Earth's Environmental Tipping Point: What You Need to Know [2025]

Something fundamental is breaking. Not metaphorically. Right now.

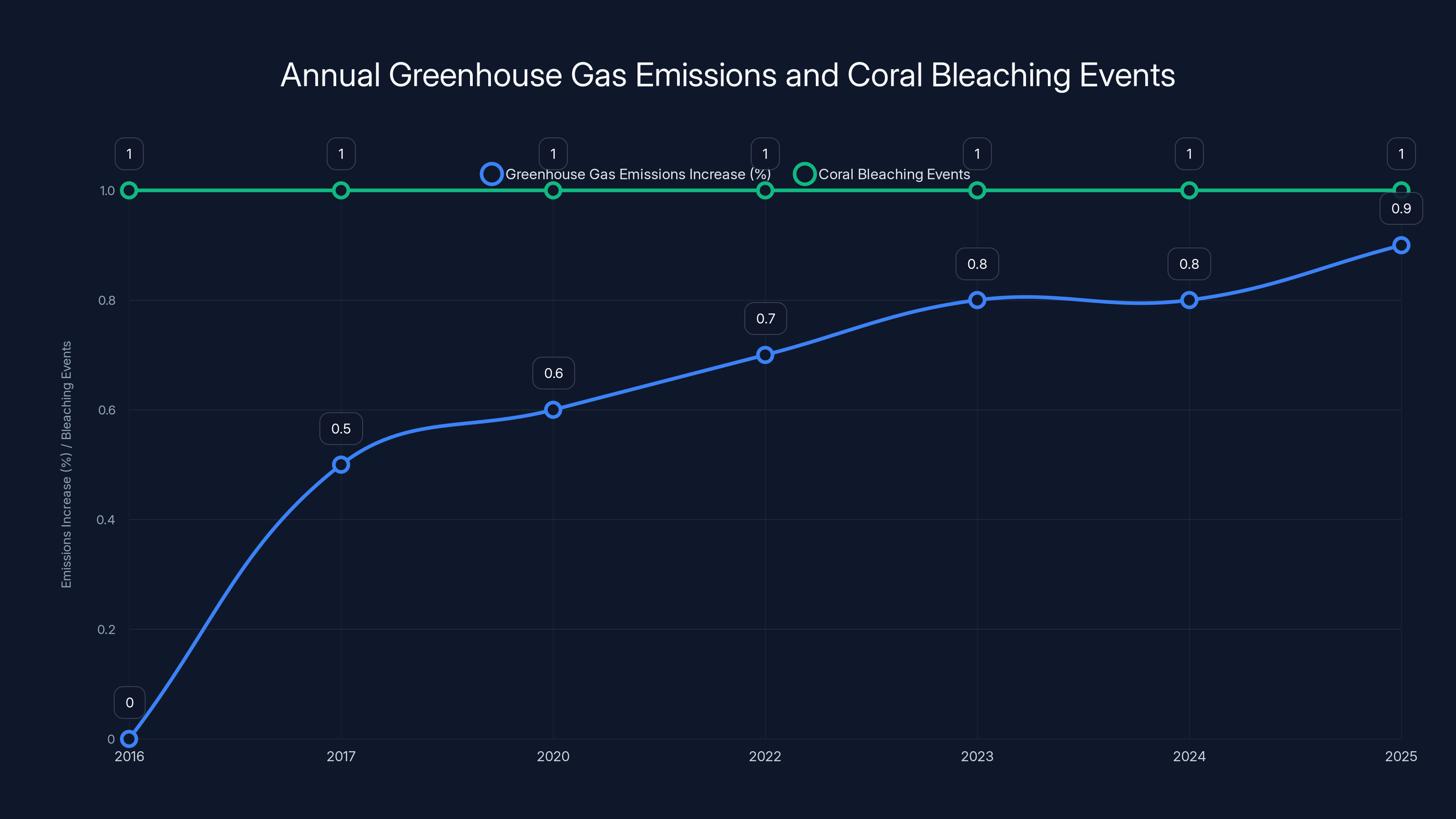

In 2024, humanity pumped more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere than any single year in recorded history. The year before was worse than the year before that. We're not slowing down—we're accelerating, even as every scientific body on Earth tells us we need to be doing the opposite.

The math is brutal. Emissions should have peaked around 2020 according to the Paris Agreement targets. Instead, they climbed another 0.8 percent in 2024. Small percentage. Catastrophic trajectory.

But here's what keeps climate scientists up at night—and what you should understand: it's not the steady climb that's the problem. It's the cliffs.

Planet Earth has thresholds. Cross them, and the system doesn't degrade gradually. It flips. Irreversibly. One moment you have a functioning system that can bounce back. The next moment you have a dead one. No recovery. No second chances.

We're not talking about theoretical future disasters anymore. We're watching it happen in real time. The Great Barrier Reef, which survived for millennia, is collapsing in front of us. Tropical coral reefs worldwide are bleaching at rates never seen before. These aren't warning signs of what's coming. They're proof that it's already here.

TL; DR

- Record emissions: Humanity emitted more greenhouse gases in 2024 than any previous year, with a 0.8% increase from 2023

- Tipping points are real: At least 6 of 9 planetary boundaries have been exceeded, triggering cascading collapse risks

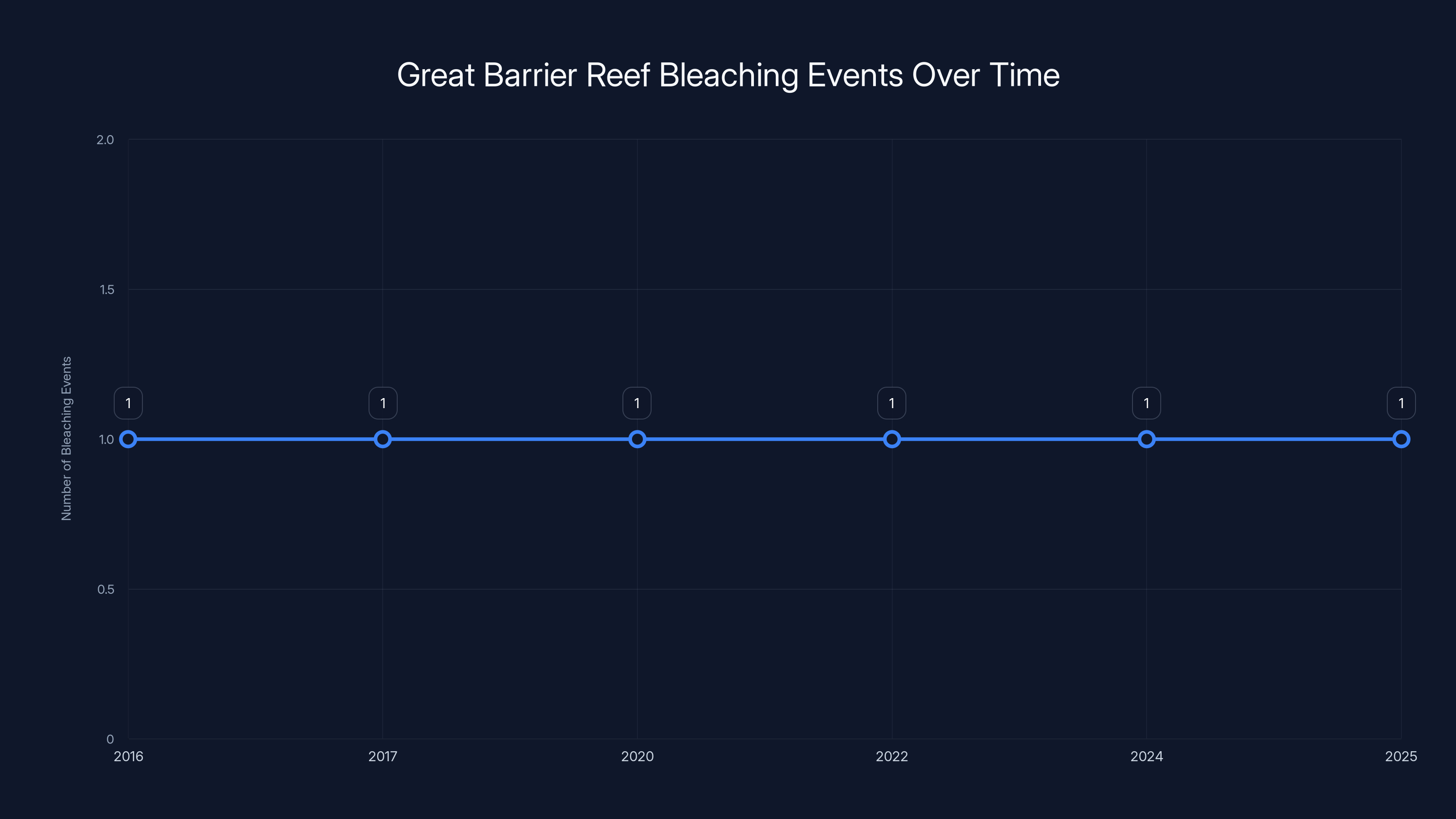

- Coral reefs are dying: The Great Barrier Reef experienced mass bleaching events in 2025, 2024, 2022, 2020, 2017, and 2016—leaving almost no time for recovery

- Global bleaching confirmed: For only the fourth time in history, the entire world's oceans experienced simultaneous coral bleaching in 2023-24

- Urgent action required: Global fossil fuel emissions must drop over 5% annually to reach zero by 2050, even then, some ecosystems may not survive

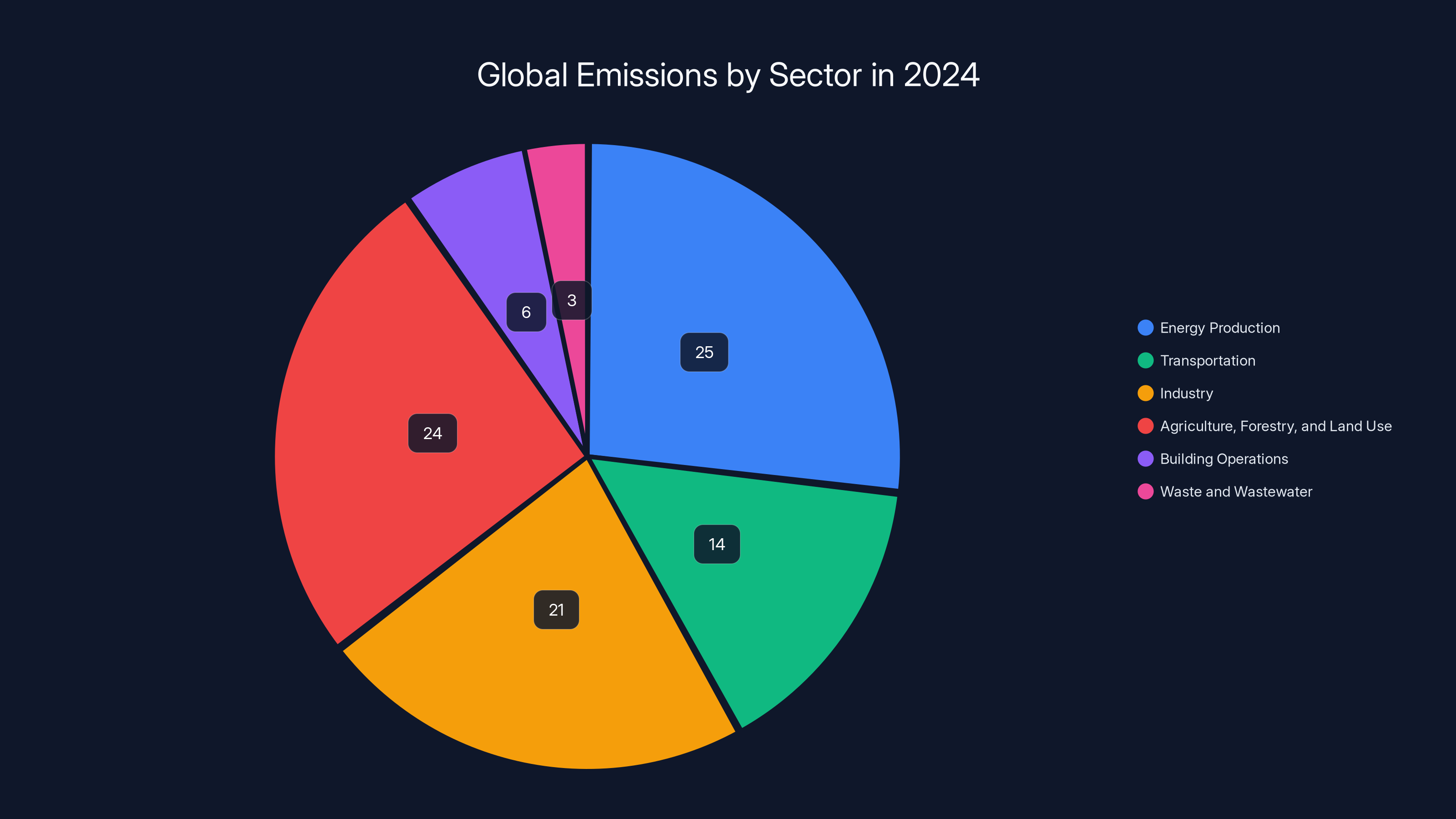

Energy production is the largest contributor to global emissions, accounting for 25% of the total in 2024. Despite efforts to increase renewable energy, emissions continue to rise due to ongoing fossil fuel consumption.

Understanding Planetary Tipping Points

A tipping point isn't a gradual slope. It's a cliff.

Imagine a marble rolling across a table. As long as the table is flat, you can predict where the marble goes. You can slow it down. You can change its course. But once that marble reaches the edge—once it tips—there's no pulling it back. Gravity takes over. Physics becomes destiny.

Planetary tipping points work the same way, except the marble is Earth's climate system and the table is everything we depend on to survive.

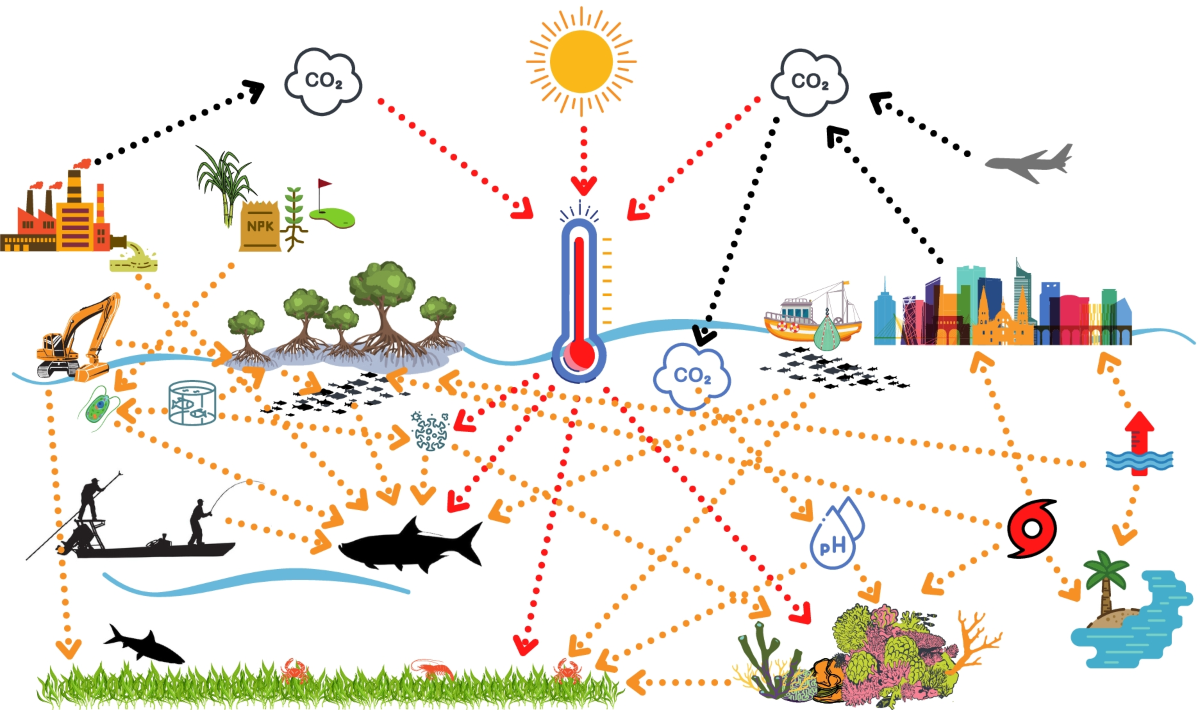

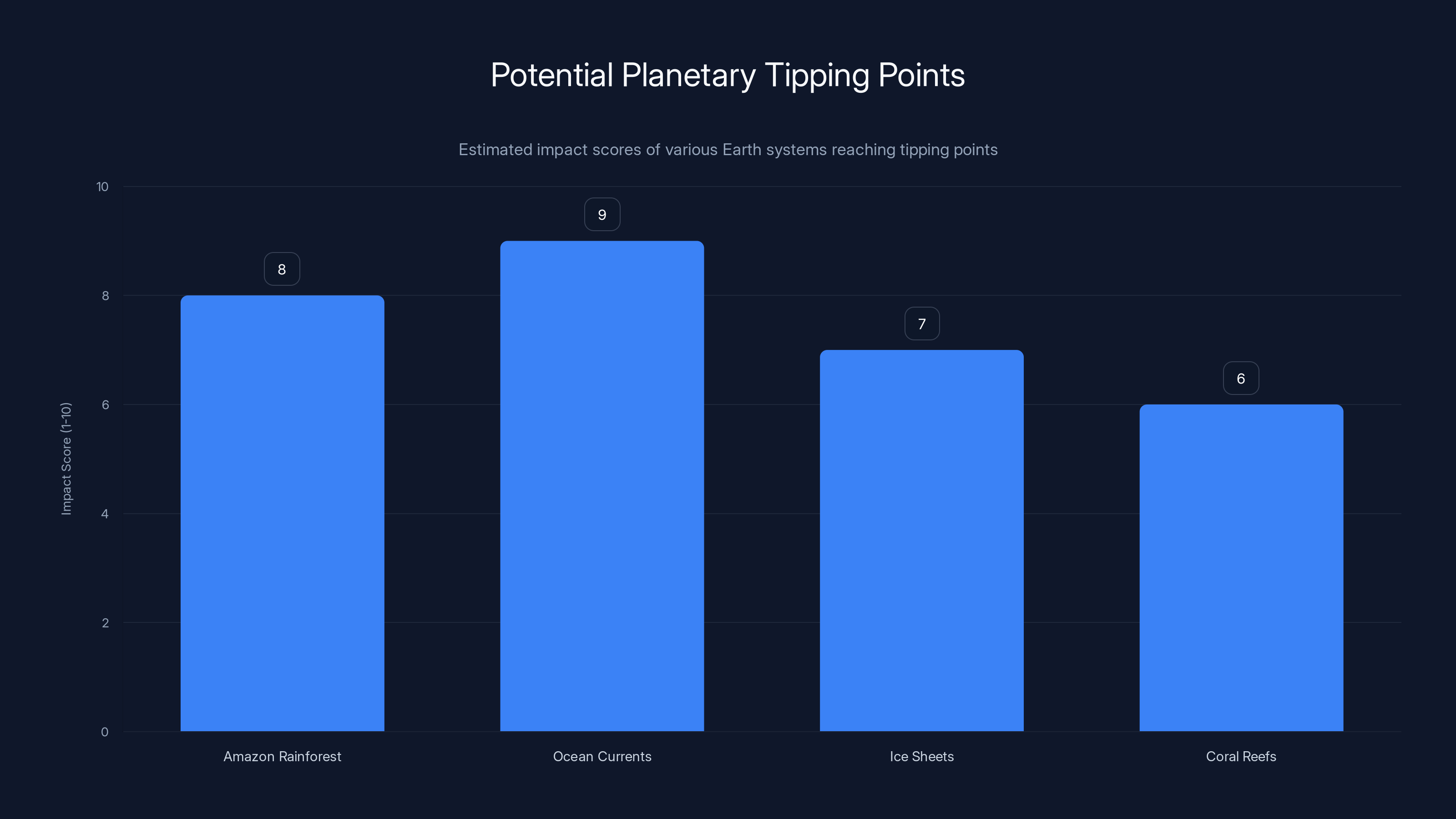

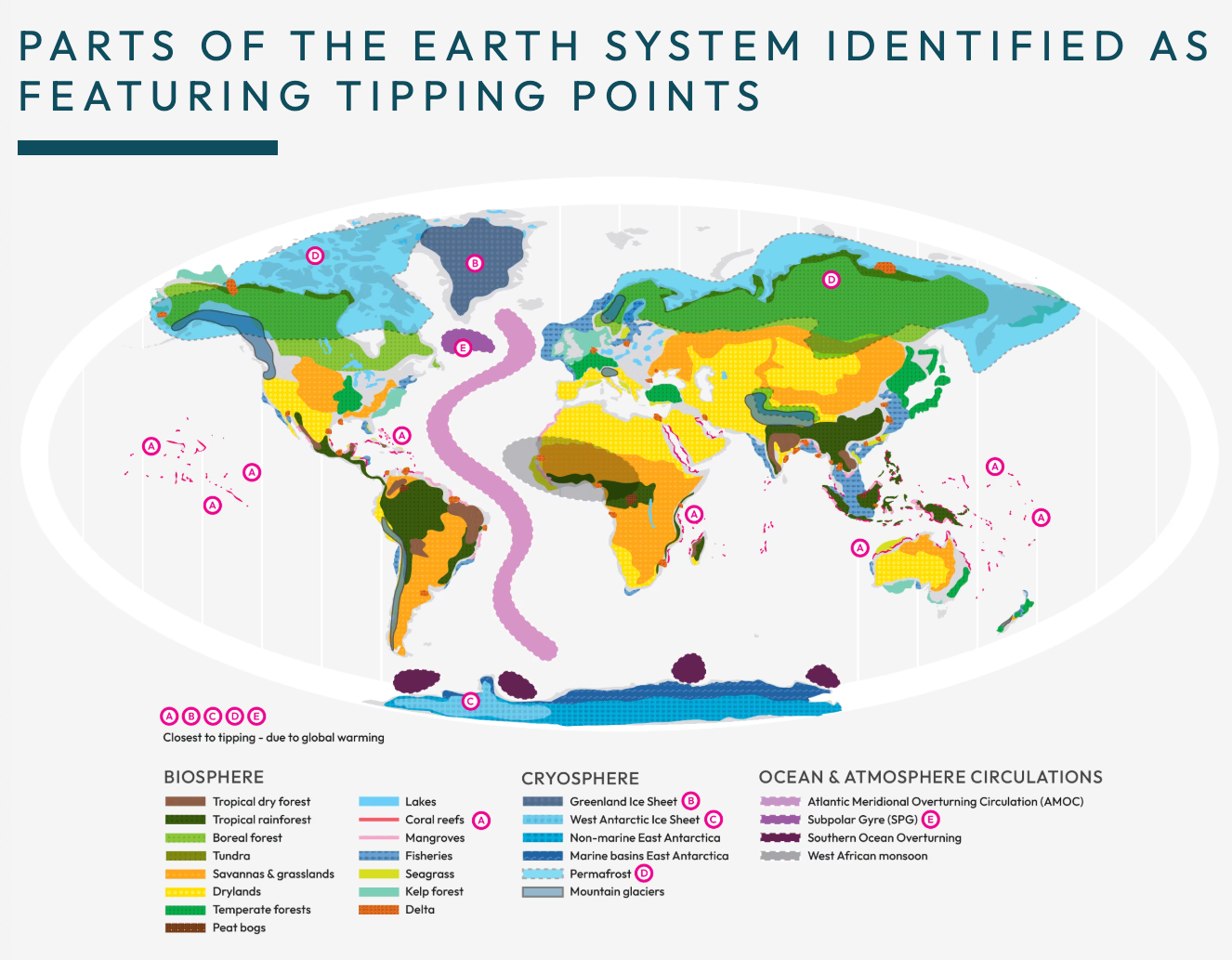

These aren't abstract theoretical concepts anymore. Climate scientists have identified specific systems on Earth that function as stabilizing forces—mechanisms that keep the planet in a state humans can actually live in. The Amazon rainforest absorbs and stores carbon. Ocean currents distribute heat and nutrients. Ice sheets reflect sunlight back into space. Coral reefs filter water and create nurseries for fish.

When these systems are healthy, they dampen stress. They absorb shocks. They maintain resilience. But each one has a threshold temperature, a level of acidification, a degree of stress beyond which it can't function anymore.

Cross that threshold, and the system doesn't weaken—it inverts. Instead of absorbing stress, it amplifies it. The Amazon shifts from carbon sink to carbon source, releasing stored carbon into the atmosphere instead of trapping it. The Greenland Ice Sheet melts faster, reducing the reflectivity that keeps the Arctic cool. Warming accelerates warming. Collapse accelerates collapse.

The Cascade Effect

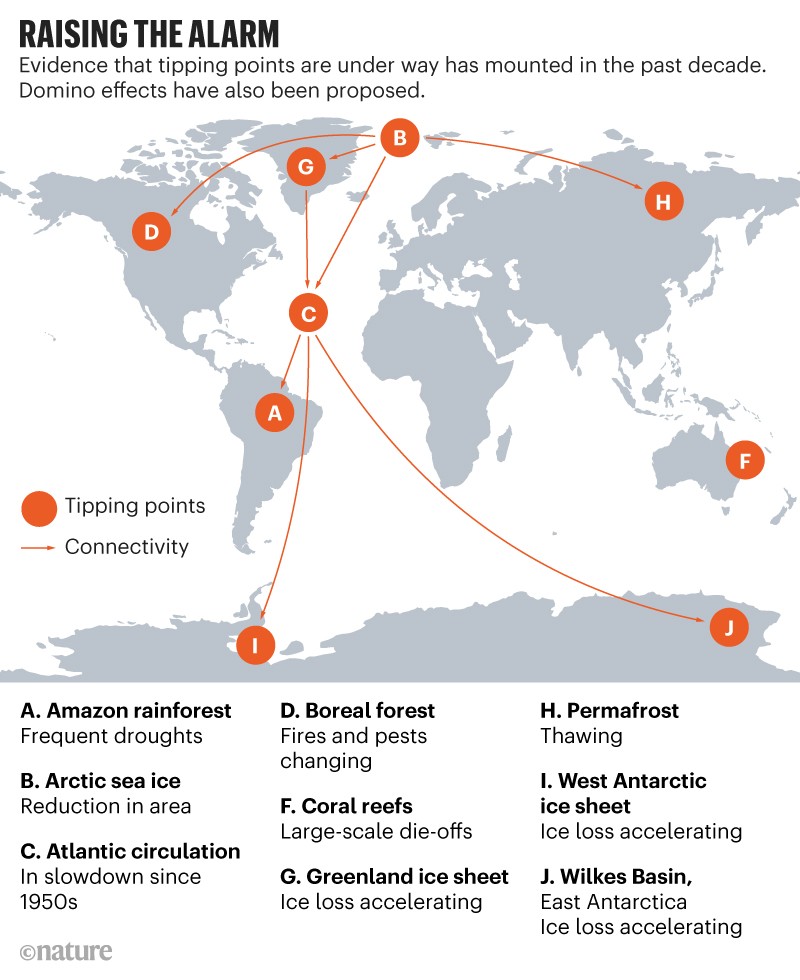

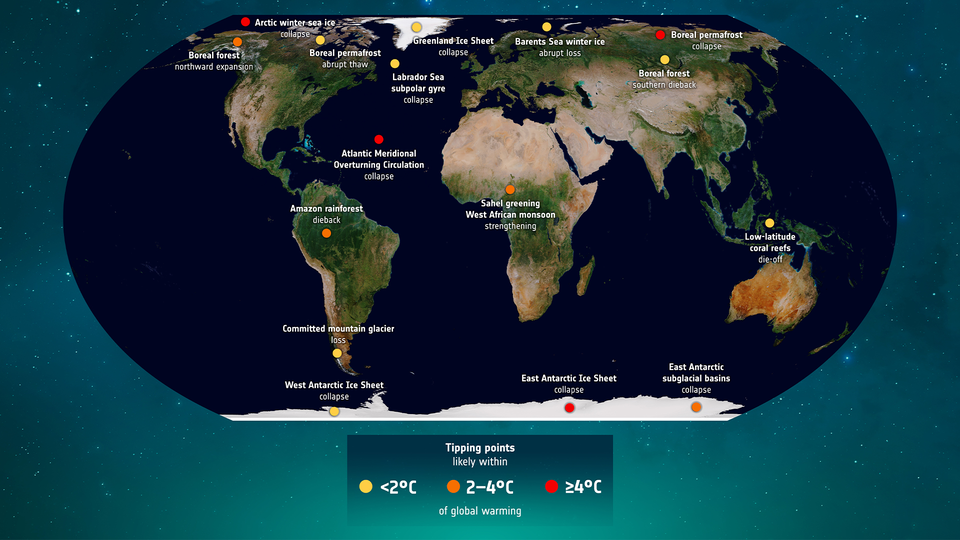

What makes this genuinely terrifying isn't just individual tipping points. It's cascade effects.

When one major system tips, it can push others across their thresholds. The Amazon tipping could weaken Atlantic Ocean currents. Ocean current disruption could cool the North Atlantic just enough to destabilize the Greenland Ice Sheet. Greenland melting could further disrupt ocean circulation. Each collapse triggers the next one like dominoes.

This isn't speculation. Researchers have mapped these connections. The risk isn't that one tipping point will break the planet. The risk is that multiple tipping points will fall into a cascading sequence where each one makes the others worse.

In systems theory, this is called a "catastrophic bifurcation"—a point where the system fundamentally reorganizes itself into a new state that's far less stable. Once that happens, even if you stopped adding carbon tomorrow, the planet wouldn't snap back to normal. It would stay in the new, damaged state indefinitely.

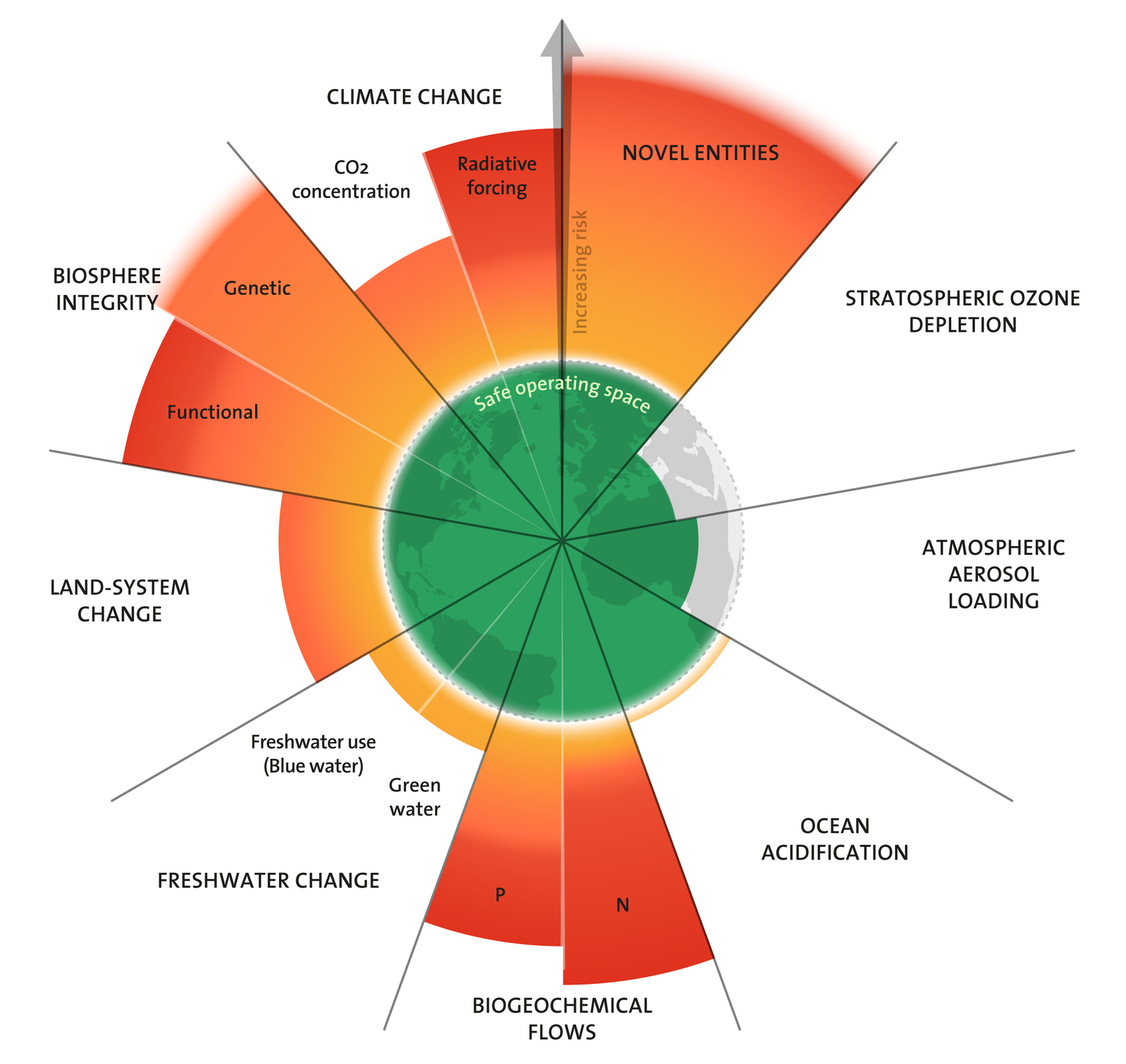

Current Status: Six of Nine Already Exceeded

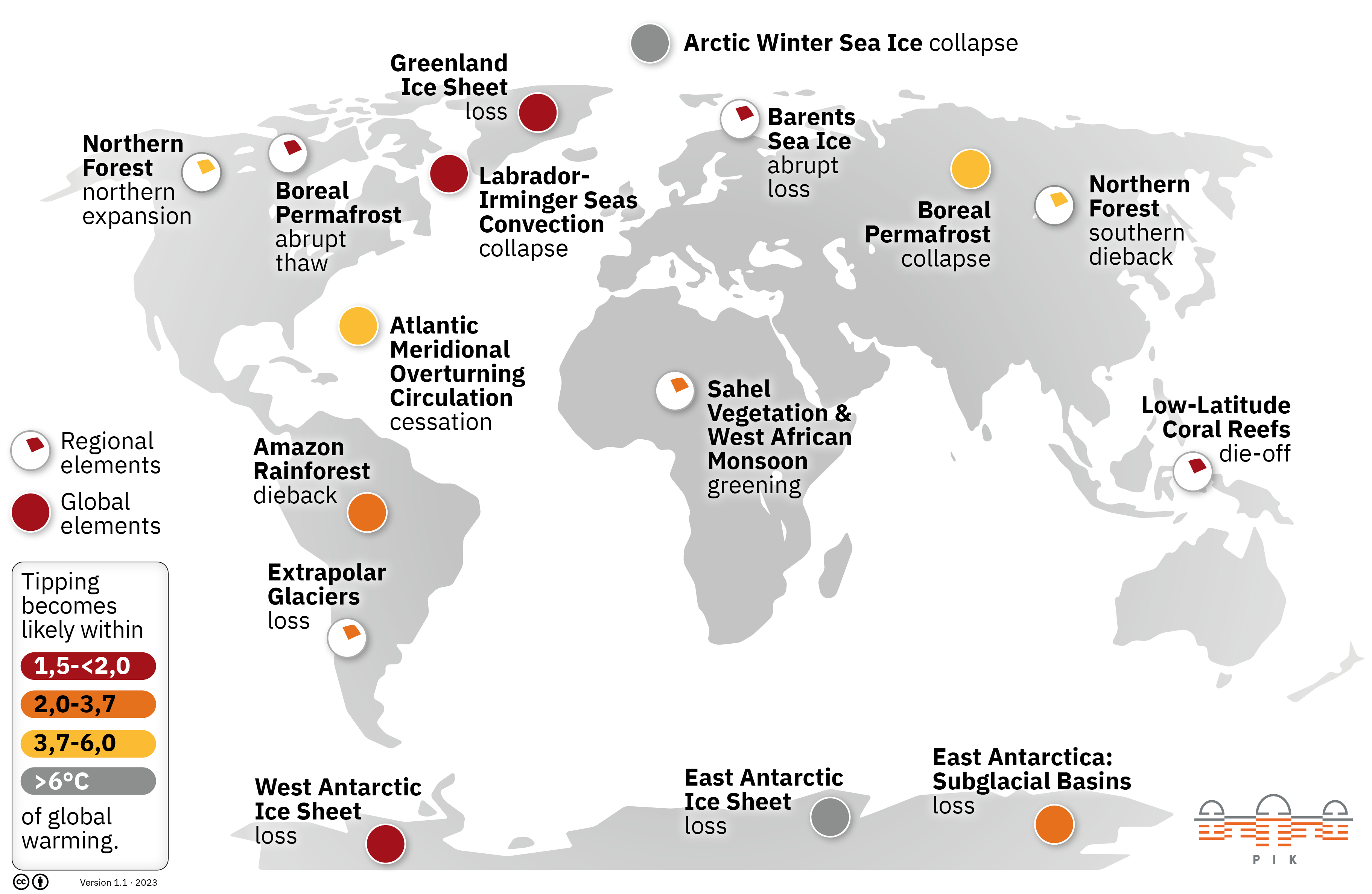

The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research has identified nine critical planetary boundaries—the limits of our planet's livable systems. These aren't predictions. These are measurements of what we're already doing.

As of 2025, six of those nine boundaries have already been crossed:

- Climate change: Well beyond safe limits

- Biodiversity loss: Extinction rates at 100-1,000 times background levels

- Land-system change: 50% of ice-free land is already used by humans

- Nutrient pollution: Nitrogen and phosphorus cycling destabilized

- Chemical pollution: Persistent organic pollutants, microplastics, and heavy metals in every ecosystem

- Ocean acidification: pH levels shifting faster than any time in 66 million years

We haven't officially crossed the remaining three, but we're closing in on them hard. Freshwater depletion, ozone depletion, and aerosol loading are all approaching critical levels.

This isn't interpretation or debate. These are objective measurements of planetary boundaries that humans have established matter scientifically through decades of research.

The Great Barrier Reef: A Living Warning System

Before we talk about the future, let's look at what's happening right now in one of the most biodiverse places on Earth.

The Great Barrier Reef is massive. Nearly 1,500 miles long. Home to 1,500 species of fish, 400 types of coral, 4,000 varieties of mollusks, and thousands of other organisms. The ecosystem generates over $56 billion in tourism and fishing revenue annually. For over 400 million people worldwide, coral reefs aren't just beautiful—they're survival infrastructure.

In 2024, the Great Barrier Reef experienced a mass bleaching event. Every coral that bleaches doesn't die immediately, but it's in trauma. The symbiotic algae that lives inside the coral—the algae that gives coral its color and most of its nutrition—gets expelled as a stress response to heat. The coral turns white. Ghostly white. Skeletal.

The reef can theoretically recover from bleaching if it has time. Corals can regrow the algae. The ecosystem can restabilize. But it needs years. Multiple years. Time to heal between stress events.

Then 2025 arrived. Another bleaching event hit. Just one year apart.

Look at the timeline:

- 2016: Major bleaching event

- 2017: Another major bleaching event

- 2020: Major bleaching event

- 2022: Major bleaching event

- 2024: Major bleaching event

- 2025: Major bleaching event

In the last decade, the Great Barrier Reef has experienced mass bleaching events six times. That's not a cyclical pattern you can bounce back from. That's a system being destroyed in real time.

The Bleaching Cascade

Here's what scientists are seeing: about 50 percent of the Great Barrier Reef's hard coral cover has already been lost to bleaching events and other climate stressors. That's not a 50 percent weakening. That's 50 percent dead.

When hard coral dies, what grows in its place is soft algae. Slimy algae. The kind of algae that doesn't provide habitat for fish. Doesn't create biodiversity. Doesn't provide the ecosystem services that make reefs valuable.

This is a phase shift. The reef is transforming from a hard coral ecosystem—high biodiversity, high productivity, high economic value—into an algal turf ecosystem. Lower biodiversity. Lower productivity. Lower everything.

Once a reef has undergone this phase shift, getting it back is nearly impossible. You're not just waiting for corals to regrow. You're fighting an entirely new ecosystem that's evolved to thrive in the new conditions. Reversing that would require actively killing the algae ecosystem and recreating the coral ecosystem from scratch.

Why Bleaching Events Are Accelerating

Coral bleaching happens when ocean temperatures spike above the thermal tolerance of the symbiotic algae. Traditionally, bleaching events were localized. A heat wave hit the Caribbean or a specific region of the Pacific, the local reefs bleached, and then if conditions cooled down, the reefs could recover.

In 2023-24, something different happened.

For only the fourth time in recorded history—and the second time in a single decade—the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced a global bleaching event. Not regional. Global. The entire world's oceans were too hot simultaneously.

This wasn't a localized heat wave. This was the baseline temperature of Earth's oceans rising so much that even the coolest parts of the ocean were above the thermal tolerance of tropical coral.

Let that sink in. The entire planet's oceans reached a state where coral couldn't survive anywhere.

And El Niño cycles are coming back. As ocean patterns shift, the Pacific Ocean is expected to warm again in 2026. When that happens, the Great Barrier Reef—already at 50 percent capacity after years of bleaching—will almost certainly experience another bleaching event.

At what point does "another chance to recover" become "no chance to recover"? Scientists think we're approaching that point. Maybe we've already crossed it.

Global Emissions: Still Going Up

Let's talk about the most basic climate metric: how much carbon we're dumping into the atmosphere.

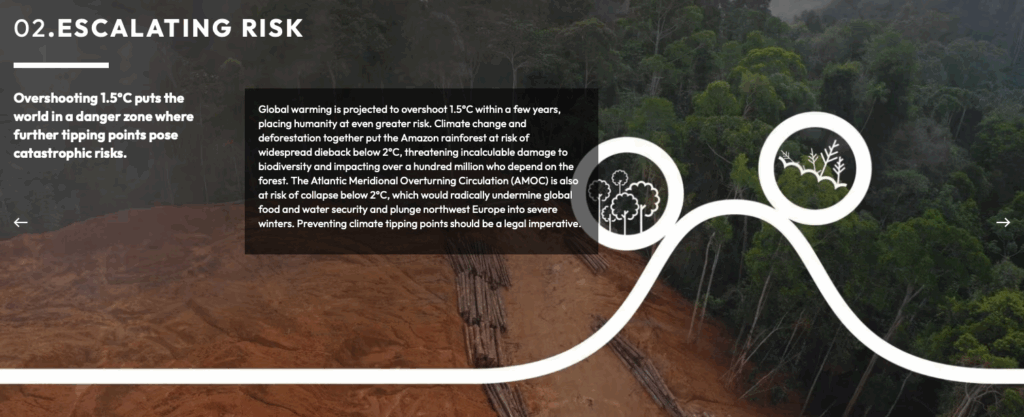

The goal was simple. In 2015, nearly every country on Earth signed the Paris Agreement. The commitment: keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius (ideally), or at least below 2 degrees Celsius. This requires global emissions to peak and then decline. Specifically, we needed global emissions to start declining by 2020.

We didn't hit that target.

Instead, emissions grew. In 2024, global greenhouse gas emissions reached an all-time high. Not a high for that decade. A high for all of recorded history.

The 2024 increase was only 0.8 percent from 2023. In normal years, people would call a 0.8 percent increase "relatively small." But we're not in normal years. We're in a crisis where every year of increased emissions makes the crisis worse.

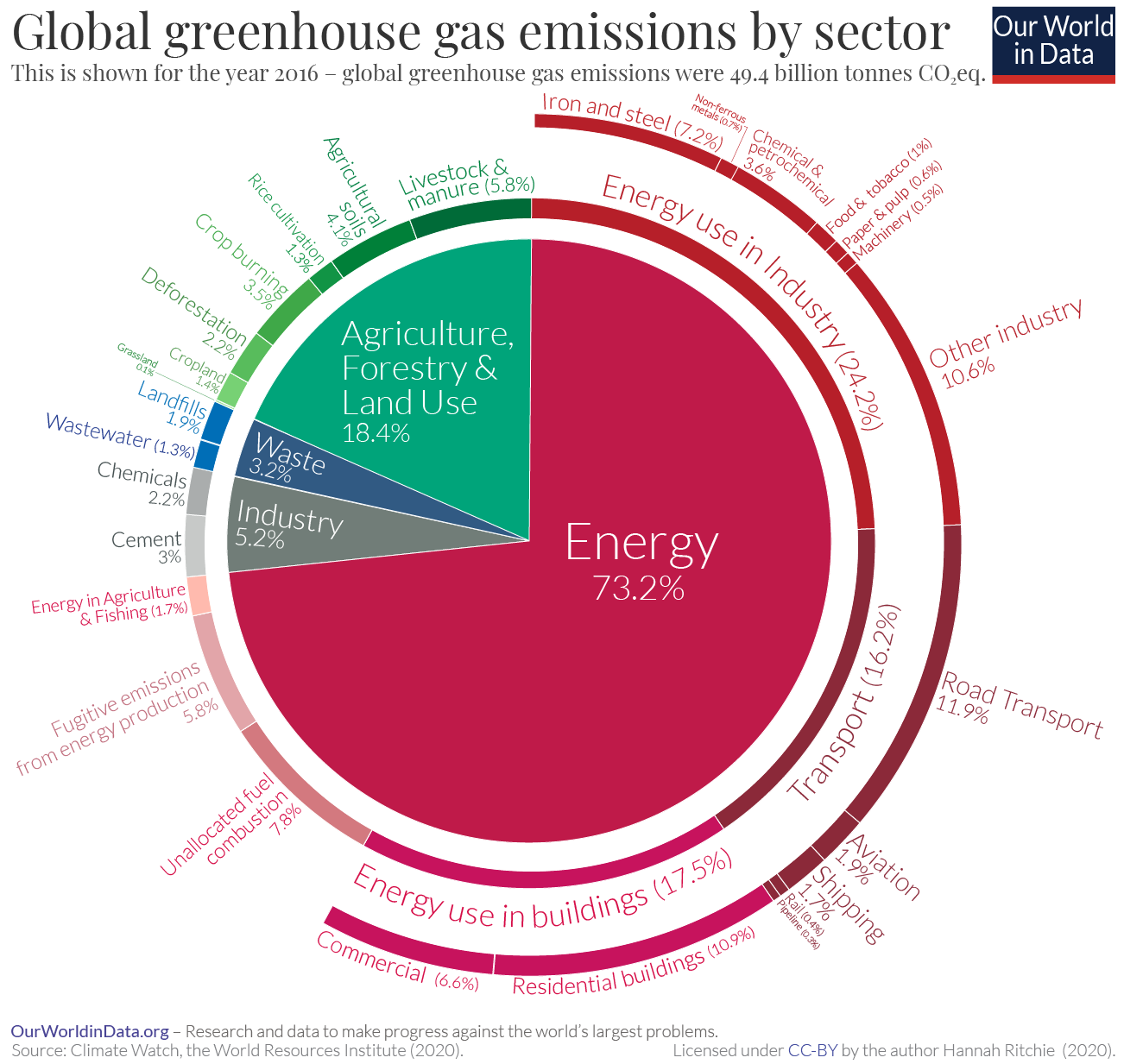

Where Are The Emissions Coming From?

This is the frustrating part: we know exactly where emissions come from. It's not a mystery. Fossil fuels dominate the emissions picture.

Energy production (electricity, heating, cooling) accounts for roughly 25 percent of global emissions. Transportation adds another 14 percent. Industry contributes 21 percent. Agriculture, forestry, and land use account for 24 percent. Building operations add 6 percent. Waste and wastewater add 3 percent. Other industrial processes round it out.

We're not talking about small, hard-to-address sources. We're talking about the core infrastructure of modern civilization. And we're not transitioning away from it fast enough.

Renewable energy capacity is growing. Solar and wind installations are accelerating. Electric vehicles are becoming cheaper. On the surface, you'd think we're making progress.

But we're not adding renewable energy to replace fossil fuels. We're adding renewable energy in addition to fossil fuels. Global coal, oil, and natural gas consumption keeps increasing. The renewable energy growth is real, but it's being overwhelmed by growing energy demand.

The Emissions Reduction Timeline

To have even a reasonable chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, global emissions from fossil fuels would need to drop by over 5 percent per year, reaching zero by 2050.

Let that sink in. Not 5 percent total by 2050. Five percent every single year for the next 25 years.

Current trajectory? We're going the opposite direction.

At the current rate of change, we're not on track to reach zero emissions by 2050. We're on track to reach zero by somewhere around 2150, if we're lucky. That's an extra century of emissions that will continue heating the planet, continue pushing us toward tipping points.

Even if we somehow managed to hit zero emissions today—which we won't—the carbon already in the atmosphere would continue warming the planet for decades. The climate system has lag time. Thermal momentum.

But we won't hit zero emissions today. We won't hit zero in 2050. We're not even trying at the scale the science demands.

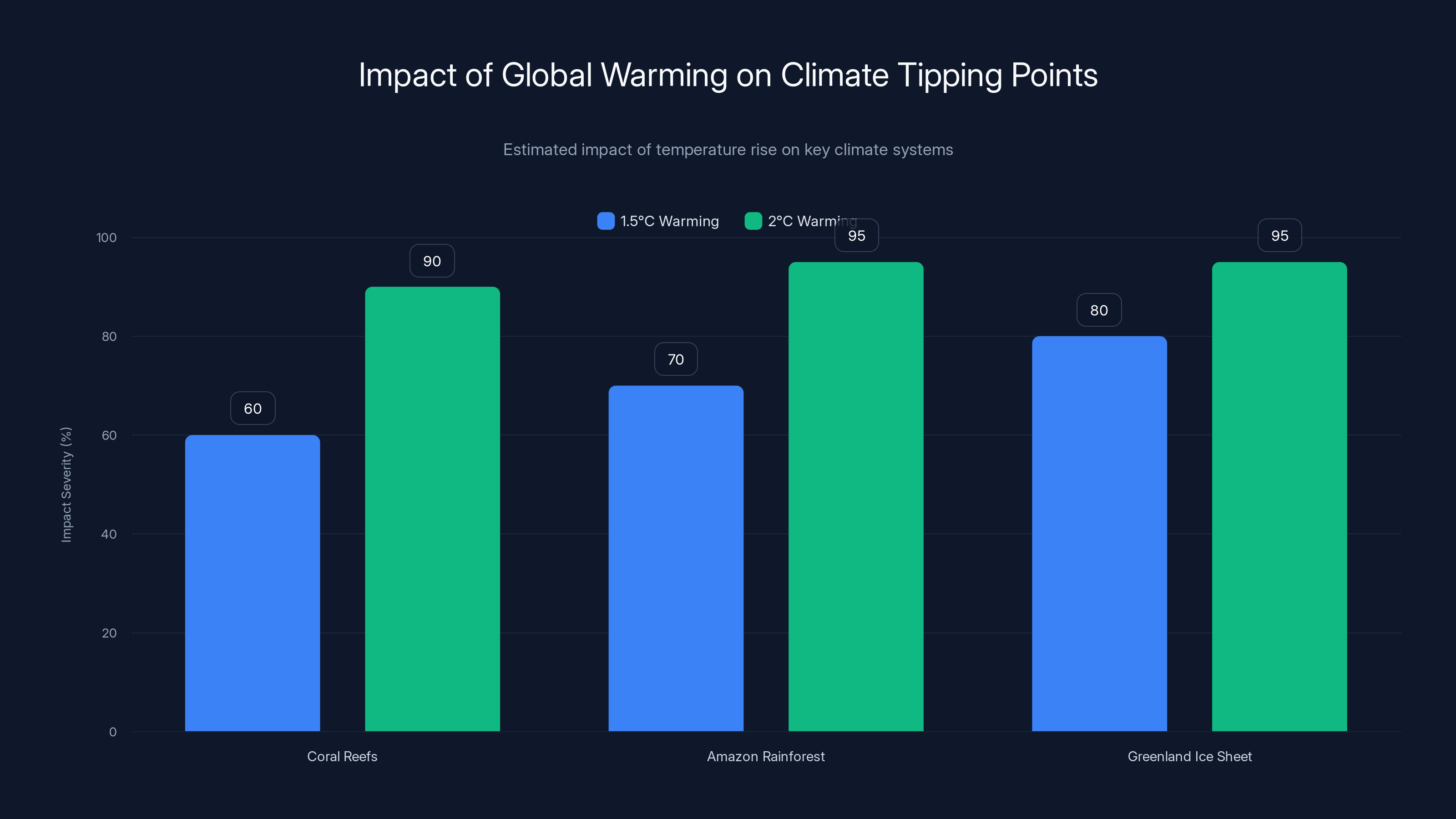

Estimated data shows significant increase in impact severity on climate systems between 1.5°C and 2°C warming, highlighting the urgency of limiting temperature rise.

The Ocean's Breaking Point

When people think about climate change impacts, they often think about weather: hotter summers, worse hurricanes, bigger floods. But the oceans are absorbing most of the crisis, and that's where the real danger lies.

Oceans have absorbed about 90 percent of the excess heat from greenhouse gas emissions. That heat isn't gone. It's stored in ocean water. As oceans warm, that stored energy creates more powerful storms, disrupts weather patterns, and destabilizes marine ecosystems.

Ocean acidification is happening simultaneously. As carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it forms carbonic acid. The pH of ocean water is dropping. Faster than any time in at least 66 million years.

pH is a logarithmic scale. A change of 0.1 pH units represents a 30 percent increase in acidity. The oceans have already shifted 0.13 pH units since pre-industrial times. That's a 40 percent increase in acidity.

This matters because organisms that build shells—pteropods, oysters, corals—struggle in more acidic water. The calcium carbonate in their shells starts dissolving. The energy cost of building new shell increases. They become more vulnerable.

Coral specifically needs both stable temperatures and stable pH. Right now, neither is stable. Both are shifting rapidly toward conditions that coral cannot tolerate.

Ocean Heat Waves

Ocean heat waves aren't just isolated hot spots anymore. They're becoming chronic conditions.

In 2023-24, a marine heat wave persisted in the Atlantic for extended periods. In 2024, the North Atlantic experienced record warmth. Atlantic hurricanes formed in unusually warm water. The Gulf of Mexico hit temperatures that approached hot tub levels. These aren't random weather variations—they're the new normal.

For coral ecosystems, ocean heat waves are existential threats. A coral's thermal tolerance is usually about 1-2 degrees Celsius above the warmest water it typically experiences. Once the ocean is regularly warmer than that, the coral is always stressed.

Add another heat wave on top of chronically warm water, and the coral gives up. It expels its symbiotic algae. It bleaches. And if the warm conditions persist, if there's no break before the next heat wave hits, the coral dies.

This is what happened to the Great Barrier Reef. The water isn't just warmer than it used to be. It's persistently warmer. There's no cool season anymore to let the reef recover.

Why Tipping Points Matter More Than Average Temperature

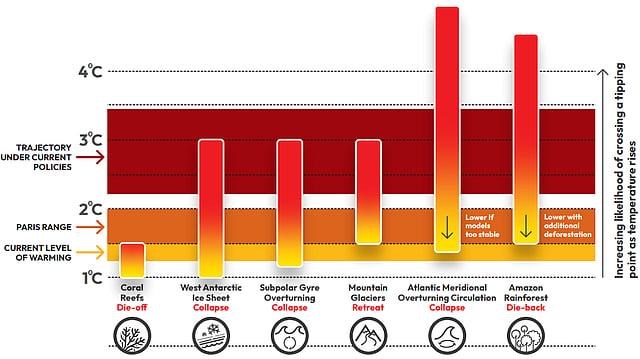

When climate scientists talk about limiting warming to "1.5 degrees Celsius," it sounds abstract. We're already at about 1.2 degrees of warming compared to pre-industrial times. We're close to 1.5. What's another 0.3 degrees?

Here's the problem: that 0.3 degrees is the difference between a system that's stressed and a system that's completely non-functional.

For tropical coral reefs, the tipping point is thought to be around 1.5 degrees of warming. At that level, mass bleaching becomes permanent. Reefs don't recover between events. They flip from hard coral ecosystems to algal turfs. The phase shift becomes irreversible.

We're at 1.2 degrees now. We're within 0.3 degrees of permanently losing the world's tropical coral reefs.

For the Amazon rainforest, the tipping point is estimated somewhere between 1.5 and 2.5 degrees. We don't know exactly where, and that uncertainty is dangerous. The Amazon could be fine at 1.5 degrees, or it could be past its tipping point and we wouldn't even know until it started collapsing.

For the Greenland Ice Sheet, the tipping point is estimated at around 1.5 to 3 degrees. Above that, the ice sheet melts faster than it can be replenished, and it's gone—eventually raising sea levels by 7 meters.

For the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (the conveyor belt of ocean currents that distributes heat around the planet), the tipping point is estimated somewhere around 1.5 to 2 degrees.

Notice a pattern? Several of our planet's most critical systems have tipping points clustered around 1.5 degrees. The same temperature we're about to cross.

This isn't coincidence. It's a feature of climate system dynamics. As warming increases, systems don't gradually weaken. They suddenly destabilize when they hit their threshold. Multiple systems can have similar thresholds because they're responding to the same underlying driver: planetary temperature.

The risk is that we're about to cross into a temperature range where multiple systems tip at once or in quick succession. That's when the cascade effect becomes a problem. One ecosystem collapse triggers another. Another amplifies the warming, triggering more collapses.

Food Systems: From Carbon Source to Carbon Sink

Even if humanity managed to stop emitting greenhouse gases tomorrow—which won't happen—we'd still need to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

The carbon we've already emitted will stay in the atmosphere for centuries. The warming already locked in will continue pushing systems toward tipping points for decades. Simply reaching zero emissions isn't enough to save the ecosystems we're trying to protect.

We also need to become carbon negative. We need to remove more carbon from the atmosphere than we emit.

One of the largest untapped carbon sinks on Earth is the global food system. Currently, agriculture and land use are carbon sources—they emit more greenhouse gases than they capture. The system is actively warming the planet.

Shifting that would require fundamental changes to how we grow food, raise livestock, manage forests, and use land. Instead of clearing forests for agriculture, we'd need to restore them. Instead of intensive monoculture farming that depletes soil carbon, we'd need regenerative practices that build soil carbon.

The Carbon Removal Target

According to climate research, by 2050, humanity would need to be permanently removing more than 5 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year.

That's not a gradual transition. That's a complete restructuring of global food systems in the next 25 years.

To put that in perspective, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that 1 hectare of restored forest sequesters about 5 tons of carbon per year. To remove 5 billion tons of carbon annually through reforestation alone, you'd need to restore about 1 billion hectares of forest.

That's roughly the size of the United States. Every year. For 25 years.

And that's just one pathway for carbon removal. You'd also need technological carbon capture, ocean alkalinity enhancement, biochar production, regenerative agriculture scaling, and other approaches.

None of this is impossible. All of it is technologically feasible. But politically? Economically? Organizationally? The scale of transformation required is almost incomprehensible.

Biodiversity Collapse and Ecosystem Cascades

When we talk about coral bleaching or ice sheet melting, these are easy to visualize. But beneath these obvious symptoms, a broader collapse is unfolding: the loss of biological diversity at a scale not seen since the dinosaurs went extinct.

Species extinction rates have accelerated dramatically. We're losing species at 100 to 1,000 times the natural background rate. In the last 500 years, humans have driven about 15,000 species to extinction. That's up from about 800 species before industrialization.

This matters because ecosystems don't work like a collection of independent pieces. They're networks. Each species plays a role. Remove one species, and the network destabilizes. The impact cascades.

When pollinator populations collapse, crop yields decline. When predator populations disappear, herbivore populations explode and strip vegetation. When herbivore populations crash, the predators that depend on them starve. The ecosystem reorganizes around the species that remain.

Coral reefs are experiencing this right now. As corals die and reefs transition to algal turfs, the fish species that depend on coral habitat disappear. As fish populations decline, the predators that eat those fish—sharks, groupers, other large predators—starve and migrate. The ecosystem shifts toward smaller species that can survive in the new algal reef environment.

But algal reefs support fewer total species. They're lower in productivity. They generate less food for the ocean food web. The result is a less resilient, less productive ecosystem. One that's more prone to further collapse.

This pattern repeats across ecosystems. Forests lose canopy species and become dominated by pioneer species. Grasslands lose native perennials and become dominated by invasive species. Freshwater systems lose native fish and become dominated by invasive species adapted to warmer, more polluted water.

The planet isn't just getting hotter. It's becoming systematically less biodiverse. Less resilient. Less capable of supporting the species that depend on it—including us.

The Great Barrier Reef has experienced six major bleaching events from 2016 to 2025, highlighting a critical stress pattern that threatens its survival.

Regional Impacts: Why Location Matters

Climate change is often described as a global problem, and it is. But its impacts are distributed unevenly. Some regions are hitting tipping points much faster than others.

The Arctic is warming at nearly twice the rate of the global average. This is the "Arctic amplification" effect—as ice melts, it exposes darker ocean water that absorbs more heat, which melts more ice, which exposes more water. It's a positive feedback loop.

Tropical regions are experiencing different patterns. In tropical oceans, warming is already at critical levels for marine ecosystems. The thermal tolerance of tropical coral is narrow. In many tropical regions, the warmest months are already near the bleaching threshold.

Dryland regions—the Mediterranean, North Africa, the American Southwest—are experiencing more intense droughts. As warming progresses, the hydrological cycle intensifies. Wet regions get wetter. Dry regions get drier. Monsoon patterns shift. Flooding increases in some regions while drought intensifies in others.

Small island nations are in an existential crisis. Rising sea levels threaten their very existence. But that's only one impact. Coral reef collapse means loss of fisheries, tourism, and food security. Changing ocean currents alter fish populations that island economies depend on. Extreme weather becomes more frequent and intense.

These impacts aren't distributed equally because the regions with the least capacity to adapt are being hit hardest. The Global South contributes disproportionately little to emissions but is experiencing disproportionately severe impacts. This creates a justice issue alongside the environmental issue.

The Role of Ocean Currents and Heat Distribution

One of the most critical systems for planetary climate regulation is ocean circulation. These currents act as a heat engine for the planet, absorbing heat in warm regions and transporting it toward the poles.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is part of this system. It includes the Gulf Stream, which brings warm water from the tropics toward Europe. Without the Gulf Stream, the UK and Scandinavia would be as cold as Alaska, even though they're at similar latitudes.

Recent research suggests that AMOC has weakened by about 15 percent since the mid-20th century. The weakening is linked to freshwater input from melting ice sheets and glaciers, which disrupts the density gradients that drive ocean circulation.

If AMOC continues to weaken and eventually collapses, the impacts would be severe. Europe's climate would cool, but global climate would warm because heat that would normally be transported northward would remain in tropical and subtropical regions. Weather patterns globally would shift. Monsoons would be disrupted. The Atlantic hurricane season would be affected. Agricultural productivity in key food-producing regions would decline.

This is a genuine tipping point. There's a threshold beyond which AMOC doesn't just weaken—it shifts into a different mode of operation. Once it shifts, even if you removed the stressor (melting ice), it might not shift back for centuries.

Feedback Loops and Positive Reinforcement

The reason scientists are so concerned about tipping points is feedback loops. In a stable system, negative feedback keeps things balanced. You get too warm, and the system cools you down. You get too cold, and the system warms you up. Homeostasis.

But when you start triggering tipping points, you shift from negative feedback to positive feedback. The system reinforces the change instead of opposing it.

Here are some key positive feedback loops already active:

Ice-albedo feedback: White ice reflects sunlight. Dark ocean water absorbs it. As ice melts, less sunlight is reflected, more is absorbed, warming accelerates, more ice melts.

Water vapor feedback: Warmer air holds more water vapor. Water vapor is a greenhouse gas. More warming causes more water vapor, which causes more warming.

Carbon cycle feedback: Warming thaws permafrost, releasing methane and carbon dioxide. Warming weakens the biological carbon sink of the ocean. Warming slows the carbon uptake of soils. So warming causes more carbon release, which causes more warming.

Vegetation feedback: Warming changes vegetation patterns. Forests shift from carbon sinks to carbon sources. Grasslands shift toward less vegetation coverage. Reduced vegetation coverage reduces the planet's capacity to absorb carbon.

Each of these creates a loop where warming causes processes that cause more warming. Once these loops are established, they become self-reinforcing. The system doesn't need external forcing to keep warming—the warming causes processes that perpetuate warming.

This is why small temperature increases matter so much. The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius isn't just a 33 percent increase in impact. It's a difference in whether these feedback loops tip into runaway conditions or whether we can still manage them.

What Coral Bleaching Teaches Us About Ecosystem Collapse

Coral bleaching isn't just an ecological tragedy. It's a teaching moment about how ecosystems actually fail.

Coral looks strong. It's hard. It builds massive structures. The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest living structure. It seems resilient. But it's fragile in a way that most people don't understand.

The coral animal itself is tough, but it survives in a narrow window of conditions. The temperature can't fluctuate too much. The pH needs to be right. The oxygen levels need to be adequate. The nutrient balance needs to be right.

For thousands of years, these conditions stayed stable enough for coral to thrive. When they varied, they varied slowly enough for coral to adapt. But now they're varying too fast and too far.

The response of coral to stress isn't gradual degradation. It's sudden rejection of symbiotic partners. The coral doesn't die—it expels the algae. But without the algae, the coral is essentially starving. It can survive for a while, but it won't recover unless the conditions that allowed the algae to return are re-established.

This is the lesson: biological systems can tolerate gradual change. They can't tolerate rapid change.

The rate of change matters as much as the magnitude of change. A 5-degree warming over 5,000 years might allow species to migrate and adapt. A 5-degree warming over 500 years doesn't give them time to adapt. A 5-degree warming over 50 years is catastrophic.

We're not talking about 50-year timescales in most cases. We're talking about 25-year timescales. One human generation. That's not time for forests to migrate. It's not time for species to evolve tolerance. It's not time for ecosystems to reorganize.

Coral bleaching is happening at a pace that evolution cannot keep up with. That adaptation cannot keep up with. That ecosystems cannot reorganize in response to.

And coral isn't unique. This is true for forests, grasslands, freshwater ecosystems, and soil systems worldwide.

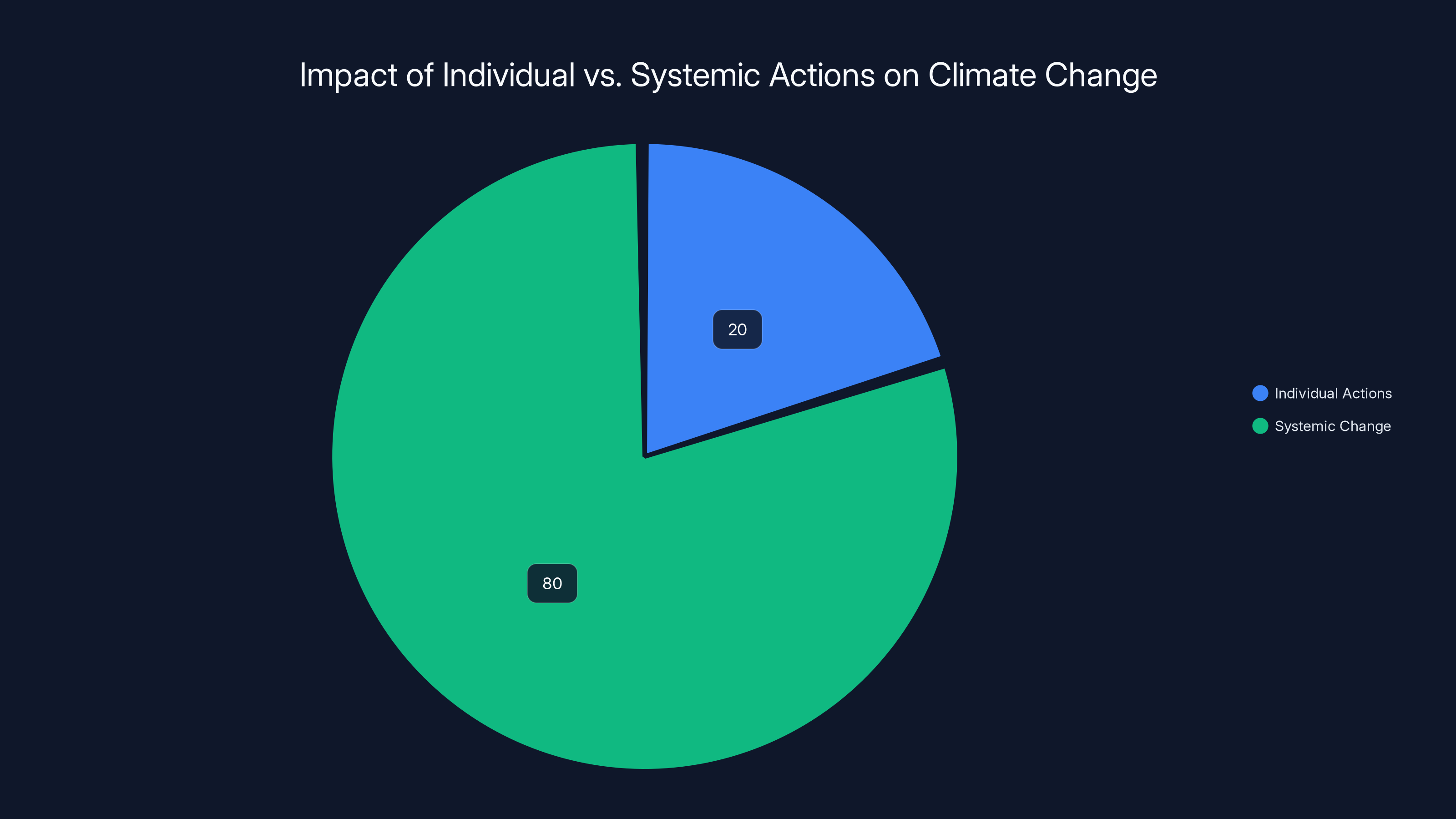

Systemic change is estimated to contribute 80% to effective climate action, highlighting its critical role over individual actions (20%). Estimated data.

The Amazon: Another Tipping Point Approaching

The Amazon rainforest covers about 5.5 million square kilometers across nine countries, with about 60 percent in Brazil. It generates about 20 percent of the world's oxygen. It stores somewhere between 150 to 200 billion metric tons of carbon. It's home to about 10 percent of all species on Earth.

It's also approaching a tipping point.

For millennia, the Amazon maintained itself through internal moisture cycling. Trees transpire water into the atmosphere. That water condenses and falls as rain. That rain feeds more trees. The forest creates its own weather.

But this cycle has thresholds. If deforestation removes more than about 20-25 percent of forest cover, the internal moisture cycling breaks down. At that point, the forest can no longer maintain the humidity needed to sustain itself. It begins a transition from rainforest to savanna.

We're currently at about 17 percent deforestation in the Amazon. We're within a few percentage points of the tipping point.

Once that tipping point is crossed, the forest doesn't just stop growing. It actively dies back. Existing trees become stressed due to reduced moisture. Fires become more frequent and more intense. The ecosystem shifts toward grassland.

When that happens, the 150-200 billion metric tons of carbon stored in the Amazon forest becomes a carbon source instead of a sink. Instead of absorbing carbon, it releases carbon, warming the planet, which stresses the remaining forest more, which causes more die-back.

This is the cascade effect. Amazon tipping triggers global warming acceleration, which makes it harder to prevent other tipping points like coral collapse and ice sheet collapse.

Greenland's Ice Sheet: A Sleeping Giant

The Greenland Ice Sheet contains enough ice to raise global sea levels by about 7 meters. That's not theoretical. That's measured. It's just sitting there, frozen.

Currently, the ice sheet is losing mass—melting faster than snow accumulates. The mass loss is accelerating. And the ice sheet has a tipping point.

Right now, the ice sheet melts at the edges but remains stable at higher elevations where it's cold. But as temperatures warm, the elevation where melting occurs rises. At some point, a critical threshold is crossed where the entire ice sheet is in the ablation zone (the zone where melting exceeds snow accumulation).

Once that happens, the ice sheet doesn't just weaken—it enters a runaway melting phase. The warmer surface causes more melting, which lowers the surface elevation, which puts it in warmer air, which causes more melting.

Scientists estimate this tipping point is somewhere around 1.5 to 3 degrees of warming. We're at 1.2. We could be within a decade of triggering irreversible melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

If that happens, the 7-meter sea level rise doesn't happen next year. It happens over centuries. But it becomes inevitable. Coastal cities worldwide—New York, London, Shanghai, Mumbai, Jakarta, Sydney—start planning for abandonment. Not in a few decades. Over the next 200 years.

But here's the thing: we make long-term infrastructure decisions today. We build buildings expecting them to last 50-100 years. We invest in ports and airports with planning horizons of decades. If we cross the Greenland tipping point, we're making decisions today that will prove catastrophically wrong in our grandchildren's lifetime.

What "Limiting Warming to 1.5 Degrees" Actually Means

When climate policy talks about "limiting warming to 1.5 degrees," it's not describing a target that keeps the planet exactly as it is now. It's describing a limit on how bad things get.

At 1.2 degrees (current warming), we're already seeing:

- Stronger hurricanes and typhoons

- Increased frequency of heat waves

- Changes in precipitation patterns

- Stress on agricultural systems

- Rising sea levels

- Coral bleaching

At 1.5 degrees (0.3 degrees from now), we'll see:

- More intense storms

- More frequent heat waves

- Greater agricultural disruption

- Tropical coral reef ecosystems largely lost

- Potential tipping of the Amazon

- Possible AMOC disruption

- Increased species extinction

At 2 degrees (0.8 degrees from now), impacts escalate significantly:

- Major agricultural failures in key regions

- Potential Greenland Ice Sheet tipping

- Cascading ecosystem collapses

- Hundreds of millions of people affected by sea level rise, drought, or food insecurity

The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees doesn't sound huge when you say it out loud. But in terms of ecosystem impacts, it's the difference between "severe damage" and "cascading collapse."

The Emissions Gap: What We're Doing vs. What We Need to Do

There's a term in climate science called the "emissions gap"—the difference between the emissions trajectory we're currently on and the emissions trajectory we need to be on to limit warming.

Current policy and commitments put us on track for roughly 2.5 to 3 degrees of warming by 2100. The Paris Agreement target is 1.5 to 2 degrees.

That gap—the difference between current trajectory and climate targets—represents the cumulative emissions of the next 25 years.

To close that gap, we'd need to:

-

Immediately deploy renewable energy at unprecedented scale: Solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and other renewables would need to expand 3-4 times faster than current rates.

-

Electrify transportation: Every vehicle sold would need to be electric or hydrogen-powered. Current timeline? Electric vehicles will be a significant portion of new car sales by 2040, but they're not the dominant source yet.

-

Decarbonize industry: Steel, cement, chemicals, and other industrial processes are responsible for about 21 percent of emissions. Decarbonizing them requires technological transitions that haven't been scaled up yet.

-

Halt deforestation: Protecting existing forests is actually one of the most cost-effective climate solutions. But it hasn't happened. Deforestation continues.

-

Transition agriculture: Shifting toward regenerative practices and reducing livestock emissions requires changing how billions of people produce and consume food.

-

Deploy carbon removal at scale: We need billions of tons per year of carbon removal, but current deployment is thousands of tons per year. That's a million-fold gap.

Every one of these requires political will, economic investment, and behavioral change at a scale we've never attempted before.

And even if we did all of it perfectly starting tomorrow, we'd still be locked into 1.5+ degrees of warming based on carbon already in the atmosphere.

The line chart shows a steady increase in greenhouse gas emissions from 2016 to 2025, alongside recurring coral bleaching events. Estimated data for emissions increase.

The Role of Individual Action vs. Systemic Change

There's a common narrative that climate change is a problem of individual consumption. If enough people drive electric cars, eat less meat, and use renewable energy, the problem is solved.

This is well-intentioned but dangerously naive.

Individual actions matter, but they don't scale to the problem. Even if every person in the developed world adopted zero-carbon lifestyles tomorrow, global emissions would barely decline. Why? Because emissions are driven by industrial systems, energy infrastructure, and economic structures. Individual behavior operates within those systems.

A person drives an electric car powered by electricity generated from coal. They buy goods transported by container ships burning bunker fuel. They heat their home with natural gas. Their individual choices matter, but they're constrained by the available choices.

Meaningful climate action requires systemic change: transitioning the energy grid from fossil fuels to renewables, redesigning transportation networks, restructuring agricultural systems, rebuilding industrial processes.

That said, individual action isn't irrelevant. It serves multiple purposes:

-

Reduces personal carbon footprint: If you can't avoid the problem systematically, reducing individual impact matters.

-

Builds political pressure for systemic change: When individuals demand alternatives, it creates demand for systemic solutions. This incentivizes businesses and governments to act.

-

Normalizes low-carbon practices: When adoption of electric vehicles or renewable energy becomes normal, it becomes politically easier to mandate it.

-

Creates economic demand: As individuals vote with their wallets for low-carbon options, markets respond by scaling those options, reducing their cost.

But individual action alone cannot solve this problem. We need both individual and systemic change, with the systemic change being the binding constraint.

The Australian Context: The 2026 UN Climate Negotiations

Australia is currently preparing to host the 2026 UN climate negotiations (COP31). This is both an opportunity and a vulnerability.

Australia is one of the largest fossil fuel exporters in the world. Coal and natural gas are major export industries. The country is simultaneously home to the Great Barrier Reef, one of the most climate-vulnerable ecosystems on the planet.

This creates a peculiar situation: Australia's economy is built on exporting the fuels that are destroying one of its most iconic natural systems.

The 2026 negotiations present an opportunity for Australia to demonstrate climate leadership. Hosting COP31 while the Great Barrier Reef is experiencing unprecedented bleaching events creates pressure to do more than just talk.

But it also creates political tension. Australian coal and gas industries have significant political influence. Transitioning away from those industries would require economic restructuring that affects millions of jobs and billions of dollars in economic value.

The stakes are high. If the Great Barrier Reef crosses the point of no return—if bleaching becomes so frequent that the ecosystem can no longer recover—it represents the first major ecosystem tipping point in the climate crisis. That would be a demonstration of the danger we're facing.

Conversely, if Australia were to rapidly transition away from fossil fuels and demonstrate that economic prosperity is possible without them, it would change the global conversation about climate action.

Technology and Solutions: What's Available Now

When people talk about climate solutions, there's sometimes an assumption that we don't have the technology yet. We need to wait for fusion power or some breakthrough in carbon capture.

That's wrong. We have most of the technology we need. The problem isn't innovation—it's deployment and adoption at scale.

Renewable energy: Solar and wind are the cheapest electricity sources in most of the world now. They're cheaper than fossil fuels. The problem isn't "is solar viable?" It's "how do we replace the entire global energy infrastructure?"

Energy storage: Battery technology is improving. Grid-scale energy storage is deployable now. The challenge is building enough storage capacity and managing the transition from dispatchable fossil fuel power to variable renewable power.

Electric vehicles: EVs are viable and increasingly affordable. The challenge is building charging infrastructure globally and managing the transition of the automotive industry.

Industrial decarbonization: Steel and cement can be produced with lower emissions using electric furnaces and alternative materials. The technology exists. The challenge is that current methods are cheaper due to carbon not being priced into the cost.

Carbon capture: Direct air capture and point-source carbon capture are real technologies. Costs are high—hundreds to thousands of dollars per ton. But the technology works. The challenge is deploying it at billions-of-tons-per-year scale.

Regenerative agriculture: Farming practices that rebuild soil carbon and increase productivity are proven and economically viable. The challenge is transitioning from industrial agriculture at scale.

The pattern is consistent: we have technology. We don't have political will or economic incentives to deploy it at the necessary scale.

The Next Decade: Critical Windows

The next ten years are probably the most critical in human history.

Right now, multiple major tipping points are approaching. The Amazon is within a few years of its threshold. Coral reefs are approaching the point of no return. The Greenland Ice Sheet is approaching instability. AMOC is weakening.

If we take significant action in the next decade—reducing emissions dramatically, protecting and restoring forests, transitioning energy systems—we might still have options. We might still be able to prevent some tipping points.

If we don't take action, if emissions continue on current trajectory, we'll likely see the first major ecosystem tipping points triggered within 10-15 years. Once that happens, the cascade effects become harder to stop.

This isn't doomsaying. This is based on climate models and observations of current trends.

The urgency isn't political rhetoric. It's physics.

Estimated impact scores indicate the potential severity of each system reaching a tipping point, with ocean currents having the highest estimated impact due to their role in global climate regulation.

What Happens After the Tipping Points

Let's be clear about what happens if major tipping points are triggered:

If tropical coral reefs collapse: We lose 25 percent of marine species, disrupting ocean food webs. Hundreds of millions of people lose food security. Tourism economies collapse. Coastal protection disappears—storm surge becomes more damaging.

If the Amazon tips: The world's largest carbon sink becomes a carbon source, adding 150+ gigatons of carbon to the atmosphere. This accelerates warming significantly. The Amazon region becomes savanna—less habitable, less productive, less capable of supporting its population.

If the Greenland Ice Sheet tips: Sea level rises become inevitable. Coastal cities become unlivable within a century. Hundreds of millions of people are displaced. Geopolitical instability increases.

If AMOC collapses: Atlantic hurricane patterns shift. European climate cools while global climate warms. Weather becomes more unpredictable. Agricultural zones shift. Food production is disrupted.

These aren't independent events. They interact. Warming from Amazon collapse accelerates Greenland melting. Greenland freshwater disrupts AMOC, which changes climate patterns globally. Changed climate patterns put more stress on coral, forests, and ecosystems.

Once multiple tipping points activate, the system enters a new state. It's not that the planet becomes 3 degrees warmer and everything is still recognizable—just hotter. The planet becomes a fundamentally different system with different climate patterns, different weather, different ecosystem distributions.

Things we built for the old climate don't work in the new one. Crops don't grow in the same places. Water becomes scarce in some regions and floods others. Migrations happen because some regions become uninhabitable while others become more habitable.

This isn't apocalyptic language. This is what climate scientists are actually saying about outcomes past 2-3 degrees of warming.

The Honest Assessment: Where We Stand

Let's be honest about where we are:

We're not going to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. That window closed when we failed to bend the emissions curve downward by 2020. We're probably locking in 1.7-2.0 degrees of warming, maybe more.

At those levels, some tipping points will almost certainly be triggered. Tropical coral reefs are likely lost. The Amazon will be under severe stress. Greenland will be on the edge or past the edge of runaway melting.

The question isn't whether we avoid all catastrophe. We don't. We can't. Too much carbon is already in the atmosphere. Too much warming is already locked in.

The question is whether we're in a world where tipping points trigger sequentially and we can somewhat manage the impacts, or whether we're in a world where tipping points trigger simultaneously and cascade into systemic collapse.

That difference—managed decline vs. cascading collapse—is still within our control. It depends on what we do in the next 5-10 years.

If we take serious action now, we can probably limit warming to the lower end of the range (1.7-1.8 degrees instead of 2.5-3 degrees). That means losing tropical coral reefs and experiencing severe stress on the Amazon, but possibly avoiding total Amazon collapse and Greenland Ice Sheet runaway.

If we don't take serious action, we trigger cascade effects that make subsequent impacts much worse.

What Global Action Would Actually Look Like

When climate advocates talk about "global action," what does that actually mean in concrete terms?

Energy transition: Every coal plant globally needs to be shut down by 2035. Every natural gas power plant by 2045. Renewable energy needs to scale from current 30 percent of grid to 80 percent by 2035 and 95 percent by 2045. This requires building equivalent to new power plants every single year. Not increasing capacity, not growth—replacement of existing fossil fuel infrastructure.

Transportation: Every vehicle sold globally needs to be zero-emission by 2035. That's 80 million vehicles per year that are zero-emission instead of fossil fuel. Charging infrastructure needs to cover every corner of the planet.

Industry: Steel and cement production needs to shift to electric furnaces or hydrogen-based processes. Chemical manufacturing needs to transition. This requires multi-trillion-dollar capital investment in new industrial plants.

Agriculture: Industrial agriculture needs to transition to regenerative practices. Livestock emissions need to decline. Fertilizer use needs to drop by 50 percent while maintaining food production. This requires a global shift in farming practices.

Forests: Deforestation needs to stop immediately. New forest restoration needs to cover an area the size of the continental US. Every year.

Carbon removal: We need to build industrial carbon removal capacity capable of handling billions of tons per year. That capacity doesn't exist yet and would need to be built from scratch.

When you actually enumerate what needs to happen, the scale is almost incomprehensible. It's not an adjustment. It's a complete restructuring of global energy, transportation, industrial, agricultural, and forest systems. In 20-25 years.

This isn't impossible. Humanity has accomplished massive transformations before. But it requires political will that currently doesn't exist.

The Role of International Cooperation

Climate change is a global problem, but emissions reductions happen at national, regional, and local levels. Getting 195 countries to coordinate action at the necessary scale requires unprecedented cooperation.

The Paris Agreement framework is designed around national commitments (NDCs—Nationally Determined Contributions). Each country sets its own emissions reduction targets. But those targets add up to 2.5-3 degrees of warming, not 1.5 degrees.

The gap between current commitments and what's needed suggests the Paris framework isn't sufficient. We need a ratcheting mechanism that forces more ambitious targets. We need financial mechanisms that help developing countries transition without sacrificing development. We need technology transfer. We need support for the people and regions that depend on fossil fuels economically.

International agreements like the upcoming 2026 UN climate negotiations matter because they set norms, create frameworks, and provide accountability. But ultimately, meaningful action happens domestically.

The challenge is that fossil fuels are cheap, entrenched, and politically powerful. Transitioning away from them requires overcoming that political power.

The Window of Decision-Making

Climate scientists often talk about a "window" of time during which major decisions need to be made. This window is small and closing.

Why does the window matter? Because of inertia in the climate system.

If we made the decision today to eliminate all fossil fuel emissions, the planet would continue warming for decades. Greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere would continue trapping heat. It would take 50-100 years for temperatures to stabilize after we reached zero emissions.

Second, there's economic and infrastructure inertia. If we build a coal plant today, that plant will probably operate for 40-50 years. Every coal plant built delays the transition.

Third, there are tipping points. Some systems have thresholds that, once crossed, commit us to major changes. If the Greenland Ice Sheet becomes unstable, sea level rise becomes inevitable even if we stop emissions.

Because of these forms of inertia, decisions made today determine the state of the planet 50-100 years from now.

If we decide now to rapidly transition away from fossil fuels, invest in forests, and deploy carbon removal, we're on track for a difficult but manageable future.

If we decide to delay, to make incremental changes, to hope that technology saves us, we're on track for a fundamentally different planet with much less capacity to support human civilization as we know it.

That decision point isn't in the distant future. It's now. We're making that decision right now, with every year we maintain fossil fuel infrastructure, with every ton of carbon we emit, with every hectare of forest we allow to be cleared.

Personal and Societal Resilience

One of the uncomfortable realities of climate change is that some impacts are now inevitable. Even in the best-case scenario, even if we made perfect decisions tomorrow, we'd still see significant climate disruption.

This raises questions about resilience at personal and societal levels.

Personal resilience means: What skills, knowledge, and resources would help you weather climate disruption? Do you have access to clean water? Can you grow food? Do you have social networks and community? Can you adapt if your current location becomes less habitable or less economically viable?

Societal resilience means: How robust are the systems that supply your needs? Can your region's food system handle climate variability? Does your region's water supply have redundancy? Is your energy system diversified? Are there economic alternatives if primary industries decline?

For most people, the answer to these questions is: "I don't know, and my society probably isn't resilient."

This isn't defeatism. It's realism. Building resilience doesn't mean giving up on emissions reduction. It means doing both: reducing emissions to limit how bad the crisis gets, and building resilience to handle the impacts that are now unavoidable.

FAQ

What exactly is a tipping point in climate science?

A climate tipping point is a threshold in Earth's climate system beyond which a major change becomes irreversible or self-reinforcing. Below the threshold, the system has resilience and can recover from stress. Above the threshold, the system shifts into a new state that actively resists returning to the previous state. Examples include coral reef ecosystems flipping from hard coral to algal systems, or the Amazon shifting from rainforest to savanna. Once tipped, reversing the change would require major intervention or centuries of recovery time.

How do scientists know when a tipping point is approaching?

Scientists use multiple approaches: long-term monitoring of ecosystem health and climate variables, paleoclimate records that show past tipping points, mathematical models of system dynamics, and statistical analysis of early warning signs. For coral reefs, tipping points are identified through bleaching frequency and recovery capacity. For ice sheets, tipping points are identified through melt rate acceleration. For the Amazon, tipping points are identified through forest dieback rates and moisture cycling changes. These measurements are combined with climate models to estimate the temperature at which tipping becomes likely.

Why is the difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees of warming so significant?

At 1.5 degrees, most tropical coral reefs are severely stressed but some regional recovery is possible. At 2 degrees, tropical coral reefs are essentially lost. Similarly, the Amazon approaches critical stress at 1.5 degrees but may cross the tipping point at 2 degrees. The Greenland Ice Sheet is on the edge of runaway melting at 1.5-2 degrees. The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees determines whether we experience severe impacts or cascading collapse. It's not linear—the tipping points cluster around that temperature range.

Can we still save coral reefs?

Tropical coral reefs can still be partially saved if emissions are reduced aggressively immediately. Cooling the ocean by even 0.3 degrees would extend recovery time between bleaching events, giving reefs a chance to rebuild. However, recovering the 50 percent of the Great Barrier Reef that's already been lost requires active restoration—and even that has low success rates. Some coral populations in the Indo-Pacific region may survive if warming is limited. The realistic goal isn't preserving all reefs, but preserving the maximum number possible given the warming that's already locked in.

What does "carbon removal at scale" actually mean?

Carbon removal means taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and storing it permanently. Direct air capture technology extracts CO2 directly from ambient air. Point-source capture extracts CO2 from industrial emissions. Biological methods like reforestation and soil carbon sequestration capture carbon through natural processes. Scaling to billions of tons per year would require deploying current technology thousands of times larger than current capacity, plus developing new methods. It's technically feasible but economically expensive ($200-400 per ton currently) and not yet deployed at scale.

Why hasn't global cooperation stopped climate change yet?

Climate change involves tradeoffs between current economic interests and future environmental safety. Fossil fuels are entrenched industries with political power in every major economy. Transitioning away from them requires immediate costs (building new infrastructure, managing stranded assets) with benefits distributed over decades and globally. Individual countries face incentives to free-ride (benefit from others' emissions reductions without reducing their own). Additionally, climate impacts are distant in time and abstract in nature compared to present economic interests, making political action difficult. International agreements like Paris are limited by national sovereignty and enforcement mechanisms.

How much would it cost to address climate change adequately?

Estimates vary, but global transition to clean energy and carbon removal would require

What can individuals actually do that matters?

Individual actions that matter include: (1) Reducing personal emissions through transportation and energy choices, which demonstrates demand for alternatives and creates political pressure. (2) Supporting climate-oriented policy and politicians through voting and advocacy. (3) Building community resilience through local food systems and social networks. (4) Divesting from fossil fuels if you have investments. (5) Choosing career paths that contribute to the transition. No individual action solves the problem, but the aggregate of millions of people making different choices shapes markets and politics. The most important individual action is probably political engagement—voting and advocating for systemic change.

What happens to the global economy if major ecosystems collapse?

Ecosystem collapse destabilizes food production, water supplies, and resource availability—the foundations of economic activity. Coral reef collapse means $56 billion in tourism and fisheries revenue vanishes. Amazon collapse means increased atmospheric CO2 and reduced rainfall in agriculture-dependent regions. Ice sheet collapse means migration of hundreds of millions of people, destabilizing geopolitics and economics. Global trade depends on stable climate and resource availability. Major ecosystem collapse doesn't just cause environmental damage—it destabilizes the economic system. Insurance markets price this in, which is why climate risk is increasingly recognized as financial risk.

Are there any technological breakthroughs that could solve this quickly?

No breakthrough technology will solve this problem in time. Fusion power won't be commercially available for 20-30 years. Geoengineering (deliberately cooling the planet through atmospheric interventions) could theoretically reduce warming but would be extremely risky and would not address ocean acidification. Miracle materials or processes might help marginally but won't replace the need for systemic transformation. The solutions to climate change are known: renewable energy, electrification, forest protection, agricultural transition, carbon removal. The barrier isn't technology—it's deployment and political will.

Conclusion: The Reality We're Facing

There's a tendency to approach climate change through one of two lenses: either panic and despair, or optimism about human innovation and adaptation.

Both miss the actual reality.

The actual reality is that we're in the middle of a global crisis that will reshape human civilization. Not end it. Not destroy the planet. But fundamentally reorganize how we live, where we live, what we eat, how we produce energy, how we work.

Some of that reorganization is already happening. Renewable energy is growing. Electric vehicles are accelerating. People are becoming aware of climate impacts. Some countries are making progress.

But it's happening too slowly. The scale of change required is massively larger than current momentum.

The Great Barrier Reef is experiencing mass bleaching events separated by single years, with no recovery between them. That's not a cyclical pattern. That's an ecosystem in the process of transitioning to a new state. Within a decade, without major temperature decline, the reef will probably be functionally dead—transformed from a high-diversity hard coral ecosystem to a low-diversity algal ecosystem.

This is happening now. Not in the future. Now.

The Amazon is within a few years of a tipping point. The ice sheets are destabilizing. Ocean currents are weakening. These aren't projections. These are observations.

What happens next depends on decisions made in the next 5-10 years. If those decisions lead to rapid emissions reductions, we still lose coral reefs and experience severe climate disruption, but we avoid cascading collapse.

If those decisions lead to continued incrementalism, we trigger cascade effects that make subsequent impacts much worse. Within 50 years, we'd be living on a fundamentally different planet with significantly reduced capacity to support human civilization.

That's not alarmism. That's what the science actually says.

The hopeful part is that we still have choices. The tipping points haven't all been crossed. The decisions haven't been made yet. There's a window of time—small, closing, but real—in which action still changes outcomes.

The challenge is whether humanity can muster the political will, economic mobilization, and behavioral change required to actually take that action.

Based on current trends, I'm not optimistic.

But I'm not hopeless either, because the outcome is genuinely undetermined. It depends on choices humans will make. And humans sometimes make good choices, even when they're hard.

Right now, the Earth is approaching critical thresholds. What happens next is up to us.

Key Takeaways

- Global greenhouse gas emissions reached an all-time high in 2024 (0.8% increase from 2023), contradicting Paris Agreement targets requiring emissions decline since 2020

- Tropical coral reefs are at critical risk: the Great Barrier Reef has experienced mass bleaching events six times in the last decade (2016, 2017, 2020, 2022, 2024, 2025), with insufficient recovery time between events

- Six of nine planetary boundaries have already been exceeded, and at least three major tipping points (Amazon, Greenland Ice Sheet, Atlantic Ocean circulation) cluster around 1.5-2 degrees Celsius warming

- For only the fourth time in history, a global coral bleaching event occurred in 2023-24, affecting every ocean simultaneously and indicating the entire planet's oceans exceeded coral thermal tolerance

- Preventing catastrophic cascading collapse requires reducing global fossil fuel emissions by over 5 percent annually through 2050 AND removing 5+ billion tons of CO2 from the atmosphere yearly—massive systemic transformation requiring unprecedented global cooperation

Related Articles

- Home Chef Promo Codes & Coupons: Save 50% Off [2025]

- Sauron Home Security: Premium AI Security for Wealthy Customers [2025]

- Optical Glass Storage: 500GB Tablets Reshape Data Archival [2025]

- Beelink ME Pro NAS: Compact Modular Storage [2025]

- Mini-ITX Motherboard with 4 DDR5 Slots: The AI Computing Game-Changer [2025]

- Top Garmin Smartwatch Features to Expect in 2026 [2025]

![Earth's Environmental Tipping Point: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/earth-s-environmental-tipping-point-what-you-need-to-know-20/image-1-1767004938181.jpg)