Introduction: The Dojo Return Nobody Expected

Last year, everyone thought Dojo was dead. Elon Musk had posted on X explaining that spreading Tesla's resources across two different AI chip designs didn't make sense. The company would focus entirely on the AI5 and AI6 chips built for on-board inference in Tesla vehicles. Dojo, the ambitious in-house supercomputer project designed to process massive amounts of video data and train Full Self-Driving software, seemed like a casualty of corporate pragmatism.

Then, in early 2025, Musk announced the project's resurrection. According to Engadget, this isn't just another tech pivot. The restart signals something profound about where Tesla believes the autonomous driving competition is headed, and it reveals the company's conviction that training capabilities matter as much as inference speed. More importantly, Musk's claim that Dojo 3 will feature "space-based AI compute" introduces an entirely speculative but increasingly discussed approach to solving the data center problem. Whether this happens or not, the announcement forces us to confront real questions about computational architecture, power consumption, and how companies actually build AI systems that work in the real world.

The story here isn't just about a supercomputer coming back online. It's about the tension between pragmatism and ambition in AI infrastructure, the growing doubt over whether traditional data centers can scale efficiently, and whether Tesla has learned anything from its history of missed timelines and overconfident predictions.

Here's what we actually know: Dojo is restarting. AI5 chip design is in "good shape," according to Musk. And Tesla is betting billions on the idea that training neural networks on real driving data will outpace competitors' approaches. Everything else is speculation, hope, and technical ambition.

Let's walk through what's actually happening, why it matters, and why you should be skeptical of Musk's timelines.

What Is Tesla's Dojo Supercomputer, Really?

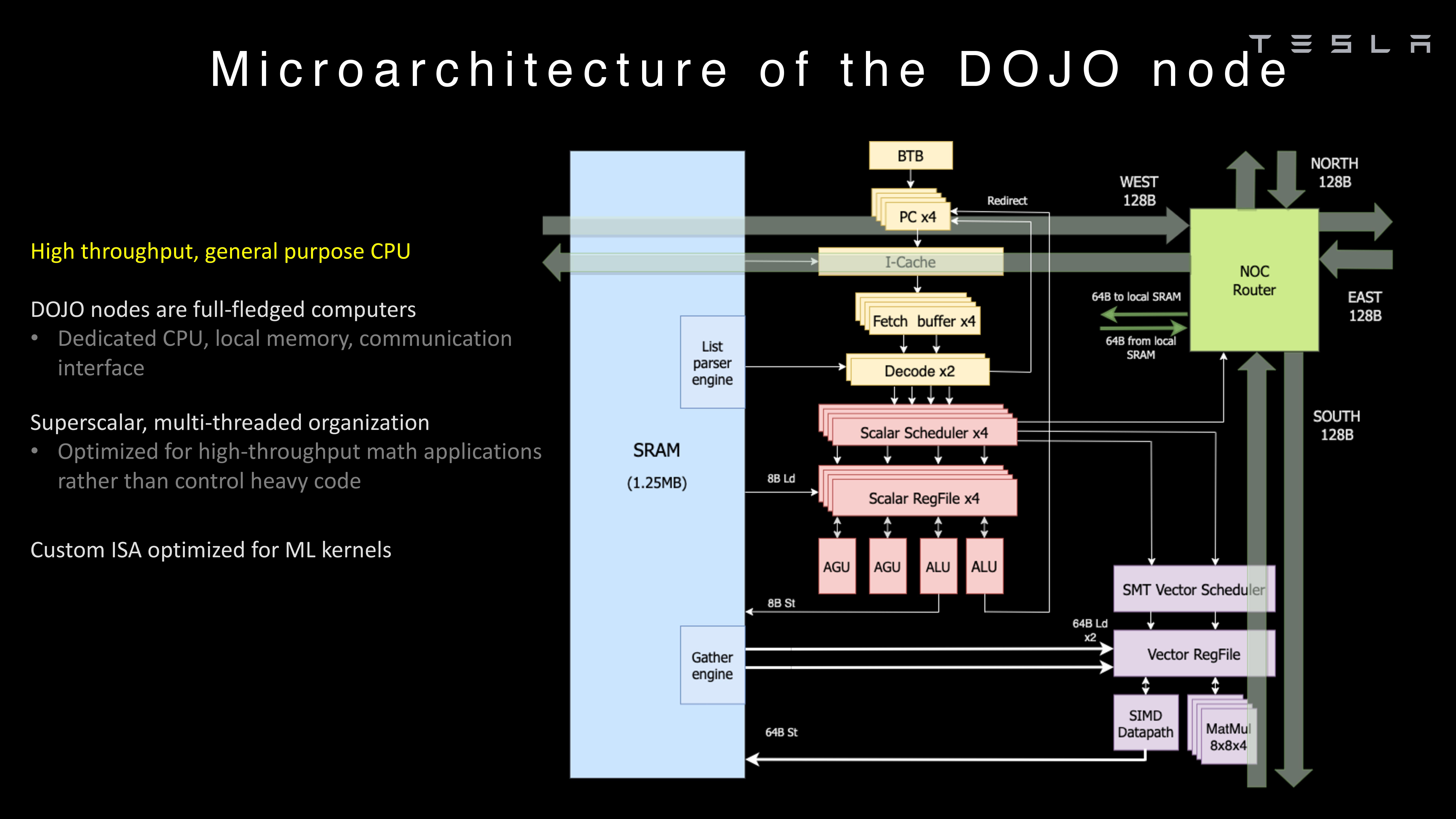

Dojo isn't a generic AI system. It's purpose-built for one specific problem: taking the continuous video streams captured by Tesla vehicles and converting them into training data that teaches Full Self-Driving (FSD) to navigate the world safely.

Every Tesla on the road today is essentially a rolling data collection platform. Multiple cameras capture the environment from different angles. Radar and ultrasonic sensors feed additional information. All of this data streams to Tesla's servers, creating a real-time corpus of driving scenarios—highway merges, pedestrian crossings, weather changes, unusual road conditions, construction zones, accidents.

That raw footage is useless without processing. Dojo's job is to take billions of hours of video, extract relevant frames, label them with ground truth (what actually happened), and feed that into the neural networks that power FSD. The quality of this training loop directly determines how well FSD handles edge cases.

This is fundamentally different from training language models on internet text. Self-driving requires spatial reasoning about three-dimensional environments, understanding physics, predicting human behavior, and making safety-critical decisions. A hallucination in a language model is embarrassing. A hallucination in FSD is dangerous. The stakes are higher, and the training approach needs to reflect that.

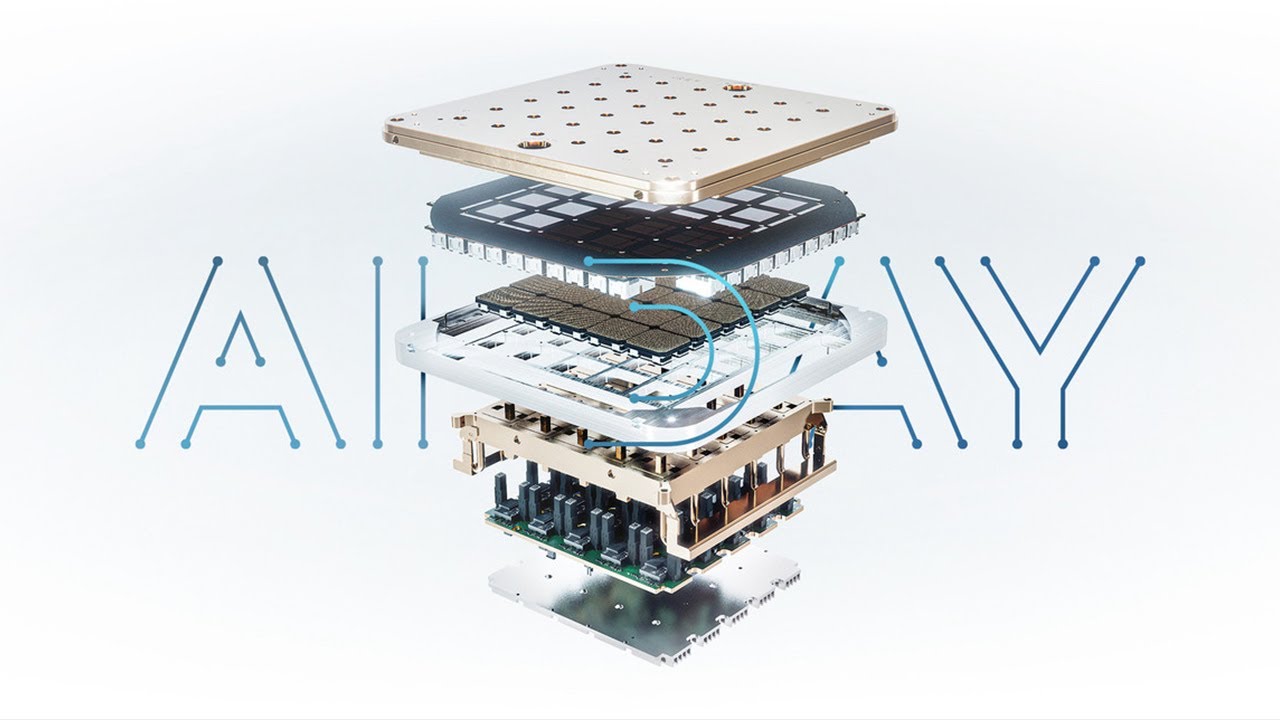

Dojo's architecture reflects this need for scale and specificity. The system is designed to process data at speeds that make commercial sense—handling terabytes of video per day, running inference pipelines to extract training examples, and managing the computational burden of updating neural networks based on real-world driving patterns.

When Musk paused the project last year, he wasn't abandoning training entirely. AI5 and AI6 chips can handle training work, just not at the scale Dojo was built to achieve. Those chips were optimized for what they do best: running inference on hardware that fits inside a car, with power budgets measured in watts, not megawatts.

The reason Musk is restarting Dojo now is that he apparently believes Tesla has hit a ceiling with AI5's training capability. To keep improving FSD, the company needs dedicated hardware that can absorb massive amounts of data processing without competing for resources with the inference optimization work.

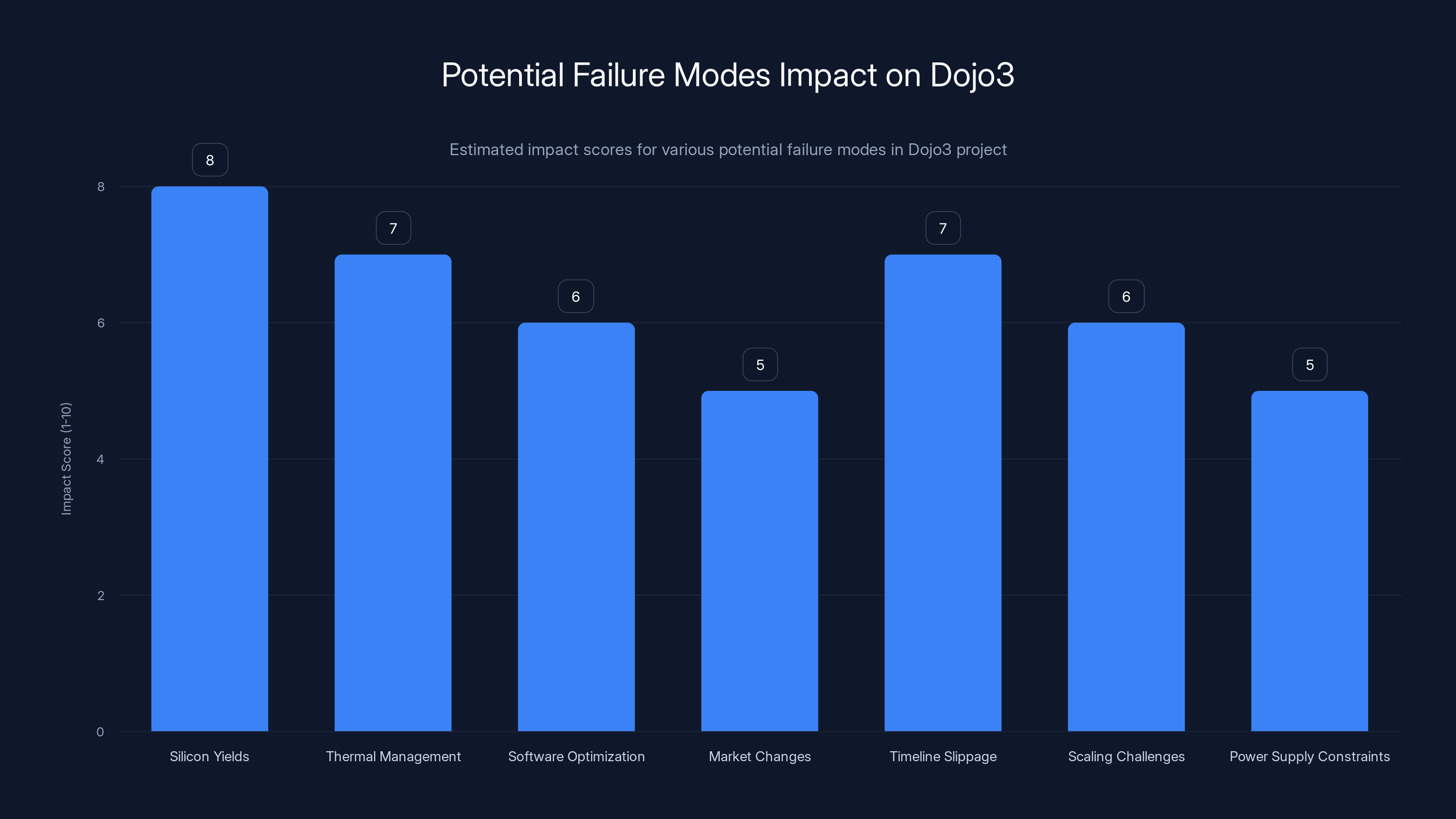

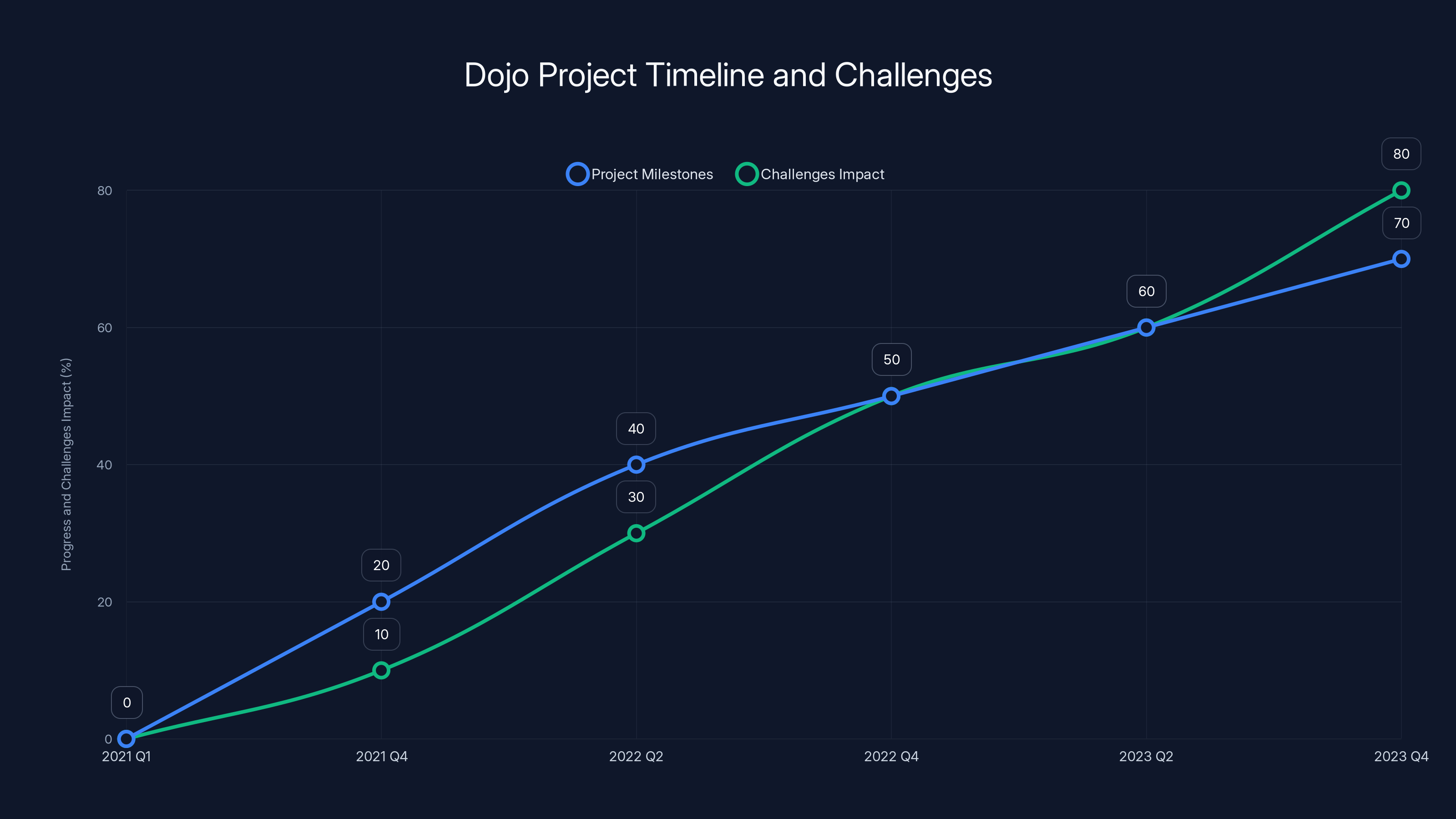

Silicon yields and timeline slippage are estimated to have the highest impact on Dojo3's success, with scores of 8 and 7 respectively. Estimated data.

The Original Dojo Vision: Ambition Meets Engineering Reality

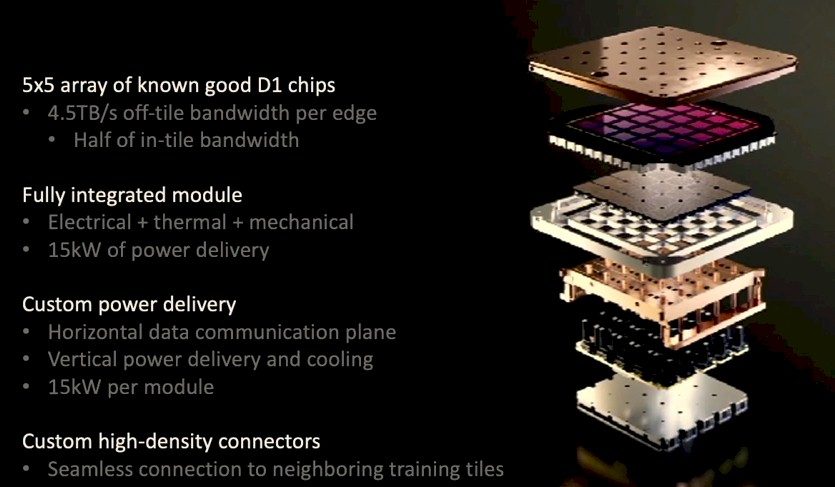

When Dojo first launched, it represented the most ambitious in-house semiconductor and supercomputer project any automotive company had ever attempted. Tesla wasn't just buying infrastructure from cloud providers. It was designing custom silicon, building specialized cooling systems, and architecting software stacks that didn't exist yet.

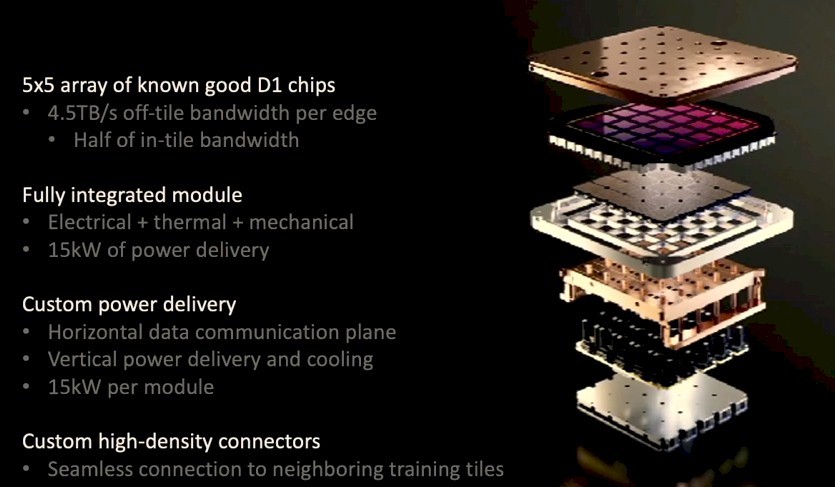

The original vision included custom AI processors called "D1" chips, engineered specifically for the workloads of training neural networks on video data. Unlike GPUs or TPUs designed for general AI tasks, the D1 was supposed to excel at the specific operations Dojo needed: matrix multiplications, convolution operations, and the data movement patterns typical of computer vision workloads.

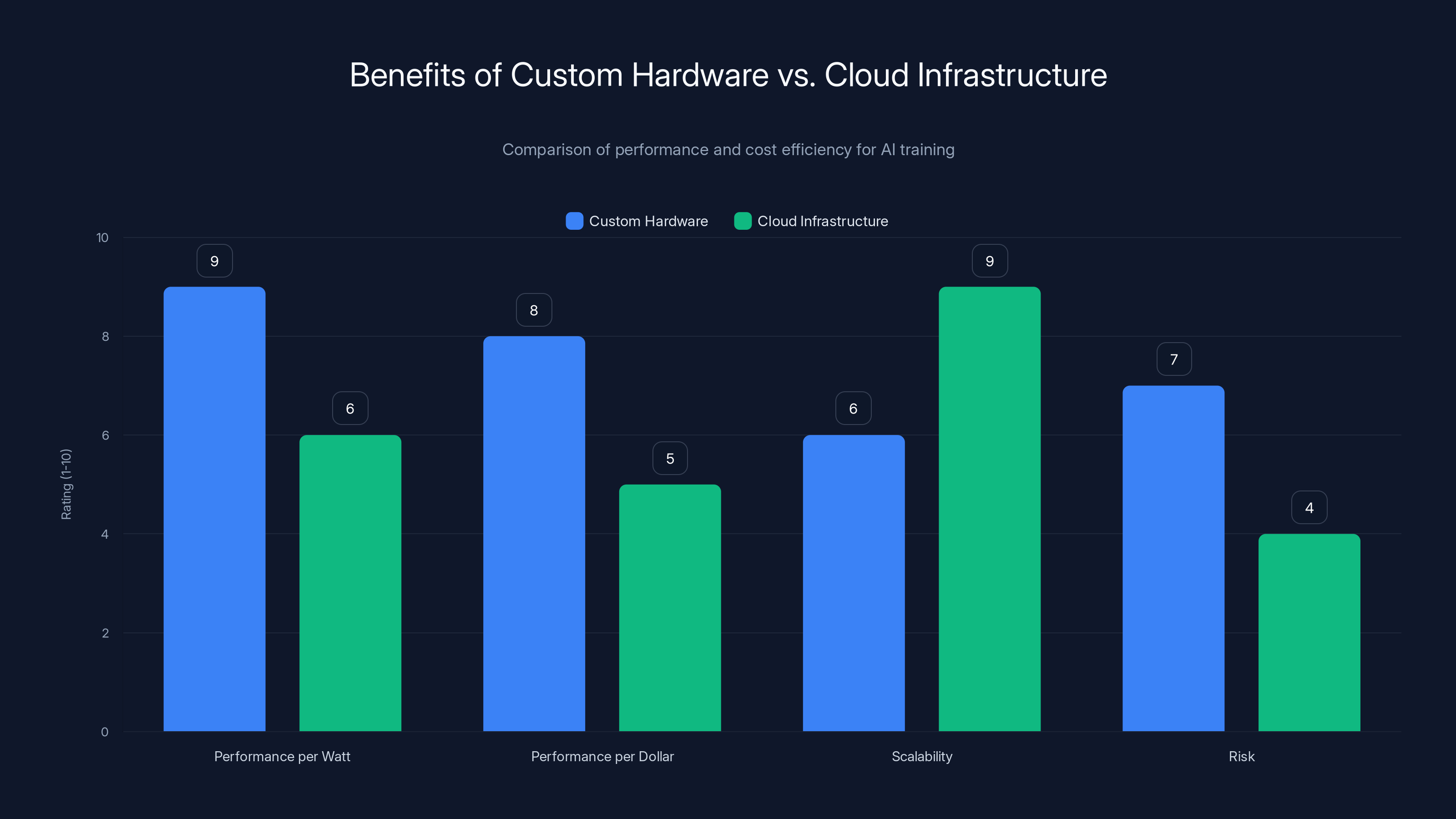

This makes economic sense at scale. General-purpose hardware always carries overhead for capabilities you don't need. If you're running a single workload billions of times per day, custom silicon can achieve better performance per watt and better performance per dollar than off-the-shelf solutions. It's why Google built TPUs, why Meta built custom training accelerators, and why Microsoft invested heavily in custom networking hardware for Azure.

The problem: custom silicon projects are slow, expensive, and risky. You have to design the chip, manufacture test runs, debug hardware and software simultaneously, iterate designs, and only then move to production volumes. A single mistake at the silicon level can mean six-month delays. Thermal issues found in testing can require complete redesigns. Software teams have to optimize for hardware that doesn't exist yet.

Tesla announced Dojo in 2021 with aggressive timelines. By 2023, the project still wasn't delivering at the scale originally promised. Thermal challenges, software optimization delays, and integration complexities all contributed to slower-than-expected progress. Meanwhile, the AI landscape shifted dramatically. GPUs became more abundant post-crypto crash. Transformer architectures evolved. The specific vision processing approach Dojo was optimized for had already evolved.

Musk's 2024 decision to pause Dojo made practical sense: why wait for custom silicon to mature when AI5 inference chips could handle training work in the interim? Why tie up engineering resources? The company pivoted to getting FSD improvements out faster using available hardware.

But pivoting away from custom hardware meant accepting a constraint: you're limited to whatever training throughput AI5 chips can provide. After a year of hitting those limits and wanting to accelerate FSD development further, Tesla decided the time had come to restart the specialized supercomputer project.

Why AI5 and AI6 Aren't Enough for the Full Vision

Here's something important to understand about chip design tradeoffs: you can't optimize for everything. Every design choice involves compromises.

AI5 and AI6 are inference-optimized. This means they're engineered to prioritize: running models quickly with low latency, consuming minimal power, and fitting within the thermal and electrical constraints of a car. They're brilliant at what they do. But inference optimization often conflicts with training optimization.

Training requires different hardware characteristics. You need high memory bandwidth to shuffle data around during backpropagation. You need fast floating-point math. You need efficient synchronization between processing units when running distributed training across multiple chips or systems. Power consumption matters less acutely because you're running in data centers, not inside vehicles.

A chip optimized for inference typically has smaller caches, smaller memory, and architectural choices tuned for feedforward prediction. A chip optimized for training typically has larger memory hierarchies and interconnects designed for the two-directional data movement that backpropagation requires.

You can use an inference chip for training. Meta does this regularly, training models on GPUs designed for gaming and inference. It works, but it's never as efficient as hardware built specifically for the task. You're paying performance and power penalties.

Musk's statement that AI5 and AI6 chips would be "at least pretty good for training" reflects this reality. Not perfect. Pretty good. Which is fine when you're prioritizing engineering focus and avoiding resource dilution. But it becomes a bottleneck once you're trying to maximize FSD improvement velocity.

Tesla's engineers presumably concluded that the gap between "pretty good" and "purpose-built" has become too costly. Every month of slower training means slower FSD iteration. Every competitor using better training infrastructure means potential competitive disadvantages accumulating. The decision to restart Dojo reflects confidence that the opportunity cost of not having it outweighs the engineering burden of building it.

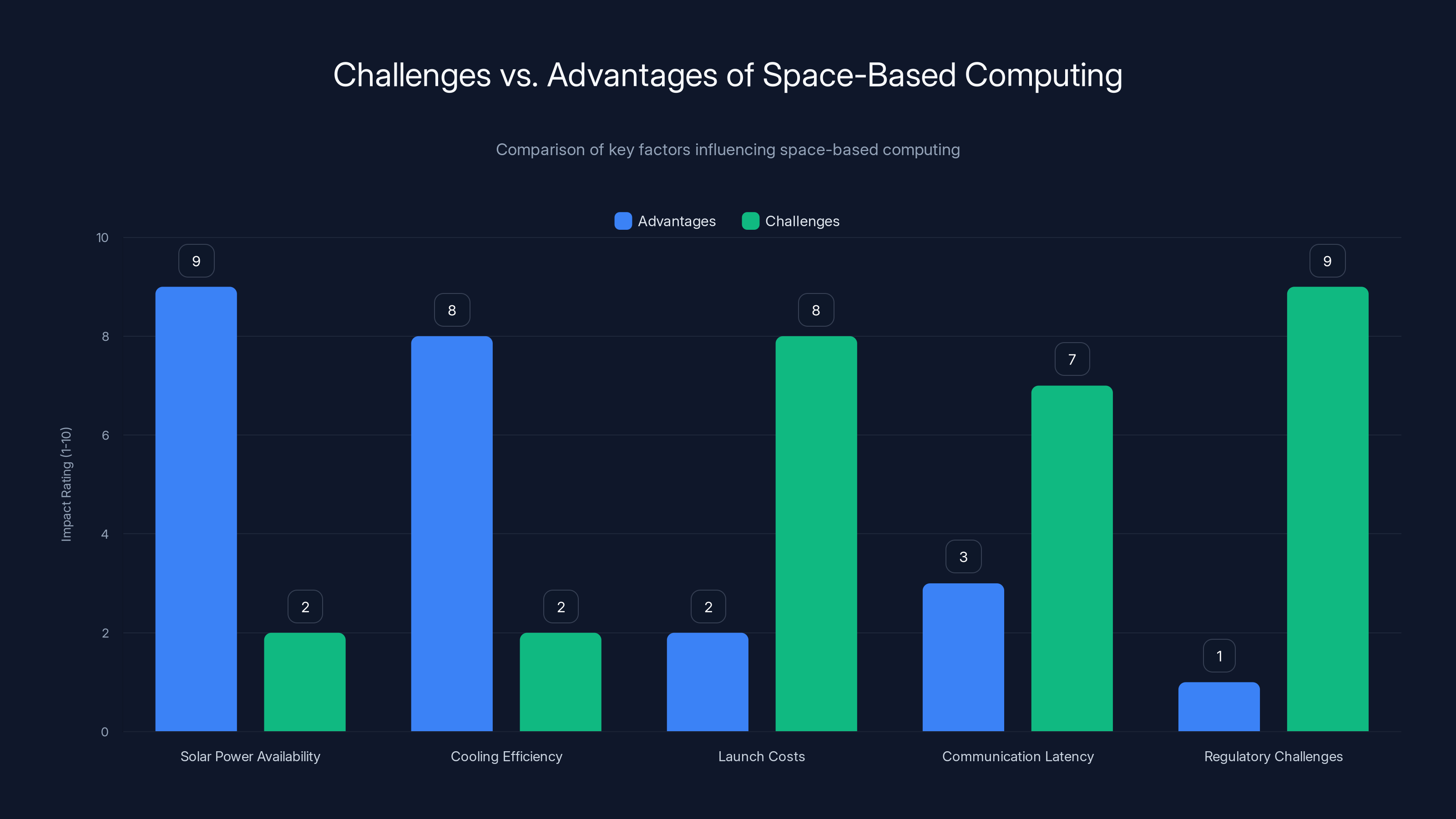

While space-based computing offers significant advantages in solar power availability and cooling efficiency, it faces major challenges in launch costs, communication latency, and regulatory issues. Estimated data based on topic discussion.

The Space-Based Computing Angle: Vision or Hype?

This is where Musk's announcement gets weird. Not just ambitious, but actually weird in the technical sense.

Dojo 3, according to Musk, will feature "space-based AI compute." The concept: build data centers in orbit where you get continuous access to solar power and the ability to radiate heat directly into the vacuum of space without the challenges of cooling systems on Earth.

It's not entirely a new idea. Advocates have been discussing space-based computing for a few years now. The theoretical advantages are real: the sun delivers about 1,361 watts per square meter to Earth's orbit, a resource available 24/7. Earth-based data centers require nighttime power, require cooling systems that consume massive amounts of water or energy, and have geographic limitations based on where power infrastructure exists and where cooling is viable.

The challenges are equally real and mostly unaddressed: orbital debris, launch costs, reliability requirements for remote systems, communication latency between space and Earth, radiation effects on electronics, resupply and maintenance logistics, liability issues, and regulatory frameworks that don't yet exist.

Launch costs have fallen dramatically. Space X's Falcon 9 now costs roughly

Then there's the problem of latency. Data stored in space-based compute needs to travel to Earth, to Tesla's servers, to vehicles, and back. At the speed of light through fiber optics and satellite links, that's significant latency. Not impossible to work around, but not trivial either.

Why would Musk make this claim? Possibly because: (1) he genuinely believes space-based computing is the future and wants to position Tesla as a pioneer, (2) he's testing the viability of the concept publicly to gauge engineering and investment interest, or (3) it's aspirational messaging that will evolve into something more terrestrial once engineering realities set in.

Historically, Musk's most ambitious claims have taken longer than predicted or shifted into different forms than originally described. The full context matters: he's an engineer thinking out loud about problems that genuinely exist (power consumption in data centers, heat dissipation challenges, geographic constraints on where compute can be located). Space-based solutions might eventually become viable. But the timeline between "interesting concept" and "production system" is measured in decades, not years.

Dojo 3 will almost certainly be Earth-based, at least initially. The restart announcement mentions space-based computing as part of the longer-term vision. Which is fine as vision. Vision drives innovation. But it's worth noting that between vision and reality sits a vast gap of engineering, cost, and practical constraints.

How Dojo Integrates with Full Self-Driving Development

The relationship between Dojo and FSD is direct but often misunderstood. Dojo doesn't run FSD. It trains the models that FSD uses.

The pipeline looks like this: Tesla vehicles collect video and sensor data continuously. That raw data flows to Tesla's servers. Dojo processes this data—extracting useful frames, applying computer vision pipelines to identify objects and extract features, generating labels and ground truth. The processed data feeds into training runs that update FSD's neural networks. Those updated models get compiled and pushed to vehicles as software updates.

The quality of this training loop determines FSD's quality. If you're feeding garbage data into training, you get garbage models. If you're missing important edge cases in your training data, your model won't handle them well when it encounters them in the real world. If your labeling is inaccurate, your models learn incorrect patterns.

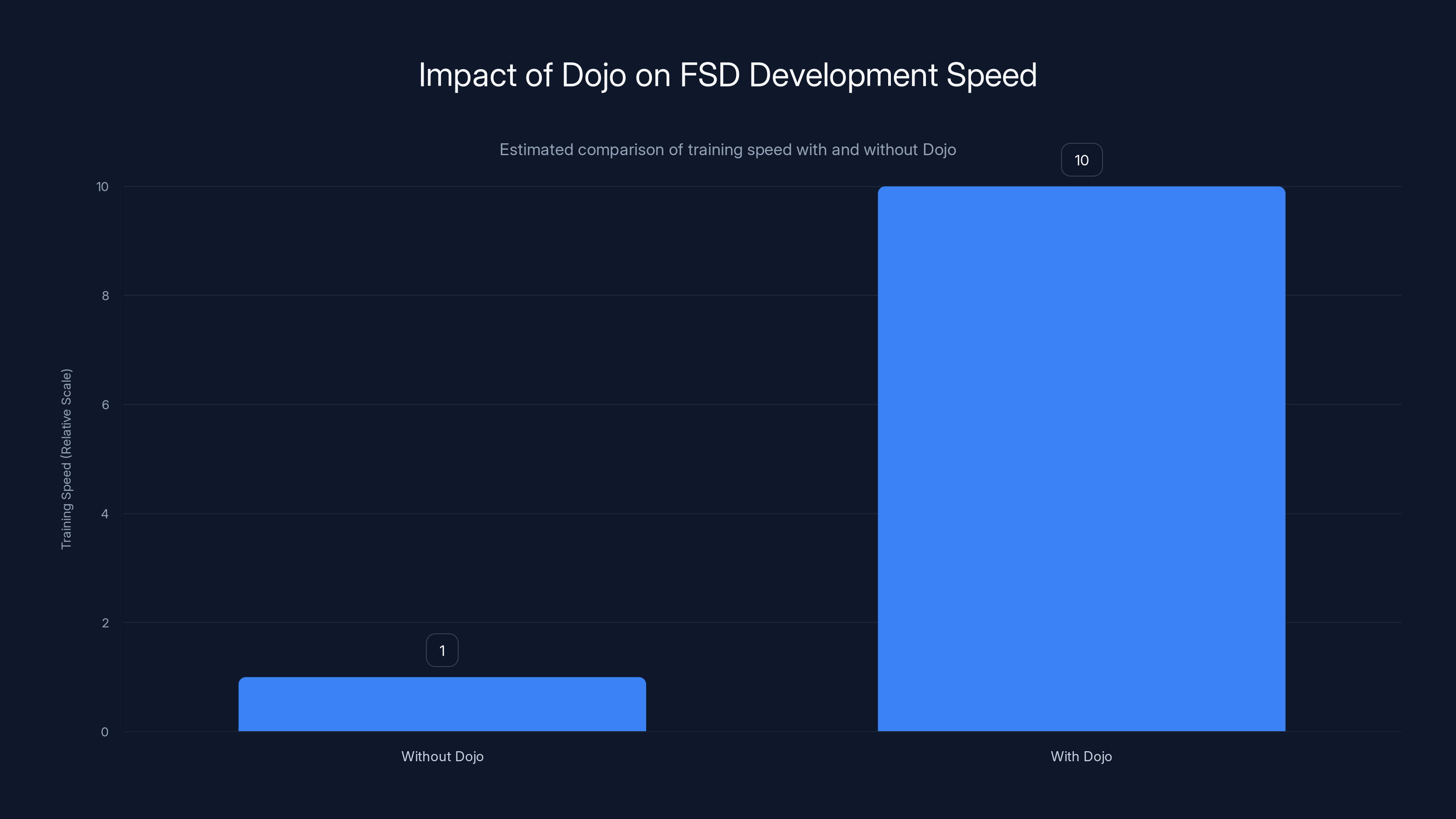

Dojo's power determines the iteration speed. Faster data processing means faster model updates. Faster training means more experiments per week. More experiments mean better tuning and faster convergence toward better-performing models.

This is why scale matters so much in self-driving. Every company working on autonomous driving collects data from their fleet. The advantage goes to whoever can process and learn from that data fastest. If Tesla can run training 10 times faster than competitors, and all else is equal, Tesla's FSD will improve 10 times faster. That compounds over time. It becomes a moat.

The restarting of Dojo signals confidence that this training loop is where the competitive advantage lies. FSD's current limitations—slower speeds in complex urban environments, occasional misidentifications, conservative decision-making in ambiguous situations—can be addressed by training on more data and learning from more edge cases. Dojo is infrastructure to make that possible at scale.

It's also worth noting that training for self-driving is never truly "done." You don't train a model once and ship it forever. Real-world environments change (new road designs, weather patterns, traffic behaviors evolve). Regulatory environments evolve. Competitor products evolve. Continuous training on new data is standard operating procedure. Having dedicated infrastructure for that makes strategic sense.

Musk's Track Record: Promises Versus Delivery

Before taking the Dojo restart announcement at face value, it's worth calibrating expectations based on history.

Elon Musk has made hundreds of public promises about Tesla products and timelines. Some came true. Many didn't. Many came true much later than announced. Some morphed into different products than originally described.

Full Self-Driving offers a perfect case study. In 2015, Musk predicted that all Tesla cars would be capable of driving themselves coast-to-coast by 2017, with no human intervention and no need to touch the wheel. It's now 2025, and FSD operates on public roads in limited beta with significant human oversight still required. It's far better than it was in 2016, but the original timeline was off by a decade.

This isn't unique to FSD. The Roadster was supposed to launch in 2018, with a next-generation version following years later. It hasn't shipped yet. The Semi was supposed to start production in 2019. Production began in 2023, years late. The Cybertruck had numerous promised features that didn't make it into the production version.

None of this is to say Musk's announcements are worthless. They often correctly identify real technical problems and reasonable solutions. But the timelines are almost always wrong, sometimes by factors of several years. The scope often shifts. Engineering challenges that seemed manageable in hindsight proved more difficult.

This context matters for Dojo. It's entirely plausible that Tesla will restart Dojo. The infrastructure is valuable and the engineering challenges are real but solvable. But will it deliver training throughput on the promised timeline? Will space-based computing actually happen? Will Dojo 3 be ready for production deployment when announced? History suggests skepticism is warranted.

That said, Musk's willingness to announce ambitious projects and pursue them despite delays has shaped Tesla's competitive position. The company has moved faster on electrification and autonomous driving than competitors partly because it committed to hard timelines and poured resources into meeting them, even when it meant overoptimistic forecasting.

The Dojo restart should be understood as a long-term commitment with uncertain timelines, not as a near-term product announcement.

Custom hardware offers superior performance per watt and dollar compared to cloud infrastructure, though it involves higher risk. Estimated data based on typical industry insights.

Competing Approaches to Training Infrastructure

Tesla isn't the only company building specialized training infrastructure. The landscape is complex, and different approaches reveal different strategic bets.

Large cloud providers like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft rely heavily on GPUs and custom TPUs. They've optimized their data center infrastructure for serving many different customers and many different workloads. Google's TPUs are purpose-built for training transformer-based models. They're powerful, efficient for that specific task, but if your workload doesn't match transformer training, they're less optimal.

Meta built custom training infrastructure called MTIA (Meta Training and Inference Accelerator). It's designed for Meta's specific needs: training and running large language models. Meta's bet is that vertical integration—owning the full stack—lets them extract more performance and efficiency than relying on generalist cloud hardware.

Nvidia dominates with H100 and now H200 GPUs. They're not custom-built for any single task but are flexible enough to handle multiple workloads well. The advantage: proven, mature, available now. The disadvantage: they consume massive amounts of power and aren't ideal for any specific task.

Tesla is betting that dedicated hardware for their specific problem (training on video data for autonomous driving) can beat generalist solutions through specialization. It's the right instinct, but it comes with execution risk.

Each approach reflects a different tradeoff: flexibility versus efficiency, time-to-capability versus long-term advantage, reliance on partners versus vertical integration.

Tesla's approach, if executed well, should provide efficiency advantages over using generic hardware. If executed poorly, it risks delays and resource diversion from other priorities.

The Real Drivers Behind the Restart Decision

Why restart now? The press release reasons given (AI5 design is good enough for inference) are probably only part of the story.

Competitive pressure is likely significant. Waymo has been deploying robotaxis in Phoenix and expanding to other cities. The company has access to Alphabet's infrastructure and can presumably run training at scale. Cruise (despite recent setbacks) was deploying robotaxis in San Francisco. Other startups are making progress. If Tesla's FSD is falling behind on improvement velocity, that's a strategic problem.

Another factor: data accumulation. Tesla has been collecting driving data for years. That corpus is growing continuously. At some point, having massive amounts of high-quality training data becomes a valuable asset only if you have infrastructure to actually learn from it. If competitors' data is smaller but their training infrastructure is better, Tesla's data advantage evaporates. Restarting Dojo is a way to convert data accumulated over years into competitive capability.

There's also a credibility factor. Tesla has positioned itself as a full-stack AI company, handling perception, decision-making, and hardware. Building custom supercomputers aligns with that positioning. It's a signal to investors, customers, and partners that Tesla is serious about AI as a core capability, not just as software bolted onto existing infrastructure.

From a capability perspective, the question of training throughput is real. As FSD gets more sophisticated, neural networks get larger, and the amount of data needed to train them effectively grows. You hit diminishing returns using AI5 as your training platform. Building Dojo is the logical next step in the progression.

Finally, there's the timing of other Tesla announcements. The AI6 chip is coming. New vehicle models are coming. FSD development is accelerating. All of these probably create pressure to have better training infrastructure. You don't want to be in a position where great new hardware ideas are bottlenecked by training capability.

Power Consumption: The Scaling Problem Dojo Actually Solves

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough: power consumption is becoming the limiting factor in AI scaling, not computation speed or memory.

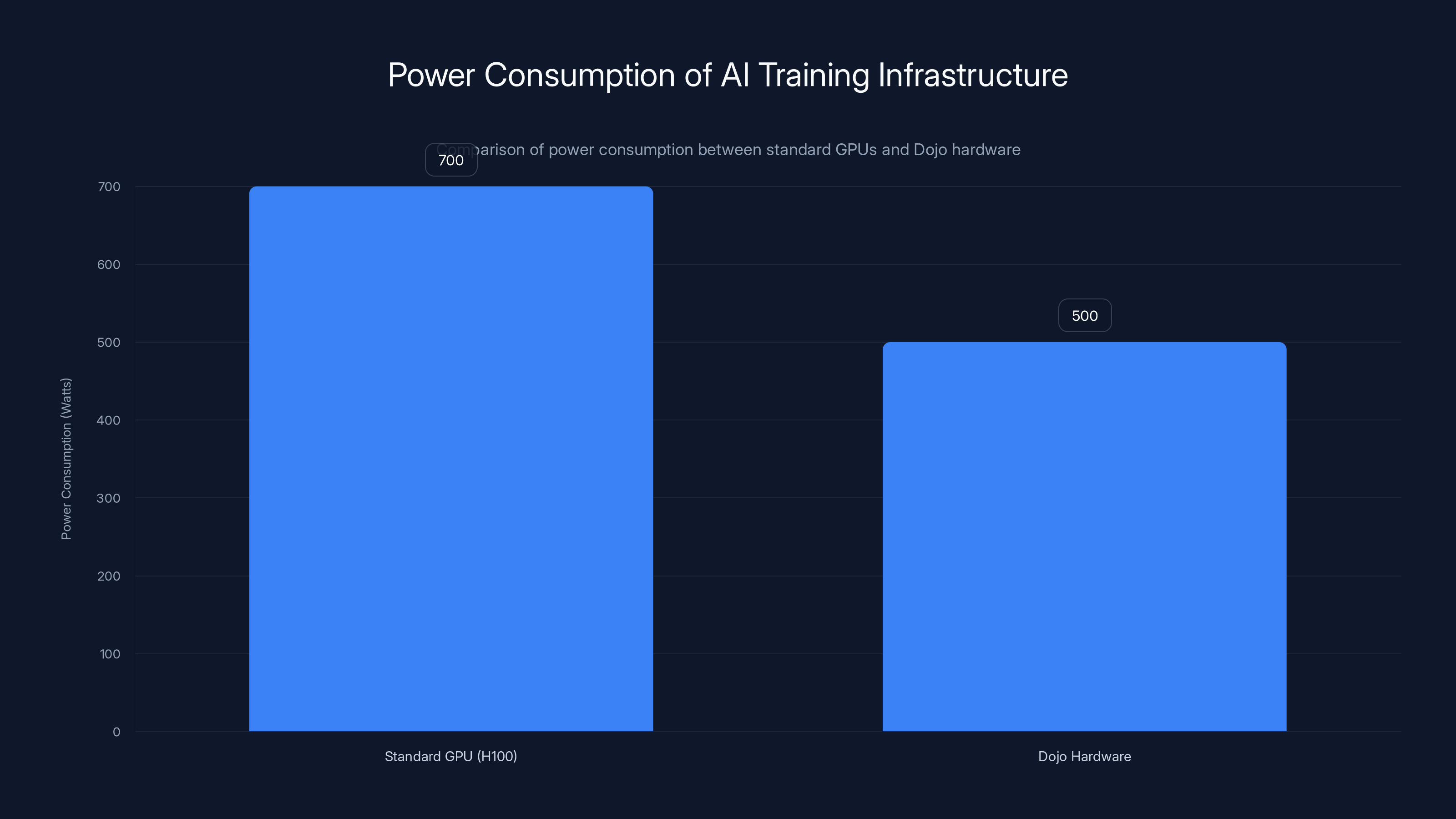

A modern GPU like the H100 consumes 700 watts in full utilization. A large training run might use hundreds or thousands of GPUs. A data center containing 10,000 H100s draws 7 megawatts of power continuously. That requires dedicated power infrastructure, cooling systems that can handle 7 megawatts of heat rejection, and access to power grids with sufficient capacity.

You can't just put a 7-megawatt data center anywhere. Geographic constraints matter. Power must be cheap and available. Cooling must be accessible (that's why data centers cluster in cool climates or near water). Real estate must be available.

These constraints create scaling limits. If you're bound by the number of data center locations where you can deploy training infrastructure, you're limited in your ability to scale training.

Custom hardware like what Dojo aims to provide can partially solve this. Better efficiency per watt means less power draw for the same computation. Less power draw means easier scaling, fewer geographic constraints, potentially lower costs.

The fundamental equation:

You can increase training throughput by getting more compute power, by improving efficiency, or by accepting higher power consumption. Custom hardware lets you improve efficiency per watt, changing the tradeoff curve.

Musk's mention of space-based computing reflects thinking about this problem at the extreme. "What if we could put compute where power is unlimited and cooling is free?" It's a reasonable question to ask, even if the answer isn't practical in the near term.

The reason Dojo matters for Tesla's long-term capability is precisely this scaling question. As FSD neural networks grow and training datasets grow, power consumption becomes a constraint on iteration speed. Solving that constraint is how you maintain competitive velocity.

Estimated data shows that using Dojo can potentially increase training speed by a factor of 10, accelerating FSD model improvements significantly.

What FSD Really Needs: More Than Just More Data

One common misconception: autonomous driving comes down to training larger models on more data. Scale them up and they'll work better.

That's partially true but incomplete. Scale helps, but it's not sufficient.

FSD's current limitations include: (1) handling edge cases that don't occur frequently in training data, (2) reasoning about causality and counterfactuals (what would happen if a pedestrian moved left), (3) safe uncertainty handling (knowing when to be conservative versus aggressive), and (4) performance in conditions different from training data (snow, heavy rain, new cities).

Scaling up training data helps with some of these. More examples of rare edge cases means the model sees them and learns patterns. But it doesn't fully solve generalization problems. Models often perform worse in new environments than in training environments, especially for safety-critical applications.

This is where Dojo's real value becomes apparent. It's not just about processing more data. It's about the ability to run more experiments: testing different architectures, different loss functions, different data augmentation strategies. It's about the ability to quickly iterate when field data suggests the model is failing in specific ways.

FSD probably also needs different training approaches than just scaled-up supervised learning. Reinforcement learning (learning from rewards) might play a bigger role than current versions use. Simulation could become important (training on synthetic data to fill gaps in real training data). Dojo infrastructure that's flexible enough to support multiple training paradigms is more valuable than narrow optimization for one approach.

Musk's framing of Dojo as crucial for FSD advancement is correct, but the mechanism is nuanced. It's not that more data magically solves everything. It's that better training infrastructure enables faster iteration on techniques and approaches. The company with better iteration velocity wins, assuming they're heading in reasonable technical directions.

The Broader Context: AI Infrastructure As Strategic Asset

Tesla's Dojo restart reflects a broader trend in AI: infrastructure becoming a competitive advantage as important as algorithms or data.

In the early days of AI, advantages came from algorithms (transformer architecture, attention mechanisms) and from data (larger datasets). But algorithmic innovation has somewhat plateaued—everyone now has access to the same public papers and can implement the same techniques. Data advantages are eroding as companies collect similar datasets.

Infrastructure advantages are harder to replicate. Building custom semiconductors takes years and billions of dollars. Building systems software and training pipelines optimized for specific workloads takes time and expertise. Deploying and managing large distributed training systems at scale is non-trivial.

This is why Google, Meta, and Open AI all invest heavily in infrastructure. It's why Nvidia dominates the GPU market—they have infrastructure advantages in manufacturing and software optimization. It's why companies that try to replicate AI systems without matching infrastructure often struggle, even with similar teams and algorithms.

Tesla's advantage isn't algorithmic brilliance. (FSD is good but not algorithmically groundbreaking.) It's not data superiority alone. (Competitors can also collect driving data.) It's the full-stack approach: custom chips for inference, now adding custom infrastructure for training, all tied to a specific product (autonomous vehicles) and a specific use case.

This full-stack strategy makes sense in an era where infrastructure increasingly matters. It also makes sense for autonomous driving specifically, where the problem is narrow enough that specialization pays off. Building a general-purpose supercomputer would be less valuable than building one optimized for video-to-driving-model training.

The risk: if you bet wrong on your specialization, you're stuck with expensive hardware that doesn't do what you need. This is the classic risk of vertical integration and custom hardware. But if you bet right, you gain advantages that competitors can't quickly match.

Realistic Timelines and Expectations

Based on Tesla's history and general industry experience with custom hardware projects, what's a reasonable timeline for Dojo 3?

If "restart" means "resume design and manufacturing of the next generation," you're probably looking at 2-3 years before Dojo 3 is operationalized at meaningful scale. That would put practical deployment in 2027-2028 timeframe. Custom chip projects typically take 2-3 years from restart to production deployment, especially if you're doing significant architectural changes from Dojo 2.

The space-based computing angle is almost certainly longer-term, probably in the 5-10 year timeline at best, if it happens at all. The engineering challenges are real, and commercial viability hasn't been proven.

Will Dojo 3 be as transformative as Musk implies? Probably partially. It will improve training velocity, which will accelerate FSD development. But it's not a silver bullet. FSD's limitations include algorithmic challenges, not just computation speed. Better hardware helps, but it's not enough by itself.

Should you believe the Dojo announcement? Yes, in the sense that it's a real restart of a real project. No, in the sense that timelines will probably slip and scope will probably change. The announcement is valuable as a signal of strategic commitment, but not as a precise technical forecast.

The Dojo project's progress was slower than anticipated due to thermal challenges, software optimization delays, and integration complexities. Estimated data reflects typical development hurdles.

The Competition: How Other Companies Are Approaching Training Scale

Tesla isn't the only company thinking about training infrastructure challenges. The competitive landscape tells us something about where the industry believes advantages will be found.

Waymo (Alphabet subsidiary) has access to Google's TPU infrastructure and can presumably run training at massive scale using Google Cloud resources. That's a strength—they can scale instantly without building hardware. But it's also a limitation—they're dependent on Google's roadmap and optimization priorities, which might not match Waymo's specific needs.

Hydron and other autonomous driving startups typically use cloud providers (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure) for training. This gives them flexibility and eliminates capital expenditure but means they're limited to whatever hardware cloud providers offer. The latest GPUs are available, but so is everyone else's training.

Bosch and other tier-1 automotive suppliers are more likely to build partnerships with cloud providers than custom infrastructure, reflecting a different strategic bet: flexibility and speed to market over long-term efficiency.

Chinese autonomous driving companies like Baidu, Xiaomi's autonomous vehicle unit, and others have likely pursued custom infrastructure strategies similar to Tesla, recognizing that training throughput is a constraint on improvement velocity.

The pattern suggests the industry is splitting: large tech companies (Google, Meta, potentially Open AI) building custom infrastructure because they can afford it and have the expertise. Car companies building custom infrastructure when they have the resources (Tesla) or outsourcing to cloud providers. Startups mostly outsourcing unless they've raised enough capital to fund custom hardware.

Tesla's Dojo restart positions them as betting that custom infrastructure is worth the investment. The question is whether they're right.

Potential Failure Modes and What Could Go Wrong

Custom hardware projects have a graveyard of failures. What could go wrong with Dojo 3?

Silicon yields: Manufacturing custom chips is probabilistic. Not every chip produced works perfectly. Yield rates matter enormously. If Dojo 3 chips have 70% yield rates instead of 90%, you're wasting 30% of manufacturing capacity. This adds cost and delays scale-up.

Thermal management: More power-dense chips generate more heat. Cooling becomes harder at higher densities. If Dojo 3 has thermal issues, you're stuck with expensive cooling systems or lower clock speeds that hurt performance.

Software optimization: Writing software optimized for custom hardware is hard. If Tesla's software engineers can't fully optimize for Dojo 3, the hardware advantage diminishes. Compilers, libraries, and optimization techniques all take time to mature.

Market changes: What if FSD's path forward is fundamentally different than expected? What if reinforcement learning, simulation, or other techniques become more important than supervised training on video data? Dojo optimized for one approach is suddenly less valuable.

Timeline slippage: Every complex hardware project slips. Design issues discovered late, manufacturing delays, software bugs that require silicon fixes. 2-3 year timelines regularly become 3-4 years.

Scaling challenges: Running one exaflop of computation is different from running ten. Reliability, synchronization, debugging—all become harder at scale. Dojo 3 might work great in small deployments and struggle when scaled.

Power supply constraints: Even if Dojo 3 is efficient, it needs power infrastructure. If Tesla can't get sufficient power supply to their data center location, they're stuck. This is an underestimated risk.

Any of these problems could derail the project or significantly delay deployment. This is why custom hardware is risky—you're betting billions on execution across multiple disciplines.

Why This Matters: The Self-Driving Competitive Timeline

The broader context here is crucial: autonomous driving is becoming a real product category, not just a research project.

Waymo has robotaxis deployed in several cities. They're operating them commercially, carrying paying customers, and expanding. Cruise's recent setbacks are a setback, but the space is active.

Tesla's FSD is available to customers but still in beta and still requires monitoring. The gap between "available but monitored" and "fully autonomous" matters less than most people think for competitive positioning. Waymo has the latter. Tesla doesn't. Yet.

The race is partly about technical capability, but it's also about iteration speed. Whoever can improve their autonomous driving system fastest has a structural advantage. Each improvement cycle makes the system safer, which enables expansion to more cities and more use cases. Faster iteration means faster expansion.

Dojo is Tesla's bet on iteration speed. By providing better training infrastructure, it should enable faster model updates, faster testing of new approaches, and faster deployment of improvements. Over a 3-5 year timeframe, faster iteration compounds into significant capability advantages.

This is why the Dojo restart matters beyond just "Tesla is building a supercomputer." It's about the company's belief that it can still win the autonomous driving race by iterating faster. That belief depends on training infrastructure being a bottleneck worth removing.

Dojo hardware is estimated to consume 200 watts less than standard GPUs, offering better efficiency per watt and easing scaling constraints. (Estimated data)

The Regulatory and Safety Implications

There's a safety aspect to training infrastructure that often gets overlooked. Better training typically means safer systems.

If Dojo allows Tesla to train models on more diverse data, test more architectural variations, and deploy more frequent updates, the statistical expectation is that FSD becomes safer. This assumes the training is doing what it's supposed to—learning correct patterns, not reinforcing bad ones.

But there's also a risk: faster iteration can sometimes bypass careful safety validation. If Tesla is updating FSD more frequently, are they running adequate safety checks on each update? Are they testing in simulation and controlled environments before deploying to customers? Or is the iteration speed sacrificing some safety rigor?

Historically, Tesla's approach has been more "deploy and monitor" than "carefully validate before deployment," which has created friction with regulators. Faster training infrastructure might exacerbate this tendency or might force Tesla to build better safety validation processes to match iteration speed.

Regulators will be watching. NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) has already opened investigations into Tesla's driver assistance features. If FSD is updating frequently and causing accidents, regulatory pressure would increase. Tesla probably understands this and is building safety processes into the training infrastructure.

The ideal outcome: better training infrastructure enables both faster iteration and better safety validation, with each driving the other. Faster iteration on safety improvements, more comprehensive testing of each update before deployment, and continuous learning from real-world performance data.

Lessons From Previous Infrastructure Bets

Tesla's Dojo restart isn't the company's first bet on vertical integration and custom infrastructure. Looking at other bets provides perspective.

Battery manufacturing: Tesla's gigafactories are pursuing vertical integration in battery production. The bet has mostly paid off—Tesla achieved better battery production costs and control over supply chain. But it took longer than anticipated and required continuous innovation in the manufacturing process.

Motor design: Tesla designed its own electric motors rather than relying on suppliers. This gave them efficiency advantages and lower costs. But it required ongoing R&D and manufacturing expertise. The payoff was real but came with complexity.

Chip design for vehicles: The current work on AI5 and AI6 chips is custom chip development. This is harder than battery or motor work because semiconductors are more foundational and require deeper expertise. But if executed well, the efficiency advantages are larger.

The pattern: Tesla's vertical integration bets often deliver value, but they take longer and require more expertise than expected. They work best when there's a clear competitive advantage from custom optimization, not when they're just copying existing designs or avoiding a supplier.

Dojo fits this pattern. If the supercomputer is actually optimized for Tesla's specific problem and delivers efficiency advantages, it's a good bet. If it's just custom hardware for its own sake, it's wasteful.

Based on Tesla's history, I'd estimate 60% chance Dojo delivers meaningful competitive advantage, 40% chance it becomes a resource sink with diminishing returns. That's not a prediction so much as calibration of uncertainty based on execution history.

What Actually Needs to Happen for Dojo Success

For Dojo 3 to be a meaningful competitive advantage, several things need to work out:

-

Chip design has to be right: The architecture needs to match FSD training workloads. If you optimize for the wrong thing, all the custom hardware in the world won't help.

-

Software stack has to mature: Compilers, libraries, and optimization tools need to make it easy for engineers to write efficient code for Dojo. If software engineers have to write low-level optimizations for every task, productivity suffers.

-

Manufacturing has to scale: Going from prototype to manufacturing thousands of chips requires solving yield, thermal management, and power supply problems. This is harder than the engineering.

-

Integration with training pipelines has to work: Dojo doesn't exist in isolation. It needs to integrate with data pipeline infrastructure, model serving infrastructure, and monitoring systems. The full stack needs to work.

-

Tesla needs to use it effectively: Having powerful hardware is worthless if you don't know how to apply it to your problem. Tesla's ML teams need to use the hardware to improve FSD, not just to say they have a supercomputer.

-

Timing needs to work out: Dojo 3 needs to be ready when FSD is ready for the next phase of training approaches. If there's a several-year gap between hardware readiness and training methodology maturity, one becomes useless waiting for the other.

All of these need to succeed. Failure on any one of them degrades the whole project. That's why custom hardware is risky—the failure modes are numerous and the dependency chains are complex.

The Bigger Picture: AI Infrastructure Wars

Tesla's Dojo restart is part of a larger trend: AI infrastructure becoming a strategic battleground.

We're moving from an era where algorithmic innovation and data accumulation were the primary competitive moats to an era where infrastructure—the ability to run massive amounts of computation efficiently—is becoming equally important.

Google recognized this and built TPUs. Meta recognized this and built custom accelerators. Open AI built partnerships with Microsoft for infrastructure access. The pattern is clear: large-scale AI requires custom infrastructure.

Tesla's insight is that this is especially true for domain-specific applications like autonomous driving. General-purpose infrastructure is good, but specialized infrastructure optimized for your specific problem is better.

This creates an interesting market dynamic. Companies with capital and expertise can build infrastructure advantages that smaller competitors can't match. This favors incumbents and large players. It's a barrier to entry for startups, which is probably why many autonomous driving startups have either pivoted, merged, or shut down—they can't compete on infrastructure investment against well-funded incumbents.

From a competitive perspective, Dojo is Tesla's bet that vertical integration in infrastructure will be the differentiator that matters most in autonomous driving over the next 5-10 years. Whether that's right depends on whether training speed is actually the bottleneck holding back FSD improvements, which depends on whether the fundamental problem with FSD is capability or deployment.

If the problem is "the current AI5 chips aren't fast enough for training," then Dojo is a smart investment. If the problem is "we don't know the right training approach for the remaining problems," then Dojo is a misalignment of resources—the problem isn't compute speed, it's algorithmic understanding.

Based on FSD's current behavior (it handles most common situations well, struggles with edge cases and unusual situations), I suspect the real problem is partially both: you need compute power to experiment with new approaches, but you also need those approaches to exist.

Dojo addresses the compute part. Tesla still needs to solve the algorithmic part. The restart announcement suggests confidence that both pieces are addressable with more resources focused on training infrastructure.

FAQ

What is Dojo and why is Tesla restarting it?

Dojo is Tesla's in-house supercomputer project designed to process massive amounts of video data from Tesla vehicles and train Full Self-Driving models. Tesla paused the project in 2024 to focus resources on the AI5 and AI6 inference chips, but is restarting it because those chips have proven to be insufficient for the training workloads Tesla needs to accelerate FSD development. The restart signals that Tesla believes dedicated training infrastructure is worth the investment in resources and capital.

How does Dojo help Full Self-Driving improve?

Dojo processes raw video footage from millions of Tesla vehicles, extracts useful training examples, labels them with ground truth about what actually happened, and feeds them into training runs that update FSD's neural networks. Better training infrastructure means faster data processing, faster model training, and faster iteration cycles. Faster iteration means the company can test new approaches more frequently and deploy improvements more quickly than competitors who lack dedicated training infrastructure.

Why is custom hardware better than cloud infrastructure for training?

Custom hardware can be optimized for your specific workload in ways that general-purpose cloud infrastructure cannot. A supercomputer designed specifically for video-to-driving-model training can achieve better performance per watt and better performance per dollar than generic GPUs or cloud services. The tradeoff is that custom hardware is expensive and risky to build—you're betting billions on execution in chip design, manufacturing, and software optimization.

What is space-based AI compute and is it realistic?

Space-based AI compute refers to data centers in orbit where they can access continuous solar power and radiate heat directly into space's cold vacuum, avoiding the cooling challenges of Earth-based data centers. It's theoretically interesting but practically speculative. Launch costs, latency between orbit and ground, reliability of remote systems, and regulatory uncertainty all create obstacles to commercial viability. While Musk mentioned it as part of Dojo 3's longer-term vision, the near-term project is almost certainly Earth-based.

How does Dojo compare to what competitors like Waymo use?

Waymo, owned by Alphabet, has access to Google's infrastructure including custom TPUs (Tensor Processing Units) and can run training at massive scale through Google Cloud. They don't need to build their own supercomputers. However, their infrastructure is optimized for Google's general AI problems, not specifically for autonomous driving. Tesla's approach of building specialized infrastructure for its specific problem could provide efficiency advantages if executed well. The tradeoff is Tesla takes on all the risk and capital investment.

What's the realistic timeline for Dojo 3 deployment?

Based on typical custom chip project timelines and Tesla's history, Dojo 3 will probably take 2-3 years to progress from restart to operational deployment at meaningful scale. That would suggest a 2027-2028 timeframe for meaningful production deployment. All timelines should be treated as uncertain—hardware projects almost always slip. The space-based computing aspect mentioned in Musk's announcement is even longer-term, likely 5-10 years at best if it happens at all.

Why does training infrastructure matter more now than it did before?

As AI models become larger and datasets grow, power consumption becomes the limiting factor in how much training you can run. Traditional data centers are constrained by geographic access to power, by cooling challenges, and by the available hardware from suppliers like Nvidia. Building specialized infrastructure lets you work around some of these constraints. Additionally, training speed determines iteration speed—how fast you can test new ideas. In competitive domains like autonomous driving, faster iteration compounds into significant advantages over time.

Could Dojo become a liability instead of an asset?

Yes. If the technical approach is wrong (chip design doesn't match actual needs), if manufacturing struggles with yields or thermal management, if software optimization proves more difficult than expected, or if FSD's real limiting factor isn't training speed, then Dojo could become a resource sink. Custom hardware is high-risk, high-reward. Successful execution provides competitive advantage. Failed execution wastes billions. Tesla's execution history is mixed—many successes but also significant delays and scope changes.

How important is Dojo for Tesla's autonomous driving strategy?

Dojo appears central to Tesla's long-term autonomous driving ambitions. The company is betting that training throughput is a key bottleneck for FSD improvement and that removing that bottleneck with dedicated infrastructure is worth billions in investment. If that bet is correct, Dojo becomes crucial. If training isn't the bottleneck (algorithmic innovation or data quality might matter more), then Dojo is less critical. The restart announcement signals high confidence in that bet.

What happens if Dojo fails or significantly delays?

Tesla would continue using AI5 and cloud infrastructure for training, progressing more slowly on FSD improvements than the company likely believes is optimal. Competitors with better training infrastructure or faster iteration could pull ahead in autonomous driving capability. However, FSD is already functional and improving. Slower iteration wouldn't be catastrophic, just suboptimal. The real risk is competitive positioning over a 3-5 year timeframe.

Conclusion: Vision Versus Reality

Elon Musk's announcement that Tesla is restarting Dojo is significant but should be taken with appropriate skepticism about timelines and assumptions.

Significant because: It signals that Tesla believes training infrastructure is a competitive advantage worth billions in investment. It reflects learning from a year of using AI5 chips for training and discovering limitations. It positions Tesla to iterate faster on FSD if execution goes well. It demonstrates confidence in the autonomous driving business as a long-term priority.

Skeptical because: Tesla's track record on timelines is poor. Custom hardware projects are complex and risky. The announcement includes speculative elements (space-based computing) that probably won't happen on stated timelines. The fundamental assumption that training speed is the bottleneck holding back FSD improvements hasn't been proven.

The realistic view: Dojo is probably restarting and probably will eventually provide benefits to Tesla's FSD training. But it will almost certainly take longer than implied, probably slip on timelines, and may face technical challenges in manufacturing or software optimization. Whether it provides decisive competitive advantage depends on whether the company can execute across multiple disciplines and whether training speed is actually the critical constraint on FSD improvement.

What should you take away? Tesla is serious about autonomous driving as a long-term business. The company believes infrastructure matters. But announcements should be discounted for typical delays and the gap between vision and execution. The real measure of success will be FSD improvement speed over the next 2-3 years—does having better training infrastructure actually translate to faster capability improvements? That's the test that matters.

For now, Dojo is ambitious. Ambition is good. Execution is what matters.

Key Takeaways

- Tesla is restarting Dojo supercomputer development to accelerate Full Self-Driving training after AI5 chips proved insufficient for training workloads

- Custom hardware optimized for specific problems can achieve better efficiency than general-purpose cloud infrastructure, but comes with high execution risk and capital investment

- Training speed determines autonomous driving iteration velocity: companies that train models faster can test ideas more frequently and improve capabilities faster than competitors

- Space-based AI compute mentioned in Musk's announcement is speculative and likely 5-10+ years away, if viable at all; near-term Dojo3 will be Earth-based

- Tesla's track record on custom hardware projects shows success but with significant timeline slips, making 2-3 year Dojo timelines subject to skepticism

Related Articles

- Jensen Huang's Reality Check on AI: Why Practical Progress Matters More Than God AI Fears [2025]

- Google Gemini vs OpenAI: Who's Winning the AI Race in 2025?

- Apple & Google AI Partnership: Why This Changes Everything [2025]

- Hyundai's Autonomous Robotaxi: Las Vegas Launch & Future of Self-Driving

- Thinking Machines Cofounder: Workplace Misconduct & AI Exodus

- From AI Hype to Real ROI: Enterprise Implementation Guide [2025]

![Tesla's Dojo Supercomputer Restart: What Musk's AI Vision Really Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tesla-s-dojo-supercomputer-restart-what-musk-s-ai-vision-rea/image-1-1768846075658.jpg)