Understanding the $134 Billion Lawsuit Against Open AI and Microsoft

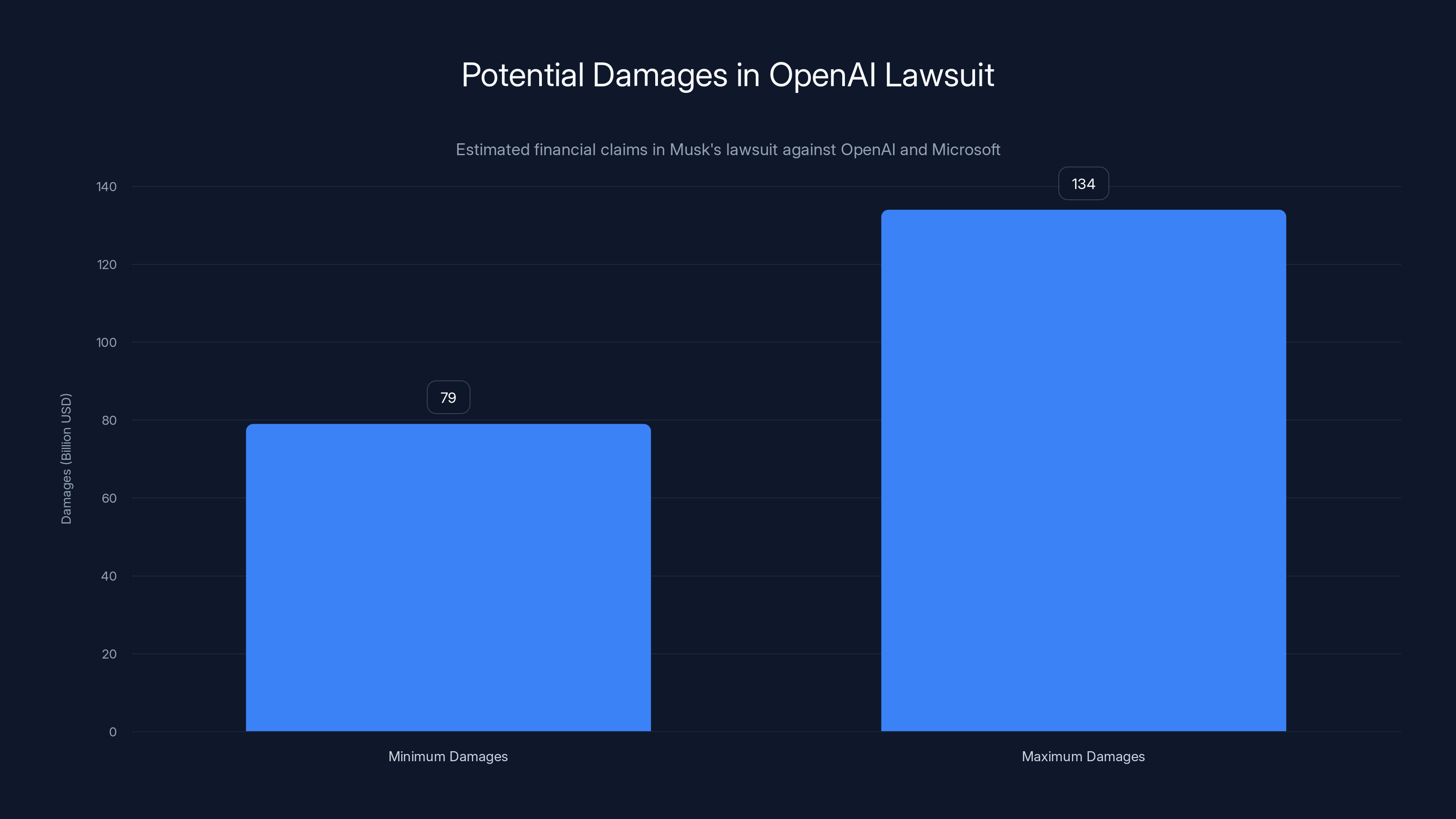

The legal confrontation between Elon Musk and Open AI represents one of the most significant technology litigation disputes of the decade, involving staggering financial claims and fundamental questions about intellectual property ownership, company valuation, and the path that groundbreaking AI companies should follow. In January 2026, Musk formally submitted his remedies request in his ongoing lawsuit against Open AI and its largest financial backer, Microsoft, seeking damages between

The core of this legal dispute centers on a fundamental accusation: that Open AI has abandoned its founding nonprofit mission and transformed into a for-profit enterprise that prioritizes corporate interests over its original charitable objectives. Musk, who co-founded Open AI in 2015 alongside Sam Altman and others, positions himself as a wronged early investor and visionary who contributed not just capital but also his reputation, leadership experience, and network of influential contacts to help establish what would become one of the most valuable AI organizations in the world. According to Musk's legal team, he deserves substantial compensation for these contributions, particularly given that he departed from Open AI's leadership in 2018 before the company achieved its current prominence. The lawsuit touches on broader themes of startup equity, founder recognition, and the degree to which early investors and advisors should benefit from a company's eventual success.

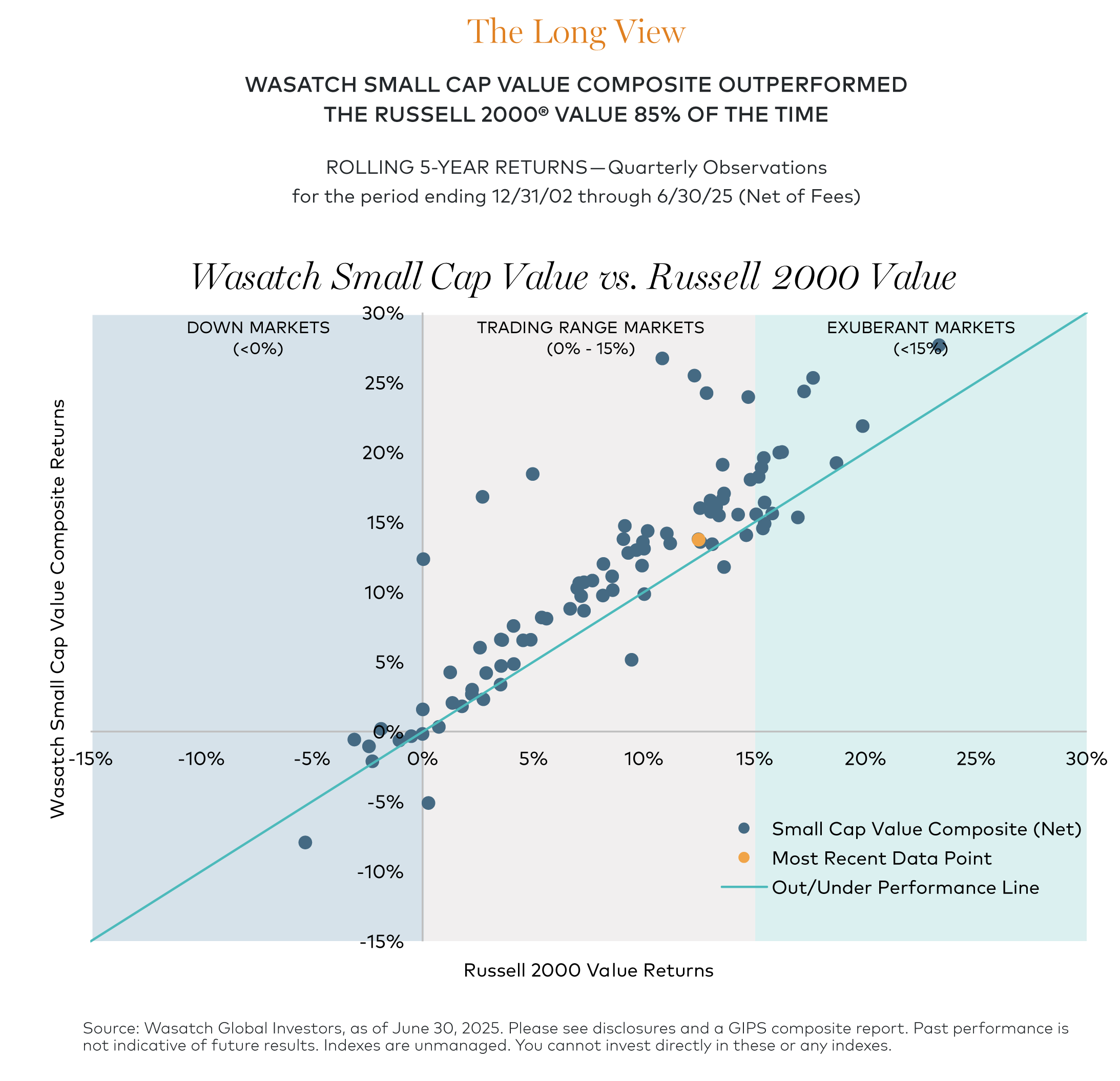

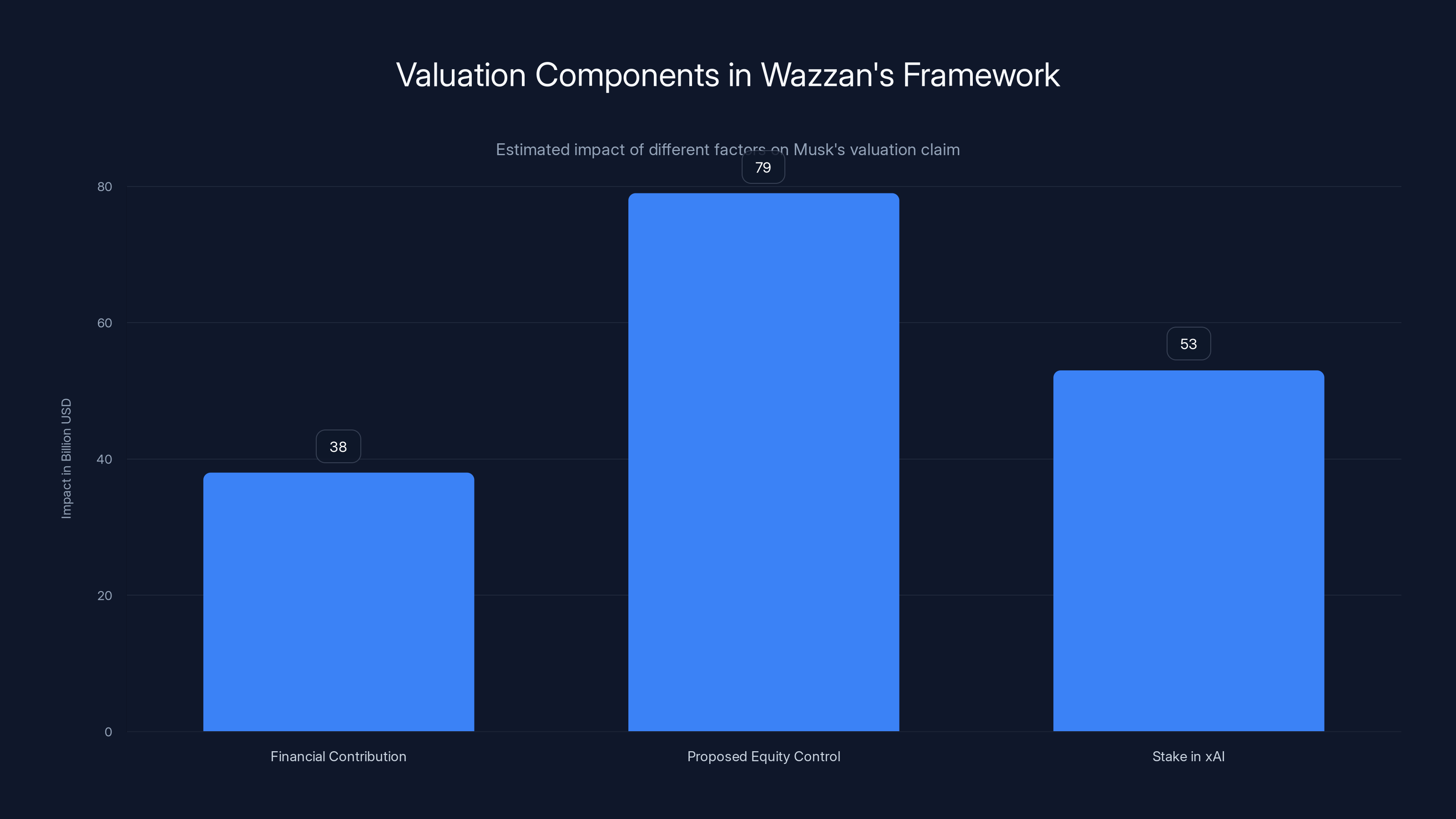

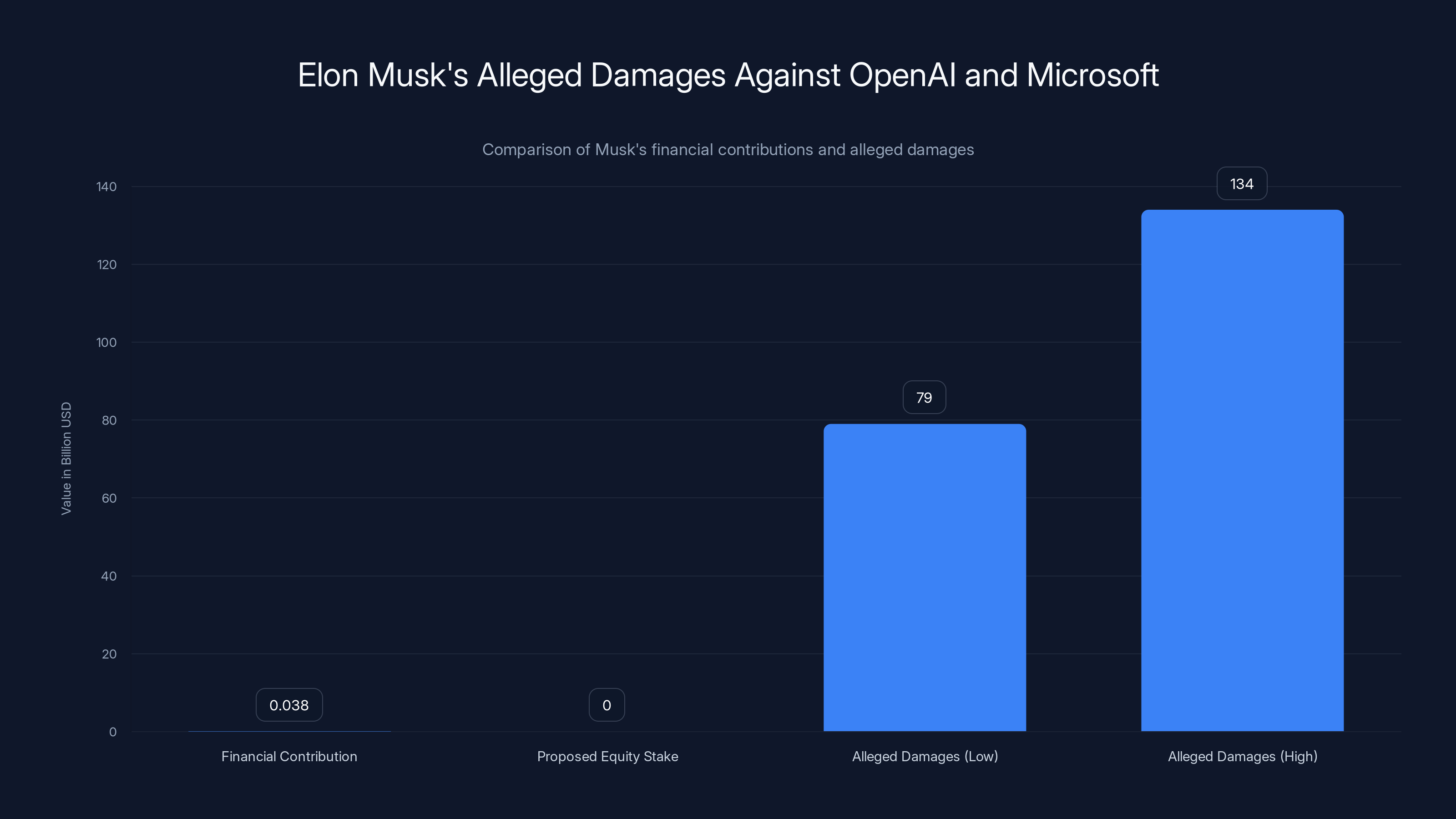

What makes this case particularly fascinating from a legal and technical perspective is the methodology used to arrive at these unprecedented damage figures. Wazzan's analysis relied on four primary factors: Musk's total financial contributions before he left Open AI in 2018 (approximately $38 million, representing roughly 60 percent of the nonprofit's seed funding), Musk's proposed equity stake in Open AI from a 2017 negotiation that would have given him 51.2 percent control of a new for-profit entity, Musk's current equity stake in x AI (estimated at 53 percent based on public reporting), and Musk's nonmonetary contributions including employee recruitment, business introductions, and reputation lending. This multi-factor approach attempted to create a comprehensive picture of Musk's value to Open AI, translating diverse forms of contribution into a unified monetary figure.

However, Open AI and Microsoft have aggressively challenged this methodology, arguing that Wazzan's calculations are fundamentally flawed, based on hypothetical scenarios that never occurred, and deliberately constructed to inflate damages to please their client. The tech giants filed a motion to exclude Wazzan's expert testimony, characterizing his work as "made up" mathematics based on calculations he had never used before and appeared to have "conjured" specifically to satisfy Musk's financial demands. This legal disagreement between sophisticated parties—involving a specialized expert witness and rigorous scrutiny of valuation methodologies—illuminates broader questions about how courts should evaluate complex financial claims in technology disputes and what standards should apply when determining whether an expert's methodology is reliable enough to present to a jury.

The Controversy Over Valuation Methodology

Wazzan's Four-Factor Analysis Framework

C. Paul Wazzan approached the challenge of valuing Musk's contributions to Open AI by constructing a comprehensive framework that attempted to capture multiple dimensions of value creation. This methodology represented what Wazzan himself described as a "pretty unique" fact pattern that couldn't be found in standard financial textbooks. The first component—Musk's financial contributions of

The second factor—Musk's proposed 2017 bid for 51.2 percent equity control of a proposed for-profit entity—presents the first major source of controversy. This negotiation never reached fruition; Musk and Open AI's leadership failed to agree on valuation terms and ownership structure, leading Musk to ultimately depart from the organization. Wazzan's analysis, however, treated this failed negotiation as a baseline for calculating what Musk "should have" owned, essentially building damages calculations around a deal that never happened. This creates a conceptual problem: if no deal was struck, on what legal basis should Musk receive compensation equivalent to ownership that he never actually possessed? Open AI's legal team argues this represents a fundamental misunderstanding of contract law, which generally requires an actual agreement to exist before a party can claim breach of contract damages.

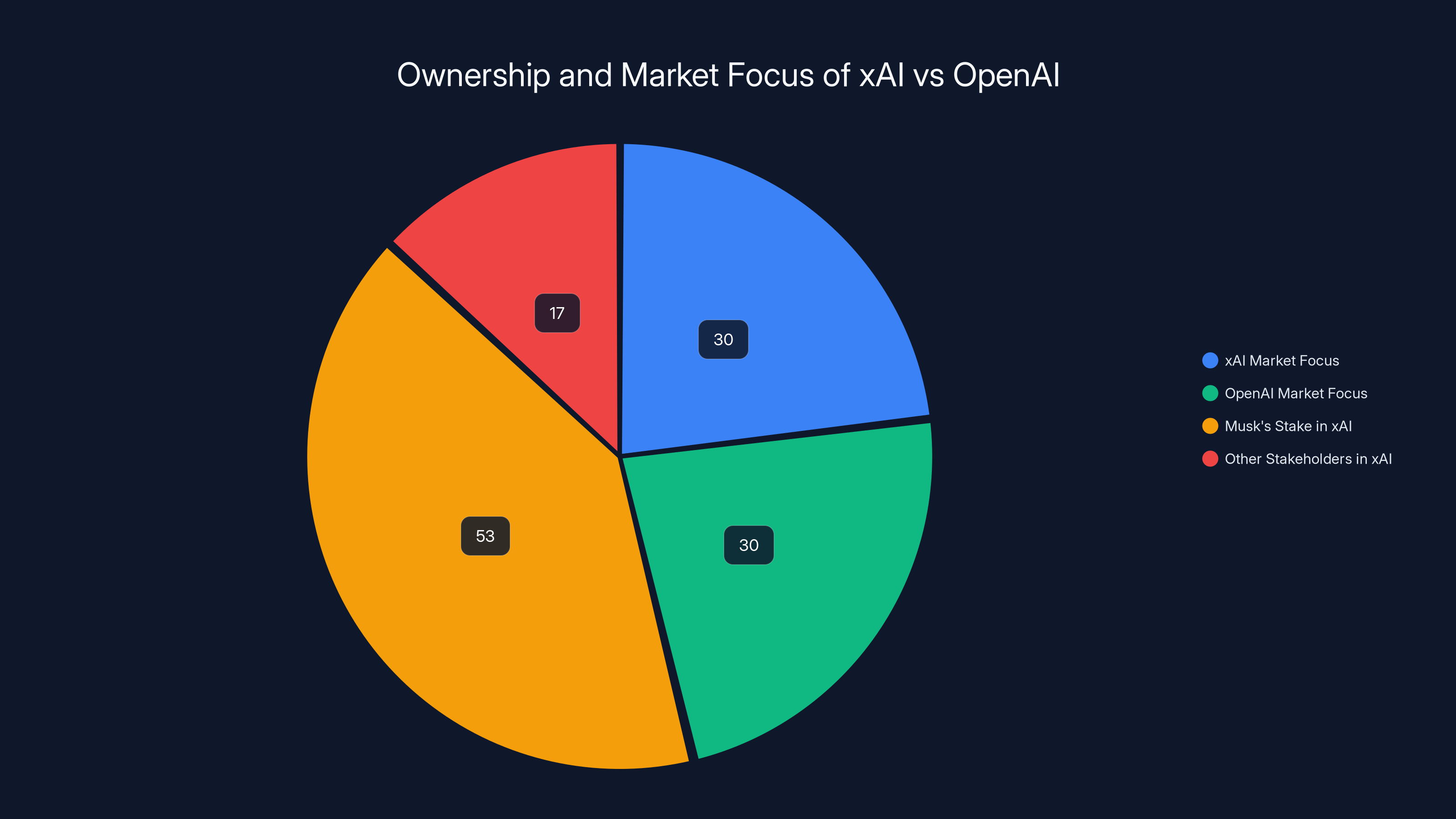

The third component—Musk's 53 percent stake in x AI—introduces even more contentious reasoning. Wazzan referenced Musk's ownership percentage in x AI, a completely separate company in which Musk was actively involved as founder and primary investor. Open AI and Microsoft questioned why x AI's valuation and ownership structure should have any bearing on damages owed by Open AI. The two companies operate in different markets, have different revenue models, and serve different purposes. Moreover, Wazzan apparently never accessed x AI's actual financial data; instead, he relied solely on public reporting about the company's estimated valuation. This raises questions about whether using x AI ownership as a comparison point constitutes proper methodology or whether it simply allows Wazzan to incorporate another large number into his calculation.

The fourth factor—Musk's nonmonetary contributions—encompasses recruitment of key talent, introduction of business contacts, knowledge transfer about startup operations, and lending of his personal prestige and reputation to the venture. These intangible contributions certainly have value, as any investor or entrepreneur would acknowledge that Musk's involvement in a venture carries weight beyond mere capital deployment. However, translating intangible reputation value into a specific monetary figure requires making assumptions that are inherently subjective. How much is Musk's introduction of a key engineer worth? What is the monetary equivalent of his reputation? These questions lack objective answers, making them particularly vulnerable to criticism when the resulting damage figures are extraordinarily large.

The Problem of Hypothetical Scenarios

One of the most significant criticisms of Wazzan's analysis centers on his reliance on hypothetical scenarios that never occurred in reality. The damages calculation fundamentally depends on assuming that the 51.2 percent equity stake Musk proposed in 2017 would have been granted by Open AI, creating ownership that could then appreciate to generate the claimed damages. Yet this scenario contradicts the documented historical record: Musk and Open AI's leadership disagreed on valuation, and no deal was reached. When Musk subsequently left Open AI's leadership structure, he apparently did not pursue forced arbitration or litigation to secure the ownership stake he allegedly deserved—a decision that Open AI suggests undermines his current damage claims.

Open AI's legal filing articulated this problem clearly: "It's unclear why Musk would be owed damages based on a deal that was never struck." In contract law and damages theory, compensation typically flows from breaches of agreements that actually existed. If no agreement existed regarding Musk's equity stake, then there is no contractual basis for claiming damages related to that stake's appreciation. Wazzan's methodology essentially asks the court to calculate damages by imagining a reality that diverged from actual history at a crucial juncture—a problematic foundation for financial compensation.

The Double-Counting Problem with Microsoft's Contributions

Another fundamental issue with Wazzan's calculations involves how he treated Microsoft's financial contributions and the flow of value between Microsoft's for-profit investment and Open AI's nonprofit structure. According to Open AI's and Microsoft's legal response, Wazzan made an unjustified assumption: that "some portion of Microsoft's stake in the Open AI for-profit entity should flow back to the Open AI nonprofit" and that this portion must equal "the nonprofit's stake in the for-profit entity."

This reasoning creates a mathematical problem through double-counting. Microsoft negotiated specific terms for its investment in Open AI's for-profit affiliate, investing billions of dollars in years following Musk's departure. These investments represented Microsoft's decision to fund the for-profit entity at particular valuation levels and ownership percentages. Wazzan's methodology then attempted to reallocate portions of Microsoft's negotiated returns back to the nonprofit, artificially inflating the nonprofit's value and, consequently, inflating estimates of Musk's damages. Microsoft's legal team emphasized that Wazzan provided "no rationale—contractual, governance, economic, or otherwise—for reallocating any portion of Microsoft's negotiated interest to the nonprofit." Without such a rationale, the reallocation appears arbitrary and undermines the methodological validity of the entire calculation.

xAI's market focus and Musk's 53% stake highlight its distinct positioning compared to OpenAI. Estimated data.

Dismissing All Other Contributions as "Zero Percent"

The Exclusion of Researcher and Developer Contributions

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Wazzan's analysis is what it explicitly excludes: the contributions of the scientists, researchers, engineers, and developers who actually created Open AI's products, particularly Chat GPT. According to Open AI's legal filing, Wazzan's methodology found that these individuals and groups contributed "zero percent of the nonprofit's current value." This conclusion represents a staggering oversight that Open AI has seized upon as demonstrating fundamental flaws in Wazzan's reasoning.

When asked during testimony whether he needed to account for other contributors' efforts, Wazzan testified: "I don't need to know all the other people." This response encapsulates the core problem with his methodology—it wasn't designed to comprehensively value all contributors to Open AI's success but rather to isolate Musk's contributions and inflate them to support a predetermined damage figure. The people who developed Chat GPT's transformer architecture, trained the underlying language models using billions of computing cycles, debugged and optimized the system for real-world deployment, and continuously improved the model through empirical experimentation undoubtedly contributed substantial value to Open AI's current market position.

Open AI's co-founders Sam Altman, Greg Brockman, and others who remained with the organization through its transition from nonprofit to for-profit structure and its scaling to global prominence also made substantial contributions. Early employees who took equity stakes and worked through the precarious early years when AI research outcomes were uncertain accepted enormous risk in exchange for the potential of future upside—risk that materialized into substantial returns as Open AI achieved success. Reducing all of these contributions to "zero percent" while attributing 50 to 75 percent of current value to Musk, who departed the organization before its greatest achievements, inverts the historical record of contribution.

The Question of Why Musk Left Open AI

Another crucial element of this controversy involves understanding why Musk departed from Open AI's leadership structure in the first place. According to Open AI's characterization, the parting occurred because "leadership did not agree on how to value Musk's contributions to the nonprofit." This statement suggests that Musk had proposed a specific valuation or equity arrangement—perhaps the 51.2 percent stake in a for-profit entity that he would later claim he deserved—and when Open AI's other leaders rejected this proposal or offered different terms, Musk chose to exit.

This framing creates a narrative problem for Musk's current damages claim. If Musk voluntarily departed when negotiations over his equity stake or compensation reached an impasse, what is the legal basis for now suing for damages based on a compensation arrangement that he proposed but that others rejected? In typical employment or partnership contexts, when one party proposes compensation terms that the other party declines to accept, the proposing party can choose to accept less favorable terms, propose revised terms, continue negotiating, or depart the relationship. Departing generally does not entitle the party to later recover damages based on the compensation terms they proposed but that others refused to grant.

Wazzan's framework attempts to justify Musk's valuation claim by combining his financial contribution, proposed equity control, and stake in xAI. Estimated data.

The Temporal and Contextual Issues with x AI Comparisons

Using x AI Valuations as a Baseline

Wazzan's incorporation of Musk's 53 percent stake in x AI into the damages calculation represents a particularly puzzling choice from a methodological perspective. x AI, founded in 2023, is a completely separate company operating in the generative AI space but with a distinct market focus, business model, and investor base compared to Open AI. The two companies do not directly compete in identical market segments; Open AI focuses heavily on conversational AI and large language models with broad consumer applications, while x AI has pursued a different positioning within the AI landscape.

Why should x AI's current valuation have any bearing on what Musk's contributions to Open AI should be worth? According to Open AI's legal analysis, there is no logical connection. Each company is valued based on its own market prospects, technological capabilities, revenue potential, and competitive positioning. The fact that Musk owns a majority stake in x AI tells us something about x AI's current valuation relative to its capital requirements, but it tells us nothing about how much value Musk created at Open AI eight years earlier.

Moreover, the specific numbers Wazzan used are based on public reporting and estimates, not on x AI's actual financial statements or internal valuations. Public estimates of private company valuations often vary significantly from actual internal assessments, venture capital term sheets, and secondary market prices. Building damage calculations in a major lawsuit on estimated valuations from news reports, rather than on verified financial documentation, raises obvious concerns about reliability.

The Absence of Independent Analysis

Wazzan's testimony indicated that he never accessed x AI's actual financial data to evaluate its true valuation or the factors driving it. This represents a significant methodological limitation. A proper comparative analysis of Musk's contributions across x AI and Open AI would require understanding the specific circumstances of each company: the market conditions at the time of founding, the competitive landscape, the specific technological breakthroughs achieved, the investor base and their requirements, and dozens of other factors. Without access to x AI's actual financials and detailed understanding of the company's value drivers, Wazzan was essentially using a single number (Musk's ownership stake in a company of estimated value $X) to draw inferences about what Musk's contributions to a different company should be worth.

This approach falls short of rigorous economic analysis. It's comparable to saying: "Investor A owns 53 percent of Company X valued at

The Legal Framework for Damages Claims

Contractual vs. Quasi-Contractual Damages

Understanding the legal framework surrounding Musk's damages claim requires distinguishing between different categories of damages recognized in contract and business law. Contractual damages compensate parties for breaches of agreements that explicitly exist in writing or can be inferred from the parties' conduct and communications. These damages are typically measured by calculating what the breaching party promised to deliver and what the non-breaching party lost as a result of non-delivery.

In contrast, quasi-contractual damages (sometimes called restitution) compensate parties when one party has unjustly enriched another without an underlying contract obligating compensation. These claims are generally available when one party has conferred benefits on another that the benefiting party would have had to pay for if a proper contract had existed. However, quasi-contractual claims typically involve relatively straightforward value transfers: if a contractor builds improvements to someone's property without authorization, the property owner has been enriched and may owe restitution for the value of those improvements.

Musk's claims against Open AI apparently rest on the theory that he conferred substantial benefits on Open AI that the organization was unjustly enriched to retain, and that he deserves compensation for those benefits. However, this theory faces the complication that Musk contributed to Open AI as a co-founder and early investor, presumably with the understanding that value creation would be reflected through equity ownership rather than through direct compensation payments. The nature of early-stage startup participation involves accepting illiquidity and long-term value appreciation prospects rather than immediate cash compensation.

The Role of Equity Ownership and Negotiation History

Another framework for understanding damages involves the history of equity negotiations between Musk and Open AI. When Musk proposed 51.2 percent control of a proposed for-profit entity in 2017, he was initiating a negotiation about how his contributions would be valued in equity terms. Open AI's failure to grant him this stake might suggest either that Open AI valued his contributions differently (perhaps lower than he valued them himself) or that Open AI's other founders and investors were unwilling to dilute their ownership to the extent Musk proposed.

When parties to a negotiation cannot agree on terms, the typical legal consequence is that the proposed deal does not proceed. It is not that the rejecting party owes damages to the proposing party based on what would have happened had they agreed. This principle is fundamental to contract law: absent an agreement, there is no contractual obligation and no basis for damages based on a hypothetical agreed-upon arrangement.

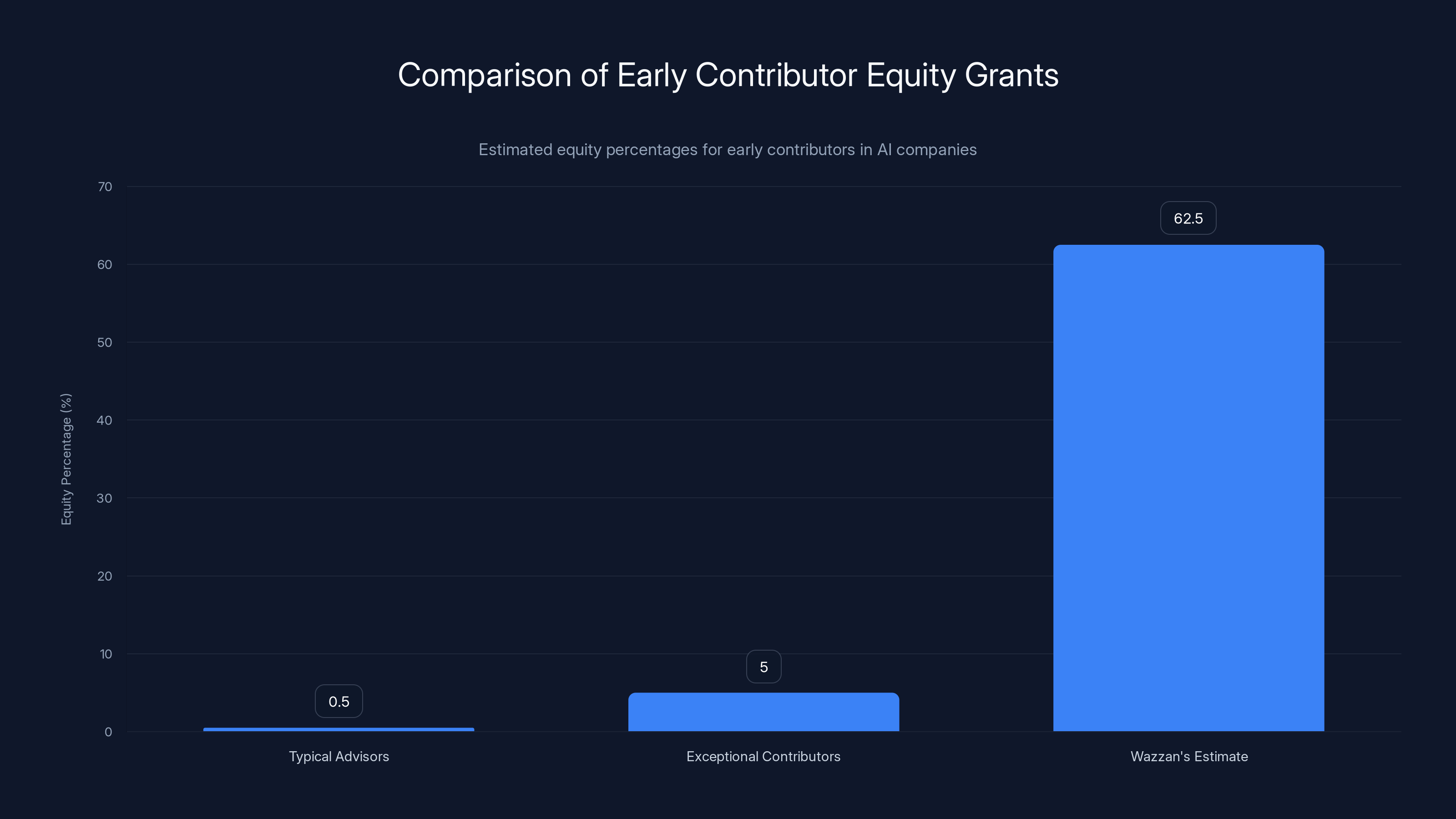

Estimated data suggests typical early advisors receive 0.1% to 1% equity, exceptional contributors might receive up to 5%, while Wazzan's estimate for Musk is significantly higher at 50-75%.

Open AI's and Microsoft's Legal Counterclaims

The Harassment Campaign Allegation

Open AI and Microsoft have characterized Musk's lawsuit not merely as a legitimate damages claim but as part of a broader pattern of harassment designed to interfere with Open AI's competitive position and provide advantage to x AI. According to Open AI's public statements, "Musk's lawsuit continues to be baseless and a part of his ongoing pattern of harassment, and we look forward to demonstrating this at trial." The company further characterized the damage demand as "unserious" and suggested it was "aimed solely at furthering this harassment campaign."

This characterization introduces strategic and reputational dimensions beyond the narrow technical question of whether Wazzan's methodology is reliable. If Open AI and Microsoft can persuade the court that Musk's true motivation is to harass a competitor and slow its growth rather than to achieve legitimate compensation for contributions, this framing could influence how the court evaluates Wazzan's expert testimony and the reasonableness of the damage figures.

The Emphasis on Post-Departure Contributions

Open AI's legal response emphasizes that the most significant value creation at Open AI occurred after Musk's departure from the organization's leadership. Microsoft's investments in Open AI's for-profit affiliate, made years after Musk had left, totaled billions of dollars and directly funded the development and scaling of AI systems that generate Open AI's current market value. The engineers, researchers, and product teams who remained at Open AI through its transition to for-profit status and its achievement of global prominence contributed substantially to the organization's success. By departing in 2018, Musk positioned himself outside the organization during its period of greatest achievement.

This temporal dimension is crucial to Open AI's defense. If most of Open AI's current value was created after Musk's departure, then attributing 50 to 75 percent of current value to Musk's pre-departure contributions becomes mathematically implausible. Even if Musk's early contributions were crucial to establishing Open AI's foundation, they cannot account for the vast majority of value creation that occurred years later when the organization was scaling to serve millions of users and becoming a critical infrastructure provider for AI development globally.

Expert Witness Credibility and Methodological Reliability

Wazzan's Background and Previous Work

According to Musk's legal filing, C. Paul Wazzan is "a financial economist with decades of professional and academic experience who has managed his own successful venture capital firm that provided seed-level funding to technology startups." These credentials suggest someone with relevant experience in valuing early-stage technology companies and understanding how founder contributions translate into equity value.

However, Open AI's legal response notes that Wazzan had never previously been hired by any of Musk's companies before this assignment. Instead, Musk's legal team contacted Wazzan's consulting firm, BRG, approximately three months before Wazzan submitted his opinions. This relatively recent engagement raises questions about whether Wazzan was selected based on his methodology and approach or based on his willingness to produce a result favorable to Musk's damage claims. In legal proceedings, there is often tension between expert witnesses who are hired to provide their honest professional opinion and expert witnesses who are hired because their likely opinions align with their client's interests.

The Problem of Novel Methodologies

Wazzan's own testimony indicated that his calculations weren't something "you'd find in a textbook." While novelty in analysis is not inherently problematic—legal cases sometimes involve unprecedented situations requiring innovative analytical approaches—it does require careful scrutiny of whether the novel methodology is grounded in established principles or whether it is essentially custom-built to reach desired conclusions.

Open AI and Microsoft argue that Wazzan's approach falls into the latter category. They contend that he "cherry-picked convenient factors that correspond roughly to the size of the 'economic interest' Musk wants to claim, and declare that those factors support Musk's claim." This criticism suggests that rather than following a structured methodology and seeing where it leads, Wazzan might have started with a target damage figure (in the range of

The Unreliable Black Box Problem

Open AI and Microsoft's motion to exclude Wazzan's testimony characterizes his analysis as an "unreliable black box"—a calculation that cannot be independently tested, validated, or meaningfully scrutinized by opposing parties or the court. A true scientific or economic methodology should be transparent and replicable: another expert should be able to take the same inputs and follow the same methodology to arrive at the same results. If the methodology is so idiosyncratic and dependent on Wazzan's subjective judgments that no one else could replicate it, then it fails the basic test of expert reliability.

This concern becomes particularly acute when the calculation involves multiple steps, each incorporating subjective judgments: How much of Open AI's value derives from Musk's financial contribution versus his reputation versus his network versus his leadership teachings? What happens if you weight these factors differently? How sensitive is the final damage figure to changes in the underlying assumptions? If small changes in assumptions yield vastly different results, this indicates the calculation is unstable and dependent on subjective choices rather than objective relationships.

The lawsuit seeks damages between

The Broader Implications for Startup Equity and Founder Recognition

Founder Attribution in Complex Value Creation

This lawsuit raises profound questions about how to attribute value creation in complex organizational contexts where multiple parties contribute in diverse ways. In a modern technology startup, value creation typically results from the synergistic interaction of many factors: founder vision and leadership, investor capital and credibility, recruited talent and their expertise, organizational culture and decision-making processes, technological breakthroughs and their implementation, market timing and competitive positioning, and countless other elements.

When one party leaves the organization and later disputes how much credit they deserve for its subsequent success, courts must grapple with fundamentally uncertain counterfactual questions: What would have happened to Open AI if Musk had remained in a leadership capacity versus remaining as an investor? Would the organization have achieved the same technological breakthroughs? Would it have pursued the for-profit transition? Would it have attracted the same investor capital and talent? These questions lack definitive answers, making them poor foundations for damage awards of unprecedented magnitude.

Historical Parallels and Precedent

The technology industry has witnessed numerous disputes between founders and early investors regarding credit and compensation for company success. These disputes typically involve either: (1) enforcement of explicit equity agreements and vesting schedules that governed the parties' relationship, (2) claims that promised equity was not properly granted or documented, or (3) shareholder derivative suits on behalf of the company alleging that insiders breached fiduciary duties. Rarely do they result in damage awards of the magnitude Musk is seeking based on expert-derived valuations of contributions that were never the subject of explicit written agreements.

The most famous parallel might be the early history of personal computing, where figures like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and others made early contributions to organizations they later departed or were forced out of. Jobs' ouster from Apple and subsequent successful venture with Ne XT and acquisition by Apple is one such example. However, even in cases where founders were famously pushed out and later vindicated, the remedy typically involved either regaining control of the organization or negotiating compensation based on documented, explicit agreements rather than through litigation based on expert valuations of hypothetical contributions.

The Federal Judge's Role in Evaluating Expert Testimony

Daubert Standard and Expert Reliability

Federal courts use the Daubert standard to evaluate whether expert testimony is sufficiently reliable to be admitted as evidence in litigation. The standard requires courts to assess factors including: whether the methodology is testable and has been tested, whether the methodology has a known or potential error rate, whether the methodology has been subjected to peer review and publication, whether the methodology is generally accepted in the relevant professional community, and whether the expert's application of the methodology is sound.

Applied to Wazzan's testimony, the Daubert standard raises significant concerns. His methodology appears to be novel and not widely used or accepted in the financial economics community. The calculation seems to depend on subjective judgments without clearly defined criteria. The methodology apparently was not subjected to rigorous independent peer review before being submitted in litigation. And the application to Open AI appears to involve cherry-picking factors and assumptions to reach a predetermined result.

The Judge's Discretionary Authority

Federal judges have significant discretionary authority to exclude expert testimony that fails to meet the Daubert standard or that, even if technically admissible, would be more misleading than helpful to the jury. Open AI and Microsoft are asking the judge to exercise this authority and prevent Wazzan's testimony from being presented to a jury. A judge might reasonably conclude that presenting an expert's highly subjective valuation based on novel methodology and unsupported assumptions would confuse and mislead a jury rather than helpfully illuminating the disputed issues.

Alternatively, a judge might admit Wazzan's testimony but allow opposing parties to vigorously cross-examine him, present counter-expert testimony based on more rigorous methodologies, and argue to the jury that his analysis should be given little weight. The judge's decision on this procedural question will significantly influence the trajectory of the case.

Elon Musk's financial contribution to OpenAI was

Alternative Approaches to Valuing Early Contributor Compensation

Comparable Transaction Analysis

One more rigorous approach to valuing Musk's contributions would involve identifying comparable transactions in which early contributors to AI companies received compensation or equity grants, and using those transactions as benchmarks. If venture capital investors and management typically compensate early advisor-contributors at certain percentages of equity in comparable situations, that market data would provide objective grounding for a damages estimate.

However, this approach would likely yield much more modest figures than Wazzan's analysis. Early advisors typically receive fractional percentage equity grants (0.1 percent to 1 percent in many cases) rather than the 50 to 75 percent that Wazzan attributed to Musk. Even accounting for Musk's exceptional status as a serial entrepreneur and industry figure, market data would unlikely support such enormous percentages.

Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

Another legitimate approach would involve conducting a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis of Open AI's projected future cash flows and attributing a portion of that value to the specific contribution Musk made. This methodology requires estimates of future revenues, expenses, growth rates, and discount rates—all of which involve uncertainty but are based on market data and industry benchmarks. Such an analysis would likely yield more conservative estimates than Wazzan's approach and would be more transparent about the assumptions underlying the valuation.

Equity Market Pricing

If Open AI's equity were publicly traded, the market price of shares would provide objective evidence of the company's value. Even absent public trading, if recent secondary transactions have occurred at particular valuations, those prices reflect what actual informed investors believe the company is worth. Wazzan's methodology could be tested by comparing his valuation to these market prices and explaining any significant discrepancies.

The Question of Precedent and Jury Decision-Making

Predicting Jury Reactions to Extraordinary Damages Claims

The legal question of whether Wazzan's testimony is admissible is ultimately distinct from the factual question of whether a jury would find Musk's damages claim persuasive. Even if the judge allows Wazzan to testify, a jury might simply reject his conclusions as implausible. Juries have the power to disregard expert testimony they find unconvincing, no matter how qualified the expert.

Musk's claim for

The Role of Jury Instructions and Burden of Proof

The judge will also determine what jury instructions will be given regarding how to evaluate damages. If the judge instructs the jury that they must find Musk's damages claim supported by credible evidence, applying clear standards of valuation methodology, jurors might be quite skeptical of Wazzan's novel approach. Conversely, if the jury is given more permissive instructions allowing them to award any damages that seem reasonable given Musk's contributions, the standard is more subjective.

Musk bears the burden of proving his damages claim by a preponderance of the evidence (more likely than not in most civil litigation contexts). Meeting this burden with Wazzan's analysis requires the jury to accept assumptions and methodologies that Open AI and Microsoft have specifically challenged as unreliable and cherry-picked.

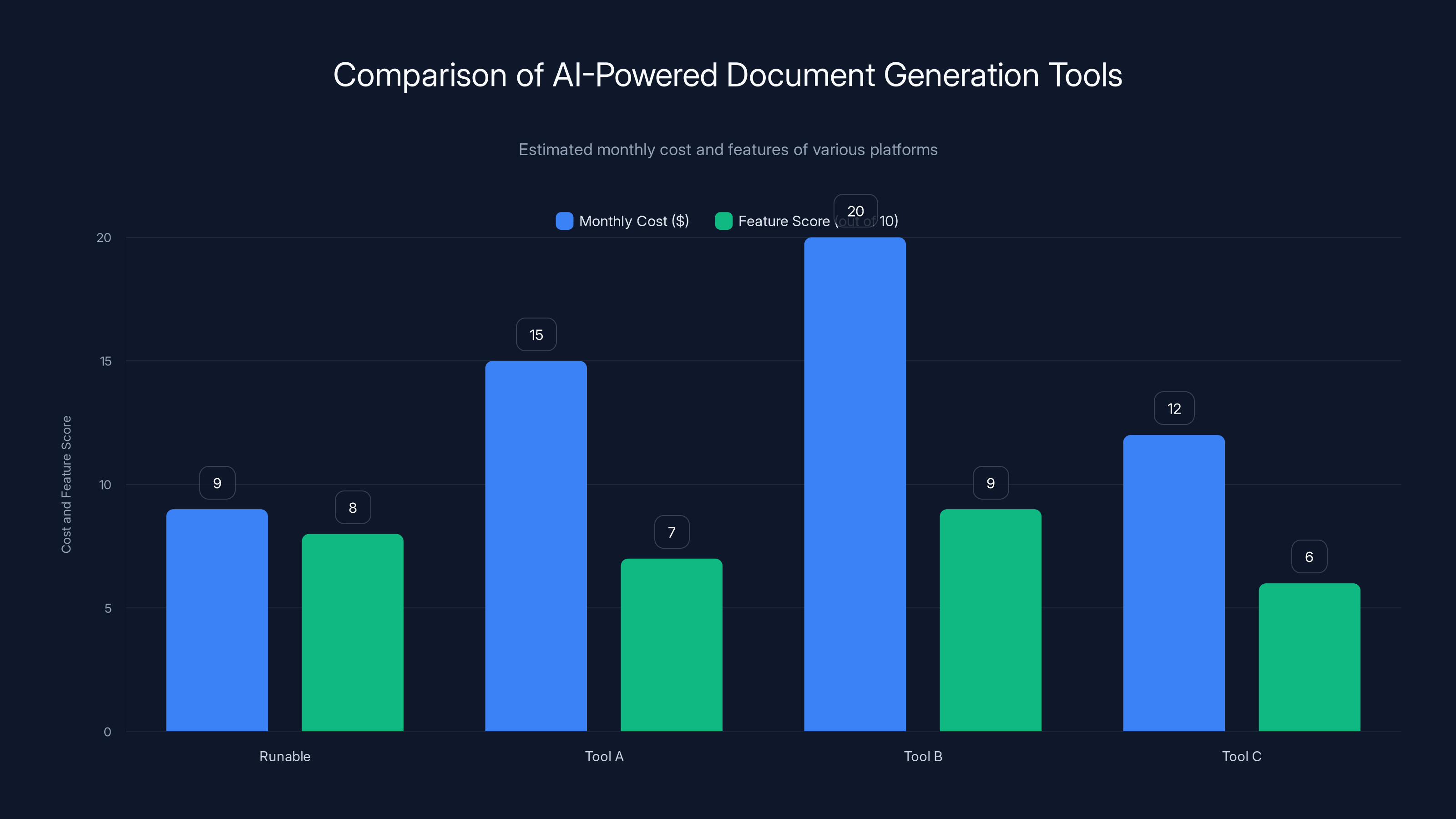

Runable offers a competitive monthly cost of $9 with a feature score of 8, making it a cost-effective option for AI-powered document generation. Estimated data.

Open AI's Nonprofit Mission and Governance Questions

The Nonprofit-to-For-Profit Transition

Underlying this damages dispute is Open AI's controversial transition from a nonprofit research organization to a hybrid structure with a for-profit subsidiary backed by Microsoft and other investors. Open AI was founded in 2015 as a nonprofit, with a stated mission to ensure artificial general intelligence benefits humanity. This mission was genuinely reflected in Open AI's early structure and governance, with no shareholders or profit-seeking investors.

Over time, as AI research became increasingly capital-intensive and private sector investment flowed into the field, Open AI's leadership determined that the nonprofit structure was inadequate to finance the kind of large-scale research and development required to remain competitive. This led to creation of the for-profit Open AI LP subsidiary, with the nonprofit Open AI Inc. retaining oversight through a board structure. Microsoft and other investors could then put capital into the for-profit entity while ostensibly supporting the nonprofit's mission.

Musk's lawsuit essentially argues that this transition violated Open AI's founding principles and represents a betrayal of the nonprofit mission. The question of whether this criticism is fair involves assessing whether Open AI's leadership made reasonable governance decisions or whether they have truly abandoned their founding principles. Reasonable people can disagree on this question—some argue that securing investor capital was necessary to remain competitive in AI, while others contend that Open AI sacrificed its foundational nonprofit mission for corporate interests.

Governance and Fiduciary Duty Questions

Another layer of complexity involves fiduciary duty questions. When organizations transition from nonprofit to hybrid structures, how much accountability do nonprofit leaders owe to original stakeholders like early founder-investors? Typically, nonprofit leaders owe their primary fiduciary duty to the organization's mission and to broader public interest rather than to particular investors. However, Musk might argue that early investors like himself should have negotiated explicit protections or governance rights before consenting to such a fundamental structural change.

The Broader AI Industry Context and Competitive Positioning

The AI Talent Wars and Competitive Stakes

Musk's lawsuit against Open AI is occurring within a context of intense competition for AI talent, capital, and market share. Open AI had emerged by the time of Musk's lawsuit as one of the world's most valuable privately-held companies, with a market position that had made it an indispensable provider of AI technology to businesses and consumers worldwide. Musk's x AI, founded more recently, is attempting to establish itself as a competitor in this landscape.

Open AI and Microsoft have suggested that Musk's litigation is strategically motivated—designed to occupy Open AI's leadership bandwidth, create uncertainty about the company's valuation and governance, and potentially distract from competitive efforts. If this motivation is accurate, it raises questions about whether litigation is an appropriate forum for addressing Musk's genuine grievances or whether it represents a weaponization of the legal system for competitive advantage.

The Role of AI Regulation and Public Policy

AI regulation and governance have become increasingly central to industry strategy. Open AI has positioned itself as a responsible AI company engaged with regulatory authorities and safety considerations. Musk has been publicly critical of Open AI's governance and safety practices and has advocated for different approaches to AI development. The lawsuit thus occurs within a broader contest over how the AI industry should be organized, governed, and developed—questions that ultimately affect public policy and regulation rather than merely private contractual disputes.

Likely Outcomes and Timeline Considerations

The Ruling on Expert Testimony Exclusion

The immediate question before the court is whether Judge will exclude Wazzan's testimony based on unreliability. If the judge sides with Open AI and Microsoft and excludes the expert opinion, Musk's damages claim becomes substantially weakened. Without expert testimony to support the

Alternatively, if the judge admits Wazzan's testimony, the case proceeds to trial where a jury must evaluate the competing expert opinions and arguments from both sides. Open AI and Microsoft would present their own expert testimony explaining why Wazzan's methodology is flawed, and they would argue that damages should be significantly lower—or zero if they prevail on the merits of Musk's underlying claims.

Timeline and Settlement Possibilities

Litigation of this magnitude typically involves years of proceedings, discovery disputes, expert witness exchanges, and potentially appeals. However, parties sometimes settle complex cases rather than litigate to completion, particularly when outcomes are uncertain and legal costs mount. Settlement discussions might involve Musk accepting a payment from Open AI in exchange for dismissal of his claims—potentially billions of dollars but far less than the

Open AI and Microsoft have strong incentives to resolve the litigation rather than allow a jury to potentially award unprecedented damages. Conversely, Musk has incentives to settle only if Open AI and Microsoft will make an offer substantially exceeding his assessment of litigation risk and expected outcomes. The negotiating dynamics depend heavily on the judge's preliminary rulings on evidence and the strength of the parties' positions.

Key Takeaways and Broader Implications

The Musk lawsuit against Open AI and Microsoft raises several important issues extending beyond the specific facts of this case. First, it illustrates the challenges courts face when evaluating expert testimony in complex valuation disputes involving unprecedented technologies and organizations. The methodologies available for valuing contributions to cutting-edge AI companies may not be adequately addressed in traditional financial textbooks or established expert practice standards.

Second, the case highlights tensions between early contributors to ventures and organizational leadership regarding credit and compensation as ventures achieve massive subsequent success. While Musk made documented early contributions to Open AI, the majority of the organization's current value may have been created by others in years after his departure. Fairly attributing credit across these diverse contributors and circumstances remains difficult.

Third, the lawsuit reflects broader questions about whether nonprofit-to-for-profit transitions adequately protect original stakeholders and whether organizational governance structures sufficiently reflect founding principles as circumstances change. Musk's grievances regarding Open AI's mission drift may be substantive even if his specific damage claims are not legally valid.

Finally, the case demonstrates how litigation can become a tool for competitive advantage in high-stakes technology industries. Whether this represents legitimate dispute resolution or inappropriate weaponization of the legal system remains contested.

FAQ

What is the primary basis of Elon Musk's lawsuit against Open AI and Microsoft?

Musk's lawsuit alleges that Open AI has abandoned its founding nonprofit mission and transformed into a for-profit enterprise that wrongfully enriched itself and Microsoft through Musk's early contributions. He claims Open AI and Microsoft owe him damages between

How did financial economist C. Paul Wazzan calculate the damage figures?

Wazzan analyzed four factors: Musk's documented $38 million financial contribution before leaving Open AI in 2018, a proposed 51.2 percent equity stake Musk proposed in 2017 that was never granted, Musk's 53 percent ownership in x AI based on public valuations, and intangible contributions like employee recruitment and reputation lending. However, his methodology has been criticized as novel, not based on established valuation practices, and essentially constructed to reach predetermined damage figures rather than following objective analytical principles.

What are Open AI's and Microsoft's main objections to the damages calculation?

Open AI and Microsoft argue that Wazzan's analysis contains multiple fundamental flaws: it relies on a hypothetical equity deal that never actually occurred; it uses x AI's valuation as a basis despite x AI being a completely separate company with different value drivers; it allegedly double-counts Microsoft's financial contributions; it dismisses all other contributors' efforts (researchers, engineers, product teams, co-founders) as contributing "zero percent" of current value; and it represents a novel methodology that appears cherry-picked to reach desired conclusions rather than following established financial analysis practices. They've filed motions to exclude his testimony as unreliable.

Why does Wazzan's treatment of other contributors matter legally and ethically?

Wazzan's methodology attributed 50 to 75 percent of Open AI's current value to Musk's early contributions while assigning zero percent to the scientists, engineers, and developers who actually created Chat GPT, the researchers and product teams who scaled the systems for global deployment, and co-founders like Sam Altman and Greg Brockman who remained with the organization through its period of greatest achievement. This attribution inverts the historical record of contribution and raises fundamental questions about whether the methodology has any validity. It suggests Wazzan may have selectively included only factors that supported inflating damages rather than comprehensively analyzing all value contributors.

What is the Daubert standard and how does it apply to this case?

The Daubert standard requires courts to evaluate whether expert testimony is sufficiently reliable to be admitted as evidence. Courts assess factors including whether the methodology is testable, whether it has been subjected to peer review, whether it's generally accepted in the relevant professional community, and whether it has known error rates. Wazzan's novel valuation methodology—apparently custom-built for this litigation without established acceptance in financial economics—raises significant Daubert concerns. Open AI and Microsoft are asking the court to exclude Wazzan's testimony as failing these reliability standards.

Could judges and juries reasonably reject Musk's damage claims even if the expert testimony is admitted?

Yes. The

How does this case relate to broader questions about nonprofit-to-for-profit transitions?

Open AI was founded as a nonprofit research organization with an explicit mission to ensure artificial general intelligence benefits humanity. Over time, Open AI transitioned to a hybrid structure with a for-profit subsidiary funded by Microsoft and other investors, arguing that capital intensity required this change. Musk's lawsuit partially challenges whether this transition properly honored founding principles and early stakeholders' expectations. The case raises legitimate governance questions about how organizations should manage transitions between structures and whether founding stakeholders retain entitlements during such changes.

What are the likely outcomes and timelines for this litigation?

In the short term, the court must rule on whether Wazzan's expert testimony will be admitted or excluded based on reliability questions. If excluded, Musk's case is weakened unless he can present alternative expert testimony. If admitted, the case proceeds to trial where juries must evaluate competing expert opinions. The entire litigation process typically involves years of proceedings and could ultimately be settled rather than decided at trial. Either outcome—a judge's preliminary ruling, a jury verdict, or a settlement—would have significant implications for precedent regarding how courts value early contributions to technology ventures.

How does this lawsuit relate to competition between Open AI and Musk's x AI company?

Open AI and Microsoft have characterized Musk's lawsuit as part of a harassment campaign designed to slow Open AI's growth and provide competitive advantage to x AI. While Musk likely has genuine grievances about his treatment and Open AI's direction, the timing and magnitude of the damage claim raise questions about whether litigation is being used for competitive advantage. This dynamic illustrates how legal disputes in the technology industry sometimes involve competitive strategy beyond pure legal merits. Regardless of Musk's motivations, the core legal questions about whether his damages claims are valid remain substantive.

What comparable situations exist in technology industry history where founders disputed contribution valuation?

The technology industry has witnessed numerous disputes between founders and early investors regarding credit for company success—from the early days of personal computing to internet companies to social media platforms. However, most disputes are resolved either through enforcement of explicit equity agreements and vesting schedules or through settlements rather than unprecedented damage awards. Musk's case is notable for seeking damages of extraordinary magnitude based on expert-derived valuation of contributions that were never the subject of explicit written agreements. This approach differs from historical precedent and creates novel challenges for courts evaluating valuation methodologies and standards.

Alternatives and Related Solutions

For developers and teams involved in complex document generation, data analysis, and workflow automation related to legal proceedings or business disputes, platforms like Runable offer AI-powered solutions for automated content generation and report creation at a fraction of the cost of traditional services. At $9/month, Runable's AI agents can assist with creating detailed analyses, documentation of findings, and structured reports—useful capabilities when managing information-intensive processes. While Runable isn't designed specifically for litigation support, its AI slides, AI docs, and AI reports features demonstrate how modern automation platforms can reduce the time and expertise required for creating complex documentation.

Developers building tools for contract analysis, valuation modeling, or legal research might also consider how AI-powered automation could streamline workflows. Runable's approach to automating content generation could inspire approaches to automating preliminary legal analysis or financial documentation preparation, though formal legal opinions and litigation strategy would still require specialized legal expertise.

![Elon Musk's $134B OpenAI Lawsuit: The Math Controversy Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/elon-musk-s-134b-openai-lawsuit-the-math-controversy-explain/image-1-1768851418546.jpg)