Introduction: The Glass Revolution in Data Storage

We're running out of space. Not physical space, but the ability to store the staggering amounts of data our world generates every single day. Cloud servers are exploding in power consumption. Hard drives are hitting physical limits. Tape systems, once considered archaic, have made a surprising comeback in data centers. But none of these solutions feel quite right for the massive archival challenge ahead.

That's where optical glass storage comes in. And right now, scientists are making breakthroughs that could fundamentally change how we think about preserving data for centuries.

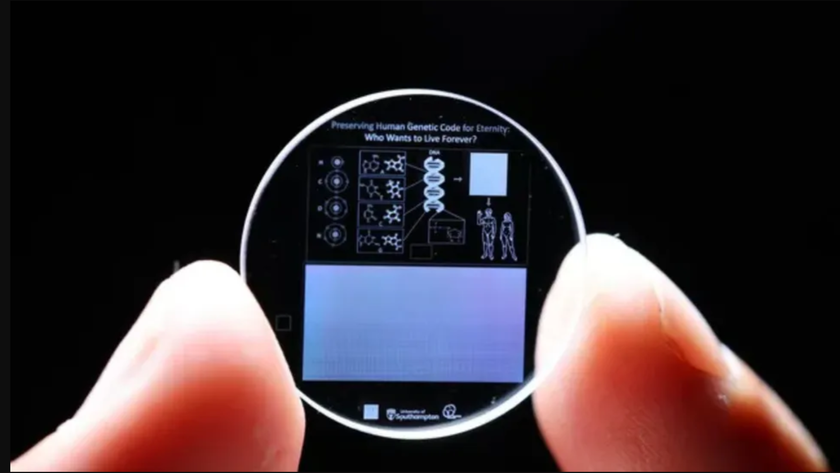

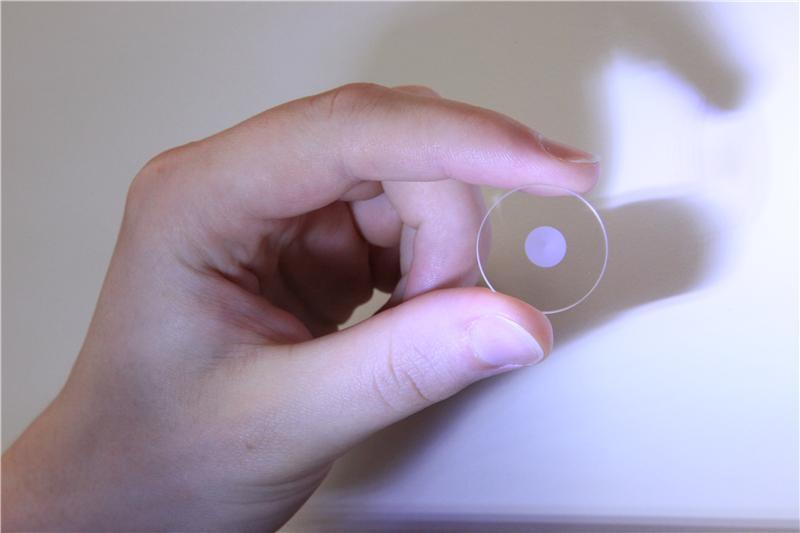

Imagine a storage medium the size of a postage stamp that holds 500 gigabytes of data. Not in some exotic laboratory environment, but at room temperature, without exotic cooling systems or expensive equipment. That's not science fiction anymore. Researchers at the University of South Australia are developing exactly this technology, with a 500GB proof-of-concept medium planned for 2026.

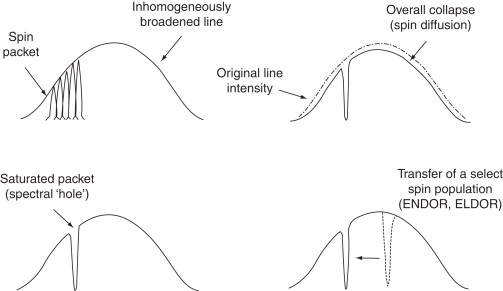

The approach is radically different from what most of us understand about data storage. Instead of etching physical marks with femtosecond lasers or magnetic manipulation, scientists are using photoluminescence and spectral hole burning to encode information directly into the atomic structure of glass. The data sits there, stable and utterly safe from electromagnetic interference, heat fluctuations, or mechanical failure.

Here's what makes this particularly compelling: the technology operates at room temperature using relatively inexpensive lasers. It doesn't require the billion-dollar infrastructure of cloud data centers or the consumables cost of tape systems. It's passive, meaning once data is written, it doesn't degrade through normal use. The environmental footprint is minimal.

But it's not perfect yet. Read and write speeds remain unknown. The real-world durability under repeated access cycles hasn't been proven. Manufacturing at scale is still theoretical. Cost projections are either wildly optimistic or suspiciously absent from technical discussions.

This article dives deep into how optical glass storage actually works, why it matters for the future of data preservation, what challenges remain before commercialization, and how it compares to competing archival technologies. We'll explore the science behind spectral hole burning, examine the timeline toward practical implementation, and analyze whether this technology will actually deliver on its promises.

The stakes are enormous. Global datasphere is projected to reach 175 zettabytes by 2025. Data centers consume roughly 2-3% of global electricity. Long-term archival storage costs add up to billions annually for enterprises. If optical glass storage can deliver even a fraction of what researchers claim, it could reshape not just how we store data, but how we think about information preservation itself.

TL; DR

- 500GB glass tablets represent the first proof-of-concept milestone, targeting 2026 launch from Australian research team led by Dr. Nicolas Riesen

- Spectral hole burning technology encodes data by manipulating nanoscale imperfections in phosphor crystals using specific laser wavelengths

- Room temperature operation with modest power requirements makes optical storage dramatically different from competing femtosecond laser alternatives

- Multi-bit encoding enables SLC, MLC, and TLC-style data density similar to NAND flash, though real-world read speeds and durability remain unproven

- Timeline projections suggest 1TB capacity by 2027 and multi-terabyte systems by 2030, but commercialization depends entirely on manufacturing partnerships and cost feasibility

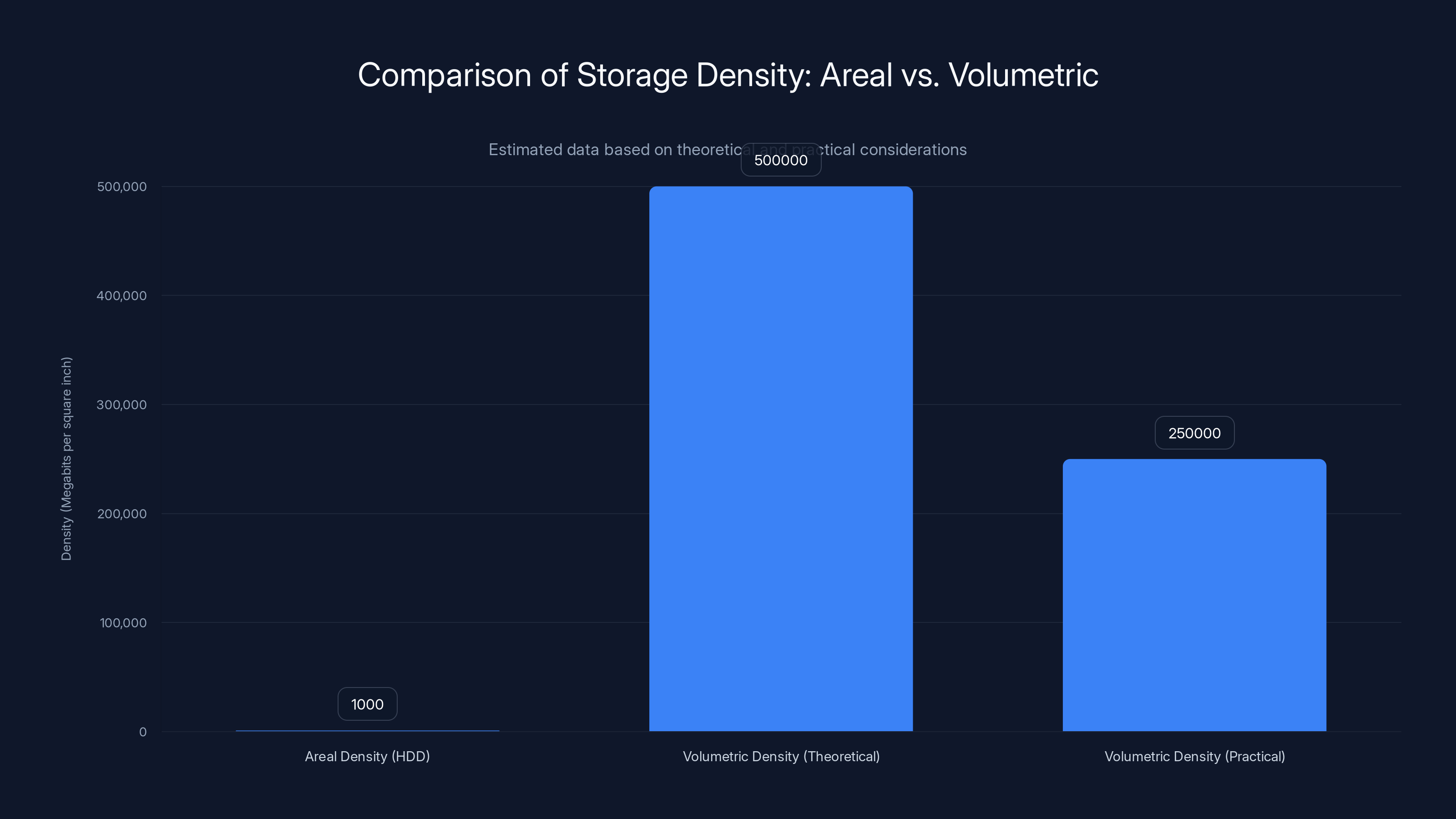

Volumetric storage theoretically offers 500 times the density of traditional areal methods, but practical limitations may reduce this to half. Estimated data.

How Optical Glass Storage Actually Works: The Physics Behind the Promise

The Core Technology: Spectral Hole Burning Explained

When you hear "optical storage," your mind probably jumps to CDs or DVDs. Physical pits, readable by laser. That's not what's happening here, and understanding the difference is critical to grasping why this technology matters.

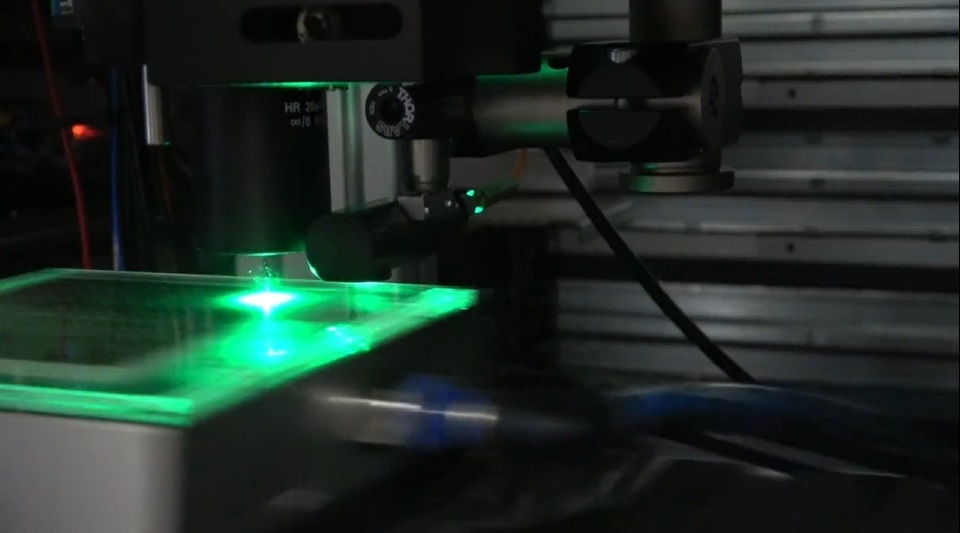

Optical glass storage using spectral hole burning works at the atomic scale. Imagine a crystal material doped with rare earth ions—in this case, divalent samarium ions embedded in a mixed halide phosphor (specifically Ba₀.₅Sr₀.₅FX: Sm²⁺). The crystal lattice has nanoscale imperfections. These imperfections determine how the material absorbs and emits light at specific wavelengths.

When a narrow-bandwidth laser scans the material, it selectively changes these atomic-scale imperfections in regions corresponding to data bits. You're not physically reshaping anything. You're not creating pits or holes. Instead, you're manipulating the electronic states of the material so that it absorbs or reflects light differently at that specific wavelength.

During readout, another laser passes through those same regions. Where imperfections have been altered, the material either emits photoluminescence (light) or suppresses it. Emitted light = 1. No light = 0. Binary information encoded directly into atomic structure.

This is fundamentally different from every magnetic or mechanical storage technology that came before it. There's no moving parts. There's no head reading from a spinning platter. There's no electromagnetic field that can be disrupted. The data literally cannot degrade through normal environmental interference.

Multi-Bit Encoding: Why Density Matters

Storing one bit per physical location gets you from point A to point B, but it doesn't unlock the kind of densities needed for truly transformative archival storage. That's where multi-bit encoding enters the picture.

Researchers are describing an approach where data density increases by encoding information through variations in light intensity rather than just binary on-or-off states. Think of it like this: instead of a light switch that's either on or off, you have a dimmer. Off = 0, dim = 1, medium = 2, bright = 3. Suddenly, you're storing multiple bits in the same physical location.

The technical jargon mirrors NAND flash terminology: SLC (single-level cell, 1 bit per location), MLC (multi-level cell, 2 bits per location), and TLC (triple-level cell, 3 bits per location). By leveraging variations in photoluminescence intensity, optical glass storage could theoretically achieve similar density improvements.

But here's the catch that nobody talks about loudly: moving from laboratory measurements of light intensity variations to repeatable, error-tolerant reads at scale remains completely unproven. Real-world noise, manufacturing variations, and degradation under repeated access could make multi-bit encoding far more fragile than binary approaches. The research documentation presents this as solved, but practical proof is still missing.

Material Science Foundation: Why Ba₀.₅Sr₀.₅FX: Sm²⁺ Works

The choice of material isn't random. It's built on decades of existing research in computed radiography imaging plates, where photostimulated luminescence is thoroughly understood. This phosphor compound has a proven track record in industrial and medical imaging applications.

The physics works like this: the barium-strontium fluorohalide host matrix provides a stable crystalline environment. The samarium ions (Sm²⁺) provide the electronic states that absorb and emit light at useful wavelengths. Nanoscale imperfections in this lattice—essentially tiny defects—determine the specific wavelengths at which absorption and emission occur.

The elegance lies in controllability. By carefully managing laser wavelengths and intensities during the writing process, researchers can create persistent changes in how the material interacts with light. These changes don't require the material to hold a charge (unlike flash memory), don't involve moving parts (unlike hard drives), and don't degrade from thermal fluctuations (unlike magnetic tape).

Where the material science breaks down is in manufacturing consistency. If every glass tablet has slightly different optical properties due to variations in dopant concentration or crystal defects, reading and writing become problematic. You'd need extensive calibration for each medium. That's not a showstopper, but it's a manufacturing reality that lab demonstrations don't always address.

The Research Timeline: From Disc Experiments to Tablet Proof-of-Concept

Evolution of Dr. Nicolas Riesen's Work

The 500GB glass tablet project didn't emerge from nowhere. It grew out of earlier research into spectral hole-based optical storage using different nanoparticle materials. Dr. Nicolas Riesen's academic trajectory shows a deliberate progression from exploring the fundamental physics to scaling toward practical implementation.

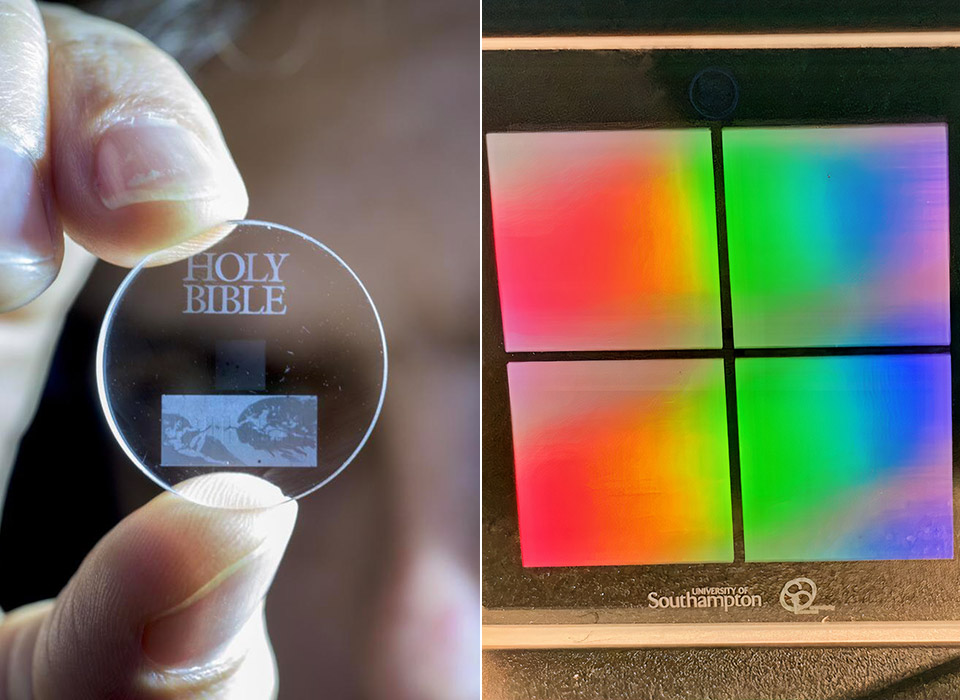

Earlier work explored various phosphor materials and examined how spectral hole burning could be applied to different media formats. Disc-based prototypes provided initial proof-of-concept but hit density and manufacturability constraints. The shift toward glass tablets represents a strategic decision to optimize for capacity rather than format compatibility.

This progression matters because it shows the team isn't jumping blindly from theory to production. Each stage builds on verifiable results from the previous stage. However, each stage also introduces new variables. Going from disc to tablet changes thermal management, changes how the read-write optics must be configured, and changes manufacturing requirements.

The 2026 Milestone and Beyond

The 500GB proof-of-concept medium is scheduled for 2026. That's not a final product. It's a demonstration that the technology can scale from laboratory samples to something closer to a real usable medium. A thousand gigabytes in a small glass tablet would prove the capacity math works out.

From there, the roadmap targets 1TB by 2027 and "several terabytes" by around 2030. These are research milestones, not shipping products. There's a massive difference. A research milestone means "we achieved this in our lab." A shipping product means "you can buy this at a reasonable cost with warranties and support."

The timeline matters because it reveals how conservative or optimistic the team is being. These targets seem reasonable given incremental improvements in laser technology and optical engineering. But every year of delays becomes a year that competing archival technologies (tape, new disk formats, potentially quantum storage) improve in parallel.

Commercialization Dependencies

Making the leap from proof-of-concept to actual products requires manufacturing partners. You need someone who can produce glass tablets at scale with consistent optical properties. You need standardized formats and interfaces. You need error correction algorithms proven in real-world conditions.

None of that exists yet. Which is fine for research. It's not fine if you're an enterprise considering this technology for your next-generation archival strategy. The team's documentation explicitly states that commercialization depends on manufacturing partners and cost feasibility. Translation: they have a working prototype, not a ready-to-manufacture product.

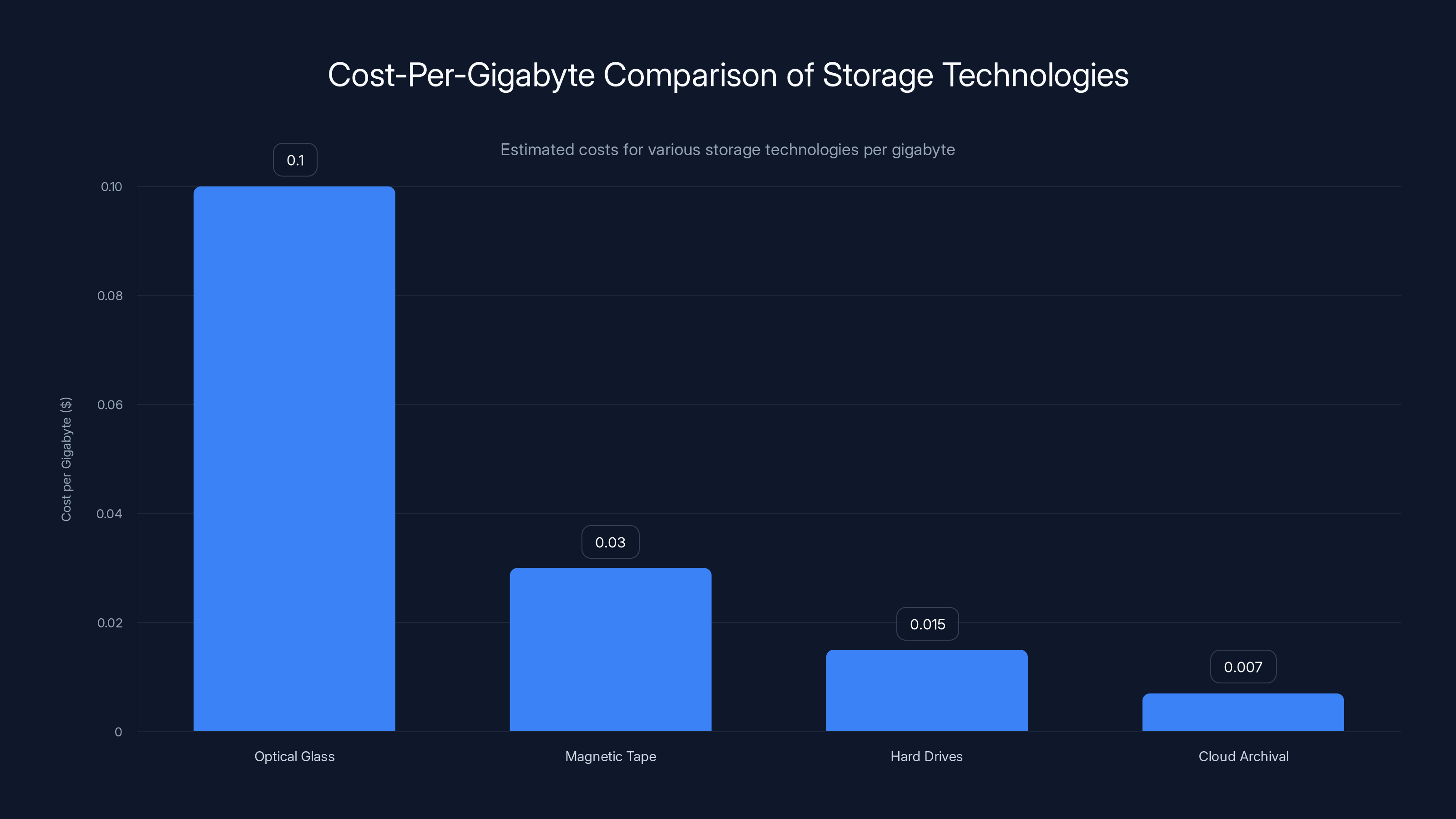

Optical glass storage is estimated to cost

Technical Challenges That Nobody's Talking About Loudly

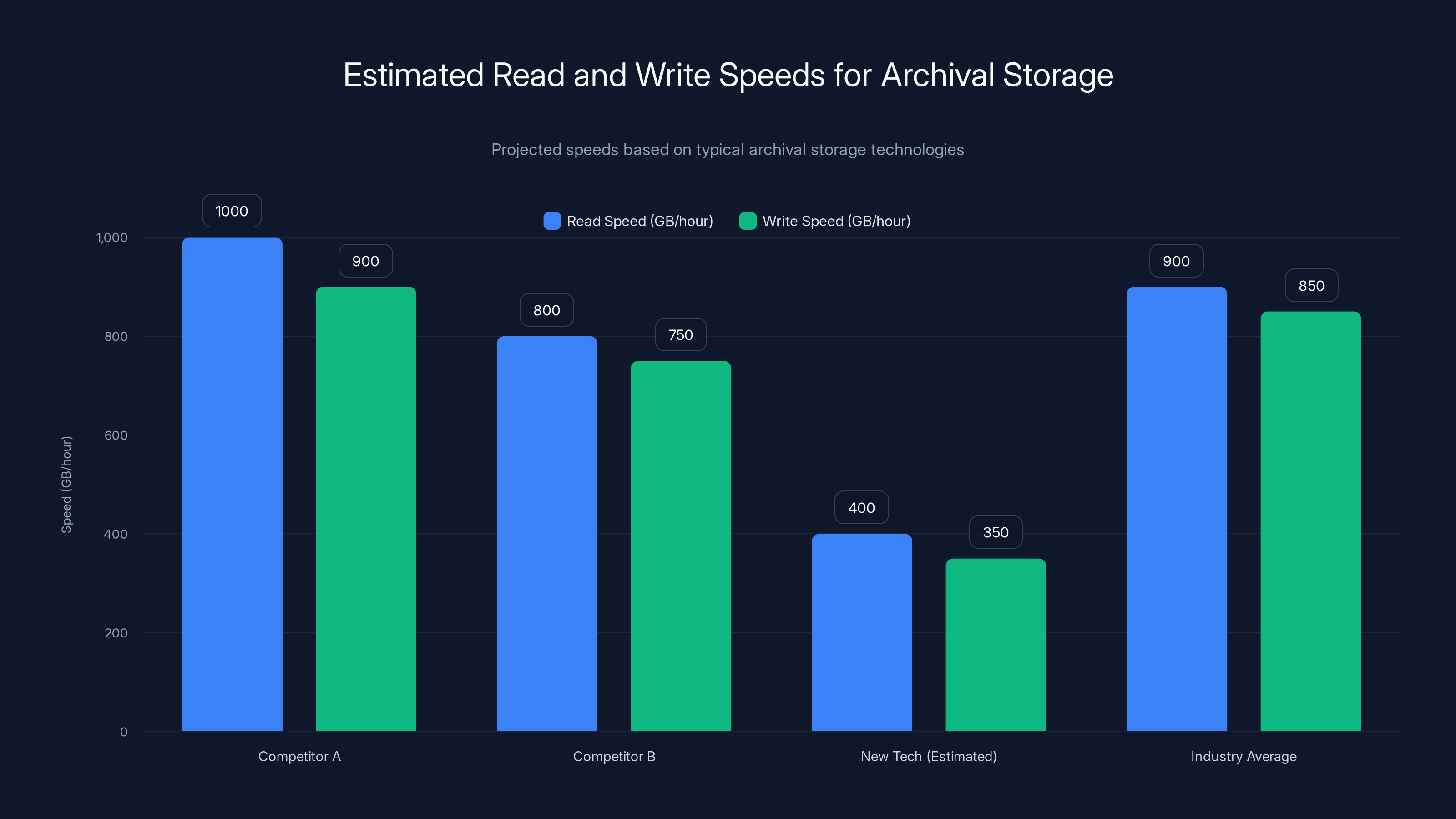

Read and Write Speed Mysteries

Let's be direct: nobody outside the research team actually knows how fast this technology reads and writes data. The technical documentation doesn't specify throughput in megabytes per second or gigabytes per hour. That's not an accident. It's probably because the current speeds are slower than competitors, and publishing those numbers would immediately affect the technology's perceived viability.

For archival storage, speed is less critical than for active working storage. If a system takes an hour to write 500GB, that might be acceptable for long-term archives accessed once per year. But if reads are equally slow, recovery from a disaster becomes impractical. Enterprise backup strategies rely on the ability to retrieve data within hours, not days.

The problem scales exponentially. If each terabyte requires hours to write, multi-terabyte systems become impractical for any use case requiring regular updates or additions. Research teams sometimes gloss over this by focusing on capacity metrics and ignoring throughput entirely.

Durability Under Repeated Access

The research assumes the data remains stable indefinitely once written. That's probably true. But what happens when you read that data repeatedly? Does the repeated scanning degrade the material? Does it introduce noise into the photoluminescence signal?

For archival storage, this seems like an obscure concern. You write once, read occasionally. But consider modern backup workflows where archives are tested monthly to verify integrity, where data is migrated from old systems to new systems every few years, where compliance audits might require reading terabytes of historical data.

Each read operation introduces optical stress. Cumulative stress could gradually degrade the signal-to-noise ratio. Real-world testing over months and years would be necessary to prove this isn't a problem. Laboratory testing spanning days doesn't answer the question.

Manufacturing Consistency and Calibration

Phosphor crystals are finicky. Manufacturing 500GB tablets with identical optical properties across millions of units introduces complexities that laboratory scale doesn't face. Dopant concentration variations, crystal defects, and substrate properties all affect the material's behavior.

One approach is to thoroughly calibrate each tablet during manufacturing. Test read-write operations, characterize its specific optical properties, and pre-program those parameters into the reading device. That works, but it adds cost and complexity to every single medium produced. At scale, that becomes expensive and potentially unreliable if the calibration itself is imperfect.

Alternative approaches involve developing materials with dramatically better inherent consistency. That's an unsolved materials science problem. It's solvable, but it's not solved yet.

Error Correction and Data Reliability

Magnetic tape uses sophisticated error correction codes to protect data despite inevitable read errors. Hard drives have similar mechanisms. Optical storage would need equivalent or better error correction. That adds computational overhead during reading, requires redundant bits to be stored (reducing effective capacity), and introduces recovery latency when errors occur.

For 500GB media, if error correction requires 5% redundancy, you've just lost 25GB of usable capacity. Multiply that across hundreds or thousands of archived tapes, and you're talking about significant wasted storage potential. The research doesn't detail error rates or error correction overhead, both critical to understanding real-world capacity.

Comparing Optical Glass to Competing Archival Technologies

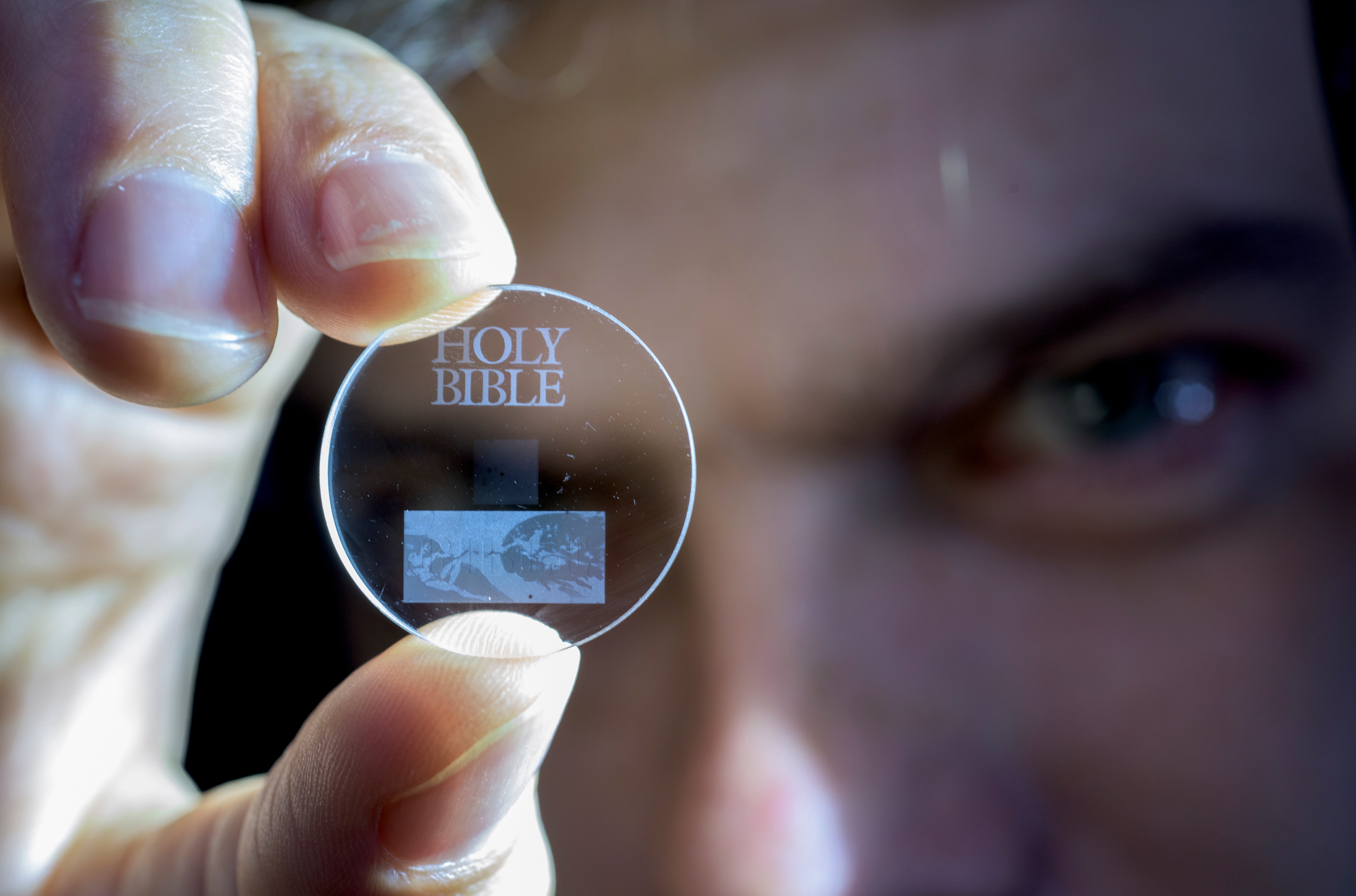

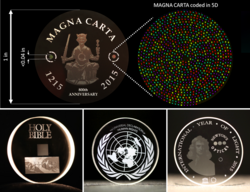

Optical Glass vs. Project Silica (Microsoft's Approach)

Microsoft's Project Silica uses femtosecond lasers to create three-dimensional structures within fused silica glass. Data is written as tiny voids or refractive index changes at multiple depths. Reading involves carefully scanning through different focal planes and reconstructing the data.

Optical glass using photoluminescence takes a completely different approach. No physical changes to the medium. No femtosecond laser requirements. No focal plane complexity. The trade-off is that photoluminescence requires more precise wavelength control and may be more sensitive to environmental variations.

Project Silica's advantage is proven durability. Thousands of years of fused silica stability is well-documented. The disadvantage is cost. Femtosecond lasers are expensive, and the write process is relatively slow. Optical glass storage with photoluminescence potentially offers faster writes and lower equipment cost, but the durability assumptions are newer and less proven.

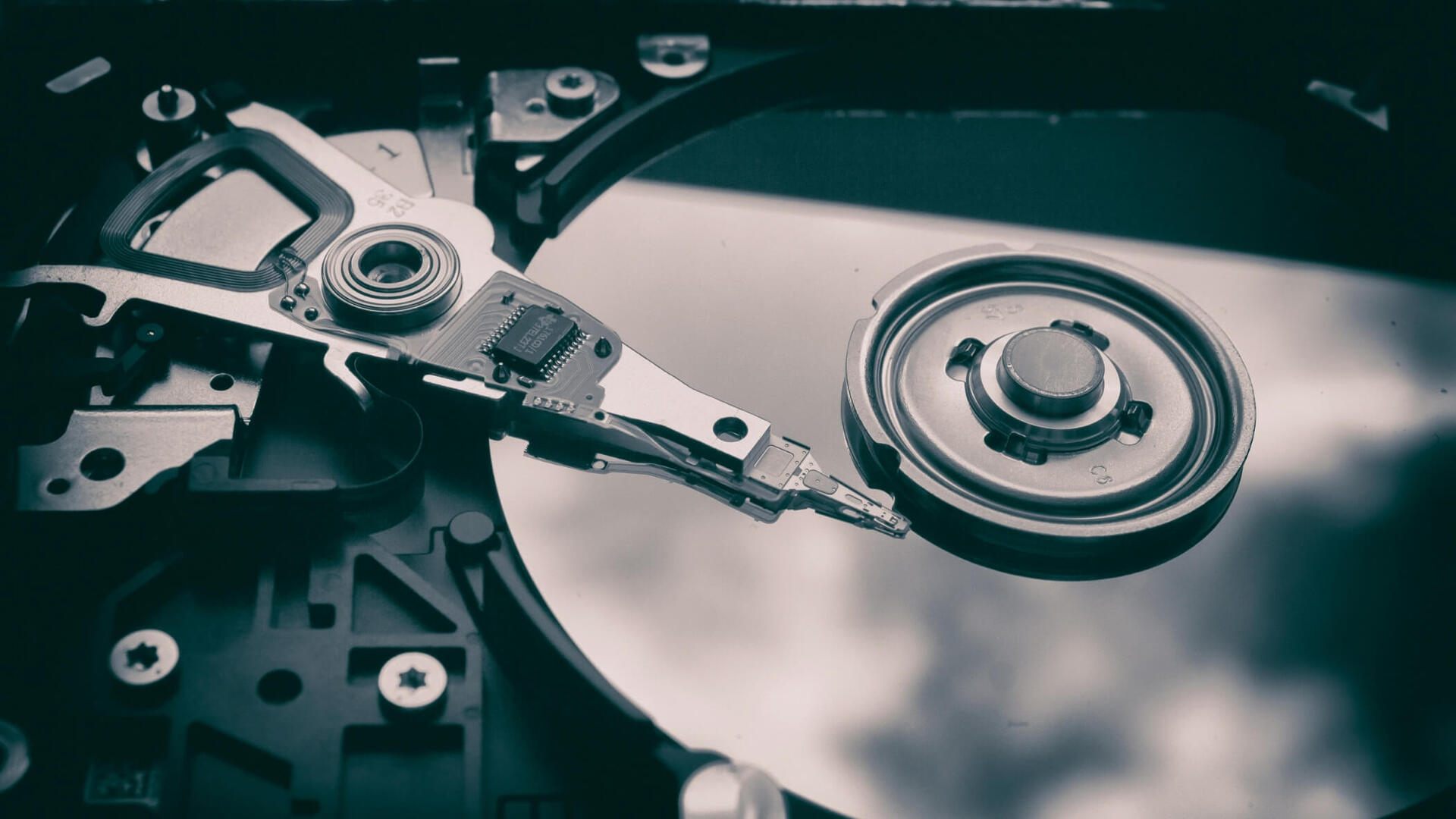

Optical Glass vs. Advanced Magnetic Tape

Modern magnetic tape in enterprise data centers still offers the lowest cost-per-gigabyte for long-term archival. New developments like Advanced Physical Format (APF) achieve densities approaching petabytes per cartridge. Tape doesn't require electricity once stored, making it ideal for offline archival.

The problem with tape is environmental sensitivity. Temperature fluctuations, humidity variations, magnetic field interference, and physical handling all pose risks. Tape also requires specialized equipment to read and write. If magnetic tape standards become obsolete (think 8-track cartridges), accessing old data becomes impossible even if the physical medium survives.

Optical glass storage eliminates many of these environmental concerns. However, it's not truly passive once you need to read the data back. You still need optical equipment, which is more specialized than tape drives and less standardized.

Optical Glass vs. Hard Disk Drives

Hard drives continue improving in density and cost. Enterprise-grade drives hold 20+ terabytes. The industry continues optimizing them for capacity growth. For active archival where data is accessed regularly, hard drives remain superior because of read speed and random access capabilities.

But hard drives aren't designed for multi-decade storage. Mechanical components degrade. Magnetic information gradually loses coherence. Standards change. After 10-15 years, mechanical hard drives become questionable for data you need to keep for 50+ years.

Optical glass wins on the longevity axis by an enormous margin. It loses on the active-access axis because read speeds are almost certainly slower. The right technology depends entirely on the use case.

The Physics of Photoluminescence: Why Light Intensity Matters

Understanding Light Emission and Detection

Photoluminescence is the process where a material absorbs photons at one wavelength and emits photons at different wavelengths. The efficiency and wavelength of emission depend on the material's electronic structure and the energy state created by the absorbed photons.

In optical glass storage, the encoded data changes how much light the material emits. A location encoded as "0" might emit very little light under the read laser. A location encoded as "1" might emit brighter light. The detection system measures the intensity difference and reconstructs the original data.

This works because the photoluminescence intensity correlates reliably with the material's modification state. However, intensity measurements are inherently noisier than binary detection. If you're trying to distinguish between "dim" (representing 1) and "medium" (representing 2) rather than "off" (0) and "on" (1), small variations in intensity become problematic.

This is why multi-bit encoding remains experimentally unproven at scale. The mathematics looks good on paper. Real-world implementation introduces noise sources that laboratory measurements haven't fully characterized.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Detection Precision

For reliable data recovery, the difference between distinct signal levels must be much larger than the noise floor. If noise fluctuations can shift a "dim" signal into the "medium" range, you have data corruption.

Sources of noise in optical glass systems include:

- Thermal noise from room temperature fluctuations affecting electron behavior

- Quantum noise from the fundamental randomness of photon detection

- Optical aberrations from dust, scratches, or imperfections in the glass

- Laser stability variations in output wavelength and intensity

- Material variations from batch-to-batch dopant concentration differences

Each of these contributions compounds. Good engineering can minimize them individually, but eliminating them entirely is impossible. The system must be designed such that even with realistic noise levels, different signal states remain distinguishable. Whether optical glass storage achieves this at scale remains experimentally unproven.

Wavelength Dependence and Material Selectivity

The magic of spectral hole burning is that different wavelengths of light interact differently with different defect sites in the crystal. By using a narrow-bandwidth laser at a specific wavelength during writing, you selectively create permanent changes only in material regions that absorb that specific wavelength.

This wavelength selectivity is the key to storing multiple bits in the same physical volume without them interfering with each other. You can write different bits at slightly different wavelengths in the same spot, then read them out selectively by tuning the read laser to specific wavelengths.

But here's the practical challenge: wavelength control must be extremely precise. Laser wavelengths drifting by even a few nanometers could cause read errors. Manufacturing a system that maintains such precision while operating at room temperature with inexpensive lasers requires sophisticated engineering that the research documentation doesn't detail.

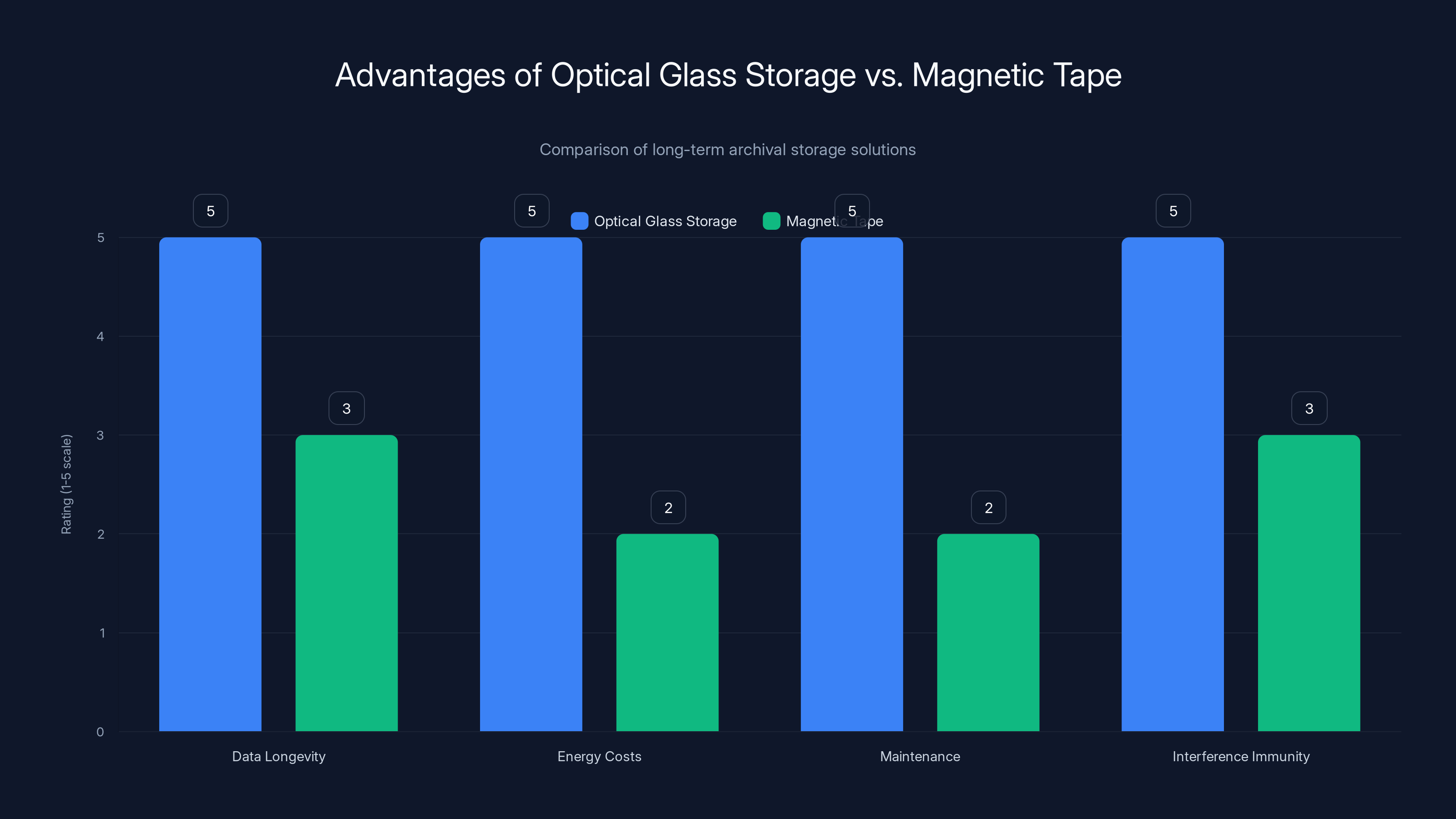

Optical glass storage offers superior longevity, lower energy costs, and better immunity to interference compared to magnetic tape, making it ideal for long-term archival despite higher initial costs. Estimated data.

Power Consumption and Environmental Considerations

Energy Requirements for Writing

Writing data to optical glass requires laser energy to create permanent changes in the material. The amount of energy needed per gigabyte depends on efficiency of the photoluminescence process and how much of the material needs to be modified.

The research suggests relatively modest power requirements compared to femtosecond laser systems. Regular diode lasers operate at kilohertz to megahertz frequencies with reasonable efficiency. Early estimates suggest writing 500GB might require power levels comparable to traditional optical drives.

However, no published specifications detail the actual energy consumption. Is it 100 watts? 1000 watts? For how long during the write process? These details matter enormously for deployment scenarios. If writing 500GB requires running a system at high power for hours, the electricity cost and heat dissipation become significant for large-scale data centers.

Passive Storage and Zero Standby Power

Once data is written, optical glass storage requires zero power for retention. You can physically remove the medium from the reader and store it in a closet. The data persists indefinitely without any electrical connection. This is a massive advantage over cloud storage or powered data centers.

For compliance-driven archival, where data must be retained for decades but accessed rarely, this passive nature is transformative. Instead of running servers 24/7 to preserve archived data, you physically store tablets and retrieve them only when needed.

The environmental calculation becomes striking. A terabyte of data on optical glass tablets, stored offline, has essentially zero energy footprint for storage. The same terabyte in a cloud data center with typical energy usage patterns consumes roughly 5-10 watts continuously. Over 20 years, that's equivalent to lighting a moderate bulb constantly, just for data preservation.

Data Center Integration and Heat Management

When actively writing to optical glass, the system generates heat. Optical equipment generates more heat than mechanical storage (surprisingly) because laser systems are often not particularly efficient converters of electrical energy to optical energy.

The claim of "room temperature operation" is somewhat misleading. The material can be read and written at room temperature without requiring cryogenic cooling or exotic thermal management. But the readers and writers themselves generate heat that must be managed.

For data centers deploying this technology, integration with existing cooling infrastructure becomes necessary. That's not a barrier, but it's not a trivial detail either. Every write system deployed requires cooling consideration.

Storage Density Calculations: From Theory to Practice

Volumetric vs. Areal Density

Traditional storage—hard drives, SSDs, magnetic tape—uses areal density (megabits per square inch) as the key metric. You write on a 2D surface and calculate how many bits fit per square inch.

Optical glass storage potentially uses volumetric density. By encoding data at different depths within the glass through wavelength variations, you theoretically store multiple bits in the same square inch of area, just at different depths or different wavelength channels.

The 500GB proof-of-concept in a glass tablet is said to be roughly the size of a postage stamp. A standard postage stamp is about 1 square inch. If 500GB fits on 1 square inch through volumetric encoding, that's roughly 500 gigabits per square inch, which is 500,000 megabits per square inch. For comparison, modern hard drives achieve around 1,000 megabits per square inch with areal density alone.

The math seems to work, but the question is: does volumetric encoding actually achieve these theoretical densities in real hardware? Or do error rates, multi-bit encoding limitations, and practical manufacturing constraints cut the effective density in half? Nobody outside the research team has tested this.

Scaling Laws and Manufacturing Reality

Lab demonstrations often achieve theoretical performance in carefully controlled conditions. Scaling to millions of units reveals problems that don't exist in small batches. With optical glass storage, those scaling problems likely include:

- Consistency: Every tablet must have similar optical properties or require extensive calibration

- Defect rates: Manufacturing defects increase with volume, potentially degrading data reliability

- Thermal management: Consistent cooling across many devices becomes complex

- Wavelength control: Precision laser systems are harder to manufacture cheaply than marketing suggests

A 500GB proof-of-concept proves the physics works. It doesn't prove that manufacturing one million tablets with 90%+ reliability and reasonable cost is achievable. That's typically where emerging storage technologies hit the wall.

Real-World Use Cases: Where Optical Glass Storage Actually Makes Sense

Genomic and Scientific Data Archival

Research institutions generate massive datasets that must be retained indefinitely for reproducibility and reference. A single genomic sequencing project might produce terabytes of raw data. Current practice involves storing this on tape in climate-controlled facilities at substantial ongoing cost.

Optical glass storage changes the economics dramatically. Once data is written, it sits completely stable. No periodic migration to new formats as tape standards evolve. No electricity costs for cooling and power. Access speed is slower than cloud storage, but for data accessed maybe twice per year, that trade-off is trivial.

Consider a research university with petabytes of archived data. Annual electricity cost for data center storage might be $500,000+. Optical glass storage would reduce that to essentially zero maintenance cost, paid once at initial write time. Even if optical glass costs three times as much per gigabyte as tape, the economics win over 20-year timeframes.

Government and Legal Records Preservation

Governments and legal systems must preserve documents and records for decades or centuries. Digital preservation is superior to paper (which degrades), but depends on reliable, accessible storage.

Optical glass storage offers advantages: no dependence on vendor formats, extreme longevity, and immunity to magnetic interference or electromagnetic pulse weapons. For critical infrastructure records, this is significant. A digital copy of critical infrastructure diagrams preserved in optical glass survives whatever happens to primary systems.

The slow read speed isn't a concern when accessing archived documents occurs once every few years. The lack of ongoing electricity requirements is an advantage in long-term cost calculations. For government, the psychological comfort of data that physically cannot degrade is worth something beyond pure economics.

Enterprise Backup and Disaster Recovery

Large enterprises maintain backup copies of critical data, often stored offline for protection against ransomware and system failures. Current practice uses magnetic tape in geographically distributed vaults.

Optical glass could enhance these workflows. A critical database backed up to optical glass remains utterly safe. No degradation, no electromagnetic interference, no format obsolescence concerns. If disaster strikes and the primary system must be recovered, the optical glass backup sits ready decades later without degradation.

The trade-off is access speed. Recovering a terabyte of data from optical glass media might require hours instead of the minutes that tape can achieve. For true disaster scenarios where weeks have passed, that's acceptable. For frequent recovery testing or smaller point-in-time recoveries, tape might remain superior.

Long-Term Climate and Environmental Data

Scientific projects collecting environmental and climate data over decades must preserve raw datasets indefinitely. Modern climate science depends on comparing data collected 50 years ago with current measurements. If that historical data is lost or becomes inaccessible, the scientific continuity breaks.

Optical glass storage is ideal for this use case. Write the data once, store it securely, and access it only when researchers need to compare with contemporary data. The slow read speed is negligible when analysis occurs on timescales of months, not seconds.

Estimated data suggests the new technology has slower read and write speeds compared to competitors, potentially affecting its viability for frequent access scenarios.

Cost Economics: What This Actually Costs

Component and Manufacturing Costs

The 500GB glass tablets use materials that are relatively inexpensive: a phosphor compound and glass substrate. The components aren't exotic. The challenge is manufacturing them with sufficient consistency and optical quality to achieve reliable storage.

Laser systems for reading and writing will be the primary cost driver. Narrow-bandwidth tunable lasers are expensive. Desktop laser systems for optical glass reader-writers might cost $10,000-50,000+ per unit. That's not prohibitive for data centers, but it's more expensive than tape drives.

Research documentation doesn't detail expected component costs for production volumes. That's typically because the team hasn't worked through manufacturing at scale and doesn't want to publish optimistic numbers that get ridiculed later.

Cost-Per-Gigabyte Projections

For comparison, modern magnetic tape achieves roughly

Early estimates for optical glass storage range from $0.10-0.50 per gigabyte, assuming manufacturing scales efficiently. Those are rough guesses. Real production numbers could be better or worse by an order of magnitude.

At

Total Cost of Ownership

The right comparison isn't per-gigabyte cost alone. It's total cost of ownership over the retention period.

Consider a scenario: archive 100 terabytes for 50 years.

Magnetic Tape approach:

- Initial cost: 100TB × 3 million

- Refresh cycles (media degrades, data must be migrated): 5 complete migrations × 5 million

- Facility costs: 50 years × 5 million

- Total: ~$13 million

Optical Glass approach (if manufacturing scales as hoped):

- Initial cost: 100TB × 15 million

- Reader-writer equipment: ~$200,000

- Facility costs: minimal (offline storage room): 50 years × 500,000

- Zero refresh cycles required

- Total: ~$15.7 million

They're comparable. The optical glass approach wins slightly on total cost if you believe the per-gigabyte estimates. More importantly, it eliminates the need for periodic data migrations and format updates, which is where most archive projects fail.

Manufacturing Challenges: The Gap Between Lab and Factory

Precision Laser Systems at Scale

Building one optical glass reader-writer in a laboratory is manageable. Building 10,000 units per year with identical specifications is a different beast entirely.

Laser systems require precise alignment and temperature control to maintain wavelength accuracy. Manufacturing processes must be standardized to ensure every unit performs identically. Quality control becomes complex—you can't test every unit exhaustively without consuming enormous amounts of time.

Historically, optical technologies have struggled with this scaling challenge. CD manufacturing solved it through automation and standardization, but that took decades. Blu-ray never achieved the volume needed to dramatically reduce per-unit costs because hard drives were cheaper and simpler.

Optical glass storage has the same challenge. If read-write systems cost more to manufacture than tape drives, the cost-per-gigabyte advantage disappears.

Glass Substrate Consistency

Not all glass is created equal. Purity, dopant concentration, crystal structure, and thermal stability all vary with manufacturing processes. Achieving the optical properties needed for reliable multi-bit encoding requires extremely consistent glass.

Existing glass manufacturers aren't optimized for these specifications. Building the capability requires substantial R&D investment and manufacturing infrastructure. That's capital-intensive and risky—what if the approach doesn't scale?

The research team's solution is presumably to partner with an established optical materials manufacturer. But those companies aren't motivated to optimize specifically for optical storage unless large-scale demand exists. It's a chicken-and-egg problem.

Standardization and Cross-Manufacturer Compatibility

Magnetic tape succeeded partly because it became standardized. Different manufacturers could produce compatible cartridges. Users could choose between vendors. Competition drove down costs while maintaining compatibility.

Optical glass storage currently has zero standardization. There's one research team, one approach, one set of specifications. If commercialization happens through a single company, lock-in becomes inevitable. Competing implementations would be incompatible, making the technology fragmented and less attractive to enterprises.

Establishing open standards before significant manufacturing investment would be smart, but research teams rarely prioritize that. It typically happens only after the technology is proven commercially viable—at which point it becomes a negotiation between competing interests rather than a collaborative effort.

Comparison Table: Optical Glass vs. Other Archival Technologies

| Metric | Optical Glass | Project Silica | Magnetic Tape | Hard Drives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity per unit | 500GB-2TB | Unknown | 15-20TB | 20-24TB |

| Read speed | Unknown (likely slow) | Unknown | 140 MB/s | 250+ MB/s |

| Write speed | Unknown (likely slow) | Unknown | 140 MB/s | 250+ MB/s |

| Durability claim | Centuries (unproven) | 10,000+ years | 30-50 years | 5-10 years |

| Power requirement (passive) | Zero | Zero | Zero | Zero |

| Power for read-write | Modest | High (femtosecond lasers) | Modest | Modest |

| Cost/GB (estimated) | $0.10-0.50 | Unknown (likely high) | $0.02-0.05 | $0.01-0.02 |

| Manufacturing readiness | Lab stage | Lab stage | Production-ready | Production-ready |

| Standards defined | No | No | Yes (LTO) | Yes (SATA/SAS) |

| Environmental immunity | Excellent | Excellent | Fair | Poor |

| Proof of viability | Proof-of-concept only | Proof-of-concept only | 30+ years deployed | 30+ years deployed |

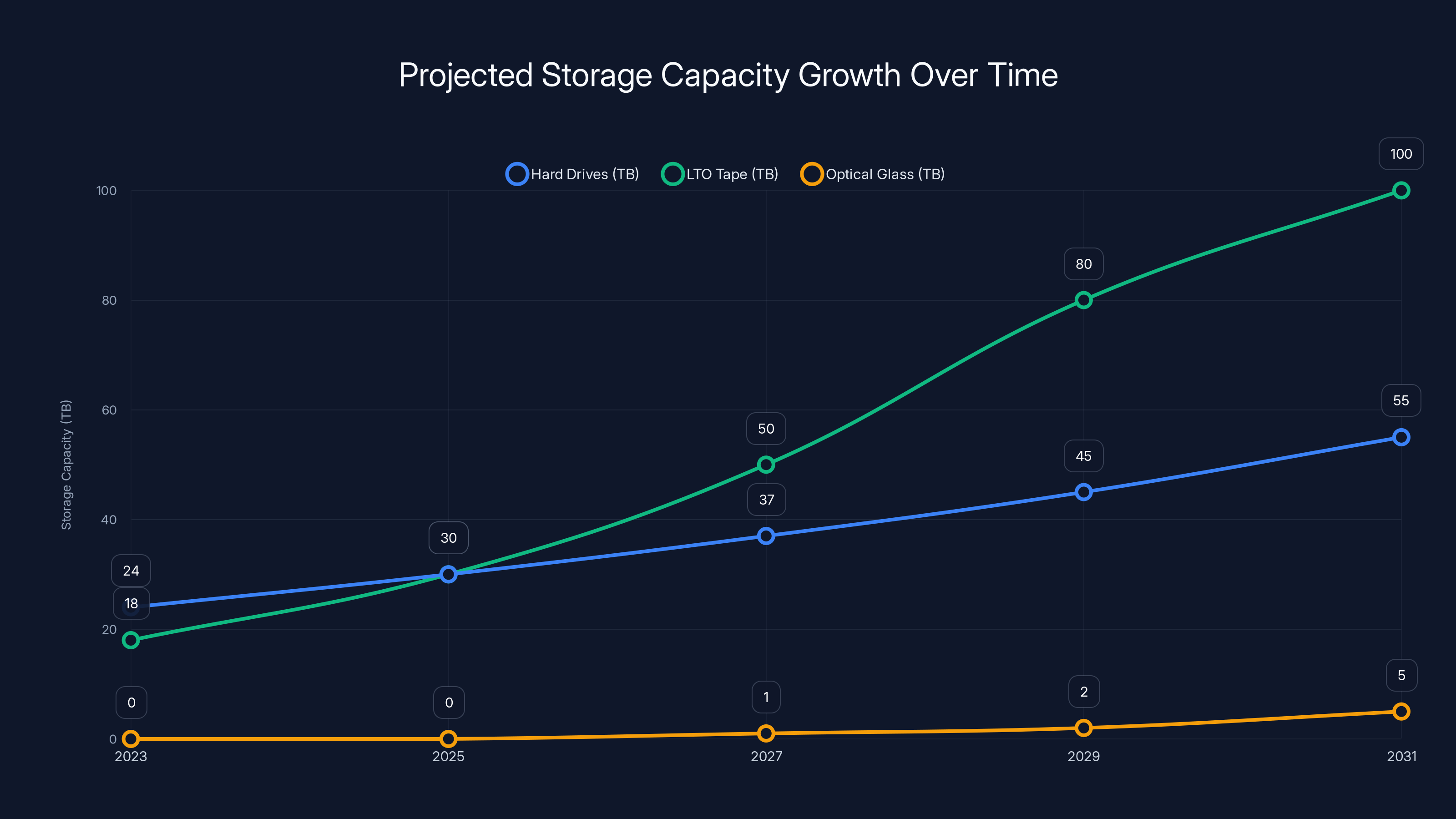

Estimated data shows hard drives and LTO tape significantly increasing capacity over the next decade, potentially outpacing optical glass development.

The Timeline Question: Can This Ship Before Competing Technologies Improve?

Hard Drives Keep Scaling

The storage industry has a tendency to surprise skeptics. When tape was supposed to be obsolete due to hard drive improvements, tape actually increased in use because data growth outpaced drive capacity improvements. The same could happen here.

Hard drives continue improving. Today's 24TB drives will be commonplace within 5 years. Capacity improvements continue at roughly 10-15% annually, with costs declining even faster. By the time optical glass reaches commercialization (5-8 years away optimistically), hard drives might be 50+ terabytes.

This doesn't kill optical glass, but it compresses the capacity advantage that makes the technology compelling. If hard drives achieve multi-petabyte capacities while remaining cheaper per gigabyte, the economics shift dramatically against optical glass.

Magnetic Tape Innovation Continues

Tape manufacturers don't sit still. LTO (Linear Tape-Open) continues advancing. Current LTO generation supports 18TB native capacity with 45TB compressed. Next-generation LTO will push capacity higher still. Industry timelines target 100+TB tapes within 5-10 years.

If tape achieves 100TB cartridges while optical glass is still shipping 1-2TB media, tape remains compelling despite optical glass's longevity advantage. Enterprises care about immediate practical problems (cost, performance) far more than theoretical century-scale durability.

Quantum and Novel Storage Technologies

Beyond conventional approaches, researchers pursue quantum storage, DNA-based storage, and molecular systems. Some of these might leapfrog both optical glass and tape.

DNA storage, for instance, theoretically offers extraordinary density and longevity. Synthetic Biology companies are actively commercializing DNA archival services. If DNA storage becomes practical and cost-competitive within the same timeframe as optical glass, it could define the next generation of archival.

The uncertain landscape means optical glass storage isn't just competing against current technologies—it's racing against innovations happening right now in labs globally.

Expert Analysis: What the Research Actually Claims vs. What's Been Proven

Claims in Research Documentation

The technical publications and project descriptions claim:

- Spectral hole burning enables reliable data encoding

- Multi-bit encoding is feasible

- Room temperature operation is achievable

- Durability exceeds 100 years, potentially centuries

- Energy requirements are modest compared to femtosecond laser approaches

- Manufacturing partnerships are forthcoming

None of these claims are false, but they're expressed at a level of certainty that exceeds what's actually been demonstrated.

What's Actually Been Demonstrated

The research has proven:

- Basic spectral hole burning works in laboratory samples

- Theoretical calculations suggest multi-bit encoding is possible

- The technology operates at room temperature in lab conditions

- Material stability appears to be excellent based on optical properties

- The approach requires less equipment complexity than femtosecond alternatives

Everything else is extrapolation. Real-world proof of manufacturability, reliability at scale, actual error rates, and cost competitiveness all remain experimental.

This is normal for emerging technology. Not a flaw in the research. But it explains why the 2026 500GB proof-of-concept is genuinely significant. It's the first step toward proving the technology can work outside a laboratory.

Adoption Barriers: Why This Might Sit in Labs Forever

Enterprise Risk Aversion

Data archival is not a place enterprises take risks. A new storage technology, no matter how promising, faces enormous skepticism from IT leaders responsible for mission-critical data. Where's the reference customer list? What's the failure mode when data can't be read?

Optical glass storage would need to be boring to get adopted by enterprises. Boring means proven at scale by competitors, documented in industry standards, supported by multiple vendors, and backed by insurance against failure.

Research teams rarely achieve that status because creating boring, standardized technology is tedious compared to publishing novel research papers.

Ecosystem Lock-In Concerns

If optical glass storage is controlled by a single company or research group, enterprises worry about lock-in. What if the company goes bankrupt? What if proprietary formats become unavailable? What if licensing costs skyrocket?

Magnetic tape succeeded partly because multiple manufacturers could build compatible products. Open standards meant customers had choices. Optical glass storage currently has none of that.

Path of Least Resistance

Tape works. Hard drives work. Cloud storage works. They have entire ecosystems of vendors, tools, and support. Switching to optical glass requires new equipment, new training, new vendor relationships, and new risk profiles.

Enterprise IT departments optimize for stability, not innovation. A 10% cost improvement and 1000-year durability don't outweigh the risk and disruption of migrating to a new technology.

Standards and Standardization Gaps

Before widespread adoption, optical glass storage needs formal standards defining:

- Physical media specifications (dimensions, materials)

- Optical interface specifications (wavelengths, power levels)

- Data encoding standards (error correction, multi-bit levels)

- Reliability testing procedures

- Interchange protocols

None of these exist. Creating them requires industry collaboration, which is slow and political. Without them, every optical glass system is proprietary, limiting adoption.

The highest probability (70-80%) is for optical glass storage to succeed in niche markets, while mainstream adoption remains less likely (20-30%). Estimated data.

The Path Forward: What Needs to Happen Next

2026 Milestone: Building the Proof-of-Concept

Successfully delivering the 500GB tablet in 2026 is the critical first step. It proves the technology works at meaningful scale. It provides something tangible that competing research groups and manufacturers can examine.

This milestone matters even if it doesn't directly lead to commercialization. A successful proof-of-concept attracts investment, interests manufacturers, and validates the research trajectory.

Failing to deliver in 2026 doesn't kill the technology, but it pushes timelines back. Every year of delay allows competing technologies to advance. The window of opportunity closes incrementally.

Manufacturing Partnership and Scale-Up

The next critical step is identifying and partnering with a manufacturer capable of scaling production. This requires someone willing to invest significant capital before market demand exists.

Historically, this role has been filled by either established storage companies diversifying their portfolio, or well-funded startups with specialized expertise. Given optical glass storage's niche, a startup seems more likely than a massive incumbent.

The partnership should include commitment to standardization and multi-vendor ecosystem development. Without that, adoption remains limited.

Real-World Durability Testing

Longterm testing with actual tape samples subjected to realistic conditions (temperature cycling, read-write cycles, environmental stresses) is essential. This testing should continue for years, ideally under independent oversight.

Only after genuine durability data emerges can enterprises confidently recommend optical glass for century-scale data preservation. Laboratory stability models are necessary but insufficient.

Open Standards Development

Once the technology matures past proof-of-concept, industry standards organizations should establish formal specifications. This might involve creating new standard bodies or extending existing ones (like the International Organization for Standardization's standards committee for storage).

Open standards don't require manufacturers to reveal proprietary details. They simply define interfaces and compatibility requirements. That's how tape standards work and why tape has succeeded.

Future Capacity Roadmap: When Terabytes Become Practical

Density Improvements and Multi-Depth Encoding

The current 500GB targets use primarily in-plane encoding—writing data at different wavelengths within the same physical region. Future systems could encode data at different depths within the glass, adding another dimension for capacity.

Multi-depth encoding could theoretically multiply capacity by 5-10x for the same footprint. That would push single tablets toward 5-10TB. Achievable? Probably. Proven? No.

2027 Projection: 1TB Tablets

The roadmap targets 1TB by 2027. That represents 2x capacity in a single year—reasonable assuming efficient density improvements. A successful 500GB proof-of-concept would provide confidence in achieving 1TB through straightforward engineering improvements.

2030 Vision: Multi-Terabyte Tablets

By 2030, reaching several terabytes per tablet becomes feasible if density improvements compound. Several terabytes in a glass tablet the size of a postage stamp is genuinely transformative for archival data centers.

These projections assume no major technical barriers emerge during scale-up. That's optimistic but not absurd. Fundamental physics is sound. Engineering challenges are solvable. The question is whether they're solvable fast enough to stay competitive with tape and hard drive improvements happening in parallel.

Alternative Approaches: Other Labs, Other Ideas

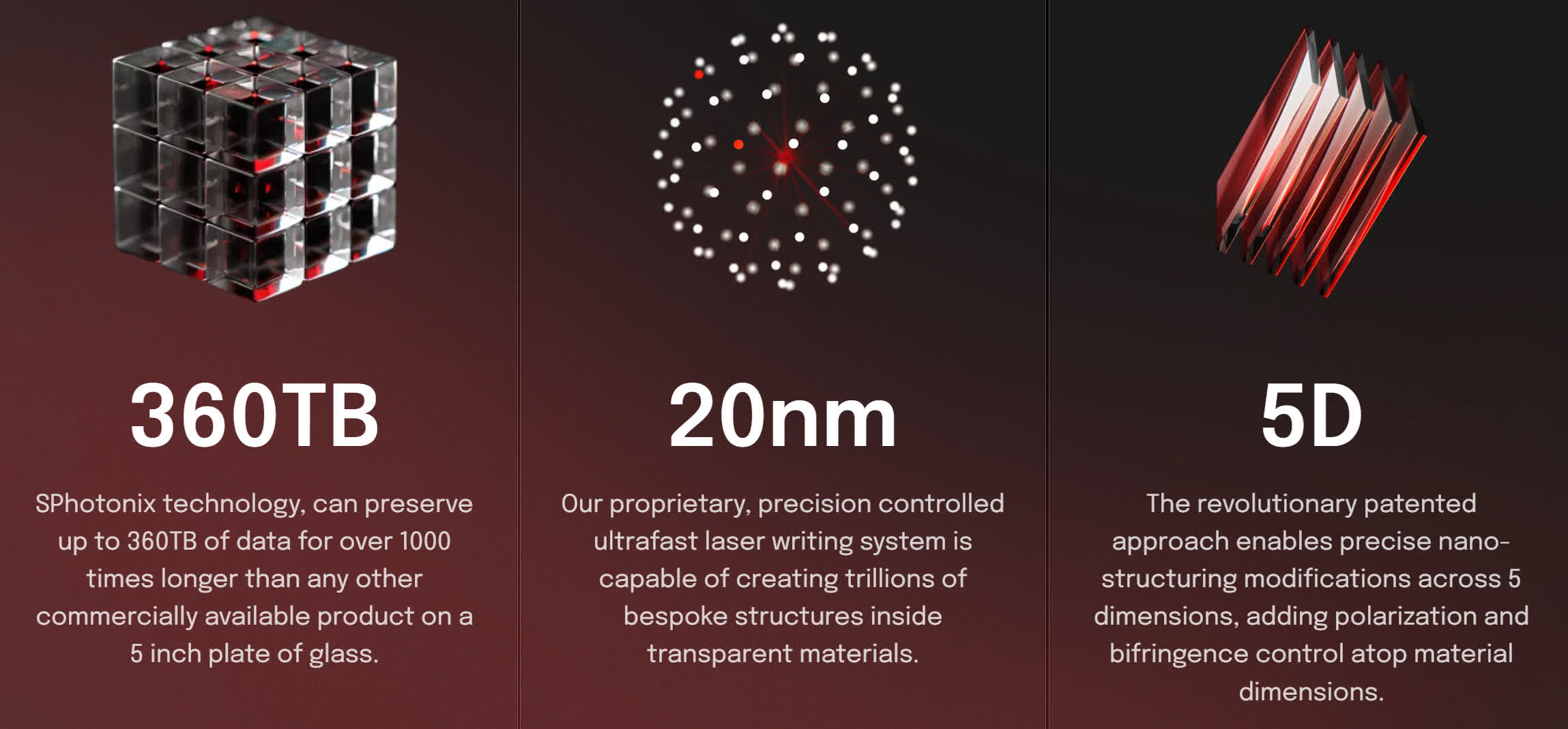

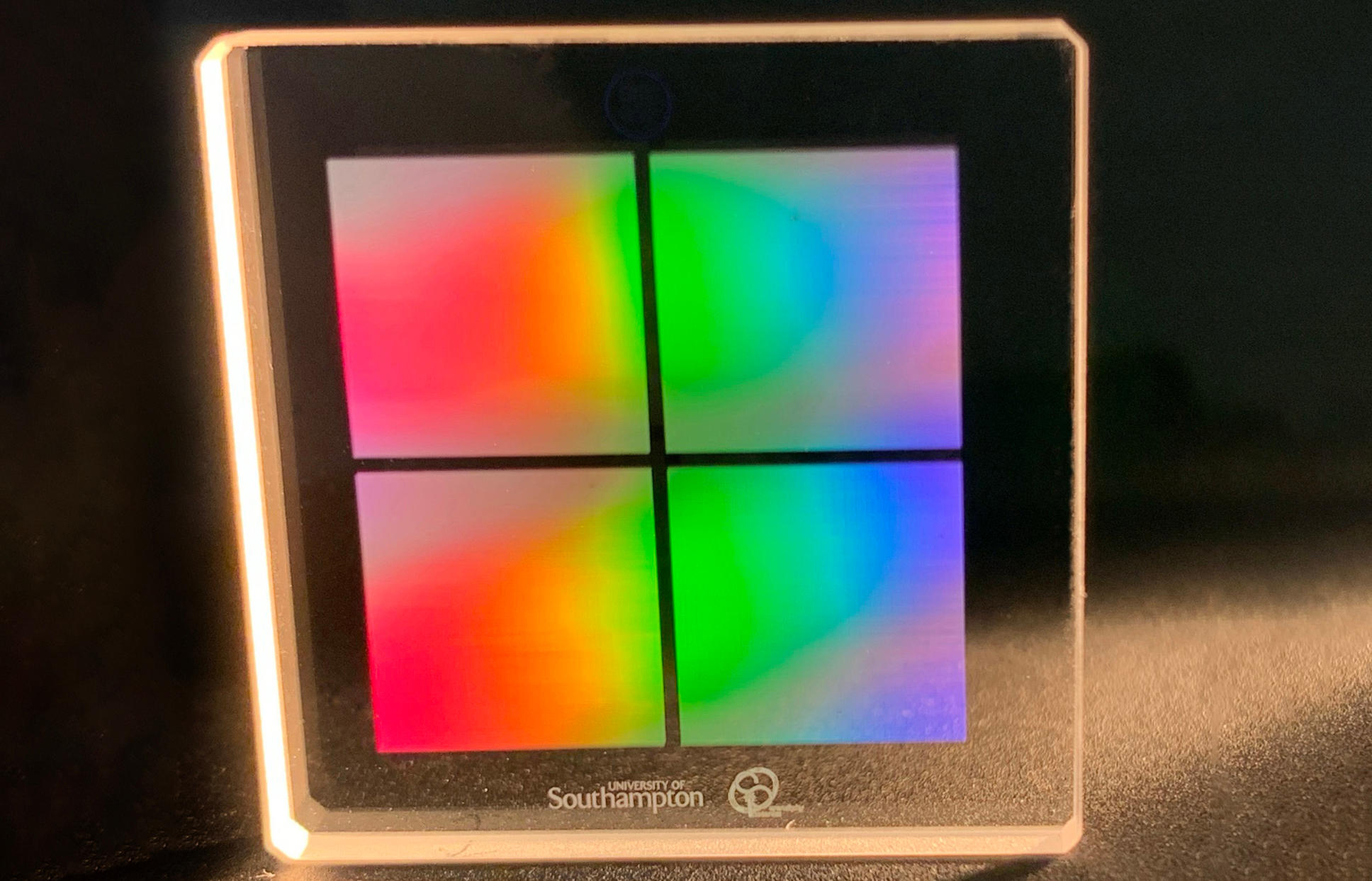

5D Memory Crystal Storage (Different Photonic Approach)

Researchers at University of Southampton developed 5D memory crystal storage using femtosecond lasers to create nanostructures in fused silica. Data is encoded in three spatial dimensions plus two dimensions of polarization and intensity.

This approach offers similar promises to optical glass but uses different physical mechanisms. Femtosecond lasers are expensive and relatively slow, but the technology has been extensively tested. The main barrier is cost, not viability.

Cerabyte's Ceramic Archival Storage

European startup Cerabyte pursues ceramic-based archival storage, also using optical encoding on ceramic substrates. The approach differs in material choice but addresses similar problems.

Cerabyte's advantage is backing from serious investors and explicit commercialization focus. Their timeline targets market-ready systems within the decade, with claims of terabyte capacities and exabyte system capabilities.

The competition is healthy. Multiple approaches increase the probability that at least one succeeds commercially, and competition drives better outcomes than a single monopoly approach.

Molecular and DNA-Based Storage

Outside conventional archival, DNA and molecular storage represent genuinely different approaches. Synthetic Biology companies are actively offering DNA archival services, encoding data in synthetic DNA sequences for storage in passive conditions.

DNA storage offers extraordinary theoretical density and proven durability (DNA survives millennia in fossils). The challenges are read-write speeds and cost. Current DNA storage costs thousands of dollars per gigabyte, far exceeding optical glass estimates.

But the trajectory is improving rapidly. DNA storage might eventually dominate ultra-long-term archival despite current impracticality. That timeline is probably 10-20+ years away.

Practical Implementation: If You Were Deploying This Today

Lab and Research Institutions

Research organizations with massive genomic, astronomical, or simulation datasets should keep close watch on optical glass development. When 500GB proof-of-concept arrives in 2026, institutions should evaluate it seriously for long-term data preservation.

A pilot project archiving 10-100TB would be reasonable risk. The investment is modest compared to data center electricity costs, and success would provide valuable real-world performance data for future decisions.

Enterprise Backup Strategy

Large enterprises shouldn't bet their primary archival on optical glass yet. But incorporating optical glass into a redundant archival strategy makes sense. Write critical data to both tape and optical glass (once it's commercially available). The dual copies increase confidence that at least one medium survives any foreseeable catastrophe.

The cost premium of optical glass is acceptable for truly critical data where centuries of preservation adds genuine value.

Government and Institutional Records

Government agencies and cultural institutions with permanent data preservation mandates should begin strategic discussions about optical glass storage. The 2026-2030 timeline aligns with typical government procurement planning cycles.

By the time optical glass reaches commercialization, these institutions should have clear procurement strategies in place to adopt it quickly.

Critical Assessment: Realistic Probabilities of Success

What Success Actually Means

Success for optical glass storage doesn't require dominating the entire archival market. It requires becoming a viable option for organizations where the use case—long-term preservation with minimal environmental impact—justifies the cost premium over alternatives.

That's a narrower definition than the most optimistic marketing suggests, but it's genuinely achievable.

Probability Assessment

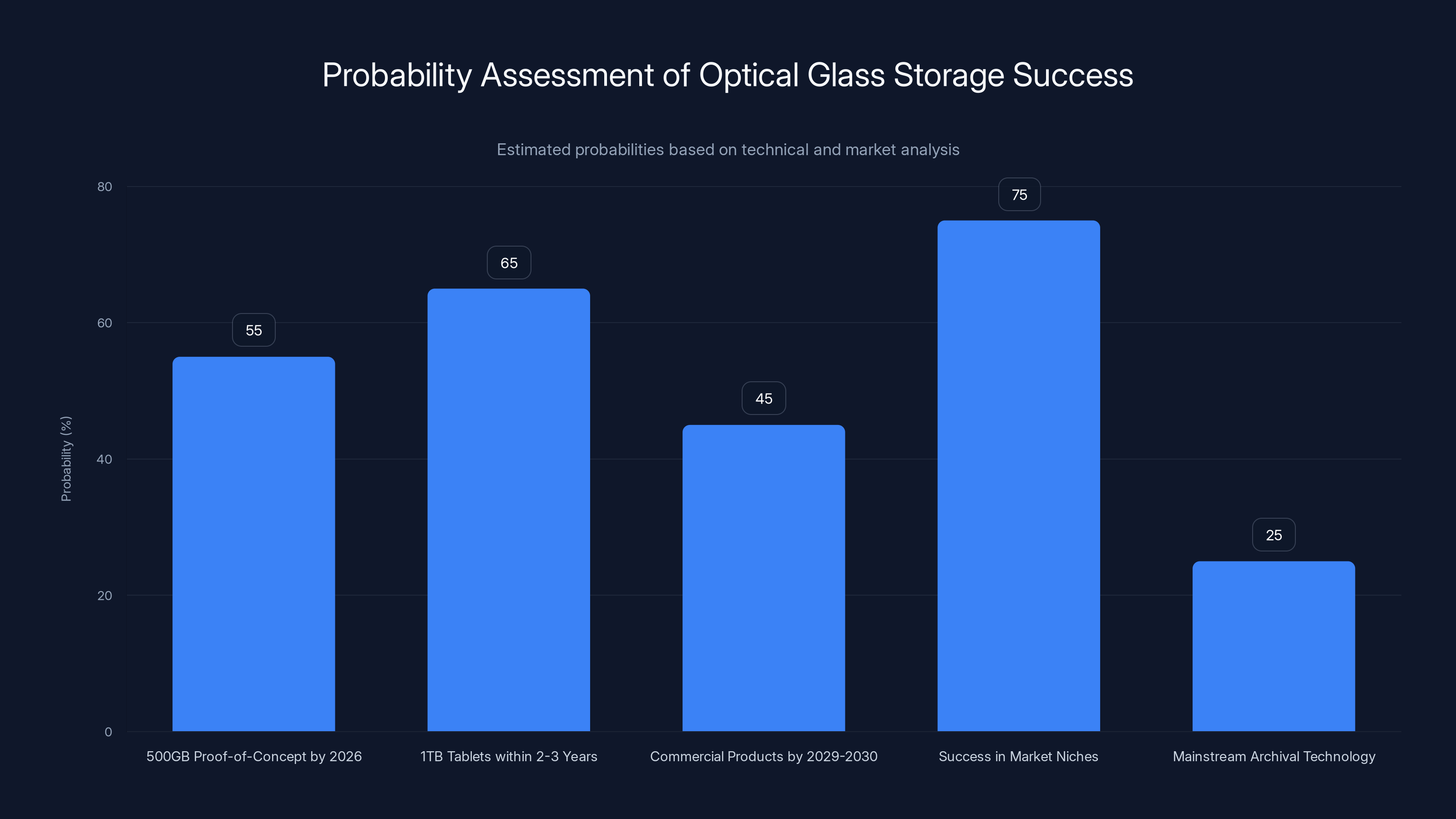

Based on technical fundamentals, research progress, and market dynamics, here's my realistic assessment:

50-60% probability that 500GB proof-of-concept ships in 2026 or shortly after. Delays in prototype stage are common, and the timeline is just announced, not formally committed.

60-70% probability that if 500GB succeeds, 1TB tablets follow within 2-3 years. The jump from 500GB to 1TB is straightforward engineering, not physics breakthroughs.

40-50% probability that commercial products become available to customers by 2029-2030. Manufacturing partnerships are the constraint. Optical storage has a historical pattern of taking 5-10+ years from proof-of-concept to commercial availability.

70-80% probability that if commercial products exist, they succeed in finding market niches (research institutions, government data preservation, enterprise compliance archival). There's genuine demand in those segments.

20-30% probability that optical glass storage becomes a mainstream archival technology competing directly with tape on cost metrics. Competing technologies are improving too, and optical glass starts with cost disadvantages.

Overall assessment: Optical glass storage very likely becomes real. It has 50/50 odds of achieving practical commercialization in the 2028-2032 timeframe. It has 70%+ odds of finding profitable niches, but lower odds of mainstream adoption.

That's genuinely positive. Many emerging technologies have worse odds. But it's also realistic about the risks and challenges ahead.

Takeaways for Different Audiences

For Technology Leaders and CIOs

Optical glass storage is worth monitoring but not betting your archival strategy on yet. Request briefings from your storage vendors on their roadmaps for optical archival. Start internal discussions about strategic use cases where century-scale durability has genuine value.

When 2026 arrives and the proof-of-concept ships, evaluate it seriously but skeptically. Ask hard questions about manufacturing scalability, real-world read performance, and cost competitiveness. Don't let the elegance of the physics distract you from practical business metrics.

For Researchers and Scientists

If your institution is archiving data that must survive indefinitely, optical glass storage should be on your roadmap. Participate in early evaluation projects if the opportunity arises. Contribute feedback about your actual data preservation requirements to help manufacturers understand the market.

The longevity claims—if validated—make optical glass superior to tape for data that truly needs to survive centuries. That includes genomic databases, climate datasets, and other scientific records.

For Storage Hardware Manufacturers

The competitive threat from optical glass is real, but not immediate. Over the next 5-10 years, tape and hard drive improvements remain more important than optical glass development. But manufacturers should develop optical storage expertise now, before market demand materializes.

Partners willing to invest in manufacturing partnerships with optical glass research teams position themselves to dominate that market segment when it emerges.

For Data Center Operators

Your strategy shouldn't change based on optical glass today. But long-term energy reduction is a genuine business incentive. Passive archival systems reduce electricity costs by enormous amounts compared to powered storage.

When optical glass reaches practical availability, even if it costs more per gigabyte than tape, the total cost of ownership might favor it for truly long-term archival. Model that scenario in your 10-year financial planning.

Conclusion: The Glass Half-Full Case for Optical Archival

Optical glass storage represents something genuinely new in an industry dominated by incremental improvements. The physics is sound. The research trajectory is sensible. The use cases are real and valuable.

But emerging technologies have a universal challenge: bridging from "this works in the lab" to "this works at scale, reliably, and economically." That bridge is short in some cases (a few years) and impossibly long in others (never completed).

Optical glass storage's bridge is probably 5-10 years long. Achievable, but not guaranteed. Speed of progress depends on research funding, manufacturing partnerships, competing technology progress, and sometimes just luck.

What makes optical glass genuinely interesting compared to other emerging storage technologies is the simplicity of the fundamental approach. You're not requiring quantum states or exotic conditions. You're manipulating light and material properties in ways that have been understood for decades.

That simplicity suggests the technology will ultimately work. The question is whether it works in time to be commercially relevant before tape and hard drives improve enough to make it unnecessary.

The 500GB proof-of-concept in 2026 is the crucial test. If that succeeds, expect serious momentum toward commercialization. If that slips significantly, the technology's timeline extends and competitive pressures increase.

For organizations whose data preservation needs extend decades or centuries, optical glass storage is worth tracking carefully. The technology might not transform all archival storage, but it will almost certainly transform some of it.

That's a success worth paying attention to.

FAQ

What is optical glass storage and how is it different from regular hard drives or SSDs?

Optical glass storage encodes data directly into the atomic structure of glass using photoluminescence and spectral hole burning. Unlike hard drives that use moving mechanical parts and spinning platters, or SSDs that use electrical charges, optical glass storage is completely passive once data is written. No moving parts, no electrical charge degradation, no mechanical failure modes. The data persists by manipulating the light-emission properties of specially doped glass using narrow-bandwidth lasers.

How does spectral hole burning actually encode data in glass?

Spectral hole burning works by using narrow-wavelength lasers to selectively alter nanoscale imperfections in the crystal lattice of a phosphor-doped glass. These alterations change how the material absorbs and emits light at specific wavelengths. During writing, the laser modifies these defect sites. During reading, a different laser scans the same regions and detects whether photoluminescence is emitted or suppressed, reconstructing the original binary information. The data remains stable indefinitely because it's encoded in the material's fundamental atomic structure.

What are the actual advantages of optical glass storage over magnetic tape for long-term archival?

Optical glass storage eliminates several problems with magnetic tape: no periodic refresh cycles needed (tape gradually degrades and must be migrated to new media every 10-20 years), immunity to electromagnetic interference and magnetic field disruption, no format obsolescence concerns (optical reading will always work), and dramatically lower energy costs for long-term preservation (tape requires ongoing climate control in data centers). For data that truly needs to survive 50+ years, optical glass potentially costs less total over the archival lifetime despite higher initial per-gigabyte cost.

Why is the 2026 500GB proof-of-concept milestone so important?

The 500GB tablet represents the first demonstration that spectral hole burning works at meaningful scale outside a laboratory environment. A proof-of-concept proves the technology actually works in practice, not just in theory. It gives manufacturers and investors confidence to invest in manufacturing partnerships, opens doors for testing and validation by independent parties, and provides a concrete achievement that validates the research trajectory. Without hitting this milestone, the technology remains theoretical regardless of how sound the physics.

What are the main unsolved technical challenges with optical glass storage?

Three major unknowns remain: read and write speeds have never been publicly specified (suggesting they're slower than competing technologies), durability under repeated access cycles hasn't been tested at scale (theory suggests it's excellent, but real-world proof is missing), and manufacturing consistency for millions of units at competitive cost is completely unproven. Additionally, multi-bit encoding through light intensity variations looks good mathematically but faces noise and signal-discrimination challenges that haven't been solved in real hardware at scale.

How does the cost compare to magnetic tape and hard drives for archival?

Estimates suggest optical glass at roughly

When will optical glass storage actually be available for purchase?

Commercial availability probably won't happen before 2029-2031 at the earliest, assuming manufacturing partnerships are secured promptly after the 2026 proof-of-concept. A 2026 500GB success would likely lead to 1TB tablets by 2027-2028, followed by multi-terabyte systems and manufacturing scale-up. Even with successful research progression, manufacturing partnerships and standardization discussions could delay availability another 2-3 years beyond that optimistic timeline.

Why do some people compare optical glass to Project Silica?

Both technologies use optical approaches to encode data in glass for ultra-long-term archival. However, Project Silica uses femtosecond lasers to create three-dimensional physical structures within fused silica, while optical glass storage with spectral hole burning uses narrow-bandwidth lasers to manipulate electronic states without physical changes. Project Silica has the advantage of proven fused silica durability, while optical glass potentially offers faster writes and lower equipment cost. They're different solutions to the same problem.

Could optical glass storage fail to commercialize like other emerging storage technologies have?

Absolutely. Emerging storage technologies frequently fail to reach commercialization despite sound physics. Examples include holographic storage, which worked technically but never achieved manufacturing scale at competitive cost. Optical glass faces similar risks: manufacturing complexity, capital investment requirements, competing technology improvements, and market adoption inertia could all stall commercialization. The difference is that optical glass storage has realistic use cases (government data preservation, research archival) where the premium cost is justifiable, unlike some competing approaches.

What should organizations do right now if they need long-term data preservation?

Stick with proven technologies: magnetic tape for cost-effective archival where you can tolerate format refresh cycles, or redundant cloud archival for data requiring faster recovery. Begin monitoring optical glass storage development through 2026-2027. Develop internal discussions about archival requirements and scenarios where 1000+ year durability has genuine value. When commercial optical glass products become available, evaluate them seriously for data that truly needs century-scale preservation, but don't migrate existing archives prematurely without proven performance data.

Key Takeaways

- 500GB glass tablets represent the first practical proof-of-concept for optical storage, scheduled for 2026 from University of South Australia research team

- Spectral hole burning and photoluminescence enable data encoding at atomic scale without physical damage to the medium, promising centuries of durability

- Room-temperature operation with modest power requirements offers dramatic advantages over competing femtosecond laser approaches in cost and complexity

- Manufacturing scalability, read-write speeds, and real-world multi-bit encoding durability remain completely unproven despite sound underlying physics

- Total cost of ownership could favor optical glass over tape for truly long-term archival (50+ years) despite higher initial per-gigabyte cost

![Optical Glass Storage: 500GB Tablets Reshape Data Archival [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/optical-glass-storage-500gb-tablets-reshape-data-archival-20/image-1-1766974458146.jpg)