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the Hora-1 discovery is evidence that the site didn't become abandoned or taboo after the cremation. Instead, archaeological evidence indicates the community continued to use the exact spot where the cremation occurred for continued fire-making over the next several hundred years.

This persistent reoccupation and reuse of the cremation location tells a profound story about how ancient communities experienced place and memory. The location became what anthropologists call a "persistent place"—a location imbued with meaning through accumulated use, marked as significant, and deliberately revisited across generations.

The continued use wasn't random return to a convenient shelter. It was specifically concentrated in the same spot where the cremation had occurred, suggesting knowledge of the location's significance and deliberate choice to reunite with it repeatedly. This pattern appears in various ethnographic contexts where sacred sites, burial grounds, and memorial locations become focal points for recurrent community gathering and ritual reenactment.

What functions did these repeated fires serve? They might have constituted commemorative ceremonies, with communities gathering to honor the memory of the cremated woman. They might have been practical uses—the overhang provided a shelter, the location was suitable for fire-making regardless of its historical significance. They might have represented offerings or renewing of relationships with ancestors. They might have been protective practices, keeping the location in active use and preventing it from becoming a place of danger or spiritual vulnerability.

The evidence suggests the cremation established a significant place in the community's landscape—a location that anchored memory, identity, and continued relationship with the past. Subsequent fire use kept the location alive in communal practice rather than allowing it to fade into history.

This pattern has profound implications for understanding how hunter-gatherer societies constructed meaning and maintained social identity. Rather than being transient, rootless populations with minimal connection to place, these communities demonstrated sophisticated place-based knowledge, meaningful attachment to specific locations, and practices designed to preserve and transmit memory across generations. The Hora-1 site represents one archaeological expression of a common human tendency to mark significant experiences in the landscape and return to them repeatedly.

Why This Woman? The Unanswerable Question

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Hora-1 discovery is its fundamental mystery: why was this woman singled out for cremation when other individuals buried at the site were interred through conventional inhumation?

The archaeological record cannot answer this question directly. Status, achievements, spiritual power, or particular circumstances known to her community leave no tangible evidence that survives millennia. Her name is gone. Her specific role or relationships are unknowable. Her life experiences exist only as fragmentary evidence in skeletal remains.

Yet the question itself is important. The distinction between her treatment and others' treatment indicates the community made decisions about funeral practices based on something—some quality or characteristic that mattered to them. Understanding that decisions were made is valuable even if understanding exactly what prompted those decisions remains forever beyond our reach.

Led by researchers from Yale University and the University of Oklahoma, the research team proposes several hypotheses. Perhaps she held special spiritual status—a healer, visionary, or person understood to possess supernatural power. Perhaps she died under unusual circumstances requiring special treatment. Perhaps she came from outside the community and received different funeral practices reflecting her outsider status. Perhaps she belonged to a particular age category, family, or social rank where cremation was the standard practice. Perhaps her death occurred during a particular season or at a particular moment in community history that made cremation appropriate.

All of these remain speculative. But the very fact of her distinctive treatment tells us she mattered enough to warrant extraordinary effort, special ritual, and community mobilization. In a subsistence economy where resources were constrained and labor was precious, cremating someone demanded justification. Something about this woman made the community judge that justification worthwhile.

For contemporary researchers, this recognition—that ancient communities made deliberate choices about how to treat their dead based on meaningful social distinctions—fundamentally reshapes how we interpret the archaeological record. We're not simply observing random variation in burial practices. We're observing the material expression of meaningful social relationships and community decision-making.

Community-Scale Operations in Hunter-Gatherer Societies

The cremation ceremony at Hora-1 required organization, coordination, and resource mobilization on a scale that earlier models of hunter-gatherer society often underestimated. For decades, anthropological literature portrayed hunter-gatherers as operating in small, egalitarian groups with minimal specialization and weak institutional structures. Complex ceremonies, coordinated labor efforts, and resource investments were assumed to require state-level organization or at minimum sedentary village communities with permanent leadership structures.

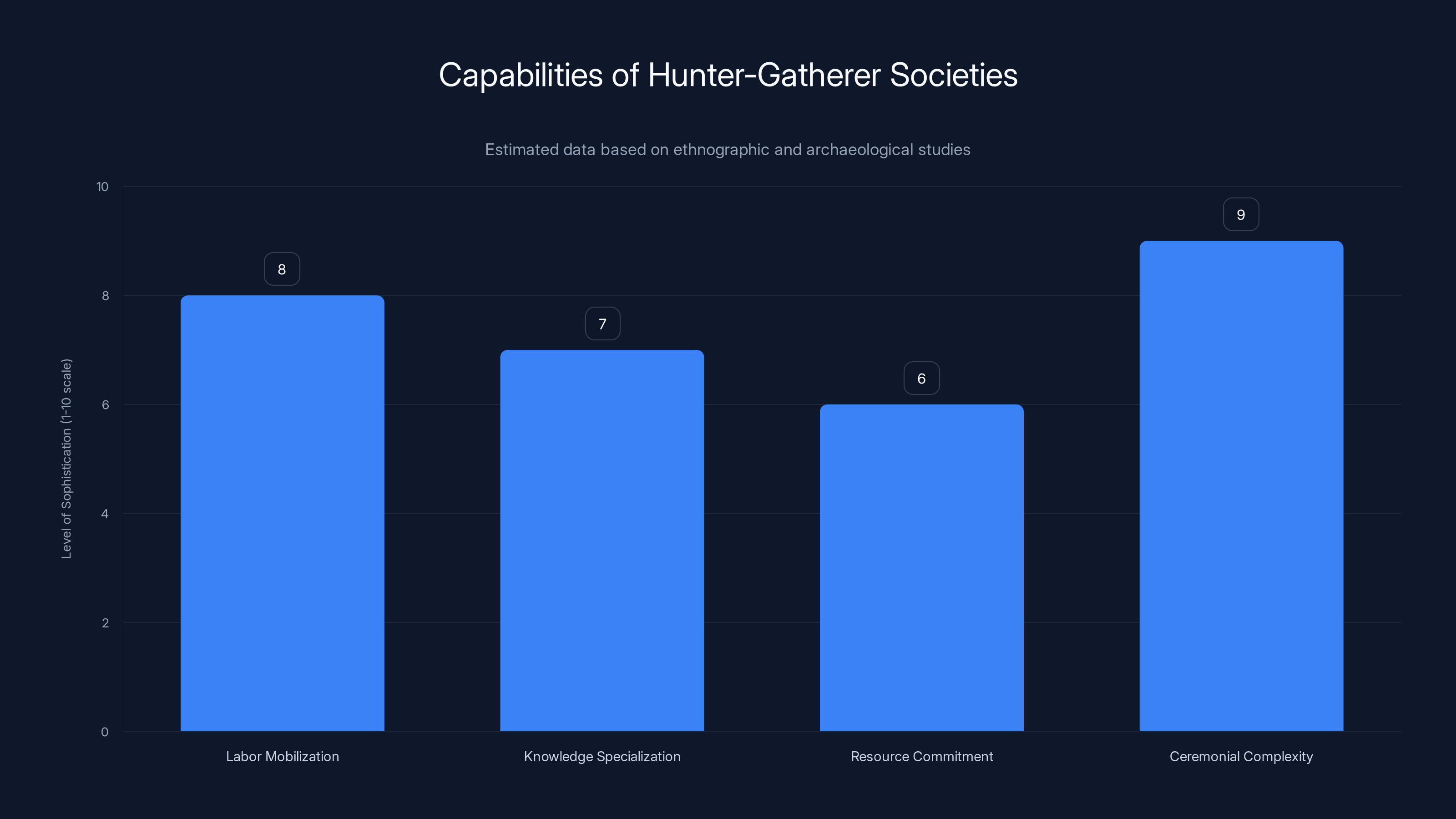

The archaeological evidence from Hora-1 challenges these assumptions. Here was a community capable of mobilizing labor for a purpose unrelated to immediate survival. Here was a ceremony requiring knowledge specialization—understanding pyre construction, temperature management, tool-making. Here was resource commitment to a single individual requiring collective restraint from individual food-procurement activities.

Recent ethnographic work on contemporary hunter-gatherer societies has already documented these capabilities. Societies like the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, the hunter-gatherers of the Pacific Northwest Coast, and various African groups demonstrate sophisticated social organization, elaborate ceremonialism, and significant resource specialization despite subsistence-level economies. Archaeological evidence increasingly confirms these patterns extend deep into prehistory.

The implication is that complexity, organization, and institutional sophistication didn't suddenly emerge with agriculture and civilization. They represent human capabilities that can manifest under various economic conditions, including subsistence-level hunting and gathering. The question shifts from "did hunter-gatherers have the capacity for complex organization" to "what conditions and contexts prompted that capacity to manifest in particular ways."

The Hora-1 cremation ceremony, with its resource requirements and coordinated execution, suggests that significant community occasions generated the social space for mobilizing collective effort. Funeral ceremonies, given their emotional weight and meaning, might have been precisely the context where communities invested in complexity and coordination otherwise reserved for ordinary subsistence activities.

Estimated data suggests that skull removal practices are varied, with sacred vessel and relic keeping interpretations being common. Estimated data.

Mortuary Practice and Social Memory

Mortuary practices across human societies serve functions far beyond practical disposal of the dead. They constitute performances of memory, statements about social relationships, expressions of belief systems, and mechanisms for transmitting cultural knowledge across generations.

At Hora-1, multiple aspects of the cremation practice suggest deliberate deployment of the funeral as an occasion for memory-making. The defleshing, skull removal, bone arrangement, and ritual positioning of stone tools—these constitute a sequence of actions each carrying potential symbolic weight. The gathering of community members, the collective labor, the concentrated attention on a single individual—these transform a private loss into a public ceremony.

The subsequent repeated use of the cremation location perpetuates the memory function. Each time the community returned to the spot, they engaged with the space where the woman had been transformed through cremation. The location became a node in the landscape where memory resided, where the past could be actively engaged rather than passively remembered.

This pattern appears universally in human societies: the tendency to transform death into ceremony, to extract meaning from loss, to anchor memory in material locations and repetitive practices. What makes Hora-1 significant is the depth of evidence demonstrating this pattern extends at least 9,500 years into the African past and appeared among communities whose material culture was relatively simple by later standards but whose ceremonial sophistication was remarkable.

Comparative Context: Cremation Across Africa and the World

Placing Hora-1 within the broader global context of prehistoric cremation practices helps illuminate its significance. The patterns that emerge suggest cremation followed particular trajectories in different regions and that these trajectories were shaped by cultural factors as much as practical constraints.

In Australia, the Lake Mungo remains show evidence of heat exposure potentially indicating cremation, but the absence of a confirmed pyre structure leaves ambiguity. Dating back 40,000 years, these remains suggest early awareness of and experimentation with fire exposure of the dead. However, whether this constituted intentional cremation or incidental burning remains unclear.

In North America, the Xaasaa Na' site in Alaska dates to approximately 11,500 years ago and provides clear evidence of a cremation pyre, predating Hora-1 by about 2,000 years. The individual cremated was a child, raising questions about whether children and adults received different treatment and whether cremation was more common for certain age categories.

In the Mediterranean, early evidence of cremation appears later. Egypt shows burnt remains around 7,500 years ago, but these might not represent deliberate cremation. Confirmed cremation burials in Egypt don't appear until around 3,300 years ago, much later than Hora-1.

Classical Greece and Rome adopted cremation extensively, though not exclusively. Archaeological contexts show tremendous variation in whether individuals were cremated or inhumed, suggesting factors like status, age, gender, or family practice influenced funeral choices. By classical times, cremation had become institutionalized as a standard practice among certain populations.

In Asia, various societies adopted cremation, particularly in regions where Hindu, Buddhist, and Zoroastrian beliefs provided religious frameworks supporting the practice. Cremation became integrated into theological worldviews, creating cultural systems that perpetuated and reinforced the practice.

What emerges from this comparative perspective is that cremation's prevalence increased over time and became integrated into cultural systems once societies developed ideologies supporting it. Hora-1 appears as an early example of communities embracing cremation despite its inefficiency, investing significant resources in the practice for reasons that appear fundamentally cultural and spiritual rather than practical.

Dating and Archaeological Methods

Determining that the Hora-1 cremation occurred 9,500 years ago required sophisticated archaeological and scientific methodologies. The radiocarbon dating that established this chronology represents just one component of the analysis; equally important were microscopic and spectroscopic examinations that revealed the sequence of construction and burning.

Radiocarbon dating works by measuring the decay of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope incorporated into living organisms through consumption of atmospheric carbon. After death, the isotope decays at a predictable rate. By measuring the remaining carbon-14 content, scientists can calculate how long ago the organism died. For Hora-1, charcoal samples from the cremation pyre were dated, yielding results consistent across multiple samples and indicating high confidence in the 9,500-year chronology.

The margin of error in radiocarbon dating typically runs from 50 to 200 years, meaning the actual cremation could have occurred anytime within a range surrounding the stated date. At 9,500 years ago, this represents remarkable precision—we can place the event to within a narrow window despite the vast span of time.

Microscopic analysis of sediment layers revealed the stratigraphy—the sequence in which layers were deposited—showing which materials were contemporary with the cremation and which were deposited before or after. Color changes in ash, variations in charcoal concentration, and transitions between different sediment types created a readable record of the cremation sequence.

Spectroscopic techniques identified chemical signatures of burning. Different heating temperatures create different mineral transformations in bone and surrounding sediment, allowing researchers to estimate the temperatures achieved and the distribution of heat across the cremation area. These analyses confirmed that sustained high temperatures were achieved, consistent with intentional cremation rather than accidental exposure to fire.

The combination of these methods created a multidimensional analysis far richer than radiocarbon dating alone could provide. The result was not just a date but a detailed reconstruction of how and when the event occurred.

Estimated data suggests hunter-gatherer societies had significant capabilities in labor mobilization, knowledge specialization, resource commitment, and ceremonial complexity, challenging previous assumptions about their organizational structures.

Regional Context: Malawi and the Broader African Picture

The Hora-1 site sits in modern-day Malawi, a region with deep archaeological history extending well beyond the cremation's 9,500-year span. Understanding the broader context of Malawi's archaeology helps place Hora-1 within regional patterns of human settlement, adaptation, and cultural development.

Malawi's archaeological record shows human occupation extending back tens of thousands of years. Early stone tools evidence the presence of hunter-gatherer populations adapting to the region's diverse environments. The Lake Malawi basin provided abundant aquatic resources including fish, freshwater mollusks, and waterfowl. Surrounding woodlands and grasslands supported terrestrial hunting and gathering.

The Hora-1 site itself demonstrates consistent occupation across millennia. The uncremated burials interred between 8,000 and 16,000 years ago show that the site functioned as a burial ground for extended periods. The shelter location offered protection from weather while the location within the landscape held meaning for the community, making it a place where death rituals were repeatedly enacted.

The broader African archaeological record from this period shows tremendous diversity in burial practices. Inhumation was widespread, with bodies flexed or extended depending on cultural practice. Some burials included grave goods—tools, ornaments, or other objects placed with the deceased. Some burial sites received single interments while others accumulated remains of multiple individuals across time.

Cremation remained unusual in this context, which emphasizes the distinctiveness of Hora-1. The fact that cremation appeared at a site with multiple inhumations and then apparently wasn't repeated at that location during subsequent centuries suggests it constituted a one-time choice specific to this woman's funeral rather than a standard cultural practice.

Ritual Sophistication and Symbolic Meaning

The Hora-1 cremation ceremony, reconstructed from archaeological evidence, demonstrates ritual sophistication that challenges assumptions about hunter-gatherer cultures. The practice involved multiple stages, each potentially laden with symbolic meaning: defleshing, skull removal, careful body positioning, pyre construction, temperature management, and subsequent bone curation.

Each stage required decisions. The choice to deflesk before cremation. The choice to remove the skull. The choice to position limbs in a particular configuration. The choice to place stone tools at the pyre. These decisions, taken together, demonstrate a complex choreography of action performed for reasons beyond practical necessity.

Ritual, by definition, consists of actions performed according to prescribed form, often laden with symbolic significance. The Hora-1 evidence shows ritual behavior clearly—the stylized, intentional, meaningful handling of the dead. This ritual sophistication doesn't depend on written records, institutional complexity, or state-level organization. It emerges from community traditions, transmitted knowledge, and shared meanings that existed among the living long before writing systems developed.

The symbolic meanings embedded in the Hora-1 cremation practice are forever inaccessible to us. We cannot know what the community believed about death, the afterlife, or the nature of personhood and identity. We cannot know whether defleshing reflected spiritual beliefs, practical knowledge, or both. We cannot determine why this particular woman was selected for cremation. These meanings were held in the community's understanding during and immediately after the ceremony, and they have been lost in the centuries since.

What we can recognize is that meaning was being made—that the community engaged in actions performed because they mattered, not merely because they accomplished practical ends. This recognition matters because it restores a fuller picture of human experience in the past, acknowledging that spiritual, emotional, and symbolic dimensions of human life have deep historical roots.

Implications for Understanding Ancient Communities

The discovery of the Hora-1 cremation pyre reshapes how we interpret ancient African societies and hunter-gatherer communities more broadly. Several implications emerge from the evidence.

First, communities without written records, centralized authority, or monumental architecture nonetheless engaged in complex, coordinated, meaningful ritual practices. The cremation ceremony required planning, resource allocation, and coordinated labor—capabilities we often associate with complex societies but which clearly existed among small-scale communities.

Second, burial practices and mortuary rituals served as occasions for mobilizing community effort, enacting social relationships, and creating meaning. The funeral ceremony was not incidental but rather a major social occasion worthy of significant resource investment. This pattern appears cross-culturally and deep in human history.

Third, places acquired meaning through use and repetition. The Hora-1 location became significant through the cremation ceremony and retained significance through subsequent reoccupation and repeated fire use. This place-based memory and meaning-making appears to be a fundamental human capacity, not a development of later complex societies.

Fourth, we have consistently underestimated the sophistication of ancient and ethnographically-documented hunter-gatherer societies. Material simplicity in tool kits and settlement patterns masks social complexity, organizational capability, and ritual sophistication. The Hora-1 evidence supports what ethnographic and recent archaeological work has increasingly demonstrated: that social and cultural sophistication can manifest in societies with minimal material culture.

Fifth, diversity in funeral practices even within single sites indicates that communities made meaningful distinctions among individuals when determining how to treat the dead. These distinctions likely reflected factors like status, gender, age, or particular achievements. Understanding ancient social differentiation requires attending to these distinctive practices and asking what made them appropriate for some individuals but not others.

Future Research and Unanswered Questions

The Hora-1 discovery raises as many questions as it answers, pointing toward future research directions. Several key areas warrant continued investigation.

Understanding the broader prevalence of cremation in ancient Malawi requires additional excavation and research at other sites. Is Hora-1 unique, or do other sites contain evidence of cremation practices that haven't yet been recognized or reported? Systematic research could determine whether cremation was practiced regularly in the region or whether Hora-1 represents a singular event.

Determining why this woman was cremated requires comparative analysis. If additional cremation burials are discovered, examining who was cremated—age, gender, potentially status markers in skeletal or burial evidence—could reveal patterns. Do women more commonly receive cremation than men? Do particular age groups? Do certain burial locations contain cremation preferentially?

Understanding the temporal pattern of cremation across Africa requires regional surveys. Horton-Radi earlier documented Egypt's cremation timeline; similar systematic research in other regions could establish whether cremation appeared in clusters (suggesting cultural diffusion) or independently in different locations (suggesting parallel cultural invention).

Experimental archaeology examining pyre construction and management could provide additional insight into the practical aspects of the cremation ceremony. How much time does cremation actually require? What temperatures are achieved with different fuel sources? What variations in burning temperature occur across different positions in the pyre? How much attention is required to successfully cremate a body? These questions, addressable through controlled experimentation, could illuminate what the Hora-1 practitioners needed to know to successfully complete the ceremony.

Understanding the broader mortuary practices in Malawi during the relevant period requires more complete excavation and analysis of burial sites. The Hora-1 uncremated burials need more detailed study. What patterns emerge in how bodies were positioned, treated, and associated with grave goods? How might these patterns inform interpretation of the cremation?

The Broader Human Story

Beyond the specific facts about Hora-1—its date, its location, the specific details of the cremation practice—the discovery tells a broader story about human nature that echoes across time.

The story is this: at every point in human history, including the deep past when writing didn't exist, when monumental architecture hadn't been invented, when communities numbered in the dozens rather than thousands, humans engaged in practices that served no practical survival function but which mattered deeply. Humans made meaning through ritual, community, and the treatment of the dead. Humans invested resources and effort into honoring individuals, expressing beliefs, and creating connections that transcended simple material exchange.

The woman cremated at Hora-1 mattered enough to her community that they gathered, mobilized labor, and invested resources in a ceremony honoring her death. She mattered enough that how she was treated—the specific handling of her bones, the removal of her skull, the careful positioning of her limbs—carried significance. She mattered enough that her cremation location became a landmark in the landscape, revisited repeatedly across subsequent generations.

We don't know her name. We don't know her achievements. We don't know what she meant to her community beyond the fact that she warranted an extraordinary funeral. But the evidence of her cremation ceremony preserves something essential about her—that she mattered, that she was mourned, that her death was marked as significant. Across 9,500 years, that recognition echoes forward to us.

The archaeological evidence from Hora-1 reminds us that the deep human past was inhabited by communities as emotionally and socially complex as ourselves. The pyre they constructed, the bones they handled, the location they continued to revisit—all speak to fundamental human needs to create meaning, maintain community, and preserve memory. These needs appear in the archaeological record not as recent developments but as ancient features of human experience.

In that sense, the Hora-1 cremation pyre connects us across millennia to people whose voices are lost but whose actions remain. They performed rituals that mattered to them. They mourned their dead. They created places that held meaning. They made their world through actions and meanings that can never be fully recovered but which can be partially understood, deeply respected, and recognized as expressions of humanity as old as our species itself.

FAQ

What is the Hora-1 site and why is it significant?

Hora-1 is an archaeological site at the base of Mount Hora in Malawi containing Africa's oldest known cremation pyre, dated to approximately 9,500 years ago. The site is significant because it demonstrates that ancient hunter-gatherer communities engaged in complex, resource-intensive rituals and possessed sophisticated knowledge about fire management and mortuary practices much earlier than previously documented.

How was the cremation dated so precisely to 9,500 years ago?

Archaeologists used radiocarbon dating of charcoal samples from the pyre, measuring the decay of carbon-14 to determine how long ago the cremation occurred. This scientific method provided precise dating with a margin of error of roughly 100-200 years. Microscopic and spectroscopic analysis of sediment layers confirmed the findings by revealing the physical sequence of pyre construction and burning.

Why is cremation so rare among hunter-gatherer societies?

Cremation is extremely resource-intensive, requiring approximately 30 kilograms of fuel and many hours of careful attention to maintain the high temperatures needed to cremate a body. In subsistence economies where labor directly relates to survival and food acquisition, investing these resources in funeral practice was economically costly and therefore unusual. Inhumation required less labor and fewer resources, making it the more practical option.

What does the evidence of bone defleshing tell us about the cremation ceremony?

The cut marks on arm and leg bones indicate someone deliberately removed flesh using stone tools before cremation. This suggests the cremation was a choreographed, multi-stage ritual rather than a simple burning. The defleshing might reflect beliefs about death and spiritual transformation, practical facilitation of cremation, or practices of bone handling documented in various cultures where bones were handled and moved after initial mortuary treatment.

Why was the woman's skull removed and where did it go?

The complete absence of skull bones and teeth in the cremation bed indicates someone deliberately removed the head before, during, or shortly after cremation. Archaeological evidence cannot determine whether the skull was cremated separately, retained as a sacred relic, or treated through some other mortuary practice. In various cultures, skulls received special treatment reflecting their spiritual significance as vessels of identity or sources of supernatural power.

What do the stone tools found at the cremation site tell us?

Several stone points were discovered concentrated within or immediately adjacent to the cremation remains, suggesting deliberate placement rather than random debris. These tools might represent grave goods accompanying the deceased, implements used during the cremation ceremony itself, offerings from mourners, or symbolic objects with meanings now lost to time. Their deliberate placement indicates ritual significance and intentional decision-making about the ceremony's conduct.

How did the community continue to use the Hora-1 site after the cremation?

Archaeological evidence shows that the community made fires in the same location where the cremation had occurred repeatedly over the next several hundred years. This persistent reuse of the cremation location suggests it became a meaningful place in the landscape, a focal point for memory and community gathering. The practice reflects how ancient communities created lasting significance through repeated engagement with particular locations.

What can we infer about the community's social organization based on the cremation ceremony?

The resources required for cremation—gathering 30 kilograms of fuel and maintaining the fire for many hours—indicate the community could mobilize collective labor for non-subsistence purposes. This demonstrates social capabilities often assumed to require state-level organization but which clearly existed among small-scale hunter-gatherer communities. It suggests the community could suppress individual needs in favor of collective ritual obligation and could maintain knowledge about complex processes like fire management and pyre construction.

Why was only this one woman cremated while others at the site were buried through inhumation?

This remains one of archaeology's unanswerable questions. The evidence demonstrates that this woman received treatment others didn't, indicating something about her warranted special handling. Whether this reflected status, gender-specific practices, unusual circumstances of death, or factors now completely lost to time, we cannot determine. The question itself is valuable because it highlights that ancient communities made meaningful social distinctions about how to treat their dead.

How does the Hora-1 discovery change our understanding of ancient Africa?

Hora-1 demonstrates that African communities 9,500 years ago engaged in sophisticated ritual practices requiring planning, knowledge specialization, and resource commitment. It challenges the assumption that ritual sophistication and community organization are recent developments or products of complex civilization. It shows that the African archaeological record contains evidence of cultural complexity and meaningful social practices among communities whose material culture was relatively simple by later standards.

The Enduring Legacy

Nine thousand five hundred years is a span so vast it strains human comprehension. The woman cremated at Hora-1 died when the last ice age was already ancient history, when modern humans had dispersed across every continent, when agriculture was still thousands of years in the future for this part of Africa. She lived and died in a completely different world—warmer, less populated, with different animal and plant communities.

Yet the evidence of her cremation ceremony speaks directly to us across that immense span of time. The pyre that was built, the bones that were handled, the location that was revisited—all tell a story about how human communities find meaning in loss, how we mark what matters, how we create connections across generations.

The Hora-1 cremation reminds us that the essential aspects of human experience—community, ritual, meaning-making, the grief of loss, the desire to honor the dead—have deep historical roots. These are not recent inventions of complex civilization but rather fundamental features of human existence that appear in the archaeological record at the earliest times we can detect.

As we continue to excavate, analyze, and interpret the African archaeological record, discoveries like Hora-1 will continue to surprise us, forcing us to expand our understanding of what ancient communities accomplished, what they valued, and how they experienced the world. Each discovery expands our appreciation for the depth and complexity of human history and reminds us that we are heirs to traditions of meaning-making stretching back deep into the past.

The woman at Hora-1 is gone, her name lost, her specific story unknowable. But the ceremony that honored her death survives in the archaeological record, visible to those who know how to read it. That survival is its own kind of memorial—a testament to how human efforts to create meaning and honor the dead can echo across millennia.

Key Takeaways

- The Hora-1 site in Malawi contains Africa's oldest confirmed cremation pyre, dated to 9,500 years ago through radiocarbon analysis, pushing back the timeline of African cremation practices by approximately 2,500 years

- Archaeological evidence of deliberate bone defleshing, skull removal, careful body positioning, and ritual stone placement indicates the cremation ceremony was choreographed and laden with symbolic meaning rather than a simple practical disposal

- Building and maintaining the cremation pyre required approximately 30 kilograms of fuel and many hours of careful fire management, demonstrating that ancient hunter-gatherer communities could mobilize significant collective labor for ritual purposes

- The community continued using the cremation location for repeated fire-making over subsequent centuries, establishing it as a persistent place of memory and spiritual significance rather than abandoning it after the ceremony

- The discovery challenges assumptions that ritual sophistication and community organization required state-level complexity, showing these capabilities existed among small-scale societies and appear deeply rooted in human cultural practice

Related Articles

- January TV Sales 2025: Complete Guide to Up to £400 Off Leading Models

- Lucid Motors Production 2025: From Crisis to 18K EVs [2026]

- Best AirPods Deals January 2026: Save on Pro 3, Max & AirPods 4

- EU Tech Enforcement 2026: What Trump's Retaliation Threats Mean [2025]

- DJI Mini 4K Drone Complete Guide for Beginners [2025]

- HBO Max's The Pitt Season 2 Review: Why the Formula Still Works [2025]

![Earliest African Cremation: 9,500 Years of Ritual and Community [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/earliest-african-cremation-9-500-years-of-ritual-and-communi/image-1-1767634675953.jpg)