The Quiet Shift That Could Reshape Air Pollution Policy

Imagine being asked to justify buying a fire extinguisher by comparing its cost to the value of preventing a house fire—except someone tells you that you're not allowed to count the house as part of the equation. That's essentially what's happening with how the EPA now approaches air pollution regulations.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently made a significant methodological shift in how it conducts cost-benefit analyses for air pollution regulations. Instead of weighing the costs of pollution control measures against the estimated health benefits of cleaner air, the EPA is now presenting only the costs in quantified form while describing health improvements qualitatively. This change affects regulations for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ground-level ozone—two of the most pervasive air pollutants affecting millions of Americans.

On the surface, this sounds like a technical accounting adjustment. But this decision represents a fundamental reshaping of how environmental policy gets made in the United States. For decades, cost-benefit analysis has been the backbone of EPA rulemaking. It's how regulators justify spending billions on pollution controls by showing that the health benefits outweigh the economic costs. Remove the benefits from the equation, and the justification crumbles.

The EPA's justification hinges on claims about scientific uncertainty. According to internal documents and the agency's recent regulatory impact analysis for stationary combustion turbines, the EPA states that previous analyses "lead the public to believe the Agency has a better understanding of the monetized impacts of exposure to PM2.5 and ozone than in reality." In other words, the agency argues that because estimating health benefits involves uncertainties, those estimates shouldn't be included at all.

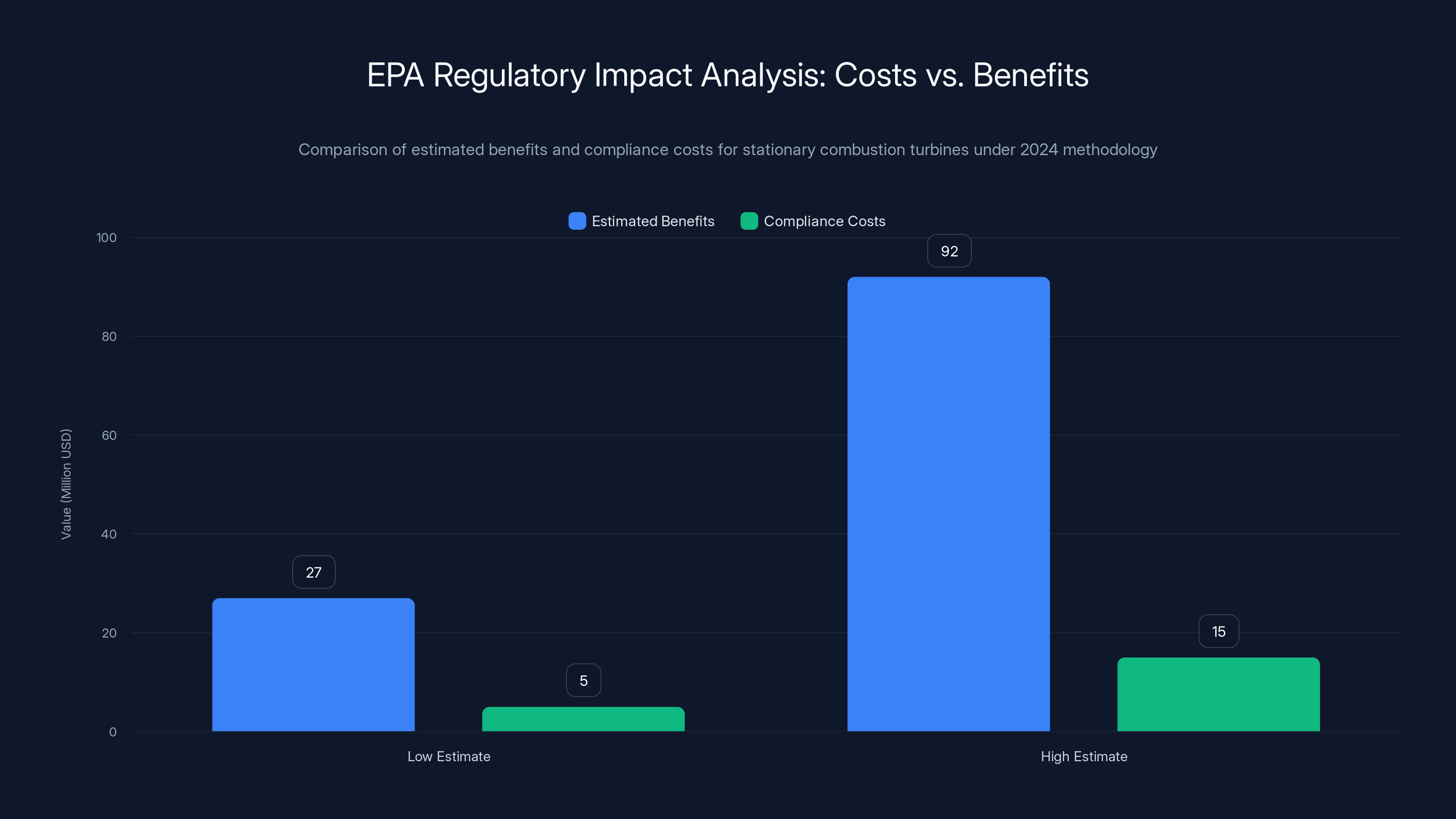

Here's what makes this particularly consequential: a 2024 EPA analysis estimated health benefits from tightening emissions standards for combustion turbines at

This shift didn't happen in a vacuum. It reflects a broader political and philosophical debate about how much weight uncertainty should carry in regulatory decision-making. And it raises uncomfortable questions about whether scientific skepticism is being weaponized to justify deregulation.

The History of Cost-Benefit Analysis in Environmental Regulation

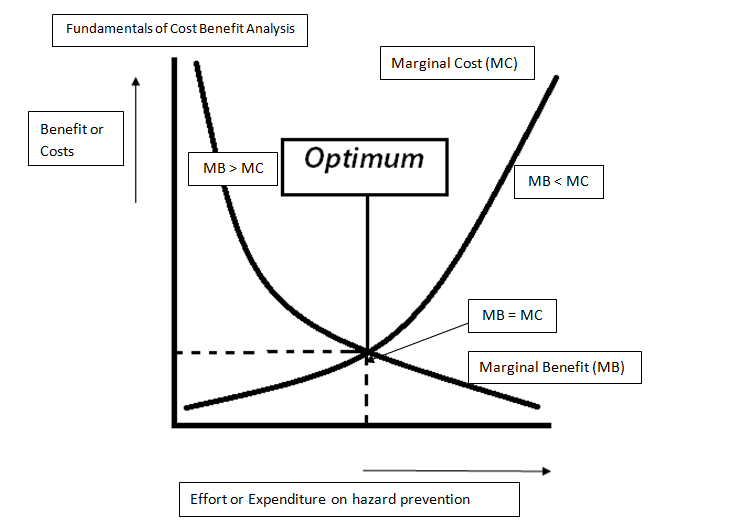

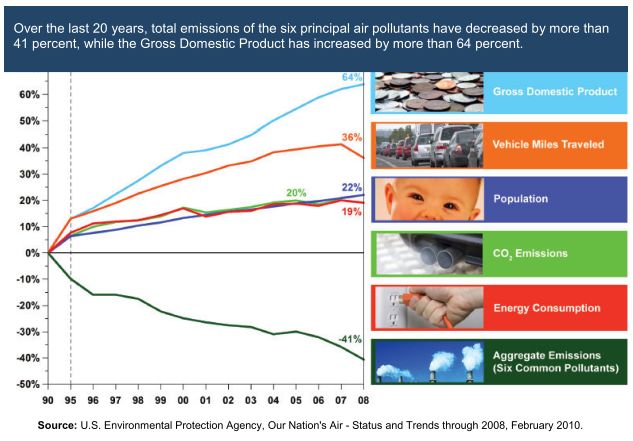

Cost-benefit analysis became central to EPA rulemaking gradually, not by explicit statute but through executive orders and accumulated practice. The concept is straightforward: before implementing a regulation, calculate what it costs industry to comply, then estimate what the public gains from the improvement. If benefits exceed costs, it's economically rational to proceed.

This approach emerged from economic thinking that gained prominence in the 1970s and 1980s. The logic appealed to both regulators and economists. It provided a seemingly objective framework for making policy decisions and offered a way to compare disparate values—the cost of installing scrubbers on power plant smokestacks against the value of reduced childhood asthma.

The EPA has been conducting these analyses for major air quality regulations since at least the 1990s. The agency developed sophisticated methodologies for estimating the economic value of health improvements. These methodologies are neither simple nor arbitrary. They're based on scientific research, peer review, and transparent documentation.

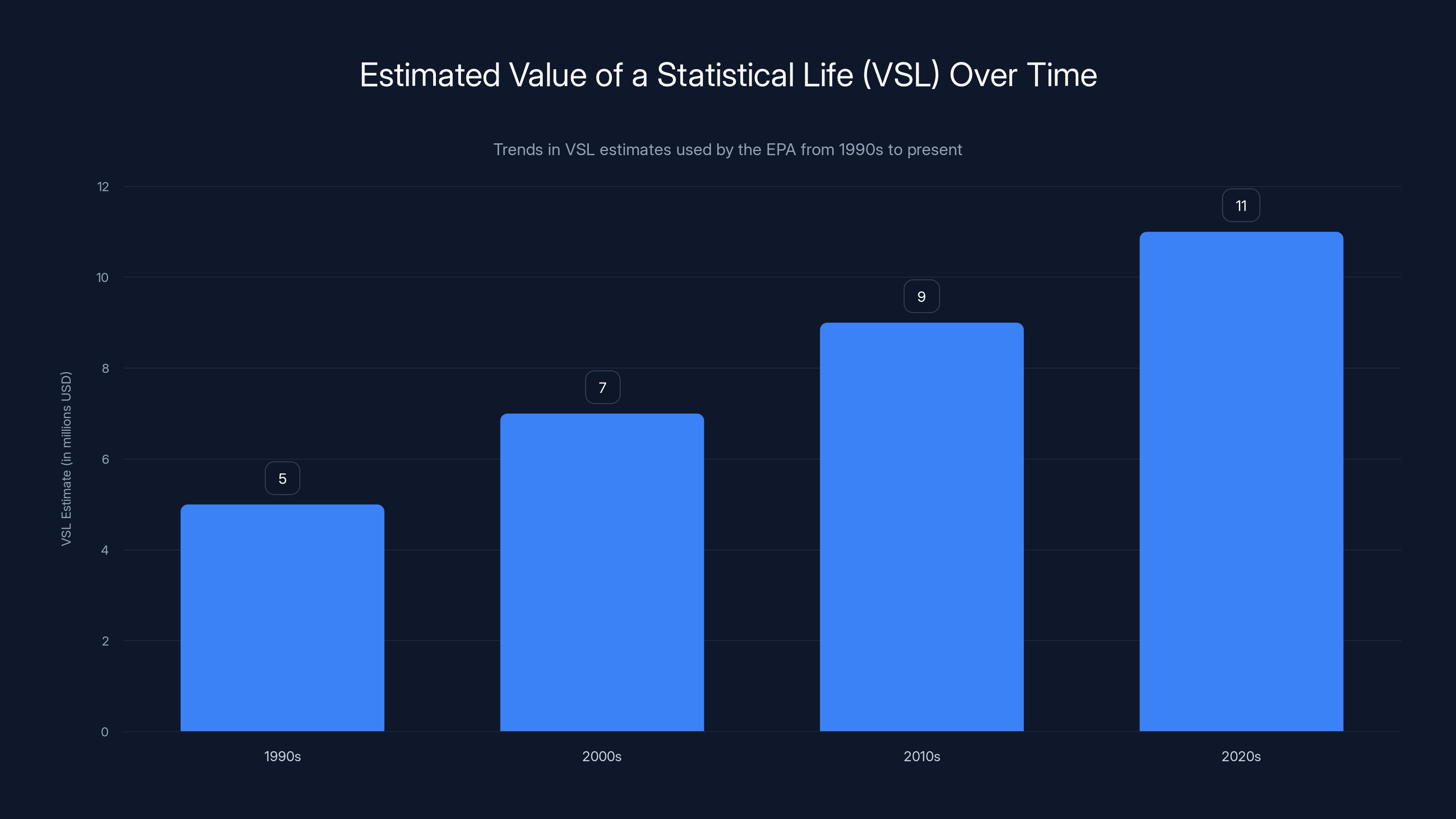

One key component is the "value of a statistical life" (VSL). This number attempts to quantify what people are willing to pay for small reductions in their risk of death from environmental causes. It's not about pricing human life in some crude sense, but rather about understanding revealed preferences—how much people actually spend to reduce their risks through behavior like buying air filters, moving to cleaner areas, or accepting lower wages for safer jobs.

The EPA's estimates for VSL have ranged from roughly

These numbers aren't pulled from thin air. They're derived from decades of epidemiological research showing the health effects of air pollution. Scientists have documented how fine particles penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream, triggering inflammation and affecting cardiovascular function. That's not uncertain—it's well-established science published in thousands of peer-reviewed papers.

What is uncertain, in a more nuanced sense, is the precise quantification of economic value. How much is avoiding one case of respiratory hospitalization worth? Different methodologies can produce different dollar estimates. This variation is what the EPA is now pointing to as justification for excluding benefits entirely.

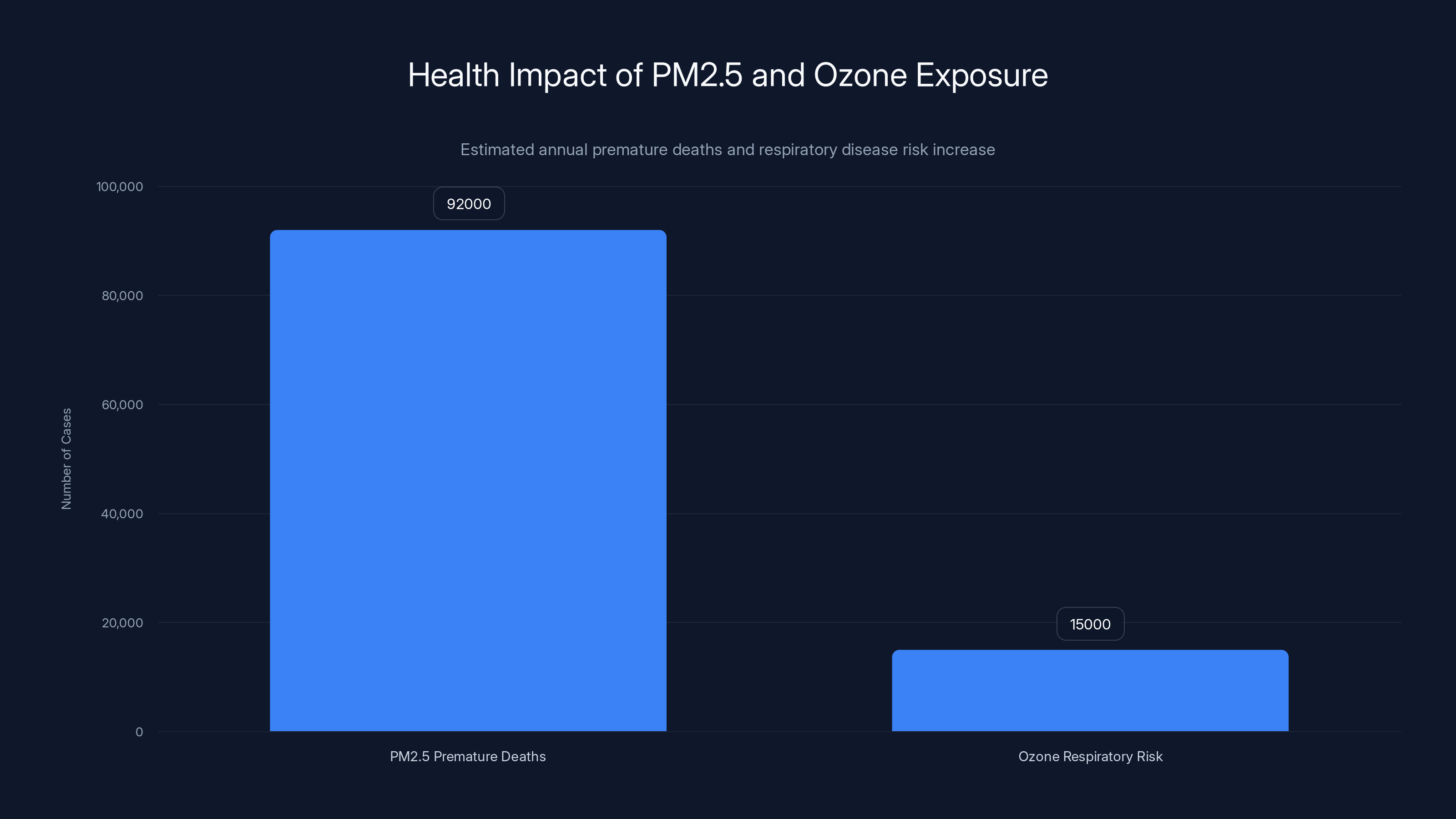

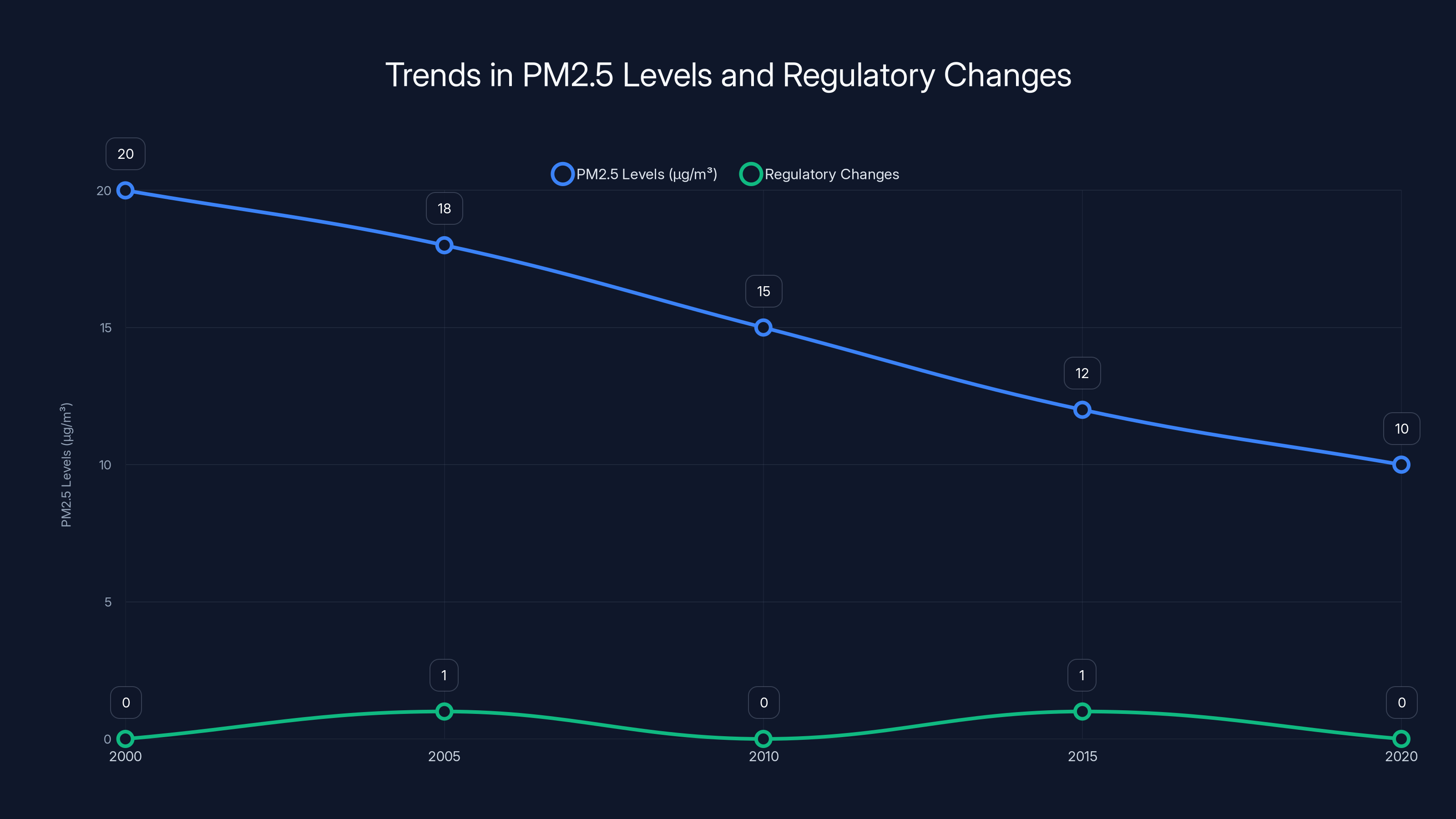

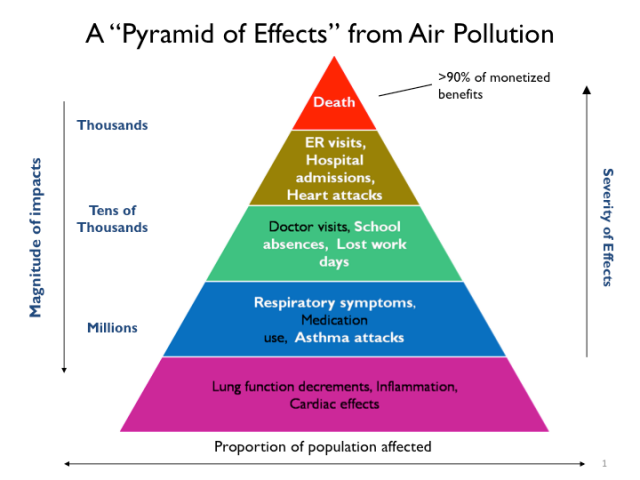

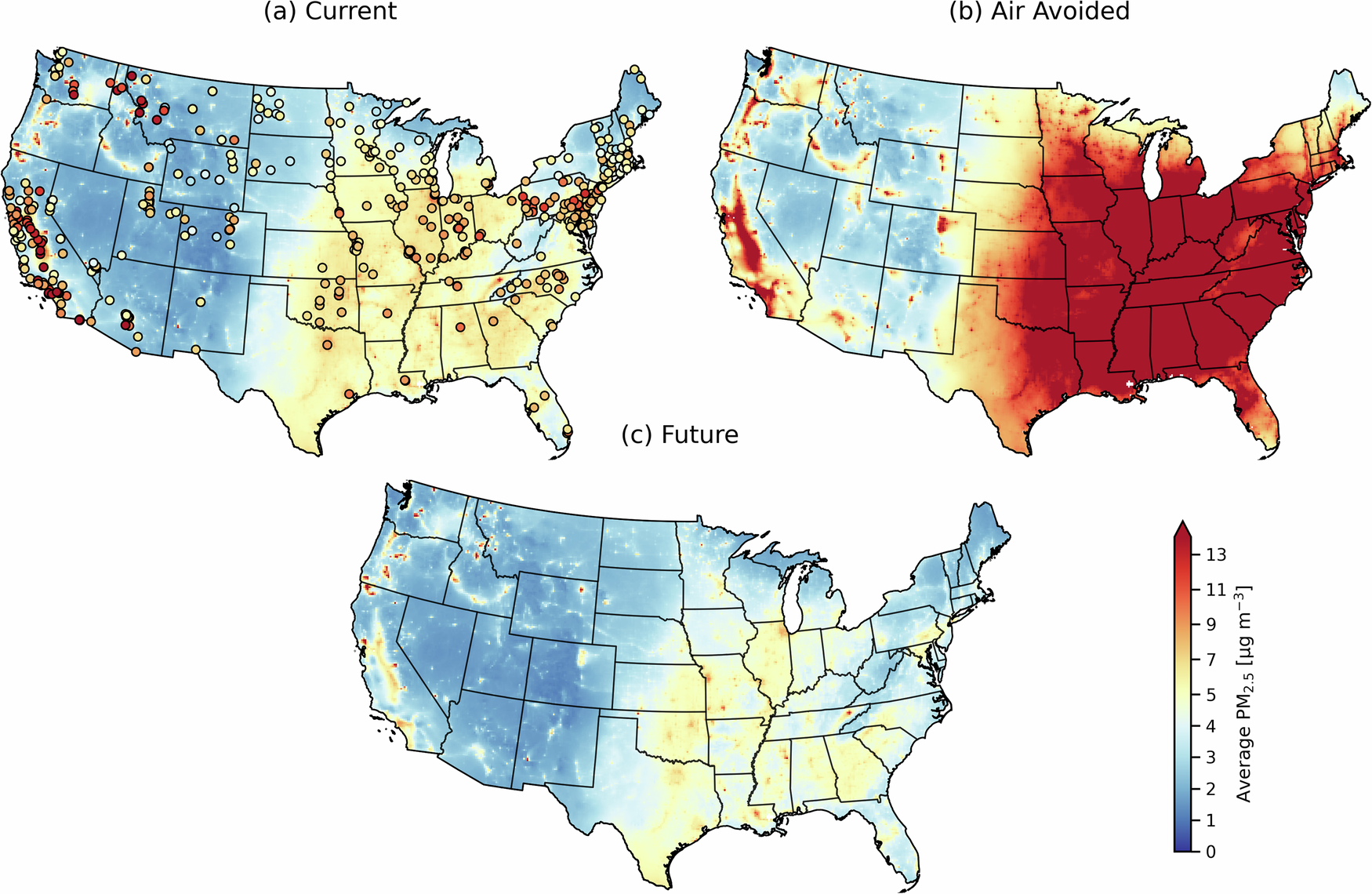

PM2.5 exposure is linked to approximately 92,000 premature deaths annually, while ozone exposure significantly increases respiratory disease risk. Estimated data for ozone impact.

How PM2.5 and Ozone Became Regulatory Flashpoints

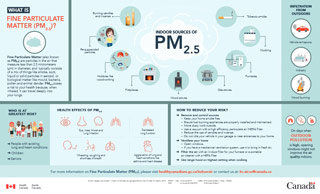

Fine particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers—abbreviated as PM2.5—represents one of the most significant air quality challenges in the United States. This pollutant is small enough to bypass the respiratory system's natural defenses and deposit directly in the alveoli, the gas exchange sacs deep in the lungs. From there, particles can cross into the bloodstream.

PM2.5 comes from multiple sources: vehicle exhaust, power plant emissions, industrial processes, wildfires, and residential wood burning. It's particularly prevalent in urban areas and downwind from industrial centers. Unlike some air pollutants that cause acute, obvious symptoms, PM2.5 health effects are cumulative and often delayed. People don't necessarily feel sick when exposed; the damage accumulates silently.

The health literature on PM2.5 is substantial and fairly consistent. Exposure increases risk of cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and premature mortality. The American Heart Association and American Lung Association have both issued statements affirming this evidence. Large prospective studies following millions of people have documented these associations. When air quality improves—such as in China after implementing pollution controls or in the United States after the Clean Air Act—health outcomes improve correspondingly.

The EPA's National Ambient Air Quality Standards for PM2.5 were last tightened in 2012, lowering the annual average standard from 15 micrograms per cubic meter to 12 micrograms. This change was based on extensive review of health evidence. The agency estimated that tightening this standard would prevent tens of thousands of premature deaths annually once fully implemented.

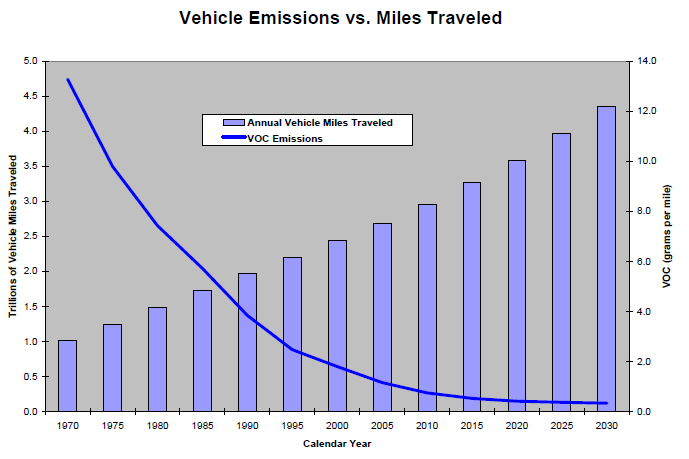

Ground-level ozone presents a different but equally significant challenge. Unlike stratospheric ozone, which protects us from ultraviolet radiation, tropospheric ozone is a secondary pollutant formed when sunlight triggers reactions between nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds. These precursors come from vehicle emissions, power plants, and industrial sources.

Ozone is a powerful oxidant that inflames the respiratory tract. Exposure causes airway constriction, reduces lung function, and triggers asthma attacks. People exercising outdoors on high ozone days often experience chest pain and coughing. Chronic exposure contributes to the development of respiratory disease.

Both PM2.5 and ozone have become targets for regulatory skepticism, particularly from industry groups and political advocates opposed to environmental regulation. The argument typically follows this pattern: these health effects are small at the margins, the evidence is uncertain, and the costs of regulation are large and certain. Why impose expensive controls for speculative health benefits?

This skepticism has intensified in recent years. Anti-regulation advocates have specifically targeted the epidemiological research on PM2.5, suggesting that scientists exaggerate health risks or that associations observed in studies don't prove causation. These arguments echo longstanding debates about the weight of observational evidence versus experimental evidence—debates that stretch back to tobacco industry disputes about smoking health effects.

The estimated value of a statistical life (VSL) has increased from

The New EPA Approach: Dropping Numbers, Keeping Uncertainty

The EPA's announcement that it will no longer monetize benefits from PM2.5 and ozone regulations marks a departure from decades of practice. The agency's justification, articulated in the 2025 regulatory impact analysis for stationary combustion turbines, centers on claims that previous monetization approaches misrepresented scientific confidence.

According to the EPA's new language, the previous approach of quantifying benefits alongside costs "lead[s] the public to believe the Agency has a better understanding of the monetized impacts of exposure to PM2.5 and ozone than in reality." The agency further states: "Therefore, to rectify this error, the EPA is no longer monetizing benefits from PM2.5 and ozone but will continue to quantify the emissions until the Agency is confident enough in the modeling to properly monetize those impacts."

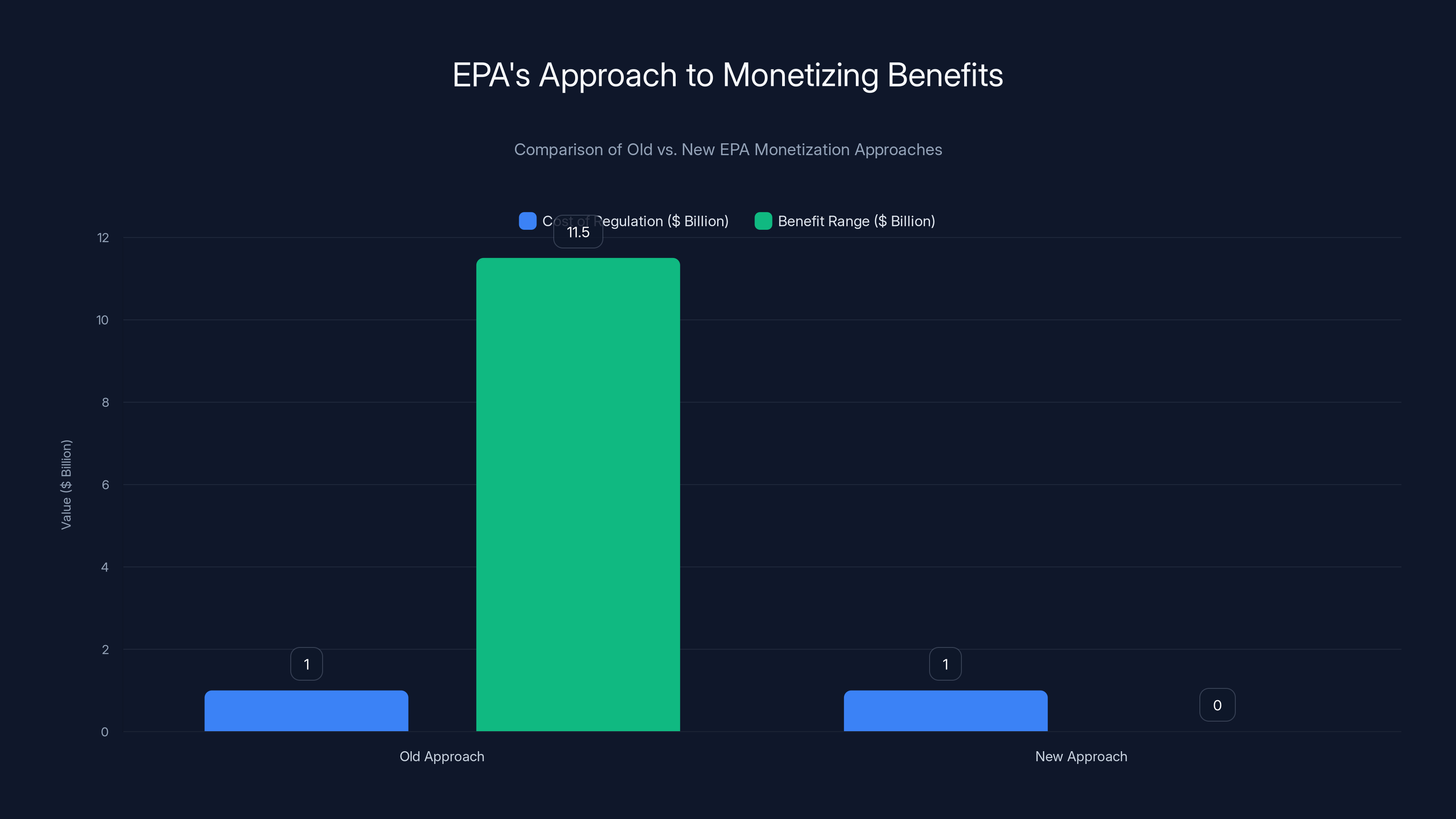

On its face, this language suggests scientific caution. If estimates vary or involve uncertainty, shouldn't we be transparent about that uncertainty rather than presenting a single number? The problem is that the solution—excluding quantified benefits entirely while keeping quantified costs—isn't transparent. It's selective.

Consider a hypothetical scenario. A regulation costs

Which presentation better reflects scientific uncertainty? The first approach explicitly quantifies the uncertainty (an $8–15 billion range). The second approach simply omits the uncertain quantity. This isn't reducing misleading precision; it's eliminating comparison entirely.

The EPA could have taken other approaches to address legitimate concerns about certainty. The agency could have widened confidence intervals to better reflect uncertainty. It could have presented multiple scenarios with different assumptions. It could have conducted sensitivity analyses showing how conclusions change if key assumptions shift. None of these approaches are new—they're standard practice in scientific and economic analysis.

Instead, the EPA chose to remove quantified benefits from regulatory impact analyses for these specific pollutants. The practical effect is to make regulations look less attractive by comparing large certain costs against vague uncertain benefits. Once benefits disappear from the numerical analysis, they're easily forgotten in policy debates focused on the bottom line: How much will this regulation cost?

The Historical Pattern of Manipulating Uncertainty

This isn't the EPA's first venture into using scientific uncertainty as a policy tool. During the Bush administration, debates about health benefits of environmental regulations took a different but related form.

Between 2004 and 2008, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which oversees EPA regulations, pursued a policy of reducing the EPA's value of a statistical life estimates. The previous approach had valued a statistical life at approximately

The justification involved a particular interpretation of economic research and uncertainty. By selecting the lower end of defensible estimates, the Bush administration made health benefits appear smaller, making regulations look less cost-effective. The policy was defended as selecting more conservative estimates, but critics noted it was conservative in only one direction—toward lower health valuations.

Once the Obama administration took office, these values were adjusted back upward to better reflect the full range of economic research. This whipsaw effect—where values move up and down based on which administration prefers more or less regulation—illustrates how supposedly technical economic choices carry profound policy implications.

The Trump administration's approach to PM2.5 and ozone benefits represents an even more aggressive weaponization of uncertainty. Rather than adjusting values within a defensible range, the agency is simply removing the category from analysis. This transcends normal policy disagreements about appropriate discount rates or valuation methods.

The pattern suggests something important: when scientific uncertainty becomes a tool in political battles, the direction of bias rarely falls randomly. The beneficiaries of deregulation push for approaches that eliminate or minimize benefits. Those bearing health risks push back. Uncertainty becomes not a neutral constraint but a resource deployed strategically.

Estimated benefits from reduced emissions (

The Science Behind Health Benefits: What We Actually Know

Understanding whether the EPA's claim about uncertainty is justified requires examining what the science actually shows about PM2.5 and ozone health effects.

For PM2.5, the epidemiological evidence is remarkably consistent across multiple study designs and populations. Large prospective cohort studies—which follow millions of people and track their exposure and health outcomes—consistently show associations between PM2.5 exposure and increased mortality risk. The Harvard Six Cities Study, initiated in 1974, provided seminal evidence that people living in cities with worse air quality had higher mortality rates even after controlling for smoking and other risk factors. Subsequent large studies in Europe, Asia, and across North America have replicated these findings.

What about the mechanistic pathway? PM2.5 research has traced how these particles enter the body. Ultrafine particles can cross into the bloodstream from the lungs, triggering systemic inflammation. Inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 increase with PM2.5 exposure. This inflammation affects cardiovascular function, increases blood clotting risk, and triggers cardiac arrhythmias. These mechanisms aren't speculative; they've been documented in controlled human exposure studies.

The cardiovascular effects are particularly well-established. Epidemiological studies show that PM2.5 exposure increases risks for heart attack, stroke, arrhythmias, and heart failure. The associations persist across diverse populations and study designs. Meta-analyses synthesizing hundreds of studies show consistent dose-response relationships—more pollution exposure corresponds to greater health risk.

For ozone, the evidence of respiratory effects is even more direct. Ozone is a known oxidant that damages respiratory epithelium. Controlled exposure studies show that breathing ozone at concentrations legally allowed under current air quality standards causes measurable reductions in lung function, even in healthy young adults. People with asthma experience more severe responses. The effects occur at exposures well within EPA's current standards.

Long-term epidemiological studies show that chronic ozone exposure is associated with reduced lung function growth in children and accelerated lung function decline in adults. Ozone exposure increases risk of respiratory hospital admissions and emergency department visits.

None of this is controversial among environmental health scientists. When the American Lung Association, American Heart Association, and American Academy of Pediatrics review the evidence, they reach consistent conclusions. The health effects are real. The dose-response relationships are quantifiable.

So where does the EPA's uncertainty claim originate? It stems from legitimate but often overstated concerns about three things: first, distinguishing association from causation (though for air pollution, causality is well-established based on mechanisms and dose-response relationships); second, determining the precise quantitative relationship between exposure reduction and health outcome (the epidemiological studies provide reasonable estimates but with confidence intervals); and third, assigning economic value to health improvements.

The third category involves the most legitimate uncertainty. Estimating what society should value avoiding a respiratory hospitalization, or a lost workday, or a life-year requires economic judgment and methods that aren't purely scientific. Reasonable analysts can disagree about the most appropriate valuation approach.

But the first two categories don't justify eliminating benefits from analysis. The health effects exist and are quantifiable. We may have uncertainty about the exact magnitude—a regulation might prevent 45,000 deaths annually rather than 52,000—but that range of uncertainty doesn't disappear simply by refusing to estimate it.

The Practical Impact: A Concrete Example

To understand what this policy shift actually means, consider the EPA's 2024 regulatory impact analysis for stationary combustion turbines—the case that prompted the new benefit-exclusion approach.

Stationary combustion turbines are used in various industrial and power generation applications. They emit nitrogen oxides, which contribute to ground-level ozone formation, and particulate matter. The EPA proposed tightening emissions standards for these turbines, requiring installation of updated emissions control equipment.

Under the 2024 methodology (the last analysis to include quantified benefits), the EPA estimated annual benefits from this regulation at

The EPA also estimated compliance costs. Companies installing new emissions control equipment would incur capital costs for equipment purchase and installation, plus ongoing operational and maintenance costs. The exact cost depends on the specific turbine type and operational profile, but typical estimates ranged from $5–15 million annually for the affected industry.

Under this comparison, benefits (

Now consider what happens under the new approach. The EPA still calculates compliance costs: $5–15 million annually. The agency no longer includes quantified benefits. Instead, the regulatory impact analysis contains qualitative statements like "emissions reductions will result in improved air quality and corresponding health benefits, which are not monetized in this analysis."

A policymaker or industry representative reviewing this analysis sees

This practical impact extends beyond single regulations. When the EPA conducts annual regulatory accounting, it totals up costs and benefits across all major regulations. These accounts inform political debates about regulatory burden. With benefits removed from certain categories, the regulatory burden appears larger. Complaints about overregulation appear more justified.

Over a decade, if this approach applies to dozens of air quality regulations, it could shift billions of dollars in ostensible regulatory costs off the ledger's benefit side. This doesn't change the underlying health reality. Pollution still causes disease. But it changes how that reality is represented in official policy analysis.

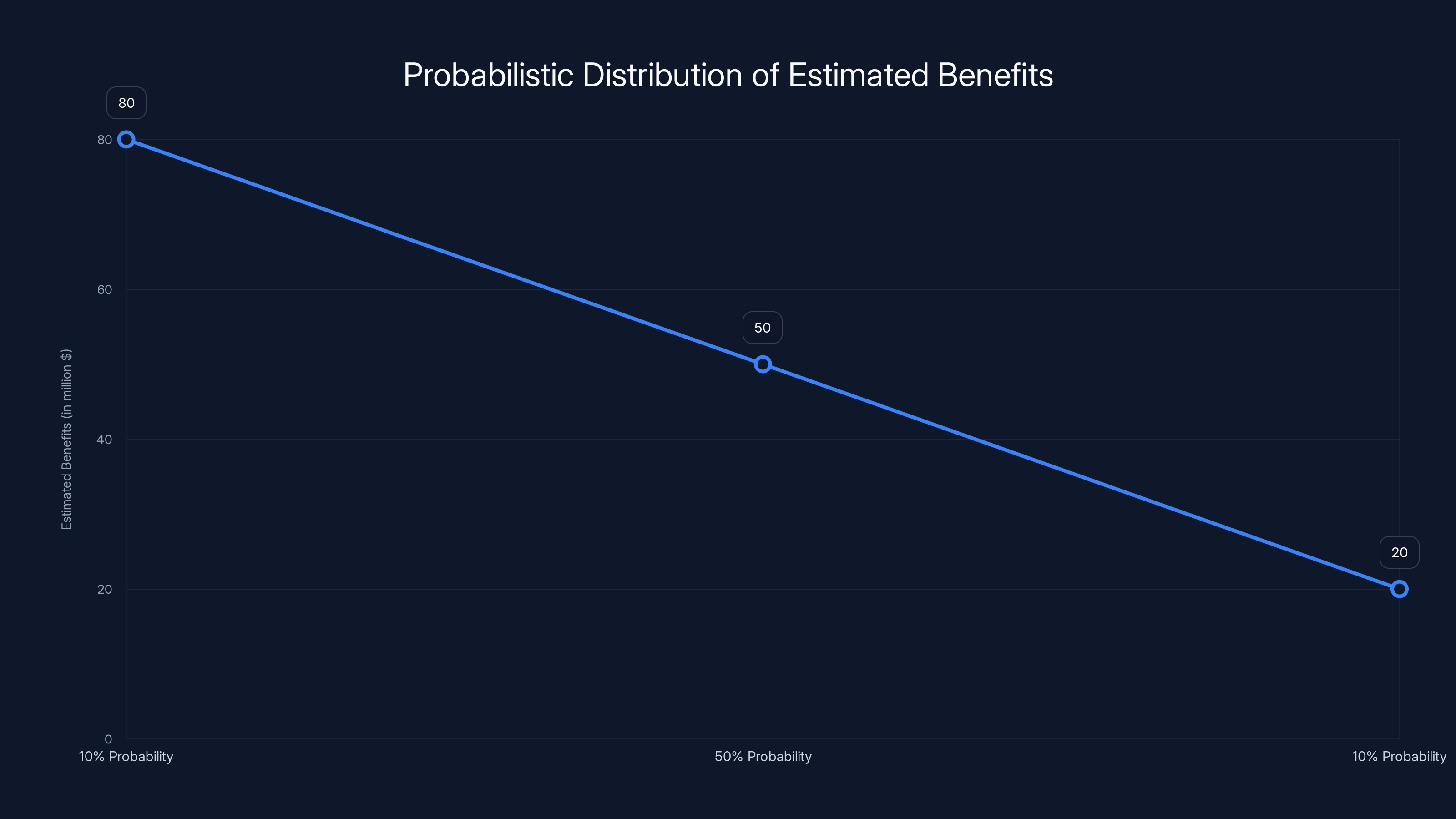

This chart illustrates the probabilistic distribution of estimated benefits, highlighting the range of

The Political Context: Who Benefits From This Change

Environmental policy debates are ultimately about competing interests. Different groups benefit from more or less stringent pollution regulations, and they marshal arguments accordingly.

Industries that emit PM2.5 precursors or ozone precursors—including power generation, oil refining, chemical manufacturing, and petroleum extraction—incur costs when regulations tighten. These sectors have legitimate interests in keeping compliance costs manageable. They also have significant political influence, contributing to campaigns and lobbying efforts.

These industries have consistently argued that air pollution regulations are more stringent than necessary and that health benefits are exaggerated. This argument makes economic sense from an industry perspective—if benefits are indeed lower than EPA estimates, then current regulations impose unjustified costs. The logical policy response would be to loosen standards.

Air pollution's health victims don't have parallel organizing capacity. People with asthma, those living in areas with poor air quality, and those at risk from cardiovascular disease don't form a unified lobby. Children whose lung development is compromised by air pollution cannot advocate for themselves. This asymmetry in political power shapes policy debates.

The federal government has historically attempted to resolve these distributional conflicts through technocratic methods. Cost-benefit analysis was explicitly designed to provide an "objective" basis for policy that transcended interest-group politics. By quantifying both costs and benefits, policymakers could appeal to economic efficiency rather than naked political preferences.

But this technocratic approach only works if the analysis is actually comprehensive and unbiased. Once one side—the cost side—is quantified while the benefit side is vague, the appearance of objectivity masks a systematic preference for less regulation.

The Trump administration's approach to this issue reflects a particular political philosophy that environmental regulations are generally excessive and should be curtailed. This philosophy has support in some quarters—particularly among those who bear the compliance costs—and opposition among those bearing the health costs. The new policy isn't presented as a preference for deregulation but rather as a technical correction addressing exaggerated precision in benefit estimates.

This framing matters because it makes the change harder to oppose on political grounds. Objecting to more transparent accounting of uncertainty seems less defensible than opposing deregulation on principle. The administration has effectively converted a policy preference—less environmental regulation—into a methodological question about scientific uncertainty.

Alternative Approaches to Handling Scientific Uncertainty

If the EPA were genuinely concerned about appropriately representing scientific uncertainty in regulatory analyses, multiple methodological approaches exist that would address this concern better than simply eliminating quantified benefits.

First, the agency could use probabilistic approaches that explicitly model uncertainty. Rather than presenting a single benefit estimate of, say,

Second, the EPA could conduct sensitivity analyses showing how conclusions change with different assumptions. For instance: "If the health effect assumption is at the lower bound of estimates, benefits would be

Third, the agency could present multiple scenarios representing different states of knowledge or different value judgments. Scenario A might use conservative health effect estimates. Scenario B might use central estimates. Scenario C might use upper-bound estimates. Showing all three acknowledges uncertainty while allowing decision-makers to see the range.

Fourth, the EPA could distinguish between different types of uncertainty. Some uncertainty stems from inherent variability in populations (some people are more vulnerable to air pollution than others). Some stems from measurement error. Some stems from modeling choices. These represent fundamentally different issues and warrant different responses. Collapsing them all into "uncertainty justifies eliminating the benefit" obscures important distinctions.

Fifth, the agency could maintain consistent uncertainty standards across cost and benefit calculations. If uncertainty about health benefits justifies excluding them, shouldn't uncertainty about compliance costs also warrant excluding cost estimates? The asymmetric treatment of uncertainty—eliminating benefits but not costs—reveals that uncertainty is being used selectively.

Sixth, the EPA could present historical validation. How have previous EPA benefit estimates performed? When the agency estimated health benefits from past regulations, did actual health outcomes match predictions? This empirical calibration could inform confidence in current estimates. If past EPA estimates have been reasonably accurate, current uncertainty concerns appear overstated.

None of these approaches require pretending health benefits don't exist or are unknowable. They all acknowledge genuine uncertainty while presenting information transparently. The EPA's choice to simply eliminate quantified benefits suggests the concern isn't really about appropriate uncertainty representation.

Estimated data shows a decline in PM2.5 levels following regulatory changes, highlighting the impact of stricter air quality standards.

The Precedent and What Comes Next

The EPA's decision regarding PM2.5 and ozone creates a significant precedent that could extend to other pollutants and regulatory domains.

Once the agency has justified removing benefits from cost-benefit analysis for certain pollutants based on scientific uncertainty, the framework exists for applying the same logic elsewhere. What about nitrogen dioxide? Sulfur dioxide? Lead? Each of these pollutants has associated health effects that involve some uncertainty about precise quantification. Industries regulated under standards for these pollutants have incentives to argue for similar benefit-exclusion.

Beyond air quality, the precedent could affect regulations addressing water pollution, toxic substances, and other environmental hazards. The underlying logic—that uncertainty about health benefit valuation justifies removing benefits from analysis—isn't specific to air pollution. It's a general principle that could metastasize throughout environmental regulation.

The timing is significant. The current administration has shown eagerness to reduce environmental regulations. The EPA has received multiple directives to review existing regulations with an eye toward elimination or modification. This policy change fits within that broader agenda.

What might stop the expansion of this approach? Potential pushback points include:

First, court challenges. Previous EPA regulations justified through cost-benefit analysis might be vulnerable to challenge if the agency changes its methodology retroactively. If a court determines that the new approach is arbitrary and capricious—substituting a different analytical method without adequate justification—regulations could be struck down or remanded to the agency for revised analysis.

Second, internal professional opposition. The EPA employs thousands of scientists and economists. Many likely view the new approach as methodologically flawed. Some may voice objections through professional channels or leak concerns to media outlets, as reportedly happened with the initial decision.

Third, congressional opposition. If Congress concludes that the EPA has abandoned required analytical approaches, it could amend the Clean Air Act or impose conditions on EPA appropriations. While the current Congress may not take this action, future congresses might.

Fourth, state-level action. States with more stringent pollution standards or pro-regulation administrations might adopt their own analytical frameworks that include quantified health benefits. California, in particular, has historically moved ahead of federal standards.

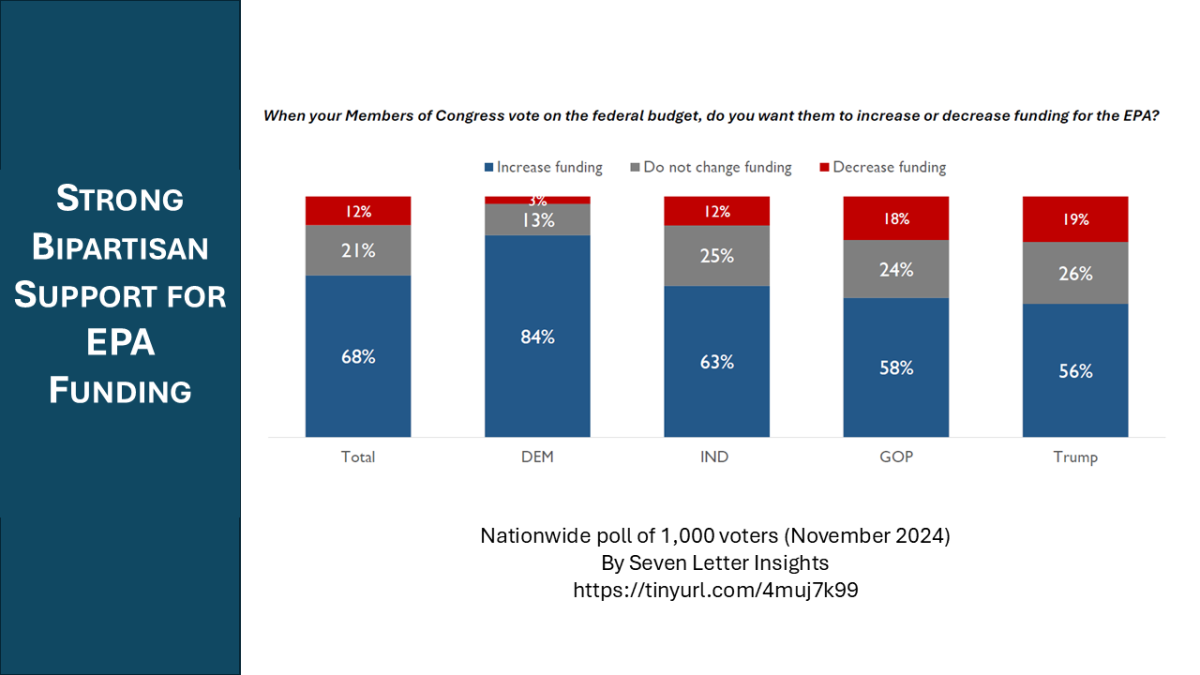

Fifth, public opinion. Environmental issues remain salient to significant portions of the electorate. If the health impacts of air pollution become more visible—through dramatic air quality events or public health campaigns—political pressure for stronger standards might increase.

None of these factors guarantee that the EPA's new approach will be reversed or limited. But they identify potential constraints on how far this methodology could extend.

The Broader Question: How Should We Value Health and Life

Beneath the technical disputes about cost-benefit analysis lies a more fundamental question: How should society value human health and life in policy decisions?

The EPA's traditional approach—using economic valuation methods to translate health improvements into monetary terms for comparison with regulatory costs—represents one possible answer. This approach has advantages and disadvantages.

On the advantage side, it forces explicit consideration of tradeoffs. A regulation that costs billions must provide benefits that justify that expenditure. Without monetizing benefits, regulators might impose excessive costs for marginal health gains. Economic analysis creates discipline.

On the disadvantage side, monetizing health and life reduces them to economic categories. Some people find this reductive. They argue that human health shouldn't be measured in dollars, that society has unconditional obligations to protect citizens from pollution, and that environmental rights shouldn't be subject to economic calculation.

There's also a practical concern: the monetization process inevitably involves judgment calls that affect outcomes. How should we value preventing a respiratory hospitalization? What's an avoided asthma exacerbation worth? Different methodologies produce different answers. These aren't purely technical questions; they reflect value judgments.

One alternative to economic monetization is the precautionary principle: when an activity raises threats to human health, precautionary measures should be taken even if cause-and-effect relationships aren't fully established scientifically. Under this approach, we don't need to quantify benefits precisely to justify pollution controls. If we have reasonable evidence of health harm, we should reduce exposure.

Another alternative is rights-based approaches that treat clean air as a fundamental right not subject to cost-benefit balancing. Many international frameworks, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights protocols, treat environmental quality and health as rights that cannot be traded away for economic efficiency.

The EPA has historically used a hybrid approach: cost-benefit analysis sets a framework, but specific air quality standards also reflect judgment about what constitutes acceptable risk. The agency doesn't regulate pollutants to zero—that would be economically impossible—but to levels where remaining risks are deemed acceptable.

What's changing now is that the benefit side of the balance is being obscured rather than evaluated. This makes the cost-benefit framework less useful, not more, because one side of the comparison is hidden.

Under the old approach, the EPA presented a benefit range of $8–15 billion, reflecting uncertainty. The new approach omits this range, focusing only on costs. Estimated data.

Implementation Challenges and Inconsistencies

Implementing the EPA's new approach to eliminating quantified benefits raises practical challenges that the agency will need to address.

First, existing regulations are already on the books with cost-benefit justifications that included quantified benefits. Does the EPA rewrite these analyses? If not, inconsistency becomes obvious: old regulations justified through methods the agency now claims are misleading. If the agency does rewrite analyses, it opens current regulations to challenge from industry groups claiming changed justifications.

Second, the EPA must define what "confidence enough in the modeling to properly monetize those impacts" means. The agency states it will not monetize benefits "until" it has sufficient confidence. This threshold is undefined. When will it be met? What evidence would demonstrate adequate confidence? Without clear criteria, the moratorium on benefit monetization could extend indefinitely.

Third, the EPA's approach affects only PM2.5 and ozone. Other air pollutants' health benefits continue to be monetized. This inconsistency is difficult to justify scientifically. Why is PM2.5 so uncertain that its benefits can't be quantified, but nitrogen dioxide health benefits can be? The underlying scientific evidence quality is comparable. The selective application suggests the decision isn't actually driven by scientific considerations about uncertainty.

Fourth, federal agencies coordinate on regulatory analysis. The Office of Management and Budget reviews EPA analyses and provides guidance on economic valuation. The EPA's approach creates tension with other agencies' practices. Will OMB approve similar approaches for EPA regulations while rejecting them for other agencies' analyses? Inconsistent standards undermine the credibility of technocratic decision-making.

Fifth, international trade implications exist. If the EPA is less stringent regarding pollution control than other major economies, U. S. companies might argue for exemptions from stricter international environmental standards. Conversely, trading partners might view weakened U. S. standards as a competitive disadvantage and adopt policies to offset it.

These implementation issues suggest the new approach will generate ongoing friction and controversy as the EPA attempts to operationalize it.

What Health Science Actually Tells Us About Benefits

Beyond regulatory methodology, it's worth asking: what do health studies actually show about the magnitude of benefits from reducing PM2.5 and ozone?

For PM2.5, a large systematic review examining health benefits of reduced exposure found that across multiple studies and populations, a reduction of 10 micrograms per cubic meter in PM2.5 concentration was associated with approximately 5.5 percent reduction in mortality. This relationship is reasonably robust and has been validated in different geographic areas and populations.

The EPA's current air quality standard of 12 micrograms per cubic meter annual average is substantially higher than levels in the cleanest parts of the world. If pollution could be further reduced, substantial health gains would result. Applying the quantified mortality relationships, combined with health effects on respiratory and cardiovascular disease, a further tightening of PM2.5 standards would prevent tens of thousands of premature deaths annually once fully implemented.

For ozone, controlled studies show that exposure to current legal air quality standards causes measurable respiratory harm in healthy people and greater harm in those with respiratory conditions. Long-term epidemiological studies show that living in areas with worse ozone is associated with reduced lung function and increased respiratory disease risk.

These aren't marginal effects that disappear with statistical uncertainty. They're substantial, consistent findings that underlie recommendations for pollution control from major health organizations.

The economic value of preventing these health impacts depends on how we value health. Using standard economic methodology, preventing one premature death is worth

Applying these values to the health effects prevented by regulations tightening PM2.5 and ozone standards, annual benefits easily reach tens of billions of dollars. This is why cost-benefit analyses consistently showed these regulations as economically justified—not because the benefits were uncertain, but because they were enormous relative to compliance costs.

Removing these benefits from regulatory analysis doesn't change the underlying health reality. It changes how that reality is represented in policy documents. But policy depends on representation. If policymakers don't see quantified benefits, they're less likely to consider them in decisions.

The Documentary Record and Transparency Concerns

One of the most concerning aspects of the EPA's new approach involves what happens to existing documentation of the agency's analytic methods.

Historically, the EPA has posted detailed methodology documents on its website explaining how it conducts cost-benefit analyses. These documents are publicly available and can be cited by researchers, advocates, and policymakers. They're part of the permanent record of how federal policy gets made.

As of the reporting of this change, the EPA was said to still maintain older documents explaining its previous benefit-monetization methodologies. But will these remain available? If the agency is now claiming that previous approaches were misleading, what message does it send if it keeps archived those methods?

Institutions can change methods for legitimate reasons. But when they do, they typically maintain transparent documentation of the change, including rationales and justifications. The concerning pattern here is the rhetorical erasure of previous approaches as mistaken without full explanation of why the new approach better serves transparency and accuracy.

There's also a question about institutional memory. In five or ten years, when the EPA's current leadership has moved on, will future administrators have the documentation needed to understand why this change was made and whether it should be continued? If institutional knowledge is lost or obscured, reversing poor decisions becomes harder.

Transparency and permanent documentation are essential to functional government. Environmental regulation affects billions of dollars of economic activity and millions of people's health. Decisions of this magnitude deserve clear, permanent records explaining the reasoning. The current approach seems designed to minimize that clarity.

Looking Forward: Potential Regulatory Outcomes

If the EPA's new approach to handling benefits becomes standard practice, what might we expect in terms of specific regulatory changes?

For PM2.5, the most recent National Ambient Air Quality Standard review occurred in 2012, when the EPA tightened the standard from 15 to 12 micrograms per cubic meter. The next statutory review is due in 2027 (standards must be reviewed every five years). Given current administration preferences, the EPA might maintain or potentially loosen the current standard rather than tightening it further, as some scientists have recommended.

With benefits excluded from the cost-benefit analysis, the justification for current standards appears weaker. An industry advocate could point to compliance costs (now quantified) against benefits (now described qualitatively) and argue the standards are more stringent than economically justified. The EPA might respond by holding the line on current standards, but only by invoking other justifications beyond economic efficiency.

For ozone, a similar dynamic could occur. The current standard of 70 parts per billion eight-hour average is already being challenged by some advocates as too lenient given health evidence. But with the new analytical framework, the EPA might resist further tightening or consider modest adjustments that still show standards as economically justified when only costs are quantified.

For stationary combustion turbines specifically—the immediate catalyst for this policy change—the new analytic approach makes proposed tightening standards look less attractive. The EPA might shelve proposed standards or propose less stringent versions that would generate smaller compliance costs.

Beyond these specific cases, the broader implication is that air quality regulation will likely move toward less stringent standards or slower pace of standard tightening. This represents a significant shift from recent decades, when standards generally trended toward greater stringency as health evidence accumulated.

The public health consequences of this regulatory trajectory could be substantial. Fewer preventive regulations mean more air pollution persists longer. More people develop pollution-related diseases. Healthcare costs rise. Productivity losses from illness increase. The monetized health benefits that disappear from EPA analyses might reappear as costs in the healthcare system and lost wages.

But those costs won't be attributed to regulatory policy. They'll appear as individual health problems, medical expenses, and lost productivity. The connection to policy choices will be obscured. This represents a kind of externalization: costs are invisible when health benefits are also invisible in policy analysis.

Lessons From History and International Precedents

How have other countries and time periods addressed the challenge of valuing health benefits in environmental regulation?

The European Union adopted an approach that's similar in some ways and different in others. EU environmental regulations generally require cost-benefit analysis but use slightly different methods for monetizing health benefits. Importantly, the EU doesn't exclude benefits simply because they involve uncertainty. Instead, EU regulators quantify benefits with explicit notation of confidence intervals and assumptions.

International bodies like the World Health Organization have endorsed the use of economic valuation for environmental health decisions, particularly in the context of quantifying the burden of disease. WHO doesn't view health monetization as reducing human dignity but rather as a practical tool for allocating limited resources.

Historically, the United States has used cost-benefit analysis for decades in environmental regulation without the controversy that now surrounds it. What changed? Partly, accumulating evidence of environmental harms made the benefits of regulation more obviously large relative to costs. When benefits are modest and costs are substantial, cost-benefit analysis creates controversy. When benefits are enormous, the analysis tends to be less contested.

Social movements have also influenced how environmental policy is framed. Environmental justice advocates have highlighted how pollution burdens fall disproportionately on communities of color and low-income populations. This redistributive dimension—who bears risks and who benefits—can't be fully captured in conventional cost-benefit analysis.

One lesson from history is that purely technocratic approaches to politically contentious issues often fail. Cost-benefit analysis can provide useful information, but it can't eliminate value disagreements. Some people prioritize economic efficiency; others prioritize health protection regardless of cost. Some view uncertainty as justifying caution; others view it as justifying inaction.

Policies that try to hide these value conflicts behind technical language eventually erode public trust. The EPA's current approach—using scientific uncertainty selectively to eliminate benefits from analysis—represents a kind of technical deception that could undermine broader support for environmental regulation.

The Institutional Challenge for the EPA

Beyond policy specifics, the EPA faces institutional challenges from this approach that could have long-term consequences.

The EPA is staffed with thousands of scientists and economists employed specifically to provide objective technical analysis for environmental decision-making. These professionals have expertise developed over careers and take pride in methodological rigor. When leadership directs them to adopt approaches they view as methodologically flawed, it creates tension.

This tension has already manifested in leaked documents and media reports of internal disagreement. Career civil servants are concerned that removing benefits from analysis violates professional standards. Some worry about defending this methodology before courts, knowing the underlying logic is questionable.

EPA employees who disagree with leadership direction face difficult choices. They can comply with directives and feel they're compromising their professional integrity. They can openly object and risk administrative retaliation. They can quietly resist through bureaucratic channels, slowing implementation. Or they can resign and seek employment elsewhere.

Over time, personnel decisions respond to leadership direction. If the EPA becomes a place where objectivity is compromised for political goals, the agency will struggle to retain talented technical professionals. New hires will increasingly be those willing to accept policy direction regardless of methodological concerns.

This matters because the EPA's authority and credibility depend on its reputation as a technical agency grounded in sound science. Once that reputation is damaged, the agency's influence over policy declines. Ironically, efforts to strengthen EPA rules by excluding benefits might weaken the agency's long-term capacity to implement environmental protection.

Historically, the EPA's strength has come from an implicit bargain: industry accepts stringent regulations because they're justified through rigorous technical analysis. Remove the rigor, and industry may simply resist all regulation on grounds that the regulatory process is politicized. The result could be less environmental protection, not more.

Conclusions and Implications

The EPA's decision to exclude quantified health benefits from cost-benefit analyses for PM2.5 and ozone regulations represents a significant departure from decades of practice. The justification—that scientific uncertainty warrants removing benefits entirely—obscures a policy preference for less stringent environmental regulation.

Scientific uncertainty about health benefits is real but not uniquely problematic. Multiple methodologies exist for appropriately representing uncertainty while maintaining comprehensive analysis. The EPA chose selective exclusion instead, a choice that lacks methodological justification but serves clear political goals.

The practical effect is to make pollution regulations appear less cost-effective than they actually are, tilting policy decisions toward less stringent standards. This represents a shift toward prioritizing short-term economic interests over long-term health protection.

The broader concern is that once technocratic analysis becomes politicized—once it's acknowledged or implied that the purpose is to achieve predetermined policy outcomes—the foundation of rational environmental governance erodes. If cost-benefit analysis is just a fig leaf for policy preferences, why have it at all?

What happens next depends on multiple factors: whether courts find the new approach arbitrary and capricious, whether Congress intervenes, whether future administrations reverse the decision, and whether public health consequences become visible enough to generate political pressure for change.

For now, the change stands as a significant moment in environmental regulation. It marks a transition from using ostensibly objective analysis to justify regulations that align with administration values, toward using analytical sleight of hand to exclude unfavorable findings. That transition has profound implications for how environmental protection will be pursued in coming years.

FAQ

What is cost-benefit analysis in environmental regulation?

Cost-benefit analysis is a systematic method for evaluating regulations by quantifying both the economic costs of compliance and the economic value of benefits (like health improvements). The EPA has used this approach for decades to justify air quality regulations by demonstrating that health benefits exceed the costs companies incur to reduce pollution.

How does the EPA's new approach change cost-benefit analysis?

The EPA now excludes quantified health benefits from analyses for PM2.5 and ozone regulations, describing benefits only qualitatively while continuing to quantify costs. This makes regulations appear less economically attractive without actually changing the underlying health impacts—it only changes how those impacts are presented in official documents.

Why did the EPA change its methodology?

The agency cites scientific uncertainty in estimating the economic value of health benefits. However, scientific uncertainty about precise magnitudes doesn't necessarily justify excluding benefits entirely; other methodologies could represent uncertainty more transparently while maintaining comprehensive analysis.

What does PM2.5 mean and why does it matter for this policy change?

PM2.5 refers to fine particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers that can penetrate deep into lungs and enter the bloodstream. It's particularly targeted for this policy change because anti-regulation advocates have challenged the health evidence, though that evidence is actually quite robust and consistent across studies.

How significant are the health effects of PM2.5 and ozone exposure?

Very significant. Epidemiological research consistently shows that PM2.5 exposure is associated with approximately 92,000 premature deaths annually in the United States. Ozone exposure increases respiratory disease risk and causes acute respiratory effects even at current legal air quality standards.

What are the economic benefits of reducing PM2.5 and ozone pollution?

Benefits are substantial, typically ranging from tens to hundreds of billions of dollars annually when multiplied across the population and time periods. A single prevented death is valued at $7–11 million using standard economic methodology, and regulations preventing tens of thousands of deaths easily show benefits exceeding compliance costs.

Could the EPA's new approach extend to other pollutants?

Yes. The precedent created—that scientific uncertainty justifies excluding quantified benefits—could apply to nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, lead, and other pollutants. This represents a significant potential expansion of the methodology beyond just PM2.5 and ozone.

How have environmental health experts responded to this change?

Most environmental health scientists and major health organizations view the new approach as methodologically problematic. They note that the health effects of these pollutants are well-established and that uncertainty about precise economic valuation doesn't justify removing benefits from analysis entirely.

What are the alternatives to excluding benefits from regulatory analysis?

Multiple alternatives exist: presenting probabilistic distributions showing ranges of benefits, conducting sensitivity analyses showing how conclusions change with different assumptions, using historical validation to assess forecast accuracy, and consistently treating uncertainty symmetrically across costs and benefits rather than selectively eliminating benefits.

Will this policy change affect specific upcoming regulations?

Likely yes. The 2027 review of the PM2.5 air quality standard may result in less stringent standards or postponement of tightening, and proposed tightening of ozone standards or emissions standards for combustion sources may be weakened. Industry advocates will point to the unfavorable cost-benefit comparison (now that benefits are invisible) to argue against stringent standards.

The Bigger Picture: What This Means for Environmental Governance

This policy change about cost-benefit analysis might seem like technical minutiae to those outside environmental policy. But it represents a fundamental question about how democracies make decisions affecting public health: Do we use comprehensive, transparent analysis that accounts for all major effects? Or do we selectively present information to support predetermined outcomes?

The EPA's approach suggests the latter. By removing quantified benefits while maintaining quantified costs, the agency creates an asymmetrical comparison that systematically biases policy toward less protection. This isn't transparency about uncertainty; it's selective omission.

Over time, if this approach becomes standard practice across environmental and health regulation, it signals a shift in how government conducts technocratic analysis. Rather than using technical methods to provide neutral information for democratic decision-making, those methods become tools for achieving political goals regardless of evidence.

That shift has consequences beyond this specific policy. It affects whether citizens can trust government analysis, whether regulated industries see regulations as legitimate, whether environmental protection can be based on evidence rather than just political power. These foundational questions about governance don't resolve through technical debate about uncertainty quantification. They require explicit political choices about what kind of democratic institutions we want.

Key Takeaways

- The EPA now excludes quantified health benefits from cost-benefit analyses for PM2.5 and ozone regulations, describing benefits only qualitatively while maintaining quantified costs

- This asymmetrical approach isn't driven by scientific necessity—multiple methodologies could represent uncertainty transparently while maintaining comprehensive analysis

- Health effects of PM2.5 and ozone are well-documented and substantial, with PM2.5 linked to approximately 92,000 premature U.S. deaths annually according to health research

- The policy shift makes pollution regulations appear less economically justified without changing underlying health realities, effectively making deregulation arguments more persuasive

- This precedent could extend to other pollutants and regulatory domains, potentially reshaping environmental governance if similar logic applies systematically across regulations

Related Articles

- AI PC Crossover 2026: Why This Is the Year Everything Changes [2025]

- Apple Creator Studio $129/Year: Complete Guide & Alternatives

- Scott Adams, Dilbert Creator, Dead at 68: Legacy [2025]

- Watch Australian Open 2026 Online From Anywhere: Complete VPN Guide [2025]

- Battlefield 6 Season 2 Delay: What It Means for Players [2025]

- Why Companies Still Hire Junior Engineers Despite AI Coding Tools [2025]

![EPA Removes Health Benefits from Pollution Analysis: What's at Stake [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/epa-removes-health-benefits-from-pollution-analysis-what-s-a/image-1-1768331269808.jpg)